ABSTRACT

The 2020 GADE Director Survey aimed to understand program and student characteristics, support for students, curriculum focus and design, and students’ job search support and outcomes in PhD and DSW programs. In general, PhD programs focus on building students’ research capacities, including interdisciplinary research and leadership in higher education and research-oriented organizations, whereas DSW programs prepare students to contribute in the areas of clinical expertise, leadership in non-academic settings, and advancing social work practice at multiple levels. The program structure, curricula and graduation requirements are organized according to the distinct emphasis of each type of program. These findings have significant implications for doctoral programs as they navigate their strategic directions in the changing landscape of doctoral social work education.

The landscape of doctoral education in social work has changed in the past decade, with the reemergence and accreditation of practice doctorate (Doctor of Social Work [DSW]) programs and the gradual tightening of the social work academic job market (Acquavita & Tice, Citation2015; Lightfoot & Zheng, Citation2020; Council on Social Work Education [CSWE], Citation2020a). Other changes reflect the evolving and competing needs of social work doctoral education, including the need for high-quality science, antiracist and inclusive practices, improved pedagogical training, and strategies to address the increasing gap between research and practice (Anastas, Citation2015; Guerrero et al., Citation2018; Johnson & Munch, Citation2010). In this complex context, there has been renewed interest regarding the role of both PhD and DSW programs in doctoral education (Howard, Citation2016; Kurzman, Citation2015). While PhD programs have been the predominant doctoral degree in recent decades, scholars have noted historical shifts in what has been considered the preferred doctoral degree for social work, along with varying emphases on practice and research expertise (Anastas, Citation2015; Howard, Citation2016). While social work as a discipline clearly benefits from findings based on rigorous research, the increasing emphasis on research productivity and securing external funding also poses challenges to retaining practice expertise among both current and future social work faculty (Johnson & Munch, Citation2010). The current debates regarding the role and priorities of social work doctoral education reflect a long history of development and adaptation that continues to influence the landscape of doctoral education.

Historical trends in doctoral social work education

The development of social work doctoral education began with Bryn Mawr College establishing the first PhD program in social work in 1915, which was followed by the development of research-oriented PhD programs in the 1920s and 1930s and practitioner-based doctoral programs (DSWs) in the 1940s and 1950s (Lightfoot & Beltran, Citation2018). By the early 1970s, there were more DSW than PhD programs with little discernable difference between the two types of doctoral programs. In addition, DSW and PhD coursework did not differ substantially (Bolte, Citation1971; Crow & Kindelsperger, Citation1975). However, since then, there was a move to prefer PhDs over DSWs because of the increased emphasis on research rigor in doctoral education (Sowers & Social Work Policy Institute, Citation2013). An important milestone was the establishment of The Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work (GADE) in 1981, with the aims of strengthening research training in doctoral education, promoting the interests of doctoral programs, developing a structure for information exchange, stimulating effective educational and research efforts, and collaborating with other national organizations (Jorgensen, Citation1985). The establishment of the Institute for the Advancement of Social Work Research in 1993, the Society for Social Work and Research in 1994, the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare in 2009, and the Doctoral Education Roundtable at Islandwood in the early 2010s all reflected social work’s growing dedication to research as an integrative scientific discipline (Brekke, Citation2014; Cnaan, Citation2018; Uehara et al., Citation2017). By the turn of the 21st century, all DSW programs had been replaced by PhD programs as the social work profession sought to increase the scientific rigor and reputation of its doctoral education and research base (Lightfoot & Beltran, Citation2018).

Resurgence of DSW programs

Since the mid-2000s, there has been a resurgence of DSW programs plausibly fueled by demand of advanced social work practitioners desiring doctoral education with a practice rather than research focus, with potential benefits for enhanced status in an interdisciplinary practice community and competitiveness for higher-level jobs (Howard, Citation2016; Sowers & Social Work Policy Institute, Citation2013). The resurgence of DSW programs also addresses challenges encountered by social work education and the profession. For the social work profession, there is a lack of senior clinicians to advance practice knowledge that could be due to retirement, lack of rigorous clinical supervision at the agency level, as well as policy and funding changes (Floersch, Citation2013). In addition, with other disciplines—such as clinical psychology, nursing, public health, and occupational therapy—moving toward advanced practice doctorates, DSW programs can help social workers attain doctorate-level professional credentials on par with peers in other disciplines and may help with recruitment and retention of advanced professionals in the profession (Sowers & Social Work Policy Institute, Citation2013).

Another major issue in the social work profession is the integration of research and practice. While social work has embraced evidence-based practice since the 1990s, the gap between research innovation and practice implementation has not been resolved. The focus of DSW education could also help bridge the research–practice gap by nurturing “clinician scholars” who can produce practice-relevant knowledge, disseminate research to practice, and contribute to research capacity development by strengthening research and practice integration (Anastas, Citation2015, p. 305). Also, while CSWE requires 2 years of post–Master of Social Work (MSW) practice experience for faculty to teach direct practice courses, there has been a steady decline in the number of tenure-track faculty members who have strong practice experience (Johnson & Munch, Citation2010). DSW graduates could potentially become part of the educational workforce to enhance MSW and Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) education (Barsky, Citation2014; Diaz, Citation2015). Finally, there are institutional factors including the revenue potential of these programs as they tend to be low cost and students typically pay full tuition (Thyer, Citation2015).

