Abstract

Surveys were collected to assess Forest Service (FS) resource managers’ perceptions, attitudes, and informational needs related to climate change and its potential impacts on forests and grasslands. Resource managers with three background types were surveyed. All participants generally considered themselves to be well-informed on climate change issues, although each resource manager group had different perceptions of climate change effects on natural resources. They shared similar views on the most potentially useful sources of information and that there was less concern at the Ranger District level about climate change. Administrative issues, including funding, were viewed by all participants as serious obstacles inhibiting agency action. Results of these surveys should provide insight for increasing science delivery efforts, providing educational opportunities, and developing guidance and training for FS resource managers. As a result, the agency can continue to provide science-based tools which assist in conserving and maintaining healthy, resilient ecosystems.

INTRODUCTION

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (Nakićenović & Swart, Citation2000) projects a 25 to 90% increase of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions between 2000 and 2030, leading to a warming of about 0.2°C per decade and alterations in regional patterns of temperature, precipitation, and wind. Additionally, anthropogenic disturbances such as habitat fragmentation, pollution, and the introduction of exotic species may interact with climate changes at small and large geographic scales (Mantyka-Pringle, Martin, & Rhodes, Citation2012). As a result of these stressors, future ecosystems are likely to differ from current and past conditions. Land management strategies must be effective in restoring and sustaining healthy ecosystems so as to provide capable levels of ecosystem services, goods, and benefits for future generations in a changing environment.

Forest and grassland ecosystems provide many goods and services—including biodiversity refuges, regulation of the hydrologic cycle, wildlife food supplies, recreational opportunities, timber, energy, and other forest products (Fischlin et al., Citation2007). In addition, these ecosystems also play important roles in the global carbon cycle by capturing and storing large amounts of carbon and contributing greatly to terrestrial net primary productivity. For instance, forests cover approximately 30% of Earth’s surface and store about 45% of terrestrial carbon (Malmsheimer et al., Citation2011). In addition, forest products in use and in landfills store a significant amount of carbon, and wood-based energy and bioproducts are sustainable substitutes for fossil fuel-intensive products (McKechnie, Colombo, Chen, Mabee, & MacLean, Citation2011). The interactions between forest and atmospheric processes are complex, but it is widely understood that climate change may negatively affect ecosystem functions within forests and that forests can be managed to mitigate climate change (Malmsheimer et al., Citation2011).

Several studies have sought to quantify both the validity of climate change information sources and public perceptions of climate change issues (Akerlof et al., Citation2010; Weber & Stern, Citation2011; Whitmarsh, Citation2011); however, there are fewer studies taking a similar approach with so-called scientific “experts.” Understanding the perceptions of resource managers regarding climate change-related risk may suggest the likelihood of their participation in adaptation and mitigation strategies, as well as in educational opportunities (Lenart & Jones, Citation2014).

The study presented here was developed to assess United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service (FS) resource managers’ climate change perceptions and understand science delivery needs related to climate change and its potential impacts on natural resources. This study was also conducted to report the similarities and differences in climate change perceptions between professionals with different backgrounds working in resource management (climate change coordinators, silviculturists and rangeland managers, and pest managers). This allows for the identification of how the specific background and work done by employees in certain disciplines may affect personal views on a variety of climate change issues and distinguishes those views from those of other types of resource managers. In addition, recognizing the views of these experts helps illuminate current administrative and/or policy needs, useful scientific products and tools, current obstacles in addressing climate change, and highest priority needs on National Forests and Grasslands to increase the effectiveness of agency land management activities. The importance of adapting to climate change is integrated throughout the Forest Service Strategic Plan (2007–2012) and is important to the agency’s mission to sustain the health and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands.

