ABSTRACT

Background: Teachers’ limiting conceptualizations of students influence students’ learning opportunities. We analyze teachers’ professional conversations to understand how dialogues can expand teachers’ conceptualizations.

Methods: We examine professional dialogues from nine whole-school intervention meetings. Drawing on discursive psychology and activity theoretical notions of learning the study conceptualizes teachers’ collective assumptions as a lived ideology actively sustained by stabilization discourses. We analyze the discursive devices through which the teachers’ talk about their students limits/expands their sense of what is possible in their teaching and their dialogic effects.

Findings: Our analysis finds a range of discursive strategies that sustain or re-stabilize the lived ideology. Even when challenged by contrary evidence (e.g., surprises), dilemmatic tensions and reframing repair actions are found to close potential dialogic openings. Importantly, we identify a form of discourse that avoids immediate closure, characterized by sustained reflection on the students’ challenges developing a need to change. We term this reflexive noticing: it is enabled through sustained puzzle, constructing dilemmas as origin of change and discursive consciousness of stabilization.

Contribution: We illustrate why contrary evidence often fails to shift limiting conceptualizations about students and show the discursive mechanisms generating possibility knowledge. Implications for teacher learning are discussed.

Introduction

This study contributes to our understanding of the persistent problem of teachers’ limiting conceptualizations of their students which are known to shape those students’ learning opportunities in school (cf. Campbell, Citation2015; Dobbs & Arnold, Citation2009; Georgiou et al., Citation2002; Horn, Citation2007). There is now strong evidence that teachers’ conceptualizations about students can influence students’ learning opportunities. This is significant: research demonstrates that teachers often hold deficit models of students, characterized by low expectations, ascribing those to factors outside schools’ and teachers’ influence (Bannister, Citation2015; Hennessy et al., Citation2015; Horn, Citation2007; Jackson et al., Citation2017; Patterson et al., Citation2007; Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015; Thompson et al., Citation2016; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018; Virkkunen et al., Citation2012; Wilhelm et al., Citation2017). Our review of the research shows that when teachers attempt to offer new learning opportunities, they are consistently surprised at their students’ ability to engage with those (see e.g., Hennessy et al., Citation2016; Horn, Citation2007; Wilson et al., Citation2017). For example, in school mathematics, qualitative research has shown that teachers’ conceptualizations about students are highly consequential for their teaching-related decision-making, thereby ultimately impacting on students’ learning opportunities (Bannister, Citation2015; Horn, Citation2007; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Jackson et al., Citation2017; Louie, Citation2016). Wilhelm et al. (Citation2017) large-scale quantitative correlational study demonstrated that teachers’ explanations of sources of students’ difficulty were significantly related to students’ opportunities to participate in quality discussions in mathematics classrooms. Jackson et al. (Citation2017) pointed out that the relevance of these findings is not limited to mathematics but extends to other subjects as well, making them central in accomplishing ambitious educational reforms in general .Footnote1

These conceptualizations are not just about individual teacher beliefs. Research shows that groups of professionals in institutional settings have shared conceptualizations which can differ from or go beyond, participants’ individual beliefs (Horn, Citation2007; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Jackson et al., Citation2017; Opfer & Pedder, Citation2011; Sannino et al., Citation2016; Vrikki et al., Citation2017). Opfer and Pedder (Citation2011), in their extensive review of research on teachers’ professional learning and change, identified school-level beliefs about learning as some of the most important school-level influences. Not only do such prevailing limiting conceptualizations appear at the group/institutional level; recent research suggests that change toward discursive re-interpretation of teachers’ practice may also start at group, not individual, level (Vrikki et al., Citation2017). The inter-individual character of these conceptualizations highlights the need to study their shared discursively produced nature.

How can shared conceptualizations change? It is widely suggested that the collaborative professional conversations in which these shared conceptualizations are articulated are a key site for addressing them (Bannister, Citation2015; Louie, Citation2016; Horn, Citation2010; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018; Vrikki et al., Citation2017). This resonates with reviews of effective teacher professional development which highlight collaboration and discussion as key sources of teacher learning (see Hofmann, Citation2020), and with recent theorizations of learning as dialogic (Mercer et al., Citation2020; Resnick et al., Citation2015). However, recent research finds that teacher collaborative discussions are not automatically generative for teacher learning, nor are all discussions equally productive (Dudley, Citation2013; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Lefstein & Snell, Citation2011; Louie, Citation2016; Popp & Goldman, Citation2016; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018; Vrikki et al., Citation2017; Wilson et al., Citation2017).

Research has identified an “accumulated advantage,” whereby accomplished teachers are best positioned to engage in productive conversations with colleagues, while teacher communities who hold closed deterministic conceptualizations, defining themselves as un-agentic in addressing their students’ struggles, often engage in discursive practices which stabilize, rather than question and challenge, those closed conceptualizations (Horn, Citation2007; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2017). The dilemma is that while maintaining closed conceptualizations can help teachers cope with complex realities in difficult instructional circumstances (Engeström, Citation2007b; Lefstein & Snell, Citation2011; Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015), such stabilization also constrains teachers’ work and its development, in limiting what is seen as possible (Engeström et al., Citation2002).

This study contributes to the understanding about how breaking this “vicious circle of categorizing students in school” (Virkkunen et al., Citation2012) may become possible. It does so by studying a context where many students struggled, and teachers initially held, and collectively discursively reinforced, stabilizing conceptualizations of students but where in the context of a developmental intervention, it was previously shown that their closed conceptualizations were expanded, enabling them to envision alternatives (Engeström et al., Citation2002; Rainio, Citation2003; Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015).

Our analysis of these teacher conversations is framed by a theoretical framework focusing on examining stabilization and expansion in discursive and professional practice, drawing on discursive psychology and activity theoretical and dialogic theorizing of learning and change. Ultimately, the aim is to understand how these conversations can shift to enable teachers to expand their sense of what is possible in their teaching, with their students (Engeström, Citation2007b; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Sannino et al., Citation2016).

Before outlining our theoretical framework, we examine the literature to review what is known about expanding teacher conceptualizations and identify gaps in existing research.

Review of the literature

Our synthesis of the literature suggests that productive professional learning conversations focus on discussing problems of practice in a way that enables teachers to locate themselves as agentic in relation to those problems, however challenging (Bannister Citation2015; Horn, Citation2007; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Popp & Goldman, Citation2016; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018). With this, we mean that teachers discursively consider their work as related to student experience, leading to students’ experiences and learning being viewed as something teachers can act upon, rather than being outside their influence. Research suggests several key features of such productive professional learning conversations. They involve using rich representations of practice which link broad ideas about teaching to concrete examples (Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Popp & Goldman, Citation2016; Horn, Citation2010; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018) and students’ perspectives and experiences (Bannister Citation2015; Horn, Citation2007; Horn & Kane, Citation2015). Such conversations which make salient discrepant data, actively examine problematic/competing discourses and practices (Bannister Citation2015; Dudley, Citation2013; Horn, Citation2007; Louie, Citation2016; Popp & Goldman, Citation2016; Horn, Citation2010; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018), and do not shy away from examining failure (Dudley, Citation2013; Louie, Citation2016; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018). Research suggests that such conversations have the potential for teachers to expand their sense of the possible (Horn & Kane, Citation2015). However, professional conversations in busy schools often do not look like this.