Lessons learned from other disciplines

The resurgence of advanced practice doctorate programs invites considerations of multiple issues related to the social work profession, such as licensure, accreditation, market demand, and the role of the MSW degree, among others. Several issues are particularly relevant to doctoral education in social work: What is the uniqueness of PhD and DSW programs in terms of their program structure, student aspirations, curriculum, and program requirements that distinctively differentiate both program types? How could the coexistence of PhD and DSW programs potentially contribute to the task of bridging the research–practice gap and what should be the relationship between both program types organizationally? How should DSW education be financed? Who should be the organizational home for DSW education (Social Work Policy Institute, Citation2013)? Another major issue involves the market demand for graduates of both types of programs. For many years, academic job openings exceeded the number of graduating doctoral candidates and there was concern about an undersupply of qualified doctoral graduates for faculty positions (Acquavita & Tice, Citation2015; Anastas, Citation2013), but the large increase in doctoral-level graduates (especially in new DSW programs) may be contributing to increased competitiveness of the job market. A recent study of the 2017–2018 social work job market found an oversupply of doctoral candidates seeking tenure-track jobs, with about one-fifth of doctoral candidates not obtaining a desired tenure-track position (Lightfoot & Zheng, Citation2020).

The experience of other disciplines such as Doctor of Psychology (PsyD), nursing (DNP), public health (DPH, and occupational therapy (OTD) provides useful guidance and lessons as social work doctoral education navigates its own path of development. First, there tends to be overall consistency across different disciplines regarding the primary focus of research and practice doctorates (Hage et al., Citation2020), but the specific program structure, curriculum design, and process of individual doctorate programs can show significant variation. For example, a scoping review of nursing doctoral programs indicated the existence of variations in program structure, admission criteria, and curriculum content. These variations pose potential challenges for assessing the quality and effectiveness of doctorate education, especially when there is not a clear, universal framework of outcome indicators to assess doctoral programs (Dobrowolska et al., Citation2021). Second, nursing has been intentional in making concerted efforts to connect research and practice through the formation of interdisciplinary teams that include both PhDs and DNPs to solve complex medical problems encountered in practice (Trautman et al., Citation2018). Regarding accreditation and licensing practices, the experience of other professions demonstrates different pathways for the coexistence of master’s- and doctoral-level practice education. For example, advanced practice nursing education plans to move to a professional doctorate (DNP) by 2025 and no new master’s-level advanced practice nursing programs have been accredited since 2015 (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Citation2015). This transformation is grounded in the changing demands of healthcare and the competencies needed by employers (Bednash & Social Work Policy Institute, Citation2013), but raises important questions about the potential future of the MSW as a terminal practice degree as DSW programs spread (Social Work Policy Institute, Citation2013; Thyer, Citation2015). For occupational therapy, on the other hand, doctoral students (OTD) are required, like nursing, to have practicum hours, although both masters and OTD levels sit for the same certification examination and meet the same licensing standards (Harvison & Social Work Policy Institute, Citation2013). Another lesson involves financing of the DSW programs and the potential debt load for students. For Clinical and Counseling Psychology doctoral programs, large differences were observed regarding anticipated debt-at-graduation, with PsyD students reporting the highest anticipated debt (Borgogna et al., Citation2021).

The trends of the development of doctoral education could be a reference to social work doctorate education as we examine our own professional context and market demands to navigate the development of doctoral education. In sum, the lessons learned from these other disciplines include but are not limited to: the importance of clearly establishing the mission and purpose of the advanced practice degree, explicitly laying out how the DSW degree fits into the existing continuum from BSW to MSW, consideration of licensing and accreditation process that responds to the professional context and market demands, the need to establish a framework of outcome indicators to guide curriculum design and assess doctoral programs, the need for intentional efforts on fostering collaborations between research and practice doctorates to facilitate the bridging of the research–practice gap, and thoughtful considerations pertaining to the financing of these doctoral programs.

Current status of social work doctoral education

Currently, most PhD programs are research-focused degrees, offering intensive research training and mentoring with only a few PhD programs that include a clinical component. These programs are offered by both public and nonprofit institutions but are more likely to be offered in universities classified as research institutions according to the Carnegie Classification (Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research, Citation2018), with about 65% in R1 universities, 20% in R2 universities, and the remaining 15% in institutions classified as R3, Masters or Baccalaureate (Beltran, Lightfoot, & Sweeny, Citation2020). The growth of PhD programs is steady and CSWE has tracked a 6.7% increase from 2014 to 2019 (CSWE/GADE, Citation2021), although the number of PhD students enrolled at institutions responding to the CSWE Annual Survey in 2019 was approximately 1,900, down from almost 2,500 in 2009 (CSWE, Citation2020b). In contrast to the stable growth of PhD programs, DSW programs experienced rapid growth in the past decade, including a 260% increase in programs from 2014 to 2019 (CSWE/GADE, Citation2021). Currently, there are 24 DSW programs with several more in planning stages. These new DSW programs can be found in public, private, and for-profit institutions, at research universities and teaching colleges, and in social work schools with and without PhD programs. There exists wide variation in DSW program structure across different institutions, including credits required for graduation, but programs usually require an MSW for admission. Slightly less than half are clinically oriented, with the remainder focused on topics such as community practice, administration, and teaching (Beltran et al., Citation2020).

Regarding organizational home and accreditation, GADE remains the home organization for both PhD and DSW program directors with CSWE assuming the role for accreditation. Following a 2-year process of drafting, revising, and gathering feedback from various constituencies including GADE, the National Association of Deans and Directors, and individual CSWE members, CSWE formally announced the approval of the Educational and Accreditation Policy Standards for DSW programs on June 19, 2020 (CSWE, Citation2020a). While the issue regarding organization home and accreditation has partly resolved, there is still a lack of information regarding questions about program and student characteristics, financial support and resources provided to students, curriculum focus and design, and students’ job search support and outcomes. The 2020 GADE Director Survey aimed to examine these questions, as it is important to understand the overall state of doctoral education, as well as the uniqueness of PhD and DSW programs and how both types of programs can make complementary contributions to doctoral education. The purpose of this survey is to describe the current landscape of both PhD and DSW program types, as such an understanding is critical in helping doctoral program administrators and faculty to navigate their programs’ strategic direction, pedagogical focus and practices, and future development.

