Abstract

PhenomenonStudents, alongside teachers, play a key role in feedback. Student behavior in feedback processes may impact feedback outcomes. Student feedback behavior includes recognizing, seeking, evaluating, and utilizing feedback. Student feedback behavior is influenced by numerous student attributes and environmental factors. ApproachWe aimed to explore influences on medical student feedback behavior during clinical attachments. We adopted a subjective inductive qualitative approach. We conducted 7 focus groups with 46 medical students undertaking pediatric hospital-based attachments. We based our discussion framework on existing characterizations of student feedback behavior and the educational alliance model with its focus on the relationship between learners and teachers, and the active role played by both. During initial data analysis, we identified that our results exhibited aspects of Bandura’s model of Triadic Reciprocal Causation within Social Cognitive Theory. In line with our subjective inductive approach, we adopted Triadic Reciprocal Causation at this point for further analysis and interpretation. This allowed us to conceptualize the emerging interactions between influences on feedback behavior. Findings We identified three key determinants of student feedback behavior: Environmental influences, Student attributes and Relationships between teachers and students. Environmental influences encompassed factors external to the student, including Teacher attributes and behaviors and The clinical learning context. Through the lens of Triadic Reciprocal Causation, the interrelationships between the determinants of feedback behavior gave rise to five key themes: Interactions between student feedback behavior and environmental influences of the clinical learning context, Interactions between student feedback behavior and environmental influences of teacher attributes and behaviors, Interactions between student attributes and student feedback behavior, Interactions between student attributes and environmental influences of teacher attributes and behaviors, and Relationships and the determinants of student feedback behavior. Insights: We apply the Triadic Reciprocal Causation model of Social Cognitive Theory to understand the influences on student feedback behavior and the interactions between them. We extend the model by situating relationships between students and teachers as a central factor. Future interventions to facilitate students’ role in feedback will need to address student attributes, environmental factors, and student-teacher relationships, appreciating the codependent nature of these influences.

Introduction

Medical learners are frequently dissatisfied with feedback on their performance.Citation1,Citation2 This is concerning, given the centrality of feedback to learning.Citation3 The clinical learning context raises particular challenges for feedback, including limited duration of time with frequently changing clinical teams and supervisors,Citation4–6 limited teacher availability due to workplace demands,Citation7–9 variable availability of appropriate case mixesCitation7 and variable learning cultures.Citation4,Citation10

Historically, strategies to improve feedback for medical students have focused on increasing the quality of ‘feedback delivery’ by teachers.Citation11,Citation12 Unfortunately, dissatisfaction amongst medical learners has persisted despite these efforts.Citation1,Citation2 Attention has more recently turned to the potential of learner-centered feedback interventions that reflect modern conceptualizations of feedback as a relationship-based, two-way interaction between teacher and learner. Rather than a one-way transfer of information from the teacher, these approaches recognize the students’ central role in the process.Citation5,Citation13–15 Boud and Molloy call for learners to be repositioned as seekers and users of feedback rather than passive recipients,Citation2 describing feedback as “a process used by learners to facilitate their own learning.”Citation2 (p703-704) Telio et al.’s concept of the ‘educational alliance’Citation14 is important here. Drawing on the concept of the therapeutic alliance between patient and doctor, they emphasize the importance of feedback as a dialogical process occurring in the context of “an authentic and committed educational relationship,”Citation14(p612) where both student and teacher work together to agree on learning goals and identify specific strategies to progress toward these. As in a therapeutic alliance, achievement of goals is dependent on relationship quality.

The implication is that students play a key role in the feedback process and their behavior influences feedback outcomes. Drawing on the work of Molloy and Boud,Citation13 and Bowen et al.,Citation4 four aspects of student feedback behavior can be conceptualized: recognizing, seeking, evaluating, and utilizing feedback. Strategies to improve feedback need to focus on facilitating these aspects of agentic student feedback behavior.Citation5,Citation16,Citation17 To this end, the determinants of student feedback behavior need further investigation.

Related to agentic student feedback behavior is the notion of student feedback literacy. This is defined by Carless and BoudCitation18 as “the understandings, capacities and dispositions needed to make sense of information and use it to enhance work or learning strategies.”Citation18 (p1316) A learnable skill set, feedback literacy includes four key elements: appreciating the feedback process (including the learner’s active role); making performance judgements; managing emotional affect in response to feedback; and taking action on feedback to enhance learning.

