ABSTRACT

The rapid increase of negotiated out of court settlements in corporate crime cases has attracted significant academic attention. How the terms of settlements are constructed, however, remains under-studied. To address this gap, the paper observes that the terms of settlements often include a basket of allegations widely spread across time and geography. The paper conceptualises this as a form of ‘bundling’. The paper empirically explores the unique dynamics of corporate bribery cases that enable prosecutors to engage in bundling, and deconstructs bundling into two typologies (allegation bundling and enforcement bundling). From this perspective, this paper analyses official enforcement documentation relating to international bribery cases, supplemented with data from interviews with key informants who have experience of settlement negotiations in the US, the UK, and other countries. The analysis reveals that bundling provides efficiencies when resolving corporate crime cases, offers discounts to corporate defenders, and incentivizes coordinated multilateral enforcement. The practice of bundling allegations and enforcers confirms the character of negotiated settlements as a symbolic criminal law tool designed to reform the accused corporation through negotiation, persuasion and compliance.

Introduction

The global spread of negotiated settlements in corporate crime cases has attracted significant academic attention. Negotiated settlements involve cooperation and agreement between enforcement authorities and alleged corporate offenders (Søreide and Makinwa Citation2020, p. 5). When negotiating the terms of settlements, enforcement authorities leverage the threat of prosecution and possible conviction as their bargaining power (Arlen Citation2016). To resolve their case out-of-court, the corporation usually needs to provide details of violations following internal investigations and self-report to enforcement authorities, or at least closely cooperate with enforcement authorities. While cooperative in its nature, the process of negotiating terms of settlements involves complex interactions and backdoor deals (Garret Citation2016, p. 9). Due to a lack of empirical research, the question of how these deals are constructed remains under-studied.

This paper offers new empirical material into the processes of negotiation that take place between enforcement authorities and corporate offenders. In doing so, the paper offers a new conceptualisation of the constitution of settlement agreements. Firstly, the paper observes that the terms of settlements often include a basket of allegations widely spread across time and geography. The paper conceptualises this as a form of ‘allegation bundling’. Secondly, the paper observes that settlements bring together a set of distinct enforcement authorities with overlapping jurisdiction over a core set of allegations. The paper conceptualises this as a form of ‘enforcement bundling’. Bundling of allegations and enforcers, as argued in this paper, has enabled comprehensive resolutions with organizations that engaged in major corruption schemes. The analysis reveals that bundling provides efficiencies when resolving corporate crime cases, offers discounts to corporate defenders, and incentivizes coordinated multilateral enforcement.

The foreign anti-bribery action, that the UK Serious Fraud Office (SFO), the US Department of Justice (DOJ), the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and Brazilian authorities settled with Rolls-Royce presents a paradigmatic bundle. The Rolls-Royce bundle covers multiple bribes in twelve countries in which bribery events were widely separated by a quarter of a century (Serious Fraud Office Citation2017). In another typical bundle, Walmart, the enforcers announced that Walmart ‘valued international growth and cost-cutting over compliance’ and it ‘failed to take red flags seriously and delayed the implementation of appropriate internal accounting controls’ (SEC Citation2019). The Walmart bundle encompassed conduct that took place across three continents and spanned more than a decade.

The bundling of disparate allegations has been widely used in corporate crime settlements with ‘criminogenic’ organizations (see Braithwaite Citation1985, p. 93). While it is widely accepted that corporate crime is largely committed by legitimate organisations (Van Erp and Huisman Citation2017), some legitimate organisations are more ‘criminogenic’ than other organisations (Huisman Citation2016). The bundled settlements with Rolls-Royce and Walmart suggest the presence of ‘endemic corruption’ within more criminogenic organizations as these cases involve multiple bribes at multiple times in multiple places (Galtung Citation1998). The bundling of allegations, as argued in this paper, has enabled comprehensive resolutions with organizations that engaged in major corruption schemes. To date criminologists, however, have ignored the bundling that occurs in the resolution of serious corporate crime cases.

In order to address this vacuum, the present research posed two questions. How does the practice of bundling function in the context of corporate crime? What implications does bundling have for the global policing of corporations? In order to answer these questions, the paper first sets bundling in the context of criminological literature. The paper then analyses foreign anti-bribery enforcement actions and provides a typology of bundling.Footnote1 The paper will end by examining some of the implications of bundling, including the investigation and sanctioning of serious corporate crime as well as enforcement cooperation and coordination. This final section is based on the analysis of 13 semi-structured interviews that were conducted with defence lawyers, former prosecutors, and other practitioners.Footnote2 Firstly, however, the methods for this research will be outlined.

Methods

Given the aim of this paper is explorative in nature, a qualitative exploratory design was used (Guest et al. Citation2012, pp. 7–8). This allows for a flexible approach in order to clarify complex relationships between enforcement authorities and corporate defenders (Boeije Citation2010, p. 13). To undertake the research, two techniques were pursued: desk-based research and semi-structured interviews.

The research started with an observation that foreign anti-bribery settlements sometimes include schemes widely separated by space and time as well as that settlements include more than one enforcement authority. With this in mind, the desk-research included the analysis of existing literature and foreign bribery settlements. This analysis led to the construction of a typology of anti-bribery bundling.

The findings of the desk research informed the construction of an interview schedule that focused on both more general questions on settlement negotiations as well as specific questions related to allegation bundling and enforcement bundling. The research includes 13 semi-structured interviews with practitioners who have experience with policing international bribery and negotiating settlements. All interviewees held senior positions in their organizations. Eleven had direct experience with negotiating settlements and two had indirect experience by conducting internal investigations on behalf of corporations which subsequently led to settlements. Three interviewees also had experience of negotiating settlements on behalf of the US government and one on behalf of the UK government. There was no intention that the sample frame would be representative of the population of practitioners with the experience in negotiating corporate settlements. Non-probability sampling was used (Kalof et al. Citation2008, p. 44), whilst ensuring a sensible breadth of perspectives from prosecutors and corporate defendants recruited through professional networks in the US and the UK. Interview data were collected by conducting in-person interviews in London, New York, Washington, and online. All the data were anonymized and coded to identify emergent themes.

