Abstract

Background

Studies of group creativity have focused on adults acting in professional settings, with less attention paid to how adolescents collaborate in groups in creative activities. Building on sociocultural perspectives on imagination as a complex capacity in adolescence, this study examines students’ creative-imagining processes and the role of peer influence in group collaboration.

Methods

The setting of the study is a two-day museum-led workshop on the topic of architecture, which was produced for a national touring program for middle schools. Video data of students’ collaborative interactions comprise the primary data for the analysis.

Findings

The study identifies material, institutional and relational aspects of group creativity in adolescence. A key finding is how creative influence is socially negotiated when merit-based knowledge and authority in an art domain are not valued. The study also finds that students’ interactions in creative activity may be viewed as evidence of learning processes even without consensus in the group.

Contributions

This research contributes new understandings of adolescents’ creative-imagining processes and creative influence in arts-based learning activities in middle school. Principles for arts-based learning designs are presented:the appropriateness of materials; designing for knowledge dependency in open-ended tasks; and facilitating productive forms of creative influence.

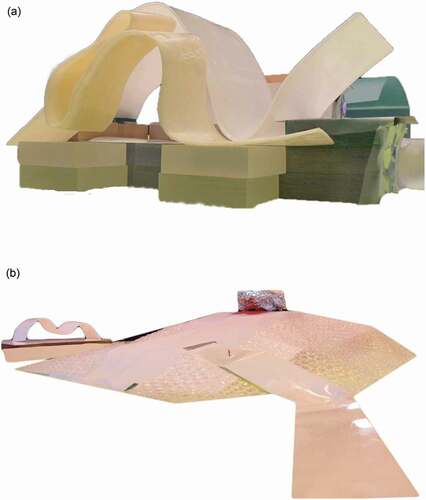

A vignette from creative group collaboration

It was the end of a two-day architecture workshop, and the four students were visibly discouraged as they prepared to present their group’s design for a new cultural center. To the right below (), we see the model presented by group members Tom, Irene, Evan and Jean (12–13 years old). It includes a main low building with a glass bridge in the foreground and a separate skate hall building at the back, which Evan alone designed. To the left () is a model presented by a different group that more closely resembles Evan’s vision for his group’s design. A lack of agreement about the form of their building had created a stalemate in the group’s creative collaboration, which had previously been very productive. The students’ frustration was clearly voiced to the museum education curator, who was leading the workshop, when she stopped by their table while they were working.

((addressing curator)) How do they ((an international architecture firm)) manage to work like this here?

It’s fun, isn’t it?

Yeah, it’s really fun, but

Yeah, but it is completely, frustrating

Hmm, why is that then? What is it that’s frustrating? You can’t agree

No

They only want like a drop over the roof while I want sled hills.

We want a super contrast

And he ((points at Evan)) just wants sled hills over the whole roof

Is it possible to make both a sled hill, from one side of the roof, and a teardrop shape with contrast?

Yes, but he doesn’t want a drop shape

Yeah, but she doesn’t want a sled hill

((addressing Irene)) Why not?

I don’t know really ((smiles))

((addressing Evan)) Can you explain why it’s life or death for you to have a sled hill?

Yeah, it was there earlier and it gives a little history and contrast

In the excerpt above, Tom conveys the exasperation experienced by the group when asking the museum educator how architects manage to “work like this.” The students are specific about the point of contention—the main design concept for the building’s form (“teardrop” versus “sledding hill”)—as well as about which side of the argument they are on. However, when the museum educator asks Irene “why” she objects to Evan’s idea, she is unable to provide an explanation. When asking Evan the same question, he responds, as we will show below, using the same arguments for the building’s form that he had been making for ninety minutes, since the group’s work on the modeling task had begun. Yet, regardless of Evan’s merit-based arguments and his assigned role in the group as the expert in “inspiration” for the design of the building, Evan had been unable to influence the group’s creative outcome.

The aim of this article is to better understand creative-imagining processes, and particularly creative influence, in young people’s collaborations on arts-based learning activities. We define creative influence as the extent to which an individual participant is able to argue and persuade others to support—or not support—a proposed idea or solution in an arts-based collaborative learning activity. We use the term creative-imagining processes to highlight a focus on how imagination becomes mediated in groups collaborating on arts-based learning activities. This unit of analysis is thus interactions between participants and how they connect and make use of symbolic and material resources, which broadly include all of the instructional materials available in the learning activity and setting. In arts-based learning activities, learning processes are studied as part of the creative actions that are performed. A sociocultural perspective is the theoretical stance we apply in this study, drawing on Vygotsky’s (Citation2004a, Citation2004b) studies of creativity in adolescence as intertwined with age-sensitive developments in human imagination, conceptual thinking, and personal capacities. Two research questions guide our investigation. First; how are adolescents’ creative-imagining processes fostered or hindered in collaborative learning activities? Second; in which ways do features of collaborative learning activities mediate creative influence in adolescent groups?

Analytic stance and key concepts

From a sociocultural perspective, adolescent creativity must be understood as intertwined with developmental changes in imagination, conceptual thinking, and personality (Vygotsky, Citation2004a, Citation2004b). In adolescence, the workings of imagination develop from being a function of play activity in childhood to transforming and maturing into the diverse and subtle imagination identified in adult behaviors, traits, and experiences (Gajdamaschko, Citation2005; Glăveanu, Citation2010; Sawyer, Citation2012; Vygotsky, Citation2004a). More critical attitudes develop, as subjective qualities in products of imagination are increasingly judged in relation to external cultural and professional quality standards of creativity. Imagination in this transitional age also becomes intertwined with the development of thinking in concepts (Moran & John-Steiner, Citation2003) and with the formation of personal capacities. Vygotsky (Citation2004a) referred to findings from a study by Pashkovskaya to explain:

It is characteristic that in the answers, the concept and the content reflected in it are not given by a child, as assimilated from outside, something completely objective; it is merged with complex internal factors of the personality, and at this time it is difficult to determine where the objective statement ends and where the manifestation of personal interest, conviction, and direction of behavior begins. (pp. 439-440)

We draw on this understanding of creativity, imagination and personality development as intertwined in our theoretical approach to studying group creativity in adolescence and in particular, the role that social dynamics and influence may play.

Much attention in the research has focused on adult group creativity in professional settings (e.g., designers, artists, musicians). Creativity in design and architecture professions, for example, has been studied from different perspectives, at both individual and group levels. Neuropsychology and neuroimaging studies of design processes (Goel & Grafman, Citation2000; Green, Citation2016), including among adolescents (Kleibeuker et al., Citation2013), have found correlations between brain functions and different kinds of tasks in problem-solving (e.g., ill-structured versus well-structured tasks; Vartanian, Citation2017). Studies in neuropsychology have shown how the brain “appears to enable the maintenance of indeterminate representations during problem-solving” in tasks that are poorly defined, as is often the case with tasks that invite creativity (Vartanian, Citation2017, p. 117). Moreover, differences have been identified between early phases of professionals’ design processes, which entail exploring design alternatives in a widened, abstract problem space without committing to generated ideas, and later phases when ideas are selected and become more detailed and concrete in a deepening of the problem space (Goel & Grafman, Citation2000). During design phases in architecture, for example, there is interplay in functions that “process different types of symbols and related mental representations” (Vartanian, Citation2017, p. 117). In addition to such skills that are relevant to design expertise and advanced disciplinary knowledge, professional architects have mastered skills that enable them to influence creative judgments in a group by making persuasive arguments that reference valid knowledge (Murphy et al., Citation2012).