The Horn (Citation2007) study, which analyzed teachers’ talk in two schools’ mathematics departments found that how teachers’ made sense of students’ difficulties mattered to how they engaged with reform. Teachers perceived a mismatch between ’their students’ and their capabilities, and the desired new curriculum and teaching practice. When teachers discussed this mismatch, their categorizations of their students influenced the solutions that could emerge from those conversations. When teachers considered their own role in their students’ struggles, they discussed the mismatch in terms of how they might alter their instruction. However, when closed deterministic categorizations of students went unchallenged the mismatch problem was constructed as one about students and their deficiencies, outside the teachers’ influence. Horn emphasizes that while teachers cannot change their students, developing more complex categorizations of students enabled the shifting of the problem space and teachers’ perceived agency to address it. Her later study (Horn, Citation2010) further found that the ways in which practice was shared in the conversations rendered aspects of classroom events visible or invisible for shared reflection: when teaching replays (recalling past instructional interactions) and rehearsals (anticipating future ones) were specific, extended, and emotionally involving, they helped the teachers to reconsider and revise their understanding of their problems of practice.

Drawing on Engeström’s activity-theoretical work, Horn and Kane (Citation2015) recent study suggests that teachers’ collaborative conversations about their practice can support teachers’ professional learning through expanding participants’ sense of what is possible. This is highly significant for practice, they argue, since “images of what is possible contribute to what [teachers] even attempt, along with the details of how they might undertake different practices”. In our study, we take up this key idea and develop a conceptual and operational framework for further analyzing the expansion of teachers’ sense of the possible.

This is not straightforward. While Horn (Citation2010, p. 255) found that even experienced teachers “willingly revise their ideas when they recognize their limits,” her later study found very different levels of productive articulation and agentic framing of teaching problems in different teacher communities. Moreover, the learning opportunities entailed in teachers’ conversations were related to teachers’ existing levels of rich practice. Professional conversations among teachers with greater existing involvement in ambitious practice were characterized by time spent on discussing problems of practice involving linking broad ideas about teaching with specifics of local practice, and consideration of students’ experiences and perspective. (They term these multivocal teaching replays and rehearsals.) However, other groups’ conversations involved minimal consideration of student perspectives and limited probing of issues and understandings. Horn and Kane interpret this as “an accumulated advantage developmental story,” calling for further research. They suggest that the widespread faith in teacher collaboration as a drive for improvement may be misplaced, concluding that in “teacher collaborative learning, the rich do indeed get richer.” (Horn & Kane, Citation2015, p. 414).

So while research has found that productive professional learning conversations are characterized by rich categorizations of students and problems of practice which consider students’ perspectives and render teachers as agentic in addressing students’ challenges, it has also found that they are not automatically able to engage in such conversations to expand their categorizations, and thereby their sense of what is possible. This matters since research finds that while teachers may not individually hold closed views about students, prevailing shared conceptualizations that are given voice in the collective conversations are influential for their professional learning opportunities and their thinking about teaching (Horn, Citation2007; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Jackson et al., Citation2017; cf. Opfer & Pedder, Citation2011).

These findings resonate with Popp and Goldman (Citation2016) who found that while knowledge building occurred in the professional conversations when teachers discussed assessment, when the teachers discussed teaching, their conversations typically involved little analysis of alternative perspectives or the impact of teachers’ actions on students. Others found that this limiting pattern is difficult to change. Vrikki et al. (Citation2017) found that even when teachers were using classroom evidence in their reflection, this was not linked with re-interpretation, evaluating and diagnosing practice and student thinking. Even when offered new interpretative frameworks to facilitate dialogues about students, teachers can learn to use those without their conceptualizations about their students as learners changing (Wilson et al., Citation2017). While the teachers in the study used the new interpretative framework in their discussions, they continued to express limiting understandings of students as learners.

Bannister (Citation2015) study demonstrates both the possibility, and the challenges, of shifting teachers’ conversational categories about students who initially struggle. Her analysis examines teachers’ framing (Goffman, Citation1974) of students’ struggles: their conceptualizations of problematic scenarios and potential solutions for those. It showed how teachers’ diagnostic framings (students’ struggles) and prognostic framings (possible solutions) were linked. Fixed student categorizations were associated with interventions expecting students to change. A similar phenomenon of teachers adopting un-agentic positions toward teaching problems is identified by Vedder-Weiss et al. (Citation2018) in the context of teachers discussing failure. They found that while failures provided a rich opportunity for learning, the potential was only partially realized by features of the shared discourse which prevented the teachers from delving more deeply into difficult but pertinent problems. They identified a range of unproductive discursive moves in the conversation. These involved defining the problem as un-solvable or normal. Interestingly, they showed that rushing to develop solutions, while pragmatic, often effectively hindered a deeper analysis of problems. This resonates with Dudley (Citation2013) who also suggests that “slowing down” teachers’ thinking and shared problem-solving is important but often does not happen.

Research shows, however, that when slowing down happens in professional learning, it can link with slowing down in teaching practice, enabling teachers more opportunities to explore and understand their students’ thinking and learning (Dudley et al., Citation2019). Bannister (Citation2015) also showed that teachers’ conceptual categories about students can and do change to become more open and complex. Bannister (Citation2015) study is promising in showing that it is possible to achieve sustained collaborative discussions which are characterized by open discussion, questioning of existing conceptualizations and co-construction of new ones. However, this change in their conceptualizations was not automatically immediately linked with changes in their solutions. After teachers’ diagnostic framings had shifted to more complex and contextualized understandings of students’ struggles, teachers initially continued to define those as outside their influence. This finding is supported by Jackson et al. (Citation2017) study of teachers’ diagnostic and prognostic framings. It similarly found that even when teachers discussed students’ challenges as something related to teaching—thereby locating themselves as responsible and agentic with regard to those challenges—they did not necessarily suggest solutions that would enable students to participate in rigorous classroom activity (in mathematics).

Louie (Citation2016) study illustrates how the change of such categorizations may be more nuanced than perhaps previously appreciated. She demonstrated how change does not happen as a complete shift from one kind of (closed) categorization to another (more open one), whereby existing meanings related to the current, limiting “commonsense” among the teachers simply disappear. Rather, the teachers in her study “were frequently caught in tensions between restrictive and inclusive discourses” (p. 10). (Her study relates to discourses about mathematical competence, but there is no reason to assume this would not relate to other areas of learning). Louie notes that while the existence of such tensions presents opportunities for teacher learning, the teachers studied often struggled to navigate the conflicts between restrictive and expansive discourses. Louie (p. 11) concludes that restrictive commonsense discourses, and more equity-oriented new open discourses, interact “in messy and complex ways that require careful study in order to understand how and what teachers learn”.

So the literature suggests that teachers’ collective conceptualizations about students and teaching matter because they can influence emergent solutions to students’ struggles and the extent to which teachers locate themselves as agentic in relation to those. When professional conversations are specific, sustained and involve consideration of students’ perspectives, teachers’ role and analysis of alternatives, they can contribute to expanding teachers’ sense of what is possible in their practice. However, research shows that shifting persistent limiting ways of talking about students’ experience and learning in a way that also leads teachers to suggest agentic solutions is rare and not fully understood. Even when teachers wish for change and have tools to work and talk together, professional conversations are often characterized by limited reflection of impact of teachers’ actions on students’ struggles—locating teachers as un-agentic—and limited analysis of alternative forms of practice.