Studies exploring the influences on student feedback behavior identify various determinants. These include learner attributesCitation4 (including student emotions),Citation1 teacher attributes and leadership stylesCitation4 (or student credibility judgements about teachers),Citation19 learning cultures,Citation1,Citation4 and relationships between teachers and learners.Citation1,Citation4 Feedback seeking is also influenced by the balance of perceived costs and benefits to ego (self-perception), image (as perceived by others), and learning.Citation20 The cost-benefit analysis depends on students’ goal orientation (learning vs. performance orientation).Citation21 Further influences on student feedback behavior include the feedback mode and the purpose and quality of feedback.Citation1,Citation4

Delva et al.’s model of feedback seeking as a cost-versus-benefit perceptionCitation1 highlights the role of relationships, feedback quality, and student emotions in feedback behavior. Bowen et al.’s model of learner feedback behaviorCitation4 links similar influences (relationships, mode of feedback, learner beliefs, attitudes and perceptions, and teacher attributes), embedding them in the broader learning culture. Bowen et al.’s model is not specific to the clinical learning environment, which warrants particular attention, given its unique challenges to feedback. Ajjawi et al.Citation22 offer a novel, hypothetical model of a medical student’s feedback experience through the lens of interactions between different levels of a social ecosystem.

Further research to understand the interactions between influences on feedback behavior is necessary to appreciate which interventions may facilitate optimal student feedback behavior. It is also necessary to understand the effect that targeting certain influences on feedback will have on other interdependent influences.

Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) offers a causational model of behavior that may be useful. He conceives of behavior not as the convergence of unidirectional forces, but as part of a triadic reciprocal interplay between personal factors, environmental influences, and behavior, known as ‘Triadic Reciprocal Causation (TRC).Citation23,Citation24 Personal factors (e.g., student attributes), environmental influences (e.g., the learning context) and (student) behavior “all operate as interacting determinants that influence each other bidirectionally.”Citation24(p2) This model contrasts with what Bandura describes as the “one-sided determinism”(p2) characteristic of historical views of human behavior. Notwithstanding the models already described,Citation1,Citation4 which go some way toward articulating links between influences on feedback behavior, existing literature on feedback behavior often tends toward this one-sided determinism perspective.Citation19–21 Further investigation of the determinants of student feedback behavior, viewed through the lens of the bidirectional interplay between factors, would add to the research literature on feedback. In this study we aimed to explore influences on medical student feedback behavior during clinical attachments. Our research questions were: 1) How do student attributes and the clinical learning context influence student feedback behavior and what are the interactions between these? 2) How does the student-teacher relationship (and roles within this) interplay with student feedback behavior?

Methodology

This study was undertaken through a qualitative approach involving focus group discussions,Citation25 analyzed through theoretical thematic analysis,Citation26 based on Social Cognitive Theory.Citation23,Citation24

Context

The research was undertaken in the Child and Adolescent Health specialty block of the 4-year graduate-entry University of Sydney Medical Program. Students undertaking the block are in the final 18 months of their degree. Students complete three fortnightly pediatric clinical attachments over the block, ranging from tertiary subspecialty pediatrics to emergency and general pediatrics. The block is based at a tertiary teaching hospital, however, some attachments occur at metropolitan or rural pediatric services. Students have one allocated supervisor for each two-week attachment. The supervisor is required to endorse adequate attendance and performance over the two-week period as a pre-requisite for passing the block. Supervisors are asked to provide formal written feedback at the end of the two-week attachment, however, this does not contribute to the student’s grade. Grading is based on performance in a written examination and practical OSCE (Observed Structured Clinical Examination) at the end of the block. Other formal feedback practices include formal individual feedback on a structured written history task, and an email to the whole student cohort about overall exam performance with clarification of areas of confusion. Some clinical attachment supervisors hold formal appointments with the university, others have affiliate status, while others may not have any formal university links. At the time of the study, junior medical staff were invited to attend a half-day clinical teacher training workshop, which included training on feedback delivery. Students attend an orientation day at the start of the pediatric block, which for the latter two cohorts in this study included a new one-hour workshop on feedback practices that aimed to help students develop feedback literacy.

Study design

We adopted a subjectivist inductive approach for this qualitative study, as described by Varpio et al.Citation27 This approach “searches for patterns across the data to generate an understanding of the phenomenon,” “going from specific data…to [an] abstract conceptualization of the phenomenon”.Citation27(p.992) It utilizes a constructionism paradigm, viewing theory as constantly evolving rather than a stable external truth. An expected outcome of research is the “[d]evelopment and refinement of theory.”

Within the subjectivist inductive approach, we utilized a theory-informing study design (one of the three designs within this approach, as described by Varpio et al.).Citation27 Consistent with this, we held various theories in mind during the initial design phase which informed our research questions and focus group discussion guide. In particular, we were inspired by Telio et al.’s educational alliance model,Citation14 with its emphasis on learning relationships and an active role in feedback for both students and teachers. We were also influenced by Molloy and Boud,Citation13 and Bowen et al.’s’Citation4 descriptions of student feedback behavior.

Insights that emerged during initial data analysis led us to identify that our results were exhibiting concepts that could be explained through Bandura’s TRC model. We identified that further investigation of feedback behavior would be most helpfully understood by adopting this as our theoretical framework. This practice of selecting a theory at the initial data analysis phase is valued by Varpio et al.Citation27 because of the “deep exploration of data” it facilitates.Citation27 (p992) Consistent with the theory-informing design, we modified our research questions to reflect the TRC model.

