ABSTRACT

The paper presents a scoping review of existing economic evaluations of assistive technology (AT). The study methodology utilized a PRISMA flow approach with final included studies that met an adapted PICOS framework. Types of economic evaluations employed, study type and rigor and domains of AT impact were considered and analyzed. The economic evaluations in this study included 13 CBA, 9 CMA, 18 CEAs and 10 CUA. The majority of studies (32 studies in total) mentioned or recorded that AT investment, access and/or usage had impacts on the domain of both informal and formal health care. Specifically, care costs, time, and resources were affected. Our study has found that current AT economic evaluations are limited. This study advocates for a wider use of robust alternative evaluation and appraisal methodologies that can highlight AT value and which would subsequently provide further evidence that may make governments more willing to invest in and shape AT markets.

Background

Economic evaluations are a significant and widely used form of assessment that are taken up by various sectors within the health field. The importance of understanding and capturing economic value for any intervention or device within the field of health is essential and for this reason, economic evaluations of assistive technology (AT) have used monetary value and market worth to assess the value to the provider (Deruyter, Citation1995; Galvin & Scherer, Citation1996; M.J. Fuhrer, Citation2001; Smith, Citation1996). Economic evaluations are a type of comparative analysis of alternative health-care strategies or programs in terms of costs and consequences (Drummond et al., Citation1997). They should consider both cost side and an outcome and benefit side. Within the general health-care field, such cost assessments are problematic, as noted by M. J. Fuhrer (Citation2001), as the economic perspective of cost can greatly vary depending on the perspective taken, i.e., from the vantage points of patients, insurers, providers, or greater societal perspectives. Within the field of AT, public costs have tried to take into account the perspectives of patients, AT programs, family members, taxpayers, employers, and insurers (Andrich et al., Citation1998; MF Drummond et al., Citation1993; M Drummond et al., Citation1997; Goldman et al., Citation1996).

Economic evaluations are considered an integral part of the planning process of any health program. While in most fields of medicine decisions on medical interventions are evidence-based through direct comparison between benefits and costs, the provision of AT has been an exception. Part of this can be explained by the complexity of AT outcomes (Gelderblom & de Witte, Citation2002). This has been especially highlighted and stressed for interventions designed to address the complex needs of AT users. Due to the complex health and social problems associated with AT users, economic evaluations should also be able to consider such complexity. Further, comparisons between different AT devices, even in instances within the same device classification, can be exceedingly difficult due to the diversity of how the practitioner matches the technology to individual needs, what materials are deployed at what cost, and how that product is delivered and works within the user’s environment.

Economic evaluations – as well as more general evidence assessments of AT impact on the user, the community, and overall society – are few and far between. Like any other device or intervention that aims to benefit a population or specific user, AT also should have within its field a mix of assessment tools that can capture its benefit. The tenants of evidence-based practices (EBP) have been championed in the literature by numerous health professionals, occupational therapists, physical therapists and other practitioners linked to AT (Holm, Citation2000; Manns & Darrah, Citation2006; Marcus J. Fuhrer, Citation2007). Specifically, Holm (Citation2000) writes that patient outcomes alone are no longer sufficient to justify services, but rather there is a strong call for EBP. As a result “[occupational therapists] have an obligation to improve our research competencies, to develop the habit of using those competencies in everyday practice, and to advance the evidence base of occupational therapy in the new millennium” (Holm, Citation2000, p. 584). Similarly, Manns and Darrah (Citation2006) write how physical therapy physicians and researchers must find ways of enhancing EBP, so that it can be used optimally as part of clinical decision making.

Yet, while AT practitioners are proponents of having and being able to refer to a solid evidence base, quality research on the impacts of AT on outcomes and AT value is extremely limited (Marcus J. Fuhrer, Citation2007). Despite the wide range of technologies available on the market, there is little hard evidence related to the success of AT systems in terms of how effectively they provide support for the individuals who use them and at what cost (Jacobs et al., Citation2003). Without a wider breadth of concrete evidence, which would demonstrate and capture the full extent of AT effectiveness and efficacy, financial support toward AT access and delivery will continue to be minimal and exclude a variety of AT options. Health-care services rely on evidence-based approaches to justify budgetary decisions, as highlighted by Marcus J. Fuhrer (Citation2007), who gave the example that Medicare adjusted its payment guidelines to ensure that financially covered mobility AT devices (such as wheelchairs, crutches, canes, and prosthetic devices) met certain quality and outcome-based standards. If payers of health-care services rely on narrowly scoped evidence-based approaches to justify budgetary decisions, this may have implications on AT diversity and availability. This is especially true in the AT field where the plethora of devices and uncertainty of preferences by experts reign (Marcus J. Fuhrer, Citation2007). Likely because of the expansiveness of the field of devices and lack of consensus, there is a greater need for studies to be able to provide credible, comprehensive and meaningful evidence of the impact and value of AT. Accordingly, it is essential to look into the existing body of evidence to understand how AT impacts and value are currently framed. Through the aggregation and analysis of AT evaluation studies, this research captures the evidence landscape of AT and comments on how AT is valued within the research and policy community. The objective of economic evaluation is to identify, measure, and value what society forgoes when it funds an intervention (the opportunity cost) and what it gains (the benefit). Economic evaluation provides an important evidence base for decision-making in the health-care sector, aiding policy makers in the allocation of societal resources.

Aim of the scoping review

The aim of this scoping review is to capture the breadth and diversity of economic evaluations, appraisals, and measurements that are used to assign and define AT value. The focus of the search is to locate studies that assign an economic value with particular focus on capturing and assessing studies that use one of the following approaches: cost-benefit analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-minimization analysis, or cost-utility analysis. Consideration is given to any study that meets defined and standardized economic evaluation criteria as well as studies that use alternative evaluation approaches. The evaluation assessments include studies that analyze the impacts of AT by considering the value the enabling device has on the individual, family, community, labor force, as well as health and social care systems. AT value can also be captured upstream and include value produced as a result of a state’s investment into AT production, manufacturing and distribution facilities. This type of search seeks to illustrate where AT value stands within the literature capture. A need to collate and systematically review the existing cost-effectiveness and return on investment evidence serves as the impetus for the WHO AT background papers.