Method

The 2020 GADE Director Survey employed a cross-sectional survey design to understand the current landscape of doctoral education pertaining to characteristics of programs, directors, and students; support and resources provided to program directors and students; curriculum focus and design; as well as students’ job search support and outcomes. Survey items were self-constructed based on current understanding of the selected focus of the survey. These items were then reviewed and discussed by GADE board members who provided expert input to the refinement of the survey items. The survey was sent to the program directors of all GADE member institutions via the GADE electronic mailing list between April 1 and June 7, 2020. At the time of the survey, GADE included 10 international (9 in Canada and 1 in Israel) and 86 United States–based institutions. GADE membership included 87 PhD programs (77 in the United States, 9 in Canada, and 1 in Israel) and 17 DSW programs in the United States. To note, 8 U.S. member institutions offer both PhD and DSW programs (GADE, Citation2019). An Institutional Review Board (IRB) of a major university determined this survey to be IRB exempt because it was an anonymous survey on educational data. To note, the GADE Director Survey is part of a collaborative effort between GADE and CSWE on a project that examined the current landscape of doctoral education. The CSWE-GADE Report on the Current Landscape of Doctoral Education in Social Work was published in June 2021 based on partial data from the 2020 GADE Director Survey and the 2019 CSWE Annual Survey (CSWE/GADE, Citation2021). Permission for adaption of and was obtained from CSWE and the original author team.

Table 1. Program information.

Table 2. Student support.

Table 3. Students’ goals when enrolling in program.

Table 4. Curriculum.

Table 5. Graduation requirements and job search.

Procedures

The survey included up to 45 questions pertaining to program information, student demographics and goals, support and resources provided for students, curriculum and graduation requirements, and students’ job search process and outcomes. The questions included 28 multiple choice, 2 Likert-type, 12 fill-in, and 3 open-ended questions, with 3 questions (1 multiple choice, 1 fill-in, 1 open-ended) that only appeared for some respondents based on their previous responses. Two open-ended questions asked about the focus of the doctoral curriculum and any additional information not captured by the closed-ended survey questions. In addition, the survey invited directors to provide graduation and job search information for the 2018–2019 academic year, as this was the most recent class for which complete information could be provided.

Data analysis was primarily quantitative, using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software. For overall data across all programs, we conducted descriptive statistics, including percentages for categorical data and mean, standard deviation, range, and median for continuous data and ordinal rating scales. The study used content analysis to identify common codes based on answers to the open-ended questions and then quantitized the data by counting the occurrence of each code. The study analyzed each question by program type and conducted statistical tests, including Fisher’s exact test, independent samples t-tests and z-tests, to compare the statistical significance of between group differences. For Likert-scale responses of importance from 1 Not at all important to 5 Extremely important, we treated the data as continuous data and compared the group means of PhD and DSW programs using independent samples t-tests. Codes from open-ended questions were compared using z-tests of the proportion of each theme occurring by program type.

Results

Program directors of 78 doctoral social work programs completed the survey. Excluding two responses that combined PhD and DSW program data in the same response and one program that was still under development, the data analysis included 60 PhD program directors and 15 DSW directors. At the time of the survey, GADE membership included 87 PhD programs (77 in the United States, 9 in Canada, and 1 in Israel) and 17 DSW programs in the United States, so the data include 69% of PhD programs and 88% of DSW programs targeted by the survey.

Program information

shows the institutional characteristics and program options of the PhD and DSW programs that responded to the survey. Overall, 71.9% of PhD programs and 45.5% of DSW programs indicated they were at public institutions rather than private institutions. Among the 16 PhD programs and 6 DSW programs offered through private institutions, 2 PhD programs (12.5%) and 2 DSW programs (33.3%) indicated their institution was for profit (p=.292). Further, three-quarters of PhD programs (75.4%) and just over half of DSW programs (54.5%) operated at research-intensive (R1) universities. Regarding program options, 19 PhD programs offered an MSW/PhD combined track (31.7%), 3 DSW programs offered a MSW/DSW combined track (20%), and dual degrees with other disciplines were rarely offered at any programs (3.3% PhD, 0% DSW; p=.700). However, there were significant differences between PhD and DSW programs regarding method of instruction (p<.001) and enrollment options (p=.008). At the time of the survey, the majority of PhD programs offered only in-person instruction (86.4%), with 6 programs offering a mix of in-person and online instruction (10.2%), and only 2 programs (3.4%) provided fully online instruction or online courses with face-to-face residencies. In contrast, 46.7% of DSW programs offered online-only instruction with or without face-to-face residences, 40% offered a mix of in-person and online instruction, and only 13.3% offered only in-person, seated courses. Similarly, 40% of DSW programs offered only part-time enrollment compared to 4.3% of PhD programs, with the remaining programs requiring full-time enrollment only (47.8% PhD, 40% DSW) or offering both full- and part-time options (47.8% PhD, 20% DSW). Regarding student enrollment, 43 PhD programs responded with an average enrollment of 31.28 students (SD=18.64, median=30) and 5 DSW programs responded with an average of 101.4 students (SD=144.03, median=45). However, the small number of DSW responses and presence of very large outliers precluded a finding of statistical difference in average enrollment (t(4.016)=−1.088, p=.338).

