ABSTRACT

Since the mid-1980s, “experience” has become a central object of reflection for marketing as well as for semiotics, to the extent that meaning is always created during an experience. However, English and French literatures on experiential marketing often approach the concept of experience differently. This article argues that these divergences concern the thematic of the experience (i.e. shopping vs consuming), and that, more essentially, experience should be conceived as the common denominator of all marketing offerings, no matter if it is a product, a service, an event, a place … Using the post-structural semiotic frameworks of the “interactional regimes” theory, the author proposes to consider four fundamental consumer experiences (domination, cooperation, emancipation, and harmonization), each of these related to the logic of a specific type of offering: “goods,” “play,” “work” and “existence.” In considering these four macro-offerings, this paper aims to better grasp the interactional and semiotic stakes of consumer experiences.

Introduction

Postmodern consumption – which has been conceived at some point as a re-enchantment of everyday life (e.g. Badot and Cova Citation1992; Firat and Venkatesh Citation1995; Ritzer Citation1999) – can appear paradoxical: communication emphasizes eating well, while at the same time supermarkets’ shelves continue to display countless industrial and caloric products; companies encourage sustainable development, then consumers are invited to take a plane, at knock-down prices, to discover destinations that are both exceptional and trivialized. When we take a closer look, however, these paradoxes turn out to be rather superficial: they ultimately reveal the hold individualism has on the way postmodern societies function (e.g. Martucelli Citation1999; Lipovetsky Citation2006). Moreover, they show that companies are keen to exploit all possible means to reach their public targets and marketing objectives.

On the other hand, there is a more subtle paradox, able to be grasped within the combined theoretical frameworks of marketing and semiotics: the outward paradox of marketing of experiences (or experiential marketing), which is often presented as a specific and typically postmodern marketing approach, wherein everything in life – including consumption practices – is an experience as outlined by Filser (Citation2002) or Carù and Cova (Citation2003).

The expression “experiential marketing” was coined after Holbrook and Hirschman (Citation1982) explicitly linked experience and marketing in the 1980s, and it gained notoriety throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The most emblematic references which have led this concept to success were then Arnould and Price's article, “River Magic: Extraordinary Experience” (Citation1993), Holt’s paper, “How Consumers Consume” (Citation1995), Schmitt's book, Experiential Marketing (Citation1999), and Pine and Gilmore's work, The Experience Economy (Citation1999). On the French side of the research, this concept also raised a lot of contributions among which Filser’s paper, “Le marketing de la production d’expériences” (Citation2002), Hetzel's book, Planète conso. Marketing expérientiel et nouveaux univers de consommation (Citation2002), Carù and Cova’s article, “Expériences de consommation et marketing expérientiel” (Citation2006a), and more recently Roederer and Filser’s book, Le marketing expérientiel. Vers un marketing de la co-création (Citation2015).

While scientific literature on experiential marketing is already thorough and vast (e.g. Antéblian, Filser, and Roederer Citation2013; Schmitt and Zarantonello Citation2013), this article pursues two concomitant objectives within the semiotic field in order to offer a renewed semiotic conceptualization of “experience” within marketing theory, as well as to demonstrate the significance of semiotics for some marketing reflections. The first objective of this article is to consider whether there is a need to distinguish between the expressions “experiential marketing” and “marketing of experiences” by exploring the use of these terms in foundational American and French writings. It goes without saying that this effort to clarify terminology has already been carried out by several authors, as we shall see. Thus, the intention of this first part is not so much to challenge the existing state-of-the-art as to bring this matter to the attention of semioticians, even to remind it to specialists who already know about it. For this reason, this first part functions more as a mainstream introduction designed to prepare the ground for the second objective, which deals with the real stake of this study.

Specifically, the second objective is to develop a semiotic categorization of marketing offerings placing experience at the center of all stakes, thereby making “experiences” not just a particular offering, but the foundation for conceptualizing all possible offerings. Through the (post-)structuralFootnote1 approach inherited from Greimas (e.g. Citation1969, Citation1983) and the Paris School Semiotics, this article proposes to consider four macro-categories of offerings – goods, play, work, and existence – each one of them corresponding to one of the four “interactional regimes” theorized by French semiotician Eric Landowski (Citation2005): manipulation (i.e. domination), programming (i.e. cooperation), assent (i.e. emancipation) and adjustment (i.e. harmonization). Uncovering these macro-categories should help marketers better understand the relationship brand offerings tie with customers-consumers. In addition, this paper contributes to semiotics by confirming the heuristic validity of the “interactional regime” theory for the study of any type of social activity.

In brief, following the metaphor proposed by Deborah J. MacInnis in her article aiming at establishing “A Framework for Conceptual Contributions in Marketing” (Citation2011, 138), the approach will be similar to that of a “cartographer,” since this article will requestion with a semiotic “telescope” some marketing management propositions, so as to draw on an original “mapping” of consumer experience.

