ABSTRACT

The media discourse on Russia’s war in Ukraine heavily focuses on geopolitical and military explanations of this conflict, with Ukraine often serving as a metaphor for preserving European values. However, a discussion of what these values mean and how ‘Europeanness’ is experienced from the perspectives of everyday life on the war-torn territories is rare. This article addresses these questions through a reading of the Wartime Diary which Yevgenia Belorusets, a Ukrainian photographer and writer, started keeping on 24 February 2022. We focus on the private/public form of this diary which, while staging the author’s intimate dialogue with herself, was published in ‘foreign’ languages (German and English), and incorporates both personal and other people’s testimonies. Drawing on the diary and its remediations as installations, we suggest that these works create a ‘chronotope of immediacy’ by mediating the experiences of ‘ordinary’ people. As such, they do not only enable readers/viewers from outside of Ukraine to follow the daily rhythms of life during war but also implicate each individual (and particularly each European, given the place of the publications and exhibitions) into the events. Thus producing ‘implicated publics’, these works can help to rethink ‘Europeanness’ in the context of the war.

Introduction

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Western media have been swamped with explanations of the war as well as deliberations on how states should intervene. In these debates, positions regarding military and political actions commonly rely on the cultural linking of Ukraine to Europe.Footnote1 Headlines such as ‘Ukraine: A Battle over the Future of Europe’ (Politico 22/12/2022), ‘Ukraine Is Our Past and Our Future’ (Time 06/04/2022), and ‘How Does This War End for Europe?’ (Visegrad Insight 15/12/2022) demonstrate a preoccupation with the temporal-spatial meanings of Ukraine for conceptions of Europe, with the former serving as a metaphor for defending the continent’s future. Such attempts in the public sphere to ‘map’ Ukraine, however, do not automatically create a better understanding of the country, as historian Olesya Khromeychuk has warned with her statement that ‘Ukraine has existed on the official map of Europe for at least 30 years’, and yet ‘it was mostly missing from our mental maps.’ (Citation2022, 27)

Mental maps, according to Khromeychuk, are different from the political, historical, and military maps pervading the media discourse on the war; instead, they are informed by the more intimate personal knowledge of a country or place. (Citation2022, 27) Building on Khromeychuk’s plea for creating a more nuanced mental map of Ukraine, this article asks how ‘Europeanness’ is reflected on from the perspectives of everyday life on the war-torn territories, a take that is still rare in discussions about the war. We address this question by focusing on Yevgenia Belorusets’ Wartime Diary, an account of the first 41 days of the full-scale invasion from her home in Kyiv. Belorusets, a Ukrainian photographer, writer, and activist, incorporated both texts and photographs in the diary, which share personal impressions of the war as well as testimonies of friends, neighbours, and strangers she encounters in the city. The combination of written accounts of trauma and images that we encounter in the Wartime Diary is reminiscent of intermedial works such as Maybe Esther [Vielleicht Esther] (2014) by the Ukrainian-German author Katja Petrowskaja, who, like Belorusets, carefully reflects on the interplay between (autobiographical) documentality and fictionality in interpreting the past and present. The entries from Belorusets’ diary were published daily in German by Der Spiegel as well as in English translation by Isolarii.Footnote2 Parallel to this, the author reworked selected diary entries into two art installations entitled A Wartime Diary and One Day More, which were exhibited in 2022 at the 59th Venice Biennale and the Citizens’ Garden of the European Parliament in Brussels, respectively. The Wartime Diary also inspired the exhibition Nebenan/Close by in the German Bundestag which Belorusets’ personal homepage describes as a ‘memory map’ that reconstructs the beginning of the war day by day (Belorusets Citation2022b). Other remediations of the diary include public readings at the event ‘Read for Ukraine: A Literary Dispatch from Kyiv to New York’ by Margaret Atwood in March 2022 and on the podcast This American Life in April 2022.Footnote3 By negotiating between the private and the public sphere, as well as between diverse Ukrainian and international audiences, we suggest that Belorusets’ diary, along with its artistic remediations, encourages us to rethink ‘Europeanness’ in the context of the war.

In what follows, we first explore how the Wartime Diary imagines Ukraine’s temporal-spatial place within Europe. We argue that the process of interweaving personal, intimate observations about the war with accounts of others constitutes a chronotope that protects memories of everyday life and de-normalizes war. By mediating these experiences to (European) publics abroad, both through the diary and the above-mentioned installations and exhibition, Belorusets counters the politics of fear often found in mainstream media. By fostering an ethics of care instead, she produces what we call, drawing on Michael Rothberg’s term, ‘implicated publics.’ The specific form of ‘collective’ storytelling that Belorusets adopts is not without its challenges, however. In the second part of our article, we turn to Belorusets’ approach to the ethics of documenting personal and other people’s testimonies of living through war, and reflect on her use of stories and photographs in creating an archive or ‘memory map,’ as she calls it, of the present.

