Abstract

Phenomenon: This study explores professional identity formation during a final year of medical school designed to ease the transition from student to practitioner. Although still part of the undergraduate curriculum, this “transitional year” gives trainees more clinical responsibilities than in earlier rotations. Trainees are no longer regarded as regular clerks but work in a unique position as “semi-physicians,” performing similar tasks as a junior resident during extended rotations. Approach: We analyzed transcripts from interviews with 21 transitional-year medical trainees at University Medical Center Utrecht about workplace experiences that affect the development of professional identity. We used Social Identity Approach as a lens for analysis. This is a theoretical approach from social psychology that explores how group memberships constitute an important component of individual self-concepts in a process called ‘social identification.’ The transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis, with a focus on how three dimensions of social identification with the professional group emerge in the context of a transitional year: cognitive centrality (the prominence of the group for self-definition), in-group affect (positivity of feelings associated with group membership) and in-group ties (perception of fit and ties with group members). Findings: Students were very aware of being a practitioner versus a student in the position of semi-physician and performing tasks successfully (i.e., cognitive centrality). Students experienced more continuity in patient care in transitional-year rotations than in previous clerkships and felt increased clinical responsibility. As a semi-physician they felt they could make a significant contribution to patient care. Students experienced a sense of pride and purpose when being more central to their patients’ care (i.e., in-group affect). Finally, in extended rotations, the trainees became integrated into daily social routines with colleagues, and they had close contact with their supervisors who could confirm their fit with the group, giving them a sense of belonging (i.e., in-group ties). Insights: Using the three-dimension model of social identification revealed how students come to identify with the social group of practitioners in the context of a transitional year with extended rotations, increased clinical responsibilities, and being in the position of a “semi-physician.” These findings shed light on the identity transition from student to practitioner within such a curricular structure.

Introduction

The transition from student to practitioner is critical for medical trainees and is marked by increased responsibilities in patient care.Citation1 Graduation from medical education is not just completion of academic study but leads to membership in a group licensed for special privileges and responsibilities and to a prestigious new identity. Becoming a member of such a new group and preparing for it can be stressful.Citation2–4 Medical schools and educators have been trying to find ways to ease that transition.Citation5,Citation6 In the UK, the General Medical Council has decreased the length of undergraduate education from 6 to 5 years and introduced a mandatory 2-year ‘foundation program’ before postgraduate training. In the USA, medical graduates first have an intern year before they are designated as ‘residents.’ In the Netherlands, medical schools have been paying special attention to this transition in curricular reforms since the turn of the century. One intervention to ease it has been the restructuring of the final year as a “transitional year,”Citation7,Citation8 with several characteristics (see Box 1).

The effect of a such a transitional year on transition to postgraduate education has been studied with a focus on preparedness for work, career choice, and residency programs.Citation9,Citation10 A transitional year may also support the transformation of one’s professional identity in moving from medical student to medical doctor.Citation11,Citation12 The focus of this study is on this profound shift in identity. Because professional identity is linked to the professional behavior, career success and psychological health of medical professionals,Citation13–15 it is important to understand trainees’ identity development during such a transition.

Professional identity formation can be understood from various theoretical perspectives.Citation16 Social Identity Approach (SIA), whose relevance for research on professional identity formation in medical education has been described before,Citation17 provides a social perspective to identity formation while still accounting for the individual psychological processes involved. SIA encompasses two intertwined theories, which share key assumptions. The first is Social Identity Theory (SIT), originating in the early 1970s and further developed by its creator, social psychologist Henri Tajfel, in subsequent decades.Citation18 SIT posits that in many social situations people think of themselves and others as group members rather than as unique individuals, and it explains how doing so affects their thinking and behavior in accordance with group values and norms. The constituent theory of SIA is Self-Categorization Theory (SCT), developed by Tajfel’s colleague John Turner in the 1980s.Citation19 It elaborates on the cognitive process that results in group-level conceptions of the self and others rather than individual-level conceptions. Specifically, it deals with the psychological mechanisms that make individuals define themselves in terms of particular group memberships and act accordingly.

Importantly, SIA posits that individuals incorporate social category membership into their self-concept or “social identity.” In Tajfel’s words, social identity is “… that part of the individuals’ self-concept which derives from their knowledge of their membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership.”Citation20(p2) As a result of social identification, individuals come to perceive themselves as belonging to in-groups, as opposed to out-groups. Every individual holds a mental representation of the social groups to which he or she belongs. In this way, SIA addresses identity development at the level of social group memberships, relevant for our aim of exploring a trainee’s shift in identifying with the one group (medical students) to identifying with another (medical practitioners). In the process of becoming a physician (i.e., adopting a medical professional identity), individuals integrate this group membership into their social identity.

