Abstract

Phenomenon: Intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people report overwhelmingly negative experiences with health care providers, including having to educate their providers, delaying, foregoing, and discontinuing care due to discrimination and being denied care. Medical education is a critical site of intervention for improving the health and health care experiences of these patients. Medical research studies, clinical guidelines, textbooks, and medical education generally, assumes that patients will be white, endosex, and cisgender; gender and sex concepts are also frequently misused. Approach: We developed and piloted an audit framework and associated tools to assess the quantity and quality of medical education related to gender and sex concepts, as well as physician training and preparedness to meet the needs of intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit patients. We piloted our framework and tools at a single Canadian medical school, the University of British Columbia, focused on their undergraduate MD program. We were interested in assessing the extent to which endosexnormativity, cisnormativity, transnormativity, and the coloniality of gender were informing the curriculum. In this paper, we detail our audit development process, including the role of advisory committees, student focus groups, and expert consultation interviews. We also detail the 3-pronged audit method, and include full-length versions of the student survey, faculty survey, and purpose-built audit question list. Findings: We reflect on the strengths, limits, and challenges of our audit, to inform the uptake and adaptation of this approach by other institutions. We detail our strategy for managing the volume of curricular content, discuss the role of expertise, identify a section of the student survey that needs to be reworked, and look ahead to the vital task of curricular reform and recommendations implementation. Insights: Our findings suggest that curricular audits focused on these populations are lacking but imperative for improving the health of all patients. We detail how enhancing curriculum in these areas, including by adding content about intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people, and by using gender and sex concepts more accurately, precisely and inclusively, is in line with the CanMEDS competencies, the Medical Council of Canada’s Objectives for the Qualifying Examinations, many institutions’ stated values of equity, inclusion and diversity, and physicians’ ethical, legal and professional obligations.

Phenomenon

IntersexCitation1, transCitation2, and Two-SpiritCitation3 people experience systemic barriers to quality health care. Evidence from Canada and the United States suggests that many intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people delay, discontinue or avoid seeking care, due to pervasive stigma, discrimination and negative encounters with providers who lack knowledge and experience in gender- and sex-inclusive practice, and Indigenous cultural competence.Citation4,Citation5 Medical education curricular content on the health of intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people is often cursory, optional, and elective and largely focused on improving attitudes rather than building and practicing clinical skills. Providers may misgender patients or focus solely on their sexes, gender identities or sexualities while neglecting other health needs.Citation4 Further, intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people are frequently tasked with educating their providers and advocating for their own care needs.Citation6 These actions contribute to a system of inequitable care for these patients and negatively impact health outcomes. More broadly, the reification of gender essentialism, endosexnormativity, cisnormativity, transnormativity, and the coloniality of gender in medical curricula (see Supplementary Material A for our definitions of these terms) functions to sustain both passive and active erasure of intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people from discourses of health and wellness.Citation7 As the assumedly white, endosex, cisgender body remains the standard in research studies, clinical guidelines, and medical school textbooks, providers are left without appropriate knowledge, policies or practices to serve intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit patients.Citation7 This informational and institutional erasure harms intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit patients by rendering their health needs, their bodies and indeed their very identities invisible. Importantly, medical education is routinely mentioned as a critical site of intervention to improve care for intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people.Citation8–11 Despite growing recognition of gender as a key determinant of health and health advocacy as a vital physician competency, medical education pertaining to care of intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit patients remains limited. Intersex, trans and Two-Spirit people patients need access to competent providers in all aspects of health care.

Medical education literature suggests an overall dearth of curricula focused explicitly on gender diversity. Where this type of curricula does exist, it is routinely collapsed with sexual identity into the category “LGBTQ.” A 2011 review of US and Canadian medical school undergraduate curricula reported a median time of five hours dedicated to LGBTQ-related content.Citation6 While medical students believe education on gender and sexuality is important, many do not feel such content is adequately addressed in their training.Citation4,Citation9,Citation11 Only 16% of US medical schools accredited with the Liaison Committee on Medical Education included comprehensive training on LGBTQ health, and more than half reported none at all.Citation12 By utilizing the umbrella language of LGBTQ, the unique, nuanced needs of these different communities are overlooked. Focus is primarily on sexuality and sexual minorities (cisgender men and women who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, etc.), often to the exclusion of discussions about gender and gender minorities (trans men, trans women, and nonbinary people, who will have varied sexualities).

A 2018 review of trans health content in North American medical undergraduate and postgraduate education found training is composed primarily of one-time attitude and awareness-based interventions that “suffer methodologically from the lack of long-term assessment, the lack of emphasis on clinical skills, or the evaluation of patient outcomes.”Citation8 In Canada, a 2016 survey of both medical students and program administrators noted large differences in time spent on trans health, ranging from zero to two hours, to greater than eight hours.Citation4 Administrators at the University of British Columbia (UBC) reported two to four hours of curricular time dedicated to trans health in the first year, however 70% of UBC students surveyed did not feel the subject was adequately taught.Citation4 When surveyed, only 6% of UBC medical students and 7% of students at other Canadian medical schools felt knowledgeable to address the concerns of trans patients in primary care settings.Citation4 While the response rate for this survey was low, these data align with a 2009–2010 survey of over 4,000 North American medical students, of which over 67% rated their LGBTQ-related curricula as “fair” or worse.Citation11 Where trans-specific content is included in medical education curriculum, it typically focuses solely and exclusively on gender-affirming hormones and surgical interventions to the exclusion of other health care needs. This reduction is inadequate and indicative of a lack of understanding of the barriers trans patients face in primary, emergency, palliative, specialist, and other health care settings across the life course. Research suggests training in trans-specific content and clinical exposure to trans medicine improves student comfort, confidence, knowledge, and skill to provide care to trans patients.Citation10