Zoomed-in time/interlinked places: protecting memories of daily life and producing implicated publics

‘Every entry should be the last.’ These words form a leitmotif of Belorusets’ Wartime Diary and its ‘translations’ into the installations. This motif conveys a normative ethical standpoint as we read in Belorusets’ preface to her diary: ‘My wish was always to project this vision, to show how important it is to end the war immediately and, in doing so, to preserve a very complex picture of reality during wartime.’ (Citation2022a, 30) The temporality of ‘one day’ thus mediates a call to end the war and to preserve a memory of what was happening, or rather, to preserve a constellation of many ‘minor,’ everyday memories.

In times of war, and for those who witness an offensive on their home, time slips away from the habitually perceived linear trajectory. Belorusets’ diary repeatedly registers the sense of a single day’s stretched duration: ‘My day has been long and feels like it had several days locked up in it;’ (Citation2022a, 97) ‘Tomorrow seems an eternity away […]. One can imagine tomorrow in theory, but not as a moment in one’s own passage of time – only as a story one tells oneself.’ (Citation2022a, 135) As these quotations show, zooming in on the details of daily life, stretching time, and making it maximally concrete organizes the diary works.Footnote4 This transformation of time takes place in a close dialogue with the reshaping of space; the two form a chronotopeFootnote5 that mediates personal experiences of the war in Kyiv to international audiences. By focusing on the rhythms, focalizations, and dynamics of de- and re-familiarization created by this chronotope, we can see how it counters mainstream reporting that sensationalizes war and normalizes violence. Instead, this chronotope of zoomed-in time/interlinked places generates possibilities of concrete connections and, as our reading will show, produces ‘implicated publics.’

This chronotope can be described as the time-space of immediacy and concreteness. ‘One day’ (that can stretch beyond the duration of clock time) acts as an imaginary measurement of war time that needs to be ended. The day-long unit of a diary provides a form for ‘managing’ catastrophic time and dealing with the experience of war in its singularity. This rhythm and the real-time transmission of witnessing through the online publication of daily entries resemble news reporting, yet in quite significant ways, the diary creates its publicFootnote6 differently compared to conventional media reportage. The latter, typically, addresses readers/viewers by representing the terror and suffering caused by war and by celebrating heroism. As Susan Sontag observed, ‘photographs of the victims of war are themselves a species of rhetoric. They reiterate. They simplify. They agitate. They create the illusion of consensus.’ (2003, 6) While photographs (and we could add, diary-writing that ‘freeze-frames’ fleeting impressions of a day) fulfil an important function by rendering violence visible to those who are removed and protected from it, Sontag insists that the ethics of producing and receiving images requires a sense of fundamental difference between the experiencing and the viewing subjects. (2003, 7)

Belorusets’ diary works avoid these pitfalls while, similar to war reporting, they create an awareness of violence and urge transnational solidarity. The texts and images in the diary emphasize how, during early 2022, for the majority of Ukrainians the Russo-Ukrainian war evolved from a lingering military conflict to the states of emergency and terror. The time of emergency, however, is not apocalyptic; it escapes generalization through a portrayal of the rhythms of everyday life under extraordinary circumstances and by focusing on the acts through which people in Kyiv carve out new rituals to maintain life in the face of imminent danger. Thus, the zoomed-in time of the everyday is being matched by the concreteness of places, interlinked through stories and photographs. The spatial construction of the diary could be compared to a network created by the limited physical movement of the author through the city (always risky due to shelling) and her imaginary travel, through personal memories and photographs, or stories of others, to other places in Ukraine that are being attacked and destroyed by the Russian troops. In other words, the diary represents the city and national spaces not as a generalized unity, but as constellations of specific places and interactions with them.

Every single day becomes a space of encounters between the author and other people whose photographs accompany the entries. Sometimes, these are portraits of people posing for the camera, at other times, silhouettes moving across urban space or observing the destroyed sites of the city. Often, the diary describes the encounters with these protagonists, thus adding context to the images. The images themselves form the sites of mediated encounters between the photographer and the photographed, as well as between the latter and the reading/viewing audiences. Both types of encounters are facilitated by the quotidian contexts and types of interactions that readers/viewers can relate to: buying tulips on the first sunny days of spring; visiting a playground with a child; walking a dog. However, without exception the photographs also remind us that these everyday acts take place in the face of war.Footnote7

One of the most poignant photographs depicts a woman (Polina Veller, a Kyiv-based artist who was staying in the city with her husband and small daughter) wearing a mask crafted out of plastic cable ties in the colours of the Ukrainian flag ().