Policing transnational corporate crime and out-of-court resolutions

Transnational corporate crime is a hard nut to crack (Sutherland Citation1949, Fisse and Braithwaite Citation1993, Levi Citation2008). International bribery, for example, not only includes bribers and bribed parties, but frequently also third-party facilitators that are controlled by or act on behalf of the main parties, and is further complicated by transnational communication channels, payment systems and in-person meetings (Hock Citation2020). While law enforcement has become the focus of recent discussions, governments have traditionally preferred non-criminal response to corporate crimes (Sutherland Citation1949, Lord and Levi Citation2015). Given the complexity of transnational corporate cases, costs of prosecution, and potential negative externalities associated with corporate prosecutions, this aversion to criminal prosecution remains (Stevenson and Wagoner Citation2011, Lord and Levi Citation2015, Garret Citation2016).

Traditional criminal law enforcement has been to a large extent overshadowed by self-regulatory and hybrid responses to transnational corporate crime (Lord Citation2014b, Rubin Citation2016, Button Citation2019). An important part of this process is the increase of negotiated settlements in the US and other countries, an issue frequently discussed by academics (Ryder and Pasculli Citation2020, Søreide and Makinwa Citation2020) as well as policy-makers (House of Lords Citation2019). Various negotiated settlement processes have recently been adopted in countries such as the UK, Canada, Ireland, and France (Ryder Citation2018, King and Lord Citation2018). In the UK, for example, they take a form of DPA that needs to be approved by a judge (Grasso Citation2016).

These alternative tools to classic criminal court proceedings has been criticised by many. In the US context, scholars argue that negotiations based on the FCPA and other statutes can be unfair because enforcement authorities have too much power in presenting, negotiating, and implementing settlements (Reilly Citation2014). More generally, scholars indicate that negotiated settlements are not consistent with the rule of law principles (Arlen Citation2016). And Wilborn (Citation2013) further suggests that, given the wide prosecutorial discretion associated with negotiated settlements, prosecutors may abuse their power. In the UK context, critics argue that DPAs do not overcome the low rates of prosecuted individuals (Button et al. Citation2018) and their deterrence effect is insufficient to fully substitute criminal corporate prosecutions (see King and Lord Citation2018, Hawley et al. Citation2020). Some criminologists view the lack of full criminal prosecution of corporate crime as a major problem (Tombs and Whyte Citation2011, Citation2019).

The ability of corporations to avoid criminal liability is part of a more general shift in the way states interact with corporations. This shift goes beyond a traditional binary distinction between compliance and deterrence (Reiss Citation1984, Braithwaite and Fisse Citation1985). Braithwaite (Citation2002) grasped this complexity by introducing the concept of responsive regulation, broadening the palette of restorative justice approaches to corporate crime. Policing ‘criminogenic’ organizations indeed presents a normative challenge. While the increased complexity of corporate crime places substantial pressure on national enforcement authorities to be effective in policing corporate crime (Lord Citation2014a), criminal justice systems also need to find the right balance between punishment orientation and reform orientation. The use of what Hess and Ford (Citation2007) call ‘reform undertakings’ can help to find such balance. For example, the authors argue that retaining an independent monitor is crucial when addressing deep-seated corporate cultural pathologies (see also Ford and Hess Citation2008).

The concept of bundling presents a modest addition to this discussion as it invites a re-think of assumptions about the dynamics of negotiated settlements and how large cases of economic crime are investigated and prosecuted. While the practice of bundling has been ignored in criminology, bundling has been discussed in a variety of academic fields. In political science, the concept of bundling is used to consider the choice-sets facing voters and political representatives (Arnold Citation1990). Economists debate whether bundling operates as a discounting strategy, benefiting consumers (Posner Citation2007), or an anti-competitive practice through which a monopolist extends its market power (Elhauge Citation2009). In the legal literature, scholars have focused on bundling in government procurement and public-private partnerships (Iossa and Martimort Citation2012). Corporate law scholars have noted that firms may bundle pro-management terms with pro-shareholder items into corporate policies and contractual arrangements in order to secure shareholder approval (Bebchuk and Kamar Citation2010). In criminal law, bundling has been discussed in the context of appropriate sentence increases of uncharged crimes (Ross Citation2002, pp. 983–985). This paper introduces the practice of bundling in the corporate crime scholarship.

A typology of anti-bribery bundling

This section provides a typology of bundling, dividing the paradigmatic forms of bundling into two basic types: Allegation Bundling and Enforcement Bundling. The section also illustrates how bundling is constructed and what legal institutions plays the role in constructing bundles.

Bundling allegations

Bundling allegations explained

In the enforcement of foreign anti-bribery laws, allegation bundling involves the packaging of disparate allegations into a single resolution. One of the core attributes of allegation bundling is that it enables enforcement authorities to combine weak claims – those unlikely to lead to conviction – with stronger claims – those with convincing evidence and substantive settlement value.Footnote3 As will be illustrated in this section, weak claims are also associated with a dubious classification of underlying conduct and legal obstacles such as statutes of limitations and jurisdictional issues.

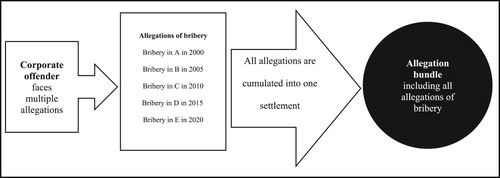

The allegation bundling, as illustrated in , indicates that the corporate offender engaged in five bribery schemes. These schemes are widely separated by space and time. For example, a bribery scheme in Country A took part in 2000 and a bribery scheme in Country E took place in 2020. The corporate offender subsequently faces allegations of endemic corruption in, for example, the US and concludes a settlement bundle with the US enforcement authorities.

The Alstom case is a paradigmatic example of how enforcement authorities bundle relatively weak allegations with relatively strong allegations in order to claim endemic corruption. The breadth of the Alstom case was acknowledged by enforcement authorities at the time, who asserted that the many offences, widely separated by space and time, were evidence of a systemic problem at the company (US Department of Justice Citation2014a). The common element to all allegations within the bundle was the identity of the corporate offender.

In Alstom, the DOJ had a strong case to justify their theory of ‘endemic corruption’ as the case spanned over ten years (US Department of Justice Citation2014a). Alstom S.A. and its subsidiaries paid bribes through to government officials in countries such as Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the Bahamas and Taiwan to win high value contracts from state-controlled power companies. In Saudi Arabia, for example, the value of the first two stages of the Shoaiba project was worth approximately $3 billion (US Department of Justice Citation2014a, p. B-20). The prosecution case would have been substantially weaker had it rested solely on this allegation as Alstom could have mounted a strong jurisdictional defence.

