Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this review paper is to summarize the challenges facing research on the alliance now and going forward. The review begins with a brief overview of the development of the concept of the alliance in historical context. Method: A summary of what has been accomplished both within the psychotherapy research community and in other professions is presented. Current challenges facing this line of research are identified, including the existence of a wide range of operational definitions that results in a diffusion of the identity of the alliance concept. It is argued that the current situation generates risks to incremental growth in several lines of research. Conclusions: A case is made that a lack of clarity regarding how several variables within the broader category of therapeutic relationships fit together, overlap, or complement each other is also potentially problematic. Efforts to resolve the lack of a consensual definition are reviewed, and in conclusion, it is argued that a resumption of a conversation about the relationship in the helping context in general, and the alliance in particular, should be resumed.

Resumo

Objetivos: O objetivo deste artigo de revisão é resumir os desafios da pesquisa sobre a aliança hoje e futuramente. A revisão começa com uma breve visão geral do desenvolvimento do conceito da aliança no contexto histórico. Método: Um resumo do que foi realizado tanto na comunidade de pesquisa em psicoterapia quanto em outras profissões é apresentada. Os atuais desafios enfrentados por essa linha de pesquisa são identificados, incluindo a existência de ampla variedade de definições operacionais que resulta em uma difusão da identidade do conceito de aliança. Argumenta-se que a situação atual gera riscos ao crescimento incremental em várias linhas de pesquisa. Conclusões: Argumenta-se que a falta de clareza sobre como várias variáveis dentro da categoria mais ampla de relações terapêuticas se encaixam, se sobrepõem, ou se complementam, também é potencialmente problemática. Esforços para resolver a falta de uma definição consensual são revisados, e em conclusão, argumenta-se que a retomada de uma conversa sobre o relacionamento no contexto de ajuda em geral, e da aliança em particular, deve ser efetuada.

Significância clínica ou metodológica deste artigo: O artigo aborda problemas metodológicos que ameaçam o desenvolvimento de pesquisas sobre a aliança: o termo é operacionalizado de diversas maneiras. O exato significado do conceito está se tornando cada vez mais incerto. Várias linhas de pesquisa abordando o que, na superfície, parecem ser questões semelhantes estão, na prática, lidando com diferentes variáveis. Se a pesquisa sobre a aliança for fazer mais contribuições para a prática, uma definição mais concisa e matizada e métodos de operacionalização mais sofisticados, coesos e coordenados são necessários.

Zusammenfassung

Ziele: Ziel dieses Übersichtsartikels ist es, die Herausforderungen zusammenzufassen, vor denen die Forschung hinsichtlich der Allianz jetzt und in der Zukunft steht. Die Literaturübersicht beginnt mit einem kurzen Überblick über die Entwicklung des Allianzbegriffs im historischen Kontext. Methode: Eine Zusammenfassung dessen, was sowohl innerhalb der Psychotherapieforschungsgemeinschaft als auch in anderen Berufen erreicht wurde, wird vorgestellt. Die gegenwärtigen Herausforderungen, denen sich diese Forschungsrichtung gegenübersieht, werden identifiziert, einschließlich der Existenz eines breiten Spektrums operationaler Definitionen, die zu einer Diffusion der Identität des Allianzkonzepts führen. Es wird argumentiert, dass die derzeitige Situation zu Risiken für das schrittweise Wachstum in mehreren Forschungsbereichen führt. Schlussfolgerungen: Es wird die Hypothese aufgestellt, dass Unklarheit darüber, wie mehrere Variablen innerhalb der breiteren Kategorie therapeutischer Beziehungen zusammenpassen, sich überschneiden oder sich gegenseitig ergänzen, ebenfalls potentiell problematisch ist. Bemühungen, das Fehlen einer einvernehmlichen Definition zu lösen, sind überprüft worden. Abschließend wird argumentiert, dass ein Gespräch über die Beziehung im helfenden Kontext im Allgemeinen und insbesondere über die Allianz wiederaufgenommen werden sollte.

摘要

目的:這篇文獻回顧的目的是摘述同盟研究目前及未來所面臨的挑戰。文獻回顧先簡述同盟概念發展的歷史脈絡。方法:針對在心理治療研究領域及其他專業領域已經完成的部分做摘要整理。同時指出這一系列研究目前面臨的挑戰,包括由於有關同盟概念的操作型定義相當分歧,導致同盟概念莫衷一是。而這樣的情況也會增加更多不同系列研究的風險。結論:若廣義的治療關係底下所蘊含的各種變項定義模糊不清、相互重疊或互補,亦會衍生問題。本篇文章對過去試圖解決缺乏共識的定義問題所做之努力進行了回顧,最後主張研究者間應對一般助人脈絡中的關係,特別是針對同盟,重新開啟對話。

Obiettivi: lo scopo di questa review è quello di riassumere le sfide che deve affrontare la ricerca sull'alleanza attualmente e in futuro. La review inizia con una breve panoramica sullo sviluppo storico del concetto di alleanza. Metodo: viene presentato un riassunto di ciò che è stato realizzato sia all'interno della comunità della ricerca in psicoterapia che in altre professioni. Vengono identificate le sfide attuali di questa linea di ricerca, inclusa l'esistenza di una vasta gamma di definizioni operative che si traduce in una diffusione dell'identità del concetto di alleanza. Si sostiene che la situazione attuale generi rischi per una crescita incrementale in diverse linee di ricerca. Conclusioni: è stato dimostrato quanto sia potenzialmente problematica una mancanza di chiarezza su come diverse variabili all'interno della più ampia categoria di relazioni terapeutiche si adattino, si sovrappongano o si completino a vicenda. Vengono esaminati gli sforzi per risolvere la mancanza di una definizione consensuale e, in conclusione, si sostiene che si dovrebbe riprendere la ripresa di una conversazione sulla relazione nel contesto di aiuto in generale, e in particolare l'alleanza.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: The paper addresses methodological problems threatening the development of research on the alliance: The term is operationalized in diverse ways. The exact meaning of the concept is becoming increasingly unclear. Several lines of research addressing what, on the surface, appears to be similar questions are, in practice, dealing with different variables. If research on the alliance is to make further contributions to practice, a more concise and nuanced definition and more sophisticated, cohesive, and coordinated methods of operationalizations are called for.

It is far more important to know what person the disease has than what disease the person has.

Introduction

Over the last four decades, researchers have been increasingly focusing on the helper–helpee relationship in general and the alliance in particular. The investigation of the relationship between client and helper has become one of the focal topics not only among psychotherapy researchers, but also in the fields of medicine, psychiatry, education, social work, nursing, physical therapy, and forensic sciences (Horvath et al., Citation2014). Yet, despite the growing popularity of the alliance in the research literature, the precise meaning of the term “alliance” is ambiguous (Horvath, Citation2011a). In practice, it can refer to a variety of related concepts and its role in therapy remains somewhat controversial (DeRubeis, Brotman, & Gibbons, Citation2005; Horvath & Bedi, Citation2002; Webb et al., Citation2011). Given the length of time the concept has been in use and the amount of research energy that has been vested in the subject, this apparent lack of consensus may prove to be problematic going forward.

The goal of this review is to examine some of the challenges currently facing research on the alliance and to explore some possible ways these challenges may be met in the near term. The paper begins by situating the last four and a half decades of work on the alliance in a historical context within the framework of the evolving research on psychotherapy. Next, a critical examination of the re-emergence of the alliance concept as a generic variable is presented, followed by a very brief summary of accomplishments initiated by the re-definition of the alliance as a common factor variable. The main sections of this review build an argument that the relaxed, inclusive, definition of the term “alliance” which currently characterizes the field is likely leading to serious challenges and obstacles and can jeopardize incremental development going forward. I conclude with a proposal for a process that could help in meeting the current challenges.

