ABSTRACT

This study examines the relationship between food safety risk perception (FSRP) and social similarity, utilizing eye-tracking to uncover how consumers process information on food labels. Central to our inquiry is that perceived similarity influences how individuals assess and react to food safety risks. Our research posits that individuals who see a high degree of similarity with others in their social circles are more attentive to food safety risks. We conducted two food label experiments, one focusing on safety labels and the other on nutritional information. Findings indicate that heightened perceptions of social similarity (prototype perception and social distance) enhance the impact of food labels (safety labels and nutritional information) on food safety risk assessments (decision-making process and product choice), manifesting in increased visual attention to these labels. This revelation underscores the significance of social factors in shaping food safety behaviors and offers a new perspective for designing more effective food safety communication. Our work contributes to the academic discourse on food safety and social psychology and provides practical insights for public health messaging strategies.

Introduction

Food safety is a crucial component in consumption decisions, which is achieved when people have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences, ensuring a healthy and active life (Gallo et al., Citation2020; Godfray et al., Citation2010; Nardi et al., Citation2020). In this context, food safety, which ensures that food is free from physical, chemical, or biological contaminants, emerges as a pivotal issue in academic research (Manning & Soon, Citation2016; Marucheck et al., Citation2011). Significant incidents, such as disease outbreaks in Europe (Bocker & Hanf, Citation2000), the contamination of pet food in Europe and North America (Roth et al., Citation2008), and the melamine contamination of infant formula in China (Yang et al., Citation2009), have captured the attention of both managers and researchers. These events have spurred many studies and managerial actions to mitigate these risks (Auler et al., Citation2017). The impact of unsafe food is staggering, causing over 200 diseases and sickening approximately 600 million people annually, with 420,000 fatalities (World Health Organization, Citation2019). Unsurprisingly, food safety is one of the foremost concerns among consumers in our global society (Brom & Gremmen, Citation2000).

Understanding food safety risk perception (FSRP), an individual’s belief-based judgment regarding the health risks posed by food, is pivotal in addressing consumer concerns regarding food safety, as heightened FSRP correlates with increased sensitivity to food risk and a reduced likelihood of purchasing (Nardi et al., Citation2020; Roth et al., Citation2008; Slovic, Citation1987). Food labeling, which provides essential information about food characteristics and thus aids consumers in making informed food choices, is a critical strategy for mitigating food safety risks (Hall & Osses, Citation2013). However, the effectiveness of food labeling in transmitting food safety information to consumers has shown mixed results. While some studies indicate that consumers often overlook label information (Moreira et al., Citation2021), others suggest labels significantly influence consumer choices (Allan et al., Citation2018; Caputo, Citation2020). This ambiguity in the role of food labeling in influencing FSRP forms the basis of our investigation, which endeavors to elucidate understanding of FSRP through the lens of consumer psychology, focusing on visual attention and social similarity.

Our first research objective is to examine the influence of FSRP on visual attention toward food labels, addressing the research question: How does the level of FSRP influence consumer visual attention toward food labels? We hypothesize that higher FSRP levels intensify consumers’ visual engagement with food labels as they seek information to guide their decisions. In this context, visual attention implies the consumer’s focused examination of a product’s labeling during the purchasing process. Our second research objective explores the moderating role of social similarity in the interplay between FSRP and visual attention, answering the research question: To what extent does perceived social similarity moderate the relationship between FSRP and visual attention to food labels? Social similarity relates to how individuals process and interpret the actions of others they perceive as similar to themselves (Kenny & West, Citation2010; Liviatan et al., Citation2008; Montoya et al., Citation2008). This study extends the concept of social similarity to consumer behavior in food purchasing, exploring whether a perceived similarity with others amplifies visual attention to food labels among consumers with heightened FSRP. A key consideration is the extent to which prototype perception and social distance impact risk perception and behavior, especially in the context of food-related decisions influenced by the experiences of others (Elliot & Friedman, Citation2017; Gerrard et al., Citation1999; Siegrist & Hartmann, Citation2020).

We conducted two eye-tracking experiments to empirically investigate the relationships between FSRP, social similarity, and visual attention to food labels. The first experiment simulated a supermarket environment with food product labels, while the second mimicked a restaurant setting, focusing on nutritional information. FSRP was operationalized through a priming technique using short videos depicting various scenarios in the food supply chain, including food contamination incidents. Participants were categorized into low, medium, and high FSRP groups based on their responses to these videos. Social similarity was operationalized through concepts of prototype perception and social distance (Liberman & Trope, Citation2014). Prototype perception refers to individuals’ mental representations of a typical actor engaging in a specific behavior, such as purchasing safe food products, influencing how closely an individual identifies with the represented behavior. Social distance relates to the perceived closeness or remoteness one feels toward others engaging in similar actions.

Our findings indicate a significant relationship between FSRP and increased visual attention to food labels, with social similarity amplifying this effect. More specifically, we observe that prototype perception and social distance intensify the impact of FSRP on visual attention to food labels. These results, aligning with our hypotheses, suggest that individuals with higher perceived risk and similarity will likely alter their decision-making processes to mitigate risks associated with contaminated food. This enhances our understanding of food safety behaviors by demonstrating that FSRP is a key determinant of how consumers engage with food labeling and that social similarity plays a pivotal role in this process. More importantly, these insights offer actionable strategies for public health messaging and policymaking, illuminating how psychological factors interact with information presentation to influence consumer behavior. Our study corroborates and extends previous studies by integrating experimental data with perceptual measures, offering a more comprehensive understanding of these dynamics.

This research builds on four streams of literature, i.e., food safety (Grunert & Wills, Citation2007; Lobb et al., Citation2007), risk perception (Slovic, Citation1987), visual attention (Pieters & Wedel, Citation2004), and social similarity (Gibbons & Gerrard, Citation1995). Specifically, we contribute to the literature by (1) establishing a theoretical link between FSRP and visual attention and (2) showing the role of social similarity (prototype perception and social distance) as a moderator. In the same sense, our findings can be used by managers to (1) suggest communication actions in food supply chains (especially traceability and certification), which could promote a collective improvement of the safety environment and (2) provide subsidiary strategies to make the consumer a safety driver (through actions such as non-consumption or safe choices), a determinant factor for the improvement of the institutional environment and consequent decrease of food insecurity events, reducing foodborne diseases and losses from these situations.

The rest of this article is as follows: We begin with a theoretical background covering food labeling, FSRP, visual attention, prototype perception, and social distance – the latter two being core components of social similarity. This is followed by a detailed description of our experimental methods. We designed two studies to test our hypotheses. The first study tests only the direct relationship between FSRP and visual attention to food labels (H1) in food scenarios that contain different perceptions of food risk: tea (low), honey (medium), and milk (high). The second study differs from the first because it tests the moderating effects (prototype perception: H2; social distance: H3) using menus with nutritional information (three main dishes: chicken, fish, and meat; three desserts: fruit salad, chocolate mousse, and chocolate cake) and manipulations of scenarios of absence and presence of food risk. The final section presents our results and discusses these findings in the broader context of food safety research, emphasizing their practical implications for enhancing consumer awareness and safety.

