ABSTRACT

Research Findings: Multiple factors likely influence the language development of young children growing up in low-income homes, potentially including stressors experienced by parents. Here, we ask: (1) What is the association between stress (i.e., economic hardship and parenting stress) and toddlers’ language development? and (2) Does number of hours spent in nonparental childcare moderate the relation between stress (i.e., economic hardship and parenting stress) and toddlers’ language development? Participants were 100 mother-child dyads participating in a longitudinal study when children were 0 to 24 months of age. Results showed a significant interaction between hours spent in nonparental childcare and parenting stress when predicting language growth: when parenting stress was high, childcare hours showed a positive relation with language growth; on the contrary, when parenting stress was low, the relation between childcare hours and language growth showed a negative tendency. Conversely, economic hardship did not predict language growth. Practice or Policy: These findings suggest that one potential approach to facilitate language development for low-income children is to help high-stress families secure early years childcare. Furthermore, programs to reduce parenting stress may help to promote children’s language growth, especially when families are not using nonparental care.

Children from low-income households face many challenges to optimal development relative to their middle-income peers, and this is particularly well-documented for the domain of language development (Merz et al., Citation2019; Noble et al., Citation2007). Indeed, children in low-income households are more likely to experience less and lower-quality parental language exposure (Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2015), which likely contributes to lags in language development relative to their middle-income peers (Farkas & Beron, Citation2004; Fernald et al., Citation2013). There are likely multiple factors that influence the language development of young children growing up in low-income homes, and in the current study, we investigate whether stressors experienced by parents may be an important factor in language development in this population.

Many aspects of living in poverty contribute to elevated stress among caregivers. Adults experiencing poverty are more likely to work long hours under poor conditions (Strazdins et al., Citation2010). They are also more likely to be single parents, experience stigma and racism, and have poorer health and a lower life expectancy (Belle & Doucet, Citation2003; Chokshi, Citation2018; Williams et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, they are more likely than middle-income counterparts to experience high levels of stressful life events, such as moving, divorce, illness, or death of a loved one (Dohrenwend, Citation1985; Reiss et al., Citation2019) and experience more negative emotions on a daily basis (Jakoby, Citation2016), all of which can have significant negative consequences on both physical and mental health (Thoits, Citation2010). These stressors have important implications for families, as they are risk factors for negative child outcomes, such as emotional and behavioral problems (Gershoff et al., Citation2007; Mackler et al., Citation2015).

In this paper, we focus specifically on two distinct aspects of stress that may uniquely contribute to children’s language development, namely economic hardship and parenting stress. The first, economic hardship, is defined as objective and subjective financial strain associated with the stress of having a low income (e.g., not having enough money to pay bills or meet basic needs; McLoyd et al., Citation1994). Research suggests that economic hardship may contribute to negative outcomes for children living in poverty. For example, economic hardship is related to child behavior problems (Jackson et al., Citation2000), cognitive development (Choi & Jackson, Citation2012), and academic skills (Jackson et al., Citation2000; Palermo et al., Citation2018). The second, parenting stress, refers to “the aversive psychological reaction to the demands of being a parent” (Deater-Deckard, Citation1998, p. 315). Research shows that levels of parenting stress are related to child outcomes including behavior problems (Crnic et al., Citation2005), executive function (Hutchison et al., Citation2016), and cognition (Harewood et al., Citation2017).

One mechanism that likely connects both economic hardship and parenting stress to children’s development is parenting. For example, parents with high economic hardship and stress are more likely to exhibit disrupted parenting practices and less responsive parenting than more economically advantaged parents (Conger et al., Citation2002; Jackson et al., Citation2000; Kali & Ryan, 2020). In turn, these can contribute to adverse developmental outcomes in children (Tamis‐lemonda et al., Citation2001; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2019).

