ABSTRACT

The work of 1930s writers Antonin Artaud, Stanley Weinbaum, and Max Herrmann, reveals an early history of Virtual Reality and a burgeoning interest in how the virtual can be concretized through experiences requiring the complicity of willing participants within a live performance setting. This sheds light on techniques underlying, and potentially overlooked, in contemporary illusory practices modifying perceptions of reality through the related terms that developed over the century, including ‘self-hypnosis,’ ‘creative work,’ ‘consensual hallucination,’ and ‘metaxis’. The paper speculates that the prerequisite for immersive technologies to function is the concretization of the virtual in the participant’s body achieved through complicity, suspension of disbelief, and absorption. This line of inquiry begins to connect with Karen Barad’s agential realism through mattering, specifically with the computational and virtual, which seem not to matter and are too often overlooked as immaterial. It proceeds through three sections exploring the purported modifiers of reality (especially X-Reality, Extended Reality, and Mixed Reality), how performance brings the virtual to matter, and testing these ideas through a case study, the immersive VR/MR/XR artwork Child of Now staged in Melbourne in 2022.

Experienced as an immersive tactile audio-visual installation, Child of Now invites [one visitor at a time] to enter the Aboriginal concept of the ‘Everywhen,’ a place where all time is present, to observe the last 10,000 years of life on the Birrarung river [in Naarm, Melbourne] and acknowledge the resilience of First Nations peoples who survived climate emergencies and settler invasion. The experience continues by inviting visitors to imagine all the children being born in the present moment, now. It then accelerates time to the year in the future that the Child of Now is the visitor’s age. In this moment the artwork asks the visitor to imagine themselves as, and to become, the Child of Now in the future. It creates a portrait of their performance as audio and ‘digital hologram’ (volumetric video) recordings. Each holographic portrait of the visitor as the Child of Now is replayed in the final section of the experience: a VR archive set beneath the river where all the Children of Now are located in age order in the stream of time.

-Prix Ars Electronica, S+T+ARTS Prize (Citation2023)

Child of Now (R. Walton and Coleman Citation2022), is a project I created in collaboration with writer and activist Claire G. Coleman (Noongar), and a team of artists, computer scientists, producers, and XR studio Phoria. The project hybridized computational technologies, performance, sound, scenography, projection, animation, head-mounted displays, interaction, movement, voice, and storytelling to create an intimate experience of becoming aware of oneself as present within a long now of the Everywhen.Footnote1 The description of Child of Now quoted above demonstrates how tricky summarizing projects that combine media, environments, interactive participation, and narrative can be. Here, I offer a maker’s perspective on the Child of Now project, working at the convergence of arts practice and history, technology research and XR industry, and philosophies of virtuality. This proceeds through an illustrated chronology of the visitor’s movement through Child of Now using photography and script fragments and is followed by a discussion of virtual theatre, virtual art, and illusory media technologies that manipulate perception. I will not elaborate on our aspirations for the project to ‘foster embodied experiences of indigenized, equitable and sustainable societies, to explore how the future might feel’ which we have written about elsewhere (see Walton and Coleman Citation2023, 20), or make claims for the experience of the work, which is better addressed by audiences, who I prefer to term ‘visitors.’ My aim is to clarify the terms and concepts at play in the unruly ever-evolving field of creative practices imbricated with emerging technology and, more significantly, to better appreciate the visitor’s role in completing the work through their participation and as they become entangled with it, materializing the virtual within their bodies.

Playwright Antonin Artaud coined the term “virtual reality” in his 1938Footnote2 discussion of “alchemical theatre” highlighting theatre’s ability to transform everyday people and things into apparitions of virtual worlds, a “mirage” making tangible to the senses “what might be called philosophical states of matter” (Citation1958, 49). In echo of Artaud’s alchemical theatre, performance technology theorist Sita Popat notes that “theatre has always been a space of virtuality. The action on the stage exists as neither what it is actually nor what it is pretending to be; instead, it bridges the actual and the imaginary to create a virtual world in which performers and viewers are complicit” (Popat Citation2016, 357). This long association with the virtual may, in part, account for why many theatre makers have been drawn to virtual reality (VR) practices and the use of head-mounted displays (HMDs).

The first wave of creative practice with HMD VR in the 1990s led performance theorist Jon McKenzie to observe that VR ‘embodies the fluctuation of two performance paradigms by immersing human performance within technological performance’ (McKenzie Citation1994, 11). The VR systems McKenzie encountered in 1994 often lagged human perception, making the computing machine’s performance of producing the virtual world palpable to the person’s body interacting with it. The computer’s timing was off, people could feel it, and this impacted complicity. As computing performance has increased, the palpability of the work machines undertake has decreased, but as any user exasperated by lag will note, lapses in performance remain all too tangible. The extreme smallness and speed of the inner workings of computers means that their actions are entirely intangible to the unaided human sensorium when they are ‘performing well.’ We perceive a secondary, deliberate performance when the machine stages an output at a scale our senses can register, such as a sound or on-screen image. This feature of computers separating concern of their workings from you, the user, has led to a common belief that the performances they undertake on our behalf are immaterial and of a different plane of reality to our own. Simultaneously, computing has also come to monopolize the concept of the virtual, which has prompted a proliferation of ‘realities’ that might more accurately be called ‘virtualities’.