The photo, Belorusets writes, made her think about ‘the absurdity of basically any activity in the face of current events’ and, in the same breath, ‘the idea that you keep going despite it all.’ (Citation2022a, 137) This performance of resistance of and through the everyday invokes the figure of vulnerability and the way it has been theorized by feminist scholars as a site of political agency, manifested through ‘embodied political intervention’ and a ‘mode of alliance […] characterized by interdependency and public action’ (Butler, Zeynep, and Leticia Citation2016, 7).The encounters and acts of care represented in the diary create (sometimes unexpected or fleeting) connections between people and places without suggesting the existence of a unified ‘we.’ Belorusets is careful not to construct any sense of easily shared suffering; instead, she emphasizes the relative safety and privilege of staying in Kyiv even when the city is constantly under attack. From here, she mentally travels to places that experience heavier destruction, and draws connections without pretending to know what it feels like to be there. After mentioning that fighting around Kyiv continues, she writes:

But my thoughts are with Kharkiv. I see the images of apartment blocks destroyed by rockets and mortar shells and know that today Putin’s army murdered nine people, including three children […]. Thirty-seven people are injured, eighty-seven apartment buildings ruined. I live in Kyiv in a similar building […], where I always feel so good. Even now! Even now! (Citation2022a, 74)

The situatedness of the narrative perspective that interrelates and ‘synchronizes’ events in different parts of Ukraine counters the de-personalization of war reporting. It also avoids a vision of a generalized national unity that typically rests on chronotopes entwining homogeneous space and progressive time.Footnote8 The importance of mediating ordinary people’s perspectives and forming connections between individuals rather than states is a constant in Belorusets’ work. In a recent entry to her online diary, dated 24 February 2023, she stresses the necessity of moving away from ‘war analysis where countries or even national associations are what matters, not people’ (Belorusets Citation2023). She continues by critiquing the tropes commonly used in international reporting: ‘Ukraine is “heroic” and it “fights for its freedom,” “it sees itself protecting the whole of Europe.” The experts I sometimes listen to while falling asleep often call themselves “friends of Ukraine”’ (Belorusets Citation2023, isolarii.com). This critique is preceded by the author’s recollection of how, as a small child, she used to fear falling asleep and dream of being eaten by a dragon; the adults would dismiss her stories and insist that she obeys the rules. Placing this allegory against her scrutiny of the discourses of international politics, we see an analogy between the adults who claim to have universal knowledge and politicians or newsmakers who instrumentalize visions of Ukraine as an example of national cohesiveness from which Europe should learn; both cannot intimate what those who are subjected to violence feel, know, and remember. From the first entries of her diary, Belorusets posits her subjects as those who are not heard by ‘the international community:’

It feels strange to find myself in this broad, unarmed, almost delicate category: ‘civilians.’ For war, a category of people is created who live ‘outside the game.’ They are shelled, they have to endure the shelling, they are injured, but they do not seem to be able to give an adequate response to it. (Citation2022a, 59-60)

The diary works speak eloquently against this de-personalized vision that normalizes war: they constitute their publics by creating dialogic possibilities for recipients from elsewhere to follow the daily rhythms of life in a war zone. Drawing on Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s concept of the civil contract of photography, Belorusets’ photographs as well as her diary works as an aesthetic whole can be read as creating ‘a space of political relations between those who are governed, a space in which the demand not to be ruled in this way becomes the basis for every civil negotiation’ (Azoulay Citation2008, 16). Following this concept, photographs frame spectatorship as a ‘civic duty towards the photographed persons,’ particularly if they are ‘dispossessed citizens,’ by stressing that they not only were there during the act of photographing but also remain there as the viewers are ‘watching’ photographs (Azoulay Citation2008, 16–17). The act of watching, i.e. extended and reflective engagement with photography, is encouraged by the intermedial structure of Belorusets’ diaries in which every photographic image contains a story, part of which is unfolded as a narrative. According to Azoulay, these encounters between the photographed and the viewers mediated by the camera enable a rethinking of citizenship as they create a relation of equality between those who have and do not have citizen rights within a polity. Applying this idea which was developed in the context of Israel/Palestine to encounters between people in the besieged city of Kyiv or other places in Ukraine and viewers with no direct experience of this war extends the boundaries of the civil contract beyond a nation-state or even two nations. These are the meetings of differentially positioned subjects who, despite their diverging experience and levels of vulnerability, are participants in the regimes of governmentality that determine the unfolding of the war. By interconnecting and interpellating subjects in the war zones and those who are seemingly outside this war, the diary works enable solidarity and collectivity that produce international publics anew.

The diary-based installations exhibited at the Venice Biennale, the Bundestag in Berlin, and the Citizens’ Garden of the European Parliament in Brussels enable an even closer connection by materializing the encounter between the diary and its (European) recipients. This encounter is mediated by the same chronotope of zoomed-in time/interlinked places. The Venice exhibition was organized spatially as a series of desks, each focused on a single day in the dairy (). Each desk faced a column, creating a secluded space. The desks displayed the printed text of an entry along with the photographs taken on that day. The chairs invited viewers to take a seat and immerse themselves in reading and looking at the images, thus providing a space of contemplation and direct interaction with the exhibits while at the same time placing them in the imaginary place of the author sitting at her desk in Kyiv writing the diary.

The Berlin exhibition was organized more conventionally, with photographs displayed on the walls forming separate sections, although these included images from different days (). The photographs were accompanied by short hand-written notes by the author – usually a sentence or two from a diary entry. The texts of the full entries were not exhibited, but visitors were invited to listen to the author’s recordings of the diary by using headphones at the desks facing the photo displays. This encounter involved less possibility of contemplation, although the author’s handwriting and voice created a sense of immediacy.