Economic hardship and parenting stress are particularly important to understand in early childhood, as the development that occurs during this period has lasting impacts throughout the lifespan (Heckman, Citation2006). This is particularly true for language development during early childhood, as research with diverse populations suggests that language skills are foundational to future success in other areas, including reading and academic achievement (e.g., Durham et al., Citation2007; Hoff, Citation2013; Pace et al., Citation2019; Storch & Whitehurst, Citation2002). Research shows that parenting stress can have detrimental effects on children’s language skills during the preschool years (Harewood et al., Citation2017; Magill-Evans & Harrison, Citation2001; Noel et al., Citation2008) and that these effects are likely mediated through the quality of parent-child interactions (Crnic & Low, Citation2002), with one study finding that parents’ stress fully mediated the relation between poverty and children’s language outcomes (Justice et al., Citation2019). A comparably smaller body of research has shown similar findings with infants and toddlers. For example, Horwitz et al. (Citation2003) found that 18- to 23-month-olds were more likely to experience language delay when parents reported high levels of stress. Other studies have had mixed findings, showing that parents’ stress predicts language development at 12 months but not 18 months (Molfese et al., Citation2010) or does not predict language development among toddlers with language disorders (Vermeij et al., Citation2019).

Little research has examined potential moderating variables that might buffer the relation between stress and children’s language development. One possible moderator of interest is time spent in nonparental childcare, such as care received at a childcare center or by a non-parent in a home setting. Compared to past generations, it has become increasingly common for young children to spent time in some form of nonparental care. A recent report showed that 62.2% of infants and toddlers receive regular nonparental care (Paschall, Citation2019), which in part can be attributed to the shift in women entering the workforce: The labor force participation rate for mothers with children under 3 years of age rose from 34.3% in 1975 to 61.4% in 2015 (Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor, Citation2016). With this dual rise, there has been controversy about the effects of early childcare experiences on infant and toddler’s language development. Findings are mixed, with some studies showing negative effects of early childcare experience on language development (Waldfogel et al., Citation2002) and other studies finding no difference (Institute of Child Health & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, Citation2000). However, more recent research suggests that high-quality childcare experience can exert positive effects on early language development (Pinto et al., Citation2013).

For mothers who are experiencing high levels of economic hardship or parenting stress, time spent in nonparental care may be beneficial for children’s language because they provide children with opportunities to experience positive interpersonal interactions and more language and cognitive stimulation in a context outside of home. Indeed, Vallotton et al. (Citation2012) found children’s enrollment in an Early Head Start program buffered the negative effects of parenting stress on language skills, although they found inconsistent results by dataset and gender. Furthermore, Early Head Start is an evidence-based program that includes intervention for both children and families; effects may differ for other types of nonparental care. In the current study, we use the term nonparental childcare to encompass time spent in any regular care from a nonparent, including from a relative, from a non-relative in a private home, or at a childcare center.

Following from the existing literature, the current study aims to address two research questions: (1) What is the association between stress (i.e., economic hardship and parenting stress) and gains in toddlers’ language development? (2) Does number of hours spent in nonparental childcare moderate the relation between stress (i.e., economic hardship and parenting stress) and toddlers’ language development? Notably, we examine gains in toddlers’ language skills across a year. Many prior studies examine correlations between parenting stress and children’s language skills, yet this design does not allow assessment of directionality; that is, it may be that lower levels of language skill in young children may evoke more parenting stress, rather than the alternative (i.e., that parenting stress contributes to lower levels of language skill in children). Thus, in addressing the aims of the present study, our design allowed us to control for children’s initial levels of language skills and examine the unique relation between stress and change in these skills over time.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The present study represents a subset of participants from a larger study of low-income families in the Midwest. Mothers who were pregnant or had an infant under three-months-old were recruited from Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) centers. To be included in the study, mothers had to be (a) eligible for WIC services, (b) plan on being in the county for the next five years, (c) be 18-years-old, (d) have conversational English skills, and (e) have a child who was not premature or diagnosed with any severe problems. The current study included 100 mothers who contributed data for the relevant measures. At enrollment, mothers were an average of 28-years-old (SD = 4.83 years, Range = 20- to 42-years-old). Forty-four percent of mothers had completed at least some college coursework, 42% had completed high school and 13% had not completed high school. The majority of mothers reported an income of $10,000 or less (41%), whereas 21% reported an annual income of $10,001 to $20,000, and 32% reported an annual income of more than $20,001 (6% unreported). Additionally, 22% percent of mothers were married, 47% were single, 22% were single and living with a partner, and 9% were divorced, separated, or widowed. Most mothers spoke only English at home (85.5%). The sample included 56% female children, with 46% of parents reporting that their children were White, 37% African-American, 3% Hispanic, 2% Asian, and 12% reporting multiple races/ethnicities.