This proliferation is evident in the naming convention that emerged from VR to include other modifications of R, such as AR and XR, which will be discussed shortly. These technologies remain associated with the superimposition of virtual representations created by computers onto vision and can trace their prehistory to the invention of the stereoscope. However, as feminist theorist and physicist Karen Barad suggests, ‘to embrace representationalism and its geometry or geometrical optics of externality is not merely to make a justifiable approximation that can be fixed by adding further factors or perturbations at some later stage, but rather to start with the wrong optics, the wrong ground state, the wrong set of epistemological and ontological assumptions’ (Barad Citation2007, 381). In response, I propose to return to McKenzie’s observation of VR connecting computing machines and humans through performance to consider how this starting point might offer an alternative set of epistemological and ontological assumptions. The resurgence of VR technologies in this century emerged contemporaneously with wider tinkering and proliferation of ‘realities’ through other individuating computational technologies, most obviously from the fruitful outworkings of the ubiquitous computing apparatus ‘invisible interwoven’ (see Weiser Citation1991) into the fabric of reality through ‘smart’ consumer technologies, most notably the smartphone. This elaborated into a culture of ‘surveillance capitalism’ (Zuboff Citation2019), finding profit in the purchase of attention and provocation on social media and the propagation of alternative ‘realities’ that have directly impacted human society. See, for instance, UK and US Government responses to misinformation in the Brexit and 2016 US Presidential elections.Footnote3 The crisis of reality proliferation is widespread and rooted in the efficacy of machine performance. Therefore, the great challenge is finding ways to address the single reality we share and the virtualities we are complicit in perpetuating through our performances.

To this end, this essay begins to connect Barad’s concept of agential realism, of mattering, with the computational and virtual, which seem not to matter and are too often overlooked as ‘immaterial’. It builds on New Media Dramaturgies by Eckersall, Grehan, and Scheer (Citation2017), and Chris Salter’s many contributions, notably Participation, Interaction, Atmosphere, Projection (Salter Citation2017). It interrogates the seeming oxymoron of virtual reality and the idea of Extended Reality (XR) – extending into what? – and X-Reality (another XR) – more realities? It turns now to Child of Now as a case study, which is then contextualized in sections that explore modifications of reality, how performance brings the virtual to matter, and culminates in synthesis and reimaging of Child of Now as a virtual work.

Entering the everywhen – Child of Now

The following chronology draws together script fragments and production stills from Child of Now, staged at Arts Centre Melbourne in early 2022. It evokes a visitor’s journey through the work’s labyrinthine scenographic environment of corridors and small rooms, established as the ‘Everywhen’, an anglicized term for the Aboriginal Australian place where all time is present (Stanner Citation2009, 53). The focus here is on three rooms of the Everywhen labyrinth to illustrate how they concretize the work’s virtual elements through the visitor’s presence, participation, and complicity.

The character ‘I-ME’ (‘pronounced “time” without the “t”’) is the polyphonic voice that greets the visitor, engages them in conversation and guides them through the labyrinth of actual and virtual spaces. I-ME is a single character that speaks as a chorus of voices in different tones, timbres, and opinions provided by previous visitors, and led by female and male Aboriginal Australian voices. I-ME helps the visitor transition from preoccupation with their everyday world into increased awareness of their movement, thoughts, and voice within the Everywhen. I-ME’s voices move through the labyrinth and across media with the visitor, initially emanating from speakers surrounding the visitor on the riverbank (), into the screen-based animation in Room A (), into an intimate dialogue with the visitor via a tablet screen in Room B (), then into headphones of a HMD VR experience in Room C (). I-ME prompts the visitor to move, speak, and perform when required. Data generated by the visitor also moves across media as they move through the labyrinth: the year of their birth dynamically alters the dates mentioned by I-ME, the holograms the visitor records in Room A dynamically populate the virtual river environment in Room C, the audio recordings the visitor makes in Room B are also re-encountered in Room C.

Figure 1. The prologue room, a riverbank created with living plants, is the threshold to the Everywhen. I-ME’s voices are heard from speakers surrounding the visitor and hidden in the riverbank. I-ME says, “Life is a tidal river. Welcome, child, to the edge of the Everywhen, a place where all time is present. I am I-ME, your guide. Thousands of children are born in this moment. Each gasping for their first breath. You are one of them. Take a breath. I am archiving the days of your life, one child, one visitor like you, at a time.”Footnote4

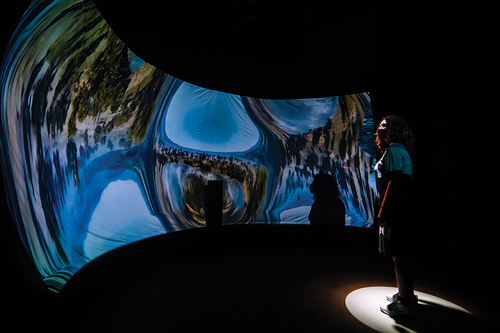

Figure 2. I-ME guides the visitor to the next room with a large curved screen, and says ‘Child of Now lives on the Birrarung, the river of mists that has sustained and been sustained by the Wurundjeri and Boonwurrung people for so long it may as well be forever. Ten thousand years ago the river ran through a fertile plain to the sea.’ on screen, the 8-minute animation of 10,000 years of life on Birrarung river begins with the flooding of Naarm (Port Phillip Bay, Melbourne).

Figure 3. The animation depicts the actual location on the Birrarung where the visitor is co-located, but is shot from a giant’s perspective looking over the riverscape. I-ME says, ‘The world changes whether we like it or not. We make the best decisions we can. We grow. We change. Together.’ the animation speeds forward in time, pausing for six moments: flood, equilibrium, cultural burning (controlled bushfire), settler invasion, the visitor’s present, and a final moment in the future when the child born today is the visitor’s age.

Figure 4. A participant moves their body to create a holographic portrait of the decision they make as the Child of Now. I-ME says, ‘The plains are flooding with salt water, becoming a mighty bay. Change can come dangerously quickly and life must find a way to adapt. Time to act. You must choose. Perform the gesture to make a decision’.

