ABSTRACT

Preparing new teachers to support all learners and to mitigate the impact of poverty on school learning experiences and outcomes is challenging. Many student teachers are concerned about how to respond to the needs of increasingly diverse groups of learners. While inclusive pedagogy offers a possible solution to the problem, there is still much to be learned about how to prepare and support teachers for inclusion. This study investigates the perspectives of student teachers in enacting an inclusive pedagogy in high poverty school settings. It considers the professional knowledge and skills the student teachers focus on during their initial teacher education. The paper draws on qualitative data from student teachers enrolled on a one-year Professional Graduate Diploma in Education (PGDE) in Scotland. The findings highlight the importance of student teachers: (i) developing professional knowledge for connecting to the lives and experiences of children and young people, and (ii) developing professional and interpersonal skills for inclusion. Implications for initial teacher education are discussed.

Introduction

Internationally, education policies to support inclusive education recognise the need for well-prepared teachers (OECD, Citation2012; UNESCO, Citation2020). However, preparing new teachers to support all learners and to mitigate the impact of educational disadvantage on learning outcomes is challenging. Many student teachers are concerned about how to respond to the needs of increasingly diverse groups of learners (Cochran-Smith et al., Citation2016). A key concern for most student teachers relates to their perceived lack of preparedness for enacting an inclusive pedagogy in classrooms with diverse groups of learners (Black-Hawkins & Amrhein, Citation2014; Symeonidou, Citation2017). However, framing the pedagogical problem as a perceived lack of preparedness deflects from the knowledge and skills that student teachers bring to the classroom situation.

Practising an inclusive pedagogy is a multifaceted experiential process that requires teachers to develop what Black-Hawkins and Florian (Citation2012) refer to as ‘craft’ knowledge. Craft knowledge, learned from experience, develops over time through a complex process involving a multitude of experiences including, but not limited to, teaching, reflection, problem solving and decision making. To date, research into teachers’ craft knowledge in and for inclusive pedagogy has tended to focus on newly qualified and experienced teachers (Black-Hawkins & Florian, Citation2012; Florian & Spratt, Citation2013). Our study is intended to add to this research base, through its exploration of the knowledge and skills student teachers focus on in the latter stages of their initial education as they make sense of their practicum experiences and learn to enact an inclusive pedagogy in high poverty school settings.

Poverty, children and young people’s education

A global drive to end poverty in all its forms was identified by the United Nations (Citation2015) as its number one sustainable development goal. In Scotland, there is a specific national policy targeted at ending child poverty (Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017). However, so long as poverty remains high, efforts must be made to mitigate its effects on children and young people’s education. Poverty is associated with children and young people’s differential school experiences and attainment outcomes, as well as their post-school destinations (Sosu & Ellis, Citation2014). While teachers cannot solve the problem of poverty, they can help to mitigate its effects by supporting children and young people in their classrooms to participate in meaningful and purposeful learning. While poverty-related inequality in learning outcomes has been an issue for some time it has been exacerbated globally in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, which disrupted school systems (Azevedo et al., Citation2020).

There are complex mechanisms by which poverty affects children and young people’s education. For example, poverty affects how children and young people [dis]engage with their school-related activities at home (e.g. after-school reading for leisure and completion of assigned homework tasks). It also affects in-school [dis]engagement (e.g. [ir]regular attendance and opportunities for learning) (Buckingham et al., Citation2013). The role of the teacher is important in mitigating both home and school related effects of poverty on education.

Teachers who adopt specific teaching practices, such as an inclusive pedagogy, may have a lasting effect on some of the challenges faced by children and young people growing up in poverty. It is also important for teachers to consider context specific approaches (Lupton & Thrupp, Citation2013) when responding to the effects of poverty on children and young people. While a lot of attention has been paid to teacher preparation for inclusive education (e.g. Alexiadou & Essex, Citation2015; Florian, Citation2019; UNESCO, Citation2020), some researchers have noted a general lack of consensus about how to prepare teachers for working in high poverty schools (e.g. Lerner et al., Citation2021; McNamara & McNicholl, Citation2016).

In Scotland, where we conducted this study, poverty is recognised as a major inhibitor to successful engagement with school (Child Poverty Action Group, Citation2016; Naven et al., Citation2019), and can be a barrier to academic attainment (Robson et al., Citation2021; Sosu & Ellis, Citation2014). Inclusive pedagogy provides a response to the call aimed at reforming the preparation of teachers in Scotland for the 21st century challenges. In particular, the ‘Teaching Scotland’s Future Review’ called for preparing teachers with relevant knowledge and skills to address low attainment for disadvantaged learners (Scottish Government, Citation2011). This study centres on teacher preparation for enacting an inclusive pedagogy with all learners including those in high poverty school settings.

