ABSTRACT

Since 2015, menstruation has become increasingly politicised on social media. This impetus has been driven by activists who strive to destigmatise menstruation and raise awareness of issues such as “period poverty.” As sociological studies demonstrate, menstrual stigma is rooted in ideologies that construct menstruating women as leaking, unhygienic and irrational. Such discourses are indicative of a societal imperative to ensure that menstrual blood remains concealed. By creating memes, social media users are increasing the visibility of menstruation in the public space. Drawing on concepts from critical menstruation studies and theories about humour and ideology, this article explores the discourses that inform menstrual memes. Using Nvivo, 220 memes posted on Instagram with the hashtag “#periodmemes” were coded and then analysed with MCDA. Although many of these memes perpetuate stigma, a significant number use humour to problematise harmful ideologies. This article argues that, despite appearing trivial, menstrual memes have the potential to normalise menstruation and advance the objectives of menstrual activism.

Introduction

In 2015, menstrual activism started to gain the attention of the mainstream media due to activists, such as Nikita Azad and Kiran Gandhi, publicly protesting menstrual stigma. Activists used tactics such as visibly bleeding in public spaces, posting photographs of menstrual blood on social media, and launching hashtag campaigns. Since then, menstruation has continued to take increasing space in both traditional and social media (Bobel and Fahs Citation2020). Traditionally, feminists have argued that menstruation is a taboo and stigmatised subject because societal discourses about menstruation are based on pejorative patriarchal attitudes that characterise menstruators as dirty, leaking, and hysterical (Ussher Citation2006). Thanks, however, to menstrual activism and new approaches in critical menstrual studies, we have over the last few years witnessed the emergence of new ideologies. These range from a discourse of realism, which encourages menstruators to speak honestly about their pain, to a discourse of period positivity, which urges menstruators to celebrate their menstrual cycle (McHugh Citation2020). Despite the fact that social media offers an indicator as to everyday societal perceptions of menstruation and is the main vehicle through which many menstrual activists promote their messages, few studies have paid attention to it. Memes, which are an aspect of everyday social media interaction, are profoundly influenced by sociocultural context and convey ideologies through their use of humour (De Cook Citation2018). Yet memes have been overlooked within critical menstrual studies. Using multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA), this article analyses the semiotic resources of 220 memes and seeks to unearth the ideologies that inform them. Drawing on critical menstruation studies and theories about humour and ideology, this study determines the extent to which the 220 memes perpetuate traditional ideas around menstruation. This could take place by reinforcing shame or could be countered by tapping into more recent activist discourses, celebrating menstruation, or raising awareness of the lived experiences of diverse menstruators.

Sociological studies about menstruation

Menstrual experience has received critical attention from feminist scholars since the 1970s. Second-wave feminists, such as Julia Kristeva (Citation1980) and Annie Leclerc (Citation1974), argued that menstrual discourses are rooted in patriarchal ideologies that engender women to view their own bodies in a negative light.Footnote1 Since the 1970s, scholars in the West have continued to argue that societal discourses about menstruation are grounded in sexism (Chrisler Citation2013). Ussher (Citation2006) argues that patriarchal ideologies position the female body as monstrous because menstrual blood is a signifier of a dangerous feminine excess. She explains that women are expected to keep this threatening body contained through adhering to rules of hygiene and ensuring that their menstrual blood remains undetectable. The author argues:

Central to this positioning of the female body as monstrous […] is ambivalence associated with the power and danger perceived to be inherent in woman’s fecund flesh, her seeping, leaking, bleeding womb standing as site of pollution and source of dread. (Ussher Citation2006, 1)

Scholarship frequently draws on Foucault’s work to explain this compulsion for menstruators to monitor their bodies (Ussher Citation2006). Foucault (Citation1975) argues that members of society are constantly policed as if they were prisoners in a panopticon in which the guard can see into each cell. The prisoners, who cannot see each other, feel constantly observed, and self-discipline accordingly. Wood refers to menstruators' vigilance over their bodies as “the menstrual concealment imperative” (Citation2020). This self-surveillance is not “freely chosen” but is grounded in societal discourses that stigmatise menstruators (Wood Citation2020, 320). This concealment imperative can negatively impact women’s self-esteem: in societies wherein the “idealised feminine” is slim and contained, menstruators can suffer from “self-objectification” (Fredrickson and Roberts Citation1997). This self-objectification is based on an internalised critical gaze that characterises menstruators as unruly and bloated, and thus in diametric opposition to the “idealised feminine” (Erchull Citation2013).

Both researchers and advocates are, however, divided on how to eradicate menstrual stigma. Normalisation is an ideology that is dominant in the menstrual activist community and many see social media as playing an instrumental role in encouraging people to talk unashamedly about this topic (Bobel and Fahs Citation2020). Sally King, who founded Menstrual Matters, explains normalisation as follows: “the key is that you want [menstruation] to be normalised. […] it’s just something that happens that’s fine” (King Citation2020a). “Period positivity” is another common discourse amongst advocates. For example, Chella Quint (creator of #periodpostive) and Molly Fenton (founder of “Love Your Period”) employ social media to encourage others to celebrate menstruation. However, some researchers have indicated that “period positive” discourses can silence menstruators with health conditions such as PMDD (Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder) or endometriosis. Przybylo and Fahs (Citation2020) believe a discourse of “menstrual crankiness” is a more effective way to challenge gendered inequalities and menstrual stigma. “Menstrual crankiness” both recognises, and approaches intersectionally, the pain menstruators endure and the difficulties they may face in accessing menstrual products or facilities. It is important to note that the aforementioned studies and examples of advocacy emanate from the West, and it is upon Western discourses that this article also focusses. Although it may seem to Western onlookers that countries such as the United Kingdom are leading the way, this viewpoint reflects a neocolonial ideology that effaces the successful grassroots menstrual activism that has been undertaken in African countries, such as Uganda, Kenya and Zimbabwe, since before 2015 (Irise International Citation2020).

