ABSTRACT

In the mainstream, there has been a strong advocacy to prolong copyright duration. This makes it an important task to rigorously examine if a longer copyright duration is helpful in guaranteeing the earnings of authors from their works as well as the promotion of cultural creativity and diversity. In contrast to many previous studies that have been rooted in law-based perspectives, this paper addresses these issues by adopting a business and economic analysis. By exploring the true impact of different copyright durations, this paper scrutinizes why a longer duration does not improve the author’s earnings, and in fact, impedes cultural creativity and diversity. As a solution, this paper proposes to shorten the copyright duration and analyzes why this is likely to increase the earnings of authors from their works and to enhance cultural diversity and creativity. This study provides a complementary asset to understand more clearly copyrights and its effects.

Introduction

Over the last twenty years, the debate on cultural industries within European policy circles has tended to favor a longer duration for copyright protection. It is commonly believed that this will not only strengthen the earnings of authors, but also enhance cultural creativity and diversity. The last two aspects have long been identified as important goals for the European Union (EU). In 1993, an EU Directive standardized the copyright duration to 70 years after the death of the author (post mortem auctoris or pma) which is derived from German law (EU Citation1993; Giblin Citation2017), the longest of its kind in Europe. In 1998, the US Copyright Term Extension Act, the so-called ‘Sonny Bono Act,’ matched the EU’s new duration limit. In the years after, 70 years pma has been mimicked across various countries, largely due to the increasing number of preferential trade agreements negotiated with either the EU or the United States.

When the copyright duration was extended from 50 to 70 years for photographers in 2006 and for performers and sound recorders in 2011, this new legislation was considered to be a remarkable achievement for artists. However, it is important to note that eight of the EU’s twenty-seven Member States were against this extension. Some of their reasons include: (i) it mainly benefits recording labels, not performing artists; (ii) it has a negative impact on the pockets of consumers and their accessibility to cultural materials; and (iii) it does not help with the development of future talent, but rather orientates the recording industry to capitalize on its past investments (Kretschmer Citation2008; Theofilos Citation2013).

In order to understand better the impact of copyright duration upon cultural works, it is worth considering the fundamental purpose of copyrights as reflected in the mandates of key international institutions. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO Citation2017) focuses on protecting (i) the economic rights which allow the owners to derive financial rewards from the use of his/her works by others and (ii) the moral rights that preserve the non-economic interests of the author.Footnote1 The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO Citation2017) is more interested in enhancing cultural creativity and diversity for society as a whole rather than individual economic interests, although it does mention about the economic ‘incentives’ for creation. Finally, national enforcing bodies such as the United States Copyright Office (Citation2017) mainly deal with the usage of copyrighted works such as reproductions, derivatives, and distributions, thus it is concerned with business and economic factors.

These mandates demonstrate how copyrights seek to guarantee the earnings of authors – derived from the revenues generated by their works – as well as to promote cultural creativity and diversity. Although the importance of culture has been frequently highlighted in policy discussions, the notion of cultural creativity and diversity is in fact linked to economic factors. This is due to two main reasons. First, as recognized by UNESCO and the United States Copyright Office, authors need economic incentives through their earnings in order for them to create further works and therefore promote cultural creativity and diversity. Second, the WIPO has identified the fact that such a cultural development can be enhanced by producing many original works without imitation or copying.

Given this context, we adopt a business and economic analysis to scrutinize conceptually the true impact of two different copyright durations instead of merely asserting that a certain copyright duration is more beneficial. Only through this approach can we accurately examine whether a longer copyright duration has either a positive or a negative impact on the earnings of authors. And more importantly, it can also demonstrate the effect it has on cultural creativity and diversity. Due to the wide range of copyright protections, this paper focuses on books, music, films, and paintings which are consumed by the public on a regular basis. For simplicity sake, it uses the terms ‘authors’ (of books, music, and other productions), ‘publishers’ (book publishers, record labels, and other production houses), and ‘works’ (books, music, films, and other productions) in their generic sense.

This paper recognizes that the creative and cultural industries of today have become more complicated with digitization and the advent of the Internet, specifically through streaming services, video-sharing websites, and other digital platforms. However, it should be stressed that most of these new providers operate under licenses from the traditional publishers for all copyright-protected works. As a result, in order to focus on the fundamental issue of copyrights and to understand the true impact of different durations, this paper places these technological advancements and their impact aside. This allows for them to be used for further studies based on the findings presented here.

The contents of this paper are organized as follows. The first section deals with the literature review on copyright duration and highlights the need for a new perspective that this paper undertakes. The second section sheds light on the true origin of copyright issues which is derived from the private contracts signed by authors and publishers. The third section shows that the current copyright duration is detrimental to the actual earnings of authors from works as well as hindering cultural creativity and diversity. The fourth section examines the impact of a shortened copyright duration on the earnings of authors as well as cultural creativity and diversity. Lastly, the concluding section summarizes the main findings and the implications to be drawn from these analyses.

