Abstract

Both recreational and competitive cycling such as strenuous ultra-cycling have grown in popularity over the last decades. Still, the underlying psychological predictors and their interplay with mental health are unknown. We therefore examined the psychological determinants and health outcomes related to the cycling ambitions of 2,331 international cyclists ranging from commuters via leisure to competitive ultra-cyclists. First, groupwise analysis showed that social and external motives, cycling-induced pain affinity, sensation seeking, benign masochism, low neuroticism, openness, conscientiousness and prior mental health problems most clearly differed between the types of cyclists, with values increasing by level of ambition (commuting vs. leisure vs. competitive). Yet, even within groups, we observed a strong variation of ambition. To capture these nuances, we created a path model with cycling ambition as a latent variable based on five indicators (e.g, frequency of cycling, following a training plan). Path analysis confirmed that social and external motives were important determinants of cycling ambition, partly mediating the effects of masochism and sensation seeking. Furthermore, while partly driven by prior mental health problems, cycling ambition positively predicted current mental health, suggesting that cycling may be a safe way to challenge oneself and potentially serves as a strategy to overcome psychopathological episodes. Longitudinal and qualitative research could follow up on some of the causal relationships proposed in the present model, particularly with regard to ambitious cycling functioning as a potentially unconscious self-therapeutic behavior.

Lay summary: Cycling is currently more popular than ever. To understand who cycles for which reason and with which consequences, we surveyed cyclists of various ambitions ranging from commuting via leisure to competitive ultra-cycling about their pain affinity, benign masochism, sensation seeking, motives for cycling, and mental and physical health.

Introduction

Over the last decades, cycling has been growing in popularity, with the global bike sale market valued at approximately USD 60 billion in 2021, and bike sales expected to further increase by 8.2% annually over the next 8 years (Grand View Research, Citation2022). This increase is substantially driven by sales of bikes intended for athletic activities such as road and mountain biking. In particular, ultra-cycling, defined as cycling distances of at least 500 km (310 miles) with a minimum daily distance of 150 km (93 miles) (Gauckler et al., Citation2021), recently became more popular (Scholz et al., Citation2021), reflecting a general trend toward extreme endurance sports in the last decades (Abou Shoak et al., Citation2013; Scheer, Citation2019). Despite its global popularity, the psychological determinants of recreational and ambitious cycling and its impact on mental health remain to be fully elucidated. Yet, understanding why individuals cycle is important, because cycling, as both a particularly accessible sport (Garrard et al., Citation2012) and an outdoor sport (Abraham et al., Citation2010), offers notable potential to increase individual mental health (Leyland et al., Citation2019), even for those commuting only short distances (Hendriksen et al., Citation2010).

Cycling ambition varies greatly. In stark contrast to commuters are competitive cyclists, with various levels of leisure cyclists located in between these two extremes. In unsupported ultra-races, for example, individuals cycle a large distance completely on their own, such as 2,700 km (1,678 miles) from Vienna to Barcelona in the Three Peaks bike race, which individuals completed in six to twenty days in 2021. During such races, cyclists often report severe saddle sores, sleep deprivation and other pains, while at the same time most of all competitive riders do not earn a salary for their immense cycling efforts. This discrepancy between the potential health benefits on the one hand and the voluntary suffering in the more extreme spectra of cycling on the other hand led to the aim of the study to examine psychological determinants of a variety of cycling ambitions. What are the underlying motives for different cycling ambitions and do cyclists with extreme ambitions (e.g., cyclists participating in unsupported ultra-races or individuals cycling everyday) differ in their mental health across their lifespan from individuals with more average cycling habits?

While personality correlates of cyclists have not been researched to date, some studies have investigated the interplay between personality traits and physical activity in general. Meta-analyses identified the personality traits extraversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness, and openness to experience as minor correlates of physical activity (Rhodes & Smith, Citation2006; Wilson & Dishman, Citation2015). Meanwhile, specific traits such as sensation seeking, which is defined as a need for varied, new, and complex experiences and the willingness to accept risks to achieve these experiences (Zuckerman, Citation1974), have been more informative in understanding sports behavior (Rowland et al., Citation1986; Zuckerman, Citation1983). For example, sensation seeking is elevated in athletes compared to non-athletes (Schroth, Citation1995) and in high-risk compared to low-risk athletes (Jack & Ronan, Citation1998), and predicts participation in extreme sports (Weishaar et al., Citation2021).

A trait related to sensation seeking is benign masochism, which describes an affinity toward threat-simulating, challenging but effectively safe stimuli such as spicy food, roller coasters, and physical pain (Rozin et al., Citation2013; Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, Citation2020). Cycling generally involves less risk than adventure and typical extreme sports such as base jumping or free-solo climbing, but often results in various extents of painful bodily decline (Scheer & Hoffman, Citation2020). Accordingly, benign masochism and in particular pain affinity may explain additional facets of a psychological proneness to cycling and ultra-distance cycling.

More direct antecedents of behavior are explicit motives, which tend to mediate influences of personality on exercise behavior (Lewis & Sutton, Citation2011). Motives for ambitious leisure cycling are various, ranging from social, hedonic and health to self-presentation, achievement as well as coping (Brown et al., Citation2009; LaChausse, Citation2006). In turn, competitive endurance biking is mainly motivated by achievement motivation (LaChausse, Citation2006) and by an affinity to seek personal challenges (Getz & McConnell, Citation2014). While, for some, cycling may be a convenient mode of transportation with added health benefits, others may resort to more extreme forms of cycling to alleviate chronic or acute stress. Indeed, more intense exercises lead to higher disengagement from stressors than less intense exercises of the same duration (van Hooff et al., Citation2019). Given these beneficial coping effects of intense exercising, it is conceivable that particularly excessive cycling could, in part, be driven by prior mental health issues while at the same time leading to improvements in current mental health.

