Abstract

We are in the midst of a global transition in which digital “screens” are no longer simply entertainment devices and distractions; rather, adolescents are currently living in a hybrid reality that links digital spaces to offline contexts. Yet, psychological scientists studying the mental health impact of digital experiences largely focus on correlations with “screen time,” leading to oversimplified and atheoretical conclusions. We propose an alternative, functional approach to studying adolescent mental health in the digital age, one that examines why and how digital media affect adolescent development. Specifically, we suggest that understanding identity development—the core developmental task of adolescence—can help pinpoint the digital experiences that contribute to healthy versus problematic mental health outcomes. We have four objectives: (1) integrate principles from clinical and personality psychology with developmental theory to present a theoretical framework for investigating narrative identity; (2) show how this framework provides a useful lens for evaluating the impact of digital media on adolescents; (3) suggest a set of novel hypotheses that specify what kinds of digital contexts and experiences lead to healthy versus problematic mental health outcomes; and (4) propose a detailed research agenda that tests these hypotheses.

Introduction

There is a heated debate being played out within academia and across scientific communities about the impact of “screen time” on young people’s mental health and wellbeing. This discourse is amplified across public media outlets, with headlines that scream for bans or restrictions on screen time, lest it cause the current generation of youth to become increasingly violent, addicted, depressed, anxious, and even suicidal. It is clear that the current generation of young people is growing up in a digital ecosystem unprecedented in its ubiquity and complexity. Far less clear are the mental health implications, the risks versus benefits, of this brave new digital world.

It is understandable that adults from previous generations—scholars, parents, policy makers alike—are concerned about digital media and its amorphous conduit, “screen time”: it represents new and uncharted social, emotional, and cognitive affordances. Adolescents and the younger members of the millennial generation are the first to have grown up using and interacting with mobile (i.e. ubiquitously accessible), socially networked digital media from birth. In the remainder of this article, when we refer to digital media, we specifically mean social media and video games. With social media we refer to the suite of interactive products that enable social interaction (Hall, Citation2018), including WhatsApp, WeChat, Facebook, Snapchat, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Twitch, Medium (and other blogging platforms), and YouTube. Youth have adopted these digital tools at such a rapid pace that research, policy, and intelligent public discourse have lagged behind large-scale uptake. Thus, a significant digital generation gap seems to have emerged.

In an attempt to understand the impact of these new digital spaces, social scientists have thus far focused primarily on counting hours spent in front of screens and examining correlations with mental health indices. More recently, researchers have begun to make strong calls for studies that include large, representative samples of youth, followed longitudinally, with measures that go beyond self-reports, and methodologically and statistically rigorous analytic plans that include appropriate control variables (Drummond & Sauer, Citation2019; Ferguson & Wang, Citation2019; Heffer et al., Citation2019; Kardefelt-Winther, Citation2017; Orben & Pzrybylski, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Sewall, Rosen, & Bear, Citation2019). These methodological improvements are no doubt essential for moving the field forward. However, methodological considerations are not enough and, in fact, may not even be the appropriate starting point. We propose that what is urgently needed is a theoretical framework for guiding a new empirical agenda. This theoretical framework needs to move beyond the vague, all-encompassing concept of “screen time”: the frequency and duration of experiences in front of a digital screen. The term screen time is, in fact, becoming meaningless in the current landscape of digital applications, platforms, and mobile ubiquity. Instead, we need to move toward a functional theoretical framework that examines why and how digital media impacts on young people and the complex interplay between digital and offline experiences.

The current article applies a theoretical framework focused on adolescent identity development. Our main argument is that understanding the processes underlying this core developmental concern of adolescents can help pinpoint the digital experiences that will contribute to both healthy normative development as well as the emergence of serious mental health concerns. We have four main objectives: (1) integrate core principles from clinical, social, and personality psychology with developmental theory to present a theoretical framework with narrative identity at its core; (2) show how this narrative identity development framework provides a useful lens for evaluating the impact of digital media on adolescents; (3) suggest a set of novel hypotheses emerging from this framework that specify what kinds of digital contexts and experiences lead to healthy versus problematic mental health outcomes; and (4) propose a set of research designs that can test these hypotheses.

Hybrid Reality and Developmental Goals

We begin with two premises. First, we are at a turning point in how we perceive and experience the digital world and its relation to the physical one. Currently, young people—having grown up with tablets in their cribs and phones in their high chairs—no longer experience much of their digital, online interactions and physical, offline interactions as functionally distinct (Boyd, Citation2010). More than a decade into the digital age, most of us, but especially youth, are living their everyday lives in an offline world that is woven dynamically and interactively with online contexts in a single holistic ecosystem we herein refer to as hybrid reality. As just one example, currently about 40% of heterosexual and 60% of same-sex couples have met their partners online (Rosenfeld, Thomas, & Hausen, Citation2019). This is in stark contrast with just eight years ago when only 22% of heterosexual couples met each other online (Rosenfeld & Thomas, Citation2012; Rosenfeld et al., Citation2019). Even for this biologically based need, finding a partner, digital interactions have become essential. Distinctions between offline and online spaces are increasingly unclear, and the boundaries across this hybrid reality are likely to become more blurred in the next decade (Kelly, Citation2019). Contemporary media scholars (Boyd, Citation2010; Kelly, Citation2019; Peter & Valkenburg, Citation2013) have started to grapple with these intermingled realities and the complexities they engender. But the field of psychology has often taken a more simplistic approach, dichotomizing digital media effects as either good or bad, healthy or unhealthy. Psychological science needs to quickly catch up to the realities of how young people live their everyday lives in this hybrid ecosystem, lest the field becomes hopelessly irrelevant to those lives.

Our second premise dovetails with the first: given that offline and online spaces are becoming functionally similar, we need to study adolescents’ online experiences through the same functional lens as their offline ones. Therefore, to understand the impact of digital spaces on adolescents, it is essential to examine how their developmental needs and goals are served by these spaces. Human developmental needs have been studied for about 100 years (e.g. Adler, Citation1956; Erikson, Citation1968; Freud, Citation1927; Loevinger, Citation1976; Maslow, Citation1970; Rogers, Citation1961; Winnicott, Citation1965), and there is considerable consensus that the core needs and goals of adolescents are centered around the task of identity development. We propose that it is these needs and goals that specify how and why digital experiences impact on adolescent emotional and mental health. Understanding adolescents’ digital experiences through this functional, developmental lens can home in on more precise, validated constructs for future research and suggest specific recommendations for parents, teachers, clinicians, policymakers, and digital designers.

Adolescence and Mental Health

The current article focuses on adolescents, defined as people between 10 and 24 years old, following recent convincing arguments that the period between childhood and adulthood has expanded over the last century with unprecedented social forces that have delayed completion of education, marriage, and parenthood (Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne, & Patton, Citation2018). More specifically, it is mid-adolescence to early adulthood we are most concerned with: Although early adolescence is interesting for a host of identity-relevant reasons (as we touch on later), it is also a distinct precursor to the central issues we aim to address regarding digital participation. Specifically, a host of psychosocial changes amplify novel developmental goals during mid-adolescence: autonomy from parents (e.g. Collins, Laursen, Mortensen, Luebker, & Ferreira, Citation1997; Erikson, Citation1968), acceptance and admiration by peers (e.g. Brown & Larson, Citation2009; Prinstein & Giletta, Citation2016), and the construction of a coherent identity (Erikson, Citation1950, Citation1968). We aim to demonstrate how these goals interact with particular digital affordances that have critical implications for identity development and subsequent mental health outcomes.

Adolescence is often considered a sensitive developmental window, characterized by significant opportunities as well as vulnerabilities. The two most prevalent mental health problems in adolescence are anxiety and depression. Anxiety disorders are the most frequently diagnosed mental health problem for youth and the earliest to emerge among all forms of psychopathology, affecting up to 18% of children and adolescents (Merikangas et al., Citation2010; Mojtabai, Olfson, & Han, Citation2016; Olfson, Druss, & Marcus, Citation2015; Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye, & Rohde, Citation2015). Without treatment, anxiety symptoms are stable over time and they predict premature withdrawal from school, lowered school performance, substance use, early parenthood, behavioral problems, and suicidal behavior (Duchesne, Vitaro, Larose, & Tremblay, Citation2008).