Literature review

Copyright duration has often been frequently extended since the birth of copyright law and there are still those who advocate for it to be longer. Although the voices arguing for it tend to dominate the political decision-making process, a large part of the academic discourse and several groups of authors favor a more critical stance with a longer duration of copyrights.Footnote2 In other words, when analyzing the impact of copyright duration on the earnings of authors and more broadly upon the development of culture, there are two opposing viewpoints: longer duration versus shorter duration.Footnote3

It is noteworthy to point out that critical copyright scholarship often recognizes how the advocacy for expanding copyright duration largely comes from industry-related (or funded) research (Callahan and Rogers Citation2017; Hesmondhalgh Citation2009; Karaganis Citation2011). Regardless of these facts, a more nuanced view toward these different perspectives on copyrights is presented in this section. Given that there are so many studies involved in this debate and they cannot all be covered in this paper, the focus will be on just those few that cover the broader aspects of either longer or shorter duration.

In supporting longer duration, Hatch (Citation1998) summarizes four main reasons for embracing such an approach: (i) copyrighted work is like personal property and it needs to be protected with increased longevity because authors need earnings throughout their longer lives; (ii) piracy has been greatly facilitated by the advent of digital media and the global information infrastructureFootnote4; (iii) the marketable lives of works have been enhanced in the era of digitization through the help of longer duration; and (iv) longer copyright duration does not impede creativity or the wider dissemination of works. However, these contentions lack solid theoretical and practical backgrounds as they are simply based on juridical viewpoints.

Liebowitz (Citation2007) goes further by arguing that the optimal copyright length can be infinite because copyrights impose trade-offs between the production of new works and consumption of old works. He bases this on several factors: (i) ownership of works provides values which can be reinvested in other works; (ii) unauthorized copying reduces appropriate revenues that are incentives to generate cultural creativity and diversity; and (iii) copyrights do not provide monopoly power to the copyright owners in the vast majority of instances.

These analyses though require two major counterpoints. First, the commercial life of works is very short regardless of the increased lifespan of the authors (Australian Productivity Commission Citation2016; Caves Citation2000). This is even the case with the digital age despite the great transformations that have occurred in the cultural industries. Second, the ways to gain revenues (or income) have diversified (or even shifted away) from traditional ones such as sales of works to other new sources (Parc and Kawashima Citation2018; Parc and Kim Citation2020). In particular, reputational earnings can eventually be rendered into monetary earnings. One of the best illustrations is the emergence of Korean popular music or K-pop, particularly with the song ‘Gangnam Style’ by Psy; a large part of his revenues is not directly from copyrights but from on-site performances and advertisements which he was able to earn due to the reputation he had crafted through a liberal diffusion of his music online (refer to McIntyre [Citation2014]; Parc, Messerlin, and Moon [Citation2016] for further details). The case of Psy underlines an important yet often forgotten fact that it is the authors who should reap a significant share of the earnings, not publishers.

Alongside this, there are also a number of studies that support a shorter copyright duration. For example, Reichman (Citation1996) views longer duration as a form of an unjustifiable subsidy to publishers who then operate in a rent-seeking fashion. In fact, while a private contract for copyrights reduces the bargaining power of authors with respect to their publishers (Aksika and Andrews, Citation2014), longer duration of copyrights makes this asymmetry even worse (Cargill and Moran Citation1971).Footnote5 Once they have signed a ‘private contract,’ the authors have a very limited role and the longer duration only amplifies this limitation. As publishers have more monopolistic power to utilize these works, they become more expensive. Yet price increases do not ensure greater earnings for authors and consumers often have to pay higher prices to enjoy these works (Kretschmer Citation2010).

Akerlof et al. (Citation2002), Boldrin and Levine (Citation2008), and Lessig (Citation2004) all point out that longer duration has no positive impact on the past works of authors. In extending a duration that will be applied only for future works, it does not change the incentives that authors had with their works created in the past. From the perspective of cultural creativity and diversity, all works are equally important regardless of their production year. In addition, the present value of the authors’ earnings does not increase by much through the additional earnings occurring in a far-away future – for example, between fifty to seventy years after the death of the author. Therefore, longer duration is very unlikely to reflect positively upon the earnings of authors. Buccafusco and Heald (Citation2013) take this a step further when arguing that the essential purpose of a limited copyright duration is not to increase the earnings during the copyright period, but rather to ensure the existence of a productive ‘public domain.’Footnote6

This brief literature review raises three crucial points. First, it is necessary that any copyright duration must ensure that authors reap a significant share of the benefits. Second, the low bargaining power of authors caused by the private contract requires changes in order to create a healthier environment. Third, more broadly, it must also help boost cultural creativity and diversity for society. All of these factors should be taken into account when assessing the impact of copyright duration and this is the main focus for this paper.

The fundamental issues: ‘copy’-rights and private contracts

In order to delve into the fundamental issues of copyrights, it is important to review the original goal as well as the evolution in its duration and then to analyze its significance based on these facts. The United Kingdom was the first country to introduce copyrights with the Statute of Anne or the Copyright Act of 1710. This law is known to have two very important points: (1) it granted exclusive rights to the authors in order to prevent publishers to distribute, modify, or abuse the works without a private contract with the authors; (2) it imposed a copyright duration, which was fourteen years for books published after 1710 and twenty-one years for those published before that date. Out of this emerged the concept that copyrights would protect authors as well as help to enhance cultural creativity and diversity. Still, the rhetoric behind this should be carefully analyzed in order to understand exactly how it was applied in the real world.