Consumer experience

A marketing offering or a form of communication?

In Kotler et al.’s handbook Marketing Management (Citation2019, 6, 290), “experiences” are presented as immersions in places entirely designed and semiotized by brands. Examples of these are theme parks (Disneyland-Paris), points of sale (Niketowns, Apple Stores, Nespresso boutiques), as well as entertainment places (concert halls, movie theaters, sports arenas). This inventory, albeit brief, is sufficient to identify two salient and independent criteria that distinguish “experiences” among them: the environmental relationship and the value of experience.

With regard to the “environmental relationship” (Pine and Gilmore Citation1999, 30), the above examples make it possible to grasp the experience in two ways: first, in terms of a visit, with a moving individual around whom a whole series of objects gravitates and which immerses him in a sensory-rich universe (theme parks, points of sale); second, in terms of a show, with a rather static individual who focuses his attention on a surrounding environment which becomes, by its power of attraction, a horizon of reference (concert halls, movie theaters). Thus, on the one hand, we have experiences in which the surroundings target the individual and, on the other hand, experiences in which it is the individual who targets the surroundings. However, reality is of course always complex, and these are rather slight mixes and variations that are at stake. In Disneyland-Paris, for example, when we wander through the alleys of the park, we undoubtedly enjoy sites, rides and attractions (targeted), but we also contemplate various shows at every street corner (targeting); and, conversely, in a movie theater, we are undeniably glued to a screen (targeting), but we also live a journey by experiencing a multitude of sensations through the sound effects that burst from the powerful speakers that shake our seat (targeted).

As for the value of experience, we also have two trends: on the one hand, we have monetized experiences, which can therefore only be lived through a money transaction (as in Disney parks or in movie theaters), and, on the other hand, we have free experiences, which intentionally aim to trigger acts of purchase by setting up aesthetic atmospheres and ambiances (as in Niketowns or Apple Stores). So, while the experience is at once that of the promised offering (the object of the transaction), it is also only one form of communication among others aimed at provoking direct or indirect purchases, by creating affinity or reinforcing loyalty (Grewal, Levy, and Kumar Citation2009). Likewise, the distinction between monetized and free experiences is not dual or radical, but gradual and continuous. This is particularly noticeable in Disney parks, where we are constantly invited to spend money: for souvenirs, toys, food, etc. In this sense, an experience in such a place must be conceived as an experience of both an amusement park (a consumption experience) and a giant open-air point of sale (a moment of purchase). As we will see, it is this criterion of the value of experience that is particularly significant for understanding the principle of experiential marketing.

Experience everywhere

In the practice of marketing, we tend to forget that everything in life is experience. In Pine and Gilmore’s founding book on Experience Economy (Citation1999), we get that every activity and offering can become an object of reflection for experiential marketing. In addition to monetized immersive experiences and free experiences at points of sale, this type of marketing reveals to also include the experience of using products, as well as the experience of encountering communication about brands (e.g. advertising, product placement, word of mouth, etc.) Thus, all consumption practices and daily activities can pass under the microscope of experiential marketers – whether it be sitting on an IKEA couch, snacking on Doritos between meals, or facing a Coca-Cola billboard in the street – and it is this very reason that makes it hard to defend the position that experiential marketing manifests a trend of postmodernity – as Gilles Marion noticed in the mid-2000s when arguing that it is not so much the expectations and attitudes of consumers that have changed, but the “glasses” used by the marketers, who suddenly were discovering a reality that had always existed (Citation2003). In other words, if the marketing of experiences proves to be applicable to any kind of offerings – whether “goods” (the experience of drinking a coffee at home made with a Nespresso machine) or “services” (the experience of having a coffee served in a Nespresso boutique) – we should consider whether we are truly dealing with a new kind of marketing, or if an offering is simply experiential by nature. While this is not a new question – Carù and Cova were already raising it in Revisiting Consumer Experience (Citation2003) – it is a question worth seriously considering.

Actually, if we accept that everything in life is an experience, and that marketers ultimately offer and study experiences, we should next unpack our key concept: is “experiential marketing” a form of communication (like direct marketing) or a very specific offering (like a good or a service)?

The contours of the experience

Among numerous offerings

To get a mainstream picture of how marketing professionals are invited to conceive experience, let’s refer to Kotler et al.’s Marketing Management (Citation2019, 6–8) where ten categories of offerings are listed with the following examples:

“Goods”: food products, clothing, furniture, shampoos, cosmetics, perfumes, cars, computers, telephones, game consoles.

“Services”: transportation, banking, hotels, hairdressing, sports clubs, many liberal professions like lawyers, doctors, consultants.

“Events”: global sporting events (the World Cup, the Olympics), farmer’s markets, trade shows, artistic performances.

“Experiences”: services and goods put together to create, stage, and market experiences.

“Persons”: artists, musicians, CEOs.

“Places”: cities, regions, countries.

“Properties”: material property (real estate) or financial property (stocks and bonds).

