ABSTRACT

In the waters of the Southern Baltic, off the island of Stora Ekön, lies the wreck of a ship lost in 1495 belonging to King John (Hans) of Denmark (1455–1513). This paper draws on the archaeological investigation of the site since 2013 and summarizes previous archaeological and historical research. In its design, construction, and weapons technology the ship is both a rare example of a large carvel-built ‘great ship’ from the final phase of the Middle Ages and, in its role as floating embassy, a manifestation of socio-political processes of change that transitioned medieval Europe to a global, maritime world.

Introduction: Background

In the archipelago outside the modern Swedish town of Ronneby, in 10 m of water, rests a large shipwreck from the late fifteenth century (). The hull has opened up and fallen outwards and various parts of the ship lie scattered on the bottom and are partly covered by sediment.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of the site of Grifun/Gribshund and important contemporary places referred to in the text.

Figure 2. King Johńs Grifun/Gribshund sank close to the island Stora Ekön outside the town of Ronneby in present-day southern Sweden.

Figure 3. The landward side of Stora Ekön was a good natural harbour with protection from the sea and good holding ground for anchoring. King John anchored here with his fleet on his way to an important meeting in Kalmar in the early summer of 1495. A sudden fire and explosion on his flagship caused its rapid sinking. (Photo: Johan Rönnby).

The wreck was discovered as early as 1971 by a local diving club and for many years the old wooden wreck was a popular place for scuba diving (Björk, Citation2016). Ideas of its date remained vague until the discovery of what appeared to be archaic carriages for iron guns. In response, a team from Kalmar County Museum, led by Lars Einarsson, visited the site in the 2000s during which they conducted several periods of fieldwork (Einarsson, Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Citation2012; Einarsson & Gainsford, Citation2007; Einarsson & Wallbom, Citation2001, Citation2002). In connection to these investigations, the wreck was suggested by the historian Ingvar Sjöblom to be a ship lost in 1495 belonging to Danish King John (Hans) (1455–1513) called in contemporary sources Grifun or Gribshund (Sjöblom, Citation1997, Citation2015, Citation2019, pp. 33–49).

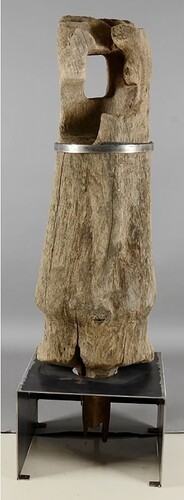

In 2006, a small test excavation was carried out in the middle of the wreck. Although only a very limited area was investigated, the excavation nevertheless yielded a considerable and varied quantity of finds materials. These included objects that were presumably personal and/or domestic: wooden vessels, plate fragments, glass, buttons, leather, metal, cherry kernels, and hazelnuts. Other materials seemed to relate to the ship’s equipment and storage: a brick, flint, fragments of corroded iron, and lime from a barrel. The relatively large quantity of osteological material consisted mainly of cut cattle bones and was interpreted as butchered joints of beef packed in the wooden barrels whose remains were also found in the area. In addition to the gun carriages that prompted the investigation, weaponry included crossbow bolt shafts and, despite the generally poor environment for iron preservation, even remnants of chain mail. An extraordinary find was also a miniature gun carriage (Boetius, Citation2011; Jahrehorn, Citation2009). Another significant find made during the earlier phases of work was of a capstan (). It is 1.2 m high (including the 0.30 m long spindle). It was found close to the stem (Einarsson & Wallbom, Citation2002, p. 15; Einarsson, Citation2008a, p. 8).

Figure 4. A capstan, 1.20 m high (0.90 m) and 0.40 m wide, salvaged in investigations in the 1990s. This relatively small example was found in the bow of the wreck (Einarsson & Wallbom, Citation2002, p. 8). (Photo: Blekinge Museum).

To date, remains of 11 wrought iron guns have been found on the wreck. The iron barrels have almost totally disappeared but the wooden carriage beds into which they were fitted are well preserved (). Systematic use of guns on board ships was a relatively new practice at this time. However, there are sources indicating that the first attempts by Danish kings to use guns on board ship go back to at least 1380 (see Mortensen, Citation1999; Rosborn, Citation2009).