Inclusive pedagogy

Inclusive pedagogy takes a socio-cultural perspective on learning and promotes pedagogical thinking that enables teachers to create opportunities for learning that are available to all learners. This requires teachers to acknowledge differences between learners, while avoiding the use of categories that stigmatise and/or marginalise, such as labelling learners from lower socio-economic backgrounds (Florian, Citation2012). Enacting inclusive pedagogy requires teachers to provide meaningful learning by extending what is ordinarily available in the classroom to include all learners (Florian & Black-Hawkins, Citation2011). The practice of extending what is ordinarily available offers a way of being a teacher that rejects practices that differentiate planned learning for some learners based on preconceived teacher judgements about what learners will be able to do. This might involve the teacher planning an opportunity for learning that has multiple entry and exit points to accommodate learner differences, but where the teacher will also provide learners with a choice of entry point rather than predetermine the entry points for learners. However, this can be difficult for teachers to operationalise in education systems driven by policies that categorise learners and educational practices and sort or stream learners by perceived ability (Fendler & Muzaffar, Citation2008).

Learning to enact inclusive pedagogy requires student teachers to adopt a relational approach to their practice. As Pantić and Florian (Citation2015, p. 344) claim, student teachers need support to:

understand how their interactions with each other and with other agents contribute to the transformation and reproduction of the structures in which they work … [and] … involves working collaboratively with other agents, and thinking systematically about the ways of transforming practices, schools and systems.

However, working collaboratively to support the enactment of inclusive pedagogy is a complex process that can involve student teachers learning to work with and through other practitioners, and relevant partners, including parents and guardians. Moreover, it has been found that not all student teachers are afforded opportunities to develop such relational working, or have the confidence to do so, in practicum contexts (Graham et al., Citation2019).

This paper builds on a growing body of work, grounded in the Scottish Inclusive Practice Project (Florian & Linklater, Citation2010; Florian & Rouse, Citation2009; Spratt & Florian, Citation2015), with a view to extending understanding for preparing new teachers for inclusion. Our focus centres on understanding the preparation of student teachers to enact an inclusive pedagogy in response to individual differences in the classroom without marginalising or stigmatising learners.

Importance of contextualised responses

There is a deliberate policy drive in many countries to prepare new teachers who can embrace and enact inclusive approaches capable of supporting all learners (e.g. Cochran-Smith & Villegas, Citation2016; OECD, Citation2012; Scottish Government, Citation2014). Yet, schools located in high poverty areas present challenges for teachers, and by extension for student teachers, that go beyond a focus on standard educational provision, for example, with teachers taking on increasing responsibilities to help learners participate meaningfully in school (Naven et al., Citation2019; Thomson, Citation2015). While contexts of socio-economic advantaged schools may appear to be very similar, research also reveals the existence of poverty in relatively affluent areas of the UK (Child Poverty Action Group, Citation2016). This suggests that all schools can have learners experiencing the effects of poverty.

Generating contextualised responses for all learners involves teachers responding to their specific work contexts by re-examining how school practice might be changed to meet the needs of learners in their context (Lupton & Thrupp, Citation2013). Given the potential role that teachers can have in mitigating the effects of poverty on learners’ achievements (OECD, Citation2012; UNESCO, Citation2020), teacher education should aim to prepare new teachers who can support all learners including those experiencing poverty and disadvantage. The OECD (Citation2012) has suggested that this can be achieved by, among other things, the provision of teacher education that enables student teachers to develop the knowledge and skills required for working with disadvantaged learners. However, Florian and Linklater (Citation2010) highlight the importance of teachers’ ability to know how to draw on existing knowledge and skills to support learner differences in inclusive classrooms. From an inclusive pedagogy perspective, this may require teachers to develop new and creative ways of working with others (Pantić & Florian, Citation2015).

Yet, it is unclear what knowledge and skills it is possible for student teachers to develop during initial teacher education (ITE). In this regard, it is suggested that teacher education programmes should focus on preparing teachers to understand and value their pupils’ lives and cultures and to support broader struggles for justice (Kretchmar & Zeichner, Citation2016).

