Abstract

This interdisciplinary design studio organized itself around the razing of an historic oak allée at Washington University in St. Louis, and used the imminent removal of forty-three 100-year-old oaks as a catalyst for project-based investigations into the greater cultural meaning of trees—and their loss. The One Tree Project took the territory of the tree as its classroom, with the oaks serving as site, subject, and platform for public research. Pedagogically, this project identifies attention and unbuilding as fundamental design competencies, and worked with a single tree—in our durational research and ritual felling—as a tool to participate in this transformation.

Attending to unbuilding is an act of repair. It is a stutter in the triumphalism of growth, an interruption of the vector of progress. Attention to unbuilding marks an underexplored center in the symmetry of the design diagram—where transformation, senescence, and breakdown are not terminal, peripheral, unspoken-yet-inevitable end conditions, but rather central qualities to the material competencies of architecture. Breakdown happens; building is unbuilding. Always. Somewhere. It is not a matter of forestalling or preventing brokenness completely. It is, instead, about learning to inhabit them more intentionally, with precision and care. Attending to unbuilding is, in the end, an acceptance of the radical fragility of our world.Footnote1

The One Tree Project stepped into this space. At its heart is the argument that attending to unbuilding is a creative process—attenuating the duration between built and unbuilt, the material occupation of the demolition plan, the altering of living trajectories.Footnote2 And for a beautiful four months in 2017, a group of us in an interdisciplinary design studio at Washington University in St. Louis lived in this liminal, unmarked, and sometimes heartbreaking space of unbuilding (). For in a few short months, a 100-year-old allée of forty-three pin oaks was to be cut down in preparation for a massive campus redevelopment project.

Figure 1. The One Tree Project classroom during the first weeks of the studio. All images courtesy of the One Tree Project unless otherwise noted.

How, then, to mark this moment? Might this radical dis-ordering of the landscape offer an opportunity to re-present an entire domain of architectural practice and education? Rather than hiding from the social and spatial unsettling that such a large de-construction project presumes, we oriented ourselves toward disruption in order to develop a pedagogy of senescence.Footnote3 It marked an attempt to bridge the gap—which remained intact, to be sure—between the umwelt of the tree and of ourselves.Footnote4

To approach this disruption, and to meet the trees at their many registers of meaning, we gathered a plural coalition of poets, historians, Indigenous land stewards, archivists, sculptors, photographers, arborists, ecologists, dendrochronologists, craftspeople, and students in landscape architecture, architecture, and art. We were a collective witness to this act of unbuilding and participants in the generative possibility of dis-ordering.Footnote5 With this expansive arboreal collective of orientations and expertise, the project sought to hold institutions (and ourselves) accountable through both care and conflict. It marked change—particularly difficult change—visibly, collectively, and publicly.

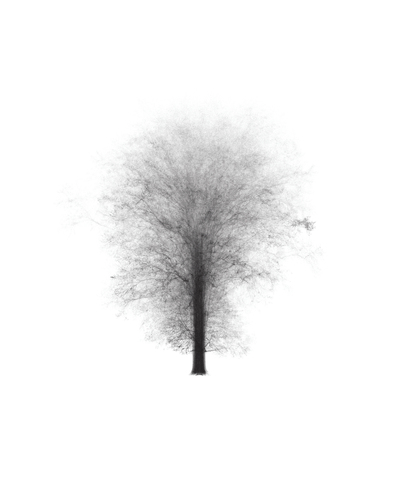

The framing of the course around “one-tree” was always a conceptual conceit. The idea of a single tree leads quickly to understanding a community of trees, and throughout the project we consistently interrogated the ways that our landscape imagination must be tuned to embrace this essential arboreal collectivity ().Footnote6 Our pedagogical method began with a given, seemingly self-evident—in our case, a tree—and to find within this rather everyday condition an entire thicket of underexplored questions.Footnote7 This was, foundationally, an argument for new practices of attention, with loosening architecture’s attachments to abstraction as both the start and end of any inquiry. What the One Tree pedagogy emphasizes, rather, is starting and ending with attention to the material world, and to the displacement of abstraction to one of many waypoints along the way.Footnote8 It is no longer a more-or-less interesting topic that makes a study valuable—after all, how seemingly obvious could a single tree be?—but rather how you do what you do with the material you work with.Footnote9

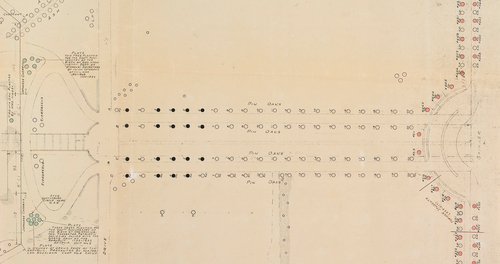

The project began in a moment of discomfort. Washington University was planning a massive capital campaign that would transform the entire eastern half of the historic campus, including the central identifying feature and landscape structure of the University: a 100-year-old pin oak entry allée ( and ). Faculty were presented with an array of design approaches that outlined different distributions for new architecture, engineering, and hospitality buildings, all set within a newly-designed landscape perched atop a three-floor parking garage. The architecture visions were thoughtful. The approach to faculty was considered. The process was well managed. But in all the topics of discussion—the number of faculty offices, future backfill options, the appropriateness of an elaborate green wall inside the new building, and so on—no attention to the profound dis-ordering and unbuilding of the existing living landscape was given. That conversation never made it into design focus groups.

