Abstract

In this article, the authors introduce precorrection as a feasible, effective strategy for teachers and families to use to increase engagement and minimize disruptive behavior in a range of learning contexts. The authors provide step-by-step guidance to illustrate how precorrection can be used by teachers in in-person and remote learning environments as well as how families can incorporate precorrection into daily routines at home.

Teacher: Mrs. Howard is the teacher in the Sunflower Room at Sunny Days Preschool, a Comprehensive, Integrated, Three-tiered (Ci3T) Early Childhood Center (see Box 1). She has 10 three-year-olds in her class that are always full of energy and excited to learn! Mrs. Howard emphasizes strategies in her classroom that keep her young students engaged, focused, and ready to learn. As part of Sunny Days’ Ci3T model, she has a Mission Statement, Purpose Statement, and School-Wide Expectations posted in her classroom. Mrs. Howard teaches the school-wide expectations – Be Safe, Be Kind, and Do Your Best – to students as soon as they start in her classroom to make sure they are aware of what is expected. Mrs. Howard also knows the importance of continually teaching expectations for new activities, so she teaches the Sunflower Expectations before any potential challenges occur. When children meet these expectations, Mrs. Howard uses Sun Bucks, paired with behavior-specific praise to recognize her students for a job well done!

Student: Mila is a three-year-old in Mrs. Howard’s classroom. This is Mila’s first year in preschool and she is very excited to have so many new friends as well as fun activities. Mila learned the Sunflower Expectations in Mrs. Howard’s class on her first day and knows when it is time to sit quietly on her square and listen and when she can talk and play with her new friends. Sometimes, during center time, it is hard to Mila to remember that she needs to take turns when playing with others. She directs the play in her center for all students who are playing there. Most often the other children play along, however; when another friend has an idea of something different to play, Mila uses unkind words toward the friend to try to control the play. This results in hurt feelings for all.

Family: Mila has full support from her parents at home who helped her learn the expectations in Mrs. Howard’s class. Mrs. Howard made sure that Mila’s family knew the Sunflower Expectations that are used in class and all other areas around the school so that they could help Mila learn and reinforce what was expected in the Sunflower Room. Mrs. Howard shared some ideas to support Mila in using kind words when negotiating play with friends.

Comprehensive, Integrated, Three-tiered (Ci3T) Models of Prevention

What is Ci3T?

Ci3T is an integrated tiered system of supports addressing academic, behavioral (positive behavior interventions and supports [PBIS]), and social and emotional well-being learning domains. Ci3T is a district or schoolwide system with a continuum of evidence-based practices, programs, and strategies for all students at Tier1, some students at Tier 2 and a few students at Tier 3. The continuum provides a structure for making data-informed decisions to meet students’ identified needs at the earliest signs of concern. School Ci3T Leadership Teams use multiple sources of student data such as, academic and behavior screening, office discipline referrals, attendance, nurse visits; as well as programmatic data such as treatment integrity, stakeholders’ views, to drive all decision-making efforts. In addition to using multiple sources of data to inform instruction for students, Ci3T also features data-informed professional learning for adults. Ci3T is a broadening of traditional Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS), developed in the late 1990s to address social and emotional well-being.

See Lane, Oakes, & Menzies (Citation2023).

Providing students with a safe and predictable learning environment is an important component of a productive and enjoyable school experience, and goes hand in hand with implementing a Comprehensive, Integrated, Three-tiered (Ci3T) Model of Prevention (see Box 1; Lane, Oakes, & Menzies, Citation2023 this issue). Recently, learning environments have shifted from remote, to hybrid, to in-person and in some cases back and forth multiple times between the three. These changes make providing a predictable learning environment even more important to ensure students are set up for success, in addition to highlighting the importance of a positive relationship between school and home life. Using low intensity supports is a way teachers and families can help set the stage for positive and productive interactions at school and at home.