However, we cannot assume that knowledge and design skills mediate creative influence in the same manner for groups of young people as they do for professionals. First, collaboration on design problems and arts-based tasks arguably pose a complex disciplinary challenge for both students and teachers in that, despite domain knowledge and esthetic criteria, solutions are more open-ended than mathematics and other subjects with correct or verifiable solutions (Sawyer & DeZutter, Citation2009); multiple perspectives and solutions may be argued using valid knowledge. Second, even in domains with clear criteria for what counts as valid knowledge, it cannot be taken for granted that students will have a shared understanding of the content and key concepts involved (Van de Sande & Greeno, Citation2012). Third, studies have shown that social dynamics can play an important role when young students struggle with collaborative learning and problem-solving in mathematics and other subjects (Barron, Citation2003; Krange & Ludvigsen, Citation2008). In her classic study of “when smart groups fail” solving math problems, Barron (Citation2003) found that both students’ understanding of the problem content and the relational context, that is, the quality of social interactions and responses among participants, were important to whether members accepted what were in fact valid arguments and correct responses by others. Against the background of these studies, we explore how social dynamics and other dimensions of collaborative work on arts-based tasks may give some students undue creative influence, particularly in the transitional age of adolescence, when imagination becomes intertwined with thinking with more formal concepts as well as the formation of personality (Vygotsky, Citation2004b). At the same time, from a pedagogical perspective, we acknowledge that tensions, breakdowns, and problematization in group collaboration on learning tasks can also become events and resources for learning and creativity (Krange & Ludvigsen, Citation2008).

Architecture workshop as research context

The context for this research is a two-day workshop that was produced by a Norwegian architecture museum for a national touring arts and culture program for schools. The architecture workshop was initially proposed by a senior curator, as a museum production that would be offered in a national touring program designed to ensure that all school pupils in Norway experience professional art and culture of all kinds (Norwegian Ministry of Culture and Church Affairs, Citation2007,Citation2008). The museum’s aim for the workshop was to familiarize students (grades 8–9) with the work of Snøhetta, a prominent Norwegian architectural firm, and to provide creativity training in materials and design tasks specific to the domain of architecture. The architecture museum was also a partner at the time in a larger research project at the University of Oslo, in which all three authors participated. The curator contacted the project leader (first author) to propose collaboration on the workshop production, and it was agreed that this joint activity was well-aligned with the larger research project’s overall aims. The pedagogical content and design of the workshop was iteratively developed using design-based research methods over a twelve-month period (Barab & Squire, Citation2004; McKenney & Reeves, Citation2018; Pierroux et al., Citation2021; Stuedahl, Citation2019), involving the participation of museum curators and educators, learning researchers (first and second authors), students, schoolteachers, university programmers, and senior partners and staff from Snøhetta. The domain content also aimed to align with Norwegian curriculum, which requires secondary school students to have knowledge of the influence of environment, culture, and social functions on architecture through analyses of form, materials, expression, and symbolism (Steier & Pierroux, Citation2011). A full-scale pilot study was a milestone in the project.

This study is based on iterative and detailed analyses of data collected from the workshop development process and from the full piloting of the two-day workshop in a school. Below we present workshop features in greater detail, describing three dimensions of the pedagogical context identified in our analysis as most relevant to the study of adolescents collaborating in creative activity learning settings: institutional, material and relational dimensions. Then, using a narrative analytic approach (Derry et al., Citation2010; Engle et al., Citation2014), we select and analyze sequences of one group’s interactions during two different workshop tasks to illustrate how these dimensions are made relevant in their collaboration. Combining the ethnographic approach of systematically refining a narrative description with a detailed analysis of transcribed excerpts increases the credibility and trustworthiness of the study, capturing temporal aspects of activities and sequences of interaction as resources move in and out of relevance. In this way, the overall analytical approach follows Vygotsky’s argument for studying processes of imagination in learning and human development (Moran & John-Steiner, Citation2003).

Institutional dimensions: Architecture and art education in museums and schools

The institutional characteristics of a learning activity include the rules, structures, and expectations built into the context, in this case, with elements from school, museum-led workshops, and professional architectural practices. The educational design of the workshop drew on professional practices at a prominent architecture firm, which emphasized knowledge sharing among all team members of a project. During interviews, observations, and meetings in the participatory design of the workshop activities, the architect partners explained that during a design project “it’s very important that everyone has the same position, that no one is above the other, and that everyone is allowed to contribute.” Further, it is “important that everyone knows as much as everyone else about the project.” Thus, the ideals for group collaboration were based on mutual respect for different types of expertise; symmetrical and asymmetrical forms of interaction; and participants having the same position in knowledge sharing. However, empirically, there are differences in terms of whose voices influence and inspire the creative process in professional practice. This was apparent, for example, in video recordings of a small group of the firm’s partners and lead designers visiting the sites of new projects, where natural forms and local conditions triggered the architects’ imagination and inspiration. Their initial ideas subsequently established the main design concepts for buildings and their relations to surroundings. This is common in architectural practice; the design direction of important projects is established, at least in part, by early sketches and models by lead designers and senior partners. To model the firm’s practices of knowledge sharing among colleagues and consultants with different types of expertise, a jigsaw approach (Aronson et al., Citation1978) discussed in greater detail below, gave structure to the pedagogical design of content, activities, resources, and collaborative group work.

Touring workshops organized by museums may be integrated in classroom practice in different ways, or they may not be integrated at all, treated instead as free time from school. It is customary in the touring arts program for a museum educator to travel with the workshop and collaborate with classroom teachers in the different schools. The learning aims for this workshop emphasized “learning in” versus “learning through” the arts (Fleming, Citation2011; Sawyer, Citation2012), specifically, learning in architecture and design. This emphasis is in keeping with the museum partners’ interests in promoting domain-specific creativity training, a strength of museums as informal learning environments (Pierroux et al., Citationin press). In contrast, and historically a departure from European traditions, there has been a trend in recent decades to validate art education in schools using arguments of cognitive benefits and skills that may transfer to other domains—a learning through the arts rationale. In the most recent Norwegian curriculum there has been a shift once again, with recommendations for the development of students’ creativity in school subjects emphasizing a combination of domain-specific knowledge (learning in the arts) and domain-general learning skills (learning through the arts), the latter of which include collaboration, problem-solving and communication skills (Ludvigsen et al., Citation2015).

In sociocultural approaches, creativity is often defined in relationship to a domain (field) and a cultural context, a reciprocal interaction in which “creativity is not only influenced by culture, it in itself influences how a culture evolves and receives creative products and ideas” (Dishke Hondzel & Sørebø Gulliksen, Citation2015, p. 3). We propose that studies of adolescent creativity similarly need to take into account institutional dimensions of the cultural context, including how collaboration in creativity training is organized, the professional and domain-specific knowledge sharing practices on which the design of the tasks and activities are based, the “ground rules” for social interaction and dialogue, and the object of activity.

