Abstract

Undernutrition and inflammatory processes are predictors of early mortality in the elderly and require a rapid and accurate diagnosis. Currently, there are laboratory markers for assessing nutritional status, but new markers are still being sought. Recent studies suggest that sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) has the potential to be a marker for undernutrition. This article summarizes available studies on the association of SIRT1 and undernutrition in older people. Possible associations between SIRT1 and the aging process, inflammation, and undernutrition in the elderly have been described. The literature suggests that low SIRT1 levels in the blood of older people may not be associated with physiological aging processes, but with an increased risk of severe undernutrition associated with inflammation and systemic metabolic changes.

Introduction

According to global demographics, by 2050, there will be more people over 60 years of age than those under 15, and a total population of 2.1 billion compared to 901 million in 2015 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division Citation2022). The aging of the population is associated with rising social costs, including the provision of adequate health services. Aging is a main risk factor for many serious diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular, metabolic, neurodegenerative diseases, and malnutrition.

According to the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), the definition of malnutrition is unambiguous, open-ended and often used to describe undernutrition (Cederholm et al. Citation2015). “Malnutrition” or “undernutrition” are equally used both in the literature and in clinical practice, with a slight preponderance for malnutrition to describe the inadequate supply of energy and nutrients. In this article, the above terms are used equivalently. The risk of malnutrition increases with age (Russell and Elia Citation2011) and occurs in 27% of the population and 50% of people living in health facilities (Cereda et al. Citation2016). In the elderly, malnutrition may be associated with inadequate nutrient intake, leading to changes in body composition, which reduce physical and mental function and deteriorate clinical outcomes (Morley Citation2001). Malnutrition is accompanied by inflammation, which increases the need for energy and protein (Rondanelli et al. Citation2016).

Various causes of malnutrition in the elderly include nutritional disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, and impaired chewing due to poor or absent dentition. Aging is associated with a loss of organoleptic qualities, such as reduced taste and smell sensation, as well as reduced physical activity, which can significantly affect nutrient intake and lead to malnutrition with potentially serious health consequences (Hickson Citation2006).

The incidence of malnutrition is estimated to be 5.8% (Robberecht et al. Citation2019), while the risk of malnutrition may affect one third of elderly people (Kaiser et al. Citation2010). This risk increases when patients have difficulty performing basic tasks of daily life (Tamura et al. Citation2013). In addition, it carries an increased long-term risk, and individual nutritional support can reduce the risk of malnutrition (Hickson Citation2006).

Elderly people may experience frailty owing to chronic inflammation which may lead to the development of eating disorders. Symptoms of frailty are mainly sarcopenia, including loss of skeletal muscle mass, dysfunction of the neuroendocrine and immune systems, cognitive and motor disorders, and disturbances in energy regulation (Clegg et al. Citation2013). In the elderly, sarcopenia and inflammation frequently co-occur with malnutrition (Morley Citation2010; Volkert et al. Citation2019). In many studies, oxidative stress, central obesity, serum albumin (Wu et al. Citation2009), inflammation (Leng et al. Citation2002, Citation2004, Citation2007, Citation2009), 25-hydroxy vitamin D (Hirani et al. Citation2013), and vitamin E (Ble et al. Citation2006) have been used as parameters to identify malnutrition, sarcopenia, and frailty. Recent studies suggest a link between malnutrition in the elderly and Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) (El Assar et al. Citation2018). This literature review aimed to investigate whether SIRT1 is associated with malnutrition and whether it can be used as a marker of malnutrition in the elderly, a population heavily affected.

Undernutrition

Criteria for diagnosing the risk of malnutrition

There are several criteria for diagnosing malnutrition. ESPEN distinguishes the following nutritional disorders: malnutrition, micronutrient abnormalities, and overnutrition (Cederholm et al. Citation2015). Malnutrition includes starvation-related weight loss, disease-related cachexia, frailty, and sarcopenia. The definition of malnutrition according to ESPEN is based on a decrease in body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg/m2 or unintentional weight loss >10% indefinitely or >5% in the past three months combined with a BMI < 20 kg/m2 for those aged 70 years or <22 kg/m2 for those aged ≥ 70 years or fat-free mass index < 15 and 17 kg/m2 in women and men (Cederholm et al. Citation2015), respectively. The Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) developed in 2020 new diagnostic criteria for undernutrition, including three phenotypic and two etiological criteria (de van der Schueren et al. Citation2020). According to GLIM, the diagnosis of undernutrition requires at least one phenotypic and etiological criterion (Cederholm et al. Citation2019; Jensen et al. Citation2019).

If malnutrition is suspected, screening tools should be used to quickly assess its risk. There are several screening tools including the Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA) (Burns, Brayne, and Folstein Citation1998; Rubenstein et al. Citation2001; Vellas et al. Citation2006), the Nutrition Risk Screening (NRS-2002) (Liu, Zhang, et al. Citation2012), the Subjective Global Assessment Short Form (SGA) (Allard et al. Citation2020), and the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) The MNA is currently the most widely used screening tool for assessing malnutrition in older people. Donini et al. (Citation2016) evaluated several screening tools, such as MNA, NRS-2002, and MUST, and revealed that MNA was the best tool for predicting survival in well-nourished older people in nursing homes. The procedures used for detecting malnutrition are presented in .

Table 1. Instruments to identify the risk of malnutrition.

Laboratory indicators of nutritional status

The most important and common blood indicators used in the diagnosis of malnutrition include visceral proteins (Volpi et al. Citation2001), such as albumin, prealbumin, and retinol-binding protein, which are primarily synthesized in the liver. Low protein and energy intake, impaired liver synthesis, and inflammation in the body contribute to a decrease in visceral protein levels. Acute inflammation increases protein production, whereby the liver alters protein synthesis to reduce the synthesis of visceral proteins. In turn, the level of visceral protein correlates with the severity of the damage.

Although malnutrition is often associated with inflammation, the role of inflammatory biomarkers in malnutrition remains unclear. Above all, the biomarkers have low specificity and the presence of inflammation has a strong effect on visceral proteins in the serum. The uncertainty of the role of biomarkers is confirmed by the fact that their role has not been investigated in large randomized controlled studies (Cholewa et al. Citation2017).

Zhang et al. discussed the role of biomarkers in assessing the severity of malnutrition in the elderly and considered validated tools for assessing nutritional status (Zhang et al. Citation2017). They analyzed 111 observational and cohort studies with 52,911 participants from a variety of clinical settings. Biomarkers such as BMI and concentrations of albumin, hemoglobin, total cholesterol, prealbumin, and total protein among those at high risk of malnutrition assessed by MNA were significantly lower than those not at risk (p < .001). In the case of malnutrition, as determined by SGA and NRS 2002 in patients with acute illnesses, the predictive value of albumin and prealbumin was markedly reduced, leading to the conclusion that they are markers of inflammation rather than malnutrition. According to the authors, BMI, hemoglobin, and total cholesterol are useful markers of malnutrition in older adults.

The role of inflammation in the pathology of malnutrition

Inflammation plays a critical role in malnutrition pathophysiology. Weight loss is considered one of the most important criteria for malnutrition but disregarding other criteria may lead to an inappropriate diagnosis (Kirkland et al. Citation2013).

Inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), Interleukin-1 (IL1), Interleukin-6 (IL6), serotonin, and gamma interferon play a significant role in the development of cachexia, as they stimulate the release of acute phase proteins, protein breakdown in muscle, and fat breakdown. The increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines is influenced by the progressive increase in glucocorticoids and catecholamines as well as by the decrease in growth and sex hormones. Studies suggest that systemic inflammation associated with TNFα production is involved in the mechanism of muscle mass loss and anorexia. In addition, this mechanism may occur during aging (Godoy et al. Citation1996).

Researchers have suggested that aging causes a pro-inflammatory response, which may be associated with a gradual decline in physical activity and initially manifests as chronic, low-grade inflammation (Crossland et al. Citation2010). In the development of inflammation, the source of inflammatory molecules appears to be fatty tissue (especially visceral fatty tissue), which contributes to the increased activation and infiltration of immune cells, especially macrophages and neutrophils. Activated macrophages can stimulate lipolysis in visceral adipose tissue and increase the concentration of circulating free fatty acids (FFA) by signaling TNF-α/Toll-like receptor-4. While increased levels of FFA amplify macrophages to increase secretion of important anti-inflammatory molecules (such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6), these molecules also influence skeletal muscles, especially in those with a sedentary lifestyle. Increased levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and FFA appear to contribute to the activation of skeletal muscle proteolysis and insulin resistance, which are two major factors involved in different types of muscle atrophy. Degradation and reduction of the body proteins needed for the proper functioning of the organs, in favor of visceral proteins as an inflammatory reaction, gradually deteriorates the health of older people (Brocca et al. Citation2012). The occurrence of other comorbidities such as cancer or heart disease may contribute to the release of catabolic hormones such as cortisol, inflammatory cytokines, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS). This process may be associated with the risk of malnutrition and concomitant sarcopenia (Crossland et al. Citation2008).

Chronic systemic inflammation is an important factor in both sarcopenia and malnutrition. If inflammation can be regulated by pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6, malnutrition may be influenced. The pathway mediated by forkhead box 03 (FOX03), which activates the ubiquitin-proteasome system, is also involved in the inflammatory process, which primarily involves TNF-α and IL-6 (Sente et al. Citation2016). These cytokines may not only promote sarcopenia (Budui, Rossi, and Zamboni Citation2015) but also inflammatory malnutrition due to the interaction between inflammatory cells and organs, leading to reduced protein synthesis, increased protein breakdown, impairment of organ function, and the manifestation of clinical diseases associated with malnutrition (Jensen et al. Citation2010).