METHODS

This study was based on the second phase of the methodology developed by Moser and Tribbia (Citation2007), used to study coastal managers’ attitudes and knowledge concerning coastal vulnerability to impacts of climate change. Their survey was adapted for use with FS resource managers in the current study. In 2008, the FS held a rangers meeting in Region 1 (R1) where the original idea of using this survey to investigate resource managers’ perceptions and knowledge was presented. Scientists from the FS Rocky Mountain Research StationFootnote1 and resource professionals from the R1 Regional OfficeFootnote2 adapted Moser and Tribbia’s survey to assess FS resource managers’ perceptions of climate change.

The survey consisted of 64 multiple-choice informational questions. Participants were also asked to name specific scientific tools and products that improve their work and knowledge in climate change science and to propose other resources and tools which would be useful. The total survey population consisted of 317 FS resource managers who influence decision-making for forest management activities. The survey covered all National Forests and Grasslands. A subset of resource managers with different backgrounds took part in the survey ().

TABLE 1 Survey Respondents (n = 173)

The survey was first conducted at a work meeting of pest managers, while the survey for climate change coordinators and silviculturists and rangeland managers was sent electronically using SurveyMonkey® (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA, USA), along with an email asking individuals to respond. There was no difference between the questions of the hardcopy and electronic surveys. All survey questions are shown in the Appendix and focused on participants’ personal opinions on the following subjects:

General views regarding climate change

Expected climate change effects in forest and grassland ecosystems

Perceived barriers to addressing climate change

Sources of information currently used

Potentially useful sources of information

High priority needs of National Forests and Grasslands

Specific tools and products to improve work and knowledge in climate change science

From the 317 survey requests sent, 173 employees provided full responses. Whether or not a survey was filled out was random because it was not mandatory to respond. The overall average response rate for the three surveys conducted was 54.6%, which is considered a good representation of FS resource managers for this study. The information was tabulated and analyzed by comparing the percentages of employees responding to the options within each question posed. Additional analyses were conducted, which included the estimation of the variance and standard error for each one of the responses for the variable of interest in each professional group. This was done using a simple random sampling design for a subclass proportion for all the variables. In order to test for an effect of professional background of each group on the questions presented, a simple random experimental design was used to test for a significant difference between the responses provided by each group for the main six general topics of the survey. To conduct the experimental analysis, the percentage values of the different variables were transformed into radianes using the square root of the arcsin transformation. Finally, the main variable of interest, which in this case was the statement that climate change is not happening and will not cause problems, was used to estimate the standard error to calculate the confidence level of the survey. The overall standard error of the study was 0.02 at the 95% confidence level.

RESULTS

General Views on Climate Change

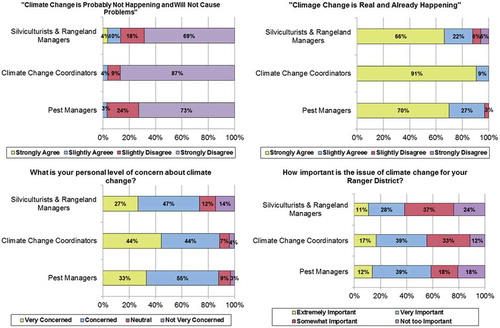

Participants were asked to answer three questions regarding their personal views of climate change and an additional question about how important they feel the issue is to their Ranger District (). Although the majority of respondents in all groups recorded some level of concern over climate change, the climate change coordinators reported the most belief in climate change being a real issue, with 91% of participants strongly agreeing with the statement “climate change is real and already happening.” The other 9% slightly agreed with this statement. For silviculturists and rangeland managers and pest managers, 66 and 70% of respondents, respectively, strongly agreed with this statement, and 34 and 30% of participants in both groups either slightly agreed or disagreed. Additionally, 44% of climate change coordinators considered themselves to be “very concerned” about climate change, as opposed to 27% of silviculturists and rangeland managers and 33% of pest managers. However, a large number of participants in all three groups considered themselves to be at least “concerned,” varying from 74 to 89%, and only a small portion of each group responded “neutral” or “not very concerned.” Despite this overall high level of concern and belief that climate change is already happening, 32 to 61% of participants felt that the issue of climate change was “somewhat important” or “not too important” at the local Ranger District level.