Sampling and recruitment

All students undertaking the Child and Adolescent Health specialty block across three consecutive cohorts between July 2017 and March 2018 were invited to participate. Emails explaining the study along with participant information sheets were sent to all students by an administrative officer not involved in teaching or assessment. Participation was entirely voluntary and no material incentives were provided other than a small snack during the focus groups. Written informed consent was given by all participants.

Data collection

Focus groups were undertaken in the education center of the block’s central teaching hospital. We used a pre-developed discussion framework based on Telio et al.’s therapeutic alliance model, and on Molloy and Boud,Citation13 and Bowen et al.’sCitation4 descriptions of student feedback behavior (Appendix 1). The focus was on feedback during the Child and Adolescent Health specialty block that the students were undertaking at a range of pediatric services, however, students occasionally commented on feedback during prior blocks. HM was the primary moderator for focus group discussions. KS took field notes and assisted with moderation as needed. No other clinical, teaching, or administrative staff were present. We continued focus groups until theoretical saturation was reached, decided by consensus between HM and KS when no new themes appeared. In total 7 focus groups were held, ranging from 29 to 59 minutes, with an average of 47 minutes.

The first three focus groups were conducted with the student cohort commencing in July 2017. Of the 66 students in the cohort, six students participated in focus group A, six in focus group B and five in focus group C. There were 58 students in the cohort commencing October, 2017 with five of these students participating in focus group D and five in focus group E. Due to the course structure there is an annual break until March 2018. Of the 68 students in the March 2018 cohort, nine participated in focus group F and 10 in focus group G. There was broad representation of ages and genders across the focus groups.

While focus groups with the first cohort were held during the block (after two clinical attachments and lecture week), subsequent focus groups were held at the end of the block (after the third attachment and exams) to ensure we captured students’ feedback experience of the entire block.

Field notes were taken of key participant non-verbal responses and to facilitate reporting. Focus groups were audio-recorded using the iPhone TM voice memo function and subsequently converted to audio files and transcribed by administrative staff and HM into Microsoft WordTM documents. In reporting quotations, focus groups are coded with a letter (A to G) and participants are deidentified (transcribed as only Male/Female and a number).

Data analysis

NVIVO softwareTM (QSR InternationalTM, version 12 plus for Microsoft WindowsTM) was used for data management and analysis. Using line-by-line coding, HM and KS separately undertook initial thematic analysis guided by our original conceptual framework, particularly the dual roles of students and teachers within the educational alliance. Subsequent discussion between HM and KS about the emerging themes resulted in the identification of SCT, in particular the TRC triad, as the most appropriate theoretical framework. Data was then analyzed through theoretical thematic analysis,Citation26 with content allocated under three concepts: behavior, personal attributes and environment. Although initially incorporated within these three elements, further discussion between HM and KS led to the identification of ‘relationships’ as a separate concept that interacted with each component of the TRC triad. Codes within these concepts and the interactions between them were further analyzed and compared to key points identified in the field notes. The concepts and broader categories became the themes and sub-themes of the data and were incorporated into a coding structure. Subsequent transcripts were coded by HM according to the initial coding structure, supervised by KS. Consensus on final coding was reached following multiple rounds of review, comparison, and discussion. The analysis is outlined in the Results and includes participant quotations that illustrate key points.

Reflexivity

The study was motivated by University-run student evaluation surveys about the student learning experience that indicated a relative weakness in student satisfaction with feedback compared to other aspects of learning and teaching. The low satisfaction with feedback was present in both the pediatric block and the Faculty of Medicine and Health as a whole. We were inspired by the potential of improving feedback via student-centered approaches, highlighted in recent feedback literature. All authors held assumptions about the importance of feedback to enhance learning in the clinical context. The authors believed that both students and teachers had roles and responsibilities in facilitating the feedback experience.

All authors held academic positions with the Child and Adolescent Health specialty block of the University of Sydney Medical Program (HM as associate lecturer, PC and HG as academics and pediatricians, and KS as education academic). At the time of the study, HM was undertaking an Academic Fellowship as part of the final stages of a pediatric training program, HG was block coordinator, HM, PC, and HG were actively engaged in teaching on the specialty program, while KS was actively involved in e-learning and teacher development. Given study participants were all students of the program where the authors held academic positions, there was a power differential between investigators and students. We attempted to minimize this by holding focus groups after completion of assessments where possible, and assuring confidentiality of views expressed by participants (other than deidentified data).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (2017/531).

Results

Forty-six students participated in the focus groups. The majority of comments were focused on verbal feedback exchanges during clinical attachments, with a small number of comments about formal written feedback. Initial data analysis led to the identification of three key determinants of student feedback behavior: Environmental influences, Student attributes, and Relationships between teachers and students. Environmental influences encompassed factors external to the student, including Teacher attributes and behaviors and The clinical learning context. We identified emerging interrelationships between these factors and subsequently adopted Bandura’s TRC as our theoretical framework (as described in Methods). The educational alliance (or relationships) continued to be highlighted as a key factor in our data analysis. However, we reframed our exploration of relationships as a concept that may interplay with all determinants of feedback behavior, rather than simply having a unidirectional influence on feedback.