Capturing the strengths and weaknesses of “gold standard” economic evaluation framework

Evaluation frameworks are important as in many ways they structure and define the value of particular devices and interventions. The “mainstream” approach to evaluation is derived from neoclassical economic theory, in particular microeconomic theory and welfare economics (Dequech, Citation2007; Kattel et al., Citation2018; Kattel, Citation2020; Nelson & Winter, Citation1974). Dequech delineates neoclassical, heterodox, mainstream and orthodox economics. Based on Dequech’s research, neoclassical economics is characterized by the combination of (1) the emphasis on rationality in the form of utility maximization, (2) the emphasis on equilibrium or equilibria, and (3) the neglect of strong kinds of uncertainty and particularly of fundamental uncertainty (Dequech, Citation2007). While Dequech (Citation2007) finds that mainstream economics is temporally very general, neoclassical economics is the core thread within the mainstream approach as evident by its presence in the curriculum of prestigious economic departments and as a result of its placement within the economic literature. The influence of neoclassical economic thinking is apparent within policy evaluations and appraisals as techniques of static ex-ante cost-benefit analysis (CBA) reign dominant (Kattel, Citation2020, p. 6).

Gold standard economic research protocols focus on efficiencies and cost-effectiveness. The most highly valued analyses include CBA and cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA). CBA-type analyses are concerned with allocative or distributive efficiency, which involves making the best use of (fixed) resources at a fixed point in time. These appraising techniques, while they are currently held up as the highest golden standard of evaluation, are acknowledged to be limited as they rely on the assumption that the broad environment remains unchanged as a result of the intervention. They poorly handle dynamic interactions and can only capture marginal changes when conditions are thought to remain stable. Classic return on investment (ROI) schemes and cost-effectiveness scales are blunt instruments in which research funding has historically relied on in order to justify the usefulness and value of an intervention or device.

Instead of trying to have the AT landscape emulate other fields and only look at the robustness of rigid and supposedly neutral gold standard economic evaluations, this study follows the suggestion of Harris and Sprigle (Citation2003) as cited in Schraner et al. (Citation2008) to pay particular attention not just to methods, but the perspective employed by economists. Economists when choosing to show benefits of a device or program, apply a particular lens and perspective in which the AT assessment will be understood. Based on Can Feminist (Citation1995), but reinterpreted by Schraner et al. (Citation2008), there is concern that within the field of AT, health economists will “only engage with the work of medical practitioners who are mainly interested in body functions and structures, and as long as the scrutiny of the economists’ work is limited to questions of methods, economists continue to limit themselves to analyzing a small part of what is or ought to be of interest to health economists” (Schraner et al., Citation2008, p. 923).

Given the critical insight about economic evaluations, this study considers how AT value is constructed by paying attention to the rigor and robustness of the evaluation studies, the types of evaluation methodologies employed, and the lens/perspective utilized. Further, this research associates itself with those in the AT community that wish to consider a concept of AT value that includes the impact of AT technological innovation through to how AT can enable human capabilities.

Studies that demonstrate AT value may be especially important for policy decision-making in lower-resourced settings, such as low-middle income countries (LMICs) whereby governments may feel even more compelled to justify spending and investment decisions if the mind-set is one of limited funds and resources. Currently in many LMICs, production of AT is low, and where access is possible, costs are excessive (WHO Citation2014; Schüler et al., Citation2013). While production of, and investment into, AT is low, there is an opportunity to grow this industry domestically as countries, such as Brazil, Cambodia, Egypt, and India have done over the past decade (WHO Citation2014). Part of this movement may be due to governments slowly recognizing that when the narrative of AT value switches from simply considering purchase cost to the entirety of value that can be found within the AT ecosystem, AT value is positive and potentially robust. For instance, in-country production of AT devices in Brazil has resulted in a reduction of AT costs by 30% as compared to importing such devices (Marasinghe et al., Citation2015). The potential for how comprehensive system-wide economic evaluations may alter the narrative of AT from being a costly investment in LMICs to a human-enabling device that has great economic potential within a system necessitates a review of existing economic evaluations.

Recognizing the interest in a more comprehensive assessment of how to best value AT by the research, policy, user, and advocacy communities, the discussion of the following results entails considering where AT economic evaluations stand currently and how they might be better transformed to reflect the value understood but not captured by the AT community. It also suggests ways of making the “invisible value” of AT innovation evident.

Methods

Identification and search strategy

The methodology for this study entailed conducting a scoping review that dove into academic literature and gray literature. AT devices examined in the literature were determined by the WHO AT priority list.Footnote1 The literature search was conducted in English, Norwegian and Swedish. Nordic partners were brought in to capture AT evaluation studies published in Scandinavian languages as this region is known to produce interesting and novel methods of evaluation with regards to AT. A PRISMA-compliant search of the literature was conducted. The search comprised two steps as per the guidelines provided in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook on Systematic Reviews of Interventions.Footnote2 A preliminary search was conducted which identified original articles in the following electronic databases: Econlit, PubMed Clinical Queries, EBSCO Host, and Scopus. A full search was also undertaken in CINAHL, Embase, Global Health, Medline, PsychInfo, and Social Work abstracts.