By 2020, depression is estimated by the World Health Organization to become the leading cause of global disease burden for young people aged 10–24 years (Gore et al., Citation2011). A full 20–24% of young people will experience a major depressive disorder by the time they reach the age of 18 (De Graaf, ten Have, van Gool, & van Dorsselaer, Citation2012). Moreover, a much larger proportion of adolescents report sub-clinical depressive symptoms that cause immediate impairment as well as increased risk for major depressive disorder later on (Wesselhoeft, Sørensen, Heiervang, & Bilenberg, Citation2013). Adolescent depression predicts a host of future problems, including substance abuse and obesity, academic failure, relationship problems, risky sexual behavior, and legal infractions (Keenan-Miller, Hammen, & Brennan, Citation2007; Thapar, Collishaw, Pine, & Thapar, Citation2012). Perhaps most seriously, both anxiety and depression are linked to suicide (Nock et al., Citation2013); depressed individuals have a 30-fold higher likelihood of successfully committing suicide than their non-depressed counterparts (Klein, Torpey, Bufferd, & Dyson, Citation2008).

Clearly there needs to be a concerted effort to identify and address the factors that influence these mental health issues in adolescence. Many factors—from emotion-regulation patterns to peer and family interactions to school environments—have been implicated in adolescent mental health problems (e.g. Dahl, Citation2004; Fromme, Corbin, & Kruse, Citation2008; Steinberg, Citation2008; Petersen, Citation1988). In recent years, however, there has been an upswell of studies that have focused on the impact of screen-based media on young people’s mental health.

Research on Screen Time

There are reasonable arguments for putting so much energy and resources into studying the impact of new digital media on young people’s mental health. The current generation is the first to have grown up using and interacting with mobile digital products from birth. Most media scholars and tech-industry experts mark the massive change in digital participation from about 2007, when the iPhone was first introduced (Degusta, Citation2012). Mobile phone use grew at exponential rates from that period onward. For example, a recent study in the United States (Common Sense Census: Rideout, Citation2017) showed that children from 0 to 8 years of age used some sort of screen-mediated technology for an average of 2 h and 19 min per day—about one third of that time on a mobile device—and nearly all these children’s households (98%) had a mobile device in the home.

Adolescents in the United States are on their smartphone or other screen devices a whopping average of 9 h daily, and that does not include time spent on homework or other school-related uses (Common Sense Census: Rideout, Citation2015). Another survey conducted in the United States showed that 82% of high school students and 66% of middle school students use smartphones daily or almost daily (Harris Interactive, Citation2015). Most relevant to mental health issues, adolescents are using their devices primarily for social interaction: In the United States, 89% of adolescents are members of at least one social networking site and the majority (71%) belong to more than one (Lenhart, Citation2015). These statistics are not constrained to affluent families based exclusively in Western countries: Russia leads mobile subscriptions worldwide, Asia is in lockstep with Europe, and many parts of Africa also have similarly high rates of mobile technology use (World Bank Group, Citation2018). Moreover, very frequent mobile use is not related to socioeconomic status, at least not in any linear way (Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, Cortesi, & Gasser, Citation2013).

Over the last decade, hundreds of studies have been conducted on the impact of “screen time” providing data for a number of recently published reviews and meta-analyses (e.g. Dickson et al., Citation2019; Elhai, Dvorak, Levine, & Hall, Citation2017; Hilgard, Engelhardt, & Rouder, Citation2017; Marchant et al., Citation2017; Marino, Gini, Vieno, & Spada, Citation2018; Mathur & VanderWeele, Citation2019; Prescott, Sargent, & Hull, Citation2018; Whitlock & Masur, Citation2019). However, these studies often come to polar opposite conclusions. Some studies show small relations between different types of screen time (e.g. social media, video games) and negative mental health outcomes (Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker, & Sacker, Citation2018; Mathur & VanderWeele, Citation2019; Twenge & Campbell, Citation2019; Twenge, Joiner, Rogers, & Martin, Citation2018; Twenge, Martin, & Campbell, Citation2018), whereas others find either a positive or no association (Berryman, Ferguson, & Negy, Citation2018; Hilgard, Engelhardt, & Rouder, Citation2017; Kardefelt-Winther, Citation2017; Orben & Przybylski, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Przybylski & Weinstein, Citation2017). In addition, some longitudinal work shows negative effects of screen time on mental health outcomes over time (Babic et al., Citation2017; Boers, Afzali, Newton, & Conrod, Citation2019; Booker, Kelly, & Sacker, Citation2018; Kim, Citation2017; Prescott et al., Citation2018; Riehm et al., Citation2019; Viner et al., Citation2019), whereas other studies show little or no effect (Coyne, Rogers, Zurcher, Stockdale, & Booth, Citation2020; Ferguson, Citation2019; Ferguson & Wang, Citation2019; Heffer et al., Citation2019; Hilgard, Engelhardt, & Rouder, Citation2017; Jensen, George, Russell, & Odgers, Citation2019; Orben, Dienlin, & Przybylski, Citation2019; Rozgonjuk, Levine, Hall, & Elhai et al., Citation2018).

Both sides of the debate have critiqued each other, highlighting methodological and statistical limitations (e.g. Drummond & Sauer, Citation2019; Ellis, Citation2019; Ellis, Davidson, Shaw, & Geyer, Citation2019; Heffer et al., Citation2019; Hilgard, Engelhardt, & Rouder, Citation2017; Kardefelt-Winther, Citation2017; Markey & Ferguson, Citation2017; Ophir, Lipshits-Braziler, & Rosenberg, Citation2020; Orben & Przybylski, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Twenge & Campbell, Citation2019). Specifically, the bulk of this research used self-report measures that were either poorly related or completely unrelated to actual screen use (Ellis, Citation2019; Ellis et al., Citation2019; Sewall, Rosen, & Bear, Citation2019), rendering most of the conclusions about the negative impact of screen time completely moot. Furthermore, most of the studies are correlational, providing no information about the direction of causation, and the large datasets used to yield effects are susceptible to false positives (Aalbers, McNally, Heeren, de Wit, & Fried, Citation2019; Drummond & Sauer, Citation2019; Elhai et al., Citation2018; Orben & Przybylski, Citation2019a). The most recent research has aimed at addressing many of these limitations with new methods, novel analytic techniques, pre-registration of hypotheses, and multiple measures of screen use. The findings revealed that there are at most very small relations between mental health and screen use and that these effects are often bidirectional (Berryman et al., Citation2018; Elhai et al., Citation2018; Ferguson & Wang, Citation2019; Heffer et al., Citation2019; Hilgard, Engelhardt, & Rouder, Citation2017; Jensen et al., Citation2019; Markey & Ferguson, Citation2017; Orben & Przybylski, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Orben et al., Citation2019). These weak and inconsistent findings are understandable, given that screen time is such a broad and vague concept.

Digital media are designed to serve many different functions: socializing, working, building relationships, as well as playing and being entertained. Instead of simple frequency counts on different devices and applications, what we need to examine is how the function of digital media relates to mental health. Specifically, we seek to understand the impact of different features of digital media and individual differences in their use, in relation to identity development, the core developmental task of adolescence.

In the following sections, we begin by reviewing some of the basic premises of the identity development framework and provide some examples of studies that have demonstrated its importance in understanding adolescent mental health. After each of the main principles of the framework is presented, we discuss its relevance for digital contexts. Most of the ideas that are presented in these “relevance” sections are necessarily speculative because so little research on the impact of digital media has taken an identity development lens. Nevertheless, where possible, we review extant data and adjacent research that is consistent with our proposed implications. Then, in the final section, we propose a new research agenda that can address the varied gaps we identify throughout the article.