It should be noted that this essay is not meant to be a comprehensive, balanced summary of the status of alliance research. A review aiming to explore possible obstacles must, in the first instance, make the case that such challenges exist. Thus, the focus of this paper will be what I perceive to be challenges and potential ways to resolve these, rather than a fair summary of the long list of achievements and accomplishments alliance researchers have made.Footnote1

One of the main strengths and attractions of the alliance concept is the fact that it is a “common factor,” a generic variable which—at least in theory—has similar utility and meaning across different theoretical orientations (Goldfried & Wolfe, Citation1996). This unique attribute liberates the alliance as it is not constrained within a theoretical framework, but it also adds complexity: There is no identifiable source or doctrine that owns the concept or can speak with authority on its behalf; it is a common factor because it exists by a consensus (Horvath, Citation2011a). Given this unique feature, my aim in this paper is not to offer a solution to what I see as challenges to this line of research, but rather to examine how we got here, to look at some of the past and current attempts to provide more coherence to the concept, and ultimately to open a conversation about the existing state of research on the therapy relationship in general and the alliance in particular.

The Relationship Between Helper and Helpee: A Historical Perspective

The structure of this section follows a loosely chronological sequence. The reason for using a historical framework for my analysis is that, parallel to research on the alliance, over the last 35 years there have been profound changes affecting both how we do research on psychotherapy and the kinds of questions we focus on in our investigations (Krause, Altimir, & Horvath, Citation2011). The dominant role that comprehensive theories of treatment played in structuring our collective research agendas in the past has shifted, and more pragmatic/practical considerations have taken over as the organizing framework. This larger historical context has informed the way the alliance concept has developed, and to some degree, these developments have also impacted the larger research agenda.

The importance of the relationship between the patient and the healer has been recognized since ancient times. The ideal persona or character attributes of the healerFootnote2 and the nature of the connection between the person who provides and the one who receives help vary from culture to culture but, in western societies, the recognition of the importance of respect for the patient and a benign attitude toward his or her symptoms is documented from the writings of Hippocrates onward. Credit for a formal, in depth, exploration of the patient–therapist relationship and systematic consideration of the role of this relationship in therapy belongs to Freud. His thoughts on the nature and focus of the therapist–client relationship were, however, somewhat ambivalent. The centerpiece of his theory, and perhaps his greatest intellectual achievement, was the concept of transference: The power of the unconscious to impose the qualities of past experiences onto future relationships. On one hand, he wrote: “[transference] is a universal phenomenon of the human mind, it decides the success of all medical influence, and in fact dominates the whole of each person's relations to his human environment” (Freud & Strachey, Citation1963, p. 42). But, on the other hand, he also recognized the importance of the conscious aspects of the encounter: The therapist’s kind and compassionate attitude toward the patient, and the patient’s conscious effort to resist the impact of negative transference and to ally and work with the analyst (Freud, Citation1913). However, he never fully integrated these two perspectives on the therapy relationship in his lifetime, and the tension between these two aspects reverberated in the writings of his followers. Ferenczi and Rank (Citation1925), Sterba (Citation1934), Sullivan (Citation1938), Zetzel (Citation1956), and Greenson (Citation1965, Citation1990) all recognized the conscious, positive bond between analyst and client and explored these non-transferential aspects of the relationship and its potential beneficial effects, while others (e.g., Abend, Citation2000; Klein, Citation1952) maintained that all therapist–client relations fundamentally reflect aspects of transference.

Starting in the late 1950s behavior therapists offered a different, more instrumentalist perspective on the therapy process (Wolpe, Citation1958). Classical behaviorists took the position that the power to ameliorate the client’s symptoms resides in the strategies, methods, and exercises prescribed. The therapist’s job is to provide expertise in selecting the appropriate strategy and to deliver such intervention effectively. The helper–client relation itself was thought to be of minimal import. The next generation, the cognitive behaviorists, generally took more of a compromise position: The positive qualities of the relationship provide a context which is beneficial for helping the clients’ purposeful and active engagement with the strategies and homework that ultimately carry the beneficial effects of psychotherapy (Goldfried, Citation1980).

In historical sequence, the next comprehensive perspective on the place of the therapist–client relation in therapy may be broadly characterized as the existential philosophical position (e.g., Buber & Agassi, Citation1999). The specific role of the therapeutic relationship is articulated somewhat differently by theorists of different backgrounds (e.g., Barrett-Lennard, Citation1985; Bugental, Citation2008) but these theories and clinical approaches (sometimes referred to as “humanistic”) share the view that the encounter between therapist’s and client’s genuine selves is therapeutic as such. The “I-thou” type of genuine encounter releases an inner force or capacity toward growth (e.g., self-actualizing tendency, Rogers, Citation1951), or creates an opportunity for the client to access hitherto inaccessible inner resources (Elliott, Bohart, Watson, & Greenberg, Citation2011).

Each of these three broad theoretical perspectives has provided a more or less coherent, albeit somewhat mutually incompatible, framework for the concept of the therapeutic relationship, its major components, and the role and function of the helper–helpee relation in the therapy process. The coexistence of distinct and self-contained theoretical frameworks encouraged the development of two independent sets of measurement resources to match each theory (e.g., measures of transference and countertransference, and instruments to capture Rogers’ concept of Therapist Offered Facilitative Conditions (TOFCs): Empathy, genuineness, congruence, trustworthiness, unconditional positive regard, etc.). And research efforts on the therapy relationship were divided along these theoretical lines. (Researchers in the behaviorist and cognitive behavior therapist camps largely stayed away from empirical work on the relationship prior to 1980.)

The “Common Factors” Perspective

Beginning in the 1930s there were proposals suggesting that some facets of therapy, such as the therapy relationship, were common curative dimensions across all theoretical perspectives (e.g., Frank, Citation1961; Rosenzweig, Citation1936). But these theoretical treatises were not followed by significant empirical research efforts. This situation changed in the late 1970s when a number of research syntheses were published contrasting the effectiveness of therapies based on each of the major theoretical models, and these studies all came to the conclusion that psychotherapy in general provided statistically significant benefits to the clients, but they found no evidence for significant differences in therapy effectiveness across treatments based on diverse theories (Luborsky, Singer, & Luborsky, Citation1975; Smith & Glass, Citation1977).

The conclusions provided by these analyses were interpreted by researchers along two contrasting lines of logic: On one side, it was taken as evidence that some common elements in therapy, shared by treatments based on different theories, are responsible for the lion’s share of therapy effectiveness; this conclusion was subsequently often referred to as the “Dodo Bird Verdict.” On the other side, it was argued that the results of these research syntheses were ambivalent; this critique of the “Dodo Bird Verdict” was based on the claim that the methods implemented in the meta-analyses were unable to detect the superiority of some targeted treatments developed for the amelioration of specific psychological problems (Chambless, Citation2002). From this perspective, it was suggested that psychotherapy research ought to follow the example of medicine and seek to find evidence for specific treatments that are efficacious in treating specific symptoms (Chambless & Holon, Citation1998).

These contrasting interpretations of the meta-analytic results had a complex and significant long-term impact on psychotherapy research for the following decades (Wampold, Citation2001). The full assessment of these is beyond the aim and scope of this review. It will suffice to identify two issues that directly affected the evolution of research on the therapy relationship. First, both interpretations de-emphasized the role of the comprehensive theories of psychotherapy, one in favor of factors common to diverse theoretical orientations, the other in favor of evidentially efficacious specific intervention sequences, irrespective of their theoretical bases. Second, the debate between these two interpretations tended to promote the notion that therapy effects can be conceptually divided into specific versus generic (common factor) ingredients (Ahn & Wampold, Citation2001; Butler & Strupp, Citation1986).