Two-Spirit people are frequently added to the LGBTQ acronym, with the label “2S” as though their experiences are synonymous with those who identify using Western identity labels like lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer. Our review of the literature was unable to locate research that considered whether and how medical education curricula considers the specific needs of Two-Spirit people. Two-Spirit people’s health is impacted by cis- and heteronormativity but also by racism and colonialism. This means that Two-Spirit people’s specific health care needs and barriers to affirming care will not be attended to when lumped in with LGBTQ people, especially insofar as whiteness is constructed as central to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer identities.Citation13,Citation14

Intersex people are also sometimes added to the LGBTQ acronym, with the letter “I”. Our review of the literature was similarly unable to locate research that considered whether and how medical education curricula considers the specific needs of intersex people. Evidence suggests that medical students have significantly less knowledge of intersex health as compared to knowledge about lesbian, gay and bisexual people’s health.Citation15 The reduction of “intersex health” to merely a matter of at-birth sex determination for those with differences in sex development, along with associated medical interventions, is inadequate. This framing is indicative of a lack of understanding of the complexity of intersex people’s health care needs, including health care needs across the life course.

While education alone cannot address the structural inequities that shape health care, identifying and addressing gaps in medical education will help improve clinical encounters between intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit patients and providers. This article explores the process of developing an audit framework and purpose-built tools, formulated with two stated goals. First, we wanted to develop a method for assessing the extent to which students are being equipped with the language, skills, and confidence to provide quality and affirming care to intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit patients. Second, we wanted to develop a method for determining how medical education curriculum mobilizes the concepts of gender and sex. These concepts are frequently confused and conflated (e.g., where sex terms like male and female and gender terms like man and woman are used interchangeably) and used as crude proxies for anatomy or physiology (e.g., where female is used as a stand-in for people with vulvas, who menstruate, etc.).Citation16–18 For example, we note that among four curricular audit projects purportedly focused on sex- and gender-based medicine, each exclusively considered the extent to which cisgender women’s health was addressed in the curriculum.Citation19–22 Our contention is that when gender and sex are conceptualized and mobilized accurately, precisely, and inclusively in medical education, this will positively impact the health and healthcare experiences of all people. In writing this manuscript we share the details of our process, publish our tools, and reflect on the strengths and shortcomings of our approach. Our hope is that other universities and colleges who train healthcare providers will undertake their own curricular audit projects, to both standardize and improve the curriculum.

Approach

Study setting

The University of British Columbia is currently home to the only medical school in the province. The province of British Columbia was created on the lands of over two hundred Indigenous nations through a strongly resisted yet ongoing process of colonial land dispossession that has created serious health disparities for Indigenous people in the province. The University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine has distributed sites throughout the province. The undergraduate program (also known as the MD program) is a four-year training program whose graduates may continue to postgraduate training upon graduation ("residency").

Curricular mapping

To demonstrate and justify the need for this project, we engaged the Faculty’s Curriculum Mapping Unit (CMU), who are responsible for capturing, documenting, and managing the MD undergraduate curriculum, and who support accreditation and curriculum renewal projects. We provided the CMU with a series of 14 MeSH terms: gender, gender identity, gender dysphoria, sexual and gender minorities, gender minority, transgender persons, LGBTQ persons, queer, intersex persons, gender non-conforming, health services for transgender persons and health disparities. Our search identified only 10 sessions across the entire four-year undergraduate MD program that were tagged with one or more of these MeSH terms. At this early stage, we did not undertake a thorough assessment of the quality and depth of content that was tagged internally as being relevant to these topics; however, we did note that based on the abstracts and activity objectives associated with these materials, some appeared irrelevant to the search parameters, some used outdated, binary, or cis-centric language, some focused on pathologies and others were very general in their scope. Rather than robust opportunities to learn about the health of intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people’s health, this preliminary mapping of the curriculum signaled the lack of attention being paid to a variety of broadly connected topics and demonstrated the need for this project.

F unding and timeline

We received funding for this curricular audit project from the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Medicine Strategic Investment Fund, which invests up to $2 million per year in projects which advance the faculty’s strategic goals. Our project was funded as an education-related project, as part of the Fall 2020 round. We also received in-kind support from the Center for Gender and Sexual Health Equity. With these funds we were able to pay the 1-year part-time salary of a project lead, the 1-year part-time salary of an Undergraduate Academic Assistant, offer honorariums to various consultants that were engaged throughout the project, and offer a randomized raffle to incentivize participation in our student and faculty surveys. The project was supported by a Principal Investigator (PI), who is a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Faculty, and works as a family physician and family planning provider. Our project began in January 2021 and ended in April 2022, with the first 8 months dedicated to developing our audit framework and tools, and the second 8 months dedicated to piloting the audit with the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine undergraduate curriculum and generating a report of findings and recommendations resulting from that pilot audit.

Academic advisory committee

Our audit development process began with the establishment of an Academic Advisory Committee, comprised of UBC faculty and staff with expertise in education, curriculum, and pedagogy; equity, diversity, and inclusion principles; the health of intersex, trans and Two-Spirit people; and the training and credentialling of students who are working toward careers as service providers. The Academic Advisory Committee included some members who were trans, and some who were parents of trans youth. The Academic Advisory Committee met monthly throughout the 8-month development phase and provided guidance on the process. At the early stages, the Academic Advisory Committee identified the need for auditing formal, informal and hidden elements of the curriculum.Citation23–25 Rather than limiting our scope to only standardized materials (didactic lectures, clinical skills manuals, etc.), we were interested in assessing the values, norms, and beliefs conveyed in the delivery of the curriculum, as well as the experiences of intersex, trans and Two-Spirit medical students. Throughout the 8-month development process, we also met with key individual faculty members and relevant committees who were introduced to the project, and subsequently invited to provide guidance on the direction, scale, and scope of the audit, as well as the specific tools that we developed to assess the curriculum.

