ABSTRACT

This conceptual article contributes to the scientific debate on police culture and police legitimacy by exploring and refining the concept of self-legitimacy. It argues that endogenously constructed self-legitimacy co-produces and reinforces certain core characteristics of police culture. ‘Self-legitimacy’ in this context is the degree to which those in power believe in the moral justice of their power. Endogenous self-legitimation processes occur when officers identify with the professional police identity and the police organisation, and self-legitimacy is brought about by those in power attributing unique characteristics to themselves and seeking validation from an inner circle of similar power-holders. Drawing on the analysis, suggestions are made on how police culture and police legitimacy can be influenced by facilitating a shift in officers’ perception of their ‘professional identity’.

Introduction

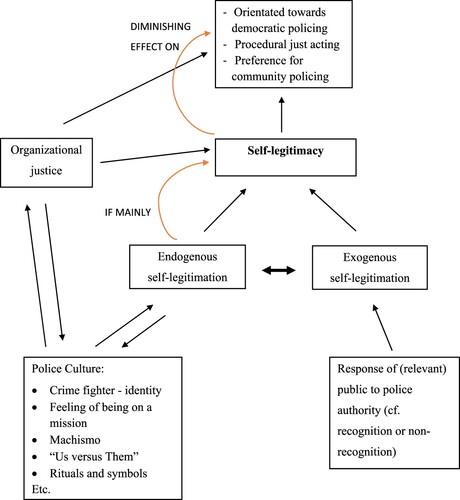

Self-legitimacy concerns the confidence power-holders have in the moral validity of their power (Bottoms and Tankebe Citation2012). The consequences of an unbalanced (an excess or lack of) or balanced self-legitimacy in police officers have been reasonably well mapped out. Officers with a balanced belief in the moral justice of their authority appear to be more democratically oriented and more likely to act in a procedurally just manner (Bradford and Quinton Citation2014, Tankebe Citation2018). They show a preference for non-aggressive policing and community policing, are less influenced by negative public rhetoric about policing and are more protected from negative experiences within the police force (e.g. bad management practices) (Bradford and Quinton Citation2014, Tankebe and Meško Citation2015, Noppe Citation2016, Nix and Wolfe Citation2017, Wolfe and Nix Citation2017, Tankebe Citation2018, Trinkner et al. Citation2019). However, there is more ambiguity about the sources of self-legitimacy. Bottoms and Tankebe (Citation2012, Citation2013) suggest several potential routes through which ‘junior power-holders’ develop their self-legitimacy, such as: the legal framework of their function, interactions with colleagues and superiors, the need to construct a positive social identity, shared values with the public, etc. However, little research has been done into the sources police officers draw on to justify the privilege of their power to themselves, and how that can shape their roles (Tankebe Citation2010, Bottoms and Tankebe Citation2012, Gau and Paoline Citation2019). This conceptual article argues that the impact of endogenous self-legitimation on police officers’ self-legitimacy has been underestimated, and that these forces co-produce and strengthen some core characteristics of police culture and are of relevance with regard to police legitimacy. It would be of substantial added value if further empirical research on police self-legitimacy sufficiently took into account the possible impact of endogenous processes on self-legitimacy, and how these endogenous processes relate to police culture and police legitimacy. Such scientific advances could contribute to identifying effective levers for achieving desired changes in policing. This article is an invitation to this end and a possible (basis for a) heuristic to be used.

The argument is structured as follows. First, the concepts of legitimacy and self-legitimacy are discussed in relation to their meaning for the police. Second, self-legitimacy is explored through the impact of two opposing forces – exogenous and endogenousFootnote1Footnote2 – and it is argued that the importance of endogenous self-legitimation among police officers has been underestimated. Third, the core characteristics of ‘police culture’ are linked with endogenous self-legitimation, and the concept and role of ‘police culture’ is critically examined. The final section considers the implications of these findings for police practice and for the future research agenda on self-legitimacy and police culture, and provides insights on how police culture and police legitimacy can be influenced.

Legitimacy and self-legitimacy

In the social sciences, the modern conceptualisation of legitimacy is generally based on Max Weber (Beetham Citation1991, Tyler Citation2004, Bottoms and Tankebe Citation2012). Weber’s (Citation1978) conceptualisation centres on citizens’ beliefs about a particular regime. Legitimacy is acquired when citizens believe that the government has the right to dictate ‘appropriate behaviour’ to them. This approach is often described as empirical legitimacy or audience legitimacy: the legitimacy of a regime or government is ascribed by third parties/citizens. Weber (Citation1978) conceptualises legitimacy in terms of sources that lead to stability and authority, and legitimacy is attached to the voluntary subjection of citizens to the power of the state. He distinguishes three modes through which this can be accomplished: by legal authority – based on a system of rules; by traditional authority – based on the idea that it ‘has always existed’; or by charismatic authority – based on a leader’s charisma.

Beetham (Citation2013) considers empirical or audience legitimacy to have too narrow a focus, because Weber, while emphasising citizens’ belief in a certain regime, overlooked the factors that give people sufficient grounds for this belief. Beetham (Citation2013) suggests that state power is legitimate if: ‘it conforms to established rules, the rules can be justified by reference to beliefs shared by both dominant and subordinate, and there is evidence of consent by the subordinate to the particular power relation’ (p. 16). In addition to the legal framework in which power should be embedded, there is – according to Beetham – a need for a shared framework of values between rulers and citizens. Both groups must believe that power-holder and subordinate are linked by a community of interest and that the distribution of power serves not only the powerful but also the subordinates. Beetham argues that citizens should actively demonstrate their belief in the legitimacy of power through actions of ‘consent’ that transcend mere obedience; a lack of open protest about the requirements of the powerful is insufficient evidence for claiming that people consent to them (especially because obedience can be maintained by coercion). Whereas Weber would ask citizens directly whether they consider the government legitimate, Beetham would ask what citizens consider to be necessary to be able to speak of a legitimate power relationship (Noyon Citation2017). Other academics, especially moral and political philosophers (such as Allen Buchanan, Ross Mittiga, Philipp Pettit, John Rawls and Roland Dworkin) reject an empirical approach and argue for a normative basis to graft legitimacy onto. They suggest, for example, that a political regime is legitimate when it respects basic human rights or moral standards, follows certain procedural principles, functions democratically, is able to ensure safety and security, and promotes freedom. This is described as normative legitimacy.