Identity Development in Adolescence

Following Erikson (Citation1950, Citation1959, Citation1968), we start with the premise that identity development is the core task toward which adolescents devote their emotional, cognitive, social, and behavioral efforts. Childhood and early adolescence are characterized by identification with the values and beliefs endorsed by family and, increasingly, peers (Steinberg, Citation1990). Peer acceptance and the need to fit into a valued peer group are of paramount importance during adolescence (Brechwald & Prinstein, Citation2011; Brown, Citation2004). However, from around mid-adolescence (i.e., 14 years of age), individuals begin to challenge the beliefs endorsed by their social network and to reflect on the extent to which their own interests and values match those of their peers and parents (Collins & Steinberg, Citation2006; Steinberg & Monahan, Citation2007). Across diverse ethnic groups and for both males and females, data show that resistance to peer influences increases linearly from 14 to 18 years of age (Steinberg & Monahan, Citation2007). Thus, mid-adolescence constitutes a developmental phase during which young people learn to stand up for their own values and beliefs and resist changing them in the face of peers who pressure them to do otherwise. Eventually, adolescents integrate their reflected-upon values and beliefs with those that their social group and society present to them. This integration of self and societal values constitutes the foundation of adolescent identity formation (Erikson, Citation1968). Studies have shown that adolescents who successfully form new commitments after active self-exploration are psychologically healthier than those who fail to do so (for review, see Meeus, Iedema, Helsen, & Vollebergh, Citation1999).

The process by which young people make sense of their life events, share them with valued social partners, connect them to their values and commitments, and integrate them with societal values is a constructive act of building a life story. A number of psychologists have suggested that identity itself is constituted by this integrated life story, often referred to as narrative identity (McAdams & McLean, Citation2013; McAdams & Pals, Citation2006; Singer, Citation2004). Across every culture that has been studied (Bruner, Citation1986; Sarbin, Citation1986), individuals fundamentally understand their identity as a narrative unfolding over time (Polkinghorne, Citation1988); they are preoccupied with telling their life stories, recruiting feedback about those stories, and hearing those of others. Although elements of autobiographical memory and life stories begin to form in childhood, the arc of narrative identity only emerges in adolescence, with the advent of cause-effect abstract reasoning skills, problem-resolution linkages, and structural thinking (for review, see Nelson & Fivush, Citation2020). Narrative identity is built by connecting life events through causal reasoning, attributing meaning to past memories, stitching that meaning to present circumstances, and projecting to future plans, goals, and aspirations (McAdams, Citation1995; McAdams & Pals, Citation2006; Singer, Citation2004). As such, narrative identity is not a direct read-out of memory; it is a constructed story told (and retold) with emotionally curated memories, changing over the course of development as some memories become less salient and relevant and others more so.

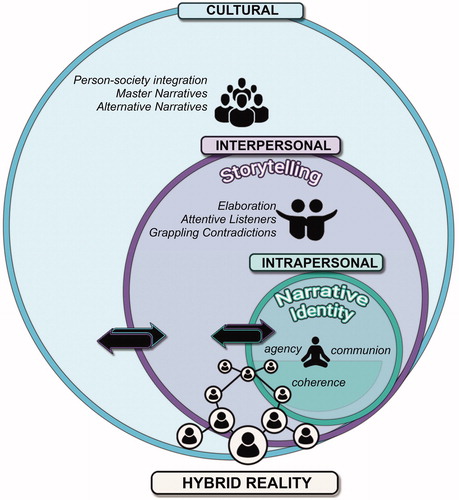

There are three levels of factors that interact to affect identity development in general and narrative identity in particular (). We describe these levels in separate sections, but it is important to note at the outset that these levels are always interactive and mutually constituted. For example, an adolescent’s sense of agency, a factor we describe as “intrapersonal,” is constrained very early in development by interpersonal influences such as parental controls and peer storytelling processes, which in turn, are largely shaped by cultural norms and values. First, there are intrapersonal factors, which are processes that operate within individuals and drive them to imbue their narrative identities with purpose and coherence. We specifically focus on two key factors: agency and communion, and the balance of the two for optimal development. Second, there are interpersonal factors, which influence how narrative identities are shaped and shared during social interactions. Specifically, we discuss the characteristics of storytelling partners and how they influence the extent to which narrative identities are elaborated, attended to, reinforced, and changed. Finally, there are cultural factors which determine the ease with which individuals can construct narrative identities that fit with their societal context and authentically integrate personal and societal values. For these, we cover societal norms and values (i.e. master narratives) and alternative narratives that may provide some individuals with a better fit to their personal values. Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and cultural factors are always interacting through feedback processes that create the foundation from which narrative identity is built, iterated, and transformed.

Figure 1. Narrative identity model, with embedded factors at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and cultural levels.

summarizes the narrative identity framework by means of a functional model that contextualizes the impact of digital spaces on adolescent mental health. We think of hybrid reality (the developmental ecosystem that seamlessly combines digital and physical worlds) as crossing all three of these levels. We propose that those digital contexts that support or amplify identity-relevant processes over development will be most likely to promote resilient mental health outcomes. Conversely, digital contexts that disrupt or poorly direct these processes will contribute to the development of mental health problems.

Intrapersonal Factors in Identity Development

In childhood and early adolescence, people identify with and conform rigidly to social expectations and beliefs: the need to be socially accepted and to belong (i.e. communion needs) takes precedence over other psychological needs. However, around mid-adolescence, self-exploration becomes a key element of identity development. Adolescents stop conforming rigidly to social expectations and beliefs and start reflecting on and acting in accordance with their own personal interests and values: personal agency becomes increasingly important to assert. Eventually, as young people mature over the course of adolescence and into early adulthood, agency and communion needs come to be valued equally, with the goal of achieving relative balance between them (Angyal, Citation1965; Adams & Marshall, Citation1996; Lichtwarck-Aschoff, van Geert, Bosma, & Kunnen, Citation2008). Below we discuss these processes in more detail. We then go on to demonstrate how these intrapersonal identity processes are actualized or potentially thwarted in a variety of digital contexts.

Communion

Communion needs (often referred to interchangeably as connectedness, belonging, or acceptance) encompass emotional bonding, being cared for and caring for others, and belonging to a socially cohesive group or community (for review, see Dweck, Citation2017; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). In early adolescence, the need to belong and be accepted by peers is of paramount importance and similarity in attitudes and behaviors among peers increases, explained by both selection and influence processes (e.g. Brechwald & Prinstein, Citation2011; Hogg & Reid, Citation2006; Prinstein & Giletta, Citation2016). The core mechanism by which people gain approval from others is through social learning. Values, beliefs, and goals that are most often rewarded by acceptance and increased status are those that will more likely be rehearsed, internalized, and come to be personally identified with during early adolescence (e.g. Deutsch & Gerard, Citation1955; Dishion & Snyder, Citation2016; Dishion & Tipsord, Citation2011; Festinger, Citation1950). There are serious emotional and mental health consequences for youth who fail to join peer groups and make close friends. Past research on young people who do not emotionally connect with peers has shown increased levels of rejection, loss of status, victimization, and loneliness (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Granic & Patterson, Citation2006; Juvonen & Galván, Citation2009; Sentse, Scholte, Salmivalli, & Voeten, Citation2007).

Communion needs translate into identity narratives that focus on themes of social connection (or rejection), belongingness, and care. Young people’s identity narratives tell the story of their developing self by the types of cliques or subgroups they belong to (e.g. geeks, jocks, goths), specifying their social status among their peer group, and elaborating on values and characteristics that are important in friends and romantic partners. Accordingly, communion is one of the most common themes found in narrative identities associated with mental health and wellbeing (McAdams, Citation1985).