Medical education curricular audit literature review

We reviewed and annotated 19 articles that detailed medical education curricular audits. During this non-exhaustive search, we looked specifically at audit-related methodologies rather than results. Importantly, we found no articles which described medical education curricular audits focused on our areas of interest; namely, the health of intersex, trans and Two-Spirit people, and the accurate and precise use of gender and sex concepts in medical education. This gap further justified the need for our project.

The focus of the curricular audits we reviewed fell into three broad themes: (1) audits undertaken in response to critical gaps in medical education pertaining to the health of marginalized populations (disabled people, LGBTQ + people, cisgender women);Citation19–22,Citation26–29 (2) audits focused on examining the extent to which particular health-related topics or skills were being integrated into the curriculum (e.g., dermatology, HIV postexposure protocol adherence, informatics, pain management, ultrasound training, dental, surgical skills);Citation30–38 and, (3) audits focused on examining how students were being taught core competencies, as well as ethical and code of conduct responsibilities (ethics, law, professionalism).Citation39–41 This review provided us with a range of options for how to conduct our own audit. In general, the articles advocated for an integration approach as opposed to the development of new separate content to address curricular gaps. Many deployed multipronged methodologies for assessing and auditing the medical education curriculum.

In terms of engaging students in the audit process, there were three primary approaches undertaken across the 19 studies: (1) engaging student collaborators across multi-institution audits, who collect and code curricular data and present their findings to faculty responsible for organizing curriculum,Citation39 (2) engaging students as auditors, who document instances of particular kinds of curricular content as they encounter it during their studies,Citation21,Citation22,Citation40 and (3) engaging students via surveys, where feedback on the quality and quantity of curriculum is collected, and where competencies and confidence in performing particular skills is assessed.Citation33,Citation34,Citation37,Citation41 In terms of engaging faculty and staff in the audit process, there were two primary approaches undertaken across the 19 studies: (1) qualitative and quantitative methods like interviews, questionnaires, and surveys, to ascertain the degree to which some or all faculty are covering, in theory or practice, particular content or competencies in their teaching, and to better understand factors that they perceived as impacting their ability to deliver specific curricular content,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36 (2) having faculty submit or make available their materials for review by independent reviewers and/or other faculty, deans, and other stakeholders.Citation20,Citation21 Finally, in terms of approaches to auditing the content of the standardized curriculum, five primary approaches were undertaken: (1) comparing the curriculum to preexisting standards, assessment tools, competencies, and learning outcomes,Citation26,Citation32,Citation33,Citation41 (2) conducting a historical comparison between current and past curricula to assess changes over time,Citation28,Citation29 (3) auditing only publicly available information, such as that which is available via an institution’s website,Citation36 (4) assessing the quality of curriculum mapping tags,Citation21 (5) developing purpose-built tools and checklists, built to address topic areas and learning outcomes, proportion of curricular time dedicated to a topic, sequencing of the topic within the program, as well as methods of teaching and evaluation.Citation38

Focus groups

We conducted two paid focus groups with currently registered University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine undergraduate medical students. After having received ethics approval, we recruited 15 participants using closed Facebook groups created for each of the graduating class cohorts, and by having our recruitment materials circulated by various Faculty of Medicine student clubs. One focus group included eight cisgender medical students who were compensated $30 for their participation in a 90-minute group interview. The second focus group included five medical students who identified as intersex, trans, or Two-Spirit who were compensated $60 for their participation in a second, separate 90-minute group interview. Paid one-on-one interviews were conducted with two trans medical students who were unable to attend the scheduled focus groups. Focus groups and one-on-one interviews were held virtually on Zoom, where camera use was optional, and pseudonyms were assigned to each participant. The focus groups were facilitated by the Undergraduate Academic Assistant, who also transcribed, coded, and thematically analyzed the findings. The Undergraduate Academic Assistant presented their findings at an Academic Advisory Committee meeting. Using the focus group data, we were able to: a) gain understanding of how the curriculum functions and how all the elements of the curriculum come together in the students’ experiences, b) identify what the students felt were the strengths, gaps, and opportunities for improvement within the curriculum and c) gain insight into the students’ perspectives on the hidden curriculum, including learning environment and climate, peer interactions, and extra-curricular learning opportunities. The findings from these two focus groups informed the development of our student survey and allowed us to determine how and where to concentrate our limited time and resources when it came to auditing the content of the standardized curriculum.

Expert consultation interviews

While the Undergraduate Academic Assistant was conducting the two focus groups with medical students, the Project Lead conducted 10 expert consultation interviews. After having received ethics approval, we purposively recruited 10 participants who were identified by the Academic Advisory Committee or who were in the professional network of the Project Lead. These 10 experts were recruited due to their, (a) experience developing or delivering medical education curricula with a particular focus on content specific to the health and health care needs of intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people; (b) having conducted medical education curricular audit projects, (c) having expertise in the various dominant ideologies identified as pertinent to the project (endosexnormativity, cisnormativity, transnormativity, gender essentialism, and the coloniality of gender), (d) having clinical experience in serving intersex, trans, or Two-Spirit patients, (e) having knowledge of gender-affirming care service provision in British Columbia and thus able to identify gaps in current in-service provider knowledge when it comes to serving intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit patients; and (f) having lived experience as an intersex, trans, or Two-Spirit person. Interviews were held virtually on Zoom, where camera use was optional, and pseudonyms were assigned to each participant. Each participant was offered a $50 honorarium for their time and expertise. Interviews were conducted by the Project Lead and interviewees were asked questions relevant to their experiences and expertise. Interview recordings were transcribed, coded, and thematically analyzed, and the Project Lead presented the findings at an Academic Advisory Committee meeting. Using the interview data, we were able to: (a) gain understanding of how others had approached medical curricular audit projects, learning about best practices and stumbling blocks from the perspective of those who had undertaken similar projects as ours; (b) brainstorm how to assess and measure dominant ideologies within medical education curriculum, where dominant ideologies are abstract concepts with multiple components; and (c) identify gaps in current knowledge and skills among in-service physicians to identify opportunities to address those gaps during our audit.