This study investigates what student teachers focus on in the early stages of their professional development as they endeavour to make sense of their ITE experiences and learn to enact an inclusive pedagogy in high poverty school environments in Scotland. We hope to elicit further insights into how student teachers make use of existing knowledge and skills, to signal practical starting points for developing craft knowledge to support an inclusive pedagogy. Our study is guided by the following research question:

What knowledge and skills do student teachers privilege when working with learners living in poverty?

Context of the study

This study investigates the perspectives of student teachers during their practicum in high poverty school settings. In so doing, the study aims to surface the key knowledge and skills related to the principles of an inclusive pedagogy that the student teachers focus on in their practice. This research was conducted within ITE programmes, which were designed with social and educational inclusion at the centre (Florian & Rouse, Citation2009).

The Scottish Government launched the Scottish Attainment Challenge (SAC) in February 2015 and an updated version in 2022, with the purpose of using education to improve the outcomes of children and young people impacted by poverty (Scottish Government, Citation2014, Citation2022). Through the SAC, selected schools in areas of high levels of socio-economic deprivation have received funding to explore innovative ways that may help mitigate the poverty-related attainment gap across Scotland. In this study we elicit the views of student teachers enrolled on a PGDE in Scotland during their ITE.

The ITE programme on which the student teachers were enrolled lasted 36 weeks. This programme aimed to prepare both primary and secondary school teachers and had two key elements: university-based course work and school-based practicum, some of which were in SAC schools. The duration of the practicum experience was 18-weeks with the practicum split into two nine-week placements (School Experience 1 and School Experience 2) undertaken in two different schools. The nine-weeks were further split into two blocks of five weeks and four weeks (School Experience 1a and 1b and School Experience 2a and 2b). Student teachers were taught about inclusive pedagogy on campus and were expected to embrace and enact this learning during their practicum. A commitment to social justice and inclusion underpinned the programme.

Research design

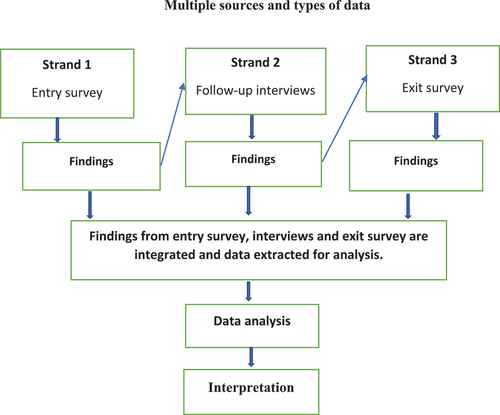

The research design for this study drew from multiple sources comprising three sequential strands (see ). The first research strand involved collecting both quantitative and qualitative data via an electronic survey at the start of the student teachers’ PGDE programme, prior to practicum. The electronic survey included a mixture of closed and open-ended quantitative and qualitative questions. The entry survey data were analysed prior to the implementation of the second research strand, a qualitative study involving follow up semi-structured interviews with five students, who undertook at least one practicum in a high poverty school environment. These interviews took place between blocks 2a and 2b of the second practicum and represented the second research strand as informed by the analysis and findings from the entry survey data. The third research strand was an electronic exit survey, which included a mixture of closed and open-ended quantitative and qualitative questions, administered at the end of the student teachers’ PGDE programme. In this paper we specifically draw on the qualitative data collected from entry and exit surveys and semi-structured interview sources.

Figure 1. Overview of research design.

Data collection

Before undertaking data collection, we ensured that all necessary ethical procedures were in place. Research ethics approval for the study was obtained from the relevant Ethics Committee at the University of Aberdeen. We followed appropriate protocols including voluntary participation, privacy and confidentiality, right to withdrawal and anonymity (British Educational Research Association [BERA], Citation2018).

The response rate to the entry questionnaire was 45% (n = 142), comprising 48% (n = 81) of PGDE primary students and 41% (n = 61) of PGDE secondary students. The response rate to the exit questionnaire was 15% (n = 47), comprising 64% (n = 30) of PGDE primary students and 36% (n = 17) of PGDE secondary students. All 47 students who completed the exit survey also completed the entry survey. Five student teachers on the PGDE programme voluntarily participated in semi-structured interviews and completed both the entry and exit surveys.

The open-ended entry and exit survey questionnaire, and the semi-structured interview schedule contained the following questions:

What knowledge do you think a student teacher requires to work with learners living in poverty?

What key skills do you think a student teacher requires to work with learners living in poverty?