Precorrection is a proactive, low intensity support teachers and families can use to remind students of expected behaviors before they transition to a new setting or begin a new activity. When using precorrection, adults use the eight-step process (see Lane et al., Citation2015; Ennis et al., Citation2018) to identify areas where challenging behavior may occur, create a plan for reminding students of the expectations before they enter the area, and then acknowledge students for meeting the expectations. Precorrection involves thinking through challenges that might arise in specific settings to set the stage for desired behaviors to occur. In addition to changing components of the environment, adults also ensure students know what the expected behaviors are and how to do them.

Precorrection is a flexible strategy that can be used across grade levels and settings, and is a component of other low-intensity, research-based strategies such as active supervision (see Allen et al., Citation2020). This strategy is useful when implemented as part of a schoolwide, multi-tiered system like Ci3T or it can be used independently by educators to support students. One main benefit of precorrection is the opportunity to intervene before challenges occur.

Purpose

In this article, we introduce precorrection as a proactive, efficient strategy that can minimize the occurrence of disruptive behavior and can be used in several settings. We illustrate how teachers can use this strategy while teaching in an in-person or virtual learning environment and how families can use the strategy at home. Precorrection allows adults to shift their behavior from responding when challenges arise to preventing challenges by clearly stating what is expected from students and reinforcing them for engaging in those expected behaviors. Precorrection can be used with students from preschool to high school (and beyond!). In this article, we provide a focused illustration of using precorrection at the preschool level.

Introduction to precorrection

What is precorrection?

Precorrection involves noting the behavior you would like to see, with the cue or prompt taking place before any challenging or undesirable behavior takes place. This strategy helps address behavior problems before they occur opposed to waiting and reacting after a challenge arises. To use precorrection, adults anticipate problem behavior that may arise in a specific area or activity, remind students of the expected behaviors before the transition to that area or before the activity begins, and reinforce students for meeting the clearly defined expectations. Precorrection can involve visual or verbal prompts. At school, this could be using a schoolwide expectation matrix. For example, the teacher could point to remind students of the expectations in the cafeteria before leaving for lunch (e.g., “When you are done in the cafeteria, your trash goes into the trash bin before you go outside”). At home, this could be stating the expectations for getting ready for school in the morning (e.g., “After you are finished eating breakfast, remember to clear your place at the table before getting dressed for school”).

What is the research behind precorrection?

The use of precorrection has been examined in classrooms across PK—12th grade contexts as a proactive strategy to promote students’ expected school behaviors. The existing research evidence was examined to determine if precorrection had sufficient evidence to be deemed an evidence-based practice (Ennis et al., Citation2017). Authors identified 10 single-case design studies to be included in the review. Authors applied the Council for Exceptional Children’s (CEC) Standards for Evidence-Based Practices in Special Education (CEC, Citation2014). Five articles including 20 student participants were found to meet the standards (80% weighted criterion, an adaptation in which raters coding these articles can provide partial credit for studies that include most—but not all quality indicators). This approach allows for a wider set of studies to be included, when determining if a strategy, practice, or program meets the criteria for the evidence-based practice classification. For precorrection, there was sufficient evidence to establish precorrection as an evidence-based practice to support positive learning environments for students and teachers. There has been little to no research conducted in home settings, however, precorrection has been examined in instructional (e.g., classrooms) and non-instructional (e.g., playground) school settings with success and procedures can generalize to any context. Next, we highlight a few studies across the grade span.

Wahman and Anderson (Citation2021) examined the use of precorrection in three preschool classrooms in the Midwestern U.S. region using single-case design methodology. A diverse group of nine teachers (three teaching teams) and three children with disabilities participated in an antecedent-based intervention. For each child, teachers established a targeted routine in need of additional support (e.g., transition to naptime) and specific target behaviors with operational definitions (e.g., elopement). The precorrection intervention package included the use of three steps (1) scripted stories, (2) asking questions about the expected desired behaviors, and (3) brief roleplay. The intervention lasted on average six minutes prior to the targeted routine with students in small groups or pairs. Teachers used general praise contingent on the student’s use of the expected behavior. The treatment integrity form (list of intervention steps to record adherence) was used to provide teachers with performance feedback. Results suggested students demonstrated an increase in their demonstrations of their targeted behavior. In terms of teacher practices, there was not an observed increase in teachers’ use of general praise during the intervention, with low levels of observed use of praise when students met behavioral expectations (the targeted behavior). Teachers indicated the intervention had high social validity (agreement with goals, procedures, and outcomes; Wolf, Citation1978). Specifically, teachers reported they felt students’ behavior improved, as well as students’ attention to multi-step directions.