Theoretical background

Food labeling

Food labeling, an essential facet of product packaging, is a crucial communication channel, offering consumers information about food characteristics, including safety and nutritional content. The effectiveness and regulatory aspects of food labeling have been subjects of extensive research (Hall & Osses, Citation2013; Roosen, Citation2003; Tanemura & Hamadate, Citation2022). Labels are mandated to display specific information, but the volume and diversity of this information can sometimes overwhelm consumers.

Studies examining consumer behavior toward food labeling reveal varied preferences and attention levels. Hall and Osses (Citation2013) found that consumer engagement with labels is influenced by several factors, including social demographics, knowledge, trust, and perceived control. Gracia and de Magistris (Citation2016) noted a preference among Spanish consumers for labels indicating food origin and nutritional facts. Similarly, a study in Japan by Tanemura and Hamadate (Citation2022) highlighted consumer demand for comprehensive health benefit information on labels. Contrasting these findings, Moreira et al. (Citation2021) reported that a significant portion of their survey participants struggled to comprehend food labels, with only 34% finding the information useful. These studies collectively suggest that while labels are intended to inform, they can also lead to confusion and misinterpretation.

A critical limitation of many food labeling studies is their reliance on survey data. While surveys are valuable for capturing perceptions and attitudes within structured frameworks, they fail to replicate real-world conditions and capture actual behavior. The accuracy of survey responses is often compromised by memory recall limitations and social desirability bias, where respondents may answer in a manner they believe is expected by others (Krumpal, Citation2013). This gap underscores the need for alternative research methodologies, such as experimental approaches (Lim, Citation2015, Citation2021; Lim et al., Citation2019, Citation2022), which can provide more direct insights into consumer behavior and complement the existing literature on food safety through labeling.

Food safety risk perception (FSRP) and visual attention

FSRP involves an individual’s subjective assessment of the likelihood that a particular food or situation poses health risks (Nardi et al., Citation2020; Roth et al., Citation2008; Slovic, Citation1987). This perception is shaped by personal beliefs and influenced by cultural, institutional, psychological, and social factors (Nardi et al., Citation2020; Slovic, Citation1987). Understanding the interplay between these beliefs and perceived dietary risks is crucial in consumer research.

Visual attention, a key focus in consumer research, has been acknowledged as a significant predictor of consumer behavior and choices (Chandon et al., Citation2009; Pieters et al., Citation2010). Research in this area has explored various factors impacting visual attention, including bottom-up factors like visual complexity (Pieters et al., Citation2010), top-down factors such as consumer motivations (Babin et al., Citation1994), and knowledge (Lindström et al., Citation2016). Notably, health consciousness has been recognized as a top-down factor that positively influences visual attention in food-related contexts (Ran et al., Citation2017).

The dynamic between risk perception and personal beliefs has been a subject of interest across disciplines, including vision science, neuroscience, and social psychology (Jeon et al., Citation2021; Rihn et al., Citation2019; Samant & Seo, Citation2016). These interdisciplinary studies aim to decipher the interaction mechanisms between perceived risk and beliefs, offering vital insights into decision-making (Leon et al., Citation2020; Spence et al., Citation2016).

Behavioral economics has proposed that visual attention can align consumer choices with personal and societal interests (Jeon et al., Citation2021; Leon et al., Citation2020; Rihn et al., Citation2019). Initial studies suggest that focusing on health-related claims or nutrition labels can influence perceived product healthiness and subsequent purchasing decisions (van Herpen et al., Citation2012). However, real-life supermarket studies indicate a generally low motivation among consumers to seek nutritional information (Grunert & Wills, Citation2007), revealing a gap in applying these findings to food safety.

Nevertheless, insights from behavioral economics have increasingly been used to guide consumer choices toward healthier and more sustainable options (Lourenco et al., Citation2016). The choice architecture and recognition of decision-making heuristics are key in nudging consumers toward choices that enhance their well-being. Noteworthily, visual attention to food safety emerges as a significant factor, potentially influencing food label usage and risk perception (Hall & Osses, Citation2013; Leon et al., Citation2020; Rihn et al., Citation2019; Samant & Seo, Citation2016).

The present study builds on these findings by examining how visual stimuli (e.g., safety labels) and cognitive factors (e.g., FSRP) influence personal beliefs. While the direct effects of risk perception on consumer choices and visual attention to safety labels or nutritional information have been less explored, it is hypothesized that higher FSRP will increase visual attention, particularly in contexts with pronounced institutional risk labels (De Jonge et al., Citation2010; Wongprawmas et al., Citation2015). Mrkva et al. (Citation2021) suggest that perceived severity risks can increase attention by generating fear in individuals. Perceiving something risky increases attention levels, generating more mental representations (Carrasco, Citation2006). When an individual perceives something risky about a focal object, the direction of attention levels increases around this object (Mrkva et al., Citation2021).

Nutritional labels on foods tend to inform consumers about different possibilities of problems, activating risk perception (Adasme-Berríos et al., Citation2020). Foods that contain defects such as bruising, splitting, and crushing attract consumers’ visual attention (Jaeger et al., Citation2018). Castagna et al. (Citation2021) used an eye-tracking metric called fixation duration to proxy for vegetable risk perceptions in a study. The results of their experiment demonstrate that the perception of risk with food generated a longer fixation duration, representing greater cognitive processing through difficulty in assimilating information. The perception of risk motivates the individual to intensify the search for information by increasing visual attention (Süssenbach et al., Citation2013). Another experimental psychology study conducted with packaging demonstrated that consumer risk perception positively impacts visual attention (Sun et al., Citation2021). Considering that visualizing a food can be a stimulus that presents perceived severity risk, it is suggested that FSRP can increase consumers’ levels of visual attention (Nardi, Citation2019). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

FSRP positively influences visual attention to food labels.

Perception of social similarity: prototype perception and social distance

Social similarity refers to how individuals process and interpret the actions of others, significantly influencing their judgments about similar or dissimilar actions (Kenny & West, Citation2010; Liviatan et al., Citation2008; Montoya et al., Citation2008). This concept extends beyond self-judgments to encompass how one perceives others’ actions and their similarities or differences. A high level of perceived similarity often denotes a perception of minimal differences among group members (Zellmer-Bruhn et al., Citation2008). Central to understanding social similarity are two concepts: prototype perception and social distance.

Prototype perception involves two key elements: the judgment of similarity (how closely an individual identifies with someone engaging in specific behavior) and the evaluation of the prototype (the positive or negative views held about people who engage in certain behaviors). This approach was developed to understand social influences and behaviors (Gibbons & Gerrard, Citation1995; Thornton et al., Citation2002). Individuals form mental prototypes of those who perform, abstain from, or are subject to behaviors or actions. These prototypes influence conscious and subconscious decision-making, particularly in risky situations (Gibbons & Gerrard, Citation1995). Noteworthily, decision-making processes are affected by two basic systems: an emotional system that is automatic, impulsive, and intuitive and a rational system that is logical and deliberative (Liberman & Trope, Citation2014; Shafir & LeBoeuf, Citation2002). These systems are particularly relevant in food choice contexts, where decisions can fluctuate between rational, deliberate choices and automatic, intuitive actions (Thornton et al., Citation2002).