The survey questions, above, were framed using the terms ‘knowledge’ and ‘skills’ which are familiar to the student teachers rather than the more specific term ‘craft knowledge’ found in the inclusive pedagogy literature (Black-Hawkins & Florian, Citation2012). The questions are intended to encourage the student teachers to reflect on what knowledge and skills they can engage with during their practicum. This approach contrasts with questions that focus on whether student teachers feel prepared and/or have the necessary knowledge and skills to work with learners living in poverty.

The work presented here is characterised by some limitations. As indicated earlier, the response rate to our exit survey was low and this should be considered when interpreting our findings. The sample was based on one ITE programme in Scotland and this may have implications for wider applicability of our findings beyond the Scottish context. The respondents in the study were self-selected and as such there is the potential for bias. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study helps to reveal a rich description of the knowledge and skills that student teachers can engage with to enact an inclusive pedagogy in high poverty school environments.

Data analysis and findings

This study aims to surface what student teachers focus on as they make sense of their practicum experiences and learn to enact an inclusive pedagogy in high poverty school environments. The study followed what Gale et al. (Citation2013, p. 1) refer to as ‘a framework analytical method for qualitative data analysis’. This seven-stage procedure involved the following: (i) data extraction, (ii) familiarisation with the data, (iii) coding, (iv) developing a working analytical framework, (v) applying the analytical framework, (vi) charting data into the framework matrix, and (vii) interpreting the data.

Members of the research team read the qualitative data thoroughly to become familiar with the whole data set. After discussion, a set of codes was agreed, each with a brief descriptor. This formed the initial analytical framework. The research team then independently checked the data set using this framework, noting any new codes. The codes were then discussed to confirm why each coded section had been interpreted as meaningful, what it told us about respondents’ views in relation to knowledge and skills, and how it might be useful for answering the research questions. Through this process we created a more focused set of interlinked sub-themes from the main themes: professional knowledge, professional skills and interpersonal skills (see for extracts of the developing analytical process).

Table 1. Development of themes and sub-themes through the qualitative data analysis process.

The main themes elicited from our analysis are professional knowledge, professional skills, and interpersonal skills. We use these main themes to structure and present our findings. A selection of representative quotes sourced from each of the data collecting strands (i.e. PGDE primary and secondary, PGDE entry and exit survey) are provided to illustrate the perspectives conveyed by the research participants.

Professional knowledge

The theme of professional knowledge was consistently highlighted by the research participants throughout their initial teacher education. Within this theme, the student teachers identified the importance of understanding how present-day poverty can affect children and young people in different ways. This is illustrated with the following quotations:

I think it is important to know what is going on in your class and to know your children, the issues that are going on in the class, the homes that the kids are coming from. (PGDE primary interview)

Proper experience or knowledge of what poverty is and pupils’ experiences of poverty. (PGDE exit survey)

Moreover, while the student teachers wanted to learn about poverty in the present day, they also highlighted the importance of getting to know the children and young people, which is captured in the sub theme of developing knowledge about the child. This sub theme of developing knowledge of the child has been disaggregated into three interconnected knowledge layers: micro, meso and macro, that interact to shape the lives of the learners and what they bring to school.

At the micro-level the student teachers recognised the importance of getting to know each child as an individual. For example, they highlighted:

To be a good teacher, we need to understand the needs of individual learners and try to satisfy their needs, taking into account that there is the whole environment of the school and the whole environment of education … . (PGDE secondary interview)

Understand that some children might find school the only positive and safe environment they can live in. Treat everyone equitably according to their specific individual needs whilst meeting and catering for the needs for all. (PGDE exit survey)

The student teachers also identified getting to know the child at a meso-level. In so doing, they surfaced knowledge of linkages between home and school, between peer group and family, and between family and institutions, as well as any changes within the family that may impact on the child or young person at school.

An understanding of the support available to children and families. (PGDE entry survey)

Get to know the child and what their home life is like as this can be a big factor in how their learning will be affected within any given situation. (PGDE exit survey)

For the student teachers, getting to know the child or young person at the meso-level serves to enable them to understand more of the child or young person’s background in terms of their home life and any connections with external support agencies. While the student teachers link this knowledge to better supporting learning in the classroom, it is not clear how or if they made use of this knowledge to support an inclusive pedagogy.

At a macro-level, student teachers indicated that they wanted to know about each child or young person in terms of their cultural background and values.

Also be aware of cultural differences as well. Things like parental involvement. It is there, but more of inviting families in and celebrating their culture is something that we’re not terribly good at doing in Scottish schools. (PGDE primary interview)

Find out about the cultural background of your pupils by speaking with support staff and particularly community support workers. (PGDE exit survey)

This macro-level knowledge of the child serves to enable the student teachers to understand each child or young person in terms of their different cultural backgrounds and belief systems. This knowledge helps the student teachers connect with the child or young person, fostering positive relationships, and gaining insight into the key influences on the child or young person.