Lewis et al. (Citation2000) explored the use of precorrection with active supervision for elementary students to reduce problem behaviors on the playground at one elementary school implementing PBIS. Authors employed single-case methodology with a multiple baseline across group design. All school staff (n = 24) and students (n = 475) participated in this study. There were three elements to the intervention (1) teachers reviewed school expectations and related social skills daily for one week, (2) playground monitors reviewed playground expectations for one week, and (3) precorrection and active supervision were implemented. For the precorrection element, teachers reviewed the school and playground expectations prior to students transitioning to the playground. Then, playground monitors used active supervision (e.g., moving, scanning, interacting; see Austin et al., Citation2023 for details) with attention to reinforcing meeting of expectations, effort correction (reminders when infractions occurred), and their own movement and scanning of the environment. Results indicated low rates of problem behaviors during structured activities. For unstructured activities, rates of problem behaviors on the playground decreased with the use of the intervention. Of note, there were no clear observed effects of the intervention on the playground monitors’ behavior, potentially because monitors were aware of the observer’s presence and the intervention prior to baseline. The study demonstrated the potential of an efficient, low-intensity intervention to reduce problem behaviors during unstructured time on the playground for students attending a PBIS school.

In a secondary example, Hunter and Haydon (Citation2019) conducted a study to evaluate the effect of a package intervention on middle school students’ disruptive behaviors and teachers’ use of reprimands. Three classroom teachers in one urban middle school in the southeastern U.S. participated in this study. The three components of the intervention package were: precorrection, explicit timing, and active supervision. Teachers established behavioral expectations and instituted transition procedures. For precorrection, the teacher reviewed expectations at the start of each class, asked students to repeat expectations and checked for understanding. Explicit timing included a specific agenda for the class period, with a one-minute transition warning and 10 second countdown. Then, teachers used active supervision during the activity (e.g., scanning, prompting, interacting, and using positive feedback). Treatment integrity data showed teachers were able to implement the intervention with high levels of integrity (as designed). Results showed an immediate reduction in disruptive behaviors as well as teacher redirection across all teachers. Social validity of the intervention reported by teachers was high. This study demonstrated the positive effect of implementing this proactive intervention package with middle school students.

These are three examples of many successful tests of precorrection across the PK–12 continuum. Researchers have investigated the use of precorrection across school settings such as classrooms (Haydon & Kroeger, Citation2016), morning gym (Haydon & Scott, Citation2008), in the cafeteria and during transitions (Colvin et al., Citation1997), and on the playground (Franzen & Kamps, Citation2008; Lewis et al., Citation2000). These settings have been in general (De Pry & Sugai, Citation2002) and special education contexts such as resources classrooms (Miao et al., Citation2002), and self-contained special education classrooms (Sprague & Thomas, Citation1997) to address a range of behaviors (Ennis et al., Citation2017). As illustrated, precorrection has been determined to be effective at the preschool (Head Start; Smith et al., Citation2011), elementary (Ennis et al., Citation2017), middle school (Haydon et al., Citation2012), and high school (Haydon & Kroeger, Citation2016) levels. Precorrection is a versatile strategy that is often used with other strategies such as active supervision (to monitor and promote the use of the expectations) and behavior specific praise (following the demonstration of the expectation). In short, precorrection has demonstrated increases of on-task behaviors and decreases of problem behaviors.