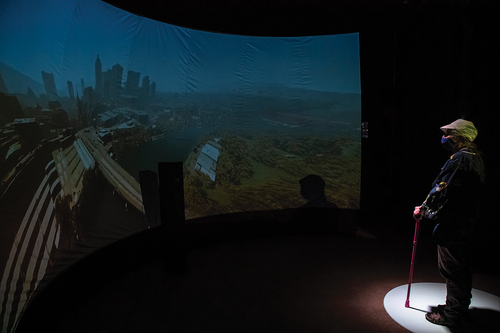

Figure 5. Arriving in the present moment, looking over the current Birrarung River and City of Melbourne from the perspective of a giant stood where the participant is now, on Southbank looking north. ‘All across this land the next Children of Now are being born. Here in your present now. Listen to their first breaths’.

Figure 6. I-ME says, ‘Do you embrace/comfort/lookout for/protect/defend these children, despite not knowing how? Perform the gesture to make a decision.’ the visitor is introduced to gestures associated with possible decisions to take on behalf of the child of now. They decide with their body when they perform the action. Their movement is captured as a volumetric video (virtual hologram) portrait, processed, and replayed in VR a few minutes later in Room C.

Figure 7. A still from the on-screen animation depicting merging visions of two futures for the Birrarung river and Melbourne. I-ME says, ‘If you knew you were living in the last days of the human story, what would you do? How would you act? To save the Child of Now, face the world we are making. Hold both of these visions in your heart. Take a deep breath’.

Figure 8. ‘Psst. Over here. Follow my voice.’ I-ME guides the visitor to a calm room for speaking as the Child of Now. I-ME’s voices say, ‘The year is [current year + visitor’s age]. You are the Child of Now age [visitor’s age]. Feels strange/weird/obvious until you … remember we are in the Everywhen.’ (Note: variables in square brackets are replaced by words, e.g. 2044, age 42). I-ME asks a series of 30 questions and prompts for the visitor to respond to with short (6–10 seconds) voice recordings. When they are ready to answer, the visitor presses a button to start their recording. I-ME’s prompts include: Who knew life would be so … When and where did you last swim in a river? How can we face up to the reality that we are making our world unliveable? The world really changed when … I have only survived by… if I could send a message back to [current year], I’d say ….

![Figure 8. ‘Psst. Over here. Follow my voice.’ I-ME guides the visitor to a calm room for speaking as the Child of Now. I-ME’s voices say, ‘The year is [current year + visitor’s age]. You are the Child of Now age [visitor’s age]. Feels strange/weird/obvious until you … remember we are in the Everywhen.’ (Note: variables in square brackets are replaced by words, e.g. 2044, age 42). I-ME asks a series of 30 questions and prompts for the visitor to respond to with short (6–10 seconds) voice recordings. When they are ready to answer, the visitor presses a button to start their recording. I-ME’s prompts include: Who knew life would be so … When and where did you last swim in a river? How can we face up to the reality that we are making our world unliveable? The world really changed when … I have only survived by… if I could send a message back to [current year], I’d say ….](/cms/asset/7c40c370-f11b-4c5b-950d-81c0e30a5cdc/ccon_a_2377288_f0008_oc.jpg)

Figure 9. I-ME’s voices say, ‘We share this beautiful/sexy/saggy/fat/thin/gorgeous/aging/young/weak/strong body. Whatever souls are made of ours are in this together. Me too/mine/mine too/ours/we’re connected/me/all of us/together/whether we like it or not/but we are different/similar but not the same/definitely not the same/completely different’.

Figure 10. I-ME’s voices say: ‘Psst. Over here. Come to the river, child. Where the stories of the people who lived a moment as the Child of Now are kept. Take a seat.’ the visitor sits in a boat and wears a HMD to experience the Child of Now archive in VR. The archive is represented by a river that contains 1000s of moments from the Child of Now’s life recorded by previous visitors arranged in age order from youngest to oldest. The boat submerges and travels along the riverbed. I-ME says, ‘At the river’s source, the child is just a baby, moments old, but will age like we all do, as life flows into the future. Let’s go a little faster, we have a long life to lead. Hold on!’.

Figure 11. VR still encountering a digital hologram beneath the river. The boat comes to a stop three times allowing the visitor to ‘Wake the memories by disturbing the riverbed.’ the first memory is close to the river’s source: a previous participant aged ten. Her virtual hologram and audio play when the visitor moves their hands to disturb the silt. The holograms and audio made by the visitor emerge further down the river. ‘You chose. You spoke. Actions make waves. Words ripple forever. Every breath you take matters.’ the final stop ‘is 2122. The child is almost 100. This river is ready to join the sea. Help it. Use your hands to dissolve the memory.’ the visitor’s gestures dissolve the hologram and the boat surfaces. The final image is the giant Child of Now overlooking the river. The giant’s body ages between the ten-year-old’s hologram, the visitor’s hologram, and the elder’s hologram then fades into the mist. The visitor removes the HMD and exits the boat. I-ME prepares them to return to their everyday life and bids them farewell. The visitor exits the Everywhen.

The following images and captions move chronologically through Child of Now. Each visitor enters alone and spends about seven minutes in each room in dialogue with I-ME’s voices.

Room A

Room B

Room C

Virtual art and virtual theatre

The question of where Child of Now might fit in the landscape of arts practice interests me insofar as it helps me engage in dialogue with the work of other practitioners. It is also useful to appreciate which combinations of technologies, approaches, subjects, and practices represent a contribution to the field, are ultimately achievable, and potentially fundable. However, I, like I suspect many others coming from experimental theatre and performance practice, can feel like an interloper in media art, which Oliver Grau termed ‘the new art of illusion’ (Citation2003, 9). His field-defining work Virtual Art: From Illusion To Immersion focused less on virtuality as an ‘anthropological constant’ which he traces to back to early European cave paintings, but on the more recent history of ‘fresco rooms, the panorama, circular cinema, and computer art in the CAVE: media that are the means whereby the eye is addressed with a totality of images’ and other ‘immersive image spaces’ (Grau Citation2003, 6). Grau’s aim not ‘to equate historic spaces of illusion with contemporary phenomena of virtual reality in order to construct a historical legitimation’ is useful because it is, he notes, citing Theodor Adorno, the ‘differences’ from older artworks ‘that should be elicited’ (Grau Citation2003, 9). While the combination of illusory technologies, narrative and participatory approaches of Child of Now are novel by nature of their idiosyncrasy, the work’s most significant ‘difference’ may be the time-play mobilized by the invitation to enter the Aboriginal concept of the Everywhen to contemplate oneself as plural within a collective, aeon-spanning, virtual being. Asking the visitor to imagine themselves as the child born today in the year in the future when they are the visitor’s age, and to record bodily gestures and spoken answers to specific questions as them, are the specific ‘differences’ of the project I will reflect on through the rest of this essay.