Since SIAs development, many researchers in various domains have used it to further conceptualize the construct of social identification. It is assumed that social identification includes multiple dimensions.Citation21 For this study we use the dimensions distinguished in the three-factor model of social identification suggested by Cameron,Citation22 as this model stays close to Tajfel’s definition of social identity.Citation20 These dimensions are as follows:Citation22,Citation23

Cognitive centrality. This is the cognitive awareness and prominence of one’s group membership. It can be conceptualized as the frequency with which group membership comes to mind and the subjective importance of the group to one’s self-image. This concept is closely linked to a central element of the SCT, category salience. Category salience can be explained as the readiness of a given group membership to be activated to serve as sources of self-definition at a specific moment.Citation24 A self-category is more likely to be activated if it has frequently or recently been activated,Citation25 and in that way may gain a more enduring cognitive prominence for the individual. In such cases, social identification can be said to be relatively central.

In-group affect: This is the dimension of social identification concerning one’s emotional evaluation of group membership, with either positive or negative emotions. For example, one can feel proud to belong to a highly valued group or ashamed when belonging to a devalued group.Citation26

In-group ties: This dimension refers to one’s emotional involvement with or psychological ties to the group and to one’s perception of similarity to and bonds with group members. It is operationalized as a sense of connectedness with other group members, “a sense of belonging with the group,” a perception that one “fits in,” “has strong ties,” or “shares a common bond” with the group and its members.Citation22

In this project we apply SIA as a lens to study professional identity formation with the aim of exploring how the three above-mentioned dimensions of social identification emerge in the context of a transitional year. Using SIA, and exploring identity formation in the sense of self-categorizing as a member of the professional group, the results of this study can extend our knowledge of medical trainees’ professional identity development to include a social perspective. The focus on the transition from student to practitioner may offer insight into how to provide effective support during this stage of medical training.

Methods

This qualitative study was conducted using transcripts of semi-structured interviews analyzed using thematic analysis from an interpretivist worldview.Citation27 Using SIA, we see identity development as a process in which identities are created and co-created within a social world but represented in the minds of individuals.Citation16

Context

Our study was conducted at Utrecht University medical school, a Dutch medical school that implemented a transitional year, as described in the introduction, in 2004. In The Netherlands, medical school programs last 6 years and can be entered directly following secondary school.Citation7 The Utrecht University medical school has a curriculum with regular clinical block rotations and several electives in years 3–5 that prepare learners for the final transitional year.Citation8 During the mandatory transitional year all trainees must take, in varying order, a 12-week major clinical elective at a department of their choice, a 12-week research elective at a department of their choice, and a 12-week block to fill in at a clinical, science, or other department they choose.

During the transitional year trainees are called ‘semi-physicians’ (literal translation of the Dutch term), a label used in our school and other Dutch schools for students in this stage of training. Semi-physicians’ work is similar to that in sub-internships or acting internships in US medical schools or that in the first foundation year in the UK, and it approaches the level of a starting medical practitioner. The duration of transitional year rotations (12 weeks) is longer than those in the preceding clerkships (∼6 weeks at the time of this study). This allows for continuity in both patient care and supervision.Citation28

After successful completion of the transitional year, students obtain their medical degree and license. Many graduates first work as a junior clinical doctor before applying for residency training. The Netherlands has no national matching system for residency selection, and graduates must apply for a position in an open job market. More detailed descriptions of the Utrecht medical school curriculum and its transitional year have been published elsewhere.Citation8,Citation29

Population

Students can start the transitional year program at several times during a year. We invited all 67 students who started the transitional year between May and October 2014 to participate in an interview study. We explained the project during teaching sessions and then invited students via email. We included all who volunteered to participate.

Reflexivity

The researchers in this project have backgrounds as medical doctors, medical educators, and medical education researchers. SvdB was trained medically in the same program as the research participants, but five years earlier. Her personal experiences were deliberately used when designing the project and interpreting the data. She conducted half of the interviews and had a central role in data analysis. SQ, at that time a policy advisor at the Royal Dutch Medical Association, represented an outsider point of view and conducted the other half of the interviews. MWM, an educational scientist, and SQ contributed to the rigor of the study by conducting iterative checks on the data analysis carried out by SvdB. MWM, MvD and OtC are experienced medical educators, involved in teaching in the transitional-year program. OtC was instrumental in introducing the transitional year in Dutch medical schools, and MWM studied effects of the transitional year as a PhD research topic. MWM, MvD, and OtC were not involved with data collection, but had access to de-identified data.