Following an exploratory approach based on the outlined literature, the aim of this study was to examine different psychological determinants of cycling ambition and to tentatively identify potential mental health outcomes associated with this. Taken together, we combine common psychological predictors of exercising in one model to compare their relation to cycling ambition, and explore the mental and physical health outcomes of varying degrees of cycling, from occasional commuting to competitive ultra-cycling. To do so, we surveyed cyclists with varying ambitions about their personality traits, motives and mental health.

Method

This study was pre-registered [https://aspredicted.org/9xr2u.pdf] and approved by the local institutional ethics committee. The original questionnaires, the raw data and supplementary online materials can be accessed via this link [https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/R58EC]. This survey study was conducted online, using the platform unipark (https://ww3.unipark.de/). We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations and all measures in the study. Statistical analyses are described at the end of this section.

Participants and procedure

We collected a convenience sample for a cross-sectional survey advertised as assessing the “motives and habits in cycling as well as aspects of […] personality and mental health” via social media (mostly cycling-specific Facebook groups, Instagram and Strava), and a cycling podcast (Jahnke, Citation2022). Over the course of seven weeks (December, 7th 2021 until January 24th, 2022), 2,366 participants completed the survey, of which 35 were excluded as planned because they recommended so at the end of the survey (“No, better not use my data.”). The resulting sample (N = 2,331; female = 634, male = 1,697; MAge = 40.08, SD = 11.51, range = 15–93 years) is described in detail in the supplementary materials (Table S1).

Nationalities, countries of living and job sectors

Our sample was very international. In total, 55 nationalities were mentioned (in case of multiple citizenship, all nationalities were counted), among which German (n = 1,022, 43%) and French (n = 613, 26%) were most common, followed by British (n = 116, 5%), Austrian (n = 99, 4%), Belgian (n = 98, 4%), Swiss (n = 70, 3%), Italian (n = 44, 2%), American (n = 44, 2%) and Dutch (n = 37, 2%). The countries of living only slightly differed, with Germany (n = 976, 41%), France (n = 595, 25%), Austria (n = 142, 6%), Belgium (n = 108, 5%), Switzerland (n = 101, 4%), Great Britain (n = 45, 2%), and the United States (n = 45, 2%) being the most frequent ones. Overall, participants lived in 59 countries at the time of the study.

The participants mentioned more than 27 job sectors. The most common job sectors were information and technology (n = 266, 13% of mentions), engineering and manufacturing (n = 249, 12%), public services and administration (n = 165, 8%), research, science, and pharmaceuticals (n = 154, 8%), as well as teaching and education (n = 98, 5%) and medicine (physicians; n = 86, 4%).

We created the survey in English (n = 536), German (n = 1,140), and French (n = 655). An overview of all scales including sample items and reliability coefficients is given in .

Table 1. Examined scales (in the order of presentation).

After providing informed consent and demographics, participants self-reported general personality traits based on the five-factor model (McCrae & John, Citation1992) by completing the Ten-Item-Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling et al., Citation2003). Thirty-seven items followed, which asked how much individuals liked specific commonly masochistic behaviors (e.g., spicy and bitter tasting food, physical exhaustion and pain; Rozin et al., Citation2013). Participants continued with the 8-item brief sensation seeking scale (Hoyle et al., Citation2002).

Subsequently, they responded to a variety of mental and physical health questions, which were adapted from the brief health information screening of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; WHO Citation2003). We additionally asked for the experience of critical life events (M = 1.23, SD = 1.28, median = 1, range = 0–4) and lifetime experience of a psychopathological episode (yes = 1,054, no = 1,277). Those who indicated to have experienced an episode (diagnosed or not) were asked to specify one or more classes and submit details such as when it occurred. The by far most frequently selected class was mood/affective disorders (e.g., depression; n = 632), followed by neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders; n = 170), and behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (e.g., anorexia nervosa; n = 122).

The survey continued with questions about different motives for cycling, which we adapted from Pelletier and colleagues (Citation2013). The component analysis using Oblimin rotation with Kaiser normalization resulted in a four-factor solution, which explained 61.36% of the total variance (see Table S2): external, well-being, social and health motives.

Afterwards, participants indicated their enjoyment of suffering when cycling (bike masochism) and the experience of several specific cycling-induced pains (yes/no). In case they indicated to have experienced a certain pain, they rated the extent to which they 1—avoided, 4—accepted to 7—enjoyed said pain. We included these measures as a domain-specific type of benign masochism.

Last, participants answered questions about their cycling habits (e.g., frequency of training, participation in races, adherence to a training plan, ultra-cycling experiences, tracking of yearly kilometers and meters of altitude by bike). At the end of the survey, they had the chance to comment on their answers and were asked whether their data were reliable (“Sometimes there can be issues while completing a survey that would make it better not to use the data. This could be language issues, distraction leading to random responding, etc. Do you think we should use your data?”).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using the software R (R Core Team, Citation2022) and SPSS Statistics (IBM, Citation2017; Version 25). Using SPSS, we first ran group-based analyses of cyclists with varying ambition to provide a clear overview of psychological differences depending on whether individuals solely commuted, used cycling for exercising, or cycled competitively. We examined differences in personality, motives, mental and physical health between these three groups via univariate analyses of variance with post-hoc Tukey HSD tests (Bonferroni-corrected alpha level = .001). For our dichotomous dependent variables (psychopathological episode and classes), we examined odds ratios (Fisher’s exact test). To capture further nuances of cycling ambition and compare predictor strength, we then designed a path model with cycling ambition as a latent variable, using the R package lavaan (Rosseel, Citation2012). A complete correlation table can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S3).