The work of Tom Tyler (Citation1990, Citation2006, Citation2009, Citation2011) builds on empirical legitimacy from a social psychological perspective. He shows that people are more likely to obey the law if they perceive legal authorities to be legitimate, and demonstrates that the perception of legitimacy is connected to the manner in which people are treated during an interaction with a power-holder (such as the police). Since the publication of Tom Tyler’s Why People Obey the Law (Citation1990), the antecedents of empirical legitimacy at the micro level have been the subject of much research (Tankebe Citation2013). It has consistently been found that citizens grant legitimacy to the person in power – in this case a police officer – when the citizen perceives that the person in power treats them in a neutral way (the power-holder’s actions and decision making are based on facts and not on the citizen’s personal characteristics or on situational factors), allows them a ‘voice’ (they are able to express their viewpoint before the power-holder makes a decision), shows them dignity and respect (in the way they are treated), and acts in an honest way (showing care and concern for the citizen’s well-being, being aware of their needs). This ‘procedurally just behaviour’ turns out to be a basic condition for the public to judge the authority of those in power as legitimate. If a police officer is perceived not to have acted in this way, people might conclude that they have been treated unfairly and question the legitimacy of the police as an institution. In addition to identifying the procedures are effective in ensuring citizens attribute legitimacy to the police, Tyler (Citation1990, Citation2006, Citation2011) also highlights the importance of a demonstrable ability to fight crime and the fairness of the rules themselves. Fairness of the rules relates to whether or not the public agree with the law: the public consider police power to be legitimate when they believe that the police are operating in accordance with the moral framework of society (Hough et al. Citation2010, Jackson et al. Citation2012). This element ties in with Beetham’s view on legitimacy: that there is a need for a shared base of values between those in power and the public. If the police enforce laws that the public do not (or no longer) consider appropriate, this would cause legitimacy problems.

Legitimacy is now an established topic in criminology, but by contrast little is known about the dimension of power-holder legitimacy or self-legitimacy (Tyler Citation1990, Bottoms and Tankebe Citation2012, Tankebe Citation2014). Weber (Citation1978) argues that power-holders will believe in their legitimacy if their power is formally and legally correct, thus placing ‘legality’ at the centre of the development of self-legitimacy. Beetham (Citation1991) argues that there is an important distinction between the legitimacy of the individual power-holder and the legitimacy of the power system itself. The legitimacy of the individual ruler derives from the moral justice of the law, and therefore the individual ruler would not have to justify himself. It is only the rules themselves that must be morally just. Yet Weber and Beetham also pay some attention to the power-holder dimension of legitimacy. Weber argues that those in power must also convince themselves that they deserve their power, and Beetham indicates that we can deepen the concept of legitimacy by examining self-legitimacy. In this respect, Beetham refers to the perspective of Rodney Barker (Citation2001), who argues that those in power will first and foremost convince themselves of their legitimacy in power and that they achieve this in particular by attributing to themselves an identity that distinguishes them from the ‘ordinary citizen’.

Exogenous versus endogenous self-legitimation

Bottoms and Tankebe (Citation2012, Citation2013) emphasise the dialogical nature of self-legitimacy and identify citizens as the most crucial audience. They embed self-legitimacy within a legitimacy dialogue that takes place between the ruler (as an individual or as an institution) and the public (as a citizen or as a society). The dialogue starts with a claim to legitimacy from the person in power who then waits for a reaction from the public. If the relevant public reject the first call by a ruler to respect their power, this is a stress test for the ruler. When this happens, rulers would reflect on the ‘rightness’ or ‘pertinence’ of their power claim and make a new, possibly modified, call to obey their authority. In Bottoms and Tankebe’s view of self-legitimacy, empirical legitimacy is mirrored in the perspective of the police: just as citizens attribute legitimacy to police officers and to the police as an institution, police officers would shape their self-legitimacy using their own perceptions and experience of whether the public consider them legitimate or not. The hypothesis that citizens’ recognition or non-recognition of police officers’ power has a strong influence on officers’ self-legitimacy is also supported by other authors, such as Wilson (Citation1968), who states that police officers expect recognition and cooperation from citizens, and that if they do not receive this, officers’ trust in their position of power will waver. From this perspective, police officers could never be immune to the public’s attitudes and perceptions of them (Tankebe Citation2010). Legitimation that has been shaped by what the public (i.e. non-power holders) think about the power-holders in question could be referred to as ‘exogenous self-legitimation’.

Barker (Citation2001) has a different view of self-legitimacy, arguing that the self-assessment of those in power is the determining factor. ‘The principal way in which people issuing commands are legitimated is by their being identified as special, marked by particular qualities, set apart from other people’ (Barker Citation2001, pp. 34-35). This means that those in power do not need the affirmation of the public to believe in the legitimacy of their own power – they have little or no interest in whether the ‘average citizen’ endorses their carefully developed self-image (Barker Citation2001). Their belief in the legitimacy of their power stems, instead, from an internalised acceptance that they deserve their position by virtue of possessing certain specific character traits (cf. ‘being unique’), and from the confirmation of this by other rulers (Barker Citation2001). ‘If one asks, “where, by whom, and for whom?” is the activity of legitimation carried on, the answer in almost every case will be “amongst rulers, by rulers, and for rulers”’ (Barker Citation2001, p. 107). Other authors, such as Coicaud (Citation2002), Di Palma (Citation1991), and Wrong (Citation1995), also endorse the importance of this perspective. This vision can be called ‘endogenous self-legitimation’: self-legitimation on the basis of self-identification with the position of power and by seeking confirmation of uniqueness from similar rulers.

