ABSTRACT

Intersectionality has been gaining momentum among social workers as a framework to allow a fuller understanding of the complexity of diverse social identities and the impact of social structures on power, privilege, and oppression. However, the application of intersectionality to teaching in social work education has been relatively absent in the literature. This article describes a 3-hour graduate-level classroom exercise designed to increase knowledge and proficiency of intersectionality. Critical self-reflections of the participants’ experiences are provided to illustrate the evolving growth and awareness that can result from the educational process using this framework. Examples and suggestions for reading assignments and classroom activities are offered. Implications for social work education and future directions are discussed.

For more than a century, the social identities of race, class, and gender have been discussed as a triad of oppression (Hancock, Citation2007). The notion of diversity and social identities has grown to include categories such as sexual orientation, age, and ability. However, during the past 20 years, the emergence of an intersectionality approach has altered categories of difference to include the process whereby societal structures modify or mediate the effects of these categories. The complexity of power structures and their influence on varying social identities allow the individual to be envisioned as uniquely identified rather than grouped or categorized (Hankivsky & Cormier, Citation2011; Murphy, Hunt, Zajicek, Norris, & Hamilton, Citation2009). This framework goes beyond viewing social categories as binary or inclusive versus exclusive, with a shift toward a mosaic of identities with interacting power differentials.

The compelling argument for an intersectional approach in social work is offered through its inclusion of the effects of power, privilege, and “multiple positioning” in the social arena (Dhamoon, Citation2011, p. 230). It acknowledges the diverse experiences of individuals in a social group based on the intersections of differing identities along with access to power, privilege, and resources (Hankivsky & Cormier, Citation2011; Mehrotra, Citation2010). For example, we cannot presume to know the experiences of an older Latina woman because those social identities do not reveal the unique experiences of that individual. The effects of societal mechanisms of power and privilege are generally not included when using the traditional cultural competence perspective. When assessing or understanding a person’s experience through the lens of intersectionality, social workers are less likely to make assumptions or generalize. An intersectional approach removes the tendency to aggregate social identities as if there were no dynamic interaction among them and transforms the framework through which clients are viewed into one of complexity and uniqueness (Hancock, Citation2007; Warner & Brown, Citation2011).

Teaching intersectionality

Although using an intersectional framework in social work education can enhance students’ future work with clients, this approach has been rarely incorporated into social work courses. Even in other disciplines, such as gender or ethnic studies, in which this concept has been widely used, there has been a lack of research-based guidance to teaching intersectionality (Luft & Ward, Citation2009). Nevertheless, a few sources from other disciplines, primarily based on anecdotal teaching experiences, may shed light on different approaches to and common elements of teaching an intersectionality framework.

Teaching effectiveness and student learning are closely connected to content learning and the teaching skills of instructors (Thien, Citation2003). In teaching intersectionality, faculty members need not only to grasp and fully understand the intersectionality framework but also to examine their current teaching practices using an intersectional lens (Jones & Wijeyesinghe, Citation2011). Alejano-Steele et al. (Citation2011) provided a faculty learning module using a learning community approach. Faculty members from diverse disciplines engaged in activities to facilitate self-reflection and discussion that promote a safe environment to share personal experiences on topics related to privilege. This learning experience was intended to translate into teaching students and provide ways for faculty members to deliver content knowledge and create inclusive classroom environments simultaneously (Alejano-Steele et al., Citation2011; Pliner, Iuzzini, & Banks, Citation2011).

One of the most frequently documented elements of teaching intersectionality is the importance of challenging assumptions about issues related to race, gender, and other areas of diversity. This process has been described as “unlearning familiar frames of reference … rooted in various histories of privilege” (Davis, Citation2010, p. 139) and “to disrupt and destabilize potentially predetermined student conceptions” (Carlin, Citation2011, p. 55–56). To facilitate critical self-reflection and discussion, various instructional methods and media have been used, including classroom exercises (e.g., self-interview, case scenarios with an ethical dilemma, audiovisual materials) and reading materials (Banks, Pliner, & Hopkins, Citation2013; Case & Lewis, Citation2012; Ferber & Herrera, Citation2013; Goodman & Jackson, Citation2012; Lee, Citation2012). These practices also include service-learning, internships, capstone projects, and undergraduate research (Kuh, Citation2008). These teaching techniques bring the course material to life for students and represent high-impact educational practices that have been used in higher education to engage students in their own learning (Kuh, Citation2008). A sample of resources for teaching intersectionality using these techniques is provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Active and experiential learning