The research reviewed here has demonstrated that the process by which change toward an expanded sense of the possible may or may not happen in these conversations is more complex than perhaps sometimes assumed. Our review found that teachers can develop more open conceptualizations of students without automatically developing more agentic solutions for new forms of practice that could support student learning (Bannister, Citation2015; Jackson et al., Citation2017). It further found that restrictive conceptualizations about students and practice are not simply replaced by expanded ones: rather, both continue to co-exist, and teachers can struggle to productively discuss and resolve conflicts between them (Louie, Citation2016). While the substance of teachers’ conceptualizations is important, research also found that discursive features of teachers’ conversations play a central role in hindering the expansive development in teachers’ conceptualizations (Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018). It is the discursive features of professional conversations that enable such expansive developments that we need to understand better.

Finally, it was found that the most productive professional conversations offering affordances for teacher learning may take place among those teachers already engaging in the most expansive and engaging forms of practice (Horn & Kane, Citation2015). This poses a puzzle for understanding how teachers’ limiting conceptualizations of students may open up: Teachers’ conceptualizations are shared and operationalized at the level of institutional professional conversations which influence those teachers’ practice. Yet, even when teachers wish for change, the professional conversations in which they participate have discursive features that hinder the identification of new solutions and expansion of those teachers’ sense of agency and “the possible” and can instead reinforce the existing closed conceptualizations.

Institutional lived ideologies, dialogue, and stabilization and possibility discourse

To fill the gap in existing research and better understand how the discursive features of professional conversations in institutional settings can expand teachers’ sense of the possible, we draw on three key theoretical concepts/frameworks: discursive psychology, particularly the concept of lived ideology (from now on: LI) developed by Billig and his colleagues, and culturally historical and dialogic theories of human interaction and development, particularly the concepts of stabilization and possibility knowledge introduced by Engeström (Citation2007b) and the concept of dialogue developed by Wegerif (Citation2020).

Instead of focusing on individual motivations/beliefs, discursive psychology starts from the assumption that knowledge is socially shared, and that dialogue and common sense that people share contain conflicting, even dissonant, themes. Billig et al. (Citation1988, te Molder, Citation2015) made an important distinction in what they termed as lived ideology, “part of the common sense of the everyday practices of a culture” or community, and intellectual ideology, which refers to “crystallized views of key thinkers” (Hepburn, Citation2003). They argue that whereas intellectual ideologies often aim for coherence and consistency, lived ideologies work through contradictions, dilemmas and inconsistencies of everyday life. Lived ideologies help people make sense of their lives, linking even possibly competing ideological underpinnings and common sense, and this is not necessary always inhibiting but enabling.

In this article, our use of the concept of lived ideology (LI) refers to a “common sense” that groups of people share in a certain historical time and local setting (such as a workplace). This does not mean that the teachers necessarily share a stable and permanent set of beliefs; it suggests that they recognize and use certain established ways of conceptualizing and understanding their professional practice and the contradictions or dilemmas it involves. These established shared ways of understanding and seeing are based on the reality of teachers’ work. Lived ideologies can thus protect participants: they can guard against contested issues being taken up (see Lefstein & Snell, Citation2011) and, in constructing current challenges as outside the teachers’ control, help cope in difficult institutional circumstances (Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015). However, not only surrounding material realities, but also conversational and institutional norms shape conversation patterns that become established in discursive communities (Dick et al., Citation2018; Hofmann & Ruthven, Citation2018). Explaining teacher professional learning requires understanding what, and how, local knowledge, problems and discursive features of conversations shape teachers’ practices and thinking in an institutional setting (Opfer & Pedder, Citation2011; Pyhältö et al., Citation2012).

Activity theory, theorizing how change happens in institutional practice, suggests that participants of an institutional practice, such as school, actively work to maintain stability as a way of dealing with a complex reality of their everyday practice (Engeström, Citation2007b). While such stabilization work is necessary to the functioning of an institution, and a way for teachers to cope with the realities they and their students face in challenging settings, such an “institutional common sense” also constrains teachers’ work and its development in limiting what is seen as possible (Engeström et al., Citation2002). The fixed and closed ways of talking about and defining problematic issues regarding students are seen here as examples of such stabilization work: they can simplify and freeze the complex and challenging reality in school (Virkkunen et al., Citation2012) to render it more manageable. Engeström (Citation2007b) argues that through global collective narratives about “our students,” the problematic is turned into a closed phenomenon that can be “registered and pushed around rather than transformed” (p. 271).

The literature review showed that breaking away from stabilizing practices and the discourses that support them can be difficult. Drawing on an extensive body of research on organizational change, Engeström and colleagues show that professional conversations among participants, in the context of a shared intervention effort to develop their work, can support such work (Engeström, Citation2007a; Sannino et al., Citation2016). This is in line with the discursive analytic view on language as producing social realities instead of just representing them (Engeström & Sannino, Citation2011, discussing Billig et al., Citation1988). However, as we have discussed, those dialogues often act as an instrument of stabilization in institutional practice, sustaining frozen conceptualizations, rather than instruments of change and creation of new conceptualizations.

Engeström (Citation2007b) calls for de-stabilizing practices in interventions through what he terms “possibility knowledge.” With this he refers to material/instrumental practices or tools developed in interventions, such as ways of naming or modeling activities or putting established meanings in movement. Research suggested that finding ways of facilitating an expansion in teachers’ sense of the possible is key to productive professional conversations. It also suggested that existing discursive and material tools did not always fully support such an expansion. In this article, we take up Engeström’s notion of possibility knowledge and operationalize it further, developing it into a research tool for analyzing professional discourses.

Based on Engeström’s work, we have discerned two parts of possibility knowledge. First, possibility knowledge needs a tool, a model or a concept that puts the lived ideology or stabilized practice in movement, and (potentially) opens it for dialogue and breaking away from old (in teacher professional conversations, articulating exceptions, questioning, surprises, and noticing new things, can be seen as such tools, see Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015). Yet, many recent studies have found professional dialogues resistant to destabilization even at the face of contradicting evidence. So, we interpret that the second part of the definition of possibility knowledge is that it needs to help to locate the speakers as agentic (cf. Engeström, Citation2007b; Sannino et al., Citation2016). Through this concept, we aim to identify a form of possibility discourse in the professional conversations which could open up and sustain such a perspective on practice which involves non-closed conceptualizations of students, and locates teachers as agentic in relation to their students’ struggles.

We therefore study the de-stabilizations and their consequences in those dialogues to establish whether and how those dialogues can hinder, or contribute to, a new instrumentality of change in an organization. Hereby, our work further develops, conceptually and operationally, the notion of possibility knowledge as a potential source of change in professional dialogues as we examine further how professional dialogues can move from stabilization to possibility discourse.

Our notion of “dialogue” hereby refers to conversations in which more than one idea or perspective is discussed. Conversations which give space to uncertainty and multiciplicity of perspectives give rise to what Wegerif (Citation2020) calls the “dialogic space.” It is such dialogic spaces from which new meanings can emerge in conversations: Wegerif et al. (Citation2020) argue that it is the holding together, and inter-animation, of different ideas or perspectives which leads to new insights. Such dialogic spaces link with learning and expansion of the sense of the possible in two ways. Engeström and Sannino (Citation2011) argue that the articulation of multiple, potentially tensioned, perspectives in the dialogue enables the recognition of contradictions in the shared practice which can drive change. Jointly articulating those through discursive actions can help actors make sense of and ultimately resolve those contradictions. Wegerif further (Citation2020) argues that also the participants themselves change, learn, through engagement in dialogic spaces: the willingness and capability to engage with alternative potentially tensioned perspectives or trying to figure out new perspectives from which things could be seen, is in itself a goal for learning.

