Abstract

Background

The overseas applicant’s capability of practising safely and effectively is proven through the tests of competence which consist of computer-based tests and the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE). All prospective applicants to the Nursing and Midwiferey Council (NMC) register must be able to demonstrate that their skills, knowledge and behaviours are at the level required to meet the NMC preregistration nursing or midwifery standards for the United Kingdom (UK).

Aim

The aim of this review is to explore the challenges faced whilst undertaking these tests of competence, the OSCE, by overseas educated nurses who aspire for Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) registration in the UK.

Methods

A scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley (2005) framework was conducted to explore and produce a profile of the existing literature on the registration requirements of the NMC. A search of CINAHL, Medline and Scopus resulted in 150 records, which were then screened against the inclusion criteria – English Language, publication between 2015 onwards and discussed the language tests/competency tests required for gaining entry to the NMC register. A total of nine articles met the criteria and are included in this scoping review. The PRISMA-ScR framework is used to present the review.

Results

There was a paucity of studies that addressed the experience of overseas nurses who faced the OSCE. An interpretative stance was adopted to formulate the themes which were: competence/practice disparity, arbitrary issues for failing, failure to capture the digital health agenda, financial implications, and consequences of failing the OSCE. The results raise concern whether the nurses from overseas are held to higher standards than those trained in the UK and whether the assessment process is realistic and not pedantic.

Conclusions

This scoping review demonstrates there is a lack of robust research evaluating the effectiveness of tests of competencies. The review indicates there is no due acknowledgement of the previous skills and knowledge of the overseas nurses. Future research should focus on exploring the feasibility of tests of competence and its role in the integration of the nursing workforce.

Impact statement

As demonstrated by this review, tests of competence should be realistic and not pedantic and in attempting to protect entry to the nursing register to safeguard the people we are caring for, we do not reject experienced, safe and able practitioners.

Plain language summary

Any overseas nurse who would like to gain entry to the Nursing and Midwifery Council Register would need to go through the tests of competence. Failing to pass these tests of competence, will result in not being able to work as a registered nurse. We have browsed through the literature to find out about the experience of overseas nurses whilst undertaking these tests.

We have scoped what the current state is and what more is needed to ease and smooth the process of gaining access to the register. The review revealed there is no due acknowledgement of the previous skills and knowledge of the overseas nurses. We found that there is a competence/practice disparity, and arbitrary reasons were given for failing the overseas nurse. By citing such reasons, there is a high risk we are rejecting experienced, safe and able practitioners. The results also raise concern whether the nurses from overseas are held to higher standards than those trained in the UK.

The review also suggests that more research is needed to check the feasibility of tests of competence and its role in the integration of the nursing workforce. It is a call to action for researchers to evaluate and review the effectiveness of these tests of competence. The reviewers urge the policymakers to ensure that the tests of competence and the assessment process are realistic and not pedantic.

Introduction

The National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom is grappling with a critical nursing workforce shortage, posing substantial challenges to healthcare delivery. Additionally, the attrition rates among nursing staff, influenced by factors like burnout and stress, exacerbate the shortage (Royal College of Nursing, Citation2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has further intensified the strain on the NHS nursing workforce. The unprecedented demands for healthcare services during the pandemic have highlighted pre-existing gaps and placed an overwhelming burden on an already stretched workforce (Royal College of Nursing, Citation2020).

Addressing the nursing workforce shortage necessitates strategic and collaborative efforts from policymakers, healthcare institutions, and educational providers. Initiatives focused on recruitment, retention, and professional development, along with increased investment in education and training programs, are imperative to mitigate the current crisis and build a resilient nursing workforce for the future (NHS England, Citation2021).

Nursing is a global industry and whilst differing education is seen globally, the culture of care is well defined. For many migrants (economic and political) they come complete with a nursing qualification and/or skills but to much frustration, this has been ignored and a rigid sequence of processes to gain registration has been put in place. On the surface, it seems that such downturns do not deter those overseas-educated nurses seeking employment in the NHS. But at a deeper level, there is a growing disquiet amongst these nurses – questions do arise in how holistically well-prepared these overseas nurses are to integrate with the host workforce. Without a doubt, the integration of the guest workforce is one of the critical factors that influences their job satisfaction and thereby the retention of both the host and guest workforces.