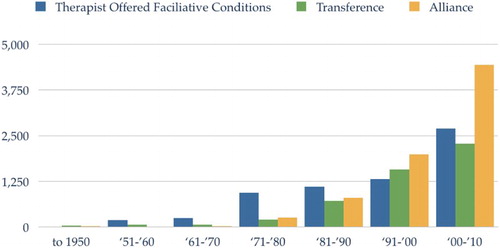

As noted above, one of the major consequences of finding no significant differences in terms of efficacy among therapies based on different theories was that it provided a strong impetus for finding the effective “ingredients” common to different kinds of treatments: The “common factors.” Naturally, the helper–client relationship was identified as an obvious candidate, and the number of research publications focusing on some aspect of the therapy relationship increased dramatically. In the 50 years between 1910 and 1960, approximately 1020 items were published on the topic; over the next decade alone this number doubled, and in the next 50 years (1960–2010) over 31,600 research publications were listed in the PsyInfo database (Horvath, Citation2010). Even taking into account the overall increase in research output over this period, the shift in research focus is evident.Footnote3

The increased interest in the relationship as a generic or common factor variable can be illustrated by examining the topics of interest within the broad category of therapy relationship. In , the growth of three of the major research topics related to the therapy/helping relationship: Transference, Rogerian facilitative conditions, and alliance, is illustrated. Of these three, transference is arguably the most theory-specific topic; the TOFCs are based in Rogers work, but the concepts—especially empathy—have currency across diverse therapy modalities, while the modern alliance concept is most closely aligned with the notion of a common or generic factor present in all forms of psychotherapy. Interest in each of these topics has shown significant growth but, from the time the Dodo Bird “spoke,” the variables most closely aligned with the common factors concept appear to be receiving accelerating attention (Horvath, Citation2010).

Research on the Alliance Beyond Psychotherapy

The events summarized above are specific to the field of psychotherapy. But the growth of research interest in the relationship as a generic or common factor is also part of a larger shift in research focus involving other helping professions. Horvath et al. (Citation2014) surveyed the literature in six related helping professions: Medicine, nursing, social work, physical therapy, education, and neurology/rehabilitation. Within these domains, they located 3141 research publications with relationship foci, most published within the last 20 years. Their survey located 900 independent reports with data on the helper–helpee relationship and 79 studies provided data with sufficient detail that numerical synthesis and comparison with similar analyses in the psychotherapy research was feasible. The pattern across these “sister” helping professions closely paralleled those found in psychotherapy research journals: A dramatic increase in helper–helpee relationship research starting in the 1980s; and a gradual move away from specific theory and profession-based relationship variables toward common factor conceptualizations, specifically the alliance. As in psychotherapy, the lion’s share of the research published investigated the links between generic/common factor relationship variables and treatment outcomes specific to each profession. Similar to psychotherapy research, the effect size (ES) range was 95% CI: r = 0.19 − 0.32 (k = 79) and the distribution of effect sizes was highly heterogeneous (Q = 3206.87, I2 = 97.57%), values very similar to the ones reported for psychotherapy (Norcross & Lambert, Citation2014).

Taken together, these findings reinforce the impression that the arrival of the Dodo Bird Verdict had a broad and significant impact on the amount of energy that researchers invested in aspects of the relationship between helper and helpee, with similar results across a number of service-oriented professions.

The History of the “Modern” Concept of the Alliance

In order to better understand what kinds of knowledge this vast amount of research has yielded, we need to take a step back and take a closer look at the origin and re-birth of the alliance concept as a common factor. As noted above, the role of the conscious, reality-based component of the relationship in therapy has a long history in the psychoanalytic literature. Sterba (Citation1934) provided a comprehensive model of a non-transferential aspect of the client–analyst relationship, and Zetzel first applied the label “alliance” to this bond between analyst and client in 1956. The idea of a reality-based collaboration between the patient and therapist was further developed by Greenson in 1965. He provided extensive descriptions of the role of the working alliance (referring to aspects of personal attachments) and therapeutic alliance (the “us working together to defeat the problem”) in psychodynamic psychotherapy. However, the concept generated little attention from empirical researchers until the 1980s. I have argued before that the Dodo Bird Verdict in the late 1970s dramatically changed the larger context of psychotherapy research: The pre-eminence of one of the available theoretical frameworks was not going to be resolved by evidence of superior efficacy. The need for a unifying, overarching framework to account for what makes therapy work became increasingly compelling. Psychotherapy, as a scientific enterprise, was under pressure to resolve the anomaly of having multiple, equally efficacious but incompatible, theories both as explanations for, and as the fount of resources for treatment of mental illness (Wampold, Citation2001).

This was the Zeitgeist in 1976 when two eminent psychodynamically trained researchers, Lester Luborsky and Edward Bordin, independently suggested that a re-formulation of the psychoanalytic relational concept of the alliance could be the centerpiece for a model that could account for an important generic element in psychotherapy process. Over time, in lieu of a consensual explicit definition of what the alliance is, Luborsky’s and Bordin’s ideas on the alliance became those most often cited by researchers, in practice the “canonical descriptors” of the alliance. It is, therefore, useful to briefly review what these authors actually said and wrote, and how some of these ideas were realized in subsequent research projects.

Luborsky’s Concept

Lester Luborsky first presented his concept of the helping alliance (HA) in the context of his findings in the Penn Psychotherapy Research Project (Luborsky et al., Citation1980). In this presentation, he noted the failure of client variables or types of therapies to explain significant portions of variance in therapy outcomes (Luborsky, Citation1976). He then proposed a model of effective ingredients in psychoanalytically oriented therapies. In his analysis, he drew a distinction between “techniques” (that category includes the structure of therapy and interventions) and “relationships.” This latter category was further broken down into transference types and HAs (p. 93). He did not offer a definition of the HAs per se, but he referred to Zetzel’s (Citation1956) and Bordin’s ideas on the subject. It is important to note that, for Luborsky, “HAs” and transference comprised all the relevant components of the “Helping Relationships.” In the 1976 paper, he refrains from extrapolating the relevance of the model of relationship presented, or the concept of the HA, beyond psychoanalytic therapies. But he adds an important distinction to the prior notions on the alliance: The HA develops in two stages: Type1 consists of the therapist providing support and encouragement to the client, and Type2 involves the therapist and client working collaboratively together. He suggests that these two types of HA develop sequentially, Type1 corresponding to the early/opening phase of treatment and is superseded by Type2 in the later phases of treatment (Luborsky, Citation1976).

The conceptual framework presented in the first part of the 1976 chapter was followed by an example of research using these alliance concepts and the Core Conflictual Relationship measures to predict therapy outcome. In this portion of the paper, he presents various options and tools to assess and measure the quality of the HAs. Luborsky directly addressed his version of the HAs in detail on only one more occasion. In 1987, a more complete and formal version of the Penn Helping Alliance Scales (six different methods, complete with validity data and clinical examples) was provided (Alexander & Luborsky, Citation1987). In this later publication, the HAs are placed in a broader context (i.e., not exclusively within analytical psychotherapy) but the description of the HA is in the same functional terms as in the 1976 paper. As well, the emphasis in the 1986 chapter is on the practical measurement of the alliance rather than on the discussion of its theoretical dimensions. Some of these original measures were subsequently revised as HAqII (Luborsky et al., Citation1996) but neither versions of the HAq could confirm the proposed two sequential stages of development of the alliance proposed by Luborsky (Davis, Citation2011).