Consumers tend to pay more attention to objects or people like them (Bichot & Schall, Citation1999; Huang et al., Citation2021; Sato et al., Citation2003). Thus, social knowledge about others tends to impact attention more (Dalmaso et al., Citation2021). The hypothesis argues that prototype perception influences the relationship between FSRP and visual attention. This argument is based on the Gestalt Laws of Grouping (Wertheimer, Citation1938). According to Gestalt principles, our visual processing is associated with graphic representations, as our attention is influenced by the grouping of objects (Huang et al., Citation2021). In this grouping, similarity plays an important role in visual attention (Breugelmans et al., Citation2007; Duncan & Humphreys, Citation1989). Similar products or people tend to generate more attention than dissimilar ones (Huang et al., Citation2021). Neural activation is greater when objects and people are highly like the target stimulus (Bichot & Schall, Citation1999; Sato et al., Citation2003). Kawakami et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated that greater perceived similarity between participants and targets predicted more attention in an eye-tracking study. Objects or people placed closer to a focal object or person will receive more attention than those placed further away (Bichot & Schall, Citation1999; Huang et al., Citation2021). In the context of food choices, prototype perception could play a pivotal role. For instance, if an individual positively evaluates a patient with foodborne disease, perceiving high similarity may amplify the impact of food safety risk perception on their visual attention. Thus, feeling close to or like someone affected by a foodborne illness may increase an individual’s tendency to seek food safety information. Given these considerations, we hypothesize the following:

H2.

Prototype perception positively moderates the relationship between FSRP and visual attention.

The concept of social distance, integral to understanding social similarity, involves the perceived closeness or remoteness between individuals (Liberman & Trope, Citation2014; Liviatan et al., Citation2008). This perception influences decision-making, as described by the construal level theory, which posits that psychological distance affects how people mentally represent and process information about others or events (Liberman & Trope, Citation2014). Construal level theory proposes that the level of abstraction in our mental representations varies with psychological distance. Higher-level (abstract) processing leads to broader, more generalized perceptions, while lower-level (concrete) processing focuses on specific details (Hamilton & Thompson, Citation2007). In the context of food choices, this theory suggests a variance in focus depending on the perceived distance. Decision-making may be more concrete for personal choices or those concerning close others, emphasizing tangible attributes like nutritional value or safety.

In contrast, choices made for or about distant others (e.g., organizational decisions) tend to be more abstract when considering broader attributes (e.g., the overall benefits or risks associated with a product). This distinction is particularly relevant in the domain of food safety, where studies have shown that food-related risks are perceived differently in domestic (closer) versus organizational (more distant) environments, with a higher incidence of risk-related events in more intimate settings (Narrod et al., Citation2009; Young et al., Citation2017). This might be due to the different levels of mental processing, as more concrete personal or close choices lead to decisions influenced by immediate concerns and emotional reactions, and more abstract for distant others are guided by rational considerations. Regarding food safety, when individuals perceive little similarity with someone affected by a foodborne illness, their choices may be less cautious in purchasing and food handling, leading to higher contamination risks in domestic settings. In contrast, choices made for others, such as organizational buying, are likely more rational and safety-focused.

Given these insights, social distance is posited to moderate the effects of perceived risks on visual attention. Specifically, we propose that closer social distances will result in heightened visual attention to safety aspects in food choices due to more concrete, detailed mental processing. Hence, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H3.

Social distance positively moderates the relationship between FSRP and visual attention to food labels.

Study 1: visual attention to safety labels

The first study aims to investigate the impact of FSRP on visual attention. We employed an experimental design in a controlled laboratory setting to test the first hypothesis: the direct effect of FSRP on visual attention to safety labels (H1). The food products were strategically chosen to represent different levels of food safety risk. The range of food products provides a diverse context to assess the nuances in visual attention driven by perceived food safety risks.

Participants

The experiment was conducted with 63 participants (47.6% male; mean age = 24.37, SD = 6.26). We utilized a Tobii Pro X3–120 eye tracker as used by many other previous studies (Ladeira et al., Citation2023, Citation2024), a screen-based device with a high tracking frequency of 120 Hz, for data collection. The eye tracker, integrated into a 17-inch TFT monitor, operates without visible gadgets or the need for participants to wear additional equipment. This setup ensures a naturalistic environment, allowing participants to interact with the screen as they would in a real-life scenario, thereby enhancing the validity of the data collected.

Procedure and measures

The study procedure began with participants entering the experiment venue at five-minute intervals. Upon arrival, they were seated in front of a monitor equipped with an eye tracker. A calibration process was conducted for each participant to ensure accurate eye tracking. In cases where initial calibration failed, chair and monitor adjustments were made to achieve correct eye recognition.

Participants were first exposed to articles about recent foodborne illnesses. These articles served as primers to influence their FSRP. We utilized the Tobii Studio software to develop the stimuli, with visual attention data captured through fixation counts. The fixation count, indicating the number of times a participant’s gaze fixated on a specific point, was used as a proxy for food safety risk perception. This is based on the principle that fixation count is correlated with pupil dilation, a marker of heightened cognitive processing. Participants in the high FSRP group read an article about foodborne illnesses occurring in their state, while those in the low FSRP group read about similar incidents in the country. The median of the fixation counts was calculated to create a dichotomous variable representing low-risk (below median) and high-risk (above median) perception. Following this, participants were presented with three food products on virtual supermarket shelves, i.e., tea, honey, and milk, using actual food brand images. Visual attention (dependent variable) was quantified through fixation counts within the specified area of interest, namely the safety labels on each product.

We assessed the FSRP (independent variable) for each food item using four statements. The assessed statements were: “The risk of someone being contaminated by consuming this tea/honey/milk is high,” “I can get sick after consuming this tea/honey/milk,” “I can have negative consequences on my health due to consuming this tea/honey/milk,” and “My health may be damaged in the future by consuming this tea/honey/milk” (Danelon & Salay, Citation2012). All measures used a seven-point Likert scale (1-strongly disagree to agree 7-strongly).

To account for other (control) variables that might influence visual attention, we administered the Fast Five Personality Test (Rammstedt & John, Citation2007) and collected socio-demographic data (gender, age, income, presence of children, or elderly in the household).

The manipulation check for prototype perception consisted of analyzing participants’ prototype perception. After the manipulation exposition, participants answer 11 items (i.e., sophisticated, confused, immature, intelligent, popular, self-confident, independent, self-centered, careless, unattractive, and cool) on a scale (1 = less, 4 = medium, and 7 = much) about its evaluation of the described prototype (Gibbons & Gerrard, Citation1995). Participants responded to statements evaluating their perceived similarity and prototype evaluation concerning a consumer affected by foodborne disease, such as “I resemble someone who gets sick from eating food” or “The food disease patient is sophisticated.” A median calculation created a dummy variable distinguishing between low (0) and high (1) prototype perception.