While the examples above were consistently referred to by the student teachers throughout their ITE, at the end of the programme, they introduced additional knowledge, not mentioned on entry to the programme. This additional insight highlighted the importance of knowledge to support classroom and behaviour management. Moreover, some student teachers promoted an inclusive perspective to classroom and behaviour management with comments such as:

... being consistent with classroom management and perceptive about barriers to learning for all (PGDE exit survey)

Other student teachers thought it would be beneficial to have received additional or specialist support from a ‘more knowledgeable other’:

As a student teacher I found that classroom management was very difficult and would have appreciated a specialist on behavioural management to support me … (PGDE exit survey)

These findings elicited at the end of the programme suggest that behaviour management is an important issue that concerns some of the student teachers as they engage with their practicum in high poverty school settings.

Professional skills

The student teachers at each data collection point consistently identified the importance of developing professional skills for enacting inclusion, and for recognising and responding to child poverty. The theme of professional skills (see ) relates to the student teachers’ recognition of the need to respond to the children or young people in the context in which they were working. Regarding enacting an inclusive pedagogy, the student teachers highlighted the importance of interacting with all learners in a manner that avoids stigmatising or marginalising anyone.

Teachers need to demonstrate an ability to treat each child as an individual, without making them feel as though they are different. (PGDE entry survey)

Teachers need to be able to provide any additional nurturing the children may require in such a way that they feel included and other learners don’t find out. (PGDE exit survey)

Regarding skills for working with others to support an inclusive pedagogy, on entry, the student teachers identified the importance of team working skills as exemplified in the quotes below:

Collaborative skills are key, being flexible and capable of working with other staff and professional services. (PGDE entry survey)

Liaison skills for when working with other support systems. (PGDE entry survey)

It is perhaps not surprising that the student teachers highlighted these skills on entry to the programme given that the process for selection to the ITE programme required them to demonstrate examples of when they had worked successfully in teamworking situations.

The student teachers also highlighted observation skills to enable the identification of additional support for enacting inclusion.

I think that observation skills are important for teachers working with children/young people living in poverty. (PGDE entry survey)

Teachers should be observant and dedicated to providing the extra time and resources needed to help the children. (PGDE entry survey)

The student teachers recognised the importance of demonstrating skill in adapting to the context in which they find themselves, and for responding to learner differences.

Adapting teaching style to fit the needs of all. (PGDE entry survey)

Be able to adapt to different situations. (PGDE entry survey)

Must be able to adapt to assist the child. (PGDE entry survey)

However, by the end of their ITE, the student teachers no longer identified professional skills relating to teamworking, observation and adaptability as key skills for working in high poverty context schools. This suggests a narrowing of purview during practicum, resulting in a greater focus on getting to know the children at the expense of collaborating with others.

Interpersonal skills

The student teachers at each data collection point consistently identified the importance of building rapport with children and their families and highlighted the importance of developing interpersonal skills relating to listening, communication and empathy. They noted the importance of listening skills for working with learners from poor backgrounds.

A teacher must be a good listener; there may be issues that the child is facing, and the teacher must be able to provide an open environment for the child to speak, if desired. (PGDE entry survey)

You need to be a good listener … it just takes time and that’s where patience really comes in, I think, trying to attempt to understand. (PGDE secondary interview)

Further to the value of listening skills, the student teachers also highlighted the importance of not stigmatising or singling out learners. For example, one student teacher noted:

Listen to them, appreciate them, don’t let them feel “poor” .(PGDE exit survey)

The student teachers also recognised the need for communication skills for working with learners and parents:

Communication with pupils and parents. Being able to overcome barriers such as disinterested parents, language barriers. (PGDE entry survey)

Communication is key and trust. This extends to family and the child. These individuals need to feel like they can come to you with questions or for help. (PGDE exit survey)

Similarly, the student teachers identified skill in exercising empathy to connect with children and to support them to thrive.

Interpersonal skills such as empathy and kindness. (PGDE entry survey)

You have to address the needs of individuals but at the same time you cannot pander to them. You are working hard for them; they need to work hard for you, and it is building the trust and respect with each other. It is the relationships between pupil and teacher are really, really, important for me. (PGDE secondary interview)

Overall, these findings highlight the importance the student teachers afford to interpersonal skills such as listening, communicating and empathy for fostering positive relationships with the children or young people under their care. While these interpersonal skills may be considered important to teaching in all school environments, they may be particularly relevant to teaching in high poverty school settings. This is further illustrated by the fact that there were no instances of any interpersonal skills identified on entry, disappearing by the end of the student teachers’ ITE.