Inflammatory response in malnutrition

Malnutrition has been shown to be associated with inflammation (Bourke, Berkley, and Prendergast Citation2016). The proper development of the immune system is altered by malnutrition during critical periods in humans, including pregnancy, newborn puberty, and weaning (Keusch Citation2003; McDade et al. Citation2001). Chronic malnutrition and infection in children have been shown to weaken the immune response, leading to changes in immune cells and an increase in inflammatory mediators (Dülger et al. Citation2002). In addition, malnutrition in the early years of life increases the risk of chronic inflammation (Khoruts Citation2018; Latini et al. Citation2004; Martin-Gronert and Ozanne Citation2012), obesity (WHO 2004) (Swinburn et al. Citation2019), adverse metabolic alterations (Crispi, Miranda, and Gratacós Citation2018; Sommer et al. Citation2017), and intestinal dysfunction (Heijmans et al. Citation2008; Winick and Noble Citation1966) later in life.

The sirtuin family

Division and functions of sirtuins

Sirtuin proteins are involved in cellular processes, such as mitochondrial biosynthesis, lipid metabolism, apoptosis, cellular stress response, fatty acid oxidation, insulin secretion, and aging (Tanno et al. Citation2007). Eighteen different histone deacetylases (HDACs) have been identified in humans. HDACs are grouped into four classes (class I, II, III, and IV) and two families: classical and sirtuins (Gregoretti, Lee, and Goodson Citation2004). Sirtuins are a heterogeneous group of class III histone-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-deacetylase-dependent enzymes that are not sequentially similar to the classic HDAC family but have a high sequence similarity to silent information regulator 2 (SIR2), originally discovered in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Asher and Schibler Citation2011; Finkel, Deng, and Mostoslavsky Citation2009). Homologs of the yeast SIR2 gene have been detected in most organisms, including mammals (Haigis and Sinclair Citation2010). Seven isoforms of sirtuin, SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5, SIRT6, and SIRT7, have been identified in humans, which contain a conserved catalytic core domain composed of approximately 275 amino acids, except SIRT1 which is expressed. The sirtuins show different tissue specificities, target substrates, and cell localization (Price et al. Citation2012). A summary of all sirtuins, including the general distribution, the enzymes involved, and their locations, is given in .

Table 2. Division of sirtuins based on Manjula, Anuja, and Alcain (Citation2020), Yan et al. (Citation2018), Wu et al. (Citation2018), Gao et al. (Citation2018).

SIRT1

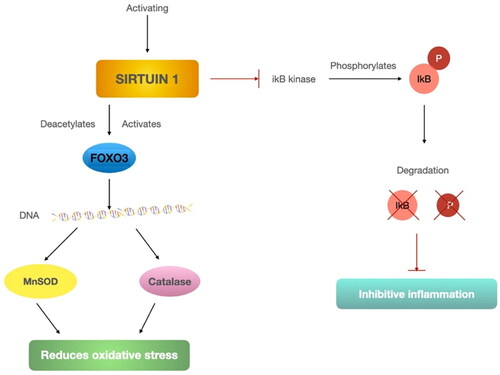

SIRT1 is a nuclear protein that deacetylates transcription factors and cofactors that regulate metabolic pathways in the circadian rhythm and energy metabolism (Nakahata et al. Citation2008). SIRT1 plays key roles in aging, inflammation, gene silencing, apoptosis, and stress resistance (Chung et al. Citation2010; Rahman et al. Citation2012; Yao and Rahman Citation2012). These functions are mainly performed by the deacetylation of histones, transcription factors, or coactivators such as p53, forkhead box 0 (FOX0), nuclear factor αB (NF-αB), and coactivator 1α of the peroxisome proliferator-activated γ receptor (PGC-1α) and heterodimer Ku70 (Yao et al. Citation2012). The system-related biological functions of Sirtuin 1 are shown in .

Table 3. Biological functions of sirtuin 1 in the human body (authors’ own study).

Modulatory function of sirtuins

Studies have shown that molecules that activate sirtuins in humans can offer broad health benefits with strong anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, and anti-cancer effects (Kugel et al. Citation2016).

The therapeutic potential of increased SIRT1 activity in mammals has been demonstrated in animal models and in early clinical studies, making this enzyme an attractive drug target (Bonkowski and Sinclair Citation2016; Hubbard and Sinclair Citation2014). Therefore, the modulation of sirtuin activity may play an important role in the development of new therapies for age-related and metabolic diseases. Most sirtuin activators described concern SIRT1, inhibitors of SIRT1 and SIRT2, and of the least concern are SIRT3 and SIRT5 (Alcaín et al. Citation2010). The most effective substance, activating SIRT1 by more than 10 times, is resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilben), a natural product of grapes and red wine (Gertz et al. Citation2012). In addition, a variety of synthetic resveratrol derivatives with changes at the B ring 4′ position may improve naturally occurring sirtuin activators and reduce toxicity to human cells, as well as increase the strength of SIRT1 activation and longer life in budding yeasts (Yang et al. Citation2007).

Reports have suggested that SIRT1 inhibitors and other sirtuin isoforms may also be useful (Chalkiadaki and Guarente Citation2015). Increasing advances in research and a growing number of structures of the sirtuin/inhibitor complex have aimed to develop potent and specific inhibitors targeting sirtuin (Schutkowski et al. Citation2014). Some pathophysiologies and sirtuin isoforms require inhibition rather than activation, for example, SIRT2 in neurodegenerative diseases (Donmez and Outeiro Citation2013). Studies have shown that inhibitors have the potential to be used as therapeutic drugs, including salermide, which inhibits the apoptosis of cancer cells, and suramine, an antiprotozoic agent. Sirtuin inhibitors are listed in .

Table 4. Sirtuin inhibitor compounds.

Nutritional regulation of SIRT1 expression

The activity of sirtuins depends on the availability of NAD + and its precursors, such as niacin and nicotinamide, which stimulate sirtuins (Bleeker and Houtkooper Citation2016). To explain the mechanism regulating SIRT1 expression, a reference should be made to the complex reactions catalyzed by sirtuins, in which NAD + is degraded to nicotinamide and adenine. The effects of these enzymes require NAD + resynthesis, which occurs in two reactions. In the first reaction, catalyzed by nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT), phosphoribose binds to nicotinamide, resulting in nicotinamide mononucleotide. Subsequently, adenine binding catalyzes nicotinic acid mononucleotide adenyltransferase. Studies in mice have shown that the increase in NAD + levels is due to an increase in NAMPT activity (Revollo, Grimm, and Imai Citation2004). In other studies, the administration of NAMPT to young and older mice also increased the expression and activity of SIRT1 (de Picciotto et al. Citation2016).

Calorie restriction

Today, one of the best-described and proven factors to increase the sirtuin activity is the limitation of energy intake. However, the effects of the level of nutrient deficiency, duration, and type of organism studied on sirtuin levels remain unclear.

The natural and synthetic activators of sirtuins, their possible health effects, and their sources in food are summarized in and .

Table 5. Natural activators of sirtuins and their sources.

Table 6. Synthetic activators of sirtuins.

SIRT1 expression increases in response to hunger or food restriction. During short-term famine, the cyclic AMP-activated factor (CREB) migrates through glucagon into the cell nucleus, binds to the promoter of the SIRT1 gene, and induces its expression. Simultaneously, high protein kinase A activity inhibits the translocation of the transcription factor that binds the carbohydrate response sequence (ChREBP) from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, thereby reversing its inhibitory effect on SIRT1 expression.

This process occurs during starvation for more than 24 h and is likely associated with deacetylation, and consequently, the inactivation of CREBP by SIRT1. When food is available, the glucose level in the cells increases, leading to rapid activation of ChREBP in the nucleus, where it suppresses the expression of the SIRT1 gene (Noriega et al. Citation2011).

In another study, a low-calorie diet was preferable to the Sirtuin-1 activator resveratrol. In patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, the calorie-based diet reduced weight, BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and lipid profiles compared to resveratrol with placebo (Asghari et al. Citation2018).

Effect of nutrients on inhibition of SIRT1 expression

An excessive supply of energy leads to inhibition of the expression and activity of sirtuins. A high-fat diet (HFD) has been shown to reduce hepatic function (Valdecantos et al. Citation2012, Citation2017), and skeletal muscle (Haohao et al. Citation2015) expression of SIRT1 and SIRT3. This may be related to studies in which short or long-term HFDs and high ethanol consumption synergistically induce acute liver injury in mice (Chang et al. Citation2015).

The long-term use of a high-carbohydrate diet reduces SIRT1 expression more than an HFD with the same energy value. A high intake of carbohydrates in the diet, without excessive energy, leads to fatty liver and inhibition of NAMPT activity. Decreased SIRT1 levels under a high-carbohydrate diet are associated with increased miR-34 expression, which directly inhibits NAMPT in obesity (Li et al. Citation2015).

High levels of simple sugars in the body inhibit sirtuin activity. In vitro studies on tubular endothelial cells have shown that glucose inhibited SIRT1 expression (Zhou et al. Citation2015). In in vivo studies, a decrease in all SIRT1-SIRT7 sirtuins was observed in the hearts of mice with type 1 diabetes. Animals with type 2 diabetes have lower SIRT1 and SIRT2 levels and increased SIRT3 levels in the heart muscle (Bagul, Dinda, and Banerjee Citation2015).