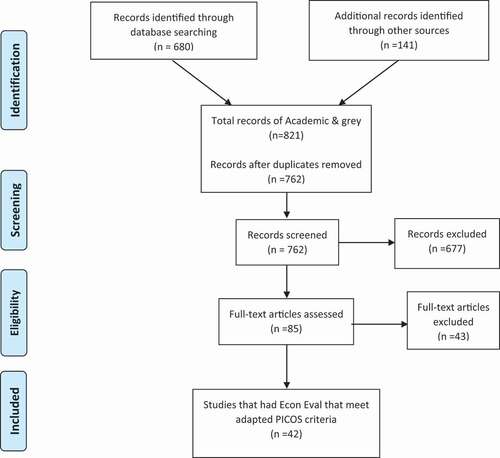

The gray literature was based on searching through the websites of known NGOs that focus on AT, government bodies dedicated to AT, as well as private and industry partners that conduct relevant work in AT. Studies that were found on such websites (which were determined and selected based on familiarity with the AT landscape of the researchers) were pooled for further examination. The gray literature search () was not restricted to a specific search string. Rather, starting from the initially identified organizations and organizational websites, there was an additive snowballing search strategy for the gray literature to collect studies that otherwise would have been difficult to capture.

Figure 1. PRISMA search criteria. Adapted from Stovold, E., Beecher, D., Foxlee, R. et al. Citation2014

Eligibility criteria

The literature search was compliant with the PRISMA search criteria and included all articles from the date range of January 1990–January 2020. The academic search string used a combination of evaluative terminology including; cost-benefit analysis, return on investment, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-utility analysis, and social return on investment. The search string also consisted of words related to evaluation, assessment, measurement, value and impact. These words were selected because they were analogous to assessment and evaluation. In terms of capturing assistive technology, the research strategy first conducted a general search of assistive technology through terms, such as: assistive products, technologies, and devices. For the academic search, the study then incorporated the specific assistive products as defined by the WHO product priority list into the search string along with the selected evaluative terminology. For the gray literature search, a similar approach of crafting an initial search string of an evaluation term and an assistive technology term was also implemented within the specific organizational websites. However, because of the snowballing approach of case study gathering, the researchers did not search for each one of the specific assistive products on the WHO priority lists for the gray literature search.

Both academic and gray texts were included based on their titles featuring some combination of an evaluation term and either a broad term of assistive technology, or a specific assistive product. The articles were uploaded to a reference software and duplicates removed. Thereafter, articles were screened for further eligibility based on the full text and whether the article appeared to be about measuring the value of AT through an economic lens. Consideration of economic evaluations studies were based on the PICOS criteria, a study assessment framework which looks into the parameters; Patients, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study Design. However, the criteria were extended to include alternative economic approaches that also try to capture AT value. A PICOS process was chosen as it is used in evidence-based practice to frame and answer health and health care-oriented questions. PICOS is a well-established framework in systematic reviews to ensure comprehensive and bias-free searches, and inclusion of relevant literature (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). Studies that met final inclusion PICOS criteria, as defined in , were assessed in the final analysis. Articles were also further categorized based on whether a “gold” standard economic measurement and study protocol was used, versus those studies that used additional alternative or comprehensive techniques to capture AT value. These two evaluation groups were overall analyzed equally and together. As it was also important to understand the fields in which the AT evaluation literature were sourced from, the disciplinary fields were also noted.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria and table suggested inputs

Domains of AT impact through the use, access or industry interaction

Information from the studies was extracted concerning domains of AT impact as well. It is important to capture the outcomes and AT impact domains as traditionally these studies will take note of these arenas of where AT had impact, but they will not be reported as part of the main study findings or considered important compared to the single number of cost savings reported. This is essential for an area like AT that has a diversity and range of technologies, populations, and outcomes and thus single cost-effectiveness numbers are rarely comparable and thus hold little meaning and transferability.

Domains of AT impact entail consideration of how AT interfaces with either a user, family, healthcare, or industry (along with other entities). The domains of AT impact can be measured at different conceptual levels ranging from functional performance to quality of life (Gelderblom & de Witte, Citation2002). This study goes further to expand beyond commonly known domains of AT impacts to include how AT investment may lead to increased employment opportunities for communities through AT manufacturing, or an enhanced feeling of independence and safety. The study also pays attention to how larger domain categories can be measured in very different ways such that the domain of health may be assessed through specifically validated surveys as disability-adjusted life-years (DALY),Footnote3 or quality-adjusted life-year (QALY),Footnote4 as well as assessed by biomarkers, mobility status, or through a self-reported health questionnaire (Jacobs et al., Citation2003). Recording and detailing the domains of AT impacts and outcomes will help to shed light on the manifold ways AT add value beyond simply what is currently costed.

Results

The results of the initial search located 680 studies, with an additional 141 articles identified from the gray literature. After the preliminary screening of titles and abstracts, 677 articles were removed. A total of 85 articles remained with 42 studies eventually meeting adapted PICO criteria for inclusion. The studies came from a diverse range of countries. The main locations in which the studies and evaluations were conducted were Sweden (10), the UK (8), and the US (6). Swedish studies were likely more dominant because of the inclusion of Scandinavian language study search. For studies that used a mix of locations, each specific location noted in the study was recorded in the below.

Table 2. The number of studies according to specific AT type and location

It was also found that the journal fields and policy domains were predominantly situated in medicine and health, disability studies, followed by engineering and computer science, psychology and social science. A few studies were sourced from the field of economics.

The economic evaluations were generally of weak to moderate quality, as many encountered several methodological limitations either dealing with small sample sizes (often times only up to eight people being studied), or if the study was able to use information from a large pool of people, the experimental design was based on assumptive models that had little AT-specific data. There were a variety of study types, though randomized control trials and quasi-experimental pre-post intervention designs were the most dominant. Study types included prospective cohort, RCT, survey design, and several others detailed in . The data was primarily collected through interviews and surveys. Study size varied considerably from four individual interviews to a full panel study of 37,544 sampled participants.

Table 3. Study design types

Economic evaluations methods types and value framing

The economic evaluations employed within the selected studies included 13 CBAs, 18 CEAs, 10 CUAs and 9 CMAs (). Studies that used a mix of cost evaluation instruments would fall into more than one costing category. For instances some studies could both be listed as cost-effectiveness as well as cost-benefit study if these evaluation assessments were both deployed in the study design. Upon closer inspection of the economic evaluations and how the studies were framed to convey the value of AT, it was found that generally the economic impact of AT was mainly based on costs saved, compared to profit/value added, or cost recovered. These studies, which were predominantly cost-effectiveness or cost-minimization studies, found that AT usage costs when compared to either standard care costs based on historical, modeled, or recently collected data, were more cost-effective.

