Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore the junior to senior transition from professional contract to an established first-team player in an English men’s professional football team. Six players were purposively sampled across four suggested phases of transition: preparation; orientation; adaptation; and stabilization. A series of three interviews explored their past and current experiences, as well as their future ambitions. Eight higher-order themes were developed using thematic analysis: performance culture; opportunity; organizational strategy; contracts; relationships; motivation; power dynamics; and dual career. Several general adaptation factors found in previous research were present, along with four unique findings. The current study sets the opportunity to play within the first team as the primary factor in career progression. Without the opportunity, a “gray period” develops when a player is in an undefined phase without specific goals. This complex transition is further complicated by the short-term nature of contracts, which influences motivation and the ability to see the big picture. Throughout the transition, receiving support from key stakeholders was challenged by their role as gatekeepers of playing time and future contracts. Organizations should seek to manage transitions through a hands-on approach, providing the necessary support throughout the gray period, while being aware of the limitations of support from those with power over opportunity. Future research should look to explore the suggested gray period and the challenges that develop without continual opportunity.

Lay summary: Professional football players at different stages in their career discussed the challenges experienced in their journey to becoming a regular first-team player. Those players that were not getting the opportunity to play felt isolated and unable to discuss their concerns. Implications for football clubs managing this transition are discussed.

Providing opportunity in the senior team while managing players with no opportunity

Availability and awareness of support systems outside of decision-makers

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Researchers have pointed to the junior-to-senior transition as the most challenging career stage in sport (Drew et al., Citation2019; Stambulova et al., Citation2009), and English professional football (soccer) specifically (Mitchell et al., Citation2020). These challenges are further supported by the England manager criticizing the low number of minutes played by English players in the Premier League (Morgan, Citation2019), and a growing number of players moving abroad to seek opportunities in first-team football (Lawrence, Citation2019). Although these trends exist, football clubs spend millions of pounds on youth academies in the hopes of producing players for the first team (Morris et al., Citation2015; Relvas et al., Citation2010). Producing homegrown players is necessary to comply with the English Football League (EFL) rules and in continental competitions in Europe (Relvas et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, for clubs in the EFL selling academy-developed players is a significant revenue source, allowing reinvestment of resources (Morris et al., Citation2015).

Research attention on the junior-to-senior transition has grown in the last five years (Mitchell et al., Citation2020; Morris et al., Citation2015; Morris, Tod, & Eubank, Citation2016; Morris, Tod, et al., Citation2016; Swainston et al., Citation2020). This research has typically focused on the immediate move from academy player (U18) to the first-team environment (e.g., Morris, Tod, & Eubank, Citation2016). However, the typical transition pathway in professional football is rarely a jump straight into the first team matchday squad. Indeed, when the Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP) was developed in 2012, an U23 Premier League was developed with the aim of bridging the gap between the academy and the first team (EPPP, Citation2010). Furthermore, the transition does not stop upon that first experience, and therefore, Swainston et al. (Citation2020) recommended exploring how the transition develops past the initial common experience of contract award. A longitudinal exploration of career progression in the junior-to-senior transition in professional sport is limited, although Stambulova et al. have recently developed an empirical model applied to semiprofessional ice hockey (Pehrson et al., Citation2017; Stambulova et al., Citation2017).

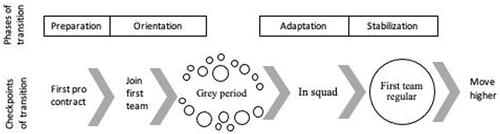

The empirical model (Pehrson et al., Citation2017; Stambulova et al., Citation2017) was developed as an extension of the athletic career transition model (Stambulova, Citation2003), incorporating elements of the holistic athletic career model (Wylleman & Lavallee, Citation2004). The initial athletic career transition model (Stambulova, Citation2003) was used to outline the demands, barriers, resources, and coping strategies for each phase of the transition. The holistic athletic career model (Wylleman & Lavallee, Citation2004) further considered the development of the players outside of their sport and how these experiences might influence the overall transition (Stambulova et al., Citation2017). The ensuing empirical model describes four phases: preparation; orientation; adaptation; and stabilization, that were initially proposed to occur over four competitive seasons.

The preparation phase occurs before the full-time move to the senior environment beginning with the first experience in the senior team (Stambulova et al., Citation2017). During this phase, athletes seek to become part of the senior team and learn the requirements for senior sport (Pehrson et al., Citation2017). These outcomes are developed through the opportunity to train with the senior squad before the full-time transition (Morris et al., Citation2015; Swainston et al., Citation2020), via a process that seeks to reduce the perceived gap between junior and senior competition (Pehrson et al., Citation2017). Researchers have called for interventions aimed at reducing this gap by developing knowledge of the transition itself, educating players and parents, and using mentors to improve awareness of the demands (Drew et al., Citation2019; Morris et al., Citation2015). Although this remains an underdeveloped area of the literature, athletes who have received such a focused intervention have reported an enhanced knowledge of the transition and the development of coping skills (Pummell & Lavallee, Citation2019).