Discussion

This study has enabled us to investigate the professional knowledge, professional skills and interpersonal skills student teachers focus on during their initial teacher education as they learn to enact an inclusive pedagogy in high poverty school settings. The knowledge and skills identified by the student teachers perhaps shine some light on possible starting points for developing craft knowledge characteristic of inclusive pedagogy (Black-Hawkins & Florian, Citation2012).

The findings indicate that student teachers consistently highlight the importance of developing knowledge and skills for connecting to children and young people’s lived experiences. This finding is important for developing an inclusive pedagogy, as working to support all learners in a school setting requires the teacher to recognise learners as individually unique without marginalising or stigmatising anyone (Florian & Spratt, Citation2013). For student teachers, to develop in-depth knowledge of the lived experiences of children and young people resonates with a networked ecological perspective as identified by Neal and Neal (Citation2013). Moreover, for the student teachers in the study reported here developing an in-depth knowledge of the lived experiences of the children and young people can be disaggregated into three interconnected aspects (micro, meso and macro) of the lives of the learners. By paying attention to these interconnected aspects, this can support student teachers to take an interest in the welfare of the ‘whole child’ and is consistent with the student teachers’ commitment to teaching all learners in their classes (Florian, Citation2014).

The findings further indicate that the student teachers consider wide knowledge of the learners beneficial in enabling them to maintain respect for all children, young people and their families. This may help to bridge any barriers created by cultural and socio-economic differences apparent between the student teachers and the children and young people (Grudnoff et al., Citation2016). Supporting student teachers to know the school contexts and to foster community engagement, including joint problem solving is perhaps something that could be developed further (Graham et al., Citation2019).

The student teachers consistently highlight the importance of developing knowledge for recognising and responding to child and young people’s poverty in the classroom. This finding presents an opportunity for ITE to consider further how the student teachers can be supported to understand specific practicum contexts for the benefit of all learners. In addition, ITE might support student teachers to learn from research into the complex ways that poverty affects children and families inside and outside school (Child Poverty Action Group, Citation2016). For example, as part of the university-based element of ITE, the student teachers may be provided with reading materials and case studies focusing on present day poverty and related issues. During practicum, the student teachers may be provided with opportunities to participate in community investigations and/or community placements (Zeichner, Citation2010) that enable student teachers to gain a greater insight into the local environment of the children and young people they work with. The student teachers can then draw on these related experiences to support the inclusion of all children and young people in the classroom.

While the findings show that student teachers recognised the importance of developing knowledge for connecting to the lives and experiences of the children and young people, and for recognising and responding to child and young people in poverty in the classroom, other knowledge identified as important on entry to the PGDE programme became less visible by the end of their ITE. For example, after practicum, the student teachers no longer highlighted the importance of knowledge of appropriate pedagogies, and knowledge of children’s services and sources of support. This is not to say that the student teachers did not consider this knowledge to be important, rather they appear to focus more on responding to the immediacy of the classroom environment context (Lupton & Thrupp, Citation2013).

The student teachers identified the importance of fostering rapport and developing positive relationships with the children or young people and behaviour management as key knowledge to be developed during their practicum in high poverty school settings. This suggests that student teachers preparing to undertake practicum would benefit from further support to enable them to create situated, context specific environments for learning. This might include, but not be limited to developing as part of their ITE: listening skills to better understand the needs of the children; more focused activities that centre on relationship building between the student teacher and the children or young people; and working with knowledge of community assets to support meaningful links between planned learning and the social, emotional and behavioural learning for all learners (Sosu & Ellis, Citation2014). This would be beneficial in terms of supporting student teachers in developing more nuanced understandings of the children and young people to inform their decision making. For example, a better understanding of the children and young people and the environment in which they are learning may help student teachers extend what is ordinarily available in the classroom for the benefit of all (Florian & Black-Hawkins, Citation2011).

Developing professional knowledge for behaviour management was identified by the student teachers as important for working in high poverty context schools. Some of the student teachers framed the importance of knowledge of behaviour management in terms of maintaining consistency for the pupils and being perceptive to difficulties which some pupils encounter in their learning. Other student teachers saw this in additional support terms, for example, seeking specialist support with behaviour management. Perhaps this finding can be explained by the nature of the practicum experience whereby student teachers, in complex school environments, appear to take on too much responsibility too soon. This suggests a need within ITE and practicum schools to reconsider how student teachers might best be supported to take account of the different school contexts in which they are placed.