“Organizations”: museums, corporations, nonprofits, universities, public schools.

“Information”: what books, schools, and universities produce and distribute to parents, students, and communities.

“Ideas”: encouraging people to sort their waste, discouraging drinking alcohol before driving, fighting obesity.

So, the marketing of “experiences” (category 4) is complex, because how can we deny or ignore that participating in an “event” (3) is also living an experience, as is visiting a “place” (6) or benefiting from an “organization” (8). Actually, it is worth remembering that a need or a desire can only be satisfied in an act of consumption, that is, during an experience. This means that there are no offerings that fill a need or a desire outside the time of the experience. For example, when we use a toothbrush and toothpaste, we live an experience by using “goods” (category 1); similarly, when we take the plane or the train, we live an experience by using a “service” (2). In conceptualizing consumption and experience in these ways, we can see why it may be risky to speak of experience to qualify a specific offering as well as a form of communication. We might then challenge the vocabulary of the experience.

Words and realities

If we consider experiential marketing to be a form of communication, we understand that we are facing a classic branding approach. Indeed, for companies, the idea is to use various methods – mainly visual, but also olfactory and auditory – to semiotize their points of contact with potential clients (stores, outlets, stands, etc.). In doing so, this form of experiential marketing covers – more or less – what is commonly known as retail merchandising. “More or less,” because this form of communication has two specificities: first, this communication aims to stimulate all sensory modalities; second, it not only offers an environment, but also unfolds a scenario through various activities and script-writings (Filser Citation2002).

For French authors, this effort to semiotize the “experiential context” (Carù and Cova Citation2006b; Roederer and Filser Citation2015) surrounding the activity of shopping is the purpose of experiential marketing. For them, experiential marketing is mainly a practice aimed at enchanting or re-enchanting shopping experiences (Hetzel Citation2002; Boutaud Citation2007; Antéblian, Filser, and Roederer Citation2013). In contrast, for American authors, experiential marketing describes a specific offering, which takes its value from the fact of delivering an extraordinary consumption experience. It can be – as in Arnould and Price's research (Citation1993) – a wild experience, even if supervised, such as the descent of rapids; it can also be – as Pine and Gilmore (Citation1999) show – a more general process of enriching the experience of a good or a service, as in a Starbucks coffee shop, where what the customer experiences (and pays for) is a global apparatus that depends on both the coffee (a good) and the activity of the staff behind the counter (a service).

Ambiguity surrounding this concept of experience in marketing literature – at least from a Francophone point of view – seems then to be linked to a problem of translation: the English term “experiential marketing” is not equivalent to the French “marketing expérientiel.” The English concept is richer and broader: it names those specific offerings that deliver a moment of escapism, a source of strong emotions afforded by strategies that provide paradoxical impressions of unreality and hyperrealism (i.e. it is an “extra-ordinary” experience that delivers an excessively vivid reality), that draws value from forcing the visitor to take on new roles (such as that of the intrepid adventurer in the Indiana Jones Adventures rides of the Disney parks).

The drivers of the experience

A quest for meaning

The different meanings of experiential marketing impede an easy critique. Experiential marketing has been treated as both a form of communication for the sale of products and the development of a loyalty, and as a marketing offering intended to impact the consumer through a semiotized and scripted experience in stylized contexts. Moreover, the term experiential can introduce confusion, since everything we live, at every moment, is an experience.

Nevertheless, if we want to open up new perspectives, we must concede that the field of possibilities in postmodern societies is more open than in the past and that, as a result, individuals no longer tend to look for a ready-made meaning in their activities (e.g. Jameson Citation1989; Semprini Citation2003; Featherstone Citation2007); they are more interested in discovering new meaning, so as to discover new facets of their identity, without being tied to a determinate tradition. From a marketing point of view, this new paradigm can be understood as a desire to no longer buy offerings that have a specific use, but rather offerings that can bring a certain freedom and creativity (Marion Citation2016). Thus, what has emerged within contemporary consumption, and which would mark its postmodern quality, is a form of curiosity: consumers are not satisfied anymore with just using goods, nor with just letting a provider carry on a service; they also want to participate in the process of creation of value, to live “sticky journeys” (Siebert et al. Citation2020) – above all – to feel these offerings and to be surprised when they experience them, showing a certain openness towards them (e.g. Semprini Citation2007).

However, while real, this tendency is not a reason enough to acknowledge the existence of a new category of offerings (the “experience” category). Rather, it is all the existing offerings – if they are well conceived – that can claim to renew the meaning of our practices, even of our lives. For example, a company can sell chocolate with a cheese taste or propose international money transfers without a banking intermediary, but in both cases (no matter how great the idea or the experience may be) we remain in the field of the traditional offerings, respectively, those of goods (chocolate) and services (money transfer).

