ABSTRACT

Spontaneous (i.e., heuristic, fast, effortless, and associative) processing has clear advantages for human cognition, but it can also elicit undesirable outcomes such as stereotyping and other biases. In the current article, we argue that biased judgements and behaviour that result from spontaneous processing can be reduced by activating various flexibility mindsets. These mindsets are characterised by the consideration of alternatives beyond one’s spontaneous thoughts and behaviours and could, thus, contribute to bias reduction. Research has demonstrated that eliciting flexibility mindsets via goal and cognitive conflicts, counterfactual thinking,, recalling own past flexible thoughts or behaviour, and adopting a promotion focus reduces biases in judgements and behaviour. We summarise evidence for the effectiveness of flexibility mindsets across a wide variety of important phenomena – including creative performance, stereotyping and prejudice, interpersonal behaviour, and decision-making. Finally, we discuss the underlying processes and potential boundary conditions.

According to many theories in social psychology, people (mostly) use two different information processing modes: a spontaneous mode (i.e., heuristic, fast, effortless, and associative processing) in which people follow dominant response inclinations, and a controlled mode (i.e., systematic, slow, effortful, and rule-based processing; e.g., Chaiken & Trope, Citation1999; Kahneman, Citation2011; Strack & Deutsch, Citation2004). Spontaneous processing is often adaptive, as it helps to cope with complex environments efficiently (e.g., Gigerenzer, Citation2008; Macrae et al., Citation1994). Notwithstanding its usefulness, social psychology has identified many undesirable outcomes (i.e., biases) that result from spontaneous processing, such as stereotyping and prejudice. In these cases, dual process theories suggest controlled processing as a potential means to correct these biases. There are, however, also good reasons to assume that exerting control is in many cases not sufficient to avoid biases resulting from spontaneous processes (e.g., Bargh, Citation1999; Moskowitz & Vitriol, Citation2022). Research on the ironic effects of thought suppression has, for instance, repeatedly demonstrated that effortful suppression can lead to even higher activation of the to-be-suppressed thoughts (Wang et al., Citation2020; Wegner, Citation1994).

In the current article, we summarise our own research and that from other labs testing the hypothesis that biases in judgment and behaviour, which result from spontaneous processing and dominant response tendencies, can be reduced by activating a flexible processing style. A flexible processing style, which can be activated through a range of different mindset manipulations (e.g., cognitive or goal conflicts, counterfactual thinking), leads to considering alternatives beyond the dominant or spontaneous thoughts and behaviour; it moves one beyond dominant associations without requiring substantial effort. It is, thus, distinct from the controlled mode and constitutes an alternative means to avoid unwanted outcomes resulting from spontaneous processes.

The current article aims to summarise the debiasing effects of a flexible processing style that can be activated via a range of different mindset manipulations. Overall, the research reported here highlights the debiasing effects of these flexibility mindsets in a variety of domains, from creative performance to stereotyping and prejudice, interpersonal behaviour, and decision-making. Integrating research from several domains, we contribute to a broader understanding of the processes and potentials associated with flexibility mindsets. Given their adaptive properties, flexibility mindsets have a high potential to inform the development of interventions against unwanted biases that result from spontaneous processing. Before we summarise research on their debiasing effects, we provide a brief definition of what we call flexibility mindsets and an overview of the procedures that activate them.

Flexibility mindsets

In the research summarised here, mindsets are defined as activated cognitive procedures that influence which mental operations are applied and which actions are chosen from various alternatives (Gollwitzer et al., Citation1990). For example, an implemental mindset is one that specifies procedures and operations for turning a goal into action, and is typically activated by forming concrete intentions, as opposed to general deliberation about a desired state. Processing styles like this are, however, not tied to the situation in which they were activated. Instead, they can also affect thoughts and behaviour in other situations to which it is applicable – in short: mindsets tend to carry over. Accordingly, we define a flexibility mindset as an activated cognitive strategy that leads to more divergent thinking, the use of broad cognitive categories, and the switching between categories. Thus, we use the term flexibility in line with the creativity literature (e.g., De Dreu et al., Citation2011; Newell & Simon, Citation1972). Please note that our current use of the term mindset is different from Dweck’s prominent implicit theories approach, in which mindsets refer to a set of conscious beliefs about own and other people’s development over time, rather than an activated processing style (Dweck, Citation2017).

There are at least five different priming procedures that elicit a flexibility mindset: goal conflicts, cognitive conflicts, counterfactual thinking, thinking back to own past creative performance, and a promotion focus. These mindset priming procedures have been discussed in unconnected literatures, but as the research summarised below has shown, they all have one thing in common: they can overcome biases that result from spontaneous processing due to increased cognitive flexibility.

Goal conflicts

During goal pursuit, people often experience a conflict because the actions required for reaching one goal prevent reaching another goal. Imagine, for example, a student who wants to be well-prepared for an upcoming exam but has just been invited to join friends at a bar. Dealing with such a conflict requires self-regulatory resources that are then no longer available for goal pursuit. Thus, goal conflicts often impair task performance (Shah & Kruglanski, Citation2002) and decision quality (Tversky & Shafir, Citation1992). Resolving such a goal conflict requires the application of cognitive procedures that can carry over to subsequent situations. Going through a goal conflict, thus, elicits a conflict mindset.

This conflict mindset can be induced, for instance, by a priming procedure in which words related to conflicting goals are shown in a lexical decision task (e.g., “bar”, “party” and “lecture”, “grades” vs. only neutral words in the control condition; Kleiman & Hassin, Citation2013). Alternatively, this mindset can be activated by letting participants think back to a recent goal conflict (vs. to a regular day in one’s life in the control condition; Stern & Kleiman, Citation2015). It can also be induced by a choice conflict elicited through distractors in a multi-trial paradigm (Kleiman et al., Citation2014). In all those situations people are required to resolve a goal conflict, which means that they need to either mentally restructure the situation and find means to attain both goals simultaneously or identify which of the two goals is more important to them. In both cases, they need to show some flexibility. A substantial body of research has demonstrated that the flexible strategies applied to solve the goal conflict can, in turn, carry over and increase the flexibility in subsequent and even unrelated tasks (see Kleiman & Enisman, Citation2018). Thus, goal conflicts can activate a flexibility mindset.

Cognitive conflicts

Cognitive conflicts arise when two conflicting cognitions are simultaneously activated, for instance, when people are faced with schema-inconsistent information (e.g., a priest in front of a mosque). To make sense of such a situation, people need to mentally restructure it (e.g., the priest wants to improv relations with other religions). Thus, similar mental operations as in the case of a goal conflict are required to resolve the conflict. Therefore, cognitive conflicts can likewise elicit a conflict mindset leading to higher cognitive flexibility, but evidence suggests that this often works only among people high in epistemic motivation (e.g., Gocłowska et al., Citation2014; Gocłowska & Crisp, Citation2013). This might be the case because a cognitive conflict can only be resolved by people who are willing to invest effort into restructuring the situation and resolving the conflict. While doing so, the relevant processing strategies become activated (Crisp & Turner, Citation2011) and can then carry over to subsequent situations. In sum, also cognitive conflicts can activate a flexibility mindset.

Counterfactual thinking

Counterfactual thoughts (“What if … ?”, “If only … ”) frequently occur in our everyday reasoning, especially in response to negative events (Roese & Epstude, Citation2017). Such thoughts (e.g., “If only I had set my alarm clock at a higher volume, I would have woken up on time”) imply a mental simulation of alternatives to reality. They affect concrete behaviours that would improve an outcome in their context of origin (e.g., increasing the volume of the alarm clock after oversleeping). In addition, they also influence the thoughts and behaviours in subsequent situations unrelated to their cause and, thus, elicit a mindset (e.g., Galinsky & Moskowitz, Citation2000). This counterfactual mindset is based on the mental simulation of alternative realities (i.e., counterfactual thoughts) in one situation. This processing style carries over to the subsequent situation and elicits heightened flexibility.