Table 4. Economic evaluation employed within studies

Overall, costing studies can be broken down into four categories of value framing. These categories of value are: 1) AT usage resulted in a positive economic benefit; 2) The usage of AT resulted in cost savings in other domains; 3) Prolonged AT usage resulted in a recuperation of initial cost 4); Investment in AT negatively impacts cost outcomes ().

Table 5. Types of AT value cost/profit framing

Specifically AT access and usage were linked to costs saved for the health and social care systems. AT cost-effectiveness was presented in terms of how much the ability to access and use an AT saved health and social institutions compared to the “traditional” normal treatment option that usually relied on resources provided by health or social care services. ATs were more cost-effective compared to normal treatment experiences, i.e., compared to costs taken on by health and social care for supplying a personal aid. Within the research, reduction or elimination of care was based on either models which looked at the impact of reduced or total reduction of care spending or time according to available data, or was based on evidence directly collected from the study. Few studies tried to look at the social benefit and value added of AT ().

Table 6. Domains of AT Interaction that Impact or Produce Value

Domains of AT impact through the use, access or industry interaction

Domains of AT impact and subsequent outcomes, as defined and described in the last portion of the methods section, were included directly in the economic evaluation assessment and modeling. Thus, they would be represented in the final figure of how an AT demonstrated cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness, but many times these outcomes and impacts of AT were separately recorded and not necessarily added into the direct cost model.

The majority of studies (32 studies in total), mentioned or recorded that AT investment, access, and/or usage had impacts on the domain of both informal and formal healthcare. Specifically, care costs, time, and resources were affected. Care costs included both system-level care costs, such as reduction of the number of nurses needed, reduced hospital admissions, decreased nursing hours, as well as informal care costs if a family member could instead work or tend to other activities instead of needing to assist as they would when the user did not utilize the AT fully. After care cost, outcomes that were found to be important included an assessment of independence (though this was often interlinked with a care cost measurement), and some form of quality of life measurement as well as satisfaction with the technology. Of these studies that discussed satisfaction and quality of life, many specifically used the Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology (QUEST) (Demers et al., Citation1996)Footnote5 and QALY as recognized and comparable instruments. Outcomes of AT impact that were less often cited in the collection of studies examined included; stigma reduction, impacts on education and work participation, effects on transportation costs, and implications on social quality of life.

The economic evaluations undertaken by these studies were focused particularly on assessing how AT access and usage reduced the burden on either the social or health-care system, and improved individual user life. Many articles used the phrase “social cost.” A few studies also took into account the impact which AT usage had on family members. One study expanded beyond the user, caretaker, and health/social care system and considered AT costs as related to modifications in the user’s home or physical environment and the cost of materials and construction to adapt homes to be AT friendly, as well as overarching implementation costs (12, 59). The impact that AT had on employment was also occasionally brought up. Employment effects either included a potential increase in labor productivity through the usage of the specific AT (83, 85), but also how the AT impacted labor dynamics of personal care takers that were able to use newly-found time to increase or partake in the job market instead of caring for the AT user. At times, a larger societal perspective was taken, which tried to gauge value of AT of those who may not necessarily use an AT or be part of the AT ecosystem. This was captured through an AT willingness to pay (WTP) indicator (19, 31, 67). Service delivery of AT and costs associated also came up in the literature, such as the cost of purchasing and procuring the AT, maintenance of the device, or assistance needed to fix the device. One study even considered the particular mode of delivery within a low-income setting between a community-based approach versus a center-based approach and how differences in delivery models impacted facility, transportation, and food costs associated with running the center-based approach (55).

Discussion

This study found the economic evaluation mechanisms that are currently used to consider the “worth” of AT devices are of mixed quality, though they do resoundingly attempt to demonstrate that AT has value because of its ability to reduce costs to the general healthcare system. Through this preliminary investigation into the literature this paper considered the types and span of evaluation techniques present. While the studies all provided useful evidence in support of the positive value of AT, most studies framed this value only in terms of cost savings for the social and health-care systems, rather than AT value in its own right. For instance, Al-Oraibi et al. (Citation2012) assessed the cost of a particular AT by demonstrating how an AT intervention led to a reduced number of poor health outcomes, and subsequently reduced health-care costs. Some other studies have also taken this approach when evaluating the benefit of AT, by demonstrating cost-saving outcomes when AT is utilized through a pre/postintervention study, or by analyzing large data sets, which captured resource flow once the AT was introduced and how that could lead to reduced hospital admissions or fewer care hours (Lansley et al., Citation2004; Mann et al., Citation1999)

This study has considered the rigor of existing AT economic evaluations, the perspective the evaluations employed, the kind of methods utilized, and whether the evaluations took note either through the costing instrument or recorded observationally the impacts of AT on different domains. Two of these components, a comprehensive evaluation and the perspective the evaluation employs, are supported by the work of Schraner et al. (Citation2008) who highlighted that the two most essential factors to consider are the perspective of the economic evaluation and whether it took into account the entire AT system. Within Schraner et al.’s structure of what is important in terms of estimating costs, an estimation of the quantity of resources used and those related to the value assigned to each unit of resource measured are highlighted. For AT analysis the two most important factors to consider in an economic evaluation between Schraner’s and Harris and Sprigle’s inputs are to ensure that the economic evaluation takes into account the entire system surrounding the AT and to identify the viewpoint/perspective the evaluation takes (Schraner 2008; Harris & Sprigle, Citation2003). For instance, AT costs must consider not just the device but the cost of the caregivers. The lens of how AT costs should be considered include how AT impacts everyone from medical staff, family carers, AT providers and funding institutions, government health authorities, and especially the AT user themselves.