Agency

Agency is the need to assert oneself and make decisions based on personal interests and values (Locke, Citation2015). After the early-adolescence stage of conformity (e.g. Deutsch & Gerard, Citation1955; Dishion & Snyder, Citation2016; Dishion & Tipsord, Citation2011; Festinger, Citation1950), mid-adolescence ushers in a period that prioritizes the need for personal agency. Youth become preoccupied with developing their own perspective and start acting more in accordance with their own interests and values (Erikson, Citation1968; Kroger, Martinussen, & Marcia, Citation2010). Adolescents’ sense of agency can be constructed from coping with a broad range of experiences, both positive and negative (e.g., academic achievement, athletic competencies, parental divorce, rejection by popular peers), and a strong sense of agency provides youth with the hope and motivation to overcome current and future adversities (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). In contrast, adolescents who fail to engage in self-exploration, remain fixated on conforming, or do not develop coping strategies that give rise to a strong sense of agency, seem to stagnate in their identity development, and subsequent mental health problems emerge. Protracted conformity to others’ expectations is associated with anxiety, depression, and lower psychological wellbeing in general (e.g. Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Rogers, Citation1961; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000).

As people transition from rigid conformity to more self-determined values, beliefs, and behaviors, this change is expressed in a concomitant maturing narrative identity. Specifically, healthy development in adolescence is characterized by an increasing frequency of agentic themes in narrative identities (McAdams, Hoffman, Day, & Mansfield, Citation1996). Narrative identities with agentic themes are stories in which the protagonist achieves influence over difficult life choices, has personal power in relationships and important social environments, and acts according to personal interests and values (e.g. “I need to end this friendship because it’s making me miserable”; “I hate school and I plan to drop out and join a rock band”). Particularly during challenging transitions (e.g. school or career transitions, coming-out experiences for gay and lesbian youth, psychotherapy), strong agentic themes expressed in personal narratives predict a range of positive mental health outcomes (e.g. Adler, Citation2012; Adler & McAdams, Citation2007; Adler, Skalina, & McAdams, Citation2008; Bauer & McAdams, Citation2004; King & Smith, Citation2004).

Further, agency themes are most often expressed in the form of redemptive sequences in narrative identities (McAdams, Reynolds, Lewis, Patten, & Bowman, Citation2001). Redemption narratives involve the casting of emotionally painful scenes or experiences into a more positive light by highlighting lessons learned or positive reattributions. Setbacks are reappraised as challenges that were personally overcome such that the initial “negative” event is transformed by an overall “better” outcome (e.g. King & Hicks, Citation2007; Lilgendahl & McAdams, Citation2011; Tavernier & Willoughby, Citation2012). One common redemptive narrative may develop when older adolescents begin to understand their previous stage of rigid conformity to peer pressures as a problematic phase through which they struggled, but eventually emerged, with a stronger sense of authentic values, beliefs, and goals. Individuals who fashion narrative identities with redemption sequences exhibit fewer mental health concerns and higher levels of wellbeing overall (Hammack, Citation2011; McAdams & McLean, Citation2013). For example, Adler et al. (Citation2015) have shown that people who tell self-narratives with more redemptive sequences have better psychotherapy outcomes, including fewer depressive feelings after several years.

In contrast, if the mid-adolescence transition goes awry, it may give rise to narratives with a contamination theme, highlighting failures in agency. These narratives focus on episodes that start positive and progress to an emotionally negative or harsh ending, remaining appraised as hopeless (McAdams et al., Citation2001). Contamination themes in narrative identities are characterized by feelings of hopelessness, the failure to persevere (Mathews & MacLeod, Citation2005), and rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, Citation2008) and they commonly correspond with both anxious and depressed outcomes. When young people cannot tell the story of their life in a way that emphasizes their abilities to overcome challenges and to persevere even through the darkest moments, they end up with helpless and hopeless narratives, making it exceedingly difficult to construct further iterations of an identity narrative that points to a future worth living (Ball & Chandler, Citation1989; Boyes & Chandler, Citation1992; Chandler, Citation1994a, Citation1994b; Chandler & Lalonde, Citation1994; Noam, Chandler, & Lalonde, Citation1995).

Coherence

We have discussed agency and communion as core intrapersonal needs in identity development. Agency goals drive one to overcome obstacles to pursue what one finds personally meaningful. Communion goals drive one to belong to a social group and share a common purpose and values with others. However, a further, essential challenge of adolescent identity development is to balance the two needs, that is, to pursue what one finds personally meaningful and to also feel accepted and supported by peers and society more broadly (Adams & Marshall, Citation1996; Erikson, Citation1950, Citation1968; Bosma & Kunnen, Citation2001; Locke, Citation2015). Balancing agency and communion needs is particularly challenging during adolescence (e.g. Chandler, Citation1994a, Citation1994b; Chandler & Lalonde, Citation1994; Erikson, Citation1968; Fivush, Citation2011; Habermas & Bluck, Citation2000; Kroger & Marcia, Citation2011), given the myriad biological and social changes associated with this phase. Moreover, adolescents are attempting to transcend a group identity that is highly conspicuous (e.g. geeks, goths, popular kids) making it more challenging to establish a sense of self that honors personal values as well (Erikson, Citation1968; McAdams, Citation1985; Steinberg & Monahan, Citation2007).

One way to conceptualize the communion-agency balancing process is to think of it as constituting a third core intrapersonal factor in narrative identity development: temporal narrative coherence. A temporally coherent narrative is defined as a causally connected, temporally meaningful story of the evolution of the self and it has long been considered a basic psychological need (e.g. Erikson, Citation1968; Steele, Citation1988). The building of a temporally coherent narrative drives one to incorporate personal values and beliefs with diverse social roles and relationships, in order to derive one global story of the self. This identity narrative articulates how the self has both changed over the course of development but also remained essentially, in some important ways, the same (Syed & McLean, Citation2016; Worthman, Plotsky, Schechter, & Cummings, Citation2010). Specifically, the old self that was identified with family and peer norms and values is linked with the present self that integrates personal and societal values, and projects forward into a story of the future self that will express and fulfill the integrated values.

A host of studies show that high levels of temporal narrative coherence are linked to a range of positive outcomes (e.g. Adler, Wagner, & McAdams, Citation2007; Baerger & McAdams, Citation1999; Cohen, Garcia, Apfel, & Master, Citation2006; Lysaker et al., Citation2005), and increases in narrative coherence over the course of interventions likewise predict improvements in mental health (Foa, Molnar, & Cashman, Citation1995; Lysaker et al., Citation2005; Van Minnen, Wessel, Dijkstra, & Roelofs, Citation2002). Narrative coherence is so essential to wellbeing that, without it, some vulnerable young people are quite literally unable to go on living. A series of clinical studies have shown that suicidal adolescents, compared to psychiatric control patients who are non-suicidal, are uniquely characterized by their inability to tell a causally coherent life narrative and to temporally link a future self with past and present versions of the self (Ball & Chandler, Citation1989; Boyes & Chandler, Citation1992; Chandler, Citation1994a, Citation1994b; Chandler & Lalonde, Citation1994; Noam et al., Citation1995).

Relevance of Digital Contexts for Intrapersonal Processes

We have shown that communion, agency, and coherence are crucial intrapersonal factors in adolescent identity development. Whether these factors are supported or suppressed in digital contexts likely depends on the design of these contexts as well as individual differences in how they are approached and experienced. In the following, we discuss various design features and common use patterns of two of the most popular types of digital media for adolescents, video games and social media, and we articulate their likely implications for identity development processes.

Communion

There is a great deal of potential for digital experiences to meet or frustrate communion goals, thus impacting on narrative identity development in adolescence. Perhaps the most obvious means by which digital technology supports and guides communion needs involves the near-ubiquitous use of social media such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. As previously reviewed, the vast majority of young people across diverse cultures use social media daily (e.g. 89% of American adolescents are members of at least one social networking site; Lenhart, Citation2015). “Friending,” sharing thoughts and images, and identifying, molding, and reiterating positive relationships all enhance a sense of connection with others through platforms that were explicitly designed for that purpose. Adolescents explicitly build and curate well-defined, well-ordered networks of peer relationships in their social media spaces, thus reifying a web of connectedness that is far more elaborate and extensive than they might have realized without these digital infrastructures (Lenhart, Citation2015; Madden, Lenhart, Cortesi, et al., Citation2013).