Results

Control variables

We tested the effects of the Fast Five Personality Test (Rammstedt & John, Citation2007) on visual attention to the three packages. No significant differences were found in the five dimensions (Openness: M_Low = 7.26; SD_Low = 6.43; M_High = 6.13; SD_High = 4.82; F(1,61) = .4502, p = .5781; Conscientiousness: M_Low = 7.02; SD_Low = 6.67; M_High = 6.56; SD_High = 4.81; F(1,61) = 0951, p = . 7573; Agreeableness: M_Low = 6.75; SD_Low = 5.79; M_High = 6.83; SD_High = 5.91; F(1,61) = .0027, p = .9582; Extraversion: M_Low = 7.82; SD_Low = 6.94; M_High = 6.12; SD_High = 4.91; F(1,61) = 1.2991, p = .2581; and Neuroticism: M_Low = 6.77; SD_Low = 5.74; M_High = 6.83; SD_High = 5.98; F(1,61) = .0002, p = .9641). Furthermore, we found no mean differences in the variables gender (M_Male = 6.19; SD_Male = 6.71; M_Female = 7.35; SD_Female = 6.70; F(1,61) = .6211, p = .4336), age (M_Low = 6.45; SD_Low = 4.91; M_High = 7.06; SD_High = 6.01; F(1,61) = .1882, p = .6659), income (M_Low = 6.45; SD_Low = 4.95; M_High = 7.098; SD_High = 6.51; F(1,61) = .1868, p = .677), presence of children (M_ Absence = 6.99; SD_ Absence = 5.92; M_Presence = 5.98; SD_Presence = 5.46; F(1,61) = .2911, p = .2901), or elderly in the household (M_ Absence = 6.69; SD_ Absence = 5.78; M_Presence = 7.65; SD_Presence = 6.47; F(1,61) = .1666, p = .6845).

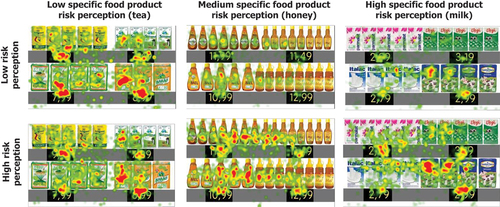

Heat map analysis of three products

Our heat map analysis, which indicates visual attention to the safety labels on the three products, revealed notable differences. There was a significant variation in fixation counts on the safety labels of each product (Milk: M = 3.3175, SD = 2.6763; Honey: M = 2.4202, SD = 2.0566; Tea: M = 2.2487, SD = 2.2753; F(2,438) = 8.4258, p < .01). However when comparing the overall visual attention across all three products, no significant difference was found in average fixation counts (Milk: M = 79.6023, SD = 54.3036; Honey: M = 73.7619, SD = 48.4643; Tea: M = 71.4167, SD = 47.9054; F(2,128) = .07502, p = .473). presents the heat map of visual attention.

Visual attention to safety labels by FSRP

The comparison of visual attention to safety labels between participants with low and high FSRP showed significant differences (t(1) = −3.549, p < .001). Participants with a higher FSRP (M = 2.92, SD = 2.42) exhibited greater visual attention to safety labels, as indicated by higher fixation counts, than those with lower FSRP (M = 2.12, SD = 2.17). Fixation counts determined attentional levels. In the lower FSRP conditions, visual attention to the tea, honey, and milk packaging demonstrated lower values than higher FSRP (tea: M lower FSRP = 1.72, SD lower FSRP = 5.05; M higher FSRP = 2.63, SD higher FSRP = 7.27; t(1) = −3.109, p < .05; honey: M lower FSRP = 2.02, SD lower FSRP = 3.75; M higher FSRP = 2.91, SD higher FSRP = 2.9; t(1) = −2.401, p < .001; milk: M lower FSRP = 2.44, SD lower FSRP = 1.8; M higher FSRP = 3.67, SD higher FSRP = 1.78; t(1) = −3.301, p < .001). These results reflect Süssenbach et al. (Citation2013), demonstrating that risk perception generated a greater number of fixations. In line with other studies, our H1 also demonstrated that greater risk perception generates greater visual attention (Castagna et al., Citation2021; Nardi, Citation2019). This finding supports H1, suggesting that increased FSRP enhances visual attention to safety labels.

Comparison of low versus high FSRP by prototype perception

When comparing low and high prototype perception among participants with low FSRP, no significant difference was observed in visual attention to safety labels (Low prototype: M = 2.01, SD = 2.34; High prototype: M = 2.19, SD = 1.76; t(1) = −.602, p = .2738) ().

Figure 2. FSRP and prototype perception on visual attention to safety labels.

Conversely, a significant difference was found in participants with high FSRP (Low prototype: M = 2.04, SD = 2.07; High prototype: M = 3.09, SD = 2.35; t(1) = −3.569, p < .001). Additionally, participants with high prototype perception exhibited significant differences in visual attention to safety labels (t(1) = −2.891, p < .001) between low FSRP (M = 2.19, SD = 1.76) and high FSRP (M = 3.09, SD = 2.35), whereas those with low prototype perception did not show such differences (Low FSRP: M = 2.01, SD = 2.36; High FSRP: M = 2.04, SD = 2.07; t(1) = −.1349, p = .446).

These results provide evidence of increased fixation counts in participants with high prototype perception compared to those with low prototype perception in conditions of high FSRP. We chose to develop Study 2 to further test H2 and H3.

Study 2: visual attention to nutritional information

The second study aims to examine the influence of FSRP on visual attention to nutritional information. This study specifically investigates the interaction effects of FSRP and visual attention to nutritional information as moderated by prototype perception and social distance. Participants were presented with scenarios involving food choices in a restaurant to simulate a realistic setting. The study employed eye trackers to measure visual attention to nutritional information scenarios.

Participants

The eye-tracking experiment involved 141 consumers (50.35% female; mean age = 32.4 years). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: the absence or presence of food safety risk.

Procedure and measures

The Tobii Pro X3–120 eye-tracking system was used for the experiment, and all procedures were conducted using the Tobii Studio software. The experiment consisted of four stages:

Stage 1: Manipulation of FSRP

Participants were exposed to either the absence or presence of food safety risk scenarios. This manipulation was represented by a binary variable (0 for absence, 1 for presence).

In the presence of a food safety risk scenario, participants read seven headlines that mention food safety risk:

“Majority says food hygiene rating display should be mandatory in England.”

“France hits hardest in multi-country Salmonella egg outbreak.”

“New report shows incidents almost doubled for global food safety network in 2021.”

“Company recalls dried plums because of risk of lead poisoning.”

“Ice cream recalled because of the positive test for Listeria from equipment.”

“Onion outbreak is over, but FDA continues investigation; more than 1,000 sickened.”

“Mushroom poisonings in China responsible for deaths in 2021.”

In the absence of a food safety risk scenario, participants read seven headlines with no mention of food safety risk:

“Companies waging battle on crops as food vs. fuel.”

“Wellness still a healthy trend for food makers.”

“Food groups bank on emerging market growth.”

“Unilever sees food sales growth accelerating.”

“Hormel says natural trumps organic.”

“The appetite for protein bars gives much to chew on.”

“The chefs turning to artificial intelligence.”

Stage 2: Measurement of prototype perception

After the initial exposure to food safety risk scenarios, the study proceeded to the second task involving measuring prototype perception. This was assessed using an 11-item scale based on Gibbons and Gerrard’s (Citation1995) prototype model of risk behavior, which included attributes such as sophistication, confusion, immaturity, intelligence, and popularity.

Stage 3: Manipulation of social distance

The next stage involved the manipulation of social distance between the participants and the food safety scenarios. Participants were informed that they would assist someone in a restaurant to choose a meal from a menu. To create varying levels of social distance, participants were randomly assigned to one of three scenarios: (1) assisting a family member, (2) aiding a coworker, or (3) helping a stranger with their menu choice. This approach was based on the idea that consumer choices and advice vary according to the closeness of their relationship with the other person, aligning with findings that in-groups are often perceived more positively than out-groups (Liberman et al., Citation2007).