Of the evaluative techniques used, those that do show some promise take on a more comprehensive perspective of AT value and prioritize the user perspective. The SIVA Cost Analysis Instrument (SCAI),Footnote6 for instance, is aimed at helping clinicians and clients estimate the economic aspects of an individual AT program, especially when comparing the costs involved when different options are available. SCAI is a tool that demonstrates a degree of complex thinking when it comes to assessing AT economic impact. SCAI estimates cost by monetizing and valuating four categories: Investment (cost of purchasing and installing equipment), maintenance (upkeep of device), services (other services that are needed for the AT solution), and assistance (amount of human assistance needed) (Andrich, Citation2002). Traditional offshoots of WTP have also been used to determine the value of AT within society. While WTP as an instrument in itself is limited, the study objective of wishing to gather a larger perspective on the value of AT beyond the confinements of only looking at the AT user is noteworthy. In this instance, a study in Korea utilized the principle of WTP to capture how much a population values AT. This number was then multiplied by the number of households to provide an indicator of what a national budget could be placed at according to the society’s WTP for AT (Shin et al., Citation2016). Through this general population lens, this study was able to show that even non-users considered AT as valuable and in need of government financial support and investment.

Further efforts of capturing costs of AT include consideration of AT service delivery and maintenance. Brodin and Persson (Citation1995) used a function of Estimated Costs per Year to assess the cost of a wheelchair when installment, interest, maintenance, energy, spare parts, transport, and assistance were taken into account. This demonstrates the various costs associated with AT for the user as well as the system beyond simply considering one-time initial user costs.

Another factor that ought to be considered when reviewing available evidence of cost-effective assessments within AT is global applicability. Considering the global applicability of a study is important as AT studies conducted in a high-income country setting will lack transferability if emphasis is placed on costs saved because of social and health-care reductions. A model based on how the provision of an AT will result in fewer hospital admissions, or a decrease in house aid hours and, therefore, will reduce the cost to the government as compared to providing an AT, may not be a strong argument for countries that do not have the same health and social care infrastructures that already supply such social and care nets. Under such a framework of health and care resource cost reduction, in these settings without either the applicable data of how AT will alleviate institutional health system cost or a comparable health and social care system, the relevance that AT will reduce cost on the health and social care system may not have the same poignancy. Rather, presenting AT in terms of costs saved for such country settings when investment in AT is already negligible, may not encourage investment if the cost reduction models are based on inappropriate health and social care assumptions. One must steer away from defaulting to the existing regiment of looking at AT access as a cost-alleviating measurement for health and care services.

Instead, one study taken from the gray literature that provides a way forward for LMICs was the WHO Economic Assessment of Alternative Options: Provision of Wheelchair in Tajikistan (WHO Citation2019). This report models not just how in-country wheelchair assembly is often cheaper than importing fully assembled products, but rather proposes how the creation and production of an entire AT resource chain can provide numerous employment opportunities that will readily recover initial investment cost. Consideration of the AT innovation chain from initial production to user experience and how the AT enables human capability ought to be the framing going forward to accurately capture how AT may bring about economic, individual, and societal growth.

Economic evaluations methods types and value framing

Thus, this scoping study provides an initial snapshot of the assessment, evaluation, and evidence landscape surrounding AT. Through this study, and by capturing the evaluation, assessment, and evidence practices surrounding AT, the authors hope that the reader has a better understanding of how AT is currently evaluated, and therefore valued based on particular assessment practices and assumptions. This paper proposes that the current assessment framework of AT needs to be broadened whilst considering how to ensure the greatest levels of comparability and quality. Further, this research advocates against using simple models of ROI and CBA as they fail to capture greater system AT value.

Reflecting on our study’s findings, we propose to measure the public value of AT with particular focus and consideration of how AT impacts the innovation ecosystem, the overall community, and how best to go about shaping the AT market. This approach will help to further enhance conversations concerning how best to prioritize and make decisions that will be translatable and useful beyond a research and evidence base. Through its public value orientation, the approach will help governments to decide what actions should be taken based on which decision pathway will most likely enable multiple direct and indirect beneficial consequential effects on such important sectors as the economy, healthcare, and innovation. It is important to understand the impact and type of value generated in an innovation ecosystem as well as how AT can positively impact and enable user capabilities.

Further, the implications of advocating for and embracing alternative economic evaluations with AT within LMICs would enable an evidence environment in which the individual user as well as the service delivery system are able to make better-informed decisions on the choice of AT available as well as better-informed decisions on the range of AT offered. By reorienting how to assess AT, this will serve as an important catalyst for awareness of AT value and wider economic impact and enhance investment in AT provision, innovation, procurement, and distribution in a positive direction especially within LMICs.

Limitations of the study

The findings are constrained by the search strategy and the databases in which the search strategies were conducted. The AT devices that were considered were determined by the AT Priority device list and may not have included certain devices such as robotics which enable human capability but are not one of the selected Priority devices. While some of the databases tend to focus solely on health-related impacts (such as Pub Med and Clinical queries) which may skew the results to include more health-focused output, the other search engines and even the more heavily saturated “health”-oriented search databases did pull in journal articles that considered the impacts of assistive technology on other sectors such as housing, education, and job participation. The general search string which consisted of an assistive technology term (either general assistive technology or the specific AT device selected from the priority list), and an evaluative term (such as cost-benefit analysis) should have pulled in the majority of relevant publications to give a fairly representative sample of journal articles that seek to assess the economic value of AT devices. However, the authors are aware that such a search strategy may not be comprehensive enough to fully capture the entirety of the AT literature, especially when it comes to particular AT devices or very unique evaluation methods. In particular a more robust gray literature search should be conducted in the future to capture gray literature outside the few select locations scouted and chosen.

Conclusion

The goal of this paper was to demonstrate the multifaceted techniques and methods that are currently being used to capture AT value globally. Through this process it has become clear that within this literature there is evidence that AT offers value, but the studies conducted are only of moderate evidence strength and further the methodologies and tools employed to capture value are found wanting. The paper has synthesized and analyzed existing AT evaluation techniques and has highlighted some of the most common types of methods used to assess value along with capturing what are the most common perspectives in which AT value is understood. AT value is often understood in terms of how access and utilization of AT alleviate the cost and burden of the care network, whether this is through reductions in time family carers are required to assist users, or decreases in care costs through reduced time and resources expended.