Community advisory committee

Having developed initial drafts of the audit framework and tools, we held two 90-minute Community Advisory Committee meetings. After receiving ethics approval, we purposively recruited 15 participants to this Community Advisory Committee, each of whom self-identified as intersex, trans, and/or Two-Spirit. Participants were also diverse in terms of race, gender identity, sexuality, age, and ability, and we aimed to create a balanced group, where some participants had academic/research experience and others did not. Participants were primarily recruited through Facebook groups and were paid $75 for each of two Community Advisory Committee meetings. Meetings were held virtually on Zoom, where camera use was optional, and pseudonyms were assigned to each participant. Ultimately, three invitees declined participation, leaving the Community Advisory Committee without sufficient representation of intersex and Two-Spirit people. We therefore supplemented the Community Advisory Committee feedback process by reengaging two of the individuals from the expert consultation interviews – these two individuals were invited to provide feedback on the audit tools and were paid for their time. A week prior to the first Community Advisory Committee meeting, participants were sent the draft audit tools for their review and consideration, along with a list of guiding questions to guide their review. Participants were asked to reflect on: (a) whether the survey questions were sufficiently clear or could be subject to misinterpretation and misunderstandings, (b) whether the surveys and purpose-built audit question list were sufficiently comprehensive, or whether anything important was missing, (c) how survey respondents might react to certain questions and whether there were strategies to mitigate respondent shame or defensiveness in how questions were phrased, (d) whether there were items of redundancy that could be removed or refined, (e) whether the purpose-built audit question list effectively and comprehensively measured what it aimed to measure, and whether there was anything missing from how we were approaching the measurement of each of the dominant ideologies of concern.

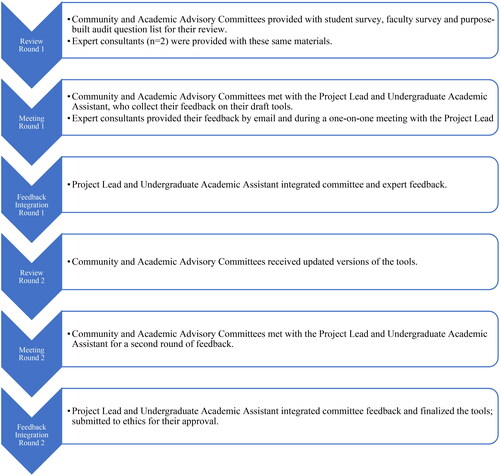

The Community Advisory Committee scheduled meetings to coincide with the project’s Academic Advisory Committee meetings, to create a parallel process of reviewing and reflecting on the draft tools (see ). After the initial Community Advisory Committee meeting, we transcribed the meeting recording, and generated a list of recommendations and revisions based on that transcript. We considered this list of recommendations and revisions alongside a list of recommendations and revisions generated from the parallel Academic Advisory Committee meeting. The Undergraduate Academic Assistant updated all the tools with guidance from the Project Lead. We then circulated the updated tools for a second time to both the committees. We scheduled a second set of meeting with both the Community and Academic Advisory committees. After the second Community Advisory Committee meeting, we transcribed the meeting recording, and generated a list of recommendations and revisions based on that transcript. We considered this list of recommendations and revisions alongside a list of recommendations and revisions generated from the second, parallel Academic Advisory Committee meeting. Lastly, the Undergraduate Academic Assistant updated and finalized the tools with guidance from the Project Lead.

Audit framework and tools

Informed by our literature review, the focus groups with medical students, the expert consultation interviews and with guidance from our two committees, our audit ultimately involved three core components.

First, we created a survey for faculty, staff, tutors, preceptors, and others involved in the design and delivery of the undergraduate medical education curriculum (Supplementary Material B). In addition to collecting respondents’ sociodemographic information, this survey included a section on personal values, beliefs, and attitudes open to all respondents, as well as subsections on teaching, curriculum design and development, and faculty development that were open to respondents with experience in those areas. We were interested in collecting information about not only whether, when, and how respondents were teaching about gender, sex, intersex, trans and/or Two-Spirit patients. We were also interested in ascertaining the factors that they understood as impacting their ability or willingness to design or deliver curricular content about these topics and populations.

Second, we created a student survey, open to all current and some recently graduated medical students (Supplementary Material C). As with the faculty survey, we collected sociodemographic information and included a section on personal values, beliefs, and attitudes. We also asked students to reflect on up to 3 instances when they had had a chance to learn about intersex, trans or Two-Spirit people, and to reflect on the content and quality of that education. Students were also asked to share whether they had experienced or witnessed discrimination on the basis of gender or sex. We offered specific questions only to Indigenous students, and then only to intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit students, to better understand their experiences.