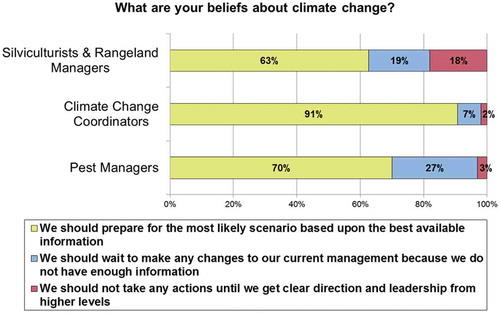

Resource Manager Beliefs about Climate Change and Expected Climate Change Effects

Participants were asked about their personal beliefs concerning climate change and were given three options about how the subject should be approached (). The majority of respondents agreed with the statement “we should prepare for the most likely scenario based upon the best available information,” although the highest level of agreement with the statement was found in climate change coordinators (91%). There was a variation among the respondents ranging between 7 and 27% indicating that the FS should wait to make changes to management because we do not have enough information. Also, 18% of silviculturists and rangeland managers felt that no action should be taken until clear direction from higher levels is received.

TABLE 2 Expected Climate Change Effects Expressed as Percent Possibility of Occurrence

TABLE 3 Analysis of Variance for Each Major Survey Topic for All Professional Groups

Respondents were asked to categorize the possibility of 10 potential expected effects of climate change on forest ecosystems (). Resource managers replied most often that there was a high or moderate likelihood that climate change would affect forest ecosystem characteristics including habitats/species at high elevations, regeneration failures for some tree species, distribution of trees and other species, increased insect-related tree mortality, wildlife habitat distribution, decreased summer stream flows, loss of native fish habitat, increased flooding, and recreation use patterns. However, most participants agreed that distribution of trees and other species and increased insect mortality of trees were among the issues with the highest possibility of being affected by climate change ().

Climate change coordinators indicated overall higher possibilities of climate change affecting forest and grassland ecosystems in many ways than the other resource managers. This is especially true, and is shown when combining the high and moderate possibility categories, for the aquatic-related problems in the survey, which included issues regarding flooding (86%), summer stream flows (92%), and loss of native fish habitat (94%). Pest managers assigned the highest possibilities to changes in tree distribution (85%), insect mortality of trees (85%), and changes in habitats and species at high elevations (91%). Silviculturists and rangeland managers assigned the highest concern to changes in fire severity (83%), insect-related tree mortality (80%), and changes in tree distribution (77%). From all three groups, changes in forage production and recreation use patterns received the least amount of concern as being one of the highest possibility climate change effects. The standard error for the answers provided by all professional groups for these questions varied from less than 1% up to 5% (). The results of the analysis of variance applied () indicated no significant evidence of the effect of the professional background of each professional group in the answers provided to the questions regarding the potential expected effects of climate change on forest ecosystems.

Perceived Hurdles to Addressing Climate Change

Survey participants were asked to identify hurdles which prevent them from addressing climate change issues (). Funding and currently pressing issues were identified as the main two hurdles by all three groups between a range of 70–81 and 61–70%, respectively. Following these hurdles, resource managers considered uncertain effectiveness to be a major challenge (54–64%), as well as lack of guidance, information, and tools for pest managers and silviculturists and rangeland managers. Lack of technical assistance from state or regional offices and lack of importance to staff or leadership are two of the issues that tended to not be viewed as a big hurdle by respondents from all groups. The biggest discrepancies between groups occurred with the issues of lack of social acceptance (53% of climate change coordinators considered this a big hurdle compared to 33% for the other two groups) and the fact that the science is too uncertain (23% of silviculturists and rangeland managers and 22% of climate change coordinators did not see this as being a hurdle, while only 3% of pest managers felt this way). Some other opinions expressed include opposition from stakeholders (21 to 37% as a hurdle), lack of public awareness (24 to 43%), and no legal mandate or policy direction (33 to 49%). The range of variation on the standard error for the responses of all professional groups for these questions was between less than 1 and 4% (). These values for the standard error show consistency among respondents on the perception of hurdles which prevent them from addressing climate change issues in their work. The results of the analysis of variance applied () indicated no significant evidence of the effect of the professional background of each professional group in the answers provided to the questions regarding the perception of hurdles which prevent them from addressing climate change issues in their works.