As players transition to the senior environment full time, during the orientation phase, they look to find their role in the team and understand the requirements of senior competition (Pehrson et al., Citation2017). Fitting into the new senior environment comes with challenges such as a harsher, more competitive dynamic (Røynesdal et al., Citation2018; Swainston et al., Citation2020), and a contrast from the development centered approach often taken in youth sport (Drew et al., Citation2019; Morris, Tod, et al., Citation2016). Relationships with senior players are valuable for learning via mentoring during this phase (Morris, Tod, et al., Citation2016; Swainston et al., Citation2020) yet these same players are also seen as rivals for playing time (Røynesdal et al., Citation2018). Simultaneous to adjusting to the new environment, athletes need to adapt to the increased standard in training and competition (Morris, Tod, et al., Citation2016; Swainston et al., Citation2020). This adaptation requires physical development (Morris et al., Citation2015), tactical adjustments (Pehrson et al., Citation2017; Swainston et al., Citation2020), and psychological skills (Morris, Tod, et al., Citation2016; Swainston et al., Citation2020). Showing progress in these areas is critical in earning the trust of management, a key factor when progressing in the transition (Pehrson et al., Citation2017; Røynesdal et al., Citation2018).

Once players have settled into the first-team environment, they enter the adaptation phase where they try to establish themselves in the team and gain experience of senior competition (Pehrson et al., Citation2017; Stambulova et al., Citation2017). To gain experience, it is necessary to understand and fulfill what coaches require from senior players (Røynesdal et al., Citation2018). In football, this might mean going on loan to gain experience and prove you can manage the increased demands (Røynesdal et al., Citation2018; Swainston et al., Citation2020). Although earning the initial opportunity is a significant challenge, it is just the beginning of a process of establishing oneself in the senior team (Morris et al., Citation2015). Once they have fully established themselves in the senior team, players reach the stabilization phase. At this point, they look to perform consistently, take more responsibility in the group and team including evolving to leadership roles, and potentially look to further their career at a new level (Pehrson et al., Citation2017).

As this transition pathway is highly cultural and sport-specific, an investigation is required in contexts other than Swedish ice hockey (Stambulova et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the junior-to-senior transition from professional contract to an established first-team player in an English men’s professional football team. Specifically, the primary research question is, “what do players experience at different stages of the junior to senior transition in professional football?” The secondary question is, “what are the major checkpoints (points of change) in the transition from professional contract to first-team regular?” As the existing research base has focused on the immediate transition period (e.g., Morris, Tod, & Eubank, Citation2016; Swainston et al., Citation2020) this study answers the call for a broader exploration of the challenges and experience across the entire transition. Furthermore, previous research has been heavily reliant on recall interviews of successful or unsuccessful transitions. In contrast, this study seeks to explore participants’ experiences in varying phases of the transition.

Methods

Methodological coherence

Establishing rigor in qualitative work is essential to ensuring research integrity, yet how one engages with rigor is a highly debated process (Morse, Citation2020; Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). Rigor, in this study, began with the research team engaging in an armchair walkthrough as developed by Mayan (Citation2009). At the outset of the study, the research team discussed and aligned our research question to our epistemological and ontological approach, methodology, data collection technique, and method of data analysis. This approach ensured methodological coherence and transparency of our methodological choices, in turn enhancing rigor and credibility (Mayan, Citation2009). Furthermore, credibility was established as the lead researcher was embedded in the club as the academy sport psychologist as part of a dual funded PhD and therefore a naturalistic approach was most appropriate. The naturalistic approach was guided by our ontological position of relativism, in which we assume multiple realities and multiple truths to the phenomena in question, and the epistemological approach of subjectivism, where knowledge is developed through subjective experience, and socially constructed (Bradshaw et al., Citation2017). Our method, qualitative description, was chosen in line with these positions (Sandelowski, Citation2000, Citation2010). Data were collected using multiple semi-structured interviews, analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), and then presented thematically. Finally, we engaged with rigor through our goal of contributing to open science by providing access to our coding framework, interview guides, and theme development through the open science framework (https://osf.io/6mjrh/) to allow the reader to further interrogate this process (Tamminen & Poucher, Citation2018).

Qualitative description

Qualitative description was developed from a naturalistic approach, whereby a phenomenon is studied in its natural context (Sandelowski, Citation2000, Citation2010). In line with our qualitative description methodology, we attempted to allow the phenomena to emerge as if it were not under study (Sandelowski, Citation2000), using participants “in the midst” of the experience (Sullivan-Bolyai et al., Citation2005). Furthermore, using an interviewer who was embedded at the club allowed for this subjective experience to be understood and described. Our goal was then to present the data in the voice of the participants with limited interpretation (Bradshaw et al., Citation2017; Sandelowski, Citation2000). The simplistic, yet rich nature of the description should aid the data being used directly in an applied setting (Sandelowski, Citation2000, Citation2010; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., Citation2005).

Participants and sampling

Stambulova’s empirical model (Citation2017) was used as a sampling tool to recruit participants across the proposed phases of transition. This sampling technique allowed for a rich collection of experience during the transition, helping to identify key “checkpoints.” As both the first and second author were embedded within the football club (as academy and first team psychologist respectively), the research team identified players that aligned with the suggested phases. Participants were invited if they had a professional contract and spent at least three years in the club’s academy. Furthermore criteria were developed to fit each phase of transition: (1) U18 players with professional contracts yet to make the full-time transition, (2) players in their first year as a professional, (3) second to fourth-year professionals without having an established place in the first team, and (4) newly established members of the first team. Three players were identified for the preparation and orientation phases, with one from each phase electing not to participate. Two players were identified for the adaptation phase; however, one player left the club following the participant recruitment stage, resulting in only one available participant. Only one participant was identified and participated in the stabilization phase (see ). Players were ensured that participation or nonparticipation would not affect their standing within the football club, and only the research team would see all non-anonymized data.

Table 1. Participants’ (not their real names) demographic information.

