ABSTRACT

Despite concerns having been voiced internationally about the validity and reliability of mobile phone evidence, there remain large gaps in our understanding of how police acquire and process mobile phone data, and the risks associated with this work. This paper fills some of these gaps by drawing upon qualitative data gathered during an ethnographic study of the role of forensic sciences and technologies in British homicide investigations. Specifically, we draw upon case papers, interviews, and observations to illuminate, from the perspective of police and prosecution actors, some of the opportunities, tensions, and risks encountered in accessing and processing mobile phone data during these inquiries. Our findings reveal several risks associated with current practice alongside broader complexities related to legislation, privatisation, and accreditation. We consider how these intertwined risks and challenges may undermine the reliability of mobile phone evidence and jeopardise criminal justice.

Introduction

Digital evidence is encountered frequently within criminal investigations and trials. It provides investigators with new opportunities to gather evidence and is surpassing traditional investigative approaches, such as witnesses, fingerprints and DNA in terms of frequency of use (Her Majety’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services, HMICFRS Citation2022). Digital evidence can be obtained from a growing number of devices; for instance, mobile phones, computers, smart watches, connected home appliances, and the internet of things. In particular, mobile phone data play an increasing role in police investigations and court cases (Richardson et al. Citation2022) and are prominent in many homicide investigations (Brookman and Jones Citation2022). This is unsurprising, given that mobile phones offer a wealth of personal information that can, as the Information Commissioner’s Office note, ‘reveal patterns of our daily personal and professional lives and enable penetrative insights into our actions, behaviour, beliefs, and state of mind’ (ICO Citation2020, p. 2). Furthermore, in the UK, for example, 88% of adults owned a smartphone in 2021 (Hiley Citation2023).

Homicide investigators use call data, cell site data and/or mobile phone downloads – often in conjunction with other evidence – to identify (and eliminate) potential suspects, corroborate a sequence of events, and refute suspects’ accounts (Wilson-Kovacs et al. Citation2024). However, the growing use of mobile phone data during police investigations has been accompanied by mounting concerns about how police handle these data. For example, the increasing complexity and volume of data held on handsets threaten to overwhelm the capacity of many police forces (Casey Citation2019a), resulting in technical difficulties in recovering all data from mobile phones (Reedy Citation2020) and backlogs in workloads (HMICFRS Citation2022). Concerns also revolve around knowledge and expertise. To elaborate, while the boundaries of expertise are well established within traditional forensic sciences, they are less well defined within newer digital disciplines (Tart et al. Citation2019). Reiber (Citation2019) argues that because examiners rely on automated tools, most have a limited understanding of the processes that underpin their examinations, leading some commentators to describe mobile phone forensics as ‘the “Wild West” of digital forensics – just point and click’ (p. xvii). Compounding these issues are inadequate quality assurance systems (Page et al. Citation2019) and a lack of ‘universally accepted standards and competencies’ within digital forensics (Vincze Citation2016, p. 192). For example, in the UK, new regulatory requirements for using cell site analysis for geolocation are not set to be accredited to international standards until October 2025 (Forensic Capability Network Citation2023). Finally, there are growing concerns about the reliability of digital evidence. Notably, socio-legal analyses have highlighted an increasing number of miscarriages of justice relating to digital evidence (Helm Citation2022) and the proportion of appeal judgements referencing mobile phones has increased in recent years (Richardson et al. Citation2022).

While the socially constructed nature of forensic evidence has long been argued amongst science and technology studies scholars (e.g. Jasanoff Citation2006, Lynch et al. Citation2008), attention has focused on traditional forensic methods, such as DNA or fingerprinting (e.g. Kruse Citation2016), rather than digital evidence. However, digital evidence, like other forms of forensic evidence, is not ‘an objective “fact” just waiting to be discovered at the crime scene’ (Julian et al. Citation2022, p. 92). Rather, digital traces undergo a series of complex interpretive processes by numerous criminal justice actors, with varying levels of competency and expertise (Casey Citation2019a). At each stage of the criminal justice process, risks of ‘mishandling, misinterpretation, misunderstanding, and manipulation’ exist, which may threaten the integrity of the data (Casey Citation2019b, p. 1) and trustworthiness of conclusions drawn about it.

To date, little research has considered how mobile phone data are accessed and processed by police and the risks associated with this work. Based on qualitative data drawn from a four-year ethnographic study of the role of forensic sciences and technologies in British homicide investigations, we begin to address this gap in knowledge. Specifically, through detailed fieldwork with homicide detectives, intelligence analysts, digital evidence practitioners, digital media investigators, and barristers, we explore the investigative opportunities afforded by mobile phone data. We also discuss the challenges police face when accessing handsets, acquiring call data records, managing the burgeoning volume of mobile phone data, and managing disclosure, as well as broader complexities related to legislation, privatisation, and accreditation. In so doing, we illuminate, from the perspective of police and prosecution actors, some of the tensions, challenges and risks encountered in using mobile phone data during these inquiries, and the consequences these may have for defendants and their lawyers. Homicide investigation provides an especially useful lens through which to examine the use of mobile phone evidence. These investigations are resource intensive and often involve multiple specialised actors and ‘gold standards’ of investigation and so are a test ground for the robustness of police practice (Brookman, Citation2022). The stakes are high as the impacts of mistakes or poor practice can be profound in serious offences, such as homicide, leading to wrongful imprisonment (Julian et al. Citation2012).

We begin by presenting some technical information about mobile phone data and the journey of handsets within homicide investigations, revealing the kinds of data that are interrogated and the array of actors involved. This helps to contextualise the social interactions and decision-making that we discuss later.