Counterfactuals can have different structures that might also facilitate different forms of flexibility. Subtractive counterfactuals focus on what would have happened if a certain event had not taken place (“If only I had NOT done X”). They foster relational processing, that is, flexible thinking within the scope of an activated dimension or concept (e.g., ranging from negative to positive evaluations on an activated attitudinal dimension, or from “weak” to “strong” as endpoints of one conceptual dimension). Relational processing contributes to identifying connections between a set of stimuli, to structuring thoughts, and to idea generation around activated concepts or dimensions. It creates flexibility in the sense that connections between concepts are considered and representations are restructured, but this happens within the limits of the activated concepts (“thinking within the box”; Kray et al., Citation2006). In contrast, when generating additive counterfactuals, one mentally simulates the effects of additional events (“If only I had done X”). These thoughts lead to an expansive processing style that is marked by switching between concepts and more creative idea generation (“thinking outside the box”; Markman et al., Citation2007). Thus, both types of counterfactuals elicit (different forms of) a flexibility mindset.

Recalling past creativity

Perhaps the most direct way to activate a flexibility mindset is through self-generated primes. A suitable way to prime such flexible thoughts is through reflecting on instances of one’s own past creativity. The processing strategies one applied during these past instances should become reactivated and carry over to subsequent situations (for evidence, see below). Priming one’s own past creative performance should also elicit a flexibility mindset.

Promotion focus

A final mental state facilitating flexibility is a promotion focus. It elicits similar mental operations and outcomes as the mindsets described before, but is embedded in a different theoretical tradition. Higgins and Higgins (Citation1997) regulatory focus theory distinguishes between two motivational states that elicit different processing styles: a promotion and a prevention focus. A promotion focus is activated when individuals pursue ideals. It results in eager goal striving and a focus on gains, on assuring hits and avoiding errors of omission. In contrast, a prevention focused is activated when individuals focus on duties and obligations. This results in vigilant goal striving, a focus on losses, and the tendency to stay inactive rather than make an error.

Most important for the current context, regulatory focus theory also makes statements about the processing styles in both regulatory foci. Individuals in a promotion focus apply an eager strategy, process information in a cognitively risky fashion (Crowe & Higgins, Citation1997), and are happy to try out new things (Liberman et al., Citation1999). In contrast, people in a prevention focus apply a conservative strategy and follow rules and regulations (Lanaj et al., Citation2012). Consequently, people in a promotion focus show higher flexibility than those in a prevention focus, whereas people in a prevention focus are better prepared for analytical thinking (Crowe & Higgins, Citation1997; Seibt & Förster, Citation2004).

Regulatory focus is often manipulated incidentally and produces effects that carry over to subsequent situations. For example, regulatory focus can be manipulated by asking participants to navigate a mouse through a maze, either with a nurturance goal (getting food) eliciting a promotion focus or with a security goal (not falling prey to a raptor) fostering a prevention focus. This manipulation is a mindset priming manipulation, given that a strategy is activated by showing a certain behaviour. The heightened flexibility introduced by the promotion focus impacts incidental responding in a subsequent task (e.g., more flexible idea generation; Friedman & Förster, Citation2001). Notably, in contrast to the other flexibility mindsets, the activation of a promotion focus does not rely on the consideration of alternatives but on the activation of a motivational state. However, priming a promotion focus (by activating this motivational state) has been shown to facilitate such a consideration of alternatives and more flexible information processing. Thus, although the manipulation itself does not rely on the consideration of alternatives, it activates an information processing style that is in line with our definition of a flexibility mindset above.

Summary

Taken together, goal conflicts, cognitive conflicts (when processed with sufficient epistemic motivation), counterfactual thinking, thoughts about one’s own past creative performance, and a promotion focus can elicit flexibility mindsets. In what follows, we will summarise how the activation of these mindsets helps to prevent or reduce unwanted effects of spontaneous processing in four domains: creative performance, stereotyping and prejudice, interpersonal behaviour, and decision-making. We demonstrate that, in each of these domains, eliciting a flexible processing strategy via mindset priming exerts a debiasing influence.

Flexibility mindsets improve creative performance

Idea generation and creative performance more generally rely on (domain specific) knowledge (e.g., Weisberg, Citation1999), but to be new and original, ideas must go beyond the usual associations activated through prior knowledge (Campbell, Citation1960; Simonton, Citation1999). Thus, creative idea generation requires juggling the tension between prior knowledge and originality (i.e., going beyond this knowledge). In line with this notion, research has repeatedly found that generated ideas rely on typical features of the respective object category (e.g., Rubin et al., Citation1991), features of provided examples (Marsh et al., Citation1996; Smith et al., Citation1993), and unconsciously activated knowledge (Marsh, Bink et al., Citation1999) – in short, domain-specific knowledge. Thus, when generating ideas, the spontaneously activated domain-specific knowledge works against the aim to go beyond the given. In other words, idea generation is one of the cases in which spontaneous tendencies lead to undesired outcomes.

In an effort to identify ways to reduce the limiting impact of spontaneously activated domain-specific knowledge on creative performance, we tested the effect of recalling one’s own past creativity on creative performance and related measures (Sassenberg et al., Citation2017). To this end, we developed a priming procedure in which we asked participants to recall three situations in which they had acted or thought creatively according to their own standards (Sassenberg & Moskowitz, Citation2005). To test the effect of the creativity priming, we compared it to a no priming control condition, a preciseness priming control condition (thinking back to three situations in which people had thought or acted particularly precisely or thoroughly), or both.

To get beyond the influence of spontaneously activated domain-specific knowledge, people would need to rely less on close associations (e.g., light – bright) and more on remote associations (e.g., window – bright). The latter are considered building blocks of flexibility and creative performance (Mednick, Citation1962). Therefore, we tested in a first study whether the processing of close and remote associations could be altered via a mindset priming (Sassenberg et al., Citation2017, Exp. 1).

Participants (N = 43, undergraduate students) were randomly allocated to the creativity priming condition or neutral control condition. Afterwards they performed a lexical decision task with sequential priming with 72 trials. In each trial, first a fixation cross was presented for 400 ms, followed by the prime word (100 ms), which was replaced by the target string. Participants had to indicate whether this string was a word or not. In the 36 critical trials, the target strings were words (e.g., bright) that were either preceded by a remotely (e.g., window) or a closely (e.g., light) associated prime. The same targets were also shown after two unrelated primes which were remotely and closely related to another target – resulting in a relationship type (related vs. unrelated) x association (close vs. remote) within-subjects design in addition to the between-subjects factor mindset priming. We expected faster responses to target words after closely related (vs. unrelated) primes in the control condition, but not in the creativity mindset condition. Conversely, we expected faster responses after remotely associated primes (vs. unrelated primes) in the creativity mindset condition, but not in the control condition.

In line with this prediction, a marginalFootnote1 interaction of mindset and relationship type emerged for close associations, and a significant interaction for remote associations. For close associations, response times to target words after related primes were descriptively shorter than after unrelated primes in the control condition, but not in the creativity condition (for descriptive statistics, see ). Despite this interaction being only marginal, additional research reported in the next section (Sassenberg & Moskowitz, Citation2005) as well as one unpublished study provided evidence for this effect (the unpublished study for closely related synonyms and antonyms). Such findings suggest that creativity mindsets may reduce the activation of typical associations. More critically to our concerns were the ability of the mindsets to make cognition more flexible by priming remote associations. The significant mindset by relationship type interaction provides evidence to support this prediction. Participants responded faster to the target words after remotely related primes than after unrelated primes in the creativity condition but not in the control condition (see ). In sum, these results indicate that remote associations are more strongly activated, and close associations are less strongly activated after recalling past creative performance than in a control condition – providing evidence that the creativity priming helps to overcome spontaneous responses.