Figure 5. Wooden carriage beds for iron guns salvaged from the site now exhibited in Blekinge Museum. Several more guns are probably still to be found on the wreck. Guns for the king’s new ships were important and there are records from 1487 in Copenhagen of a ‘Powder Master’ named Hans and from 1493 of a ‘gun caster’ named Chort. Both were employed by John (Barfod, Citation1990, p. 198). (Photo: Brett Seymour, The Gripshund Project).

Dendrochronological dating of wood samples from some of the ship's timbers showed that they were felled in the winter of 1482/83 on the northeastern side of the Ardennes adjacent to the river Meuse (Maas) (Linderson, Citation2012, Citation2019).

In 2013, Södertörn University began a new study of the fifteenth-century wreck at Stora Ekön as part of a larger study of early modern warships (Rönnby, Citation2019). A number of investigations focusing mainly on ship documentation were then carried out on the wreck between 2013 and 2018 (Eriksson et al., Citation2019; Rönnby, Citation2015, Citation2017). In the autumn of 2019, Södertörn University, in collaboration with Blekinge Museum, Lund University, University of Southampton, University of Connecticut, and several other colleagues, carried out an archaeological excavation on the wreck. A new photogrammetric documentation of the site was completed, and a trench 6 × 2 m was then excavated on the starboard side amidships (Rönnby, Citation2021).

The Site

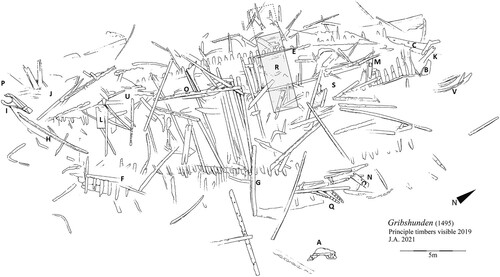

From the remains on the seafloor () and through a systematic analysis of the place, one sees with clarity an example of ship construction from the late 1400s. It is a large ship for the period, around 30 m long and it would have been rigged with three masts. The floors running across the keel, where visible, are made from large grown oak timbers and these, together with the other framing elements, are sandwiched between flush-laid inner and outer oak planking, forming what was then ‘modern’ ‘carvel’ construction. The upper hull both fore and aft were built into bow- and stern castles respectively and as opposed to other parts of the hull, had overlapping planks giving the appearance of clinker construction (discussed below).

Figure 6. Plan of the principal structure visible in 2019. Below the scatter of collapsed, disarticulated timbers there is a considerable volume of coherent structure. The shaded area is the 2019 excavation trench. The dotted line is the trench extension to incorporate outboard timbers. Area labels refer to features mentioned in the text: “Arch”, possibly the “hennegat? (A); Sternpost (B); Rudder (C); Y-shaped crook'd floors (D); Stringer starboard side midships (E); Stringer port side bow (F); Bitt beam (G); Stem (H); Hawse timber (I); Bow area (J); Tiller (K); Mast step for foremast? (L); Mizzen mast step (M); Attachment for capstan (N); Mount for small guns? (O); Location of figurehead beam (P); Standards (Q); 2019 Excavation trench (R); location of 2006 excavation? (S); Box for weapon manufacturing? (U); Part of the stern construction (V). (Plan: Jon Adams from digital photogrammetric surveys 2015-2019).

The lower part of the sternpost remains in its original position, tenoned into the top of the keel and preserved to a height of 1.5 m, with the rebate for the hull planks still visible ( & B). The garboards, the planks closest to the keel, are also both in place. On the basis of what is visible today, it has not yet been possible to determine exactly how the stern higher up was constructed but some larger timbers lying directly behind the stern (see V) are probably parts of the castle structure that projected above the rudder and tiller assembly.

Figure 7. The stern area: the most exposed part of the wreck structure. The lower 1.5 m of the sternpost stands in its original position, tenoned into the keel. Forward of the sternpost several Y-shaped floor timbers remain in position on the keel. (Photo: Johan Rönnby).