Data collection

Data were collected via semi-structured interviews conducted at the start and end of the transitional year for two purposes: (1) to explore significant workplace experiences during the transitional year and how these influenced professional identity development of the medical trainees, and (2) to uncover factors that specifically influence medical students’ career choice.Citation30 The interview guide, translated from Dutch to English, is included in Appendix A. For the present study, which is part of the larger project about identity development, we analyzed the interviews conducted at the end of the transitional year, around the date of graduation. All interviews lasted about one hour. Summaries of the transcripts were sent to the interviewee to verify whether they reflected their views and experiences correctly. Only minor textual corrections were returned.

Analysis

In a first round of data analysis, interview transcripts were coded line by line in an open coding process, followed by axial coding to identify main themes. SvdB analyzed all transcripts, and SQ and MWM analyzed a subset of the data for analytical rigor purposes. Findings were discussed with all members of the research team. This led to a phase of theory exploration to enhance the understanding of the identified themes. The literature on professional identity formation was revisited, and a strong match was found between the themes we identified and SIA. In a new round of analysis, interview transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis,Citation31 with knowledge of SIA providing guidance.

In this round, analysis was performed by SvdB and MWM and consisted of three phases. In the first phase, all data were analyzed using the three dimensions of social identification (cognitive centrality, in-group affect and in-group ties) as a lens. A set of six interviews was used for preliminary coding. We then further analyzed the interview transcripts using this coding scheme, pausing to modify the scheme after each reading of three to four new transcripts. New codes were discussed and inserted, and existing ones were redefined until all relevant data were coded. SvdB completed this phase by applying the resulting revised coding scheme to the full data set.

In the second phase, all data segments relevant to social identification were coded again, this time with an initial coding template based on the transitional-year characteristics as listed in Box 1 [excluding the fourth characteristic (elective choices) as it is not related to students’ daily experiences during the rotations]. A code for items that had “no link with transitional-year characteristics” was added, as we discovered data extracts that could be linked to dimensions of social identification but were not bound to a transitional-year characteristic. SvdB then coded the full data set, while MWM analyzed subsets of data during several steps and discussed findings in detail with SvdB. During this phase, the earlier coding for social identification was concealed.

In the third phase, we generated an overview of the co-occurrence of codes from both coding schemes (social identification and transitional-year characteristics), identified themes and subthemes at the interpretative level and discussed their relationships to understand the data in relation to our research question.

During all steps there was input from other members of the research team via discussion and interpretation of findings and definition of further steps in data analysis. We used Dedoose® version 7.6.6 to support our data analysis.Citation32 Extracts were translated from Dutch for this publication.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this project was obtained from The Netherlands Association for Medical Education Ethical Review Board (NERB dossier number 333).

Results

Twenty-two trainees participated in the interviews at the end of the transitional year. One of these interviews was not recorded due to technical problems, yielding 21 interview transcripts. The interviewees ranged in age from 24 to 27 years; 17 were female, reflecting an overrepresentation of females, although the medical school does have more female than male medical students. In the interviews, trainees elaborated on transitional year experiences they found significant or remembered as being particularly impactful, and how these contributed to or lessened their sense of being a doctor.

The cognitive centrality dimension – working with increased clinical responsibility as a semi-physician

During the transitional year, clinical work triggered students’ awareness of feeling like a practitioner, including increased responsibilities in patient care and altered relationships with junior clerks and supervisors. In the interviews, students were asked about, or spontaneously mentioned, moments when they were aware of feeling more like a doctor than a student. For example:

Well, [when I was a semi-physician] I worked much more independently […] I succeeded much better than I had anticipated in getting a clear picture of patients and their problems. And in creating a management plan, and getting it all organized. That went really well. One evening shift […] attendings were called for a cesarean section while there were still six other patients either on the ward or at the ER. I went to see these other patients while they [were busy] and later we discussed them, and then [my supervisor] said like “Okay, I agree, that is a good idea.” That really made me think, “Wow, okay, I apparently act as a doctor quite well”. - Student 10, female

Increased clinical responsibility is an important characteristic of the transitional year. Via ‘full tasks’ in patient care, trainees are responsible (albeit under strict supervision) for every step of a patient consultation or a patient’s hospital admission, including designing a treatment plan, communicating with the patient, consulting other professionals, and completing administration and documentation procedures. Like the student quoted above, other interviewees described clear moments during their rotations when performing these clinical tasks made them aware of being a doctor:

[What else made you be more of a doctor?]

[…] that they trusted me to do almost everything independently […], such as relying on my judgment and having me arrange things with other doctors, consulting other doctors. - Student 8, female

I had my own patients, my own consulting room. I really felt like a doctor. - Student 13, male.