Lastly, this discussion about experience allows for a structural way of categorizing the marketing offerings. Indeed, if we acknowledge that the primary characteristic of an experience is – from a semiotic point of view – its “interactional regime” (Landowski Citation2004, Citation2005), it becomes possible to envisage a categorization of the offerings organized around the way customers-consumers have (or don’t have) control over their experience.

Control at stake

In our everyday life, we tend to want to dominate our environment. In the context of consumption, this tendency to control the course of the action is exercised towards what we use to call “goods”; that is, objects that we possess and can manipulate: food, instruments, clothes, tools, cars, and houses, are all goods. They are offerings that require being taken charge of by the consumer to function for the purpose they are made for. With goods, consumers can thus have total domination on the situation, even if this domination is conditioned by their ability to know how to bend these objects to their will (Landowski Citation2012): for example, a piano requires a sensitive user to deliver all its potential.

For this first case, one might speak of power rather than domination. Indeed, dominating an object means exerting power over it. But the term “power” is complex. Power can also entail imprisonment; an experience of power may include reverse domination: a situation where the consumer and the offering have a hold on each other, where the consumer must surrender to the offering to make it function optimally. In this case, the power that the individual can exercise is that of decision rather than domination: the decision of accepting or rejecting the domination of the system-offering: the decision to collaborate or to rebel, so as to follow the program scripted for the individual.

This new interactional regime, which we can call cooperation, thus implies that a dominating system needs submissive-collaborative individuals to exist and to function. In the context of consumption, the kind of offering that configures the actions of the consumers could then be conceived in terms of “play”: play as a game (with rules imposed by the offering), play as a staging (implemented by the offering), play as recreation (where the consumer follows what there is to do), play as interaction (with other people), and play as performance (of a scenario).

Private places, public transport, and even some liberal professions such as doctors or dentists propose this kind of offering that firstly requires the presence and cooperation of the consumer-customer (or patient) and secondly programs and directs the course of the action by imposing more or less rigid paths and protocols. In this way, we understand that a play captures the consumer-customer in an experience where his room to maneuver is greatly reduced. In an airport or an airplane, what is allowed is framed and restricted. In front of a television program, we are even more captive: we have no means of influencing the course of the broadcast; even if we turn off the television, we only have control over the television-object, not over the program that continues to be transmitted on the channel.

With these examples, we understand that it is thus the “play” that structures everything, that guides the consumer-customer – taking him by the hand or by the feelings, meeting his expectations and needs so that he can be fully conciliatory and willing to cooperate. However, this reversal of roles should not be seen as dramatic or alienating (even if it sometimes comes close). While the consumer-customer does not dominate the situation, pleasure is not consubstantial with domination. Domination implies responsibilities, causes concerns, and requires significant efforts. It is a heavy burden that can be relieved by reliance on ready-made systems. Thus, one might prefer going to a restaurant over wasting an hour preparing food, or taking the train instead of driving ten hours to the seaside.

As we can see, this second type of offering often applies to what we also commonly call services. However, we must distinguish between two types of services: (a) services of this kind, which hold the consumer captive, because they require the presence of the individual in order to achieve the desired result, and (b) services which, conversely, liberate the individual by offering to do something for him without his presence being required (in order to save him time and effort, or because he simply lacks the skills). One could thus say that with play, it is the consumer-customer in all his being – physical and psychic – that is managed. On the other hand, with what might call “work,” it is his activity that is managed.

In detail, this term “work” must be understood in its double and general sense: as both an activity and as the result of this activity. This means that “work” refers to all types of activity carried out by agents or agencies (that is, autonomous actors, usually individuals, but sometimes also empowered systems). These offerings are therefore products of a mandate ordered by the “consumer,” who now has rather the status of a “customer” since he neither touches nor uses anything, but only communicates what needs to be done with the provider. With work, we are thus no longer in a domination-manipulation nor cooperation-programming relation or interaction, but in an order of mission with a totally liberated client: rather than hold or control, there is renunciation-abandoning. Indeed, by giving his assent, the client sets himself free; he gives up, and consequently also leaves the agent – or the agency – free to carry out the assigned mandate. It is then a mutual emancipation-empowerment. Traditionally, the activities of banks and insurance companies belong to this third category of offerings; they exempt their clients from any management and allow them, by this very fact, to dedicate time to other occupations.

Finally, alongside these three offerings, we encounter one last sort that accounts for situations where there are no holds on either side. This fourth specific case occurs, for example, with destinations and pets. As distinct as these two offerings may seem, they both propose something that does not guarantee any certain result, and therefore no peace of mind (unlike works, which offer an absolute let-go.) In this sense, the particularity of this last category is to offer no promise, except that of the event and of the surprise. In other words, the only thing that this category ensures is to be shaken, astonished, disconcerted, moved, fascinated, or relieved at certain moments of the consumption experience (though the term consumption is not really appropriate, since we are no longer consuming, only sharing and living). In short, the promise of this fourth offering is pure emotion and sensations of all kinds. For example, when we go to explore a country in a slightly curious and open-minded way, we expect the unexpected, we assume going on an adventure. In the same way, if we cherish animals and decide to adopt a cat or a dog, we hope for a re-enchantment of our daily life, because we can foresee that this adoption will lead to magical, playful, and surprising moments.