Step-by-step procedures and illustrations for incorporating precorrection

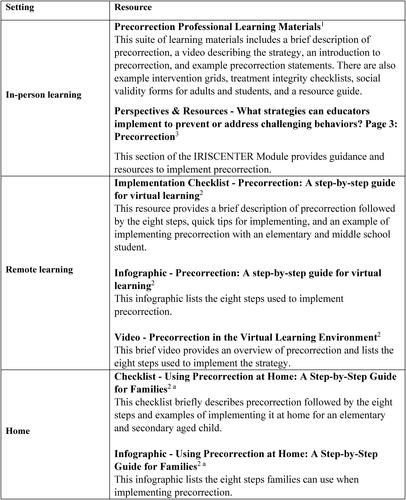

Given precorrection is an evidence-based practice, we offer step-by-step guidance and illustrations for general and special education teachers interested in using precorrection during in-person and during remote instructional contexts (see Ennis et al., Citation2018 for additional illustrations for using precorrection in person). We follow these two school-based illustrations with an illustration for families to use precorrection in the home setting. In we summarize steps for use in schools (in-person and remote) and home settings. In , we provide free resources for educators and families to help with the implementation of precorrection.

Figure 1. Additional precorrection resources.

Note. Resources listed above are free and are provided by the Ci3T Research Team. 1Available to download at ci3t.org/pl. 2Available to download at ci3t.org/covid. aResources are also available in Spanish. 3Available through the IRISCENTER. Module name: Addressing Challenging Behaviors (Part 2, Elementary): Behavioral Strategies.

Table 1. Precorrection: implementation checklist.

School: in-person instruction

Mrs. Howard noticed that during center time in the preschool classroom, Mila would often have difficulty sharing and playing with her classmates during student-directed activities. For example, Mila tried to dictate which toys each child used during play, refused to share or trade toys, and ignored other peers’ ideas during play. At times, Mila used unkind words toward a peer when they suggested something different to play, as examples, “You’re stupid” or “I don’t like you.” See for the steps for using precorrection to support students in in-person education.

Step 1. Mrs. Howard decided to use precorrection to help Mila remember to show kindness during center play time.

Step 2. Mrs. Howard thought about the Sunflower Expectations and decided to focus on the behaviors for Be Kind. This included using kind words and actions, such as asking nicely if friends would like to play in a particular way, taking turns deciding how to play, and sharing toys with friends.

Step 3. Mrs. Howard posted copies of the Sunflower Expectation Matrix into areas of the classroom that were accessed during center time, making sure they were at eye-level so the students could see the poster and serve as a reminder for herself to prompt Mila.

Step 4. Mrs. Howard then checked her schools validated social skills curriculum to find lessons about using kind words and actions. She worked with the whole class and small groups to reteach related lessons to students, ensuring there were opportunities for them to practice.

Step 5. As students practiced using kind words and actions, Mrs. Howard used behavior specific praise paired with a Sun Buck to reinforce students for the expected behavior.

Step 6. Then, Mrs. Howard added notes in her planner to remind students of those skills and expectations before center time began.

Step 7. During center time as Mrs. Howard actively supervised the class, she tallied the number of times Mila demonstrated the Be Kind expectation during center play time by asking nicely to play in a certain way, agreeing to an idea from a peer during play, or sharing toys during play.

Step 8. At the end of the day, Mrs. Howard asked Mila if she thought that reminding her of the Be Kind expectation before center time helped her be kinder to her friends. After a full week, Mrs. Howard also met with Mila and her parents to talk about how precorrection was working for Mila.

School: remote instruction

As stated previously, there is sufficient evidence to support precorrection as an effective, evidence-based strategy for use in in-person learning environments (Ennis et al., Citation2017). In addition, precorrection can be used as a proactive strategy to help set the stage for a positive experience in remote learning environments (Austin et al., Citation2020; Ennis et al., Citation2018). This strategy can support educators in preventing the occurrence of undesirable or problematic behavior when teaching in a virtual environment as many educators did during the shift to virtual learning caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Below we provide this illustration of how Mrs. Howard used precorrection with her class at Sunny Days Preschool when in a remote school setting.