TABLE 4 Perceived Hurdles to Addressing Climate Change Expressed as Percent Size of Hurdle

Sources of Information

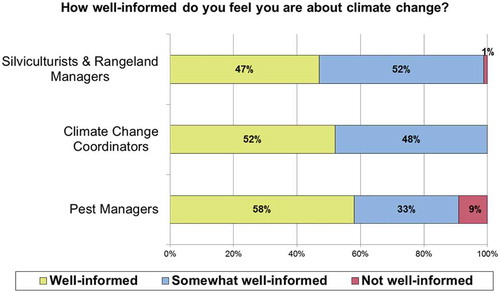

When asked how well-informed the respondents felt they were about climate change, over 90% of respondents from all groups considered themselves well-informed or somewhat well-informed. Additionally, while a small percentage of pest managers (9%) and silviculturists and rangeland managers (1%) considered themselves to be not well-informed on the issue, none (0%) of the climate change coordinators placed themselves in that category ().

Respondents were asked to rate the importance of sources of information of climate change science (). A large percentage of all three groups considered agency workshops and conferences “very important.” Climate change coordinators ranked local and regional experts as “extremely important” resources (42%) and pest managers ranked them as “very important” (61%). Silviculturists and rangeland managers responded that research publications were “very important” (43%). All three groups ranked newspapers and magazines as the least important sources of information (33 to 42%). Additionally, resource managers had a varied response regarding the Internet as a source of information, although a large portion of pest managers viewed the Internet as “not too important” (34%). The range of variation on the standard error for the responses of all professional groups for these questions was between less than 1 and 4% (), showing consistency among respondents on the sources of information on climate change issues in their work. The results of the analysis of variance applied () indicated no significant evidence of the effect of the professional background of each professional group in the answers provided to the questions regarding the sources of information for climate change.

TABLE 5 Percent of Respondents Placing Importance on Currently Used Sources of Information

TABLE 6 Percent of Respondents Placing Usefulness on Potentially Useful Sources of Information

Potentially Useful Sources of Information

Potentially useful sources of information that respondents were asked to address are presented in . Online videos of expert presentation had a good acceptance among silviculturists and rangeland managers and climate change coordinators, varying from 33 to 44% as “very useful.” Mutual learning workshops were considered “very useful” for a good percentage of resource managers, varying from 30 to 49%. Furthermore, web-based information and tools were regarded as “very useful” for all resource manager groups, ranging between 34 and 42%. Conferences presenting information and tools were seen as “very useful” for climate change coordinators (38%) and pest managers (49%). Syntheses of scientific information were rated as the most useful source of information by all three groups of respondents (39–54% “extremely useful”), followed by hands-on training of information and tools (24–42% “extremely useful”). The range of variation on the standard error for the responses of all professional groups for these questions was between less than 1 and 4% (). These values for the standard error show consistency among respondents on the potentially useful sources of information addressing climate change issues about their work. The results of the analysis of variance applied () indicated no significant evidence of the effect of the professional background of each professional group in the answers provided to the questions regarding the potentially useful sources of information on climate change.

TABLE 7 Percent of Respondents Placing Importance on High Priority Needs of National Forests and Grasslands

High Priority Needs of National Forest System Professionals

The information and tools the respondents were asked to classify in terms of need are shown in . Climate change coordinators responded that succinct syntheses of scientific information and adaptation strategies were the most important needs (56 and 54%, respectively), followed closely by policy guidance (50%). Pest managers rated invasive species (58%) and insects and disease mortality (48%) as the most important needs. Silviculturists and rangeland managers responded that invasive species were an “extremely important” information need (40%), along with ecosystem restoration (45%). For all groups, infrastructure maintenance (8–22%) and unmanaged or illegal motorized recreation (13–21%) ranked low in importance.