In the last few years, much attention has been paid to the unique affordances of social media for amplifying or changing perceptions of communion and social connection (Ehrenreich & Underwood, Citation2016; Nesi, Choukas-Bradley, & Prinstein, Citation2018). The vast majority of this research has focused on the negative impact that may come from navigating these social contexts. For instance, associations have been found between social comparison, envy, and depression for people using Facebook (Appel, Gerlach, & Crusius, 2016) and feelings of anxiety relate to individuals trying to keep up with posting across diverse digital spaces and feeling like they are missing out on activities highlighted in social media (Przybylski, Murayama, DeHaan, & Gladwell, Citation2013). But there is also evidence of positive influences. For example, young people who express themselves authentically to their peers, meeting their communion needs through honest communication on social media, show higher levels of psychological wellbeing over longitudinal time (Reinecke & Trepte, 2014). What is becoming clear from this early research is that the same social media mechanisms can lead to both heightened and compromised perceptions of communion, depending on the design of the platforms and individual differences in their use. The conditions under which communion is enhanced versus usurped, however, needs to be addressed in far more systematic, longitudinal work.

What is perhaps less obvious is the way in which video games serve communion needs. Playing video games among adolescents has become a ubiquitous activity, with 97% of boys and 83% of girls playing these games regularly (Anderson & Jiang, Citation2018); the vast majority of this play (more than 75%) is social in nature (Lenhart, Citation2015). Online social video games seem to be an important means by which communion needs are being met in the current digital age. Contrary to concerns about the violent or simply mundane content being communicated in these games, evidence shows that young people predominantly share socioemotional messages when they play these games (Peña & Hancock, Citation2006). Moreover, the large majority of this socioemotional content is positively valenced (e.g. “you’re doing great,” “Thanks for your help,” “How did you learn that?”), despite common gaming goals of fighting or winning.

In addition to conventional online games that are often about fighting and are competitive in nature, there are new and influential social and cooperative video games that are becoming increasingly popular. Intense competitive challenges do not motivate everyone with feelings of connection or social rewards (Yee, Citation2017). Studies suggest that a large segment of the population, particularly individuals who identify with more feminine characteristics, find competitive, frustrating games (and social media contexts) boring or even aversive (e.g. Tondello, Wehbe, Orji, Ribeiro, & Nacke, Citation2017; Yee, Citation2017). For this group, the best suited games and social media provide opportunities for self-exploration and pursuit of communion needs by making friends, cultivating community, and taking care of others—a pattern most often referred to as “tend-and-befriend” in the biopsychosocial literature (Taylor et al., Citation2000). Thus, some of the most emotionally powerful games may provide experiences that allow users to experience communion in ways that were not available before the digital era.

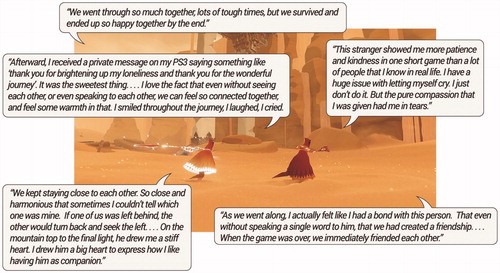

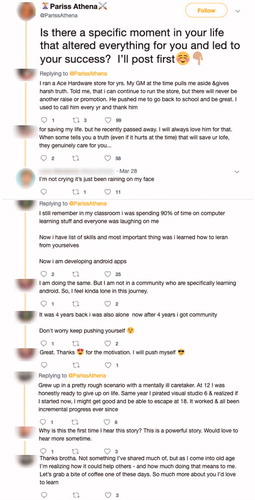

One of the most compelling examples is the Sony Playstation3 video game Journey (Thatgamecompany, Citation2012), the fastest selling video game in 2013 (Parker, Citation2013). Because of its uniquely emotional social gameplay, we have selected this game to exemplify its potential to contribute to communion goals, but it is also relevant to fostering feelings of agency. Journey is a beautifully rendered, nonviolent social video game that promotes non-verbal communication through musical tones and symbolic cooperative play. The game guides players through an emotionally evocative, musically symphonic, redemptive narrative that is explicitly designed to enhance feelings of communion with other players. The tight constraints on the story arc of the game ensure that it ends in a redemptive climax that provides the player with supportive co-players who share at least part of their journey (e.g. players have the opportunity to help, encourage, and care for or be cared for by others in a collaborative interaction that facilitates game enjoyment). Upon finishing the game, players often share elaborate identity narratives () about how the play experience resonated with their relationships offline: how playing the game inspired them to think differently about their own relationships and how communion needs felt met in unique and surprisingly relevant ways. There are thousands of these stories in online forums (Journey Stories, Citationn.d.; see for examples, and read others here: https://journeystories.tumblr.com/).

Figure 2. Quotes from players after they played Journey, collected from a public forum set up to share people’s narratives after finishing the game (https://journeystories.tumblr.com).

Agency

In the past decade, media scholars and game theorists (Boyd, Citation2010; McGonigal, 2012; for review, see Granic, Lobel, & Engels, Citation2014) have called attention to the capacity for digital games to build young people’s agency through mechanisms such as training persistence in the face of failure. Moreover, most video games attract users by the opportunity to prevail, to win over opponents, to single-handedly overcome challenges and so forth. Many video games use intermittent reinforcement schedules for rewarding small gains that eventually grow toward large-scale successes; immersion in these gaming contexts may provide regular experiences that show youth that persistence in the face of an obstacle reaps valued rewards (Ventura, Shute, & Zhao, Citation2013). One of the most common narrative tools used in conjunction with these intermittent reward schedules is a “hero’s journey” tale that links each of the micro-successes in the game to larger-scale stories of redemption (McGonigal, 2015). McGonigal summarized how games impact on players’ agency and optimism: “A game is an opportunity to focus our energy, with relentless optimism, at something we’re good at (or getting better at and enjoy). In other words, gameplay is the direct emotional opposite of depression” (2012, p. 28).

Related to the sense of relentless optimism is the motivational “sweet spot” which most good video games target, where challenge and frustration are balanced with eventual success and accomplishment (Sweetser & Wyeth, Citation2005). For those motivated by challenge, frustration, and mastery, daily experiences with these digital training regimens seem to build a “growth mindset” (Dweck & Molden, Citation2005; see Granic et al., Citation2014 for review), essentially a mindset that has agency and redemption at its core. Although there are no empirical studies that have yet linked playing video games to specific agency themes in identity development, research has demonstrated that this growth mindset predicts positive outcomes such as better academic performance and improvements in mental health (e.g. Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, Citation2007; Schleider, Abel, & Weisz, Citation2015; Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018).

Interestingly, a new wave of video games not only guide the player through redemptive narratives but do so with a storyline that focuses explicitly on mental health challenges. These are not the “serious games” designed by academics and largely ignored by the public. These are games that are garnering wide-scale critical acclaim on the commercial market and making hundreds of millions of dollars in sales. For digital natives, these games can be likened to the “self help” books of the past, with the added advantage interactivity provides. Celeste (Matt Makes Games, Citation2018; http://www.celestegame.com/) is a particularly interesting example of a game aimed to help players experience increases in agency, through perseverance and explicit confrontation with psychological challenges. The game is designed to be virtually impossible to “beat” and the player is a character that struggles with anxiety and depression. Despite constant, ominous warnings and offers from others to help her, the protagonist wants to climb Celeste Mountain on her own. She is harassed by a dark shadow representing her own inner critical self, who whispers condemnations, insists she will fail, and councils her to stop trying. Eventually, after the player “dies” repeatedly, the summit is reached and there is an inexplicably powerful feeling that something real and emotionally harrowing has indeed been achieved. There are hundreds of stories in online forums (e.g., https://www.reddit.com/r/NintendoSwitch/comments/a5ff8d/celeste_is_helping_me_cope_with_alcoholism/) detailing how young people identify with the character in Celeste and her redemptive struggle to overcome her harsh, internal voices to eventually succeed. This kind of game may foster a general sense of agency and provide a scaffolded redemptive narrative onto which adolescents can transfer their own struggles.