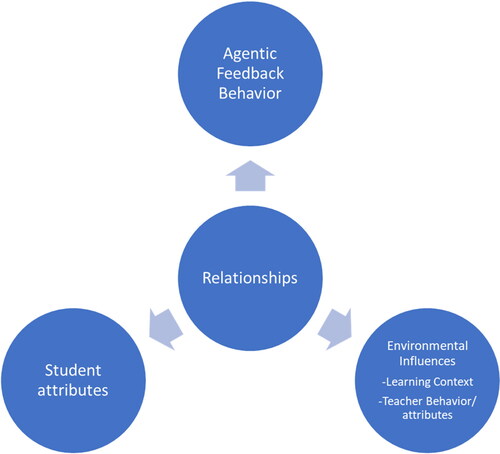

Final data analysis resulted in five key themes: Interactions between student feedback behavior and environmental influences of the clinical learning context, Interactions between student feedback behavior and environmental influences of teacher attributes and behaviors, Interactions between student attributes and student feedback behavior, Interactions between student attributes and environmental influences of teacher attributes and behaviors, and Relationships and the determinants of student feedback behavior. From these themes we developed the following model, adapted from Bandura’s description of Triadic Reciprocal Causation ().

Figure 1. The interrelationship between influences on feedback behavior. Adapted from Bandura (1989).

Interactions between student feedback behavior and environmental influences of the clinical learning context

Features of the clinical learning context could act as either barriers or facilitators to students seeking feedback.

Time pressures

The time pressure on doctors was recurrent concerns for students, often preventing them from seeking feedback. One student felt as though ‘you’re taking away from a patient’s care if you want to ask for feedback’ and was reluctant to be ‘interrupting a doctor’s work day’ (D1). Students decided whether or not to seek feedback depending on whether they believed clinical staff had enough time to do it.

Student numbers

Students found it particularly hard to access doctors for feedback when there were large numbers of students in a team. In response, some sought rotations where student numbers were lower: ‘Now I purposely try and get placements where I’m by myself’ (A6).

Learning culture

Participants felt they received more feedback in teams where teaching was encouraged by all team members and a safe, non-judgmental approach to learning was established. They highlighted variations in learning and feedback cultures amongst teams: ‘It should be part of the culture… in some groups it really is and in others not so much’ (B6).

Hierarchy

Students noticed the hierarchical structure of the medical system and sensed a power imbalance between themselves and doctors. In some cases, this prevented them from requesting feedback: ‘It’s daunting to approach anyone who’s more senior than you…that’s just life…there’s a hierarchy and that’s the way that it is’ (A3).

Clinical involvement

Participation in clinical activities, particularly assessing and presenting patients, was felt to be an important basis for feedback: ‘For the feedback to be useful, you’ve got to…have an active position in the team’ (F6). Where clinical involvement was lacking, students questioned: ‘What’s the point of asking feedback from someone who’s basically just seen me stand there?’ (F2).

Assessment structure

Students noted misalignments between learning requirements for assessments and requirements for performance as doctors. Some acknowledged an assessment focus (particularly around exam time) that led them to seek feedback less, in favor of focusing time on assessment-relevant tasks: ‘When it’s closer to exams you feel less motivated’ (G9). In the specific context of formal written feedback at the end of an attachment, one student reported not reading it as they were focused on exam study: ‘The doctor actually wrote something down – I haven’t read it because I just went on with studying’ (G2).

Interactions between student feedback behavior and environmental influences of teacher attributes and behaviors

Students modified their feedback behavior based on judgements about teacher attributes and behaviors. Some students also perceived that their own feedback seeking behavior altered their teacher’s behavior.

Perceived interest of teachers

Students had perceptions about the level of interest teachers had in them and this impacted whether they sought and took on board feedback. Level of interest was perceived to be demonstrated when teachers engaged with students, discussed learning goals and expectations, discussed patient cases and suggested learning strategies.

One student mentioned not asking for feedback in situations where they did not feel their existence was recognized by the medical team (A5). Students valued feedback less in these situations: ‘You’re not really interested in the feedback they’d have because it wouldn’t be accurate’ (D3). In contrast, another student suggested that ‘if you’re made to feel welcome…it’s so easy to be asking for opportunities because you feel like that person values you and values you wanting to learn’ (B2).

Approachability

A number of students mentioned the importance of teacher approachability. One student felt it was the central factor determining how active they would be in seeking feedback: ‘How approachable the clinician is almost determines how proactive you will be’ (G5).

Feedback delivery style

Whether feedback was taken on board was influenced by teachers’ feedback delivery style. Harsh styles could result in students rejecting feedback: ‘If they’re always angry and telling everyone off, I probably wouldn’t listen to that feedback’ (D2).