Finally, we developed a purpose-built audit question list (Supplementary Material A). This question list was used to audit and assess the standardized elements of the MD undergraduate medical curriculum, which all MD undergraduate medical students are exposed to, no matter who is doing the teaching. In this case, that meant focusing on years 1 and 2 of the four-year program. We divided the question list into five major categories focused on five dominant ideologies (ideologies of sex/endosexnormativity; ideologies of gender/cisnormativity; transnormativity; Indigeneity, the coloniality of gender and Two-Spirit Health; intersectionality). Each section begins with a detailed description of the dominant ideology, along with a series of questions relevant to that dominant ideology, meant to capture the breadth and complexity of each ideology and how it might be operationalized within the curriculum. This portion of the audit was conducted by the Project Lead, the Undergraduate Academic Assistant, and two FLEX students – medical students enrolled in Flexible and Enhancing Learning courses, which provide these students with opportunities to pursue research, community-engagement, and other scholarly activities. Rather than having faculty submit their curricular materials directly, we requested and were granted access to current and archived materials via the faculty’s integrated teaching and learning platform, Entrada. As such, we could review materials without having to approach each faculty person one at a time. With this streamlined access to the curriculum and informed by insights from the student focus groups and meetings with key faculty and committees, we ultimately audited all clinical and communication skills materials and all case-based learning scenarios (52 scenarios). We also reviewed all content (lectures, readings, webinars) associated with eight specific weekly themes (cancer detection and management, infertility, pregnancy, birth and newborns, sexual functioning, sexuality, adolescent health and development, abnormal vaginal bleeding). Project Lead, Undergraduate Academic Assistant and FLEX student auditors wrote individual reports for the element of the curriculum that they were assigned to review, and these reports were compiled (along with results from the two surveys) into a final findings and recommendations report that was shared with the Faculty of Medicine at the conclusion of the project.

Findings

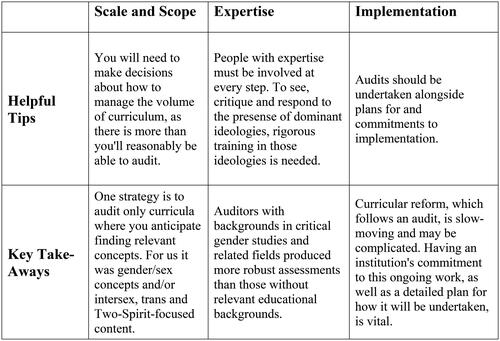

Having undertaken this 16-month audit framework and tool development and piloting project, we include here our reflections on the strengths, limits, and challenges, in order to inform the uptake and adaptation of this approach by other institutions. , “Key Take-Aways and Helpful Tips for Undertaking a Curricular Audit of Medical Undergraduate Curricula” provides a high-level, at-a-glance overview of these lessons learned and broad guidance.

Figure 2. Key take-aways and helpful tips for undertaking a curricular audit of medical undergraduate curricula.

Managing the volume of standardized curricular content

We were aware throughout this project that there would be more curricular content than we would have the time and resources to audit, in particular weekly lectures which comprise approximately 20 h a week of material, across two years of courses. We explored several options for managing the volume of the curriculum. One option was to randomly select materials to review, for example, by auditing one random lecture each week. This approach would have facilitated our reviewing materials across the curricular blocks, on a range of topics. Our concern, however, was that this approach would have us inadvertently overlooking the curricular materials focused on intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people. Instead, we relied on key stakeholders (faculty and staff, as well as students who participated in our focus groups and survey) to help identify places where we were likely to find discussion of intersex, trans and/or Two-Spirit patients, and places where gender and sex concepts were being relied on to discuss health care risks, patients’ screening, and assessment needs, etc. As such, we were able to comment on how intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people were being discussed in some key curricular areas, by focusing our efforts on those areas. We were also able to identify some chronic shortcomings with how gender and sex were being mobilized in the materials that we viewed (e.g., concepts being misused, confused, conflated, treated as binaries, treated as crude proxies). We expect these shortcomings to be similarly persistent and recurring through the entirety of the curriculum and are reasonably confident that our findings are applicable to the elements of the curriculum that we did not review. It is possible that there were superb examples of conceptual precision and patient inclusion in lectures that we did not audit; however, we would have expected the faculty, staff, and students to have pointed us to those exemplary materials.

The importance of compensated expertise

Our project was led by one person with extensive clinical experience (the PI), and one person with degrees in critical gender studies and trans studies, whose work focuses on trans health (Project Lead). We supplemented this leadership expertise with numerous opportunities to learn from and be guided by other experts, including advisors with lived experience as intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people during the consultation interviews, as well as during frequent Academic and Community Advisory Committees meetings. We offered compensation to all expert consultants, community, and academic advisors for their time, although some refused the compensation as they saw their involvement as a component of their paid work. This expertise was vital to the success of this project – both in terms of formulating an approach to auditing curricular materials, and in terms of understanding the complex findings and making corresponding, concrete recommendations for improvement. As aforementioned, we engaged the project’s Undergraduate Academic Assistant (a paid position) and FLEX medical students as student auditors, tasked with reviewing aspects of the curriculum and writing reports of their findings using the purpose-built audit question list. These reports were of varying depth and nuance, and we noted that those student auditors with past education and interest in the fields of gender and sexuality studies produced more skillful reports. As such, we recommend that institutions undertaking similar audit projects engage, at all levels, project leaders, advisors, and auditors who can understand the complex dominant ideologies and frameworks being explored. While it is likely possible that an auditor could be taught about endosexnormativity, cisnormativity, transnormativity and other complex discourses, for example, projects such as these will only benefit from having people involved who are already well versed in these concepts, able to identify instances of these norms with ease and familiar with strategies for combating concept misuse, stereotypes, and erasure. In the same way that curricular content ought to be delivered by instructors with the relevant competencies, undertaking an audit such as this requires that auditors and others involved are similarly equipped with expertise on the subject matter, and then compensated for their time and expertise.