Acquiring and processing mobile phone data and evidence

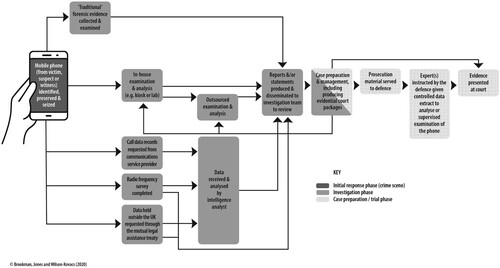

shows the kinds of data acquired from mobile phones during a homicide investigation and how evidence is processed. This is a simplified depiction, and the process may be more complicated and protracted than shown, depending on the nature of the homicide and kind of data sought. Nevertheless, it outlines the journey that data can take from crime scene to court. also highlights that some examinations are performed in-house, whereas others are outsourced to private digital forensic laboratories, depending on the police force involved, their capacity and/or the complexity of the examination required.

Figure 1. Criminal justice process chart illustrating how data from a mobile phone are acquired and evidence processed during a homicide investigation.

Elaborating on , a mobile phone can contain a wide range of data, for example, contact lists, SMS (Short Message Service, i.e. text messages), MMS (Multimedia Messaging Service, i.e. text messages containing pictures or videos), call logs, stored voicemails, photographs, e-mails, web browsing history, social media, as well as additional data held in applications (Casey and Turnbull Citation2011, Reiber Citation2019). Each handset has an IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity) number – a unique serial number that can be used to identify the handset (Casey and Turnbull Citation2011). The handset also contains (or will have contained) a SIM (Subscriber Identity Module) card that enables the phone to connect to a network and which, if seized, can provide examiners with the content of text messages – in some instances, the SIM card will have been swapped between handsets (Gogolin Citation2021). Moreover, some phones work with dual SIM cards, enabling the user to have two different phone numbers within the one handset.

Police can request call data records (CDRs) from communications service providers; these records are linked to the SIM card and provide details of calls and texts made from/to the mobile phone, such as the date and time of the call/text, the duration of the call, and the phone number receiving the call/text (Tart et al. Citation2012, p. 185). CDRs also provide details of the cell used for each call/text made (Hoy Citation2015, p. 255). However, these records only include calls that connect (i.e. those answered by a person or voicemail service) and while the cell where the call began is included (start cell), the end cell is only included in some CDRs (Tart et al. Citation2012, p. 185). Furthermore, CDRs do not provide details of any cells used in between the start and end cells and, for text messages, usually only include the start cells because of how quickly messages are sent (Forensic Analytics Citation2020, p. 11). Also included in CDRs are GPRS (General Packet Radio Service) data, which refer to mobile data shared via 2G networks as well as 3G, 4G and 5G – although across these networks, ‘mobile data’ is the more accurate descriptor (Forensic Analytics Citation2020, p. 4). GPRS data may be used when web browsing, emailing, or using applications, and the nature of these data mean that data sessions may be open for a long time (Forensic Analytics Citation2020, p. 4). In comparison with calls or text messages, it is difficult to determine accurately the timestamp for GPRS data (Hoy Citation2015, p. 268–271). Lastly, CDRs are used frequently in conjunction with a radio frequency survey to determine where a phone may (or may not) have been located when used, referred to as ‘cell site analysis’ (Tart et al. Citation2012, Hoy Citation2015).

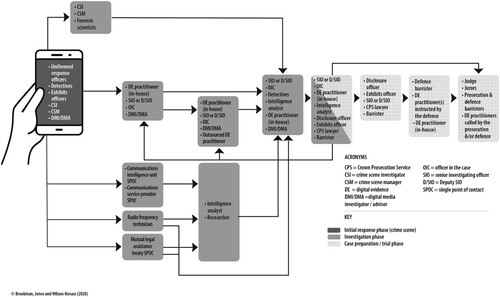

Numerous criminal justice actors are involved in gathering, interpreting, presenting and receiving mobile phone data and evidence, as set out in .

Figure 2. Process chart illustrating the criminal justice actors involved in acquiring data and processing, presenting and receiving evidence from a mobile phone during a homicide investigation.

Taken together, and point to the multitude of processes and criminal justice actors involved in extracting and making sense of mobile phone data, and the complexity of this endeavour. Data may be examined by (1) a police analyst or someone who is not a digital evidence practitioner, (2) a digital evidence practitioner who is employed by a police force, or (3) a digital evidence practitioner who is employed outside of the police (e.g. by a private service provider or government agency). There are also various other actors involved, including police officers/staff (e.g. exhibits officers, digital media investigators), specialists who may be employed by either the police or private service providers (e.g. radio frequency technicians), and legal professionals (who work for the Crown Prosecution Service, CPS, or defence). Crucially, the eventual evidence that is gleaned is socially constructed by these various criminal justice actors, through processes of interpretation.

Despite concerns having been voiced about the validity and reliability of mobile phone evidence, there remain large gaps in our understanding of how police acquire and process mobile phone data. Moreover, few academic studies have appraised these challenges from a social science perspective, instead drawing on case studies (e.g. Collie Citation2018) or small-scale experiments (e.g. Van Zandwijk and Boztas Citation2021). Our aim in this paper is to report findings from our interviews with, and observations of, an array of criminal justice actors as they make use of mobile phone data during the investigation of homicide in Britain. Our primary focus is to illuminate, from the perspective of police and prosecution actors, the challenges of acquiring and processing mobile phone data, and the attendant risks (we dedicate a second paper to exploring how mobile phone data are interpreted and transformed into evidence). Next, we briefly describe the methods of data collection and analysis used in the present study, before presenting our findings and discussing their implications.

Data and methods

The data that we draw upon in this paper were gathered during a four-year ethnographic study of the use of forensic sciences and technologies in British homicide investigations. The research aimed to provide an in-depth understanding of how a broad range of forensic sciences and technologies contributes to the police investigation of homicide, such as DNA profiling, fingerprint examination, blood pattern analysis, toxicology, and digital evidence from mobile phones and CCTV. The study examined 44 homicide investigations undertaken across four police forces. All offences, except for two, took place between 2011 and 2017. Thirty-three investigations were completed (or almost completed) at the time of data gathering (i.e. a guilty verdict of murder or manslaughter was reached at court or agreed through pleas). These completed cases were sampled from summary lists provided by each police force to reflect a diverse range of homicide cases and forensic contributions. In addition, we observed 11 live investigations as they unfolded, including two where the victims unexpectedly survived their injuries. Although the selection of live investigations was less structured, in aggregate they represent the diversity reflected in the completed investigations. The 44 cases studied include a range of modus-operandi, victim-offender relationship, motive, circumstance and forensic contributions. They also include cases where suspects were identified very quickly through to complex, protracted investigations.