Excess fructose may also contribute to a disturbance of sirtuin expression. The muscles of mice fed a fructose-rich diet exhibited increased levels of advanced glycation products (AGE), which inhibited the activation of SREBP-1c, thereby increasing the intensity of hepatic lipogenesis. The decrease in SIRT1 activity induced by AGE was also associated with a change in muscle fiber composition and a decrease in muscle strength. These studies indicate the possible negative effects of excessive dietary fructose on the risk of malnutrition (Mastrocola et al. Citation2016).

Effect of nutrients on the induction of SIRT1 expression

Adequate dietary intake of branched-chain amino acids is important for regulating sirtuin activity. Higher SIRT1 expression in the heart and diaphragm was observed in mice fed 1.5 mg branched-chain amino acids/kg/day compared to animals without supplementation. Additionally, physical activity amplifies this effect. Leucine increased the expression of SIRT1 in the liver, brown fat, and skeletal muscle of mice fed high-fat and low-fat diets (Li et al. Citation2012).

Studies have shown that certain substances can induce SIRT1 activity. Bogacka et al. showed that in non-diabetics, SIRT1 levels in adipose tissue were increased when caffeine, ephedrine, and the oral antidiabetic drug pioglitazone were administered concomitantly (Bogacka et al. Citation2007).

The intake of bioactive lipids in the diet appears to have a positive effect. Studies have shown that polyunsaturated fatty acids stimulate SIRT1 by kinase A-dependent activation of the SIRT1-PGC1α complex, thereby increasing the oxidation rate of fatty acids and preventing aging-related lipid dysregulation (Das Citation2021).

Other studies have shown that components of dairy products can act as SIRT1 activators. The consumption of dairy products leads to systemic changes that can promote the biogenesis of mitochondria in important target tissues, such as muscle and fatty tissue, both by direct activation of SIRT1 and by SIRT1-independent pathways (Bruckbauer and Zemel Citation2011). Leucine administration stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and fat metabolism in both adipocytes and muscle cells. These effects were partly mediated by SIRT1 and were significantly attenuated by SIRT1 (Sun and Zemel Citation2009).

Materials and methods

Search strategy

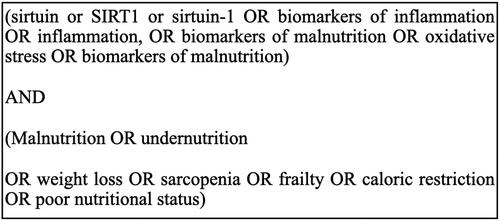

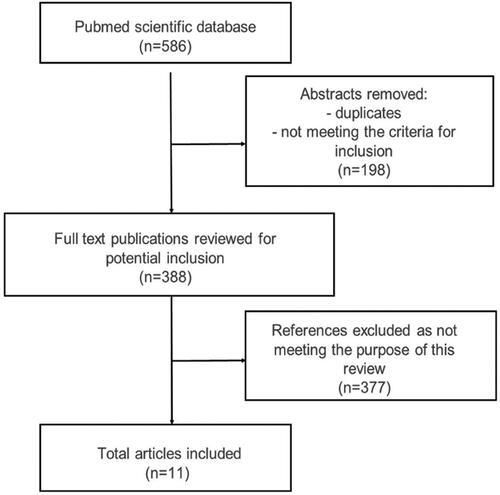

PubMed databases were used to identify studies with the combined search terms such as sirt 1 AND inflammation, sirt 1 AND malnutrition, sirt 1 AND undernutrition, and with single search terms such as malnutrition, undernutrition, elderly, sirtuin 1, inflammation, oxidative stress, sarcopenia, frailty, weakness syndrome, biomarkers of inflammation, biomarkers of undernutrition, biomarkers of malnutrition, caloric restriction, aging, and nutritional status. In order to increase the accuracy of the literature search on the subject of the work, the year of publication was not definitively limited. The inclusion criteria were publications in English, such as randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. Publications involving animal experiments were also included. To better identify relevant studies and journals, review and original articles were searched manually using the ISNN journal databases. The search terms are shown in . Duplicates and publications based only on abstracts were excluded ().

Effects of malnutrition on SIRT1 activity

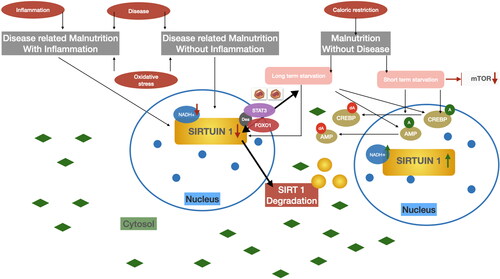

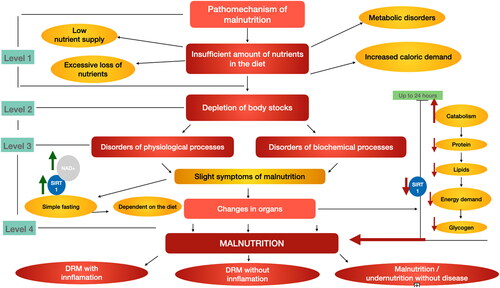

Reduction of body reserves after level 1—insufficient nutrient intake, including metabolic disorders, increased demand, undernourishment, or excessive weight loss leads to depletion of body reserves and mild undernourishment (step 2). Minor signs of malnutrition lead to simple, uncomplicated dietary hunger (Level 3). During prolonged fasting, hunger, or extreme diets, NAD + levels increase as both NAD + biosynthesis and oxidation to NAD + increase (Cantó, Menzies, and Auwerx Citation2015). This leads to an increase in SIRT1 as a result of NAD + expression (step 3). The last stage of the pathomechanism of malnutrition is the occurrence of organ lesions and adverse changes in the body, such as increased catabolism and reduced protein, fat, and energy requirements within 24 h, which contribute to a decrease in SIRT1 levels in the body. According to previous studies, SIRT1 decreases in the fasting state of the pancreas, and during this time the mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 increases, which may explain the lower insulin secretion due to calorie reduction (Bordone et al. Citation2006). A decline in SIRT1 is caused by long-term starvation, which leads to a physiological reduction in insulin and fasting glucose levels. A decrease in SITR1 in the pancreas may also be associated with malnutrition, as described in the three types of inflammatory disease-related malnutrition (DRM), non-inflammatory DRM, and disease-free malnutrition (Cederholm et al. Citation2017). However, the exact role of fasting in the activity of SIRT1 is not yet fully understood and appears to vary from tissue to tissue (Chen et al. Citation2008).

The pathomechanisms of malnutrition and possible SIRT1 relationship are shown in (in-house development based on the ESPEN guidelines).

Figure 3. The pathomechanism of malnutrition and the effects of malnutrition on blood SIRT1 levels. Inadequate supply of food constituents contributes to the depletion of body reserves, which in turn leads to disruptions of physiological processes and disruptions of biochemical processes. These changes lead to minor symptoms of malnutrition, which lead to starvation of the uncomplicated simple depending on the diet. The uncomplicated simple hunger increases the expression of NAD+, which in turn increases the expression of SIRT1. However, the persistent depletion of the body’s reserves leads to more severe organ damage, which manifests itself in catabolism, protein loss in the body, fat loss, energy demand and glycogen loss in the body within 24 h. This leads to a decrease in the level of SIRT1 in the body. Unfavorable organ changes contribute to malnutrition, which can affect DRM + I, DRM − I, Malnutrition without disease, depending on the severity (DRM disease related malnutrition—ESPEN). Authors own study based on Bordone et al. (Citation2006); Cantó, Menzies, and Auwerx (Citation2015); Cederholm et al. (Citation2017); Chen et al. (Citation2008); McClain, Kirpich, and Smart (Citation2017); Nemoto, Fergusson, and Finkel (Citation2004).

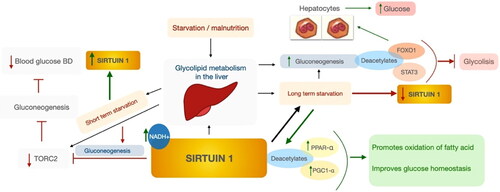

SIRT1 is involved in glycolipid metabolism in the liver. In short-term hunger, SIRT1 may inhibit target of rapamycin C2, which in turn inhibits gluconeogenesis and lowers blood sugar levels. Short-term fasting increases the expression and concentration of SIRT1 (Nemoto, Fergusson, and Finkel Citation2004). During prolonged starvation, SIRT1 deacetylates and activates the substrates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) and PPAR-γ co-activator-1α (PGC-1α), which contribute to the oxidation of fatty acids and improvement of glucose homeostasis. Second, SIRT1 deacetylates forkhead box 01 (FOX01) and signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) by promoting gluconeogenesis and inhibiting glycolysis, respectively. SIRT1 deacetylates FOX01 in hepatocytes, thereby releasing glucose. Long-term starvation contributes to a reduction in SIRT1 levels. The dietary status in liver disease may depend on factors such as overeating, malnutrition, or altered metabolism (McClain, Kirpich, and Smart Citation2017). Patients with complications such as liver disease, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy have been shown to have a higher incidence of sarcopenia and malnutrition (Knudsen et al. Citation2016). The role of SIRT1 in hepatic glycolipid metabolism appears to be promising, and activation of SIRT1 may be beneficial not only in metabolic disorders and aging retardation, but also in malnutrition (Bonda et al. Citation2011; Mouchiroud et al. Citation2013). The fasting hepatic glycolipid metabolism by sirtuin 1 is shown in .