In contrast, when trainees were placed back in the role of a student (for example, being limited to observing or performing only very selective clinical tasks such as taking a history) they would not experience such feelings of identity, and some even reported a diminished sense of being a doctor, as did the student in the following passage:

My final rotation this year was disappointing […], due to how this department assumed my role. I had just finished another semi-physician rotation and really felt like I was a doctor. I could do so much in patient care. That boosted my confidence. I think I could have been a resident in that department. But in this final rotation I felt like I was starting from scratch. […] None of my own patient consultations, no responsibilities. In fact, I started skipping clinic at times and no-one would even notice! That was truly disappointing. – Student 8, female

In the position of semi-physician, trainees experience a new hierarchical position relative to supervisors, colleagues, and more junior trainees. Semi-physicians may consult other professionals themselves instead of having their supervisors do that. In most cases, semi-physicians are supervised directly by senior staff members, while clerks are supervised by junior doctors:

[You said it was the first time you felt like becoming a doctor. Can you explain what happened to you?]

Well, it is the responsibility you have […] When things happen, you need to call the senior staff member yourself, not someone between you and the senior staff. It’s more kind of real. - Student 11, female.

And semi-physicians may sometimes supervise junior clerks, as this trainee did:

[Can you think of a pivotal moment when you realized ‘I’m a doctor and not a student’?]

Yes. In the penultimate week of my [semi-physician] rotation on the internal medicine ward. This hospital also has clerks [who are junior by one year]. Initially I felt insecure, anticipating they wouldn’t have much less background knowledge. But on a ward round with one clerk I noticed how I had progressed. We rounded my patients, about nine, one of which was assigned to her. I found myself teaching her about dull thorax percussion signs and bronchial abnormalities. This experience made me suddenly think, “Wow, so this is how an attending acts. Now I feel like a doctor.” That was really nice to notice. – Student 14, male

These quotes illustrate how interviewees described their experience being in the position of a semi-physician as a position similar to a starting doctor. They felt more like a medical practitioner than a clerk.

The in-group affect dimension – contributing to patient care

Most students experienced strong positive feelings when they were able to help and support patients. These moments were remembered as significant to their sense of feeling like a doctor.

[Can you describe moments during your semi-physician rotation when you had the feeling of being a doctor and not a student anymore?]

At the start of my semi-physician rotation, there was a delirious patient with a fever. […] It was at the start of my rotation, and I did not have a lot of patients to take care of yet, and I spent much of my time on this patient’s case. He was transferred to the ICU. When I visited him one afternoon at the ICU, his family was there. I took time to talk to them. I wanted to know how he was doing and I thought about the family being shocked by all that happened. So I went there to talk to them, taking care everything was clear to them. And then, when they left, I sensed they felt grateful I was there for them, that I did not leave them alone, but that they had someone who was there and could explain treatment plans and things to them. That is something that stays with me. – Student 20, male

A moment of impact was when I passed the room of one of my patients who had an end-stage malignancy. […] He had always been fairly cheerful when I visited him during morning rounds. But when I passed by his room now, I saw something was wrong and stood still. He was in his bed […] and I sat next to him. He cried briefly when I was there. I was touched. It is one of these moments you can’t do anything, but in fact you can. […] And I felt grateful, for experiencing that moment and grateful to be able to be there for this patient. – Student 14, male

In these examples, students as semi-physicians were able to see patients and contribute to their care longitudinally through different stages in the development of a disease. Their engagement with the patient’s case allowed them to be there for them and their families at difficult moments. Students also described how observing the effects of the care they played part in and experiencing patients’ gratitude led to positive feelings:

There was this patient who had been on my [psychiatry] ward months before, who came back for his psychotherapy. And we accidently met in the hallway, and he told me he wanted to speak to me. […] He had some questions about a program I introduced him to, but he also wanted to tell me how satisfied he was with the treatment at the ward, and how much it helped him. […] Another time I had attended a woman who had been admitted for a depression. […] a few weeks later I accidently met her in the hallway. She looked so happy […]. Wonderful to see how patients benefit from what we do […] it strikes me that these patients are happy to see me and want to thank me, I find that so flattering. To me it is a sign that I apparently did well. – Student 2, female

This immersion in the core business of practitioners seemed to make participants experience the value of being in this professional group. Participants also described how they highly respect the social group of doctors:

When I visit the OR I see the surgeons at work. They use robotics in esophagus surgery - gigantic operations up to six hours. That we can actually do this, it feels superhumanly. – Student 18, female.

This respect was usually related to the ability of physicians to make a significant contribution to people’s health and to have an important supportive role in times of illness.

The in-group ties dimension – contact with supervisors and colleagues

Students’ roles during the transitional year made them relate differently to supervisors and other health professionals. They felt more like being a colleague, triggering feelings of being a doctor. In most cases trainees were directly and longitudinally supervised by a senior staff member, and this contact with their supervisors was described as more intensive.