The research comprised three main methods – document analysis, interviews, and observations. For each investigation, we retrieved case papers and/or made extensive notes from documents, for example, senior investigating officers’ policy files, strategy documents, and statements and reports from forensic scientists and other experts. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 134 criminal justice actors – 118 of whom were involved directly in one of the 44 cases studied. All interviews (except one) were digitally recorded and transcribed, with an average length of 83 minutes. We also conducted ten informal interviews with forensic practitioners during tours of forensic science facilities. The third phase of the research was the most immersive and involved ethnographic observations, during which we spent 700 hours observing different moments of 11 live homicide investigations, from the initial crime scene attendance through to trials at court. We wrote, and later typed up, detailed fieldnotes.

Interview transcripts, fieldnotes, case papers and notes made from these were all uploaded into NVivo 12 and analysed thematically (Braun and Clark Citation2006). This involved engaging regularly with the data and ultimately creating memos containing reflections, and higher level and lower order nodes of thematic and conceptual categories, in accordance with grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss Citation2008). For the purposes of this paper, we focus upon nodes that reflect processes, practices, challenges or risks associated with using mobile phone data, for example, ‘digital data challenges or complexities’, and broader nodes including ‘disclosure’, ‘errors and mistakes’, and ‘legislation that impacts investigations’. We draw upon data from case papers, interviews and observations.

Gaining access to the closed world of homicide investigation can be difficult given the sensitive nature of the work of homicide detectives. The experience of the research team, plus established relationships with key stakeholders and gatekeepers, were central to negotiating access to research sites and our ongoing efforts to access people, places, and events (see also Brookman and Jones Citation2024). Ethical approval for the research was granted by the University of South Wales Research Ethics Committee. The research was conducted in accordance with the British Society of Criminology code of ethics (Citation2015), with particular attention to the issues of informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, and stringent data management protocols. To preserve anonymity, all reported data relating to research participants and cases have been disguised, which includes using pseudonyms and altering dates. We turn now to research findings.

Findings

In this section, we briefly discuss how mobile phone data contribute to homicide investigations, before examining several challenges and risks associated with current practice.

How mobile phone data contribute to homicide investigation

Homicide detectives pursue many different investigative avenues during homicide investigations. In the cases we studied, mobile phone data (including call data, cell site data, and/or downloads) ranked second to CCTV in terms of the frequency with which they were used to identify and charge suspects (Brookman and Jones Citation2022). Different kinds of mobile phone data were routinely combined with other kinds of evidence, to substantiate or connect key points of evidence (Innes et al. Citation2021).

Data extracted from mobile phones or call data records can sometimes provide detectives with investigative avenues that are rarely afforded by other forensic scientific techniques. For instance, in our cases, text messages seemingly provided investigators with insight through which to infer internal mental states, such as motive, intent, and mental capacity, as well as ‘victimology’, helping to reveal victims’ routine activities and interactions. Call data helped to determine association between co-suspects, and cell site data indicated their movement and direction of travel and were particularly valuable in those cases that lacked witnesses or CCTV. Uniquely, in one case involving a fatal stabbing, a specialist technique was used to examine an image of the recovered murder weapon, taken before the offence, and found on the suspect’s mobile phone. The suspect alleged that he had received the image to his handset from the victim. A forensic practitioner determined that the suspect had photographed the knife on his handset. This evidence was considered to have led the suspect to plead guilty to murder. Despite the opportunities afforded by mobile phone data, numerous challenges were encountered by detectives in making use of these devices.

Challenges of acquiring and processing mobile phone data in homicide investigations

Accessing and processing mobile phone data can be difficult tasks. We begin by discussing separately the challenges of accessing data on handsets and acquiring call data records (CDRs). It is worth noting that while mobile phone downloads require an expert to abstract the data, data from CDRs do not require forensic extraction or examination. Rather, CDRs are provided by a communications service provider and interrogated by intelligence analysts. We then discuss the challenges associated with interrogating mobile phone data before considering the complexities of disclosure.

Accessing data on handsets

Seizing handsets can be problematic because some suspects go to extreme lengths to conceal and/or destroy them. If and when handsets are seized, investigators face challenges in accessing (promptly) all data stored on the handset.

Investigators spoke frequently of their frustrations in ‘breaking into’ suspects’ mobile phones because of advanced levels of privacy and encryption offered by mobile phone companies, as illustrated in the following extract from an interview with a senior investigating officer (SIO):

Well technology has developed, so law enforcement agencies have been working on cracking these phones. At the same time, the technology companies are looking at ways of stopping us doing it … So they’re building in security measures which make it more difficult again for us to get into this material. So, it’s a constant battle. (SIO, Operation C04)

Participants also explained how message content was becoming more difficult to retrieve from handsets because of increasing levels of encryption, for example, on WhatsApp, or because applications have been developed that delete messages quickly, for example, Snapchat (see also Gibbs Van Brunschot et al. Citation2022). Furthermore, several analysts and investigators discussed their concerns about the increasing number of calls and messages taking place over applications such as WhatsApp, Snapchat, and Facebook Messenger that use wi-fi or GPRS data, rather than a network. Without a handset, these communications are hidden because CDRs do not record wi-fi data or only show that the internet was accessed through a GPRS session. This trend hampers police attempts to corroborate or refute lines of enquiry.

Police frequently lacked the capability (and sometimes capacity) to access handsets. Instead, handsets were sent to private companies in the UK or abroad, or to the National Technical Assistance Centre (a government unit). However, outsourcing examinations was not straightforward. Police had to consider the financial implications of sending handsets to private providers. Following one investigation, we observed a debrief where investigators discussed how they had been unable to access an iPhone 5 that belonged to one of the victims because it was pin protected. The deputy senior investigating officer (D/SIO) was reflecting on the cost of sending such handsets to private companies and a discussion ensued about how they might be able to resolve this challenge in future investigations:

There have been a couple of times now that we couldn’t get into phones … there are ways [to break into them]; there’s just a huge financial cost to it …

Could you use the victim’s thumbprint instead of the pin?