Contextualizing the study: Research setting and earlier findings

Context: The intervention study and participants

In the school year 2000–2001, a longitudinal intervention study was conducted at a middle school in Southern Finland.Footnote2 The school was located in a disadvantaged urban area. The area had a significantly higher unemployment level than the regional average, and only 5% of the adult population of had higher education compared to 21% in the region as a whole. The average-sized school had ca 300 students, about 30% of whom were recent immigrants and refugees, mainly from Russia and Somalia. The school employed 27 full-time teachers, including the principal, all of whom participated in the project. Of the teachers, 21 were female and 6 male (including the principal). Their teaching experience ranged from newly qualified to experienced teachers. Due to ethical reasons, limited demographic data was collected about the participants. Key to the project was the participation of all teachers, including different subject specialists and special education teachers, allowing the group to be multi-voiced.

The intervention was theoretically based on the Change Laboratory Method (Virkkunen & Shelley Newnham, Citation2013), which follows the principles of the Developmental Work Research tradition (see Engeström, Citation2005). In this method teachers neither implement an intervention offered from the “outside”, nor do they simply discuss their practice. In the Change Laboratory Method a close analysis of the disturbances in the current practices and their historical and theoretical modeling form a basis for developing practice jointly between the researchers and the practitioners.

The intervention was an extension of a Change Laboratory intervention conducted in the school in 1998–1999 (see a detailed description of the first phase of the intervention in Engeström et al., Citation2002, also Sannino et al., Citation2016). In the earlier phase, the teachers had expressed their wish to integrate the tools of information and communication technology of the time into their instruction as a step toward new pedagogical practices with the aim of improving student engagement. Developing knowledge practices in the classroom formed the basis for the intervention that focused on developing new classroom practices with the teachers (Rainio, Citation2003).

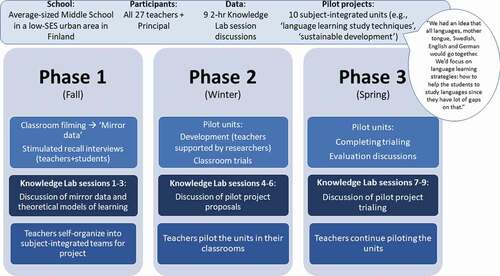

Our focus in this study is on nine change laboratory sessions where the teachers and the principal discussed and developed their schoolwork with the researchers (the timeline and content of the sessions are depicted in ). In Phase 1 (Term 1, Sessions 1–3), the participants watched and discussed selected video excerpts from their classrooms collected by the researchers (“mirror data”). Researchers collected classroom video-data in 21 lessons suggested by the teachers, which were used as “mirror data” in the teachers meetings to prompt discussion and analysis. Based on these discussions, the teachers selected topics they decided to start developing in their teaching. The teachers self-organized into small groups around these topics to design new pilot teaching units intended to spearhead change. The idea in these pilot teaching units was to integrate different subjects to investigate relevant phenomena through these subjects—a pedagogical approach which resonates strongly with the approach of “phenomenon-based learning” currently discussed in the context of Finnish curriculum reform (see Lonka, Citation2018).

In the second phase (Sessions 4–6, Term 2), before launching the pilot units, plans were discussed and developed together. Their subsequent classroom implementation was videotaped. Phase 3 (Sessions 7–9, Term 3) focused on evaluating the implementation. The fortnightly 2-h-long staff discussion sessions were videotaped and transcribed by a researcher. The data entails approximately 18 hours of video and 500 pages of transcript.

In this article, we analyze the discussions in all the nine laboratory sessions throughout the three phases. Talk in the first three sessions of the intervention was directed by the researchers to discuss the daily practices and everyday routines and events in classrooms, including teaching methods (Rainio, Citation2003). The researchers also took up dilemmatic or problematic situations visible in the video recordings from the teachers’ classrooms. Discussions in the second phase of the project (Sessions 4–6) focused on explicating and developing teachers’ plans for the pilot teaching units that were then implemented and tried out in their classroom work during the Spring. The final Sessions (7–9) involved evaluating and reflecting on the pilot. The teachers described their piloting experiences and learning, discussing how the objectives were met, the surprises they had faced and ideas for improvement.

Earlier findings

Our current study is motivated by earlier findings of the same intervention data, which we will shortly present before moving on to the research questions and findings of the current study.

A detailed discourse analysis of the first three laboratory sessions (1–3, Fall 2001) showed that the teachers’ talk about their students at the start of the project was very stabilizing (see Rainio, Citation2003) and that this stabilizing way the teachers talked about their work, and their students, had an effect on the collective discourse in that it hindered and diminished possibilities for seeing their work in alternative ways.

The study concluded that at the beginning of the intervention this teacher community had strong “lived ideologies” that dominated the change efforts even when the teachers themselves were motivated and willing to try new solutions (ibid). This resonates with the literature (cf. Bannister, Citation2015; Horn, Citation2007; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Louie, Citation2016; Horn, Citation2010; Wilhelm et al., Citation2017).

However, our later analysisFootnote3 of the intervention revealed that when the intervention proceeded and the teachers planned and carried out new ways of organizing and conducting their teaching, they started to use more complex conceptualizations of their students. They started to describe the students as embodied, even often engaged beings whose problems in school are something that the teachers can start to do something at. Upon closer examination, we observed that the teachers started to talk about “noticing” things from their experiences in the project, either in their students or the way things were done in their classrooms; they started talking about diverse possible reasons for their students’ problems, and considered those from the students’ perspective. We also demonstrated quantitative shifts in the way the teachers talked about their students during the intervention: positive talk about the students as capable participants in school life and learning increased significantly during the intervention (from 9 to 53 speech actions), as did positive talk of the students as “whole embodied beings” (from 18 to 120 speech actions, something that was depicted very negatively in early conversations).

What is central for our argument in this paper is that although the students and the circumstances in the school were “the same” as in the beginning of the project, and although the teachers had tried out alternative ways of working in their classrooms before, there was a remarkable change in the way the teachers talked about their students, despite the strong lived ideology visible in their talk. This resonates with findings from the literature emphasizing that while teachers cannot necessarily change their students, developing more complex categorizations of students enables the shifting of the problem space and teachers’ perceived ability to address it (Bannister, Citation2015; Horn, Citation2007; Horn & Kane, Citation2015; Horn, Citation2010).

However, these findings also suggest a potential extension to extant literature. Research has found that teachers who perceive their students to struggle, while locating themselves as non-agentic in relation to those struggles, do not always engage in productive professional conversations in which more open conceptualizations are developed (Horn & Kane, Citation2015; cf. Jackson et al., Citation2017), with discursive features of those conversations hindering such development (Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018). The fact that this appeared to have happened here makes this a highly significant dataset to study further. We wanted to understand better the discursive features that made such expansion possible in our data. Furthermore, the literature suggested that teachers often struggle when having to negotiate tensioned perspectives, when restrictive and expansive conceptualizations about students continue to co-exist (Louie, Citation2016). Our findings in 2015 also showed that even though there was a considerable shift in more positive and multi-vocal way of talking about students, the stabilizing ways of talking about the students continued to co-exist. We also wanted to look at this coexistence more closely to fill the knowledge gap: How, at the level of discourse, does the shift from stabilization discourse to possibility discourse (cf. Engeström, Citation2007b) take place, or not take place, in different instances of talk? As discourse, itself has features that impact what is said and how, we ask, apart from individual teacher beliefs and learning, what discursive devices played a role here? Therefore, in this paper, we focus on analyzing the discursive devices through which the teachers’ talk about their students shifts between what can be called ”stabilization discourse” and ”possibility discourse” (cf. Engeström, Citation2007b) and the effects this shifting has for the dialogue.