Student demographics

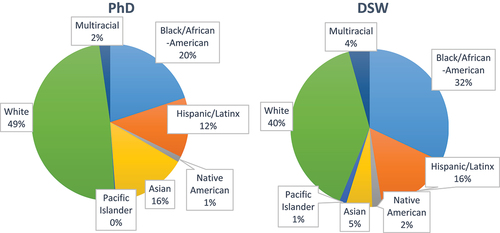

The challenges posed by missing data and outliers, especially among DSW programs, affected estimates of student demographics between PhD and DSW programs. For programs that provided both total enrollment and their estimated percentages for demographics (PhD: n=33; DSW: n=5), we calculated the number of students belonging to each racial/ethnic group in each program, and then totaled each group across all programs that provided information to produce the overall demographics (). The findings appear to show slightly more diversity in DSW programs (40% White compared to 49% White in PhD programs), with several notable trends regarding the racial and ethnic makeup of both program types. In particular, Black/African American students comprised an average of 20% of students in PhD programs compared to an average of 32% in DSW programs. Also, Asian students represented one-sixth of PhD students (16%) but only 5% of DSW students based on directors’ responses. The low number of responses and presence of a large DSW outlier precludes drawing any confident conclusions, but the responses suggest the possibility that DSW programs may have a greater proportion of Black/African American students and fewer international and Asian students than PhD programs. Despite the challenges posed by incomplete data and outliers, these findings were consistent with the demographics of PhD and DSW students as reported in the 2019 Statistics on Social Work Education in the United States (CSWE, Citation2020b), which showed a higher percentage of African American/Black students in DSW programs than PhD programs (PhD=22.1% vs. DSW=35.8%) and a higher percentage of Asian students in PhD programs than DSW programs (PhD=9.9% vs. DSW=3.3%).

Student support

An important trend in the survey responses showed that PhD programs tend to provide substantially more financial support to their students than DSW programs (). More than 80% of PhD programs reported offering a guaranteed number of years of funding support for their students, with more than two-thirds of programs giving students an annual stipend. On average, PhD programs provided 3.7 years of guaranteed support (SD=1.25) and an average stipend of $21,448 (SD=$5,595). In contrast, no DSW programs reported giving guaranteed years of funding support or an annual stipend to students. Half of DSW programs offered tuition support for their students, compared to nearly 90% of PhD programs, with a similar breakdown for offering some form of student health insurance as part of a support package (PhD 82.9%, DSW 44.4%). PhD programs also commonly offered research assistantships for students (86.3% of PhD programs), which was not reported by DSW programs, and PhD programs (45%) were also more likely to offer nonresearch assistantships (teaching, administrative, etc.) than DSW programs (11.1%). Most PhD programs (85%) provided conference travel funds for their students, compared to 30% of DSW programs. In addition, significantly more PhD than DSW programs offered students research or dissertation grants (47.5% to 6.7%), summer funding (35.6% to 0), a shared work or office space (74.6% to 6.7%), and analysis software (67.8% to 33.3%). All other types of support—individual office space for students, statistical or grant consultation, a laptop or computer, awards, and various other supports—were offered by a higher percentage of PhD than DSW programs. Overall, PhD students received significantly more support than DSW students from their programs across all assessed domains.

Curriculum and program requirements

To understand programmatic similarities and uniqueness between PhD and DSW doctoral education, the survey asked both groups of program directors questions regarding their students’ goals for entering doctoral education, the focus of their doctoral curriculum, and the courses and graduation requirements of their programs.

Student goals

We asked program directors to rate the importance of goals their students may have when entering their program from 1 Not at all important to 5 Extremely important (). PhD and DSW directors rated comparable importance regading students’ goals of educating the next generation of social workers (PhD: M=4.35, SD=.78; DSW: M=4.42, SD=1.00; t(64)=−.247, p=.806) and developing social work leaders in academic settings (PhD: M=4.04, SD=1.10; DSW: M=3.58, SD=1.38; t(64)=1.235, p=.221). In addition, both PhD and DSW directors stated that students entered doctoral education with the goal of contributing to knowledge development, dissemination, and application, although students in PhD programs emphasize making their contributions through research (PhD: M=4.72, SD=.77; DSW: M=3.67, SD=.99; t(63)=4.052, p<.001) while DSW students place greater importance on making their contributions through advancing specialized practice at micro, mezzo, and macro levels (PhD: M=3.18, SD=1.41; DSW: M=4.67, SD=.49; t(51.717)=−6.017, p<.001). In addition, according to the respondents, DSW students place significantly greater importance than PhD students on advancing clinical expertise (PhD: M=1.80, SD=1.07; DSW: M=3.33, SD=1.44; t(54)=−4.095, p<.001), and developing social work leaders in nonacademic settings (PhD M=3.19, SD=1.21; DSW M=4.42, SD=.67; t(63)=−3.387, p=.001). Although moderately important on average for DSW students, advancing clinical expertise ranked as the least important goal across both PhD and DSW programs.

Doctoral curriculum

Program directors were asked to provide information on the number of courses offered that contribute to different curriculum content in social work, in addition to an open-ended question regarding the focus of their curriculum. While program directors were asked to select the primary area of focus for each course they offer such that each course would be counted once, directors’ responses suggest that at least some respondents might have selected multiple topics related to the same course and thus counted some courses offered in their curriculum multiple times. shows the average number of courses offered that contribute to each area in PhD and DSW programs, as reported by program directors who responded to each question. Overall, knowledge production and dissemination comprised the highest mean number of courses offered in both PhD (M=2.98, SD=2.37) and DSW (M=4.09, SD=2.51) programs, with no significant difference based on program type (t(57)=−1.391, p=.170). There were also nonsignificant differences on courses offered focused on understanding social work and its history (PhD: M .98, SD=.76; DSW: M=1.00, SD=1.21; t(61)=−.071, p=.943), theory (PhD: M=1.85, SD=1.42; DSW: M=1.42, SD=.79; t(62)=1.008, p=.317), and social justice (PhD: M=1.78, SD=2.89; DSW: M=2.88, SD=3.76; t(42)=−.920, p=.363). Regarding developing research capacity, PhD programs offered significantly more courses on quantitative research methods (PhD: M=2.08, SD=1.41; DSW: M=1.18, SD=.60; t(37.224)=3.338, p=.002) and statistical skills (PhD: M=2.56, SD=.83; DSW M=.89, SD=.60; t(59)=5.781, p<.001), with no significant difference in the number of courses on qualitative research methods (PhD: M=1.31, SD=.58; DSW: M=1.80, SD=1.03; t(10.152)=−1.444, p=.179). According to program directors, both PhD and DSW programs offered roughly one course each in mixed methods, intervention research, and policy.