Material dimensions: Architecture models

Creativity, Vygotsky explains, is present “whenever a person imagines, combines, alters, and creates something new […]” (Vygotsky, Citation2004b, p. 10), but is also predicated on the historical development of products of imagination and knowledge. In architecture, models are a specific type of historically-developed tool and cultural product, and they serve multiple purposes in different phases of imagining and design activities (Pierroux et al., Citation2019). It is in this sense that modeling activities are key to the learning aims of the workshop activity, as creativity training in materials and cultural forms that are specific to the domain of architecture. The professional knowledge involved in model-making served as a resource for process and product in the modeling tasks, constructing diverse problem spaces for the young people to imagine solutions using different kinds of materials. The workshop materials were purposely similar to those found in professional studios, which will often enhance the “creative density” of a workspace to develop design concepts using a random assortment of artifacts, materials, scraps and papers (Binder et al., Citation2011).

Hutchins (Citation2005) proposed the notion of imaginary material anchors to explain how different kinds of materials become blended with concepts, that is, how imagination is mediated by cultural forms during ongoing activity. Hutchins understood the role of imaginary material anchors as “imagining the manipulation of a physical structure” and, through familiarity, “to imagine the material structure when it is not present in the environment” (p. 1575). In model-making, imagination may thus be studied as an “organizational property of the ongoing activity” (Nishizaka, Citation2003, p. 178), which includes seeing and manipulating the “representational possibilities” of the material environment (Steier et al., Citation2019). Representational possibilities may be triggered by different modalities or sensory features of resources (e.g., how materials sound, feel, smell, taste and look), whereby an “imagination space” is created through abstracted semiotic means. In this imagination space, symbolic and symbiotic relationships are explored in an open-ended approach, expanding both the possibilities of the material and the idea (Pierroux & Rudi, Citation2020; Steier et al., Citation2019; Zittoun & Gillespie, Citation2016).

Further, in architectural design, imagination also entails “the ability to creatively make talk, gestures, and material objects stand in for or signify things that are not immediately perceived, and in the processes treat them as if they were” (Murphy, Citation2004, p. 269). Accordingly, both material and interactional resources may become blended with concepts and collaborative processes, e.g., through talk, bodily orientation, modeling materials, dynamic gesturing and sketching (Goodwin, Citation2000, Citation2013; Steier et al., Citation2019). We adopt these concepts of imaginary material anchors and the mediational aspects of social interaction to analyze the group’s creative-imagining processes: specifically, to gain insight into how participants imagine relationships among material elements as relationships among conceptual elements in the respective modeling tasks.

Relational dimension: Merit-based arguments and creative influence

Creative-imagining processes in a group are mediated by the material and institutional dimensions of an activity and its setting. Moreover, in a collaborative learning activity, the ways in which ideas and solutions are proposed, argued, and taken up interactionally by participants will vary. In school settings, “teachers cannot dictate the kind of talk that develops among peers” (Schwarz, Citation2009, p. 99). We must recognize that talk emerges from the students’ participation, as they try out formulations to develop their understanding in a subject. Although young people around age 11 can “produce both justifications explicitly defending their point of view, and statements referring to their adversary’s point of view” (Muller Mirza, Perret-Lermont, Tartas, & Iannaccone, Citation2009, p. 72), we must also recognize that argumentation is “simultaneously cognitive and social” (p. 85) and an important part of socialization in childhood. As Andriessen and Schwarz (Citation2009) point out, the challenge of pedagogically designing for “productive argumentation” is thus difficult, complex, and “age-sensitive.” Opposition and confrontation may not be considered acceptable in argumentation and rouse emotion, introducing personal and affective engagement into group work that may or may not be productive for learning. Therefore, Schwarz (Citation2009) identifies a need for “fine-grained studies that scrutinize relations between social and cognitive aspects in argumentative activities” (p. 99). Particularly needed, we propose, are studies of emergent argumentation skills that are sensitive to young people’s collaborative learning in arts-based tasks.

To analyze relational dimensions of argumentative activities in creative group work, we draw on Engle et al.’s (Citation2014) “model of influence” in persuasive discussions. According to their model, each individual participant’s level of influence on the group discussion changes over time in relation to four aspects. First, the “negotiated merit of each participant’s contributions” includes the locally determined perceptions of what arguments are deemed influential. Second, the “degree of authority,” which is also in flux and negotiated by group participants, includes how seriously arguments are treated based on their attribution to a particular participant. Third, “access to the conversational floor” includes the participants’ control over and access to contributions to the group discussion. Fourth, the “degree of spatial privilege” includes the participants’ control over orientation toward each other and shared resources. These four aspects contribute to the influence a participant may have in a group, and are determined dynamically and interactionally during the collaborative activity. We expand on this model to develop the concept of creative influence in adolescent group collaboration. Specifically, we consider these aspects in the analysis of creative influence and how it is socially negotiated in the group.

Methodological approach

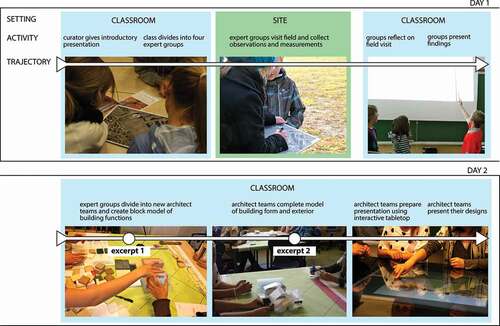

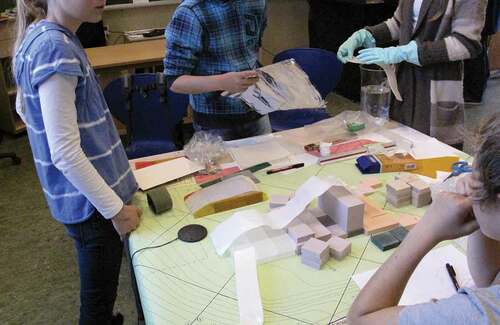

The object of activity for students in the workshop was to plan a new cultural center for their neighborhood. As mentioned above, a jigsaw approach (Aronson et al., Citation1978), was used to structure knowledge sharing and collaboration in the learning activities. While the focus on “making” and on gathering knowledge outside of the classroom differs from other applications of jigsaw approaches in school settings (Hernández-Leo et al., Citation2011), the approach was useful in modeling collaboration in architectural practices, e.g., architects designing with input from engineers, developers, and consultants. On the first day of the workshop, the students were organized in four expert groups that collected knowledge on the following domain-specific content: use, environment, place and inspiration. These learning activities took place during a visit to the site, where each group was provided with specific tools, tasks, and materials (). On the second day, the students were reconfigured in four new architect teams for creative collaborative work in the classroom, with knowledge from each expert group represented by at least one member. The first collaborative task involved the use of blocks to produce a scaled model of the building’s key functions and site orientation. This block model served as the basis for the second task, which entailed modeling the exterior of the building using a selection of materials. When each round of model-making was completed, the students took pictures of the model and uploaded them to an interactive tabletop that was used to make presentations of their designs for the cultural center (Smørdal et al., Citation2014). In this study, we focus on the two modeling tasks by the architect teams (). The analysis of the context and students’ interactions with the resources will provide insight into how different aspects of the learning processes and creative influence unfold.