Bordin’s Conceptualization

In the research literature, the most often cited reference to what constitutes the alliance is based on the work of Edward Bordin (Citation1979, Citation1994). Bordin explicitly positioned the concept of the working alliance as a pan-theoretical variable “[that] have origin in psychoanalytic theory, but can be stated in forms generalizable to all psychotherapies” (Citation1979, p. 253). His root sources for the construct appear to be Sterba (Citation1934), Zetzel (Citation1956), Menninger (Citation1958), and most directly Greenson (Citation1965). He describes the working alliance as arising from achieving consensus and producing collaboration between therapist and client in three areas: The “Goals” of therapy, the means by which these goals will be achieved (“Tasks”), and personal attachments which he labeled “Bonds.” It is important to note that Bordin’s “definition” of the alliance, like Luborsky’s, is narrative as opposed to persuasive. A narrative definition focuses our attention on how something comes about, how it functions, what it does. In contrast, a persuasive definition addresses the limitations and boundaries as well as the substance of the construct.Footnote4

Both of these important historical sources, but especially Bordin, described the alliance in lexical, common use, language and the focus of his writings on the subject are on the issue of what the alliance and each of its components do in therapy. This kind of definition leaves the boundaries (i.e., limits, what it is not) quite open and flexible, subject to a range of interpretations. Moreover, neither of these “canonical sources” situated the alliance in a broader relational context. That is, they did not address the problem of the relation of the alliance vis-à-vis kin relationship concepts that were, and are, in concurrent use in clinical practice and research (e.g., empathy, genuineness, positive regard, warmth, attunement, flexibility, attachment style, etc.). The only clear distinction that these root sources documented was between the alliance and transference. In retrospect, it has been argued that Bordin’s writings on the topic inferred that the alliance functions at a different conceptual level than relationship concepts such as empathy, genuineness, or attachment style. This interpretation suggests that the alliance is the result of a joint endeavor (collaboration) between therapist and client rather than something the therapist does or achieves as such (Hatcher & Barends, Citation2006). However, there appears to be very limited use in research of this distinction (Horvath & Hatcher, Citation2009). In practice, Bordin’s descriptive definitions are most often treated as flexible and open to a variety of interpretations (Samstag, Citation2006b).

Unlike Luborsky, Bordin did not directly address the problem of assessing the working alliance, but focused on explicating his theory of the role of alliance in the therapy process. He proposed, in essence, that the development of the alliance and its management (repairing and rebuilding) through the inevitable stresses and possible ruptures in the course of therapy constitute core processes in all forms of treatments:

… [this] collaborative process represents an arena in which the patient once more encounters his self-defeating propensities … To the extent that the patient achieves a different … mode of response at the level that fosters generalization … this change will extend to other life situations and to relationships … . (Bordin, Citation1994, p. 18)

The Impact of These “Canonical” Formulations of the Alliance on Research

Bordin’s approach to the concept not only liberated the alliance from its links to various forms of transference, but also blurred the distinction between the relationship and strategies/interventions: Agreements on tasks and goals, and especially the bond component, are described as relational achievements, but the building and maintaining of these components of the alliance (repairing the stresses and strains) are construed as core interventions. Around this time the practice in research of treating the relationship and interventions as relatively independent elements was increasingly identified as problematic (e.g., Butler & Strupp, Citation1986), and Bordin’s positioning of the alliance as capturing “both sides of this coin” was likely a response to this problem.

Bordin’s legacy, the way he structured his narratives on the alliance, had several important consequences. On one hand, the alliance became an easily accessible and useful variable for researchers investigating the role of the relationship in diverse kinds of therapies, whether these treatments were embedded in specific theories or eclectic. On the other hand, his process-oriented, descriptive, definition did not provide clear distinctions between the alliance and other elements or processes that likely play a role within the broader framework of the therapy relationship. As well, the narrow focus on Tasks, Goals, and Bonds as targets of realizing the alliance prioritized issues that are most often associated with the early phases of the helping (developing interpersonal bonds, establishing goals, and selecting appropriate therapeutic procedures) and most often receive lesser emphasis—being already well established—later in the helping process.

Bordin’s and Luborsky’s papers were the “launching pads,” the sources of the ideas that stimulated researchers to explore the concept. But, as researchers with diverse orientations assimilated these ideas through the filters and lenses of their specific theories and adopted the notion of the alliance to the particulars of the client population they were working with, the concept of “the alliance” acquired a kind of multiple personality and identity in “common factor land” (Horvath, Citation2011a).

Operational Definitions

The vast majority of empirical studies of the alliance reference Bordin’s writings as a way of identifying or locating the concept (Horvath & Bedi, Citation2002). However, in practice, researchers select a particular method of alliance assessment (i.e., a test or inventory or a rating procedure) and a source of information (self-report or observation) and these, in combination, operationally define what this investigator will thereafter call “alliance.”

Luborsky and colleagues developed a number of measures to tap into his concept of the HA (HAq: Alexander & Luborsky, Citation1987; Luborsky et al., Citation1996). As a consequence, the HAq scales can be considered an authoritative operationalization of his concept. A number of studies continue to use versions of the HA scales, but the concepts measured in these studies are almost always generically referred to as “alliance” and the underlying distinction between Bordin’s and Luborsky’s conceptualizations of the alliance is almost never mentioned in these publications.

Bordin did not take a position nor provide directions on the technicalities of assessing the alliance. The task to develop a measure to actualize Bordin’s definition was passed on to researchers from different orientations. However, as discussed above, the narrative descriptors provided by Bordin spoke to the functions of the concept but omitted discussion of its boundaries or the specifics of how it related to other variables that evidentially play important roles in therapy in general and the therapy relationship in particular (Norcross, Citation2002; Norcross & Lambert, Citation2011). These gaps in an authoritative functional definition left a kind of conceptual vacuum that was, to a large extent, filled instrumentally by the alliance measures.

The Alliance Measures

Conceptual Challenges

Researchers wishing to develop measures to assess the alliance are faced with three kinds of conceptual challenges: The first is the lack of an authoritative consensually endorsed prescriptive definition—as noted. Second, the concept of the alliance had an important history before Bordin’s and Luborsky’s work, and this prior literature left some alternative definitions and descriptors still in use, particularly within the psychodynamic theoretical framework. Third, the word “alliance” has a well-established, lexical meaning: i.e., “the act of allying or state of being allied; a formal agreement or treaty between two or more entities; to cooperate for specific purposes; a merging of efforts or interests” (OED). Such a “commonsense” meaning has both a conscious and a subconscious impact on our understanding of what an alliance means, and this lexical meaning needs to be accounted for—even in a professional context.

In addition to these conceptual issues, a measure of the alliance has to be positioned on the time dimension: Alliance has been measured as a moment-to-moment phenomenon, as a quality surmised at the end of the session, between sessions, and over the phases and even the whole course of treatment (Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2016; Reynolds, Stiles, & Grohol, Citation2006; Safran & Kraus, Citation2014; Safran & Muran, Citation2000; Stiles et al., Citation2002).

Almost a decade ago, Elvins and Green (Citation2008) identified more than 60 alliance measuring instruments. Subsequently, in 2011 three meta-analyses were published summarizing the relations between therapy outcome and alliance in individual therapy, family therapy, and child and adolescent therapy (Norcross, Citation2011). In the combined instruments lists included in these three chapters, there were over a dozen alliance measures not on Elvins’ and Green’s list. In the most recent meta-analysis of the relation between the alliance and therapy outcome (Flückiger, Del Re, Wampold, & Horvath, Citation2017), 42 “family of measures” were identified, 8 of which were not present in the similar analysis in 2011. Thus a conservative estimate suggests that currently well over 70 different instruments de facto operationally define the alliance concept in research, and the development of new instrument continues.

There is an impressive range of diversity among these instruments: A subset of these measures are modifications of older tests to better suit specific populations (e.g., in-patients, younger populations, and specific contexts and so on). Some of the instruments in current use are based on some specific clearly explicated variant of the alliance concept (e.g., Doran, Safran, & Muran, Citation2016). Many of them claim to instantiate Bordin’s concept but omit some aspects of the original structure of Bonds, Task, and Goals (e.g., measures based on therapeutic bonds; Saunders, Howard, & Orlinsky, Citation1989) and/or add concepts not included in the Bordin/Luborsky descriptions of the alliance (e.g., working capacity, safety, etc.). Researchers are also, increasingly, using measures developed to assess other relational constructs (e.g., the Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory, Barrett-Lennard, Citation1978) and calling the variable measured alliance.