This paper advocates both for a wider user of alternative evaluation and appraisal methodologies, as well as a synthesis of a mixture of different techniques. We recognize the CBA, CUA and CEA will not be abandoned, but rather they should be complemented by other measurements that embrace value which are difficult to monetize, such as wellbeing or AT innovation ecosystems. By promoting such alternative forms of evaluation this study hopes to provide a path forward for LMICs who currently have difficulty in prioritizing AT due to financial constraints and lack understanding of the manifold impacts of AT. Through a wider breadth of AT evaluations within the research domain, a more robust evidence base will enhance global awareness of AT value and its need to be prioritized.

Notes

1 WHO. (2021) Priority Assistive Products List. Improving access to assistive technology for everyone, everywhere. “WHO_EMP_PHI_2016.01_eng.Pdf”. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/207694/WHO_EMP_PHI_2016.01_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

2 Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

3 Measure of overall disease burden. Developed in 1990s as a way of comparing the overall health and life expectancy of different countries.

4 Unlike DALYS, QALYS only measure the benefit without and without medical intervention and do not measure total burden. QALY tend to be used more often as an individual verses a societal measure.

5 The Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology evaluates a patient’s satisfaction with various assistive technologies. It assess activities of daily living by capturing patient reported outcomes.

6 Andrich, Renzo (2002). “The SCAI Instrument: Measuring Costs of Individual Assistive Technology Programmes”: 95– 99.

References

- Al-Oraibi, S., Fordham, R., & Lambert, R. (2012). Impact and economic assessment of assistive technology in care homes in Norfolk, UK. Journal of Assistive Technologies, 6(3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17549451211261317

- Andrich, R. (2002). The SCAI instrument: Measurement costs of individual assistive technology programmes. Technology and Disability, 14(3), 95–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/TAD-2002-14303

- Andrich, R., Ferrario, M., & Moi, M. (1998). A model of cost-outcome analysis for assistive technology. Disability & Rehabilitation, 20(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638289809166850

- Brodin, H., & Persson, J. (1995). Cost-utility analysis of assistive technologies in the European commission’s tide program. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 11(2), 276–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462300006899

- Harding,S. (1995). Thought make economics more objective? Feminist Economics, 1(1), 7–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/714042212

- Demers, L., Weiss-Lambrou, R., & Ska, B. (1996). Development of the Quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST). Assistive Technology, 8(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.1996.10132268

- Dequech, D. (2007). Neoclassical, mainstream, orthodox, and heterodox economics. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 30(2), 279–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PKE0160-3477300207

- Deruyter, F. (1995). Evaluating outcomes in assistive technology: Do we understand the commitment? Assistive Technology, 7(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.1995.10132246

- Drummond, M., O’Brien, B., Stoddart, G., & Torrance, G. (1997). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes (2nd ed.). Oxford University Publication.

- Drummond, M. F., Brandt, A., Luce, B. R., & Rovira, J. (1993). Standardizing economic evaluation methodologies in health care. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 9(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462300003007

- Fuhrer, M. J. (2001). Assistive technology outcomes research: Challenges met and yet unmet. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80(7), 528–535. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-200107000-00013

- Fuhrer, M. J. (2007). Assessing the efficacy effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of assistive technology interventions for enhancing mobility. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 2(3), 149–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100701374355

- Galvin, J. C., & Scherer, M. J. (1996). Evaluating, selecting and using appropriate assistive technology. Aspen Publishers, Inc.

- Gelderblom, G. J., & de Witte, L. P. (2002, January). The assessment of assistive technology outcomes, effects and costs. Technology and Disability, 14(3), 91–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/TAD-2002-14302

- Goldman, L., Garber, A., Grover, S., & Hlatky, M. (1996). Cost effectiveness of assessment and management of risk factors. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 27, 1020–1030.

- Harris, F., & Sprigle, S. (2003). Cost analyses in assistive technology research. Assistive Technology, 15(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2003.10131886

- Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons.

- Holm, M. B. (2000). Our mandate for the new millennium: Evidence-based practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2000(54), 575–585. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.54.6.575

- Jacobs, P., Hailey, D., & Jones, A. (2003). Economic evaluation for assistive technology policy decisions. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 14(2), 120–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073030140021001

- Kattel, R. (2020). Alternative policy evaluation frameworks and tools. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy.

- Kattel, R., Mazzucato, M., Ryan-Collins, J., & Sharpe, S. (2018). The economics of change: Policy appraisal for missions, market shaping and public purpose. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2018-06).

- Lansley, P., McCreadie, C., & Tinker, A. (2004). Can adapting the homes of older people and providing assistive technology pay its way? Age and Ageing, 33(6), 571‐6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh190

- Mann, W. C., Ottenbacher, K. J., Fraas, L., Tomita, M., & Granger, C. V. (1999). Effectiveness of assistive technology and environmental interventions in maintaining independence and reducing home care costs for the frail elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Family Medicine, 8(3), 210‐7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archfami.8.3.210

- Manns, P. J., & Darrah, J. (2006). Linking research and clinical practice in physical therapy: Strategies for integration. Physiotherapy, 92(2), 88–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2005.09.006

- Marasinghe, K. M., Lapitan, J. M., & Ross, A. (2015). Assistive technologies for ageing populations in six low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMJ Innovations, 1(4), 4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2015-000065

- Nelson, R., & Winter, S. (1974). Neoclassical vs evolutionary theories of economic growth: Critique and prospectus. The Economic Journal, 84(336), 886–905. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2230572

- Schraner, I., de Jonge, D., Layton, N., Bringolf, J., & Molenda, A. (2008). Using the ICF in economic analyses of assistive technology systems: Methodological implications of a user standpoint. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(12–13), 916–926. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701800293

- Schüler, E., Salton, B. P., Sonza, A. P., Façanha, A. R., Cainelli, R., Gatto, J., Kunzler, L., & Araújo, M. D. C. C. (2013). Production of low cost assistive technology. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Management of Emergent Digital EcoSystems, 297–301. MEDES ’13. Association for Computing Machinery.