Figure 3. Aerial photo of the allée, 1943. Image courtesy Washington University in St. Louis Special Collections.

Figure 4. 1936 Campus Tree Plan. Image courtesy Washington University in St. Louis Special Collections.

The One Tree Project took the territory of the tree allée as its classroom. For the next four months we held our studios, lectures, seminars, workshops, and performances within the physical, living space of the allée—and invited others to do the same. With our interdisciplinary team, we interrogated the many potential meanings of one-tree, root to crown: from microbial subsoil cultures to species habitats in its highest branches, from the monoculture of the forty-three trees in the allée to the diverse tree community in adjacent Forest Park and beyond. It was a deep entanglement with this thing that we all call a tree.Footnote10 Throughout this process, we drew upon the allée as a living laboratory: asking questions of the trees, asking questions of their context, and asking questions of ourselves.

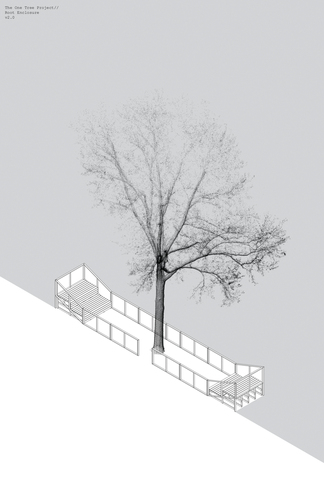

Central to the framing of this project is the goal of making research public. There is a politics in this desired publicity that argues for the building of a more literate and engaged landscape public.Footnote11 We began by appropriating the common construction fence ( and ). As a highly visible project set at the front door of campus, we were naturally required to abide by standard small-construction safety measures. The requirement for a construction fence quickly led us to rethink this common jobsite structure as an inclusionary rather than exclusionary partition. In this contained space, we integrated a terraced perimeter boundary for gathering, viewing, and performing—an Arboreal Commons. Building around a simple 2x4 stud module—an ingrained cultural/structural use of wood—and using standard rolls of orange plastic safety fencing, we constructed a number of iterative, modular tree enclosures around campus in which we staged a variety of arboreal gatherings, films, lectures, and of course, happy hours (). These transparent enclosures served as landscape fora for researching the tree in full sight, while inviting interpretation by a diverse campus public through narratives of cultural and ecological transformation.Footnote12 The success of this open research platform was affirmed when unrelated classes began using the Arboreal Commons for teaching and gathering.

Our project was a modest protest of the removal of these majestic pin oaks. Compromised by soil compaction and the greedy thirst of the surrounding monoculture lawn, the trees were resource deprived and exhibiting terminal stresses. However, they still (and with care) might have lived through a lengthy senescence. What could these trees teach us in their final days? The clock was ticking down on the allée’s removal in May. The space of the allée and its forty-three trees became both stage and staging—where investigation was inseparable from performance—where we were able to engage with the materiality of a tree in ways we would otherwise have shied away from.

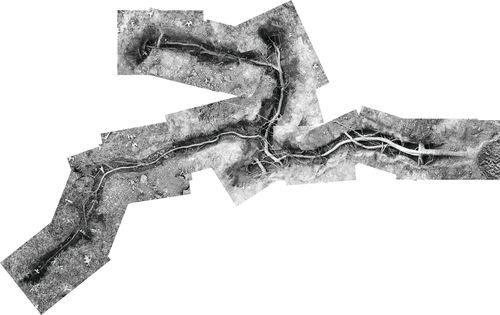

An example: one of our first conversations led us to the seemingly obvious question of “the other half”—the dense root system that lay right beneath our feet but utterly unknown and unseen.Footnote13 Beginning with the largest root buttress, we carried out a laborious, small-tool excavation of a single root—from trunk flare to tip—in an effort to understand its “root brain” interactions with soil, the frequency of grafts, and its network of mycorrhizal associations ().Footnote14 We determined its growth extended well past the commonly held drip line assumptions, but more importantly that the grafting of roots from adjacent trees deeply complicated the singularity of our study. There was clearly no such thing as “one-tree”—even in this homogenous monoculture of decorative pin oaks.Footnote15