Student preferences for balancing positive and constructive comments varied. Some students valued constructive feedback: ‘I like feedback that is pertinent to the point of progress, I like it to be unemotional, I like them to say - this is what you did, this is what was expected, here’s the gap’ (B4). Others preferred positive praise: ‘I think it’s very personal…there are…many people who like praise and I’m one of them’ (B6). Students were aware of variations in preferences and suggested that teachers needed to judge the balance of constructive vs positive praise required for individual students.

Agentic student feedback behavior perceived to motivate teacher behavior

Just as student behavior was influenced by teacher attributes and behaviors, it also had an influence on teacher attributes (as perceived by students). One student described a series of positive feedback episodes with the same teacher. The student’s perspective was that in addition to assisting the student to learn, the process motivated the teacher: ‘I was able to take that feedback and then use it for the next [case]… He was also I think happy by the end of it because… [my improvement] was sort of like giving feedback… it was a 2 way street’ (G9).

Interactions between student attributes and student feedback behavior

Students varied in self-efficacy beliefs and perceptions of their role in feedback, with subsequent effects on their feedback behaviors.

Student motivation

Students were motivated to seek feedback by a desire to assess their learning and improve: ‘I just want to get better…the quicker the better’ (B4).

Student self-efficacy beliefs

Some students demonstrated high self-efficacy beliefs regarding their capacity to actively engage in feedback and reported various strategies to increase feedback opportunities. For example, arranging meetings with a key supervisor at the start of rotations to plan learning, planning times for feedback encounters ahead of time, intentionally investing in relationships with the medical team, demonstrating interest and repaying clinicians for their time by completing administrative or logistical tasks, seeking out case presentations as a high yield feedback activity, and persistence in requesting feedback even if initially deferred due to patient demands.

Self-efficacy beliefs did, however, vary between students. Some felt daunted by the prospect of seeking feedback: ‘I wanted to do it but for some reason I was afraid…I don’t think any one of us wants to ask for feedback – it’s embarrassing and awkward’ (D2). Others felt confident to seek feedback: ‘That opportunity to seek and receive feedback is always open for me’ (E3), but acknowledged this varied between students. Some believed ‘a proactive approach is definitely better’ (C4) and students should ‘be bold and ask for feedback’ (E1).

Self-efficacy was influenced by personal and vicarious experiences of feedback behavior. For example, repeated experiences of being brushed off when asking for feedback could lead to giving up: ‘If it works it’s nice but some of the time it doesn’t work and everybody’s kind of brushing you off to the next person and the next person, and eventually you get fed up’ (B4). After witnessing harsh, critical feedback given to a colleague, one student remarked: ‘I probably would have cried and you never would want to talk to that doctor, seek any feedback ever again’ (D5).

Emotional resilience influenced self-efficacy and could vary over a day or a term: One student admitted their decision to ask for feedback could be emotion-based: ‘Some days I’m like, “You know what? I’m in a good mood” and other days I’m tired, there are other things going on in my life’ (A5). The students reported protecting their emotions by ‘recognizing when [it] is a day where you might be more vulnerable’ (A5) or have limited performance capacity: ‘If today’s not a day that I’m gonna perform at my best then I’d be far less inclined to seek feedback’ (A5).

Student perceptions about their role in feedback

Perceptions about the primary responsibility for initiating feedback varied. Many students had a preference for teachers initiating feedback: ‘It’s much easier if somebody else creates that engagement, otherwise you just feel like you’re imposing or you’re wasting somebody’s time’ (A1). In contrast, one student felt that ‘the responsibility is upon us to seek feedback - not so much the…medical staff that aren’t being paid to teach us’ (E2). Many recognized the dual responsibility: ‘It was probably a combination - me not seeking out the opportunities but them also…not making them available to me’ (B5).

Student perceptions of relevance

Students were more likely to ask for feedback if they perceived ‘the topic’s of any use’ (A2) or ‘if I can identify a skill that I think is going to be important’ (A1). Perceived relevance impacted on utilization of feedback. Where students were advised to further their knowledge of a topic whose relevance they questioned, they reported ‘there’s no chance I’m [going to] look that up because – is it important?’ (D1).

Interactions between student attributes and environmental influences of teacher attributes and behaviors

Teacher factors impacted on student attributes which, as we have shown, have flow-on effects to student feedback behavior.

Impact of feedback delivery style on student attributes

Students reported that their emotional resilience and confidence were impacted by teachers’ feedback delivery style. For example, one student remarked that ‘For someone to just lash out and tell us that we’re bad at something in a certain way makes us feel worse and then we become more insecure - it’s just a vicious cycle.’ (D1).

Impact of teacher inclusivity on student attributes

Participants described how they felt more confident to ask for feedback when they perceived teachers to be inclusive of them: ‘You’d have to hail their [doctors’] attention because they’re super busy but you felt comfortable to do that’ (A6).