First, the exclusive rights granted to authors – previously, publishers ‘secured’ the right to copy works and even alter them – would seem to offer them protection. However, the Copyright Act was actually designed to protect the rights of English publishers to copy works by securing a private contract with authors while limiting those of non-English publishers, particularly Scottish and Dutch ones, in the English book market (Balázs Citation2011; Baldwin Citation2014; Johns Citation2009). This is why the term ‘copy’-rights was used rather than ‘author’-rights. As a result, private contracts have been anchored and geared toward supporting this process which protects publishers rather than authors.

Second, as the initial conceptualization of copyrights was opposed to a ‘proper right,’ it instead sought to promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for a limited time the exclusive rights for authors and investors to their respective writings and discoveries. In addition, the notion of copyright duration was initially introduced not to protect publishers or authors, but to put a time limit on the monopolistic power of publishers. This was intended to enhance the competition among them.

Third, copyrights and its limited duration were in fact designed to incentivize creativity and scientific discovery as well as to encourage learning and contrasts which led to the ‘outcome’ of the intellectual property right regime that exists in our time (Kretschmer and Kawohl Citation2004; Rose Citation1993; Vaidhyanathan Citation2001). In particular, during the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment was prevailing and the importance of education and knowledge diffusion was popularized. In this context, any measures that hindered this societal trend of diffusing and sharing knowledge and education were seen as an infringement of the Enlightenment’s core principles (Lessig Citation2004). It is interesting that even three centuries ago, there were efforts to limit copyright duration for the betterment of society.

It is important to stress that the copyright duration was only extended because publishers sought to secure their rent-seeking business by reducing competition and achieving a longer copyright term or even to hold the rights permanently. In particular, from 1731 to 1775, they developed ‘coalitions’ with authors under the guise that they were helping them.Footnote7 Under this condition, authors had to transfer through private contracts the effective use of their ‘sole and exclusive’ copyrights to publishers chosen for printing and selling the works. In short, once the private contract has been signed, a ‘very unequal bargaining’ situation prevails in most cases between the author and the publisher (Towse Citation1999, Citation2003). All of these changes have placed publishers in a superior position vis-à-vis authors.

Despite the significant structural problems of the above-mentioned publisher-centered operational and value creation system, this fact has often been overlooked (Schlesinger Citation2017; Schlesinger and Waelde Citation2012). The vast majority of existing studies within the current debate on copyrights follows the notion of a ‘coalition’ by perceiving authors and publishers as one entity. The situation regarding copyrights is then framed as a conflict between ‘authors-publishers’ and ‘consumers’ (AC and BC in ). In actual fact, this is very different from what the Statute of Anne initially focused on (BB in ).

Table 1. Comparison: focus of copyright conflicts

Today, the general belief is still that copyright law places the author at the epicenter of the industrial chain which then goes down to the consumer (see left in ). In doing so, the law would prohibit copy or imitation of the original work in order not to harm its revenues and to promote cultural creativity and diversity. However, in reality, once the private contract has been signed, the publisher becomes the epicenter of the industrial chain due to the exclusivity terms included (see right in ). The author is de facto ‘integrated’ into the publisher-led industrial chain, and it brings about two very critical problems.

Figure 1. Devolution of copyrights

First, the publisher-centered industrial chain has a direct impact on the printing, distribution, and sales of works, hence on their revenues. From a business and economic perspective, private contracts limit the bargaining power of authors and make them the weakest actor in the chain, with only a few exceptions in regard to superstar authors. The author’s ‘monetary benefits’ or earnings thus depend crucially on the business capacities of the publishers with an assumption that the quality of the works among various authors are similar. At the same time, the contracted publishers may not do their best to diffuse the works as widely as possible as they have already secured exclusive rights of other works in great quantities, hence the other possible ‘reputational benefits’ earned through wide distribution will also be limited. Eventually, all of these consequences reduce the authors’ earnings as well as the incentives for new creations – the opposite of the stated goal of copyright law.

Second, there is a principal-agent problem. In order to boost the earnings for the author, the overall revenues of the work should be maximized. Under private contracts and the publisher-centered industrial chain, the author has a number of limitations to monitor whether the contracted publisher is doing its best to maximize revenues from the work. Such a situation affects directly the earnings for the author regardless of the quality of his/her work. This is all the more the case when, as under the laws of EU Member States, the re-negotiation possibility for the private contract has been reduced even if the author feels that his/her interests are not well served by the contracted publisher (Hugenholtz et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, the principal-agent problem increases substantially when, as is the case nowadays, the author has only one publisher for a given work, whereas most publishers are in charge of many authors.

