ABSTRACT

As in many other countries, individuals with disabilities in the Netherlands have difficulties in establishing sustainable careers. In the Netherlands, Royal Philips offers a work-experience program with the possibility to follow vocational education. Based on national register data, a control group was constructed that includes individuals with a disability with a similar labour market history as participants of the company-based program before entry but who were involved in public rehabilitation. This study compared the labour market outcomes up to ten years later (i.e., the level of employment and employment on a competitive salary) of individuals with a disability that participated in the program (N = 552) with those of a matched control group engaged in public rehabilitation. The long-term impact of participation in the programme on the level of employment appears to be firmer for individuals with a physical disability (N = 283) than for those with a cognitive disability (N = 269). Contrariwise, a more substantial effect was found on employment on a competitive salary for individuals with a cognitive disability than for those with a physical disability. Following vocational education, while gaining work experience, explains the long-term impact found for former participants of this company-based program partially.

Introduction

Traditionally, the Netherlands lags far behind other Western and Northern European countries in terms of the percentage of labour market participation of individuals with a disability (Eurostat, Citation2014), notwithstanding its high overall rates of labour participation. Most recent numbers of the year 2017 show an unemployment rate among individuals with disabilities of 9.6%, while this was only 4.5% for those without disabilities (Statistics Netherlands, Citation2019). Moreover, the priority of Dutch employers in hiring individuals with a disability is relatively low. Only 17% of Dutch employers have employees from this vulnerable, whereas a third of the Dutch employers feel responsible for hiring individuals with disabilities, and another third do not see the inclusion of this group of workers as their responsibility (Versantvoort & Van Echtelt, Citation2016).

Generally, the activation approach of public rehabilitation enforces job-search efforts by offering unemployed individuals with disabilities job-search assistance (see Hanif, Peters, McDougall, & Lindsay, Citation2017), but also through impending sanctions in the form of reduced benefits or the temporary withdrawal thereof. Experts assess the personal preferences and the capacities of individuals with disabilities to determine suitable jobs and consider the necessity of training (see Hoekstra, Sanders, Van den Heuvel, Post, & Groothoff, Citation2004). During the period studied, persons with (early-age) labour disabilities had the right to support in work, including reintegration, training and an on-trial period for placement with an employer, provided by either the Employee Insurance Agency (Uitvoeringsinstituut Werknemersverzekeringen [UWV] in Dutch) or the local municipality. Other groups of individuals with disabilities had more limited support with some possibilities to engage in additional employment or specific training offered by the municipalities. Eventually, unemployed individuals with disabilities mostly remain at home and submit applications with limited employment support.

The primary concern with this approach remains that, because of the limited skill formation in this public approach because of budgetary reasons,, workers might get steered into lower-quality and subsidised jobs, which offer little chance for this group of workers to progress in their careers. Take, for instance, possibilities for further training, promotion, or a permanent employment contract. In practice, employers typically offer limited career growth opportunities to employees who may leave the firm soon because of their disabilities. The benefits of such investments are unlikely to be reaped for an extended period (Fouarge, De Grip, Smits, & De Vries, Citation2012). Consequently, employers may use the provided subsidies to acquire a flexible pool of employees to fill up vacancy gaps and to adjust to workload fluctuations (Kalleberg, Reskin, & Hudson, Citation2000) without a strong commitment to integrating individuals with a disability to the fullest (Bredgaard, Citation2018; Jaenichen & Stephan, Citation2011). A more inclusive and supply-side approach might be needed to integrate individuals with disabilities better so that workers themselves can take matters into their own hands without being dependent too much on the generosity of subsidies and boost their human capital (Shima, Zólyomi, & Zaidi, Citation2008).

Since 1983, the Dutch multinational company Royal Philips – known for its household appliances, lighting products, and healthcare products – employs, among other vulnerable groups, individuals with disabilities for a period of one to two years within their plants and offices, accompanied with on-the-job training and obligatory classes on career development, focusing on job search, networking, and job-application skills. The Philips Employment Scheme (Philips Werkgelegenheidsplan in Dutch; hereinafter referred to its Dutch abbreviation: the WGP) invests in the human capital of its participants. As agreed with labour unions, the Dutch government does not subsidise the WGP and Philips must invest in participants’ skills but without the obligation or intention to recruit them eventually. Thus, there is no intention for a long-term working relationship with Philips; instead, the WGP is designed to place their participants into jobs in the external labour market after completion of the program. Philips allows participants to leave with only one-week notice to reduce the lock-in effects that are associated with such programs (Hujer, Thomsen, & Zeiss, Citation2006; Van Ours, Citation2004). Most important, however, is that the WGP offers the opportunity to follow vocational education up to upper secondary education (i.e., ISCED2011-Level 3), which is essential in the Dutch labour market. Participants might be enrolled in this vocational track either if they do not possess such a qualification yet or if they are unable to continue their current profession precisely because of their disability and need retraining in another field of study to safeguard their careers (see Supplemental Material A.2).