The diversity of allegations bundled into the Alstom resolution meant that some allegations were relatively weak and others strong. For example, Alstom’s Swiss subsidiary (Alstom Prom) allegedly bribed various government officials from 2000 to 2011 while being an agent of a stock issuer (Alstom S.A.). The DOJ charged the subsidiary in 2014. This could present an opportunity for the defendant to argue that the US authorities did not have jurisdiction because Alstom delisted from the NYSE in 2004 (US Department of Justice Citation2014a, p. B-2).

Furthermore, the US authorities acknowledged weaknesses of their allegations in other bundles. Consider the $398 million settlement with Total the French oil and gas company, in which the DOJ stated explicitly that the resolution was influenced by its struggle to overcome evidentiary challenges: ‘Among the facts considered were the following: […] (b) the evidentiary challenges presented to both parties by this matter, in which most of the underlying conduct occurred in the 1990s and early 2000s’ (US Department of Justice Citation2013, p. 3). Although weak allegations could be defended if brought in isolation, when faced with the alternative prospect of multiple actions, corporations such as Alstom and Total preferred to settle their cases.

Having introduced allegation bundling, the more technical question of how bundling works in law enforcement practice will now be addressed. Two examples are provided: the use of accountancy laws and constructing conspiracies.Footnote4

Conspiracy and allegations bundling

The so-called conspiracy principle allows the US enforcement authorities to hold one person liable for the conduct of another person. Both individuals and corporations who are intentionally helping, initiating, or authorising foreign bribery shall be liable for participating in the violations of foreign anti-bribery laws. This allows the US enforcement authorities to overcome a number of jurisdictional problems they may face during investigation. The US Resource Guide to the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (DOJ and SEC Citation2012, p. 12) indicates that:

A foreign company or individual may be held liable […] for conspiring to violate the FCPA, even if the foreign company or individual did not take any act in furtherance of the corrupt payment while in the territory of the United States. In conspiracy cases, the United States generally has jurisdiction over all the conspirators where at least one conspirator is an issuer, domestic concern, or commits a reasonably foreseeable overt act within the United States.

Books and records and allegation bundling

The second tool is the accounting provisions of the FCPA requiring corporations to keep accurate books and records and internal controls.Footnote5 These provisions allow the US enforcement authorities to sanction stock issuers (i.e. public companies) for failure to maintain accurate accounts or records, or for falsifying accounts or records. Moreover, the US enforcement authorities can sanction issuers for failing to maintain a system of adequate internal controls.

These accounting provisions are a powerful enforcement tool because most corporations that pay bribes also compromise their books rather than accurately account for bribery. Furthermore, bribery and corruption are also the results of weak internal controls (DOJ and SEC Citation2012, p. 40). The US enforcement authorities use the accounting provisions in schemes in which evidence of bribery is difficult to establish (Golden Citation2019). For example, Walmart was not charged with bribery; the company was accused of failing to adequately mitigate bribery risks and its subsidiaries paid third parties in Brazil, Mexico, India and China without reasonable assurances that payments were not bribes (SEC Citation2019). The common denominator of these FCPA violations was the accused corporate offender. The prosecution’s solution featured the bundling of bribery schemes separated by time and space.

Allegation bundling beyond the US enforcement

While not all nations have the same jurisdictional and economic capacity to create allegation bundles, a number of countries have started adopting laws that allow them to participate in the US-led approach, and create their own allegation bundles. For example, Section 7 of the UK Bribery Act that sanctions the failure to prevent bribery and the French Sapin II (see Grasso Citation2016, King and Lord Citation2020).

Although the adoption of international treaties such as the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention (OECD Citation2011) has led to the convergence of national foreign anti-bribery laws and regulations, there are still significant differences between countries. For example, unlike US law, UK law provides more stringent conditions for concluding a DPA. Most importantly, the UK judge has the authority and the responsibility to engage in a review of the terms, conditions and requirements of the proposed settlement and ultimately must approve or decline a DPA. Under Section 7 of the Bribery Act, the court must assess whether an agreement is likely to be in the interest of justice, and whether the proposed terms of the DPA are fair, reasonable, and proportionate (Hock Citation2020, pp. 94–94).

Due to the differences between national approaches to foreign anti-bribery enforcement, the dynamics of negotiations assumedly differ. Despite these differences, settlements with corporations such as Rolls-Royce, Airbus, Odebrecht, or Petrobras show that allegation bundling has been present in cases resolved by non-US enforcement authorities.

Bundling enforcers

Bundling enforcers explained

A different type of bundling occurs when the resolution brings together a set of distinct enforcement authorities with overlapping jurisdiction over a core set of allegations. Prosecuting agencies bundle themselves together in order to leverage their enforcement power and their investigative and prosecutorial resources. Alternatively, corporations may facilitate the bundling of enforcers in order to achieve a broader resolution that minimises costs associated with resolving allegations of bribery in multiple jurisdictions.

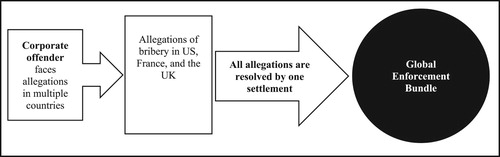

above illustrates the bundling of enforcers. The Corporate Offender faces bribery allegations in three countries – US, France, and the UK. As these three countries cooperate and coordinate their enforcement actions, the Corporate Offender is able to conclude one coordinated settlement (global enforcement bundle) with all three enforcement authorities.

A global enforcement bundle was concluded, for example, in Rolls-Royce. In 2017, UK based Rolls-Royce plc agreed to pay more than $800 million to resolve multiple bribery claims with enforcement authorities in the UK, the US, and Brazil. The underlying allegations covered over two decades of misconduct (1989–2013) and 12 countries (Thailand, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Angola, Iraq, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nigeria, and Russia). Rolls-Royce thus bundles both allegations and enforcers.

The bundling of enforcers in Rolls-Royce was based on an agreement between the US, the UK and Brazilian enforcement authorities to split the bundle (Hock Citation2020, pp. 182–183). The DOJ indicated that ‘this successful parallel investigation is a tremendous example of the central importance of working cooperatively alongside our international partners to achieve a fair and meaningful resolution’ (US Department of Justice Citation2017). The Brazilian authorities covered bribery related to Petrobras, a Brazilian state-owned petroleum corporation, for which Rolls-Royce was fined $25.6 million. A second part of the bundle relating to corrupt schemes in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nigeria, Russia, and Thailand was covered by the UK Serious Fraud Office and resulted in a fine of £497 million. The US enforcement element yielded $170 million for a third part of the bundle covering corruption in Thailand, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Angola and Iraq.