Results

Group-based analyses

At first, we created three groups of cyclists based on their level of ambition. We combined individuals who indicated to have competed in races and in ultra-cycling races or challenges as competitive cyclists (n = 899; males = 682 [76%], females = 217 [24%]). The remaining sample was divided into leisure cyclists (n = 1,318, males = 931 [71%], females = 387 [29%]), who did not compete in races but cycled for exercise, and commuting cyclists (n = 116; males = 85 [73%], females = 31 [27%]), who only commuted and did not additionally cycle for exercise. These groups did not differ in their mean age or educational attainment, but there were significantly more male cyclists among competitive cyclists than among leisure cyclists (p = .008). Moreover, competing cyclists reported a significantly higher median income than did leisure cyclists (p < .001) and commuters (p = .014). Leisure and commuting cyclists did not differ in their median income (p = .453). A total of 31 participants reported to participate in various types of indoor cycling, yet all of these individuals also participated in outdoor cycling. Therefore, an analysis of specifically indoor cyclists was not possible.

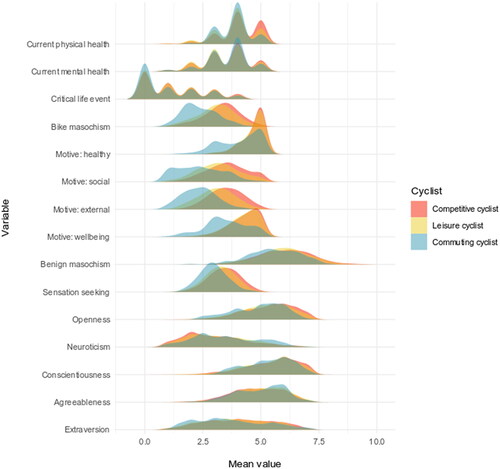

Next, we examined differences between the three groups. Commuters—individuals who use their bike as a mode of transportation and not particularly for exercising—clearly diverged from both competitive and leisure cyclists in their psychological profile (see , and supplementary Figure S4 and Table S5). Competitive and leisure cyclists had a more similar personality profile, but differed in sensation seeking, enjoyment of cycling-induced pain, and the strength of some of the motives. More specifically, competitive cyclists had the highest level of sensation seeking and bike masochism, followed by leisure and then commuting cyclists. Commuters were less benignly masochistic than both leisure and competitive cyclists, while the latter two did not differ significantly. Commuters scored lower in all four motives than the other groups did. Competitive and leisure cyclists differed in external and social motivation, which were higher for competitive cyclists. The three groups did not differ significantly in the number of critical life events or self-rated current mental and emotional health issues. Commuters were, however, less likely to have experienced a psychopathological episode (37/116, 32%) than were leisure cyclists (602/1,318, 46%), OR = 0.56, 95% CI [0.36, 0.85], p = .005, and competitive bikers (415/897, 46%), OR = 0.54, 95% CI [0.35, 0.83], p = .004. The probability of quoting any of the specific psychopathological classes did not differ significantly between cyclists. provides ridgeline density plots for an easy comparison of commuting, leisure and competitive cyclists based on their personality traits, motives and health.

Figure 1. Personality traits, motives and health for competitive, lesiure and communiting cyclists. Displayed is the distribution of Big Five personality traits, sensation seeking, masochism, motives for biking, bike masochism, past critical life events and self-reported current mental and physical health. Values are unstandardized values. For response scale information, see . For t-tests of the difference between groups, see .

Table 2. t-Test results for commuting, leisure and competitive cyclists.

Cycling-specific masochism

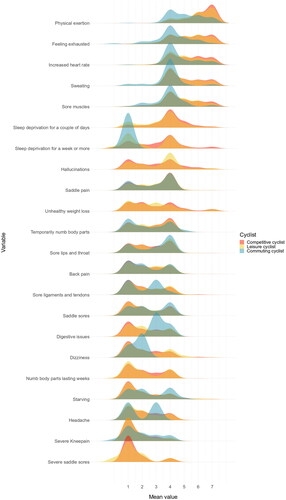

Competitive cyclists most strongly endorsed the notion that some pain and suffering is an essential and enjoyable part of cycling, followed by leisure and then commuting cyclists. Competitive cyclists experienced significantly more types of pain (M = 11.43, SD = 4.16) than did leisure cyclists (M = 8.99, SD = 3.62) and commuters (M = 5.47, SD = 2.84) (all p < .001). Indeed, commuters hardly experienced some of the more severe pains at all (see and Tables S2–S4). Yet, our sample also comprised a notable number of participants who reported experiencing some of the severe types of pain: 394 (17% of the total sample) participants reported numb fingers, toes, etc., with the symptoms lasting for several weeks, 155 (7%) participants reported experiencing hallucinations while cycling, and 27 participants (1%) reported saddle sores requiring surgery (see Table S3).