The current study observes the long-term effect of this work-experience program for individuals with a disability compared with that of being engaged in public rehabilitation to support individuals with disabilities back into the labour market. The question addressed in this study is: to what extent do individuals with a disability participating in this company-based work-experience program fare better in their careers (i.e., level of employment and employment on a competitive salary) than similar individuals with disabilities engaged in public rehabilitation? If any such effect can be observed, to what extent can the provision of vocational education during participation in this program account for this long-term effect?

The innovative approach of this study lies in the combination of national register data with Philips’ personnel registration system. In doing so, the impact of this company-based program can be compared to that of public rehabilitation up to ten years later by constructing a matched control group based on a substantial number of pre-treatment characteristics and labour market history (e.g., reducing heterogeneity). Many studies that conducted such a difference-in-difference estimation are not able to observe career outcomes over such a long time horizon (Cook, Burke-Miller, & Roessel, Citation2016; Gerards, Muysken, & Welters, Citation2014; Leinonen et al., Citation2019). Earlier studies on vocational rehabilitation focus on the short-term exit rates to employment (De Boer et al., Citation2018; Lammerts, Van Dongen, Schaafsma, Van Mechelen, & Anema, Citation2017), for instance, finding a job above the statutory minimum wage (Dutta, Gervey, Chan, Chou, & Ditchman, Citation2008; Rast, Roux, & Shattuck, Citation2019). However, little is known about the exact quality of the ensuing employment in both the short and long run (e.g., employment on a competitive salary). This study observes the annual months in employment over a ten-year period but also uses an employment measure the wages of individuals with disabilities (of our matched sample) with that of individuals without disabilities based on wage information of the entire Dutch labour force, providing more insight into the inequalities compared with regular workers. Furthermore, the role of following vocational education is addressed, while many (public) rehabilitation initiatives often offer less in-depth forms of treatment.

Theory and Hypotheses

Reducing the Potential Loss in Productivity

During the hiring process, employers refer to past work experience and educational qualifications as signals for assessing the potential productivity of their potential employees. These signals listed in résumés help to solve the problem of imperfect information of employers in assessing the potential workers (as a screening device). Educational qualifications are clear signals of acquired skills, but also the labour market history of workers as an additional, and perhaps the most crucial selection criterion as it shows how these acquired skills have been applied in the workplace (Pissarides, Citation1992; Vishwanath, Citation1989) shows how the acquired skills have been applied in the workplace. Reference can be made to stigmatisation, originating from the signalling theory (Spence, Citation1973), suggesting that differences in labour market outcomes arise from the uncertainty about workers’ productive capabilities based on their stock of human capital (Becker, Citation1964) leading to this stigmatisation. The stock of human capital of workers indicates employers of the hiring costs involved, needed to be invested in on-the-job training to allow these potential employees to perform adequately in the workplace (DiPrete, De Graaf, Luijkx, Tahlin, & Blossfeld, Citation1997; Gangl, Citation2004). What is even more worrying, however, is that having worked in either lower-quality or subsidised jobs, which is not uncommon for individuals with disabilities, may also worsen the stigma attached to these workers, who will, perhaps, more than before be labelled as problem cases (Bonoli & Mouline, Citation2012; Marx, Citation2001).

A disability, or having either partially or fully recovered from a disability, brings more limited labour market chances compared with regular employees, by this we mean without disabilities (Brouwers, Citation2020; Burke et al., Citation2013; Cheatham & Randolph, Citation2020). Explanations for these lower prospects partly point to the general assumption of employers towards individuals with disabilities of being less productive (Unger, Citation2002; Lalvani, Citation2015; Scheid, Citation2005). This postulation depends, of course, on workers’ educational qualifications, past work experience, the degree of incapacity for working, and the kind of disability in relation to the available positions. Nonetheless, almost every worker with a disability needs some accommodation of the workplace and extra supervision to perform adequately in his or her job, leading to extra costs for employers.

As noted earlier, individuals with a disability may have a weak labour market history because of their incapability for working (i.e., aggravated disadvantage), but also due to the relatively generous Dutch disability scheme in the past (e.g., re-assessed individuals with a disability, see Supplemental Material A.1) that may have induced them to withdraw themselves from the labour market for a considerable period. Furthermore, workers’ age, ethnic minority group, and parenthood in combination with gender play their part in the process as well (Cheatham & Randolph, Citation2020; Gracia, Vázquez-Quesada, & Van de Werfhorst, Citation2016; Hakim, Citation2002; Karren & Sherman, Citation2012; Mincer, Citation1974; Mooi-Reci & Ganzeboom, Citation2015).

A Stepping-Stone Towards More Sustainable Careers

A work-experience program, such as the WGP, attempts to reduce the risks aversion of prospective employers that are associated with the higher expected hiring and ongoing costs of hiring individuals with a disability. Philips aims to increase participants’ productivity levels by building up relevant work experience and training and thus decreasing the initial hiring costs for prospective employers. While WGP participants search for jobs, they presumably also benefit from the positive signalling effect of putting the brand of Philips on their résumés serving as a kind of screening device. The work experience gained is expected to be more valued by prospective employers, given that WGP participation looks like a regular job (Gerfin, Lechner, & Steiger, Citation2005; Sianesi, Citation2008). Because Philips has a good reputation in the Dutch labor market, the firm is likely to be associated with higher performance and learning standards compared with those of jobs in either the collective sector or at the small tomedium firms in the region where the post-intervention employment most likely would be gained. Thus, WGP participants are expected to stand out from other available candidates in application rounds, giving participants that little extra push in reducing the stigma that rests upon this group of workers.