Bundling enforcers and cooperation and coordination mechanisms

Global enforcement bundles have emerged due to an increase in the coordination of national enforcement authorities. This coordination is facilitated by mechanisms that support cooperation and help resolve potential jurisdiction conflicts (Brewster and Buell Citation2017).

The foreign bribery scheme settled by the French, UK, and US authorities in the Airbus case shows how these countries coordinate their enforcement (Serious Fraud Office Citation2020) to construct a global enforcement bundle. Airbus is a massive case involving bribes in multiple jurisdictions relating to civil and military aircraft. The key issue in this case was that the US authorities recognised ‘the strength of France’s and the United Kingdom’s interests over the Company’s corruption related conduct, as well as the compelling equities of France and the United Kingdom to vindicate their respective interest as those countries deem appropriate […]’ (US Department of Justice Citation2020). In other words, the US authorities applied the doctrine of international comity in so far as they took into account the interests of other countries when asserting their sovereign power (see generally Guzman Citation2011).

However, the construction of enforcement bundles should not be taken for granted as all parties have large discretion whether to cooperate and how to coordinate their actions. In a number enforcement schemes, corporations such as SBM Offshore were sanctioned in multiple jurisdictions for similar illicit conduct (Hock Citation2020, pp. 185–187). While large enforcement conflicts are rare, enforcement bundling should not be considered as the default response. While in some legal fields, such as anti-trust, countries have concluded international agreements to facilitate cooperation and coordination in transnational cases, no such agreement exists in the area of foreign bribery. Enforcement authorities are left with soft arrangements such as a consultation procedure envisaged by Article 4(3) of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention (OECD Citation2011). The OECD consultation procedure, however, only obliges countries to consult. Countries are not obliged to decline prosecution if another signatory has more appropriate jurisdiction.

In the absence of a strong cooperation and coordination mechanism, trust between national enforcement authorities is vital. France and the UK joined forces in the Airbus case to establish a joint investigation team (JIT) which led to France collecting $2.29 billion and the UK collecting $1.09 billion. The US enforcement yielded ‘only’ $527 million (US Department of Justice Citation2020). This illustrates how the participation of more nations in enforcement partnerships extends the international network of enforcers and enables more powerful enforcement in international bribery cases.

However, the presence of allegation and enforcement bundling in settlement negotiations complicates global policing of corporate economic crime and policymakers and analysts alike should consider implications bundling presents to the criminal justice system. These are discussed in the following section.

Implications of anti-bribery bundling

Having discussed the what and the how of bundling in the context of foreign anti-bribery enforcement actions, the paper now addresses why bundling matters. The interviews suggest three sets of issues that further studies should take into account. Firstly, the section examines concerns about the coercive weight of corporate prosecutions and the rule of law implications underlying bundling. Secondly, the paper suggests that allegation bundling is a form of discounting that favours corporations. Thirdly, the section examines the trade-offs and deals made in the pursuit of ‘global resolution’ through enforcement bundling.

The coercive power of prosecution and the rule of law

Allegation bundling enables enforcement authorities to combine weak claims – those unlikely to lead to conviction – with stronger claims – those with convincing evidence and substantive settlement value. The rational economic choice for corporations is to agree to bundling. Settlement bundles offer lower sanctions, avoid the risks and costs associated with multiple cases, are efficient, clean the slate and provide certainty. However, this incentive to resolve cases out-of-court gives national enforcement authorities important leverage: they can defer prosecution in order to hold the defendant corporation to account should it fail to comply with the terms of the agreement. This leverage may be subject to abuse.

Insofar as foreign bribery cases are negotiated in the settlement of the law, using bundling as a technique to increase the enforcement leverage effectively changes the law. Stuntz (Citation2004, p. 2548) argues that relevant laws in these situations represent a mere menu, ‘a list of threats prosecutors may use’, such as debarment and large fines. The menu, however, does not indicate ‘what options are exercised or what threats are used’. In this context, allegation bundling amplifies numerous issues that critiques of settlements raise (Willborn Citation2013, Reilly Citation2014, Arlen Citation2016, King and Lord Citation2018, Hawley et al. Citation2020).

Allegation bundles may be considered as the product of an unfair criminal justice system. For example, one may argue that the ever-present threat of collateral consequences of prosecution weights the balance of power significantly in favour of enforcement authorities (Arlen Citation2016). Interviewees indeed indicated that corporations are under significant pressure to avoid a court proceeding

You start with the emotional reaction, oh, this bad company, they did something bad, we’re going to show them, and then you look at what happened with Andersen, there were 20,000 employees, if 500 of those employees were engaged in misconduct, that would be an unusual number. And the end result was you destroy the company, you put 20,000 people out of work, you screwed up a part of the economy because now instead of there being five competitors there’s only four [Participant 5].

It is therefore crucial for a corporation to avoid criminal prosecution. This existential motivation could be leveraged by enforcement authorities to apply the criminogenic theory of endemic corruption. The authorities could accuse a corporation of systematic bribery, and threaten it with highly disruptive investigations and a drawn-out prosecution that would lead to its demise. Interviews, however, do not support such explicit abuse of prosecutorial power. When discussing how US enforcement authorities include additional bribery schemes into a settlement, a US defence lawyer indicated that there are limits to what enforcement authorities can take forward during negotiations:

Just because they ask you doesn’t mean you have to say. And that’s why I loved that moment where they said, was there a US person? No? Passport holder? No. US money? No. Green card holder? I was like laughing inside. I was like, you don’t have it. And if we just put it in [volunteered incriminating evidence] … . they would not be doing their job [Participant 4].