I had a great rotation in the ICU and the head of the department acted as a personal Counselor for me; we got along really well. I had never had a connection that felt so honest with someone working in the hospital. […] it all felt very natural. He was really enthusiastic about me. He said: “You are doing pretty good. You seem at ease here”. And that is how I felt as well. Every day I came home and I thought: “Yes, this is what I really like.” And then he asked me to apply at his unit after graduation. – Student 6, female

As evident in this example, some participants described a special connection with their supervisors. They described them as mentors and role models whom they observed as a source of prototypical behavior and traits for their professional group. Trainees gauged whether they shared these behaviors and traits, i.e., whether they were or could be ‘the same type of person’:

During my [senior clerkship] I worked with a supervisor who was a rather quiet man. […] With humor, but he knew what he was talking about … treating everyone friendly. Not dominant. I guess I can identify with him. Like he didn’t need to have the last say in everything. – Student 1, female

Supervisors also served as a source of feedback on fit with the professional group. They might tell the trainee directly that they saw a match with the group. In the quotes above, Student 6 even had her supervisor explicitly stating she ‘could belong to the group’ by encouraging her to apply for a job at his department. But just having a personal connection with a supervisor already seemed to be a confirmation of this fit for trainees:

I remember my supervisor - she truly was a role model […] When I left, she read a poem out loud for me. I’m not sure if that actually affected my image of a good doctor, but I thought: this is also a way to supervise people. That gesture really gave a special feeling. It made me feel very special there. – Student 8, female.

Finally, a theme frequently heard in the interviews was the significance of team membership. Over the course of the transitional year, participants reported feeling increasingly drawn in as an equal team member rather than a student.

[What has been a highlight for you this year?]

Significant was how I felt with the cardiology team. And the atmosphere at their grand rounds meetings. I don’t mean related to any medical content, actually. It was more… how I engaged with them. I was there for a longer period of time, and that makes a difference. It takes some time before you’re at ease in a rotation, and you are often gone again by then. But here I was really involved with the group. […] They were interested in who I was, and why I was interested in cardiology. They noticed I was enthusiastic. And they told me about themselves. I was treated as someone equal. – Student 21, female

I felt being part of a real team. That included psychiatry nurses and others; almost all also confirmed that they felt similarly. That was nice. – Student 8, female

Those residents were really nice among themselves. For the first time, I found myself being part of such a group. They were also kind of colleagues. In earlier rotations as a clerk, they treat you friendly but they… I don’t know, you are not part of their team. And now I was, that was really nice to notice, how it works having colleagues lunch together or, sometimes on Friday, to feel invited as a semi-physician to go along for a drink together. That atmosphere was great. It had an impact. – Student 11, female

The quotes above from the interviews with Students 21 and 8 describe the importance of being ‘treated as someone equal’ or of having it confirmed they were seen as someone who belongs to the team. The feeling of being treated as a colleague happened in work-related situations and in social situations, and was described as contributing especially strongly to the feeling of being a group member. The duration of rotations in the transitional year appeared not only to lead to continuity in supervision but also to continuity in relationships with other colleagues. Some described their earlier rotations as too short to get integrated in a team, such as Student 21 in the example above.

Discussion

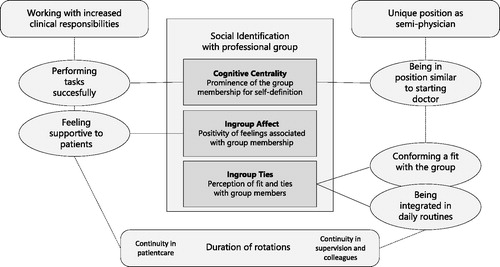

When relating transitional-year students’ experiences to dimensions of social identification and transitional-year characteristics, a pattern emerges () Working successfully with increased clinical responsibilities creates moments when students are aware of being a practitioner rather than a student. The role of semi-physician positions students hierarchically close or similar to a starting doctor, which prompts awareness of their transition from student to practitioner and makes identification as a doctor more salient in how trainees see themselves. Combined with successfully exercising increased clinical responsibilities, continuity in patient care allows students to experience the significant contributions they can make to patients’ care. This experience generates positive feelings like pride in being a doctor (i.e., an in-group member). Continuity in supervision and close contact with supervisors helps students observe whether they can be ‘the same type of person’ and to value highly the moments when supervisors confirm their fit with (i.e., ties to) the in-group. Students experience continuity in contact not only with supervisors but with other healthcare team members. They feel integrated in the teams as they are included in daily routines and in social activities. These social ties make them feel like a colleague and support their identification as an emerging doctor.