Earlier studies on different vocational rehabilitation services for individuals with either physical or cognitive disabilities show that participants benefit from on-the-job training, e.g., job-specific skills provided by employers (e.g., job-specific skills provided by employers (Dutta et al., Citation2008; Lammerts et al., Citation2017). However, to establish more sustainable careers, the investment in human capital must not only compensate employers for the loss in productivity but should also help these individuals with disabilities further along the career path. Furthermore, the WGP also provides career-development courses (e.g., job-readiness training). These courses are expected to confirm excellent performance on the job and to raise confidence in one’s capabilities (Kohlrausch & Rasner, Citation2014; Strandh & Nordlund, Citation2008), which in turn increases personal autonomy, trust and intrinsic motivation for paid work, and thus, are likely to result in increased job-search efforts (Fugate, Kinicki, & Ashforth, Citation2004).Footnote1 This more active approach is in contrast with the less-intensive approach of public services.

Hypothesis 1

Individuals with a disability participating in the WGP have better labour market outcomes in the end than other individuals with a disability in public rehabilitation.

Vocational training and other forms of formal training contribute to the employment success of individuals with disabilities (Dutta et al., Citation2008; Heloísa et al., Citation2016; Thoresen, Cocks, & Parsons, Citation2019). A degree gives access to recognised occupations that require occupation-specific skills, which in general are better paid and more secure in terms of the type of contract (Wolbers, Citation2003). As earlier noted, at Philips, individuals with a disability are enrolled in this vocational track either if they do not possess this essential basic qualification (ISCED2011-Level ≥ 3), but also if they are unable to further their professional careers because of their disability and need to retrain themselves. Following vocational education in itself, including the opportunity to get re-educated in another field of study, has a positive impact on workers’ level of employment but not necessarily on the quality of jobs at their disposal. Given that the WGP involves such a robust vocational component in their rehabilitation services in combination with work experience, in comparison with the public approach, it is expected that the long-term effect of participating in the WGP can partially be explained by following vocational education, i.e., a mediating effect..

Hypothesis 2

The provision of vocational education partially explains the long-term effect of the WGP compared to the lower probability of following vocational education in the public approach.

Materials and Methods

Data and Matched Sample

Statistics Netherlands registers all Dutch inhabitants that are registered at the Employee Insurance Agency or the municipality and have claimed (youth) disability benefits in the period 1999–2016. The group of WGP participants consists of a mix of people with either physical or cognitive disabilities, but also varies along the degree of incapability for work (e.g., heterogeneity). Both the Employee Insurance Agency and the local municipality take care of the pre-selection of potential participants at Philips. Still, the WGP administrators have the final say in the selection (e.g., potential selection effect, for instance, on their innate abilities).

Philips collected the social security numbers of former participants – those who entered the WGP between 1999–2014 – and sent these along with their inflow and outflow dates to Statistics Netherlands, who, in their turn, identified these people in the national register data. In doing so, the personal characteristics and circumstances of former WGP participants one month before the start of the WGP, could be observed (see ) and a control group based on these characteristics was constructed, but that was subject to public rehabilitation (e.g., quasi-experimental design). The matching procedure attempts to establish a parallel trend assumption among the former WGP participants (i.e., the treatment group) and other similar individuals with disabilities engaged in public rehabilitation (i.e., the control group). The long-term effect of WGP participation, over that of public rehabilitation, is observed for up to ten years in the post-intervention period by comparing the labour market outcomes of WGP participants with this control group.

Table 1. Participants characteristics (concise) at the start of the WGP (t = 0).

Propensity Score Matching

The WGP participants are matched to other individuals with disabilities that can thus be considered similar except for entitlement to public rehabilitation instead of WGP participation. As such, a matched sample was created to perform our difference-in-difference analysis on, using the psmatch2 module in Stata 16 with the option Mahalanobis (see Leuven & Sianesi, Citation2003). The matching procedure was divided into the years 1999–2014 because of the considerable size of the different datasets that were needed to be merged at forehand.

The following pre-treatment covariates were included in our matching procedure: the doctors’ diagnosis and the assessment of the labour market expert that determined the degree of incapacity for work (in %) based on a Dutch equivalent (Classificaties voor Arbo en SV in Dutch) of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). To control for unobserved personal factors (i.e., personality traits, IQ,and work ethic), the procedure matched on a two-year labour market history, including the number of months in employment, the number of unemployment spells, and the number of employers over the past two years. Besides, information about individuals’ last job was also included– if any in the past two years – including the previous job’s daily wage, and whether the previous job was subsidised by the Dutch government (see for the relevance of this Caliendo, Mahlstedt, & Mitnik, Citation2017). Otherwise, the long-term effect of WGP participation would probably be overestimated given that WGP participants are at least able to perform labour. The group of potential control units is much larger and more diverse, including many more individuals that are incapable of performing labour than in the group selected by Philips. The matching procedure reduces both the heterogeneity and the extent of bias in estimations.