All of these concerns indicate that in order to analyze the impact of copyright duration, it is important to have a greater understanding on the real impact of copyrights based upon these two critical issues caused by the private contracts. This approach is where this paper differs from other existing studies. It recognizes that the weak bargaining power among authors and the principal-agent dilemma both have a negative effect on the relationship between authors and publishers (shown as AB in ). This then requires a movement away from the assumption of ‘author-publisher’ as one entity, which reveals the ‘structural under-performance’ of the publishers under the copyright regime. By the same token, this paper produces a fresh analysis on the consequences of the current long duration on the earnings of authors as well as on cultural creativity and diversity. As a policy suggestion, shortening the duration is considered and its impact is analyzed. Both analyses deserve one important remark. They focus exclusively on the production side of cultural industries, leaving aside the question of the revenue allocation between authors and publishers.

Current (long) copyright duration and its consequences

It has generally been believed that a longer copyright duration would be the best way to protect works, thus guarantee the earnings of authors. In recent years, this argument has been further supported by the increasing lifespan of authors and more interest in culture as a form of soft power.Footnote8 However, this perception neglects the reality of a much shorter commercial life for works and the existence of private contracts that limit the bargaining power of authors under a longer copyright regime. Under the current copyright duration, which lasts 70 years pma, authors have no chance to benefit from relevant copyright-protected works. This section shows how these two factors can be detrimental to the earnings of authors as well as its impact on cultural creativity and diversity.

The actual earnings of authors under the current duration

Contrary to what authors and publishers may wish, the actual commercial life of a work is relatively short. According to the Australian Productivity Commission (Citation2016), musical works have two to five years of commercial life on average. Within this short period, 70 percent of music generates no more revenues from the second year after release. The commercial life of books lasts between 1.4 and five years on average. Furthermore, 75 percent are unavailable after the first year and 90 percent of original publications are out of print within two years. The average commercial life of films is between 3.5 and six years and only very few films generate revenues after the sixth year. Lastly, most visual artistic works, such as spectacles and events, generate no revenues after two years from their release. This context brings about a very different result on the earnings of authors from what the copyright regime originally sought.

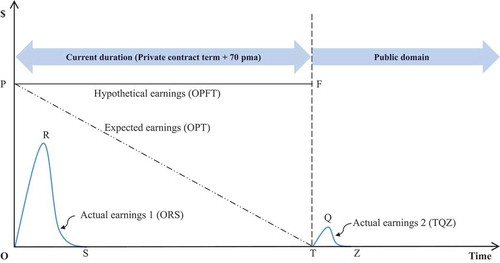

As these facts are not well known, it is often assumed that, under the current duration of copyright protection or 70 years pma, a work will generate annual revenues OP during the whole protected period OT (see ); hence total revenues can be illustrated as OPFT. Yet, in the real world, popularity or demand for a work will eventually fade away over time. Thus, the expected revenues from a work should be more realistically assumed as OPT. However, the revenue derived from the actual commercial life is very different. The typical revenue from a work appears as a bell-shaped path ORS (Gowers Citation2006). At Time T, the copyright expires and the work enters the public domain. This allows the existing publisher, non-contracted publishers, and any other business operators to utilize and diffuse the work without paying copyright fees to the author or the rights holder, thus less legal constraints. In this respect, a new commercial life is given to the work and it generates the revenues TQZ. It should be noted that under the current copyright regime defined on a post-mortem basis, authors have no chance to benefit from the revenues TQZ.

Figure 2. The actual earnings from a work under the current (or long) copyright duration

As a result, most of the authors’ earnings, received during their life time, currently depend upon the revenues ORS which ends far too quickly. The magnitude of this revenue principally depends on the quality of the work, but after its release in the market the revenue also relies crucially upon the publisher’s business activities, such as marketing and sales to maximize ORS – to make it higher and/or longer. This then becomes the main source that affects the total revenue. Under these conditions, the weak bargaining power of the authors and the principal-agent dilemma hamper the ability of works to generate their optimal (or maximal) revenue. Instead they induce the structural under-performance of the publishers which does not help authors to enjoy ‘proper’ earnings from their works. It is noteworthy that as time goes by the structural under-performance is likely to amplify. Hence, the incentives for authors to create more works will clearly deteriorate. This disadvantageous effect can be worse with a longer copyright duration.

Cultural creativity and diversity under the current duration

Under the current copyright duration, produced works face a very long ‘hibernation’ period (ST). Due to their short commercial lives, most works are not available in the market during the period ST which is roughly 95.4 percent of the current duration OT. This calculation is based on the assumption made by European Commission (Citation2008) that the average life expectancy is 80 years and a work is created when the author is 20 years old. In addition, the commercial life of this work only lasts 6 years and the author survives 54 years after the creation of this work, plus 70 pma (see note 8). When in hibernation, the cultural potential of most works cannot be fully enjoyed by society that impacts negatively upon cultural diversity in a severe way. Moreover, the fact that most publishers are actively engaged in discovering new artists and distributing newly created works makes it even less interesting for them to promote existing copyright-protected works. At the same time, established authors and their works are being held hostage by longer duration and private contracts. Despite their interest in these ‘underutilized’ works, non-contracted publishers cannot revitalize the works until they enter the public domain unless the copyrights are handed over. This sequence of events shows how the longer the copyright duration and the longer the hibernation period, the greater the loss of cultural diversity will be.