Our finding that feeling like a doctor emerges when students are challenged with greater patient care responsibilities resonates with findings from other studies of professional identity formation.Citation33,Citation34 Using SIA as a theoretical framework helps us understand trainees’ shift from identifying as students to identifying as practitioners in the context of a transitional year. Students who have had the experience of a near-doctor role are likely to experience the student role in a subsequent rotation as a setback and not conducive to learning. In our interviews, participants clearly identified situations in which they felt setback, i.e. assigned to ‘student’ tasks such as observing or shadowing, or in which they were not able to fulfill their expected role because tasks were too fragmented and there was no follow-up of patients.

Giving more clinical tasks alone may not have the same effect on social identification as a transitional year. In the Netherlands, we use the label of ‘semi-physician’ to signify students who are ready for increased responsibilities and en route to becoming a full physician. By clearly defining it as a unique stage in the learning continuum, the transition year encourages trainees to take on not only more responsibilities in patient care, but also a new position in relation to their supervisors, colleagues and more junior students. This resonates with an educational model called ‘Learning Oriented Teaching’Citation35 in which a desirable ‘constructive friction’ between teaching and learning is achieved when learners are challenged to perform with slightly less guidance than they might feel comfortable with. Destructive friction occurs when there is too little or too much guidance.Citation36 The position of semi-physician may bridge the gap between the guidance a trainee requires and gets as a ‘student’ and as a ‘practitioner’.

Not surprisingly, the increased clinical responsibility and the duration of the rotations in the transitional year allowed trainees in our study to follow up with patients through several stages of a hospital admission or illness progression.Citation28 Other studies have shown how students from longitudinal integrated clerkships are seen by patients as critical member of their care team.Citation37 In our results, we found trainees were more likely to notice their value as doctors when they fulfill this role. They described, although in many cases implicitly, how this made them feel grateful and proud, enhancing their in-group experience. In earlier rotations, trainees contributed to patient care, such as by taking a history and performing a physical examination, but limited rotation durations and a limited clinical responsibility may have precluded deep engagement that might result from following-up patients. There may be opportunities to stimulate the in-group affect dimension early in training.Citation38,Citation39 Yet, many medical curricula offer only rotations in which students shadow physicians at work. Our findings support earlier recommendations to give medical trainees the opportunities to perform low-complexity but significant tasks in direct patient care, and to have them participate in the community of practice.Citation39 Hospitals with only high-complexity patients may not be ideal from the perspective of social identification if no legitimate roles can be given to students.

Finally, we found that supervisors and other healthcare team members play an important role in students’ identity formation. The transitional-year curricular design appears not only to allow for continuity with supervisors but also for continuity with colleagues. Frequently mentioned by our interviewees as important to their identification as doctors was the feeling of being treated as a colleague by all members of the interprofessional group. Trainees may regard colleagues and supervisors not only as role models but also as points of comparison allowing the trainees to gauge the extent to which they fit with the professional group. However, supervisors and other healthcare team members may not always be aware of their significance for trainee identity development. Short block rotations with frequent transitions may hamper integration of students in teams. For the team, high student turnover hampers the ability to involve students and get to know them personally, which is a condition for entrusting students with critical patient care tasks.Citation40 Curriculum designs incorporating additional strategies for more extensive and intensive engagement during clerkship may be particularly helpful for this aspect of identity development.

Trainee perceptions of fit with the group appear to be based on short-lived experiences and seemingly small moments with large impact. Such experiences, important to identity formation for students, would not necessarily be recognized as remarkable by others.Citation34 To support students in their explorations of fit with the professional group, educators might consider encouraging conscious reflection on such experiences.

This study has limitations. It was performed in the context of the Dutch healthcare system and at one Dutch medical school. As always in qualitative research, caution is advised in transferring the results to other settings. The overrepresentation of female participants should be considered a limitation. However, the stories of the male students did not appear to describe a different process. We started data analysis with an inductive approach, and we stayed open to other interpretations when conducting the next phase of analysis with SIA as a framework. Still, by using a specific theoretical framework, there was a risk of overlooking meaningful themes when these did not fit the theory or a tendency to fit the data into the theory. We used conscious reflections on this aspect during data analysis to minimize this risk. Much of social identification happens unconsciously and is not easy to reveal, however, the interviews were not conducted with SIA as a framework in mind. This resulted in some data units in the interviews which could not be explored in greater depth; had the interviews been conducted with SIA in mind, such data units might have prompted requests from the interviewer for greater elaboration. We therefore consider our study a first exploration.