Research questions, methods, and data-analysis

Research questions

What “discursive devices” in the teachers’ talk do the work of maintaining a certain closed conceptualization of the students in the school (stabilization discourse)?

How does a shift from stabilization discourse to possibility discourse take place?

How is possibility discourse sustained in the dialogue?

The process of data analysis

First, we had to identify the suitable data corpus for close-up analysis since it is not possible to conduct detailed analyses of discourse of very large datasets. In our earlier analyses we had already identified all sequences of talk in the dataset (nine laboratory sessions in the first intervention year) in which the conceptualization of students was at hand (Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015) and had identified a total of 393 turns presenting conceptualizations of students (these turns/exchanges included one of these terms: The/Our/These students; The/Our/These kids/children; Class X; and [in Finnish a typical way of referring to a particular group in a normative way, simply:] “They”, Or a specific name of a student). Since our current focus was on the discursive devices maintaining or challenging those conceptualizations, we focused on this same sub-set. With the term “discursive device” we refer to “the micro-linguistic tools that people use in interaction in order to construct a particular version of the world and their relationship to it” (Mueller & Whittle, Citation2011, p. 189).

Initial outlining and coding phase: Identifying stabilizing and de-stabilizing speech actions

We first needed to identify stabilizing student talk within this body of data, as well as talk that potentially challenged this stabilizing student talk, to examine its effects on the teachers’ LI (lived ideology) and as evidence of what we call “possibility discourse” (cf. Engeström, Citation2007b). In our initial abductive reading between literature and the data, we noted that in the teachers’ talk of their students there were broadly two kinds of speech actions: (1) speech actions that stabilized and maintained the closed view of the students as an obstacle for change and (2) speech actions that articulated exceptions, openings or ruptures to this stabilized view of the students. In order to more systematically capture these types of speech actions, we operationalized them based on prior literature. The first type of stabilizing speech actions was analyzed in our earlier work (Rainio, Citation2003; Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015). Informed by Engeström (Citation2007b) concept of stabilization knowledge hindering development in organizations, we operationalized this as a talk that presented the described circumstance, conceptualization or categorization of students as frozen (cf. Virkkunen et al., Citation2012). Empirically, we identified stabilizing talk of students as talk that contains explicit statements about how “their students” are. This talk included discursive formulations such as Always; Here in our school; That’s a fact/It’s a fact; We all know our school/students and how things are; Would never; What will happen is what has always happened before; That is how things go here; Nothing we have done/tried has helped (can take different grammatical forms in Finnish); It has been like this for years. We then also identified and included talk with implicit or indirect expressions of how “their students” are. These were operationalized as “Surprise” talk since surprises about what their students did or how they were are predicated on normative prior expectations of how “those students” would be. This talk was identified as including wordings such as: Surprised/Surprising; Astonished/Astonishing; Strange; [I] Noticed; Occurred [to me]; Actually [which in Finnish expresses a surprise/change].

The markers through which the types of talk were identified, and references to data extracts that illustrate these markers in context, are described in . Therefore, all the data analyzed for this study contained a) reference to the students (, Line 1) and b) a formulation of an assumption in relation to “how their students are” (, Lines 2–3). Talks including (b) were hereby already seen to include a potential de-stabilization of the norm. Next step was to analyze all the identified turns/exchanges to see if indeed those assumptions about students were stabilized in the talk or whether any openings were present. If no opening was present, the data would be treated as stabilizing talk. Three kinds of openings were identified and used to signal data where potential de-stabilization was happening:

Surprise: being surprised that things with students were not as expected (markers already identified above);

Dilemma: discussing assumptions about students as in themselves somehow problematic (based on the analysis in Rainio, Citation2003, dilemma rhetorically contains elements of certain linguistic markers such as “but–but” structure of talk, “on one hand—on the other hand,” or for example, sentences that phrase dilemma in a speaker’s talk such as “I have been wondering”/“I don’t understand.”/“this bothers me”/I don’t understand why, or use of certain words such as problem, challenge, dilemma …) (see , Line 5);

Temporality: reference to temporal nature of the phenomenon, assumptions about students described as something that could change over time (“now”/“future”) (see , Line 6).

Table 1. Phase 1: identifying markers in the data analysis to identify episodes for close discursive analysis in phase 2

To avoid unduly fragmenting the data in a way that might not be empirically justified, the data was grouped to either stabilizing talk or de-stabilizing talk for the next step (we acknowledge gray areas exist). Data was analyzed in this and the other phases by both authors in parallel. Since our aim was not to count incidences, but to understand the nuanced differences in how conceptualizations of students get stabilized and frozen, or de-stabilized and opened up, in teacher dialogues, we discussed and compared each incidence. The next step, having identified these episodes, was to analyze this talk for the discursive devices that were used by the participants in those episodes to do the stabilizing/de-stabilizing. We will explicate this step next.

Second interpretative phase: Analyzing the discursive features (“discursive devices”) of stabilization and de-stabilization speech actions

In the second interpretative phase of our analysis, we focused more closely on the “discursive devices” (cf. Edwards, Citation2005) which the participants drew on in their talk in the as-identified episodes in both of these speech action types through continuously comparing examples of data with each other (see Silverman, Citation2006). These discursive devices we identified and their empirical operationalization form part of the findings from our analysis and are illustrated in more detail the data extracts and our discussion of those in the Findings section.

In relation to stabilization speech actions, this process identified two distinct main discursive devices teachers used in stabilizing a closed view of their students. What we named “status quo statements” reinforced the current situation, and the lived ideology, through defining it as inevitable (i.e., “things can’t be different because of how our students are”). “Moral and value statements” rendered it frozen through describing it as somehow morally desirable (i.e., “the teachers” duty is to respect how the students are’). Ultimately, both located the teachers as un-agentic in relation to change, stabilizing the lived ideology. These devices turned out particularly relevant for examining what was the difference between stabilization and possibility discourse.

Examining and comparing the instances of de-stabilizing speech actions more closely, it became evident that they contained diverse discursive features in relation to teachers’ surprise or articulation of puzzles. We now compared our initial understandings of the data with the literature. This analysis phase can be described as testing our earlier formed “working hypotheses” (in this case the two broadly different speech action types). A process of constantly comparing instances of data, findings and interpretations with earlier ones to create, refine and distinguish categories (cf. Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967; Silverman, Citation2006) proved essential for the analysis. We observed that among the talk containing above-identified “opening”-markers, there were speech actions, which recognized, and expressed surprise about, something new about the students, but in a way that seemed to maintain, or return to, a stabilized view of the students (i.e., “the students were able to do much more than I expected but I still would not do this again”). This demonstrated the need for yet another iteration: we needed to look at the different effects these different speech actions had for the conversation. This led to a significant new insight: the discovery of a new type of speech actions in addition to stabilization and de-stabilization, namely, re-stabilization.