Concerning the personal characteristics, measured one month before WGP participation, such as workers’ age, ethnic minority group, educational attainment, the field of study, position in the household interacted with gender, and the part of the country where workers are living were included in the matching procedure as well. Furthermore, the workers’ first occurrence in the data was included in the forthcoming years to prevent attrition bias and to secure a representative control group for which their labour market outcomes can be compared throughout the entire observation period. See Supplemental Material A.3 for more information on the matching procedure and the required balance checks.

Dependent Variables

The first dependent variable denotes the level of employment, measured by the number of months in any form of employment within the ten years, including subsidised jobs and regardless of any periods of unemployment interspersed, varying from 0 to 120 months (divided by 120 months). The second dependent variable denotes the level of employment on a competitive salary that matches workers’ characteristics, such as educational attainment and age.Footnote2 In order to see whether the wage matches that of individuals without disabilities, the observed wage is compared to an expected wage regardless of the disability (Sattinger, Citation1993). The expected wage levels are predicted through Heckman’s two-step selection models on the entire Dutch labour force between 1999-2016 (NMean = 15,228,338). For each month in the year, the individuals’ main job was determined based on the highest wage, followed by job length and the type of contract. If the log observed wage in a particular month was higher or equal to the expected wage – with a 5% margin – it is assumed that the job matches workers’ skill level

Empirical Models

Difference-in-difference models are performed on the impact of WGP participation for individuals with a disability on their labour outcomes in the post-intervention period up to ten years compared with that of the control group (see Lechner, Citation2010). Fixed-effects linear panel regression models are performed to control for the remaining unobserved heterogeneity, for which could not be matched on, estimating the average within-person change in employment outcomes, using Stata 16 with the command: xtreg, fe (see Allison, Citation2009). The marginal effects of the first model that result from the first model are predicted over the post-intervention years while keeping all other covariates in the model constant (using the command margins).

In contrast to OLS regression, without adjusting for confounding on post-treatment variables (see Table A.6.2 in the Supplemental Material A.6), fixed-effects modelling allows us to net out the mediating effect, considering that no unobserved variables besides the post-intervention period and time-invariant fixed effects influence the effect of following education on the dependent variables (see Supplemental Material A.4). This study performs separate models for individuals with a cognitive disability (N = 536) and with a physical disability (N = 564). Following vocational education is operationalised as follows: for each individual in the matched sample, it was observed whether they started a vocational education program in the year of matching – thus WGP entry and benefit claiming – that was different from either their prior educational level or field of study. As such, for people with a physical disability, 152 former WGP participants started vocational education versus 70 workers in the control group. For people with a cognitive disability, 118 former WGP participants started vocational education versus 75 workers in the control group.

To avoid any confounding effect of over-time trends, analyses control for several factors that are measured at the time of each intervention entry and completion, namely: age(-squared) to measure time-varying human capital (Mincer, Citation1974) in which the quadratic term allows for a non-linear effect on the level of employment and employment on a competitive salary. Further controls include the regional unemployment rates at NUTS-2 level to control for cyclical effects; workers’ household position including the youngest child’s age interacted with a dummy variable for females to control for the effect that parenthood may have on stigmatisation but also individuals’ own decisions to perform labour (see Hakim, Citation2002) and the residential area at NUTS-3 level to control for regional labour demand. Furthermore, a control for changes in the degree of incapability for working (in %) is included.

Results

In the standard model, the post-intervention effect is identified by comparing the labour market outcomes among workers, either participating in the WGP or public rehabilitation. A binary independent variable is used to indicate whether a given individual participated in the WGP – with the control group as reference category – which is interacted with another binary independent variable that indicates the post-intervention period – with the pre-intervention period as the reference category. This interaction term shows the additional effect of WGP participation over that of public rehabilitation. discusses the difference-in-difference estimations on both dependent variables.

Table 2. Unstandardised coefficients on the level of employment and employment on a competitive salary, from fixed-effects panel regression models.