Stage 4: Food choice task and visual attention measurement

The final stage involved participants making food choices based on the nutritional information presented to them. They were shown a photograph of a restaurant menu on a computer screen with the Tobii Pro X3–120 eye tracker attached. The menu included images of the dishes and their respective nutritional information. The food options comprised three main dishes (chicken, fish, and meat) and three desserts (fruit salad, chocolate mousse, and chocolate cake). Visual attention to the nutritional information was the dependent variable measured through fixation counts within the areas of interest (AOIs) related to decision-making and product choice.

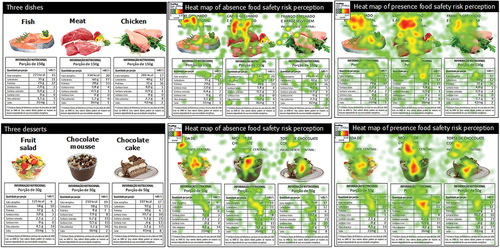

presents a heat map of visual attention, reflecting participants’ engagement with different menu options and their nutritional information.

Results

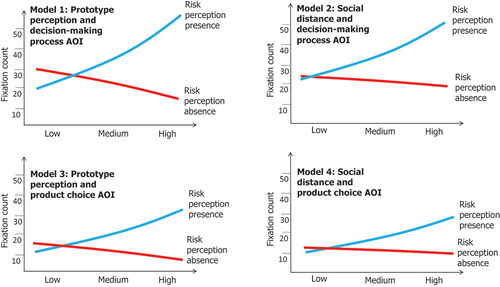

To analyze the interplay between FSRP, prototype perception (H2), and social distance (H3) on visual attention to nutritional information (H1), we employed the bootstrapped moderated model analysis using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 1; 5,000 bootstrapped samples) (Hayes, Citation2017). The dependent variable, visual attention to nutritional information, was evaluated in two distinct aspects and led to four separate models: decision-making process AOI and product choice AOI, each further divided by the moderating effects of prototype perception and social distance. Interaction patterns for these models are detailed in and .

Figure 4. Effect of prototype perception and social distance on the decision-making process and product choice AOI.

Table 1. Conditional effects of the focal predictor at values of the moderator(s).

Effect of prototype perception on decision-making process AOI

The first model assessed the main effects and interaction between prototype perception and FSRP on visual attention to nutritional information in AOI decision-making. The model was significant (F [3,136] = 24.8889, p < .001, R2 = 0.3544). Consistent with H1, FSRP was a significant predictor of visual attention in this AOI (b = 7.9449, SE = 3.791, 95% CI [.4499; 15.4399], p < .001). The influence of FSRP on visual attention varied with prototype perception levels, i.e., it was significant at middle (b = 14.672, SE = 2.207, 95% CI [10.308; 19.036], p < .001) and high (b = 32.691, SE = 3.425, 95% CI [25.918; 39.464], p < .001) but not low (b = −6.351, SE = 3.623, 95% CI [−13.516; .815], p = .082) ( Model 1) levels, thereby supporting H2.

Effect of social distance on the decision-making process AOI

The second model, concentrating on the effect of social distance on visual attention to nutritional information in the decision-making process AOI, was significant (F [3,136] = 25.2059, p < .05, R2 = .3573). Interactions with social distance were significant when social distance was at middle (b = 12.489, SE = 2.403, 95% CI [7.737; 17.386], p < .001) and high (b = 25.641, SE = 4.175, 95% CI [17.241; 33.869], p < .001) but not low (b = .663, SE = 3.345, 95% CI [−7.278; 5.951], p = .843) levels, thereby rendering support to H1 and H3.

Effect of prototype perception on product choice AOI

The third model, focusing on the effect of prototype perception on visual attention to nutritional information in the product choice AOI, was significant (F [3,136] = 30.1555, p < .001, R2 = .3995). Interactions with prototype perception were significant at middle (b = 9.833, SE = 1.488, 95% CI [6.941; 12.826], p < .001) and high (b = 20.306, SE = 2.309, 95% CI [15.739; 24.873], p < .001) but not low (b = −2.443, SE = 2.443, 95% CI [−7.107; 2.556], p = .353) levels, thus lending support to H1 and H2.

Effect of social distance on product choice AOI

The fourth and final model, investigating the effect of social distance on visual attention to nutritional information in the product choice AOI, was significant (F [3,136] = 24.8889, p < .05, R2 = .3544). Interactions with social distance were significant at middle (b = 8.557, SE = 1.569, 95% CI [5.453; 11.661], p < .001) and high (b = 16.808, SE = 2.726, 95% CI [11.416; 22.200], p < .001) but not low (b = .306, SE = 2.184, 95% CI [−4.014; 4.626], p = .888) levels, thus rendering support to H1 and H3.

Discussion

This study was motivated by exploring the relationship between FSRP and visual attention to food labels (safety labels and nutritional information), focusing on the moderating effects of social similarity (prototype perception and social distance). We conducted two eye-tracking experiments in simulated supermarket (Study 1) and restaurant (Study 2) environments to achieve this. Our approach combined insights from visual attention (Pieters & Wedel, Citation2004) and social similarity (Liviatan et al., Citation2008; Montoya et al., Citation2008) within the context of food choice behavior.

A pivotal finding of our research is the influence of FSRP on consumer engagement with food labels. We observed that higher levels of FSRP correspond with increased visual attention to safety labels and nutritional information. Previous studies (Hall & Osses, Citation2013; Moreira et al., Citation2021) analyzed visual attention on the packaging but did not state that risk can alter this. This aligns with the hypothesis that consumers perceiving greater food safety risks are more vigilant in their information search, which adds another dimension to the existing literature on safety and nutritional labeling practices (Hall & Osses, Citation2013; Moreira et al., Citation2021). Our study demonstrates that visual attention to food labels is not just a passive act but a dynamic process influenced by an individual’s risk assessment. Although previous studies have warned that risk can increase attention (Carrasco, Citation2006; Mrkva et al., Citation2021), there is no detailed explanation of this cognitive process. Our study provides eye-tracking evidence to demonstrate how attention is increased.

Another important finding is that prototype perception and social distance – exemplifying social similarity – play crucial roles in this dynamic. Specifically, prototype perception was found to positively moderate the impact of FSRP on visual attention to food labels for safety and nutritional information. This implies that individuals who conceptualize a consumer model or ideal type concerning safe food consumption are likely to be more influenced by their FSRP in directing attention to food labels. This suggests consumers’ mental models about food safety are key in their information-processing and decision-making behaviors. Similarly, our results show that social distance acts as a significant moderator. We found that the closer the social relationship (as perceived by the consumer), the greater the impact of FSRP on visual attention to food labels. This aligns with the social similarity approach, suggesting that the level of perceived similarity, as determined by social distance, can influence attention to food safety information.

This exploration not only brings to light the notable ways consumers navigate food safety but also underscores the influence of social similarity, particularly through the lenses of prototype perception and social distance. Such insights significantly broaden the scope of existing literature on the social dimensions of decision-making (Cialdini & Trost, Citation1998), bridging cognitive processes with social consumer interactions. This synthesis enriches our understanding of how consumers interact with food labels in diverse social contexts and serves as a foundation for future explorations into the relationship between individual cognition and the social environment with food safety.