The biggest differences seen between groups are in succinct syntheses of scientific information (56% “extremely important” to climate change coordinators versus 33 and 27% to pest managers and silviculturists and rangeland managers, respectively), insects and disease mortality (48% “extremely important” to pest managers versus 23% of silviculturists and rangeland managers), policy guidance (50% “extremely important” to climate change coordinators versus 22% of pest managers), and adaptation strategies (54% “extremely important” to climate change coordinators versus 33 and 34% of pest managers and silviculturists and rangeland managers, respectively). The range of variation on the standard error for the responses of all professional groups for these questions was between less than 1 and 4% (). These values for the standard error show consistency among respondents for high priority needs of National Forest System professionals for addressing climate change issues. The results of the analysis of variance applied () indicated no significant evidence of the effect of the professional background of each professional group in the answers provided to the questions regarding the high priority needs in order to work on climate change.

DISCUSSION

The overwhelming majority of FS resource managers participating in this survey accepted climate change as fact and respondents considered themselves to be somewhat to well-informed on climate change issues. The majority of respondents agreed with the statement “we should prepare for the most likely scenario based upon the best available information.” As expected, based on the level of knowledge and scientific background of the respondents, along with the nature of working in natural resources management for a government agency, there were many similarities in the survey responses, particularly in administrative needs. Funding, specifically, was seen as one of the main needs for the FS to address more intensively climate change issues in forest ecosystems. This is consistent with the findings of Laskowski and Joyce (Citation2007). Furthermore, there was no significant evidence of the effect of the professional background of each professional group for any set of climate change-related questions posed and the values for the standard error show consistency among respondents regarding their personal views on climate change. The differences seen in the survey questions relate to the nature of the work in the different program areas of the response groups. Diverse perceptions of climate change risks to forest and grassland ecosystems have been seen before in similar surveys of forest planners in Britain (Petr, Boerboom, Ray, & van der Veen, Citation2014). However, the similarities in responses between the groups should inform the agency about where to concentrate efforts. For instance, the perceptions of hurdles and their ranking indicate the highest needs for the agency to consider in addressing the implementation of actions to increase field work addressing climate change effects in the long term.

Currently pressing issues were seen as a major barrier by all respondents, suggesting perhaps that dealing with climate change science is not yet seen as one of the most urgent parts of the job among many staff in the agency. There was also a high degree of agreement among the three groups regarding the most potentially useful sources of information, with the use of online videos of expert presentation, hands-on training of information and tools, and succinct syntheses of scientific information being viewed as the most beneficial of the options presented. With consensus across resource managers with different backgrounds, these sources of information may be perceived as areas where increased organizational effort may take place so that the utilization of new information and products by experts in the field could be as efficient as possible. Science delivery is a challenging interface issue in the FS, even where science delivery has a long and successful tradition, such as in fire science and management (USDA FS, Citation2009). The Forest Service Global Change Research Strategy for climate change addresses science delivery in an effort to transcend traditional or perceived barriers between research and management and between the different disciplinary and administrative structures within the agency. It also seeks to enhance science delivery within the FS and with organizations outside the agency. The FS is one of only a few agencies that combines a mission to manage land with its own research and development branch.