In writing this paper, the aim is simple – to review the challenges faced by overseas educated nurses – those already in the country (UK) and those seeking entry and who aspire for Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) registration. As such, the remit of the review is situated within the UK context – those seeking to enter the NMC register. We signpost to these ‘disquiets’ collated through a scoping review and propose a program to enable this workforce to gain their NMC registration whilst acknowledging their proficiency and expertise gained during their overseas training.

Background

In response to the call for the NMC's overseas registration policy to be more robust and to ensure the prime task of the regulator - that of safeguarding the public – the NMC announced a further review of overseas nurse registration in 2013. Despite reporting no cases of overseas nurses being fraudulently registered (Glasper, Citation2013), the NMC (Citation2014) after a period of general consultation – replaced the Overseas Nurse Adaptation programmes with a single process with competency tests at its core. The overseas applicant’s capability of practising safely and effectively is proven through the tests of competence which consist of two parts. Part 1 is a computer-based test, based on 120 multiple-choice questions; Part 2 is the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) which requires the candidate to undertake a simulated clinical experience related to practice which seeks to establish the candidate's skills in care planning, patient assessment and evaluation of outcomes of clinical intervention.

Apart from demonstrating they are capable of practising safely, the applicants must also demonstrate they command a level of English which is necessary for the safe and effective practice of nursing or midwifery in the United Kingdom (NMC Schedule 4 of the Order). The professional code (NMC, Citation2018) for all nurses and midwives has at its core patient safety and requires applicants to have the necessary knowledge of English (verbal, listening and written) to practice safely. NMC clarifies: ‘There is a difference between having a sufficient grasp of a language to cope with day to day living and having the professional communication skills that are required to assess, plan, deliver and evaluate care for a patient or client’ Allan & Westwood, Citation2015). The applicants therefore need to evidence recent achievement of the required score in reading, writing, listening and speaking in the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) or in one of the other English language tests accepted by the NMC. Since October 2020 onwards, NMC has started accepting the Occupation English Test (OET).

sets out the requirements:

Table 1. criteria to gain entry to the NMC register.

To apply for NMC registration (NMC, Citation2018), overseas candidates are required to:

Methods

A literature review involves meticulous analysis of scholarly works on a specific topic, systematically examining studies, articles, and books to unveil key themes, gaps, and trends in the existing body of knowledge. This contributes to the ongoing discourse within a field. This review adopts a scoping methodology, aiming to map the extent and characteristics of evidence on Tests of Competence part 2. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews are broader, offering a comprehensive overview of available evidence. Chosen for its suitability, a scoping review proves valuable in exploring the relatively new topic of the Test of Competence (less than 10 years since it was introduced). Additionally, scoping reviews inform policy and practice, providing stakeholders with synthesized evidence to make informed decisions, thereby enhancing the quality and effectiveness of interventions and strategies.

A scoping review using the Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005) framework was conducted to explore and produce a profile of the existing literature on the registration requirements of the NMC. As the purpose of a scoping review is not a synthesis of the literature (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005; Teare & Taks, Citation2019), an overview of the scope of the current literature is presented. The 5 stages of scoping review – the review question, identifying relevant studies, selecting the studies, charting the data and summarising the results were done, as well as the optional stage where consultation with eternal stakeholder (NMC) for additional sources was also conducted.

Electronic databases Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed and Scopus were searched for English language publications from 1 January 2015–31 January 2023 (The tests were introduced in 2014). The search words were used by combining words using Boolean operators. Original research, case studies and editorials that provided data regarding the tests of competence were included. Hand-searching of the references in key papers was undertaken to ensure missing relevant papers were included.