Data collection and analysis

Following ethical approval from the researchers’ institutional ethics committee, the lead researcher contacted the eligible participants and briefed them about the study, its aims, and what was required to participate. The series of three interviews for each participant were done roughly within one month of each other based on their availability during the season. All 18 interviews were completed over four months.

The research team developed unique interview guides for each phase and participant based on a basic understanding of the player’s career and previous junior-to-senior transitions research (e.g., Morris, Tod, & Eubank, Citation2016; Stambulova et al., Citation2017). To further develop the interview guides a pilot interview was conducted with a former player at the club who had experienced the transition. The first interview focused primarily on the participant’s career up to the current date, including their time in the academy and earning a professional contract. Probing questions were used to explore their views of their career, including specific challenges and opportunities in different phases of their transition. Using an iterative process of data collection and analysis, the first interview was transcribed verbatim, and a guide was created for the second interview. Allowing time between interviews for analysis is suggested to strengthen the quality of the data throughout the entire data collection process (Jones & Harwood, Citation2008).

The second interview began with each participant having the opportunity to discuss what they felt relevant from the first interview. It also included specific questions and quotations from the first interview to enable the participant to revisit and expand upon critical events and interpretation of the data. The interview then moved on to discuss their current phase of transition. Following the interview, it was transcribed verbatim, and the third interview guide was created. The same process was followed for the third interview with the latter part focused on how they viewed the future phases of transition (see for interview lengths).

Table 2. The duration of the three interviews for each participant.

A thematic analysis was used to analyze the data using the phases set out by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). This method of analysis was deemed appropriate for a qualitative description, as described by Sandelowski (Citation2010). The first two phases of thematic analysis were completed iteratively between interviews. Following the final interview, coding was completed, and the lead researcher sorted the codes into potential themes. The research team then discussed the possible themes that were developed. Engaging the research team, in particular the third author who is a qualitative expert, helped drive rigor through a consistent focus on developing specific criteria for each theme. These themes were then checked against the coding by the lead researcher. The research team then refined the themes to accurately reflect the coding and were true to the data set. Finally, the raw themes were sorted into lower-order themes and then higher-order themes.

Data representation

In a qualitative description, the presentation of results should remain close to the data, giving voice to the participants’ experiences using their language (Neergaard et al., Citation2009). To stay true to our participants’ voices, several “British” terms are used in our findings. A list of terms and definitions is provided in the supplementary materials (https://osf.io/6mjrh/). The results can be presented in a way that best represents the data (Sandelowski, Citation2000; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., Citation2005), whether that be by prevalence, theme, or chronologically. Here we used Stambulova et al. (Citation2017); (Pehrson et al., Citation2017) empirical model, to present our themes by phase. This allows the commonalities, differences, and progression to be presented together, allowing for easier “generalizations” to be made by the reader.

Results

The participants’ experiences were analyzed, and eight higher order and 15 lower order themes were developed. The higher order themes were performance culture, opportunity, organizational strategy, contracts, relationships, motivation, power dynamics, and dual career (see ). It is important to note that not all of these higher order themes are present in each phase but instead reflect the data set as a whole (including data presented in the supplementary materials. To provide as much focus as possible on our unique findings, some of the results (including participant quotations) have been moved to the supplementary materials (https://osf.io/6mjrh/).

Table 3. Thematic analysis higher and lower order themes.

Preparation phase

At the core of this phase was an exposure to the first team helping them prepare for the future. Sam and Ryan were in this phase—academy players with professional contracts yet to join the first team—at the time of the interviews. The other four participants reflected upon their experiences in this phase as a part of the first interview.

Organizational strategy

U23 group. During the season that data collection occurred, the club created an U23 training session, once a week, for young pro’s and U18 academy players. They also entered an U23 cup competition. This group was not a full team or separate squad but comprised of players in the academy, young pros, and senior players in need of game time. Sam, “It helped me prepare so when I did go over to the first team, I wasn’t shocked by it.” Adding, “That will help me get used to that environment of at least one step up. Hopefully, I can push on with the first team as well.”

Relationships

Teammate support. Specifically, for Sam, the first-year pros who were his teammates in the U18 squad the previous year were a source of support. “It’s quite helpful if they tell you what they did and what happened. See what they do around the training ground. They have been there a year, so they know what’s going on.”

Coach support. Sam, “I think the coaches are the main support you can get from the first team.” He also discussed the differences between academy coaches, “I think the academy coaches always try to look after you and see your best interests at heart,” whereas with the first team coach, “It doesn’t really matter what he thinks about you, he isn’t really going to care about how you feel, he just wants you to do the right job.” Adding, “It’s challenging because you don’t have that trust with them. You don’t know if you can speak to them about anything.”

Power dynamics

Trust, and the power dynamic between players and coaches, was a major complication to receiving support from coaching staff who were in charge of determining playing time and held influence over contract decisions. Ryan, “It is tough because you have to find different support in a way somewhere else, if that’s a teammate or something like that. That’s not ideal, it is tough.”

You don’t want it to help them jeopardize your role. If you say I’m not enjoying it and I don’t think I can give 100% right now or I don’t feel I’m playing my best. That might affect you, he might have a thought about not playing you. You don’t want to give anything that might make him hesitate to choose you. (Sam)

Contracts and motivation

In this phase, two higher-order themes were linked to the overall experience. Earning a long-term contract early while in the academy created a motivational challenge. Ryan, “It’s so easy to sit back. This is probably the easiest stage to waste this year.” Sam agreed.