Gabriella Giannachi’s book Virtual Theatre (Giannachi Citation2004), published the year after Grau’s Virtual Art appeared in English, addresses many of the same phenomena as Grau, including virtual reality, from a theatre paradigm. Giannachi traces remediation through Marshall McLuhan (Citation1964) and Bolter and Richard (Citation2000), omitted from Grau’s tome, to arrive at a ‘virtual theatre’ that ‘constructs itself through the interaction between the viewer and the work of art which allows the viewer to be present in both the real and the virtual environment’ (Giannachi Citation2004, 11). Evoking the possibility of multiple modes of presence invites the plurality mobilized by the hybrid Everywhen environments where, ‘by interfering with the viewer’s sense of presence and imagination, it can, at least for a moment, remove them from the world they are in and allow them access to a different universe, one where a person could become another’ (Giannachi Citation2004, 158–9). However, in the case of Child of Now, it is not another universe that is sought, but a deeper connection to Boonwurung and Wurundjeri Country where the work occurs, and a greater appreciation of the ancient and future places of the river, to be present in the Everywhen. Likewise, it is not the work’s aspiration to transform the visitor into another person, but for them to come to a different awareness of themselves in relation to others who are, as I-ME says, ‘all in this together, though not one and the same.’ In both cases, the strategy of this virtual theatre is to deploy illusory techniques to dispel some of the illusions of settler-colonialism that curtail possible perceptions of place, time, and our responsibilities to the environment.

From Grau and Giannachi’s early millennium perspectives of virtual creative arts practices, I turn to the parallel development of ‘reality’ modifying techno-science devices that have emerged over the last decade during the second wave of VR. Arts practice engaging with the virtual is embroiled in the language of this emerging industry.

Modifications of R: V/A/M/X

Virtual Reality (VR) and its descendants, Augmented Reality (AR), Extended Reality (XR) and sometimes Mixed Reality (MR), constitute an area of computer science research, a burgeoning industry, and a series of technologies often associated with head-mounted displays (HMDs) that impose digital virtual representations on the sensorium through combinations of sound, light, and haptic vibration. The field is often discussed in technological disciplines through the ‘Reality-Virtuality Continuum’ proposed by Milgram et al. (Citation1995) that stretches from experiences of reality unmediated by digital virtual elements on the left of the continuum to experiences of digital virtuality that occlude aspects of ‘the real world’ on the right. AR appears around the middle, deploying digital virtual objects to occlude or annotate parts of the actual environment surrounding the user. In this context, the term Virtual Reality might contain the continuum: from virtual to real, or virtual made reality. However, VR is usually positioned as the rightmost pole of the continuum: virtual experiences where digital representations entirely manipulate the sensorium – a situation where the virtual replaces reality. Therefore, VR is considered less an oxymoron combining both ends of the continuum and more an aspiration to concretize the virtual by convincing the sensorium that its computationally staged representations constitute actual, tangible reality. Convincing the head, especially the eyes and ears, with the occasional addition of the hands, has taken the work of countless computer scientists and commercial technology developers. Incredibly challenging is the tuning of the machines producing the virtual to align with the body’s capacity to sense space as it moves. Despite the varieties of names, all the modifications of R relate to digital virtuality, V, and yet the ‘opposite of the virtual’, as Rob Shields points out, is not the real, but ‘the concrete’ (Citation2005, 22). The virtual is real and akin to Marcel Proust’s observation of the virtual nature of memory in Time Regained (1927): ‘real without being actual, ideal without being abstract’ (Cited in Deleuze and Patton Citation2010, 208; Shields Citation2005, 25).

Proust’s observation was taken as a starting point by both Bergson and, later, Deleuze in their work on virtuality: the relationship between the actual, concrete present, and dreams, memories, ideals, and other virtual aspects of life. The thread of virtuality in philosophy extended into this millennium with Brian Massumi’s development of affect (Citation2021), and Shield’s broad history and analysis of The Virtual (Shields Citation2005). While contemporaneous with the development of commercial VR systems in the 1990s and again in the 2010s, the virtualities of philosophy did not meaningfully penetrate computer science or industry. They had little impact on, for example, the development of terms for the invented technologies. This has led to a rift between the digital virtual and virtualities already a part of life, and the continued use of the term reality, R, in naming conventions, when a focus on virtual, V, and its concretization is more apt for these technologies. The Rs in question attempt to concretize (stage for the human sensorium) digital virtual environments. While concerns for names may not seem important, switching V for R and the overuse of R points to confusion and anxieties surrounding these technologies. Three myths are perpetuated by this naming convention modifying the trailing R. First, the virtual is not real, and virtuality is not part of reality, whereas the virtual exists. Second, the digital virtual has no precedent and is separate from the other virtualities experienced in life, whereas they exist with dreams, ideals, memories, imagination, and media. Third, virtual representations, worlds and environments are immaterial, whereas machines and bodies produce them. A solution to the proliferation of Rs emerged from the industry in a further modification: XR.