For advancing practice expertise, DSW programs reported significantly more courses offered on average than PhD programs in both micro practice (PhD M=.23, SD=.58; DSW M=3.00, SD=2.29; t(8.241)=−3.599, p=.007) and mezzo practice (PhD M=.18, SD=.39; DSW M=2.30, SD=1.83; t(9.200)=−3.654, p=.005), but there was no significant difference for coursework in macro practice (PhD M=.49, SD=.75; DSW M=.67, SD=.71; t(48)=−.657, p=.514). DSW programs also showed a greater number of courses offered on leadership development (PhD M=.50, SD=.76; DSW M=2.09, SD=2.17; t(10.726)=−2.394, p=.036), with no significant differences on courses offered on professional development (PhD M=1.13, SD=1.38; DSW M=.82, SD=.98; t(56)=.703, p=.485), pedagogy (PhD M=.96, SD=.62; DSW M=1.56, SD=1.13; t(8.956)=−1.543, p=.157), and students’ specialization areas (PhD M=2.89, SD=2.18; DSW M=2.33, SD=1.88; t(48)=.802, p=.426).

We also asked program directors an open-ended question regarding the focus of their doctoral curriculum; we conducted content analysis of these responses and compiled a code list of the major themes in the director responses. Research was the most commonly reported focus of PhD curriculum (84.6%), whereas DSW programs predominantly mentioned clinical practice (71.4%) and leadership (71.4%) when describing their curricular focus. Teaching was the next most common theme for both PhD (40.4%) and DSW programs (50.0%), and about one-fifth of all programs indicated specialized areas of focus in their curriculum (PhD 23.1%, DSW 21.4%). Theory was noted by 16 PhD program directors (30.8%) and 2 DSW directors (14.3%). Roughly one-fifth of PhD directors included policy and social justice when describing their curricular focus, and one-seventh of DSW directors noted administration and organizations and implementation research. Although research was more often mentioned by PhD programs and leadership by DSW programs (p<.001), 35.7% of DSW directors’ descriptions included research and 17.3% of PhD directors’ included leadership, indicating some overlap between the focus of curriculum for PhD and DSW programs.

Program requirements

Respondents from PhD and DSW programs indicated significant differences in candidacy and graduation requirements (). For candidacy, 71.4% of PhD programs included a comprehensive exam or candidacy exam compared to only 26.7% of DSW programs, and 35.7% of PhD and no DSW programs included a qualifying examination. The survey also included an “other” option for write-in responses: 5 PhD (8.9%) and 3 DSW (20.0%) program directors wrote in that a dissertation proposal or prospectus was required to reach candidacy. PhD and DSW programs also reported significantly differences in graduation requirements, with the traditional dissertation serving as the most common option offered at PhD programs (78.6%) but only offered at 20% of DSW programs. Similarly, the multiple manuscripts–style dissertation appeared at over half of PhD programs (55.4%) but only 13.3% of DSW programs (p=.004). In contrast, the capstone project was the most common option reported by DSW programs (46.7%) but only one PhD program (1.8%) required a capstone project. The portfolio option also appeared at two DSW programs (13.3%) but no PhD programs (p=.006). For each aspect of candidacy and graduation requirements, the responses from PhD and DSW directors differed significantly (α=.05).

Student job search

To better understand the career aspirations and job search process of PhD and DSW students, we asked survey respondents questions regarding their students’ job search process and the factors contributing to a successful academic job search for both PhD and DSW graduates. All PhD programs provided some type of formal job search support to students, compared to only two-thirds of DSW programs. PhD programs were more likely to offer students job search seminars (PhD 75%, DSW 46.7%), mock job talks/interviews (PhD 75%, DSW 33.3%), and review students’ application materials (PhD 80.4%, DSW 26.7%). Both PhD (89%) and DSW programs (53%) commonly shared job postings with students who were on the market. It was less common for programs to help students negotiate job offers (PhD 71.4%, DSW 20%) and send out promotional materials about their students (PhD 55.4%, DSW 6.7%), but these practices were still seen in over half of PhD programs.

Finally, we asked the respondents to give ratings (1 Not at all important to 5 Extremely important) for the importance of a number of factors that might influence students’ success while on the academic job market, with both similarities and differences seen in the academic job search process of PhD and DSW students. For PhD programs, the highest areas of importance included research productivity (PhD M=4.39, DSW M=2.00; t(18.068)=9.755, p<.001) and having a focused research agenda (PhD M=4.19, DSW M=1.86; t(41)=5.997, p<.001), which was rated as very important for PhD students but only slightly important for DSW students. Conversly, DSW directors indicated that practice experience was the most important factor for a successful job search (M=4.80, SD=.42), with PhD directors (M=3.56, SD=1.05) indicating that practices experience was only moderately important (t(37.958)=−5.642, p=.008). Teaching experience (PhD M=3.94, DSW M=3.80; t(44)=.427, p=.672) and a good match between student and institution (PhD M=4.33, DSW M=4.11; t(43)=.611, p=.544) were both seen as important for a successful job search by directors of both types of programs. Although external funding was seen as least important by both types of programs, it still rated higher (t(38)=2.853, p=.007) for PhD programs (PhD M=3.06, DSW M=1.75).