As we were busy telling stories about the trees, we soon came to the understanding that the trees themselves were bearers of their own histories: not just in their collar scars, abrasions, and branching structures, but as material archives of the ambient past. Using traditional techniques of manual tree coring and more sensitive resistograph measurements, we gained an understanding of the environmental stresses and historical episodes that inhere with the tree’s girth and structure (). We also worked with a global expert in sonic tree tomography—a process by which the density of the heartwood of a tree is measured by carefully calibrated soundwaves. Here, we determined that while many of the trees passed a visual tree-risk assessment, there were many individuals that were quite compromised in their inner structure. Methodologically, our approach was to merge these various assessment techniques to understand the limits and possibilities of what could be understood through each.Footnote16

In parallel, and building on our collaborative tree(s) research, students also developed individual research-based design projects. One student, inspired by the acoustic technologies of sonic tomography, guided us in “deep listening” by activating the trees as resonators and generators of sound in his Tree Quartet.Footnote17 Another student produced a series of interventions into the material/temporal structure of the tree—excavating a bowl-like form out of the tree-trunk at face height to the tree-ring depth that corresponded to her birth year (). Another student researched an archaic ink recipe made from oak galls, and formulated her own dense ink using material staining techniques and from which she painted portraits of the trees themselves ().

These research and creative projects were capped at the end of the semester by the ritual laying down of a single tree in advance of the larger tree-felling imminent to the campus transformation. On this day, our arborist-collaborators attached the slings of a 300-ton construction crane to the one-tree. It was designed to be a ritual lifting of the tree—roots and all. On the tree-lifting day we worked with a hydro-excavating company to remove the soil from around the entire root deck and, with tree secured by crane, visitors encountered the matting root structure and the extent of root grafts and branching (). Then, for three hours, the crane and tree engaged in a silent, tense, tug-of-war—with the huge crane unable to move this majestic pin oak. Despite extensive archival and infrastructural research, there was an unknown evacuated sewer line with which the tree roots had imbricated themselves. In the end, the tree was laid down gently by the crane in front of a substantial community gathering—a quiet end compared to the chain-sawing and dropping of the rest of the allée in the week to follow.Footnote18

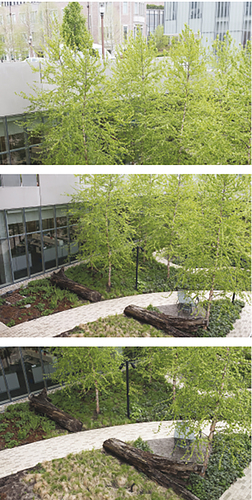

But the project had one final stage in the recursion of attention and repair. As an initiative that grew out of extended conversations with the arboreal collective, students successfully presented a plan to the University and lead design office for the return of the one-tree to the new campus landscape as a nurse log—a living laboratory as well as a decomposing monument. So, at the conclusion of several years of construction, the one-tree was transported in the early morning hours from an outdoor storage area to a newly composed sunken garden, where it still sits in its dynamic ecological dis-assembly. Mushrooms are sprouting, bark is shedding, and moss is emerging (). This is not salvage in its common practice—turning a tree into lumber (though we did that, too)—but an attempt to acknowledge the messiness and vitality of living forms, and to invite others to witness the ongoing cycles of senescence, decay, and regrowth.

Figure 12. The one-tree returned as a nurse log three years later. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Colten.

For those involved with this project, the willingness of so many to commit resources to visible acts of repair, transparency at points of transformation, and attention to things below and beyond our received human scope, gave passage to the pin oaks. In his seminal article on the cultural history of the idea of nature, Raymond Williams closes with the assertion that “we need different ideas because we need different relationships.”Footnote19 In our project’s entanglement with trees, institutions and each other, we have tried to reverse this and, in turn, to open a common space for ideas by staging a new relationship with transformation and unbuilding.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jesse Vogler

Jesse Vogler is an architect and educator whose work sits at the intersection of landscape, politics, and performance. His writing and projects address the entanglements between landscape and law, and take on themes of work, property, expertise, and memory. Vogler is a MacDowell Fellow, Fulbright Scholar, and in addition to his art and research practice, is a land surveyor, codirects the Institute of Marking and Measuring, and teaches across landscape, architecture, art, and urbanism. He is based out of Tbilisi, Georgia, where he is professor and head of the Architecture Program at the Free University of Tbilisi.

Ken Botnick

Ken Botnick has been dedicated to the integration of craft and design in education and in practice for forty years. He was professor of art at Washington University and directed the Kranzberg Book Studio there for twenty-one years, before leaving teaching to dedicate himself to his studio practice full time in Haydenville, Massachusetts. Botnick’s artist books are included in leading collections around the world, including The Getty Center, The Library of Congress, The Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and the Beinecke Library at Yale.