This resulted in dividing the speech actions in three types instead of two (see in Findings). Particularly analyzing discrepant cases (LeCompte et al., Citation1993) helped to clarify the differences between the speech action types. Now it was possible to examine the discursive devices used not only for stabilization/de-stabilization but also for re-stabilization, a central element in understanding how a shift from stabilization discourse to possibility discourse may or may not take place in professional conversations. The way we operationally identified this talk as re-stabilizing or de-stabilizing is part of the findings of our study and is illustrated in detail in the Findings section.

Table 2. Summary of the main findings

Third phase: Analyzing the shift from stabilization discourse to possibility discourse

Only after we had been able to discern re-stabilization as a central new element in the teachers’ talk, could we answer our second research question of how a shift from stabilization discourse to possibility discourse takes place in the teachers’ talk in our data, and our third question of how de-stabilization was sustained in the discourse. We carefully examined the differences and similarities between speech actions that re-stabilized the LI and those that actually de-stabilized it. We observed that the de-stabilizing speech actions contained these following elements:

They expressed “surprises” and “noticing” new things (teachers’ own terms) or questioned the necessity of the closed nature of current practice (i.e., by puzzling over a dilemmatic aspect of one’s work)

and they located the speakers as agentic about [changing] the practice, destabilizing the LI.

In this analysis, we found that 1 and 2 did not necessarily go together: while the presence of (1) is the precondition of possibility discourse it is insufficient alone, the shift from stabilization to possibility discourse was only materialized if also (2) was present. We then constructed from the data different discursive devices through which the agency of the teacher was maintained in the talk (we have named these “reflexive noticing” containing such devices as sustained puzzle and discursive consciousness). Our goal was to identify discursive devices that are available to teachers in such conversations that have the potential of disrupting and opening up previously frozen conceptualizations of students. It is recognizing and capturing those differences of consequence, discursive features that can stop stabilization (and re-stabilization) that we are interested in. In our concluding we have described all the discursive devices in a way that would enable a replication of our analysis as well as, importantly, the use of these as-identified and conceptualized discursive devices in further analyses of other datasets.

Findings

What “discursive devices” in the teachers’ talk do the work of maintaining a certain closed conceptualization of the students in the school (stabilization discourse)? (RQ1)

Our data-analysis suggests that there are two main devices in use in the stabilizing student talk; we call these status quo statements and value or moral statements. It is important to illustrate how these are drawn on in the talk, since we identify differences in this later sessions. These discursive devices maintain and reinforce the lived ideology of the institution in that they legitimize current practice, and are opportunities for other speakers to express shared agreement.

Status quo statements establish certain patterns of student characteristics and behaviors as inevitable and deterministic:

Data Example A (Session 3, turns of talk 279–282)

A1. LEENAFootnote4 The answer to everything in this village is always social benefits, they are used to getting everything, so what do they bother doing anything themselves. This is seen in so many things.

A2. KIRSTI: It guides it.

In A1, Leena characterizes the students, and people in their community more generally, as not “being bothered to do anything themselves” since they are used to things being given to them. This is immediately supported by Kirsti (A2). Helen also takes this up (A3), offering further stabilizing support for the characterization of “students here in our school” as not cooperative, which Kirsti again backs up (A4):

A3. HELEN: And to add to what Kirsti said, I was thinking about the same because I’ve been in lots of schools after all, I’ve been in one school where I knew, there is an elementary school nearby and we collaborated a lot, I know that they used quite a lot of cooperative learning methods [at the elementary school], students had to think, so in my opinion using this [new] way of teaching was much easier at the middle school for those students than here in our school.

A4. KIRSTI: So it has to start really young.

Above, Leena, Kirsti and Helen are reasoning about why their students cannot be expected to take responsibility for their learning or engage in group learning tasks and collaboration, and why it is necessary to stick to more traditional learning tasks. They relate these reasons to the neighborhood (“in this village”), the school, and how this passive attitude guides their students’ behavior. Resonating with our earlier findings (Rainio, Citation2003), we argue that these arguments reflect a collectively formed and maintained lived ideology that maintains a status quo of their work environment as dissatisfying for the teachers.

Interestingly, there is an element of the possible de-stabilization in the above example. The teachers acknowledge that students’ engagement in cooperative methods is influenced by teachers’ practices, hence defining student characteristics as not deterministic. However, we argue, they still frame these characteristics outside their own influence as middle school teachers, contributing then to stabilization. We will return to this function of framing in the discourse in the next Section where we introduce our finding of the speech action type of re-stabilization.

While status quo statements establish the current situation as unavoidable, value/moral statements establish an aspect of the current situation as morally compelling: such as that for students, who are ’happy alone,’ their “personalities have to be respected,” and they cannot be asked to work in groups even if group work is being suggested as otherwise desirable:

Data Example B (Session 3, turns of talk 11–20)

B1. TANJA: Well actually one thing started bothering me, I was thinking about it in the evening at home while in the Sauna, Footnote5 when we started talking about working in pairs, that if someone is working alone they are at risk of being marginalized, in my opinion that’s not in any way a symptom of that and I think it was a bit funny to draw that into it. Marginalized students are totally different.

B2. Researcher: Say a bit more.

Above, Tanja (B1) expresses disagreement with the idea that if students refuse to work with others, they are at risk of being marginalized. She elaborates (B3):

B3. TANJA: I mean that if someone works alone, well it could be that their friend is away at that moment, or that they want to work alone, or that their friends are in a different class. Marginalized students, they have friends and it’s a bit of a bad thing when they have many and they aren’t even in school, or at least not in lessons, so I thought that was a bit funny.

B4. Researcher: That it didn’t ring a bell.

B5. TANJA: Not really, in my opinion.

B6. Researcher: Ok, what do others think?

Tanja argues that students are making agentic choices about wanting to work alone (turn B3). Kirsti (turns B7; B9) and Leena (turn B8) further elaborate this, supporting Tanja’s original claim:

B7. KIRSTI: Well I recall that I talked about this same thing then, when there was Reidar (a student) in the English lesson [in the mirror video data] and who was there, it’s not straightforward that those students who work alone are at risk of being marginalized.

B8. LEENA: Often it’s the best student in class.

B9. KIRSTI: That’s right.

The teachers argue later that the students’ personal choice to work alone needs to be “respected”: In Session 3, there is an extended discussion about students who work alone in the classroom even in group work situations, and the possible reasons behind that. The above is a segment of a longer conversation in which the teachers collectively construct a view in their talk that, like one of the teachers, Tanja, formulates it, “one must respect people’s personalities, children’s and adults” alike, and it shows from a person that they are content and happy alone, so they are then not marginalized’ (from Session 3, turn of talk 81).

Both extracts can be seen as examples of stabilization discourse in that they establish a view that group work cannot be expected of these students, and that there are factors outside teachers’ influence (wider local attitudes or students’ personalities) that explain the traditional model of not engaging with teaching, or with group work. This happens although the teachers take these issues seriously, often reflecting on them even at home (see Tanja above, turn B9).

Lived ideology is an important organizing element in professional work that helps people cope with challenging issues present in one’s work. Teachers need to select in the flow of daily classroom events which issues to be worried about, which questions to focus on, and what to let go of in order to manage the work. Reasoning based on lived ideology, such as in the presented examples facilitates this, but has stabilizing consequences, as shown above, rendering frozen current forms of practice. However, as our review of the literature showed, when teachers trial new things, new things do happen and are noticed, strong lived ideologies in communities notwithstanding. Next, we look at the “discursive devices” that make possible a more open conceptualization of the students in the school.