Although there were areas of considerable agreement, some notable trends and divergences of opinion between the groups were seen within the surveys. For nearly every potential climate change effect presented, climate change coordinators responded with more concern than the other two groups, indicating that their worries of climate change effects are strong and encompass all aspects of forests and grasslands. This is especially true for aquatic-related issues, in which pest managers and silviculturists and rangeland managers showed moderate and low concern, respectively. Pest managers and silviculturists and rangeland managers displayed highest concern with the presented issues most closely associated with their particular field and background, such as insect-related tree mortality and changes in tree distribution. Similarly, climate change coordinators viewed some of the highest priority needs of National Forests and Grasslands to be high-level policy issues, such as adaptation strategies and policy guidance, while pest managers and silviculturists and rangeland managers were more focused on specific issues connected to their field of work, including invasive species and insects and disease mortality. Silviculturists and rangeland managers did show higher concern for some issues that affect land management, such as fire severity and ecosystem restoration. Furthermore, the biggest differences in perceived hurdles to climate change issues between the groups were not in the form of administrative or research and development challenges, where responses were generally very similar, but in social perceptions of climate change, such as opposition from stakeholders and lack of social acceptance and awareness.

A wide spectrum of threat perceptions and divergence of expert opinions concerning climate change is not uncommon (Joyce & Haynes, Citation2007). While there may be general agreement in the scientific community with the conclusions of the IPCC regarding the effects of greenhouse gases (Anderegg, Prall, Harold, & Schneider, Citation2010), previous studies have shown varying degrees of consensus among experts participating in surveys similar to the one presented in this study. A high divergence of opinion has been previously shown among climate change experts concerning issues most needing research and the strategies most likely to yield enhanced awareness (Morgan & Keith, Citation1995). Among the possible sources of the degree of consensus among survey respondents, Morgan and Keith (Citation1995) cite varying degrees of familiarity with the relevant science and differences in the intrinsic scientific difficulty of the given issues. That there were no significant differences in the opinions of resource managers in the presented study suggests that managers have a clear understanding of the agency’s message and policies around climate change, and that any differences may occur in the implementation of management strategies according to individual program-specific work descriptions.

The results of the surveys presented in this study can assist researchers in adapting the ways in which information is relayed to other audiences. Sunblad, Biel, and Gärling (Citation2009) confirmed in a survey of different social groups concerning climate change that, as expected, experts were significantly more knowledgeable about climate change causes and consequences than journalists, politicians, and laypersons. Still, distrust of scientific research regarding climate change is common (Leiserowitz, Maibach, Roser-Renouf, Smith, & Dawson, Citation2012; Grotta, Creighton, Schnepf, & Kantor, Citation2013), particularly among specific age, socioeconomic, and political groups (Poortinga, Spence, Whitmarsh, Capstick, & Pidgeon, Citation2011). In this study, while there were some differences between the groups in determining which sources of information are the most useful, all three groups agreed that newspapers and magazines are the least important resources for acquiring climate change knowledge. However, mass media play a key role in framing climate change and relating information to the public (Anderson, Citation2009), and people’s attention to and trust in those sources will determine their perceptions of the information (Weber, Citation2010). This may be an opportunity to increase efforts in relaying pertinent climate change research results to various media resources to ensure that information available to the public is both attention-grabbing and accurate. Knowledge of climate change issues by scientific experts and the efficacy of transmitting that knowledge to other audiences can have significant consequences on the actions of others, such as private forest owners and policy makers. In fact, it has been shown that support for climate change policy action increases when the general public is more knowledgeable on the issues (Black, Hassenzahl, Stephens, Weisel, & Gift, Citation2013). Additionally, more effective everyday actions are likely to be taken by better informed citizens (Sunblad et al., Citation2009). The results of this study can also inform agency leaders of the value of different resources for communicating new information and tools to their staff. For instance, succinct syntheses of scientific information were seen as an extremely valuable resource by all resource managers, and online videos of expert presentations were also seen as a valuable resource by two groups of respondents. The opinions of these experts, who are constantly dealing with acquiring and applying new information and analysis products, can be used to allocate efforts and funds associated with potential resources in the most efficient and productive manner.