Figure 2. Enjoyment vs. acceptance vs. avoidance of specific pains by the different levels of cycling ambition. In case participants had indicated to have experienced one of these pains, they were subsequently asked to rate their enjoyment vs. acceptance vs. avoidance of said pain. The scale was labeled 1—avoid, 4—accept, 7—enjoy. Detailed descriptive statistics can be found in the supplementary Tables S6–S7.

We next examined the extent to which the specific pains were enjoyed (values > 4) or avoided (values < 4). In line with the definition of benign masochism, a number of pains were enjoyed rather than just accepted or avoided. All groups of cyclists enjoyed physical exertion, feeling exhausted and an increased heart rate, while leisure and competitive cyclists also enjoyed sweating and sore muscles, which commuters rather accepted. Yet, the groups differed in the extent to which they enjoyed these pains. For sweating, increased heart rate, and physical exertion, each group differed significantly from the other according to level of ambition (all p < .021). Sore muscles and feeling exhausted were enjoyed significantly less by commuters than by leisure and competitive cyclists (both p < .001). All other types of pain were avoided. Comparing leisure and competitive cyclists, short-term sleep deprivation was avoided more by leisure cyclists (p = .002). In summary, clear differences emerged for the enjoyable pains, while there was largely a consensus about the degree to which the more severe types of pain are avoided. shows in more detail which specific pains were enjoyed rather than accepted or even avoided by the different types of cyclists with different levels of ambition.

Path analysis

The above group-based analysis revealed notable differences in personality between differently ambitious cyclists. Yet, even within these groups, we observed strong variations in cycling ambition. For example, among competitive cyclists, about half (45%) competed in ultra-races while the rest did not, and more than half (56%) did not follow a structured training plan, 26% did so sometimes, and 18% did so always. Frequency of biking also varied largely with 8% reporting frequencies of once a week or less, and 9% reporting cycling daily. To capture all these nuances of ambitious cycling and to compare predictor strength, we created a path model predicting one latent variable, cycling ambition, based on five indicators: the group variable of commuting versus leisure versus competitive cyclists, whose unstandardized factor loading was fixed to 1, frequency of training, tracking of annual distance, training plan, and self-identification as an ultra-cyclist. All other variables were entered as manifest variables.

We created a mean score of masochism based on the standardized mean benign masochism and bike masochism scores. Third, we created a mean score of prior mental health issues based on the standardized scores of psychopathological episodes and number of critical life events. Following a causal logic, trait variables and prior mental health issues (which were largely experienced in the past) were seen as predictor variables, whereas outcome variables were operationalized as current states. As gender, age and income are likely to influence ambitious cycling, potentially via different motives, they were included as control variables of the motives and ambitious cycling. For example, cycling ambitiously requires a significant investment of time and money (thereby being potentially predicted by income and age), with men typically being represented more frequently than women (e.g., Aldred et al., Citation2016; Hatfield et al., Citation2015).

To identify the strongest predictors of cycling ambition when accounting for the covariance between them, we designed a mediational path model in which we regressed cycling ambition onto masochism, sensation seeking, general personality traits, prior mental health issues, motives, sex, age and income (see ). We treated the four motives external, social, well-being and health as mediators and regressed them onto sensation seeking, masochism, prior mental health issues, general personality traits, sex, age and income, and calculated indirect effects of sensation seeking, masochism, mental health and general personality traits via the motives on cycling ambition (for complete model statistics see Tables S9 and S10). Finally, we regressed current mental and emotional health on cycling ambition and prior mental health issues and regressed current physical health on cycling ambition (model fit: χ2 = 1135.77, df = 102, p < .001, CFI = 0.82, TLI = 0.70, RMSEA = 0.07, 90% CI [0.06, 0.07]; see Bollen & Long, Citation1993, for details on the different indices).

Figure 3. Path model of the psychological determinants and health outcomes of cycling ambition. Note. All values are standardized paths. Only significant paths relevant to the mediational analysis (p < .05) are displayed. Full path statistics are provided in Tables S9 and S10. Sex was coded 1 = female, 2 = male. Latent construct indicators were coded as follows: Cyclist [1 = Commuters, 2 = Leisure cyclists, 3 = Competing cyclist]; Training [Do you follow a training plan? 1 = no, 2 = sometimes, 3 = yes]; Tracking [Do you keep track of your yearly distance and elevation traveled by bike? 1 = yes, 2 = no—I do not keep track of my yearly distance and elevation, 3 = no—I just ride my bike for leisure, not as a particular exercise.]; Ultra-cyclist [1 = No, I don’t consider myself an ultra-cyclist., 2 = Yes, I consider myself an ultra-cyclist.]; Frequency [How often do you ride your bike as a sports activity (i.e., more than 30 minutes)? 1 = less than once a month, 2 = a few times per month, 3 = once a week, 4 = 2× per week, 5 = 3× per week, 6 = 4× per week, 7 = 5× per week, 8 = 6× per week, 9 = daily].