Table 1. Means (standard deviations) of response times and relative frequency of word endings not copying the provided examples from Experiments 1, 2a and 2b of Sassenberg et al. (Citation2017)

Two subsequent studies tested whether the same creativity priming also helps one to rely less on spontaneously activated domain-specific knowledge in the context of idea generation (Sassenberg et al., Citation2017, Exp. 2a & 2b; N = 46 & 72, undergraduate students). These experiments compared creativity priming and preciseness priming to a no priming control condition. After the priming, we assessed the main dependent variable in a task that had been developed to show that people rely on spontaneously activated domain-specific knowledge in idea generation and how this undermines creativity (Marsh, Ward et al., Citation1999). In this idea generation task, participants are requested to generate potential new names for exemplars of a given category, for instance, a new type of pasta. As part of the task instruction, participants receive six examples for each category that are highly prototypical for the category (e.g., Lasagne, Spaghetti, Rigatoni etc.). The examples all share two endings (here: “-i” or “-ne”). Participants are instructed to be as creative as possible and not to copy the examples or any of their features. Earlier research has used this task to demonstrate how spontaneously activated knowledge – here the typical word endings provided in the examples – limits creativity in idea generation (Kray et al., Citation2006; Marsh et al., Citation1996; Marsh, Ward et al., Citation1999). When participants violate the instructions and generate ideas copying provided word endings, this most likely results from the spontaneous and unintended use of these typical category features, which counteracts participants’ intentional striving for creative and original ideas. If the creativity priming indeed helps to avoid limitations resulting from spontaneous processing, it should (compared to the other two conditions) lead to more ideas not ending with the same letters as the examples (range of values 0 to 1). We tested this prediction with both native speakers of the German and the English languages in Germany and the US, respectively. Both studies provided evidence for the hypothesis, with significant decreases in copying in the creativity condition: After creativity priming, more of the generated words did not contain word endings copied from the examples than after preciseness priming. This same pattern was seen in comparisons between creativity priming and the no priming condition (see ).

Experiment 3 (Sassenberg et al., Citation2017) tested the effect of the creativity priming (vs. a preciseness priming) on the Remote Associates Test (RAT; Mednick, Citation1962) in a sample of N = 74 undergraduate students. In each trial of this task participants are requested to indicate what what three words have in common (e.g., belly, barrel, garden – correct response: beer). Values range between 0 and 20; higher values indicate more correct solutions (i.e., higher creativity). In line with our expectation, participants in the creativity priming condition found more correct solutions (M = 9.65, SD = 2.49) than those in the preciseness priming condition (M = 8.14, SD = 3.22).

Similar effects of improving creative performance via increased cognitive flexibility were also reported using other mindset priming procedures. For instance, information that describes a stereotype violation (i.e., a cognitive conflict) triggers such flexibility. Gocłowska and Crisp (Citation2013) found that participants high in epistemic motivation generated a greater number of different categories to which ideas belonged when in the counter-stereotype (i.e., conflict) condition. Additional studies demonstrate that this pattern also holds when cognitive conflicts are induced via schema violations more generally (e.g., a picture of a priest standing in front of a mosque; Gocłowska et al., Citation2014).

Furthermore, an additive but not a subtractive counterfactual mindset has been found to be suitable to overcome activated domain-specific knowledge when generating novel uses for a brick (Markman et al., Citation2007). This provides evidence that additive but not subtractive counterfactuals elicit expansive processing (i.e., thinking outside the box). On the contrary, subtractive but not additive counterfactuals lead to better performance in the RAT (Kray et al., Citation2006; Markman et al., Citation2007). Thus, subtractive but not additive counterfactuals lead to relational processing. This research demonstrates that both additive and subtractive counterfactuals can positively impact (different types of) creative performance, but due to different processing styles or types of flexibility.

Finally, a promotion focus (compared to a prevention focus) can lead to the generation of more (and more creative) ideas. Evidence that a promotion focus helps to overcome spontaneous responses comes from a study using a word stem completion task. This task provides participants with a word fragment with missing letters and one possible word that could be generated from it (e.g., _and → hand). Participants are to find a second solution (e.g., band) and, thus, need to avoid the provided solution that easily comes to mind. Those who were primed with a promotion (vs. prevention) focus performed better on this task and, thus, showed higher creativity (Friedman & Förster, Citation2001).

In sum, spontaneous responses that hinder creative performance (here: spontaneously activated domain-specific knowledge and features of provided examples) can be reduced by the activation of various flexibility mindsets. These mindsets are characterised by a processing style in which dominant (close) associations are relatively less accessible and secondary (remote) associations come to mind more easily, whereby mental flexibility and creative performance are increased. The observation that a creativity priming, cognitive conflicts, counterfactual thinking, and a promotion focus have all been demonstrated to increase (different forms of) flexibility in idea generation validates the idea that these induce flexibility mindsets. The reviewed evidence also suggests that mindset priming has the potential to circumvent unwanted effects of spontaneous information processing. The following sections will provide additional evidence for this effect in different social contexts.

Flexibility mindsets reduce stereotyping and prejudice

Spontaneous processing can have undesired consequences in person perception because it may contribute to stereotyping and prejudice. The common assumption is that stereotypes are automatically activated as a consequence of automatic social categorisation of individuals and that they result in biased judgements and behaviour (Wittenbrink et al., Citation2019). Thus, person perception and intergroup relations are another domain where spontaneous processing may lead to undesirable outcomes. In four sets of studies, we demonstrated that several flexibility mindsets help to reduce biases caused by stereotypes and prejudice. First, we present evidence that priming creativity reduces stereotype activation. Afterwards, we provide evidence that flexibility mindsets activated by eliciting cognitive conflicts or subtractive counterfactuals mitigate strong attitudes towards outgroups – and, thereby, help to overcome the socially undesirable outcomes spontaneous processing may entail.

Priming creativity reduces automatic stereotype activation

In a first set of studies, we investigated whether spontaneous stereotype activation can be reduced when people think back to their past creative performance (vs. about past, precise performance, labelled thoughtful mindset in the article; Sassenberg & Moskowitz, Citation2005). In Experiment 1 (N = 38, undergraduate students), we measured stereotype activation in a lexical decision task with sequential priming. Each trial started with the presentation of a fixation cross for 750 ms, followed by a prime displayed for 80 ms. The target letter-string appeared after another 15 ms. The task consisted of 140 trials of which 56 were critical to our analysis. Within the critical trials, the target letter-strings were words that were either (a) stereotypic in that they were related to stereotypes about African-Americans (e.g., aggressive, athletic), (b) positive control words (e.g., kind, helpful), or (c) negative control words (e.g., selfish, weak). Each word appeared twice, once preceded by an African American face and once by a European-American face as a prime. Evidence for spontaneous stereotype activation would be provided by faster reactions to stereotypic target words after African American primes than after European American primes (no such facilitation should be found for control words). We expected that the creativity mindset would weaken this facilitation effect.

In line with our prediction, we found slower reaction times on stereotypic targets following the African American primes in the creativity mindset than in the thoughtfulness condition (see ). Reaction times on the control targets did not differ between conditions. Thus, the spontaneous activation of the African American stereotype in response to seeing a member of this group was weaker when the creativity mindset was activated.