The transition from student to practitioner is a critical phase in medical training involving a major transformative process in trainees’ professional identity. Our exploration revealed how students come to identify with the social group of doctors in the context of a transitional year with a gradual increase in clinical responsibilities, having a position as semi-physician and continuity with patients, supervisors and colleagues. In our study we have specifically explored trainees’ experiences through the lens of SIA. This theory has proven its applicability in many domains and helped us to explain our own findings. Our results may inform medical educators interested in theoretical models of trainees’ professional identity development, as well as in curriculum developments aiming to ease transitions to next stages of training. The problem of ‘transfer’ from medical student to practitioner may be recognized in many places. Recently, general principles were described to support identity formation as an educational objective in medical education, including “providing faculty development, establishing and transmitting the cognitive base of knowledge of the subject, engaging students in the development of their own identity, providing a welcoming community, and assisting students as they follow the progress of their own identity development.”Citation41 Our results support these principles, and we propose to add a further one: reconsidering curricular structures to create clearly defined stages as to support professional identity formation.

Box 1. Features of the transitional year in 6-year Dutch medical school programs

Trainees have clinical responsibilities for the care of a limited number of patients comparable to junior residents.Citation8

Trainees are called ‘semi-physicians’ to distinguish them from 'students' in earlier clerkships.

Semi-physician rotations are relatively long (12 up to 18 weeks) allowing for continuity in patientcare and supervision.

Semi-physician rotations allow for a large variety of elective choice to meet student preferences.Citation29

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Carrie Chen, MD PhD, Manon Kluijtmans, PhD, Hanneke Mulder, PhD, Inge Pool, PhD, and Margot Weggemans, MD, for their comments on earlier versions of the manuscript, and Anneke van Enk, PhD, for her advice on language and formulations.

References

- Kilminster S, Zukas M, Quinton N, et al. Preparedness is not enough: understanding transitions as critically intensive learning periods. Med Educ. 2011;45(10):1006–1015. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04048.x.

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–451. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134.

- Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132–149. doi:10.1111/medu.12927.

- Teunissen PW, Westerman M. Junior doctors caught in the clash: the transition from learning to working explored. Med Educ. 2011;45(10):968–970. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04052.x.

- Vivekananda-Schmidt P, Crossley J. Student assistantships: bridging the gap between student and doctor. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:447–457. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S62822.

- O’Brien BC. What to do about the transition to residency? Exploring problems and solutions from three perspectives. Acad Med. 2018;93(5):681–684. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002150.

- Ten Cate O. Medical education in the Netherlands. Med Teach. 2007;29(8):752–757. doi:10.1080/01421590701724741.

- Ten Cate O, Borleffs J, Van Dijk M, Westerveld T. On behalf of numerous faculty members and students involved in the subsequent Utrecht curricular reforms: training medical students for the twenty-first century: rationale and development of the Utrecht curriculum “CRU+. Med Teach. 2018;40(5):461–466. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1435855.

- Wijnen-Meijer M, Ten Cate O, Van Der Schaaf M, et al. Vertical integration in medical school: effect on the transition to postgraduate training. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):272–279. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03571.x.

- Wijnen-Meijer M, Ten Cate O, Van der Schaaf M, et al. Graduates from vertically integrated curricula. Clin Teach. 2013;10(3):155–159. doi:10.1111/tct.12022.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, et al. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718–725. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700.

- Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185–1190. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Expectations and obligations: professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):579–598. doi:10.1353/pbm.0.0045

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, et al. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446–1451. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427.

- Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 2010;44(1):40–49. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x.

- Monrouxe LV. Rees CE Theoretical perspectives on identity: researching identities in healthcare education. In: Cleland J, Durning SJ, eds. Researching Medical Education. 1st ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2015:129–140.

- Burford B. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):143–152. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04099.x.

- Ellemers N, Haslam SA. Social identity theory. In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, eds. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications; 2011:379–398.

- Turner JC. Reynolds KJ. Self-categorization theory. In: Van Lange PA, Kruglanski AW, Higgins TE, eds. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2012:399–417.

- Tajfel H. Introduction. In: Tajfel H, ed. Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. 2010th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1982:2.

- Milanov M, Rubin M, Paolini S. Different types of ingroup identification: a comprehensive review, an integrative model, and implications for future research. Psycol Soc. 2014;3:205–232. doi:10.1482/78347

- Cameron JE. A three-factor model of social identity. Self Identity. 2004;3(3):239–262. doi:10.1080/13576500444000047.

- Obst PL, White KM. Three-dimensional strength of identification across group memberships: a confirmatory factor analysis. Self Identity. 2005;4(1):69–80. doi:10.1080/13576500444000182.

- Haslam SA, Powell C, Turner JC. Social identity, self-categorization, and work motivation: rethinking the contribution of the group to positive and sustainable organisational outcomes. Appl Psychol. 2000;49(3):319–339. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00018.