Participants, data collection and corpus

The researchers presented information about the architecture workshop and the research project to a school principal, 9th grade teachers, and students in a local public school. Based on their interest in the workshop topic, a class of 20 students and one teacher were recruited as participants in the pilot study, and parental consent was secured for data collection. The teacher was also a participant in tweaking aspects of the workshop design. Data was collected during the pilot study using ethnographic methods in educational design research (McKenney & Reeves, Citation2018; Rubin, Citation2019). One week following the pilot study, four group interviews with the student “architect teams” and with the class teacher, were audio-recorded. Data types include video recordings of all workshop activities, artifacts produced by the students (i.e. photos, notes, digital presentations), photos documenting the students’ activities, and audio recordings of interviews. Video recordings were used because they are particularly useful for close analysis of social interactions in media-rich settings (Derry et al., Citation2010; Jordan & Henderson, Citation1995), in this case involving multiple tasks and settings, and a multitude of physical and digital materials and resources. In the classroom, two video cameras were used to capture the students’ interactions while working in different group arrangements on day one and day two (see Steier & Pierroux, Citation2011). Microphones were placed on each group table in the classroom setting (). The corpus comprises the digital and analogue materials produced by the students, 35 hours of video recordings from “field” and “classroom” settings, three hours of interview audio recordings, field notes, and approximately 150 still images of group activities during the two days. Student and parental consent was secured for recording and photographing the students, who are anonymized in the figures to comply with regulations protecting privacy and the use of personal data.

Analytical techniques

All groups successfully completed all of the tasks in the workshop and presented their findings and designs to the whole class at the end of each day. In the initial phase of analysis, we approached the data corpus with an interest in the creative trajectory of groups of students as well as in the ways the two different modeling activities, involving quite different kinds of materials and tasks, mediated the groups’ learning processes. Based on observations and repeated viewings of video material from the four groups we recorded, we found a general pattern of productive interactions in all of the groups during the first modeling task, which used colored blocks to indicate the volumes and functions of their cultural center. We also found a contrasting general pattern of tensions in many of the groups during the subsequent modeling task, which focused on the exterior form of the building. However, it was unclear how these tensions in group collaboration, which often involved argumentation, were related to specific features of the activity. Understanding these tensions and their significance for groups’ productive and creative work required attending to the micro-interactional sequences of activity among the participants as they worked with different materials as well as to the broader collaborative and creative trajectories of the participants in the context of the two-day workshop. Therefore, in the next phase of analysis, we selected and transcribed video recordings from the trajectory of learning activities that were related to one group’s collaboration on the different modeling tasks (approximately eight hours of video). Detailed analyses of the transcripts, data corpus (i.e. video data, field notes, photographs, interview recordings), and research literature were conducted, in an iterative process of progressive theory refinement.

Below, we use a narrative analytic approach (Derry et al., Citation2010; Engle et al., Citation2014), selecting interactional “hotspots” (Jordan & Henderson, Citation1995) from the longer trajectory of learning activities to analyze how key dimensions of the pedagogical context are made relevant in creative-imaginative processes and creative influence. This approach integrates the analysis of significant excerpts of a group’s interactions to present findings in the form of rich contextual descriptions. The excerpts were transcribed using conventions adapted from conversation analysis (Jefferson, Citation1984) to analytically “zoom in” on participants’ talk, gesture, and gaze (Derry et al., Citation2010; Roth, Citation2001), in this case, to examine how learning, creative-imagining processes and creative influence unfold and develop in a group. As a temporal mechanism for creativity, a group may be conceptualized in terms of how multiple dimensions of a problem become worked out: work with a product is not symmetrically shared in a group. As a temporal social “unit,” a group gives access to observing and analyzing how individual participants contribute and how the group interacts through the different processes of creating and designing a product. From a sociocultural conceptual stance, this analytical approach is in keeping with Vygotsky’s (Citation2004b) methodological aims for studies of learning and creativity “in the making” (Moran & John-Steiner, Citation2003, p. 7), that is, making visible the interconnectedness between unfolding experience, cognitive functions, and activated resources in the environment.

Analysis and findings

Day 1: Working in expert groups

The workshop began on the morning of the first day with a presentation by the education curator about architecture and the architecture firm’s particular design philosophy and knowledge-sharing approach. The presentation included images and short videos of the architect partners in action on the sites of future buildings: imagining, drawing and discussing ideas by drawing inspiration from the physical surroundings and local context. Several well-known buildings by the firm were shown, including the Oslo Opera House.

After the introductory presentation, the curator introduced the overarching task to “design a new cultural center for your neighborhood.” She evenly divided the 20 students into four expert groups, pre-assigned by the classroom teacher: Place, Environment, Use, and Inspiration. The class then walked to a site that had been pre-selected for the cultural center, an open field near their school, where groups worked on their respective learning activities using the provided materials (e.g., worksheets, maps, measuring tapes, cameras). Evan and the other Inspiration group members were tasked with observing and photographing forms and features in the landscape around the site and to come up with ideas inspired by local history, nature, and materials (see ). To provide some historical background, the museum educator had included on the worksheet a brief text written by a local historian about how a large hill nearby had earlier been used for sledding and skiing. The group learned that children would sled down to the site from the neighborhood above. Through onsite discussion facilitated by the curator, the group developed the concept of contrast to describe the relationship between the sloping hills and the more rectangular buildings they observed (Steier & Pierroux, Citation2011). Back in the classroom, each group shared its findings with the whole class in presentations at the end of the day. The Inspiration group showed some of their many sketches of sledding hill forms and explained the concept of contrast as a type of design inspiration. On the second day, Evan became part of an architect team that included Irene from the Environment group, Jean from the Use group, and Tom from the Place group.

Day 2: Working in architect teams

The goal of each architect team was to create and present two architectural models of a proposed design. The learning activity aimed to support the students in integrating different ideas and expert knowledge during collaborative group work. Following the architect firm’s principles of knowledge sharing, the museum educator and teacher both encouraged the groups to listen, discuss, problematize, and agree with each other on the building design.

Modeling with blocks

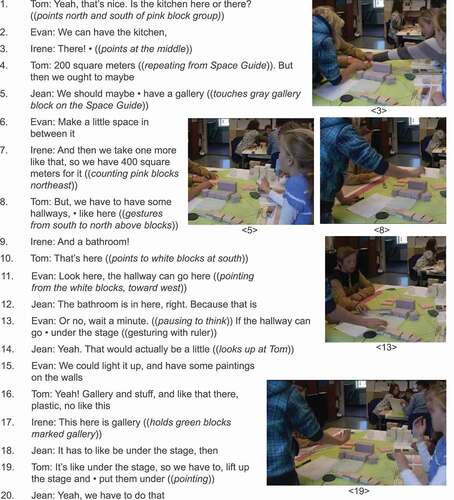

The students began the first modeling activity with scaled blocks of different colors that corresponded with different kinds of spaces and functions in a cultural center, both essential and optional. Working on top of a topographic map of the site (1:200 scale), the groups were instructed to arrange the scaled blocks to express and visualize the volumes and orientations of the different spaces they wanted to include (). They used a Space Guide (), which displayed the recommended square footage and number of blocks that could be used for different types of spaces and functions. Based on knowledge developed the previous day, the students had to make decisions about which functions they wanted to include and where these functions should be in the building. The model was made by selecting and arranging the colored blocks on the map () to indicate the location of the cultural center’s main “use” features (e.g., entrance, stage, restaurant, practice rooms), with the orientation and footprint of the building based on considerations of “place” and “environment” (e.g., trees, traffic, nearby housing, sun movements across the site).