It can be easy to sit off this season and not improve much because there is no pressure on me, other than to just try to play as many games as high as I can. I just have to try to flip that on its head and think what can I do now? How can I get ready for next year?

Dual career

Football was their primary focus, but they were also completing their education. Sam, “You still have your college stuff sorted and have the grades. Even though I probably could have done A-Levels. It won’t stop me from going back and doing Uni.”

I already have my B plan prepared. I know what I want to do. I know I always have something to fall back on. If you don’t have something to fall back on, you are putting so much pressure on football. (Ryan)

Orientation phase

This phase began when players ended their two-year U18 scholarship and joined the first team full-time. Players learned about the new environment and adjusted to its demands. Ryan predicted what was to come when he made this move. “Next year will be one of the harder years. That’s when you have to almost start my life again and go figure things out.” Although Jake reflected, “I’d say the transition probably took the whole season. I remember coming back the second year and thinking yeah, ok, I know what it’s about now. I’m ready.”

Opportunity

Playing time. Moving into the first team came with the realization you were at the back of the line for playing time.

The frustration of the lack of opportunity or the realization that you are not there yet. Getting the contract, you might think, ok I’m really close. Then you get in first week of preseason and there are four players ahead of you in your position and you think, well, I’m nowhere near it. (Tyler)

Training opportunity. Not only did the young pros not receive playing time early on, they were also left on the fringes of first team training.

You are only training with the first team group a few times a week. You are less prepared for that and sometimes you are feeling like you have the pressure on you then. You think the manager hasn’t seen me train in a week and a half. You are thinking about everything that you do in front of him. (Tyler)

Organizational strategy

U23 group/loan moves. With playing time unavailable and the main focus on the match day squad, two outlets for their efforts were available: U23 group and loan moves. Jake didn’t have this experience, but believed it was an important change. “Now they have the sessions for the U23s. They can have those sessions where they feel it’s all about them. That’s a positive for them.” Lewis confirmed this, “(The U23 coach) can feed information and knowledge to us that has come from the manager. He can say ‘this is what he is after.’ Then in our sessions we can then work on that. That has been positive.” At the same time players were sent on loan to gain experience and playing time.

It’s quite helpful when you go out on loan. Even if you think the level is lower than the first team, you are still put in the same situations on the pitch and you are making the same decisions in a real pressured environment instead of on the training pitch. (Tyler)

Not only did it help their development, but the playing time gave a sense of normalcy to the week. Tyler, “If I hadn’t been playing games at the weekend it would have been more difficult, I would have struggled more. At least you have that at the end of the week, you have a game to look forward to.”

Relationships

Coach support. The change in coach relationships was noted by the players in this phase. Lewis, “it’s just a professional relationship. The only time we see each other and the only thing we talk about is football.” Tyler, “It seems very businesslike,” adding, “it doesn’t really seem as though they are taking an interest in what you are doing outside of turning up and training. All they care about is what you do in that hour and a half session.” One potential consequence of this perception was a reduced willingness to seek support.

I remember being a young lad, 18 or 19, and going into the manager, you didn’t really do that as a young person because you didn’t really have the right. You probably did, but you don’t feel that you do so you often don’t do that. (Daniel)

Power dynamics

Similar to the preparation phase there was a strong feeling that support, particularly from the coaching staff, was not entirely possible.

They decide the team, they decide if you earn a contract at the end of the year. There are certain things you don’t want them to know. There are things that you feel if they did know, may affect your opportunities. (Lewis)

Anything you say to a coach, because they aren’t only trying to help you improve, they are also making a decision on you as to whether you are ready or going to play. You are always going to think, what are they going to take from that? Not just how they can help you with it, but they are also going to think something else which might be this person doesn’t have the right attributes. (Tyler)

Contracts

The contracts for Sam and Ryan in the preparation phase were long term contracts, however that was not the case for Lewis and Tyler. Having short term contracts appeared to limit their focus on long-term development. Lewis, “I’ve not really thought of anything longer than (a few months) because I can think about that as much as I want but ultimately, I’ve got to get it right now.” Tyler agreed.

It’s just a year period you are constantly thinking about whether I am going to get the next one. Whether I am going to get anything afterwards. You spend more time worrying about that than on thinking about actually what is best for me in the long run.

He continued, “the fact that the contracts are yearly it misleads you to think that you have a year to break in or a year to impress.”

It’s hard to judge whether you are at the right point. Whereas if it is a two- or three-year contract you can say to yourself by the end of this I need to be in the first team or it’s not worth me doing. (Tyler)

Dual career

For Tyler this was a part of his education choices during the scholarship, “I have my education to fall back on and maybe go down another route.” Due to the short-term contracts, he had yet to continue his education.

With the uncertainty of the contract and whether I am going to be here next year. I think if I wasn’t here, I would probably go to Uni. I don’t want to be halfway through an Open University course and then think I’d like to go do this full time.

Gray period

Reflected in the data was a separate phase that developed due to a prolonged lack of opportunity in the first team. Players had progressed past the orientation phase and were not yet adapting to the context of the first team. This phase was marked by the absence of a clear goal, apart from simply improving as a player. Previously, players had a goal of earning a pro contract and later of breaking into the first team, however during this phase there was no clear path into the first team for the foreseeable future, leaving them in this “gray period.”

Opportunity

Playing time. Playing time was not readily available early in their careers (i.e., orientation phase) and for Daniel in particular this continued for several years. Jake, in his time at the club, had seen this affect teammates.

I have seen a lot of players lose their heads at the fact that they come in and they don’t play football for 6 months, 12 months. That’s just part and parcel of the game and probably one of the hardest things.