Alisa Blatter

Alisa Blatter is a designer at Arbolope Studio and an adjunct lecturer at the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. Her experiences in planting design, wayfinding and semiotics, site analysis, and cultural landscapes strongly underpin her work. She is passionate about inclusive design that cues people to an immersive connectivity with nature.

Notes

1 Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You’re So Paranoid You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” in Touching Feeling (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 123–51; Elizabeth Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

2 Isozaki Arata, “City Demolition Industry, Inc.,” in Hankenshikushi (Unbuilt) (Tokyo: TOTO Shuppan, 2001), 17–26; Alina Schmuch, Script of Demolition (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2014). Of course the sublime spectacle of building implosion has always had an oversized draw within the architectural imagination (see Jenks’s modernism/postmodernism threshold), but this has generally been spectacle in its most thin form.

3 Consider: J. K. Gibson-Graham, “Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for ‘Other Worlds,’” Progress in Human Geography 2:5 (2008): 613–32; Michael Serres, The Natural Contract (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, 1995), 27–50; Mike Pearson and Julian Thomas, “Theatre/Archeology,” TDR 38: 4 (Winter 1994): 133–61; Robert Filliou, Teaching and Learning as Performance Art (New York: Verlag Gebr. Koenig, 1970); Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “Land as Pedagogy,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3:3 (2014): 1–25.

4 Jakob von Uexkull, “A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men,” Semiotica 89:4 (1992): 319–91; Giorgio Agamben, The Open (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004), 39–43.

5 In a project such as this our indebtednesses are too extensive to list in their entirety, but we would like to enthusiastically acknowledge and thank the following: student researchers: Robert Birch, Alisa Blatter, Shu Guo, Ophelia Ji, Scott Mitchell, Natalie Rainer, Allana Ross, Margot Shafran; Arboreal Collective: Joshua Carron (St. Louis Forestry), Dan Chitwood (Danforth Plant Science Center), Ben Chu (Missouri Botanical Garden), Jennifer Colten (WashU), Jim Duncan (Osage Nation), Dave Gunn (Missouri Botanical Garden), Skip Kincaid (Hansen’s Tree Service), Saundi Kloeckener (Native Women’s Care Circle), Doug Ladd (The Nature Conservancy/WashU), Scott Mangan (WashU), Guy Mott (Adventure Tree), Frank Rinn (Rinntech), Mike Stambaugh (University of Missouri), Kent Theiling (Arborist, WashU), Chris Topp (Danforth Plant Science Center), Molly Tovar (Buder Center for American Indian Studies, WashU), Tomislav Zigo (Clayco). The trust and institutional platform for such a project would be impossible without the incredible support and vision of Bruce Lindsey (then Dean of the College of Architecture), Carmon Colangelo (Dean of the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Art,) Rod Barnett (Chair of Landscape Architecture), and Jamie Kolker (Associate Vice Chancellor, university architect)

6 Robert Pogue Harrison, Forests (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

7 Identifying in this broader approach something our colleague, Eric Ellingsen, neatly summarized as “The One-Thing Pedagogy.”

8 Jane Hutton, Reciprocal Landscapes (New York: Routledge, 2020); Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013).

9 See: Sarah Ahmed, “Orientation Matters,” in New Materialism, ed. Diana Coole and Samantha Frost (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 234–57; Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture from the Outside (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001), 57–73; William Rasch and Cary Wolfe, “The Politics of Systems and Environments, Part I,” Cultural Critique 30 (1995): 5–13.

10 Ian Hodder, Entangled (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

11 We use this construction in conversation with Michael Warner, “Publics and Counter Publics,” Public Culture 14:1 (2002): 49–90; see also Rosalyn Deutsche, “Art and Public Space: Questions of Democracy,” Social Text 33 (1992): 34–53; Irit Rogoff, “We–Collectivities, Mutualities, Participations,” in I Promise It’s Political (Cologne: Museum Ludwig, 2002).

12 Claire Bishop, “Viewers as Producers,” in Participation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 10–17.

13 Wolfgang Bohm, Methods of Studying of Root Systems (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1979).

14 Guided, guardedly, by Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees (Berkeley, CA: Greystone Books, 2015).

15 Anne Tsing, “More-Than-Human-Sociality,” in Anthropology and Nature, ed. Kirsten Hastrup (New York: Routledge, 2013), 27–42.

16 Beryl Hartley, “Exploring and Communicating Knowledge of Trees in the Early Royal Society,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society 64 (2010): 229–50.

17 Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening (New York: iUniverse, 2005), 13-16.

18 Diana Taylor, “Performance and/as History,” TDR 50:1 (Spring, 2006): 67–86.

19 Raymond Williams, “Ideas of Nature,” in Problems in Materialism and Culture (New York: Verso, 1980), 67–85.