In general, it is believed that copying or imitating existing works discourages cultural creativity and diversity as it is considered to be immoral and often even illegal. At the same time, a large number of hibernating works do not help cultural creativity either. This is because certain authors happen to produce similar works to the ones that are copyright-protected but in hibernation; thus, not widely known. These authors can be ‘inhibited’ to produce their works for fear of being accused of copying those hibernating works – in other words, to avoid any possible economic, emotional, or even moral damage. Hence, the longer the copyright duration, the higher the level of inhibition, and the higher the loss in terms of cultural creativity. As a result, this vicious circle caused by a longer copyright duration brings about a lower level of earnings. This eventually discourages the creativity of authors.

In contrast to previous views, Parc (Citation2020) and Parc et al. (Citation2016) argue that copying or imitating existing works can promote cultural creativity and diversity. The cases of Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and other well-known painters clearly demonstrate that they did not feel any shame or immorality for copying or imitating existing works. Furthermore, their actions did not hinder cultural creativity and diversity (Parc Citation2020). It is important to note here that during the copyright term imitating works without permission is illegal, however imitating other works that are in the public domain is not. This fact shows that illegality has ties with the juridical term, not the act of copying or imitation per se. Clearly this means that copyrights are a pecuniary issue, not one related to cultural creativity or diversity.

Shortened copyright duration and its consequences

The previous section demonstrated that the longer duration has neither a positive impact to increase the earnings of authors nor does it enhance cultural creativity and diversity. In order to make copyright protection more author- and culture-friendly, this section proposes to shorten the copyright duration as a remedy and examines the consequences in doing so. The main merit of this option is to increase the bargaining power of authors vis-à-vis publishers and to reduce the principal-agent problem in the cultural industries, hence to reduce the structural under-performance of publishers. As a result, the shortened copyright duration can contribute greatly to improve the earnings from works for authors and to enhance cultural creativity and diversity.

The expected earnings of authors under shortened duration

Authors often complain that they are paid less than they deserve. To this extent, illegal downloads and free online access are often perceived by them as the main culprits – a subject that this paper places aside to focus instead on the fundamental issue of copyright duration. However, as shown above, one of the fundamental reasons for explaining this situation is the long copyright duration and the private contracts under this extended period of time. In this regard, how would a shortened copyright duration change the asymmetric bargaining power between authors and publishers and impact consequently on the revenues from works, hence on the earnings of authors? The following section shows that such a shortened duration would increase earnings in the two periods, public domain and copyright term.

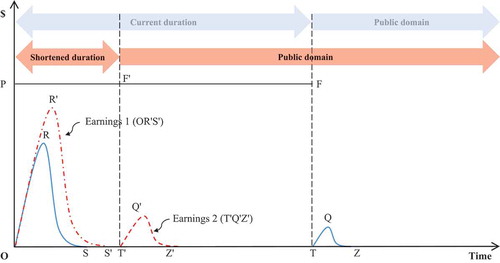

First, works will enter the public domain earlier. Such works can then be more easily and creatively utilized by any agent such as publishers, media operators, or even other authors. Compared to when they are under copyright protection, they can be more effectively diffused and provide authors with wider social recognition than before. Therefore, these works in the public domain will at least generate higher reputational earnings for authors. If the copyright duration is short enough, these reputational earnings can be gained during the life time of authors, which will motivate them to produce new works. Hence, as shown in , the revenues of the work TQZ in the previous public domain period will appear earlier at Time T’ as T’Q’Z’ and it will be higher and/or longer than TQZ. As will be explained later, part or all of these revenues can go to authors. The reputation gained from the previous works under the public domain naturally affects other currently copyright-protected works as well as new ones. In this respect, these changes could potentially create a more author-centered industrial chain; thus, more earnings for authors.

Figure 3. The expected earnings from works under a shortened copyright duration

Second, a shortened duration is also likely to change the business behavior of contracted publishers during the copyright term. Compared with operating under a longer copyright duration, publishers will need to seek out more effective business activities and to develop better strategies in order to maximize profits within this shortened period, leading to a greater utilization of the works they are in charge of. Such a propensity is very common in business (Narayanan Citation1985). In this context, publishers would offer greater earnings to authors in order to secure their newly released works. This is all the more the case because the reputational benefits of their previous works under the public domain can have a positive impact on the leverage of the authors when they negotiate the private contracts of their new works. Furthermore, with shortened duration, the performance outcome of business activities among publishers can be easily checked and compared as authors monitor it with their own eyes during their lives. Therefore, the private contracts can be more in favor of authors, thus significantly reducing the principal-agent problem. illustrates the consequence of these effects: the revenues generated by the works could shift from ORS to OR’S’ – bringing more revenues over a longer period. This shortened duration tends to increase the overall performance of the cultural industries.

Cultural creativity and diversity under shortened duration

While contracted publishers have more motivation to develop effective business strategies and activities in order to maximize the utilization of copyrighted works, authors will also have greater incentives to produce more works at a faster rate than before. The shorter hibernating period either ST’ or S’T’, instead of ST under long duration, ensures existing works enter the public domain earlier. At the same time, there are increasing reputational earnings through other media contents as shown with the case of Psy. The result is that cultural diversity can be more enhanced under a shortened copyright duration.