Despite the general consensus on the importance of climate change science and the high level of knowledge of the respondents, the perceived lack of importance at the Ranger District level is noteworthy. Respondents generally do not believe that there is a lack of importance of climate change issues to staff or leadership. The concerns over funding and currently pressing issues may be barriers to work more intensively in addressing climate change. Also, the uncertain effectiveness of management strategies may be a major problem preventing a greater sense of urgency in the field, along with the fact that climate change impacts may often be perceived to be far into the future. Because the climate benefits of forests from sequestering carbon are becoming better recognized and accepted by the public, this is an opportune time for policies to be fashioned to mitigate climate change effects. Adaptation strategies should be applied now to ensure that forest and grassland ecosystems are managed to sustainably provide needed goods and services into a changing future. The results of this expert survey can help inform the FS on ways to address the most urgent issues, the most effective tools and products, and the greatest impediments to effectively managing natural resources moving into an uncertain future.

CONCLUSIONS

This study was developed to evaluate FS resource managers’ perceptions on addressing climate change and understand science delivery needs and the potential impacts of climate change on natural resources. Some conclusions drawn from the surveys are reported below:

The majority of respondents agreed with the statement “we should prepare for the most likely scenario based upon the best available information,” although each land manager group had different perceptions of climate change effects on natural resources.

Major administrative hurdles were seen as being serious impediments by all groups to addressing climate change issues in the agency. Funding and currently pressing issues were seen as barriers to the FS working more intensively on climate change issues affecting natural resources.

There is a high degree of agreement among resource managers regarding the most potentially useful sources of information (succinct syntheses of scientific information, hands-on training of information and tools), indicating that these sources of information could be explored as means of increasing the efficiency of knowledge and technology acquisition by resource managers in the FS.

According to the USDA FS (Citation2011) National Roadmap for Responding to Climate Change, actions resulting from advances in climate change knowledge, both scientific and experiential, can temper the risks and vulnerabilities associated with climate change and its’ impacts. Fortunately, the FS is well-positioned to make those advances. The agency has a century of experience in conducting, synthesizing, and applying forest and grassland research and in examining the social and environmental processes that maintain healthy, resilient ecosystems. Since the 1980s, the agency has studied the actual and potential impacts of climate change and ecosystem response. The FS is currently addressing most of these issues by increasing the educational opportunities for employees, designating climate change coordinators, and developing guidance and training for resource managers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Marilyn Buford, Randy Johnson, Richard Pouyat, Greg Kujawa, David Gwaze, Charlie Richmond, and Larry Stritch, whose comments significantly improved this article.

FUNDING

This research was supported in part by an appointment to the U.S. Forest Service Research Participation Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. ORISE is managed by Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) under DOE contract number DE-AC05-06OR23100. All opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the policies and views of USDA, DOE, or ORAU/ORISE.

Notes

1. Cindy Swanson, Linda Joyce, Dan Williams, Chris Stalling, and Brian Kent.

2. Barry Bollenbacher and Jolyn Wiggins.

REFERENCES

- Akerlof, K., DeBono, R., Berry, P., Leiserowitz, A., Roser-Renouf, C., Clarke, K., … Maibach, E. (2010). Public perceptions of climate change as a human health risk: Surveys of the United States, Canada and Malta. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7, 2559–2606.

- Anderegg, W. R. L., Prall, J. W., Harold, J., & Schneider, S. H. (2010). Expert credibility in climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107(7), 12107–12109.

- Anderson, A. (2009). Media, politics and climate change: Towards a new research agenda. Sociology Compass, 3(2), 166–182.

- Black, B. C., Hassenzahl, D. M., Stephens, J. C., Weisel, G., & Gift, N. (Eds.). (2013). Public attitudes toward climate change in the United States. In Climate change: An encyclopedia of science and history (pp. 1158–1168). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- Fischlin, A., Midgley, G. F., Price, J. T., Leemans, R., Gopal, B., Turley, C., … Velichko, A. A. (2007). Ecosystems, their properties, goods, and services. In M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P. Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden, & C. E. Hanson (Eds.), Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability—Contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 227–228). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Grotta, A. T., Creighton, J. H., Schnepf, C., & Kantor, S. (2013). Family forest owners and climate change: Understanding, attitudes, and educational needs. Journal of Forestry, 111(2), 87–93.