No, we can’t use a thumbprint after the phone has been turned off – you need the pin

Is it an option to keep the phone charged after it’s been seized? If the phone isn’t being used, then it should stay powered?

But it’s then what you do – do you change the pass code? But you need a pin code to change it

Could you change the settings, so it never locks? But then you don’t want to alter it

We also need to conform to RIPA

It’s an interesting one – the issue of interference.

(Extract from fieldnotes, Operation N13)

Police also balanced the financial implications of sending handsets to private providers against the likelihood of receiving useful results:

We certainly do use outside providers to break into phones that we can’t access, but again, that comes at quite a cost, and you can’t guarantee what data you’re going to get back. Sometimes it’s worth every penny. We’ve had one back recently, we’ve actually got nothing evidential from that. (Intelligence Analyst, Operation E12)

Due to the various aforementioned challenges, police sometimes resorted to using non-validated tools to access data held on handsets, undermining the potential robustness of any evidence gleaned (Horsman Citation2018). However, as forces began working towards the accreditation of digital forensic processes (which are now legislated under the Forensic Science Regulator Act Citation2021), practices appeared to be changing:

That’s changed slightly with the ISO standards, now that [the digital forensic unit] have to follow set procedures for phones, whereas before … they used to be able to do their own research … it’s almost like a hobby to a lot of them … they can find new ways of getting data off the phone. They’re not allowed to do that anymore, so it’s very restrictive. (Intelligence Analyst, Operation E12)

Acquiring call data records

Alongside downloading data from mobile phones, police invariably seek to acquire associated call data records (CDRs), the process for which was governed (at the time of our fieldwork) by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act Citation2000 (RIPA).Footnote2 However, several challenges confront police when attempting to navigate this legislation.

Acquiring communications data through RIPA was felt, by many investigators, as unnecessarily burdensome. Specifically, investigators spoke about the time it took to complete a RIPA application and how requesting communications data had become more complicated and convoluted in recent years:

It takes an awful lot of time to justify, for every application, why it’s proportional, why it’s necessary, why it’s legally required, etc … Ten years ago … to get a subscriber check done from the early mobile phone companies was a phone call to one person in headquarters. You’d probably get it back within a reasonable amount of time. Now there’s an entire department in headquarters that deal with it and it is a flurry of emails back and forth because they have to satisfy the Information Commissioner who comes in regularly to audit and inspect what they do. So, they push back on us, on what they perceive to be unjustifiable applications. We have to fine tune them to get them through their gatekeeper, and then they pass it on to the authorising officer, who is the Superintendent. He or she has got different ways of analysing that application. It might get kicked back at any one of those stages and again, it just takes time. (SIO, Operation C04)

The biggest challenge is, so each force has a CAB office, so that’s the Covert Authorities Bureau, and they’re the ones, where our SPOC [specific point of contact] sits, that’s who deals with our telecoms applications. Now although they all work under RIPA, and that is ultimately the regulations that allow us to have the data, each CAB office have their own interpretations of what we should be getting and how. So, in particular, XXX will not approve as much data as YYY CAB office will. So here [YYY], we’ll look quite often for a month’s worth of call data, so we can lifestyle a suspect. If someone’s in contact on the day of the offence, if you’ve only got one day’s data that might be really stand out, but, if over a month they contact them the same time every day, it’s meaningless. But in XXX they will only let you have two or three days, as a rule, to start with and it’s a real battle to get any more than that. They’ll say, no, get your two or three days, if there’s nothing we’ll go wider, then we’ll go a bit wider. Obviously, the knock-on effect in timeliness is just crazy … I think there’s certainly lines of enquiry we have missed because we’ve not got data quick enough. (Intelligence Analyst, Operation E12)

… [RIPA], which was written and came into play in 2000. Well, that’s so out of date when you think of how technology’s changed … at the minute we have to apply some quite clunky old legislation to new technologies and try and make sure we’re doing it within a legal framework … it will cause us some test cases in the future, I’m sure. (SIO, Operation E02)

Burgeoning data volume

Police face significant resource challenges in dealing with mobile phone data. First, there are often limited resources within digital forensic units to undertake potentially huge downloads of the vast number of handsets seized during a homicide investigation, resulting in delays in handsets being examined. Second, it is not possible for police to interrogate all handsets seized, due to the sheer volume of data contained on a typical handset (ICO Citation2020). Third, there are often insufficient staff (within major crime) to review and analyse downloads and associated CDRs. In the following sections, we explore how police decided which handsets to prioritise for examination and which data to interrogate. These decisions undoubtedly have a bearing upon what information is ultimately discovered about suspects, victims, and others with whom they communicate.

Prioritising handsets for examination. Our observations uncovered various ways that SIOs, in conjunction with, for example, the exhibits officer and intelligence analyst (and in some police forces, the digital media investigator, DMI) prioritised handsets for examination. These included assessments of how new handsets appeared to be, and how recently and where they had been used, as illustrated in the following fieldnote extract made during observations of a team briefing that included discussion of the suspect’s mobile devices, a laptop, and a base unit:

How should we prioritise the suspect’s devices?

We need to sit down and will be guided by you. I suggest that we prioritise them around usage, how new they look, etc.

We have the IMEIFootnote3 and I can send that to show most recent usage

It will be useful to prioritise the phone in the car as that’s out and about. The DMI and I will have a sit down after this meeting, assisted by the IMEI information, and confirm the prioritisation matrix.