Figure 4. Effect of SIRT1 in hepatic glycolipid metabolism under starvation. Authors’ own study based on Hallows, Yu, and Denu (Citation2012); Horton, Goldstein, and Brown (Citation2002); Purushotham et al. (Citation2009).

The human defense system consists of different enzymatic and non-enzymatic components (Harman Citation1956). These enzymes include glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), glutathione reductase (GSH-Rd), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase. Non-enzymatic substances include endogenous antioxidants, such as reduced glutathione (GSH), ubiquinone (coenzyme Q10), uric acid, alpha lipoic acid, metallothionein, albumin, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin, as well as exogenous antioxidants, such as vitamin E (especially a-tocopherol), carotenoids (β-carotene, α-carotene, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin, astaxanthin, and canthaxanthin), vitamin C, flavonoids, mannitol, aminoguanidine and pyridoxine (Ferreira et al. Citation2011; Vasconcelos et al. Citation2007).

Elderly people with poor nutrition and malnutrition have low body weight, which in turn predisposes them to a variety of complications, such as reduced immunity (Lesourd and Mazari Citation1997), functional impairment (Moreira Citation2011), frailty (Wu et al. Citation2009) (with involuntary weight loss, fatigue, weakness, reduced walking speed, and physical activity) (Macedo, Gazzola, and Najas Citation2008), and an increase in morbidity and mortality (Vetta et al. Citation1999).

Chronic malnutrition has been shown to increase oxidative stress as albumin concentration in the body decreases, which in turn can act as an antioxidant (Fechner et al. Citation2001). Malnutrition followed by hypoalbuminemia increases oxidative stress in the plasma and liver (Fechner et al. Citation2001; Manary, Leeuwenburgh, and Heinecke Citation2000; van Zutphen et al. Citation2016).

Excessive oxidative stress impairs mitochondrial function due to mitochondrial DNA failure (Nissanka and Moraes Citation2018). Malnutrition may increase oxidative stress in skeletal muscles, which are rich in mitochondria. It has been shown that cellular oxidation can occur during the aging process itself and that these factors carry the risk of chronic diseases in older people (Halliwell and Gutteridge Citation2015). Oxidative stress causes cell aging, increasing the role of SIRT1 in protecting cells from aging by regulating FOX0, p53, and p21, as well as molecules involved in DNA damage and repair (Furukawa et al. Citation2007; Yao and Rahman Citation2012).

There is an association between plasma levels of oxidative stress markers (8-iso-PGF2α and 8-oxo-dGuo), nutritional status indicators (BMI), and cardiovascular risk (waist-hip ratio) (Tôrres et al. Citation2013).

Studies show that SIRT1 regulates oxidative stress and cellular toxicity (Chua et al. Citation2005; Kitamura et al. Citation2005). Causes may include SIRT1-mediated induction of manganese peroxide dismutase (MnSOD) by deacetylation and activation of the transcription factor FOX03. Research shows that the induction enhancer is resveratrol, which increases resistance to oxidative stress in myoblasts (Tanno et al. Citation2010). In other studies, FOX03 activation has also been shown to protect against oxidative stress caused by MnSOD (Kops et al. Citation2002; Li et al. Citation2006). SIRT1 expression and FOX03 deacetylation, which results in increased catalase expression, also protects the heart from oxidative stress in mouse models (Alcendor et al. Citation2007). Liver SIRT1 deficiency increases ROS production, impairing TOR/Akt signaling in other insulin-sensitive organs, resulting in insulin resistance (Kume et al. Citation2006).

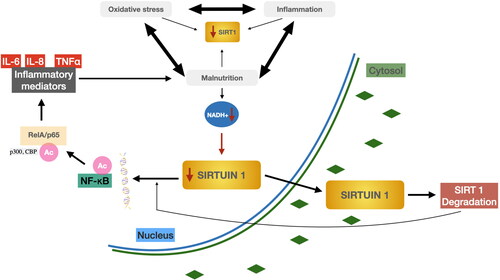

SIRT1 inhibits IKB kinase, which in turn inhibits IKB degradation and, thus, the inflammatory response. Activation of SIRT1 leads to deacetylation and activation of the transcription factor FOX03, resulting in the production of catalase and MnSOD. Both compounds reduce oxidative stress. The mechanism for regulating oxidative stress and inflammation by SIRT1 is shown in .

These studies suggest that oxidative stress, inflammation, and malnutrition are closely associated (Hirabayashi et al. Citation2021). Inflammation associated with disease is often observed in undernourished individuals. Inflammation affects the body’s need for nutrients as well as food intake, including appetite. It contributes to changes in metabolism, including increased resting energy consumption and increased muscle catabolism (Jensen Citation2015). Furthermore, malnutrition impairs the metabolic capacity of both fast and free muscles owing to AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-independent inhibition of SIRT1 through increased oxidative stress (Hirabayashi et al. Citation2021).

Long-term moderate calorie restriction without undernutrition induces significant and sustained inhibition of inflammation without worsening key indicators of cellular immunity in vivo (Meydani et al. Citation2016).

Oxidative stress contributes to inflammation and malnutrition. Malnutrition can manifest as inflammation and increased oxidative stress; together, all these factors may lead to a decrease in SIRT1 expression. Decreased SIRT1 expression is associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, and malnutrition and is associated with the acetylation of NF-κB, an important redox-sensitive transcription factor responsible for the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes (Toledano and Leonard Citation1991). Inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), IL-6, and TNF-α are involved in the activation of immune cells and an inflammatory reaction. One of the main sources of these pro-inflammatory mediators are macrophages at the site of injury. In these cells, the transcription of these cytokines is regulated by NF-κB which undergoes various post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation and acetylation (Chen et al. Citation2005). Acetylation, together with phosphorylation, plays an important role in regulating the nuclear activity of NF-κB. Both p300 and CBP transferases have been reported to acetylate the RelA/p65 subunit NF-αB at Lys218, Lys221, and Lys310 (Chen, Mu, and Greene Citation2002). Acetylation of separate lysine residues in RelA/p65 modulates various functions of NF-κB, including transcription activation, DNA binding, and folding with its Iα inhibitor (Lanzillotta et al. Citation2010). After reduced NADH+, SIRT1 is degraded with simultaneous acetylation of NFKB and ReIA/p65 and the release of inflammatory mediators, which in turn may lead to malnutrition associated with inflammation and oxidative stress. The relationship between the factors that may stimulate reduced SIRT1 expression is shown in .

Figure 6. Possible factors that stimulate a decrease in SIRT1 expression in the body Degradation of SIRT1 by NAD + waste with simultaneous acetylation of NF-KB and ReIA/p65 and release of inflammatory mediators. Authors’ own study based on literature Abdelmohsen et al. (Citation2007).

SIRT1 in frailty

Kumar et al. revealed that blood sirtuin levels are associated with geriatric fragility syndrome (Kumar et al. Citation2014). SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT3 were significantly lower in subjects with frailty syndrome than in those without, persisting after correction for independent factors such as number of concomitant diseases, sex, age, cognitive impairment, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. In another study, circulating SIRT1 was higher in weak older adults, including those with weight loss (Ma et al. Citation2019).

While the evaluation of inflammatory biomarkers is useful in assessing the risk of undernutrition in relation to severe diseases in which they play a role, the association of SIRT1 with frailty is quite promising, as it may indicate significant sensitivity and specificity, without an ongoing inflammatory process in malnutrition.

SIRT1 as potential malnutrition biomarker

Many studies point to an association between DRM and inflammation, oxidative stress, and organ dysfunction, including endothelial dysfunction in patients with inflammatory DRM (Bañuls et al. Citation2019; Solmi et al. Citation2015; Victor et al. Citation2009). The role of oxidative stress regulation of SIRT1 in the potential inflammatory mechanism and aging has been described in the literature (Hwang et al. Citation2013), but the role of SIRT1 as a biomarker for malnutrition has not yet been described.

While calorie restriction without malnutrition promotes longevity and delays aging in the SIRT1 regulatory mechanism (Fontana, Partridge, and Longo Citation2010), the effects of prolonged calorie restriction and hunger on the severity of undernourishment are not well described.

In one study, SIRT1 levels were measured in three age groups (children, adults, and the elderly) to understand how SIRT1 levels change with age. The relationship between the polymorphisms of the single nucleotide SIRT1 (rs7 895 833 A > G in the promoter region, rs7 069 102 C > G in intron 4, and rs2 273 773 C > T in Exon 5—silent mutation) and the expression levels of SIRT1, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and paraoxonase-1 were investigated. Paraoxonase 1 (PON-1), cholesterol levels, total antioxidant status (TAS), total oxidation status, and oxidation stress index (OSI) increased with increasing age in a Turkish population. A significant increase in SIRT1 levels was observed in elderly patients and a significant positive correlation between SIRT1 levels and age was observed in the overall study population. The oldest individuals with the AG genotype for rs7 895 833 had the highest SIRT1 value, suggesting a relationship between rs7 895 833 SNP and longevity. Elderly patients had a higher OSI and lower PON-1 levels than adults and children, which may lead to high SIRT1 levels as a compensatory mechanism for oxidative stress in the elderly. In addition, a decrease in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels has been observed in elderly patients and a positive correlation between high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and SIRT1 levels has been observed in elderly patients (Kilic et al. Citation2015). The aging process itself contributes to the oxidative damage of DNA, which in turn leads to an increase in ROS, a higher rate of oxidative stress, and is an important factor in the occurrence of age-related diseases (Bohr Citation2002). Oxidative stress induces a reduction in NAD + by activation of PPAR, which in turn results in reduced expression of SIRT1. In vivo studies in rats have shown that this mechanism plays an important role in aging. In other studies, TAS was higher in elderly patients than in adults, but did not differ significantly from TAS levels in children. This may be related to the high SIRT1 levels in older people and the role of SIRT1 in the induction of antioxidants (Olmos et al. Citation2013).