In this environment, authors have less fear of copyright infringement as there is a decreased risk of hurting moral rights. As shown in , authors face unintended infringement only during Period ST’ at the longest or Period S’T’ at the shortest, both of which are significantly shorter when compared with Period ST. Therefore, authors can concentrate on their creations with significantly less worry about negatively affecting the moral rights since many of the works are in the public domain and their existence is more widely known; thus, easy to avoid potential risks. As a result, more works will be created and available than before, a process that will unleash further cultural creativity and diversity.

In particular, it is easier for authors to be aware of various existing works that are in the public domain as they are utilized more often by various other media operators. Authors are able to observe and perceive trends and market preferences from the large number of works, regardless of their popularity or utilization, that are available under the period of public domain; this can enrich inspiration for new works. As many ‘inspired’ works can be freely produced, authors become more creative in order to generate wider appeal and differentiate their works more effectively. All of these processes are in fact crucial toward enhancing the next generation of works (Benkler Citation2006; Gillespie Citation2009). Furthermore, this aspect is clearly demonstrated by a number of exemplary cases throughout the history of art (Parc Citation2020). This enhanced productivity places authors in a more advantageous position when they sign a private contract. As a result, incremental improvements in the dissemination of works are likely to have a considerable aggregate economic value despite a short commercial life.

Conclusion

There is a widely held belief that a longer duration in copyrights ensures higher earnings for authors. In emphasizing the critical role of authors, this paper argues that a longer duration with private contracts hinders an increase in the revenues from works, hence the earnings of authors. This is because the very limited bargaining power of authors and the principal-agent dilemma induce publishers to be structurally under-performing – that is, not effective enough at optimizing (or maximizing) the full cultural potential of the works they are responsible for.

As a solution, this paper suggests that, if well designed, a shortened copyright duration will clearly bring benefits to the vast majority of authors as well as society. This shortened duration induces publishers to develop more impactful business activities coupled with effective strategies in order to maximize the utilization of contracted works. Furthermore, authors can benefit from the reputational earnings of their works that enter the public domain much earlier than under the current system. More activities under the public domain period will allow authors to be more at the center of the industrial chain. They will also be able to concentrate on their creation without any fear of copyright infringement. Another benefit is that due to the earlier public domain period, many works that are not too outdated will become more readily available. In such a case, this availability would inspire authors to produce better works. Through various measures such as internet platforms and media outlets, they can be diffused faster and wider than before. Therefore, this system can contribute toward enhancing cultural creativity and diversity.

Some might argue that digitization has ruined a number of cultural industries as internet piracy and copyright infringement have been more prevalent than before. As this paper places these issues related to digitization, technological advancements, and their impact aside, they can be further analyzed in order to draw important implications that can be applicable during this period. In this regard, several real-world examples such as the emergence of Netflix or even the Korean music industry with K-pop can hint at ways to overcome copyright issues in the era of digitization (Parc and Kawashima Citation2018; Parc and Kim Citation2020). This task can be synergistically undertaken by utilizing and applying the findings of this paper.

There is no doubt that culture and its diversity should be protected and preserved. Culture consists of tradition and modernity in terms of the period in which it was developed. In other words, they can be described as either ‘accumulated’ or ‘accumulable’ heritages (Parc and Moon Citation2019). Surely, these accumulated heritages were once accumulable ones and have survived over time while being very prosperous. In our time, the value of the past shines on the presence of an accumulated heritage. If we are thinking about the future as well as the present, the value of accumulable heritages should not be neglected. In this regard, the role of copyrights is very critical. Without much restriction such as a long duration of copyrights, they can further promote prosperity and the wider availability of accumulable cultural contents which will be part of accumulated culture later.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jimmyn Parc

Jimmyn Parc is a visiting lecturer at Paris School of International Affairs (PSIA), Sciences Po Paris, France and a researcher at the Institute of Communication Research, Seoul National University, Korea.

Patrick Messerlin

Patrick Messerlin is Professor Emeritus of economics at Sciences Po Paris, and serves as Chairman of the Steering Committee of the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE, Brussels). He was also a Visiting Professor at the Graduate School of International Studies, Seoul National University.

Notes

1. Refer to Rajan (Citation2011) for further details regarding the aspect of moral rights in copyrights.

2. Regarding the voice of authors, there are many perspectives toward this issue especially since the rapid diffusion of digital technologies (refer to Spender [Citation2009]). Still, it is often the case that well-known authors support a longer duration of copyrights, while others have a more neutral stance or even oppose it.

3. In fact, there is a third ‘in-between’ position. For instance, Chamberlain (Citation2016) argues that a unified duration may not be an optimal solution because the various media outlets of culture (book, music, and film) do not possess the same commercial time horizon. Accordingly, he proposes tailoring duration by cultural medium. In the same vein, Landes and Posner (Citation1989, Citation2003) propose to create an ‘indefinitely renewable’ copyright regime which gives authors the right to ‘renew’ at specific times the private contracts they signed with their publishers; thus giving back by the same token to these authors some bargaining power vis-à-vis their publishers. While Landes and Posner (Citation1989, Citation2003) are based on economic rationales such as tracing costs, transaction costs, benefits of public goods, discount of the work’s value, and rent-seeking behavior, this paper has at its center not only economic rationales but also the cultural dimension – from author’s moral rights to cultural creativity and diversity.