Rauschnabel et al.’s (Citation2022) interviews with VR/AR/XR industry professionals working at the nexus of industry and creative practice revealed that the profession, also frustrated by shifting technical terms, prefers ‘X-Reality’ over ‘Extended Reality.’ In this case, ‘X implies an unknown variable’ for technologies perceived to ‘generate or modify reality’ (Rauschnabel et al. Citation2022). While introducing X may curtail acronym proliferation, the inverse may be true for the unknown and questionable ‘realities’ yet to be ‘generated or modified’. The industry’s redefinition of XR does not address basic assumptions mobilized by both interpretations: Extended Reality, what or whose reality is extended, and into what? X-Reality, are there unknown realities and how many are there? Temporarily suspending these concerns and accepting that the ‘realities’ in question refer to encounters with virtuality allows exploration of XR’s benefits as an organizing principle in practice.

Creating Child of Now with Australian XR studio Phoria introduced me to the strategic importance of the X-Reality definition in industry. The open placeholder of XR allows for initial discussions about the goals and aspirations of a project before ‘locking in’ on how to achieve it with specific software and systems. This is particularly useful for immersive and transmedia works that might consider the routes into the experience via a series of thresholds and environments that surround what might otherwise be seen as the ‘central’ offering of the work, for example, a VR application, discussion, or media interaction. XR need not include HMDs. XR can begin to address virtualities within reality, journeys across media, and the distribution of work across an environment. Such a broad approach also offers entry points to artists and professionals from various creative disciplines, including film, performing arts (theatre, dance, music, puppetry, production), games, media and visual arts. Exploring an emerging and convergent field such as XR requires a softening of the disciplinary borders of existing practice. It is common for no two XR works to use the same constellation of technologies to achieve their goals, and XR’s soft borders mean that a creative team often arrive at a novel hybrid of forms inflected by their aspirations, disciplinary backgrounds, and ideals. In this sense, XR itself is virtual, guided by the meeting ideals of the teams and disciplines that seek to concretize it into a specific experience by deploying a range of interconnected technologies, techniques, and tricks of various trades.

This broad definition of XR is reminiscent of what Benford and Giannachi refer to as ‘mixed reality performances, a term intended to express both their mixing of the real and virtual as well as their combination of live performance and interactivity’ (Citation2011, 1). Initially developed in collaboration with interactive art group Blast Theory, Benford and Giannachi explain that ‘the foundation of this theory is that we can express how artists design, and participants experience, mixed reality performance in terms of multiple interleaved trajectories through complex hybrid structures of space, time, interfaces, and roles that establish new configurations of real and virtual, local and global, fact and fiction, personal and collective’ (Citation2011, 1). MR offers an expansive framework for describing events that attempt to reflect the complexity of contemporary life with ubiquitous computing, offering broader insight than XR, which remains closely, but not exclusively, focused on HMDs and the occlusion of ‘reality’ in the virtuality continuum. However, Benford and Giannachi’s account of MR perpetuates the trope common to all the modifications of R, that digital virtuality, produced by computation, is from a different reality, seemingly immaterial: another plane of existence. Nevertheless, incorporating liveness through performance and interaction and non-digital virtualities such as fiction brings a range of dimensions that outstretch HMD-inflected modifications of R.

The combination of elements mobilized in Benford and Giannachi’s MR performances echo in art practice what Barad describes as ‘intra-action’ to address ‘the mutual constitution of entangled agencies. That is, in contrast to the usual “interaction”, which assumes that there are separate individual agencies that precede their interaction, the notion of intra-action recognizes that distinct agencies do not precede, but rather emerge through, their intra-action’ (Barad Citation2007, 33). This thought extends to reshape the idea of pre-existing ‘realities’ ‘mixing’ through a MR performance, and instead offers a way to consider the inverse: that, in contrast to the usual shorthand of ‘multiple realities,’ which assumes there are separate individual realities that precede interaction (virtual worlds, computational media, stories, memories), the notion of intra-action recognizes that distinct realities do not precede, but rather emerge through intra-action. ‘Reality is composed not of things-in-themselves, or of things-behind-phenomena, but of things-in-phenomena’ (Barad Citation2007, 205). The ideal and the actual, the virtual and concrete, produce reality in their intra-action. The challenge is reconciling the virtual with materiality to collapse the idea that there are several seemingly separate realities and not one. The question is, and always was, how does the virtual come to matter?

(How) performance matters

Artaud’s first use of the term virtual reality sets in motion a too-convenient combination that rolls two seemingly irreconcilable worlds into one: the material physical reality of the universe and a sublime world of abstract ideals that exist close to but in a separate reality. Interest in multiple parallel realities and opportunities for staging their meeting litter the history of Western thought and folklore. The idea persists in contemporary uses of VR, life with digital technologies, and, more broadly, in many philosophical and everyday belief systems. Returning to theatre reveals how, in each performance, staging renders the virtual tangible to the senses. But how might theatre’s understanding of virtual reality apply when the perception-machining technology is wearable and, in the case of head-mounted displays, stages a performance in extreme proximity to the face?

Writer Stanley Weinbaum’s fantastical short story Pygmalion’s Spectacles (Weinbaum Citation1938)Footnote5 describes a gas-mask-like device able to stage an absorbing immersive interactive experience. The story is worth lingering on as it prefigures later twentieth-century HMD experiments designed to stage what we now call virtual reality. Emerging contemporaneously with Artaud’s writing, albeit across the Atlantic, Weinbaum shared an interest in the alchemical properties of illusions. His fictional ‘spectacles’ combined ‘liquid with light-sensitive chromates’, chemicals and electricity to play ‘a movie that gives one sight and sound … taste, smell, even touch,’ creating an effect that enables the belief that ‘you are in the story, you speak to the shadows, and the shadows reply, and instead of being on a screen, the story is all about you, and you are in it’ (Weinbaum Citation1938). In the story, protagonist Dan Burke is initially suspicious of Professor Albert Ludwig’s invention. Still, he is converted during a transformative five-hour experience wearing the ‘spectacles’ in an empty hotel room. Burke visits a virtual Edenic forest where he forgets ‘the paradoxes of illusion’ and falls in love with the environment and Galatea, a character he meets and believes is real. The story ends with Burke’s disillusioned re-entry into his everyday life ‘shaken, sick, exhausted, with a bitter sense of bereavement,’ chastising himself for falling ‘in love with a girl who had never lived, in a fantastic Utopia that was literally nowhere!’ (Weinbaum Citation1938). Professor Ludwig reveals to Dan that the illusion was achieved through clever manipulation of everyday materials, ‘the trees were club-mosses enlarged by a lens,’ ‘the fruits were rubber.’ If the experience felt real, it was only because Burke cooperated: ‘it takes self-hypnosis’ (Weinbaum Citation1938).