Traditional pedagogical methods, used for teaching children with a primary focus on the acquisition of knowledge, content, and skills; lecturing; reading; and the use of audiovisual technology (Kramer & Wrenn, Citation1994), may not be suitable for teaching intersectionality to graduate students. For adult learners, andragogical teaching methods (or active learning) that allow students to learn through experience are likely to be more effective. Adult learners tend to be more self-directed and have experience to draw from, a social role orientation, a desire to immediately apply learned material, and a more problem-oriented approach to learning (Gitterman, Citation2004; Kramer & Wrenn, Citation1994). However, students may have different learning styles, and using a variety of teaching techniques can increase the odds of reaching more students (Friedman, Citation2008).

Teaching intersectionality often requires the use of high-impact practices that allow content to be incorporated via active learning and result in the integration of theory and practice (Friedman, Citation2008; O’Neal, Citation1996; Wong & Lam, Citation2007). Because active and experiential leaning requires a degree of risk on the part of students, especially when the material is sensitive or controversial, instructors need to foster a classroom climate conducive to this teaching technique and provide a safe and trusting atmosphere to allow learning to take place (Cross-Denny & Heyman, Citation2011; Edwards & Richards, Citation2002). Teaching the intersectionality framework may also be especially suited to internships or service learning in a field placement. As the signature pedagogy of social work education, fieldwork has been a successful approach to student achievement of practice competencies (Holden, Barker, Rosenberg, Kuppens, & Ferrell, Citation2011; Shulman, Citation2005).

Much of the academic literature on teaching intersectionality has originated from disciplines outside social work and resulted in a semester-long course focused on gender, race, or sexuality. Building on these existing examples of intersectionality teaching methods, social work educators can adapt the curricula to master’s-level courses. Social work courses typically require a flexible teaching approach responsive to the unique experiences and varied social contexts of diverse populations. Given the limited information on teaching intersectionality to social work students, we describe an introductory class session on intersectionality.

Method

Course description

Social Worker’s Response to Human Difference is a required course in the foundation MSW curriculum of a school of social work at a research-intensive public university in the southeastern United States. The course curriculum was developed and taught by Robinson, and designed using a team-based learning methodology (Robinson, Robinson, & McCaskill, Citation2013). Course goals are to develop competence in the Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (Council on Social Work Education, Citation2008) of engaging diversity and difference in practice (Educational Policy 2.1.4) and advancing human rights and social justice (Educational Policy 2.1.5). These standards instruct social work educators to include intersectionality in their teaching of diversity and social justice (Garran & Werkmeister Rozas, Citation2013). Course objectives to achieve these goals include building a knowledge base in theoretical and practice issues related to diversity and related historical, political, and socioeconomic forces, and acquiring and demonstrating development of self-awareness and personal biases.

At the beginning of the semester, students were assigned to teams based on gender and race so that each group was composed of mixed races, mixed genders, and known sexual orientations. The class participants were 32 graduate students—28 women and 4 men—and were a combination of traditional and nontraditional students ranging in age from 22 to 55 years. Most were in the foundation year of the MSW program.

The intersectionality assignment

The purpose of the assignment was to introduce a paradigm shift from the traditional perspective of cultural competence to a more inclusive perspective using the intersectionality framework. This paradigmatic shift was an effort to incorporate power and privilege into the equation when working with clients and to encourage students to view clients as unique individuals instead of assigning them to racial groups. The assignment was completed near the end of the semester after extensive discussions on race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and privilege. The students were assigned five manuscripts (African American Policy Forum, Citation2013; Association for Women’s Rights in Development, Citation2004; Crenshaw, Citation1991; Knudsen, Citation2006; Nash, Citation2008) on intersectionality to read prior to Intersectionality Day (a day of class devoted to teaching students about intersectionality, created by Robinson).