How does a shift from stabilization discourse to possibility discourse take place and what are its effects for the teacher dialogue? (RQ2)

As described, we operationalized the first element of the “possibility discourse” as talk that reports surprises and notices new aspects of the teachers’ work. This surprise talk becomes more salient as the intervention proceeds, and our analysis shows that it has the potential to challenge the status quo views of students, which in the earlier phase impeded alternative interpretations. In the following, we first explicate ways in which talk about surprise and noticing becomes discursively visible in the conversation before analyzing its effects—what the teachers discursively do with their surprise and noticing, particularly inasmuch as they relate it back to their conceptualizations of the students. Our examples in this Section are primarily from Sessions 4–6, where the teachers are in the process developing new teaching units, and from Sessions 7–9 where the teachers reflect on and evaluate those.

In Example C Hanna shares with the meeting what she describes as an “extraordinary event” about a student:

Data Example C (Session 7, turn of talk 290)

C1. HANNA: Now I have to tell you this one thing that we decided to share with you. We’re all here from this school and we all know our students: So, there was this extraordinary event.

In introducing the story, Hanna twice makes reference to “we all,” emphasizing how they all know what “their students” are like. As she continues her story, she once more makes reference to “we [you] all know,” the teachers’ shared knowledge about their students. The surprise about the story is also expressed as collective in the story: “we” were surprised.

C2. [HANNA:] After we had told the students that we will continue our project-day on Friday, there was this girl, Anni, who is not interested in school-going normally, well, she came on to me after our information session and asked me very quietly: “how is it, am I also coming? My classes normally begin at nine, but I’ll also come at eight on Friday, won’t I?” Well you all know what this means. I mean Anni would never do anything like this normally. So, we were very surprised indeed.

There are several references to we and us in this example (“we’re all here from this school and we all know our students” turn C1; “well you all know what this means” turn C2). We argue that these ways of talking represent a strong lived ideology (LI), that is, a shared and typical way of talking about one’s work that all the members of the community recognize, and that, according to literature, has stabilizing effects. However, the example articulates an exception to this LI: the teacher, Hanna, is surprised by the demonstrable and evident engagement and self-regulation of a student who they “all know” to be typically disengaged. This demonstrates how trialing something new, even when teachers do not believe that it will work, and it is done to satisfy an external instance, creates the opportunity for surprises. Earlier research has, often incidentally, illustrated such surprises but not often systematically examined their discursive effect in the dialogue. This is what we look at next.

There are two discursive effects of this surprise talk in the data. Taking up surprises and sharing them with each other while talking about the intervention clearly has a potential to shake the lived ideology, in providing contrary evidence to the shared conceptualization of “these students” as disengaged, as illustrated above. In the following example D, the teacher Susanna notices that the learning tasks normally considered as demotivating to students, when introduced in the piloting of the new curriculum units, suddenly started to interest the students:

Data Example D (Session 5, turn of talk 185)

D1. SUSANNA: It was really astonishing for me to notice that collecting ideas from a topic for a vocabulary search, what is essential vocabulary in the topic, has been surprisingly difficult. That it wasn’t that easy. And at the same time picking out certain terms and translating those and searching those and so forth, it’s been pretty meaningful to them, I thought it would have been a simple [boring] thing, but it’s been really interesting to them, and they’ve really been thinking about it.

First, above Susanna articulates her surprise of how “difficult,” but simultaneously “meaningful,” tasks that she expected to be simple and boring, were for the students.

However, we find in our data that while this kind of noticing is potentially destabilizing of the LI, through offering evidence against it, this potential does not necessarily actualize. What is central here is that stabilization and possibility discourse co-exist while the intervention proceeds: the emergence of possibility discourse in the form of surprises and noticing does not replace stabilization discourse, it accompanies it and needs to be negotiated in relation to it. As Louie (Citation2016) also found, this is not automatically successful. We next describe the way through which the potentially de-stabilizing surprise talk ends up re-stabilizing the discourse in our data. We have identified two discursive devices that re-stabilize: we name them re-framing repair actions and dilemmatic tension.

Re-framing repair actions

One of the things that happens in the data when the teachers noticed a surprise, a potential challenge to the LI, is that the surprise is formulated as an exception to the rule. We call this characterization of the surprises as exceptions a re-framing repair action: instead of de-stabilizing the closed view of the student, the view is re-stabilized as the surprise is defined as an exception. An exception is all that remains in those cases. In example E, the teacher Susanna expresses her surprise at students’ ease and enjoyment at a task, adding that the students were also working hard:

Data example E (Session 7, turn of talk 180)

E1. SUSANNA: And they learned so quickly. For me that was, like, it really surprised me that using PowerPoint, it seemed really easy, it went really quickly. And they were really enjoying themselves. Now they [students’ work] don’t look so tidy of course, like we showed, and there are missing articles in front of words, but they were really looking hard for them, in my view they can use a dictionary well. When we’ve started from a situation where not everyone knows the alphabet.

However, despite acknowledging the surprising positive features of the experience (after all they had started from a situation where not all the secondary students knew the alphabet), this is quickly framed as an exception: She would not do this again. Not even though the students “loved it,” even “running after her in the corridors asking for more”.

E2. [Susanna:] And the students’ topics were totally random. So that when I start doing anything like this again, I want to at least limit it to either what is used in the textbook or it has to be clearly limited. Because otherwise it goes all over the place, certainly with this lot. Though they really loved doing it. That was really strange. They even ran after me in the corridors asking when will we do it again.

Noticing with surprise here provides the possibility of opening up or rupturing the stabilization discourse which, in this school, assumes that the students “can’t be bothered doing anything” (see turn A1), revealing the teachers’ LI as open to exceptions (after all, in the example the students chase the teacher down the corridors asking for more). However, the opening is immediately followed by closing down the new possibility (with repair action). The teacher here notices a difference, identifying her surprise at the students’ unexpected enthusiasm and engagement with a new activity. At the same time, the discourse expresses hesitation about opening up the classroom activity to “anything like this again,” without “clearly limiting” students’ opportunities for choice, at least with “this lot.” The lived ideology that shapes the teachers’ expectations of their students remains. Instead, we argue that, in these situations, noticing such exceptions is accompanied with re-pair actions that re-stabilize the collective status quo—reproducing the closed view of practice whereby the teachers “would not do new kind of teaching again”.

Another example of this kind or re-pair framing is in use in our earlier example of stabilization discourse (see Examples A3 and A4). In this example, the teachers acknowledged that it is not so much the innate characteristics of the students that make them passive but how they have been taught earlier and what they are used to, they, however, framed that in their school it is too late to change this (“it has to start from very young age”).

Dilemmatic tension

Another discursive strategy/device apparent in the conversations when a contradiction arises in the pedagogic talk is what Rainio (Citation2003) has called a dilemmatic tension: a contradiction in the lived ideology is articulated by the teachers; however, it is constructed as outside their influence/agency to resolve it. These examples can also be found throughout the phases of the project. In Example F, the teacher Kirsti articulates this kind of dilemmatic tension when she starts to respond to another teacher Keijo’s comment on the didactic and teacher-led teaching style:

Data Example F (Session 3, turn of talk 274)

F1. KIRSTI: Yeah, I was going to say, when Keijo (another teacher) just mentioned something like, well, that our teaching is often pretty didactic and teacher-led, but well usually, well we’ve talked about class 9E, well it is a researched fact that if there is, if I say it straight, a weak class—and Year 10sFootnote6 often are because, because they don’t—well it even demands a very teacher-led approach, at least at the beginning and for a pretty long time, so that it starts to work.