- Obst PL, White KM. An exploration of the interplay between psychological sense of community, social identification and salience. J Commun Appl Soc Psychol. 2005;15(2):127–135. doi:10.1002/casp.813

- Kachanoff FJ, Ysseldyk R, Taylor DM, et al. The good, the bad and the central of group identification: evidence of a U-shaped quadratic relation between in-group affect and identity centrality. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2016;46(5):563–580. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2199.

- McMillan W. Theory in healthcare education research: the importance of worldview. In: Cleland J, Durning SJ, eds. Researching Medical Education. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2015:15–23.

- Hirsh DA, Ogur B, Thibault GE, et al. “Continuity” as an organizing principle for clinical education reform. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):858–866. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb061660.

- Van den Broek WES, Wijnen-Meijer MT, Cate O, et al. Medical students' preparation for the transition to postgraduate training through final year elective rotations. GMS J Med Educ. 2017;34(5):Doc65. doi:10.3205/zma001142.

- Querido S, Van den Broek S, De Rond M, et al. Factors affecting senior medical students’ career choice. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:332–339. doi:10.5116/ijme.5c14.de75.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Dedoose Version7.6.6, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. https://app.dedoose.com/App/?Version=7.6.6. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- Fredholm A, Manninen K, Hjelmqvist H, et al. Authenticity made visible in medical students ‘experiences of feeling like a doctor. Int J Med Educ. 2019;10:113–121. doi:10.5116/ijme.5cf7.d60c.

- Jarvis-Selinger S, MacNeil KA, Costello GRL, et al. Understanding professional identity formation in early clerkship: a novel framework. Acad Med. 2019;94(10):1574–1580. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002835.

- Ten Cate O, Snell L, Mann K, et al. Orienting teaching toward the learning process. Acad Med. 2004;79(3):219–228. doi:10.1097/00001888-200403000-00005.

- Vermunt JD, Verloop N. Congruence and friction between learning and teaching. Learn Instr. 1999;9(3):257–280. doi:10.1016/S0959-4752(98)00028-0.

- Flick RJ, Felder-Heim C, Gong J, et al. Alliance, trust, and loss: experiences of patients cared for by students in a longitudinal integrated clerkship. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1806–1813. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002812.

- Chen HC, Ten Cate O, O’Sullivan P, et al. Students’ goal orientations, perceptions of early clinical experiences and learning outcomes. Med Educ. 2016;50(2):203–213. doi:10.1111/medu.12885.

- Chen HC, Sheu L, O'Sullivan P, et al. Legitimate workplace roles and activities for early learners. Med Educ. 2014;48(2):136–145. doi:10.1111/medu.12316.

- Hirsh DA, Holmboe ES, ten Cate O. Time to trust: longitudinal integrated clerkships and entrustable professional activities. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):201–204. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000111.

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641–649. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260

Appendix A: Interview guide

Interview guide used for data collection project to explore significant workplace experiences during the transitional year and how these influenced professional identity development of the medical trainees:

How would you describe a doctor?

To what extent do you already see yourself as a doctor? Why?

Can you express that as a percentage of this scale? [introducing 100 mm visual analog scale from not-at-all to fully*] You do not have to concern about having sufficient skills or knowledge to be a doctor, this question is about identifying with doctors.

Can you further explain why you chose this point on the scale?

[Questions 2–4 are repeated for the preferred specialty of the interviewee for a residency]

Can you mention specific experiences during the transitional year that had an influence on your feeling of being a doctor? [Discuss the different locations where interviewee did a transitional year rotations. Further questions: Can you give an example of something that had a positive influence, and/or something that had a negative influence?]

Do you have the feeling you fit in the group of doctor? Would they welcome you? Why do you feel that way?

*To stimulate the interviewees’ thinking when answering these questions, we asked them to estimate their identification of being a doctor in general and of being their preferred specialist on a 100 mm visual analog scale (from not-at-all to fully). This was not indented to be used for quantitative measurements, but as an introductory question to have them elaborate on the reasons they indicated this particular point on the scale.

Interview guide used for data collection project to study factors influencing career considerations:

What are you career preferences? Can you explain for each of these why and since when?

How familiar are you with these preferences? And what have you done to become familiar with them?

Can you reflect on your transitional year in relation to your career preferences? How did your electives influence your preferences?

What is the opinion of your family, friends or others about your career preference? And what does that opinion mean to you?

Tell me your strategy to get into the residency of your choice?

Did any changes occur in your life of influence on your career preference over the last year?

What would be your definite choice just for the upcoming 5 min?

Follow-up questions were used to probe explanations of the answers more deeply.