The Long-term Effects of Participating in the WGP

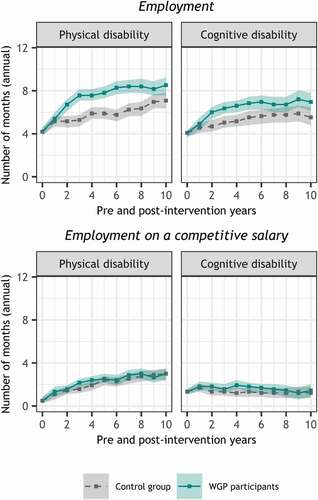

shows the long-term effect on the level of employment for individuals with a physical or cognitive disability, either participating in the WGP or being engaged in public rehabilitation in the post-intervention period. Columns (1) and (3) show a strong significant negative trend in the post-intervention period for individuals with a physical disability in general (b = −0.10, p < 0.001) on the level of employment but an insignificant effect for those with a cognitive disability in general. Individuals with a physical disability who participated in the WGP, however, have an additional long-term effect – which is over that of the main effect of the post-intervention period – of 16.6% on their level of employment (b = 0.17, p < 0.001). In comparison, the long-term effect of WGP participation for individuals with a cognitive disability is 10.5% (b = 0.11, p < 0.05). Columns (5) and (7) show a small significant long-term effect of 6.7% for individuals with a cognitive disability (b = 0.07, p < 0.01) but an insignificant effect for those with a physical disability on the level of employment on a competitive salary. Results, in general, indicate that the level of employment is improved among former participants in the company scheme, confirming hypothesis 1 for individuals with a cognitive disability but only partially for individuals with a cognitive disability. shows the marginal effects on the level of employment (upper) and employment on a competitive salary (lower) of this standard model predicted over the post-intervention years (see Table A.6.3 in Supplementary Material A.6.). Most of the treatment effect can be found in the first years after WGP completion, presumably showing the positive signalling effect of having worked at Philips.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of employment (upper) and employment on a competitive salary (lower) in annual months for individuals with a physical (left) and cognitive disability (right), pre and post-intervention period Note(s). Shaded bars show the 95%-confidence intervals, based on the first model. Graphs are made by replacing the post-intervention dummy by ten post-intervention year dummy variables (see Table A.6.3).

In the mediator model, the mediating effect of vocational education is expected to (partially) explain the differences in the long-term labour market outcomes between former WGP participants and those engaged in public rehabilitation. It is expected that the estimates of the post-intervention period would change in comparison with the first model, but the interaction term with WGP participants is expected to weaken more considerably. As such, the impact of vocational education during the WGP is implicitly captured compared with the lack of such opportunity in public services. Columns (2), (4), (6) and (8) add the effect of the following education to the previous models, showing positive long-term effects for all types of individuals with disabilities and on both dependent variables, except for individuals with a cognitive disability (respectively, b = 0.10, p < 0.05; b = −0.04, p > 0.10; b = 0.06, p < 0.05; b = −0.04, p > 0.10).

As expected, the interaction terms between the post-intervention period and WGP participants have weakened, but also the main effects of the post-intervention period representing the control group show this reduction. The long-term effect of participating in the WGP can thus partially be explained by the program's strong vocational component for participants with a physical disability, confirming hypothesis 2 for individuals with physical disabilities. It is interesting to observe that this partial effect on the level of employment is almost identical for individuals with a physical or cognitive disability. Concerning the level of employment on a competitive salary, no significant long-term effect has been found for individuals with a cognitive disability who participated in the WGP. For those with a physical disability, contrariwise, such a long-term effect is found on the level of employment on a competitive salary, highlighting the key role of vocational education.

Discussion

The current study shows that the careers of individuals with a disability can be enhanced through participating in a company-based work-experience program instead of being engaged in public rehabilitation. The main limitation of this study is that the focus can only be on the available information in the register data. Philips did not collect any subjective information from its participants throughout the WGP period, even though the context of belonging to the regular labour market, rather than staying at home, is expected to evoke changes in participants’ mindset, professional networks, job-search behaviour, and learning experiences. These factors are presumed to be the underlying mechanisms of how human-capital investments create immediate and long-running additional effects over that of standard public rehabilitation. Moreover, it could be argued that participants’ innate work ethic positively affected their selection into the WGP (see Myers & Cox, Citation2020). The fixed-effects models, as well as the matching procedure control for this unobserved heterogeneity, inasmuch affecting the treated and non-treated units similarly. A combination of register and subjective data would have been of great value for policymakers nonetheless.

Future research might collect this subjective information over a more extended period to observe the extent to which such private initiatives foster participants’ self-esteem and well-being, underpinning the long-term success of the human capital investment (Rose, Citation2018). For individuals with a cognitive disability, the inclusion of the development in GAF scores (as included in the DSM-IV) on workers’ social, occupational, psychological functioning (e.g., symptom severity) may provide an answer for whom and why such workplace adjustments and human-capital investments enable participants to cope with external stimuli and to establish better relationships with their managers and co-workers. For instance, by comparing their scores with those of others engaged in public rehabilitation.

Conclusions and Implications

The investments in human capital support more sustainable careers among a hard-to-place group of vulnerable workers. Still, it needs to be noted that the extent to which long-term employment on a competitive salary can be established in such a company-based program is somewhat marginal (e.g., ceiling effect). Nonetheless, policymakers should not only focus on aligning individuals' skills with labour demand but also stress the importance and meaning of work for the daily life of individuals with a disability (Barnes & Mercer, Citation2005; Wehman et al., Citation2017).

Unlike public rehabilitation, the WGP combines multiple forms of training (i.e., on-the-job training and career-development courses) as well as the opportunity to follow vocational education fully paid for by Philips. Moreover, unemployment is one of the most stressful life events that increase the likelihood of reduced self-esteem and social isolation (Audhoe, Hoving, Sluiter, & Frings-Dresen, Citation2010; Hoving, Van Zwieten, Van der Meer, Sluiter, & Frings-Dresen, Citation2013; McKee-Ryan, Song, Wanberg, & Kinicki, Citation2005). Policymakers need to acknowledge that unemployed individuals in general, need more inclusive measures that prevent them from the adverse psychological effects of unemployment. As earlier stated, the level of employment on a competitive salary established by WGP participation is marginal.