During the first 30 minutes of the hourlong activity, the team of Jean, Tom, Irene, and Evan reached general agreement about several key elements of their building, such as the location of the main entrance, the movement of the sun, and which building features were important to prioritize for direct sunlight. Their talk was productive, each student placing and moving blocks to accommodate their own ideas without protest from others. About halfway into the hourlong task, Tom asked a question about the location of the kitchen (, left to right: Tom, Evan, Irene, Jean).

We now turn to a more detailed analysis of the students’ interaction and how material resources become activated in this excerpt. In the first 3 turns of this excerpt, Tom, Evan, and Irene direct their joint attention to the kitchen location, with Evan and Irene considering options in response to Tom’s question. Then, Jean proposes the possibility of including a gallery (turn 5) while she taps the Space Guide, which has a specific block color for this function. Her suggestion of a gallery is not picked up at this time by the other students. Evan then raises the question of how to manage space “between” functions (turn 7), which suggests a problem he may have conceptualizing the level of detail represented at this scale of a model. Tom picks up on Evan’s point in turn 8, stating that hallways are needed to link different spaces together, gesturing over their model as he stands. This suggestion prompts a rich sequence of mutual elaboration, through turn 20, as the practical constraint of linking the different kinds of spaces together through hallways develops into an idea for a multifunctional gallery. After pausing to think about the hallway problem, Evan suggests that the hallway could go under the stage (turn 13). While he makes this proposal, he uses the ruler in his hand to trace this possible pathway, publicly “imagining” the connection between the different spaces on the model. While both gaze up at Tom from their seats, Jean responds positively and Evan elaborates that this hallway could include lighting and paintings. This turn, from the functional properties of the hallway as a physical connection to the esthetic properties of the hallway with lighting and paintings, emerges as Evan imagines an experience of walking through a darkened underground hallway, visualizes a need, and creatively solves the problem with specialized lighting. Tom responds very enthusiastically (turn 16) and then extends the proposal by noting that the hallway could include a gallery, which was previously mentioned by Jean (turn 5). Irene, who has been quiet for several turns, immediately counts the stack of green “gallery” blocks and moves them toward the middle of the table (turn 17).

This excerpt shows an imagination space through which a new idea emerges and progresses: the young people shift from dealing with the concrete problem of how space functions represented by the blocks will be connected (“we have to have some hallways” turn 8); to imagining a hallway under the stage; to further imagining the hallway with special lighting and paintings; to arriving at the shared idea of a hybrid hallway/gallery space. From a learning perspective, the analysis shows that the students—through talk, gaze, gesture and materials—are able to imagine as a group a creative solution to a domain-specific problem, drawing on participants’ relevant knowledge (i.e. place, use, environment, inspiration). Elaboration of the idea continues for several minutes when Irene, who had been looking at the block guide for kitchen space requirements, appears surprised when the other three start to disassemble the existing model to make the hallway “underneath.” This prompts the others to re-explain the concept of a hallway, imagined under the blocks already in place for the stage. In an attempt to express the idea more clearly, Tom extends the imagination space by sketching a diagram of the plan on a sheet of paper while the others observe. At this point, the group calls over the museum educator to tell her their idea, which she enthusiastically approves.

Modeling with Materials

The model made of blocks is now the basis for the next modeling activity. The teachers have given each table modeling materials (e.g., papers, foils, and plastics) and instructed the groups to model the exterior form of the building “on top of” and “according to” the building forms they have made using the blocks. Collaboration on the new modeling task, a continuation of the main activity, is the focus of analysis in the next excerpt. The students understand that they have to give form to the building using materials at hand, some of which are rationed, and there have been vague references in the group about the merits of pursuing Evan’s idea of the “sledding hill” form that had been presented to the class the day before by the Inspiration group. It has been mentioned, for example, that other architect teams are also going to develop this idea, which makes it seem less original, and Tom has mentioned that he has a different idea involving a “teardrop” shape that he would like to propose. Evan has nonetheless chosen to ignore the possibility that his group will not want to use the sledding hill as design inspiration for their building, showing no interest in hearing Tom’s idea. After 10 minutes of long silences and not really knowing how to proceed, the group joins the rest of the class for a 15-minute outdoor recess. The unspoken tension between the different design ideas is clearly challenging collaboration in the group.

When they return to their tables after recess, the museum educator encourages the class to experiment with the different materials to generate ideas in making the model, demonstrating how architects work by crumpling paper and using it as a form. She explains the task once again: “What you are going to begin with now, is to model the building itself. Now you are going to, on top of the building you have decided on, make the form.” Evan and Irene are seated at the table across from each other while Tom and Jean stand silently, moving restlessly and fiddling with the materials as they collectively watch him. Tom intermittently sits next to Evan and sketches on a sheet of paper. There are undercurrents of resistance and competing interests that have not been verbalized; the building design has clearly become “the elephant in the room.” Evan largely ignores verbal overtures by the other three group members to discuss how they will proceed, instead working purposefully to make the smaller skate hall building (). Both teachers have stopped by the table to inquire about their model and progress, but the students only tell the teachers they are changing their ideas and do not ask for help.

In the beginning of this excerpt, Evan is working on the skate hall, a small rectangular form, as the others look on silently. He proceeds “as if” the others are collaborating, and makes several attempts to be inclusive, as in turn 1, when he asks Tom to mark a piece of cardboard he is measuring. Tom ignores this request and after a long pause, poses a question in a critical tone to no one in particular about how a sledding hill could actually be made (turn 2). This comment is quickly echoed by Irene and followed up by Jean, who together with Tom voice the possibility for the first time of “dropping” the sled hill idea because it “won’t work” (turns 4–7). Evan immediately reacts, calmly but firmly, to their objections, assuring them that it will work and that he has an idea. Tom begins to pitch his alternative idea by drawing a teardrop shape on paper, while Evan likewise takes a sheet of paper and begins to draw. Jean and Irene, ignoring Evan, look at Tom’s drawing, mention a skating rink on top as a possibility, tap on the paper, and say that yes, they can “agree” on this idea (turns 9–13). Irene is also explicit that the sled hill is not an option (turn 14). Evan once again ignores Tom’s proposal and shows his drawing to argue his idea. However, the drawing does not convincingly demonstrate how the practical problem—“how it works”—will be solved.

The others continue to protest along these lines, pointing out flaws in the physics of the design for sledding on the roof that Evan is not able to effectively refute (turns 15–28). Instead, Evan refers to his creative work in the Inspiration expert group the day before, protesting that even though the others had seen the presentation they did not understand—but he would show them (turns 17–22). The presentation of dramatic, curved rooftop shapes the day before had made a positive impression on many of the students and, as shown above (), other groups were indeed developing this idea in their models. The disagreement came to a head when Tom makes yet another pitch for his teardrop form that is ignored by Evan, who continues to argue the functionality of the shapes as a sled hill as he draws. Using Evan’s drawing as reference, Tom emphatically dismisses both the practical function and the esthetic function of the curved shapes, exclaiming that it will be “ugly.”