Technical Challenges in Measuring the Alliance

A few of these alliance assessment procedures are “one off,” made for the specific investigation without evidence of validity or psychometric properties (Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, Citation2011). But most measures provide evidence of construct validity based on one of two criteria (or both): (i) statistically significant correlation with another alliance measure and/or (ii) evidence of correlation with therapy outcome. However, both of these criteria are problematic.

First, correlation with outcome as a proof of construct validity is based on questionable logic. There could be many diverse variables, relational or otherwise, that correlate to outcomes, but two variables that each share significant variance with a third (i.e., outcome) do not necessarily share a significant amount of variance with each other. Thus, such links say nothing about the conceptual similarity, much less identity, of the underlying construct sampled. And second, statistical significance between two measures indicates only that the relationship between them is greater than would be expected by chance alone at a chosen level of probability. But statistical significance does not guarantee that these measures “mostly” or “by and large” measure the same concept. A more sensible way of estimating overlap between instruments is by examining the amount variance they share in common.

In order to get a realistic estimate of the true relation between instruments, we should ideally examine parallel applications, i.e., two measures used on the same subjects at the same time. Research protocols reporting the use of two or more different measures are rare, but in one small-scale study comparing the four most frequently used instruments (California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale: Gaston & Marmar, Citation1994; Vanderbilt Therapeutic Alliance Scale: Hartley & Strupp, Citation1983; HAq: Alexander & Luborsky, Citation1987; Luborsky et al., Citation1996; Working Alliance Inventory: Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1986), it was estimated that these well-established and popular alliance assessment instruments share less than 50% of common variance using the same “source of report” (i.e., client or therapist self-reports, Horvath, Citation2011b). As well, it appears that assessments based on the same measure, but utilizing different sources of information (i.e., a combination of self-report and observation-based assessments) also, on the average, share less than half of common variance (Fenton, Cecero, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, Citation2001).

Given the multiple sources of diversity of the instruments discussed above, the findings of less than 50% overlap among measures are not surprising. In fact, the extent of overlap among newer instruments is likely significantly less, since many of the four older instruments were cross validated among each other, but as the number of instruments to which newer measures may be anchored grows, the likelihood of drift among the measures increases.Footnote5

And finally, the very existence of so many measures can be considered as evidence of diversity: If each of the measures captured the same or very similar concept, there would be no incentive or need for such multiplicity and continued production of instruments.

Consequences

The use of a large number of and diverse alliance measures in research has impacted alliance research in complex ways. The observed differences between client- and therapist-based self-reports of the quality of the alliance using similar or identical instruments likely reflect genuine difference in perspectives on, and different contributions to, the relationship (Del Re, Flückiger, Horvath, Symonds, & Wampold, Citation2012; Tryon, Blackwell, & Hammel, Citation2007). However, the diversity between observer and self-report-based alliance measures suggests that the phenomenological information the participants respond to and the observable data address different aspects of the relationship (Horvath & Bedi, Citation2002).

Importantly, although each of these instruments most likely captures some aspect of the “clients enthusiastic participation”—a concept identified as the practical common denominator across measures (Hatcher, Barends, Hansell, & Gutfreund, Citation1995), the apparent modest overlap among the measures indicates that there are likely non-trivial differences among the underlying variables operationalized. A quantitative estimate of the extent of the difficulties such diversity presents is provided by examining the measures of heterogeneity in recent large-scale studies. Two meta-analyses examined the effect sizes between the alliance and outcome in different populations; each found the diversity of the primary studies underlying the analysis about 50% greater than if the spread in the outcomes were due to just “normal” random variability (Friedlander, Escudero, Heatherington, & Diamond, Citation2011; Horvath et al., Citation2011). Variance in such investigations may be due to a variety of factors, but in these instances attempts were made to account for the excess variance by looking for plausible sources for such diversity, and none was found significant (Flückiger et al., Citation2013). In other words, the diverse ways the concept of the alliance is operationalized through these many measures has created a significant semiotic problem: The signifier “alliance,” as used in the literature, can point to a number of rather loosely related “objects.” Such a lack of consensus both reduces the generalizability of the research findings and undermines the incremental development of lines of research.

A more qualitative perspective on the consequences of diverse ways of operationally defining the concept is illustrated by its impact on a very important subject in alliance research: Alliance ruptures. The management of the inevitable strains on the alliance through the course of treatment was emphasized by Bordin throughout his writings (Citation1994). There is a significant body of research literature on this subject. However, within this corpus, “alliance rupture” could reference relational strains occurring between sessions (Stiles et al., Citation2002), within a whole session (Benjamin & Critchfield, Citation2010), between parts of the session as defined by thought units (Doran et al., Citation2016), or between parts of the session as defined by grammatical units (Ribeiro, Ribeiro, Gonçalves, Horvath, & Stiles, Citation2013), or even within utterances (Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2016). Each of these time frames represents a legitimate and meaningful conceptualization of disruption in the alliance between therapist and client, but clearly at very different (and not necessarily additive) levels. Repairing and rebuilding alliances is an important clinical issue. The utility and impact of research findings on ruptures would be likely far greater on clinical practice if we could reach consensus on what the term “alliance rupture” refers to.

A discussion of the impact of the large number and diversity of alliance measuring procedures would be incomplete without examining the overarching question: What does the presence and continuing development of such a large number of instruments tell us about the concept itself? The premise of this question is that the accumulation of such an abundance of measures is not a normal development of research praxis, but something unusual and meaningful. Some duplication of assessment procedures to measure a psychological concept, or process, is in itself not unusual. Moreover, some variants of instruments are needed to meet the requirements of specific populations (e.g., couples and families: Friedlander et al., Citation2006; Knobloch-Fedders, Pinsof, & Mann, Citation2007), diagnostic subsets (e.g., personality disorders: Lingiardi, Filippucci, & Baiocco, Citation2005), or design issues such as abbreviated, short version (e.g., Working Alliance Inventory-Short Revised: Falkenström, Hatcher, & Holmqvist, Citation2015). But after all these needs are taken into account, reviews indicate that there is an extraordinary number of duplication of “generic” alliance measures (Elvins & Green, Citation2008). It should also be noted that the newly developed instruments do not appear to improve,Footnote6 replace, or supersede existing assessment methods (Horvath, Citation2011b). The continuing growth in alliance measures is evidently an additive process. Developing instruments is a labor intensive, yet alliance researchers still continue to invest energy and time in constructing new measures to capture the essence of the alliance.

Based on the preceding review, there seem to be at least two complementary reasons for the continued need for additional instruments. One possible explanation is that this activity is the by-product or corollary of the growing awareness of the importance of the helping relationship in therapy. There is an apparent consensus, not only among psychotherapy researchers, but also in medicine, education, nursing, social work, rehabilitation, and physical therapy, that the relationship between the helper and the one receiving help is important and should be included as an integral part of studies aiming to account for the efficacy of all forms of treatments (Horvath et al., Citation2014). The alliance, in this context, is a “stand-in” or “avatar” for some aspects—or even the whole—of the broader concept of the helper–helpee relationship (Horvath, Symonds, Flückiger, Del Re, & Lee, Citation2016). Since the position or nexus of the modern concept of the alliance vis-à-vis other elements or processes in the helping relationship has never been consensually settled (Samstag, Citation2006a), each investigator is at liberty, indeed maybe compelled, to include relationship variables beyond the traditional Tasks, Goals, and Bond elements, or omit some of these vectors in order to reflect a holistic conceptualization of the relationship. If this hypothesis is correct, it would imply that the proliferation of instruments is, in fact, a search for a better more clear representation of the helping relationship, and the use of “alliance” in the test title is a kind of short hand for a composite core element of the helping relationship.