Under the 2015 Participation Act (Participatiewet in Dutch) and the Work and Income according to Labour Capacity Act (Wet werk en inkomen naar arbeidsvermogen [WIA] in Dutch) the Dutch government aims to minimise the number of individuals with a disability working in (entirely) subsidised jobs but to raise their numbers working in regular jobs instead. Today in the Netherlands, every unemployed individual with a disability can get support from either the Employee Insurance Agency or the municipality to return to the labour market, i.e., an activation policy in combination with job coaches subsidised by the Dutch government, on-trial placements (e.g., additional-employment jobs), or start-up loans for self-employment. Still, there is no actual, substantive investment in human capital. The decentralisation of the provision of disability schemes to the municipalities in the Netherlands – except for the early-age disability scheme – has facilitated a positive shift nonetheless. From that point onwards, there seemed to be a paradigm shift towards more social investment policies that provide a different perspective on the labour market (re-)integration of vulnerable groups of workers. However, the problem that seems to occur in the Netherlands is that, under the Participation Act, the most vulnerable individuals with disabilities get hired because the government requires employers to do so. Consequently, those individuals with the highest capabilities for work find themselves unemployed, precisely because this group of workers was thought to be capable of sustaining their position on the labour market on their own.

Employers may benefit from offering such work-experience programs as well (see Lindsay, Cagliostro, Albarico, Mortaji, & Karon, Citation2018). They show their corporate social responsibility and improve their relationships with labour unions. The latter is of great importance in countries that have a culture of centralised, industry, or company-based wage bargaining. There is a scope for agreements with large companies, labour unions, and the government to design and run a tailor-made work-experience program like the WGP, pursuing sustainable careers for individuals with a disability, thereby driving back their numbers of benefit recipients. This study provides an argument for encouraging employers to take up their responsibilities to invest in work experience and for urging the Dutch government to increase the budget on formal training to let individuals with a disability better integrate into society and to have them build up a career in secure and sustainable employment as full part of the labour force.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Royal Philips, Frank Visser and Stefanie van der Ven, for their cooperation. It has been a privilege to work with such a partner and to conduct research on their long-standing work-experience program. The first author wants to thank prof. dr. Ton Wilthagen (co-author) and prof. dr. Ruud Muffels for their supervision and methodological knowledge throughout the entire PhD project. The authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on previous versions of this article as well as for their encouragement to us to carry on with this important stream of research.

Data availability statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available at Statistics Netherlands on request (and on payment) and under license for this study only. Access to the microdata is only granted to scientific researchers under strict privacy-securing conditions (see https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/our-services/customised-services-microdata/microdata-conducting-your-own-research). After ethic approval, we analysed the data through a remote-access facility that connects our computers to Statistics Netherlands’ protected ICT environment. Statistics Netherlands performs a check on the results to secure anonymity and privacy. Data belong to Statistics Netherlands, and for that reason, the data cannot be added in a (public) repository. Results must be published to ensure that there is no conflict of interest with third parties.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Please note that Royal Philips was aware that the outcomes of the present study must be published, following the guidelines of Statistics Netherlands, and agreed in advance to conduct a study on their program, regardless of the outcomes.

Notes

1. The development of soft skills is expected to be fruitful for individuals with a cognitive disability, e.g., people diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Participants might possess the hard skills required for jobs, but continuously experience difficulties in how to act during job interviews or have difficulties to work together with co-workers in the workplace. The WGP proved to be effective for the careers of those participants diagnosed with ASD (see Peijen & Bos, Citation2019).

2. The level of employment in unsubsidised labour is observed as well, but the long-term effect for WGP participants looks very similar to that of the level of employment (see Table A.6.1 in the Supplemental Material A.6).

References

- Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models (Vol. 160). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Audhoe, S. S., Hoving, J. L., Sluiter, J. K., & Frings-Dresen, M. H. W. (2010, March). Vocational interventions for unemployed: Effects on work participation and mental distress. A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20, 1-13. doi:10.1007/s10926-009-9223-y

- Barnes, C., & Mercer, G. (2005). Disability, work, and welfare: Challenging the social exclusion of disabled people. Work, Employment and Society, 19(3), 527-545. doi:10.1177/0950017005055669.

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with a special reference to education. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Bonoli, G., & Mouline, Q. U. (2012). The postindustrial employment problem and active labour market policy. 10th ESPAnet Annual Conference, Edinburgh, 6–8.

- Bredgaard, T. (2018). Employers and active labour market policies: Typologies and evidence. Social Policy and Society, 17(3), 365-377. doi:10.1017/S147474641700015X.