Barker’s interpretation (Citation2001, Citation2003) emphasises the importance of legitimation practices: symbolic activities that cultivate and confirm rulers’ unique identity and authority. He argues that these practices occur first and foremost among rulers themselves; second, between rulers and their immediate staff; third, between rulers and members of ruling groups in other countries, and between rulers and powerful citizens; and fourth, between rulers and ordinary citizens. Barker speaks of rituals and rites unknown to the majority of citizens that take place out of the public eye, and he stresses the significance of the physical environment and the presence of certain objects, materials and attributes.

Bottoms and Tankebe (Citation2012) argue that Barker’s perspective does not apply, or hardly applies, to police officers. Barker’s analysis starts from ruling elites such as high-ranking politicians and kings, and Bottoms and Tankebe argue that for ‘junior rulers’ just the opposite is the case. For ‘junior power-holders’, citizens would be their crucial touchstone for achieving self-legitimacy, precisely because they regularly come into contact with each other, and the power-holders have to demonstrably live up to the authority they have. There are, however, several elements pointing towards the accuracy of Barker’s analysis with regard to the self-legitimacy of police officers.

First, empirical studies of the self-legitimacy of police officers use different criteria and measurement scales (Gau and Paoline Citation2019). The lack of an unambiguous operationalisation makes it difficult to conclude whether either the exogenous or the endogenous hypothesis has more specific weight (Gau and Paoline Citation2019). Some research designs, such as that of Jonathan-Zamir and Harpaz (Citation2014), only use criteria that can endorse or refute exogenous self-legitimation, and in other studies there is no empirical distinction made between exogenous and endogenous sources of self-legitimacy (Gau and Paoline Citation2019).

Second, several ethnographic studies of the police endorse the hypothesis that self-legitimation is a (partially) endogenous activity without explicitly naming it as such. Muir (Citation1977) indicates that police officers construct a self-definition that is independent of the ambiguity of public conflict and that leans towards the idea of themselves as neutral law enforcers, and he emphasises the importance of close and trusting relationships with colleagues in order to experience police work and the police function as enjoyable. Skolnick (Citation1966), Manning (Citation1977), and Herbert (Citation1996, Citation2006) find that police officers legitimize their actions to themselves by referring to ‘a higher good’ and that they see themselves as specialised virtuous protectors of society.

Third, Barker argues that, in addition to identification with a professional identity, identification with the organisation is an important source of self-legitimacy. Multiple studies – such as Bradford et al. (Citation2014), and Bradford and Quinton (Citation2014) – confirm that identification with the values present in the organisation is a substantial resource of self-legitimacy.

Fourth, Barker’s hypothesis that belief in the moral justice of power and professional identity are intrinsically linked is supported by substantial literature on self-esteem and professional identity. Professional identity is a crucial social identity (Schein Citation1978, Ibarra Citation1999) – that part of the self-concept that results from belonging to a particular social group (Tajfel Citation1982, p. 2). Membership of a particular social group contributes to one’s ability to judge people and situations, gives a sense of belonging and strongly influences self-esteem (the degree to which one experiences coherence between the ideal self-image and the actual self-image) (Cohen Citation1959, Hall Citation1987, Fine Citation1996). A professional identity is important in developing and maintaining a positive self-image, and organisations play a role in this by regulating self-image (Festinger Citation1954, Brockner Citation1988, Pierce et al. Citation1989, Pierce and Gardner Citation2004, Hotho Citation2008). When someone enrols in police training, this means more than gaining access to a particular job – it defines the identity of the individual (Kleinig Citation1996). The identification ‘I am the police’ and the attribution of positive characteristics to that professional identity are decisive elements through which police officers obtain self-legitimacy.

Fifth, several empirical studies of self-legitimacy point in the direction of endogenous self-legitimation. Bradford and Quinton (Citation2014) find that the most crucial source of self-legitimacy is identification with one’s organisation. Tankebe (Citation2018), Tankebe and Meško (Citation2015), and White et al. (Citation2020) find that self-legitimacy is primarily based on moral alignment with and endorsement by colleagues. In contrast, police officers’ assessment of the extent to which the public consider them legitimate appears to have little or no effect on their self-legitimacy (Tankebe and Meško Citation2015, Tankebe Citation2018). These studies confirm the importance of endogenous self-legitimation: identification with similar rulers and with the organisation/profession is paramount, and the opinions of the public are a negligible factor. It also appears that police officers’ assessment of the extent to which the police as an institution reduces crime has no effect on their self-legitimacy (Gau and Paoline Citation2019). This is in line with Barker’s view that those in power feel they deserve their power, regardless of the effectiveness of their performance.

Endogenous self-legitimation and core characteristics of police culture

Ethnographic research into police work in the 1950s and 1960s provided insight into what would later become known as ‘police culture’. Police culture is an occupational culture, just as in other professions (such as social workers, etc.). Manning (Citation1995) gives the following definition: ‘‘occupational cultures contain accepted practices, rules, and principles of conduct that are situationally applied, and generalized rationales and beliefs’’ (p. 472). One perspective on police culture and other professional cultures is that it is a guiding force for behaviour; undesirable behaviour by individual police officers can therefore be understood to be a consequence of negative elements present in the professional culture.

Reiner (Citation1985, Citation2010) identified the following core characteristics of the police culture: moral conservatism, a tendency towards machismo, a self-image of crime-fighters combined with an active pursuit of ‘kicks’, the feeling of being on a mission to fight evil, a suspicious and sometimes cynical view of the world and towards citizens, a strong separation between self and citizens, a strong separation between respectable citizens and deviant citizens/groups, and strong solidarity with one’s own colleagues. Several studies found similar cultural characteristics, leading to a relative consensus on these core features, for example Fielding (Citation1994) and Herbert (Citation2001) regarding macho culture, Loader and Mulcahy (Citation2003) regarding moral conservatism, and Paoline (Citation2003) regarding the strong distinction police officers make between themselves and outsiders.