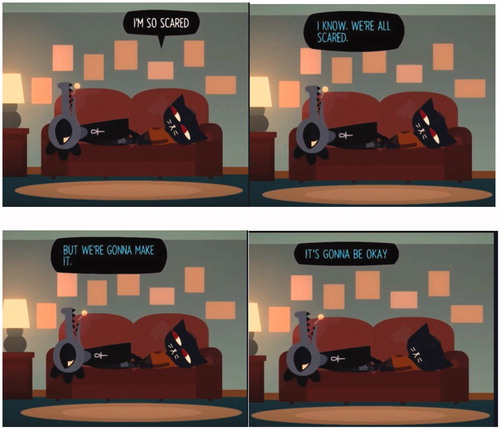

Another example is Night in the Woods (Infinite Fall, Citation2017; http://www.nightinthewoods.com/), a game in which you play a 20-year-old college sophomore dropout returning to her old town. The game gently (yet with appropriately scathing humor) guides the player to understand the importance of taking responsibility for one’s actions, going through inevitable emotional suffering, leaning on kind friendships, and reaching out for social support when the suffering seems overwhelming. shows a series of screen shots that reinforce the real-world relevance of redemptive narrative themes. One reviewer summarized its lessons: “… playing it forced me to think about what an adult is…” (Moore, Citation2018). These types of games have just been released in the last few years, and research on their impact necessarily lags, particularly with respect to functional questions regarding narrative identity. But given their explicit design goals—to foster agency in terms of a redemptive narrative—there are compelling therapeutic potentials to explore.

As already described in relation to communion needs, social media provide conspicuous digital contexts impacting on adolescent identity development. However, not only do social media serve communion goals but they also provide opportunities to assert agency and build identity narratives with redemptive themes. In general, social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok have several design features that may support the development of agentive themes in narrative identity. For example, all social media allow adolescents to freely express their personal likes, dislikes, and values through posts, photos, videos, or literal self “stories” (i.e. Instagram “stories”; Madden, Lenhart, Cortesi, et al., Citation2013). Features such as Facebook’s photo albums and its enabling long posts and threads with videos (e.g., Humans of New York: https://www.facebook.com/humansofnewyork/) and SnapChat Stories provide opportunities for individuals to tell their redemptive narratives in ways that highlight both struggles and eventual accomplishments. But it is important to note that designers of social media have overwhelmingly been focused on creating features that help people build social relations and social networks; in other words, they have aimed to design communion-oriented spaces. This design focus at times may have undermined young people’s needs for agency in these digital contexts.

More recently, there have been explicit initiatives to foster increases in feelings of agency on social media. For example, Instagram recently deployed a new feature, in part to address feelings of wariness and anxiety that users had with the lack of control and the enforced permanence of their posts (Johnston, Citation2016; O'Donnell, Citation2018; Wagner, Citation2018). Specifically, “Instagram Stories” were developed to allow people to post a series of photos and comments, often in the explicit form of identity narratives, but these “stories” disappear permanently after 24 h. This new design feature has resulted in people increasing their use of the social media platform, likely because they feel more agency posting their identity-relevant content without undue vulnerability to the permanence of their public posts.

Snapchat, one of the most popular social media apps for teenagers, is also designed with the impermanence of pictures as a core feature. This ability to share uncurated moments with friends knowing that traces of these moments will disappear was the main reason it skyrocketed as one of the most used social media app among teenagers, with 203 million daily users worldwide as of March, 2019 (Bell, Citation2019). Whether Instagram stories and Snapchat features that are explicitly designed to erase social media content actually increase users’ sense of agency has yet to be studied. However, clearly new areas of research are suggested by considering the promotion of agency themes in digital experiences that were primarily designed to promote communion goals.

Of course, it is also important to consider usage patterns and design features of social media that can undermine young people’s agency. In a recent national survey conducted in the United States, adolescents reported often feeling less agency than they would like in posting personal content on social media sites, indicating that they felt pressure to post only what others would approve of (Lenhart, Citation2015). In a systematic review by Twomey and O’Reilly (Citation2017) studies showed individuals who were not able to authentically present themselves on Facebook reported lower self-esteem and elevated levels of social anxiety. Thus, being able to share an agentic and authentic story about the self in digital spaces seems important for one’s self-esteem despite vulnerability to social disapproval (Twomey & O’Reilly, Citation2017).

Part of the concern in terms of agency in digital spaces is that there is fierce competition among singular, disparate digital applications, platforms, and games, all vying for young people’s attention and digital participation. Each of these apps or platforms attempts to distinguish itself by highlighting different norms, values, and etiquette (e.g. some dating apps such as Tinder emphasize physical appearance and casual “hookups” while others such as Match pull for people seeking marriage and long-term relationships). When young people move among multiple digital spaces that appeal to, and incentivize, diverse representations, these are also reflected back to them. Without an opportunity for self-reflection, this multiplicity of social values and norms presented on digital platforms may undermine agency goals by making commitment to personal values difficult. Indeed, such abundance of choices may lead to paralysis or ruminative exploration (Beyers & Luyckx, Citation2016; Schwartz, Citation2000).

The issue of censorship on social media has also been a particularly thorny one. Social media platforms often delete posts that are not compatible with their ideological views, restricting individuals’ agency and self-exploration. Furthermore, digital platforms seem to be intentionally designed to mislead youth about privacy, confidentiality, and the extent of actual control over personal data. Questionable privacy practices associated with platforms like Facebook and Google dramatically change the stakes for young people when it comes to control over their own narrative identities (Livingstone, Citation2008; Livingstone, Ólafsson, & Staksrud, Citation2011; Livingstone & Third, Citation2017). In previous generations, adolescents also experimented with their identity, sometimes making themselves look foolish and behaving in antisocial or embarrassing ways. Yet those indiscretions were largely left behind and people could outgrow and “forget” their teenage misbehaviors (Eichhorn, Citation2019). In the current age, digital manifestations of our former selves are strewn all over the internet, likely never to be erased (e.g. Facebook photos; Twitter tirades). These platforms may usurp young people’s abilities to edit or erase former self-narratives (Eichhorn, Citation2019). Healthy development requires that narrative identities remain malleable and under the authorship of the individual; thus, we need to carefully consider young people’s power to choose how to present their personal narratives publicly, and the various constraints on that power. How to study these constraints across a wide variety of digital spaces remains an important question, one which we pick up again at the end of this article.

Coherence

We propose that one of the most significant ways in which the digital world is impacting on young people is by either supporting or threatening the balance between communion and agency needs and the emergent temporal coherence of narrative identities. Social media platforms contain features that can support as well as compromise these processes. Our technologies have been cobbled together in silos, mostly incentivized by profit and the singular agenda of capturing the largest user base possible. As a result, there is a massive number of digital spaces in which young people act and interact and individuals’ experiences with the array of digital spaces may result in feelings of self-fragmentation and a lack of temporal narrative coherence. For example, the current generation of young people have been engaged with diverse social media and gaming forums for well over a decade. They have likely left a variety of identity-relevant texts, photos, videos, and other forms of self-artifacts across a range of digital spaces from around mid-adolescence until early adulthood. However, there is currently no way to synthesize, order, collect, or edit these various self-artifacts across the digital ecosystem. The extent to which young people can pull together the shards of their self-presentations may be critical for understanding the impact of digital participation on the temporal coherence of narrative identities.