While an inclusive pedagogy perspective underscores the importance of teachers developing creative and new ways of working with others and promotes a relational approach to practice (Pantić & Florian, Citation2015), the findings presented here suggest this is an aspect of inclusive pedagogy that student teachers find difficult to develop. This may be a result of the way student teachers operate during practicum whereby a great deal of effort is channelled into getting to know and build positive relationships with the learners within the time available for the practicum. A possible explanation for this could be the limited opportunities for student teachers to engage with other professionals during practicum (Graham et al., Citation2019).

Despite not highlighting the importance of collaborative skills on exit from the programme, the student teachers reaffirmed the importance of developing so called professional skills for inclusion. This appears to be a contradiction in the student teachers’ understanding of the importance of working with others in and for the enactment of inclusive pedagogy. This insight presents an opportunity for ITE to consider further how they might support student teachers to make the link between developing skills for collaboration and their understanding of inclusive pedagogy in the classroom setting. Developing creative and new ways of working with others in the practicum setting is a key aspect of inclusive pedagogy that, perhaps, requires further attention. For example, student teachers may be provided with opportunities that enable them to enhance their knowledge and skills for working with others within the practicum setting to support the inclusion of all learners.

The findings indicate that the student teachers consistently identified the importance of interpersonal skills such as understanding, patience, kindness, approachability, and listening for working with learners experiencing poverty. These interpersonal skills are important for developing an ethos of care and enacting quality relationships between the student teachers and the learners. They contribute to the student teachers’ commitment to the welfare of the ‘whole child’, which resonates with the inclusive pedagogy principle that teachers must believe they can teach all children (Florian, Citation2014). Within the list of interpersonal skills highlighted by the student teachers, listening to learners has been identified (e.g. Florian & Beaton, Citation2018) as vital for inclusive pedagogy in terms of planning next steps for learning. Listening can also be linked to the idea of ‘co-agency’ (Hart et al., Citation2004), which involves student teachers designing learning opportunities that promote purposeful conversations in the classroom and enable learners to actively shape, make meaningful choices, and take increased responsibility for their own learning.

Conclusion

This study investigated what student teachers consider to be the key knowledge and skills required for working in high poverty school settings. The study has reported student teachers’ perspectives about the knowledge and skills they focus on during their practicum as they learn to enact an inclusive pedagogy. The knowledge and skills constitute what student teachers consider important and achievable in their practicum context. Moreover, the identified knowledge and skills signal possible practical starting points for student teachers developing craft knowledge in and for inclusive pedagogy over time. This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on inclusive pedagogy for supporting all learners including those in high poverty school environments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexiadou, N., & Essex, J. (2015). Teacher education for inclusive practice – responding to policy. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2015.1031338

- Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Iqbal, S. A., & Geven, K. (2020). Simulating the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: A set of global estimates. Policy Research Working Paper. World Bank,

- Black-Hawkins, K., & Amrhein, B. (2014). Valuing student teachers’ perspectives: Researching inclusively in inclusive education? International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 37(4), 357–3375. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2014.886684

- Black-Hawkins, K., & Florian, L. (2012). Classroom teachers’ craft knowledge of their inclusive practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 18(5), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709732

- British Educational Research Association [BERA]. (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research. Publisher.

- Buckingham, J., Wheldall, K., & Beaman-Wheldall, R. (2013). Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: The school years. Australian Journal of Education, 57(3), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944113495500

- Child Poverty Action Group. (2016). Child Poverty Facts and Figures. Accessed, 2018 January 22. http://www.cpag.org.uk/child-poverty-facts-and-figures

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Villegas, A. M. (2016). Preparing teachers for diversity and high- poverty schools: a research-based perspective. In J. Lampert & B. Burnett (Eds.), Teacher education for high poverty schools (pp. 9–31). Springer.

- Cochran-Smith, M., Villegas, A. M., Abrams, L., Chavez-Moreno, L., Mills, T., & Stern, R. (2016). Research on teacher preparation: charting the landscape of a sprawling field. In D. Gitomer & C. Bell (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Teaching (pp. 439–546). AERA.