(Extract from fieldnotes, Operation C01)

Some academics (e.g. Wilson-Kovacs Citation2019) have begun to explore how police use a triaging process at crime scenes. This involves using specialist tools or software to prioritise which handsets to seize and to examine in-depth. While investigators at all four forces referred to triaging handsets, it was not clear how formalised these processes were, whether they used tools or software to assist, or whether they were referring more broadly to how they prioritised handsets. Guidance for (homicide) investigators is limited. For example, the Major Crime Investigation Manual simply advises SIOs that ‘[d]igital opportunities should be triaged, taking into account proportionality and the resource, storage, analysis and disclosure demands … ’ (National Police Chief’s Council, NPCC, Citation2021, p. 101). In most police forces, self-service digital forensic kiosks have been introduced for frontline staff or non-digital forensic practitioners (NPCC Citation2020). Depending on force policy, kiosks might be used as a triage and/or analysis tool. However, using this triage tool comes with risks during major crime investigations such as homicide, as illustrated in the following interview extract:

So, the suspect’s mobile phone in a murder, you wouldn’t probably get your guy that has got one-day training to run it past a kiosk and see what he can get out of it, you want somebody more specialist or techniques that are finely honed to examine that phone. (Digital forensics senior manager, Woodvale)

Determining what data to interrogate. Once decisions have been made about which handsets to examine, a host of further decisions must be made about what data, from the voluminous amounts held on the handset, to interrogate. This also involves selecting which CDRs to request from service providers.

To reduce the amount of data that are requested, retrieved, and reviewed, intelligence analysts devise a strategy with the SIO, detailing what they wish to examine and why. In the following example, this was achieved by setting different date parameters for the victim’s and suspect’s CDRs, and directing how the data were to be reviewed (the suspect was accused of killing a female relative in a sexually motivated attack after consuming cocaine):

Call data will be obtained from 1st July – 31st July for any phones attributed to the victim. To establish recent contacts and key associates who may be of interest to the investigation

Call data will be obtained for phones attributed to the suspect from 1st February – 31st July, which covers the breakdown of his relationship with XXX

o To identify who the suspect was in contact with prior to and after the incident

o Cell site analysis will assist with understanding the suspect’s movements both before and after the incident which will assist with CCTV opportunities

o To identify any possible relationships which may have occurred since the breakdown of the suspect’s relationship with XXX(Summary of extract from Document 53 – Telephone Strategy, Operation E07)

Reviews of forensic downloads will include:

o Phones attributed to the suspect – images will be categorised into those of a violent or sexual nature, or relating to drug use

o Phones attributed to the victim – review message history to identify if she expressed any concerns in relation to the suspect’s mental health/behaviour, and if any show the type of relationship they had

o Phones attributed to suspect’s ex-girlfriend – review all images to identify any of a sexual nature involving a male. This is to assist with identifying the nature of the sexual preferences/activities involving the suspect(Summary of extract from Document 53 – Telephone Strategy, Operation E07)

These extracts from a strategy document reveal the rationale for each review activity associated with the CDRs or downloads. Whether these decisions are proportionate is debatable – notably the examination of (potentially intimate) images of the suspect’s ex-girlfriend that may have led to unnecessary intrusion into both her life and those of others whose images were stored on her phone (ICO Citation2020). In some instances, the strategy document also outlined how investigators planned to use the findings. This included identifying the suspect’s movements, assisting with CCTV enquiries, identifying sexual preferences, and identifying evidence of mental health. This seemingly straightforward task involves working with data that may be imprecise or unclear. For example, CDRs are produced to charge customers and their accuracy for policing purposes are uncertain (Lentz and Sunde Citation2021). Similarly, cell site analysis is not definitive (Hoy Citation2015). Finally, interpreting content on mobile phones to infer sexual preferences or mental health is fraught with difficulties and open to misinterpretation (Ramirez Citation2022).

Lastly, to assist with their interrogation of large volumes of data, police use search tools, such as keywords, to identify relevant material from mobile phone downloads. While this is common practice (Metropolitan Police Service, MPS, and CPS Citation2018), the extract that follows, from an intelligence analyst’s report, illustrates how it is influenced by the applications and kinds of words that investigators deem pertinent to the investigation:

Keyword searches performed for text messages and messages recovered from WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Snapchat – around themes of violence, drug use, sex and suspect’s relationship with [the victim]. (Extract from Report 11F, Operation E07)

Managing disclosure

Given the vast amount of data now held on mobile phones it has become impossible for investigators to review all data, resulting in inadequate pre-trial disclosure (McCartney Citation2018). To illustrate, the case of Liam Allan (falsely accused of rape and sexual assault) highlights significant disclosure failings by the police in relation to data downloaded from the complainant’s mobile phone (Smith Citation2018). The MPS and CPS (Citation2018, p. 6) determined that the problem stemmed from ‘a combination of error, lack of challenge, and lack of knowledge’, rather than data being withheld deliberately. Nevertheless, this case has garnered adverse media attention and accusations of systemic failings in the disclosure process (Berkeley Square Solicitors Citationn.d.). One SIO spoke in depth about disclosure practices within their police force, highlighting a lack of training and understanding in handling large volumes of data:

… we’ve got to be able to understand what we’ve got, what we haven’t got, to be able to assess, not only if there’s any evidential material, but if there’s anything that undermines the defence … everybody has got a phone, at least one, and they are computers, they contain huge, huge volumes of data … unfortunately I think people see things sometimes as an administrative function … it’s to do with a lack of training. Major crime officers are trained … trained to use a computer system, but not on what disclosure is about and I don’t think people understand it and it’s become this big scary thing. When you combine that with material on phone downloads … a Nokia 3310 ten years ago or bloody fifteen years ago, it was very straightforward, you had text messages. It’s so much more complicated now with all these different platforms and different ways people are communicating. (SIO, Operation C06)

But a 64GB phone, which is a fairly bog-standard phone these days, is impossible to examine in its entirety, it’s impossible, and yet we’re still, as investigators, held to a standard … So CPIA requires us to retain, review and reveal all unused material. So, a phone that has got material in it, CPIA would say if it’s relevant you need to review it but that’s physically impossible. It is physically impossible for us to do that now. (SIO, Operation C04)

CDRs may show drug dealing relevant content but I wouldn’t set about the onerous task of redactions. We’ll deal with more particular requests for disclosure. How much data do we have?