Kirsti first characterizes teacher-led highly didactic teaching as inevitable with their students. However, she then identifies a puzzle she has had “the whole time,” of whether their students’ lack of engagement might have something to do with their teacher-controlled teaching routines:

F2. [KIRSTI:] But what I actually forgot about it earlier, is that I have also been thinking about this, that whether these routines have something to do with, like that they don’t themselves start, for example, I’m teaching class 9E for the third year now and this isn’t, I’ve been like thinking about it the whole time and I’ve been trying to think of everything, how could we do things differently.

Yet despite describing the puzzle as persistent (she has “been trying to think of everything”), she defines it as outside her capacity to resolve it:

F3. [KIRSTI:] well I don’t know if I just haven’t got enough stamina, because I’ve tried a bit, a few things and then it has like not worked, because they sit there and watch and nothing happens, but that this is, in my head I have this question mark about whether it is the routines which have in some way led to them changing.

The dilemmatic in Kirsti’s turn of talk in the above example lies in the fact that she first states in a determined way that certain “weak” classes require a very teacher-led and didactic teaching style, then, however, ponders why the students (after being taught many years very didactically) stay so de-motivated and “just sit there and watch.” The dilemma is expressed and even reflected upon in this talk, so it first appears that the dilemma remains open for exploration (with possibly de-stabilizing effects). However, what happens with these turns that contain dilemmatic tension is that the teachers rhetorically express both an “insurmountable’ challenge (weak classes need didactic routines), and a need to change it (I have wondered whether it is these routines that cause this?”) within a same speech action. This means that although there is an open question, the speaker has already closed it in the earlier line: these routines cannot be changed. It is a kind of paradox that is presented here. From this, we argue, it follows that while the teacher acknowledges that perhaps their students might be more engaged after all if the teaching was less teacher-led, the teacher remains powerless to change the situation. Instead of re-stabilizing something that was earlier potentially de-stabilizing, the dilemmatic tension produces a paradox in the speech that locates the speaker outside of it. Although there is a puzzle that remains unsolved, it is a closed puzzle. We suggest that this talk is different to such discursive devices which we will argue do disrupt the lived ideology, creating a possibility of openness to the possibility for change. We will discuss next how such speech actions appear in the data and how they differ from the stabilizing or re-stabilizing speech actions presented so far.

How is possibility discourse sustained in the dialogue? (RQ3)

We then systematically examined whether there is talk in the data that does not re-stabilize the emergent possibility discourse—through framing surprising new opportunities as exceptions or defining efforts to change practice as potentially worthwhile (even with “their students”) but outside the teachers’ capability—but which would instead sustain it in the dialogue. We found there was indeed a considerable amount of teacher talk in the latter sessions in which noticing of something new, while not necessarily presenting solutions to dilemmas or challenges recognized, nonetheless sustained openness and puzzle while pondering over these challenges. We found these speech actions very significant as in light of existing literature on teacher professional dialogues this kind of talk is actually rare: it is more typical to collectively rush to quick (often closed) solutions than to “slow down” and sustain the puzzle (cf. Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018). We term this kind of talk reflexive noticing, and in this Section we identify different discursive features that were present in these speech actions.

Taking the lived ideology under scrutiny by “reflexive noticing”

In these instances teachers’ talk started to challenge the closed view of students by taking under scrutiny or discursively becoming conscious of, the assumptions behind the students’ as well as the teachers’ behavior (their lived ideologies, see Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015). This is why we have named this kind of talk reflexive noticing.

We demonstrate this through an example of a lengthy conversation between three teachers in which they reflect on a pilot teaching unit that they implemented with special education classes. In our earlier analysis (Rainio & Hofmann, Citation2015) we showed how the teachers’ talk of their students changed during the intervention toward recognizing the students as complex embodied beings with different feelings, needs and ways of orientation. This is an example of such a talk: the teachers here notice that the students themselves learned to notice, as a part of the pilot unit teaching, that their learning does not necessarily relate to their personal abilities but also to how the learning situations are organized and supported (see e.g., Susanna turn G3):

Data example G (Session 7, turns of talk 35–47)

G1. SUSANNA: With the students in the special educational needs support group, they themselves noticed it when they were doing it [the studying style test]. Many of them were going to abandon it without completing it, it was so long. It was really challenging for them, we had to really do it hand in hand with them and they may not even have understood all of it. But the feedback they gave afterward was that it made them realize that “learning is not necessarily difficult for me because I’m dumb but that there may be disturbing conditions around me that just don’t suit me.”

G2. LEILA: Yeah.

G3. SUSANNA: And that I can actually do something about those things so that I can learn better. That’s what I noticed. For example, eating and things like that, the need to move and such. They are pretty natural. It doesn’t mean that—something is wrong.

Susanna describes how the activity is very challenging for the group of students, however, she then elaborates how doing it had made the students realize that their learning struggles might not be related to simply innate ability, but to conditions for learning around them. This illustrates an instance of double noticing, where the teacher notices the students noticing something new about their learning. What is relevant in this dialogue for our current analysis is that the teachers in this example recognize the challenges that their students have (e.g., turns G1, G7). However, instead of seeing those as an obstacle, there is a new openness in their talk, even subtle questioning of their own views. The dialogue continues with a response from Leila that “we are also used to thinking that this is how things go”—referring to the teachers themselves with the “we”, and continuing that “but that they don’t for everyone.” Leila and Susanna both share this new observation:

G4. LEILA:[…] we are also used to thinking that this is how things go.

G5. SUSANNA: Yes.

G6. LEILA: But that they don’t for everyone there.

G7. SUSANNA: That’s it, it doesn’t go easily for everyone.

G8. LEILA: That's what occurred to me here too.

G9. SUSANNA: Yeah, it was really important that they noticed that it isn’t at all abnormal.

The teachers here seem to become “discursively conscious” of their commonly held lived ideology (see ). The teacher Karen then joins the discussion by commenting that students may have very different needs to learn and concentrate:

G10. KAREN: And for example the fact that someone may need background noise, sounds, voices, music. That if you sit with your headphones on at home, it’s not necessarily a bad thing in some situations.

G11. ANOTHER TEACHER: Exactly.

G12. KAREN: Of course then if you need to listen to instructions or something.

G13. SUSANNA: And then exactly that, that for example, in tests, I have allowed in assessments, some of them have to have something to eat with them, chewing gum or something, a drink, something, they need it to concentrate that they are chewing something for example. That was really really good. Some of them took some, who felt the need, some didn’t. They were really nicely during the exam.

The above dialogue is an example of talk which, by framing the students’ problems as understandable and something that the teacher can help with, and that the students themselves can influence on has a destabilizing effect: the LI that in the early phases of the project-framed students and their abilities and personalities as outside teachers’ influence, and as the main obstacle for change or development of classroom practices, is now in itself a focus of their work.

Noticing the positive in the students and opening a future orientation

One aspect in the talk that destabilizes the LI is that the students are still framed as the same ones, acknowledging their struggles, but instead of only focusing on the negatives, the teachers also highlight, “see,” some positives, and ascribe some value to those. Also, in the following dialogue the teacher noticing is interestingly coupled with student noticing (different teachers and different pilot unit than in Example G above):

Data example H (Session 8, turns of talk 288–290)