Weinbaum does not use the word ‘virtual’, but his evocation of utopia and its definition as a virtuous place that cannot exist reveals an understanding akin to virtuality. The story presciently describes many aspects of HMD usage that have now become common, such as the incongruent relationship between participant’s body and their impressions of the virtual place: ‘Unbelieving, still gripping the arms of that unseen chair, he was staring at a forest.’ Indeed, the choice of the forest setting for the experience imagined in 1938 – ‘But what a forest! Incredible, unearthly, beautiful!’ – resonates with experimental practice almost a century later, especially in the work of Australian experimental media and XR producers Phoria, Yandell Walton, Lynette Wallworth, Ben Joseph Andrews and Emma Roberts, who have all made work about ancient rainforests such as the Daintree. Why forests are attractive to creators of virtual environments is a matter for other studies. However, for now I posit that the creators of virtual worlds find in forests teeming with non-human life enough stark contrast to the built environment as to appear from a world other than Earth. As ideal virtual worlds, forests ‘become “virtuous”, utopian’ (Shields Citation2005, 4), echoing a familiar trope of wilderness contrasting civilization: alien and unknowable to the ‘civilised’ and domesticated city-dweller, yet possible in this world. Forests may seem the opposite of the sophisticated, ordered, synthetic machines that stage virtual forests for the sensorium.

Professor Ludwig’s attempts to prove the efficacy of his invention by persuading people to sit with the experience for a few minutes is reminiscent of the claims made this century for VR as the ‘ultimate empathy machine’ able to motivate pro-social behaviour and change minds in moments – claims which persist despite being widely rebuked (see Sora-Domenjó (Citation2022) for an overview). Climate and refugee rights activists regularly use emotive VR experiences to influence decision-makers at global events like the World Economic Forum (Wilson and Scully Citation2022). Further, Professor Ludwig’s bitter disposition is reminiscent of anyone who has attempted to promote VR experiences at tradeshows: ‘Fools! I bring it here to sell … and what do they say? “It isn’t clear. Only one person can use it at a time. It’s too expensive.” Fools! Fools!’ (Weinbaum Citation1938). However, Weinbaum’s final thought, that technology requires the participant’s self-hypnosis to function, is worth lingering on as it relates Artaud’s vision for the alchemical transformation of everyday materials (moss and rubber) into virtual objects (trees and fruit) to the participant’s complicity in the creation of the experience. The participant is required to materialize the virtual through metaxis.

Shields notes that ‘metaxis, or the ability to imaginatively close up the gap between fiction and reality and between the virtual and the actual has a long history, and may be found in social rituals and in the historical record’ (Shields Citation2005, 43). Indeed, creating the circumstances that enable audiences to enter and become absorbed in the ritual of dramatic theatre performances remains of keen interest to the art form and is addressed in Aristotle’s Poetics. The necessity of audiences to suspend disbelief and accept that the event they are participating in is not-not-real permits metaxy, which theatre practitioner and activist Augusto Boal described as ‘the state of belonging completely and simultaneously to two different autonomous worlds’ (Citation1995, 43) when theorizing his approach to non-digital, interactive theatre. To enter this state requires a kind of work or creative activity from audiences who constitute and permit a virtual world to be concretized through their complicity. German theatre theorist Max Herrmann, who lived, like Weinbaum and Artaud, in the 1930s, describes the audience’s work in theatre as a ‘secret empathy, a shadowy reconstruction of the actors’ performance, which is experienced not so much visually as through physical sensations. It is a secret urge to perform the same actions, to reproduce the same tone of voice in the throat’ (Weinbaum Citation1938 quote cited in Fischer-Lichte Citation2008). Without a character (the virtual being concretized by the actor and audience), one can, through a similar empathy, project into a virtual place via a stage set or moss trees and rubber fruit. ‘Cyberspace,’ as novelist William Gibson coined it, is achieved through a similar ‘consensual hallucination’ (Gibson Citation1984, 67).

Sita Popat refines this line of argument for bodies within mixed reality performance environments by proposing that ‘potentials embedded in the virtual become real and thus the conceptual site is concretized in the visitor’s experience of moving within it’ (Popat Citation2015, 169). She shifts the locus of attention from obvious screen and environmental interfaces, to consider how ‘the nature of physical and virtual elements not only enables the body to be present but it actually demands that presence, since the body is the experiential interface through which virtual and physical become “real”’ (Popat Citation2015, 176). The arrival of the visitor’s body into the Child of Now environment, for example, is the inciting incident that enables the work to take place. I-ME’s disembodied voices land within the visitor, inviting them to think more of themselves as they move and speak and stretch themselves across the Everywhen environment that includes its virtual dimensions above and below the river, of being the person in the boat witnessing their body in the digital hologram awoken from the riverbed by their hands waving in thin air and virtual water. Popat suggests ‘that bodies within these contexts may be experienced simultaneously as absent and present, together and separate’ and that such a blurring ‘confounds cognitive separation between the physical and virtual’ (Citation2016, 360–1). Quietly answering I-ME’s questions within Room B and the playful framework of imagining oneself as someone living in the future sending messages back to your current self might allow ‘us to experience interactions with the virtual world as not-being-not-real and thus to do the undoable, rehearse the unrehearsable’ (Popat Citation2016, 372) like empathizing with future generations, or even the seemingly simple act of imagining a future, which many visitors found challenging in a time of climate catastrophe.