The students were instructed to read the manuscripts and come to class with a detailed analysis using the approach of “analyzing the logic of an article, essay or chapter” recommended by Paul and Elder (Citation2003, p. 36). Students were asked to use the manuscripts to formulate a definition of intersectionality they could articulate in class. The students were also informed that they might be called on to lead a discussion of the assigned readings. Additionally, two weeks prior to Intersectionality Day, a student was selected from several volunteers to lead an intersectionality exercise (Australian Institute of Social Relations, Citation2010) adapted and altered by Robinson for use by students in the United States; it was originally developed for use in Australia.

Intersectionality day class session (3 hours)

Part 1 (30 minutes)

The students were assigned to discuss each manuscript with their preselected teams. The instructor (Robinson) circulated from group to group prompting more detailed discussion of the manuscripts while eliciting detailed definitions of intersectionality and encouraging the students to develop a mutually agreed-on definition.

Part 2 (30 minutes)

The teams were required to develop an argument for each reading, explaining why each manuscript represented intersectionality and discussing which manuscripts they believed best represented their combined definition of intersectionality. The students were also required to answer any questions raised by their classmates during their brief presentation. Once a manuscript was discussed, the remaining teams had to select a different manuscript to discuss. By the end of this phase, all five manuscripts were discussed.

Part 3 (60 minutes)

The next phase consisted of the intersectionality exercise. The students received a random identity (see for details), were asked to line up in groups of six, and were asked to respond to a series of statements (see for examples of identity cards and statements) by the student facilitator. The students moved forward or backward as dictated by their identities described on the cards. At the end of the exercise, students questioned the participants and made observations about why each of the students ended up in certain positions. This exercise differs from the traditional power line exercise (also known as examining class and race; Kivel, Citation2002, Citation2011) in that the identity cards had preassigned character descriptions. This was intended to expose students to people with varying experiences navigating society because of their social identities and access to power and privilege.

After the exercise, a general group discussion was held and students expressed their thoughts on why certain people progressed to the front of the class and why some remained behind. Several students became emotional during the exercise. For instance, an Asian student confessed with tears in her eyes, “I am married to a White man and our daughter looks White so I allowed her to pass as White by not being seen with her in our town because she would have been teased.”

A Caucasian student stated, “I must admit that I was under the belief that all people in our society had equal rights but this exercise proved me wrong.”

An African American student said, “I know Black people had it bad; I guess I never thought about people with disabilities, immigrants, and gay and lesbians having difficulties negotiating life.”

Another student emotionally described her household environment:

My mother [Caucasian] is a lesbian living with a Black woman in a trailer park in a small town. The relationship is physically abusive and when the police are called they sneer as if to say, you deserve it. I can’t figure out if it is because it’s an interracial relationship or if it is because they are lesbians… . Hmm, now I know it’s all of the above.

Many of the students admitted that they never realized how factors other than race and gender influenced choices individuals made and how these individuals were perceived while negotiating life. Finally, several students shared their own formulations of what intersectionality meant to them (pseudonyms have been substituted for student names).

I think it’s important to think of intersectionality as a way to separate people to make them unique, but also connect people with their commonalities. (Peter)

I see intersectionality as joining people together, because while each person is different than the next, they will always intersect in a common way with another person. (Angela)

Intersectionality, to me, is a great way to explain the complex interconnections in oppression and discrimination. I also appreciate that it takes into account the subjective experiences of individuals (Sabrina).

Intersectionality is identities and experiences that combine with one another at different points in life and in different ways to create endless types of human experiences. (Cynthia)

Part 4 (30 minutes)

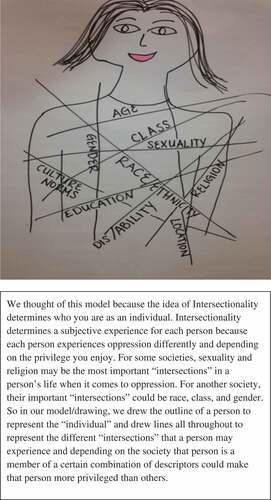

The information obtained during Parts 1 and 2 was used as a basis for Part 4. Each team received a poster board and colored markers and was instructed to depict and describe the group’s definition of intersectionality as if the group members were explaining it to a class of high school students. See for an example of an illustration and description developed and presented by one team.