![Figure 3. Path model of the psychological determinants and health outcomes of cycling ambition. Note. All values are standardized paths. Only significant paths relevant to the mediational analysis (p < .05) are displayed. Full path statistics are provided in Tables S9 and S10. Sex was coded 1 = female, 2 = male. Latent construct indicators were coded as follows: Cyclist [1 = Commuters, 2 = Leisure cyclists, 3 = Competing cyclist]; Training [Do you follow a training plan? 1 = no, 2 = sometimes, 3 = yes]; Tracking [Do you keep track of your yearly distance and elevation traveled by bike? 1 = yes, 2 = no—I do not keep track of my yearly distance and elevation, 3 = no—I just ride my bike for leisure, not as a particular exercise.]; Ultra-cyclist [1 = No, I don’t consider myself an ultra-cyclist., 2 = Yes, I consider myself an ultra-cyclist.]; Frequency [How often do you ride your bike as a sports activity (i.e., more than 30 minutes)? 1 = less than once a month, 2 = a few times per month, 3 = once a week, 4 = 2× per week, 5 = 3× per week, 6 = 4× per week, 7 = 5× per week, 8 = 6× per week, 9 = daily].](/cms/asset/7f14a49c-6910-4d41-ad86-9e210b81dc2b/uasp_a_2166157_f0003_b.jpg)

Mediational path analysis

Confirming the notion that personality traits manifest in behavior via specific motives, the path model showed that external and social motivation were by far the strongest predictors of cycling ambition, while masochism, sensation seeking, general personality traits, prior mental health issues and some of the control variables also directly predicted cycling ambition, but the effects were much smaller. An overview of the significant indirect effects and the respective direct effects is given in . To test for significance of the indirect effect, we used the Monte Carlo method of obtaining an empirical sampling distribution of our estimated indirect effects (MacKinnon et al., Citation2004; Preacher & Selig, Citation2012). We simulated 1,000,000 draws. An effect is considered significant if the confidence interval does not include zero.

Table 3. Unstandardized direct and mediated effects of trait variables on cycling ambition.

Masochism, sensation seeking, and past mental health issues

Masochism predicted each motive, while sensation seeking predicted each motive but health, while only external and social motives predicted cycling ambition. The indirect effects of masochism via social motivation and via external motivation on cycling ambition were significant. Similar but smaller effects emerged for sensation seeking via social motivation and external motivation, respectively.

Past mental health issues significantly predicted well-being and health motivation, but none of the indirect effects were significant. The motives did thus not account for mental health issues leading to more ambitious cycling. Instead, mental health issues during the lifespan retained a direct effect on cycling ambition, suggesting that prior psychopathological problems lead people to cycle more ambitiously.

General personality traits

General personality traits in part retained direct influences on cycling ambition, but were also partially explained by external and social motivation. Neuroticism had only a direct, negative effect. The direct and indirect effects of the other variables diverged in direction, so we also examined the total effects.

Extraversion had a nonsignificant but negative direct effect on cycling ambition. The indirect effects of extraversion were significantly positive, but the positive indirect and negative direct effect canceled each other out, resulting in nonsignificant total effects (p > .505).

Openness had a positive direct effect on cycling ambition, but a negative indirect effect via external motives, suggesting that more open people are less externally motivated and thereby cycle less ambitiously. Yet, the total effect of openness on cycling ambition was positive (p = .022).

Agreeableness had a negative direct effect on cycling ambition. Agreeableness indirectly affected cycling ambition both positively and negatively. The more agreeable, the less individuals are externally motivated, and the lower their cycling ambition, but more agreeable individuals have higher social motivation and thereby also higher cycling ambition. Yet, both total effects were negative (ps < .001).

For conscientiousness, all effects were positive. The more conscientious, the more individuals are both socially and externally motivated, and the higher their cycling ambition is, resulting in significant positive total effects (ps < .001).

Ambitious cycling as a predictor for current mental and physical health

Finally, the effects of ambitious cycling on mental and physical health were examined. Cycling ambition significantly positively predicted current mental health while controlling for prior mental health issues (b = −0.27, p < .001) as well as physical health.

Sex, age and income

Biological sex significantly predicted a number of variables. Cycling ambition was higher for men than for women (see ), while women reported increased levels of health (b = −0.08, p < .001), well-being (b = −0.11, p < .001) and social motivation (b = −0.09, p < .001) than did men. Notably, external motivation did not differ between the sexes (p = .715), but this does not seem to translate into equally ambitious cycling.

Younger age correlated with external motivation (b = −0.01, p < .001) and reduced motivation by health reasons (b = 0.00, p = .049). Age did not predict any other variables in this model. Income emerged as a notable predictor of cycling ambition, but not of any of the motives except well-being (b = 0.02, p = .007). This suggests that the link between higher income and cycling ambition may simply reflect the availability of resources to engage in ambitious cycling rather than an underlying achievement motivation.

Discussion

Considering all nuances of cycling, a comprehensive list of psychological predictors was examined in a large sample of 2,331 cyclists with diverse ambitions, ranging from commuting to leisure and competitive cyclists. Notably, the sample was socio-demographically highly diverse—including nationalities and current residencies from more than 59 countries, ranging broadly in age, stages of education, employment, and salary levels, and representing more than 27 job sectors. This diversity notably increases the generalizability of our findings.

Path analysis showed that ambition in cycling is most strongly predicted by external motivations such as the enjoyment of achievement, followed by social motivations such as the involvement in a community. Regarding personality traits, especially masochistic tendencies predicted cycling ambition through both indirect (by increasing external and social motivation) and direct motivations. This suggests that mastering challenges is a critical motivation underlying benign masochism and that competitive cycling with its physical and mental suffering is one way to pursue this motive. Confirming this conclusion at group-level, leisure and especially competitive cyclists preferred aversive, intense stimuli and cycling-related pain more than commuters did. Cycling thus appears to be a safe and controllable way to challenge oneself. To a lesser extent, sensation seeking also predicted cycling ambition directly and indirectly by promoting social and external motives. Sensation seeking is conceptually linked to benign masochism, but more focused on emotionally thrilling and actually risky stimuli than is masochism. Cycling ambitiously thus seems to fulfill the need for intense, challenging stimuli slightly more than the need for risky thrills.