- Joyce, L., & Haynes, R. (2007). The challenges of bringing climate change into natural resource management: A synthesis. In L. Joyce, R. Haynes, R. White, & R. J. Barbour (Eds.), Bringing climate change into natural resource management: Proceedings (General Technical Report PNW-GTR-706, pp. 91–108). Portland, OR: USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

- Laskowski, M. & Joyce, L. (2007). Natural resource managers respond to climate change: A look at actions, challenges and trends. In L. Joyce, R. Haynes, R. White, & R. J. Barbour (Eds.), Bringing climate change into natural resource management: Proceedings (General Technical Report PNW-GTR-706, pp. 142–143). Portland, OR: USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

- Leiserowitz, A. A., Maibach, E. W., Roser-Renouf, C., Smith, N., & Dawson, E. (2012). Climategate, public opinion, and the loss of trust. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(6), 818–837.

- Lenart, M., & Jones, C. (2014). Perceptions on climate change correlate with willingness to undertake some forestry adaptation and mitigation practices. Journal of Forestry, 112(6), 553–563.

- Malmsheimer, R. W., Bowyer, J. L., Fried, J. S., Gee, E., Izlar, R. L., Miner, R. A., … Stewart, W. C. (2011). Managing forests because carbon matters: Integrating energy, products, and land management policy. Journal of Forestry, 109(7S), S7–S50.

- Mantyka-Pringle, C. S., Martin, T. G., & Rhodes, J. R. (2012). Interactions between climate and habitat loss effects on biodiversity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Change Biology, 18, 1239–1252.

- McKechnie, J., Colombo, S., Chen, J., Mabee, W., & MacLean, H. L. (2011). Forest bioenergy or forest carbon? Assessing trade-offs in greenhouse gas mitigation with wood-based fuels. Environmental Science and Technology, 45, 789–795.

- Morgan, M. G., & Keith, D. W. (1995). Subjective judgments by climate experts. Environmental Science and Technology, 29(10), 468–476.

- Moser, C. S., & Tribbia, J. (2007, October). Vulnerability to coastal impacts of climate change: Coastal managers’ attitudes, knowledge, perceptions, and actions. Retrieved from http://www.susannemoser.com/documents/Moser-Tribbia_attitudesknowledgeperceptionsactions_CEC-500-2007-082.PDF

- Nakićenović, N., & Swart, R. (Eds.). (2000). Special report on emissions scenarios: A special report of Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Petr, M., Boerboom, L., Ray, D., & van der Veen, A. (2014). An uncertainty assessment framework for forest planning adaptation to climate change. Forest Policy and Economics, 41, 1–11.

- Poortinga, W., Spence, A., Whitmarsh, L., Capstick, S., & Pidgeon, N. F. (2011). Uncertain climate: An investigation into public scepticism about anthropogenic climate change. Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions, 21, 1015–1024.

- Sunblad, E.-L., Biel, A., & Gärling, T. (2009). Knowledge and confidence in knowledge about climate change among experts, journalists, politicians, and laypersons. Environment and Behavior, 41, 281–302.

- USDA Forest Service. (2007). USDA Forest Service strategic plan FY 2007–2012. Washington, DC: Author.

- USDA Forest Service. (2009, June). Forest Service global change research strategy, 2009–2019 (FS917a). Washington, DC: Author.

- USDA Forest Service. (2011). National roadmap for responding to climate change. Washington, DC: Author.

- Weber, E. U. (2010). What shapes perceptions of climate change? Climate Change, 1(3), 332–342.

- Weber, E. U., & Stern, P. C. (2011). Public understanding of climate change in the United States. American Psychologist, 66(4), 315–328.

- Whitmarsh, L. (2011). Skepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and changes over time. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 690–700.

APPENDIXTABLE A1 Survey Questions