Daniel agreed. “You think when you turn pro that all of a sudden you are going to play every single game, it’s not like that at all, it’s really difficult.”

I thought coming through the academy and the scholarship I would be playing when I was 17, 18, 19 and it has taken me to when I was 21 to start really featuring and even now, I’m still not an out and out starter or of that pedigree. (Daniel)

Training opportunity. A further challenge in this phase was the continued lack of opportunity in first team training with the focus on those playing in the first team to play the next match. Jake had seen this throughout his time in the first team. “They don’t get much attention. It’s all about what the first team is doing.”

There are times when the manager just wants to work on something for Saturday so it’s just—stand there and feed balls or stand there on the sideline and I’ll bring you on for 20 or 30 minutes. Then they are stood their freezing cold for 20 minutes not doing anything and then expected to come on and perform. Then when you don’t—it’s well, that’s why you aren’t playing.

Over time this created obstacles to Tyler’s motivation:

You will improve with putting everything into the session and doing everything you have to, but you know that’s not going to change the fact that you aren’t playing. I would say there are points in this season where I have just got through sessions.

Jake recalled a similar experience:

You sometimes find yourself just getting through. In particular when there is no goal to aim towards. You are just getting by and getting through a session. There were mornings when I woke up when I was younger and just thought, I don’t want to go in today. I do not want to go in today. I’m just going to get abuse or there isn’t going to be anything there for me. It’s going to be rubbish, I don’t want to go in. I know for a fact there are youngsters now feeling the exact same thing. It’s hard, it’s very hard.

Organizational strategy

Loan moves. During this phase players were still on loan, however, the loans did not always yield positive experiences. Daniel, “I thought it was going to be a bit better than it was. I really wasn’t enjoying it and I wasn’t really playing. I couldn’t really cope with not being picked to play.”

Jake, both from his own experience and watching other young players, summarized the combination of lack of opportunity and the challenges of life on loan.

You come in as a first-year pro and you aren’t playing. You are chucked out to some crap club and getting booted left, right and center. You can’t play football, it’s getting shelled and you get blokes trying to kick you, calling you every name under the sun. You are thinking Jesus Christ this is a shock. Not just that but you are sat there week in and week out thinking well I know I’m not going to play for the first team on the weekend, this is crap.

Adaptation phase

Following the period marked by continued lack of opportunity (or having skipped that period altogether [Jake]) players fought for a place in the first team match day squad. Daniel was in this phase and had spent the two previous years without opportunity in the first team. Jake had previously been through this phase at different points in his career before establishing himself as a first team regular.

Organizational strategy

Loan moves. Daniel discussed his post loan period.

Coming back (from loan), he didn’t want me to go out on loan again. I had come back and I’m not playing again. I asked, do you want me to go out on loan again? He said no, you are too close.

He continued, “I was a bit stuck in the middle.”

I was thinking if he doesn’t want me to go that must be a good thing. At the same time, I was thinking that’s another week without a game or another week traveling and not even being on the bench, not playing again. It was a tough time, but also at the same time it wasn’t the worst time.

Opportunity

Playing time. After that period of limited opportunity, it was important for Daniel to gain confidence in reserve fixtures and prove readiness for the first team. “I was doing better in reserve games, U23 games and I was really stamping my authority down.” During this period his opportunity came, “making a few appearances was an achievement, a big thing for me to be involved on a Saturday on the bench or occasionally coming on.” This changed his experience. “You feel almost happy that you are involved. You are with the team and you feel more a part of it compared with the early years where you aren’t with it at all.” Jake described a similar change after he featured for the first team.

I had the confidence that I could take a (shouting at) if I got it wrong, because I had been on the pitch and done it. Shown to everyone that I am good enough and shown to myself that I’m good enough to play.

Relationships

Coach support. Returning from loan, and even previously, gaining information about your progress was important but required the player to take action. Daniel, “You have to become a man and speak to people.” “You have to show them that you are interested and that you care about your career.”

I remember around 20, I would start going in more and more to discuss things. I felt so much better for doing it. I had more of a clear, more often than not, I had much clearer head about what I had to do. (Daniel)

Power dynamics

Later in their careers Daniel and Jake gave examples of how they sought support. In both instances they turned to psychologists knowing that those conversations would be kept confidential and not shared with stakeholders at the club. Daniel, “I honestly just think it’s people you can trust to talk to. That would be someone like (a psychologist), being completely in confidence. You know they aren’t going to say anything.”

I spoke to (psychologist) about it rather than just trying to figure it out myself or just keep it in my head and deal with it. I had a little bit of help with it and it was good after that. (Jake)

Contracts

The older players had a different experience with contracts as they had earned several new contracts in their career. Daniel, “The older you get the more money you want to earn and the more comfortable you want to be. You want to be able to do things that you wouldn’t be able to do a couple years ago.”

Dual career

Senior players, perhaps being more settled, began university courses to advance their careers outside of football.

I’m doing a degree at the moment through The Open University. I started that three years ago. It’s probably one of the best things that I’ve done. I love football but coming back from training I don’t want to think about football. (Daniel)

Stabilization phase

Following the battle for places in the first team a player settles into the squad, becoming a regular player. In this case only Jake reached this phase in the previous season. Here he dealt with no longer having competition for places and his ambition to move to a higher level.

Motivation

One key challenge in this phase was maintaining motivation now that Jake was assured a place in the team. “As much as you say you want goals from other people and you need that, you also have to be able to set your own goals and push yourself along.” “I don’t mean to but there are days when I have a bad session and I think it doesn’t really matter because I’m playing. I get annoyed because I don’t want that mindset.” His ambition to play in higher leagues became his motivation.

It’s then a battle with yourself to keep pushing yourself every day. Even though you are pretty sure you are going to play on a Saturday you have to push yourself to do better anyway. Because for me it’s not just doing well on a Saturday, it’s then to get to the next level, ready to step up.

Power dynamics

Even in the late phases, and throughout his journey, Jake believed support was hard to come by within the club.

You are always thinking I can’t go now and say, I’m struggling with this and that or whatever. That could be used against you for contracts. You don’t want to go and look weak or like you are struggling. They could see that as a weakness and a reason to get rid of you. (Jake)

Contracts

Having earned several new contracts Jake felt he was now at an important point in his career.

You are here until you are 24 unless you are absolutely flying, and someone is going to pay a couple million for you. It is quite hard because you don’t get that same respect. I think that’s a big thing when you are a youth team player coming through you don’t get the same respect as another and that’s hard to take.

Dual career

Much like Daniel, Jake believed it was important to continue his education.

I’m doing a degree alongside things. I decided to take that up when I got injured. I thought at the end of the year that if I get an injury like that and I can’t come back, I have to have something to fall back on. I did quite well and switched on in school, I thought I would do something like that. I have that off the pitch as a bit of a switch off. That’s my switch off I would say doing that. (Jake)

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the junior-to-senior transition from professional contract to an established first-team player. The selection of participants throughout the transition allowed for creating a general picture of the entire transition process. Furthermore, it allowed major checkpoints to be mapped based on the players’ experience (see ). The first checkpoint was earning a professional contract and followed by the full-time move to the first team upon finishing their U18 scholarship. For Sam, Ryan, and Daniel, the full-time move would come roughly 18 months after their contract decision, although Lewis, Tyler, and Jake received contracts following completion of their U18 scholarship. A large gap then appeared as the next central point was earning a spot in the first-team squad. This checkpoint had not been reached by Sam, Ryan, Lewis, or Tyler. In Daniel’s experience, this took three full seasons. Jake, however, was in the first-team squad in his first season, yet his journey was far from over as he was then in and out of the squad throughout his second season and injured for his third season. The final checkpoint, establishing yourself in the starting XI as a first-team regular, was only achieved by Jake in his fifth season.

Figure 1. Visual representation of higher order themes, checkpoints, and Stambulova et al. (Citation2017) phases.

Four unique contributions to the literature are discussed: the central role of opportunity in career progression; the presence of a “gray period”; difficulties in seeking support from coaches; and contracts' influence across the transition. The first significant finding was the central role of opportunity in the progression of the transition. Previous researchers (Pehrson et al., Citation2017; Stambulova et al., Citation2017) suggested four phases that players progressed through during the junior-to-senior transition. Our study did show evidence of the four phases mentioned; preparation, orientation, adaptation, and stabilization, however rather than timeframes as the primary indicator of the length of the phases, our data suggested opportunity in the first team as the main indicator of progression. Moving from preparation to the orientation phase was the only natural progression without the necessity of opportunity. Afterward, all four players who had made it to this point agreed there was an adjustment period in the first season, as Jake specifically discussed (cf. Pehrson et al., Citation2017).

Following this period, Daniel and Jake both dealt with long periods outside the first team. Pehrson et al. (2017) suggested the potential for a non-linear path where players move back and forth through the phases and mentioned playing time as a crucial development opportunity. Yet, they did not discuss how the absence of playing time could challenge a transition's success (cf. Mitchell et al., Citation2020). Our participants’ experiences suggested that once you graduate from one phase you do not return to the previous phase again, but rather you are somewhat stuck ‘out of phase.’ For example, once a player orientated to the first team, they would not return to reorientate should they not be progressing in the transition. At the end of their first year and contracted for half of the next season, Lewis and Tyler were aware they would again be on loan and without first-team opportunity. They would not reenter the orientation phase nor progress to adapting to the first team, instead they enter a gray period without specific goals. Equally, it can be hypothesized that early, consistent opportunity in the first team could eliminate phases of the transition all together. Furthermore, as evidenced by Jake’s story, a player might progress through all phases, only to have opportunity removed due to injury or being replaced by a new player and therefore be out of phase.

The second major finding is the presence of a gray period, defined as a period without a clear short-midterm goal. There were two clear goals in the players’ careers: first, earn a pro contract, and then to play for the first team. As our players’ experiences reveal, it was expected that playing for the first team was rare in the first few years, and without that playing time, the broad experience changed. For example, Daniel spent two seasons on loan before returning to remain without opportunity in his third season. This long period without opportunity created challenges to motivation and confidence without the typical reward of playing matches for the main squad as detailed in his experience (and that by Tyler and Lewis). Such challenges have been seen as barriers to transitions without early success (Drew et al., Citation2019; Swainston et al., Citation2020); however, no researchers have discussed how these challenges evolve with continued lack of progression. One potential reason for the uniqueness of the gray period finding is the lack of longitudinal research or the retrospective nature of research investigating transitions that were either successful or unsuccessful. Furthermore, using participants just at the start of the journey (on contract award e.g., Morris, Tod, & Eubank, Citation2016) limits the opportunity to explore the challenges that develop after the initial honeymoon period.

The next major finding was the role of organizational and coach support. Past research has suggested the importance of support from key stakeholders (e.g., Morris et al., Citation2015; Morris, Tod, & Eubank, Citation2016). Morris, Tod, et al. (Citation2016) also suggested that coaching staff’s emotional support was not always an option due to their role in selecting squads. Our evidence suggests similar difficulties in accessing support from coaching staff. In particular, there was a view from the players that seeking help could hurt their opportunities. Gaining opportunity was the single most crucial element of their career, and it appears to be the driving force behind their unwillingness to seek support from the coaching staff. All participants in all phases agreed that showing weakness could limit opportunity, playing time, or be used against them in deciding contracts. Sam and Ryan, yet to join the first team, presumed that moving to the first team would come with less access to support, although Lewis and Tyler discussed a change in the nature of the relationships with coaches. As a young player, Daniel believed he did not have the right to seek support from first-team staff. Both Daniel and Jake thought maturity was necessary for the willingness to seek support, but again they did so from resources they felt they could trust, giving examples from outside the club.

The final major finding was how contracts influenced the overall transition. In football, having a contract and renewing your contract was the only way to continue your transition. Early contracts allowed for a preparation period (cf. Morris et al., Citation2015; Swainston et al., Citation2020), as seen in Sam and Ryan’s experience. Lewis and Tyler, who were on short-term contracts during the gray period, struggled to manage long term development goals while also maximizing performance in the short term that was perceived as necessary in earning their next contract. In some instances, this meant actively choosing short term priorities despite knowing they should be taking a long-term approach. In the latter phases, maximizing financial gains became a priority alongside ambition to move to higher leagues.

Applied implications

The detailed picture of the transition from professional contract to first-team regular illuminates several applied implications. In professional football, clubs serve as the gatekeeper for the opportunity, and key stakeholders are charged with managing transitions effectively to get the most value from each player. As playing time is a critical factor of the transition, managing the club’s overall scope to ensure there are routes into the first team is paramount to a transition’s success (see Swainston et al., Citation2020). Without opportunity, several challenges developed that need to be managed by key stakeholders. Individual plans for each player can help players provide clear purpose as they await their opportunity while furthering their development. Effective communication from the club to the player can clarify this purpose and potentially eliminate some worry during the suggested gray period.

From the beginning of the transition, early pro contracts allowed for a specific preparation period (see Morris et al., Citation2015). Away from the typical stress of earning a contract (see Swainston et al., Citation2020), these players were afforded opportunities to train up with the U23 group and first team. As the transition continued, short-term contracts became a source of stress, and for Lewis and Tyler, long-term development was sacrificed in the battle to earn a new contract. This brings forward another challenge for clubs in how they manage contracts during the transition. Where possible, long-term contracts might provide security and allow for a more explicit focus on development toward the first team, although this is primarily a balance between financial resources and player development strategy. In this context, it appeared the club was trying this strategy with the youngest players, Sam and Ryan, by offering two years plus one additional year option contracts to allow them to develop over time without the pressure of earning a new contract during the gray period. Again, communication can be seen as an important message in order to help players understand where they are in the transition despite their contract situation.

There is no doubt that this transition is complex, with many challenges for organizations. On the personal level, holistic care should be seen as a priority in the first team environment. Providing ample emotional support could be improved by developing the coach-athlete relationship in order to help ease the power dynamics at play. Training in motivational interviewing, for example, could be an appropriate intervention to target relationship building and communication (Mack et al., Citation2021). Although this would be a positive step, further avenues and layers of support should be available away from those stakeholders. Specifically, as evidenced in this study, players desired psychological support (cf. Swainston et al., Citation2020). Although not every club will have access to a full-time psychologist, external relationships could be built to help signpost athletes to where they could find this type of support.

As discussed in the recent meta-study (Drew et al., Citation2019), players’ well-being needs to be considered one of the critical outcomes of a successful transition, not just matchday minutes. The current study’s findings echo these suggestions that clubs should provide support structures, internally and externally, that allow players to express themselves in a safe space in order to enhance their well-being. Indeed, there has been much interest in how sporting organizations can find balance in chasing performance targets while managing the well-being of their players (e.g., Ringland, Citation2016). For example, performance outcomes such as gaining playing time in the senior squad could be seen as success, which might mask individual well-being concerns (Ringland, Citation2016). Our data suggests that protecting opportunity appeared to be a priority over seeking support which over time might lead to well-being concerns. An awareness of individual well-being, as well as specific stakeholders focused on player well-being, should be seen as a priority regardless of perceived success in transition.

Not only is holistic support necessary in the gray period, but the current study illuminates the importance of an outlet for players’ efforts. In this study, this outlet was via loan moves (playing time) or the U23 group (development opportunities). These were key experiences for players to maintain the normalcy of having a weekly game to prepare for, and opportunities to further develop their skills during the gray period. Clubs should be aware of how limited opportunity in the first team might influence player experience and plan how they will keep that player motivated to continue their longer-term development. Although these were the two ways this was done in the current study, the balance between loans and time at the home club should be discussed with an awareness of individual player experience.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

The current study sought to further our understanding of the junior-to-senior transition, while reducing the reliance on a one-off, retrospective interviews. Multiple interviews with participants in the transition provided a richer data set, allowed participants to revisit areas of importance to them, and fostered an enhanced researcher-participant relationship (Jones & Harwood, Citation2008). Participants who were in the midst of their transition, at differing time points allowed for a broad, yet detailed picture of how the transition developed over time.