Relationships and the determinants of student feedback behavior

Relationships between students and teachers played a central role in student feedback behavior. As one participant stated, ‘I think your relationship with the person you’re asking feedback from is very important’ (E2). Relationships impacted on student attributes and feedback behavior, which in turn influenced relationships. Furthermore, contextual factors exerted their effect on feedback behavior via their influence on relationships.

Impact of relationships on student attributes

Students were more confident to ask for feedback in the setting of positive educational relationships. They also reported improved self-concept when they felt clinically involved and part of the medical team: ‘As soon as you feel useful, that whole thing about feeling like a nuisance goes away…because you’re like - I’m actually contributing’ (B1).

Impact of relationships on feedback behavior

We have described above how the perceived interest of teachers in students influenced whether they sought feedback. This perception of teacher interest can also be seen as students’ perception of the quality of relationships and illustrates the impact of teachers on relationships.

In addition to improving feedback seeking behavior, positive relationships also improved the likelihood of students using feedback. One student said: ‘I knew that they knew me and I knew them, so I knew that whatever feedback they gave me…I was like, ‘Oh I can work on that’’ (A6). Students valued feedback more from clinicians with whom they had positive relationships. Another student said: ‘When you establish a relationship… your supervisors know you and give you clinically useful feedback that’s like, concrete feedback’ (E1).

Impact of student behavior on relationships

Students reported certain behaviors that built their relationships and sense of belonging with the medical team, for example reviewing patients on behalf of doctors in the team. Some students even engaged in feedback with the specific intention of developing professional relationships.

Impact of teachers on relationships

Students highlighted that teachers could facilitate their sense of belonging. For example, students said that when teachers introduced them as ‘doctors in training’, it resulted in them feeling ‘a lot more…useful and part of the team’ (B1).

Impact of learning context factors on relationships

Some of the learning context factors described previously in terms of their influence on student feedback behavior can be viewed via their mediating impact on relationships. For example, students described the impact of a strong assessment focus on relationships: ‘Because there’s also exams coming up and we’ve got a lot of lectures to watch and things, I didn’t establish that bond very well…that really cost me in terms of relationships’ (C1). Similarly, attachment duration impacted relationships and therefore feedback. One student felt ‘the two week attachment does make it very transient’ and described how the short duration facilitated a lack of investment by supervisors in students (B2). On the other hand, another participant believed: ‘If you spent a whole week with somebody…I would be much more…likely to ask for feedback and respect the feedback that I’m getting’ (E2).

Lack of continuity made feedback challenging because ‘it was hard to follow up with the same person on different weeks’ (C3).

Challenges to quality relationships

Unfortunately, developing quality relationships could be extremely challenging for students. One student reported a colleague telling them their rotation ‘“was like being Bruce Willis in the Sixth Sense”… sometimes you do feel like that as a med student, you’re just like, “Can anyone see me?”’ (F6). However, a number of students recognized the dual student/teacher responsibility in establishing educational relationships: ‘It works two ways…you have to allow the clinician to let you be a part of it but you have to want to be part of the team’ (F2). Another said: ‘Every human interaction requires a bit of give and take’ (A1).

Discussion

We identified three key interrelating influences on student feedback behavior: Environmental influences (including Teaching attributes and behaviors and The clinical learning context), Student attributes; and Relationships between teachers and students. The interactions between these factors gave rise to five key themes to conceptualize the determinants of feedback behavior: Interactions between the environment and student feedback behavior, Interactions between student attributes and the environment, Interactions between student attributes and student feedback behavior, and Interactions between relationships and student feedback behavior.

From these themes we developed a model of the influences on student feedback behavior, adapted from Bandura’s description of Triadic Reciprocal Causation. This model explicitly demonstrates the two-way interactions between the determinants of feedback behavior, embedded in the environmental context, and centered around educational relationships.

The determinants of feedback highlighted in our study and resulting model reinforce similar themes identified by other authors, including Bowen et al.,Citation4 Delva et al.,Citation1 Ramani et al.,Citation28 and Ajjawi et al.Citation22 Bowen et al. and Delva et al.’s models arise from their studies with medical students and medical residents respectively. Ramani et al.Citation28 offer a narrative ‘twelve tips’ article focusing on feedback culture in medical education while Ajjawi et al.Citation22 examine the feedback experience of a hypothetical medical student through an ecological perspective. They look at social interactions between learners, teachers, and contexts, operating at different system levels (microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem) in different settings.

Similar to our understanding of feedback behavior being embedded in the environmental context, other studies have also noted the significance of teacher attributes and the learning context on feedback. Consistent with our finding that feedback delivery style influenced student feedback behavior, Tuenissen et al.Citation21 found that medical residents whose teachers had an ‘instrumental’ style (setting clear goals and expectations for learning activities) were more likely to seek feedback. We also noted that demonstrated interest in students and approachability were key teacher attributes that encouraged agentic student behaviors. In a similar vein, Bok et al.Citation20 showed that veterinary students were more likely to seek feedback from teachers who were perceived as accessible, good communicators, and willing to provide feedback. Telio et al.Citation19 found psychiatry residents were more likely to accept feedback from teachers they perceived to be interested in them as students. Bowen et al.Citation4 showed how teacher attributes (including perceived teacher engagement, effort, approachability) impacted on medical student feedback seeking, recognizing, and utilizing feedback.