These offerings that throw us into the unknown, whose allure lies precisely in this uncertainty that forces us to rely on our sensitive intelligence, can be conceived as “existence.” This term qualifies offerings consisting of living systems, whether they are places (ecosystems), bodies (organisms), or systems that are sold or appraised as such. For this reason, the relationship that the sympathetic “consumer” develops with these entities is that of a partnership or an attunement-harmonization. Indeed, the experience of an existence differs from that of a play in the sense that it does not imprison the individual in a program of actions. On the contrary, it offers him a horizon of action, leading him to deal with himself, by drawing on his semiotic resources. And in the same way, the experience of existence, in contrast to that of goods, cannot be subject to any manipulation: as it is a matter of doing with living systems (or objects not considered as objects), it is constant adjustments that are necessary to operate to have a satisfactory ending.

Structuring the offerings

In search of the relevant criterion

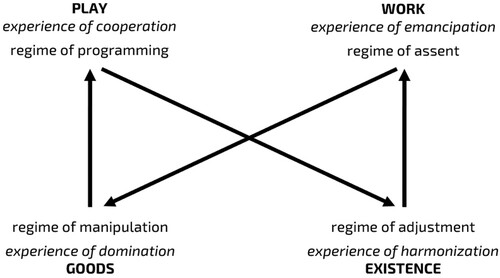

These four types of offerings can be associated to the four “interactional regimes” theorized by Landowski (Citation2005) in the framework of his socio-semiotics: manipulation (“domination over goods”), programming (“cooperation in play”), adjustment (“harmonization with existence”), assent (“emancipation from work”). The semiotic square below illustrates these correspondences and the relationships between these terms. It allows a first grasp of the way each functions ().

This semiotic square gives an account of how “control” is managed in experiences of various kinds. But what this figure also illustrates is that experiences can be analyzed from the perspective of criteria other than “control.” In fact, it is crucial to note that a semiotic square is always structured around three types of relationships (diagonal, horizontal, and vertical), and that each relationship refers to a specific criterion. Essentially, it is always the criteria constituting the vertical relationships that must be considered as primary (Perusset Citation2022, Citation2023), because they link complementary terms. That explains why we have, on the left of the square, offerings that permit a certain control (“play” and “goods”) and, on its right, offerings that impede any control (“work” and “existence”). Consequently, we understand that the two other criteria – that of the “involvement” (for the terms linked diagonally) and that of the “effort” (for the terms connected horizontally) – are secondary. These three criteria are detailed below with graphic standards from interpretative semantics (Rastier Citation2009):

- //control//: experience of a /procedure/ (with “play” and “goods”) vs. experience of an /adventure/ (with “existence” and “work”).

- //effort//: experience of a /service/ (with “play” and “work”) vs. experience of an /exercise/ (with “goods” and “existence”).

- //involvement//: experience of a /cooperation/ (with “play” and “existence”) vs. experience of a /coordination/ (with “goods” and “work”).

Now, one may wonder if “control” is really the most appropriate criterion when analyzing a (consumer) experience. If the rule is to select the criterion that makes the most sense as the main criterion (Rastier Citation2009; Perusset Citation2022, Citation2023), the criterion of “effort” might seem more appropriate. Indeed, the criterion of “effort” in the analysis of an experience closely parallels economists’ early distinction between “services” and “products”; that is, between offerings that exempt consumers from effort (services) and offerings that require them to expend effort (products).

Lastly, regarding this distinction between services and products, it might be preferable to speak about “exercises” rather than “products.” Indeed, it is important to underline that a service is an activity (a “situation-practice”) whereas a product, in the sense of a “good,” is an object (a “body-actant”) (Fontanille Citation2008, 20–24; Perusset Citation2020a, Citation2020b). With the term exercise, this non-congruence is thus neutralized. At the same time, the opposition to service is made more significant, because this notion of exercise effectively evokes an activity that requires a consumer making efforts to demonstrate full mastery in the use of the product.

Refining the analysis

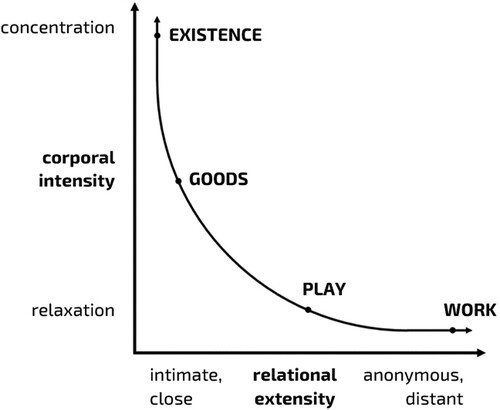

Now that we have identified the relevant criterion for the analysis, we can consider which of the four offerings requires the greatest effort on the part of the consumer. For that, we must tackle the question of the “tensivity” of the category (Zilberberg Citation2006). Indeed, between the four unveiled categories of offerings, there are gradual intervals or tensions that are at stake. This means that these offerings reveal their value through the degree of effort they require from the consumer: existence demands a lot of efforts and goods require less, while play relaxes and work gives even more peace of mind. The following tensive diagram illustrates this ().