What frequently is going on is the result of a give and take. There are companies who are saying, look. I can’t afford to have the holding company found guilty of bribery because then I’ve got debarment everywhere, and so let’s take some – and this is frequently done by the Americans [prosecutors] who say, okay, we get it. […] [Participant 1]

It is to my knowledge uniformly the case that major companies ultimately have decided that it is in their business interest to resolve the case with the Justice Department by paying a very, very heavy criminal monetary penalty; and agreeing to co-operate with the federal government. [Participant 9]

The government made a terrible mistake, and if you get them off the record, they’ll tell you they made a terrible mistake in that case. [Participant 6]

To summarise, the Andersen case is symbolic of what can go awry in confrontational corporate prosecutions. In demonstrating the resolve of the prosecutors and the immense damage it can cause, the case paved the way for rationally negotiated justice settlements that limit collateral damage. In the US and increasingly in other parts of the world, parties take active steps to prevent a company from being dissolved. In the vast majority of large enforcement bundles, the parties find a way to secure the survival of a corporation that has been an endemic briber. The principal component of the survival strategy is the crucial agreement that criminal prosecution should be avoided. The second component is ensuring that the penalties do not destroy or harm the company so as to cause unfair collateral damage to innocent employees, shareholders and other stakeholders. This shared motivation is manifested as penalty discounts through the rationale of allegation bundling. The evidence of discounting is discussed in the following section.

Allegation bundling as a form of discounting

Allegation bundling can be also assessed as a practice with significant effects on market competition. This effect of bundling is debated in, for example, the antitrust literature, where the central question is whether bundling is an innocuous form of discounting or a means of extending market power with view to stifling competition (Elhauge Citation2009). To some extent, these analogies could also apply in the case of foreign anti-bribery enforcement, when obviously related violations are bundled together for administrative convenience (for example, US Department of Justice Citation2014b). Furthermore, when settlement bundles are offered at less than the total price of the component parts, as is usually the case, the corporate defendant should benefit with a bundled price discount.

From one perspective, the market for the enforcement of foreign anti-bribery law, however, is not a competitive market. Each enforcement authority is a monopolist within the scope of its jurisdiction (Berman Citation2007). The DOJ, for example, has full authority to prosecute FCPA violations regardless of where in the world they occur (Hock, Citation2017). An enforcer cannot extend the market power it already has. It can, however, enhance the power and efficiency of its market penetration by offering discounts to non-compliance corporations.

Bundling allegations presents one form of such discounting that has not been discussed and fully understood. Some discounts are envisaged by formal policy documents. For example, the FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy (US Department of Justice Citation2019) provides that when a company has voluntarily self-disclosed misconduct in an FCPA matter, fully cooperated, and timely and appropriately remediated, it can receive a declination, or a 50% reduction. The field research identified two key forms of discounting: (a) limiting the scope of internal investigation and (b) consequence discounts including charges, sanctions, and public information. These forms of discounting are illustrated in following sections.

Limiting the scope of internal investigation

Multiple interviewees indicated that one of the key functions of allegation bundling is to limit the scope of investigation, especially in cases of endemic corruption. This is because both the enforcer and the defendant are keenly interested in the efficiency of complex investigations. Although setting the case parameters in this way limits the number of bribery events taken into account, it is still likely to be far more than in confrontational cases where the prosecutor only needs sufficient examples to prove its case in court. Participant 10, explained how practical logistical and efficiency considerations led inevitably to bundling discussions once their internal investigation revealed an increasing number of corrupt schemes:

We can feed them some of this information and make it part of the package. And then say, but this is it, we can’t do – we operate in [many] countries around the world, we can't do a full-fledged investigation in every single one of them - this has got to stop somewhere. But you know, we have this one guy who is a common denominator, or this one company that we’ve used as facilitators, we will look at all the transactions associated with that company […]

[…] and we met with them every couple of weeks and said, here’s where we’ve gone to this country and we’ve got a box from there, we’re talking to this witness, and lots of very parallel, they knew exactly what we were doing. And at the end of 20 countries, the guys in my plan thought they knew what the facts were pretty well, and the government knew, they didn’t need all 100 countries […]

Consequence discounts – charges, sanctions and public information

The second stage of discounting emerges during the analytical phase of the investigation. The prosecutor and the corporation’s representatives negotiate the outcomes of the analysis in four key areas: the legal interpretation of the facts, the estimate the scale of the offending, the legal consequences and how the facts are interpreted for publication in settlement documents. All four elements need to be coherently aligned to deliver adequate justice and to ensure that justice is seen to be served, whilst limiting the damage to the corporation in order to avoid collateral harm. Although the size of the financial penalty is always important, it is very often a secondary concern to the potential reputational damage arising from a toxic interpretation of the facts in public documents. As the corporation is more attuned to reputational issues in its market than the prosecutor, the defendant has a constructive role in ensuring both parties avoid the Andersen scenario. This advantageous role increases the defendant’s negotiating power:

And so what we do when we negotiate, because I’ve done this negotiation on behalf of clients, I say to the Department of Justice, if you want to put that fact in the settlement, we will not sign it. [Participant 4]

My client had to acknowledge they’d been paying bribes in [X] of the [Y] countries […] and the government understood that this was a good company, the part that we were dealing with, was a good company they didn’t want to kill, so they had more than enough to, at the time, charge us with multiple … [X] or whatever those violations […] But they didn’t think it was profitable to go to the next 20 countries.

[…] it can help the company to just get a clean slate and you go and you say, okay, incrementally we’re going to add [Country X] on top and then when you’re adding little things, it doesn’t make a big difference, right, it’s just water in the bucket. [Participant 4]

Well, who looks, finds. Maybe it’s an opportunity to spend a little bit more money in time because sanction would be maybe the same. And if we find something, we just include it into the settlement and nobody will come again, like they will not come back to us, potentially. It’s an opportunity for first time sanction, let’s say [Participant 8]

To summarise this section, the findings demonstrate how the bundling of international bribery schemes in negotiated criminal settlements occurs as a form of discounting. Furthermore, there is a ceiling to financial sanctions, especially in large cases. Including additional schemes into the bundle does not proportionately increase the sanction, if at all, and the defendant benefits by avoiding the risk of further prosecutions.

Allegation bundling, however, only serves as a form of discounting if corporations have certainty that other enforcement authorities will not launch prosecutions. This may be challenging when corporate crime takes place at the level of the global economy. For example, a US settlement may activate an enforcement action in the UK. In the UK, however, the case would be subject to a judicial review and potentially could lead to a court proceeding more likely than in the US. Therefore, the sustainability of the negotiated approach to justice in international bribery and other white-collar crime cases will increasingly depend on trust, cooperation and coordination between enforcement authorities in multiple jurisdictions.

Bundling enforcers: the emergence of a market for bundles

Corporate crime does not stop at national borders. In many areas such as cybersecurity, environment, and human rights, multiple countries adopted statutes allowing them to police large firms all around the world (Zerk Citation2010). This is also the case for international bribery. Although each national authority may enjoy a monopoly within its own jurisdiction, the global enforcement of anti-bribery laws is no longer a monopoly market, thus raising the prospect of competition and even conflict between enforcers.