Another possibility is that the multiplication of instruments is a natural response to the minimalist description of the alliance provided by Luborsky and Bordin. This perspective would suggest that researchers in the field in general, and authors of alliance measure in particular, have an intuitive grasp of the concept of the alliance that takes into account (or perhaps were inspired by) Bordin’s idea but, in each instance, go beyond and try to fill the gaps and augment the “canonical description” of the concept. However, instead of explicating these extensions or modifications in text, these intuitions find expressions in yet another alliance measure.

Regardless of which of these explanations comes closest to reflecting the motivation behind creation of new measures, these instruments, as operational manifestations of the concept of “alliance,” collectively obscure rather than clarify the essence of the concept.

Accomplishments

Although the focus of this paper is to identify the challenges confronting alliance research at this stage, the account would be incomplete and lopsided without situating it in the context of what has been achieved. The research literature on the alliance has, however, grown so large and complex that even a simple catalogue of important contributions would require far more space than this paper could accommodate. What follows, therefore, is a highly abbreviated and selective list of some of the lines of investigations that suggest the character of the work.

Perhaps the most visible aspect of the research on the alliance has dealt with its relation to therapy outcomes. A moderate (ES ≈ 0.26) but very robust positive link has been well documented (Horvath et al., Citation2011; Horvath & Symonds, Citation1991; Flückiger et al., Citation2017; Martin, Garske, & Davis, Citation2000). Over the last two decades, the investigation of this link has become more nuanced, identifying sources of contributions to the alliance (Baldwin, Wampold, & Imel, Citation2007; Del Re et al., Citation2012; Kivlighan, Kline, Gelso, & Hill, Citation2017), investigating these links in specific populations, and identifying some differences across racial and diagnostic lines (Flückiger et al., Citation2013).

Several different programmatic investigations of repairing stresses (ruptures) in the alliance have yielded important knowledge about these events and a number of treatments and training programs have been developed that take advantage of an “alliance-centered” approach (Eubanks-Carter, Muran, & Safran, Citation2015; Safran, Muran, & Shaker, Citation2014).

Work on the alliance has made contributions to important research and clinical developments using systematic feedback to prevent deterioration, and premature termination and to improve outcomes (Lambert, Citation2010; Lambert & Barley, Citation2002). Research has provided a better understanding of how therapists can contribute to both difficulties in and improvements to the alliance, and several training programs have been developed and evaluated based on these ideas (e.g., Crits-Cristoph, Crits-Cristoph, & Connoly Gibbons, Citation2010; Eubanks-Carter et al., Citation2015; Henry & Strupp, Citation1994). There are a number of research programs investigating the links between specific critical events in therapy (e.g., interpretation, insight, “innovative moments,” self-criticism, confrontation, etc.) and the alliance at the moment-to-moment level (Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2016; Peräkylä, Citation2004; Rosa, Gonçalves, Sousa, & Horvath, Citation2017). There are also investigations probing the alliance as an interpersonal process using Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) and other process instruments (Henry & Strupp, Citation1994; Safran & Kraus, Citation2014).

Norcross and Lambert (Citation2014) summed up the overall impact of the large body of work since the 1970s noting that this corpus of research has been instrumental in bringing to the forefront the clinical significance and importance not only of the alliance, but also of the relational side of the psychotherapy process in general.

Current Challenges

From a broad, historical, perspective the “semiotic problem” may be framed as a product of the search for common factors. In this context, it is a kind of generality versus specificity dilemma: A concept identifying a feature common to all forms of treatments, by definition, has to be adaptable and broadly inclusive. It needs not only to accommodate/adapt to different theoretical models and types of therapy, but also to make room for individual differences among clients and therapists. The cost of expanding a concept’s horizons is the risk that, as the idea’s boundaries soften and as the concept becomes more and more “adaptable,” what it represents becomes progressively vaguer, eventually losing its meaning and clinical utility. In the case of the alliance, this drift is propelling the concept toward the point that its meaning is, in some applications, difficult to distinguish from the broad concept of the therapy relationship (Horvath et al., Citation2016). But the merging of these concepts would risk a great loss and step backwards: Our goal is to better understand how the relationship works in therapy. To accomplish this, we must identify its different features, make distinctions to better understand differences between therapist–client relationships, discover how particular aspects of the relation promote healing in specific circumstances. Science progresses by making distinctions; homogenizing differences does not serve the enterprise.

The impetus in the other direction, toward restricting the concept, is driven by an equally compelling general argument: To best serve the client’s needs, each therapy must be unique, responsive to the demands of the particular problems the client has, as well as to the range of specific client, therapist, and contextual variables (Stiles, Honos-Webb, & Surko, Citation1998; Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017). This line of reasoning would call not only for narrowing the scope of the definition, but also for identifying subtypes of alliances corresponding to contexts and circumstances. Bordin appears to have been sensitive to this dilemma. In introducing the concept of the working alliance, he immediately noted that different forms of therapy will demand different kinds of alliances, goals, and tasks specific to the kind of therapy. Moreover, he noted that the quality of the alliance is predicated on a “fit” with the personal characteristics of the therapist and client (Bordin, Citation1979, p. 253). But the idea of therapy-specific alliances, or the concept of the fit between client and therapist did not gain a lot of traction in research, although there is some empirical evidence that clients’ relational needs indeed differ (Bachelor, Citation1988, Citation1995; Bedi & Duff, Citation2009).

If we accept the argument that the broad variety of operational definitions (as represented by the 70 odd instruments currently in use) is a reflection of a consensual position of the research community, then it seems evident that the community has preferred to go along with an assumption of homogeneity across treatment and client variables. The status quo in this respect is a kind of reversal of the biblical conundrum at the Tower of Babel: The same word (alliance) represents a number of different things to different people.

Clarifying the Identity of the Alliance

Theory-Based Solutions

I argued earlier that the identity of the alliance concept is at risk due to the large number of measures and sources of information that operationalize the concept. I have also tried to make the case that this state of affairs is an accurate reflection of the current status of the concept. While I maintain that this is a reasonable concern with respect to the literature as a whole, it should be noted that there have been several sustained attempts to go beyond Bordin’s descriptive definitions and to provide a more circumscribed identity to the alliance. Several of these formulations embed the alliance in a broader theoretical frame and provide a structure indicating the relations of this concept to other elements in the therapy relationship.

Beginning in Citation1985, Gelso and Carter have developed a theoretical framework for the therapy relationship based on the idea that it may be best understood as having three components: Transference, alliance, and the real relationship (RR). This position is rooted in, and extends Greenson’s (Citation1967) work, and departs from Bordin’s (Citation1979, Citation1994) view that the “RR” is captured by the bond aspect of the alliance. Gelso (Citation2014, p. 119) proposes that “ … the extent to which each [the therapist and client] are genuine with the other and perceives/experiences the other in ways that befit the other” is “the most fundamental” aspect of the therapy relationship. In this framework, the alliance is a product of therapy, in contrast to the RR which is a natural component of all relationships. The framework postulates that the alliance may be infused with aspects of transference, and is a function of the alignment of the client’s reasonable ego and the “therapist’s analyzing or therapizing side” (Citation2014, p. 120). Gelso and colleagues have continually developed and refined this theory, recently constructing and validating an instrument to measure the RR (Real Relationship Inventory (Client version): Kelley, Gelso, Fuertes, Marmarosh, & Lanier, Citation2010). With the availability of the RRI, there are now empirical studies addressing the links among RR, the alliance, and therapy outcome (e.g., Kivlighan et al., Citation2017).