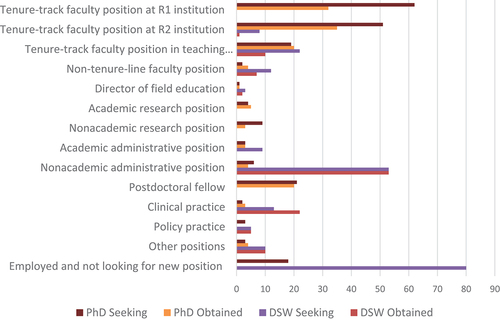

Finally, we asked program directors to provide the number of their students seeking different types of positions in 2018–2019, with directors asked to indicate students’ primary position preference. Although 73% of PhD and DSW directors provided at least some responses in this section, the findings will have to be interpreted with caution because findings do not represent a complete count of the doctoral job market. shows the primary positions sought and obtained by PhD and DSW graduates based on the responses of the PhD and DSW directors who answered the question. Based on this sample, the types of positions sought by PhD and DSW students appeared to differ. Notably, PhD graduates tended to seek tenure-track faculty positions at R1 (n=62) or R2/research and teaching (n=51) institutions, postdoctoral fellowships (n=21), and academic (n=4) or nonacademic (n=9) research positions. In contrast, DSW graduates tended to seek academic (n=9) or nonacademic administrative positions (n=53), clinical practice (n=13), nontenured faculty positions (n=12), or were currently employed and not seeking a new position (n=80). Notably, both PhD (n=19) and DSW graduates (n=22) were reportedly seeking tenure-track positions at teaching universities (PhD n=19, DSW n=22), suggesting some competition in the job market for more teaching-oriented positions. For the most part, positions obtained closely matched the positions sought. PhD graduates tended to obtain tenure-track positions at R1 (n=32), R2 (n=35), or teaching universities (n=20), postdoctoral fellowships (n=20), or other academic and research positions (n=11). In contrast, DSW graduates tended to obtain clinical practice (n=22) and nonacademic administrative positions (n=53), with some DSW students obtaining tenure-track positions at teaching universities (n=10) or nontenured faculty positions (n=7). As previously stated, many DSW graduates were reportedly not looking for a new position, but several graduates did receive promotions upon graduation. Due to the limited responses and missing data, these findings should be interpreted with caution and do not represent a full picture of the doctoral job market.

Figure 2. Students’ positions sought and obtained on the job market.

Discussion

The findings of the 2020 GADE Director Survey provide useful information on the current landscape of doctoral education and highlight trends that will influence the future of social work education. Unlike in the 20th century when PhD and DSW programs were virtually indistinguishable (Crow & Kindelsperger, Citation1975), the findings from this study show that PhD and DSW programs today have distinct emphases and foci in their curriculum, program design, student goals, and job search aspirations and outcomes. That said, PhD and DSW programs also shared some common traits, especially in their joint emphasis on preparing graduates to educate the next generation of social workers.

Accessibility versus student support

One of the most consistent findings of the survey involved the significant differences in the ways that PhD and DSW programs facilitated their students’ access to and successful completion of a doctoral degree. In general, DSW programs were more likely to include flexible options such as online instruction and part-time enrollment that could enable doctoral students to continue full-time employment or parenting and caregiving responsibilities while pursuing a doctoral degree. In fact, program directors indicated that a substantial number of DSW students were currently employed during their doctoral program and many were not seeking new positions upon graduation. This suggests the possibility of professional development as an important motivation for doctoral education and warrants further research inquiry.

In contrast to DSW programs’ accessibility, PhD programs provided more financial and material support to their students alongside a more frequent expectation of full-time enrollment. Findings showed that PhD programs were significantly more likely to provide support in the areas of tuition support, stipends, health insurance, assistantship positions, conference travel, and job search support. Financial and tuition support may help ameliorate the potential student debt burden of doctoral education (Begun & Carter, Citation2017), but comprehensive funding packages likely limit the total size that is feasible for doctoral programs. As seen in the data, PhD programs were more likely to offer guaranteed years of funding for students, and PhD directors reported means of 31.28 enrolled students and 4.32 graduating students each year, whereas the DSW directors reported means of 101.40 enrolled students and 18.44 graduating students.

Both accessibility and student support are also key to increasing the diversity and inclusiveness of social work doctoral education. For example, DSW programs with greater flexibility and larger enrollment can increase access to doctoral education to students who would not otherwise have access, including students of color, lower-income students, and students with caregiving responsibilities who may not be able to “pause” their adult life or move for full-time, in-person doctoral education. Although the survey’s demographic findings are tentative and limited by missing data, there is some suggestion in the findings that DSW programs may include a higher proportion of Black/African American students, which is consistent with the findings of the CSWE 2019 Statistics on Social Work Education in the United States (CSWE, Citation2020b). While increased access is certainly important for promoting diversity in doctoral social work education, the reduced financial and mentoring support associated with large, online, and part-time programs pose concerns as well. In particular, remote and part-time learning may not facilitate the relational mentoring that can help address marginalization and increase the diversity of social work academia (Chin et al., Citation2018; Ghose et al., Citation2018). Further, the distinctions between the goals and foci of the programs should ideally be driving the decision for students to choose between a DSW or a PhD, rather than the flexibility of the program or the financial and mentoring supports offered. Thus, doctoral directors of both types of programs should evaluate both the accessibility of their programs and the supports offered to their students to be sure their programs are equitable for diverse students.

Research rigor and practice expertise

In most areas, PhD and DSW programs were organized according to their distinct goals and emphases. PhD directors generally depicted an overarching emphasis on contributing to the profession through research, which they identified as their students’ top goal, a key focus of their doctoral curriculum, and the top factor for a successful job search. Compared to DSW programs, PhD programs included more courses on quantitative methods and statistical skills and required the completion of candidacy or qualifying examinations and dissertations to demonstrate traditional research-oriented skills. In contrast, DSW directors depicted greater emphasis on advancing clinical expertise and leadership in nonacademic settings. DSW directors rated advancing social work practice as their students’ top goal and rated practice experience as the top factor for a successful job search. Compared to PhD programs, DSW programs included more courses on micro and mezzo practice and leadership development and included graduation requirements such as portfolios or capstone projects to demonstrate practice skills. Notably, there was no difference in the number of courses offered by PhD or DSW programs on qualitative research methods, pedagogy, or macro practice.