Many studies have shown that the oxidative stress caused by TAS and total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol is associated with SIRT1 levels in the elderly. The correlation between cholesterol and SIRT1 levels may be explained by changes in hepatic metabolism associated not only with age, but also with malnutrition associated with metabolic disorders (Morena et al. Citation2000). Older people have lower HDL cholesterol and higher LDL cholesterol levels than younger people. Some studies have shown that higher LDL-C levels in elderly patients are associated with increased mortality mainly due to oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions (Benn, Tybjærg-Hansen, and Nordestgaard Citation2019; Yeboah Citation2018).

A Chinese study found an association between the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio and overall mortality in elderly patients with hypertension. Both low and high LDL-C/HDL-C ratios resulted in higher overall mortality, and patients with an LDL-C/HDL-C 1.67–2.10 had a significantly higher chance of survival (Yu et al. Citation2020).

El Assar et al. have shown that the improvement in nutritional status, as measured by MNA in older people, regardless of frailty syndrome or adherence to the Mediterranean diet, is positively associated with SIRT1 gene expression. The increased risk of malnutrition (based on MNA scores) was significantly associated with lower SIRT1 expression, confirming that older people with good nutrition have higher SIRT1 expression levels. These findings suggest that Sirtuin 1 is a potential biomarker for health interventions in the elderly (El Assar et al. Citation2018).

This work underlines the importance of sirtuins in the context of malnutrition in older people. Malnutrition, with or without inflammation or DRM caused by calorie restriction, may be associated with changes in SIRT1 expression in the cell nucleus. Calorie reduction has been shown to have a positive effect on longevity and aging and calorie restriction alone should not be equated with malnutrition (Michan Citation2014).

However, it should be noted that sirtuin activity is influenced by nutrient availability. SIRT1 levels increase during fasting or calorie reduction with negative energy balance (Rodgers and Puigserver Citation2007). Nutrient values (e.g., glucose, lipids, and amino acids) were measured with AMPK, SIRT1, or mTOR energy sensors (Escobar et al. Citation2019; Finkel Citation2015; Nemoto, Fergusson, and Finkel Citation2004). Malnutrition without disease may be associated with a short-term calorie reduction, which in turn activates AMPK or SIRT1 but inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which is reduced in nutrient deficiency. Long-term calorie restriction and malnutrition with or without inflammation, decreases NADH+, which reduces the expression of SIRT1. Simultaneous deacetylation of STAT3 and FOX01 in hepatocytes, results in the transfer of SIRT1 from the nucleus to the cytosol and degradation of SIRT1. shows SIRT1 as a potential biomarker of nutritional status in the mechanism of decreasing and increasing activity in the cell nucleus.

Conclusions

The key to successful treatment of the elderly is early detection of undernutrition and its risk factors, and the earliest possible application of therapy. Animal studies point to potential molecular mechanisms regulating sirtuin 1 expression. In this review, we proposed the pathomechanism and pathway of sirtuin 1 activation and attempted to explain how malnutrition affects sirtuin 1 expression. Studies suggest that short-term fasting can increase SIRT1 expression, while long-term fasting can have the opposite effect. Some studies suggest a potential link between sirtuin 1 and nutritional status in older adults. However, these data, with the current state of knowledge are limited to a small number of human and animal studies, and therefore require further research to confirm the potential of sirtuin 1 as a biomarker of age-related undernutrition. When evaluating the usefulness of sirtuin 1 as a biomarker of undernutrition in humans, it is important to consider other medical conditions that may themselves cause changes in sirtuin 1 concentration and, on the other hand, chronic diseases may lead to malnutrition. Taking all these factors into account, further studies are desirable to confirm the role of sirtuin 1 in malnutrition and to investigate the predictive value, specificity and sensitivity of sirtuin 1 as a biomarker.

Author contributions

Writing–original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, K.K. and A.W.

Availability of data and material

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

| Abbreviations | ||

| AGE | = | Advanced glycation products |

| AMPK | = | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| BMI | = | Body Mass Index |

| ChREBP | = | Carbohydrate response sequence |

| CREB | = | AMP-activated factor |

| DRM | = | Disease-related malnutrition |

| FFA | = | Free fatty acids |

| FOX0 | = | Forkhead box 0 |

| FOX01 | = | Forkhead box 01 |

| FOX03 | = | Forkhead box 03 |

| GSH | = | Reduced glutathione |

| GSH-Px | = | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH-Rd | = | Glutathione reductase |

| HDACs | = | Histone deacetylases |

| HDL | = | High-density lipoprotein |

| HFD | = | High-fat diet |

| IL1 | = | Interleukin-1 |

| IL6 | = | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | = | Interleukin-8 |

| LDL | = | Low-density lipoprotein |

| mTOR | = | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MNA | = | Mini-Nutritional Assessment |

| MnSOD | = | Manganese peroxide dismutase |

| MUST | = | Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool |

| NAD | = | Histone-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NAMPT | = | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NF-αB | = | Nuclear factor αB |

| NRS-2002 | = | Nutrition Risk Screening |

| OSI | = | Oxidation stress index |

| PGC-1α | = | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| PON-1 | = | Paraoxonase 1 |

| PPARα | = | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| ROS | = | Reactive oxygen species |

| SIR2 | = | Silent information regulator 2 |

| SIRT1 | = | Sirtuin 1 |

| SOD | = | Superoxide dismutase |

| SGA | = | Subjective Global Assessment Short Form |

| STAT3 | = | Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 |

| TAS | = | Total antioxidant status |

| TNFα | = | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdelmohsen, K., R. Pullmann, A. Lal, H. H. Kim, S. Galban, X. Yang, J. D. Blethrow, M. Walker, J. Shubert, D. A. Gillespie, et al. 2007. Phosphorylation of HuR by Chk2 regulates SIRT1 expression. Molecular Cell 25 (4):543–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.011.

- Alcaín, F. J., R. K. Minor, J. M. Villalba, and R. de Cabo. 2010. Small molecule modulators of sirtuin activity. In The future of aging: pathways to human life extension, ed. G. M. Fahy, M. D. West, L. S. Coles, and S. B. Harris, 331–56. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Alcendor, R. R., S. Gao, P. Zhai, D. Zablocki, E. Holle, X. Yu, B. Tian, T. Wagner, S. F. Vatner, and J. Sadoshima. 2007. Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circulation Research 100 (10):1512–21. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000267723.65696.4a.

- Allard, J. P., H. Keller, L. Gramlich, K. N. Jeejeebhoy, M. Laporte, and D. R. Duerksen. 2020. GLIM criteria has fair sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing malnutrition when using SGA as comparator. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 39 (9):2771–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.12.004.

- Amirchaghmaghi, M., Z. Delavarian, M. Iranshahi, M. T. Shakeri, P. Mosannen Mozafari, A. H. Mohammadpour, F. Farazi, and M. Iranshahy. 2015. A randomized placebo-controlled double blind clinical trial of Quercetin for treatment of oral lichen planus. Journal of Dental Research, Dental Clinics, Dental Prospects 9 (1):23–8. doi: 10.15171/joddd.2015.005.

- An, F., S. Wang, Q. Tian, and D. Zhu. 2015. Effects of orientin and vitexin from Trollius chinensis on the growth and apoptosis of esophageal cancer EC-109 cells. Oncology Letters 10 (4):2627–33. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3618.

- Asghari, S., M. Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. H. Somi, S. M. Ghavami, and M. Rafraf. 2018. Comparison of calorie-restricted diet and resveratrol supplementation on anthropometric indices, metabolic parameters, and serum sirtuin-1 levels in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 37 (3):223–33. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2017.1392264.

- Asher, G., and U. Schibler. 2011. Crosstalk between components of circadian and metabolic cycles in mammals. Cell Metabolism 13 (2):125–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.006.

- Ashikawa, K., S. Majumdar, S. Banerjee, A. C. Bharti, S. Shishodia, and B. B. Aggarwal. 2002. Piceatannol inhibits TNF-induced NF-kappaB activation and NF-kappaB-mediated gene expression through suppression of IkappaBalpha kinase and p65 phosphorylation. Journal of Immunology 169 (11):6490–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6490.

- Bae, J. S. 2015. Inhibitory effect of orientin on secretory group IIA phospholipase A2. Inflammation 38 (4):1631–8. doi: 10.1007/s10753-015-0139-8.

- Bagul, P. K., A. K. Dinda, and S. K. Banerjee. 2015. Effect of resveratrol on sirtuins expression and cardiac complications in diabetes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 468 (1–2):221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.126.

- Bartosch, C., S. Monteiro-Reis, D. Almeida-Rios, R. Vieira, A. Castro, M. Moutinho, M. Rodrigues, I. Graça, J. M. Lopes, and C. Jerónimo. 2016. Assessing sirtuin expression in endometrial carcinoma and non-neoplastic endometrium. Oncotarget 7 (2):1144–54. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6691.