10,000 rows of data plus mobile downloads

I’m tempted to give them all 10,000 rows of data.

(Extract from fieldnotes, Operation C02)

We need to contend with their request for disclosure. I’ve just come from a meeting with the CPS and one of the big messages was that we need to be more brutal in terms of what we offer up with disclosure. If it’s not relevant, it doesn’t come in. If they want to put in a Section 8 application,Footnote5 then fine. We’ll stick to our guns. (Extract from fieldnotes, Operation C02)

Conclusion

The findings reported in this paper provide insight into how one type of (relatively) new technology is used by investigators during homicide investigations, the multitude of actors and interests involved and, in turn, some of the tensions inherent in this evolving form of police work. Through detailed fieldwork with the many different police actors involved in making decisions about whether and how to use mobile phone data, we have illuminated some of the investigative opportunities afforded by these data, as well as the dilemmas, challenges, and risks that police confront. The findings provide a rare glimpse into some of the processes and practices that have emerged to manage the unmanageable – in terms of volume of handsets and data – in a criminal justice context that lacks accreditation and adequate legislative framework. Here we summarise the key findings before moving on to consider their implications for criminal justice.

Our findings demonstrate numerous challenges inherent in acquiring and processing mobile phone data. First, police must deal with increasing levels of security, privacy, and encryption, which may thwart their attempts to unlock handsets or render data held on applications inaccessible. Second, police often do not have timely access to data due to delays in examining handsets (as a result of backlogs in digital forensic units), lengthy waits for bespoke assistance from an external provider, or convoluted application processes for requesting call data records. Third, police are confronted with significant volumes of handsets and data to interrogate that outstrip capacity. Fourth, police perceive some of the legislation that frames their attempts to gather and process data as outmoded and unhelpful, preventing them from dealing effectively with (rapidly) advancing technology. Police perceive the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act Citation2016 (RIPA) as largely ineffective in terms of compelling suspects to disclose their mobile phone pin number without which, they must find other (sometimes risky) ways of accessing handsets. The procedure for acquiring call data records often involves (at least at the time of our fieldwork) navigating outdated legislation (RIPA), with opinions varying across police actors in terms of how it should be interpreted, and the potential risk that evidence will be subject to legal challenge. Furthermore, some police indicated that it was impossible to adhere to the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act Citation1996 when reviewing mobile phone data for the purposes of disclosure and we observed resistance to complying with this legislation and the spirit of disclosure. Lastly, police perceived that they would be hindered by new legislation. To elaborate, while the Investigatory Powers Act Citation2016 (which was implemented after the end of our fieldwork) has begun to address increasing public concerns about police access to mobile phone data, police feared that any restrictions to accessing call data would impede their investigations. Interestingly, some police also expressed that they were being hindered in their efforts to access handsets, and that innovation was being stifled, whilst they worked towards accreditation for digital forensic processes (now legislated under the Forensic Science Regulator Act Citation2021).

Our findings reveal that some of the practices being adopted by police to process data from mobile handsets are problematic and undermine the reliability of evidence. Responsibility for conducting preliminary examinations of handsets sometimes falls to roles on the ‘forensic-periphery’ (Horsman Citation2023, p. 116), such as frontline police officers or non-digital forensic practitioners, some of whom have received little relevant training (Collie Citation2018). This practice, which may lead to crucial data being missed, seems particularly risky in homicide investigations, given the grave implications of error. Furthermore, some practitioners have used unvalidated techniques to extract data where routine methods have failed. Until digital forensic processes are accredited, evidence from the police is vulnerable to exclusion at court on the grounds that it is not demonstrably reliable (Edmond Citation2010). Finally, police are compelled to engage in sifting and screening processes that are not necessarily robust. Subjectivity infuses both the acquisition and processing of mobile phone data. A series of decisions are made, based on investigators’ instincts, suspicions, and early impressions about which handsets to prioritise for examination, and what data to interrogate and how. These social processes between multiple actors, some of which happen in the earliest moments of investigations, shape the construction of mobile phone evidence.

A number of implications, for defendants and their lawyers, arise from our findings. In having to decide which handsets to examine and what data to interrogate, it is inevitable that some data are overlooked by police. Clearly some of the data that are never interrogated may be crucial to implicating or exonerating suspects in homicide cases. This shortfall is further exacerbated by a culture of resistance to (full) disclosure to defence lawyers and a view, expressed by some police and prosecution actors, that disclosure is an administrative burden, rather than a cornerstone of criminal justice. That defence lawyers are not receiving full disclosure or are receiving it at the eleventh hour has obvious implications for criminal justice. Data that might eliminate a suspect or present a different narrative of how events unfolded, may not materialise.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated how mobile phone evidence is constructed by multiple police and prosecution actors and that only some of the potential evidential value of mobile phones is ever realised and/or shared with defence teams. These findings contribute to a small number of studies, in the UK and further afield, that have explored the social construction of digital evidence (e.g. Brookman and Jones Citation2022, Sunde Citation2022), and advance our understanding of both the limitations of digital evidence (Casey Citation2019a), and how police manage digital evidence (Wilson-Kovacs and Wilcox, Citation2023). Furthermore, the findings highlight some of the ways that police practice has evolved at a particular moment in time when legislation has failed to keep pace with advancing technology (see also ICO Citation2020) and various digital evidence practices have not been accredited.