Table 2. Means (standard deviations) of response times from Experiments 1, 2a and 2b of Sassenberg and Moskowitz (Citation2005)

The remaining two studies showed that this pattern also held for non-social category associations and when including a neutral control condition in which no mindset was induced (Sassenberg & Moskowitz, Citation2005; Exp. 2a & 2b, total N = 48, undergraduate students). In Experiment 2a, no mindset priming preceded the lexical decision task with sequential priming. Starting with a fixation cross for 400 ms, participants subsequently saw a prime word for 50 ms, which was then replaced by the target string. Each of the six target words (e.g., sweet) was preceded twice by a semantically related prime (e.g., sugar) and twice by an unrelated prime (e.g., plate). The procedure of Experiment 2b was identical but contained the mindset manipulation prior to the lexical decision task. Experiment 2a established the baseline effect that reaction times on targets were faster when the target followed semantically related primes compared to unrelated primes. Experiment 2b replicated this pattern for the thoughtfulness priming condition. Crucial to our hypothesis, however, the difference between semantically related and unrelated primes (see ) disappeared after the creativity mindset priming. Thus, activating the creativity mindset not only reduces spontaneous stereotypic associations, but also dominant associations between semantically related concepts in general. It remains an open question for future research whether the effect described here and in the preceding section (i.e., Study 1, Sassenberg et al., Citation2017) results from changed activation or inhibition of one type of associations or other processes.

Taken together, these findings suggest that recalling past creativity activates a flexibility mindset that reduces spontaneous processing (here: automatic stereotype activation). In the following two sections, we report research demonstrating the reduction of people’s spontaneous prejudiced tendencies when judging outgroups through two further procedures that activate flexibility mindsets: cognitive conflicts and subtractive counterfactuals.

Cognitive conflicts reduce the impact of dominant outgroup attitudes

Across six experiments, we investigated whether cognitive conflicts caused by messages with negations (e.g., “Asylum seekers are not lazy”) reduces the impact of dominant outgroup attitudes on outgroup judgements and whether an increase in cognitive flexibility would explain this effect (Winter et al., Citation2021a). In general, processing negations (e.g., “the door is not closed”) requires a two-step mental simulation of conflicting alternatives (Kaup et al., Citation2007). Recipients of such a message mentally represent the negated term (“closed”) in the first place and then derive the actual meaning of the phrase (“not closed” or “open”) in a second processing step. In contrast, processing affirmations (e.g., “the door is open”) does not require these two steps because the meaning is directly retrieved. The mental operation that is necessary to process negations resembles that of resolving a cognitive conflict (Dudschig & Kaup, Citation2018). Given that cognitive conflicts are known facilitators of cognitive flexibility (Kleiman & Enisman, Citation2018), we hypothesised that reading messages with negations increases cognitive flexibility and, in turn, causes judgements that are less in line with participants’ dominant attitudes towards the mentioned outgroup (compared to conditions with affirmations or no messages). In most studies, we were interested in attitudes towards marginalised outgroups such as immigrants or homeless people. These groups are often automatically stereotyped as low in (social) warmth including low trustworthiness (e.g., Cuddy et al., Citation2008). Thus, we deemed the perceived outgroup trustworthiness as an appropriate attitudinal dimension for our aim to reduce biases that arise from spontaneous processing.

Importantly, dominant outgroup attitudes are not necessarily prejudiced. Rather, people differ in their levels of stereotyping and prejudice as do their dominant responses towards an outgroup. To account for this, we included individual differences measures (e.g., initial outgroup attitude or political orientation) in some of our studies. In the following sections, we present studies testing whether flexibility mindsets reduce the relationship between pre-manipulation dominant outgroup attitudes and post-manipulation outgroup attitudes (rather than on absolute levels of prejudice).

Studies 1 and 2 (Winter et al., Citation2021a; N = 141 and 146 undergraduate students) examined the effectiveness of negations in reducing the impact of dominant outgroup attitudes on subsequent outgroup judgements. In both studies, we first measured participants’ initial trust in a specific outgroup (among several filler groups). Then, in two conditions, participants received messages that spoke in favour of the outgroup’s trustworthiness (Study 1: asylum seekers; Study 2: homeless people). The messages contained either negations (e.g., “they are not deceptive”) or affirmations (e.g., “they are reliable”). In a third condition, no messages were provided (control condition). Finally, participants rated outgroup trust on twelve items from established measures of trust (Dhont & van Hiel, Citation2011; Mayer et al., Citation1995; Noor et al., Citation2008).

As predicted, messages with negations (Study 1: B = 0.29, SE = 0.08; Study 2: B = 0.14, SE = 0.07) diminished the relation between initial and post-message outgroup trust, compared to affirmations (Study 1: B = 0.57, SE = 0.09; Study 2: B = 0.53, SE = 0.08) and the control condition (Study 1: B = 0.48, SE = 0.09; Study 2: B = 0.53, SE = 0.07; see ). These findings provided evidence that cognitive conflicts, induced via messages with negations, can cause outgroup judgements that are less in line with participants’ dominant attitude (i.e., their spontaneous tendency to judge the group).

Figure 1. Outgroup trust as a function of message type (negations vs. affirmations vs. control) and initial outgroup trust. Shaded areas represent the 1 standard error margin. The solid vertical line represents the sample mean of initial outgroup trust; the dotted vertical lines mark one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively. Reproduction of from Winter et al. (Citation2021a).

Figure 2. (a) Regression weights for the impact of messages with negations (vs. affirmations and no messages) on outgroup trust depending on initial outgroup trust via cognitive flexibility. (b) Outgroup trust as a function of message type (negations vs. affirmations vs. control) and initial outgroup trust. Shaded areas represent the 1 standard error margin. The solid vertical line represents the sample mean of initial outgroup trust; the dotted vertical lines mark one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively. Reproduction of Figure 6 from Winter et al. (Citation2021a). (c) Outgroup trust as a function of cognitive flexibility and initial outgroup trust. Shaded areas represent the 1 standard error margin. The solid vertical line represents the sample mean of initial outgroup trust; the dotted vertical lines mark one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively.

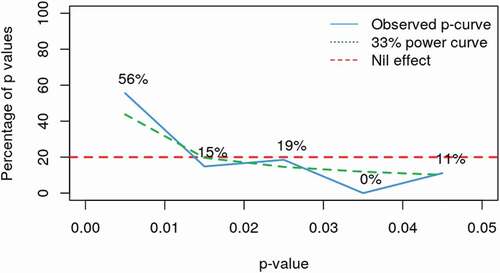

Figure 3. Means and standard errors for reaction times on trials with same or different colours in the physical matching task grouped by experimental condition. Smaller difference between bars indicate higher flexibility.

In three more studies, we examined the mediating role of cognitive flexibility. Studies 3a and 3b implemented the causal chain approach to examine the two paths of the assumed process separately. In Study 4, we tested the whole moderated mediation. In Study 3a (Winter et al., Citation2021a; N = 234, undergraduate students), we investigated whether messages with negations would increase cognitive flexibility (i.e., the first part of the proposed mechanism). To do so, we presented participants the messages from Studies 1 and 2 that contained either negations or affirmations (plus the no message control condition). Then, cognitive flexibility was assessed with a categorisation task (Rosch, Citation1975) in which participants evaluated the fit of several objects to a given category (e.g., car – vehicles). Higher ratings of category fit for items low in prototypicality (e.g., feet) signify greater category inclusiveness and, thus, higher cognitive flexibility (indicated by less negative values, as responses were z-standardised within participants). As predicted, after reading negations (M = −0.84, SD = 0.15), participants showed greater category inclusiveness (i.e., cognitive flexibility) than after reading affirmations (M = −0.88, SD = 0.14) or no messages (M = −0.91, SD = 0.13); the latter two did not differ. Thus, we demonstrated for the first time that messages with negations increase cognitive flexibility.