In terms of temporal coherence, how might digital spaces help or hinder the synthesis of disparate self-representations across different ages? Media experiences that encourage users to pull the shards of their chronologically distributed selves together into a temporally coherent self-story seem missing from the current digital ecosystem. For example, with their “On this Day” feature, Facebook regularly encourages users to redistribute old “memories” encapsulated in photos or videos from as far in the past as 10 years. At present, the resurfacing of these old posts lands directly at the top of the user’s current timeline and this resurfacing is simply designed to incentivize spending more time on the platform and sharing content quickly and frequently (Perez, Citation2017). But there are interesting ways in which this feature can be slightly modified to foster an integrated, temporally coherent self-narrative which can be subsequently shared with friends and family. For instance, because these old posts are presented by the Facebook server unexpectedly, these memories may trigger strong emotional reactions. Future iterations of this design feature could include gentle prompts linked to the old post to reflect on how the self that posted those artifacts is the same, different, or causally related to the current self. This simple example of a design change to the original Facebook feature demonstrates how insights from theories on adolescent identity development could inform new iterations of social media design which could have a positive impact on narrative identity processes.

Related to the previous example, the impact of digital media on coherence processes is also likely to depend on the extent to which digital spaces allow for reflection. As mentioned earlier, a healthy balance between communion and agency needs in adolescence requires personal interests and values to guide and inform the social values that youth commit to. If adolescents spend the majority of their waking hours seeking affirmation and approval in social media contexts, it may be difficult to cultivate personal values and beliefs. Digital spaces that offer young people opportunities to step back from compulsive information sharing and, instead, incentivize solitary self-reflection may be particularly important for fostering narrative coherence.

In contrast to processes that facilitate self-reflection, current digital media seem to rely on an entirely different architecture for motivation. For example, most social media platforms at this point incentivize rapid feedback in the form of fast-changing content feeds that require quick responses such as “likes” and “retweets” (on Twitter), “likes” and “shares” (on Facebook), “uses,” “views,” and “swipes” (on Snapchat), and so on. The design decisions that lead to these one-click engagement vehicles constrain users to a few seconds at most between when they “consume” content and when they react to it. But these are, indeed, design decisions and different ones could be made, depending on the type of psychological experience that is most valued. Platforms could implement simple mechanics that, instead, incentivize reflection. For instance, posts on any of these social media platforms could be “blocked from response” for the first 15−60 min after someone first views the content. Alternatively, one-click “like” buttons and other indicators of performative popularity and adherence to social norms could be eliminated altogether and, instead, users could be constrained to interact with others’ posts only through comments. We return to the importance of providing space for reflection as we discuss social storytelling processes in the next section. What is clear is that these are propositions that have never been empirically tested, suggesting ample opportunities for informative new research designs.

Interpersonal Factors in Identity Development

Up to this point, we have discussed elements of identity development in terms of the individual’s personal engagement with digital media. In doing so, we have specified core intrapersonal needs, namely communion, agency, and coherence. But identity development is fundamentally social. In this section, we extend the notion that individuals need to feel like they are connected to others, that they belong to a group, that they share values and goals with peers, and that social partners are always coauthors of individual narrative identities. This means that interactions between the user and digital media ride on the powerful influence of social participation, both in terms of the design of the digital space and in terms of social interactants with whom they enter this space. To investigate these processes, we move now to understanding interpersonal factors.

As we have emphasized, our identity is, at its core, expressed and understood as a constantly evolving life story. The act of storytelling is essentially an interpersonal, social one: sharing our life stories is the means by which we develop our narrative identity. Our narrative identity, in turn, helps us form and maintain close relationships (Bluck & Alea, Citation2009). Close social bonds are the vehicles through which we rearticulate our narrative identity, reminding ourselves of who we are, what core values and goals we endorse, and why we are connected to the people we value.

Social storytelling impulses start early and are expressed frequently in everyday life, such that they become the backdrop of growing up. For example, in a study focused on analyzing conversations during family dinners, researchers found that small stories about the past were discussed about once every 5 min (Bohanek, Marin, Fivush, & Duke, Citation2006). In fact, across cultures and genders, 90% of emotional experiences are disclosed to other people shortly after they occur (Rime, Mesquita, Boca, & Philippot, Citation1991). This act of experiencing something and then telling stories about that experience is fundamental to how we build the architecture of the self. There are three main characteristics of storytelling partners that have been empirically linked to narrative identities: Elaboration, high quality listening, and time and space to grapple with identity paradoxes.

Elaboration

Stories of the self are seeded in parent-child conversations and they develop and become more sophisticated as parents prompt children for elaboration in characteristic ways (e.g. Fivush, 1991, 1993; Fivush, Haden, & Reese, Citation2006; McCabe & Peterson, Citation1991a; Newcombe & Reese, Citation2004). Specifically, parents who ask probing questions and make and elicit evaluative comments, while encouraging the child to express his or her point of view, are more likely to have children with coherent self-narratives built around personal agency (Fivush, 1991; McCabe & Peterson, Citation1991b). Elaboration processes encourage agentic themes by focusing on perceived causes and personal explanations of remembered events. Parental elaboration processes and children’s abilities to build their own self-narratives reinforce each other: Parents who request elaboration of self-stories encourage children to provide more sophisticated, emotionally rich narratives which, in turn, prompt parents to request further elaborations (Farrant & Reese, Citation2000; Fivush, Citation2011; Peterson, Jesso, & McCabe, Citation1999).

As children grow older, they require less and less prompting from parents to tell their self-stories (Fivush, Citation2011). By the time they reach adolescence, they become compelled to provide narrative evidence of causal turning points in their lives, and to share (and check) that meaning with others, especially their peers, glimpsing their own identity development as an unfolding autobiography that forms the basis for who they will become (McAdams, Citation2006; McAdams et al., Citation2001; McAdams & McLean, Citation2013; Pals, Citation2006). Importantly, around mid-adolescence, they gradually relinquish parents as their central narrative partners. Elaborating self-stories about their interests and fears, and detailing the sometimes unsavory trials of socializing in the schoolyard, risks boring adult listeners as well as inviting condescension, censure, parental lectures, and disciplinary reactions. Accordingly, once their peers are their primary narrative partners, adolescents are likely to turn to the internet for prompting and elaboration.

Quality of Listening

The quality of listening that peer partners exhibit during the expression of narrative identities is particularly important for promoting healthy development in adolescence. First, the intent of the listener matters. Peers who are willing and interested in listening to the personal meaning of self-stories, rather than being exclusively interested in being entertained, contribute to the building of a coherent narrative identity. Research shows that telling stories for the purpose of entertaining peers is less effective for developing integrative, coherent narratives than sharing stories of personal, emotional relevance (McLean, Citation2005). Second, it is critical that peer listeners are responsive; that is, peers who listen without distraction and are receptive to the details of the narrative identity being shared must also feedback their responses and interpretations in a way that can be easily perceived and integrated (e.g. Pasupathi & Hoyt, Citation2010). Finally, listeners who end by validating the interpretation of a young person’s self-narrative are crucial. Negotiation, clarification, and partial disagreements are useful, but when self-narratives are affirmed in the end and interpretations of personal stories are supported, storytelling contributes most to an agentive, coherent narrative identity (McAdams & McLean, Citation2013). In sum, starting in adolescence, there are increasing needs and opportunities to share self-narratives and to tell these stories in ways that capture peers’ attention and enliven social interactions. Attention to identity-relevant details and affirmation of the storyteller’s self-representations make for the most valuable narrative partners.

Time and Space to Grapple with Paradoxes and Contradictions

As adolescents increasingly understand societal norms and expectations, as they connect to larger social networks, and as they become exposed to diversity in the responses to their current self-narratives, they are forced to grapple with contradictions, paradoxes, and opposing worldviews. This grappling is necessitated when past and present representations of the self-come to contradict each other and when conflicts between the norms of different peer groups, societal demands, and self-representations cannot be easily reconciled (Campbell, Assanand, & Di Paula, Citation2003; Erikson, Citation1968; Marcia, Citation1966; Syed & McLean, Citation2016). Young people require grappling partners, peers, and larger group contexts that give youth permission and a safe space to navigate and struggle with these paradoxes and contradictions without losing the esteem of others (McAdams & McLean, Citation2013). Trusted and supportive peers who can bear narrative contradictions are essential for young people to eventually settle on narrative identities that feel authentic, honest, and generative.