Throughout this modeling activity, neither Evan nor Tom, Jean and Irene give up on their respective ideas. The group halfheartedly attempts to use the materials to explore how a sledding hill might be made (), but each experiment with materials is rejected and contested in a pattern of unproductive attempts. The final product is hastily resolved in the final ten minutes of a two-hour modeling activity, with Evan modeling a skating hall roof with sledding forms as a separate building and the remaining team members modeling the main building with a teardrop roof form made of bubble-wrap ().

Discussion of findings

The character of the students’ collaboration differed greatly in the two tasks, from productive interactions that fostered imagination and group creativity to interactions distinguished by disagreement, unproductive argumentation and unsolved tensions that hindered the group in exploring a common design solution. However, both analyses offer important insights into what’s at stake in adolescent group creativity and how to provide opportunities for trajectories of creative influence and learning.

Material dimensions

The modeling activities posed different challenges. In the block modeling activity we see how a well-defined problem space (e.g., “is the kitchen here or there?”) but also material resources structure many of the participants’ decisions and their collaboration. The properties of the blocks, in terms of representing distinct physical spaces and volumes, prompts the question of how to link them together, which ultimately evolves into the group’s creative solution of a hallway becoming a gallery space. As concrete semiotic means, the space guide and block forms neither hinder nor support the expression of new ideas; the material properties facilitate collaboration in solving the space planning problem and the blocks are easily imagined as the designated spaces they are intended to represent. At the same time, the blocks are malleable enough to function as abstracted semiotic means, expanding the imagination space by becoming blended with concepts of architectural space (Hutchins, Citation2005; Pierroux & Rudi, Citation2020; Zittoun & Gillespie, Citation2016). Other mediational resources facilitate the creative collaboration as well, including gestures and the use of the ruler, becoming imaginary material anchors that support the students in conceptualizing, envisioning and manipulating a physical structure that is not actually present (Goodwin, Citation2013; Hutchins, Citation2005). The proposed design solution is clearly visible to the group members as a model shared in the center of the table, and they are all physically able to reach in and make changes with the same degree of spatial privilege (Engle et al., Citation2014) to publicly imagine connections between the different spaces in the architectural model (Murphy, Citation2004).

When the task of modeling the building’s form meets the block model of the building’s functions, the students have problems reconciling the two types of models, materials and processes (Lehrer & Schauble, Citation2010). The footprint and overall shape of the building are more or less fixed by the block layout, and they are instructed to make the form “on top of” this model. This creates a processual problem in that, as they shift to different materials, the young people are not afforded the kind of back-and-forth experimentation process of professional architects (Pierroux et al., Citation2019), which entails “play” with different kinds of analogue and digital representations, materials and models to generate many ideas about a building’s form. Neither is testing an idea as easy as moving a block but requires creating and expressing a form by manipulating different types of materials. The “professionalness” of some of the modeling materials, such as plastic sheets that are softened in warm water to become moldable, are a further challenge in that they are unfamiliar and limited in availability to each group. Appropriateness of materials was thus crucial for the young people to be able to incorporate them in their interactions to creatively explore and negotiate their different ideas.

Institutional dimensions

There are institutional challenges when designing a touring museum workshop as a learning context for schools: e.g., unknown infrastructures, students and teachers in settings that are always changing; introducing students to unfamiliar content and tasks; time constraints; and an external, touring teacher. Therefore, a jigsaw approach was employed to organize and structure collaboration and knowledge sharing in groups. This approach was effective during the block model activity, as the students referred explicitly to other members’ expert knowledge (i.e. traffic patterns, the sun’s movement across the site, groups of trees they wanted to preserve, and facilities available in the neighborhood). Additionally, the problem space for the block model was well-defined and creativity was “distributed” among resources and materials (Sawyer & DeZutter, Citation2009), including colored blocks accessible to all and a list of space functions mounted to a large board that could be passed around for reference by all group members. An example of how the institutional organization of this activity productively fostered learning and creative collaboration is when Irene assumes the role of monitoring design activity by referencing the space guide at crucial moments in the group’s work, ensuring that the functions were in compliance with recommended planning guidelines. The institutional dimensions of the activity, including the task design and resources, supported learning, collaboration, and creative-imagining processes in the group, evidenced by joint focus, agreement, and mutual elaboration on each other’s proposed ideas. Students demonstrated shared ownership and pride in their design concept when they called over the museum curator, seeking validation for their creative solution from an authority.

The second modeling task represents an ill-defined problem space in architecture, and in art more generally, namely giving form to the object. Such open-ended tasks are challenging in terms of relational thinking and reasoning (Goel & Grafman, Citation2000; Green, Citation2016; Vartanian, Citation2017), and we see that the students struggle in exploring alternatives in this widened, abstract problem space, instead committing early on to specific ideas and “sides.” In professional architectural firms, institutional dimensions play an important role in establishing who has authority and wields creative influence in shaping a building’s form (typically partners and senior designers). Architects know how to negotiate persuasive discussions and how to make merit-based and domain-specific arguments (Vartanian, Citation2017). Therefore, an important finding is that adolescents’ argumentation skills need to be developed within specific art domains, to support justifying, challenging, counterchallenging and conceding arguments when working in open-ended, “creative-imagining” problem spaces. When the domain is esthetics, for example, students need to develop knowledge about what kinds of arguments are valid beyond their own judgments. We note that knowledge dependency, seldom studied in learning in the arts, is a key issue for adolescent creativity in open-ended tasks.

Relational dimensions—Why is creative influence so important?

Teacher training in dialogic scaffolding has been proposed for learning domain-specific ways to argue a design concept (Muller Mirza et al., Citation2009). As Engle et al. (Citation2014) explain, without teacher moderation, a student’s undue or unmerited influence may lead group discussions of scientific concepts and disciplinary knowledge to false or unfounded conclusions, with issues “resolved through social dominance rather than rational argumentation” (p. 246). We see this when Evan attempts to exercise authority and creative influence by referring to knowledge gained through participation in the “Inspiration” expert group the previous day. He does not in this instance justify his argument to the others by referring to context (historical reference) and esthetic qualities (contrast) of the sledding hill forms, a merit-based argument that is domain-specific (architecture). Instead, Evan addresses the group’s challenges by arguing, unconvincingly, the practical functioning of his sledding hill design, thus weakening his creative influence.

In adolescence, without knowledge-based authority to wield creative influence, group participants can claim authority based on personal capacities and recognition from their peers. Applying Engle et al.’s (Citation2014) model of persuasive discussion, group members in the first block modeling activity have “equal access to the conversational floor” and equal “spatial privilege,” with frequent turn-taking among the members and the similar ability to reach and make changes to the model. These relational dimensions are beneficial in creative group collaboration, as “participants often have to know what each other imagines and they often have to imagine what is relevant to the ongoing activity in a relevant way” (Nishizaka, Citation2003, p. 183). In the block modeling activity, Tom establishes influence by being the first to mention the hallway idea. This influence is acknowledged by Evan and Jean in the way they await Tom’s feedback when making suggestions. However, all new ideas that emerge are treated seriously regardless of which participant proposed them; ideas are “picked up” and expanded upon by all participants using the materials at hand, without the need for persuasion. These interactional dynamics foster not only a sense of shared authority but also shared creative influence; the group’s design is clearly not attributable to any single group member but to the group as a whole.