Study 3b (Winter et al., Citation2021a; N = 232, undergraduate students) was designed to test the second path of the mechanism, that is, whether increasing cognitive flexibility (without providing any information about the target outgroup) weakens the relationship between initial outgroup trust and post-manipulation outgroup trust. To induce a flexibility mindset, we let participants generate five stereotype-inconsistent category combinations (adapting the procedure of Vasiljevic et al., Citation2013). In this cognitive flexibility condition, participants are asked to combine two categories that intuitively do not fit together well (e.g., “female” and “mechanic”). As those new combinations involve schema-violations, they confront participants with cognitive conflicts. Participants in the control condition were asked to generate stereotype-consistent category combinations (e.g., “male” and “mechanic”). As in Studies 1 and 2, we measured initial outgroup trust (in asylum seekers) at the outset of the study, and post-manipulation outgroup trust. As predicted, we found the association between initial outgroup trust and post-manipulation outgroup trust to be weaker in the cognitive flexibility condition (B = 0.43, SE = 0.07) than the control condition (B = 0.63, SE = 0.06). Thus, our results support the second part of the mechanism: Inducing a cognitive flexibility mindset reduces judgements that are in line with the dominant outgroup attitude.

Study 4 (Winter et al., Citation2021a; N = 206 undergraduate students) sought to test the whole moderated mediation in one study. The procedure was similar to Study 1, but included an assessment of cognitive flexibility between the messages and the outgroup trust measure. For this purpose, we developed a contextualised measure of cognitive flexibility that maintains the basic properties of the categorisation task applied earlier (Rosch, Citation1975), but does not require switching contexts. In this task, participants rated 18 persons (based on descriptions with a photograph and some general demographic information, like country of origin or religion) regarding these persons’ fit to the (social) category of asylum seekers. We calculated the cognitive flexibility score by averaging the ratings of the six persons who, overall, achieved the lowest category fit ratings and z-standardised the resulting index within subjects. We hypothesised that messages with negations (vs. affirmations and no messages) would weaken the relation between initial outgroup trust and post-message outgroup trust due to increased cognitive flexibility. The results of Study 4 clearly supported this moderated mediation (). First, replicating the results of Studies 1 and 2, messages with negations (B = 0.53, SE = 0.07) weakened the relation between initial outgroup trust (in asylum seekers) and outgroup trust after the messages, compared to messages with affirmations (B = 0.78, SE = 0.07) and no messages (B = 0.70, SE = 0.07). Providing evidence for the first path of the mediation, messages with negations increased cognitive flexibility (M = −0.84, SD = 0.30) compared to affirmations (M = −0.97, SD = 0.20) and no messages (M = −0.93, SD = 0.30). Completing the moderated mediation, higher cognitive flexibility (+1SD; B = 0.52, SE = 0.06) reduced outgroup judgements in line with the dominant outgroup attitude compared to lower cognitive flexibility (−1SD; B = 0.78, SE = 0.05). Thus, Study 4 compellingly demonstrated that cognitive flexibility drives the tempering effect of messages with negations on outgroup attitudes.

In Study 5 (Winter et al., Citation2021a; N = 301, undergraduate students), we aimed to generalise the effects of negations to negative outgroup communication and to an attitude different from trust. In this study, we presented messages that argued against the warmth (in the sense of the Stereotype Content Model, Cuddy et al., Citation2008) of doctors. As predicted, negations lead participants to judge the outgroup less in line with their dominant attitude compared to affirmations and no messages, which suggests that the effects of negations can be generalised to negative outgroup communication and outgroup attitudes beyond trust.

Overall, this line of research demonstrates that the spontaneous tendency to judge outgroups in line with one’s dominant attitudes is reduced when a cognitive conflict is activated via messages with negations (vs. affirmations or no message) due to enhanced cognitive flexibility (Winter et al., Citation2021a). Accordingly, negations can be used as a very subtle induction of cognitive conflicts to activate a flexibility mindset. In line with our theorising, this subtle induction of cognitive conflicts does, in turn, reduce the impact of prejudiced outgroup attitudes that result from spontaneous processing.

Paradoxical leading questions reduce negative outgroup attitudes (and increase flexibility)

Previous research found another, less subtle way of inducing cognitive conflicts via communication to reduce the impact of dominant attitudes in intergroup conflicts: so-called paradoxical thinking interventions (for an overview, see Hameiri et al., Citation2019). Different from conventional interventions using stereotype-inconsistent communication (e.g., Weber & Crocker, Citation1983), the messages conveyed through paradoxical interventions are in principle consistent with the recipients’ beliefs but amplify and exaggerate these – sometimes even in an absurd form. For instance, Hameiri et al. (Citation2018) asked hawkish Israeli participants questions like “Why do you think that the real and only goal the Palestinians have in mind is to annihilate us, in a manner that transcends their basic needs such as food and health?” Paradoxical interventions of this type reduced dominant anti-outgroup beliefs and actions in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, especially among those with initially more hostile attitudes towards the opposing party (Hameiri et al., Citation2019, Citation2018). The paradoxical effect of these interventions, thus, lies in their capacity to move recipients beyond central, socially shared, and dominant beliefs – the so-called ethos of conflict (Bar-Tal et al., Citation2012) – by addressing and exaggerating exactly these beliefs.

In sum, prior work has demonstrated that paradoxical leading questions reduce the impact of (spontaneous) biased judgements and behaviours among prejudiced people. However, it has provided little insight into the underlying (cognitive) processes. We assume that the processes elicited by paradoxical leading questions are similar to those elicited by negations discussed in the preceding section – namely, heightened cognitive flexibility due to a cognitive conflict. To be more precise, the paradoxical interventions make previously held beliefs seem irrational (Hameiri et al., Citation2019) and might, thus, cause a cognitive conflict. Given that cognitive conflicts are precursors of cognitive flexibility (Kleiman & Enisman, Citation2018), we examined whether paradoxical leading questions enhance cognitive flexibility.

In two studies, we adapted the paradoxical leading questions used by Hameiri et al. (Citation2018) to the context of anti-refugee sentiments among German citizens (Knab et al., Citation2021). Questions like “Why do you think that Christmas will be abolished within the next few years due to the increase in refugees?” are in line with the right-wing view that refugees undermine German culture but reflect a very extreme manifestation of this position. In the conventional condition, participants responded to questions that were inconsistent with an anti-refugee attitude (e.g., “Why do you think that we will continue to celebrate Christmas even though we do have an increase in refugees?”). In the control condition, the questions did not target a particular attitude towards refugees (e.g., “Do you think that the meaning of Christmas will change in the next years due to the increase in refugees?”). Political orientation was assessed as moderating variable with one item asking participants for self-placement on a 7-point scale (from 1 = left to 7 = right; e.g., Hameiri et al., Citation2018). In both studies, we measured cognitive flexibility with the categorisation task described in Study 3 of the article described above(Winter et al., Citation2021a). We predicted that paradoxical (anti-refugee) leading questions would increase cognitive flexibility among participants with a more right-wing political orientation because for them, these questions exaggerate existing beliefs (which is not the case for left-wing participants).

In Study 1 (N = 116, sample from the general German population), we observed the predicted interaction effect of experimental condition and political orientation on cognitive flexibility (Knab et al., Citation2021). Among self-identified politically right-wing participants (+1 SD), paradoxical questions (M = −0.73) increased cognitive flexibility compared to asking questions that were attitude-inconsistent (M = −0.85) or neutral (M = −0.95). For the politically left (−1 SD), no difference between conditions emerged. We aimed to replicate this finding in Study 2 (Knab et al., Citation2021; N = 190 participants from the general German population pre-screened for their political party preference, recruited via clickworker) using the same procedure, but only comparing paradoxical and conventional leading questions. Paradoxical questions (M = −0.80, SD = 0.25) enhanced cognitive flexibility compared to conventional questions (M = −0.87, SD = 0.17). However, this effect did not interact with political orientation, but (marginally) with the party participants reported to support. Among supporters of the German right-wing party AfD, paradoxical questions (M = −0.71, SD = 0.27) led to higher cognitive flexibility than conventional questions (M = −0.84, SD = 0.21). This was not true among supporters of other parties and non-voters (paradoxical: M = −0.88, SD = 0.20; conventional: M = −0.90, SD = 0.14).