Applicability and tailoring

In the various tools we created for this audit, we discuss Indigeneity, Two-Spirit people, and the coloniality of gender which has been problematically reified by and embedded into the undergraduate medical education curriculum in Canada. We contend that this approach is applicable and appropriate for curricular audits undertaken across Canada and the United States. In other contexts, however, we recommend that this content be appropriately tailored. For example, the term Two-Spirit is not used globally, and curricular audits in other countries will need to attend to the ways that Brotherboy/Sistergirls (Australia), travesti (Peru, Brazil, Argentina), Kathoey (Thailand), Fa’afafine/Fa’afatama (Samoa) and other people who claim various Indigenous and culturally specific gender terms are, or are not, being included in the curriculum. A nuanced understanding of the impacts of colonization on gender/sex (and sexuality) will be required in each geopolitical context.

Further, the need for accuracy and precision in the use of gender and sex concepts is not limited to Canada and is not limited to content focused on intersex and trans people – all medical education ought to carefully attend to these concepts. For instance, understanding symptoms and risk factors requires that physicians ascertain whether some aspect of gender or some aspect of sex is at the root of observed presentations. For instance, ensuring that patients receive appropriate screening also requires that physician do not conflate and confuse sex and gender – despite cervical cancer screening being recommended for women, it is ultimately people with cervixes who require cervical cancer screening, regardless of how they identify. As such, regardless of whether specific curricular content is thought to be ‘relevant’ to intersex, trans, or Two-Spirit people, gender and sex concepts are used throughout medical education and their misuse has profound negative impacts on patients of all kinds. Indeed, it is the pervasive misuse and endosex-cisnormative use of gender and sex concepts which lends itself to the erasure of intersex, trans and Two-Spirit people from the curriculum.

Low survey response rate

Curricular audit projects that we reviewed during our literature review, frequently cited low survey response rate as a concern or limitation.Citation33,Citation34,Citation37,Citation41 Our two surveys also generated what might be classified as low response rates, with sixty students and sixty faculty participating in each respective survey. Our surveys were only open for a relatively short data collection period (approximately 6 wk), due to the overall limited timeline of our project. The surveys were also purposively lengthy, wanting to capture a diversity of measurements and insights from respondents. As such, they required 30 min or more to complete. Finally, we suspect that some prospective faculty respondents did not understand the relevance of the topic to their work or role, and as such did not participate due to that perceived irrelevance. However, for our purposes, 60 respondents for each survey helped develop fruitful and productive outcomes. The surveys were not ‘research’ in the strictest sense; we were not concerned with ensuring that the survey respondents were representative of the entire student or faculty population. Instead, we used the surveys to glean additional insights that were not available to us had we only reviewed the standardized curriculum. The surveys allowed us to contextualize some of our audit findings. For example, where we found little to no content focused on intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people, the faculty survey revealed factors contributing to that lack of inclusion. Or, where the auditors found problematic curricular content, the students surveyed shared their own experiences of that content, allowing us to validate our impressions of the problems, and supplement our final report with insights directly from students. We ultimately achieved our goals, despite the relatively low overall number of respondents. The surveys added another layer of depth to our audit analyses, gave insights into student and faculty competence and confidence, and allowed us to explore the hidden curriculum and learning environment.

Curricular component decipherability

In section 3 of the student survey, we asked respondents to identify 1–3 instances where they recalled being taught about the health and healthcare needs of intersex, trans, and/or Two-Spirit people. They were then asked to share their impressions of the strengths and limitations of that teaching. However, having students provide the course code and the teaching modality was insufficient, on its own, to determine with precision which element of the curriculum they were referring to. In some cases, the survey respondents used the provided write-in box to tell us exactly which lecture, case-based learning scenario, clinical skills material or assigned reading they were discussing. In other cases, however, we could not deduce which element of the curriculum an individual student was discussing, nor could we determine when individual students were talking about the same material – except when the write-in box provided us those much-needed additional context clues. As such, we recommend that section 3 of the survey be amended and tailored for each institution, where students are asked to provide very specific details about the curricular material, so that all reflections can be properly attributed and subsequently compiled and compared when students are discussing their impressions of the same content.

Dissemination and implementation

Our project was specifically focused on developing a framework, method, and associated tools for auditing curricula, and piloting that approach. We compiled our findings and associated recommendations into a 90-page final report, which has been shared with our institution’s Faculty of Medicine, alongside a short summary bulletin and an at-a-glance summary of recommendations.

The decision to undertake an audit ought to occur alongside institutional commitment to acting on recommendations that result from that work, and a plan for how implementation will occur. This is vital since medical education curricula can be organized in fragmented ways (e.g., where no individual lecturer is necessarily aware of what else is being taught that week, on that topic), and where authority to alter curriculum can be complicated by concerns about academic freedom, for example. In the absence of institutional commitment and plans for implementation and uptake, a curricular audit serves as a performative act, rather than a springboard for curricular reform and associated structural change. The vital work of disseminating our final report and implementing its recommendations is ongoing and proceeding with minimal involvement from our team since the project’s funding for the team has come to an end. Our core team (the PI and Project Lead) have been available, on an ad hoc basis, to assist with this process; however, we have had to make tough decisions as to when and where we are able to offer additional guidance and expertise beyond that which is contained in our various reports. In the year since we completed our audit, we have attended numerous meetings hosted by various curriculum committees, met with key faculty responsible for various aspects of the curriculum, and made sure that the findings reports have been made available to individuals who request them or who reach out and detail that they are undertaking similar or complementary work. We have offered one stand-alone training as part of the university’s Respectful Environments, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion office, and have been engaged in thoughtful and productive email and virtual meeting exchanges with individuals working in the admissions and assessment departments. At the time of writing, a small number of ‘low hanging’ recommendations have been implemented – the process of curricular reform is slow-moving, and often done in piecemeal ways. The ongoing and future work of improving the curriculum based on the audit findings is ultimately the responsibility of the Faculty of Medicine. Our hope is that the Faculty of Medicine will invest the same level of time, financial resources, personnel, and passion into the implementation as they did the developing and piloting of the audit. Professional and faculty development will be key, so that those tasked with delivering the updated curriculum, are prepared to do so in ways that reflect the stated values of the institution, and in ways that prepare medical students to meet the needs of their diverse patients. We are hopeful that implementation, curricular reform, and faculty development will be ongoing, and look forward to reporting on the state of the curriculum in a few years’ time.