- Fendler, L., & Muzaffar, I. (2008). The history of the bell curve: Sorting and the idea of normal. Educational Theory, 58(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2007.0276.x

- Florian, L. (2012). Preparing teachers to work in inclusive classrooms: Key lessons for the professional development of teacher educators from scotland’s inclusive practice project. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(4), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487112447112

- Florian, L. (2014). What counts as evidence of inclusive education? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29(3), 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.933551

- Florian, L. (2019). Preparing teachers for inclusive education. In M. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Teacher Education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1179-6_39-1

- Florian, L., & Beaton, M. (2018). Inclusive pedagogy in action: Getting it right for every child. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(8), 870–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1412513

- Florian, L., & Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. British Educational Research Journal, 37(5), 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.501096

- Florian, L., & Linklater, H. (2010). Preparing teachers for inclusive education: Using inclusive pedagogy to enhance teaching and learning for all. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40(4), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2010.526588

- Florian, L., & Rouse, M. (2009). The inclusive practice project in Scotland: Teacher education for inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(4), 594–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.003

- Florian, L., & Spratt, J. (2013). Enacting inclusion: A framework for interrogating inclusive practice. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 28(2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2013.778111

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. British Medical Council Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Graham, A., MacDougall, L., Robson, D., & Mtika, P. (2019). Student teachers’ social capital relations in schools with high numbers of pupils living in poverty. Oxford Review of Education, 45(4), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.1502079

- Grudnoff, L., Haigh, M., Hill, M., Cochran-Smith, M., Ell, F., & Ludlow, L. (2016). Rethinking initial teacher education: Preparing teachers for schools in low socio-economic communities in New Zealand. Journal of Education for Teaching, 42, 451–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2016.1215552

- Hart, S., Dixon, A., Drummond, M. J., & McIntyre, D. (2004). Learning Without Limits. OUP.

- Kretchmar, K., & Zeichner, K. (2016). Teacher preparation: A vision for teacher education to impact social transformation. Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(4), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2016.1215550

- Lerner, J., Roberts, G. J., Green, K., & Coleman, J. (2021). Prioritizing competencies for beginning teachers in high-poverty schools: A Delphi study. Educational Research: Theory and Practice, 32(2), 17–46.

- Lupton, R., & Thrupp, M. (2013). Headteachers’ readings of and responses to disadvantaged contexts: Evidence from English primary schools. British Educational Research Journal, 39(4), 769–788.

- McNamara, O., & McNicholl, J. (2016). Poverty discourses in teacher education: Understanding policies, effects and attitudes. Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(4), 374–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2016.1215545

- Naven, L., Sosu, E., Egan, S., & Spencer, J. (2019). The influence of poverty on children’s school experiences: Pupils’ perspectives. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 27(3), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1332/175982719X15622547838659

- Neal, J. W., & Neal, Z. P. (2013). Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Social Development, 22(4), 722–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12018

- OECD. (2012). Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools. 2018 20 November: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/50293148.pdf

- Pantić, N., & Florian, L. (2015). Developing teachers as agents of inclusion and social justice. Education Inquiry, 6(3), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v6.27311

- Robson, D., Mtika, P., Graham, A., & Macdougall, L. (2021). Student teachers’ understandings of poverty: Insights for initial teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(1), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1841557

- Scottish Government. (2011). Teaching Scotland’s Future. Author. Retrieved from: http://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/337626/0110852.pdf

- Scottish Government. (2014). Child poverty strategy for Scotland: Our approach 2014 – 2017. https://scotgov.publishingthefuture.info/publication/child-poverty-strategy-for-scotland-our-approach-2014-2017

- Scottish Government. (2022). Scottish attainment challenge - 2022 to 2023 – 2025 to 2026: Fairer Scotland duty assessment. Author. Retrieved from: Scottish Attainment Challenge - 2022 to 2023 – 2025 to 2026: fairer Scotland duty assessment - gov.scot (www.gov.scot).

- Sosu, E. M., & Ellis, S. (2014). Closing the Attainment Gap in Scottish Education. 2019 7 April: https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/education-attainment-scotland-full.pdf

- Spratt, J., & Florian, L. (2015). Inclusive pedagogy: From learning to action. Supporting each individual in the context of ‘everybody’. Teaching and Teacher Education, 49, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.03.006

- Symeonidou, S. (2017). Initial teacher education for inclusion: A review of the literature. Disability & Society, 32(3), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1298992

- Thomson, P. (2015). Poverty and education. The Forum, 57(2), 205–207. https://doi.org/10.15730/forum.2015.57.2.205

- UNESCO. (2020). Inclusive teaching: Preparing all teachers to teach all students. Global Education Monitoring Report Policy Paper 43. Retrieved 17 June 2021: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374447

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable development goals. 2022 6 December: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college-and university-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347671