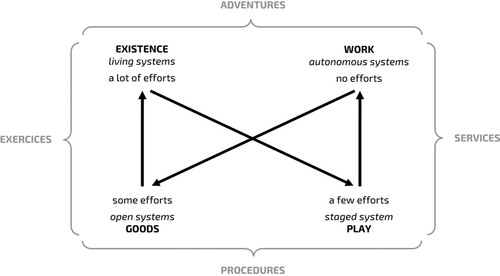

This semiotic model allows us to distribute these offerings in a rearranged semiotic square. Indeed, the new model figured below shows that it is ultimately “effort” that is at stake at all degrees, and that these offerings are “systems” of differing complexity requiring different degrees of effort from the consumer ().

Lastly, we can complete the analysis by uncovering the “semic molecules” (Rastier Citation2009) of each offering; that is, their minimal and structural meaning. We have transcribed these semantic sequences below, indicating first their “generic semes” (what they have in common, namely to be /offerings/), then their “specific semes” (the aspects that differentiate them: first the kind of effort, then the kind of control):

- existence: /offering/ + /exercise type/ + /difficulty to have control/

- goods: /offering/ + /exercise type/ + / possibility to have control/

- play: /offering/ + /service type/ + / possibility to have control/

- work: /offering/ + /service type/ + /difficulty to have control/

Conclusion

The validity of the “interactional regimes” theory

The terms we have discussed in this paper (goods, play, work, existence) are not intended to compete with terms already widespread in common language (e.g. services, events, places, etc.). Instead, these four terms are situated at another level of relevance: they super-order the classical offerings, just as the zoological families (felines, canines …) super-order the species we are used to living with or know by name (dogs, cats, lions, wolves …). In this sense, this article aims to extend categorical abstraction in order to create a matrix capable of hosting any conceivable marketing offering. For example, the list below distributes the offerings listed in Marketing Management (Kotler et al. Citation2019) into these four categories:

Goods: “goods” (a shampoo), “proprieties” (a house).

Play: “services” (a hairdresser), “events” (a football game, in the stadium or on television), “experiences” (an amusement park), “persons” (a singer, on the radio or in concert), “organizations” (a museum), “information” (the content of a newspaper), “ideas” (the content of an advertising).

Existence: “goods” (a pet), “places” (a region), “organizations” (the office where we work).

Work: “services” (a lawyer), “persons” (a painter who promotes a vision of the world with his art), “organizations” (an association), “ideas” (an association helping homeless people).

As we can see, this list reveals that the category of “play” corresponds to the phenomenon of “experiential marketing” introduced in the first part of this article. This observation helps us to understand what lies at the heart of the “experiential marketing”: a dynamic of cooperation and hence of half-control, since the experience is programmed by the company, but carried out (mostly) by the client-consumer.

Furthermore, this article recalls that semiotics remains a discipline of choice when there is a need to model complex questions – such as those about the nature of experience – in a synthetic and relevant way. In this respect, this study follows recent work in socio-semiotics (e.g. Demuru Citation2020; Petitimbert Citation2021) in corroborating the heuristics of the “interactional regimes” (see Landowski Citation2021 for an up-to-date review of work on this theory). While the meaning of these regimes (manipulation, programming, adjustment, assent) has been widely analyzed as involving “signification,” “insignificance,” “sense,” and “nonsense” (Landowski Citation2005), this article expands “interactional regimes” theory by identifying and naming the emblematic interactants (goods, plays, existences and works) of each of these regimes from the perspective of marketing.

Practical perspectives

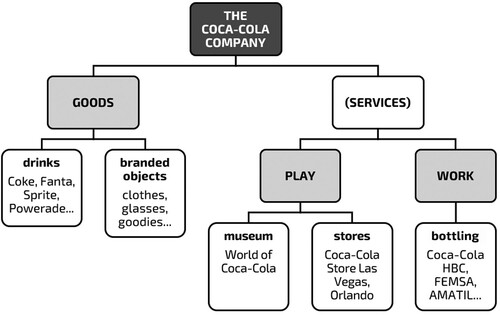

Semiotics must not only be a theoretical discussion, but also a practical solution. This system of four offerings could help marketing professionals to establish brand portfolios with solid foundations. As companies often have different types of offerings, it is important to mark these distinctions as soon as possible in the “strategic portfolio” (Aaker Citation2004). For example, the Coca-Cola Company not only sells all kinds of beverages (Coke, Fanta, Sprite, Minute Maid, Powerade …); it also operates as a bottler and has a museum in Atlanta as well as specialty stores in Orlando and Las Vegas. So, a good brand portfolio might start by separating the offerings according to the type of experience they deliver to the client. In the case of the Coca-Cola Company, we would then have three macro offerings: the beverages as “goods”; the museum and stores as “play,” and the bottling as “work” ().