Auditing the curriculum alone is insufficient if curricular reform based on the audit does not occur. Indeed, curricular audits and the reform and professional development work that results from them are never simply one-and-done, but iterative, ongoing activities that are only possible with long-standing internal champions and leadership, repeated external pressures, continuous financial and time commitments, and guided by the principles of transparency and accountability.

Insights

Medical education is a critical site of intervention, to better prepare health care providers with the language, skills, competencies, and confidence to serve their patients, and to improve the health and healthcare experiences of patients who are marginalized and minoritized, including intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people. Medical education ought not only provide medical students with exposure to intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit patients in theory (e.g., by providing definitions of what these terms mean), but must also prepare medical students with the practical skills that they will need to meet the needs of these patients. Even beyond more purposeful inclusion of these patient populations, medical education ought to mobilize the concepts of gender and sex accurately and precisely – gender and sex are complex, complicated, and distinct yet interconnected variables, the misuse of which has profound negative impacts on all patients.

The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada adopted CanMEDS in 1996, which includes strategies for enhancing physician training to improve patient care. Among other roles, the CanMEDS competencies state that health care providers need to be health advocates (which would require that they are familiar with the health care needs of intersex, trans, and Two-Spirit people) and medical experts (which would require that they understand how gender and sex impact health, where these concepts are mobilized accurately, precisely and inclusively). Further, the Medical Council of Canada’s Objectives for the Qualifying Examinations details that in regard to Indigenous patients, candidates must “demonstrate an awareness of the root causes of the inequitable health care and health outcomes experienced by Indigenous Peoples; understand the importance of and demonstrate anti-racist, culturally safe, trauma- and violence-informed care; articulate the inherent Indigenous and Treaty Rights (e.g., Medicine Chest Clause) relevant to the health of Indigenous Peoples; apply population health principles in understanding and advocating for Indigenous Peoples’ health at the individual, community, institutional (e.g., hospitals), and societal levels.”Citation42 In alignment with the requirements of the qualifying exam, it is imperative that the undergraduate MD curriculum equip medical students to practice with Indigenous patients, including Two-Spirit, who are oftentimes overlooked.

In this paper, we have detailed our approach to auditing undergraduate medical education curriculum for measures of endosex-, cis- and transnormativity, as well as the coloniality of gender, for the inclusion of intersex, trans and Two-Spirit people, and for the accurate mobilization of gender and sex variables which impact health. We have provided the tools that we developed for this purpose, detailed our method, and reflected on our approach. Our goal is for other institutions to undertake similar audits, inspired and informed by our process. As medical training institutions increasingly articulate the values of inclusivity and equity in their mission statements and are diversifying their student populations, these efforts are vital. As evidence continues to document the negative health care experiences and outcomes of intersex, trans and Two-Spirit people, enhancing physician training in these areas is not only a matter of meeting exit competencies, but also a matter of meeting ethical, legal and professional responsibilities. Intersex, trans and Two-Spirit people – among others – deserve and desperately need healthcare providers who are equipped to meet their needs and provide them with affirming care. Auditing medical education curriculum to better understand what is – and what is not – being taught to future doctors, and then undertaking the challenging but rewarding task of curricular reform to improve their training, is imperative.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (300.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (231.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (261.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the incredible support and guidance of the Academic Advisory Committee members, not otherwise named as co-authors on this paper. Thank you to Hannah Kia, Harper Keenan, Antoine Coulombe, Hélène Frohard-Dourlent, and Kaitlyn Kraatz. Thank you to our anonymous expert consultants and community advisory committee members.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Costello CB. Beyond binary sex and gender ideology. In: Boero N, Mason K, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Body and Embodiment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2021. p. 199–220.

- Ashley F. ‘Trans’ is my gender modality: A modest terminology proposal. In Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2022. p. 22.

- Pruden H, Salway T. ‘What and who is Two-Spirit?’ in health research. CIHR Meet the Methods Series, Issue 22020. https://cihr-irsc. gc.ca/e/52214.html.

- Chan B, Skocylas R, Safer JD. Gaps in transgender medicine content identified among Canadian medical school curricula. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):142–150. doi:10.1089/trgh.2016.0010.

- Dimant OE, Cook TE, Greene RE, Radix A. Experiences of transgender and gender nonbinary medical students and physicians. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):209–216. doi:10.1089/trgh.2019.0021.

- Heng A, Heal C, Banks J, Preston R. Clinician and client perspectives regarding transgender health: A North Queensland focus. Int J Transgend. 2019;20(4):434–446. doi:10.1080/15532739.2019.1650408.

- Bauer G, Hammond R, Travers R, Kaay M, Hohenadel K, Boyce M. ‘I don’t think this is theoretical; This is our lives”: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(5):348–361. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004.

- Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG, Greene R, Radix AE, Morrison SD. Transgender health care: Improving medical students’ and residents’ training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:377–391. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S147183.

- Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. J Am Med Assoc. 2011;306(9):971–977. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1255

- Park JA, Safer JD. Clinical exposure to transgender medicine improves students’ preparedness above levels seen with didactive teaching alone: A key addition to the Boston University Model for teaching transgender healthcare. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):10–16. doi:10.1089/trgh.2017.0047.

- White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: Medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(3):254–263. doi:10.1080/10401334.2015.1044656.

- Khalili J, Leung LB, Diamant AL. Finding the perfect doctor: Identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender-competent physicians. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1114–1119. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302448.