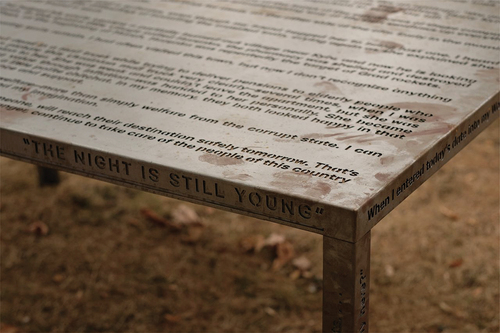

The installation displayed in the Citizens’ Garden of the European Parliament in September-October 2022 was commissioned by the EUNIC (EU National Institutes for Culture) Brussels and the Culture of Solidarity Fund Ukraine of the European Cultural Foundation. Here, again, the space of a table and the diary text organize the viewers’ encounter with the war through the chronotope of immediacy. The installation consists of a metal table with the text of a diary entry (Day 13, March 8) engraved in its rusted surfaces (). The table was produced in the Kharkiv region and transported to Brussels by a vehicle carrying the possessions of refugees. Rusted iron, Belorusets explains, represents the qualities of collective memory which will remember the major events of the war, while the ‘minor’ acts of the everyday risk being ‘forgotten’:

… it is important for me to make the surface vulnerable, to let it corrode, as our memories corrode and also our ability to live through this situation which is absolutely traumatic for everyone. When history changes so quickly and so painfully, the intentions, the worldviews that were expressed at a certain time can lose their meaning and become unavailable. However, we try to preserve memories. (Perepadya/Belorusets Citation2022, translated from German)

The metaphor of vulnerability that interconnects the surface of the table, memories of daily life during war, and strategies of everyday resistance also recalls images of ruins in Ukrainian cities caused by the Russian army. However, instead of shocking media images, this installation, like Belorusets’ other diary works, creates a space of mourning and conversation which everyone around the table can join. Placed on the premises of the European Parliament, this installation can be interpreted as a gesture of hospitality by an Ukrainian artist inviting others to join remembrance and conversation through the intimate acts of reading and watching. The ‘civil contract’ generated by these encounters, similar to the case of the photographs and texts within the diary, enables a rethinking of Europeanness by centring the agency of Ukrainian subjects.

Writing about the ethical impossibility of creating communities through photographs of atrocities, Sontag insisted that those who have not experienced war should always treat it as unimaginable (Sontag Citation2003, 125). Belorusets remains faithful to this proposition by refusing to submit to the war’s logic: ‘I can’t imagine it. The days of the war should not draw to a close just like any other days in life. Someone has given this war permission. The world has deliberated, doubted, and still allowed it’ (Belorusets Citation2022a, 245-246). This refusal, paired with intensified, zoomed-in time, also speaks about the responsibility of ‘the world.’ Here, Belorusets refers to politicians who ‘deliberated’ but still ‘allowed’ the war to happen. However, since the diary works speak primarily to ‘ordinary’ readers and viewers, this injunction can be interpreted as ‘implicating’ each individual (and particularly each European, given the place of the publications and exhibitions) into this ‘unimaginable’ war.

Michael Rothberg’s concept of implication allows for considering the positionality and responsibility of those who are ‘less “actively” involved [in injustice] than perpetrators,’ yet ‘do not fit the mould of the “passive” bystander, either.’ (2019, 1) This perspective urges us to extend the vocabulary of dealing with violence, particularly in its everyday manifestations, ‘beyond the unavoidable categories of victims and perpetrators’ to address ‘the need for a larger reckoning with both the structures of power that undergird such cases and the histories that continue to resonate as afterlives.’ (Rothberg Citation2019, 10) While Rothberg developed this concept in the contexts of generational or geographical distance from acts of violence (e.g. of transatlantic slavery, when considering present-day racialized inequalities in the West, or of Israel/Palestine, from a position of Jews who are not Israeli citizens), we propose that this concept can be applied – and further theorized – for understanding the potential reconfigurations of ‘Europe’ and Europeanness in the context of the Russo-Ukrainian war. In particular, this concept can help to conceive of this reconfiguration not simply as a creation of new cultural entities that include some while excluding others, but as tackling social inequalities that are underpinned by culturally constructed distinctions. Belorusets’ diary works speak to European publics, regardless of citizenship or nationality, as possible allies and, through this act of enunciation, shape these publics as feeling a personal connection to Ukrainians’ daily experiences of war. In particular, they address the relation of institutionalized and culturally accepted ignorance regarding Ukraine which is a relation of coloniality – by inviting the viewers/readers to review the perception of Ukrainians as (related) ‘others.’