Beverages are offerings that the consumer can manipulate or choose to use when needed. In the case of the museum and the stores, however, the consumer must conform to specific scenarios and rigid environments that impose a succession of actions: the very essence of “play,” which we have seen is commonly linked to “experiential marketing.” With bottling, the Coca-Cola Company offers “work”: the firm makes, by virtue of its know-how, what other companies do not master, that is, the company carries out this bottling work for its own products, but also as part of business-to-business (BtoB) partnerships with organizations all over the world (thanks to subsidiaries like the European market’s Coca-Cola HBC, or the Oceanic market’s Coca-Cola Amantil).

So, while the Coca-Cola Company is widely considered to be a corporation that primarily sells beverages (“goods”), we should not forget that its business is also largely based on BtoB bottling solutions (“work”). Its museum in Atlanta and stores in Las Vegas and Orlando (“play”) can, on the other hand, be considered as diversifications – satellite activities – similar to goodies, merchandizing, and souvenirs; they are ways of making extra money easily, without being a core business.

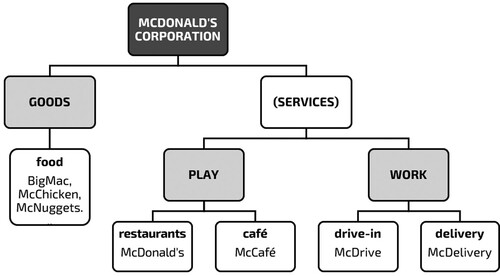

To sum up, the present theoretical proposal could be used to produce an overview of the business of any company. Indeed, we could do the same demonstration with McDonald’s by observing that if the core business of the firm is based on its thousands of eponymous restaurants and McCafés (“play”) all around the world, the company also remains a point of reference in the field of alimentary products (“goods”) – with the Big Mac, the McChicken, and the McNuggets – plus does not hesitate to develop new “work”: before the onset of the COVID pandemic, we had the McDrive for takeaway; afterwards, we had McDelivery to get our meals to the door ().

To conclude, one might note the absence of “existence” offerings in both examples; it is because companies tend not to develop such business. We believe there are two important reasons for this: first, “existence” is a complex offering that involves living systems (people, biotopes, etc.), that require constant care, attention, time, and money, which may not be profitable for a company; secondly, because of their organic character, “existences” are inherently unpredictable. For an organization, managing an unpredictable offering is risky, because it precludes ensuring a clear benefit to the consumer. In other words, “existence” can create dissatisfaction, cause client attrition, and lead to financial difficulties.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Promise McEntire (Departments of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Michigan) for her helpful comments and proofreading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “Post”, because the semiotic propositions developed from the 1990s by the Paris School Semiotics enrich Greimas’ structural semantics by considering the situational and sensitive dimensions of meaning.

References

- Aaker, David A. 2004. Brand Portfolio Strategy. New York: Free Press.

- Antéblian, Blandine, Marc Filser, and Claire Roederer. 2013. “L’expérience du consommateur dans le commerce de detail.” Recherche et Applications en Marketing 28 (3): 84–113. doi:10.1177/0767370113497868.

- Arnould, Eric J., and Linda L. Price. 1993. “River Magic. Extraordinary Experience and the Extended Service Encounter.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (1): 24–45. doi:10.1086/209331.

- Badot, Olivier, and Bernard Cova. 1992. Néo-marketing. Paris: ESF.

- Boutaud, Jean-Jacques. 2007. “Du sens, des sens. Sémiotique, marketing et communication en terrain sensible.” Semen 23: 1–15. doi:10.4000/semen.5011.

- Carù, Antonella, and Bernard Cova. 2003. “Revisiting Consumption Experience. A More Humble but Complete View of the Concept.” Marketing Theory 3 (2): 267–286. doi:10.1177/14705931030032004.

- Carù, Antonella, and Bernard Cova. 2006a. “Expériences de consommation et marketing expérientiel.” Revue française de gestion 162 (3): 99–113. doi:10.3166/rfg.162.99-115.

- Carù, Antonella, and Bernard Cova. 2006b. “Expériences de marque: comment favoriser l’immersion du consommateur?” Décisions Marketing 41: 43–52. doi:10.7193/DM.041.43.52.

- Demuru, Paolo. 2020. “Between Accidents and Explosions: Indeterminacy and Aesthesia in the Becoming of History.” Bakhtiniana 15 (1): 83–109. doi:10.1590/2176-457342629.