A different relational dynamic emerges during the group’s collaboration on the second modeling task, which breaks down in a conflict over creative influence over the building’s form. In trying to persuade the others to embrace his concept, Evan’s degree of authority as Inspiration expert is challenged by Tom and becomes subject to dispute in a student-led argument involving all group members. The standoff is at least in part age-sensitive, since a developmental trend in adolescence (middle school) is the ability to critically evaluate whether evidence supports a given claim (Andriessen et al., Citation2003). Without a clear framing for making such evaluations, multiple perspectives become too complex for solving an open-ended design task and it becomes difficult to manage tensions that arise. In this context, emotions and personalities became intertwined with the creative-imagining process, impacting the social dynamics (Vygotsky, Citation2004a). Although “access to the conversational floor” was formally maintained and Evan was allowed to argue his idea and authority throughout the activity, the other participants responded negatively as a group to his persuasive attempts, including emphatic outbursts (“But it’s ugly! It won’t work!”). The degree of “spatial privilege” was also an issue in terms of access to materials; not only were some materials complicated to use but there were discussion rules that required agreement about how to proceed with a design. This rule was exploited by group members to constrain Evan’s use of materials (“we have to agree first”), but also constrained the group’s creative-imagining process. The relational conflict over authority is thus compounded by institutional and material dimensions of the activity. Finally, as described in the introduction, neither the students nor the museum educator deemed Evan’s expertise or merit-based arguments influential; the educator allows Evan’s arguments to be rejected by Irene without requesting a similarly merit-based counter-argument. In lieu of shared agreement that creative influence is valued based on knowledge and authority, relational dimensions play an outsized role in group collaboration and creative influence is instead socially negotiated.

Learning in and through the arts

Conceptualizing and modeling possible design solutions in arts-based activities may be viewed as productive and as evidence of learning processes even though consensus by a group is not ultimately reached. Despite the fact that the students in this study do not always productively engage with each other’s creative-imagining processes, they try to find solutions that are coherent within their subjective interpretations of what constitutes a creative solution (). Therefore, when conceptualizing interactions as productive for learning, it is important to acknowledge that reaching consensus is only one part of being creative in a group. Other learning processes such as problematizing, arguing, using multiple sources, and managing and combining concepts and material elements are also part of multidimensional interaction in creative work. The analysis has shown how students draw on different resources and argue in a group for how resources could be used to solve the design task. Multiple perspectives generate valid arguments in arts-based learning activities and these young people use both contrasts and comparisons in their talk and actions to make their arguments more advanced and visible for the other participants in the group. Therefore, a final design product or artwork is but one part of creative processes that involve learning.

The findings presented in this research, although limited in terms of data and analysis from a single empirical study, provide the basis for suggesting some design principles for fostering adolescents’ creative-imagining processes in collaborative learning activities. The first set of design principle addresses potential tensions between different institutional dimensions of learning tasks and activities. A principle for organizing group activities and students’ roles based on models of professional artistic practices would thus be to design for alignment with classroom practices, taking into account tensions between students’ domain skills and knowledge and those of professionals. In art education and in professional arts-related activities, both domain-specific and domain-general skills and knowledge are needed for productive group creativity. The latter are demonstrated by the students in this study when they collaboratively imagined creative solutions to modeling abstracted concepts of architectural space, the main aim of the learning activity. Without domain-specific knowledge, however, domain-general skills are insufficient to support group creativity. This is what we choose to call the knowledge dependency in open-ended tasks. The students were hindered, for example, in using materials in imagination processes when they did not possess the domain-specific skills for expression.

A second set of design principles relates to the appropriateness of materials and resources for learning in the arts. Material artifacts do not serve the same creative-imagining functions for students learning specific aspects in a domain as they do for professionals that have developed deep intuitions about how a design might look; more support may be needed for young students to explore how particular materials can assist them in learning and expressing ideas. As a design principle, then, material opportunities for creative expression must have semiotic properties that are rich in meaning potential but also be designed for facilitating learning and skill levels appropriate for the learners and the task.

Finally, a third set of design principles is needed to address relational dynamics, which are intertwined with institutional and material dimensions of group creativity in adolescence. These principles draw on Engle et al.’s (Citation2014) model of “influence in persuasive discussions,” which consists of concepts from research on persuasion, student-led argumentation, discourse, and classroom discussions. Their four aspects address mainly conversational processes by focusing on the influence of students’ merit-based arguments, authority, access to conversational floor and degree of spatial privilege. Together, these aspects make it possible to understand how influence in social interactions is played out. We recognize that this model enriches the analytic potential for understanding social dynamics and interpersonal relationships in groups. Our conceptual stance extends this model by 1) relating these relational dimensions to creative group processes in an art education context and 2) introducing material and institutional dimensions that influence social interactions in creative group collaboration. Design principles that can foster productive forms of creative influence in a group might include ground rules for dialogue, strategies for dealing with competing ideas, and adult support. However, understandings of design principles for creativity also require further research on age-specific developmental processes. In art education, as this study shows, pedagogical designs for young people may be successfully modeled after professional practice, but fostering processes of imagination requires acknowledging the unique learning trajectories and relational dynamics that enter into group creativity in adolescence.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The data used for this study were collected as part of the project CONTACT (Communicating Organizations in Networks of Art and Cultural Heritage Technologies). We are thankful for the contributions of the many participants in this study, including the museum curators, architects, teachers and students. We thank Joseph Polman, University of Colorado, and members of the research group Living and Learning in the Digital Age at the Department of Education, University of Oslo, for valuable discussions of earlier drafts. We are grateful for the insightful comments and suggestions provided by the anonymous reviewers. We especially thank Guest Editors Keith Sawyer and Erica Halverson for their support and efforts in developing and focusing this contribution.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway, Grant #193011.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- Andriessen, J., Baker, M., & Suthers, D. (Eds.). (2003). Arguing to learn: Confronting cognitions in computer-supported learning environments. Kluwer.

- Andriessen, J. E. B., & Schwarz, B. B. (2009). Argumentative design. In N. Muller Mirza & A.-N. Perret-Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and education: Theoretical foundations and practices (pp. 145–174). Springer US.

- Aronson, E., Blaney, N., Stephin, C., Sikes, J., & Snapp, M. (1978). The jigsaw classroom. Sage Publishing Company.

- Barab, S. A., & Squire, K. D. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_1

- Barron, B. (2003). When smart groups fail. Mind, Culture & Activity, 12(3), 307–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327809JLS1203_1

- Binder, T., De Michelis, G., Ehn, P., Jacucci, G., Linde, P., & Wagner, I. (2011). Design things. MIT Press.

- Derry, S. J., Pea, R. D., Barron, B., Engle, R., Erickson, F., Goldman, R., Hall, R., Koschmann, T., Lemke, J. L., Sherin, M. G., & Sherin, B. L. (2010). Conducting video research in the learning sciences: Guidance on selection, analysis, technology, and ethics. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 19(1), 3–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508400903452884

- Dishke Hondzel, C., & Sørebø Gulliksen, M. (2015). Culture and creativity: Examining variations in divergent thinking within Norwegian and Canadian communities. SAGE Open, 5(4), 2158244015611448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015611448

- Engle, R. A., Langer-Osuna, J. M., & McKinney de Royston, M. (2014). Toward a model of influence in persuasive discussions: Negotiating quality, authority, privilege, and access within a student-led argument. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23(2), 245–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2014.883979

- Fleming, M. (2011). Learning in and through the arts. In J. Sefton-Green, P. Thomson, K. Jones, and L. Bresler (Eds.), The routledge international handbook of creative learning (pp. 177–186). Routledge.