Following Rothberg’s theorization of structural and genealogical aspects of responsibility for ‘the pain of others,’ in order to disrupt relations of coloniality and generate possibilities for justice, gestures of solidarity by allies need to involve an inquiry into their positionality within structures of oppression. On a structural level, Belorusets’ works activate a sense of (indirect) responsibility among those who ignored Russia’s aggression in Ukraine since 2014 and benefitted from Russian natural resources and markets as well as Ukraine’s cheap agricultural produce and human resources (migrant workers, especially in the care sector). From a diachronial perspective, by representing war as a crime that needs to be stopped immediately, her writing and photography resist the long histories of normalization of ethno-nationalism and violence in Eastern Europe (Todorova Citation2009) as well as of Russia’s imperial politics towards its neighbours. By drawing readers and viewers into the world of differentiated but dialogically interrelated perspectives of people experiencing the war in Ukraine, the diary works implicate individuals. At the same time, they generate what could be called ‘implicated publics’ as they produce an array of public discussions via the remediations as well as the accompanying media publications and responses by representatives of European cultural institutions or renowned figures such as Margaret Atwood.

‘Please don’t take my picture! Or they’ll shoot me tomorrow!’ The ethics of collective storytelling

‘Tell me, does a camera really bear any relationship to war? Or to murder?,’ Belorusets asks in a discussion of her photograph series Victories of the Defeated, which features industrial labourers and coal miners working on the war-torn territories of Eastern Ukraine between 2014 and 2017 (Belorusets Citation2015). This heavy question is provoked by one mine worker’s worry about being captured on camera:

Just then, you came up to me, and probably as a joke, you said: get out of here! You’re not from here. You’re bothering us. And besides, it’s probably no coincidence you’re here. You’re investigating us with your camera. You’re taking pictures here now, and tomorrow, they’ll come and fire shells at us. (Belorusets Citation2015)

The photograph accompanying the recounted dialogue depicts a close-up of a miner’s soot-covered face, his pale blue eyes peering through a cloud of cigarette smoke (). To shoot with a camera, or with a gun: as journalist and writer Katja Petrowskaja points out in her reading of the image, the coal miner’s remark invokes the double meaning of this verb. (Citation2022, 8) We encounter similar confrontations in the Wartime Diary where Belorusets is repeatedly asked to put away her camera or to delete the photographs she has just taken:

A man approached and said that he’d noticed me looking at the street through the viewfinder of my camera. ‘I’d like to warn you,’ he said, ‘in these times you can get shot in the head for that!’ I replied in amazement that I was just doing my job as a journalist. Then he said, ‘In that case, maybe it’s alright.’ […] Tension grows in the city. A camera symbolizes an eye that can be aimed at anyone. Photography becomes even more suspicious than usual. (Citation2022a, 137-138)

Part of Victories of the Defeated was shown in the Ukrainian Pavillon’s exhibition Hope! at the 56th Venice Biennale as well as in the exhibition Das ist nicht meine Geschichte! [It is not my history!] (2017) at Steirischer Herbst in Graz. With the title of the photograph series, Belorusets focuses not on the ‘winners of history’ whose voices are usually foregrounded but, in a manner reminiscent of Spivak’s essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ (1985), on the ‘unwritten stories of those, who for one reason or another are not ready to speak’ (Belorusets Citation2014–2017).

The series’ intimate portraits of the workers tell a story that is usually absent from war reporting. The vulnerability of eyes looking directly in the camera, or of people cleaning themselves after their shift stands in stark contrast to the detached (visual) language we regularly encounter in the media. The deliberately ‘imperfect’ quality of Belorusets’ photographs, which are often slightly skewed or appear unfocused, underlines the precarity of working in a war zone, and portrays the miners as individuals rather than as abstract words or numbers on paper. In the Hope! exhibition in Venice, Belorusets reflected on the Western media discourse that developed during the first years of the Russo-Ukrainian war by juxtaposing her photographs with a blown-up image of a newspaper headline reading ‘Today’s Photo-Story Is Tomorrow’s Artillery Target’ (). Commenting on the war fatigue with which even such shock-provoking titles are met by international readers, she writes:

Recoiling in horror? I bet you are. The journalist is making you read yet another dispatch from this inglorious war in the east of a European country of minor importance, a war being fought for reasons unclear even to the people fighting it. How tired we are of this war! […] Surely it’s about time you chucked in some other news – something in slightly better taste? […] Just walk on by, it’s fine. (Belorusets Citation2015)

Victories of the Defeated does not simply criticize or fill in some of the gaps left in the Western media discourse on the war. Confronting international readers and viewers with their ‘dulled’ emotional response to news from Ukraine in the Hope! exhibition, Belorusets counteracts the ‘comfortable’ abstraction of war reporting with the intimate nature of her photographs, stressing that this, too, is Europe. However, the confrontational question by the mine worker cited further above also prompts us to reflect on the ethics of mediating stories and portraits of other people,Footnote9 especially those who often remain unheard, as a way to facilitate such encounters with international publics. Before we turn to the question how the diary approaches this challenge, it helps to return to Belorusets’ earlier work.