Confirming prior research on personality in athletes and marathon runners (e.g., García-Naveira & Ruiz-Barquín, Citation2013; Nikolaidis et al., Citation2018), conscientiousness positively and neuroticism negatively predicted cycling ambition, suggesting that more conscientious and more emotionally stable individuals tend to cycle more ambitiously. Yet, the effects of agreeableness, openness, and extraversion were mixed, with direct effects diverging from the indirect effects through external and social motivation. To further elucidate the role of general personality in cycling ambition, future research should employ more comprehensive measures (e.g., the NEO Five Factor Inventory) instead of a brief inventory such as the TIPI, which has notoriously low internal consistency scores (Gosling et al., Citation2003).

Similarly, the partly low reliabilities of the self-constructed scale of cycling motives warrants caution in the interpretation of these results and should be followed-up in future research. For example, the differences in motives in the groupwise analysis were quite striking for all four types of motives. In the path mode, external and social motives seemed to account for health and well-being motives. However, particularly these motives were assessed with only few items. Future research should thus more thoroughly investigate also health and well-being motives and reexamine whether their influence is indeed accounted for by external and social motives. Also, motivational scientists have pointed out that humans are often not aware of the reasons for why they do the things they do (e.g., Schultheiss, Citation2008), and that such implicit motives are better predictors of behavior over time than are explicit ones (e.g., McClelland et al., Citation1989; Schultheiss & Brunstein, Citation1999). The use of implicit measures for motives such as the picture story exercise (McClelland et al., Citation1989) or the Multi Motive Grid (Sokolowski et al., Citation2000) may thus be more diagnostic and reliable when trying to understand why individuals cycle.

Highlighting the health benefits of cycling, path analysis revealed positive effects of cycling ambition on current mental and physical health. While this finding did not emerge in the group-based analyses, there were differences concerning prior mental health issues in that leisure and competitive cyclists experienced more psychopathological episodes during their lifespan than commuters did. The fact that cycling ambition predicted higher levels of mental well-being despite previously elevated mental health problems suggests that cycling could serve as an effective self-therapeutic and coping strategy for overcoming psychopathological episodes. Yet, the cross-sectional nature of the survey does not allow for causal conclusions. A combination of longitudinal assessments and in-depth interviews could reveal insights into the precise role of intense exercising as a (potentially unconscious) psychological coping mechanism. The fact that well-being motivation, which included coping-related items, did not directly predict cycling ambition strongly suggests that—if indeed a coping mechanism—it manifests rather unconsciously.

Notably, the path model revealed that cycling ambition positively predicted current mental health—a relationship that was less evident in the group-based analyses. First, as reasoned above, prior mental health issues could cause individuals to cycle more, leading to improvements in mental health beyond the average. However, as the present study is based on cross-sectional self-reported survey data, we are unable to rule out that third variables contributed to this effect. For example, better physical health could enable people to cycle more ambitiously and also lead to improvements in mental health. Similarly, subjective socioeconomic status—a construct much more complex than the objective indicator of salary measured here (e.g., Tan et al., Citation2020)—could promote both mental health and cycling. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that some participants reported experiencing rather severe pain (e.g., week-long numbness of body parts and saddle wounds in need for surgery), suggesting that the relationship between health and cycling is not unambiguously positive, but might rather follow a u- or j-shaped dose response. Indeed, although still debated, extreme exercising could be linked to cardiovascular problems (Eijsvogels et al., Citation2018). From a psychological viewpoint, the positive effects of cycling ambition on mental health could then reflect the justification of a painful, addictive exercise behavior rather than actual improvements in mental health (cf. Scully et al., Citation1998). In summary, future research could follow up on the exact causal relationships and investigate the influence of potential confounding variables.

There are further limitations to note. For example, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought major changes in that more people are working from home more frequently (e.g., Eurostat, Citation2022). At the same time, many more individuals may have started commuting to work by bike, due to the higher infectious risk in public transportation (Cusack, Citation2021). While the exact impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of commuters in our cohort remains unclear, our final conclusions are likely not affected by this. Generally, it is difficult to precisely estimate the representativeness of our sample of cyclists. A selection bias may have led to an over-representation of competitive cyclists, as they are likely to be more willing to participate in a study on cycling that was promoted largely through cycling-related media channels. Furthermore, future research could, for example, explicitly assess the number of indoor cyclists. Although it is unlikely that there are many individuals who cycle exclusively indoors (this case did not appear at all in the present study), there may be individuals who do so mostly. Possibly, their motivations and mental health outcomes vary somewhat compared to indivduals combining cycling with being in outdoors and in nature.

With regard to the comparability of the present, cycling-specific results to other sports, a transfer to other outdoor endurance sports is conceivable. Our intention was to focus on cycling because it allowed us to study a natural control group of commuters who practice the mode of transportation in a similar frequency, but with less intensity and ambition. To some extent, the exercise of walking stretches along a similar continuum, from occasional strolling to ultra-mountain running, but given that many people commute to work by bike, cycling seemed the more apt exercise behavior to study. Still, future research could focus on transferability of the present results to the sport of running. Previous research comparing half, full and ultramarathoners came to the conclusion that higher ambitions went along with higher intrinsic, social and psychological motives, whereas physical determinants were more influential for less ambitious runners (e.g., health orientation and weight concern; Hanson et al., Citation2015). These results are, in general, consistent with our current results for cyclists.