- Featherstone, Mike. 2007. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Filser, Marc. 2002. “Le marketing de la production d’expérience.” Décisions Marketing 28 (4): 13–21. doi:10.7193/DM.028.13.22.

- Firat, A. Fuat, and Alladi Venkatesh. 1995. “Liberatory Postmodernism and the Reenchantment of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 22 (3): 239–267. doi:10.1086/209448.

- Fontanille, Jacques. 2008. Pratiques sémiotiques. Paris: PUF.

- Greimas, Algirdas J. 1969. Sémantique structurale. Paris: PUF.

- Greimas, Algirdas J. 1983. Du sens II. Paris: Seuil.

- Grewal, Dhruv, Michael Levy, and Vineeth Kumar. 2009. “Customer Experience Management in Retailing.” Journal of Retailing 85 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2009.01.001.

- Hetzel, Patrick. 2002. Planète conso. Marketing expérientiel et nouveaux univers de consommation. Paris: Éditions d’Organisation.

- Holbrook, Morris B., and Elizabeth C. Hirschman. 1982. “The Experiential Aspects of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 9 (2): 132–140. doi:10.1086/208906.

- Holt, Douglas B. 1995. “How Consumer Consumes. A Typology of Consumer Practices.” Journal of Consumer Research 22: 1–16. doi:10.1086/209431.

- Jameson, Frederic. 1989. Postmodernism. Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Washington, DC: Maisonneuve Press.

- Kotler, Philip, Kevin L. Keller, Delphine Manceau, and Aurélie Hemonnet. 2019. Marketing Management. 16th ed. Paris: Pearson.

- Landowski, Eric. 2004. Passions sans nom. Limoges: PULIM.

- Landowski, Eric. 2005. Les interactions risquées. Limoges: PULIM.

- Landowski, Eric. 2012. “Voiture et peinture. De l’utilisation à la pratique.” Galaxia 24: 241–254.

- Landowski, Eric. 2021. “Complexifications interactionnelles.” Acta Semiotica 2: 41–61. doi:10.23925/2763-700X.2021n2.56786.

- Lipovetsky, Gilles. 2006. Le Bonheur paradoxal. Essai sur la société d'hyperconsommation. Paris: Gallimard.

- MacInnis, Deborah J. 2011. “A Framework for Conceptual Contributions in Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 75 (4): 136–154. doi:10.1509/jmkg.75.4.136.

- Marion, Gilles. 2003. “Le marketing ‘expérientiel’: Une nouvelle étape ? Non de nouvelles lunettes.” Décisions Marketing 30: 87–91. doi:10.7193/DM.030.87.91.

- Marion, Gilles. 2016. Le consommateur coproducteur de valeur. Cormelles-le- Royal: EMS.

- Martucelli, Danilo. 1999. Sociologies de la modernité. L'itinéraire du XXe siècle. Paris: Gallimard.

- Perusset, Alain. 2020a. Sémiotique des formes de vie. Monde de sens, manières d’être. Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Supérieur.

- Perusset, Alain. 2020b. “Les métamorphoses de l’objet. Aperçu d’une sémiotique des corps-actants.” Actes Sémiotiques 123: 1–21. doi:10.25965/as.6507.

- Perusset, Alain. 2022. “Éléments de sémiotique catégorielle.” Actes Sémiotiques 126: 185–201. doi:10.25965/as.7443.

- Perusset, Alain. 2023. “How Post-Structural Semiotics Can Model Categories: From Greimasian Semantics to Categorial Semiotics.” Signata. To be Published.

- Petitimbert, Jean-Paul. 2021. “The Value of Emptiness: MUJI’s Strategies.” Acta Semiotica 1: 67–85. doi:10.23925/2763-700X.2021n1.54155.

- Pine, Joseph B., and James H. Gilmore. 1999. The Experience Economy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Rastier, François. 2009. Sémantique interprétative. 3rd ed. Paris: PUF.

- Ritzer, George. 1999. Enchanting a Disenchanted World. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

- Roederer, Claire, and Marc Filser. 2015. Le marketing expérientiel. Vers un marketing de la cocreation. Paris: Vuibert.

- Schmitt, Bernd. 1999. Experiential Marketing. New York: The Free Press.

- Schmitt, Bernd, and Lia Zarantonello. 2013. “Consumer Experience and Experiential Marketing: A Critical Review.” Review of Marketing Research 10: 25–61. doi:10.1108/S1548-6435(2013)0000010006.

- Semprini, Andrea. 2003. La société de flux. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Semprini, Andrea. 2007. La marque, une puissance fragile. Paris: Vuibert.

- Siebert, Anton, Ahir Gopaldas, Andrew Lindridge, and Claudia Simoes. 2020. “Customer Experience Journeys: Loyalty Loops Versus Involvement Spirals.” Journal of Marketing 84 (4): 45–66. doi:10.1177/0022242920920262.

- Zilberberg, Claude. 2006. Éléments de grammaire tensive. Limoges: PULIM.