In the introductory note to her book Lucky Breaks (2018), Belorusets explains that she is interested in the ability of stories and photographs to ‘[escape] the author’s final control over the materiality of past events, encounters, conversations, histories.’ (2018, 7) Lucky Breaks consists of a series of fictionalized tales of women living in or having fled the war zone in Eastern Ukraine. The particular mix of real-life stories of women living in the shadows of the conflict with fiction and photography, Belorusets argues, should induce a clash between different voices, contexts, and artistic media, and result in a ‘rejection of any instruments of certainty,’ including the author’s own role in the narrative. (2018, 8)

Lucky Breaks is a work of fiction, Belorusets underlines in an interview with Tetiana Bezruk for Open Democracy, who confronts her with the potential dangers of interweaving oral histories with fictional narratives. ‘Any document,’ the author counters, ‘is partly a lie, and this is especially true of documentary photography, which only ever conveys a small part of reality’ (Bezruk and Belorusets Citation2018). However, she continues, documents also lie ‘at the heart of our political action, our ability to act: we believe the document and it spurs us into action.’Footnote10 (Belorusets Citation2018) The latter thought seems to become particularly important with regard to photography as a medium to which people – perhaps more than to language – turn in times of war in order to grasp what appears unimaginable. ‘While language can be deceptive,’ Belorusets writes in the diary, ‘a photograph seems to capture something irrevocably and at the same time speak for itself. One wants to give an account, not with words, but with the irrefutable image.’ (Citation2022a, 286) However, the urge to ‘archive’ the present with photography also becomes a frequent source of disappointment throughout the diary, which recalls Belorusets’ first statement about the subjectivity and selectiveness of any form of documentation. Her entry from 5 April 2022, for example, is accompanied by a slightly blurred photograph of a landscape taken from a train moving from Kyiv to Warsaw (): ‘At some point along the way, I forced myself to take a picture of the landscape through the dusty train car window so that I wouldn’t forget what I was going through at that very moment. But it was in vain. All these experiences and memories seem impossible to contain.’ (Citation2022a, 409)

Despite what feels like a ‘broken photographic lens’ [‘eine gebrochene fotografische Optik’], as Belorusets writes in the preface to the German edition of the Wartime Diary (Citation2022c, 8), the entries, we have suggested, create a sense of proximity for their readers via the chronotopes that entwine ‘immediate’ time and space. On the level of storytelling, this is achieved by combining personal impressions of the war with, and this is different from earlier work such as Lucky Breaks, non-fictionalized experiences of others, thus resembling what Helga Lenart-Cheng calls ‘assembled stories.’ (Citation2022, 4)

In Story Revolutions, Lenart-Cheng examines the role that collective storytelling plays in the establishment of ‘personalized communities’ that reconnect the individual to the communal through personal, yet at the same time interlinked stories. (2022, 5) Whilst critical of the ‘utopian fantasies’ that this idea evokes (2022, 7), she points to the impact that collective story sharing can have on forms of participatory democracy by making concepts such as ‘democracy’ less abstract and de-individualized. (2022, 5) If we apply the latter thought to the diary, it is interesting to note that Belorusets repeatedly indicates that the abstract language of political and media discussions about the war can at times also provide a sense of temporary relief from listening to and sharing individual stories of violence and trauma, both of herself and others:

[…] by leaping into a distant news stream, one can slowly accept what is happening to my country. At the same time, such a thought is unbearable. I push it away. Besides, I know that ‘my country’ sounds abstract enough as an idea that one could be able to ‘accept’ what is happening – but you can never understand how something so brutal can be done to people. (Citation2022a, 293-294)

Unlike Lucky Breaks – and also different from some of the online crowdsourced diaries analysed by Lenart-Cheng – Belorusets’ role as the author who interprets and frames the narrative remains visible throughout the diary. In several instances, she reflects on this by, for example, hesitating before speaking to a stranger she encounters in the city. The way in which Belorusets integrates the stories of others in her own narrative resembles what Lenart-Cheng refers to as ‘relationality,’ a term that underlines the presence of others in one’s own story (2022, 6). The fact that Belorusets at no point equates her experiences with those of friends or strangers, as well as her repeated references to the selectivity of the wartime archive she creates as a writer and photographer – ‘[a]fter the war, my files will contain almost no pictures of soldiers or ruins’ (Citation2022a, 356) – produce an authentic and relatable effect for readers. The diary thus navigates between personal and communal experiences of living through war, while laying bare the ethical constraints and subjective decisions that underlie the creation of an archive or ‘memory map’ of the present. In a recent diary entry from 9 January 2023, Belorusets reflects on the difficulties of truly capturing and preserving memories – but concludes that the ‘imperfect’ attempt at doing so can itself induce a freeing effect:

Memories can be occupied just as cities can. But for the most part they do not possess the modern defensive weapons that Ukraine asks for again and again. […] Memory, it’s difficult to write it all down, the sentences seem to want to separate from themselves. And yet I feel, as I write, that the events of my childhood, surrounded by war, begin to exist outside the all-encompassing front line. (Belorusets Citation2023, isolarii.com)

Belorusets’ reflections on the power and limitations of documenting the present almost seem like a direct response to a recent warning by the Ukrainian feminist philosopher Irina Zherebkina, who in her ‘Afterword to “Diary of War”’ published in e-flux observes a ‘hegemonic struggle’ taking place to fill the word ‘victory’ with different political agendas and ideologies (Zherebkina Citation2023). Rather than filling this ‘empty master signifier,’ as Zherebkina (Citation2023) puts it, with one definitive story, Belorusets shows both the plurality and precarity of life on the war-torn territories, implicating us in the need for Ukraine’s victory.