Relevance of Digital Contexts for Interpersonal Processes

There seem to be unique affordances provided by digital spaces that transform and amplify storytelling processes relevant to identity development, including elaboration, quality of listening, and the time and space to grapple with identity-relevant paradoxes. It is likely that no app, game, or platform will uniformly promote or disrupt these processes. Instead, individual differences in how young people are engaging with video games and social media platforms seem critical to consider in relation to identity development as well as mental health. Active versus passive modes of engagement provide a clear example. And while the differential impacts of active versus passive engagement may be evident at the intrapersonal level, their relevance for interpersonal goals seems far more extensive. For example, a review by Verduyn, Ybarra, Résibois, Jonides, and Kross (Citation2017) showed that passively using social media provokes social comparisons and envy, whereas active usage of social media is related to creating social capital and stimulating feelings of social connectedness.

Elaboration

The opportunity for elaboration processes in social digital contexts is particularly complex. One of the most often cited criticisms of currently instantiated social media platforms is that they curtail deeper conversations because they are designed to amplify performative aspects of personal storytelling (e.g. Nesi, Choukas-Bradley, & Prinstein, Citation2018). For instance, platforms such as Snapchat, Instagram, and Twitter offer opportunities for short bursts of comments and mutual engagement, but oftentimes these platforms arrest attempts at elaboration and authentic discourse. We argue, however, that individual differences in the function of users’ engagement with these spaces will predict their impact on identity development and mental health. Despite some design constraints, many young users are finding their most thoughtful conversations and meaningful identity explorations in these social media contexts (Reid & Boyer, Citation2013; Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2008). For example, Facebook has been shown to create opportunities for elaborate discourse around beliefs and values and these online discussions empower individuals to actualize identities they hope for but are unable to consolidate in offline contexts (Zhao, Grasmuck, & Martin, Citation2008).

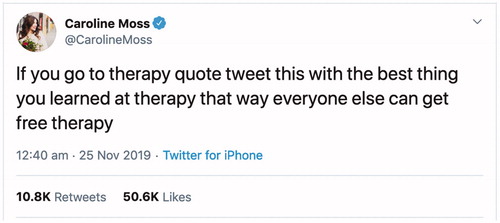

Instagram can be used to post cat gifs, travel photos, and airbrushed selfies exclusively; these types of posts are likely to elicit very few requests for elaboration on identity-relevant interpretations. However, the same Instagram platform is being used to connect with like-minded peers who share identity-relevant preferences such as musical interests, career aspirations, and hobbies (Subrahmanyam & Šmahel, Citation2011). Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter can also host meaningful discourses around career or education choices, political views, gender identity concerns, and mental health advice (e.g. Manikonda & De Choudhury, Citation2017). As just one example, a recent Twitter participant asked an online community of millions to share the most helpful advice they had received from their therapist, so that others could benefit from that intervention at no cost. As shown in , there was a massive response to the request, with over ten thousand replies, bids for elaboration, questions to help extend individual narratives, expressions of gratitude, and a tide of sharing sent out to various networks of users (for more concrete examples, see link to the online post in the figure caption). On the whole, these examples demonstrate how colleagues, friends, acquaintances, and even strangers may be prompted to provide precisely the kind of bids for elaboration we have identified as crucial for the development of healthy, coauthored narrative identities.

Figure 4. A recent tweet requesting therapeutic advice to be shared garnered many thousands of replies, requests for elaborations on advice, gratitude for various pieces of wisdom, as well as massive sharing (i.e. retweets and likes; https://twitter.com/CarolineMoss/status/1198748131556499456).

Quality of Listening

It seems beneficial for young people to use digital spaces to engage their friends and peers in identity-relevant meaning-making activities that go beyond pure entertainment. An open and interested quality of listening provides the necessary context. As one example, isolated and marginalized youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ+) may actively engage in social media communities to connect with other gender and sexual minority groups worldwide. Yet this can only benefit them if social support and authentically engaged listeners are available (McInroy, Citation2019; Ybarra, Mitchell, Palmer, & Reisner, Citation2015). Fortunately, social media sites and support forums such as the ones available on Redditt (e.g. https://www.reddit.com/r/mentalhealth/) attract active, engaged users committed to listen to and learn about like-minded peers (Fox & Ralston, Citation2016; Hatchel, Subrahmanyam, & Birkett, Citation2017).

Recently, market research on individual differences in the ways that users are engaging in digital spaces, and users’ requests for more opportunities to improve on the quality of identity expressions, have resulted in design changes to social media platforms.

For example, the ephemeral 24-h life cycle of Instagram Stories that we previously discussed may encourage more intimate, authentic identity expressions. The introduction of these Instagram Stories has caused a massive surge of private one-to-one messaging between users of the platform (Bernazzani, Citation2019). This rise in the more personal, dyadic form of communication suggests users are perceiving these Stories as indeed more intimate and valuing the opportunity to reach out to one another in a less performative way (i.e. they are not defining themselves for generic future viewers but connecting one-to-one instead). Research on these digitally instantiated storytelling processes is very much in its infancy, but it holds a great deal of promise, especially if we can link these narrative identity expressions to subsequent impacts on mental health.

Finally, a new generation of mostly independent game and app design companies are building intimate, prosocial experiences that are somewhere in between traditional video games and social media forums. These spaces encourage young people to specifically share their real-life self-stories in playful but compelling ways with a community of players doing likewise. For example, Kind Words (Popcannibal, Citation2019) is a game (loosely defined) in which players can write letters of support to online strangers (delivered by a playful set of characters) who request this emotional support for themselves, all to an engaging, mellow soundtrack aimed to facilitate connection among players in real time. Players most often share personal narratives, provide and receive support, kindness (and gratitude in return), and generally care for one another. These playful, personal communications help players cultivate a community that values personal storytelling, authentic self-exploration, and quality listening, leading to participants expressing kindness and validation that blurs the boundary of online and offline emotional experiences. (To read testimonials from hundreds of players, see https://store.steampowered.com/app/1070710/Kind_Words_lo_fi_chill_beats_to_write_to/.) Digital spaces with similar aims are rapidly emerging across the digital ecosystem, potentially providing users novel avenues for finding listening partners and engaging in social storytelling processes to amplify and facilitate identity development in ways that were not available before the digital era. Yet psychological scientists are not paying attention and studying them at this point.

Time and Space to Grapple with Paradoxes and Contradictions

Finally, there are myriad opportunities across digital spaces for young people to take the time and space to grapple with paradoxes relevant to their narrative identity. If adolescents socialize mostly with close peers and friends, digital platforms provide a unique zone, that is, time and space, for exploring what is particularly beneficial to them. This can be seen as a safe and private ecosystem where users can linger, browse, float from one type of activity to the next, and home in on what they deem to be most relevant, without being constrained by social pressures and prefabricated rules, curfews, or finish lines. This kind of safety, autonomy, and anonymity is uniquely attractive, and can be beneficial, compared with the loaded social environments of everyday life—the classroom, living room, dinner table, and school yard (Ehrenreich & Underwood, Citation2016).

For vulnerable adolescents in particular, social media and social role-playing video games can provide a way to opt out of the hierarchies of school life, allowing them to grapple with identity paradoxes with peers doing likewise. Paradoxes abound on the internet, and they are intentionally amplified, often in novel and appealing ways, so that users need to critically evaluate and debate about their beliefs and to experiment with different roles, competitors, genres, and rules. For example, theories of online disinhibition suggest that the online context may encourage individuals to more freely express their individual opinions and engage in more disinhibited behaviors than they might offline (for better, or worse, of course; Suler, Citation2004; Woong Yun & Park, Citation2011). Descriptive studies have also identified the benefits of rejected and lonely young people grappling with identity paradoxes online by engaging in “identity experiments”: pretending to be exaggerated versions of themselves, or taking on the identity of entirely different people (Michikyan, Subrahmanyam, & Dennis, Citation2014; Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2008). Data have shown that by taking control of their own narrative identity, grappling and experimenting with it, regardless of how accurate it may be, young people (especially lonely youth) can develop their social competence more broadly (Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2008).