The cross-sectional approach can be seen as a limitation, and future research could seek to follow participants over the suggested four- to five-year transition period. However, there are significant funding challenges to such work. Additionally, researchers should look to focus on the experiences in delayed transitions and in the suggested gray period. It seems apparent that a number of difficulties develop with prolonged periods without opportunity, and based on the current data, this might be the norm in professional football. Exploring later phases of transition would shed light on these challenges as well as how clubs can better monitor and support players during this period.

Conclusion

The current study explored the junior-to-senior transition from professional contract to established first-team player. Different from previous models was the central role of opportunity in the progression of the experience rather than a chronologically focused pathway. Once past the initial move to the first team came an extended “gray period” where motivation was difficult to maintain without opportunity and without clear goals. To complicate matters, a lack of support was noted, with players hesitant to seek support from key stakeholders at the club in case it jeopardized opportunity. Later in the transition, players gained opportunity which normalized the overall experience, at which point ambition to play at a higher level and gain financial security influenced contract discussions. From an applied perspective, football clubs could improve how they manage the human elements of the transitions; including improved communication and access to support systems as well as providing players with an outlet for their effort.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data and Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1934914 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1212328. To obtain the author’s disclosure form, please contact the Editor.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (51.5 KB)References

- Bradshaw, C., Atkinson, S., & Doody, O. (2017). Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 4, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393617742282

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Drew, K., Morris, R., Tod, D., & Eubank, M. (2019). A meta-study of qualitative research on the junior-to-senior transition in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 45, 101556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101556

- Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP). (2010). Premier league youth development. Retrieved from http://premierleague.com/youth/EPPP

- Jones, M. I., & Harwood, C. (2008). Psychological momentum within competitive soccer: Players’ perspectives. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200701784841

- Lawrence, J. (2019, March 4). Premier league: Why are young UK football players moving abroad. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/47388643

- Mack, R., Breckon, J., Butt, J., & Maynard, I. (2021). Practitioners’ use of motivational interviewing in sport: A qualitative enquiry. The Sport Psychologist, 35(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2019-0155

- Mayan, M. J. (2009). Essentials of Qualitative Inquiry. Left Coast Press.

- Mitchell, T., Gledhill, A., Nesti, M., Richardson, D., & Littlewood, M. (2020). Practitioner perspectives on the barriers associated with youth-to-senior transition in elite youth soccer academy players. International Sport Coaching Journal, 7(3), 273–282. https://doi.org/10/1123/iscj.2019-0015

- Morgan, T. (2019, Dec 3). Gareth Southgate criticizes all time low number of English players starting in Premier League. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/football/2018/12/03/gareth-southgate-criticises-all-time-low-number-english-players/

- Morris, R., Tod, D., & Eubank, M. (2016). From youth team to first team: An investigation into the transition experiences of young professional athletes in soccer. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(5), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1152992

- Morris, R., Tod, D., & Oliver, E. (2015). An analysis of organizational structure and transition outcomes in the youth-to-senior professional soccer transition. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 27(2), 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2014.980015

- Morris, R., Tod, D., & Oliver, E. (2016). An investigation into Stakeholders’ perceptions of the youth-to-senior transition in professional soccer in the United Kingdom. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(4), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2016.1162222

- Morse, J. (2020). The changing face of qualitative inquiry. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940692090993–160940692090997. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920909938

- Neergaard, M. A., Olesen, F., Andersen, R. S., & Sondergaard, J. (2009). Qualitative description – The poor cousin of health researcher? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-52

- Pehrson, S., Stambulova, N. B., & Olsson, K. (2017). Revisiting the empirical model ‘Phases in the junior-to-senior transition of Swedish ice hockey players’: External validation through focus groups and interviews. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(6), 747–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117738897

- Pummell, E. K. L., & Lavallee, D. (2019). Preparing UK tennis academy players for the junior-to-senior transition: Development, implementation, and evaluation of an intervention program. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 40, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.07.007

- Relvas, H., Littlewood, M., Nesti, M., Gilbourne, D., & Richardson, D. (2010). Organizational structures and working practices in elite European professional football clubs: Understanding the relationship between youth and professional domains. European Sport Management Quarterly, 10(2), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740903559891

- Ringland, A. (2016). Commentary: The experience of depression during the careers of elite male athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1869. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01869

- Røynesdal, Ø., Toering, T., & Gustafsson, H. (2018). Understanding players’ transition from youth to senior professional football environments: A coach perspective. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117746497

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

- Sandelowski, M. (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20362

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Stambulova, N. (2003). Symptoms of a crisis transition: A grounded theory study. In N. Hassmen (Ed.), Svensk Idrottspsykologisk Förening (pp. 97–109). University Press.

- Stambulova, N., Alfermann, D., Statler, T., & Côté, J. (2009). ISSP position stand: Career development and transitions of athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(4), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671916

- Stambulova, N., Pehrson, S., & Olsson, K. (2017). Phases in the junior-to-senior transition of Swedish ice hockey players: From a conceptual framework to an empirical model. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117694928

- Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Bova, C., & Harper, D. (2005). Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: The use of qualitative description. Nursing Outlook, 53(3), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.005

- Swainston, S. C., Wilson, M. R., & Jones, M. I. (2020). Player experience during the junior to senior transition in professional football: A longitudinal case study. Frontiers of Psychology, 11, 1672. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01672

- Tamminen, K. A., & Poucher, Z. A. (2018). Open science in sport and exercise psychology: Review of current approaches and considerations for qualitative inquiry. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 36, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.12.010

- Wylleman, P., & Lavallee, D. (2004). A developmental perspective on transitions faced by athletes. In M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 502–523). Fitness Information Technology.