Mrs. Howard has been working with her students in a remote learning environment for three weeks. She worked with her school and district leaders to ensure all students had the necessary supplies and technology to participate in their asynchronous class time every day. Also, she worked with families to ensure they and their child were able to access the learning platform and had access to the needed bandwidth to support all members of the family who were working or learning remotely. She noticed some of her students were excited to log into class every day, and they enjoyed seeing her, the other professionals in the class, and their classmates; however, this often led to students, including Mila, unmuting to say hello to friends or interject with an exciting, often off topic, story they would like to tell after morning meeting had begun. Mrs. Howard decided to use an efficient and low intensity strategy to support engagement in the online classroom environment.

Step one: identify a virtual learning activity or setting and anticipated problem behaviors

Mrs. Howard decided to use precorrection during the morning meeting time when students first logged onto the online classroom to start their day to help Mila and other students in class have a productive and engaged morning meeting. During that activity, she gave students a few minutes to log into the platform and get their cameras and audio working, greet each other, and share brief stories as they liked. Then, she transitioned the students to morning meeting.

Step two: determine the expected behaviors

When the school transitioned to remote instruction, the Ci3T Leadership Team provided teachers with schoolwide expectations for the remote classroom. Mrs. Howard thought about the remote Sunflower Expectations and decided to focus on Be Kind and Do Your Best for morning meeting. Specifically, she decided to focus on a few behaviors in their Sunflower Expectation Matrix such as listening quietly when others are talking, use encouraging words to be kind, and take turns and share your ideas on the topic to do their best.

Step three: adjust the virtual environment to set students up for success

After she determined the expectation for the class meeting, Mrs. Howard spent time thinking about how she would set students up for success right as they entered the remote classroom and began their day with the morning meeting. Mrs. Howard had many visual cues in the classroom to support her preschoolers. So, she decided that it would be important to have a visual of their Sunflower Expectations for the virtual classroom. She considered hanging one on the wall behind her in her ‘home classroom’ but then decided to create the matrix as her virtual background. She felt either choice would support students with the needed visual prompt. With it posted as it would be in the classroom, she was also prompted to refer to it when using precorrection. She also added the expectations to the slides she used when sharing her screen during morning meeting.

Step four: provide opportunities to practice expected behaviors

For the next few days, Mrs. Howard spent time explicitly teaching and reteaching the remote expectations to her students. She went over what taking turns means and provided examples of what that might look like in morning meeting. She had students practice taking turns with one another as they shared stories, and gave students still practicing that skill, like Mila, several opportunities to wait until it was her turn to talk or share.

Step five: provide immediate and specific reinforcement to students engaging in expected behaviors

When first teaching the expectations, Mrs. Howard provided behavior specific praise to students when she saw them using the skill, including when students were practicing the behavior. She also used Sun Bucks, delivered electronically during remote instruction, to reinforce students for meeting the expectations.

Step six: develop a prompting plan to regularly remind students of the expected behavior

Mrs. Howard thought about the structure of the morning meeting with her class, and when the best time to remind students of the expectations would be. She reminded the entire class of the expectation before they transitioned to the meeting by stating the expectations, pointing to the expectation listed on her virtual background, and asking students who needed the most practice to share examples of the expected behavior. She also decided to prompt students before each section of the meeting.

Step seven: develop a monitoring plan to determine the effectiveness of the precorrection plan

To see if using the strategy was working as desired, Mrs. Howard kept a tally of the number of how many times she reminded students of the expected behavior, and how often each part of the morning meeting was completed without an interruption.

Step eight: offer students an opportunity to give feedback on this strategy

After using the strategy for a week, Mrs. Howard asked her students while meeting with them in small groups how they felt about being reminded of the expectations and acknowledged for meeting the expectations.

Home: a guide for families

The evidence for the use of precorrection to support students in meeting expectations when transitioning to a new setting or activity in instructional and non-instructional settings, suggests precorrection would be useful at home settings as well. As you will see in the example below, the steps for using precorrection in home settings are similar to how the strategy is used in school contexts. See for the steps for using precorrection in home settings.

Step 1. Three-year-old Mila was often tired in the mornings when she first woke up and was difficult to get out of bed. This worried Mila’s parents that she would arrive late to her new preschool and would not be ready to meet the Sunflower Expectations.

Step 2. It was important that she have plenty of time to eat a healthy breakfast and arrive on time to Mrs. Howard’s Sunflower Room at Sunny Days Preschool, so that she was ready to learn.

Step 3. Mila’s parents made sure that she was in bed by eight o’clock every night, so she was well rested in the morning when it was time to awake and get ready for school.

Step 4. This routine was new for Mila when she started preschool, so they made sure to practice the routine for a couple of weeks prior to her starting at Sunny Days.

Step 5. They also made sure to praise Mila for getting herself up and dressed on her own, and for being at the breakfast table as soon as she was ready so that they could be in the car and arrive at Sunny Days on time.

Step 6. To help Mila remember her morning routine expectations, Mila’s parents found a book to read to Mila every evening about a preschooler who had a similar evening and morning routine that Mila really enjoyed hearing.

Step 7. Mornings went smoothly for Mila, her parents, and Mrs. Howard when Mila knew what was expected in the mornings and was ready to learn when she arrived on time to the Sunflower Room at Sunny Days Preschool.

Step 8. Mila’s parents made sure to check-in with Mila regularly to ensure she was having positive and productive days as a result of their precorrection steps.

Moving forward with precorrection

Precorrection is a feasible and effective strategy that can be used by educators and families to increase engagement and minimize disruptive behavior in varied learning and home environments. It can be used to support students in PK–12th grade in conjunction with other low intensity strategies such as active supervision and behavior specific praise. Precorrection, in combination with these other techniques and strategies as described, is an effective tool in and out of the classroom to support students in general education and special education settings. By reminding students of expected behaviors before activities or contexts that may cause inappropriate behaviors, teachers can increase the probability of success during that high-risk scenario. There are a variety of resources (see ) available for educators and families to learn about precorrection and other low-intensity strategies. Offering these through a range of professional learning approaches (Common et al., Citation2021; Lane et al., Citation2015) allows educators to build their knowledge and confidence to design, implement and evaluate the effectiveness of precorrection, through preferred approached. Ultimately, these strategies promote positive, productive, and joyful school and home environments.

As educators implement precorrection in school contexts (in-person or remote), considerations can also be made for communicating information about the strategy with families or guardians to support the use of the strategy in home settings. Educators might consider sharing the checklist (see the home settings column of ) when sharing how they might use the strategy at home. They might consider sharing specific examples with families for how they use the strategy in the school setting and offer specific examples for the home setting, when families share a specific concern, such as Mila’s parents’ concern in this paper.

Educators within and outside of a tiered system of supports, such as Ci3T, can easily use precorrection in in-person learning environments, as well as in a remote learning environment to identify an instructional context, adjust the environment as needed, and remind students of expected behaviors in a virtual environment (Austin et al., Citation2020). Precorrection can be used as part of an integrated lesson plan, where educators can identify areas to use low intensity strategies, in addition to integrating academic, behavior, and social domains in the classroom, a core component of Ci3T. For example, a teacher might use precorrection in an academic lesson to remind students of the expected behavior or a social skill that was taught previously during the week. Families can use precorrection at home to help decrease the chances of challenging behavior occurring by reminding children or youth what is expected from them in the context or environment they are about to enter (Lane et al., Citation2020). For example, Mila’s family used precorrection to help her be on time for preschool in the mornings.

Summary

In this paper, we introduced precorrection as a proactive strategy that can be used to decrease undesirable behavior from occurring both at school and at home. We illustrated how teachers can use the strategy in an in person and remote environment, and how families can use the strategy at home.

Disclosure statement

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, G. E., Common, E. A., Germer, K. A., Lane, K. L., Buckman, M. M., Oakes, W. P., & Menzies, H. M. (2020). A systematic review of the evidence base for active supervision in PK–12 settings. Behavioral Disorders, 45(3), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742919837646

- Austin, K. S., Allen, G. E., Brunsting, N. C., Common, E. A., & Lane, K. L. (2023), Active supervision: Empowering teachers and families to support students in varied learning contexts. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth.