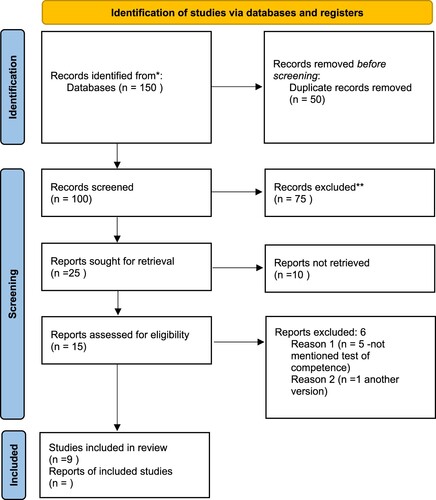

The initial search yielded 150 records. After the application of delimiters, 100 abstracts remained for review which was then screened for eligibility for inclusion using the criteria (a) English language, (b) publication between 2015 and 2023, and (c) Nursing and Midwifery Council Tests of Competence. Of these, those which did not focus on nursing and midwifery OSCE tests were excluded. The publications did not include international papers not specific to the UK context. The papers were screened by their titles and abstracts and later for relevance by full texts. Twenty five articles were fully reviewed. Of those, 15 of them were either duplications or did not address the competency tests. Finally, nine articles, each of which addressed the issue of competency tests as perceived by the overseas nurses met inclusion criteria and were examined in this review ().

Table 2. Articles included in the review.

Data extraction involved DD reading the selected papers several times and creating annotated summaries and emerging themes from the results and discussion sections of the papers. This was then verified by SS. The number of papers screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review together with details of exclusions is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram ().

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

Results

Themes captured: There was a paucity of studies that addressed the experience of overseas nurses who faced the OSCE. An interpretative stance (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2005) was adopted to formulate the themes as set out in .

Table 3. Themes developed.

Competency/practice disparity: A disparity between the reality of clinical practice and the standards and competency requirements of their National Health Services (NHS) trust (A trust is an organisational unit within the NHS services in England and Wales, generally serving a geographical area) were highlighted (Gillin & Smith, Citation2021). The nurses in this study perceived the clinical skills and procedures required of the OSCEs as markedly different to those required by their employer Trusts, echoing Foster (Citation2018) who found that education leads had also noted a disconnect between practice and OSCE requirements. The OSCE competencies did not correspond with those required in their clinical areas, and an OSCE pass was not considered adequate preparation for work in their clinical areas. What they had learnt for the OSCEs was considered different and sometimes contradictory to the standards required of them in practice (Gillin & Smith, Citation2021). It was also felt that 15 min is not enough time to complete an OSCE. Staff have been advised to use the Royal Marsden manual (Dougherty and Lister, Citation2015) to prepare for assessment; however, in some aspects of care, for example, aseptic non-touch technique, the manual offers contradictory advice. The idea that Trusts focus on passing the OSCE, perhaps to the detriment of wider skills is depicted in this quote: why they do not go to clinical practice until after OSCE is taken as OSCE uses specific paperwork for its assessment (Davda et al., Citation2018). Such a statement points to the fact that the Trusts are concerned that overseas nurses may pick things up during clinical experience that will endanger them in acquiring the skills to pass the OSCE.

The consequences of failing the OSCE: Failing to obtain an OSCE pass and hence join the NMC register within the maximum allotted time of eight months after entering the UK can lead to a cascade of events, including a cancelled NMC application, a subsequent termination of sponsorship of employment and the curtailment of their visa and hence right to remain in the UK. Returning to their home country is a likely outcome for those who do not obtain an OSCE pass within the allotted time frame. It also meant that though they remained employed during this time nurses were delayed in acquiring Band 5 Registered Nurse status and continued on a lower pay scale until all NMC competencies were achieved.

Failing the OSCE due to arbitrary issues: Some reasons for failing the tests were arbitrary and staff questioned whether the failures really constituted a risk to patient care. For example: disposing of a plastic ampoule (labelled ‘this is glass’) in the wrong clinical waste bin, running out of time (despite demonstrating good practice), inconsistencies when speaking to actors performing role-play, failing to say they would wash their hands each time they role-played a procedure, poor handwriting, reasonable adjustments not being made; for example, a short nurse could not reach a patient to do CPR, spillage of water but no equipment available to mop the floor.

Failure to capture the forward-thinking agenda: Whilst there is a forward-thinking agenda such as Royal College Nursing (RCN’s) ‘every nurse an e-nurse’ (RCN consultation on the future of digital nursing and digital leadership), and digital skills in the nursing curriculum, this is not reflected in the amended OSCE tests. Whilst the trusts are striving to become digital, in these OSCEs overseas nurses are required to use hard copies of observation charts, for example.