4. There is a conventional understanding – emanating from industry, policy, and media circles – that file-sharing severely hurts artists and labels over many years. Yet much of the academic research conducted on this is conflicting and fails to arrive at any consensus (refer to Rogers [Citation2013]). More importantly, this view has ignored new and alternative income sources of revenue such as concerts and sales of other derivative goods (Parc and Kawashima Citation2018; Parc and Kim Citation2020).

5. Regarding the private contract, a similar concept on ‘contract’ between author and agent has been dealt with by Caves (Citation2000) and Thompson (Citation2010). In those works, an agent is a third party that stands between the author and publisher and is viewed positively. By contrast, the contract mentioned in this paper stays between the author and publisher. Hence, here the agent means publisher and it is considered as an untrustworthy entity. In other words, the concept on contract in this paper is completely different from Caves (Citation2000) and Thompson (Citation2010).

6. Public domain is the period beginning after the expiration of the copyright where any firm or individual can utilize and disseminate formerly copyrighted works without paying copyright-based fees to the authors or copyright holders.

7. The English publishers thought that their rights to publish books under exclusivity was common law and should be perpetual. This led to the Battle of the Booksellers which lasted for thirty years and involved a series of legal cases pressing for their rights to prohibit other publishers from printing the works they were in charge of (Rose Citation1993).

8. The timespan of authors is covered in the impact assessment study prepared by the European Commission (Citation2008) for the adoption of the 2010 Directive, which reads: ‘This impact assessment shows that many European musicians or singers start their career in the early 20’s. That means that when the [.] 50-year protection ends, they will be in their 70’s and likely to live well into their 80’s [.]. As a result, performers face an income gap at the end of their lifetimes.’

References

- Akerlof, G. A., K. J. Arrow, T. F. Bresnahan, J. M. Buchanan, R. H. Coase, L. R. Cohen, M. Friedman, et al. 2002. The Copyright Term Extension Act of 1988: An Economic Analysis. Washington, DC: AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies.

- Aksikas, J., and S. J. Andrews. 2014. “Neoliberalism, Law and Culture: A Cultural Studies Intervention after ‘The Juridical Turn’ Introduction.” Cultural Studies 28 (5–6): 742–780. doi:10.1080/09502386.2014.886479.

- Australian Productivity Commission. 2016. “Intellectual Property Arrangements.” Inquiry Report, No. 78, December. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

- Balázs, B. 2011. “Coda: A Short History of Book Piracy.” In Media Piracy in Emerging Economies, edited by J. Karaganis, 399–413. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Social Science Research Council. Accessed 24 December 2019. http://piracy.americanassembly.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/MPEE-PDF-1.0.4.pdf

- Baldwin, P. 2014. The Copyright Wars: Three Centuries of Trans-Atlantic Battle. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Benkler, Y. 2006. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Boldrin, M., and D. K. Levin. 2008. Against Intellectual Monopoly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buccafusco, C., and P. J. Heald. 2013. “Do Bad Things Happen When Works Enter the Public Domain? Empirical Tests of Copyright Term Extension.” Berkeley Technology Law Journal 28 (1): 1–43.

- Callahan, M., and J. Rogers. 2017. A Critical Guide to Intellectual Property. London: Zed Books.

- Cargill, O., and P. A. Moran. 1971. “Copyright Duration V. The Constitution.” Wayne Law Review 17: 917–929.

- Caves, R. E. 2000. Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce. Cambridge, and London: Harvard University Press.

- Chamberlain, C. 2016. “Tailoring Copyright Duration.” Lewis & Clark Law Review 20 (1): 303–331.

- European Commission. 2008. Impact Assessment on the Legal and Economic Situation of Performers and Record Producers in the European Union, SEC. 2008. 2287. Accessed 2 October 2019. http://www.ipex.eu/IPEXL-WEB/dossier/document/SEC20082287FIN.do

- European Union (EU). 1993. “Council Directive 93/98/EEC Harmonizing the Term of Protection of Copyright and Certain Related Rights.” Official Journal of the European Communities L290 36 (November 24): 9–13.

- Giblin, R. 2017. “Reimagining Copyright’s Duration.” In What If We Could Reimagine Copyright?, edited by G. Rebecca and K. Weatherall, 117–221. Acton: Australian National University Press.

- Gillespie, T. 2009. “Wired Shut, Copyright and the Shape of Digital Culture.” Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society 7 (2/3): 213–218.

- Gowers, A. 2006. Gowers Review of Intellectual Property. London: Her Majesty Treasury.

- Hatch, O. G. 1998. “Toward a Principled Approach to Copyright Legislation at the Turn of the Millennium.” University of Pittsburgh Law Review 719: 719–757.

- Hesmondhalgh, D. 2009. “3a. Digitalisation, Music and Copyright.” In Creativity, Innovation and the Cultural Economy, edited by A. C. Pratt and P. Jeffcutt, 57–73. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hugenholtz, B. P., M. van Eechoud, S. van Gompel, and N. Helberger 2012. “The Recasting of Copyright & Related Rights for the Knowledge Economy.” Amsterdam Law School Research Paper No. 2012-44; Institute for Information Law Research Paper No. 2012-38. Accessed 1 October 2019 https://ssrn.com/abstract=2018238

- Johns, A. 2009. Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Karaganis, J., ed. 2011. Media Piracy in Emerging Economies. Brooklyn, N.Y: Social Science Research Council. Accessed 24 December 2019. http://piracy.americanassembly.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/MPEE-PDF-1.0.4.pdf

- Kretschmer, M. 2008. “Creativity Stifled? A Joined Academic Statement on the Proposed Copyright Term Extension for Sound Recordings.” European Intellectual Property Review 30 (9): 341–374.

- Kretschmer, M. 2010. “Copyright and Contract Law: Regulating Creator Contracts: The State of the Art and a Research Agenda.” Journal of Intellectual Property Law 18 (1): 141–172.

- Kretschmer, M., and F. Kawohl. 2004. “The History and Philosophy of Copyright.” In Music and Copyright, edited by S. Frith and L. Marshall, 21–53. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Landes, W. M., and R. A. Posner. 1989. “An Economic Analysis of Copyright Law.” Journal of Legal Studies 18: 325–333.

- Landes, W. M., and R. A. Posner. 2003. “Indefinitely Renewable Copyright.” The University of Chicago Law Review 70 (2): 471–518.

- Lessig, L. 2004. Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock down Culture and Control Creativity. New York: Penguin Press.

- Liebowitz, S. J. 2007. “What are the Consequences of the European Union Extending Copyright Length for Sound Recordings?” Prepared for International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI).

- McInytyre, H. 2014. “At 2 Billion Views, ‘Gangnam Style’ Has Made Psy a Very Rich Man.” Forbes, 16 June. Accessed 21 August 2020 https://www.forbes.com/sites/hughmcintyre/2014/06/16/at-2-billion-views-gangnam-style-has-made-psy-a-very-rich-man/#647877a33fdb

- Narayana, M. P. 1985. “Managerial Incentives for Short-Term Results.” The Journal of Finance 40: 1469–1484.

- Parc, J. 2020. “Rethinking Copyrights: The Impact of Copying on Cultural Creativity and Diversity.” In Creative Context: Creativity and Innovation in the Media and Cultural Industries, edited by N. Otmazgin and E. Ben-Ari, 143–162. Singapore: Springer.

- Parc, J., and N. Kawashima. 2018. “Wrestling with or Embracing Digitization in the Music Industry: The Contrasting Business Strategies of J-pop and K-pop.” Kritika Kultura 30 (31): 23–48.

- Parc, J., and S. D. Kim. 2020. “The Digital Transformation of the Korean Music Industry and the Global Emergence of K-pop.” Sustainability 12 (18). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187790

- Parc, J., and H.-C. Moon. 2019. “Accumulated and Accumulable Cultures: The Case of Public and Private Initiatives toward K-Pop.” Kritika Kultura 32: 429–452.

- Parc, J., P. A. Messerlin, and H.-C. Moon. 2016. “The Secret to the Success of K-pop: The Benefits of Well-Balanced Copyrights.” In Corporate Espionage, Geopolitics, and Diplomacy Issues in International Business, edited by B. Christiansen and F. Kasarci, 130–148. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Rajan, M. T. S. 2011. Moral Rights: Principles, Practices and New Technology. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reichman, J. H. 1996. “The Duration of Copyright and the Limits of Cultural Policy.” Cardozo Arts and Entertainment Law Journal 14: 625–654.

- Rogers, J. 2013. “Death by Digital?” In The Death and Life of the Music Industry in the Digital Age, edited by J. Rogers, 25–70. London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney: Bloomsbury.

- Rose, M. 1993. Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

- Schlesinger, P. 2017. “The Creative Economy: Invention of a Global Orthodoxy.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 30 (1): 73–90.

- Schlesinger, P., and C. Waelde. 2012. “Copyright and Cultural Work: An Exploration.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 25 (1): 11–28.

- Spender, L. 2009. Digital Culture, Copyright Maximalism and the Challenge to Copyright Law. Sydney: University of Western Sydney.

- The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2017. Copyright. Accessed 3 March 2019. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/creativity/creative-industries/copyright/

- The United States Copyright Office. 2017. Copyright Law of the United States. Accessed 3 March 2019. https://www.copyright.gov/title17/

- Theofilos, S. 2013. “A Copyright Extension for EU Recordings.” Music Business Journal. December. Accessed 3 March 2019. http://www.thembj.org/2013/12/copyright-extension-for-european-sound-recordings/

- Thompson, J. B. 2010. Merchants and Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Towse, R. 1999. “Copyright and Economic Incentives: An Application to Performers’ Rights in the Music Industry.” Kyklos 52 (3): 369–390.

- Towse, R. 2003. “Copyright and Cultural Policies for Creative Industries.” In Economics, Law and Intellectual Property, edited by O. Granstrand, 419–438. Boston, Dordrecht and London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Vaidhyanathan, S. 2001. Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How It Threatens Creativity. New York and London: New York University Press.

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). 2017. Copyright. Accessed 3 March 2019. http://www.wipo.int/copyright/en