Conclusion of exercise (20 minutes)

The full exercise was processed at the end of class, and the instructor challenged the students to consider the intersectionality framework in their other social work courses and practicum or field assignments. Students were asked the following questions:

How can intersectionality change the way in which you interact with clients?

Should the intersectionality framework be considered when screening clients for treatment?

How does the intersectionality framework influence treatment planning?

How can intersectionality influence the way in which we conduct research?

Instructor reflections

The instructor (Robinson) said this course was very rewarding because it was the first time the paradigm of intersectionality was introduced to the students. Teaching the subject matter and infusing intersectionality into the course content was challenging because it represented a shift from the traditional framework for understanding diversity. The following items are lessons learned regarding conducting the class exercise and teaching intersectionality content:

To effectively teach intersectionality, the entire course should be centered on this concept, not just one day. There are numerous manuscripts on intersectionality that can be used as a primary text instead of the current text that has traditional sections based on shared characteristics.

The projects depicted during Intersectionality Day should be a culmination of an entire semester rather than one day of reading assignments because students had many questions on intersectionality that could have been answered with additional readings and discussion during the course of the semester.

The reflections of students indicated they were genuinely interested in learning more about the concept and how it can be applied in other courses and practice. This led the instructor to conclude that intersectionality should be considered as the overarching theoretical framework in the social work curriculum because it teaches students to wrestle with concepts of power, oppression, and identity as they relate to treating clients as individuals and not as group members based on commonalities.

Preplanning for the activity should include (a) educating other faculty members on the intersectional framework to foster support for content delivery and (b) instructor self-reflection on his or her social location and its effect on the class process.

Implications for social work education

As illustrated by the exercise and comments offered by students and the instructor, the intersectionality paradigm offers a broader identity of the individual and a perspective that includes unique life experiences. These contain not only different or common identities but a knapsack of privilege that each identity carries, as described by McIntosh (Citation1989). The contents of this knapsack are constantly changing, and the privileges each person has access to change across the lifespan.

The intersectionality paradigm allows students to view client systems within an ever changing context. This eliminates a cookie-cutter approach to assessment and interventions in a cultural competence framework and expands the scope to infinite possibilities for helping. Identifying a client’s unique experiences can better attune practitioners to tailoring interventions to suit client needs. Intersectionality fits well with the social work perspective of considering multiple systems and their effects on clients. It appropriately situates the person-in-environment concept within the context of structural forces created by power and privilege. Introducing this concept at the beginning of a social work student’s academic studies would allow a holistic view, supporting development of creative solutions to unique and complex problems students will face throughout their careers.

Supplemental Table 1

Download MS Word (16.8 KB)Supplemental materials

Supplemental materials for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Allen Robinson

Michael Allen Robinson an assistant professor at The University of Georgia. Bronwyn Cross-Denny is an Assistant Professor at Sacred Heart University. Karen Kyeunghae Lee is an Assistant Professor at California State University, Fullerton. Lisa Marie Werkmeister Rozas is an Associate Professor at the University of Connecticut. Ann-Marie Yamada is an Associate Professor at the University of Southern California.

Bronwyn Cross-Denny

Michael Allen Robinson an assistant professor at The University of Georgia. Bronwyn Cross-Denny is an Assistant Professor at Sacred Heart University. Karen Kyeunghae Lee is an Assistant Professor at California State University, Fullerton. Lisa Marie Werkmeister Rozas is an Associate Professor at the University of Connecticut. Ann-Marie Yamada is an Associate Professor at the University of Southern California.

Karen Kyeunghae Lee

Michael Allen Robinson an assistant professor at The University of Georgia. Bronwyn Cross-Denny is an Assistant Professor at Sacred Heart University. Karen Kyeunghae Lee is an Assistant Professor at California State University, Fullerton. Lisa Marie Werkmeister Rozas is an Associate Professor at the University of Connecticut. Ann-Marie Yamada is an Associate Professor at the University of Southern California.