Increased international cooperation in tackling bribery has led to the phenomenon of bundled enforcers. For many years, the US was the only country that has actively enforced its foreign anti-bribery laws to both US and non-US corporations. Brewster (Citation2017) argues that the expansion of US enforcement was enabled by an increase in international cooperation between law enforcement officials. This increase in cooperation was facilitated by the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention and the treaty legitimised US prosecutions of foreign corporations. In effect, prosecuting non-US corporations by US enforcement authorities has become normal in areas where it would have been seen as extraordinary (Brewster and Buell Citation2017, p. 194).

Several other countries, such as the UK and France, followed the US to increase their own enforcement efforts. Participant 1 suggested that a key motivation was resentment against the US practice of collecting large sanctions from non-US corporations:

[…] they’re sick and tired of seeing all of the money go to the United States. I mean that’s the real reason behind it. They want to get the penalty monies into France. Not have it all go to the US. So there’s a race to get their share of the pie.

Corporate interest in bundling enforcers

In the new era of enforcement, the jurisdictional overlap is the key issue for corporations. Next to a favourable allegation bundle, corporations have a strong incentive to ensure the finality of their settlement. As a former prosecutor explained, the lack of enforcement coordination is costly:

It is in the company’s interest to, even if it may pay, have to pay out a substantial amount of money have so to speak one day’s worth of bad headlines. It is better to have one very bad day and reach comprehensive settlement than to have like one jurisdiction after another …

So, getting a broad release in the United States is good vis-a-vis the United States. It could provoke other countries to begin their own investigation. Now if it’s a small matter in Estonia, probably not going to be enforced by the Estonian Government. But if it’s a public matter in Brazil and Brazil is trying to clean up, then they may start to investigate you.

In the absence of these norms, the alternative is to bundle enforcers that are likely to initiate an investigation. One of the defence lawyers specifies how corporations organise this process:

[…] if you’re a company subject to multiple laws depending on the jurisdictions, in all likelihood, you want to affirmatively reach out to the respective regulators and co-ordinate some form of reporting. Sometimes that will be in sequence, sometimes that will be in unison but you can imagine that if you are, for example, a US company with an issue and some Latin American country that is now aggressively enforcing its rules as well and you learn some conduct that both authorities would want to investigate, that if you’re going to disclose to one, you’re going to disclose to both.

Interest of enforcement authorities

Many anti-corruption agencies are simply unable to investigate and prosecute some of the most powerful corporations in the world. Most countries still struggle to adopt and effectively enforce their foreign anti-bribery laws due to political, legislative or economic constraints.

One way out of this dilemma has been the bundling of enforcers. Since the late 2000s, there has been increased activity within several major enforcement actors such as Germany, Switzerland, France, the UK, and the Netherlands (see Hock Citation2020, pp. 176–181). Moreover, in some major developing countries such as Brazil, enforcement bundling enabled local enforcement authorities to investigate and sanction some of the most powerful corporations with strong links to high level politicians. Cases such as Odebrecht (US Department of Justice Citation2016) and Petrobras (US Department of Justice Citation2018) indicate that weaker national enforcement agencies can pursue politically flavoured cases if brought together with the stronger enforcement authorities of other countries.

From the perspective of enforcement authorities, the bundling of national enforcers creates the opportunity to share enforcement resources and experience. Such cooperation is a better strategy than regulatory competition (Trachtman Citation1993). Enforcement bundles enable those enforcers with limited resources or experience to pursue violations of law by joining with other enforcers with overlapping jurisdiction over the underlying misconduct (Griffith and Lee Citation2019). A bribe in jurisdiction A can be bundled with one in jurisdiction B into a global bundle AB.

Enforcement bundling should not be considered as the default response. Naturally, not every country is always open for a lecture by more experience colleagues (Snidal Citation1985). The emergence of the bundling of enforcement is shaped by many political, economic, and legal interests accompanying the policing of corporate crime (Davis Citation2018). In the future research, criminologists should grasp this complexity by examining how national law enforcement interacts with law enforcement in other countries.

Conclusion

The rapid increase of negotiated settlements reflects an evolving view that the principal role of corporate criminal enforcement is to reform corporate criminals rather than to prosecute and punish. This naturally shifts the way states interact with corporations. The concept of bundling contributes to this discussion by inviting researchers and practitioners to re-think their assumptions about how large cases of corporate crime are investigated and prosecuted. While this paper used international bribery as a case study of bundling, findings relate to the policing of global corporate crime in general.

The presence of allegation bundling indicates that the terms of corporate settlements often include violations widely separated by space and time, in which the sole common denominator is the identity of the corporate defendant. Policy-makers and enforcement authorises should acknowledge and utilise the fact that allegation bundling provides efficiencies when resolving corporate crime cases. Yet, one may call for a detailed policy and academic discussion about discounts allegation bundling offers to corporate defenders, including the fact that ‘criminogenic’ organizations are nearly always protected from being dissolved. Allegation bundling confirms the character of negotiated settlements as a symbolic criminal law tool with main function being to change large corporations through negotiation, persuasion and compliance.

Moreover, the presence of allegation bundling indicates that facts published in settlement documents and their legal qualification are not aligned with the real scope of corporate crime schemes. This is important because commentators that rely merely on publicly available data may, for example, consider the legal qualification of facts as unfair or even abusive. Yet, charging some corporations with allegations based on dubious facts and with questionable jurisdictional grounds may be demanded by a corporate defendant as part of a settlement deal. This mismatch between the real scope of a criminal scheme and what Parties disclose to the public requires closer attention.

The policing of corporate crime has been increasingly conducted in an environment in which enforcement authorities shared jurisdiction over corporate crime cases. The bundling framework shows how multiple enforcement authorities and corporations interact in the global space and how the global space impacts the construction of settlements. Given the divergence of interests, states have not designed specific legal norms that would fully deal with inefficient, and potentially unfair, forms of overlapping investigations and prosecutions. An alternative has been the emergence of enforcement bundling, a process largely facilitated by corporations.