In regard to the learning context, in our study the duration of time students spent with specific doctors and clinical teams was particularly influential in terms of feedback. This was also noted by Noble et al.Citation5 amongst nursing, medical, and social work students, and by Bowen et al.Citation4 in medical students. Other influential factors were the learning and teaching culture (also highlighted by Bowen et al. and Delva et al.Citation1), the opportunity for clinical involvement, time pressure on doctors, degree of hierarchy, and high student numbers (resulting in competition for access to patients and teachers).Citation28 We found university assessment practices that were insufficiently aligned with learning outcomes adversely impacted where students focused their learning and feedback behavior. This is consistent with a report by Delva et al.,Citation1 that poorly aligned formal and informal assessments were a barrier for medical residents seeking feedback. Ajjawi et al.Citation22 also proposed that university and hospital factors influence feedback.

As well as being grounded in the environmental context, we found feedback behaviors were significantly connected to the relationships between students and clinical teachers. This is in line with other studies reporting that the quality of the student-teacher relationship influences whether students seek feedbackCitation1,Citation4 and whether they utilize feedback for learning.Citation4,Citation29,Citation30 Going further, we found that relationships were interconnected with each determinant of feedback behavior. The centrality of relationships has been highlighted by other authors, including Ramani et al.,Citation31 and Telio et al.,Citation14 whose educational alliance model was a key component of our initial conceptual framework. The interconnectedness and bidirectional influence of the determinants of feedback is a key finding of our study, aided by Bandura’s theory of Triadic Reciprocal Causation.Citation24 Bandura describes how personal (student) factors, such as beliefs, self-perception, and emotions, influence behavior, the effects of which impact cognitive patterns and affect. Personal factors also impact on one’s environment, for example a student’s perceived engagement may influence teacher feedback behavior, which in turn alters student factors such as self-perception. Furthermore, student behavior interacts with the environment and aspects of the environment can be potentiated by specific behaviors. For example, student feedback-seeking behavior may cause teachers to provide more learning and feedback experiences, further encouraging agentic student feedback behavior. In this way, an individual’s attributes, behavior, and environment are interdependent and constantly modulated by each other.

Bowen et al.’sCitation4 and Delva et al.’sCitation1 models of feedback behavior have also sought to demonstrate the linkages between influences on feedback behavior. Bowen et al., in particular shows how relationships are at an intersection between learning culture, teacher attributes, learner attributes, and learner behaviors. Our model develops this interconnectedness further, explicitly characterizing the backward and forward domino effect of one factor on another. Ajjawi et al.Citation22 explore the possibility of bidirectional influences in a hypothetical setting. Whether positive or negative, a change in any influence is likely to result in a reinforcing cycle. Furthermore, if multiple aspects of our triadic model are targeted for improvement, the potential for impact is multiplied.

Limitations

Our study focuses on a specific group of medical learners late in their postgraduate medical studies. It is possible that learner feedback behavior is different in other settings, such as medical specialist training, different cultural settings, non hospital-based settings, students earlier in training, and non-medical health students. While our model may be applicable outside this study context, further research is needed to explore the variations that may arise.

A further limitation is that this study only sought the perspectives of learners. A more complete understanding of learner behavior and its interaction with teachers and context may have been constructed by eliciting the perspective of teachers.

While we set out to explore all aspects of feedback behavior, much of the data volunteered during focus groups centered on feedback seeking. It may be that this is the more concrete component of feedback behavior and therefore easiest to elicit data on. Further research will need to consider appropriate questions to specifically explore evaluation and utilization of feedback.

Future research directions

Further research is needed to test the applicability of our model in healthcare learning contexts beyond the medical student population that was the focus of this study. We plan to explore this model in the specialist medical training context. In addition, this model will be used to inform multipronged interventions to improve feedback, targeting each of the key determinants of feedback behavior.

Conclusion

We developed a model, adapted from Bandura’s Triadic Reciprocal Causation, to conceptualize the complex interplay between determinants of medical student feedback behavior. In this model, educational relationships are a central and mediating influence on the other key factors of student attributes and environmental factors (involving the clinical learning context and teacher characteristics). Future study of interventions to improve feedback behavior must consider each of these factors and their interconnectedness.

Authorship

All authors were involved in study design, HM and KS conducted the focus groups (HM as primary moderator, KS supporting) and analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

HTLM-2021-0870.R1_SUPPLEMENTAL.CONTEN.POST.ONLINE.ONLY.pdf

Download PDF (114.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the medical students who participated in the focus groups for this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Delva D, Sargeant J, Miller S, et al. Encouraging residents to seek feedback. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):e1625–e1631. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.806791.