In summary, the effects of the general personality traits of the Five Factor model and of the specific traits masochism and sensation seeking on cycling ambition were of similar magnitude. Yet, the indirect effects via social and external motivation suggest that masochism and sensation seeking are indeed more informative in understanding cycling ambition than are the general traits. At the same time, none of the personality traits had exceedingly large effects on cycling ambition. This is not surprising given that cycling—as pointed out above—is very accessible and thus unlikely to lead to a personality-based selection bias as strongly as other exercise behaviors such as extreme sports would. Instead, external and social motives were notable predictors of cycling. Need-based approaches thus appear to be more promising in understanding the psychological determinants of exercising than broad personality-based ones. Accordingly, previous research has shown that extreme endurance sports in particular can fulfill basic needs such as the need for competence (in achievement-motivated individuals) and the need for social relatedness (in affiliation-oriented individuals; Schüler et al., Citation2014). Generally speaking, personality traits seem to play a rather minor role in predicting specific behavior such as ambitious cycling (Roberts et al., Citation2007).

Conclusion

With regard to the consequences of cycling, one reason why cycling can be particularly beneficial for mental health could be the aerobic movement (Raglin, Citation1990) and the outdoor experience, both of which have found their way into psychotherapy (Cooley et al., Citation2020; Karg et al., Citation2020). As our results suggest, cycling can also be a safe way to challenge oneself, and cyclists seem to be motivated by a sense of accomplishment and social experience, which may be crucial aspects in coping with psychopathological episodes. As a very accessible and affordable sport that is easily practiced in natural environments, cycling seems a particularly effective way to maintain a physically and mentally healthy lifestyle, especially in light of month-long waiting times for psychotherapy (BPtK, Citation2021). Thus, further promotion of this recreational sport is warranted. At the same time, under some circumstances such self-therapeutic exercising could backfire and lead to addictive behavioral patterns (Scully et al., Citation1998). When faced with psychological issues, the consultation of mental health professionals seems always advisable.

References

- Abou Shoak, M., Knechtle, B., Knechtle, P., Rüst, C. A., Rosemann, T., & Lepers, R. (2013). Participation and performance trends in ultracycling. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 4, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S40142

- Abraham, A., Sommerhalder, K., & Abel, T. (2010). Landscape and well-being: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. International Journal of Public Health, 55(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0069-z

- Aldred, R., Woodcock, J., & Goodman, A. (2016). Does more cycling mean more diversity in cycling? Transport Reviews, 36(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1014451

- Bollen, K. A., & Long, J. S. (Eds.). (1993). Testing structural equation models (Vol. 154). Sage.

- BPtK. (2021). BPtK-Auswertung: Monatelange Wartezeiten bei Psychotherapeut*innen [BPtK assessment: month-long waiting time for psychotherapists]. https://www.bptk.de/bptk-auswertung-monatelange-wartezeiten-bei-psychotherapeutinnen/.

- Brown, T. D., O'Connor, J. P., & Barkatsas, A. N. (2009). Instrumentation and motivations for organised cycling: The development of the Cyclist Motivation Instrument (CMI). Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 8(2), 211–218.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

- Cooley, S. J., Jones, C. R., Kurtz, A., & Robertson, N. (2020). ‘Into the wild’: A meta-synthesis of talking therapy in natural outdoor spaces. Clinical Psychology Review, 77, 101841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101841

- Cusack, M. (2021). Individual, social, and environmental factors associated with active transportation commuting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Transport & Health, 22, 101089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2021.101089

- Eijsvogels, T. M., Thompson, P. D., & Franklin, B. A. (2018). The “extreme exercise hypothesis”: recent findings and cardiovascular health implications. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine, 20(10), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-018-0674-3

- Eurostat. (2022). EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Employment_-_annual_statistics.

- García-Naveira, A., & Ruiz-Barquín, R. (2013). The personality of the athlete: A theoretical review from the perspective of traits. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 13, 627–645.

- Garrard, J., Rissel, C., & Bauman, A. (2012). Health benefits of cycling. In J. Pucher & R. Buehler (Eds.), City cycling (pp. 31–55). MIT Press.

- Gauckler, P., Kesenheimer, J. S., Kronbichler, A., & Kolbinger, F. R. (2021). Edema-like symptoms are common in ultra-distance cyclists and driven by overdrinking, use of analgesics and female sex–A study of 919 athletes. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 18(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-021-00470-0

- Getz, D., & McConnell, A. (2014). Comparing trail runners and mountain bikers: Motivation, involvement, portfolios, and event-tourist careers. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 15(1), 69–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/15470148.2013.834807

- Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

- Grand View Research. (2022). Bicycle market size, share & trends analysis report by product (Mountain, Hybrid, Road, Cargo), by technology (Electric, Conventional), by end user, by distribution channel, by region, and segment forecasts, 2022–2030. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/bicycle-market

- Hanson, N., Madaras, L., Dicke, J., & Buckworth, J. (2015). Motivational differences between half, full and ultramarathoners. Journal of Sport Behavior, 38, 180–191.

- Hatfield, D. P., Chomitz, V. R., Chui, K. K., Sacheck, J. M., & Economos, C. D. (2015). Demographic, physiologic, and psychosocial correlates of physical activity in structured exercise and sports among low-income, overweight children. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 47(5), 452–458.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2015.05.008

- Hendriksen, I. J., Simons, M., Garre, F. G., & Hildebrandt, V. H. (2010). The association between commuter cycling and sickness absence. Preventive Medicine, 51(2), 132–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.05.007

- Hoyle, R. H., Stephenson, M. T., Palmgreen, P., Lorch, E. P., & Donohew, R. L. (2002). Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(3), 401–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00032-0

- IBM. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. IBM Corp.