Financial implications – There was also the element of financial implications. A cost analysis of medical OSCE carried out by Brown et al (Citation2015), a student cost of £355 for a 2 d 15-station medical OSCE. However, the NMC OSCE (6 station) exam costs £992 per student. In addition, there is the high cost associated with preparation for the OSCE: time for training, time for paid supernumerary time and the costs of consumables also impact trusts, especially if staff do not pass the first time.

Language tests

Time spent in the country: The studies, Bond et al. (Citation2020) and Davda et al. (Citation2018). highlight the time spent on adapting the communication style to that of the host country or understanding all the nuances.

Failure to incorporate cultural nuances of the NHS and the host country

What was intended to test the academic competency, capacity and capability for academic undertakings, these standardised tests do not go beyond the proficiency where there is the ability to handle cultural and professional demands in the work setting - an essential component of the role of a nurse in a particular practice setting and professional communication (Davis & Johnson, Citation2022).

Difference in assessment: Whilst overseas nurses are assessed for language proficiency whereas UK nurses are not the way communication skills are assessed in UK nurses is different from how overseas nurses are assessed. (UK nursing students are not assessed for their proficiency in the English language but are assessed for empathetic and compassionate communication skills during their clinical placement by their practice assessors or practice supervisors). In addition, different aspects of communication skills are assessed in overseas nurses from those assessed in UK nurses.

Discussion

According to Rushforth (Citation2007), OSCE assessments are a reliable and valid method of assessing healthcare professionals including nurses. It is a gold standard of assessment in many countries like the UK, the US and Canada. OSCE assessments replicate real-life scenarios. The OSCE is used by the UK nurse education program to define practice education and allow reflection before, in and after placement.

However, Foster (Citation2018); RCN (Citation2020); and Jevon (Citation2018) raise concerns about how we need to ensure that the regulation policy and assessment process is realistic and not pedantic – and that nurses from overseas are not held to higher standards than those trained in the UK. Within the wound care station, a candidate is assessed on handwashing, consent taking, communication and performing wound care by using an aseptic non-touch technique. The candidate is expected to complete wound dressing in 17 min.

When a candidate is unable to demonstrate full criteria in a wound care station and unable to complete it within the allocated time, they are asked to repeat a station. Whilst patient comfort and safety are safeguarded during a clinical skill, not completing a wound dressing within a stipulated time does not mitigate patient safety.

Such arbitrary reasons for failing question whether the failures really constituted a risk to patient care or whether it is a failure because it is performed under exam conditions. Running out of time (despite demonstrating good practice) does not compromise the evidence base, nor does disposing of a plastic ampoule (labelled ‘this is glass’) in the wrong clinical waste bin comprises patient safety (Foster, Citation2018). This orientation comes under Trust Policies. Not all Trusts follow Royal Marsden clinical procedures (Foster, Citation2018) – there will be variations in the clinical procedure without compromising the evidence base. In some aspects of care, for example, aseptic non-touch technique, the manual offers contradictory advice (Foster, Citation2018). Whilst patient comfort and safety are safeguarded during a clinical skill, not completing a wound dressing within a stipulated time does not mitigate patient safety.

OSCE becomes station-specific and performance may get influenced by how the station has been set up (Harden, Citation2016). Furthermore, whilst the student nurse needs only to face the exam pressure, the overseas nurses need to deal with in addition to the unfamiliar exam conditions, the financial implications and visa limitations when faced with failure. To a certain extent, the OSCE assesses the applicant’s ‘understanding’ of nursing practice in the UK health care context, however, it does not imperatively confirm whether the nurse is ‘safe’ and effective’ in the role in which they will be employed. Candidates who fail to complete within the allocated time under pressure do not replicate the real situation and need to be reconsidered. Whilst the OSCE – test of competence could seamlessly confirm whether a UK-educated student nurse is ‘fit for registration’, it would be unwise to think such a once off time constrained competency test would enable an overseas trained nurse to demonstrate that they too are ‘fit for registration’. This signifies that we must ask the most basic questions about the way we assess the ‘safety’ through OSCE assessment/demonstration of critical competencies.