Clearly, this global, a one-type-fits-all, bundling perspective has its limitations. It is up to the future research to investigate how and to what extent bundling is and should be impacted by national regulatory frameworks and with what consequences for the policing of corporate crime. Policy-makers should ensure that the construction of enforcement bundles is undertaken in the public interest rather than in the interests of corporations.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, BH. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Mark Button, Sean J Griffith, Mohammed Ibrahim-Shire, Elina Karpacheva, Lorenzo Pasculli, David Shepherd, and Tina Søreide for their comments on earlier drafts. I am also grateful for comments and suggestions received after presentations at the University of Portsmouth, the Symposium on Exercising Extraterritoriality in Anti-Corruption Regulation in Utrecht, and at the 2018 Transnationalization of Anti-Corruption Law conference in Paris. The viewpoints and any errors expressed herein are the author’s alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 International bribery schemes conventionally include bundling. This fact justifies why the paper focuses on bundling in this area. Bundling is enabled by the enforcement of foreign anti-bribery laws, such as the UK Bribery Act 2010 (Bribery Act) and the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), prohibiting the payment of bribes to foreign public officials. In the UK consider Airbus and Rolls Royce. In the US Alstom, BAE, Odebrecht, Siemens, Total, Telia, Walmart, and many other. A comprehensive analysis of bundling as it emerges in other fields of corporate crime lies outside the scope of this paper.

2 As the vast majority of enforcement actions have been conducted by the US enforcement authorities, the paper is more weighted towards an analysis of the US experience. The paper, nevertheless, also discusses the UK enforcement and the enforcement of other countries when appropriate.

3 While terms ‘offence bundling’ or ‘violation bundling’ might present in some instances a more precise framing, the paper operates with the term ‘allegation bundling’ in order to reflect the fact that settlements include claims that might be unsubstantiated.

4 The US law is discussed because allegation bundling has been pioneered by the US enforcement authorities. These techniques are relevant globally.

5 The analysis based on the text of 15 U.S.C. §§ 78m(b)(2)(A), 78m(b)(2)(B), 78m(b)(5), and 78ff(a).

References

- Arlen, J., 2016. Prosecuting beyond the rule of law: corporate mandates imposed through deferred prosecution agreements. Journal of legal analysis, 8 (1), 191–234. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/law007

- Arnold, R.D., 1990. The logic of congressional action. London: Yale University Press.

- Bebchuk, L.A., and Kamar, E., 2010. Bundling and entrenchment. Harvard Law review, 123 (7), 1549–1595.

- Berman, P., 2007. Global legal pluralism. Southern California Law review, 80 (6), 1155–1238.

- Boeije, H., 2010. Analysis in qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

- Braithwaite, J., 1985. To punish or persuade: enforcement of coal mine safety. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Braithwaite, J., 2002. Restorative Justice and Responsive Regulation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Braithwaite, J., and Fisse, B., 1985. Varieties of responsibility and organisational crime. Law & policy, 7 (3), 315–343. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.1985.tb00356.x

- Brewster, R., 2017. Enforcing the FCPA: international resonance and domestic strategy. Virginia Law review, 103 (8), 1611–1681.

- Brewster, R., and Buell, S.W., 2017. The market for global anticorruption enforcement. Law and Contemporary problems, 80, 193–214.

- Button, M., 2019. Private policing.. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Button, M., Shepherd, D., and Blackbourn, D., 2018. “The higher you fly, the further you fall”: white-collar criminals, “special Sensitivity” and the impact of conviction in the United Kingdom. Victims & offenders, 13, 628–650. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2017.1405133

- Davis, K.E., 2018. Multijurisdictional enforcement games: the case of anti-bribery Law. In: J. Arlen, ed. Research Handbook on corporate crime and financial misdealing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 151–174.

- DOJ and SEC. 2012. A resource guide to the US foreign corrupt practices act. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/criminalfraud/legacy/2015/01/16/guide.pdf [Accessed 7 May 2020].

- Elhauge, E., 2009. Tying, bundled discounts, and the death of the single monopoly Profit theory. Harvard Law review, 123 (2), 397–481.

- Fisse, B. and Braithwaite, J., 1993. Corporations, crime, and accountability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ford, C., and Hess, D., 2008. Can corporate monitorship improve corporate compliance? Journal of corporation Law, 34 (3), 679–738.

- Galtung, F., 1998. Criteria for sustainable corruption control. European Journal of Development research, 10 (1), 105–128. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09578819808426704

- Garret, B.L., 2016. Too big to jail: how prosecutors compromise with corporations. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Golden, N., 2019. Conspicuous prosecutions in the shadows: rethinking the relationship between the FCPA’s accounting and anti-bribery provisions. Iowa Law review, 104 (2), 891–925.

- Grasso, C., 2016. Peaks and troughs of the English deferred prosecution agreement: the lesson learned from the DPA between the SFO and ICBC SB Plc. The Journal of business Law, 2016 (5), 388–408.

- Griffith, S.J., and Lee, T.H., 2019. Toward an interest group theory of foreign anti-corruption law. University of Illinois Law review, 2019 (4), 1227–1266.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M., and Namey, E.E., 2012. Applied thematic analysis. London: Sage Publications.

- Guzman, A.T., 2011. Cooperation, comity, and competition policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hawley, S., King, C., and Lord, N., 2020. Justice for whom? The need for a principled approach to deferred prosecution in England and Wales. In: T. Søreide, A. Makinwa, eds. Negotiated settlements in bribery cases: a principled approach. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 309–346.

- Hess, D., and Ford, C., 2007. Corporate corruption and reform undertakings: a new approach to an old problem. Cornell international Law Journal, 41 (2), 307–346.

- Hock, B., 2017. Transnational bribery: when is extraterritoriality appropriate. Charleston Law review, 11 (2), 305–352.

- Hock, B., 2020. Extraterritoriality and international bribery: a collective action perspective. Abingdon: Routledge.

- House of Lords. 2019. The Bribery Act 2010: post-legislative scrutiny. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/ldbribact/303/303.pdf [Accessed 15 August 2020]. .

- Huisman, W., 2016. Criminogenic organizational properties and dynamics. In: S. R. Van Slyke, M. L. Benson, F. T. Cullen, eds. The Oxford handbook of white-collar crime. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 435–462.

- Iossa, E., and Martimort, D., 2012. Risk allocation and the costs and benefits of public-private partnerships. The RAND Journal of Economics, 43 (3), 442–474. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2171.2012.00181.x

- Kalof, L., Dan, A., and Dietz, T., 2008. Essentials of social research. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- King, C. and Lord, N., 2018. Negotiated Justice and corporate crime: the legitimacy of civil recovery orders and deferred prosecution agreements. Cham: Palgrave Pivot.