The significant moderating effects of prototype perception and social distance bring to the forefront the often-overlooked role of social psychological factors in guiding consumer attention and decision-making. This alignment with and extension of established theories on social influence in decision-making processes (Cialdini & Trost, Citation1998) provides a fresh lens through which we can view the complex factors that drive consumer choices regarding food safety. This is a compelling illustration of how deeply embedded cognitive and social factors shape consumer interactions, particularly in areas as critical as everyday food choice and safety. This finer-grained understanding enriches existing literature and charts new territories for exploring how consumers’ social proximity and perceived similarities influence their engagement with food safety information.

The visual impacts of food labels also emerged as pivotal areas of interest in our study. This discussion opens new theoretical pathways for examining how food labels influence consumer perceptions and behaviors, enabling a deeper exploration into the semiotics of food labeling – the study of how imagery communicates and shapes consumer understanding and decision-making. Previous studies have attempted to understand the nuances of food labeling and its direct effects on visual attention (Hall & Osses, Citation2013; Moreira et al., Citation2021). This multidisciplinary inquiry, spanning consumer behavior, marketing, and semiotics, promises to unravel the complex ways visual cues on labels navigate consumer perceptions and choices. Exploring the symbolic signals of food labels enables us to gain insights into how consumers interpret and respond to various information. This exploration is particularly pertinent in an era where food quality and safety certifications increasingly influence and guide consumer choices. Integrating semiotic analysis with empirical consumer research methods could yield a deeper understanding of how labels impact risk perception and choice behavior in food markets. This aspect of our research underscores the need for a comprehensive approach to food safety risk communication, challenging researchers, marketers, and policymakers to consider food labels’ content, form, and visual appeal as they recognize their potential to inform, influence, and transform consumer behavior considering food safety.

These findings have important implications for food safety communication strategies. They suggest promoting food safety through labels could be more effective if they resonate with consumers’ social contexts and psychological models. For instance, designing labels that reflect or evoke the image of a “safe food consumer” that individuals can relate to might enhance the label’s effectiveness. This also implies that food safety campaigns should consider incorporating elements that people find socially and psychologically relatable, potentially leveraging community figures or everyday scenarios that consumers find familiar.

Moreover, by employing an experimental design with eye-tracking technology, our study addresses some of the limitations associated with survey-based research, such as recall bias and the inability to capture real-time cognitive processing. This approach allows for more direct observation of how consumers interact with food labels and provides empirical evidence that enhances our understanding of the mechanisms driving visual attention in the context of safety labels and nutritional information. Therefore, our study not only corroborates previous findings on the significance of FSRP in consumer behavior but also extends the discourse by highlighting the critical role of social similarity factors like prototype perception and social distance. When taken collectively, these insights contribute to a more holistic understanding of how consumers process food safety information and offer valuable insights for designing more effective food safety communication strategies.

Conclusion

A critical outcome of our study is clarifying how perceived risk impacts visual attention, especially when interplayed with high levels of prototype perception or social distance. This highlights the importance of considering social contextual variables in understanding consumer behavior toward food safety. Our results suggest that individuals are more likely to engage with food labels when they perceive a higher risk and feel a greater sense of social connectedness or similarity to the behavior depicted. These insights bring socio-psychological dimensions into the broader conversation about food safety, suggesting that efforts by managers and policymakers to enhance food safety communication should not solely focus on providing information. This study crosses the boundaries between cognitive psychology and social behavior by dissecting the complex interplay between FSRP and visual attention to food labels, revealing several theoretical implications. The findings from our investigation offer an insightful perspective on the interplay between cognitive processes and social dynamics in consumer behavior. Merging the elements from the visual attention theory (Pieters & Wedel, Citation2004) and social similarity concepts (Liviatan et al., Citation2008; Montoya et al., Citation2008), our study illuminates the multifaceted ways in which consumer visual engagement with food labels is shaped, not only by individual risk perceptions but also by the subtle yet powerful forces of social comparisons.

Looking deeper into cognitive psychology, our research casts new light on how consumer perception of food safety risks influences visual attention and information processing. This critical insight exposes the cognitive underpinnings of consumer responses to perceived risks in food consumption. Revealing the variance in visual attention according to levels of FSRP, our study not only explains the mechanisms through which consumers discern and react to potential food safety threats but also underscores the imperative of adopting a more integrated cognitive-social framework in the analysis of consumer behavior. This approach bridges the gap between individual cognitive processing and the broader spectrum of social influences, offering a comprehensive lens through which the complexities of consumer decision-making in food markets can be better understood.

Our multi-experimental study’s innovative use of eye-tracking technology marks significant progress in consumer research methodologies. We used a more direct and empirical approach to understanding consumer behavior by stepping beyond the conventional boundaries of self-reported measures. This shift toward objective, behaviorally anchored techniques such as eye-tracking allows for a more precise and real-time observation of how consumers interact with food labels. This, in turn, addresses inherent limitations in traditional research methods and paves the way for more robust, empirical investigations into consumer-food interactions. This methodological shift to theoretical exploration highlights the critical need for research tools that can capture the complexities and subtleties of consumer behavior as it unfolds, offering a more accurate portrayal of the decision-making process. Furthermore, this advancement underscores the potential for future research to dive deeper into the nuances of consumer engagement with food safety information, inviting exploration into how different label designs, formats, and contexts might influence consumer attention and decision-making.

The insights gained from this study hold significant practical implications for those involved in food safety management and policy-making. Our findings offer strategic pathways for enhancing consumer awareness and engagement in food safety. One critical implication is the potential to strategically leverage information about risky food situations to heighten consumers’ FSRP. Policymakers can elevate consumers’ awareness and vigilance by effectively communicating about food contamination events or other risk scenarios. This, in turn, can lead to increased visual attention to food labels, empowering consumers to make more informed choices. For instance, using real-life events or scenarios in public awareness campaigns can help contextualize risks, making them more relatable and impactful for the average consumer. Leveraging the power of visual stimuli in communication strategies is crucial for managers, particularly in high-risk food sectors. Understanding the relationship between FSRP and visual attention to labels allows for the design of tailored communication strategies. This can involve framing product information to highlight safety aspects or employing visual cues that draw attention to critical label information. Moreover, considering the varying effects across different social distances, our findings underscore the need for a context-dependent approach to food safety communication. Managers can craft more effective food safety campaigns using insights from the study on social similarity and visual attention. These campaigns should endeavor to connect with consumers across different social contexts, leveraging social distance to enhance message efficacy.

While this research provides valuable insights, it also presents limitations that open doors for future explorations. One limitation is the lack of consideration for the impact of prior or subjective knowledge. Consumer knowledge, which can vary significantly among different groups, might influence how individuals perceive and respond to food safety information. Future research could explore this aspect by examining how varying levels of consumer knowledge affect responses to food labels and safety information. This exploration could lead to more targeted and effective communication strategies that consider the diverse knowledge backgrounds of consumers. Another area for further investigation is the influence of the origin and visual presentation of packaging certification symbols. Although our study acknowledged the impact of including safety certification elements, the specific effects of different visual elements – such as color, shape, or luminosity – remain unexplored. Future studies might examine whether variations in these visual aspects influence consumer attention and decision-making more substantially. For instance, questions like how a glowing safety symbol on opaque packaging affects consumer perception or how public versus private certifications differ in impact are fertile grounds for research. Our research also did not incorporate social factors in food choices, such as crowd perception or the presence of companions during shopping. These factors may significantly influence consumer behavior, as shopping decisions often occur in social settings like crowded markets or accompanied by family or friends. Future studies could explore how crowd density affects the attention paid to food safety labels or how the presence of companions might constrain or enhance the consumer’s decision-making process. Such research might yield insights into how social contexts and dynamics shape consumer interactions with food labels, further enriching the understanding of consumer behavior in food markets.