Conclusion: ‘Das ist mein Krieg/It is my war’

In February 2023, an installation created by Belorusets with the inscription ‘Das ist mein Krieg’ [It is my war] was installed at Dresden’s Schlossplatz (). This was a response to the graffiti that had appeared in Berlin in late 2022, featuring the statement ‘Das ist nicht unser Krieg’ [It is not our war], with a line crossing the words. Whether the line was intended by the authors or later added as a response is unknown. Belorusets’ installation continues this dialogue in the affirmative; by crossing and multiplying the first-person singular pronoun (as opposed to the plural ‘we’), it crystallizes the narrative, visual, and participatory strategies that we discussed in her work.

Just like this installation, Belorusets’ wartime diary works create alternatives to the generalized ‘mapping’ of Ukraine by media and politicians who imagine the country as being external to Europe, either praising it as a heroic example for Europeans or referring to it as an apocalyptic sign of the future. Instead, her works address individuals and ‘implicate’ them into the experiences of the war by facilitating the possibility of personal associations without implying undifferentiated collectivity, neither within Ukraine nor connecting an imaginary ‘Ukraine’ and ‘Europe.’ Our readings of Belorusets’ texts, photographs, installations, and the links between them, demonstrated how the chronotope of immediacy (what we called ‘zoomed-in time/interlinked places’) creates a sense of connectedness while stressing the differential positionality of the author in relation to her interlocutors, as well as between their perspectives and external readers/viewers. By preserving everyday memories of the war, while simultaneously laying bare the ethical constraints and subjective decisions that inform such a ‘memory map,’ these works refuse the fear-based logic that dominates news reporting on the war.

As such, Belorusets’ works create dialogic possibilities for people from outside of Ukraine and particularly from various places in Europe (given the location of the exhibitions and publications) to follow the daily rhythms of life in a war zone. By communicating daily experiences of war in/with the effect of ‘real time’ and across a variety of artistic media and languages, they shape ‘a relation among strangers’ (Warner Citation2022, 74). The type of solidarity that they mediate through portraying differentiated vulnerability foregrounds personal involvement: by suggesting to each viewer/reader that the war in Ukraine is ‘theirs,’ by bringing them face-to-face with people living in war zones, Belorusets’ visual and textual works make them contemplate on how exactly they are involved or responsible. The author’s own reflection on her position of potential implicatedness in relation to the marginalized and vulnerable subjects (people living on the occupied territories and in war zones, the elderly, the children) provides an example for such contemplation. Furthermore, by mediating the relationship of implication to European audiences, the diary works encourage reflection on their responsibility to confront and transform the relationship of distance, abstraction, and ignorance towards people in Ukraine on a collective level.

In placing such dialogues within the public spaces of daily online communication as well as key sites of civic and aesthetic engagement in Europe, these acts potentially produce not only implicated subjects but also what can be called ‘implicated publics.’ The reading of the War Diary in German and English as a daily encounter (together with others, like the reading of daily news), the attending of exhibitions and listening to opening speeches by representatives of European political and cultural institutions, the gathering around the table with war testimonies in the Citizen’s Garden – all these acts create potential frameworks for viewers and readers to be activated as members of publics in the making. Such personalized encounters generate public reflection about the viewers’/readers’ relationship between their lives and the lives of people in Ukraine. These encounters also involve the collective – structural and historical – dimensions of confronting one’s implication in the criminal violence of war as related to colonial ignorance. At the same time, these works enable a transformative, ‘refiguring’ relationship of ‘long-distance solidarity’ (Rothberg Citation2019, 200) by mediating experiences of resistance and attitudes of care. Ultimately, by creating frameworks for contemplating responsibility and solidarity within the online and onsite spaces of public deliberation in Europe, Belorusets’ work can help to start reimagining what it means to be ‘European’ in the face of this war.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Of course, the process of (de)linking Ukraine to Europe also plays an important role in Russia’s legitimation for the war.

2. The diary has also been published in book form in English (Wartime Diary by Isolarii) and German (Anfang des Krieges. Tagebücher aus Kyjiw by Matthes & Seitz). The books include additional entries from July 2022, and a foreword covering the years 2014–2022.

3. Margaret Atwood’s reading of the diary can be accessed here: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cbf8VplpP2M/ (Artforum Citation2022). The episode of This American Life is available here: https://www.thisamericanlife.org/768/the-other-front-lines (Other Front Lines Citation2022). This article focuses on the diary and its remediations as installations. We will not discuss the public readings (Ostashevsky Citation2018).