Lisa Marie Werkmeister Rozas

Michael Allen Robinson an assistant professor at The University of Georgia. Bronwyn Cross-Denny is an Assistant Professor at Sacred Heart University. Karen Kyeunghae Lee is an Assistant Professor at California State University, Fullerton. Lisa Marie Werkmeister Rozas is an Associate Professor at the University of Connecticut. Ann-Marie Yamada is an Associate Professor at the University of Southern California.

Ann-Marie Yamada

Michael Allen Robinson an assistant professor at The University of Georgia. Bronwyn Cross-Denny is an Assistant Professor at Sacred Heart University. Karen Kyeunghae Lee is an Assistant Professor at California State University, Fullerton. Lisa Marie Werkmeister Rozas is an Associate Professor at the University of Connecticut. Ann-Marie Yamada is an Associate Professor at the University of Southern California.

References

- African American Policy Forum. (2013). A primer on intersectionality. New York, NY: Author. Retrieved from http://aapf.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/59819079-Intersectionality-Primer.pdf

- Alejano-Steele, A., Hamington, M., MacDonald, L., Potter, M., Schafer, S., Sgoutas, A., & Tull, T. (2011). From difficult dialogues to critical conversations: Intersectionality in our teaching and professional lives. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 125, 91–100. doi:10.1002/tl.436

- Association for Women’s Rights in Development. (2004, August). Intersectionality: A tool for gender and economic justice. Women’s Rights and Economic Change, 9. Retrieved from https://lgbtq.unc.edu/sites/lgbtq.unc.edu/files/documents/intersectionality_en.pdf.

- Australian Institute of Social Relations. (2010). AVERT family violence: Collaborative responses in the family law system. Adelaide, Australia: Author. Retrieved from http://www.avertfamilyviolence.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2013/06/Intersectionality.pdf

- Banks, C. A., Pliner, S. M., & Hopkins, M. B. (2013). Intersectionality and paradigms of privilege: Teaching for social change. In K. A. Case (Ed.), Deconstructing privilege: Teaching and learning as allies in the classroom (pp. 102–114). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Carlin, D. (2011). The intersectional potential of queer theory: An example from a general education course in English. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 125, 55–64. doi:10.1002/tl.433

- Case, K. A., & Lewis, M. K. (2012). Teaching intersectional LGBT psychology: Reflections from historically Black and Hispanic-serving universities. Psychology & Sexuality, 3, 260–276. doi:10.1080/19419899.2012.700030

- Council on Social Work Education. (2008). Educational policy and accreditation standards. Retrieved from http://www.cswe.org/File.aspx?id=41861

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039

- Cross-Denny, B., & Heyman, J. C. (2011). Social justice education: Impact on social attitudes. Journal of Aging in Emerging Economies, 3(1), 4–16.

- Davis, D. R. (2010). Unmirroring pedagogies: Teaching with intersectional and transnational methods in the women and gender studies classroom. Feminist Formations, 22(1), 136–162. doi:10.1353/nwsa.0.0120

- Dhamoon, R. K. (2011). Considerations on mainstreaming intersectionality. Political Research Quarterly, 64, 230–243. doi:10.1177/1065912910379227

- Edwards, J. B., & Richards, A. (2002). Relational teaching: A view of relational teaching in social work education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 22(1/2), 33–48. doi:10.1300/J067v22n01_04

- Ferber, A. L., & Herrera, A. O. (2013). Teaching privilege through an intersectional lens. In K. A. Case (Ed.), Deconstructing privilege: Teaching and learning as allies in the classroom (pp. 83–101). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Friedman, B. D. (2008). How to teach effectively: A brief guide. Chicago, IL: Lyceum Books.