While our research contributes to the literature on FSRP and label use, these identified limitations provide opportunities for future research. Addressing these gaps could enhance our understanding of the multifaceted nature of consumer behavior in the context of food safety, ultimately leading to more effective strategies for promoting informed food choices and public health.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adasme-Berríos, C., Aliaga-Ortega, L., Schnettler, B., Sánchez, M., Pinochet, C., & Lobos, G. (2020). What dimensions of risk perception are associated with avoidance of buying processed foods with warning labels? Nutrients, 12(10), 2987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12102987

- Allan, P. D., Palmer, C., Chan, F., Lyons, R., Nicholson, O., Rose, M., Hales, S., & Baker, M. G. (2018). Food safety labelling of chicken to prevent campylobacteriosis: Consumer expectations and current practices. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 414. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5322-z

- Auler, D. P., Teixeira, R., & Nardi, V. (2017). Food safety as a field in supply chain management studies: A systematic literature review. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 20(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2016.0003

- Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. The Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656. https://doi.org/10.1086/209376

- Bichot, N. P., & Schall, J. D. (1999). Effects of similarity and history on neural mechanisms of visual selection. Nature Neuroscience, 2(6), 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1038/9205

- Bocker, A., & Hanf, C. H. (2000). Confidence lost and - partially - regained: Consumer response to food scares. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 43(4), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-2681(00)00131-1

- Breugelmans, E., Campo, K., & Gijsbrechts, E. (2007). Shelf sequence and proximity effects on online grocery choices. Marketing Letters, 18(1–2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-006-9002-x

- Brom, F. W. A., & Gremmen, B. (2000). Food ethics and consumer concerns. Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics, 12(2), 111–112. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009526327701

- Caputo, V. (2020). Does information on food safety affect consumers’ acceptance of new food technologies? The case of irradiated beef in South Korea under a new labelling system and across different information regimes. The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 64(4), 1003–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8489.12393

- Carrasco, M. (2006). Covert attention increases contrast sensitivity: Psychophysical, neurophysiological and neuroimaging studies. Progress in Brain Research, 154, 33–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(06)54003-8

- Castagna, A. C., Pinto, D. C., Mattila, A., & de Barcellos, M. D. (2021). Beauty-is-good, ugly-is-risky: Food aesthetics bias and construal level. Journal of Business Research, 135, 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.063

- Chandon, P., Hutchinson, J. W., Bradlow, E. T., & Young, S. H. (2009). Does in-store marketing work? Effects of the number and position of shelf facings on brand attention and evaluation at the point of purchase. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.6.1

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T., Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology, Vols. 1 and 2 (4th ed., pp. 151–192). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Dalmaso, M., Castelli, L., Scatturin, P., & Galfano, G. (2021). Can attitude similarity shape social inhibition of return? Visual Cognition, 29(7), 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13506285.2021.1922566

- Danelon, M. S., & Salay, E. (2012). Development of a scale to measure consumer perception of the risks involved in consuming raw vegetable salad in full-service restaurants. Appetite, 59(3), 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.07.013

- De Jonge, J., Van Trijp, H., Renes, R. J., & Frewer, L. J. (2010). Consumer confidence in the safety of food and newspaper coverage of food safety issues: A longitudinal perspective. Risk Analysis, 30(1), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01320.x

- Duncan, J., & Humphreys, G. W. (1989). Visual search and stimulus similarity. Psychological Review, 96(3), 433. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.3.433

- Elliot, A. J., & Friedman, R. (2017). Approach—avoidance: A central characteristic 01 personal goals. In Personal project pursuit goals, action, and human flourishing (pp. 97–118). Psychology Press.

- Gallo, M., Ferrara, L., Calogero, A., Montesano, D., & Naviglio, D. (2020). Relationships between food and diseases: What to know to ensure food safety. Food Research International, 137, 109414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109414

- Gerrard, M., Gibbons, F. X., Zhao, L., Russell, D. W., & Reis-Bergan, M. (1999). The effect of peers’ alcohol consumption on parental influence: A cognitive mediational model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 13(s13), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.32

- Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (1995). Predicting young adults’ health risk behavior. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 69(3), 505–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.3.505

- Godfray, H. C. J., Beddington, J. R., Crute, I. R., Haddad, L., Lawrence, D., Muir, J. F. & Toulmin, C. (2010). Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science, 327(5967), 812–818. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185383

- Gracia, A., & de Magistris, T. (2016). Consumer preferences for food labeling: What ranks first? Food Control, 61, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.09.023

- Grunert, K. G., & Wills, J. M. (2007). A review of European research on consumer response to nutrition information on food labels. Journal of Public Health, 15(5), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-007-0101-9

- Hall, C., & Osses, F. (2013). A review to inform understanding of the use of food safety messages on food labels. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(4), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12010

- Hamilton, R. W., & Thompson, D. V. (2007). Is there a substitute for direct experience? Comparing consumers’ preferences after direct and indirect product experiences. The Journal of Consumer Research, 34(4), 546–555. https://doi.org/10.1086/520073

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

- Huang, B., Juaneda, C., Sénécal, S., & Léger, P. M. (2021). “Now you see me”: The attention-grabbing effect of product similarity and proximity in online shopping. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 54(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.08.004

- Jaeger, S. R., Machín, L., Aschemann-Witzel, J., Antúnez, L., Harker, F. R., & Ares, G. (2018). Buy, eat or discard? A case study with apples to explore fruit quality perception and food waste. Food Quality and Preference, 69, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.05.004

- Jeon, Y., Cho, M. S., & Oh, J. (2021). A study of customer perception of visual information in food stands through eye-tracking. British Food Journal, 123(12), 4436–4450. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2020-1082

- Kawakami, K., Friesen, J. P., Williams, A., Vingilis-Jaremko, L., Sidhu, D. M., Rodriguez-Bailón, R., Cañadas, E., & Hugenberg, K. (2021). Impact of perceived interpersonal similarity on attention to the eyes of same-race and other-race faces. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00336-8

- Kenny, D. A., & West, T. V. (2010). Similarity and agreement in self-and other perception: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(2), 196–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309353414

- Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

- Ladeira, W. J., Lim, W. M., Santini, F. D. O., Rasul, T., Rice, J. L., & Azhar, M. (2024). Fostering conative loyalty in tourism and hospitality loyalty programs: An eye-tracking experiment of reward timing, fairness perception, and visual attention. Tourism Recreation Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2024.2369487

- Ladeira, W. J., Rasul, T., Santini, F. D. O., & Perin, M. G. (2023). The bright side of disorganization: When surprise generates low-price signals. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 73, 103340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103340