- Gajdamaschko, N. (2005). Vygotsky on imagination: Why an understanding of the imagination is an important issue for schoolteachers. Teaching Education, 16(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1047621052000341581

- Glăveanu, V. P. (2010). Paradigms in the study of creativity: Introducing the perspective of cultural psychology. New Ideas in Psychology, 28(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2009.07.007

- Goel, V., & Grafman, J. (2000). Role of the right prefrontal cortex in ILL-structured planning. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 17(5), 415–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/026432900410775

- Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(10), 1489–1522. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

- Goodwin, C. (2013). The co-operative, transformative organization of human action and knowledge. Journal of Pragmatics, 46(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.09.003

- Green, A. E. (2016). Creativity, within reason: Semantic distance and dynamic state creativity in relational thinking and reasoning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721415618485

- Hernández-Leo, D., Nieves, R., Arroyo, E., Rosales, A., Melero, J., Moreno, P., & Blat, J. (2011). Orchestration signals in the classroom: Managing the jigsaw collaborative learning flow [Paper presentation]. Towards Ubiquitous Learning, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Hutchins, E. (2005). Material anchors for conceptual blends. Journal of Pragmatics, 37(10), 1555–1577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2004.06.008

- Jefferson, G. (1984). On stepwise transition from talk about a trouble to inappropriately next-positioned matters. In J. M. Atkinson & J. C. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies of conversation analysis (pp. 191–222). Cambridge University Press.

- Jordan, B., & Henderson, A. (1995). Interaction analysis. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 4(1), 39–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0401_2

- Kleibeuker, S. W., Koolschijn, P. C. M. P., Jolles, D. D., Schel, M. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Crone, E. A. (2013). Prefrontal cortex involvement in creative problem solving in middle adolescence and adulthood. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 5, 197–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2013.03.003

- Krange, I., & Ludvigsen, S. R. (2008). What does it mean? Students’ procedural and conceptual problem solving in a CSCL environment designed within the field of science education. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 3(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-007-9030-4

- Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2010). What kind of explanation is a model? In M. K. Stein & L. Kucan (Eds.), Instructional explanations in the disciplines (pp. 9–22). Springer US.

- Ludvigsen, S., Gundersen, E., Indregard, S., Ishaq, B., Kleven, K., Korpås, T., Rasmussen, J., Rege, M., Rose, S., Sundberg, D., & Øye, H. (2015). The school of the future. Renewal of subjects and competences (Vol. 15). Official Norwegian Reports NOU. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/nou-2015-8/id2417001/

- McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. (2018). Conducting educational design research. Routledge.

- Moran, S., & John-Steiner, V. (2003). Creativity in the making. Vygotsky’s contemporary contribution to the dialectic of development and creativity. In V. J.-S. R. Keith Sawyer, S. Moran, R. J. Sternberg, D. H. Feldman, J. Nakamura, & M. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Creativity and development (Counterpoints: Cognition, memory, and language) (pp. 61–90). Oxford University Press.

- Muller Mirza, N., Perret-Clermont, A. N., Tartas, V., & Iannaccone, A. (2009). Psychosocial processes in argumentation. In N. Muller Mirza & A.-N. Perret-Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and education: Theoretical foundations and practices (pp. 67–90). Springer US.

- Murphy, K. M. (2004). Imagination as joint activity. Mind, Culture & Activity, 11(4), 267–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca1104_3

- Murphy, K., Ivarsson, J., & Lymer, G. (2012). Embodied reasoning in architectural critique. Design Studies, 33(6), 530–556. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2012.06.005

- Nishizaka, A. (2003). Imagination in action. Theory & Psychology, 13(2), 177–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354303013002002

- Norwegian Ministry of Culture and Church Affairs. (2007-2008). A cultural rucksack for the future (Report No. 8 (2007–2008) to the Storting). 113 pp.

- Pierroux, P., Knutson, K., & Crowley, K. (in press). Informal learning in museums. In K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (2nd ed., Chap. 22). Cambridge University Press.

- Pierroux, P., & Rudi, J. (2020). Teaching composition with digital tools: A domain-specific perspective. In K. Knutson, T. Okada, & K. Crowley (Eds.), Multidisciplinary approaches to art learning and creativity: Fostering artistic exploration in formal and informal settings (pp. 124–145). Routledge.

- Pierroux, P., Sauge, B., & Steier, R. (2021). Exhibitions as a collaborative research space for university-museum partnerships. In M. Achiam, K. Drotner, & M. Haldrup (Eds.), Experimental museology: Institutions, representations, users (pp. 149–166). Routledge.

- Pierroux, P., Steier, R., & Sauge, B. (2019). Born digital architectural projects: Imagining, designing and exhibiting practices. In Å. Mäkitalo, T. Nicewonger, & M. Elam (Eds.), Designs for experimentation and inquiry: Approaching learning and knowing in digital transformation (pp. 87–109). Routledge.

- Roth, W.-M. (2001). Situating cognition. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 10(1 & 2), 27–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327809JLS10-1-2_4

- Rubin, B. C. (2019). Theorizing context in DBR: Integrating critical civic learning into the U.S. history curriculum. In B. C. Rubin, E. B. Freedman, & J. Kim (Eds.), Design research in social studies education: Critical lessons from an emerging field (pp. 205–223). Routledge.

- Sawyer, K., & DeZutter, S. (2009). Distributed creativity: How collective creations emerge from collaboration. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3(2), 81–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013282

- Sawyer, K. (2012). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Schwarz, B. B. (2009). Argumentation and learning. In N. Muller Mirza & A.-N. Perret-Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and education: Theoretical foundations and practices (pp. 91–126). Springer US.

- Smørdal, O., Nesnass, R., Pierroux, P., & Sem, I. (2014, October 25–26). Snøkult: Designing a multitouch table for co-composition in an educational setting [Paper presentation]. FabLearn: Conference on Creativity and Fabrication in Education, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA.

- Steier, R., Kersting, M., & Silseth, K. (2019). Imagining with improvised representations in CSCL environments. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 14(1), 109–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-019-09295-1

- Steier, R., & Pierroux, P. (2011). “What is ‘the concept’?” Sites of conceptual formation in a touring architecture workshop. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 6(3), 139–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/1891-943X-2011-03-03

- Stuedahl, D. (2019). Participation in design and changing practices of museum development. In K. Drotner, V. Dziekan, R. Parry, & K. C. Schrøder (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of museums, media and cmmunication (pp. 219–231). Routledge.

- Van de Sande, C. C., & Greeno, J. G. (2012). Achieving alignment of perspectival framings in problem-solving discourse. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2011.639000

- Vartanian, O. (2017). The creation and aesthetic appreciation of architecture. In J. C. Kaufman, V. P. Glăveanu, & J. Baer (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity across domains (pp. 110–122). Cambridge University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, eds.). Harvard University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (2004a). Development of thinking and formation of concepts in the adolescent. In R. W. Rieber & D. K. Robinson (Eds.), The essential Vygotsky (pp. 415–470). Kluwer.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (2004b). Imagination and creativity in childhood. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10610405.2004.11059210

- Zittoun, T., & Gillespie, A. (2016). Imagination in human and cultural development. Routledge.