- Bañuls, C., A. M. de Marañon, S. Veses, I. Castro-Vega, S. López-Domènech, C. Salom-Vendrell, S. Orden, Á. Álvarez, M. Rocha, V. M. Víctor, et al. 2019. Malnutrition impairs mitochondrial function and leukocyte activation. Nutrition Journal 18 (1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12937-019-0514-7.

- Benn, M., A. Tybjærg-Hansen, and B. G. Nordestgaard. 2019. Low LDL Cholesterol by PCSK9 Variation Reduces Cardiovascular Mortality. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 73 (24):3102–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.517.

- Bhardwaj, M., S. Paul, R. Jakhar, and S. C. Kang. 2015. Potential role of vitexin in alleviating heat stress-induced cytotoxicity: Regulatory effect of Hsp90 on ER stress-mediated autophagy. Life Sciences 142:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.10.012.

- Ble, A., A. Cherubini, S. Volpato, B. Bartali, J. D. Walston, B. G. Windham, S. Bandinelli, F. Lauretani, J. M. Guralnik, and L. Ferrucci. 2006. Lower plasma vitamin E levels are associated with the frailty syndrome: The InCHIANTI study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 61 (3):278–83. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.278.

- Bleeker, J. C., and R. H. Houtkooper. 2016. Sirtuin activation as a therapeutic approach against inborn errors of metabolism. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 39 (4):565–72. doi: 10.1007/s10545-016-9939-8.

- Bogacka, I., T. W. Gettys, L. de Jonge, T. Nguyen, J. M. Smith, H. Xie, F. Greenway, and S. R. Smith. 2007. The effect of beta-adrenergic and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma stimulation on target genes related to lipid metabolism in human subcutaneous adipose tissue. Diabetes Care 30 (5):1179–86. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1962.

- Bohr, V. A. 2002. Repair of oxidative DNA damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, and some changes with aging in mammalian cells. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 32 (9):804–12. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00787-6.

- Bonda, D. J., H. G. Lee, A. Camins, M. Pallàs, G. Casadesus, M. A. Smith, and X. Zhu. 2011. The sirtuin pathway in ageing and Alzheimer disease: Mechanistic and therapeutic considerations. The Lancet. Neurology 10 (3):275–9. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70013-8.

- Bonkowski, M. S., and D. A. Sinclair. 2016. Slowing ageing by design: The rise of NAD+ and sirtuin-activating compounds. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 17 (11):679–90. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.93.

- Boominathan, S., G. Sarangan, S. Srikakulapu, S. Rajesh, C. Duraipandian, P. Srikanth, and L. Jo. 2014. Antiviral activity of bioassay guided fractionation of Plumbago zeylanica roots against herpes simplex virus type 2. World Journal of Pharmacy Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3 (12):1003–17.

- Bordone, L., M. C. Motta, F. Picard, A. Robinson, U. S. Jhala, J. Apfeld, T. McDonagh, M. Lemieux, M. McBurney, A. Szilvasi, et al. 2006. Sirt1 regulates insulin secretion by repressing UCP2 in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS Biology 4 (2):e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040031.

- Borghi, S. M., T. T. Carvalho, L. Staurengo-Ferrari, M. S. Hohmann, P. Pinge-Filho, R. Casagrande, and W. A. Verri. Jr 2013. Vitexin inhibits inflammatory pain in mice by targeting TRPV1, oxidative stress, and cytokines. Journal of Natural Products 76 (6):1141–9. doi: 10.1021/np400222v.

- Bourke, C. D., J. A. Berkley, and A. J. Prendergast. 2016. Immune dysfunction as a cause and consequence of malnutrition. Trends in Immunology 37 (6):386–98. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.04.003.

- Brocca, L., J. Cannavino, L. Coletto, G. Biolo, M. Sandri, R. Bottinelli, and M. A. Pellegrino. 2012. The time course of the adaptations of human muscle proteome to bed rest and the underlying mechanisms. The Journal of Physiology 590 (20):5211–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.240267.

- Bruckbauer, A., and M. B. Zemel. 2011. Effects of dairy consumption on SIRT1 and mitochondrial biogenesis in adipocytes and muscle cells. Nutrition & Metabolism 8:91. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-91.

- Budui, S. L., A. P. Rossi, and M. Zamboni. 2015. The pathogenetic bases of sarcopenia. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism 12 (1):22–6. doi: 10.11138/ccmbm/2015.12.1.022.

- Burns, A., C. Brayne, and M. Folstein. 1998. Key papers in geriatric psychiatry: mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. M. Folstein, S. Folstein and P. McHugh. 1975. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12 189–198. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13 (5):285–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199805)13:5 < 285::AID-GPS753 > 3.0.CO;2-V.

- Bódis, J., E. Sulyok, T. Kőszegi, K. Gödöny, V. Prémusz, and Á. Várnagy. 2019. Serum and follicular fluid levels of sirtuin 1, sirtuin 6, and resveratrol in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: An observational, clinical study. The Journal of International Medical Research 47 (2):772–82. doi: 10.1177/0300060518811228.

- Calgarotto, A. K., V. Maso, G. C. F. Junior, A. E. Nowill, P. L. Filho, J. Vassallo, and S. T. O. Saad. 2018. Antitumor activities of Quercetin and Green Tea in xenografts of human leukemia HL60 cells. Scientific Reports 8 (1):3459. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21516-5.

- Cantó, C., K. J. Menzies, and J. Auwerx. 2015. NAD+ metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis: A balancing act between mitochondria and the nucleus. Cell Metabolism 22 (1):31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.023.

- Cea, M., D. Soncini, F. Fruscione, L. Raffaghello, A. Garuti, L. Emionite, E. Moran, M. Magnone, G. Zoppoli, D. Reverberi, et al. 2011. Synergistic interactions between HDAC and sirtuin inhibitors in human leukemia cells. PloS One 6 (7):e22739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022739.

- Cederholm, T., R. Barazzoni, P. Austin, P. Ballmer, G. Biolo, S. C. Bischoff, C. Compher, I. Correia, T. Higashiguchi, M. Holst, et al. 2017. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 36 (1):49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.09.004.

- Cederholm, T., I. Bosaeus, R. Barazzoni, J. Bauer, A. Van Gossum, S. Klek, M. Muscaritoli, I. Nyulasi, J. Ockenga, S. M. Schneider, et al. 2015. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition – An ESPEN Consensus Statement. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 34 (3):335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.03.001.

- Cederholm, T., G. L. Jensen, M. I. T. D. Correia, M. C. Gonzalez, R. Fukushima, T. Higashiguchi, G. Baptista, R. Barazzoni, R. Blaauw, A. Coats, GLIM Working Group, et al. 2019. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition – A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 38 (1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.002.

- Cereda, E., C. Pedrolli, C. Klersy, C. Bonardi, L. Quarleri, S. Cappello, A. Turri, M. Rondanelli, and R. Caccialanza. 2016. Nutritional status in older persons according to healthcare setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence data using MNA®. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 35 (6):1282–90. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.03.008.

- Chahinian, A. P., J. P. Mandeli, H. Gluck, H. Naim, A. S. Teirstein, and J. F. Holland. 1998. Effectiveness of cisplatin, paclitaxel, and suramin against human malignant mesothelioma xenografts in athymic nude mice. Journal of Surgical Oncology 67 (2):104–11. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199802)67:2 < 104::aid-jso6 > 3.0.co;2-e.

- Chalkiadaki, A., and L. Guarente. 2015. The multifaceted functions of sirtuins in cancer. Nature Reviews. Cancer 15 (10):608–24. doi: 10.1038/nrc3985.

- Chandramowlishwaran, P., A. Vijay, D. Abraham, G. Li, S. M. Mwangi, and S. Srinivasan. 2020. Role of sirtuins in modulating neurodegeneration of the enteric nervous system and central nervous system. Frontiers in Neuroscience 14:614331. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.614331.

- Chang, B., M.-J. Xu, Z. Zhou, Y. Cai, M. Li, W. Wang, D. Feng, A. Bertola, H. Wang, G. Kunos, et al. 2015. Short‐or long‐term high‐fat diet feeding plus acute ethanol binge synergistically induce acute liver injury in mice: An important role for CXCL1. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 62 (4):1070–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.27921.

- Chen, D., J. Bruno, E. Easlon, S. J. Lin, H. L. Cheng, F. W. Alt, and L. Guarente. 2008. Tissue-specific regulation of SIRT1 by calorie restriction. Genes & Development 22 (13):1753–57. doi: 10.1101/gad.1650608.

- Chen, L. F., Y. Mu, and W. C. Greene. 2002. Acetylation of RelA at discrete sites regulates distinct nuclear functions of NF-kappaB. The EMBO Journal 21 (23):6539–48. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf660.

- Chen, L. F., S. A. Williams, Y. Mu, H. Nakano, J. M. Duerr, L. Buckbinder, and W. C. Greene. 2005. NF-kappaB RelA phosphorylation regulates RelA acetylation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 25 (18):7966–75. doi: 10.1128/mcb.25.18.7966-7975.2005.

- Cheng, H.-L., R. Mostoslavsky, S. Saito, J. P. Manis, Y. Gu, P. Patel, R. Bronson, E. Appella, F. W. Alt, and K. F. Chua. 2003. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 (19):10794–99. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934713100.

- Cholewa, J. M., D. Dardevet, F. Lima-Soares, K. de Araújo Pessôa, P. H. Oliveira, J. R. Dos Santos Pinho, H. Nicastro, Z. Xia, C. E. T. Cabido, and N. E. Zanchi. 2017. Dietary proteins and amino acids in the control of the muscle mass during immobilization and aging: Role of the MPS response. Amino Acids 49 (5):811–20. doi: 10.1007/s00726-017-2390-9.

- Choo, C. Y., N. Y. Sulong, F. Man, and T. W. Wong. 2012. Vitexin and isovitexin from the Leaves of Ficus deltoidea with in-vivo α-glucosidase inhibition. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 142 (3):776–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.062.

- Chua, K. F., R. Mostoslavsky, D. B. Lombard, W. W. Pang, S. Saito, S. Franco, D. Kaushal, H.-L. Cheng, M. R. Fischer, N. Stokes, et al. 2005. Mammalian SIRT1 limits replicative life span in response to chronic genotoxic stress. Cell Metabolism 2 (1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.007.

- Chung, S., H. Yao, S. Caito, J. W. Hwang, G. Arunachalam, and I. Rahman. 2010. Regulation of SIRT1 in cellular functions: Role of polyphenols. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 501 (1):79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.003.

- Clegg, A., J. Young, S. Iliffe, M. O. Rikkert, and K. Rockwood. 2013. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England) 381 (9868):752–62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62167-9.

- Crispi, F., J. Miranda, and E. Gratacós. 2018. Long-term cardiovascular consequences of fetal growth restriction: Biology, clinical implications, and opportunities for prevention of adult disease. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 218 (2s):S869–S879. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.012.

- Crossland, H., D. Constantin-Teodosiu, S. M. Gardiner, D. Constantin, and P. L. Greenhaff. 2008. A potential role for Akt/FOXO signalling in both protein loss and the impairment of muscle carbohydrate oxidation during sepsis in rodent skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology 586 (22):5589–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160150.

- Crossland, H., D. Constantin-Teodosiu, P. L. Greenhaff, and S. M. Gardiner. 2010. Low-dose dexamethasone prevents endotoxaemia-induced muscle protein loss and impairment of carbohydrate oxidation in rat skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology 588 (Pt 8):1333–47. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183699.

- Currais, A., M. Prior, R. Dargusch, A. Armando, J. Ehren, D. Schubert, O. Quehenberger, and P. Maher. 2014. Modulation of p25 and inflammatory pathways by fisetin maintains cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. Aging Cell 13 (2):379–90. doi: 10.1111/acel.12185.

- Das, U. N. 2021. Cell membrane theory of senescence and the role of bioactive lipids in aging, and aging associated diseases and their therapeutic implications. Biomolecules 11 (2):241. doi: 10.3390/biom11020241.

- Davis, J. M., E. A. Murphy, M. D. Carmichael, and B. Davis. 2009. Quercetin increases brain and muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and exercise tolerance. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 296 (4):R1071–R11077. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90925.2008.

- de Picciotto, N. E., L. B. Gano, L. C. Johnson, C. R. Martens, A. L. Sindler, K. F. Mills, S.-I. Imai, and D. R. Seals. 2016. Nicotinamide mononucleotide supplementation reverses vascular dysfunction and oxidative stress with aging in mice. Aging Cell 15 (3):522–530. doi: 10.1111/acel.12461.

- Donini, L. M., E. Poggiogalle, A. Molfino, A. Rosano, A. Lenzi, F. Rossi Fanelli, and M. Muscaritoli. 2016. Mini-nutritional assessment, malnutrition universal screening tool, and nutrition risk screening tool for the nutritional evaluation of older nursing home residents. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 17 (10):959.e911–959.e918. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.06.028.

- Donmez, G., and T. F. Outeiro. 2013. SIRT1 and SIRT2: Emerging targets in neurodegeneration. EMBO Molecular Medicine 5 (3):344–52. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201302451.

- Du, J., Y. Zhou, X. Su, J. J. Yu, S. Khan, H. Jiang, J. Kim, J. Woo, J. H. Kim, B. H. Choi, et al. 2011. Sirt5 is a NAD-dependent protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science (New York, N.Y.) 334 (6057):806–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1207861.

- Duke, J., and M. J. Bogenschutz. 1994. Dr. Duke’s phytochemical and ethnobotanical databases: Washington, DC: USDA, Agricultural Research Service.

- Dykes, L., and L. W. Rooney. 2006. Sorghum and millet phenols and antioxidants. Journal of Cereal Science 44 (3):236–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2006.06.007.

- Dülger, H., M. Arik, M. R. Sekeroğlu, M. Tarakçioğlu, T. Noyan, Y. Cesur, and R. Balahoroğlu. 2002. Pro-inflammatory cytokines in Turkish children with protein-energy malnutrition. Mediators of Inflammation 11 (6):363–35. doi: 10.1080/0962935021000051566.

- El Assar, M., J. Angulo, S. Walter, J. A. Carnicero, F. J. García-García, J.-M. Sánchez-Puelles, C. Sánchez-Puelles, and L. Rodríguez-Mañas. 2018. Better nutritional status is positively associated with mRNA expression of SIRT1 in community-dwelling older adults in the Toledo Study for Healthy Aging. The Journal of Nutrition 148 (9):1408–14. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy149.

- Elliott, P. J., and M. Jirousek. 2008. Sirtuins: Novel targets for metabolic disease. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 9 (4):371–8.

- Escobar, K. A., N. H. Cole, C. M. Mermier, and T. A. VanDusseldorp. 2019. Autophagy and aging: Maintaining the proteome through exercise and caloric restriction. Aging Cell 18 (1):e12876. doi: 10.1111/acel.12876.

- Fechner, A., C. C. Böhme, S. Gromer, M. Funk, R. H. Schirmer, and K. Becker. 2001. Antioxidant Status and Nitric Oxide in the Malnutrition Syndrome Kwashiorkor. Pediatric Research 49 (2):237–43. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200102000-00018.

- Ferreira, A., C. Renatacorrea, C. Freire, P. Moreira, C. Berchieri-Ronchi, R. Reis, and C. Nogueira. 2011. Metabolic syndrome: Updated diagnostic criteria and impact of oxidative stress on metabolic syndrome pathogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (2):786

- Ferry, D. R., A. Smith, J. Malkhandi, D. W. Fyfe, P. G. deTakats, D. Anderson, J. Baker, and D. J. Kerr. 1996. Phase I clinical trial of the flavonoid quercetin: Pharmacokinetics and evidence for in vivo tyrosine kinase inhibition. Clin Cancer Res 2 (4):659–68.

- Finkel, T. 2015. The metabolic regulation of aging. Nature Medicine 21 (12):1416–23. doi: 10.1038/nm.3998.

- Finkel, T., C. X. Deng, and R. Mostoslavsky. 2009. Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature 460 (7255):587–91. doi: 10.1038/nature08197.

- Flores, G., K. Dastmalchi, A. J. Dabo, K. Whalen, P. Pedraza-Peñalosa, R. F. Foronjy, J. M. D’Armiento, and E. J. Kennelly. 2012. Antioxidants of therapeutic relevance in COPD from the neotropical blueberry Anthopterus wardii. Food Chemistry 131 (1):119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.08.044.

- Fontana, L., L. Partridge, and V. D. Longo. 2010. Extending healthy life span–from yeast to humans. Science (New York, N.Y.) 328 (5976):321–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539.

- Furukawa, A., S. Tada-Oikawa, S. Kawanishi, and S. Oikawa. 2007. H2O2 accelerates cellular senescence by accumulation of acetylated p53 via decrease in the function of SIRT1 by NAD+ depletion. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 20 (1–4):45–54. doi: 10.1159/000104152.

- Galleano, M., V. Calabro, P. D. Prince, M. C. Litterio, B. Piotrkowski, M. A. Vazquez-Prieto, R. M. Miatello, P. I. Oteiza, and C. G. Fraga. 2012. Flavonoids and metabolic syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1259:87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06511.x.

- Gao, J., Z. Feng, X. Wang, M. Zeng, J. Liu, S. Han, J. Xu, L. Chen, K. Cao, J. Long, et al. 2018. SIRT3/SOD2 maintains osteoblast differentiation and bone formation by regulating mitochondrial stress. Cell Death and Differentiation 25 (2):229–40. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.144.

- Gertz, M., G. T. T. Nguyen, F. Fischer, B. Suenkel, C. Schlicker, B. Fränzel, J. Tomaschewski, F. Aladini, C. Becker, D. Wolters, et al. 2012. A molecular mechanism for direct sirtuin activation by resveratrol. PloS One 7 (11):e49761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049761.

- Godoy, I. D., M. Donahoe, W. J. Calhoun, J. Mancino, and R. M. Rogers. 1996. Elevated TNF-alpha production by peripheral blood monocytes of weight-losing COPD patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 153 (2):633–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564110.

- Gregoretti, I. V., Y. M. Lee, and H. V. Goodson. 2004. Molecular evolution of the histone deacetylase family: Functional implications of phylogenetic analysis. Journal of Molecular Biology 338 (1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.006.

- Grozinger, C. M., E. D. Chao, H. E. Blackwell, D. Moazed, and S. L. Schreiber. 2001. Identification of a class of small molecule inhibitors of the sirtuin family of NAD-dependent deacetylases by phenotypic screening. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (42):38837–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106779200.

- Haigis, M. C., and D. A. Sinclair. 2010. Mammalian sirtuins: Biological insights and disease relevance. Annual Review of Pathology 5:253–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250.

- Halliwell, B., and J. M. Gutteridge. 2015. Free radicals in biology and medicine: Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hallows, W. C., W. Yu, and J. M. Denu. 2012. Regulation of glycolytic enzyme phosphoglycerate mutase-1 by Sirt1 protein-mediated deacetylation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 287 (6):3850–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.317404.