- Logie C, Rwigema M. ‘The normative idea of queer is a white person’: Understanding perceptions of white privilege among lesbian, bisexual and queer women of color in Toronto, Canada. J Lesbian Stud. 2014;18(2):174–191. doi:10.1080/10894160.2014.849165.

- Greensmith C. Desiring diversity: The limits of white settler multiculturalism in queer organizations. Studies Ethn National. 2018;18(1):57–77. doi:10.1111/sena.12264.

- Liang JJ, Gardner IH, Walker JA, Safer JD. Observed deficiencies in medical student knowledge of transgender and intersex health. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(8):897–906. doi:10.4158/EP171758.OR.

- Callaghan W. Sex and gender: More than just demographic variables. J Military Veteran Fam Health. 2021;7(s1):37–45. doi:10.3138/jmvfh-2021-0027.

- Sandar AG. Consequences of the Conflation of ‘Sex’ and ‘Gender’ on Trans Healthcare [Dissertation]. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University; 2022.

- Greaves L, Ritz SA. Sex, gender and health: Mapping the landscape of research and policy. IJERPH. 2022;19(5):2563. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052563.

- Miller VM, Rice M, Schiebinger L, et al. Embedding concepts of sex and gender health differences in medical curricula. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(3):194–202. doi:10.1089/jwh.2012.4193.

- Smith A, Wians R, Hanback S, Fowler A, Edwards A, Walter L. Sex and gender education in emergency medicine: A residency-based curricular audit. Western J Emerg Med. 2019;20(Supplement):S9. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/17t279v6

- Song MM, Jones BG, Casanova R. Auditing sex- and gender-based medicine (SGBM) content in medical school curriculum: A student scholar model. Biol Sex Differ. 2016;7(S1):93–99. doi:10.1186/s13293-016-0102-x.

- Stickley L, Sechrist D, Taylor L. Analysis of sex and gender content in allied health professions’ curricula. J Allied Health. 2016;45(3):168–175. PMID: 27585612

- Lehmann LS, Sulmasy LS, Desai S, ACP Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee Hidden curricula, ethics, and professionalism: Optimizing clinical learning environments in becoming and being a physician: A position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(7):506–508. doi:10.7326/M17-2058.

- Leong R, Ayoo K. Seeing medicine’s hidden curriculum. CMAJ. 2019;191(33):E920–E921. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190359.

- Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: Qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 2004;329(7469):770–773. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770.

- DeVita T, Bishop C, Plankey M. Queering medical education: Systematically assessing LGBTQI health competency and implementing reform. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1510703. doi:10.1080/10872981.2018.1510703.

- Miller VM, Kararigas G, Seeland U, et al. Integrating topics of sex and gender into medical curricula – lessons from the international community. Biol Sex Differ. 2016;7(S1):19–24. doi:10.1186/s13293-016-0093-7.

- Trollor JN, Eagleson C, Ruffell B, et al. Has teaching about intellectual disability healthcare in Australia medical schools improved? A 20-year comparison of curricula audits. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):321. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02235-w.

- Trollor JN, Ruffeel B, Tracey J, et al. Intellectual disability health content within medical curriculum: An audit of what our future doctors are taught. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(105):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0625-1

- Blitz J, van Rooyen M, Cameron D. Using an audit of medical student behavior to inform curriculum change. Teach Learn Med. 2010;22(3):209–213. doi:10.1080/10401334.2010.488207.

- Bowman S. Audit of Curriculum Content to Assess the Integration of CASN Informatics Competences in a BScN Program [Masters thesis]. St John’s, NL: Memorial University of Newfoundland; 2015.

- Davies E, Burge S. Audit of dermatological content of U.K. undergraduate curricula. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(5):999–1005. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09056.x.

- Jacob J, Paul L, Hedges W, et al. Undergraduate radiology teaching in a UK medical school: A systematic evaluation of current practice. Clin Radiol. 2016;71(5):476–483. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2015.11.021.

- Leonardi M, Luketic L, Sobel ML, Toor K, D’Souza R, Murji A. Evaluation of obstetrics and gynecology ultrasound curriculum and self-reported competency of final-year Canadian residents. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40(12):1580–1585. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2018.03.012.

- McDonald DC, Godfrey J. A skills audit for the dental curriculum. Eur J Dent Educ. 1999;3(4):167–171. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.1999.tb00087.x.

- Mistry K, Yonezawa E, Milne N. Paediatric physiotherapy curriculum: An audit and survey of Australian entry-level physiotherapy programs. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):109. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1540-z.

- Seabrook MA, Woodfield SJ, Papagrigoriadis S, Rennie JA, Atherton A, Lawson M. Consistency of teaching in parallel surgical firms: An audit of student experiences at one medical school. Med Educ. 2000;34(4):292–298. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00513.x.

- Shipton EE, Bate F, Garrick R, Steketee C, Visser EJ. Pain medicine content, teaching and assessment in medical school curricula in Australia and New Zealand. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):110. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1204-4.

- Bandyopadhyay S, Shortland T, Wadanamby SW, et al. Global health education in UK medical schools (GHEMS) study protocol. J Glob Health Rep. 2019;3:e2019052. doi:10.29392/joghr.3.e2019052.

- Johnston C, Mok J. How medical students learn ethics: An online log of their learning experiences. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(10):854–858. doi:10.1136/medethics-2015-102716.

- Saad TC, Riley S, Hain R. A medical curriculum in transition: Audit and student perspectives of undergraduate teaching of ethics and professionalism. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(11):766–770. doi:10.1136/medethics-2016-103488.

- MCC Examination Objectives: Indigenous Health 78-9, Medical Council of Canada, 2021, https://mcc.ca/objectives/expert/key/78-9/