The apparent differences in career paths between PhD and DSW graduates indicates opportunities to unite research and practice and address the research–practice gap. According to directors’ responses, PhD graduates are more likely to pursue tenure-track faculty positions at research-oriented institutions, with DSW graduates more likely to pursue nonacademic administrative positions and clinical practice. Thus, DSW graduates may be well-suited to bring the research-informed knowledge of the doctoral community to agencies and clients through administrative and clinical positions. They may also promote practice-based research as practitioner-scholars working in direct practice. Further, they are also well-positioned to use their advanced practice knowledge and skills to assist PhD researchers to develop meaningful, practice-relevant research questions and methods of dissemination of research findings to the practice world. In their roles as academicians and researchers, PhD graduates are well-positioned to advance the science of the field and collaborate in interdisciplinary research with other disciplines. However, doctoral program directors should also consider how to promote collaboration within the discipline, such that the practice expertise of DSW graduates and research skills of PhD graduates can join together to produce rigorous and relevant research with tangible effects on practice and policy.

Job search support and the academic job market

Finally, the findings showed differences in the job search process between PhD and DSW graduates, with the PhD programs in this study providing more extensive job search support than DSW programs. The survey findings showed that PhD and DSW graduates in this study were often seeking different types of positions, with PhD graduates pursuing tenure-track positions, postdoctoral fellowships, and more research-oriented positions, and DSW graduates more often pursuing nonacademic administrative positions or clinical practice. However, both PhD and DSW graduates were seeking positions at teaching-oriented institutions, and PhD graduates appeared to have an advantage in obtaining these positions among this sample. PhD directors generally emphasized the importance of research productivity and a focused research agenda for a successful academic job search and rated lower importance for practice experience, which reflects the literature suggesting a trend away from practice experience among tenure-track faculty (Anastas, Citation2015; Johnson & Munch, Citation2010). In contrast, DSW directors rated practice experience as the most important factor for an academic job search, and some scholars have suggested that DSW graduates can help fill the need for faculty with practice experience in BSW and MSW programs (Thyer, Citation2015). Both PhD and DSW programs in this study reported an emphasis on teaching skills and reported that their students were motivated to educate future social workers and develop leaders in academic settings. However, the increasing number of doctoral graduates, primarily DSW graduates, in recent years could potentially further exacerbate the tightening academic job market in social work (Lightfoot & Zheng, Citation2020). Another potential issue relates to the fact that DSW programs could be more attractive to experienced social work professionals with practice expertise who aspire more to teaching-oriented universities that might not offer tenure-track positions, which could further exacerbate the divide between research and practice as well as the recognition afforded to faculty with practice expertise.

Limitations

Limitations of the survey need to be acknowledged. First, the data were entirely based on doctoral program directors’ self-report, including their perception of students’ educational goals, aspirations for jobs, and job placement outcomes. As such, there might be recall errors, perception biases, or social desirability bias. Second, the survey did not capture information for all doctoral programs. While the response rate for both PhD (69%) and DSW program directors (88%) was satisfactory, directors did not uniformly provide answers for all questions, with several sections of the survey having one-third missing responses or higher. As the survey took place in the early months of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, directors may have experienced greater time challenges to collect data for some questions. Overall, the survey received more responses on questions regarding program characteristics, support and resources provided to students, and curriculum focus and design, and fewer responses on students’ demographics and job search aspirations and outcomes. For numerical questions regarding student enrollment, graduates, and job seekers, the data were flawed by missing data and a low number of responses, and the presence of very large outliers, particularly among DSW programs. Findings will need to be interpreted with caution, although the triangulation of data of this survey with the CSWE 2019 Annual Survey of Social Work Programs (CSWE, Citation2020b) affirmed some important demographic findings, including the higher proportion of Black/African American students in DSW programs than PhD programs. Finally, this survey did not collect demographic data about the program directors themselves, program completion rates, or information about students’ age or prior social work experience. With the understanding that CSWE usually collects these data in their annual surveys, the research team decided not to duplicate effort in an attempt to streamline the survey items, although this is a limitation of the current study.

Conclusion

The changing landscape of doctoral education indicates the need to understand the overall landscape as well as the unique and potentially complementary contributions of PhD and DSW programs. Although they share clear similarities, PhD and DSW programs are also distinct in their intended contributions to social work. PhD programs exhibit a clear focus on building the research and leadership capacities of doctoral students, whereas DSW programs focus more on preparing students to contribute in the areas of clinical expertise and nonacademic administration. While these complementary foci open opportunities for collaboration to address the research–practice gap, attention is needed to ensure a sustainable and equitable future for doctoral social work education. In particular, differences in program structure and enrollment options, as well as program size, influence a balance of accessibility and student support that warrants further attention from a social justice and diversity and inclusion perspective. Further, the expansion of doctoral programs and recent growth of DSW programs warrants strategic assessment to ensure the sustainable development of doctoral education, particularly with regard to the competitiveness of the academic job market. We hope the findings of the 2020 GADE Director Survey will generate useful dialog among doctoral directors and the social work community to further advance the direction of doctoral education in a way that is consistent with the Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work (Citation2016) mission to “promote rigor in doctoral education in social work, focusing on preparing scholars, researchers, and educators who function as stewards of the discipline” (p. 1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mo Yee Lee

Mo Yee Lee is Professor and PhD Program Director at College of Social Work, Ohio State University.

Ray Eads

Ray Eads is Assistant Professor at Jane Addams College of Social Work, University of Illinois Chicago.

Elizabeth Lightfoot

Elizabeth Lightfoot is Director and Foundation Professor at School of Social Work, Arizona State University.

Michael C. LaSala

Michael C. LaSala is Associate Professor and Director of the DSW Program at School of Social Work, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

Cynthia Franklin

Cynthia Franklin is Professor at Steve Hicks School of Social Work, The University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Acquavita, S. P., & Tice, C. J. (2015). Social work doctoral education in the United States: Examining the past, preparing for the future. Social Work Education, 34(7), 846–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1053448

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2015). The doctor of nursing practice: Current issues and clarifying recommendations. Report from the Task Force on the implementation of the DNP.