More importantly, the digital skills in the reviewed Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses - Future Nurse - (NMC, Citation2018) are not reflected in the amended OSCE tests. In addition, not all Trusts are yet totally digital and most use different systems. This, coupled with the theme that there are variations in the procedure, is an argument for the practical assessment being done in the location where they plan to work.

The language tests

The link between language barriers and critical events has been highlighted (Baker & Robson, Citation2012) signposting to the language needs of the healthcare profession and the critical nature of communication. However, the means to test ‘English language proficiency has always been a topic of debate. As early as the 1990s the insufficiency to completely estimate the English ability of candidates in specific medical contexts was signposted. The main criticism lies in the fact that the IELTS was primarily designed for use in the academic domain (Wette, Citation2011). This criticism has echoed down through the years (Sedgwick and Garner Citation2017) that these tests may serve well as predictors of general language proficiency but are of little value in predicting ability in medical communication.

Lepetit and Cichocki (Citation2002) report that oral skills were deemed most relevant to health professionals. Their findings add to the debate by signposting the empirical need to move away from a concept of overall Level (Band 7 IELTS) to the realisation that different language sub-skills may prove to be important for individuals engaged in different professional roles. Taylor and Pill (Citation2013) also sought to compare methods of assessing the English language proficiency of health professionals, mainly doctors, seeking to practice in the UK and Australia. They conclude that the inter-relationship between language proficiency, communicative competence and clinical communication skills is an extremely complex problem which requires much further study. They highlight the time spent on adapting the communication style to that of the host country or understanding all the nuances.

A period of time should lapse before overseas nurses can adapt their own communication style to that of the host country or to understand all the nuances of customs and conventions. s . This integration is essential to understanding the complexity of the profession in its critical pathways leading to continuing competence and career advancement.

This scoping of the literature attests to the fact that passing an English proficiency test does not guarantee communication success in the workplace. Beyond the level and content of IELTS, there is scarce research done to determine the quality practicality and usefulness of these tests in the professional context. English language proficiency has a direct impact on patient safety, however, questions about which tests and standards to use deserve thoughtful deliberations by regulators. What was intended to test the academic competency, capacity and capability for academic undertakings& nbsp;(Moore Citation2015), these standardised tests do not go beyond the proficiency where there is the ability to handle cultural and professional demands in the work setting - an essential component of the role of a nurse in a particular practice setting and professional communication. Though it is essential to protect entry to the nursing register to safeguard the public, it should not be by rejecting experienced, safe and able practitioners when we are desperately short of staff. There is a need for us to learn from each other to harness the best practice or the innate wisdom of the practice. Nonetheless, overseas nurses are expected to assimilate into the healthcare system in a host country, which identifies significant ethnocentricity and judgmental attitudes that could create tension among overseas nurses. This exposes a gap in the registration regulation which perpetuates discrimination and threatens workforce integration.

From scoping of the literature (Foster, Citation2018it is understood that overseas nurses are expected to adapt to UK nursing practice without any consideration or sensitivity towards their values and beliefs, thus devaluing their previous experience and expertise. NHS policy and practice reinforce the perception that newly registered IENs require the same support as UK-trained new registrants, and so IENs are often required to revert from the high-level expert knowledge they have built up to return to a band of employment synonymous with newly qualified. Davda et al. (Citation2018) in their systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies suggested that overseas nurses experienced loss of status and are being deskilled. Despite considerable expertise, when they first arrive in the UK, they are reliant almost exclusively upon their colleagues and this leads to feelings of incompetence, lack of respect and decreased job satisfaction. A prescriptive registration focussing solely on temporal clinical competency and academic linguistic ability does not suffice to ensure amiable workforce integration.

The scoping review highlights the need for adaptation programmes that incorporate two essential features – learning needs in academic settings and supervision and preceptorship in clinical settings. Learning occurs at the transaction of history, biography and culture (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991), in the space between what the health professional already knows and what social practice has to offer. When new learning situations arise, a transition occurs during which previous learning is reshaped and restructured through adequate support. What we are asking of the overseas nurses is to transition from the personal, social and historical grounding of their country and profession - bounded by different history, culture and context. Integration or adaptation programs should consider such formidable complexity of transition learning.