- Austin, K. S., Lane, K. S., Pérez-Clark, P., Allen, G. E., Oakes, W. P., Lane, K. L., & Menzies, H. M. (2020, August). Precorrection: A step-by-step guide for virtual learning. Ci3T Strategic Leadership Team. www.ci3t.org

- Colvin, G., Sugai, G., Good, R. H., III., & Lee, Y.-Y. (1997). Using active supervision and precorrection to improve transition behaviors in an elementary school. School Psychology Quarterly, 12(4), 344–363. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088967

- Common, E. A., Buckman, M. M., Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Royer, D. J., Chafouleas, S. M., Briesch, A. M., & Sherod, R. (2021). Project ENHANCE: Assessing professional learning needs for implementing comprehensive, integrated, three-tiered (Ci3T) prevention models. Education and Treatment of Children, 44(3), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-021-00049-z

- Council for Exceptional Children (2014). CEC standards for evidence-based practices in special education. Author.

- De Pry, R., & Sugai, G. (2002). The effect of active supervision and pre-correction on minor behavioral incidents in a sixth grade general education classroom. Journal of Behavioral Education, 11(4), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021162906622

- Ennis, R. P., Lane, K. L., Menzies, H. M., & Owens, P. P. (2018). Precorrection: An effective and efficient low-intensity strategy to support student success. Beyond Behavior, 27(3), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074295618799360

- Ennis, R. P., Royer, D. J., Lane, K. L., & Griffith, C. E. (2017). A systematic review of precorrection in PK–12 settings. Education and Treatment of Children, 40(4), 465–495. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2017.0021

- Franzen, K., & Kamps, D. (2008). The utilization and effects of positive behavior support strategies on an urban school playground. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10(3), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300708316260

- Haydon, T., DeGreg, J., Maheady, L., & Hunter, W. (2012). Using active supervision and precorrection to improve transition behaviors in a middle school classroom. Journal of Evidence-Based Practices for Schools, 13(1), 81–94.

- Haydon, T., & Kroeger, S. D. (2016). Active supervision, precorrection, and explicit timing: A high school case study on classroom behavior. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60(1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2014.977213

- Haydon, T., & Scott, T. M. (2008). Using common sense in common settings: Active supervision and precorrection in the morning gym. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43(5), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451208314491

- Hunter, W. C., & Haydon, T. (2019). Implementing a classroom management package in an urban middle school: A case study. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 63(1), 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2018.1504740

- Lane, K. L., Menzies, H., Ennis, R. P., & Oakes, W. P. (2015). Supporting behavior for school success: A step-by-step guide to key strategies. Guilford Press.

- Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., & Allen, G. E. (2020). Using precorrection at home: A step-by-step guide for families. Ci3T Strategic Leadership Team. www.ci3t.org

- Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., & Menzies, H. (2023). Using low-intensity strategies to support engagement: Practical applications in remote learning environments for teachers and families. Preventing School Failure. 67(2), 79–82.

- Lewis, T. J., Colvin, G., & Sugai, G. (2000). The effects of pre-correction and active supervision on the recess behavior of elementary students. Education and Treatment of Children, 23(2), 109–121.

- Miao, Y., Darch, C., & Rabren, K. (2002). Use of precorrection strategies to enhance reading performance of students with learning and behavior problems. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 29(3), 162–174.

- Smith, S. C., Lewis, T. J., & Stormont, M. A. (2011). The effectiveness of two universal behavioral supports for children with externalizing behavior in Head Start classrooms. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13(3), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300710379053

- Sprague, J., & Thomas, T. (1997). The effect of a neutralizing routine on problem behavior performance. Journal of Behavioral Education, 7(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022827622948

- Wahman, C. L., & Anderson, E. J. (2021). A precorrection intervention to teach behavioral expectations to young children. Psychology in the Schools, 58(7), 1189–1208. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22531

- Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203