Procedures

This study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave informed consent. At each timepoint, mothers were provided with diapers and wipes, small monetary gift cards, and a children’s storybook as compensation.

Timepoint 1

The first timepoint occurred when the infant was nine- to twelve-months-old. During a 90-minute home visit, we conducted an assessment of child language.

Timepoint 2

The second timepoint was when the infant was 15- to 19-months-old. These 30-minute meetings occurred in either the mothers’ home or a neutral location (e.g., McDonald’s, libraries). Mothers could attend with or without their child. At this timepoint, we collected data on parenting stress, economic hardship, and time spent in nonparental childcare.

Timepoint 3

The third timepoint occurred when the child was 21- to 24-months-old. During a 90-minute home visit, children’s language skills were assessed.

Measures

Parenting Stress

Parenting stress was measured during timepoint 2 using the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (Abidin, Citation2012), which has a Cronbach’s alpha of .95 and is highly correlated with the full-length PSI (r = .98). The short form of the PSI included 36 items that assessed parenting stress based on the mothers’ perception of mother-child interactions. (e.g., “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent”; “I expected to have closer and warmer feelings for my child than I do, and this bothers me”). Items were scored using a one- (strongly disagree) to five-point (strongly agree) Likert scale. The total stress score was used in analyses (range = 36 to 131).

Economic Hardship

Economic hardship was measured during timepoint 2 using the Economic Hardship scale (Yoshikawa et al., Citation2008). The measure has four questions scored 0 (No) or 1 (Yes) on not being able to pay bills for utilities, rent, or mortgage over the past year. The total score was used in the analysis, ranging from 0 to 4.

Time Spent in Nonparental Childcare

Time spent in nonparental childcare was reported at timepoint 2. Mothers were asked whether their child was currently receiving care on a regular basis from a relative other than a parent, a non-relative in a private home, or at a childcare center. If they reported yes to any of the childcare category, we further asked the number of hours their child receiving that type of childcare in a regular week. Then, we calculated the total hours of each child receiving any of the three types of nonparental childcare.

Language

Children’s language skill was assessed using the Bayley Infant Scales of Development – III (Bayley, Citation2006) during home visits at timepoints 1 and 3. The receptive language scale included 49 items that measured pre-verbal behaviors and vocabulary. The expressive language scale included 48 items measuring pre-verbal communication, vocabulary, and morpho-syntactic development. The raw scores were used in the analysis, in which we modeled gains by predicting timepoint 3 language while controlling for timepoint 1 language.

Demographic Control Variables

Demographics were collected in surveys at enrollment when mothers were pregnant or infants were less than 3 months of age (i.e., child’s race, highest level of mother education and marital status) or when infants were between 4 and 7 months of age (mother’s working status). For analyses, race was coded as whether the child was African-American/Black; mother education was dummy coded for college degree or above; marital status was dummy coded for married; and their working status was coded as working (including full-time, part-time, and self-employed) or not working (including out of work, homemaker, student, and unable to work).

Results

The mean of mothers’ reported parenting stress was 62.18 (SD = 18.70); on average mothers disagreed or strongly disagreed with items indicating high parenting stress, as shown in . However, mothers generally reported a relatively high level of economic hardship (M = 3.21, SD = 0.99 on the scale ranging from 0 to 4). On average, children spent 12.16 hours in non-parental childcare per week (SD = 17.33, range = 0–60), with 57% not receiving any non-parental childcare. As expected based on typical developmental trajectories, children’s language skill grew from timepoint 1 to timepoint 3, from an average score of 21.59 (SD = 5.53, range = 7–34) to an average score of 47.01 (SD = 10.31, range = 25.73), which was statistically significant (t = 24.62, p < .001).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all study variables.

Prior to conducting the main analyses for the two study aims, we tested four potential covariates to examine their contribution to children’s language skills. These potential covariates were selected because prior research has shown links between each and children’s language skills (e.g., Pungello et al., Citation2009; Son & Peterson, Citation2017; Waldfogel et al., Citation2002). Our preliminary findings showed that child’s race, mother’s marital status, and mother’s working status did not significantly predict children’s language skills (ps > .37). Mother’s education was the only significant predictor of language skills (p = .048) and was thus included in our primary models.

To examine the role of parenting stress in predicting children’s language skills, a regression model was estimated predicting timepoint 3 language from parenting stress, economic hardship, and childcare hours with timepoint 1 language included as a predictor to model gains, and controlling for mother’s education. Parenting stress, economic hardship, and childcare hours were not significantly associated with children’s language gains from timepoint 1 to timepoint 3 (, Model 1).

Table 2. Moderation of parenting stress and economic hardship on the relation between childcare hours and language development.

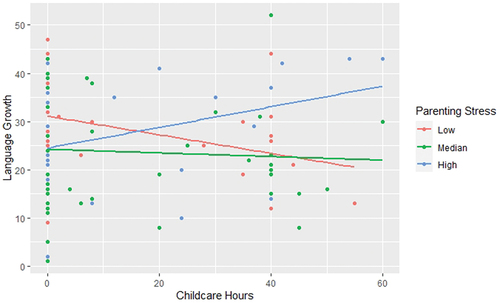

To examine whether time spent in nonparental childcare moderated the relation between parenting stress and language, we included the interaction effect between parenting stress and hours spent in nonparental childcare (, Model 2). Results showed this interaction effect was positively significant (B = 0.01, p = .008). To visualize this moderation effect, we categorized parenting stress based on its quantiles into three groups – low (below Q1), median (Q1 ~ Q3), and high (above Q3). As seen in , when parenting stress was high, childcare hours showed a positive relation with language growth; on the contrary, when parenting stress was low, the relation between childcare hours and language growth showed a negative tendency.

Figure 1. Moderation effect of parenting stress.

To examine the potential moderation effect of childcare hours on the relation between economic hardship and language, the interaction effect between economic hardship and childcare hours was tested (, Model 3). It, however, was not statistically significant (B = −0.05, p = .342).

Discussion

Socioeconomic disparities in children’s language skills emerge early in the lifespan and have implications for later development and achievement (Farkas & Beron, Citation2004; Fernald et al., Citation2013). One way to reduce these disparities is to identify mechanisms associated with poverty that inhibit young children’s language development and to determine protective factors that may reduce these associations. In this spirit, we examined how economic hardship and parenting stress within a sample of low-income families predicted children’s language development over a 1-year period and how time spent in nonparental care may buffer these relations. Our findings suggest that although time spent in nonparental care is related to lower levels of language growth among mothers with low levels of parenting stress, when mothers have high levels of parenting stress, childcare hours is related to higher language growth. These data indicate that time spent in nonparental care may serve to buffer the negative effects of parenting stress on children’s early language development. Conversely, economic hardship was not related to language growth, either directly or as moderated by childcare.

There are several plausible explanations for the interplay between parenting stress and time spent in nonparental care with respect to influence on children’s language skills. First, the environments children experience in nonparental care may promote language development (Justice et al., Citation2018). This aligns with research finding that positive interactions between 3-year-olds and caregivers in child-care settings serves as a buffer for lags in language development when there is low maternal language input at home (Vernon-Feagans & Bratsch-Hines, Citation2013). An extensive body of research shows that early language development is highly contingent on children’s interactions with others, with individual differences in vocabulary associated with the quantity and quality of the language that children hear in their environment (e.g., Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2015), meaning that an enhancement in the language to which children are exposed is likely to have positive implications for language development. On the other hand, when parenting stress is low, the language environment in the home may be more positive, such that time spent in childcare, where the child to adult ratio is likely higher than in the home setting, is somewhat detrimental to children’s language skills. This would be in line with some prior studies showing negative effects of early childcare experiences on language outcomes (e.g., Bernal & Keane, Citation2011; Han et al., Citation2001; Waldfogel et al., Citation2002).

Another possible explanation for this interaction effect is that having nonparental care could reduce mother’s stress, which in turn allowed them to have more language-promoting interactions with their child at home. This potential mechanism is aligned with family stress models highlighting the contribution of stress to less optimal parenting (Conger et al., Citation2002). Indeed, the effects of parenting stress on language are likely to be mediated through the quality of parent-child interactions (Crnic & Low, Citation2002; Justice et al., Citation2019).

Unlike parenting stress, economic hardship may not be directly related to language growth among this population because all of these families were experiencing poverty and high levels of economic hardship, as reflected in descriptive statistics for this variable. Thus, we may have had reduced variability on this measure, leading to an inability to see any relation with children’s language growth. Given prior research (e.g., Jackson et al., Citation2000), it is possible that economic hardship would predict language growth, and perhaps be moderated by childcare, among a population including families from middle and upper-income backgrounds. Another possibility is that the operationalization of economic hardship requires refinement and that a more nuanced measure would have tapped into meaningful variability among these families, despite all coming from low-income backgrounds.

These findings highlight the importance of considering parenting stress and childcare among low-income families. Although more research is needed to identify the mechanism, our findings show that receiving regular nonparental care during the second year of life is beneficial to the language development of children in low-income families with heightened levels of parenting stress. However, in the U.S., few supports are available to help families secure and pay for childcare in the first years of life. Although many states and cities have expanded investment in early childhood care and education, the vast majority of this money has gone to fund preschool-aged programming (Isaacs et al., Citation2019). The primary funding to help low-income families is Publicly Funded Childcare, which only serves one out of seven potentially eligible children (Chien, Citation2019). Households earning less than $25,000 spend over 40% of their income on average for childcare for 1-year-olds, more than double the income percentage that higher-income families spend (Hotz & Wiswall, Citation2019). Future policy efforts should consider the benefits of regular nonparental care for infants and toddlers and explore ways to subsidize costs for families from low-income backgrounds. Alternatively, boosting family income early in the life course could both help families access nonparental care and potentially reduce stress. For example, there is overwhelming evidence that poverty early in the life course leads to negative outcomes throughout childhood and adulthood (Duncan & Hoynes, Citation2021).

Our findings also suggest that programs to reduce parenting stress may help to promote children’s language growth, especially when families are not using nonparental care. For example, prior research shows that home visiting programs can reduce parents’ stress, which then leads to positive impacts on children (Sweet & Appelbaum, Citation2004; see, also Vismara et al., Citation2020). More recent efforts have focused on teletherapy to reduce parenting stress (James Riegler et al., Citation2020), especially relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, investing in programs aimed at reducing parenting stress may also promote language development among children in low-income families. Furthermore, two generation programs, such as Early Head Start, which provides childcare as well as services such as home visits, may be particularly effective at supporting language development in the earliest years (Xue et al., Citation2021).

Although these findings document the potential buffering effect of regular nonparental care on language growth, the current study has several important limitations. First, our sample was drawn from an urban environment, and future research should investigate these links in other contexts. For example, this effect may be heightened in a rural context given geographical challenges to finding quality nonparental care. Additionally, our category of nonparental childcare was quite heterogenous, covering in-home relative care, home-based childcare, and center-based care. Given the limited sample size, we were unable to examine the role that different types of care may play and the extent to which having high-quality care contributes to the effects seen here. Future research should examine the types of care that are most beneficial to language growth at this early stage of development. Finally, we were able to collect language assessments at only two timepoints during this phase of development; more frequent information about children’s developing skills may shed additional light on the substantial gains during this period and on inter-individual variability.

In conclusion, our results indicate that among low-income families, the effect of parenting stress on language development during toddlerhood is buffered by participating in nonparental childcare, whereas economic hardship did not have such an effect in this population. This finding suggests that one way to improve children’s outcomes may be to develop programs that would help families secure childcare during the early years of a child’s life. Furthermore, efforts to reduce parenting stress for families who are not using nonparental care are also likely to promote language development among low-income children.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the children and families who participated in this research, as well as the Kids in Columbus project team, especially Abel Koury, Jill Twersky, Randi Bates, and Hui Jiang. This research was partially supported by the generous contribution of the Crane family to the Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy. We would also like to thank our partner, Columbus Public Health, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Disclosure Statement

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Abidin, R. R. (2012). Parenting stress index, (PSI-4). Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Bayley, N. (2006). Bayley scales of infant and toddler development. PsychCorp, Pearson.

- Belle, D., & Doucet, J. (2003). Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among U.S. women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 27(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00090

- Bernal, R., & Keane, M. P. (2011). Child care choices and children’s cognitive achievement: The case of single mothers. Journal of Labor Economics, 29(3), 459–512. https://doi.org/10.1086/659343

- Chien, N. (2019). Factsheet: Estimates of child care eligibility & receipt for fiscal year 2015. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

- Choi, J. K., & Jackson, A. P. (2012). Nonresident fathers’ parenting, maternal mastery and child development in poor African American single-mother families. Race and Social Problems, 4(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-012-9070-x

- Chokshi, D. A. (2018). Income, poverty, and health inequality. Jama, 319(13), 1312–1313. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2521

- Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179.

- Crnic, K., & Low, C. (2002). Handbook of Parenting, Volume 5: Practical Issues in Parenting. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 243–267.

- Crnic, K. A., Gaze, C., & Hoffman, C. (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.384

- Deater-Deckard, K. (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 314–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x

- Dohrenwend, B. S. (1985). Social status and responsibility for stressful life events. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 7(1–4), 105–127. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612848509009452

- Duncan, G. J., & Hoynes, H. (2021). Reducing child poverty can promote children’s development and productivity in adulthood. Society for Research in Child Development Evidence Brief. No 11. Society for Research in Child Development. https://www.srcd.org/sites/default/files/resources/CEB-Child%20Tax%20Credits_final.pdf

- Durham, R. E., Farkas, G., Scheffner, C., Tomblin, J. B., & Catts, H. W. (2007). Kindergarten oral language skill : A key variable in the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 25(4), 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2007.03.001

- Farkas, G., & Beron, K. (2004). The detailed age trajectory of oral vocabulary knowledge: Differences by class and race. Social Science Research, 33(3), 464–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.08.001

- Fernald, A., Marchman, V. A., & Weisleder, A. (2013). SES differences in language processing skill and vocabulary are evident at 18 months. Developmental Science, 16(2), 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12019

- Gershoff, E. T., Aber, J. L., Raver, C. C., & Lennon, M. C. (2007). Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Development, 78(1), 70–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x

- Han, W. J., Waldfogel, J., & Brooks‐Gunn, J. (2001). The effects of early maternal employment on later cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 336–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00336.x

- Harewood, T., Vallotton, C. D., & Brophy‐Herb, H. (2017). More than just the breadwinner: The effects of fathers’ parenting stress on children’s language and cognitive development. Infant and Child Development, 26(2), e1984. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1984

- Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312(5782), 1900–1902. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128898

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R., Owen, M. T., Golinkoff, R. M., Pace, A., Yust, P. K. S., & Suma, K. (2015). The contribution of early communication quality to low-income children’s language success. Psychological Science, 26(7), 1071–1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615581493

- Hoff, E. (2013). Interpreting the early language trajectories of children from low-SES and language minority homes: Implications for closing achievement gaps. Developmental Psychology, 49(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027238

- Horwitz, S. M., Irwin, J. R., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Heenan, J. M. B., Mendoza, J., & Carter, A. S. (2003). Language delay in a community cohort of young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(8), 932–940. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CHI.0000046889.27264.5E

- Hotz, V. J., & Wiswall, M. (2019). Child care and child care policy: Existing policies, their effects, and reforms. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 686(1), 310–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716219884078

- Hutchison, L., Feder, M., Abar, B., & Winsler, A. (2016). Relations between parenting stress, parenting style, and child executive functioning for children with ADHD or autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3644–3656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0518-2

- Institute of Child Health, N., & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. (2000). The relation of child care to cognitive and language development. Child Development, 71(4), 960–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00202

- Isaacs, J. B., Lou, C., Hahn, H., Lauderback, E., & Quackenbush, C. (2019). Public spending on infants and toddlers in six charts. Urban Institute.

- Jackson, A. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., Huang, C. C., & Glassman, M. (2000). Single mothers in low-wage jobs: Financial strain, parenting, and preschoolers’ outcomes. Child Development, 71(5), 1409–1423. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00236

- Jakoby, N. (2016). Socioeconomic status differences in negative emotions. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3895

- James Riegler, L., Raj, S. P., Moscato, E. L., Narad, M. E., Kincaid, A., & Wade, S. L. (2020). Pilot trial of a telepsychotherapy parenting skills intervention for veteran families: Implications for managing parenting stress during COVID-19. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 290. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000220

- Justice, L. M., Jiang, H., & Strasser, K. (2018). Linguistic environment of preschool classrooms: What dimensions support children’s language growth? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 42, 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.09.003

- Justice, L. M., Jiang, H., Purtell, K. M., Schmeer, K., Boone, K., Bates, R., & Salsberry, P. J. (2019). Conditions of poverty, parent-child interactions, and toddlers’ early language skills in low-income families. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23(7), 971–978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-02726-9

- Mackler, J. S., Kelleher, R. T., Shanahan, L., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & O’Brien, M. (2015). Parenting stress, parental reactions, and externalizing behavior from ages 4 to 10. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(2), 388–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12163

- Magill-Evans, J., & Harrison, M. J. (2001). Parent-child interactions, parenting stress, and developmental outcomes at 4 years. Children’s Health Care, 30(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326888CHC3002_4

- McLoyd, V. C., Jayaratne, T. E., Ceballo, R., & Borquez, J. (1994). Unemployment and work interruption among African American single mothers: Effects on parenting and adolescent socioemotional functioning. Child Development, 65(2), 562–589. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131402

- Merz, E. C., Wiltshire, C. A., & Noble, K. G. (2019). Socioeconomic inequality and the developing brain: Spotlight on language and executive function. Child Development Perspectives, 13(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12305

- Molfese, V. J., Rudasill, K. M., Beswick, J. L., Jacobi-Vessels, J. L., Ferguson, M. C., & White, J. M. (2010). Infant temperament, maternal personality, and parenting stress as contributors to infant developmental outcomes. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56(1), 49–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0679-7

- Noble, K. G., McCandliss, B. D., & Farah, M. J. (2007). Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Developmental Science, 10(4), 464–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00600.x

- Noel, M., Peterson, C., & Jesso, B. (2008). The relationship of parenting stress and child temperament to language development among economically disadvantaged preschoolers. Journal of Child Language, 35(4), 823–843. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000908008805

- Pace, A., Alper, R., Burchinal, M. R., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Measuring success: Within and cross-domain predictors of academic and social trajectories in elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46, 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.001

- Palermo, F., Ispa, J. M., Carlo, G., & Streit, C. (2018). Economic hardship during infancy and US Latino preschoolers’ sociobehavioral health and academic readiness. Developmental Psychology, 54(5), 890. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000476

- Paschall, K. (2019). Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/nearly-30-percent-of-infants-and-toddlers-attend-home-based-child-care-as-their-primary-arrangement

- Pinto, A. I., Pessanha, M., & Aguiar, C. (2013). Effects of home environment and center-based child care quality on children’s language, communication, and literacy outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.07.001

- Pungello, E. P., Iruka, I. U., Dotterer, A. M., Mills-Koonce, R., & Reznick, J. S. (2009). The effects of socioeconomic status, race, and parenting on language development in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 45(2), 544. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013917

- Reiss, F., Meyrose, A. K., Otto, C., Lampert, T., Klasen, F., Ravens-Sieberer, U., & Hashimoto, K. (2019). Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: Results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PloS one, 14(3), e0213700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213700

- Son, S. C., & Peterson, M. F. (2017). Marital status, home environments, and family strain: Complex effects on preschool children’s school readiness skills. Infant and Child Development, 26(2), e1967. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1967

- Storch, S. A., & Whitehurst, G. J. (2002). Oral language and code-related precursors to reading: Evidence from a longitudinal structural model. Developmental Psychology, 38(6), 934. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.6.934

- Strazdins, L., Shipley, M., Clements, M., Obrien, L. V., & Broom, D. H. (2010). Job quality and inequality: Parents’ jobs and children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties. Social Science and Medicine, 70(12), 2052–2060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.041

- Sweet, M. A., & Appelbaum, M. I. (2004). Is home visiting an effective strategy? A meta‐analytic review of home visiting programs for families with young children. Child Development, 75(5), 1435–1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00750.x

- Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Luo, R., McFadden, K. E., Bandel, E. T., & Vallotton, C. (2019). Early home learning environment predicts children’s 5th grade academic skills. Applied Developmental Science, 23(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1345634

- Tamis‐lemonda, C. S., Bornstein, M. H., & Baumwell, L. (2001). Maternal responsiveness and children’s achievement of language milestones. Child Development, 72(3), 748–767. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00313

- Thoits, P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1_suppl), S41–S53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383499

- Vallotton, C. D., Harewood, T., Ayoub, C. A., Pan, B., Mastergeorge, A. M., & Brophy-Herb, H. (2012). Buffering boys and boosting girls: The protective and promotive effects of Early Head Start for children’s expressive language in the context of parenting stress. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(4), 695–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.03.001

- Vermeij, B. A., Wiefferink, C. H., Knoors, H., & Scholte, R. (2019). Association of language, behavior, and parental stress in young children with a language disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 85, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.11.012

- Vernon-Feagans, L., & Bratsch-Hines, M. E. (2013). Caregiver–child verbal interactions in child care: A buffer against poor language outcomes when maternal language input is less. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4), 858–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.08.002

- Vismara, L., Sechi, C., & Lucarelli, L. (2020). Reflective parenting home visiting program: A longitudinal study on the effects upon depression, anxiety and parenting stress in first-time mothers. Heliyon, 6(7), e04292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04292

- Waldfogel, J., Han, W. J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2002). The effects of early maternal employment on child cognitive development. Demography, 39(2), 369–392. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2002.0021

- Williams, D. R., Mohammed, S. A., Leavell, J., & Collins, C. (2010). Race, socioeconomic status and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x

- Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor. (2016). Working mothers issue brief. https://www.dol.gov/wb/resources/WB_WorkingMothers_2016_v5_June10.pdf

- Xue, Y., Baxter, C., Jones, C., Shah, H., Caronongan, P., Aikens, N., … Atkins-Burnett, S. (2021). Early Head Start programs, staff, and infants/toddlers and families served: Baby FACES 2018 data tables. OPRE report 2021-92. Administration for Children & Families.

- Yoshikawa, H., Godfrey, E. B., & Rivera, A. C. (2008). Access to institutional resources as a measure of social exclusion: Relations with family process and cognitive development in the context of immigration. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2008(121), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.223