- Jack, S. J., & Ronan, K. R. (1998). Sensation seeking among high-and low-risk sports participants. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(6), 1063–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00081-6

- Jahnke, J. [Host]. (2022, January). Special: Science Edition – Share Your Experience! [Audio Podcast]. In Die wundersame Fahrradwelt [the wondrous world of bicycles]. https://doi.org/https://die-wundersame-fahrradwelt.de/special-science-editionshare-your-experience/

- Karg, N., Dorscht, L., Kornhuber, J., & Luttenberger, K. (2020). Bouldering psychotherapy is more effective in the treatment of depression than physical exercise alone: Results of a multicentre randomised controlled intervention study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02518-y

- LaChausse, R. G. (2006). Motives of competitive and non-competitive cyclists. Journal of Sport Behavior, 29, 304.

- Lewis, M., & Sutton, A. (2011). Understanding exercise behavior: Examining the interaction of exercise motivation and personality in predicting exercise frequency. Journal of Sport Behavior, 34, 82.

- Leyland, L. A., Spencer, B., Beale, N., Jones, T., & Van Reekum, C. M. (2019). The effect of cycling on cognitive function and well-being in older adults. PLoS One, 14(2), e0211779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211779

- MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

- McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96(4), 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.690

- McCrae, R. R., & John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 175–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x

- Nikolaidis, P. T., Rosemann, T., & Knechtle, B. (2018). A brief review of personality in marathon runners: The role of sex, age and performance level. Sports, 6(3), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports6030099

- Pelletier, L. G., Rocchi, M. A., Vallerand, R. J., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Validation of the revised Sport Motivation Scale (SMS-II). Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.12.002

- Preacher, K. J., & Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.679848

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org.

- Raglin, J. S. (1990). Exercise and mental health. Sports Medicine, 9(6), 323–329. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199009060-00001

- Rhodes, R. E., & Smith, N. E. I. (2006). Personality correlates of physical activity: A review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(12), 958–965. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2006.028860

- Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science : a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 2(4), 313–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Rowland, G. L., Franken, R. E., & Harrison, K. (1986). Sensation seeking and participation in sporting activities. Journal of Sport Psychology, 8(3), 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.8.3.212

- Rozin, P., Guillot, L., Fincher, K., Rozin, A., & Tsukayama, E. (2013). Glad to be sad, and other examples of benign masochism. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500005295

- Sagioglou, C., & Greitemeyer, T. (2020). Common, nonsexual masochistic preferences are positively associated with antisocial personality traits. Journal of Personality, 88(4), 780–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12526

- Scheer, V. (2019). Participation trends of ultra endurance events. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 27(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSA.0000000000000198

- Scheer, V., & Hoffman, M. D. (2020). Ultramarathon and ultra-endurance sports. In M. Khodaee, A. Waterbrook, & M. Gammons (Eds.), Sports-related fractures, dislocations and trauma. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36790-9_75

- Scholz, H., Sousa, C. V., Baumgartner, S., Rosemann, T., & Knechtle, B. (2021). Changes in sex difference in time-limited ultra-cycling races from 6 hours to 24 hours. Medicina, 57(9), 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090923

- Schroth, M. L. (1995). A comparison of sensation seeking among different groups of athletes and nonathletes. Personality and Individual Differences, 18(2), 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)00144-H

- Schüler, J., Wegner, M., & Knechtle, B. (2014). Implicit motives and basic need satisfaction in extreme endurance sports. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 36(3), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2013-0191

- Schultheiss, O. C. (2008). Implicit motives. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 603–633). The Guilford Press.

- Schultheiss, O. C., & Brunstein, J. C. (1999). Goal imagery: Bridging the gap between implicit motives and explicit goals. Journal of Personality, 67(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00046

- Scully, D., Kremer, J., Meade, M. M., Graham, R., & Dudgeon, K. (1998). Physical exercise and psychological well-being: A critical review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 32(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.32.2.111

- Sokolowski, K., Schmalt, H. D., Langens, T. A., & Puca, R. M. (2000). Assessing achievement, affiliation, and power motives all at once: the Multi-Motive Grid (MMG). Journal of Personality Assessment, 74(1), 126–145. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA740109

- Tan, J. J., Kraus, M. W., Carpenter, N. C., & Adler, N. E. (2020). The association between objective and subjective socioeconomic status and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(11), 970–1020. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000258

- van Hooff, M. L., Benthem de Grave, R. M., & Geurts, S. A. (2019). No pain, no gain? Recovery and strenuousness of physical activity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(5), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000141

- Weishaar, M. G., Kentopp, S. D., Wallace, G. T., & Conner, B. T. (2021). An investigation of the effects of sensation seeking and impulsivity on extreme sport participation and injury using path analysis. Journal of American College Health, 9, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1942008

- WHO. (2003). ICF checklist: version 2.1a, clinician form for International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/classification/icf/icfchecklist.pdf

- Wilson, K. E., & Dishman, R. K. (2015). Personality and physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 72, 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.023

- Zuckerman, M. (1974). The sensation seeking motive. Progress in Experimental Personality Research, 7, 79–148.

- Zuckerman, M. (1983). Sensation seeking and sports. Personality and Individual Differences, 4(3), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(83)90150-2