- Anastas, J. W. (2013). Practice doctorates in social work how do they fit with our practice and research missions? Setting the stage. In Social Work Policy Institute (Ed.), Advanced practice doctorates: What do they mean for social work practice, research, and education (p. 3). NASW.

- Anastas, J. W. (2015). Clinical social work, science, and doctoral education: Schisms or synergy? Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0534-5

- Barsky, A., Green, D., & Ayayo, M. (2014). Hiring priorities for BSW/MSW programs in the United States: Informing doctoral programs about current needs. Journal of Social Work, 14(1), 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017313476772

- Bednash, G. (2013). Transformation of advanced practice nursing education: Moving to the professional doctorate. In Social Work Policy Institute (Ed.), Advanced practice doctorates: What do they mean for social work practice, research, and education (pp. 7–8). NASW.

- Begun, A. L., & Carter, J. R. (2017). Career implications of doctoral social work student debt load. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(2), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1243500

- Beltran, R., Lightfoot, E., & Sweeny, M. (2020). The GADE Guide: A program guide to doctoral study in social work. The Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work.

- Bolte, G. L. (1971). Current trends in doctoral programs in schools of social work in the United States and Canada. In L. C. Deasy (Ed.), Doctoral students look at social work education (pp. 109–126). Council on Social Work Education.

- Borgogna, N. C., Smith, T., Berry, A. T., & McDermott, R. C. (2021). An evaluation of the mental health, financial stress, and anticipated debt-at-graduation across clinical and counseling PhD and PsyD students. Teaching of Psychology, 48(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628320980856

- Brekke, J. (2014). A science of social work, and social work as an integrative scientific discipline: Have we gone too far, or not far enough? Research on Social Work Practice, 24(5), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731513511994

- Chin, M., Hawkins, J., Krings, A., Peguero-Spencer, C., & Gutiérrez, L. (2018). Investigating diversity in social work doctoral education in the United States. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(4), 762–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1503127

- Cnaan, R. A. (2018). Social work doctoral education in transition: The Islandwood papers of the roundtable on social work doctoral education. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(3), 221–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731517722636

- Council on Social Work Education. (2020a). Accreditation standards for professional practice doctoral programs in social work.

- Council on Social Work Education. (2020b). 2019 Statistics on social work education in the United States.

- Council on Social Work Education/ Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work. (2021). CSWE/GADE Report on the current landscape of doctoral education in social work.

- Crow, R. T., & Kindelsperger, K. W. (1975). The PhD or the DSW? Journal of Education for Social Work, 11(3), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220612.1975.10778699

- Diaz, M. (2015). The “new” DSW is here: Supporting degree completion and student success. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 35(1–2), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2014.972013

- Dobrowolska, B., Chruściel, P., Pilewska-Kozak, A., Mianowana, V., Monist, M., & Palese, A. (2021). Doctoral programmes in the nursing discipline: A scoping review. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 228. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00753-6

- Floersch, J. (2013). What can we learn from current DSW programs? In Social Work Policy Institute, Advanced practice doctorates: What do they mean for social work practice, research, and education (pp. 11–12). NASW.

- Ghose, T., Ali, S., & Keo-Meier, B. (2018). Diversity in social work doctoral programs: Mapping the road ahead. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(3), 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731517710725

- Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work. (2016). Strategic plan (pp. 1–3). http://www.gadephd.org/About-Us/GADE-Strategic-Plan

- Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work. (2019). 2019 Year in Review - President’s Letter (pp. 1–2). http://www.gadephd.org/Portals/0/GADEdocuments/General/2019GADENewsletter.pdf?ver=2020-04-14-134939-840

- Guerrero, E. G., Moore, H., & Pitt-Catsouphes, M. (2018). A scientific framework for social work doctoral education in the 21st century. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(3), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731517709077

- Hage, S. M., Loughran, M. J., Renninger, S. M., & Cyranowski, J. M. (2020). PsyD programs in counseling psychology: Current status and future directions. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(5), 716–737. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000020916787

- Harvison, N. (2013). What can we learn from occupational therapy. In Social Work Policy Institute (Ed.), Advanced practice doctorates: What do they mean for social work practice, research, and education (pp. 8–9). NASW.

- Howard, T. (2016). PhD versus DSW: A critique of trends in social work doctoral education. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(S1), S148–S153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1174647

- Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. (2018). The Carnegie classification of institutions of higher education, 2018 edition.

- Johnson, Y. M., & Munch, S. (2010). Faculty with practice experience: The new dinosaurs in the social work academy? Journal of Social Work Education, 46(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2010.200800050

- Jorgensen, L. (1985). Group for the advancement of doctoral education in social work program guide.

- Kurzman, P. A. (2015). The evolution of doctoral social work education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 35(1–2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2015.1007832

- Lightfoot, E., & Beltran, R. (2018). The Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work (GADE). In C. Franklin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social work. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1281

- Lightfoot, E., & Zheng, M. (2020). Research note—A snapshot of the tightening academic job market for social work doctoral students. Journal of Social Work Education, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2020.1817826

- Social Work Policy Institute. (2013). Advanced practice doctorates: What do they mean for social work practice, research, and education. NASW.

- Sowers, K. (2013). Practice doctorates in social work: Are practice doctorates the next big thing in social work? In Social Work Policy Institute (Ed.), Advanced practice doctorates: What do they mean for social work practice, research, and education (pp. 3–4). NASW.

- Thyer, B. A. (2015). The DSW: From skeptic to convert. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0551-4

- Trautman, D. E., Idzik, S., Hammersla, M., & Rosseter, R. (2018). Advancing scholarship through translational research: The role of PhD and DNP prepared nurses. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 23(2), Manuscript 2. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No02Man02

- Uehara, E. S., Barth, R. P., Coffey, D., Padilla, Y., & McClain, A. (2017). An introduction to the special section on Grand Challenges for Social Work. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 8(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1086/690563