The ability to ‘reconstruct’ the virtual through physical sensation, to concretize it through one’s body in performance, extends to non-human life, systems and abstract concepts. For example, Knorr Cetina’s (Citation2009) sociological analysis of stock market traders’ use of computer screens that functioned as ‘scopes’ to the market itself allowed her to reflect on how their ‘bodies and the screen world melt together’ in ‘an apparently total immersion in the actions in which they are participating.’ She goes on to note that ‘while scope and body remain materially distinct, the body has been trained to “see through” the scope’ and ‘feel’ the market’s ‘flickering, temporal, dissociated sensations’ (Knorr Cetina Citation2009, 72). The traders were able to enter the world of the market and feel its sensations through rows of numbers, highlighting that response-presence, being in sync, and sharing time with the virtual may be more critical for entering it than the fidelity or photorealism of visual representation. The body concretizes the virtual. People collaborate with the staging they perceive to apprehend and manifest the virtual in the same moment. The process goes by many names: self-hypnosis, consensual hallucination, metaxy, complicity, suspension of disbelief, absorption, flow, blurred bodies, and alchemical transformation. Each variation enables the reverse transfiguration of the ideal to the actual, and the virtual to the concrete. While not always conscious, the concretization of the virtual occurs within and around the body because we must achieve it for ourselves. The virtual can only materialize if the audience is willing to perform it.

Metaxis in X-Reality – imagining Child of Now as a virtual work

Just as the importance of the body as a performance rather than a thing can hardly be overemphasized, so should we resist the familiar conception of spacetime as a preexisting Euclidean container (or even a non-Euclidean manifold) that presents separately constituted bodies with a place to be or a space through which to travel

Child of Now invites visitors to explore the concept of the Everywhen and through it reimagine their relationship to their body and the collective body of society, their present and the collective time of generations. To draw on Shield’s framework, the project seeks to move visitors bodily, imaginatively, and politically, between the real and possible, the ideal and actual. The functioning of the project depends on the visitor’s willingness to become complicit and enter a state of metaxis within the limonoid space and time of the work. The world of Child of Now overlaps momentarily with the visitor’s life. For the duration of each encounter, they are indistinguishable. The work asks visitors to concretize virtual places, people, and times, and then to speak as someone else in the future from their situation in the present, as though in a long present, the Everywhen. The visitor becomes the child of now in the past and future when they do the creative work of empathizing through aspects of embodiment that we share with others who also sense, move, feel, and draw the virtual into being. The child of now is each visitor’s body when their ages align. As a lifetime of moments, it contains many individuals, and their collective life course is apprehended in the virtual river that flows from youngest to oldest, containing traces of shared gestures and answers to questions of concern in voices of all types. It combines many virtualities: digital, like the river encountered in VR in a HMD; computational, like the virtual hologram point clouds; abstract, like the concept ‘life is a tidal river’ and the idea of the river running through our veins; probable, like the futures foretold by actual visitors; pasts, like the collective memory of the flooding of Naarm held by the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri for 10,000 years and graciously shared with the project and its visitors; and present, like the thoughts and dreams emerging within the visitor’s body as they move and speak in response to stimuli. Child of Now, like other virtual works concretized by their participants, is, as Barad notes, ‘intra-actively produced,’ made in practice, in action, as the product of the visitor’s engagement with the environment, stimuli, technology, spaces and times of the work bound-up in the broader unfolding of the world (Citation2007, 383). Each iteration is a unique instantiation, a one-off concretization, of the work, never the same as the last, but the same enough to contribute new dimensions of corporeality, voice, and perspective to the gathering portrait of the collective child of now. At the end of each visitor’s journey, the concretization they alchemically manifested dissolves into a virtual past, with traces left in the digital archive, the visitor’s body, and on the surfaces of the installation’s materials touched. Such Everywhen thinking of the cycle of complicit participation enables appreciation that the repetitive, citational performance practice at the heart of virtuality is a phenomenon of temporary concretization. Furthermore, ‘as a result of the iterative nature of intra-active practices that constitute phenomena, the “past” and the “future” are iteratively reconfigured and enfolded through one another: phenomena cannot be located in space and time; rather, phenomena are material entanglements that “extend” across different spaces and times’ (Barad Citation2007, 383). Reclaiming the virtual from its recent, overly close association with the computational might allow virtualities of all kinds, including past and present, to be apprehended by the concretizing processes of intra-action at the heart of all modifications of R.

Conclusion

This essay was written in a time of proliferating realities produced by the individuating performances of machine computing, a time when grounding in a shared, co-constituted reality seemed a too virtuous utopia ever to exist, though it was needed like never before. It began to connect Barad’s concept of mattering in agential realism with the computational and virtual, that which seems not to matter. It traced a history of VR to identify the underlying prerequisite for the technology’s functioning, perhaps the underlying technique of all live arts, as the complicit auto-concretization of the virtual in the body: an intra-active process that produces reality in a blurred body. It moved through the Child of Now project as a case study to consider how elaborate digital virtualities can interplay with equally intricate non-digital virtualities to address important questions about time, life courses, liveness and participation in change. A short essay can only ever be partial in its response to a large and complex artwork that is made and remade for one visitor at a time, so the process of concretization of the virtual through performance was highlighted noting that the prerequisite for immersive technologies to function is the concretization of the virtual in the participant’s body achieved through complicity, suspension of disbelief, and absorption. Child of Now’s attempt to shift the visitor’s perspective of their place in the Everywhen is reminiscent of Barad’s observation that ‘embodiment is a matter not of being specifically situated in the world, but rather of being of the world in its dynamic specificity’ (Barad Citation2007, 377). Ancient concepts like the Everywhen highlight that even seemingly new technologies, like XR, are staged in this single reality. They are met in ‘phenomena’ that produce ‘specific material configurations of the world … In other words, humans (like other parts of nature) are of the world, not in the world, and surely not outside of it looking in’ (Barad Citation2007, 206). Despite the claims for the excessive proliferation of realities, none are new, and all are involutions exploring the potential of this singular reality, where, as Popat notes, ‘the blurring of physical and virtual is already happening in our bodies’ (Popat Citation2016, 371). If we are, as Barad suggests, ‘responsible not only for the knowledge that we seek but, in part, for what exists’ (Barad Citation2007, 207) then we might more carefully consider what aspects of the virtual to manifest, what to enact, and choose to see in the cycles of performance, which are ever remade, the possibility to concretize higher ideals.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the Child of Now project for kindly providing all production photographs taken by Gregory Lorenzutti.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. For further information and a full list of collaborators and funders visit: www.robertwalton.net/project/child-of-now/.