Safran, Muran, and colleagues have been studying disruptions or ruptures in the alliance since 1990 (Safran, Crocker, McMain, & Murray, Citation1990). Based on their empirical work, and influenced by the relational psychodynamic perspective of Aron (Citation1996) and Mitchell (Citation1997), their theory is a further development of Bordin’s idea that the management of alliance fluctuations is the core of the therapeutic process. They have re-focused the defining feature of the alliance from the quality of consensus and agreements to the process of negotiation: “ … an ongoing cycle of enactment and collaborative exploration of the therapist’s as well as the patient’s contributions to the interaction” (Safran & Kraus, Citation2014, p. 381). This group has also developed a measure: The Alliance Negotiation Scale (Doran et al., Citation2016) and is generating research on the alliance-as-negotiation concept.

The oldest of the theory-embedded models of the alliance is Luborsky’s (Citation1976). His conceptualization of the two-phase sequentially developed alliance is an extension of the classical psychodynamic framework described by Zetzel (Citation1956). He and his coworkers have done a great deal of innovative work on alliance assessment, but currently only the revised HAq scales are used in research. Unfortunately, the variables measured using this instrument are often not differentiated from or are conflated with Bordin’s conceptualization of the alliance (Alexander & Luborsky, Citation1987; Le Bloc’h, de Roten, Drapeau, & Despland, Citation2006; Luborsky et al., Citation1996).

Each of the above projects represents a sustained and cohesive re-thinking of where the alliance best fits into the broader concept of therapy relationship. In each case, the authors developed their own assessment tools, making it more likely that these conceptualizations will remain less vulnerable to “semiotic drift” in research use. All these projects are based on and extend earlier psychodynamic models of the relationship. This makes a lot of sense; psychodynamic therapy, at its core, is relationship based; the relationship is an “active therapy ingredient.” The originators of these frameworks present their conceptualization as applicable beyond psychodynamic therapy, but each depends on premises that include the function and dynamics of unconscious processes (i.e., transference and countertransference) as they are broadly understood within the psychodynamic framework. This aspect of these models, in practice, likely limits the use of the alliance so defined as a common factor.

“Bottom-Up” Approaches

There are a number of emerging lines of research that approach the challenge of constraining the definition of the alliance by using a more “bottom-up” approach. For instance, Ribeiro and colleagues have been studying the alliance at the moment-to-moment level. In their research, they operationalize the alliance as the act of collaboration: “[the] shared responsibility for deciding treatment goals … planning activities … and participation in therapy tasks … [and] affinitive cooperative behaviors” (Ribeiro et al., Citation2014, p. 295). Their method starts by selecting critical segments of clinical material using the concept of Therapeutic Zone of Proximal Development (Leiman & Stiles, Citation2001)—an extrapolation of Vygotsky and Kozulin’s (Citation2011) educational concept of zone of proximal development. Next, fine-grained turn-by-turn analysis is applied to these segments to trace the role of collaboration/alliance as these events unfold to yield positive or negative outcomes (Ribeiro, Gonçalves, Silva, Brás, & Sousa, Citation2015; Ribeiro et al., Citation2013, Citation2014).

Another group using a “bottom-up” approach utilizes concepts and tools borrowed from Conversation Analysis (CA). CA is an ethnomethodological approach for the analysis of social interaction. It can be applied to explicate the relational process in therapy. Kozart (Citation2002) proposed that “ … the therapeutic alliance consists of an array of conversational devices that maintain the natural flow of conversation and interaction … that address the problems and concerns that bring patients into therapy” (p.229). The CA perspective is interactional; behavior is explored from the perspective of individuals using talk as a means of dynamically negotiating consensual meanings and to effect change in one another. CA researchers use transcriptions of excerpts of clinical conversations rich in detail, including prosodic elements such as intonations, pauses, and non-verbal behaviors as data.

In this framework, therapy discourse is not only the unfolding of prior intents, motives, and dispositions of the participants, but is an interactive social behavior that dynamically realizes the achievements of treatment (Heritage, Citation2011; Peräkylä, Antaki, Vehviläinen, & Leudar, Citation2008). CA research methods have been applied to several aspects of the therapy process, including the management of the therapy relationship and the alliance specifically (Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2014, Citation2016; Peräkylä, Citation2008). CA research using the alliance-as-process perspective yields a variable that is specific to a particular context (e.g., alliance repair, confrontation, questioning, etc.) but generic across kinds of treatments (Antaki, Citation2008; MacMartin, Citation2008)

There are a number of emerging “bottom-up” research approaches to capture and describe the alliance functionally. These include the use of therapists’ responsiveness as a “marker” for the presence of alliance (Elkin et al., Citation2014; Stiles et al., Citation1998; Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017). A micro-process analytic method based on the generic change model of stuck and unstuck episodes as theoretical lenses (Krause et al., Citation2007). A similar qualitative method was used by Ribeiro et al. (Citation2014) utilizing the innovative moment (Gonçalves, Matos, & Santos, Citation2009) theoretical framework to identify and analyze the alliance in clinical process. The SASB (Benjamin, Citation1974) has also been used to operationalize the alliance as a within-person process (Benjamin & Critchfield, Citation2010; Safran et al., Citation2014).

What Do These Approaches Have to Offer

Each of the above approaches addresses some aspects of what was identified as “semiotic drift”—the inconsistency in what the concept “alliance” refers to in research. Each of the three theory-based approaches has the means to operationalize the alliance in a manner consistent with a well-developed theoretical framework. Also, importantly, the referent frameworks provide some guidance and help to situate the alliance in the larger framework of the therapy relationship and provide a structure to explore the relation of the alliance to other important relational variables.

The limitations of these theory-embedded approaches include the fact that these frameworks maintain references to dynamic unconscious processes—a notion that Bordin was trying to distance the concept from in order to make the alliance concept relevant to all forms of therapy. As well, each operationalizes a different kind, or perhaps a different portion, of the alliance. In addition, it seems yet unclear whether the three systems that bear some theoretical kinship are compatible and complementary or irreconcilable.

The process-oriented solutions offer different advantages: There is a time-consistency across these methods. Each looks at brief clinical exemplars of episodes characterizing a therapeutically meaningful/important event, and proceeds with the fine-grained examination of the process designated as alliance and its relation to small “o” outcomes. As well, these approaches use detailed “third party” observation-based procedures. Thus they are potentially replicable. And, each of these methods should provide definitions of the alliance much more resistant to “semiotic drift.” On the cost side of the ledger, while these methods to operationalize the alliance are independent of the type of treatments, these analyses yield process descriptions that have context-dependent features. The alliance process that is related to confrontations, interpretations, repairing a miss-understanding, or negotiations of a challenging homework assignment will each contain a different blend of features, some specific to context, while others may be generic across the events. It is as yet uncertain if a common micro-alliance factor can be distilled, or if we will end up with a very fragmented variable. As well, these methods represent different lenses for viewing alliance-as-process. While such “kaleidoscopic vision” has many attractions, to make these observations useful we would need to develop a procedure to label the different aspects of the alliance (to avoid confusion) and such a task will be challenging. And, of course, every one of these methods is very labor intensive. Lastly, as clinically important as these close-up visions of the alliance can be, clearly, there is also a strong need for a concept/method that encompasses a broader time horizon—for therapist feedback among other important uses.

Future Directions

While each of the projects reviewed above provides some remedies to the problems identified, clearly none of them provides the full answer. If this were not the case, there would be indications that the number of kinds of assessment used would be starting to winnow down in favor of one of these methods or some combination of these approaches. Alternatively, we would be observing some evidence that there is a growing consensus on a more complete definition of the concept of the alliance in line with one of these proposals. In fact, the opposite is happening. The alliance is operationalized in research using an ever increasing variety of assessment methods (Flückiger, Del Re, & Horvath, Citationin press), and each of the solutions reviewed above adds to the de facto list of operational definitions of the concept.