- Brouwers, E. P. (2020). Social stigma is an underestimated contributing factor to unemployment in people with mental illness or mental health issues: Position paper and future directions. BMC Psychology, 8, 36. doi:10.1186/s40359-020-00399-0

- Burke, J., Bezyak, J., Fraser, R. T., Pete, J., Ditchman, N., & Chan, F. (2013). Employers’ attitudes towards hiring and retaining people with disabilities: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 19(1), 21-38. doi:10.1017/jrc.2013.2

- Caliendo, M., Mahlstedt, R., & Mitnik, O. A. (2017). Unobservable, but unimportant? The relevance of usually unobserved variables for the evaluation of labor market policies. Labour Economics, 46, 14-25. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2017.02.001

- Cheatham, L. P., & Randolph, K. (2020). Education and employment transitions among young adults with disabilities: Comparisons by disability status, type and severity. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–24. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2020.1722073

- Cook, J. A., Burke-Miller, J. K., & Roessel, E. (2016). Long-term effects of evidence-based supported employment on earnings and on SSI and SSDI participation among individuals with psychiatric disabilities. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(10), 1007-1014. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15101359

- De Boer, A. G. E. M., Geuskens, G. A., Bültmann, U., Boot, C. R. L., Wind, H., Koppes, L. L. J., & Frings-Dresen, M. H. W. (2018). Employment status transitions in employees with and without chronic disease in the Netherlands. International Journal of Public Health, 63, 713-722. doi:10.1007/s00038-018-1120-8

- DiPrete, T. A., De Graaf, P. M., Luijkx, R., Tahlin, M., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (1997). Collectivist versus individualist mobility regimes? Structural change and job mobility in four countries. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 318-358. doi:10.1086/231210

- Dutta, A., Gervey, R., Chan, F., Chou, C.C., & Ditchman, N. (2008). Vocational rehabilitation services and employment outcomes for people with disabilities: A United States study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 18(4), 326-334. doi:10.1007/s10926-008-9154-z

- Eurostat. (2014). Disability statistics - labour market access. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/pdfscache/34420.pdf

- Fouarge, D., De Grip, A., Smits, W., & De Vries, R. (2012). Flexible contracts and human capital investments. De Economist, 160(2), 177-195. doi:10.1007/s10645-011-9179-0

- Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14-38. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005.

- Gangl, M. (2004). Welfare states and the scar effects of unemployment: A comparative analysis of the United States and West Germany. American Journal of Sociology, 109(6), 1319-1364. doi:10.1086/381902

- Gerards, R., Muysken, J., & Welters, R. (2014). Active labour market policy by a profit-maximizing firm. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 52(1), 136-157. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2012.00915.x

- Gerfin, M., Lechner, M., & Steiger, H. (2005). Does subsidised temporary employment get the unemployed back to work? An econometric analysis of two different schemes. Labour Economics, unger(6), 807-835. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2004.04.002.

- Gracia, P., Vázquez-Quesada, L., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2016). Ethnic penalties? The role of human capital and social origins in labour market outcomes of second-generation Moroccans and Turks in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(1), 69-87. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1085800.

- Hakim, C. (2002). Lifestyle preferences as determinants of women’s differentiated labor market careers. Work and Occupations, 29(4), 428-459. doi:10.1177/0730888402029004003.

- Hanif, S., Peters, H., McDougall, C., & Lindsay, S. (2017). A systematic review of vocational interventions for youth with physical disabilities. In B. Altman (Eds.) Factors in studying employment for persons with disability: How the picture can change (pp. 181–202). Binley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Heloísa, F., Santos, D., Gomes-Machado, M. L., Santos, F. H., Schoen, T., & Chiari, B. (2016). Effects of vocational training on a group of people with intellectual disabilities prospective memory and commission errors: The effect of cognitive load on non-performed PM tasks View project working memory processess and interactions view project effects of vocational training on a group of people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(1), 33-40. doi:10.1111/jppi.12144

- Hoekstra, E. J., Sanders, K., Van den Heuvel, W. J. A., Post, D., & Groothoff, J. W. (2004). Supported employment in the Netherlands for people with an intellectual disability, a psychiatric disability and a chronic disease. A comparative study. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 21(1), 39–48.

- Hoving, J. L., Van Zwieten, M. C. B., Van der Meer, M., Sluiter, J. K., & Frings-Dresen, M. H. W. (2013). Work participation and arthritis: A systematic overview of challenges, adaptations and opportunities for interventions. Rheumatology, 52(7), 1254-1264. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ket111

- Hujer, R., Thomsen, S. L., & Zeiss, C. (2006, June). The effects of vocational training programmes on the duration of unemployment in Eastern Germany. Allgemeines Statistisches Archiv, 90, 299-321. doi:10.1007/s10182-006-0235-z

- Jaenichen, U., & Stephan, G. (2011). The effectiveness of targeted wage subsidies for hard-to-place workers. Applied Economics, 43(10), 1209-1225. doi:10.1080/00036840802600426

- Kalleberg, A. L., Reskin, B. F., & Hudson, K. (2000). Bad jobs in America: Standard and nonstandard employment relations and job quality in the United States. American Sociological Review, 65(2), 256-278. doi:10.2307/2657440

- Karren, R., & Sherman, K. (2012). Layoffs and unemployment discrimination: A new stigma. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(8), 848–863.