- Shin, J., Kim, Y., Nam, H., & Cho, Y. (2016). Economic evaluation of healthcare technology improving the quality of social life: The case of assistive technology for the disabled and elderly. Journal of Applied Economics, 48(15), 1361–1371. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2015.1100254

- Smith, R. O. (1996). Measuring the outcomes of assistive technology: Challenge and innovation. Assistive Technology, 8(2), 71–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.1996.10132277

- Stovold, E., Beecher, D., Foxlee, R., & Noel-Storr, A. (2014). Study flow diagrams in Cochrane systematic review updates: An adapted PRISMA flow diagram. Systematic Reviews, 3(1), 54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-54

- WHO. (2019). Provision of wheelchairs in Tajikistan: Economic assessment of alternative options. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312049/9789289054041-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&ua=1

- World Health Organization. (2014). Opening the gate for assistive health technology: Shifting the paradigm. Secondary Opening the gate for assistive health technology: Shifting the paradigm. http://www.aaate.net/sites/default/files/gate_concept_note_for_circulation.pdf

Appendix.

Studies included in economic evaluation assessment and review

Scoping Review References

Brent 2019 (USA) [1]

Brent, R. J. (2019) ‘A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Hearing Aids, Including the Benefits of Reducing the Symptoms of Dementia’. Applied Economics 51, no. 28: 3091–3103.

Andrich et al., 1998 (Europe) [3]

Andrich R, Ferrario M, and Moi M. (1998) ‘A Model of Cost-Outcome Analysis for Assistive Technology.’ Disability & Rehabilitation 20, no. 1: 1–24.

Salatino et al., 2016 (Italy) [4]

Salatino C, Andrich R., Converti M, and Saruggia M. (2016) ‘An Observational Study of Powered Wheelchair Provision in Italy’. Assistive Technology: The Official Journal of RESNA 28, no. 1: 41–52.

Andrich & Caracciolo 2007 (Italy/Europe) [5]

Andrich, R. Caracciolo A. (2007) ‘Analysing the Cost of Individual Assistive Technology Programmes’. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology 2, no. 4: 207–34.

Lansley et al., 2004 (England and Scotland) [12]

Lansley P, McCreadie C, and Tinker A. (2004) ‘Can Adapting the Homes of Older People and Providing Assistive Technology Pay Its Way?’ Age and Ageing 33, no. 6: 571–76.

Allen 2001 (USA) [13]

Allen, S. M. (2001) ‘Canes, Crutches and Home Care Services: The Interplay of Human and Technological Assistance’. Policy Brief (Center for Home Care Policy and Research (U.S.)), no. 4: 1–6.

Duff & Dolphin 2007 (England, Ireland, Finland, Norway) [19]

Duff, P., and Dolphin C. (2007) ‘Cost-Benefit Analysis of Assistive Technology to Support Independence for People with Dementia - Part 2: Results from Employing the ENABLE Cost-Benefit Model in Practice’. Technology and Disability 19, no. 2–3: 79–90.

Monksfield et al., 2011 (UK) [21]

Monksfield P, Jowett S, Reid A, and Proops D. (2011) ‘Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of the Bone-Anchored Hearing Device’. Otology & Neurotology : Official Publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 32, no. 8: 1192–97.

Hagberg et al., 2017 (Sweden) [22]

Hagberg L, Hermansson L, Fredriksson C, and Pettersson I. (2017) ‘Cost-Effectiveness of Powered Mobility Devices for Elderly People with Disability’. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology 12, no. 2: 115–20.

Leroi et al. 2013 (UK) [29]

Leroi I et al. (2013) ‘Does Telecare Prolong Community Living in Dementia? A Study Protocol for a Pragmatic, Randomised Controlled Trial’. Trials 14: 349.

Shin et al., 2016 (Korea) [31]

Shin J., Kim Y, Nam H, and Cho Y. (2016) ‘Economic Evaluation of Healthcare Technology Improving the Quality of Social Life: The Case of Assistive Technology for the Disabled and Elderly’. Applied Economics 48, no. 15: 1361–71.

Mann et al., 1999 (USA) [34]

Mann W. C., Ottenbacher K.J., Fraas L, Tomita M, and Granger C.V. (1999) ‘Effectiveness of Assistive Technology and Environmental Interventions in Maintaining Independence and Reducing Home Care Costs for the Frail Elderly. A Randomized Controlled Trial’. Archives of Family Medicine 8, no. 3: 210–17.

Cooper et al., 1999 (USA) [38]

Cooper R. A., Boninger M. L., and Rentschler A. (1999) ‘Evaluation of Selected Ultralight Manual Wheelchairs Using ANSI/RESNA Standards’. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 80, no. 4: 462–67.

Al‐Oraibi et al., 2012 (UK) [44]

Al‐Oraibi S, Fordham R, and Lambert R. (2012) ‘Impact and Economic Assessment of Assistive Technology in Care Homes in Norfolk, UK’. Journal of Assistive Technologies, 7 September.

Desideri 2016 (Italy) [45]

Desideri L et al. (2016) ‘Implementing a Routine Outcome Assessment Procedure to Evaluate the Quality of Assistive Technology Service Delivery for Children with Physical or Multiple Disabilities: Perceived Effectiveness, Social Cost, and User Satisfaction’. Assistive Technology: The Official Journal of RESNA 28, no. 1: 30–40.

Noben et al., 2017 (Netherlands) [46]

Noben C, Evers S, van Genabeek J, Nijhuis F, and de Rijk A. (2017) ‘Improving a Web-Based Employability Intervention for Work-Disabled Employees: Results of a Pilot Economic Evaluation’. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology 12, no. 3 : 280–89.