- Hamdy, A. A., and M. A. Ibrahem. 2010. Management of aphthous ulceration with topical quercetin: A randomized clinical trial. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice 11 (4):9–16. doi: 10.5005/jcdp-11-4-9.

- Haohao, Z., Q. Guijun, Z. Juan, K. Wen, and C. Lulu. 2015. Resveratrol improves high-fat diet induced insulin resistance by rebalancing subsarcolemmal mitochondrial oxidation and antioxidantion. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry 71 (1):121–31. doi: 10.1007/s13105-015-0392-1.

- Harman, D. 1956. Aging: A theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. Journal of Gerontology 11 (3):298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298.

- Harris, M. B., R. M. Hoffman, and M. Olesiak. 2021. Chronic exercise mitigates the effects of sirtuin inhibition by salermide on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Cardiovascular Toxicology 21 (10):790–9. doi: 10.1007/s12012-021-09669-8.

- He, M., J. W. Min, W. L. Kong, X. H. He, J. X. Li, and B. W. Peng. 2016. A review on the pharmacological effects of vitexin and isovitexin. Fitoterapia 115:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.09.011.

- Heijmans, B. T., E. W. Tobi, A. D. Stein, H. Putter, G. J. Blauw, E. S. Susser, P. E. Slagboom, and L. H. Lumey. 2008. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (44):17046–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105.

- Heinz, S. A., D. A. Henson, M. D. Austin, F. Jin, and D. C. Nieman. 2010. Quercetin supplementation and upper respiratory tract infection: A randomized community clinical trial. Pharmacological Research 62 (3):237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.05.001.

- Herranz, D., M. Muñoz-Martin, M. Cañamero, F. Mulero, B. Martinez-Pastor, O. Fernandez-Capetillo, and M. Serrano. 2010. Sirt1 improves healthy ageing and protects from metabolic syndrome-associated cancer. Nature Communications 1:3. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1001.

- Hickson, M. 2006. Malnutrition and ageing. Postgraduate Medical Journal 82 (963):2–8. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.037564.

- Hirabayashi, T., R. Nakanishi, M. Tanaka, B. U. Nisa, N. Maeshige, H. Kondo, and H. Fujino. 2021. Reduced metabolic capacity in fast and slow skeletal muscle via oxidative stress and the energy-sensing of AMPK/SIRT1 in malnutrition. Physiological Reports 9 (5):e14763. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14763.

- Hirani, V., V. Naganathan, R. G. Cumming, F. Blyth, D. G. Le Couteur, D. J. Handelsman, L. M. Waite, and M. J. Seibel. 2013. Associations between frailty and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations in older Australian men: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 68 (9):1112–21. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt059.

- Hirao, M., J. Posakony, M. Nelson, H. Hruby, M. Jung, J. A. Simon, and A. Bedalov. 2003. Identification of selective inhibitors of NAD+-dependent deacetylases using phenotypic screens in yeast. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (52):52773–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308966200.

- Horton, J. D., J. L. Goldstein, and M. S. Brown. 2002. SREBPs: Activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 109 (9):1125–31. doi: 10.1172/jci15593.

- Hubbard, B. P., and D. A. Sinclair. 2014. Small molecule SIRT1 activators for the treatment of aging and age-related diseases. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 35 (3):146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.12.004.

- Hwang, J. W., H. Yao, S. Caito, I. K. Sundar, and I. Rahman. 2013. Redox regulation of SIRT1 in inflammation and cellular senescence. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 61:95–110. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.03.015.

- Ishibashi, Y., M. Ito, and Y. Hirabayashi. 2020. The sirtuin inhibitor cambinol reduces intracellular glucosylceramide with ceramide accumulation by inhibiting glucosylceramide synthase. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 84 (11):2264–72. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2020.1794785.

- Jang, M., L. Cai, G. O. Udeani, K. V. Slowing, C. F. Thomas, C. W. Beecher, H. H. Fong, N. R. Farnsworth, A. D. Kinghorn, R. G. Mehta, et al. 1997. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science (New York, N.Y.) 275 (5297):218–20. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.218.

- Jensen, G. L. 2015. Malnutrition and inflammation-“burning down the house”: Inflammation as an adaptive physiologic response versus self-destruction? Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 39 (1):56–62. doi: 10.1177/0148607114529597.

- Jensen, G. L., T. Cederholm, M. I. T. D. Correia, M. C. Gonzalez, R. Fukushima, T. Higashiguchi, G. A. de Baptista, R. Barazzoni, R. Blaauw, A. J. S. Coats, et al. 2019. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition: A consensus report from the Global Clinical Nutrition Community. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 43 (1):32–40. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1440.

- Jensen, G. L., J. Mirtallo, C. Compher, R. Dhaliwal, A. Forbes, R. F. Grijalba, G. Hardy, J. Kondrup, D. Labadarios, I. Nyulasi, International Consensus Guideline Committee, et al. 2010. Adult starvation and disease-related malnutrition: A proposal for etiology-based diagnosis in the clinical practice setting from the International Consensus Guideline Committee. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 34 (2):156–9. doi: 10.1177/0148607110361910.

- Kaiser, M. J., J. M. Bauer, C. Rämsch, W. Uter, Y. Guigoz, T. Cederholm, D. R. Thomas, P. S. Anthony, K. E. Charlton, M. Maggio, Mini Nutritional Assessment International Group, et al. 2010. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: A multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 58 (9):1734–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03016.x.

- Kemelo, M. K., A. Horinek, N. K. Canová, and H. Farghali. 2016. Comparative effects of Quercetin and SRT1720 against D-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatotoxicity in rats: Biochemical and molecular biological investigations. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 20 (2):363–71.

- Kershaw, J., and K. H. Kim. 2017. The therapeutic potential of piceatannol, a natural stilbene, in metabolic diseases: A review. Journal of Medicinal Food 20 (5):427–38. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2017.3916.

- Keusch, G. T. 2003. The history of nutrition: Malnutrition, infection and immunity. The Journal of Nutrition 133 (1):336s–40s. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.1.336S.

- Khan, N., D. N. Syed, N. Ahmad, and H. Mukhtar. 2013. Fisetin: A dietary antioxidant for health promotion. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 19 (2):151–62. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4901.

- Khanra, S., S. K. Juin, J. J. Jawed, S. Ghosh, S. Dutta, S. A. Nabi, J. Dash, D. Dasgupta, S. Majumdar, and R. Banerjee. 2020. In vivo experiments demonstrate the potent antileishmanial efficacy of repurposed suramin in visceral leishmaniasis. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 14 (8):e0008575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008575.

- Khazaei, M. R., M. H. Nasr-Esfahani, F. Chobsaz, and M. Khazaei. 2019. Noscapine inhibiting the growth and angiogenesis of human eutopic endometrium of endometriosis patients through expression of apoptotic genes and nitric oxide reduction in three-dimensional culture model. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 18 (2):836–45. doi: 10.22037/ijpr.2019.1100642.

- Khoruts, A. 2018. Targeting the microbiome: From probiotics to fecal microbiota transplantation. Genome Medicine 10 (1):80. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0592-8.

- Kilic, U., O. Gok, U. Erenberk, M. R. Dundaroz, E. Torun, Y. Kucukardali, B. Elibol-Can, O. Uysal, and T. Dundar. 2015. A remarkable age-related increase in SIRT1 protein expression against oxidative stress in elderly: SIRT1 gene variants and longevity in human. PloS One 10 (3):e0117954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117954.

- Kim, J. H., B. C. Lee, J. H. Kim, G. S. Sim, D. H. Lee, K. E. Lee, Y. P. Yun, and H. B. Pyo. 2005. The isolation and antioxidative effects of vitexin from Acer palmatum. Archives of Pharmacal Research 28 (2):195–202. doi: 10.1007/bf02977715.

- Kim, S., P. A. Thiessen, E. E. Bolton, J. Chen, G. Fu, A. Gindulyte, L. Han, J. He, S. He, B. A. Shoemaker, et al. 2016. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Research 44 (D1):D1202–1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951.

- Kim, S.-J., I. S. M. Zaidul, T. Suzuki, Y. Mukasa, N. Hashimoto, S. Takigawa, T. Noda, C. Matsuura-Endo, and H. Yamauchi. 2008. Comparison of phenolic compositions between common and tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum) sprouts. Food Chemistry 110 (4):814–20. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.050.

- Kirkland, L. L., D. T. Kashiwagi, S. Brantley, D. Scheurer, and P. Varkey. 2013. Nutrition in the hospitalized patient. Journal of Hospital Medicine 8 (1):52–8. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1969.

- Kitamura, Y. I., T. Kitamura, J. P. Kruse, J. C. Raum, R. Stein, W. Gu, and D. Accili. 2005. FoxO1 protects against pancreatic beta cell failure through NeuroD and MafA induction. Cell Metabolism 2 (3):153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.004.

- Kiyak Caglayan, E., Y. Engin-Ustun, A. Y. Gocmen, M. F. Polat, and A. Aktulay. 2015. Serum sirtuin 1 levels in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 35 (6):608–11. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2014.990428.

- Knudsen, A. W., A. Krag, I. Nordgaard-Lassen, E. Frandsen, F. Tofteng, C. Mortensen, and U. Becker. 2016. Effect of paracentesis on metabolic activity in patients with advanced cirrhosis and ascites. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 51 (5):601–9. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1124282.