Homicide is a grave offence that attracts significant investigative effort, expertise, and resource (Brookman Citation2022). Homicide investigations are often considered the ‘gold standard’ of police work. Yet, as we have illustrated, the practices adopted to interrogate mobile phone data are fraught with complexity and challenge, compromising the reliability of mobile phone evidence and jeopardising justice for defendants. Several of our participants felt that these challenges and risks are likely to be exacerbated as technology advances and the ‘internet of things’ expands. For example, one SIO (Operation C04) commented, ‘if you consider how we're going to move forward in the next 10 or 20 years, it is frightening … because if you think about the interconnectivity of life now, in 20 years’ time it will be unrecognisable again’. The mobile phone, as a gateway into people’s behaviours, beliefs, thoughts, and activities is likely to become a greater investigative resource for police in the future. It is, therefore, important that the processes used to acquire and interrogate these handsets are demonstrably robust and ethical and that their use by police enhances, rather than jeopardises, criminal justice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and very helpful comments. This paper is based upon research that was funded by a Leverhulme Trust Grant. The authors wish to thank the Trust for the opportunity to undertake this research. The authors extend their gratitude to all those who took part in the research including detectives, police staff, forensic scientists, crime scene managers and coordinators, prosecutors, judges, and other specialists who kindly gave up their time. We are also grateful to Shane Powell, for his initial analysis of some of the data included in this paper, and to an Intelligence Analyst (to remain anonymous) and Associate Professor Dana Wilson-Kovacs for their insights on an earlier draft of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Forensic Science Regulator (Citation2023, p. 26) reported that barely half of organisations providing digital forensic services had achieved the appropriate accreditation five years’ on from the deadline of October 2017.

2 RIPA regulates the interception of communications, the acquisition and disclosure of communications data, the carrying out of surveillance, and the use of covert human intelligence sources.

3 The IMEI number enables police to identify the service provider and other relevant information.

4 This contrasts with Wilson-Kovacs and Wilcox (Citation2023), who found in their study of 35 police forces in England and Wales that digital forensic units prioritised cases involving indecent images of children.

5 When an accused has reasonable cause to believe that there is prosecution material which is required to be disclosed to him/her and has not been, s/he may apply to the court under section 8 for an order requiring the prosecutor to disclose it to him/her (Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act Citation1996).

References

- Berkeley Square Solicitors. n.d. Liam Allen – what happens when the justice system fails [online]. Available from: www.bsblaw.co.uk/blog/y1ki1cx5jzxoaiwp48kegwc04ukcct [Accessed 2 Oct 2023].

- Braun, V., and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- British Society of Criminology. 2015. British Society of Criminology statement of ethics [online]. Available from: https://www.britsoccrim.org/documents/BSCEthics2015.pdf [Accessed 29 Oct 2015].

- Brookman, F., et al., 2020. Dead reckoning: Unravelling how “homicide” cases travel from crime scene to court using qualitative research methods. Homicide studies, 24 (3), 283–306. doi: 10.1177/1088767920907374

- Brookman, F., et al., 2022. Crafting credible homicide narratives: forensic technoscience in contemporary criminal investigations. Deviant behavior, 43 (3), 340–366. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2020.1837692

- Brookman, F., 2022. Understanding homicide. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Brookman, F., and Jones, H., 2022. Capturing killers: the construction of CCTV evidence during homicide investigations. Policing and society, 32 (2), 125–144. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2021.1879075

- Brookman, F., and Jones, H., 2024. Doing fieldwork on homicide investigation. In: K.F. Parker, and A.M. Mancik, eds. Taking stock of homicide: Trends, emerging themes, and the challenges. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 114–132.

- Casey, E., 2019a. The chequered past and risky future of digital forensics. Australian journal of forensic sciences, 51 (6), 649–664. doi: 10.1080/00450618.2018.1554090

- Casey, E., 2019b. Trust in digital evidence. Forensic science international: digital investigation, 31, 1–2.

- Casey, E., and Turnbull, B. 2011. Digital evidence on mobile devices [online]. Available from: https://booksite.elsevier.com/9780123742681/Chapter_20_Final.pdf [Accessed 28 Jan 2022].

- Collie, J., 2018. Digital forensic evidence – flaws in the criminal justice system. Forensic science international, 289, 154–155. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.05.014

- Corbin, J., and Strauss, A., 2008. Basics of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Costa, S., and Santos, F., 2019. The social life of forensic evidence and the epistemic sub-cultures in an inquisitorial justice system: analysis of Saltão case. Science & justice, 59, 471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2019.06.003

- Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act. 1996.

- Crown Prosecution Service. 2022. Disclosure [online]. Available from: https://www.cps.gov.uk/about-cps/disclosure#:~:text=Disclosure%20is%20providing%20the%20defence,is%20done%20properly%2C%20and%20promptly [Accessed 10 Oct 2023].

- Edmond, G., 2010. Suspect sciences? Evidentiary problems with emerging technologies. International journal of digital crime and forensics, 2 (1), 40–72. doi: 10.4018/jdcf.2010010104

- Forensic Analytics. 2020. Briefing paper. GPRS billing: using CDR data evidentially [online]. Available from: https://www.forensicanalytics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/0058-BRF_Briefing_Paper-GPRS_Billing_v3.1.pdf [Accessed 31 Jan 2023].

- Forensic Capability Network. 2023. UK law enforcement invited to join radio frequency exercise [online]. Available from: https://www.fcn.police.uk/news/2023-10/uk-law-enforcement-invited-join-radio-frequency-exercise [Accessed 26 Oct 2023].

- Forensic Science Regulator. 2023. Report on the consultation on the statutory Code of Practice required under Section 3 of the Forensic Science Regulator Act 2021 [online]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/63dd03e88fa8f57fc12e2cbf/Code_Consultation_Report_final.pdf [Accessed 18 Mar 2024].

- Forensic Science Regulator Act. 2021.Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/14/contents

- Gibbs Van Brunschot, E., et al., 2022. Poisoned chalice? The challenges of forensic science and technology for homicide investigations. Police practice and research, 24 (4), 475–492. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2022.2132250

- Gogolin, G., 2021. Digital forensics explained. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Helm, R., 2022. Wrongful conviction in England and Wales: an assessment of successful appeals and key contributors. The wrongful conviction law review, 3 (3), 196–217. doi: 10.29173/wclawr79

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue. 2022. An inspection into how well the police and other agencies use digital forensics in their investigations [online]. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/publication-html/how-well-the-police-and-other-agencies-use-digital-forensics-in-their-investigations/ [Accessed 2 Dec 2022].

- Hiley, C. 2023. UK mobile phone statistics, 2023 [online]. Available from: https://www.uswitch.com/mobiles/studies/mobile-statistics/ [Accessed 3 Oct 2023].