Memes, humour and ideology

Academic studies of memes, because of their potential to shed light on prevalent societal ideologies and how these are articulated through popular culture, have proliferated in recent years (Wells Citation2018). In The Discursive Power of Memes, Wiggins (Citation2019, 1) asserts that memes “contain within them a semiotic meaning which is itself tethered to an ideological practice.” Kligler-Vilenchik and Thorson explain that “while often irreverent, memes can be seen as a way that people insert themselves into a public conversation and can be used as a tool for political meaning-making” (Citation2016, 1997). The intent of memes is largely humorous, but they can have many other functions, including advancing an argument, advising, and posing questions (Grundlingh Citation2018). Ferreira and Vasconcelos (Citation2019), who analyse anti-feminist memes that perpetuate misogynistic ideology through humour, illustrate that memes can maintain asymmetrical gendered power relations. In contrast, Gal et al. (Citation2016) emphasise the subversive potential of memes to challenge harmful ideologies and foster collective resistance.

Drawing on studies about humour, we can argue that the humour in memes has the potential to either reinforce or subvert social norms (Holmes Citation2000; Billig Citation2005). Holmes examines two types of humour. The first, “reinforcing humour,” maintains the status quo. The second, “contestive humour,” challenges the status quo and provides a socially acceptable manner through which to register a protest. Billig builds on Holmes’ paradigm and echoes Foucault’s ideas of self-discipline (Citation2005). He distinguishes between two types of humour:

Disciplinary humour mocks those who break social rules, and thus can be seen to aid the maintenance of those rules. Rebellious humour mocks the social rules, and, in its turn, can be seen to challenge, or rebel against, the rules. (Billig Citation2005, 180)

Methodology

Theoretical framework

This article’s theoretical framework shapes how the semiotic resources of the memes were identified and subsequently analysed. This framework combines sociological studies about menstruation, scholarship on humour, and Foucault’s theories of power. By applying this interdisciplinary theoretical framework, this study pinpoints the ideologies expressed within the memes. Further, we can ascertain which memes perpetuate societal stigma, and which memes challenge it. To examine how memes oppose normative societal attitudes, this study draws on Foucault’s (Citation1975) concept of counter-ideologies, which illustrates that resistance shapes the asymmetrical relationships between those in power and those who seek to dismantle this power. It also draws on Gal et al. (Citation2016) who propose that memes contain the subversive potential to deconstruct harmful ideologies and foster collective resistance. To provide further context to the analysis, this article draws on semi-structured interviews with activists that have been conducted as part of a wider project on mediatised menstrual activism.

Data collection

Instagram was selected as a social media platform because it is a digital space that is set up around the visual (Highfield and Leaver Citation2016). On 12th February 2020, “#periodmemes” was searched on Instagram and yielded 12,269 results. The first 220 publicly available posts were collected.Footnote2 In order to produce a snapshot of everyday social media interaction, “#periodmemes” was chosen to ensure multiple ideologies were present across the dataset. As they indicate a specific ideology, hashtags such as “#periodpositive” or “#periodproblems” would be inappropriate for this study.

Coding process

The dataset was imported into Nvivo in order to identify themes and to monitor how many memes either perpetuated, or challenged, menstrual stigma. To categorise the themes, the coding process drew on Van Dijck’s (Citation2009) semantic macro-analysis. The codebook was created by combing a data-driven inductive approach with a template of codes that were based on the theoretical framework outlined above (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2016). The codes “concealment imperative” (Wood Citation2020) and “menstrual crankiness” (Przybylo and Fahs Citation2020) relate directly to theories from sociological literature, whereas the codes “blaming men” and “men as allies” relate to themes explored within the memes ().

Table 1. Codebook.

Analytic process

Once the coding process was complete, the memes were analysed using MCDA. MCDA is a form of social semiotics “which is aligned with the project of revealing discourses, the kinds of social practices that they involve, and the ideologies that they serve” (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, 29). The analysis of the language and imagery in the memes was informed by Ledin and Machin’s Doing Visual Analysis (Citation2018). The method involved identifying semiotic features (such as style, medium and social actors) and then interpreting the ideologies that they evoke. By drawing on van Leeuwen’s work (Citation2008), this article examines how social actors are portrayed and whether these representations maintain, or problematise, menstrual stigma. Examining the affective functions of the memes is also a key to understanding their ideological position. Not only can strong emotional responses inspire a viewer to agree with a meme’s message, but also, as feminists have theorised, affect is central to societal perceptions of menstruation (Ussher Citation2006).

Analysis and discussion

The concealment imperative

The most prominent theme in the dataset draws on a societal expectation for menstruators to hide any signs that they are bleeding. Fifty-two memes were coded under “concealment imperative” (Wood Citation2020) because they play into a Foucauldian discourse of self-surveillance and reinforce the shame around menstruation. The fear of ridicule is strikingly apparent in a meme that includes the text: “Wtf are pads so loud? The whole bathroom don’t need to know I’m on my period.” The woman’s shame at her unsuccessful attempt to open a pad quietly supports Billig’s argument that embarrassment is a powerful affect that conditions social actors to adhere to normative codes of behaviour (Citation2005). The ideology that menstruation is a taboo subject that must remain invisible is reinforced by the lack of images in this meme. Thus, because it maintains the status quo, this meme is an example of “reinforcing humour” (Holmes Citation2000).

Discourses of “the monstrous feminine” are apparent in 21 memes (Ussher Citation2006). These memes echo feminist scholarship because, through words and/or images, they portray the female body as leaky and uncontrollable. Four memes, by parodying the fear of the visible menstrual stain, portray menstruators as social actors who must strictly monitor their bodies. If we view these memes in the light of van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) work, we can see that, by reducing them to a stereotype of the paranoid or hysterical woman, they otherise menstruators. Another stereotype conveyed in this dataset is that of the “messy” menstruator. Five memes depict women bleeding uncontrollably as they sneeze. One such meme uses a still from a horror film in which a screaming woman is drenched in a high volume of blood. This framing of menstruation within the horror genre portrays the female body as a signifier of dangerous feminine excess (Ussher Citation2006). Although these “monstrous” memes depict menstrual blood, and thus counter the “concealment imperative,” they do not normalise menstruation. Rather than reflecting everyday experiences of menstruating, the represented social actors in these memes bleed in an exaggerated manner that otherises menstruators and reinforces the ideology that they are abject (Van Leeuwen Citation2008). Thus, these memes are undermining activist efforts to destigmatise menstruation and educate the public. They may lead to non-menstruators having misconceptions about menstruation. This misinformation may be particularly damaging for young people who do not fully understand the biological aspect of menstruation (Young Citation2005).

Nevertheless, eight memes challenge this policing of gender norms through a critical lens (Abedinifard Citation2016). These memes draw on an experience to which many menstruators can relate: the self-policing act of hiding menstrual products from public view for fear of being “outed” as a menstruator (Young Citation2005). includes an illustration of a girl awkwardly carrying her bag after leaving a table of men. The choice to illustrate male friends, as opposed to women, is significant because it creates a strict gender division (Van Leeuwen Citation2008). The girl’s compulsion to hide her menstrual status from men suggests that it is not socially appropriate to discuss menstruation if men are present. The meme engages its viewers on an affective level in order to provoke their self-reflection (Gal et al. Citation2016). We feel an affective connection to the female character through the combination of her anxious inner monologue and her tense body language (she crosses her arms over her body defensively and protectively holds her handbag to signal her desperation that nobody realises that she is menstruating) (Ledin and Machin Citation2018). Her frustration and self-reflection are evident when she thinks “wtf does that even both me?” This question and her anxious body language illustrate the “self-objectification” from which she suffers because she chastises herself for perpetuating societal norms that dictate that women, in order that they conform to an idealised feminine image, must not let others know that they are menstruating (Fredrickson and Roberts Citation1997).

Another meme that states “smuggling pads to the bathroom like they’re some sort of illegal drug gotta be the worst adaptation to patriarchy” specifically relates this secrecy to patriarchal expectations. Thus, this meme echoes traditional approaches in feminist sociology (Chrisler Citation2013). This meme uses “contestive humour” (Holmes Citation2000) and a lexical field of criminality to subversively parallel concealing menstrual products and smuggling drugs. This discourse highlights the ridiculous nature of hiding menstrual products. By encouraging menstruators to defy the “concealment imperative,” this meme has the power to shape the asymmetrical relationship between menstruators and patriarchal power structures (Foucault Citation1975). Nevertheless, the meme does not include any images, such as of menstrual blood or products, and thus, somewhat ironically, contributes to the secrecy that it seeks to criticise.

The “concealment imperative” and societal taboos are resisted in 11 memes that include illustrations and photographs of menstrual blood (Wood Citation2020). This counter-ideology rebels against the status quo and offers a way for menstruators to collectively challenge a harmful ideology that prohibits all visible manifestations of menstruation (Gal et al. Citation2016). The photographs have a high level of modality and thus present the viewer with realistic, and relatable, everyday menstrual experiences such as blood-stained underwear and used tampons (Ledin and Machin Citation2018). We can argue that the photographs of menstrual blood, because they confront viewers with the tabooed substance itself, are the most subversive. These memes, unlike those within the horror genre that exaggerate menstrual experience, resonate with one of the main aims of menstrual activism: to normalise the visibility of menstruation in the public space (King Citation2020a). In this way, these memes effectively contribute towards campaigns by activists to encourage open dialogue about menstruation.

Through their overt celebration of menstruation, six memes in the dataset ascribe to a “period positive” discourse. One meme juxtaposes an illustration of menstrual blood, labelled “art,” with a smiling cartoon uterus labelled “the artist.” By repositioning menstrual blood as a work of art, this meme creates a counter-ideology that diametrically opposes the notion of the “monstrous feminine” (Ussher Citation2006). This meme, therefore, mirrors contemporary menstrual art projects, such as Jen Lewis’ collection “Beauty in Blood”, that seek to normalise menstruation through highlighting the aesthetic beauty of menstrual blood (Manica Citation2017). Another meme includes a photograph of the drag queen, Manila Luzon, wearing a dress with a 5-foot menstrual pad on it. This photograph was originally posted by Luzon to protest the fact that the producers of RuPaul’s Drag Race banned her from wearing this dress on the show because it was “in bad taste” (Luzon Citation2019). The meme juxtaposes the image of Luzon entitled “me” next to a text that reads, “Other girls: ‘I can’t go, I’m on my period’.” Through a “period positive” discourse, this meme denounces both the “concealment imperative” and the societal expectation for women to restrict their movement during their menses (Rosewarne Citation2012). It adds a different perspective from that of the handful of existing research that considers menstruation through a queer lens (Rydström Citation2020). Rather than foregrounding transgender or nonbinary menstruators, the meme presents a non-menstruating queer figure who wishes to normalise menstruation in order that people of all genders feel empowered to talk about their menstrual experiences. As such, this meme “queers” societal ideologies about menstruation and destabilises hegemonic gender norms that treat menstruators as inferior and abject (Chrisler Citation2013; Abedinifard Citation2016). As of yet, menstrual advocates and researchers have not considered the role queer non-menstruating figures can play in addressing menstrual stigma. Such a line of enquiry may be fruitful, as it offers a different queer lens that helps to deconstruct the gender norms around menstruation.

Overall, these memes demonstrate that social media users are aware of menstrual stigma and are thinking critically about it. By indicating that menstrual stigma is a matter of public concern, they illustrate that the personal is political and the dismantling of stigma can be undertaken through popular culture and everyday social media interactions. Since they capture relatable experiences and problematise menstrual stigma in an engaging format, certain memes provide an effective tool for raising awareness of the impact of menstrual stigma. A small number of memes in this dataset reveal that “period positive” discourses are seeping into the public consciousness and people are responding by creating their own celebratory content. Nevertheless, the fact that many memes in this category perpetuate menstrual stigma, such as by mocking and otherising menstruators, highlights that activist work to change the narrative around periods is still of utmost importance.

The myth of the irrational female

As part of their efforts to destigmatise menstruation, activists also strive to change societal stereotypes about the mood and behaviour of menstruators. Emotion is the main theme of 62 memes in the dataset, thereby indicating that social media users view mood as a central aspect of menstrual experience. By characterising menstruators as emotionally unstable, 41 of these memes perpetuate the “myth of the irrational female” (Hughes Citation2018), thereby perpetuating problematic societal assumptions. One text-based meme states, “menstruation, mental breakdown, and menopause all contain the word men.” Although this meme subversively illustrates that men are at the root of women’s oppression, and thereby resonating with feminist studies that claim that menstrual stigma is a result of patriarchal power structures, it problematically links menstruation to mental disorder. Hence, this meme not only perpetuates a harmful societal perception of menstruating women as mentally ill, it also belittles people with menstrual health conditions, such as PMDD, that can engender menstruators to feel depressed or overwhelmed (King Citation2020b). It therefore is an example of “reinforcing humour” which, albeit seeming feminist on the surface, is arguably misogynistic because it uses “divisive humour” that stems from a Freudian discourse of women as pathologically hysterical (Gottlieb Citation2020). Memes such as this exemplify the harm that can be caused by representing complex issues, such as mental health, in a simple meme format, as this can lead to the spread of destructive stereotypes that trivialise and alienate those who have mental health concerns.

By feeding into a discourse that frames menstruating women as a peril, 13 memes in this dataset include semiotic elements that present women as irrational (Chrisler Citation2013). One meme symbolises the threatening menstruator with a photograph of a small angry dog who bears a note that reads “will bite.” The semiotic resources of this meme reaffirm gendered power relations through characterising women as weak and hysterical (King Citation2020b). Adding to this imagery of menstruators as dangerous, one user adapts a popular meme in which Kermit the frog gazes at a version of himself wearing a black hood. The menstrual meme captions this image “Period: Cry, Me: What?? Why?, Period: START A FIGHT.” The normal rational “me” is juxtaposed with the irrational “period” that causes the menstruator to act aggressively and irrationally. As sociological studies argue, this positioning of the non-menstruating body as “normal” pertains to a power structure in which the non-menstruating body is the default (Ussher Citation2006). By playing into a binary discourse of normal/abnormal, this meme otherises menstruators. As such, it harmfully maintains sexist social structures and directly undermines the work of activists to normalise menstruation (King Citation2020a).

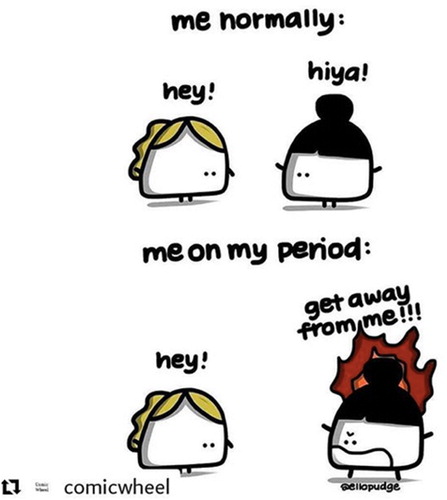

In fact, eight memes across the dataset construct a “normal/abnormal” binary, thereby indicating the continued importance of efforts by activists to convince the public that menstruation is a normal and healthy experience. is particularly essentialist in its characterisation of women as irrational and unable to control their emotions. This meme juxtaposes two contrasting illustrations of female stick figures greeting each other underneath the captions “me normally” and “me on my period.” The fire on the figure’s head, the statement, “get away from me,” and the three exclamation marks, signify her rage and a desire for isolation. By using stick figures, rather than photographs of women, it treats menstruating women as stereotypes rather than individuals. Thus, the meme’s low level of modality otherises and dehumanises menstruators (Van Leeuwen Citation2008). Its essentialist treatment of menstruators is evident in the lack of explanation as to why the stick figure is angry, or whether this is a typical response. In this way, it alienates menstruators with severe PMS symptoms, such as those with PMDD, who must deal with the ramifications of their mental health on their interpersonal relationships.

As this section demonstrates, the vast majority of memes that portray the moods of menstruators perpetuate “the myth of the irrational menstruator” (King Citation2020b). By characterising menstruators as irrational, depressed, aggressive, and abnormal, their humour reinforces stigma and silences menstruators who suffer from mental health issues. This finding will be of great concern to menstrual activists because it illustrates that the emotions of menstruators are still subject to mockery in the public space and an immense social change is needed to dispel such harmful attitudes. These memes indicate that the public is unaware that emotional outbursts are atypical and has no knowledge of conditions such as PMDD. Thus, menstrual activists must continue to provide information as to which emotional responses are typical or atypical so that people can understand if they require medical support.

There are, however, two memes within this dataset that propose a counter-ideology. They denounce the terms “emotional,” “hysterical,” and “dramatic.” Both memes include the rhetorical question “Isn’t it weird how?” before criticising cisgender men for deriding women’s struggles when they have no idea how menstrual cramps feel. This rhetorical device, because it encourages viewers to reflect on why women have internalised the idea that they are irrational, illustrates the value of the meme format as a rhetorical tool for feminist consciousness-raising (Dubriwny Citation2005). The other meme refers to “people who menstruate” rather than to women. This meme therefore echoes a push towards inclusivity within recent menstrual activism (Hughes Citation2018). Across the entire dataset, only five memes use either “menstruator” or “people with periods.” Although the term “people who menstruate” is gender neutral, recent controversies (such as J.K Rowling’s tweet in which she claims that this term effaces women) signal that “people with periods” can be perceived as ideologically loaded. Rowling’s tweet was criticised by the LGBTQ+ community who argued that it erased transgender men and nonbinary people who menstruate (Pink News, June 7, 2020). Thus, we can argue that the gender-neutral memes are not devoid of ideology because they are making a political statement that supports transgender and nonbinary menstruators. Gender-inclusive language aligns with the campaigns of transgender activists such as Kenny Ethan Jones (Citation2020) who talks publicly about his menstrual experiences and advocates for the provision of menstrual product bins in men’s bathrooms.

Solidarity and collective resistance

So far, the memes that have featured in this article focus on individual menstruators. This finding suggests that social media users perceive menstruation as a personal matter, rather than an experience that could unite people or that could benefit from political action. A discourse of solidarity is part of the lexicon of menstrual activists because they suggest that the candid sharing of menstrual experiences has the potential to eradicate stigma and shame (Fahs Citation2016). Social media is an ideal platform for fostering feelings of belonging that can inspire collective resistance against harmful societal norms (Morrison Citation2019). Eight memes combine humour and a “period positive” discourse to emphasise the power of feminist collective resistance (Gal et al. Citation2016). This discourse of sisterhood echoes recent trends on social media, epitomised in hashtags such as #MeToo and #BlackGirlMagic, that underscore women’s mental resilience and perpetuate the ideology that collective action empowers women (Morrison Citation2019). Nevertheless, due to the lack of nuance that can be encapsulated in the meme format, it is unclear how menstruators should respond to memes that call for unity. As studies have demonstrated, the ambiguous nature of online discourses of solidarity can actually work to erase, rather than unite, particular groups of women (Bouvier Citation2019). As Przybylo and Fahs (Citation2020) concept of “menstrual crankiness” indicates, “period positive” discourses erase the experiences of menstruators who have troublesome periods. Indeed, as none of these eight memes adopt an intersectional perspective, they do not include within their messages of solidarity people who live with conditions such as PMDD or endometriosis.

best embodies the belief that a “period positive” discourse can create a sense of collective pride amongst menstruators and, as a result, empower them. This meme combines a photograph of Katniss from the film, The Hunger Games (2012), and the caption “when you hear someone open a pad in the bathroom.” By analysing the semiotic resources of this meme, we can understand its potential to engage its audience on an affective level. The three-fingered hand gesture and gaze to the sky express Katniss’ defiance. By looking upwards, she elevates other menstruators and shows that she respects them (Van Leeuwen Citation2008). Her arrows frame Katniss as a menstrual warrior who is ready to fight in solidarity with others for a world without menstrual shame. This meme lies in stark contrast to the memes analysed previously that, by bemoaning the loud noise made by the opening of menstrual products, reinforce the “menstrual concealment imperative” (Wood Citation2020). By framing menstruation as an experience that can unite people, the Katniss meme celebrates social actors who, by making their status as menstruators apparent, do not conform to normative expectations. By including a powerful character from popular culture who acknowledges and commends others, draws on the affective ties that can unite menstruators. In so doing, it convinces its audience to empathise with, and empower, other menstruating people. By embodying a spirit of social protest against the concealment imperative, it transforms menstruation into a collective political act (Wood Citation2020).

Another pertinent finding in this category is the potential of memes to re-appropriate popular culture as a form of counter-ideology. Such memes present social media users with characters that they recognise, and juxtapose them with a humorous comment so that viewers can more readily identify with their messages of solidarity. Besides the Katniss meme, we can also find a “period positive” meme that includes a photograph of Lucille Bluth from the television series Arrested Development. The meme captions this photograph: “when I see a fellow menstruator at the supermarket buying period products, cupcakes and red wine.” Although it plays into a problematic ideology that menstruators are always craving unhealthy food, this meme evokes the affective ties between menstruators and positions menstruation as an experience worthy of celebration (Ussher Citation2006). Thus, the Katniss and Lucille memes offer a twist on the predominating ideology within critical menstrual studies that popular culture merely exploits menstruators for comedic effect (Hughes Citation2018). Both memes demonstrate that re-appropriation can be a powerful counter-ideology and that menstrual memes have the potential to catalyse a shift in the narratives that we witness in popular culture.

Men in menstrual memes: enemies or allies?

In addition to underlining the importance of fostering a collective consciousness amongst people with periods, advocates also emphasise that societal attitudes will not significantly change until cisgender men are included in conversations about menstruation alongside people who menstruate (Grace Citation2020a). Indeed, three memes that were categorised under “men as allies” express that men, by listening to and expressing compassion towards women, are key contributors to the social movement to normalise menstruation. One meme includes an image from the film Toy Story (1996), in which the excited Buzz explains something to Woody. Buzz is captioned “Me, telling a boy how terrible my period is” and Woody is labelled “The Boy.” By representing a frank dialogue between a man and a woman, this meme breaks down the boundary between these two sexes and encourages social actors of all genders to take part in open discussions about menstruation. Another meme includes a screenshot of a tweet by a man who labels women as “superheroes” for enduring painful cramps. This meme employs a “period positive” discourse to illustrate that men, by celebrating the strength and resilience of menstruating women, can contribute to efforts towards destigmatising menstruation. As they celebrate men who engage in open and supportive conversations about menstruation, the memes in the “men as allies” category effectively shatter hegemonic gender norms (Abedinifard Citation2016).

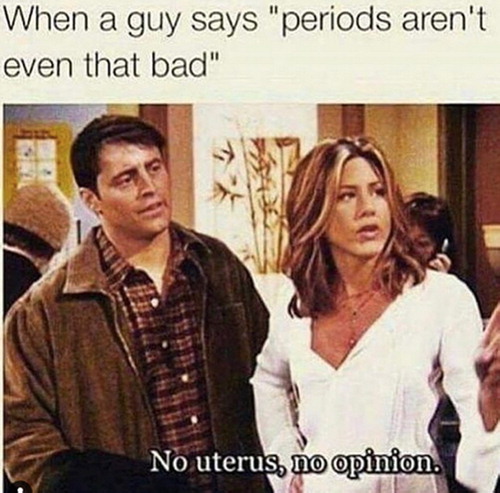

Nevertheless, the “men as allies” ideology only applies to a very small proportion of memes that depict men. 21 memes use “divisive humour” that pits male and female social actors against each other. This binary approach suggests that social media users see men as oppressors, rather than potential allies in the movement to destigmatise menstruation. Even though one could argue that these memes may have a positive impact on women, such as engendering feelings of solidarity or igniting a righteous anger that may lead to their engaging in collective acts of resistance against menstrual stigma, it cannot be denied that these memes undermine the work of activists to include men in conversations about menstruation (Grace Citation2020a). is representative of this online trend to portray cisgender men as ignorant social actors who are at fault for perpetuating harmful stereotypes. In a still from the sitcom, Friends, Rachel and Joey look over at Ross (who is not pictured in the meme). In this scene, Rachel exclaims: “No Uterus, No opinion” after Ross dismisses the pain of her Braxton Hicks contractions. The meme has changed the topic of this scene from pregnancy to menstruation and has removed Ross from the conversation. The meme, therefore, turns Rachel’s statement from a rebuttal to a specific man (Ross), into an expression of anger against men in general. Rachel’s commanding pose and aggressive waving of her finger demonstrate her contempt for, and superiority over, the absent man. By positioning the invisible man as a symbol of an evil patriarchy that is to blame for women’s suffering, the meme criticises asymmetrical gendered power relations within society (Ferreira and Vasconcelos Citation2019). The meme’s attempt to invert these power structures is reinforced by the man’s invisibility and lack of response. His absence, and Rachel’s unwillingness to enter into a dialogue with him, suggests his insignificance and takes away his agency. In this way, this meme typecasts men as the enemies of women (Van Leeuwen Citation2008). It refuses men the opportunity to improve their knowledge about menstruation and therefore for them to be able to better support their female friends and family. Hence, in trying to invert the gendered power relations between men and women, this meme fails to actually deconstruct gender inequality because it otherises men and dismisses their potential as allies. Thus, the 21 memes that blame men for menstrual stigma are an ineffective form of social protest because, in their perpetuation of destructive stereotypes about men, they impede, rather than advance, the menstrual movement.

Periods are political

So far, the memes that have been analysed only engage with two objectives of menstrual activism: destigmatisation and gender inclusivity. Indeed, as 114 memes allude to harmful stereotypes about menstruators, it is stigma that predominates the dataset. This demonstrates that, of all aspects of menstrual activism, the public is most concerned with stigma. Looking at the majority of the memes, it is difficult to discern whether this preoccupation reflects a conscious political choice to raise awareness about menstrual stigma, or whether it reflects internalised attitudes about which social media users are unaware. Two of these memes, however, demonstrate an explicit political engagement, and thus, alongside the memes that portray topics such as period poverty and the environmental impact of single-use menstrual products, they were coded as “political messages.” These two memes, in contrast to the other 112 memes about stigma, do not employ humour and, instead, attempt to shock their audience into supporting their ideologies. One depicts a photograph of a menstrual pad on which a printed message asks the viewer to imagine a world in which men were as disgusted with rape as they are with menstrual blood. The semiotic recourses of this meme and its high level of modality, including the photographed pad and the word “rape” that is printed upon it, emphasise the taboo nature of menstruation through realism and a stark black and white filter (Ledin and Machin Citation2018). Once again, we find a meme that attempts to deconstruct hegemonic gender norms whilst also, by enforcing a binary divide between male and female social actors, inadvertently maintaining societal power structures (Abedinifard Citation2016). This comparison of rape and menstruation is problematic because it links menstruation with sexuality and violence. This meme undermines the messages of menstrual activists who, in order to encourage young people to believe that menstruation is a comfortable subject to discuss, aim to uncouple societal associations between menstruation and sex (Boateng Citation2020). Hence, even if memes are created with an intent to inspire social change, their semiotic resources can convey conflicting messages that could undermine the messages of menstrual activists (Billig Citation2005). If activists consider using memes as a tool for destigmatising menstruation, they must think carefully about the connotations of the memes that they create so that they can avoid perpetuating any problematic ideologies.

“Period poverty” is another topic with which memes politically engage. This term, first coined as a catchy phrase by the media, refers to the struggles of menstruators to afford menstrual products (Astrup Citation2018). As a crisp photograph, has a high level of modality and allows younger viewers to identify with its message through the depiction of a realistic classroom setting. By focusing on social actors who are at school, it mirrors the mainstream media that primarily frame period poverty as an issue for school-aged girls (Astrup Citation2018). This meme raises awareness of period poverty and employs humour to gently persuade girls to talk about menstruation. By imagining themselves in the place of the girl labelled “me,” school-aged girls can insert themselves into the scenario and readily absorb its message. The phrase, “happened to mention she has her period,” normalises menstruation because it implies that the girl is casually discussing the topic without shame as a typical aspect of everyday conversation. This is a fantastic example of how memes can be used to capture political messages and make them appealing to younger people.

Other political messages in the dataset include environmentalism, such as one meme that advocates for the use of reusable menstrual products. Two memes reflect a discourse of “menstrual crankiness” in their recognition of the realities of menstrual pain (Przybylo and Fahs Citation2020). Four memes use humour to raise awareness of menstrual health issues, including endometriosis and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). One meme describes the symptoms of PCOS with an image of the children’s character SpongeBob SquarePants. SpongeBob looks simultaneously at two pages of a book that are titled “cramps” and “extensive blood flow.” This meme may foster a sense of solidarity among social actors who have been diagnosed with this condition. Other social media users may recognise these symptoms and, as a result, seek medical advice.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings of this article demonstrate that negative discourses about menstruation are still very much part of everyday experience. Activists must therefore continue their efforts to normalise menstruation within the public space. Indeed, the scale of the issue is demonstrated by the fact that 152 of 220 memes perpetuate menstrual stigma through “reinforcing humour” (Holmes Citation2000). The semiotic resources of these memes encapsulate discourses such as “the myth of the irrational female” (King Citation2020b), the “monstrous feminine” (Ussher Citation2006) and “the menstrual concealment imperative” (Wood Citation2020). By illustrating the relevance of Billig’s (Citation2005) theory to menstrual experience, this article has contributed to critical menstruation studies. For instance, future studies could use this framework to examine the potential of humour to change societal attitudes towards menstruation. Since this article illustrates that characters from popular culture can be re-appropriated humorously to challenge menstrual stigma, it calls for scholars within critical menstruation studies to revaluate the role of popular culture in shaping societal attitudes towards menstruation.

Although stigmatising discourses prevail in the dataset, this article demonstrates the potential of the meme format to advance arguments and inspire social action (Grundlingh Citation2018). Indeed, 68 memes resonate strongly with the objectives of menstrual activists, therefore suggesting that the public is starting to become aware of their messages. Many of these memes challenge the status quo through the use of “contestive humour,” whereas others impart a more serious tone (Holmes Citation2000). However, the potential of these memes to enact political and social change could be more accurately evaluated through analysing online comments and conducting focus groups. This article suggests that such research is the next logical step to better understand the potential of menstrual memes to inspire social action.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maria Kathryn Tomlinson

Maria Tomlinson is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Sheffield and is leading her own research project entitled: “Menstruation and the Media: Reducing Stigma and Tackling Inequalities”. For this project, she is analysing digital media, interviewing activists, and conducting focus groups in schools. Her specialist areas include the body, gender, feminism, sociology, and the media.

Notes

1 The second-wave feminist movement, which began in the 1960s, moved beyond a focus on suffrage (as epitomised by the first wave) to consider concerns such as sexuality and reproductive rights. The French second-wave feminists were particularly interested in how women’s corporeal experiences are shaped by language.

2 To ensure the privacy of the Instagram users, this article neither provides usernames nor links.

References

- Abedinifard, M. 2016. “Ridicule, Gender Hegemony, and the Disciplinary Function of Mainstream Gender Humor.” Social Semiotics 26 (3): 234–249.

- Astrup, J. 2018. “Period Poverty: Tackling the Taboo.” Community Practitioner 90 (23): 40–42.

- Billig, M. 2005. Laughter and Ridicule: Towards a Social Critique of Humour. London: Sage.

- Bing, J. 2004. “Is Feminist Humour an Oxymoron?” Women and Language 27 (1): 22–33.

- Boateng, S. 2020. Interview by Maria Tomlinson.

- Bobel, C., and B. Fahs. 2020. “The Messy Politics of Menstrual Activism.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, edited by C. Bobel, I. Winkler, B. Fahs, K.A. Hasson, E.A. Kissling and T.A. Roberts, 1001–1018. Singapore: Palgrave.

- Bouvier, G. 2019. “How Journalists Source Trending Social Media Feeds.” Journalism Studies 20 (2): 212–231.

- Chrisler, J. 2013. “Teaching Taboo Topics: Menstruation, Menopause and the Psychology of Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 35: 202–214.

- De Cook, J. 2018. “Memes and Symbolic Violence: #Proudboys and the use of Memes for Propaganda and the Construction of Collective Identity.” Learning, Media and Technology 43 (4): 485–504.

- Dubriwny, N. 2005. “Consciousness-Raising as Collective Rhetoric: The Articulation of Experience in the Redstockings’ Abortion Speak-Out of 1969.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 91 (4): 395–422.

- Erchull, J. 2013. “Distancing Through Objectification? Depictions of Women’s Bodies in Menstrual Product Advertisements.” Sex Roles 68: 32–40.

- Fahs, B. 2016. Out for Blood: Essays on Menstruation and Resistance. New York: University of New York Press.

- Fereday, J., and E. Muir-Cochrane. 2016. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (1): 80–92.

- Ferreira, M., and M. Vasconcelos. 2019. “(De)Memetizing Antifeminist Ideology.” Bakhtiniana 14 (2): 46–64.

- Foucault, M. 1975. Surveiller et Punir: Naissance de la Prison. Paris: Gallimard.

- Fredrickson, B. L., and T. A. Roberts. 1997. “Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 21: 173–206.

- Gal, N., L. Shifman, and Z. Kampf 2016. “It Gets Better: Internet Memes and the Construction of Collective Identity.” New Media & Society 18 (8): 1698–1714.

- Gottlieb, A. 2020. “Menstrual Taboos: Moving Beyond the Curse.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, edited by C. Bobel, I. Winkler, B. Fahs, K.A. Hasson, E.A. Kissling and T.A. Roberts, 143–162. Singapore: Palgrave.

- Grace, E. 2020a. Interview with Maria Tomlinson.

- Grundlingh, L. 2018. “Memes as Speech Acts.” Social Semiotics 28 (2): 147–168.

- Highfield, T., and T. Leaver. 2016. “Instagrammatics and Digital Methods: Studying Visual Social Media, from Selfies and GIFs to Memes and Emoji.” Communication Research and Practice 2 (1): 47–62.

- Holmes, J. 2000. “Politeness, Power and Provocation.” Discourse Studies 2 (2): 159–185.

- Hughes, B. 2018. “Challenging Menstrual Norms in Online Medical Advice: Deconstructing Stigma Through Entangled Art Practice.” Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics 2 (2): 1–15.

- Irise International. 2020. “The Empower Period Podcast.” Episode 3. “Leading the Change: Menstrual Advocacy in Zimbabwe”. https://feeds.buzzsprout.com/1160294.rss.

- Jones, K. 2020. Interview by Maria Tomlinson.

- King, S. 2020a. Interview with Maria Tomlinson.

- King, S. 2020b. “Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) and the Myth of the Irrational Female.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, edited by C. Bobel, I. Winkler, B. Fahs, K.A. Hasson, E.A. Kissling and T.A. Roberts, 287–302. Singapore: Palgrave.

- Kligler-Vilenchik, N., and K. Thorson. 2016. “Good Citizenship as a Frame Contest: Kony2012, Memes, and Critiques of the Networked Citizen.” New Media & Society 18 (9): 1993–2011.

- Kristeva, J. 1980. Les Pouvoirs de L’Horreur. Paris: Seuil.

- Leclerc, A. 1974. Parole de Femme. Paris: Gallimard.

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2018. Doing Visual Analysis. London: Sage.

- Luzon, M. 2019. “Ru said my ORIGINAL Curves and Swerves Runway Look was in ‘bad taste’.” Accessed May 2019. https://www.instagram.com/p/BsUaPvenYcj/.

- Manica, D. 2017. “(In)Visible Blood: Menstrual Performances and Body Art.” Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 14: 1–25.

- McHugh, M. 2020. “Menstrual Shame: Exploring the Role of ‘Menstrual Moaning’.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, edited by C. Bobel, I. Winkler, B. Fahs, K.A. Hasson, E.A. Kissling and T.A. Roberts, 409–422. Singapore: Palgrave.

- Morrison, A. 2019. “Laughing at Injustice: #DistractinglySexy and #StayMadAbby as Counternarratives.” In Digital Dilemmas: Transforming Gender Identities and Power Relations in Everyday Life, edited by Diana Parry, 23–52. London: Palgrave.

- Przybylo, E. and B. Fahs. 2020. “Empowered Bleeders and Cranky Menstruators: Menstrual Positivity and the “Liberated” Era of New Menstrual Product Advertisements.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, edited by C. Bobel, I. Winkler, B. Fahs, K.A. Hasson, E.A. Kissling and T.A. Roberts, 375–394. Singapore: Palgrave.

- Rosewarne, L. 2012. Periods in Popular Culture: Menstruation in Film and Television. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

- Rydström, K. 2020. “Degendering Menstruation. Making Trans Menstruators Matter.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, edited by C. Bobel, I. Winkler, B. Fahs, K.A. Hasson, E.A. Kissling and T.A. Roberts, 945–959. Singapore: Palgrave.

- Ussher, J. 2006. Managing the Monstrous Feminine: Regulating the Reproductive Body. New York: Routledge.

- Van Dijck, J. 2009. ““Users Like you?” Theorizing Agency in User-Generated Content.” Media, Culture and Society 31 (41): 41–59.

- Van Leeuwen, T. 2008. Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wells, D. 2018. “You All Made Dank Memes: Using Internet Memes to Promote Critical Thinking.” Journal of Political Science Education 14 (2): 240–248.

- Wiggins, B. 2019. The Discursive Power of Memes in Digital Culture: Ideology, Semiotics and Intertextuality. New York: Routledge.

- Wood, J. 2020. “In Visible Bleeding: The Menstrual Concealment Imperative.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, edited by C. Bobel, I. Winkler, B. Fahs, K.A. Hasson, E.A. Kissling and T.A. Roberts, 316–336. Singapore: Palgrave.

- Young, I. 2005. On Female Body Experience: “Throwing Like a Girl” and Other Essays. New York: Oxford University Press.