- Garran, A. M., & Werkmeister Rozas, L. (2013). Cultural competence revisited. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 22, 97–111. doi:10.1080/15313204.2013.785337

- Gitterman, A. (2004). Interactive andragogy: Principles, methods, and skills. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 24(3/4), 95–112. doi:10.1300/J067v24n03_07

- Goodman, D. J., & Jackson, B. W. III., (2012). Pedagogical approaches to teaching about racial identity from an intersectional perspective. In C. L. Wijeyesinghe, & B. W. Jackson III (Eds.), New perspectives on racial identity development: Integrating emerging frameworks (2nd ed., pp. 216–240). New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Hancock, A.-M. (2007). When multiplication doesn’t equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspectives on Politics, 5, 63–79. doi:10.1017/S1537592707070065

- Hankivsky, O., & Cormier, R. (2011). Intersectionality and public policy: Some lessons from existing models. Political Research Quarterly, 64, 217–229. doi:10.1177/1065912910376385

- Holden, G., Barker, K., Rosenberg, G., Kuppens, S., & Ferrell, L. W. (2011). The signature pedagogy of social work? An investigation of the evidence. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 363–372. doi:10.1177/1049731510392061

- Jones, S. R., & Wijeyesinghe, C. L. (2011). The promises and challenges of teaching from an intersectional perspective: Core components and applied strategies. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 125, 11–20. doi:10.1002/tl.429

- Kivel, P. (2002). Examining class and race: An exercise. Retrieved from http://www.paulkivel.com/resources/exercises/item/126-examining-class-and-race

- Kivel, P. (2011). Uprooting racism: How White people can work for racial justice. Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society.

- Knudsen, S. V. (2006). Intersectionality–A theoretical inspiration in the analysis of minority cultures and identities in textbooks. Caught in the Web or Lost in the Textbook, 53, 61–76

- Kramer, B. J., & Wrenn, R. (1994). The blending of andragogical and pedagogical teaching methods in advanced social work practice courses. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 10(1/2), 43–64. doi:10.1300/J067v10n01_03

- Kuh, G. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

- Lee, M. R. (2012). Teaching gender and intersectionality: A dilemma and social justice approach. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36, 110–115. doi:10.1177/0361684311426129

- Luft, R. E., & Ward, J. (2009). Toward an intersectionality just out of reach: Confronting challenges to intersectional practice. In V. Demos, & M. T. Segal (Eds.), Perceiving gender locally, globally, and intersectionally (pp. 9–37). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group. doi:10.1108/S1529-2126(2009)0000013005

- McIntosh, P. (1989, July/August). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace and Freedom, 10–12.

- Mehrotra, G. (2010). Toward a continuum of intersectionality theorizing for feminist social work scholarship. Affilia, 25, 417–430. doi:10.1177/0886109910384190

- Murphy, Y., Hunt, V., Zajicek, A. M., Norris, A. N., & Hamilton, L. (2009). Incorporating intersectionality in social work practice, research, policy, and education. Washington, DC: NASW Press.

- Nash, J. C. (2008). Re-thinking intersectionality. Feminist Review, 89, 1–15. doi:10.1057/fr.2008.4

- O’Neal, G. S. (1996). Enhancing undergraduate student participation through active learning. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 13(1/2), 141–155. doi:10.1300/J067v13n01_10

- Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2003). Critical thinking: Teaching students how to study and learn (Part III). Journal of Developmental Education, 26(3), 36–37.

- Pliner, S. M., Iuzzini, J., & Banks, C. A. (2011). Using an intersectional approach to deepen collaborative teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 125, 43–51. doi:10.1002/tl.432

- Robinson, M. A., Robinson, M. B., & McCaskill, G. (2013). Teaching Note—An exploration of team-based learning and social work education: A pedagogical fit. Journal of Social Work Education, 49, 774–781. doi:10.1080/10437797.2013.812911

- Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134, 52–59. doi:10.1162/0011526054622015

- Thien, S. J. (2003). A teaching–learning trinity: Foundation to my teaching philosophy. Journal of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Education, 32, 87–92.

- Warner, D. F., & Brown, T. H. (2011). Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Social Science & Medicine, 72, 1236–1248. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.034

- Wong, D. K. P., & Lam, D. O. B. (2007). Problem-based learning in social work: A study of student learning outcomes. Research on Social Work Practice, 17, 55–65. doi:10.1177/1049731506293364