- Urquhart LM, Rees CE, Ker JS. Making sense of feedback experiences: a multi-school study of medical students’ narratives. Med Educ. 2014;48(2):189–203. doi:10.1111/medu.12304.

- Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2007;77(1):81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Bowen L, Marshall M, Murdoch-Eaton D. Medical student perceptions of feedback and feedback behaviors within the context of the “educational alliance. Acad Med. 2017;92(9):1303–1312.

- Noble C, Billett S, Armit L, et al. It’s yours to take”: generating learner feedback literacy in the workplace. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2020;25(1):55–74. doi:10.1007/s10459-019-09905-5.

- McGinness HT, Caldwell PHY, Gunasekera H, Scott KM. An educational intervention to increase student engagement in feedback. Med Teach. 2020;42(11):1289–1297. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1804055.

- Hoffman KG, Donaldson JF. Contextual tensions of the clinical environment and their influence on teaching and learning. Med Educ. 2004;38(4):448–454. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01799.x.

- Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IH, Heineman E, Scherpbier AJ. Factors adversely affecting student learning in the clinical learning environment: a student perspective. Education for Health (Abingdon, England) 2008;21(3):32.

- Yau BN, Chen AS, Ownby AR, Hsieh P, Ford CD. Soliciting feedback on the wards: a peer-to-peer workshop. Clin Teach. 2020;17(3):280–285. doi:10.1111/tct.13069.

- Urquhart LM, Ker JS, Rees CE. Exploring the influence of context on feedback at medical school: a video-ethnography study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(1):159–186. doi:10.1007/s10459-017-9781-2.

- Anderson PA. Giving feedback on clinical skills: are we starving our young? J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):154–158. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-000295.1.

- Branch WT, Paranjape A. Feedback and reflection: Teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77(12 Pt 1):1185–1188. doi:10.1097/00001888-200212000-00005.

- Molloy E, Boud D. Seeking a different angle on feedback in clinical education: The learner as seeker, judge and user of performance information. Med Educ. 2013;47(3):227–229. doi:10.1111/medu.12116.

- Telio S, Ajjawi R, Regehr G. The "educational alliance" as a framework for reconceptualizing feedback in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):609–614. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000560.

- Molloy E, Ajjawi R, Bearman M, Noble C, Rudland J, Ryan A. Challenging feedback myths: Values, learner involvement and promoting effects beyond the immediate task. Med Educ. 2020;54(1):33–39. doi:10.1111/medu.13802.

- Noble C, Sly C, Collier L, Armit L, Hilder J, Molloy E. Enhancing feedback literacy in the workplace: A learner-centred approach. In: Billett S, Newton J, Rogers GD, Noble C, eds. Augmenting health and social care students’ clinical learning experiences: Outcomes and processes. Switzerland: Springer; 2018.

- Winstone NE, Nash RA, Parker M, et al. Supporting Learners ‘ Agentic Engagement With Feedback: A Systematic Review and a Taxonomy of Recipience Processes Supporting Learners ‘ Agentic Engagement With Feedback: A Systematic Review and a Taxonomy of Recipience Processes, 2017; 1520. doi:10.1080/00461520.2016.1207538.

- Carless D, Boud D. The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess Eval Higher Educ. 2018;43(8):1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Telio S, Regehr G, Ajjawi R. Feedback and the educational alliance: examining credibility judgements and their consequences. Med Educ. 2016;50(9):933–942. doi:10.1111/medu.13063.

- Bok HGJ, Teunissen PW, Spruijt A, et al. Clarifying students’ feedback-seeking behaviour in clinical clerkships. Med Educ. 2013;47(3):282–291. doi:10.1111/medu.12054.

- Teunissen PW, Stapel DA, van der Vleuten C, Scherpbier A, Boor K, Scheele F. Who wants feedback? An investigation of the variables influencing residents’ feedback-seeking behaviour in relation to night shifts. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):910–917.

- Ajjawi R, Molloy E, Bearmann M, Ress C. Contextual influences on feedback practices: An ecological perspective. In: Carless S, Bridges S, Chan C, Glofcheski R, eds. Scaling up Assessment for Learning in Higher Education. Singapore: Springer; 2017:129–143.

- Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

- Bandura A. Social Cognitive Theory. Ann. Child Devel. 1989;6:1–60.

- Neuman WL. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 5th ed. Bost on, MA: Pearson Education Inc.; 2003.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med. 2020;95(7):989–994. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075.

- Ramani S, Konings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM. Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: Swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):625–631. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432850.

- Price M, Handley K, Millar J. Feedback: focusing attention on engagement. Stud Higher Educ. 2011;36(8):879–896. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.483513.

- Sutton P. Conceptualizing feedback literacy: knowing, being, and acting. Innov Educ Teaching Int. 2012;49(1):31–40. doi:10.1080/14703297.2012.647781.

- Ramani S, Konings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM. Relationships as the backbone of feedback: exploring preceptor and resident perceptions of their behaviors during feedback conversations. Acad Med. 2019;95(7):1073–1081.