Internationally educated nurses who bring competencies acquired in cultures and educational systems unfamiliar to regulatory authorities are powerless to negotiate without a place or voice in the discourse (Van Kleef & Werquin, Citation2013). There should be a form of recognition of the learning the newcomers bring with them at the same time identifying the transitional learning needs. Any instructional undertaking in a cross-cultural context should depend on the application of critical pedagogies (McGee Banks & Banks, Citation1995) which reflect the values of such niche groups and challenge the presumptions, thus enabling and empowering the overseas nurses. The benefit of such undertaking is dual - provides a less arduous and complex process for the overseas nurse to engage with as well as build communities of practice.

As academic nurse educators, we appreciate that international nurses bring skills and knowledge into the NHS, but the task of adapting to nursing in the UK is complex both for the nurses supporting them in the clinical practice as well as the international nurse adapting to the host culture. We do acknowledge the importance of ‘fitness to practice’ to ensure public safety. However, we reiterate there is a need to use a robust system that facilitates effective integration through cultural awareness, knowledge and sensitivity. Throughout any integration program we should have workshops on communication, and cultural competency thus incorporating principles of cultural pluralism, equality and inclusivity that can mitigate against such devaluing experiences. Overseas nurses’ skills and experience must be valued so that nurses should not feel treated like newly qualified staff and must provide an inclusive culture. Delivered by practitioners rooted in practice, content quality checked and benchmarked, we must endeavour to produce a cohort of nurses who are not just OSCE ready, but able to join the NHS and enrich the nursing practice by contributing their wealth of expertise and knowledge.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. Due to the heterogeneous nature of the included literature, no critical appraisal is offered. However, the broader search criteria to include expert opinion and basic qualitative research provided additional depth of understanding of the challenges these nurses face in navigating these tests of competence, specifically the OSCE.

Conclusion

Any integration programs is a means of bridging the gap and giving a voice to overseas candidates perceived to be situated at the periphery, but the feasibility of the program relies on the preparedness of key stakeholders to negotiate a shared understanding of the process. To ensure the UK and NHS remain a desirable option, we must ensure that adequate support mechanisms are in place to ensure successful integration, patient safety and outcomes and a high retention rate.

It is reassuring to note that NMC has recognised the need to amend the current guidance on IEN support with the introduction of the Principles for Preceptorship’. Even then, it does not highlight how the program should be designed to complement the knowledge skills attributes and competencies that the health care professional has already attained at the point of their registration. However, it does provide an opportunity for UK healthcare providers to also update and change their policy and practice. By acknowledging and valuing the expertise that IENs bring to UK healthcare, it is hoped that this will fundamentally alter the experiences of IENs, enhancing their integration and impacting retention. Such a program (transitioning from overseas practitioner to registered practitioner), drawing on research evidence on international nurses’ experiences of integration with NHS culture, will add value to the NHS agenda and drive to recruit and retain internationally trained nurses and to help overseas healthcare practitioners gain access to Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) Register.

This article brings into focus the challenges the overseas trained nurses go through in the journey towards registration with the NMC council and integration with the NHS culture and reorientation to the profession. As global social risks and volatilities intensify, plugging nursing gaps in the economically developed world with nurses from the developing world will become increasingly unpredictable as the ability of governments in destination countries to guarantee ontological security becomes more uncertain. Although it was agreed that we need to protect entry to the nursing register to safeguard the people we are caring for, trusts are rejecting experienced, safe and able practitioners when we are desperately short of staff. Following on from the two years which thrust the nursing profession into stark focus, perhaps it is time to acknowledge the clinical and specialist expertise of the overseas training and how it can be of value to redefining care, shaping leadership, inspiring reflection of education and changing lives.

Author contributions

Search: DD, SS.

Themes: DD, SS.

Manuscript writing: DD, SS, MT.

Critical revisions for important intellectual content: DD, SS.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (82.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2024.2318360.

References

- Allan, H., & Westwood, S. (2016). Non-European nurses’ perceived barriers to UK nurse registration. Nursing Standard, 30(37), 45–41. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.30.37.45.s41

- Allan, H. T., & Westwood, S. (2015). English language skills requirements for internationally educated nurses working in the care industry: Barriers to UK registration or institutionalised discrimination? International Journal of Nursing Studies, 54(2), 1–4.