Overall, these findings show that paradoxical leading questions that target anti-refugee attitudes enhance cognitive flexibility among adherents of the political right. Thus, cognitive flexibility might contribute to paradoxical interventions’ tempering influence on extreme conflict-related attitudes and behaviours (i.e., spontaneous intergroup biases) that has been repeatedly demonstrated elsewhere. Taken together, our own research shows that cognitive conflicts – either subtly induced via negations or more blatantly via paradoxical questions – are suitable means to reduce the impact of dominant (i.e., prejudiced) attitudes in the intergroup context that result from spontaneous processing.

Subtractive counterfactuals reduce the impact of dominant outgroup attitudes

As outlined above, a subtractive counterfactual mindset induces a relational processing style (Markman et al., Citation2007). These thoughts instigate a comparison between the dominant response and more remote alternatives within an activated concept (e.g., an attitudinal dimension). Thus, activating a flexibility mindset via subtractive counterfactuals should reduce the impact of dominant beliefs (i.e., prejudice) about an outgroup which would otherwise spontaneously colour the outgroup judgment. In contrast, additive counterfactuals induce an expansive processing style which facilitates switching between concepts (e.g., different attitudinal dimensions), but not changes within an activated concept. We, thus, predicted that subtractive, but not additive counterfactuals would lead participants to judge immigrants less in line with their dominant attitude towards this outgroup (Winter et al., Citation2021b).

In Study 1, 174 participants recruited at a German university read segments of an original political speech that was directed to the German population and covered recently committed Islamist terror attacks and the broader topic of refugee integration. Participants in the control condition only read the original speech. In the subtractive counterfactuals condition, we added rhetorical questions intended to induce subtractive counterfactuals (e.g., “But would not perhaps much less have happened, if we had not been so gullible?”) after each paragraph. Participants’ political orientation was assessed (from 1 = left to 7 = right) to capture their dominant outgroup-related beliefs – as the political right is associated with high levels of outgroup prejudice (e.g., Duckitt, Citation2001). The perceived trustworthiness of asylum seekers (Mayer et al., Citation1995) served as the dependent variable as low trustworthiness is often associated with immigrants (Cuddy et al., Citation2008).

Mirroring participants’ dominant outgroup attitudes, a more right-wing political orientation predicted lower perceived trustworthiness of asylum seekers in the control condition (B = −0.59, SE = 0.07). Supporting our prediction, this relation was weaker after reading the speech that contained subtractive counterfactual questions (B = −0.38, SE = 0.08). Hence, this result is in line with the idea that a flexibility mindset (here activated via subtractive counterfactual questions in another person’s political speech) reduces the impact of dominant attitudes on outgroup judgements. Since the manipulation used herein was novel, we deemed it necessary to validate it in an additional sample (Winter at al., Citation2021b; N = 87, undergraduate students). We demonstrated that the speech containing subtractive counterfactual questions indeed elicited a higher degree of mental simulation among recipients than the original speech. This finding validated that subtractive counterfactual questions, voiced by someone else in a political speech, actually elicit similar thoughts (i.e., mentally simulating conflicting alternatives) as a direct mindset priming manipulation.

Studies 2a to 2d (Winter et al., Citation2021b) served to demonstrate that the effect from Study 1 was indeed caused by subtractive counterfactuals, and that additive counterfactuals would not have the same effect. To this end, we included a second control condition in which participants generated additive counterfactuals. In Studies 2a, 2b, and 2d, we used a classical mindset priming procedure. Participants recalled a negative personal event and simulated possibilities how the outcome could have been better (Markman et al., Citation2007). Depending on experimental condition, participants were asked to generate either subtractive (“If only I had NOT … ”) or additive (“If only I had … ”) counterfactuals as responses to the task. Participants in the control condition immediately worked on the dependent measure without recalling any negative experiences. In Study 2 c, we used the manipulation from Study 1 (i.e., the political speech) but added a second control condition with additive counterfactual questions (e.g., “But would not perhaps much more have happened, if we had treated those who sought protection with hatred?”). As in Study 1, we assessed political orientation as predictor of dominant outgroup attitudes. Perceived outgroup trustworthiness (Studies 2a, 2 c, and 2d conducted among 732 German undergraduate students: asylum seekers in Germany; Study 2b with 283 British undergraduate students recruited via prolific academic: labour migrants in the UK) served as the dependent variable. We predicted that subtractive counterfactuals would reduce the relation between political orientation and perceived outgroup trustworthiness compared to additive counterfactuals and the control condition. In an analysis across Studies 2a to 2d, we found that subtractive counterfactuals (B = −0.31, SE = 0.04) weakened the relation between political orientation and outgroup trustworthiness compared to both the additive counterfactuals condition (B = −0.45, SE = 0.04) and a neutral control condition (B = −0.54, SE = 0.04); the latter two did not differ. Accordingly, participants in the subtractive counterfactuals condition followed their spontaneous biases less when judging immigrants. Hence, the activation of a flexibility mindset via inducing subtractive (but not additive) counterfactual thoughts and, thus, relational (but not an expansive) processing reduced the impact of dominant attitudes on outgroup judgements.

Summary

The research reviewed in this section demonstrates that activating a flexibility mindset reduces those biases that people would show when following their spontaneous tendencies in the intergroup context (i.e., stereotype activation and prejudiced judgements). Flexibility mindsets can be activated via various means – be it by reminding people of their past creative performance, by eliciting cognitive conflicts via negations or paradoxical leading questions, or by inducing subtractive counterfactual thoughts. Importantly, all of these mindset-inductions were successful in counteracting spontaneous response tendencies in the intergroup domain.

First, we showed that creativity priming reduces automatic stereotype activation (Sassenberg & Moskowitz, Citation2005). Second, we demonstrated that the induction of cognitive conflicts – via subtle means such as the use of negations (Winter et al., Citation2021a), but also more overt means like the combination of stereotype-inconsistent categories (see also Vasiljevic et al., Citation2013) reduce the impact of dominant outgroup attitudes. In addition, we showed that paradoxical leading questions – an intervention proven to reduce dominant attitudes in intergroup conflicts – increased cognitive flexibility among recipients with anti-refugee attitudes (Knab et al., Citation2021). These results add to previous research that has repeatedly shown that stereotyping and dominant outgroup judgements can be reduced by activating a conflict mindset (Kleiman et al., Citation2014, Citation2016). We would like to highlight that other researchers have found evidence for the role of cognitive conflicts in avoidance of stereotyping using methods from neuroscience (e.g., Amodio, Citation2014) – but a detailed discussion of this approach is beyond the scope of the current article.

Third, we found that subtractive (but not additive) counterfactuals reduced the impact of participants’ prejudice on outgroup judgements (Winter et al., Citation2021b), supporting our prediction that a relational processing style activated by subtractive counterfactuals (but not the expansive processing style elicited by additive counterfactuals) mitigates dominant responses on a given dimension (i.e., an outgroup stereotype). In another article not directly testing the current research question, we showed that reducing flexibility by priming competition increases rather than reduces biased judgements about outgroups, providing evidence for the flipside of the effect (Sassenberg et al., Citation2007).

Taken together, research in the domain of stereotyping and prejudice clearly supports our idea that flexibility mindsets reduce the detrimental impact of spontaneous processing. The positive effects of flexibility mindsets also extend to interpersonal behaviour.