- King, C. and Lord, N., 2020. Deferred prosecution agreements in England and Wales: castles made of sand? Public Law, April 2020, 307–330.

- Levi, M., 2008. Organized fraud and organizing frauds: unpacking research on networks and organization. Criminology and criminal Justice, 8 (4), 389–419. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895808096470

- Lord, N., 2014a. Responding to transnational corporate bribery using international frameworks for enforcement: anti-bribery and corruption in the UK and Germany. Criminology and criminal Justice, 14 (1), 100–120. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895812474662

- Lord, N., 2014b. Regulating corporate bribery in international business: anti-corruption in the UK and Germany. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- Lord, N., Levi, M., et al., 2015. Determining the adequate enforcement of white-collar and corporate crimes in Europe. In: Van Erp, ed. The Routledge handbook of white-collar and corporate crime in Europe. Abingdon: Routledge, 39–56.

- OECD. 2011. Convention on combating bribery of foreign public officials in international business transactions and related documents. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/ConvCombatBribery_ENG.pdf [Accessed 16 April 2020].

- Pollack, B., 2009. Time to stop living vicariously: a better approach to corporate criminal liability. American criminal Law review, 46 (4), 1393–1416.

- Posner, R., 2007. Economic analysis of law. 7th ed. New York: Aspen Publishers.

- Reilly, P., 2014. Negotiating bribery: towards increased transparency, consistency, and fairness in pretrial bargaining under the foreign corrupt practices act. Hastings business Law review, 10 (2), 347–406.

- Reiss, A., 1984. Consequences of compliance and deterrence models of law enforcement for the exercise of police discretion. Law and Contemporary problems, 47 (4), 83–122. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1191688

- Ross, J., 2002. What makes sentencing facts controversial – four problems obscured by one solution. Villanova Law review, 47 (4), 965–988.

- Rubin, E., 2016. Executive action: its history, its dilemmas and its potential remedies. Journal of legal analysis, 8 (1), 1–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/law008

- Ryder, N., 2018. ‘Too scared to prosecute and too scared to jail?’ a critical and comparative analysis of enforcement of financial crime Legislation against corporations in the USA and the UK. Journal of criminal Law, 82 (3), 245–263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018318773209

- Ryder, N. and Pasculli, L., 2020. Corruption, Integrity and the Law: Global Regulatory Challenges. London: Routledge.

- SEC. 2019. Walmart charged with FCPA violations. Available from: https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2019-102 [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- Serious Fraud Office. 2017. Deferred prosecution agreement. SFO v. Rolls-Royce PLC. Available from: https://www.sfo.gov.uk/download/deferred-prosecution-agreement-sfo-v-rolls-royceplc/?wpdmdl=14777&refresh=5e96d112375d31586942226 [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- Serious Fraud Office. 2020. Deferred prosecution agreement. SFO v. Airbus. Available from: https://www.sfo.gov.uk/download/airbus-se-deferred-prosecution-agreement-statement-of-facts/# [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- Snidal, D., 1985. The limits of hegemonic stability theory. International Organization, 39 (4), 579–614. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830002703X

- Søreide, T., and Makinwa, A., eds. 2020. Negotiated settlements in bribery cases: a principled approach. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Stevenson, D., and Wagoner, N., 2011. FCPA sanctions: too big to debar? Fordham Law review, 80 (2), 775–820.

- Stuntz, W., 2004. Plea bargaining and criminal law’s disappearing shadow. Harvard Law review, 117 (8), 2548–2569. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/4093405

- Sutherland, E.H., 1949. White collar crime. New York: Dryden Press.

- Tombs, S., and Whyte, D., 2011. Corporate or criminal? The dangers of reducing corporate prosecutions. New Law Journal, 161 (7449), 81–84.

- Tombs, S., and Whyte, D., 2019. The shifting imaginaries of corporate crime. Journal of white collar and corporate crime, 1 (1), 16–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2631309X19882641

- Trachtman, J., 1993. International regulatory competition, externalization, and jurisdiction. Harvard international Law Journal, 34 (1), 47–104.

- US Department of Justice. 2013. Deferred prosecution agreement. United States vs. Total S.A., No. 13-cr-239. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/9392013529103746998524.pdf [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- US Department of Justice. 2014a. Plea agreement. United States vs. Alstom SA et al., No. 14-246. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/file/189331/download [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- US Department of Justice. 2014b. Hewlett-Packard Russia pleads guilty to and sentenced for bribery of Russian Government officials. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/hewlett-packard-russia-pleads-guilty-and-sentenced-bribery-russian-government-officials [Accessed 15 April 2020].

- US Department of Justice. 2016. Odebrecht and Braskem plead guilty and agree to pay at least $3.5 billion in global penalties to resolve largest foreign bribery case in history. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/odebrecht-and-braskem-plead-guilty-and-agree-pay-least-35-billion-global-penalties-resolve [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- US Department of Justice. 2017. Rolls-Royce plc agrees to pay $170 million criminal penalty to resolve foreign corrupt practices act case. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/rolls-royce-plc-agrees-pay-170-million-criminal-penalty-resolve-foreign-corrupt-practices-act [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- US Department of Justice. 2018. Petroleo Brasileiro S.A. – Petrobras agrees to pay more than $850 million for FCPA violations. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/petrleo-brasileiro-sa-petrobras-agrees-pay-more-850-million-fcpa-violations [Accessed 30 June 2020].

- US Department of Justice. 2019. FCPA corporate enforcement policy (USAM 9-47.120).

- US Department of Justice. 2020. Airbus agrees to pay over $3.9 billion in global penalties to resolve foreign bribery and ITAR Case. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/airbus-agrees-pay-over-39-billion-global-penalties-resolve-foreign-bribery-and-itar-case [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- Van Erp, J. and Huisman, W., 2017. Corporate crime. In: N. South, E. Carrabine, A. Brisman, eds. The Routledge companion to criminological theory and concepts. 1st ed.Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 248–252.

- Willborn, E., 2013. Extraterritorial enforcement and prosecutorial discretion in the FCPA: a call for international prosecutorial Factors. Minnesota Journal of international Law, 22 (2), 422–452.

- Zerk, J.A. 2010. Extraterritorial jurisdiction: lessons for the business and human rights sphere from six regulatory areas. Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government.