2. Note that this text was not translated and published in English until 1958.

3. See The UK Information Commissioner (Citation2019); The House of Commons Culture Media and Sport Select Committee (Citation2019); Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III (Citation2019)

4. Note that all quotations from the script are provided courtesy of the artists.

5. The whole short story is available on Project Gutenberg, but without page numbers: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22893/22893-h/22893-h.htm.

References

- Artaud, Antonin. 1958. The Theatre and Its Double. Edited by Mary Caroline. Richards: Grove Press.

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Benford, Steve, and Gabriella Giannachi. 2011. Performing Mixed Reality. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Boal, Augusto. 1995. The Rainbow of Desire: The Boal Method of Theatre and Therapy. London & New York: Routledge.

- Bolter, J. David, and A. Grusin. Richard. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 2010. Difference and Repetition. Edited by Paul Patton. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Eckersall, Peter, Helena Grehan, and Edward Scheer. 2017. New Media Dramaturgy: Performance. Media and New-Materialism: Springer.

- Fischer-Lichte, Erika. 2008. The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

- Giannachi, Gabriella. 2004. Virtual Theatres: An Introduction. London & New York: Routledge.

- Gibson, Willam. 1984. Neuromancer. London: Orion.

- Grau, Oliver. 2003. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Edited by Gloria Custance. MIT press.

- The House of Commons Culture Media and Sport Select Committee. 2019. “Russian Influence in Political Campaigns.” The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Last Modified 29 July 2018. Accessed October 24. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcumeds/363/36308.htm#_idTextAnchor033.

- Knorr Cetina, Karin. 2009. “The Synthetic Situation: Interactionism for a Global World.” Symbolic Interaction 32 (1): 61–87.

- Massumi, Brian. 2021. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- McKenzie, Jon. 1994. “Virtual Reality: Performance, Immersion, and the Thaw.” TDR: The Drama Review 38 (4). https://doi.org/10.2307/1146426.

- McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: New American Library.

- Milgram, Paul, Haruo Takemura, Akira Utsumi, and Fumio Kishino. 1995. Augmented Reality: A Class of Displays on the Reality-Virtuality Continuum. Photonics for Industrial Applications. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.197321.

- Popat, Sita. 2015. “Placing the Body in Mixed Reality.” In Moving Sites: Investigating Site-Specific Dance Performance, edited by Victoria Hunter, 162–177. London: Routledge.

- Popat, Sita. 2016. “Missing in Action: Embodied Experience and Virtual Reality.” Theatre Journal 68 (3): 357–378.

- Rauschnabel, Philipp A., Reto Felix, Chris Hinsch, Hamza Shahab, and Florian Alt. 2022. “What Is XR? Towards a Framework for Augmented and Virtual Reality.” Computers in Human Behavior 133:107289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107289.

- S+T+ARTS Prize. 2023. “Child of Now.” Ars Electronica Linz GmbH. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://starts-prize.aec.at/en/child-of-now/.

- Salter, Chris. 2017. “Participation, Interaction, Atmosphere, Projection.” In The Routledge Companion to Scenography, edited by Arnold Aronson, 164. London & New York: Routledge.

- Shields, Rob. 2005. The Virtual. London & New York: Routledge.

- Sora-Domenjó, Carles. 2022. “Disrupting the “Empathy machine”: The Power and Perils of Virtual Reality in Addressing Social Issues.” Frontiers in Psychology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.814565.

- Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III. 2019. “The Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election.” U.S. Department of Justice. Accessed October 24. https://www.justice.gov/storage/report.pdf.

- Stanner, W. E. H. 2009. The Dreaming and Other Essays. Melbourne: Black Inc. Agenda.

- The UK Information Commissioner. 2019. “Investigation into the Use of Data Analytics in Political Campaigns: Investigation Update 11 July 2018.” Information Commissioner’s Office. Accessed October 24. https://ico.org.uk/media/action-weve-taken/2259371/investigation-into-data-analytics-for-political-purposes-update.pdf.

- Walton, Robert, and Claire G Coleman. 2022. “Child of Now.” Melbourne: Arts Centre Melbourne. Accessed May 17, 2024. www.robertwalton.net/project/child-of-now/.

- Walton, Robert E., and Claire G. Coleman. 2023. “Beyond the Dystopia-In-Progress: Rehearsing an Indigenized Future ‘Australia’ Through Public Art.” In Dystopian and Utopian Impulses in Art Making : The World We Want, edited by McQuilten Grace and Palmer Daniel, 11–28. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Weinbaum, Stanley G. 1938. “Pygmalion’s Spectacles.” Wonder Stories, Project Gutenberg. June. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22893/22893-h/22893-h.htm.

- Weiser, Mark. 1991. “The Computer for the 21st Century.” Scientific American 3 (3). https://doi.org/10.1145/329124.329126.

- Wilson, R. Scott, and Katherine Scully. 2022. “Virtual Reality and Activism.” Anthropology News. Accessed February 10. https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/virtual-reality-and-activism/.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs.