ABSTRACT

This discussion paper explores street art from the point of view of assemblages: What different elements and artefacts converge to give meaning and politics to art works? How do we understand the interactions of artworks, streets, viewers, politics, and discourse that render a work of art a happening rather than an object? Processes of artification depend on material, contextual and symbolic relations that bring together style, place, artists, viewers, city tours and city ordinances into a semiotic assemblage of art in the street. To arrive at a critical understanding of street art, we need to avoid assumptions about transgression, complicity, gentrification, or commodification, and focus instead on assemblages of art, viewers, and economic, political, and urban interests in specific locations. The question is how different elements – ownership and rights to space, capitalist expansion and appropriation, rebellion, and transgression – become entangled in semiotic assemblages that enable us to see the interactions of street art dynamics.

KEYWORDS:

Street art as happenings

By looking at the commission, production, consumption and contestation of street art, the papers in this special issue point not only to the semiotics of art works in the street, but also to the many forces around them, from entrepreneurial interests to policy makers and local residents, from discourses about the city to regeneration processes and urban renewal. In order to make sense of these multiple factors that intersect around street art, in this paper I shall explore the idea of street art assemblages as a way to account for the dynamic relations among semiotics, cities, public domains, politics, economy and art. The notion of assemblages, addressed explicitly in some papers (and implicitly in others) – Snajdr and Trinch talk of shopfront signs as “a semiotic assemblage of text, colour, design, and graphic elements;” Gonçalves views the house murals as a “semiotic assemblage inside the vicinity”; and Milani talks of “the Walled Off Hotel as a street-art assemblage” – provides a useful way to think about the many elements that come together around any piece of street art. This is not a focus on assemblage art – artistic works produced by bringing various artefacts together (though this gives us a useful indication of how assemblages work) – but street art as assemblage.

What different elements and artefacts converge to give meaning and politics to art works? How do we understand the interactions of artworks, streets, viewers, politics, and discourse that render a work of art an event rather than an object: “Thinking through assemblage urges us to ask: How do gatherings sometimes become ‘happenings,’ that is, greater than the sum of their parts?” (Tsing Citation2015, 23). The concept of semiotic assemblages “helps us to appreciate a much wider range of linguistic, artefactual, historical, and spatial resources brought together in particular combinations and in particular moments of time and space” (Sharma Citation2021, 68). In this afterword, I shall draw on the papers in this special issue as well as other materials to explore questions about street art from three perspectives: how street art is defined not only by style and place but also be viewers and city regulations; how art, viewers, economic, political and urban interests converge in particular locations; and how public art enters into public discourse, into the ways the city is talked about. This suggests that to understand street art we need to bring together a critical focus on semiotics, place, ownership, discourse, and political economy, on the ways in which politics and semiotics are entangled.

Art and the street

I want to start first by asking how an assemblage focus can help us think about what constitutes art: When are words art and for whom is art art? For Heinich and Shapiro (Citation2012) the question is one of artification – the symbolic, material, and contextual processes by which something becomes art. Is “street art” an overriding category that includes graffiti (as the title of the special issue suggests) or are they usefully separated (the editors nonetheless talk of “graffiti and street art” in the introduction; and see, for example, Campos Citation2015; Campos, Zaimakis, and Pavoni Citation2021). Järlehed meanwhile gives us art on the street, drawing attention to the social meanings and discourses around two proposed food-based sculptures, while Snajdr and Trinch’s “art activism” might be termed “art of the street” (photographs of shopfronts). To this we can also add the notion of “public art,” explained by Fernandez-Barkan as art that is explicitly funded or supported by various levels of government. Although these definitional differences cannot (and need not) be easily resolved, probing a little further here can shed light on what is at stake across these articles. Since the introduction to this Special Issue starts in Paris and an injunction not to “bomb” the Eiffel tower, let us move a few kilometres east from the 7th arrondissement to the 19th and 20th arrondissements and the districtFootnote1 of Belleville. This inner-city neighbourhood is known for its working-class history (residents were strong supporters of the Paris Commune in 1871), wide contemporary ethnic mix (Chinese, Vietnamese, North and sub-Saharan African), and artistic communities (not art galleries but street art).

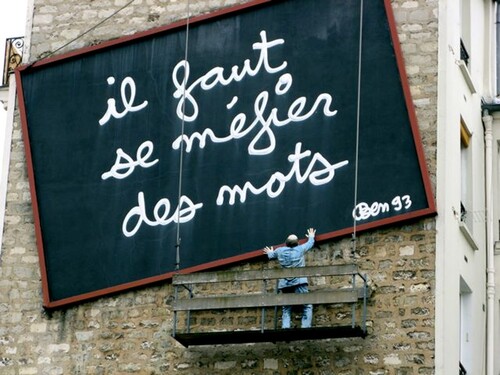

Above the door of #72 Rue de Belleville, a plaque claims (probably apocryphally) that the singer Edith Piaf was born in destitution (“dans le plus grand dénuement”) on the steps of this house on 19th December 1915. The plaque itself is not street art (linguistic landscape studies would claim it, but not street art studies) though it points to both the poor and artistic heritage ideologies of the district. Piaf herself started as a street artist (a singer; I shall return to this issue later). A hundred metres down Rue de Belleville is a well-known piece of street art (). This work, by Ben Vautier, apparently showing two workers (only one worker is shown here) positioning a large blackboard on the side of a house with the words “il faut se méfier des mots” – do not trust words – has been in place for almost three decades and is a common stopping-off point for the street art tours of Belleville. Another popular stop on these tours is the graffiti alley (Rue Dénoyez) further down the hill, closer to the Belleville Metro station. This laneway has long been the domain of graffiti artists. While on one level it is an ever-changing wall-canvas of new work (unlike the stable and unchanging “il faut se méfier des mots” up the hill), at the same time it is a stable, recognised, and regulated site. There are tables from the Aux Folies bar on the corner, where you can have a drink below the multicoloured walls (), and artists now work in public view during the day ( and ).

When we ask questions about what is going on here not so much in terms of artistic quality, high and low art, or aesthetics, but rather what it is that makes these creations art (Heinich and Shapiro Citation2012), it becomes important to bring in a range of actants. “Street” and “art” don’t always sit easily together: Street artists – buskers, graffiti artists, human statues – are often seen by both the inhabitants of the streets and the world of artists as unsuccessful performers – vandals, radicals, dropouts, misfits – who never made it into the capitalist embrace of galleries, museums, live venues, or concert halls. As Kramer points out the art world tends to position graffiti somewhere on the other end of the scale of quality from high art, as “urban,” “street,” “subway” or “aerosol” art. Even though the 5Pointz lawsuit discussed by Kramer was pursued in the name of artists’ rights, the art world still looks down on the world of graffiti. The designation “street” orients the art a little differently from other terms – such as “public” which itself may refer widely to art in the public domain or more narrowly to publicly-funded art (Fernandez-Barkan; Järlehed) – both limiting the scope (street art is neither in galleries nor in parks) and bringing a focus on popular, underground, or resistant culture (like “street language” designating urban, colloquial slang).

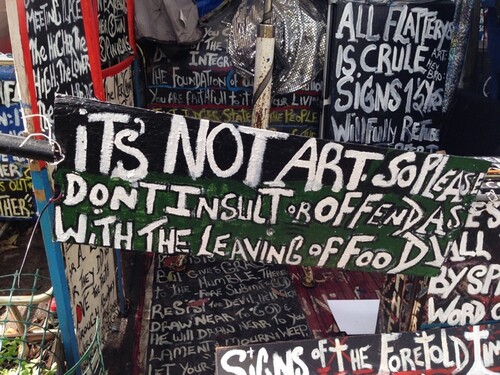

The editors point to the importance of a focus on the artists themselves – Gonçalves, for example, engages with both the street artist (RDO SAMP) and the consumers of the art as it shifts from the public to more private domains – but for some producers or viewers of art, this designation is contestable. As Fernandez-Barkan notes, graffiti from the perspective of the writers may be as much about sport, daring and transgression as it is about art. A park-dweller in Sydney, a wiry, grey-bearded man, had over a long period of time painted messages on black boards around his temporary accommodation, a mixture of religious cant and moral preaching (“Signs of the foretold times, Age of the Apostates” “Resist the Devil, He’ll draw near to God & he’ll draw near to you” and so on). Eventually he grew tired of his words being seen as art, as well as what he saw as the related patronising of artists by leaving food, eventually announcing (see ) “It’s not art. So please don’t insult or offend as with the leaving of food” (with an arrow originally pointing to food that had been left for him). Perhaps, like Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (this is not a pipe), this was about the treachery of images (la trahison des images) but unlike Magritte his point was not that an image is not the thing itself, nor that words are not the things themselves, but that his words are not art. As far as he was concerned, his texts were just that (perhaps messages from God) but definitely not art.

These examples illustrate several points. It is quite possible to draw a distinction between graffiti and other forms of street art in terms of style, scale, materials, position, financing, status, aesthetics, artists, and audience. It would be difficult to describe the blackboard on the wall as graffiti (in terms of style, position, official recognition), but the artwork in Rue Dénoyez clearly are graffiti in terms of the materials, style, and location (spray-painted work on walls). The incorporation of this alley into street art tours, however, as well as the accommodation with the bar on the corner, have changed the way it is perceived, regulated, or condoned. Such tours are now common across the world, from the tourist visits to Hosier Lane in Melbourne (Pennycook Citation2010) to the walking tours of Brooklyn (see Gonçalves Citation2019): there are also tours in Sydney, Tel Aviv, Bogota, Johannesburg, Los Angeles, Lisbon, Bristol – the home of Banksy, an artist who complicates distinctions among high and low art, street art, graffiti and value, and to whom we will return – and many other cities.

While there are therefore material and stylistic distinctions to be made among these forms, some assumptions – that street art is “visual” (images) and graffiti “textual” (words), for example – do not hold. The examples above reverse the distinction, the street art providing food for thought from its text (don’t trust words) – and compare Gonçalves (Citation2018) discussion of whether a piece of metrolingual street art in Brooklyn should be read as “YO” or “OY” – and the graffiti being predominantly visual (only insiders tend to know what text is encoded). Hip hop-style graffiti – rather than textual or politically-oriented graffiti – may be more about style, identity, and emplacement than direct meaning to passers-by from the wider community. Our park-dweller meanwhile reminds us that words in public space are not necessarily art, and that food for thoughts may not be welcome. All of this suggests that not only do public art, graffiti, and street art, as Fernandez-Barkan points out, depend on one another for their existence, but that processes of artification (Heinich and Shapiro Citation2012) depend on material, contextual and symbolic processes, bringing together style, place, artists, viewers, city tours and city ordinances into a semiotic assemblage of art in the street.

Politics and transgression

A common argument among graffiti artists is that the legally sanctioned billboards and advertisements that adorn urban environments are a greater eyesore than graffiti, and it is only the fact that capitalist-oriented laws make one legal and the other not that turns their art into an underground activity. From a graffiti artists’ point of view, graffiti is not vandalism – as it is often officially described – but public art (though not in the sense of being officially supported). It enhances rather than defaces public space. Street art can be about “conquering space” as RDO SAMP (Gonçalves) suggests. Graffiti have now also moved onto a variety of digital platforms (Blommaert Citation2016a; MacDowall and de Souza Citation2018) – it is common to post images online – changing the relation between local and wider audiences, as well as the architectures of design, production and reception. One goal of graffiti artists is to reach as many people as possible, hence the common use of digital platforms, transport (urban trains are a favourite) or places seen from forms of transport (bridges, tunnels, stations). As painted trains move around urban spaces, “semiosis is inseparable from mobility” (Karlander Citation2016, 41). This is not new, as Fernandez-Barkan reminds us, since public art has often been designed this way; indeed, the histories of public art and graffiti are intertwined and inter-dependent. For graffiti writers, their work is about style, space, identity, and reimagining the city, part of the interior design and soul of the city (Milon Citation1999; Pennycook Citation2010; Van Treeck Citation2003).

Graffiti are part of the struggle over the right to the city, about “what kind of social ties, relationship to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values we desire” (Harvey Citation2008, 23). This is not a question of individual access to urban resources so much as being part of the process of urban design, of the “collective power to reshape the processes of urbanisation.” If such rights are about opposition to capitalist control of urban development, graffiti artists may play an important role alongside attempts to reclaim local governmentality. A common line of distinction between public/street art and graffiti may be in terms of transgression, even of illegality: Street art has municipal support while graffiti generally do not. For Scollon and Scollon the occurrence of graffiti “in places in which visual semiosis is forbidden” (Citation2003, 149) render them as transgressive since “they are not authorised, and they may even be prohibited by some social or legal sanction” (Scollon and Scollon Citation2003, 151). And yet, as Jaworski and Thurlow (Citation2010, 22) make clear, it is an oversimplification to label all graffiti as transgressive since a violation of property rights from one perspective may be an affirmation of voice and identity from another. While the motives might be transgressive, the reception by different commercial and institutional actors may be different. As long as graffiti writers don’t challenge capital accumulation in real rather than symbolic terms, Kramer argues, their work can be accommodated. As the public spray work in Rue Dénoyez suggests, the transgressive impulses of graffiti are largely compromised when officially sanctioned.

The religious iconography on the back of St Luke’s Anglican Church, Enmore, Sydney () is favourably compared to the stained-glass windows of his church by Father Gwilym Henry-Edwards: “That medium of stained glass spoke very clearly to the people of the past, and this” he continues, gesturing to the wall of graffiti behind him, “speaks to people of the present and the future.” (Pennycook Citation2009). The move from transgression to acceptance is clear in Gonçalves’ discussion of the “street fetish” as a marker of class distinction, rendering forms of wall-painting attractive as part of emerging middle-class tastes (at least in some Brazilian contexts). While transgression may still be part of the “street” ideology of the artists, once they become part of city walking tours, graffiti lose their transgressive edge and become indistinguishable at the level of consumption (but not commission, support, or style) from street art. Parts of the graffiti world, as Blommaert (Citation2016a, 101) notes, have shifted from a “subversive, under-the-radar and illegitimate activity” to “a legitimate and popularly recognised form of art,” from “rebellion to avantgarde.” This is a tension in the graffiti world. I once sat in on a graffiti artists’ workshop in Sydney, where well-known artists spoke about their work, including the position some of them now held doing work paid for by municipal authorities: To avoid the constant buffing and bombing of certain tempting surfaces – cleaning of walls followed quickly by new works by graffiti artists – some councils commission works by well-known artists so that at least there is some control over the type and quality of the work, and it is less likely to get painted over. Other artists both admired and denigrated this: it was great to be able to work as a “professional” artist, but this was also “selling out”. To put their audience at ease, speakers assured the audience that they still did “illegal” work elsewhere.

To understand the larger political dimensions of street art, we need to be cautious about assuming transgressive or resistant motives or effects. We also need to be careful not to assume that alternative processes of incorporation can be easily interpreted. There is a tendency in current critical sociolinguistic work – and the editors emphasise that this is a “critical” examination of street art semiotics – to use terms such as “commodification,” “gentrification” or the all-embracing foe “neoliberalism” (“problematic buzzwords” as Milani calls them) without doing more explanatory work about what is at stake here. If we can show that language has been “commodified” or that economic interests are driving actions or ideologies, then we can call this out as “neoliberal”. For Snajdr and Trinch, the critical focus is on the “semiotic artefacts that contribute to the place-making being done and undone in Brooklyn’s gentrification” even though, as they also acknowledge, a “problem with salvage projects produced as art is that they are generally for elites.” Just as the “language endangerment” literature has been subjected to extensive critique (Cameron Citation2007) on the grounds that it affirms rather than challenges traditional views of language, so, when we look at street art – even when graffiti are part of a walking tour – we need to be cautious when we assume that a focus on commodification or gentrification necessarily constitutes a critical focus.

Just as critiques of “language commodification” have pointed to the problem of assuming a political economy of language while failing to adequately account for processes by which language can be understood as a commodity, or to distinguish between commodification as discourse and as a product of labour (Petrovic and Yazan Citation2021; Simpson and O’Regan Citation2018), so accounts of commodification or gentrification need to do more than point to the discursive production of such views. When it comes to complicity with neoliberalism, furthermore, we need as Blommaert (Citation2016b, 14; emphasis in original) argues, to show with granular precision what this means, rather than just assuming connections and implications: “if you intend to destabilise a hegemony, try to understand it; don’t simply dismiss neoliberalism as a mirage or just another ‘political ideology’, but study it.” What is meant by “critical” always needs to be open itself to critical inquiry (Pennycook Citation2022). If we think we can do anything as sociolinguists and social semioticians about neoliberalism, we need to study its workings and effects closely, rather than use it as an easy label of condemnation. Just because graffiti may at times have become part of a city’s tourist attractions, we should be cautious before jumping too quickly into critiques of complicity with neoliberalism. To arrive at a critical understanding of street art, we need to avoid assumptions about transgression, complicity, commodification and so on, and instead focus on assemblages of art, viewers, and economic, political, and urban interests in specific locations.

Multisensoriality, discourse, politics

The editors describe this special edition as “investigating street art (in its broadest form)”. As I suggested earlier, Edith Piaf was also a street artist in her early years, singing for her living. Clearly a broad approach to street art might include music. As visual art moves away from representational modes, it can also start to become like music, or be seen as an integrated whole, an assemblage. Rothko, as McNamara (Citation2021, 7) explains, “wanted painting to approximate to the condition of music: that is, to act as an abstract medium, like musical notes, capable of expressing, enacting and resolving dramas of feeling.” Music in the street is often intertwined with other forms of street art (), part of a larger multisensory assemblage. We do not engage with the world one sense at a time – indeed synaesthesic sensibilities may be the norm (Howes and Classen Citation2014) – and artists are often very aware of this. This suggests that the study of street art could be more inclusive: not just visual but also aural, and perhaps also include touch, taste, and smell – the less elite (not literacy-oriented) senses – and their interrelationships. If, as Levon (Citation2020) suggests, the sociolinguistic study of art includes viewers’ embodied and multimodal experience, semiotic analysis of street art might consider a multimodal and multisensorial assemblage approach to street art that includes multiple forms of art, embodied responses, discourses around the art and its emplacement, and wider concerns around the political economy and ecology of cities.

As the papers in this special issue make clear, street art is not only defined by its location but by its entry into public discourse. Järlehed’s study shows how artworks (never actually commissioned) enter into and produce public debate about who has the right to decide which food cultures can become part of the fabric of the city, leading to debates about Swedish society, welfare policies, migration, and integration. The interconnectedness of the semiotic, political, and economic aspects of street art – which can arguably be addressed through the idea of mediatisation (Milani; Järlehed) – suggest a range of wider concerns that are not so much beyond the semiotic but intertwined with it. Alongside definitional concerns, questions of who made it and who views it, and issues around who funds it, where it is placed, with what intention, and with what permission, there are also the kinds of discussion that ensue, the public, discursive and political realm in which street art (more so than gallery art) partakes. Public art, perhaps by the very fact of being officially sanctioned, may be more widely opposed than unsanctioned art. Recent campaigns against statues, particularly those of white men with clear links to colonialism or the slave trade, have shown public art to be a site of contestation. From the tipping of the statue of Edward Coulston into Bristol (UK) harbour (Banksy sold T-shirts to raise money for those accused of criminal damage, who were later found not guilty) or the “Rhodes must fall” movement – originally aimed at a statue at the university of Cape Town, but developing into a larger movement about decolonisation – to the spray painting of Captain Cook in Sydney or the tearing down of the statue of Joséphine de Beauharnais in Fort-de-France (wife of Napoleon, born to a sugar plantation-owning family and partly responsible for the re-institution of slavery in La Martinique in 1802) public statues are a key site of struggle over whose history matters.

Such monuments typically sustain hegemonic histories and spatial arrangements and are liable either to be attacked (the statue of Joséphine had already lost its head some years before) or to opposition through counter-monuments that contest these hegemonic histories (Krzyżanowska Citation2016). Graffiti or street art can also form this counter-hegemonic movement – the separation wall in Israel is adorned by protest graffiti (Hanauer Citation2011) (though as Milani points out, visitors may be more responsible for some of this than locals). Cities that have been major sites of conflict have also been major sites of political street art (Campos, Zaimakis, and Pavoni Citation2021): Graffiti as geographies of material protest in Cairo (Lennon Citation2014) or Belfast murals as actants in garnering cultural support for political organisations rather than just champions of ideological causes (Goalwin Citation2013). Walls around the world are currently starting to reflect the conflict in Ukraine (see Gonçalves and Milani, this issue). This is not only about whose version of the city – both past and present – matters but also about the role of graffiti or street art as actors in public debate. While art works depicting popular street foods are arguably already anti-elitist counter-monuments (working class fast food), Järlehed’s analysis of the competing images of Gothenburg as represented by two proposed art works – the hot dog (halv special) indexing the white male worker, and the falafel suggesting a more inclusive idea of the multicultural city – shows how such works become material anchors in debates about social life.

The entanglements of street art with a much wider circulation of discourse and material relations (Pennycook Citation2021), as well as the discussion of a broader semiotics (including singing, other forms of music, or perhaps street food), suggest that ideas such as semiotic assemblages (Pennycook Citation2019) might give us better purchase on the ways in which art, the street, the politics and the economy, the artists and the watchers are intertwined. This is about how an “assemblage of architecture, artefacts, and activities” shape public discourse (Jaworski and Gonçalves Citation2021, 58). We can see these elements come together, for example, in the Walled Off Hotel – this “large selection of street art and other creations, which makes the hotel a semiotic and material assemblage” – as Milani struggles with his conscience as he exits through the gift shop (echoing Banksy’s Citation2010 film Exit Through the Gift Shop), looking at various souvenirs of the graffitied wall or cups declaring “the worst view in the world”, considering how to understand the politics of this hotel, a space for a bourgeois gaze at a troubled wall, a politics entangled with Banksy’s history of street art and ironic engagement with the commercialisation of art, with the politics of Israel and Palestine and a walled-off two state solution. Bringing a critical focus to the discussion of street art entails investigations of ownership and rights to space, of capitalist expansion and appropriation, of rebellion and transgression, concerns about power, money, ideology, freedom of expression, censorship, and rights. The interesting question is how these become entangled in semiotic assemblages that enable us to see the interaction of these many aspects of street art.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alastair Pennycook

Alastair Pennycook is Professor Emeritus at the University of Technology Sydney and Research Professor at the MultiLing Centre at the University of Oslo. His most recent books include Innovations and Challenges in Applied Linguistics from the Global South (with Sinfree Makoni) and Critical Applied Linguistics: A Critical Reintroduction.

Notes

1 The term ‘quartier’ does not translate easily across languages and cities – in Australia all areas (inner and outer) of the city are suburbs; in the US, suburbs are usually wealthier and contrasted with inner city poverty; while in Paris, the suburbs – ‘faubourgs’ or ‘banlieues’ – are the poorer outer city regions contrasted with the inner-city quartiers (districts) and arrondissements of the city itself.

References

- Banksy. 2010. Exit Through the Gift Shop (Film). Revolver Entertainment.

- Blommaert, Jan. 2016a. “‘Meeting of Styles’ and the Online Infrastructures of Graffiti.” Applied Linguistics Review 7 (2): 99–115.

- Blommaert, Jan. 2016b. Superdiversity and the Neoliberal Conspiracy.” http://alternative-democracy-research.org/2016/03/03/superdiversity-and-the-neoliberal-conspiracy/.

- Cameron, Deborah. 2007. “Language Endangerment and Verbal Hygiene: History, Morality and Politics.” In Discourses of Endangerment: Ideology and Interest in the Defence of Languages, edited by Alexandre Duchêne, and Monica Heller, 268–285. London: Continuum.

- Campos, Ricardo. 2015. “Graffiti, Street Art and the Aestheticization of Transgression.” Social Analysis 59 (3): 17–40.

- Campos, Ricardo, Yiannis Zaimakis, and Andrea Pavoni. 2021. Political Graffiti in Critical Times: The Aesthetics of Street Politics. New York: Berghahn.

- Goalwin, Gregory. 2013. “The Art of War: Instability, Insecurity, and Ideological Imagery in Northern Ireland’s Political Murals, 1979–1998.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 26: 189–215.

- Gonçalves, Kellie. 2018. “YO! Or OY? – Say What? Creative Place-Making Through a Metrolingual Artifact in Dumbo, Brooklyn.” International Journal of Multilingualism 16 (1): 42–58.

- Gonçalves, Kellie. 2019. “The Semiotic Paradox of Street Art: Gentrification and the Commodification of Bushwick, Brooklyn.” In Making Sense of People, Place and Linguistic Landscapes, edited by Amiena Peck, Quentin E. Williams, and Christopher Stroud, 141–160. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hanauer, David. 2011. “The Discursive Construction of the Separation Wall at Abu Dis.” Journal of Language and Politics 10: 301–321.

- Harvey, David. 2008. “The Right to the City.” New Left Review 53: 23–40.

- Heinich, Natalie, and Roberta Shapiro. 2012. De L’artification. Enquêtes sur le Passage à L’art. Paris: EHESS.

- Howes, David, and Constance Classen. 2014. Ways of Sensing: Understanding the Senses in Society. London: Routledge.

- Jaworski, Adam, and Kellie Gonçalves. 2021. “High Culture at Street Level: Oslo's Ibsen Sitat and the Ethos of Egalitarian Nationalism.” In Spaces of Multilingualism, edited by Robert Blackwood, and Unn Røyneland, 135–164. London: Routledge.

- Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow. 2010. “Introduction.” In Semiotic Landscapes, Language. Image, Space, edited by Adam Jaworski, and Crispin Thurlow, 1–40. London: Continuum.

- Karlander, David. 2016. “Backjumps: Writing, Watching, Erasing Train Graffiti.” Social Semiotics 28 (1): 41–59.

- Krzyżanowska, Natalia. 2016. “The Discourse of Counter-Monuments: Semiotics of Material Commemoration in Contemporary Urban Spaces.” Social Semiotics 26 (5): 465–485.

- Lennon, John. 2014. “Assembling a Revolution: Graffiti, Cairo and the Arab Spring.” Cultural Studies Review 20 (1): 237–275.

- Levon, Erez. 2020. “Sociolinguistics + Art.” Journal of Sociolinguistics. Epub Ahead of Print, 1–2.

- MacDowall, Lachlan, and Poppy de Souza. 2018. “‘I’d Double Tap That!!’: Street Art, Graffiti, and Instagram Research.” Media, Culture & Society 40 (1): 3–22.

- McNamara, Tim. 2021. “Three Rothkos.” Journal of Sociolinguistics, 1–8.

- Milon, Alain. 1999. L'Étranger Dans la Ville: Du rap au Graff Mural. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2009. “Linguistic Landscapes and the Transgressive Semiotics of Graffiti.” In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by Elana Shohamy, and Durk Gorter, 302–312. New York: Routledge.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2010. “Spatial Narrations: Graffscapes and City Souls.” In Semiotic Landscapes, edited by Adam Jaworski, and Crispin Thurlow, 137–150. London: Continuum.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2019. “Linguistic Landscapes and Semiotic Assemblages.” In Expanding the Linguistic Landscape, edited by Martin Pütz, and Neele Mundt, 75–88. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2021. “Entanglements of English.” In Bloomsbury World Englishes: Volume 2: Ideologies, edited by Rani Rubdy, and Ruanni Tupas, 9–26. London: Bloomsbury.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2022. “Critical Applied Linguistics in the 2020s.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 19 (1): 1–21.

- Petrovic, John E., and Bedrettin Yazan. 2021. “Language as Instrument, Resource, and Maybe Capital, but not Commodity.” In The Commodification of Language: Conceptual Concerns and Empirical Manifestations, edited by John E. Petrovic, and Bedrettin Yazan, 24–40. London: Routledge.

- Scollon, R., and S. W. Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. London: Routledge.

- Sharma, Bal Krishna. 2021. “The Scarf, Language, and Other Semiotic Assemblages in the Formation of a New Chinatown.” Applied Linguistics Review 12 (1): 65–91.

- Simpson, William, and John O’Regan. 2018. “Fetishism and the Language Commodity: A Materialist Critique.” Language Sciences 70: 155–166.

- Tsing, Anna. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Van Treeck, Bernhard. 2003. “Styles – Typografie als Mittel zur Identitätsbildung.” In HipHop: Globale Kultur – Lokale Praktiken, edited by Jannis Androutsopoulos, 102–110. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.