Achieving a higher level of consensus on a comprehensive common factor framework for the therapy relationship would go a very long way toward facilitating the development of the “science of the alliance” Bordin (Citation1994) called for. Such a framework would need to include not only the alliance but, at the minimum, the other empirically proven effective relationship elements (e.g., empathy, congruence, genuineness, etc.). There is good evidence that distinct components of the therapy relationship exist and play significant roles in therapy (Norcross, Citation2002, Citation2011). There is also evidence that many, if not all, of the “relationship [elements] that work” are common factors insofar as they play a role across a broad spectrum of different treatments. But there is a practical vacuum in the literature addressing questions about the relations among these elements, both from the conceptual and from the empirical perspective: How much do these elements overlap or contribute to each other? Relational elements such as alliance, empathy, warmth, and genuineness work at different levels, and represent different kinds of abstractions. Some are more like personal qualities, others infer behaviors or interactive accomplishments such as collaboration. It seems very likely that a comprehensive model of the relationship would need to accommodate hierarchical (i.e., some variables may contribute to, or be the result of, others) as well as complementary links among the elements (Horvath, Citation2011a).

The history of the alliance, its strengths and challenges, strongly suggests that “top-down” conceptualizations involving common factors do not seem to generate a substantial following. Common factors acquire substance by virtue of consensus. The alliance is “many—albeit related—things” because without consensual support, it resists unilateral attempts to define it (Horvath & Bedi, Citation2002). Likewise, well-thought-out scholarly attempts to create a comprehensive generic model of psychotherapy have had limited impact on the field (e.g., Castonguay & Beutler, Citation2005; Grawe, Citation2004; Orlinsky & Howard, Citation1987; Wampold, Citation2001). In fact, in a round table discussion among the leading thinkers in psychotherapy integration, the participating experts were not only unable to agree on what such a generic theory might look like, but most also showed very limited enthusiasm or confidence that such a “top-down” theory could eventually emerge (Norcross & Goldfried, Citation2005).

Instead of proposing a ready-made solution to the challenges facing this line of research, what seems to be needed is a renewal of the conversation about a theory of the relationship as a common ingredient. In 2006, the journal Psychotherapy made a call for a special section to commence this discussion. Eight experts were invited to comment on the “current status and future directions” of alliance research (Samstag, Citation2006a). The contributions were diverse and challenging, but among them almost all of the issues raised in this review surfaced in some form. Most notably, Hatcher and Barends (Citation2006) called for a “ … return to theory … to help alliance research.” Unfortunately, this lively discourse has halted during the last decade. It seems to me that the time is appropriate and the need is pressing to renew the call for such a conversation among researchers active in the field. The past decade of research, apart from its signal achievements, has helped to clarify some of the issues that need most urgent attention in such a conversation. I propose that priority should be given to the following topics:

Should elements of the therapy relationship be re-classified? Are alliance, collecting client feedback, repairing alliances, warmth, empathy, etc. the same kinds of variables? Can we find some level of consensus to separate variables that are attributes of a person (of the therapist or client), therapist-initiated actions or conditions, and collaborative achievements? Perhaps what is needed is a different kind of classification to take account for the different nature of some of the relationship variables.

Generate hypotheses that address the question of how some of the important relationship variables relate to each other. Do some of the therapy elements “feed” or support, perhaps reciprocally influence each other?

There needs to be a discussion aimed at the clarification of and distinctions between the relational elements that are common to all forms of therapy, and those that are specific to forms of treatment. Bordin (Citation1979) suggested that alliance is generic to all therapies and the differences are in the “kinds of tasks and goals.” It is likely the case, based on what we have learned since, that we need a more nuanced approach and perhaps a focus on concepts like collaboration (as a generic component) and to reconsider the need for tasks, goals, and bonds as exclusive “targets” of alliance.

In practice, alliance (and some other relationship variables), when assessed from different sources (self-report, observation), yield results that are poorly correlated. We need to discuss if this should be considered a method problem (i.e., inadequate translation of instruments), or is it the case that in situations when one gathers information on interpersonal relationship, the phenomenological data (self-report) and observations made by independent sources address essentially different underlying variables.

As noted earlier, alliances have been investigated using a wide variety of time scales. It seems that both micro and macro perspectives (as well as some in-between) are each useful. Should we re-label to make the distinctions among these more clear since there is no evidence to suggest that there is a simple additive relationship between what is measured at different time intervals?

In a similar vein, alliance conceptualizations focusing on negotiation and consensus both seem to yield important insights. Should we re-label these as different concepts? At the same time, we could discuss if “rupture” is a useful signifier for what is being investigated (strain?).

Discuss the practical standards for minimum shared of variance among instruments purporting to assess the same variable. Is setting the bar at a minimum of 51% shared variances among measures purporting to assess the same concept reasonable? Would it make sense to recommend some core referents as “anchors” to assist the instrument construct validation process?

Realistically, a conversation on these topics is not expected to yield a comprehensive framework for the common relational elements in psychotherapy, at least in the short run. Rather, I am proposing a process to engage some of the active members of the research community to work toward a greater consensus on some of these issues. A fully developed comprehensive framework for the shared, generic, components of the therapy relationship may be a distant project. But any forward progress in the direction of making this body of work more cohesive, clarifying and refining the core meanings of the concepts we investigate, would benefit our core mission: Generating knowledge to better serve our clients.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Comprehensive reviews of various aspects of what has been accomplished can be found in Norcross (Citation2011), Muran and Barber (Citation2010), and elsewhere.

2 Following Bordin’s (Citation1979) and Luborsky’s (Citation1976) example I shall use the terms “helper” and “therapist” (likewise “helpee” and “patient”) interchangeably to reflect the notion that the alliance is a ubiquitous feature not only of various forms of therapy but also in other interpersonal helping relations as well.

3 The numbers quoted are based on the search of the electronic databases PsyInfo, ERIC, and EBCSO; they include both peer-reviewed publications and unpublished dissertations in psychology and psychotherapy, but do not include a complete list of psychiatric, education, nursing, and social work journals and dissertations.

4 For a more extensive exposition on the differences between a narrative and persuasive definition, see Horvath (Citation2011a).

5 By drift I mean that if test “A” shares 50% of variance with test “B,” and a new test “C” is constructed to share 50% of variance with “B,” then the shared variance between “A” and “C” (and the rest of the pool) will be likely less than 50%. And so on, with the future generations of instruments.

6 For example, no stable differences in alliance–outcome relation were found among different frequently used instruments (Horvath & Bedi, Citation2002; Horvath et al., Citation2011; Horvath & Symonds, Citation1991).

References

- Abend, S. (2000). The problem of therapeutic alliance. In S. T. Levy (Ed.), The therapeutic alliance (pp. 1–16). Madison, WI: International Universities Press.

- Ahn, H.-N., & Wampold, B. E. (2001). Where oh where are the specific ingredients? A meta-analysis of component studies in counseling and psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 251–257. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.251

- Alexander, L. B., & Luborsky, L. (1987). The Penn helping alliance scales. In L. S. Greenberg & W. M. Pinsoff (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 325–356). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Antaki, C. (2008). Formulations in psychotherapy. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen, & I. Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis and psychotherapy (pp. 26–42). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Aron, L. (1996). A meeting of minds: Mutuality in psychoanalysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Bachelor, A. (1988). How clients perceive therapist empathy: A content analysis of “received” empathy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 25, 227–240. doi: 10.1037/h0085337

- Bachelor, A. (1995). Clients’ perception of the therapeutic alliance: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(3), 323–337. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.42.3.323

- Baldwin, S. A., Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2007). Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 842–852. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842

- Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1978). The relationship inventory: Later development and adaptations (8, 68). University of Waterloo. Retrieved from: JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology.