Abstract

Objective: The main objective of this study was to explore the relationship between alliance and treatment outcome of substance use disorder (SUD) outpatients in routine care. Attachment, type of substance use, and treatment orientation were analyzed as potential moderators of this relationship.

Method: Ninety-nine SUD outpatients rated their psychological distress before every session. Patients and therapists rated the alliance after every session. At treatment start and end, the patient completed the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT), and the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR-S). Data were analyzed using multilevel growth curve modeling and Dynamic Structural Equation Modeling (DSEM).

Results: The associations between alliance and outcome on psychological distress and substance use were, on average, weak. Within-patient associations between patient-rated alliance and outcome were moderated by self-rated attachment. Type of abuse moderated associations between therapist-rated alliance and psychological distress. No moderating effect was found for treatment orientation.

Conclusions: Patients’ attachment style and type of abuse may have influenced the association between alliance and problem reduction. A larger sample size is needed to confirm these findings.

Clinical and methodological significance of this article:

Alliance does not predict symptom improvement for substance use disorder (SUD) patients in psychological treatment to the same extent as for other patient groups, a finding in line with results from earlier studies and meta-analyses.

The patient’s attachment orientation and type of abuse may moderate the influence of the alliance on outcome. Assessing the patient’s attachment orientation at treatment start may help the therapist to tailor her/his interventions.

The variability of the associations between alliance and outcome for different patients, independently of treatment orientation, makes studies of other moderating variables of interest.

It may be important for the therapist to monitor her/his own alliance experience as this may predict treatment development.

The association between alliance and outcome in psychological treatment is well established (Flückiger et al., Citation2018). Studies have shown a moderate but consistent relationship between alliance and treatment outcome, independent of therapy methods, therapists, most patient groups, raters, culture, measurement methods, and research designs. The most recent meta-analysis found a correlation between patient-alliance and outcome in face-to-face psychotherapy of r = .278 (Flückiger et al., Citation2018).

It is likely that the relations between symptom improvement and alliance depend on moderators like patient characteristics, treatment form and type of problems (Zilcha-Mano et al., Citation2016; Zilcha-Mano & Errázuriz, Citation2015). Some researchers have questioned the direction of the alliance-outcome association, arguing for reverse causation in the sense that symptomatic improvement may cause increased alliance and subsequent symptom reduction. Although most studies have found that alliance predicts symptom improvement in the next session even if previous symptom improvement is controlled for, the question is still open (Falkenström et al., Citation2016; Zilcha-Mano et al., Citation2014).

Criticism has been directed towards research designs for studying alliance-outcome associations, arguing that they are not sufficiently sophisticated to allow for an understanding of the complex interactions in the therapeutic process (e.g., Lorenzo-Luaces & DeRubeis, Citation2018). Particularly, it is important to distinguish between alliance-outcome associations between patients and within patients (Coyne et al., Citation2019b; Falkenström et al., Citation2016; Zilcha-Mano, Citation2017). Conceptually, between-patient alliance levels are likely to be at least partly indicative of patients’ trait relational capacities that influence their perception of the alliance and their ability to utilize the therapeutic interventions. Within-patient improvements in the alliance, on the other hand, may imply corrective relational experiences (e.g., Castonguay & Hill, Citation2012), which in turn may cause improvement in symptoms (Coyne et al., Citation2019b; Zilcha-Mano, Citation2017). Within-patient deterioration in alliance may represent alliance ruptures, which are likely to lead to deterioration in symptoms if not resolved (Falkenström et al., Citation2016; Safran & Muran, Citation2000).

In studies of the trait-like aspect of the alliance, it may moderate outcome in interaction with e.g., personality problems (Falkenström et al., Citation2013), number of depression episodes (Lorenzo-Luaces et al., Citation2014), and other characteristics such as symptom severity, treatment length, treatment orientation, and feedback (Zilcha-Mano & Errázuriz, Citation2015). Current alliance research often focuses on the role of the alliance as a mechanism of change (Constantino et al., Citation2002; Coyne et al., Citation2019b) or as a facilitator for different treatment techniques.

Studies of associations between patient-rated alliance and different outcomes in the treatment of SUD patients have indicated lower correlations than in treatments with other patient groups. In the most recent meta-analysis, the correlation between alliance and outcome for SUD patients, based on 29 studies, was r = .14 (Flückiger et al., Citation2018), implying a significantly lower association than for other patients. Common outcome measures for studies included in meta-analyses were substance use, abstinence, depression and other symptoms, global mental health, and retention in treatment/dropout. Flückiger et al. (Citation2018) point out that the SUD samples included in their meta-analysis were highly variable. SUD patients form a heterogeneous group, often with various psychiatric and personality-related problems, e.g., co-occurring psychiatric disorders (e.g., Grant et al., Citation2004a; Grant et al., Citation2004b; Kessler, Citation2004). Sometimes, it may be unclear what the target of the treatment is for these patients. Rogers et al. (Citation2008) reported that the alliance had more effect on the psychiatric symptoms than on substance use for adolescents and young adults in SUD treatment. A study on traumatized women with SUD showed no relationship between alliance and outcome on substance use, but decreased symptoms of PTSD (Ruglass et al., Citation2012).

In mixed samples, containing both SUD patients and patients without substance abuse, a 10% increase of SUD patients (other than alcohol) in the samples decreased the alliance-outcome correlation by .01 (Flückiger et al., Citation2013). One reason could be that the use of substances may damage neuro-biological systems that are required for optimal relational capacity and mentalization, thus hindering the patient’s constructive use of the therapeutic relationship (Bates et al., Citation2002). Flückiger et al. (Citation2013) also stress the importance of socio-economic status, minority status and specific drugs and the interaction between them as potential moderators of the alliance-outcome association in treatments for SUD patients.

Generally, patients’ assessment of the alliance has been found more important than the therapists’ ratings for predicting outcome in SUD treatments (e.g., Cook et al., Citation2015; Crits-Christoph et al., Citation2011). There are a few studies showing the therapist alliance to be a stronger predictor of outcome. Meier et al. (Citation2006) found that therapist alliance ratings predicted dropout for SUD patients, but the patient alliance ratings did not. Knuuttila et al. (Citation2012) found an association among SUD outpatients between the working alliance as rated by the therapist in the first session and the patient’s percentage of abstinent days at baseline, together predicting treatment retention. The therapists’ alliance ratings were higher for patients whose treatment continued than for those whose treatment was discontinued.

It is probable that the patients’ pretreatment characteristics moderate the significance of the therapist-patient alliance for symptom reduction. A potentially moderating variable may be the patient’s attachment. Commonly, adult self-rated attachment is expressed on two orthogonal dimensions, anxiety and avoidance. Low scores on both dimensions indicate secure attachment. High scores on one or both dimensions indicate insecure attachment. Patients’ attachment orientation has been found to be correlated with the strength of the alliance (Diener & Monroe, Citation2011; Eames & Roth, Citation2000). Secure attachment is associated with a stronger alliance, whereas insecure alliance is related to a weaker alliance. A meta-analysis by Levy et al. (Citation2018) suggests that securely attached patients have better psychotherapy outcome than insecurely attached patients. They are also generally more compliant to treatment (Dozier, Citation1990). Patients with high scores on the anxiety dimension show worse outcomes in psychotherapy, while the picture for those with high scores on the avoidance dimension is less conclusive (Levy et al., Citation2018; Slade, Citation2016).

A recent review of Schindler (Citation2019) confirms a link between insecure attachment and SUD. He points out that the use of substances may be an attempt to cope with attachment deficits. He also suggests that an insecure attachment may be a consequence of substance abuse, e.g., through destroying current relationships and hindering the patient to form new close relationships.

One of the questions of this paper is whether attachment orientation moderates the association between alliance and symptom improvement. Patients with a secure attachment may have greater initial trust in the therapist, and they will probably follow the therapist’s suggestions and recommendations better, leading to better outcome. However, it is probable that the need of patients with insecure attachment to have a good alliance is stronger, and thus it may function as a change mechanism for them. In a study of CBT for young persons with substance abuse, Zack et al. (Citation2015) found that the alliance-outcome association was stronger for individuals with an insecure attachment history than for individuals with a more secure attachment history. It is probable that patients with insecure attachment may be more in need of corrective relational experiences but also more likely to experience ruptures in the therapy relationship.

Another potential moderator of the alliance-outcome association is the type of drug that the patient uses (Flückiger et al., Citation2013). Flückiger et al. found that the use of drugs other than alcohol decreases the relationship between alliance and outcome. We have not found any other studies exploring the type of substance abuse as a moderator of the alliance-outcome relationship.

Meta-analyses (Flückiger et al., Citation2012; Horvath et al., Citation2011) have not in general found treatment orientation to be a moderator of the effect of alliance on outcome. However, Barber et al. (Citation2001) found that alliance predicted patient retention differentially across three different treatments of SUD. For patients given individual drug counseling, higher levels of alliance measured at session 2 were associated with increased retention, while the alliance measured at session 5 did not show any relationship to retention. In supportive expressive therapy, there was no relationship between the alliance measured at session 2 and retention, while the alliance at session 5 was associated with increased retention. However, in cognitive therapy, higher levels of alliance measured at both session 2 and 5 were associated with decreased retention.

The main objective of the present study was to explore the relationship between alliance and treatment outcome measured as psychological distress and changes in substance use, and to analyze some potential moderators of the alliance-outcome association for SUD outpatients. Earlier studies have suggested that the association is weak and varying for this group. We tested three factors as potential moderators: patients’ self-rated attachment, type of substance use, and treatment orientation. They were analyzed between- and within patients. We hypothesized that securely attached patients would have higher alliance ratings, but that the association between alliance and outcome would be stronger for insecurely attached patients. The analyses of drug type and treatment orientation were explorative without hypotheses.

Method

Patients

The patients in the study were recruited during May 2011 to March 2014 at one outpatient unit of dependency disorders within a county council (60.5%) and two outpatient centers for SUD treatment in the social service of two municipalities (39.5%) in Sweden. Out of 172 patients who could have been included, 119 patients agreed to participate. The reasons for not participating were that the patients found the procedure too complicated or they did not want to participate in any kind of study. In some cases, the therapists regarded the patient as not being able to participate because of serious mental illness, poor physical condition or language problems. Among the 53 not included, therapist evaluation data were reported for 46 patients. These patients did not differ from the participating patients in terms of gender, age, and therapist-reported substance use.

Descriptive data of the 119 patients were given by the therapists on the CORE Therapy Assessment form. Of these, 99 patients completed the sufficient number of questionnaires to be included in the present study. Ninety-three percent of the patients were born in Sweden (based on 94 patients, for five no information were given). The mean age was 34.4 years (range 16–64, SD = 14.6), for men 32.9 years (n = 79, range 16–64, SD = 14.2) and for women 40.7 years (n = 20, range 17–57, SD = 14.7). When treatment started 42% were employed, 18% were students, and 40% had no current occupation, i.e., they were unemployed, on sick leave or retired. Fifty-nine percent were living together with a partner, the original family or a friend.

The responsibility for SUD treatment in Sweden is shared between the county councils and the municipalities. Individuals with SUD who receive medical treatment, counseling, or psychological treatment at the county council dependency disorder units can be treated by physicians, psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers. These patients generally get SUD diagnoses according to ICD-10 or DSM-5 by a physician, a psychiatrist or a psychologist, and in some cases also other psychiatric diagnoses. Individuals who receive psychological treatment at the municipal SUD outpatient centers will mainly be treated by social workers and psychotherapists. They do not usually receive an ICD-10 or a DSM-5 diagnosis; however their substance abuse has generally been assessed according to their results on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) (see below).

Of the 99 patients, 61 had an ICD-10 diagnosis and of these 54 had an SUD diagnosis. The most frequent SUD diagnoses were alcohol dependence (n = 26), alcohol withdrawal syndrome (n = 8), opioid dependence (n = 8), alcohol abuse (n = 5) and other psychoactive substance dependence (n = 3). In addition to the SUD problems, the patients’ most common problems, as rated by the therapists at treatment start (), were anxiety/stress, depression, somatic problems, self-esteem, and interpersonal relationships. The twenty excluded patients did not differ in psychological distress () or in educational level (). A more comprehensive description of the patients is given in Gidhagen et al. (Citation2017).

Table I. Therapist ratings of patients’ problems/concerns at treatment start (from mild = 1 to severe = 4). For all 99 patients included in this study and also for the 20 patients that agreed to participate but did not complete the forms required to be included.

Table II. Patients’ educational level at treatment start for the 99 patients included in this study and also for the 20 patients that agreed to participate but did not complete the forms required to be included.

Therapists

Seven social workers, four women and three men, served as therapists for the study. They were all trained in Motivational Interviewing (MI) (Miller & Rollnick, Citation1991) and Coping Skills Training/Relapse Prevention (Marlatt & Donovan, Citation2005; Monti et al., Citation1989). Four were also trained in the Community Reinforcement Approach (Hunt & Azrin, Citation1973; Meyers & Miller, Citation2001) and three in psychodynamic therapy (Abbass et al., Citation2014; Frederickson, Citation1999), of those two therapists were trained in both of the last-mentioned methods. The therapists had an average experience of six years (2–16 years) working with SUD treatment and an average of 8 years (0–17 years) of previous experience of psychological and psychosocial treatment. Their mean age was 49.6 (range 35–60). The therapists received supervision for 24 of the 99 patients.

Treatments

Motivational Interviewing (MI), Relapse Prevention (RP), Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA), Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Psychodynamic Therapy (PDT), psycho-educative interventions, crisis intervention, supportive therapy, and counseling were the treatment methods provided, alone or in different combinations. The therapists selected the most appropriate method or combination of methods that they mastered, and they ticked the treatment(s) provided in the CORE End of Therapy form.

For the statistical analyses the different methods and combinations of methods have been combined to three treatment orientations named directive (including RP, CRA, and CBT), reflective (including PDT and relational psychotherapy), and supportive (including psycho-educative interventions, crisis intervention, supportive therapy, and counseling). MI was used in addition to other treatments and was not used for the classification. For a minor part of the patients, it was not possible to classify their treatment into a specific orientation and they were labeled as “not clearly defined”. The majority of the patients (74%) were given directive treatment, 15% reflective treatment, 7% supportive treatment and 4% treatments were not defined. The average treatment length was 31 (SD = 31) weeks for the directive treatments, 75 (SD = 68) weeks for the reflective treatments, 16 (SD = 18) weeks for the supportive treatments and 2 (SD = 2) weeks for treatments that were not defined. If the statistics are based on the number of sessions, directive was given for 65% of the sessions, reflective for 32% and supportive for 3%.

Instruments

Working alliance inventory (WAI; Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989)

In its original form, WAI consists of 36 items. In this study patients’ ratings of the alliance were measured with Working Alliance Inventory – Short form Revised (WAI-SR; Hatcher & Gillaspy, Citation2006), which consists of 12 items and measures the therapeutic alliance on a 7-point Likert scale. Since the therapist-rated version of the WAI-SR was not validated at the time the study started, the therapists’ ratings of the alliance were measured with Working Alliance Inventory – Short Form (WAI-S; Tracey & Kokotovic, Citation1989). We will refer to the measures as WAI-P and WAI-T. The items can be summed up to three subscales: bond, task, and goal. The instruments have shown adequate reliability and validity, as demonstrated for WAI-SR by Falkenström et al. (Citation2015) and WAI-S by Hatcher et al. (Citation2019). The questionnaires were scored by both the patient and the therapist immediately after every session. The internal consistency, evaluated at the first session, for the patient form WAI-SR was α = .93 and for the therapist form WAI-S α = .95.

The clinical outcomes in routine evaluation – outcome measure (CORE-OM; Evans et al., Citation2002)

Psychological distress was measured before each session (except the first, when it was completed after the session) using the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM), a patient self-report measure with 34 items measuring psychological distress experienced during the preceding week on a 5-point scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Most of the time”. The items cover four major problem areas/domains: well-being, problems (anxiety, depression, physical problems, and trauma), functioning (general functioning, close relationships, and social relationships) and risk (to self and others). CORE-OM is problem-oriented in that higher scores indicate greater distress. The summed score may range from 0 to 40, as the mean of all 34 items is multiplied by 10. The instrument in its Swedish version (Elfström et al., Citation2012) has shown an internal consistency of α = .93–.94 and test–retest reliability of .85. The internal consistency of the CORE-OM in this study, as evaluated at the first session, was α = .95.

CORE therapy assessment form and end of therapy form (Evans et al., Citation2002)

On the CORE Therapy Assessment form, completed at intake, and the End of Therapy form, completed at treatment end, the therapist provided information about referral, patient demographic data and the nature, severity and duration of presenting problems. On the latter form, the therapist also reports the result of the treatment, the number of sessions, and which types of treatment(s) he/she provided.

Experiences in close relationships (ECR; Brennan et al., Citation1998)

The original Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) form consisted of 36 items. In this study patients’ global attachment orientation was measured using the short form of the self-report attachment questionnaire (ECR-S; Wei et al., Citation2007). Wei et al. (Citation2007) tested internal consistency for both the original and the short form of ECR, finding them to be equal. ECR-S has been translated into Swedish and modified by Broberg and Zahr (Citation2003). In the ECR-S, patients are asked to focus on their closest relationship, in this study classified in six categories: mother, father, sibling, child, partner, and friend. The ECR-S has items categorized in two subscales (dimensions): anxiety and avoidance. The anxiety dimension assesses individual differences in fear of rejection and abandonment, and need for approval from others. The avoidance dimension assesses individual differences in fear of intimacy and interdependence, and need for self-reliance and unwillingness for self-disclosure. There are six items for anxiety and six for avoidance, scored from 1 to 7. The results are presented as scores on the two continuous dimensions of anxiety and avoidance. The patients filled out the ECR-S questionnaire at the beginning and the end of the treatment. Testing for internal consistency in this study, we got for the ECR-S form, as evaluated from the first session, an internal consistency of α = .88. For anxious attachment, the internal consistency was α = .91, and for avoidant attachment α = .83.

Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT; Babor et al., Citation2001)

AUDIT is an instrument for identifying persons with hazardous and harmful patterns of alcohol consumption. It was developed by the World Health Organization as a method for screening for excessive drinking and to assist in brief assessment. The instrument is consistent with ICD-10 definitions of alcohol dependence and harmful alcohol use. The Swedish version has been found to have a good test–retest reliability of 0.93 (Bergman & Källmén, Citation2002). In this study, AUDIT is used as a self-report questionnaire and showed, for the first session, an internal consistency of α = .91.

AUDIT consists of 10 items and has a scoring range from 0 to 4. Cutoff scores for hazardous or harmful alcohol use in the AUDIT form of 10 items are 8 for men and 6 for women (Bergman & Källmén, Citation2002). The short version AUDIT-C (Bush et al., Citation1998) consists of the three first AUDIT items with a maximum score of 12 and measures current alcohol consumption. In this study AUDIT-C was used to measure change in alcohol consumption at treatment end. The AUDIT-C cutoff scores for hazardous consumption of alcohol are 5 or higher for men and 4 or higher for women (Berman et al., Citation2017).

Drug use disorders identification test (DUDIT; Berman et al., Citation2005)

DUDIT is an instrument for identifying persons with problems related to drugs and their consumption patterns. The instrument consists of 11 items and has a scoring range from 0 to 4, showing for the Swedish version a Cronbach α = .80 for the total score (Berman et al., Citation2005). The internal consistency for DUDIT, as evaluated at the first session of the present study, was α = .96. There is also an extension of DUDIT called DUDIT-E (Berman et al., Citation2007). This study only includes the first part of the extended form (DUDIT-Ed), where the patient ticks the type of drugs being used. The most frequently used drugs were cannabis (n = 33), anxiolytics/hypnotics (n = 25), analgesics (n = 19), opiates (n = 14), and amphetamine (n = 11). Out of the 49 patients using drugs at least twice to four times per month, 20 used only one drug, 12 used two, and 17 used three or more drugs. The combination most ticked for was cannabis together with anxiolytics/hypnotics (n = 16).

The cutoff scores for the DUDIT form of 11 items is 6 for men and 2 for women (Berman et al., Citation2017). The cutoff values for AUDIT and DUDIT given above are those recommended by the Swedish National Guidelines for SUD treatment (National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2019).

The first four DUDIT items, with a maximum score of 16, relate to drug use and is named DUDIT-C (Sinadinovic et al., Citation2014a). DUDIT-C was used in this study to measure change in drug use at treatment end. The DUDIT-C cutoff score for a possible problematic use of drugs was set to 1 or higher (Sinadinovic et al., Citation2014b).

Procedure

Patients who were referred or self-referred for psychological treatment at the three SUD outpatient centers were asked to participate. If the patient accepted to participate, he or she received an envelope containing the CORE-OM, WAI-P, ECR-S, AUDIT, and DUDIT/DUDIT-E forms to be completed after the first session. Before every following session the patient completed the CORE-OM, while the WAI-P form was completed immediately after each session. At treatment end the patient completed the ECR-S, AUDIT, and DUDIT/DUDIT-E a second time. All questionnaires were filled in by paper-and-pencil.

The therapists filled out the CORE Therapy Assessment Form at treatment start and the CORE End of Therapy Form at the termination. The WAI-T form was filled out after every session. The study has received approval by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (2011/165–3). All patients and therapists were informed about the study and gave their written consent for participation. Patients were told they would receive the same treatment if they chose not to participate. The therapists did not have access to patients’ questionnaires. Patients were assigned to therapists consecutively subject to their availability.

Statistical Analyses

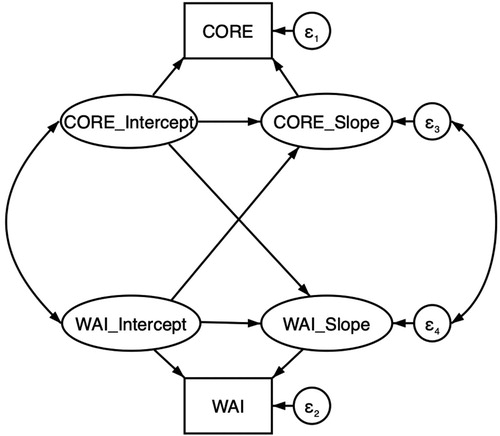

The relationships between initial attachment orientation, psychological distress and different types of substance use on the one hand and outcome on the other were analyzed based on ratings on ECR-S, CORE-OM, AUDIT, and DUDIT at treatment start. Analyses were done on within- and between-patient levels separately, with between-patient models estimating stable trait-like differences between patients in alliance while within-patient models estimating state-like changes or fluctuations over time (Zilcha-Mano, Citation2017). Between-patient analyses used multilevel growth curve modeling (Singer & Willett, Citation2003). Specifically, we used a model that combines growth curves for two variables simultaneously, called a Parallel Process Growth Curve Model (; Cheong et al., Citation2003). As can be seen from , the slopes of both variables are regressed on (1) the intercepts of the same variable, thus adjusting for regression towards the mean, and (2) the intercept of the other variable, which tests the impact of initial level of CORE-OM/WAI on change over time in the other variable. Finally, the slopes of CORE-OM and WAI are allowed to correlate, which then tests whether change in these variables tend to go along with each other (beyond any relationship due to initial states).

Figure 1. Bivariate parallel process growth curve model for CORE-OM and WAI, with regressions among random intercepts and slopes. The observed variables WAI and CORE are predicted by random intercepts and slopes. The random slopes are, in turn, regressed on random intercepts, representing the relationships between initial values and changes over time in each variable. ε1 and ε2 are the within-patient error terms, while ε3 and ε4 are the between-patient residual terms.

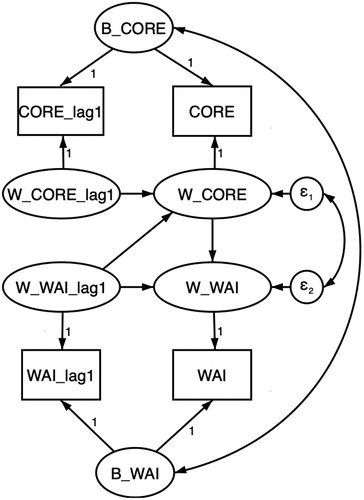

Within-patient analyses were done using Dynamic Structural Equation Modeling (DSEM; Asparouhov et al., Citation2018). DSEM is specifically developed to model relationships among variables within persons over time, combining information on a time-series level for many subjects simultaneously. Traditionally, time-series analysis has been used in single-subject designs to model within-person fluctuations over time. For instance, Vector Autoregression (VAR) is used to study cross-lagged relationship among two variables within a single subject. However, with panel data, i.e., when several subjects are measured repeatedly, VAR cannot be used. There are ways of aggregating the results of many VAR analyses (e.g., Ramseyer et al., Citation2014; Tschacher & Ramseyer, Citation2009), but DSEM accomplishes this in a single model by separating between- and within-person variances using random effects.

As such, DSEM is a kind of Multilevel Model (MLM), but with two important differences to traditional multilevel models: (1) random effects can be modeled for both predictors and outcome variables, and (2) lagged effects are modeled using latent variables. These two additions are essential for avoiding the so-called dynamic panel bias, which arises when regressing a variable on its own lagged component, while using manual methods for separating within- and between-patient components (Falkenström et al., Citation2017; Nickell, Citation1981). Thus, DSEM solves a problem in regular MLM when lagged variables are tested.

A basic bivariate DSEM model is depicted in . As the Figure shows, the observed values for the two variables, in this case WAI and CORE-OM for all patients at all time-points (with data set up in long format), are decomposed into within- and between-patient components using latent variables. The within-patient component represents fluctuations over time in WAI/CORE-OM, while the between-person component represents the stable differences among patients in these variables. The way this is done is similar to regular MLM, although here random intercepts are estimated for two variables simultaneously, while in regular MLM random effects are usually only estimated for the dependent variable. The within-person components are further decomposed into present and lagged components, to avoid the problems associated with manual lagging (see above). The present components (i.e., WAIt and CORE-OMt) are then regressed on their own lagged components (i.e., WAIt regressed on WAIt-1 and CORE-OMt on CORE-OMt-1). The effect of most interest is the path from WAIt-1 on CORE-OMt, which represents the effect of alliance in the previous session (t-1) on symptoms in the following week (scored immediately before session t). Finally, WAIt, which represents the alliance in session t, is regressed on CORE-OMt, which represents the effect of symptoms in the week before the session, thus adjusting for the hypothesized reverse causal effect of symptoms on alliance. The within-patient part of the DSEM model is thus a kind of cross-lagged panel model, which is the most appropriate way of analyzing panel data with lagged effects (Falkenström et al., Citation2020).

Figure 2. Path diagram of Bivariate Dynamic Structural Equation Model of the relationship between alliance (WAI) and psychological distress (CORE). Between-patient components (B_CORE and B_WAI) are estimated as latent variables (random intercepts). Within-patient components are estimated as latent deviation scores (W_WAI and W_CORE), and lagged versions of within-patient components are also estimated as latent variables (W_WAI_lag1 and W_CORE_lag1). Finally, ε1 and ε2 are the within-patient error terms.

Between-patient moderators were grand mean centered to facilitate interpretation. The attachment dimensions anxiety and avoidance were added simultaneously, together with their interaction term. Throughout the Result section we have used alpha = .05 as the limit for the significance level. For analyses indicated as non-significant, they thus have p > .05. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0, Armonk, NY, USA), Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, Citation2017), and Mplus version 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2017).

Results

The results are presented first with descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses, followed by analyses of alliance change over treatment and effects of the baseline values of the three potential moderators (attachment, type of substance use, and treatment orientation) on how the alliance changes over treatment. After these background analyses, the relationships between alliance and treatment outcome is presented for psychological distress and for substance use. Finally, the influence of the three potential moderators on the alliance-outcome association is assessed with regard to reduction in psychological distress and substance use.

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

shows the initial and final scores for patient-rated alliance (WAI-P), therapist-rated alliance (WAI-T), patients’ psychological distress (CORE-OM), patients’ reports of current alcohol consumption (AUDIT-C) and drug use (DUDIT-C), and the two patient-rated attachment dimensions (ECR-S). Of the 119, 99 patients completed at least two CORE-OM and WAI-P forms and the initial ECR-S form. For the other instruments, there was data attrition to various degrees as shown in .

Table III. Initial and final mean scores on WAI-P, WAI-T, CORE-OM, AUDIT-C, DUDIT-C (for those patients rating above cutoff on AUDIT and DUDIT at treatment start) and ECR-S anxiety and avoidance, and t-tests of differences between initial and final scores.

The mean ratings for both WAI-P and WAI-T increased significantly between the first and last sessions. The mean score on CORE-OM decreased significantly with a moderate effect size, i.e., patients’ average psychological distress had decreased at treatment end. Both alcohol consumption and drug use had decreased with large effect sizes. The mean ratings on the two ECR-S dimensions did not change significantly.

Correlations between initial, final, and mean alliance scores over all sessions and CORE-OM initial, final, mean, and gain scores are shown in . Significant correlations were found between mean WAI-P scores and initial, final, and mean CORE-OM scores, indicating that patients with high levels of psychological distress rated a lower alliance compared with those with lower CORE-OM scores. For the CORE-OM gain scores, there were no significant correlations with the alliance variables.

Table IV. Pearson’s correlations between WAI-P, WAI-T and CORE-OM variables (n = 97–99).

To assess the amount of nesting, three-level random intercept models without any predictors were estimated for WAI-P, WAI-T, and CORE-OM, and two-level models for AUDIT-C and DUDIT-C. For WAI-P, most of the variance was on the patient level (52.63%), with less variance on therapist (20.97%) and repeated measures (26.40%) levels. For WAI-T, most of the variance was on the therapist level (57.84%), with less variance on patient (16.78%) and repeated measures (25.39%) levels. For the CORE-OM, however, the variance for the therapist level in an unconditional (random intercept only) model was essentially zero. Most of the variance was on the patient level (74.77%) and the rest was on the repeated measures level (25.23%). For the AUDIT-C post-treatment measure, there was 16.19% variance among therapists, and for DUDIT-C there was 60.90% variance among therapists (these estimates changed very little if the pretreatment value was entered as covariate). Due to the amount of nesting on WAI-P, WAI-T, AUDIT, and DUDIT, control for therapist-differences seem warranted and were used in analyses involving these instruments.

Changes in Alliance Over Treatment

To find the form of growth in the alliance variables, linear, quadratic, and loglinearFootnote1 growth curve models were compared using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; with lower values indicating a better tradeoff between model fit and parsimony). For both WAI-P and WAI-T, the loglinear model had the lowest AIC (WAI-P: ΔAIClinear-loglinear = 47.60, ΔAICquadratic-loglinear = 5.98; WAI-T: ΔAIClinear-loglinear = 17.48, ΔAICquadratic-loglinear = 16.62).

In a second step, baseline variables for the three moderators were entered as predictors of intercepts and slopes of the loglinear growth models. The continuous ECR variables anxiety and avoidance were entered, grand mean centered, together with their interaction term. Results of this analysis showed a main effect of avoidant attachment predicting lower initial patient-rated alliance (coefficient = −0.15, SE = .07, p = .02, 95% CI [−0.28, −0.022]), while the interaction between avoidance and anxiety predicted higher initial patient-rated alliance (coefficient = 0.09, SE = .04, p = 0.02, 95% CI [0.015, 0.16]). The meaning of the interaction was that in the context of low attachment anxiety, high avoidance predicted low initial alliance. However, with larger attachment anxiety, the prediction of lower alliance from higher avoidance disappeared.

For therapist-rated alliance, the interaction between anxiety and avoidance significantly predicted initial alliance level (coefficient = .07, SE = 0.02, p = .004, 95% CI [0.02, 0.11]). The meaning of this interaction was explored, with a similar interpretation as for patient-rated alliance – i.e., low anxiety and high avoidance predicted low initial alliance (and a tendency for high anxiety and low avoidance to also predict lower initial alliance). In addition, there was a significant interaction effect between anxiety and avoidance on change in alliance over time (coefficient = −0.03, SE = 0.01, p = .02, 95% CI [−0.06, −0.00]), which showed that patients high on avoidance and low on anxiety improved most in terms of therapist-rated alliance.

Regarding treatment orientation, there were no differences between treatments in patient-rated alliance (neither in initial value nor in change over time). Reflective and supportive therapies had lower initial therapist-rated alliances than directive treatments (reflective = −0.50, SE = 0.21, p = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.90, −.09]; supportive −0.53, SE = 0.25, p = .03, 95% CI [−1.02, −0.05]), but no significant differences in change over time. There was no effect of type of substance use on either intercept or slope of WAI-P or WAI-T (all p-values > .14).

Alliance and Psychological Distress Outcome

Within-patient relations

To test the prediction of next-session CORE-OM from working alliance scores, the DSEM model shown in was first tested. The results of this model showed that patient-rated alliance did not predict next-session symptoms significantly (coefficient = −0.03, SE = 0.02, p = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.08, 0.01]). Symptom scores from the prior week, however, predicted patient-rated alliance significantly (−0.31, SE = 0.04, p < .001, 95% CI [−0.38, −0.24]). The results were similar for therapist-rated alliance (WAI-Tt-1 → CORE-OMt: −0.02, SE = 0.02, p = .20, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.02]; CORE-OMt → WAI-Tt: −0.19, SE = 0.04, p < .001, 95% CI [−0.26, −0.12]).

Between-patient relations

The parallel process growth curve model showed that initial WAI-P predicted the slope of change in WAI-P over time (coefficient = −0.15, SE = 0.07, p = .04, 95% CI [−0.30, −0.01]). However, the intercept of CORE-OM did not predict the slopes of WAI-P or CORE-OM, and the slopes of WAI-P and CORE-OM did not correlate significantly. The results were the same for WAI-T, the intercept of WAI-T predicted the slope for WAI-T (−0.24, SE = 0.08, p < .01, 95% CI [−0.38, −0.09]), but none of the other random effect regressions were significant.

Alliance and Substance use Outcome

AUDIT-C and DUDIT-C at post-treatment (adjusted for AUDIT-C/DUDIT-C at pretreatment and for therapist effects) were regressed on average alliance scores for patients whose initial score on AUDIT and DUDIT was above the cutoff. The only significant finding was for WAI-T predicting AUDIT-C at post-treatment (−1.42, SE = 0.67, p = .03, 95% CI [−2.73, −0.11]).

Moderators of the Within-patient Association between Alliance and Outcome Concerning Psychological Distress

First, we estimated a random slopes model for the DSEM within-patient alliance-outcome prediction model, so that the WAIt-1 → CORE-OMt path was allowed to vary among patients. This model showed that there was indeed significant variation among patients in the alliance-outcome association (WAI-P: 0.05, SE = 0.02, p < .001, 95% CI [0.01, 0.10]; WAI-T: 0.01, SE = 0.01; p < .001, 95% CI [0.00, 0.05]). Thus, there was significant variation among patients in the effect of alliance on next-session symptom distress, motivating the search for moderators.

Attachment

Moderation of the alliance-outcome relationship by attachment was tested by adding the ECR-S anxiety and avoidance variables, grand mean centered, together with their interaction term, as Level-2 predictors of the random effects (intercepts for WAI and CORE-OM, plus the slope of the alliancet-1 → CORE-OMt prediction). For WAI-P, the interaction between anxiety and avoidance dimensions was significant (−0.06, SE = 0.02, p = .002, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.02]). The interaction should be interpreted as patients with either high values on both anxiety and avoidance dimensions, or low values on both, had stronger alliance-outcome predictions. Simple slopes tests at one standard deviation above/below the average showed that when both anxiety and avoidance were low, the WAI-Pt-1 → CORE-OMt coefficient was −0.17 (SE = 0.06, p = .001, 95% CI [−0.31, −0.05]), and when both attachment dimensions were high the coefficient was −0.16 (SE = 0.06, p = .002, 95% CI [−0.29, −0.05]). However, the WAI-Pt-1 → CORE-OMt coefficient was non-significant when both attachment dimensions were on the sample average (−0.05, SE = 0.04, p = .17), when anxiety was high and avoidance low (0.05, SE = 0.10, p = .30) and when anxiety was low and avoidance high (0.11, SE = 0.11, p = .16). For WAI-T, none of the moderators significantly predicted the alliance – outcome association.

Type of substance use

For WAI-P, the within-patient alliance-outcome prediction did not differ significantly between patients who used drugs and patients who only used alcohol. For WAI-T, there was a significant difference between those patients who used only alcohol and those who used drugs or both drugs and alcohol (−0.15, SE = 0.07, p = .01, 95% CI [−0.29, −0.02]). Simple slope analysis showed that the effect of WAI-T on next-session CORE-OM was only significant for those who were using drugs or both drugs and alcohol (−0.14, SE = 0.06, p = .01, 95% CI [−0.25, −0.03]) while for those who were using only alcohol this effect was absent (0.02, SE = 0.05, p = .36).

Treatment orientation

There was no significant moderation of the within-patient alliance-outcome relationship by treatment orientation for either WAI-P or WAI-T.

Moderators of the Alliance-Outcome Association Concerning Substance Use

Attachment

There were no significant moderations by attachment of the alliance-substance use reduction relationship.

Type of substance use

There were no significant moderations by type of substance use of the alliance-substance use reduction relationship.

Treatment orientation

There were no significant moderations by treatment orientation of the alliance-substance use reduction relationship.

Discussion

The results in this study confirm and strengthen the conclusions from previous studies and meta-analyses (e.g., Flückiger et al., Citation2012; Flückiger et al., Citation2018) of a weak association between alliance and outcome for SUD patients. Although the patients showed outcome improvements, i.e., significant reductions in psychological distress and substance use, in parallel with increased alliance ratings, the role of alliance for outcome was weak and complex. These results differ from findings of associations between alliance and outcome in most other patient groups and treatment settings, and it is important to understand how they can be explained. The variability among the therapies concerning the alliance-outcome association was large, and the aim of the analyses in this study was to test potential moderators of this association.

There were differences in initial alliance level and alliance development between patients with different attachment. Patients who initially scored high on the avoidance dimension scored significantly lower alliance at treatment start but had a better improvement of the alliance than other patients. Patients with avoidant attachment are often difficult to get into treatment and it is a challenge to avoid therapy dropout. One reason of the improved alliance for these patients could be that they were treated by experienced therapists who responded in flexible and sensitive ways to their relational difficulties (Slade, Citation2016). Another reason could be that these patients have an initial skepticism to treatment that becomes mitigated when they experience positive results.

The dynamic structural equations model analysis (DSEM) modeling of the session-to-session association between lagged patient-rated alliance and changes in psychological distress did not show a significant relation, albeit it was close to significant. An association was, however, found between symptom ratings at one session and alliance ratings at the next session. Such reverse relations have been found also in other studies of alliance and outcome (e.g., DeRubeis & Feeley, Citation1990; Webb et al., Citation2014). Likely, they indicate that increased alliance in these patients to a large extent is an effect of experiences of reduced mental suffering.

The effect of the alliance on the outcome of substance use could only be evaluated as the difference of the initial and final scores as we had no session data on substance use. We found that the therapist-rated—and not the patient-rated—average alliance scores predicted the reduction in alcohol use. This finding is in contrast to most other studies showing that the patient-rated alliance is more important for outcome in SUD treatment (e.g., Crits-Christoph et al., Citation2011). It can be assumed that patients being abstinent during the treatment will contribute to higher alliance scores from the therapist. The therapist may perceive the patient as motivated and focused on sobriety or normal use of alcohol.

The results of the DSEM session-to-session analysis of patient-rated alliance and psychological distress showed a large variation between patients, indicating that different subgroups of patients might have different alliance-outcome patterns. A weak average effect and large variation may suggest that in some therapies the relationship may be positive (strong alliance leading to better outcome) and in some therapies it may even be negative (strong alliance leading to increase in symptoms or problems). Thus, it might be meaningful to explore moderators of the alliance-outcome association.

We first studied the importance of the patients’ attachment scores. The analyses showed that for patients with either low or high scores on both the attachment dimensions anxiety and avoidance, there was a significant association between patient-rated alliance and the psychological distress reported at the next session. The result for patients with low scores on both, indicating a secure attachment, is in line with previous findings (Levy & Johnson, Citation2019) showing that for these patients, the experience of a constructive collaboration may give impetus to symptom alleviation and perhaps also better problem solving outside therapy. The finding for patients with high scores on both dimensions, indicating a fearful attachment, can possibly be understood by the strength of these patients’ suffering from psychological distress, favoring commitment to bring about change. Gidhagen et al. (Citation2018) found that SUD patients with fearful attachment scored significantly higher on psychological distress at treatment start, as compared to the securely attached patients.

For these patients, increased alliance may be a corrective emotional experience. Schindler and Bröning (Citation2015) and Schindler (Citation2019) suggest that the therapeutic relationship in the treatment of SUD patients can help the patient to develop more attachment security. The dyadic collaboration gives an opportunity for the patient to learn how to regulate emotions, cope with emotional distress, change his or her representations of the self and others, and to improve the capacity for mentalization. The SUD treatment requires the patient to be abstinent, which is a great challenge since it forces the patient to leave his or her usual coping strategies, i.e., the substance use, at the same time as establishing a collaborative relationship with the therapist. The suffering experienced by patients who were initially classified as fearfully attached may possibly contribute to a stronger association between alliance and outcome. A somewhat similar result was found in Falkenström et al. (Citation2013) for patients with personality problems.

Type of substance use was a moderator for the association between the therapist-rated alliance at one session and patient’s scores of psychological distress at the next session. Patients who used only alcohol did not seem to have any effect of the alliance, while patients who used drugs seemed to benefit from the alliance – at least when assessed from the therapist’s perspective. Bertrand et al. (Citation2013) argued that clinicians might become more involved with patients whose drug problems are more severe. Patients with drug or mixed drug abuse often have severe psychiatric problems, making the therapeutic alliance more important for engagement in the therapeutic work to find relief of suffering and symptomatic improvement. For patients with only alcohol abuse, the alliance may not be as important for treatment success as other factors like their own decision to manage their problems. Finally, there was no moderating effect found for treatment orientation in the session-to-session analysis of alliance and psychological distress. Similar results were found by Flückiger et al. (Citation2018) and Zilcha-Mano and Errázuriz (Citation2015).

There was no significant effect of any of the three potential moderators on the alliance-outcome association when outcome was measured as reduction in substance use. Previous studies have also found lower effect of the working alliance on substance use, as compared to effects on psychological distress for SUD patients (e.g., Rogers et al., Citation2008). It could be that improved psychological well-being precedes and is a prerequisite for substance use reduction and abstinence. Another reason for the low effect may be the strength of the substance abuse, often considered as a chronic disease (e.g., Volkow et al., Citation2016).

However that may be, it is an important question for future studies to analyze factors that may explain the low and varying association between alliance and outcome in SUD therapies. Horvath (Citation2018) noted some years ago that the empirical knowledge about the importance of the alliance is not matched by any comprehensive and accepted theory. Divergent findings like those for SUD therapies may be important for developing viable theory about the significance of the therapeutic relationship.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of this naturalistic study is that it gives a real-world picture of patients, therapists, and treatments in routine care, implying high external validity which may help clinicians to more easily recognize and apply the results to their own practice. On the other hand, the heterogeneity and complexity of the patient sample, e.g., in terms of type of substance use and co-occurring disorders, as well as of treatment methods, which were commonly given in various combinations and without assessing treatment fidelity, limits its internal validity. A limitation of this study was that not all patients had ICD-10 or DSM-5 diagnoses. The patient sample size was fairly small and there was attrition on several variables, which also limits the strength of conclusions that can be made. Other limitations of the study are that it is based on self-rated questionnaires, which for SUD patients can be more problematic, since they are often – sometimes unconsciously—ambiguous towards reducing/quitting the abuse, possibly leading to fluctuations in motivation and alliance. There were also few measurement points of the substance use (treatment start and termination only), and they were made without being validated with any physiological measurements. A large number of associations were tested and there is certainly a risk of family-wise errors. We have attempted to interpret the results only using the stronger correlations. Finally, the study lacked follow-up measurements to assess different aspects of recovery. Our outcome measures of substance use at the end of treatment do not tell anything about long-term recovery, a topic which has been discussed recently by Bjornestad et al. (Citation2020).

Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research

The results of this study show that SUD patients’ attachment orientation and type of abuse to a certain extent influence the associations between therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychological distress and substance use. There is a need for more research on possible moderating variables affecting the associations between the working alliance and problem reduction in SUD treatments. The findings emphasize the need for more personalized treatments (e.g., Coyne et al., Citation2019a). It also seems important to monitor the therapeutic alliance at each session in order to discover problems in the therapeutic relationship, sometimes leading to ruptures and, in the worst of cases, dropout.

Given the large percentage of insecurely attached patients in the SUD population, it seems important to further investigate the role of the patient’s attachment orientation, and how specific considerations can be taken to obtain a good therapeutic relationship during the treatment of patients with an insecure attachment.

For the improvement of SUD treatments, it seems important also to widen the research perspective to factors other than alliance which may influence outcome and recovery.

Recovery from substance abuse may be a long process. Future studies should strive to assess outcome with long follow-up assessments. In addition, it is important to assess outcome using social, functional, and relational perspectives. It is highly probable that personality factors like attachment may have importance for change in factors that facilitate abstinence from substance abuse (Bjornestad et al., Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participating patients and therapists.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Cubic models were also tested, but the estimation did not converge.

References

- Abbass, A. A., Kisely, S. R., Town, J. M., Leichsenring, F., Driessen, E., De Maat, S., Gerber, A., Dekker, J., Rabung, S., Rusalovska, S., & Crowe, E. (2014). Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapies for common mental disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004687.pub4.

- Asparouhov, T., Hamaker, E. L., & Muthén, B. (2018). Dynamic structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 25(3), 359–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1406803

- Babor, T., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B., & Monteiro, M. G. (2001). AUDIT. The alcohol use disorders identification test. Guidelines for use in primary care (2nd ed.). WHO.

- Barber, J. P., Luborsky, L., Gallop, R., Crits-Christoph, P., Frank, A., Weiss, R. D., Thase, M. E., Connolly, M. B., Gladis, M., Foltz, C., & Siqueland, L. (2001). Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of outcome and retention in the national institute on drug abuse collaborative cocaine treatment study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.69.1.119

- Bates, M. E., Bowden, S. C., & Barry, D. (2002). Neurocognitive impairment associated with alcohol use disorders: Implications for treatment. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 10(3), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.10.3.193

- Bergman, H., & Källmén, H. (2002). Alcohol use among Swedes and a psychometric evaluation of the alcohol use disorders identification test. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 37(3), 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/37.3.245

- Berman, A. H., Bergman, H., Palmstierna, T., & Schlyter, F. (2005). Evaluation of the drug use disorders identification test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. European Addiction Research, 11(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000081413

- Berman, A. H., Palmstierna, T., Källmén, H., & Berman, H. (2007). The self-report drug use disorders identification test – extended (DUDIT-E): reliability, validity, and motivational index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(4), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.10.001

- Berman, A. H., Wennberg, P., & Källmén, H. (2017). ). AUDIT & DUDIT – Identifiera problem med alkohol och droger [AUDIT & DUDIT – Identifying problems with alcohol and drugs]. Gothia Fortbildning AB.

- Bertrand, K., Brunelle, N., Richer, I., Beaudoin, I., Lemieux, A., & Ménard, J. M. (2013). Assessing covariates of drug use trajectories among adolescents admitted to a drug addiction center: Mental health problems, therapeutic alliance, and treatment persistence. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(1–2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.733903

- Bjornestad, J., McKay, J. R., Berg, H., Moltu, C., & Nesvåg, S. (2020). How often are outcomes other than change in substance use measured? A systematic review of outcome measures in contemporary randomised controlled trials. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(4), 394–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13051

- Brennan, A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford Press.

- Broberg, A., & Zahr, M. (2003). Erfarenheter av nära relationer. Translation to Swedish of Experiences in Close Relationships (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998).

- Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory care quality improvement project (ACQUIP). Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

- Castonguay, L. G., & Hill, C. E. (2012). Transformation in psychotherapy: Corrective experiences across cognitive behavioral, humanistic, and psychodynamic approaches. American Psychological Association.

- Cheong, J., Mackinnon, D. P., & Khoo, S. T. (2003). Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5

- Constantino, M. J., Castonguay, L. G., & Schut, A. J. (2002). The working alliance – a flagship for the “scientist-practitioner” model in psychotherapy. In G. S. Tryon (Ed.), Counseling based on process research: Applying what we know (pp. 81–131). Allyn & Bacon.

- Cook, S., Heather, N., & McCambridge, J. (2015). The role of the working alliance in treatment for alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(2), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000058

- Coyne, A. E., Constantino, M. J., & Muir, H. J. (2019a). Therapist responsivity to patients’ early treatment beliefs and psychotherapy process. Psychotherapy, 56(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000200

- Coyne, A. E., Constantino, M. J., Westra, H. A., & Antony, M. M. (2019b). Interpersonal change as a mediator of the within- and between-patient alliance-outcome association in two treatments for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(5), 472–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000394

- Crits-Christoph, P., Gibbons, M. B., Hamilton, J., Ring-Kurtz, S., & Gallop, R. (2011). The dependability of alliance assessments: The alliance–outcome correlation is larger than you might think. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1037%2Fa0023668

- DeRubeis, R. J., & Feeley, M. (1990). Determinants of change in cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172968

- Diener, M. J., & Monroe, J. M. (2011). The relationship between adult attachment style and therapy alliance in individual therapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy, 48(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022425

- Dozier, M. (1990). Treatment use for adults with serious psychopathological disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 2(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400000584

- Eames, V., & Roth, A. (2000). Patient attachment orientation and the early working alliance – a study of patient and therapist reports of alliance quality and ruptures. Psychotherapy Research, 10(4), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptr/10.4.421

- Elfström, M. L., Evans, C., Lundgren, J., Johansson, B., Hakeberg, M., & Carlsson, S. G. (2012). Validation of the Swedish version of the clinical outcomes in routine evaluation outcome measure (CORE-OM). Clinical Psychological & Psychotherapy, 20(5), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1788

- Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., Mellor-Clark, J., McGrath, G., & Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardized brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180(1).1.51

- Falkenström, F., Ekeblad, A., & Holmqvist, R. (2016). Improvement of the working alliance in one treatment session predicts improvement of depressive symptoms by the next session. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(8), 738–751. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000119

- Falkenström, F., Finkel, S., Sandell, R., Rubel, J. A., & Holmqvist, R. (2017). Dynamic models of individual change in psychotherapy process research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(6), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000203

- Falkenström, F., Granström, F., & Holmqvist, R. (2013). Therapeutic alliance predicts symptomatic improvement session by session. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032258

- Falkenström, F., Hatcher, R. L., & Holmqvist, R. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis of the patient version of the working alliance inventory – short form revised. Assessment, 22(5), 581–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191114552472

- Falkenström, F., Solomonov, N., & Rubel, J. (2020). Using time-lagged panel data analysis to study mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research: Methodological recommendations. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(3), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12293

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D., Ackert, M., & Wampold, B. E. (2013). Substance use disorders and racial/ethnic minorities matter: A meta-analytic examination of the relation between alliance and outcome. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 610–616. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033161

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., Symonds, D., & Horvath, A. O. (2012). How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025749

- Frederickson, J. (1999). Psychodynamic psychotherapy: Learning to listen from multiple perspectives. Routledge.

- Gidhagen, Y., Holmqvist, R., & Philips, B. (2018). Attachment style among outpatients with substance use disorders in psychological treatment. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 91(4), 490–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12172

- Gidhagen, Y., Philips, B., & Holmqvist, R. (2017). Outcome of psychological treatment of patients with substance use disorders in routine care. Journal of Substance Use, 22(3), 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2016.1200149

- Grant, B. F., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Chou, S. P., Dufour, M. C., Compton, W., Pickering, R. P., & Kaplan, K. (2004a). Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(8), 807–816. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807.

- Grant, B. F., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Ruan, W. J., & Pickering, R. P. (2004b). Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(4), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361

- Hatcher, R. L., & Gillaspy, J. A. (2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300500352500

- Hatcher, R. L., Lindqvist, K., & Falkenström, F. (2019). Psychometric evaluation of the working alliance inventory – therapist version: Current and new short forms. Psychotherapy Research, 30(6), 706–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1677964

- Horvath, A. O. (2018). Research on the alliance: Knowledge in search of a theory. Psychotherapy Research, 28(4), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1373204

- Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022186

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223

- Hunt, G. M., & Azrin, N. H. (1973). A community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 11(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(73)90072-7

- Kessler, R. C. (2004). Impact of substance abuse on the diagnosis, course, and treatment of mood disorders: The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biological Psychiatry, 56(10), 730–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.034

- Knuuttila, V., Kuusisto, K., Saarnio, P., & Nummi, T. (2012). Effect of early working alliance on retention in outpatient substance abuse treatment. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 25(4), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2012.707116

- Levy, K. N., & Johnson, B. N. (2019). Attachment and psychotherapy: Implications from empirical research. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 60(3), 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000162

- Levy, K. N., Kivity, Y., Johnson, B. N., & Gooch, C. V. (2018). Adult attachment as a predictor and moderator of psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1996–2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22685

- Lorenzo-Luaces, L., & DeRubeis, R. J. (2018). Miles to go before we sleep: Advancing the understanding of psychotherapy by modeling complex processes. Cognitive Therapy Research, 42(2), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-018-9893-x

- Lorenzo-Luaces, L., DeRubeis, R. J., & Webb, C. A. (2014). Client characteristics as moderators of the relation between the therapeutic alliance and outcome in cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 368–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035994

- Marlatt, G. A., & Donovan, D. M. (2005). Relapse prevention. Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. The Guilford Press.

- Meier, P. S., Donmall, M. C., McElduff, P., Barrowclough, C., & Heller, R. F. (2006). The role of the early therapeutic alliance in predicting drug treatment dropout. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.010

- Meyers, R. J., & Miller, W. R. (Eds.). (2001). A community reinforcement approach to addiction treatment. Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. Guilford.

- Monti, P. M., Abrams, D. B., Kadden, R. M., & Cooney, N. L. (1989). Treating alcohol dependence: A coping skills training guide in the treatment of alcoholism. Guilford.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén.

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (2019). Nationella riktlinjer för vård och stöd vid missbruk och beroende [Swedish National Guidelines for Treatment of Substance Abuse and Dependence], Socialstyrelsen, Stockholm. Retrieved July 2, 2020, from https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/nationella-riktlinjer/2019-1-16.pdf

- Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1417–1426. https://doi.org/10.2307/1911408

- Ramseyer, F., Kupper, Z., Caspar, F., Znoj, H., & Tschacher, W. (2014). Time-series panel analysis (TSPA): Multivariate modeling of temporal associations in psychotherapy process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(5), 828–838. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037168

- Rogers, N., Lubman, D. I., & Allen, N. B. (2008). Therapeutic alliance and change in psychiatric symptoms in adolescents and young adults receiving drug treatment. Journal of Substance Use, 13(5), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890802092063

- Ruglass, L. M., Miele, G. M., Hien, D. A., Campbell, A. N., Hu, M. C., Caldeira, N., Jiang, H., Litt, L., Killeen, T., Hatch-Maillette, M., Najavits, L., Brown, C., Robinson, J. A., Brigham, G. S., & Nunes, E. V. (2012). Helping alliance, retention, and treatment outcomes: A secondary analysis from the NIDA clinical trials network women and trauma study. Substance Use & Misuse, 47(6), 695–707. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.659789.

- Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance: A relational treatment guide. Guilford Press.

- Schindler, A. (2019). Attachment and substance use disorders – Theoretical models, empirical evidence, and implications for treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00727

- Schindler, A., & Bröning, S. (2015). A review on attachment and adolescent substance abuse: Empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment. Substance Abuse, 36(3), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.983586

- Sinadinovic, K., Wennberg, P., & Berman, A. H. (2014a). Short-term changes in substance use among problematic alcohol and drug users from a general population sample. International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research, 3(4), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.7895/ijadr.v3i4.186

- Sinadinovic, K., Wennberg, P., & Berman, A. H. (2014b). Internet-based screening and brief intervention for illicit drug users: A randomized controlled trial with 12-month follow-up. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(2), 313–318. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2014.75.313

- Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press.

- Slade, A. (2016). Attachment and adult psychotherapy: Theory, research and practice. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 759–779). Guilford Press.

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC.

- Tracey, T. J., & Kokotovic, A. M. (1989). Factor structure of the working alliance inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1(3), 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.1.3.207

- Tschacher, W., & Ramseyer, F. (2009). Modeling psychotherapy process by time-series panel analysis (TSPA). Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 469–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802654496

- Volkow, N. D., Koob, G. F., & McLellan, A. T. (2016). Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1511480

- Webb, C. A., Beard, C., Auerbach, R. P., Menninger, E., & Björgvinsson, T. (2014). The therapeutic alliance in a naturalistic psychiatric setting: Temporal relations with depressive symptom change. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 61, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.015

- Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The experiences in close relationship scale (ECR) – short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701268041

- Zack, S. E., Castonguay, L. G., Boswell, J. F., McAleavey, A. A., Adelman, R., Kraus, D. R., & Pate, G. A. (2015). Attachment history as a moderator of the alliance outcome relationship in adolescents. Psychotherapy, 52(2), 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037727

- Zilcha-Mano, S. (2017). Is the alliance really therapeutic? Revisiting this question in light of recent methodological advances. American Psychologist, 72(4), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040435

- Zilcha-Mano, S., Dinger, U., McCarthy, K. S., & Barber, J. P. (2014). Does alliance predict symptoms throughout treatment, or is it the other way around. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 931–935. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035141

- Zilcha-Mano, S., & Errázuriz, P. (2015). One size does not fit all: Examining heterogeneity and identifying moderators of the alliance–outcome association. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(4), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000103

- Zilcha-Mano, S., Muran, J. C., Hungr, C., Eubanks, C. F., Safran, J. D., & Winston, A. (2016). The relationship between alliance and outcome: Analysis of a two-person perspective on alliance and session outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(6), 484–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000058