A flexibility mindset reduces biases in interpersonal behaviour

Spontaneous processing also leads to undesired outcomes in the domain of interpersonal behaviour. In interpersonal competition, for instance, people tend to avoid sharing information with others and show less prosocial behaviour than in situations involving cooperation (e.g., Pierce et al., Citation2013; Steinel et al., Citation2010). While such behaviour might be functional during the competition itself, it could, in the long run, harm the relationship between the involved parties. Thus, the interpersonal behaviours that are spontaneously shown in competitive situations can be unethical and have detrimental effects on social relationships. We investigated what happens in situations which are not only characterised by the necessity to compete, but simultaneously to cooperate with the same people. This interdependence structure, called co-opetition (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, Citation2011), implies a goal conflict between cooperating and competing. It should, thus, have the capacity to activate a flexibility mindset and to debias interpersonal behaviour in competitive situations. Spontaneous behavioural biases emerging from competition should be reduced when a situation involves co-opetition (e.g., when several members of a work group compete for a promotion while cooperating on a joint project). In these situations, people are confronted with demands related to different goals: they need to show both competitive (e.g., outperforming others) and cooperative behaviour (e.g., sharing important information). As indicated before, goal conflicts induce flexibility (Kleiman & Enisman, Citation2018). Thus, although co-opetition includes competitive demands that have been shown to reduce prosocial behaviour in unrelated situations, no such transfer effects should occur in the case of co-opetition – because the latter is assumed to activate a flexibility mindset. Accordingly, we predicted that co-opetition would (a) elicit a goal conflict (cooperate vs. compete) and, therefore, promote cognitive flexibility, and (b) reduce spontaneous behavioural responses characteristic of competition (i.e., less information sharing; Landkammer & Sassenberg, Citation2016).

In the preliminary study in this article, we confirmed the negative effects of competition on interpersonal behaviour. Fifty-two undergraduate students imagined a scenario (surviving a plane crash) in which their survival was either negatively dependent on (competition condition), positively dependent on (cooperation condition), or independent of (control condition) others. In a subsequent unrelated task, participants played an information pooling game (adapted from Steinel et al., Citation2010). Participants primed with competition distorted more important pieces of information before sharing it with others than those primed with cooperation and those in the control condition (for descriptive statistics, see ). Thus, competition did indeed lead to a spontaneous bias. Subsequently, we tested whether co-opetition (and the resulting goal conflict) would reduce this bias.

Table 3. Means (standard deviations) for number of distorted pieces of information and cognitive flexibility score from Preliminary Study, Study 1 a & b, Study 2, and Study 4 of Landkammer and Sassenberg (Citation2016)

In Studies 1a and 1b (Landkammer & Sassenberg, Citation2016, total N = 122, undergraduate students), we replaced the control condition from the preliminary study with a co-opetition mindset condition to test whether this would reduce deception (the sharing of distorted information) compared to the competition condition. To prime co-opetition, participants in Study 1a learned that in order to survive after a plane crash, they needed to collaborate with the other survivors (to recover supplies), but that too few supplies were available for all of them to survive. Competition and cooperation were primed as in the Preliminary Study. In Study 1b, we directly manipulated whether participants’ chance to receive a bonus was (positively and/or negatively) dependent on another (ostensible) participant. Crucially, in the co-opetition condition, both positive and negative interdependence were present simultaneously; participants here had to perform well as a team to get any bonus but were informed that only the best-performing team member would receive the bonus in the end. Afterwards, they played an unrelated information pooling game similar to the Preliminary Study. Participants primed with competition distorted more information than participants primed with co-opetition or cooperation across both studies (see ). Thus, co-opetition did reduce the spontaneous bias in interpersonal behaviour that resulted from mere competition.

Study 2 served to test whether conflicting demands (present in co-opetition) indeed accounted for this effect. To this end, we manipulated competition (yes vs. no) independent of conflicting demands (present vs. absent). Participants (N = 286 people recruited via Amazon MTurk) imagined being in the desert for some days as a part of a TV show. Their aim was to reach the closest ranch. Participants learned that their goal was to get closer to the ranch than their competitors in the competitive conditions. Participants in the control conditions were on their own and their goal was to get as close as possible to the ranch. To manipulate conflicting demands orthogonally, participants either received the advice to carefully plan their journey (i.e., non-conflicting) or that carrying more items would give them an advantage for survival, but was also more exhausting due to the conditions in the desert (i.e., conflicting). The same information pooling game as in Studies 1a and 1b served as the dependent variable. As expected, participants in the competition/nonconflicting condition distorted more information than in the other three conditions, which did not differ from each other (see ). This finding supports the idea that only pure competition without conflicting demands leads to deceiving uninvolved others, a tendency reduced as soon as conflicting demands (such as in co-opetition situations) are present.

Finally, we examined whether increased cognitive flexibility accounts for this debiasing effect of co-opetition. We predicted that co-opetition would increase cognitive flexibility, compared to both competition and cooperation. Studies 3a and 3b (Landkammer & Sassenberg, Citation2016; total N = 185, undergraduate students) implemented the same manipulation for task interdependence as Study 1a (the plane crash scenario). However, we included an additional intergroup competition condition. This condition contained cooperative (i.e., within the ingroup) and competitive (i.e., towards the outgroup) elements. In contrast to the co-opetition condition, these two elements were not directed towards the same target and should, thus, not elicit a goal conflict. As a measure of flexibility, we used a physical matching task. Participants indicated whether two stimuli were identical in colour. People usually respond faster to “same” than to “different” colours – a phenomenon known as the fast-same effect and representing a rigid response tendency (Bamber, Citation1969). Accordingly, a smaller fast same effect signifies flexible responding. Across Studies 3a and 3b, results confirmed that co-opetition reduced the fast-same effect compared to cooperation, interpersonal competition, and intergroup competition (the three remaining conditions did not differ; ).

Study 4 (Landkammer & Sassenberg, Citation2016; N = 122; recruited via Amazon MTurk) replicated these results with another indicator of cognitive flexibility: the variation of categories used in an idea generation task (higher values indicate more flexibility). As predicted, the variation (i.e., cognitive flexibility) was higher in the co-opetition than in the remaining conditions, which did not differ (see ). Thus, the conflicting demands inherent in co-opetition did instigate a flexibility mindset.

Taken together, this research shows that being in a co-opetition (i.e., simultaneously competing and cooperating with the same others) comes with conflicting demands. Such a goal conflict activates a flexibility mindset and, in turn, people are less likely to show undesired spontaneous effects that are usually associated with competition. Thus, co-opetition reduces unethical behaviour, such as distorting information shared in interpersonal interactions that results from spontaneous processing in response to competition.

Flexibility mindsets debias decision-making

A final domain in which spontaneous responses that work against human performance are studied is decision-making. People often stick with decisions or projects they have made substantial past investments in – despite of repeated indications that further investments will not lead to the desired outcome (Arkes & Blumer, Citation1985). In the case of this so-called sunk cost effect, sticking with a past decision spontaneously feels right but prevents optimal decisions. In addition, people tend to – unintentionally – show a confirmation bias after having formed an initial opinion. They judge the validity of new information in a way biased by its fit to their already formed opinion; confirming information is seen as more relevant and interesting than contradicting information (Nickerson, Citation1998).

The confirmation bias substantially contributes to low group decision quality in so-called hidden profile tasks (Stasser & Titus, Citation1985). In a hidden profile task, information is distributed between group members in such a way that each group members should, based on the information they received before a group discussion, initially favour a suboptimal decision. Only considering the entirety of information available to the whole group would allow for identifying the optimal decision. When individuals form an initial opinion about the decision at hand before coming together in a group, they often fail to identify the best solution (even though they could, based on the information available to the whole group) – due to the confirmation bias (Greitemeyer & Schulz-Hardt, Citation2003).