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Baker, D., & Robson, J. (2012). Communication training for international graduates. The Clinical Teacher, 9(5), 325–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00555.x

- Bond, S., Merriman, C., & Walthall, H. (2020). The experiences of international nurses and midwives transitioning to work in the UK: A qualitative synthesis of the literature from 2010 to 2019. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 110, 103693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103693

- Bond, S., Ricketts, B., Walthall, H., & Merriman, C. (2023). An online questionnaire exploring how recruiting organisations support international nurses and midwives undertake the OSCE and gain UK professional registration. Contemporary Nurse, 59(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2023.2166549

- Brown, C., Ross, S., Cleland, J., & Walsh, K. (2015). Money makes the (medical assessment) world go round: the cost of components of a summative final year objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). Med Teach, 27(7), 653–659.

- Davda, L. S., Gallagher, J. E., & Radford, D. R. (2018). Migration motives and integration of international human resources of health in the United Kingdom: Systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies using framework analysis. Human Resources for Health, 16(27), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0293-9

- Davis, D., & Johnson, M. (2022). A way out of pre-registration limbo? British Journal of Nursing, 31(12), 668–669. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2022.31.12.668

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed, pp. 1–32). Sage.

- Dougherty, L., & Lister, S. (Eds.). (2015). The Royal Marsden manual of clinical nursing procedures. John Wiley & Sons.

- Foster, S. (2018). Are the tests for overseas nurses fair? British Journal of Nursing, 27(9), 525–525. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2018.27.9.525

- Gillin, N., & Smith, D. (2021). Filipino nurses’ perspectives of the clinical and language competency requirements for nursing registration in England: A qualitative exploration. Nurse Education in Practice, 56, 103223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103223

- Glasper, A. (2013). NMC reviews registration of nurses trained outside the EU. British Journal of Nursing, 22(10), 586–587.

- Harden, R. M. (2016). Revisiting ‘assessment of clinical competence using an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE)’. Medical Education, 50(4), 376–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12801

- Jevon. (2018). Are we asking overseas nurses to jump through too many hoops?

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press.

- Lepetit, D., & Cichocki, W. (2002). Teaching languages to future health professionals: A needs assessment study. The Modern Language Journal, 86(3), 384–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00156

- McGee Banks, C. A., & Banks, J. A. (1995). Equity pedagogy: An essential component of multicultural education. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543674

- Moore, C. (2015). Is IELTS the right english test for overseas nurses working in the UK? https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ielts-right-english-test-overseas-nurses-working-uk-chris-moore .

- NHS England. (2021). Interim NHS People Plan: NHS workforce recommendations for recovery. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/interim-nhs-people-plan-nhs-workforce-recommendations-for-recovery/.

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. (2018). The code. 2018. https:// tinyurl.com/vx2nm734.

- Nursing & Midwifery Council. (2014). Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates.

- Royal College of Nursing. (2020). Safe and Effective Staffing: The Real Picture. https://www.rcn.org.uk/clinical-topics/staffing-and-capacity/safe-and-effective-staffing.

- Rushforth, H. E. (2007). Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE): review of literature and implications for nursing education. Nurse education today, 27(5), 481–490.

- Sedgwick, C., & Garner, M. (2017). How appropriate are the English language test requirements for non-UK-trained nurses? A qualitative study of spoken communication in UK hospitals. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 71(2017), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.03.002

- Taylor, L., & Pill, J. (2013). Assessing health professionals. In A. J. Kunnan (Ed.), The Companion to Language Assessment. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Teare, G., & Taks, M. (2019). Extending the scoping review framework: A guide for interdisciplinary researchers. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 23(3), 311–315.

- Van Kleef, J., & Werquin, P. (2013). PLAR in nursing: Implications of situated learning, communities of practice and consequential transition theories for recognition. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 14(4), 651–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0260-6

- Wette, R. (2011). English proficiency tests and communication skills training for overseas-qualified health professionals in Australia and New Zealand. Language Assessment Quarterly, 8(2), 200–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2011.565439