Recent research on police culture has also revealed more ‘positive’ features than those mentioned above. Police officers are said to value community policing highly (Cochran and Bromley Citation2003), there is a growing focus on protecting vulnerable populations and acting as mediators (Charman Citation2017) and police culture is said to have become more receptive to institutional reform in parallel with the growing presence of female and non-heterosexual oriented police officers (Sklansky Citation2006). Furthermore, several authors nuance the impact and/or existence of ‘the police culture’. Cain (Citation1973), Crank (Citation2014) and Brough et al. (Citation2016) argue that the police organisation determines or co-determines the presence of cultural characteristics in a given police institution. Such organisation-driven cultural differences are said to stem, among other things, from different styles of leadership present in different police forces (Brough et al. Citation2016). Shearing and Ericson (Citation1991), and Manning (Citation2007, Citation2008, Citation2010) still perceive police behaviour as being driven by police culture, but argue a less deterministic form. They refer to the way in which an actor is led by a director: the actor himself still has to improvise, take the initiative and make things up as the play progresses. Police culture is no longer regarded as a unitary system, but rather as a ‘toolbox’ of possible resources. Chan (Citation1997), like the authors cited above, criticises the idea of a deterministic and linear professional culture that reduces police officers to ‘docile sheep’, but goes a step further. In addition to the importance of individual agency and personality, she emphasises the impact of the social and political reality on the culture of police organisations. She suggests that the failure of many attempts by police leaders and policy makers to change police culture or a particular organisational culture is due to the influence of this field being ignored.

Nevertheless, several researchers, such as Loftus (Citation2009, Citation2010) and Reiner (Citation2010), state that, despite multiple social changes and organisational reforms, the core characteristics of police culture and the view that they form a (limited or powerful) guiding force for police behaviour still hold today.

The emergence of an occupational culture is generally considered to be due to the specific tasks and problems inherently associated with a particular profession (Paoline Citation2003). An occupational culture is said to function as a coping mechanism for the tensions arising from its specific tasks and problems (Paoline Citation2003). As Manning (Citation1994) notes: ‘as an adaptive modality, the occupational culture mediates external pressures and demands, and internal expectations for performance and production’ (p. 5). Specific to the police profession is the potential danger on the street that officers constantly encounter (Skolnick Citation1966, Van Maanen Citation1974, Reiner Citation1985, Brown Citation1988), the unique authority that comes with their right to use force (Bittner Citation1974, Van Maanen Citation1974, Reiner Citation1985, Brown Citation1988, Manning Citation1995) and ambiguity inherent in the police function (Skolnick Citation1966, Rumbaut and Bittner Citation1979). The potential danger to which the police are constantly subjected may explain why officers form a close-knit and supportive community that sees itself as separate from the public (Skolnick Citation1966, Sparrow et al. Citation1990, Kappeler et al. Citation1998), and why officers tend to have a suspicious view of the world (Rubinstein Citation1973, Van Maanen Citation1974, Muir Citation1977). Their unique authority may explain the presence of machismo elements in their culture; police officers must demonstrate and enforce their authority on a daily basis (Manning Citation1995). The ambiguity inherent in the police function is the simultaneous demand on the professional role of police officers to maintain social order, enforce the law and provide service (Wilson Citation1968, Rumbaut and Bittner Citation1979, Brown Citation1988). To deal with this discrepancy, the image of ‘crime-fighters’ is perpetuated (Fielding Citation1988, Jermier et al. Citation1991). Another factor is that police training, the historical tradition of the police, the presence of special combat units, the focus on crime statistics, etc., all refer mainly to the professional role of law enforcement officer (Bittner Citation1974, Walker Citation1999).

We do not question the above analysis and findings, but argue that the relation between endogenous self-legitimation and police culture has, to date, been absent from analysis, while in fact several factors indicate a relevant connection between endogenous self-legitimation processes and the phenomenon of police culture. For example, police officers often justify their power by telling anecdotes about confrontations with ‘villains’ (Graef Citation1990, Skolnick and Fyfe Citation1993, Fletcher Citation1996, Herbert Citation1998, Waddington Citation1999). Those in power can more easily justify themselves if something undesirable exists alongside them – an ‘enemy’ to fight, a mission to tackle what is undesirable in society. As Barker (Citation2001) notes, ‘one way in which people may legitimate their own identities is by cultivating an enemy identity with which to contrast their own’ (p. 129). Police officers justify their power by placing crime-fighting at the centre of their professional identity (Fielding Citation1988, Herbert Citation2001, Reiner Citation2010). Making the image of crime-fighters less central to their self-definition – regarding and acting out the police role more as mediators who contribute to social peace, ‘community policing’, etc. – could lead to reduced self-legitimacy. Akoensi (Citation2016) examined self-legitimacy among prison officers in Ghana and found that, in addition to the legal framework in which they operate, the officers’ uniforms reinforce their self-legitimacy. This ties in with Barker’s thesis that objects and attributes play an important role in achieving self-legitimacy. The police uniform and associated attributes – such as a revolver and handcuffs – emphasise the law enforcement dimension, superiority and crime-fighter elements of professional identity (Bell Citation1982, Singer and Singer Citation1985). Furthermore, research indicates that police officers perceive their own morality and behaviour as superior to that of most people, and from this they develop a sense of ‘entitlement to power’, or self-legitimacy (Gau and Paoline Citation2019). At the same time, police officers assume that the public have an ambivalent attitude to the police, but the impact of this on their self-legitimacy appears to be negligible (Tankebe Citation2018, Gau and Paoline Citation2019). The higher assessment of their own morality (as a function of self-legitimacy) may help to explain why police officers tend to make a clear distinction between themselves and members of the public, as well as why they feel a strong connection with their own colleagues – people who, like them, have a higher morality than that of the ‘average citizen’. It has even been found that cynicism toward citizens – described as ‘resentment toward the people they deal with daily’ (p. 286) – contributes to increased self-legitimacy (Gau and Paoline Citation2019). This also supports Barker’s hypothesis that those in power lean more on their personal merit to justify their moral legitimacy in power than on the extent to which the public do or do not recognise them as legitimate rulers (Gau and Paoline Citation2019) ().

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of police legitimacy and police culture through the lens of self-legitimacy. Highlighting that self-legitimacy that is primarily endogenously constructed can diminish the desirable (cf. police legitimacy-enhancing) and known consequences associated with self-legitimacy.

Discussion and conclusion

The process of self-legitimation appears to be closely linked to identification with the professional identity and based on a self-definition of (moral) uniqueness and its affirmation by other (‘junior’) power-holders within the relevant organisation. Such endogenous self-legitimation may partly explain why certain (dysfunctional) characteristics of police culture present themselves and continue to exist. Self-legitimacy among police officers that is largely endogenously constructed based on, among other things, ideas about exceptional personal qualities, and barely if at all connected to citizens’ confirmation of the officers’ ‘moral right to power’, is a disquieting element. However, it is conceivable that the legal nature of the police function, the identification with the uniqueness of ‘being a police officer’ and the validation of this by colleagues, carry significant weight to achieve self-legitimacy. It might contribute to some police officers feeling comfortable about violating norms such as the proportionate use of force or reporting colleagues’ wrongdoing, as they perceive that they belong to ‘a unique group’ that is on mission for the ‘greater good’ (Skolnick Citation1966, Shearing Citation1981, Skolnick and Fyfe Citation1993, Kappeler et al. Citation1998, Price Citation2006). From this perspective, it is all the more important that the organisational culture expresses values that society considers desirable, and that the police organisation works in an ‘organizationally just’ manner. Officers who are treated fairly by their organisation – with fair chances for promotion, good communication about the reasons for certain policy decisions, colleagues and superiors treating them with respect, etc. – are more inclined to be loyal to the police, more likely to act in a ‘procedurally just’ way in their dealings with citizens, more likely to see wrongdoing for the ‘noble cause’ as unjustified, less likely to have an omertà (code of silence) regarding police wrongdoing, and more positive about community policing and the public in general (Wolfe and Piquero Citation2011, Colquitt et al. Citation2013, Bradford et al. Citation2014, Bradford and Quinton Citation2014, Tankebe Citation2014, Van Craen and Skogan Citation2017, Maesschalck Citation2019).

Bottoms and Tankebe (Citation2012) refer in their dialogical vision to ‘a relevant public’ that questions or confirms the self-legitimacy of those in power. However, the essential question of who the relevant public are for frontline police officers remains unanswered: which group or groups within the population are likely to be able to have an effective impact on police officers’ self-legitimacy? In other words, who exactly – which audience – is (most) influential in shaping perceived audience legitimacy? Is it the officers’ colleagues and direct superiors, local government officials, ‘average and good citizens’, or the groups and individuals who officers most frequently come into contact with on the street? The research of Nix et al. (Citation2020) suggests that perceived audience legitimacy decreases if officers have a higher estimate of the degree of public hostility towards them (recent contacts with ‘disrespectful’ citizens would increase, but not absolutely determine, that hostility estimation), have a higher estimate of the degree of local media is particularly hostile towards them, or if they believe that crime has increased in their police zone. However, to what extent this perceived audience legitimacy is a determinant – and thus more or less influential than endogenous processes – for police officers’ construction of self-legitimacy remains unanswered in the aforementioned research.

Some people and strands in society may be in favour of the police taking actions with less regard to civil rights or with ‘non-procedural justice’, such as systematic and proactive stop-and-searches. Such actions may have a legitimising effect on police officers if they are supported and endorsed by an audience that is ‘relevant’ to them, and this audience may not include those who are most subjected to such practices and who, in turn, may perceive the police as less legitimate due to the feeling of being over-controlled. People who have recently been stopped and searched exhibit lower levels of belief in the legitimacy of the police (Jackson et al. Citation2013, Skogan Citation2006). Groups from disadvantaged backgrounds and ethnic minorities are more likely to undergo identity checks with possible searches, and are – somewhat paradoxically – most likely to accept the status quo of the social order (Jost, Banaji and Nosek Citation2004, Bowling and Phillips Citation2007, Medina Ariza Citation2014, Bradford Citation2016). Vulnerable groups may be reluctant to stand up for themselves by asking critical questions at the time of an interaction or to file a complaint after feeling wronged. This is an elementary drawback of a purely empirical approach to legitimacy. Citizens may consider a system in which certain groups are discriminated against, in which human rights are violated, etc., to be perfectly legitimate. The cited element of the influence of the social and political context on the national police culture (Chan Citation1997) is very relevant here. Social and political elements can shape the contours and weight of any legitimacy dialogue (Martin and Bradford Citation2021). Furthermore, it is uncertain what happens if police officers see their power called into question by contacts on the street with citizens or certain groups of citizens. The feeling of being ‘entitled to power’ is strongly linked to officers’ professional identity: questioning their authority or the way they interpret it could lead to an aggressive rather than reflexive reaction (Branscombe et al. Citation1999). Such questioning threatens a core part of officers’ ‘being’: the authority that is inherently connected to their professional identity. It is also conceivable that the dialogic character of self-legitimacy only fundamentally comes into play when the public, through serious and recurring signals, question the power of certain rulers and/or the way in which they shape it. Kochel (Citation2022) has shown how the ongoing protests in Ferguson that followed the death of Michael Brown (a black boy shot by a white police officer in circumstances that were contested by a large part of the community and the press – in the end the US Department of Justice concluded that the officer shot Michael Brown in self-defence) made police officers pause to consider whether some previously standard practices (such as proactive controls as part of crime prevention) did more harm than good to community relations, and made police officers reflect on whether they were unilaterally ‘the good guys’.

Legitimacy and self-legitimacy are not inherently ‘good’, and work remains – in police practice and research – to move beyond an instrumental focus on ‘procedurally just actions’ by the police in order to strengthen legitimacy and to find wider methods for enhancing police – public relations (Schaap and Saarikkomäki Citation2022). For example, a policy whereby police officers are required to provide a ‘receipt’ after an identity check, containing information about the officer who did the check, the reason for the check, the date/time/place of the check, etc., can be effective in raising awareness among police officers about the proportionate use of such interventions, and can facilitate citizens in asking questions about the check afterwards, where necessary. Several regions/countries, including Scotland and some regions in Denmark, exercise good practices of this sort. These can help the police organisation and its officers to maintain a more externally focused, audience-based perspective of themselves and can contribute to the organisation evolving into an entity that utilises more reflective learning.

It is quite possible that endogenous self-legitimation is the starting point of other legitimation practices. We saw how self-legitimacy influences normative orientations towards citizens and is, in this sense, a co-directing mechanism for the behaviour of police officers. The perspective of endogenous self-legitimation emphasises the importance of identification with the police organisation and with professional identity. Therefore, it is paramount that police officers achieve a balanced self-legitimacy that is embedded in and driven by a desirable normative framework. When both the police organisation and the professional identity are grafted onto a desirable normative framework, positive effects on police culture and behaviour would be expected. A strong identification with professional identity means that even minor changes in that socially constructed identity – the image police officers have of themselves and of their role in society – will have a major impact on the attitude of police officers. If we can bring about nuances in certain myths, stereotypes and ‘taken-for-granted’ attitudes that are currently linked to the professional identity of ‘being a police officer’, officers will be able to choose from a wider range of meanings and thus behavioural possibilities. A typical example is the myth of crime-fighters – research shows that most police work is not focused on law enforcement but consists of a wide range of social services (Wilson Citation1968, Punch and Naylor Citation1973, Bayley Citation1994, Verwee Citation2009). Yet for many police officers it remains their ‘raison d’être’, primordial in their professional identity (Smith and Gray Citation1985, Fielding Citation1988, Herbert Citation2001, Reiner Citation2010) and strongly linked to their self-legitimacy. When police officers see themselves primarily as ‘social mediators’ or ‘peacemakers’, this will influence their behaviour during interactions with citizens and can enhance police legitimacy. Structural reforms to police training can facilitate such a shift in and broadening of professional identity, as education, which is inherently a socialisation process, provides a mechanism for the transfer of particular values and ideas. Such self-definition need not be in complete contrast to the image of crime-fighters; it is about changing what is most central to the professional identity and what elements are on the periphery.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Mike Rowe for his valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Barker (Citation2001) speaks of endogenous legitimation and considers this a synonym for self-legitimation.

2 Tankebe (Citation2010) speaks of exogenous and endogenous legitimation; the concepts he uses are broader than the ones used in this article, where the terms ‘exogenous’ and ‘endogenous’ solely relate to self-legitimation processes.

References

- Akoensi, T.D., 2016. Perceptions of self-legitimacy and audience legitimacy among prison officers in Ghana. International journal of comparative and applied criminal justice, 40 (3), 245–261.

- Barker, R., 2001. Legitimating identities: the self-presentations of rulers and subjects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Barker, R., 2003. Legitimacy, legitimation, and the European union: what crisis? In: P. Craig, and R. Rawlings, eds. Law and administration in Europe: essays in honour of Carol Harlow. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 157–174.

- Bayley, D.H., 1994. Police for the future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Beetham, D., 1991. The legitimation of power. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Beetham, D., 2013. The legitimation of power. 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bell, J.B., 1982. Police uniforms, attitudes, and citizens. Journal of criminal justice, 10, 45–55.

- Bittner, E., 1974. Florence nightingale in pursuit of Willie Sutton: a theory of the police. In: H. Jacob, ed. The potential for reform of criminal justice. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 17–44.

- Bottoms, A. and Tankebe, J., 2012. Beyond procedural justice: a dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. The journal of criminal law and criminology, 102 (1), 119–170.

- Bottoms, A. and Tankebe, J., 2013. A voice within: power-holders perspectives on legitimacy. In: J. Tankebe and A. Liebling, eds. Legitimacy and criminal justice: an international exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 60–82.

- Bowling, B. and Phillips, C., 2007. Disproportionate and discriminatory: reviewing the evidence on police stop and search. The modern Law review, 70 (6), 936–961.

- Bradford, B., et al., 2014. Why do ‘the law’ comply? Procedural justice, group identification and officer motivation in police organizations. European journal of criminology, 11 (1), 110–131.

- Bradford, B., 2016. Stop and search and police legitimacy. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Bradford, B. and Quinton, P., 2014. Self-legitimacy, police culture and support for democratic policing in an English constabulary. The British journal of criminology, 54 (6), 1023–1046.

- Branscombe, N.R., et al., 1999. The context and content of social identity threat. In: N. Ellemers, R. Spears, and B. Doosje, eds. Social identity. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 35–58.

- Brockner, J., 1988. Self-esteem at work: research, theory, and practice. Boston: Lexington.

- Brough, P., Chataway, S., and Biggs, A., 2016. ‘You don’t want people knowing you’re a copper!’ A contemporary assessment of police organisational culture. International journal of police science & management, 18 (1), 28–36.

- Brown, M.K., 1988. Working the street: police discretion and the dilemmas of reform. 2nd ed. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Cain, M., 1973. Society and the policeman’s role. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Chan, J.B.L., 1997. Changing police culture: policing in a multicultural society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Charman, S., 2017. Police socialisation, identity and culture: becoming blue. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cochran, J.K. and Bromley, M.L., 2003. The myth(?) of the police sub-culture. Policing: An international journal, 26 (1), 88–117.

- Cohen, A.R., 1959. Some implications of self-esteem for social influence. In: C.I. Hovland and J.L. Janis, eds. Personality and persuasibility. New Haven: Yale University Press, 102–120.

- Coicaud, J.M., 2002. Legitimacy and politics: a contribution to the study of political right and political responsibility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Colquitt, J.A., et al., 2013. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: a meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of applied psychology, 98 (2), 199–236.

- Crank, J.P., 2014. Understanding police culture. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Di Palma, G., 1991. Legitimation from the top to civil society: politico-cultural change in Eastern Europe. World politics, 44 (1), 49–80.

- Festinger, L., 1954. A theory of social comparison processes. Human relations, 7, 117–140.

- Fielding, N.G., 1988. Joining forces: police training, socialization and occupation competence. London: Routledge.

- Fielding, N.G., 1994. Cop canteen culture. In: T. Newburn and E.A. Stanko, eds. Just boys Doing business: men, masculinities and crime. New York: Routledge, 46–63.

- Fine, G.A., 1996. Justifying work: occupational rhetorics as resources in restaurant kitchens. Administrative science quarterly, 41 (1), 90–115.

- Fletcher, C., 1996. ‘The 250Ib man in an alley’: police story telling. Journal of organizational change management, 9 (5), 36–42.

- Gau, M.J. and Paoline, E.A., 2019. Police officers’ self-assessed legitimacy: a theoretical extension and empirical test. Justice quarterly, 3 (2), 276–300.

- Graef, R., 1990. Talking blues: the police in Their own words. London: Fontana.

- Hall, D.T., 1987. Careers and socialization. Journal of management, 13 (2), 301–322.

- Herbert, S., 1996. Morality in low enforcement: chasing “bad guys” with the Los Angeles police. Law & society review, 30 (4), 799–818.

- Herbert, S., 1998. Police culture reconsidered. Criminology, 26 (2), 343–369.

- Herbert, S., 2001. ‘Hard charger’ or ‘station queen’? Policing and the masculinist state. Gender, place & culture, 8 (1), 55–71.

- Herbert, S., 2006. Tangled up in blue: conflicting paths to police legitimacy. Theoretical criminology, 10 (4), 481–504.

- Hotho, S., 2008. Professional identity – product of structure, product of choice: linking changing professional identity and changing professions. Journal of organizational change management, 21 (6), 271–724.

- Hough, M., et al., 2010. Procedural justice, trust and institutional legitimacy. Policing: A journal of policy and practice, 4 (3), 203–210.

- Ibarra, H., 1999. Provisional selves: experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative science quarterly, 44 (4), 764–791.

- Jackson, J., et al., 2012. Why do people comply with the law? Legitimacy and the influence of legal institutions. The British journal of criminology, 52 (6), 1051–1071.

- Jackson, J., et al., 2013. Just authority? Trust in the police in England and Wales. London: Routledge.

- Jermier, J.M., et al., 1991. Organizational subcultures in a soft bureaucracy: resistance behind the myth and facade of an official culture. Organizational science, 2, 170–194.

- Jonathan-Zamir, T. and Harpaz, A., 2014. Police understanding of the foundations of Their legitimacy in the eyes of the public: the case of commanding officers in the Israel national police. The British journal of criminology, 54 (3), 469–489.

- Jost, T.J., Banaji, M.R., and Nosek, B.A., 2004. A decade of system justification theory: accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political psychology, 25 (6), 881–919.

- Kappeler, V.E., Sluder, R.D., and Alpert, G.P., 1998. Forces of deviance: understanding the dark side of policing. 2nd ed. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press.

- Kleinig, J., 1996. The ethics of policing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kochel, T.R., 2022. Policing unrest: on the front lines of the Ferguson protests. New York: New York University Press.

- Loader, I. and Mulcahy, A., 2003. Policing and the condition of England: memory, politics and culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Loftus, B., 2009. Police culture in a changing world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Loftus, B., 2010. Police occupational culture: classic themes, altered times. Policing and society, 20 (1), 1–20.

- Maesschalck, J., 2019. Creatief met complementariteiten, contradicties en onhaalbaarheden: een verkenning van vier wegen naar een betere politiezorg. In: J. Noppe, A. Verhage, K. Van der Vijver, and E. Kolthoff, eds. Politie en legitimiteit (Vol. 4). Maklu: Cahiers Politiestudies, 13–29.

- Manning, P.K., 1977. Police work: the social organization of policing. Cambridge: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Manning, P.K., 1994. Police occupational culture: segmentation, politics and sentiments. unpublished manuscript. Michigan: Michigan State University.

- Manning, P.K., 1995. The police occupational culture in Anglo-American societies. In: W. Bailey, ed. The encyclopedia of police science. New York: Garland Publishing, 472–475.

- Manning, P.K., 2007. A dialectic of organisational and occupational culture. In: M. O’Neill, M. Marks, and A. Singh, eds. Police occupational culture: new debates and directions. New York: Elsevier, 47–83.

- Manning, P.K., 2008. Goffman on organizations. Organization studies, 29 (5), 677–699.

- Manning, P.K., 2010. Democratic policing in a changing world. New York: Routledge.

- Martin, R. and Bradford, B., 2021. The anatomy of police legitimacy: dialogue, power and procedural justice. Theoretical criminology, 25 (4), 559–577.

- Medina Ariza, J.J., 2014. Police-initiated contacts: young people, ethnicity, and the ‘usual suspects’. Policing and society, 24 (2), 208–223.

- Muir, W.K., 1977. Police: streetcorner politicians. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Nix, J., Pickett, J.T., and Wolfe, S.E., 2020. Testing a theoretical model of perceived audience legitimacy: the neglected linkage in the dialogic model of police–community relations. Journal of research in crime and delinquency, 57 (2), 217–259.

- Nix, J. and Wolfe, S.E., 2017. The impact of negative publicity on police self-legitimacy. Justice quarterly, 34 (1), 84–108.

- Noppe, J., 2016. Are all police officers equally triggered? A test of the interaction between moral support for the use of force and exposure to provocation. Policing & society, 28 (5), 1–14.

- Noyon, L., 2017. Visies op legitimiteit. In: P. Van Berlo, J. Cnossen, T.J.M. Dekkers, J.V.O.R. Doekhie, L. Noyon, and M. Samadi, eds. Over de grenzen van de discipline: interactions between and within criminal law and criminology. Den Haag: Boom Juridische Uitgevers, 147–165.

- Paoline, E.A., 2003. Taking stock: toward a richer understanding of police culture. Journal of criminal justice, 31, 199–214.

- Pierce, J.L., et al., 1989. Organisation-based self-esteem: construct definition, measurement and validation. Academy of management journal, 32 (3), 622–648.

- Pierce, J.L. and Gardner, D.G., 2004. Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: a review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of management, 30 (5), 591–622.

- Price, T., 2006. Understanding ethical failures in leadership. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Punch, M. and Naylor, T., 1973. Police-social service. New society, 24 (554), 358–361.

- Reiner, R., 1985. The politics of the police. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reiner, R., 2010. The politics of the police. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rubinstein, J., 1973. City police. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Rumbaut, R.G. and Bittner, E., 1979. Changing conceptions of the police role: a sociological review. In: N. Morris and M. Tonry, eds. Crime and justice: an annual review of research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 239–288.

- Schaap, D. and Saarikkomäki, E., 2022. Rethinking police procedural justice. Theoretical criminology, 26 (3), 416–433.

- Schein, E.H., 1978. Career dynamics: matching individual and organisational needs. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

- Shearing, C.D., 1981. Organizational police deviance: Its structure and control. Toronto: Butterworth.

- Shearing, C.D. and Ericson, R.V., 1991. Culture as figurative action. The British journal of sociology, 42 (4), 481–506.

- Singer, M.S. and Singer, A.E., 1985. The effect of police uniform on interpersonal perception. The journal of psychology, 119, 157–161.

- Sklansky, D.A., 2006. Not Your father’s police department: making sense of the new demographics of law enforcement. Journal of criminal law and criminology, 96 (3), 1209–1243.

- Skogan, W., 2006. Asymmetry in the impact and encounters with the police. Policing and society, 16 (2), 99–126.

- Skolnick, J., 1966. Justice without trial. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Skolnick, J. and Fyfe, J.J., 1993. Above the law: police and the excessive use of force. Current issues in criminal justice, 5 (2), 226–228.

- Smith, D.J. and Gray, J., 1985. Police and people in London. Gower Publishing: Aldershot.

- Sparrow, M.K., Moore, M.H., and Kennedy, D.M., 1990. Beyond 911: a new era for policing. New York: Basic Books.

- Tajfel, H., 1982. Social identity and intergroup relations. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Tankebe, J., 2010. Legitimation and resistance: police reform in the (un)making. In: K. L. Cheliotis, ed. Roots, rites and sites of resistance: the banality of good. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 197–219.

- Tankebe, J., 2013. Viewing things differently: the dimensions of public of police legitimacy. Criminology, 51 (1), 103–135.

- Tankebe, J., 2014. Rightful authority: exploring the structure of police self-legitimacy. In: A. Liebling, J. Shapland, and J. Tankebe, eds. Crime, justice and social order: essays in honour of A.E. Bottoms. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–30.

- Tankebe, J., 2018. In Their own eyes: an empirical examination of police self-legitimacy. International journal of comparative and applied criminal justice, 43 (2), 99–116.

- Tankebe, J. and Meško, G., 2015. Police self-legitimacy, use of force, and pro-organizational behavior in Slovenia. In: G. Meško, and J. Tankebe, eds. Trust and legitimacy in criminal justice: European perspectives. New York: Springer, 261–277.

- Trinkner, R., Kerrison, E.M., and Goff, P.A., 2019. The force of fear: police stereotype threat, self-legitimacy, and support for excessive force. Law and human behavior, 43 (5), 421–435.

- Tyler, T., 1990. Why people obey the Law. Yale: Yale University Press.

- Tyler, T., 2004. Enhancing police legitimacy. Annals of the American academy of political and social science, 593, 84–99.

- Tyler, T., 2006. Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual review of psychology, 57, 375–400.

- Tyler, T, 2009. Legitimacy and criminal justice: the benefits of self-regulation: Walter C. Reckless-Simon Dinitz Memorial Lecture. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 7 (1), 307–360.

- Tyler, T., 2011. Trust and legitimacy: policing in the US and Europe. European journal of criminology, 8 (4), 254–266.

- Van Craen, M. and Skogan, W.G., 2017. Achieving fairness in policing: the link between internal and external procedural justice. Police quarterly, 20 (1), 3–23.

- Van Maanen, J., 1974. Working the street: a developmental view of police behavior. In: H. Jacob, ed. The potential for reform of criminal justice. Beverly Hills: Sage, 83–130.

- Verwee, I., 2009. Wat doet de politie? Onderzoek naar de dagelijkse politiepraktijk. In: I. Verwee, E. Hendrickx, and F. Vlek, eds. Wat doet de politie? (Vol. 4). Maklu: Cahiers Politiestudies, 37–66.

- Waddington, P.A., 1999. Police (canteen) sub-culture: an appreciation. The British journal of criminology, 39 (2), 287–309.

- Walker, S., 1999. The police in America: an introduction. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Weber, M., 1978. Economy and society: an outline of interpretive society (eds. Roth G and Wittich C). Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- White, D.R., Kyle, M.J., and Schafer, J., 2020. Police officer self-legitimacy: the role of organizational fit. Policing: An international journal, 43 (6), 993–1006.

- Wilson, J.Q., 1968. Varieties of police behavior: the management of law and order in eight communities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Wolfe, S.E. and Nix, J., 2017. Police officers’ trust in Their agency: does self-legitimacy protect against supervisor procedural injustice? Criminal justice and behavior, 44 (5), 717–732.

- Wolfe, S.E. and Piquero, A.R., 2011. Organizational justice and police misconduct. Criminal justice and behavior, 38 (4), 332–353.

- Wrong, D., 1995. Power: its forms, bases and uses. New York: Routledge.