Samuelsson & Wressle 2014 (Sweden) [53]

Samuelsson K, and Wressle E (2014). ‘Powered Wheelchairs and Scooters for Outdoor Mobility: A Pilot Study on Costs and Benefits’. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology 9, no. 4: 330–34.

Bray et al., 2016 (UK) [54]

Bray N, Yeo ST, Noyes J, Harris N, and Edwards RT. (2016) ‘Prioritising Wheelchair Services for Children: A Pilot Discrete Choice Experiment to Understand How Child Wheelchair Users and Their Parents Prioritise Different Attributes of Wheelchair Services’. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 2 (2016): 32.

Ekman & Borg 2017 (Bangladesh) [55]

Ekman B, and Borg J. (2017) ‘Provision of Hearing Aids to Children in Bangladesh: Costs and Cost-Effectiveness of a Community-Based and a Centre-Based Approach’. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology 12, no. 6: 625–30.

Vincent et al. 2006 (Canada) [56]

Vincent C et al. (2006) ‘Public Telesurveillance Service for Frail Elderly Living at Home, Outcomes and Cost Evolution: A Quasi Experimental Design with Two Follow-Ups’. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 4: 41.

Creasey et al., 2000 (USA) [57]

Creasey G. H., et al. (2000) ‘Reduction of Costs of Disability Using Neuroprostheses’. Assistive Technology: The Official Journal of RESNA 12, no. 1 (2000): 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2000.10132010.

Aanesen et al., 2011 (global) [59]

Aanesen, M., Lotherington A, and F. Olsen. (2011) ‘Smarter Elder Care? A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Implementing Technology in Elder Care’. Health Informatics Journal 17, no. 3: 161–72.

Hutchinson et al., 2020 (Australia) [64]

Hutchinson C, et al. (2020) ‘Using Social Return on Investment Analysis to Calculate the Social Impact of Modified Vehicles for People with Disability’. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal.

Schulz et al., 2014 (USA) [67]

Schulz R et al. (2014) ‘Willingness to Pay for Quality of Life Technologies to Enhance Independent Functioning among Baby Boomers and the Elderly Adults’. The Gerontologist 54, no. 3: 363–74.

Riikonen et al., 2010 (Finland) [68]

Riikonen M T, Mäkelä K., Perälä S. (2010). Safety and monitoring technologies for the homes of people with dementia. Gerontechnology 9(1)

WHO 2017 (Tajikistan) [69]

WHO (2017). Provision of Wheelchairs in Tajikistan: Economics Assessment of Alternative Options. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe.

Baltussen & Smith. 2009 (sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia) [70]

Baltussen, R., and Smith. A (2009) ‘Cost-Effectiveness of Selected Interventions for Hearing Impairment in Africa and Asia: A Mathematical Modelling Approach’. International Journal of Audiology 48, no. 3 (1 January 2009): 144–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020802538081.

Baltussen & Smith. 2012 (sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia) [71]

Baltussen, R., and A. Smith. (2012) ‘Cost Effectiveness of Strategies to Combat Vision and Hearing Loss in Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: Mathematical Modelling Study’. BMJ 344, no. Mar02 1: e615–e615.

Croock Associates 2015 (Rwanda) [72]

Croock Associates (2015). Primary Eye Care Services in Rwanda: Benefits and Costs. Commissioned by Vision for a Nation Foundation.

WHO 2017 (global) [73]

WHO (2017). Global costs of unaddressed hearing loss and cost-effectiveness of interventions. WHO Global Report.

Healy 2018 (Australia, Canada, Germany, Netherlands, UK, USA) [74]

Healy A, Farmer S, Pandyan A, and Chockalingam N (2018) ‘A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials Assessing Effectiveness of Prosthetic and Orthotic Interventions’. PloS One 13, no. 3.

Persson et al., 2008 (Sweden) [75]

Persson J, Aelinger S, Husberg M (2008) Kostnader och effekter vid förskrivning av hörapparat. CMT Rapport (5)

Persson et al., 2007 (Sweden) [76]

Persson J, Husberg M, Hellbom G, Fries A. (2007) Kostnader och effekter vid förskrivning av rollatorer (3)

Aanesen 2009 (Norway) [77]

Aanesen M (2009) LothNy teknologi i pleie og omsorg: en kost – nytteanalyse av smarthusteknologi og videokonsultasjoner. Norut Rapport 5

Socialstyrelsen 2013 (Denmark) [78]

Socialstyrelsen. (2013) Smarthometeknologi. https://socialstyrelsen.dk/filer/tvaergaende/hjaelpemidler-og-velfaerdsteknologi/smarthome-analyse.pdf

Dahlberg 2013 (Sweden) [79]

Dahlberg (2013). Nyttokostnadsanalys vid införande av välfärdsteknologi– exemplet Posifon. Hjälpmedelsinstitutet.

Hannerz 2013 (Sweden) [80]

Hannerz (2013). Utvärdering av projekt Förskrivning av larm i Östersund- ekonomi och process. https://docplayer.se/3797329-Utvardering-av-projekt-forskrivning-av-larm-i-ostersund-ekonomi-och-process-ostersund-2013-01-03.html

Griffiths 2014 (Zambia) [81]

Griffiths, UK (2014) ‘Cost-Effectiveness of Eye Care Services in Zambia’. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 12, no. 1: 6.

Dahlberg 2012 (Sweden) [82]

Dahlberg Å (2012), Nyttokostnadsanalys vid införande av välfärdsteknologi – exemplet ippi. Hjälpmedelsinstitutet.

Dahlberg 2010 (Sweden) [83]

Dahlberg Å (2010), Kostnadsnyttobedömning av hjälpmedel till personer med psykisk funktionsnedsättning, Hjälpmedelsinstitutet.

Lund 2010 (Sweden) [84]

Lundmark 2013 (Sweden) [85]

Lundmark EN, Nilsson I, Wadeskog A (2013) Teknikstöd i skolan – Socioekonomisk analys av unga, skolmisslyckanden och arbetsmarknaden. Hjalpmedelsinstitutet