- Leon, F. A. D., Spers, E. E., & de Lima, L. M. (2020). Self-esteem and visual attention in relation to congruent and non-congruent images: A study of the choice of organic and transgenic products using eye tracking. Food Quality and Preference, 84, 103938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103938

- Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2014). Traversing psychological distance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(7), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.03.001

- Liberman, N., Trope, Y., McCrea, S. M., & Sherman, S. J. (2007). The effect of level of construal on the temporal distance of activity enactment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(1), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.009

- Lim, W. M. (2015). Enriching information science research through chronic disposition and situational priming: A short note for future research. Journal of Information Science, 41(3), 399–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551515577913

- Lim, W. M. (2021). Conditional recipes for predicting impacts and prescribing solutions for externalities: The case of COVID-19 and tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 314–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1881708

- Lim, W. M., Ahmed, P. K., & Ali, M. Y. (2019). Data and resource maximization in business-to-business marketing experiments: Methodological insights from data partitioning. Industrial Marketing Management, 76, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.08.007

- Lim, W. M., Ahmed, P. K., & Ali, M. Y. (2022). Giving electronic word of mouth (eWOM) as a prepurchase behavior: The case of online group buying. Journal of Business Research, 146, 582–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.093

- Lindström, A., Berg, H., Nordfält, J., Roggeveen, A. L., & Grewal, D. (2016). Does the presence of a mannequin head change shopping behavior? Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.04.011

- Liviatan, I., Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2008). Interpersonal similarity as a social distance dimension: Implications for perception of others’ actions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(5), 1256–1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.04.007

- Lobb, A. E., Mazzocchi, M., & Traill, W. B. (2007). Modelling risk perception and trust in food safety information within the theory of planned behaviour. Food Quality and Preference, 18(2), 384–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2006.04.004

- Lourenco, J. S., Ciriolo, E., Almeida, S. R., & Dessart, F. (2016). Behavioural insights applied to policy-Country overviews 2016. European Commission.

- Manning, L., & Soon, J. M. (2016). Building strategic resilience in the food supply chain. British Food Journal, 118(6), 1477–1493. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-10-2015-0350

- Marucheck, A., Greis, N., Mena, C., & Cai, L. N. (2011). Product safety and security in the global supply chain: Issues, challenges and research opportunities. Journal of Operations Management, 29(7–8), 707–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2011.06.007

- Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., & Kirchner, J. (2008). Is actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta-analysis of actual and perceived similarity. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 25(6), 889–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508096700

- Moreira, M. J., García-Díez, J., de Almeida, J., & Saraiva, C. (2021). Consumer knowledge about food labeling and fraud. Foods, 10(5), 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10051095

- Mrkva, K., Cole, J. C., & Van Boven, L. (2021). Attention increases environmental risk perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 150(1), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000772

- Nardi, V. A. M. (2019). I am the target! Effects of food safety risk perception on consumer behavior: The moderation role of prototype perception and visual attention to safety labels. Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos.

- Nardi, V. A. M., Teixeira, R., Ladeira, W. J., & Santini, F. D. O. (2020). A meta-analytic review of food safety risk perception. Food Control, 112, 107089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107089

- Narrod, C., Roy, D., Okello, J., Avendaño, B., Rich, K., & Thorat, A. (2009). Public–private partnerships and collective action in high value fruit and vegetable supply chains. Food Policy, 34(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.10.005

- Pieters, R., & Wedel, M. (2004). Attention capture and transfer in advertising: Brand, pictorial, and text-size effects. Journal of Marketing, 68(2), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.2.36.27794

- Pieters, R., Wedel, M., & Batra, R. (2010). The stopping power of advertising: Measures and effects of visual complexity. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.5.048

- Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001

- Ran, T., Yue, C., & Rihn, A. (2017). Does nutrition information contribute to grocery shoppers’ willingness to pay? Journal of Food Products Marketing, 23(5), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2015.1048027

- Rihn, A., Wei, X., & Khachatryan, H. (2019). Text vs. logo: Does eco-label format influence consumers’ visual attention and willingness-to-pay for fruit plants? An experimental auction approach. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 82, 101452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2019.101452

- Roosen, J. (2003). Marketing of safe food through labeling. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 34, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.27058

- Roth, A. V., Tsay, A. A., Pullman, M. E., & Gray, J. V. (2008). Unraveling the food supply chain: Strategic insights from China and the 2007 recalls. The Journal of Supply Chain Management, 44(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2008.00043.x

- Samant, S. S., & Seo, H.-S. (2016). Effects of label understanding level on consumers’ visual attention toward sustainability and process-related label claims found on chicken meat products. Food Quality and Preference, 50, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.01.002

- Sato, T. R., Watanabe, K., Thompson, K. G., & Schall, J. D. (2003). Effect of target-distractor similarity on FEF visual selection in the absence of the target. Experimental Brain Research, 151(3), 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-003-1461-1

- Shafir, E., & LeBoeuf, R. A. (2002). Rationality. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 491. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135213

- Siegrist, M., & Hartmann, C. (2020). Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nature Food, 1(6), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0094-x

- Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of risk. Science, 236(4799), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3563507

- Spence, C., Okajima, K., Cheok, A. D., Petit, O., & Michel, C. (2016). Eating with our eyes: From visual hunger to digital satiation. Brain & Cognition, 110, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2015.08.006

- Sun, L., Hu, L., Zheng, F., Sun, Y., Cao, H., & Wu, L. (2021, July). Influence of HNB product packaging health warning design on risk perception based on eye tracking. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Washington, DC (pp. 390–402). Springer International Publishing.

- Süssenbach, P., Niemeier, S., & Glock, S. (2013). Effects of and attention to graphic warning labels on cigarette packages. Psychology & Health, 28(10), 1192–1206. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2013.799161

- Tanemura, N., & Hamadate, N. (2022). Association between consumers’ food selection and differences in food labeling regarding efficacy health information: Food selection based on differences in labeling. Food Control, 131, 108413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108413

- Thornton, B., Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (2002). Risk perception and prototype perception: Independent processes predicting risk behavior. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(7), 986–999. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616720202800711

- van Herpen, E., van Nierop, E., & Sloot, L. (2012). The relationship between in-store marketing and observed sales for organic versus fair trade products. Marketing Letters, 23(1), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-011-9154-1

- Wertheimer, M. (1938). Laws of organization in perceptual forms. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Wongprawmas, R., Canavari, M., & Waisarayutt, C. (2015). A multi-stakeholder perspective on the adoption of good agricultural practices in the Thai fresh produce industry. British Food Journal, 117(9), 2234–2249. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-08-2014-0300

- World Health Organization. (2019, June 4). Food safety key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety

- Yang, R. J., Huang, W., Zhang, L. S., Thomas, M., & Pei, X. F. (2009). Milk adulteration with melamine in China: Crisis and response. Quality Assurance and Safety of Crops & Foods, 1(2), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1757-837X.2009.00018.x

- Young, I., Reimer, D., Greig, J., Turgeon, P., Meldrum, R., & Waddell, L. (2017). Psychosocial and health-status determinants of safe food handling among consumers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Control, 78, 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.03.013

- Zellmer-Bruhn, M. E., Maloney, M. M., Bhappu, A. D., & Salvador, R. (2008). When and how do differences matter? An exploration of perceived similarity in teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 107(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.01.004