In both cases – the sunk cost effect and the confirmation bias – the spontaneous tendency to stick to a decision biases information processing and undermines decision quality. In a set of studies (Sassenberg et al., Citation2014), we tested whether one of these spontaneous tendencies – the confirmation bias in hidden profile tasks – could be reduced by inducing a promotion focus. We predicted that the confirmation bias should be less pronounced in a promotion (than prevention) focus given that a promotion focus leads to higher flexibility.Footnote2

In each study, we manipulated regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) between participants. Participants first received a decision task (Exp. 1 & 2: a personnel selection adapted from Schulz-Hardt et al., Citation2006; Experiment 3: an investment decision adopted from; McLeod et al., Citation1997). Based on a set of initially provided information (favouring a suboptimal solution), participants were asked to report an initial preference. As part of the instruction, we manipulated regulatory focus via a well-established framing procedure via losses or gains (Crowe & Higgins, Citation1997; Sassenberg et al., Citation2003). Participants were either asked to imagine receiving (Exp. 1) or actually received a bonus contingent on decision quality (Exp. 2 & 3). In the prevention condition, they read that they would lose bonus money if they made a bad decision and would not lose it if they did not make a bad decision. In the promotion condition, they learned that they would win a bonus if they made a good decision and would not win the bonus if they did not make a good decision.

In Experiment 1 (Sassenberg et al., Citation2014, N = 99 undergraduate students), participants only indicated whether they considered the information they had received as sufficient (scale range 1–9) – as an indicator of the tendency to rigidly stick to their initial decision. We predicted that people in a promotion focus would be less satisfied with the information they received than those in a prevention focus – given that the former should be more flexible (less rigid) than the latter. The results supported this prediction: Satisfaction with the provided information was lower in a promotion focus (M = 4.60; SD = 1.56) than in a prevention focus (M = 3.54; SD = 1.32). This provided indirect evidence for a lower tendency towards a confirmation bias in a promotion than a prevention focus.

Experiments 2 and 3 sought to demonstrate the same effect for the actual confirmation bias. To this end, participants engaged in an email-based interaction in a simulated three-person group after they had received their individual set of information and reported their initial opinion. Before the group discussion, they were forewarned that the other two group members did not have the same information they had. Participants then composed an email to two other ostensible group members, who were said to do the same to get the decision process underway. Afterwards, participants received two pre-programmed messages, addressing them with their name (which they had entered into the system beforehand). This email exchange was repeated for a second time. After reading the emails, participants indicated their final decision. As a measure of confirmation bias, participants were asked to recall, for 30 information pieces, whether each piece (1) had been part of their original set of information, (2) had been given to them in one of the emails, or (3) was new to them. In addition, participants indicated how important they thought each piece of information was. The confirmation bias score was computed as follows:

Confirmation bias = importance of information in favour of one’s own initially preferred alternative – importance of information contradicting the own initially preferred alternative – importance of information in favour of the other alternatives – importance of information contradicting the other alternatives

Accordingly, higher values indicate a stronger confirmation bias. As predicted, in Experiment 2 (Sassenberg et al., Citation2014, N = 90 undergraduate students) the confirmation bias was less strong in the promotion focus (M = 0.40; SD = 1.19) than in the prevention focus (M = 1.58; SD = 1.39). An analysis of recall performance for information they received only after having made their initial decisions (i.e., via email) provided additional evidence for the impact of regulatory focus on confirmatory information processing. Participants in a promotion focus (M = 30; SD = 25; scale 0–100%) forgot less of the items contradicting their opinion than participants in a prevention focus (M = 44; SD = 22). Hence, participants processed items questioning their initial opinion more thoroughly when they were in a promotion focus (compared to a prevention focus), which signals less rigid information processing.

Experiment 3 replicated this effect with a different decision task in a sample of 49 undergraduate students. The confirmation bias in the promotion focus condition (M = 0.55; SD = 1.22) was again smaller than in the prevention focus condition (M = 1.32; SD = 1.43). In this study (but not in Experiment 2), we also found an indirect effect of regulatory focus on decision performance: more participants in a promotion focus (54%) than in a prevention focus (14%) improved their performance after reading the emails, which was mediated via the confirmation bias.

In sum, a promotion focus made people stick less rigidly to their initial decision than a prevention focus. Earlier research demonstrated that a promotion focus reduces the sunk cost effect compared to a prevention focus (Molden & Hui, Citation2011). In this sense, a promotion focus seems to enable people to deal more flexibly with initial decisions and to reduce spontaneous responding. Other research has demonstrated that the activation of flexibility mindsets also reduces the confirmation bias in the context of information selection and the reliance on (random) anchors in estimation tasks, both in case of conflict mindsets (Kleiman & Hassin, Citation2013) and counterfactual mindsets (Galinsky & Moskowitz, Citation2000; Kray & Galinsky, Citation2003). Furthermore, experiencing conflicting positive and negative emotions at the same time (i.e., emotional ambivalence) causes cognitive flexibility and thereby helps to debias decision making (Rees et al., Citation2013; Rothman & Melwani, Citation2017). Emotional ambivalence might, thus, be another means to elicit a flexible mindset. Taken together, these findings indicate that also in the context of decision-making, spontaneous responses (e.g., confirmatory thinking) can be overruled by priming procedures that foster flexible information processing.

In one study, however, we found that these beneficial effects of flexibility mindsets for decision-making are more fragile than the evidence might suggest. When flexibility is applied to one’s own thoughts, it can rule out biases that result from spontaneous processing, because considering alternatives in this case means deviating from one’s own initial opinion. However, when flexibility is applied to another person with an opposing opinion, it can even increase bias, because considering alternatives in this case means deviating from the other person’s opinion and, thus, sticking with one’s own initial view (Ditrich et al., Citation2019). To test this idea, we conducted a study in which counterfactuals were generated with an interpersonal focus, that is participants imagined themselves to be the protagonist in a scenario and asked to note down thoughts the interaction partner in the scenario could have. We assumed that the activated processing strategy should in this case include more flexible thinking especially about information provided by others, due to the activation of the mindset in relation to others’ thoughts. In line with our prediction, an interpersonal focus when activating a counterfactual mindset led to more flexible responses to others’ thoughts in a subsequent task. Given that the interaction partner in this task shared arguments opposing participants’ own opinion, a flexibility mindset strengthened participants’ own initial view because participants simulated an alternative to the other person’s (and not their own) thoughts. In this interpersonal setting, a counterfactual mindset resulted in a stronger (rather than a weaker) confirmation bias than not activating this mindset. Thus, the effects of counterfactual mindsets, and potentially also of other mindsets are contingent on inducing the mindset independently of an interpersonal focus. If the mindset induction promotes the simulation of alternatives to an interaction partners’ thoughts, it can even strengthen detrimental effects. These detrimental effects clearly require replication, given that the evidence for it is limited to this and one other study (Liljenquist et al., Citation2004).

Discussion

The current article sought to provide an overview of research demonstrating that biases in cognition and behaviour – which result from spontaneous processing and dominant response tendencies – can be reduced by the activation of mindsets that lead to higher flexibility in information processing. Prior research demonstrated that goal and cognitive conflicts, counterfactual thinking, and a promotion focus assert a positive effect on cognitive flexibility. Going beyond these established priming procedures to elicit flexible information processing, our own research showed that a creativity mindset (i.e., the activation of one’s own past creative performance) also increases cognitive flexibility. In line with our prediction, these five flexibility mindsets reduce different kinds of biases that are elicited by spontaneous processing and dominant responses. These effects of flexibility mindsets were found in diverse domains, such as creative performance, stereotyping and prejudice, interpersonal behaviour, and decision-making. Some additional studies provided direct or indirect evidence that heightened cognitive flexibility is the process mediating these effects. Finally, we added some new ways to activate a flexibility mindset to the literature (e.g., negations as a subtle form of cognitive conflict and the recall of one’s own creative performance). The summarised research suggests that flexibility mindsets can help to avoid the unwanted outcomes of spontaneous processing that are often insufficiently reduced or entail backlash effects and reinforcement of bias as result of the explicit attempt to reduce bias (for a review, see Moskowitz & Vitriol, Citation2022).