4. By ‘diary works’ we refer to the diary itself as well as the diary-based installations.

5. The concept of the chronotope, as developed by Mikhail Bakhtin, theorizes the interconnectedness of time and space perception and narrativization as constituting a typical vision or shared condition of a particular historical period. The chronotope, according to him, is the sphere where ‘the knots of narrative are tied and untied’ and where ‘the meaning that shapes narrative’ lies (Bakhtin et al. Citation1981, 187).

6. We follow Michael Warner’s understanding of the term ‘publics’.

7. The title of the Ukrainian exhibition at the Venice Biennale and the publication featuring the entire diary.

8. Here, we draw on Walter Benjamin’s notion of ‘homogenous and empty time’ (Benjamin Citation2003, 395) by which he referred to non-materialist constructs that support national(ist) histories.

9. In his discussion of Lucky Breaks, Eugene Ostashevsky identifies the representation of others as the ‘main artistic and ethical problem’ (2018, 103) in Belorusets’ work.

10. We are indepted to Eugene Ostashevsky for drawing our attention to this interview in his insightful afterword to Lucky Breaks (2018, 103).

References

- Artforum. 2022 March 24. “Poet and Novelist Margaret Atwood Reads from ‘Letters from Kyiv’.” Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/Cbf8VplpP2M/.

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. New York: Zone Books.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1981. “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel. Notes Towards a Historical Poetics.” The Dialogic Imagination - Four Essays by Mikhail Bakhtin, edited by Michael Holquist, Cary Emerson and Michael Holquist, 84-258. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Belorusets, Yevgenia. 2014–2017. “Victories of the Defeated.” belorusets.com. https://belorusets.com/work/victories-of-the-defeated.

- Belorusets, Yevgenia. 2015. “Please Don’t Take My Picture! Or They’ll Shoot Me Tomorrow.” belorusets.com. https://belorusets.com/work/please-don-t-take-my-picture-or-they-ll-shoot-me-tomorrow.

- Belorusets, Yevgenia. 2018. Lucky Breaks. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz.

- Belorusets, Yevgenia. 2022a. “The War Diary of Yevgenia Belorusets.” In In the Face of War – Yevgenia Belorusets, Nikita Kadan, Lesia Khomenko, London: Isolarii.

- Belorusets, Yevgenia. 2022b. “Nebenan/Close By. Texts, Photographs, Sounds.” belorusets.com. https://belorusets.com/work/nebenan-close-by.

- Belorusets, Yevgenia. 2022c. Anfang des Krieges. Tagebücher aus Kyjiw. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz.

- Belorusets, Yevgenia. 2023. “A Tale of Fear.” Isolarii. https://www.isolarii.com/kyiv.

- Benjamin, Walter. 2003. “On the Concept of History.” In Selected Writings, edited by Michael W. Jennings and trans. by Edmund Jephrott, Vol. 4, 1938–1940. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bezruk, Tetiana, and Belorusets, Yevgenia. 2018 November 6. “‘We Can’t Use the War to Justify Anything’: Photographer Yevgenia Belorusets on Documenting Ukraine’s Most Vulnerable Groups.” opendemocracy.net. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/yevgenia-belorusets-interview/.

- Butler, Judith, Gambetti, Zeynep, and Sabsay, Leticia. 2016. “Introduction.” In Vulnerability in Resistance, edited by Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Leticia Sabsay, 1–11. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Khromeychuk, Olesya. 2022. “Where Is Ukraine? How a Western Outlook Perpetuates Myths About Europe’s Largest Country.” Royal Society for Arts Journal 2:26–31. https://www.thersa.org/globalassets/pdfs/journals/rsa-journal-issue-2-2022.pdf.

- Lenart-Cheng, Helga. 2022. Story Revolutions. Collective Narratives from the Enlightenment to the Digital Age. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Ostashevsky, Eugene. 2018. “Translator’s Afterword.” In Yevgenia Belorusets. Lucky Breaks, 102–108. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz.

- Perepadya, Olena, and Belorusets, Yevgenia. “‘Dieser Krieg ist eine internationale Katastrophe’.” 2022 September 7. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/de/yevgenia-belorusets-ilb-berlin-ukraine-russland-krieg/a-63046957.

- Petrowskaja, Katja. 2022. Das Foto schaute mich an. Kolumnen. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Rothberg, Michael. 2019. The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Picador.

- The Other Front Lines. 2022 April 22. “Four Personal Stories from the War in Ukraine.” This American Life. https://www.thisamericanlife.org/768/the-other-front-lines.

- Todorova, Maria. 2009. Imagining the Balkans. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Warner, Michael. 2022. Publics and Counterpublics. New York: Zone Books.

- Zherebkina, Irina. 2023 April 27. “Waiting for Victory: Afterword to ‘Diary of War’.” e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/notes/536238/waiting-for-victory-afterword-to-diary-of-war.