- Horsman, G., 2018. I couldn’t find it your honour, it mustn’t be there!” – tool errors, tool limitations and user error in digital forensics. Science & justice, 58 (6), 433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2018.04.001

- Horsman, G., 2023. Digital evidence strategies for digital forensic science examinations. Science & justice, 63 (1), 116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2022.11.004

- House of Commons Justice Committee. 2018. Disclosure of evidence in criminal cases [online]. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmjust/859/859.pdf [Accessed 10 Oct 2023].

- Hoy, J., 2015. Forensic radio survey techniques for cell site analysis. Chichester: Wiley & Sons.

- Information Commissioner’s Office. 2020. Mobile phone data extraction by police forces in England and Wales. Investigation report [online]. Available from: https://ico.org.uk/media/about-the-ico/documents/2617838/ico-report-on-mpe-in-england-and-wales-v1_1.pdf [Accessed 28 Jan 2022].

- Innes, M., Brookman, F., and Jones, H., 2021. Mosaicking: cross construction, sense-making and methods of police investigation. Policing: an international journal, 44 (4), 708–721. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-02-2021-0028

- Investigatory Powers Act. 2016. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2016/25/contents

- Jasanoff, S., 2006. Just evidence: the limits of science in the legal process. Journal of law, medicine & ethics, 34 (2), 328–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2006.00038.x

- Julian, R., Howes, L., and White, R., 2022. Critical forensic studies. London: Routledge.

- Julian, R., Kelty, S., and Robertson, J., 2012. Get it right the first time: critical issues at the crime scene. Current issues in criminal justice, 24 (1), 25–37. doi: 10.1080/10345329.2012.12035942

- Kruse, C., 2016. The social life of forensic evidence. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Lentz, L.W., and Sunde, N., 2021. The use of historical call data records as evidence in the criminal justice system – lessons learned from the Danish telecom scandal. Digital evidence and electronic signature law review, 18, 1–17.

- Lynch, M., et al., 2008. Truth machine: the contentious history of DNA fingerprinting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- McCartney, C., 2018. Commentary: disclosure in the criminal justice system. Journal of forensic and legal medicine, 58, 72–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2018.04.015

- Metropolitan Police Service and Crown Prosecution Service. 2018. A joint review of the disclosure process in the case of R v Allan: findings and recommendations for the Metropolitan Police Service and CPS London [online]. Available from: https://www.cps.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/publications/joint-review-disclosure-Allan.pdf [Accessed 22 Nov 2021].

- National Police Chiefs’ Council. 2020. Digital forensic science strategy [online]. Available from: https://www.npcc.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/publications/publications-log/2020/national-digital-forensic-science-strategy.pdf [Accessed 27 Sep 2023].

- National Police Chiefs’ Council. 2021. Major crime investigation manual [online]. Available from: https://library.college.police.uk/docs/NPCC/Major-Crime-Investigation-Manual-Nov-2021.pdf [Accessed 2 Dec 2021].

- Page, H., et al., 2019. A review of quality procedures in the UK forensic sciences: what can the field of digital forensics learn? Science & justice, 59 (1), 83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2018.09.006

- Ramirez, F., 2022. The digital divide in the US criminal justice system. New media & society, 24 (2), 514–529. doi: 10.1177/14614448211063190

- Reedy, P., 2020. Interpol review of digital evidence 2016–2019. Forensic science international: synergy, 2, 489–520.

- Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act. 2000. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/23/contents

- Reiber, L., 2019. Mobile forensic investigations. A guide to evidence collection, analysis, and presentation. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Richardson, V., et al. 2022. Using appeal judgement transcripts to assess changes in the presence of digital evidence in police investigations [online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-evidence-in-appeal-judgement-transcripts/using-appeal-judgement-transcripts-to-assess-changes-in-the-presence-of-digital-evidence-in-police-investigations [Accessed 29 Nov 2022].

- Salet, R., 2017. Framing in criminal investigation: How police officers (re)construct a crime. The police journal: theory, practice and principles, 90 (2), 128–142. doi: 10.1177/0032258X16672470

- Smith, T., 2018. The “near miss” of Liam Allan: critical problems in police disclosure, investigation culture, and the resourcing of criminal justice. Criminal law review, 9, 711–732.

- Sommer, P., 2018. Accrediting digital forensics: what are the choices? Digital investigation, 25, 116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.diin.2018.04.004

- Sunde, N., 2022. Unpacking the evidence elasticity of digital traces. Cogent social sciences, 8 (1), 2103946. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2022.2103946

- Tart, M., et al., 2012. Historic cell site analysis – overview of principles and survey methodologies. Digital investigation, 8 (3-4), 185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.diin.2011.10.002

- Tart, M., et al., 2019. Cell site analysis: roles and interpretation. Science & Justice, 59 (5), 558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2019.06.005

- Van Zandwijk, J.P., and Boztas, A., 2021. The phone reveals your motion: digital traces of walking, driving and other movements on iPhones. Forensic science international: digital investigation, 37, 301170.

- Vincze, E.A., 2016. Challenges in digital forensics. Police practice and research: an international journal, 17 (2), 183–194. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2015.1128163

- Wilson-Kovacs, D., 2019. Effective resource management in digital forensics. An exploratory analysis of triage practices in four English constabularies. Policing: an international journal, 43 (1), 77–90. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-07-2019-0126

- Wilson-Kovacs, D., Jones, H., and Brookman, F., 2024. The use of digital evidence in homicide investigations. In: C. Allsop, and S Pike, eds. The international handbook of homicide investigations. Abingdon: Routledge, 103–117.

- Wilson-Kovacs, D., and Wilcox, J., 2023. Managing police demand for digital forensics through risk assessment and prioritization in England and Wales. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 17, paac106. doi: 10.1093/police/paac106

- Wilson-Kovacs, D., and Wyatt, D., 2023. The long journey of resistance toward acceptance: understanding digital forensic accreditation in England and Wales from a social science perspective. Wires forensic science, 6 (1), e1501. doi: 10.1002/wfs2.1501