- Kohlrausch, B., & Rasner, A. (2014). Workplace training in Germany and its impact on subjective job security: Short- or long-term returns? Journal of European Social Policy, 24(4), 337-350. doi:10.1177/0958928714538216

- Lalvani, P. (2015). Disability, stigma and otherness: Perspectives of parents and teachers. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 62(4), 379–393. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2015.1029877

- Lammerts, L., Van Dongen, J. M., Schaafsma, F. G., Van Mechelen, W., & Anema, J. R. (2017). A participatory supportive return to work program for workers without an employment contract, sick-listed due to a common mental disorder: An economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 17, 162. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4079-0

- Lechner, M. (2010, November 15). “The Estimation of Causal Effects by Difference-in-Difference Methods”, Foundations and Trends in Econometrics: Vol. 4: No. 3, 165-224. Boston, MA: Now Publishers Inc. doi:10.1561/0800000014

- Leinonen, T., Viikari-Juntura, E., Husgafvel-Pursiainen, K., Juvonen-Posti, P., Laaksonen, M., & Solovieva, S. (2019). The effectiveness of vocational rehabilitation on work participation: A propensity score matched analysis using nationwide register data. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 45(6), 651–660. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3823

- Leuven, E., & Sianesi, B. (2003). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Retrieved from https://sociorepec.org/publication.xml?h=repec:boc:bocode:s432001&l=en

- Lindsay, S., Cagliostro, E., Albarico, M., Mortaji, N., & Karon, L. (2018, December 1). A systematic review of the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 28, 634-655. doi:10.1007/s10926-018-9756-z

- Marx, I. (2001). Job subsidies and cuts in employers’ social security contributions: The verdict of empirical evaluation studies. International Labour Review, 140(1), doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2001.tb00213.x.

- McKee-Ryan, F., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53

- Mincer, J. (1974). Schooling, experience, and earnings. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Mooi-Reci, I., & Ganzeboom, H. B. (2015). Unemployment scarring by gender: Human capital depreciation or stigmatization? Longitudinal evidence from the Netherlands, 1980–2000. Social Science Research, 52, 642–658. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.10.00

- Myers, C., & Cox, C. (2020). Work motivation perceptions of students with intellectual disabilities before and after participation in a short‐term vocational rehabilitation summer programme: An exploratory study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. doi:10.1111/jar.12711

- Peijen, R., & Bos, M. C. M. (2019). Naar een succesvollere arbeidsintegratie van mensen met ASS: Meer (niet-gesubsidieerd) werk door het Philips Werkgelegenheidsplan. Wetenschappelijk Tijdschrift Autisme, 18(4). 2-18. Retrieved from http://wta.swptijdschriften.nl/Magazine/Article/3612

- Pissarides, C. (1992). Loss of skill during unemployment and the persistence of employment shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(4), 1371–1391. doi:10.2307/2118392

- Rast, J. E., Roux, A. M., & Shattuck, P. T. (2019). Use of vocational rehabilitation supports for postsecondary education among transition-age youth on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 2164–2173. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03972-8

- Rose, D. (2018). The impact of active labour market policies on the well-being of the unemployed. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(3) . doi:10.1177/0958928718792118

- Sattinger, M. (1993). Assignment models of the distribution of earnings. Journal of Economic Literature, 31(2), 831–880. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2728516

- Scheid, T. L. (2005). Stigma as a barrier to employment: Mental disability and the Americans with disabilities act. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 28(6), 670–690. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.04.003

- Shima, I., Zólyomi, E., & Zaidi, A. (2008). The labour market situation of people with disabilities in EU25. Policy Brief 2.1/2008. Vienna, AT: European Centre.

- Sianesi, B. (2008). Differential effects of active labour market programs for the unemployed. Labour Economics, 15(3), 392–421. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2007.04.004

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355-374. doi:10.2307/1882010

- Statistics Netherlands. (2019). Arbeidsdeelname; arbeidsgehandicapten 2015–2017. Retrieved from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83322NED/table?dl=A824

- Strandh, M., & Nordlund, M. (2008). Active labour market policy and unemployment scarring: A ten-year Swedish panel study. Journal of Social Policy, 37(3), 357–382. doi:10.1017/S0047279408001955

- Thoresen, S. H., Cocks, E., & Parsons, R. (2019). Three year longitudinal study of graduate employment outcomes for Australian apprentices and trainees with and without disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2019.1699648

- Unger, D. D. (2002). Employers’ Attitudes Toward Persons with Disabilities in the Workforce: Myths or Realities? Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(1), 2–10. doi:10.1177/108835760201700101

- Van Ours, J. C. (2004). The locking-in effect of subsidized jobs. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32(1), 37–55. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2003.10.002

- Versantvoort, M., & Van Echtelt, P. (2016). Beperkt in functie. The Hague, NL: The Netherlands Institute for Social Research.

- Vishwanath, T. (1989). Job search, stigma effect, and escape rate from unemployment. Journal of Labor Economics, 7(4), 487–502. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2535139

- Wehman, P., Schall, C. M., McDonough, J., Graham, C., Brooke, V., Riehle, J. E., … Avellone, L. (2017). Effects of an employer-based intervention on employment outcomes for youth with significant support needs due to autism. Autism, 21(3), 276–290. doi:10.1177/1362361316635826

- Wolbers, M. H. J. (2003). Job mismatches and their labour-market effects among school-leavers in Europe. European Sociological Review, 19(3), 249–266. doi:10.1093/esr/19.3.249