Figure 8. Orthographic 3D view of the stern area. On top of the rudder (C) and next to the tiller (K) is a fallen floor timber, with a tenon in the end for attachment to the keel. Between the standing floor timbers (D) and the rudder (C) are several futtocks which have fallen outwards. Further documentation of these would enable a reconstruction of the hull shape of the entire stern. The distance from the in situ part of the sternpost (B) to what has been interpreted as the mizzen mast step (M) is c.4 m. If this is near its original position it indicates the approximate location of the mizzen mast. (Detail from 3D photo plan by Paola Derudas and Brett Seymour, The Gripshund Project).

The 6.5 m-high rudder (C), now detached, lies on the starboard side some 2 m from the stern post. The upper part of the rudder is rounded on its forward edge. The large timber is pierced with two holes, the lower one for a sling, a safety line should the rudder become detached at sea, and the upper for the attachment of the tiller. The tiller is also present, lying between the rudder and the stern and although not preserved to its entire length, is a substantial timber with a square recess in one end and broken at the other (K). Far out on portside (see A) there is a heavy timber, the form of an ‘arch’ suggests it was part of a rounded opening. This may be part of the aperture through which the tiller passed into the stern, called the ‘hennegatt’ in old Dutch (and Danish) ship terminology. This manner is illustrated in many images from the time (see Rönnby, Citation2021, p. 37).

Forward of the sternpost stands a series of seven Y-shaped floor timbers (see & D). These large, grown crotch timbers indicate that the ship had a relativity fine run to the stern and probably a relatively sleek underwater body. One of these grown timbers has fallen, revealing its lower end, and it can be seen that some at least were rebated to the keel in a similar manner to that seen in an early seventeenth-century carvel vessel believed to be Sparrowhawk (lost 1626) (Adams, Citation2013, p. 128).

Most of the wrecks interior construction is covered with sediment. However, a large number of loose deck beams are visible on the site, ranging in length from 6.5–7.5 m, indicating their original locations fore and aft or on different deck levels. The ends of the beams originally rested on beam shelves – heavy stringers placed along the inside of the hull. Other stringers are visible on the starboard side amidships (see E) and in the bow at the port side (see F). The attachment of the beams to the hull was done with grown knees. A number of strong, originally standing knees are lying loose on the wreck site. The bitt beam is located on the port side amidships (see G). This was used to attach the anchor cable and on the upper side there are two recesses for bollards. The bitt beam was originally placed at deck level in the fore part of the ship. Similar constructions can be found on an early sixteenth-century wreck known as Kraveln (Adams & Rönnby, Citation1996, p. 31, Citation2013, p. 111) and Ringaren (Svenwall, Citation1994, p. 60). These very large timbers were strongly braced against beams with their ends locked into the frames, sometimes passing through the sides of the hull in the manner of through-beams, as in various illustrations of the time and in the well-known Mataro votive ship model (De Meer, Citation2020). The bitt beam at the wreck, 5.5 m long, is angled to lock within the hull rather than passing through it.

The stem (see H) is now detached but survives to c.4 m of its original length. Its shape describes a curve of long radius, consistent with the long rake of stem such ships had at this period, for example, the Nämdöfjärd kravel (Adams & Rönnby, Citation2013) or the Basque whaler believed to be San Juan (1565) (Grenier et al., Citation1994). It is partly eroded due to long exposure but still has a distinct rabbet for the outer planking. At the end where it currently extends into the seabed, there is a trace of a scarfed joint, possibly a detail associated with the attachment of the small forecastle.

By the end of the fifteenth century, larger ships usually had three and sometimes four masts. Considering that the water depth is relatively shallow at the site, most of the masts and rigging were probably salvaged after the sinking as these parts would have protruded above the surface. The large main mast was stepped into the keelson amidships, a heavy timber which is presumably preserved deeper down in the sediments. The fore and mizzen masts were significantly smaller during this period, and they were stepped higher up on the decks. What is probably the mast step to the foremast has been found loose near the bow (see L). A 2.44 m-long timber with a square rebate (0.25 × 0.15 m) about 4 m from the stern is the mast step for the mizzen mast (see M & ). The timber is rebated at the ends to lodge into adjacent beams.

Figure 9. Mizzen mast step (M). The size of the rebate is 0.25 × 0.15 m. The length of the timber is 2.44 m. (Photo: Johan Rönnby).

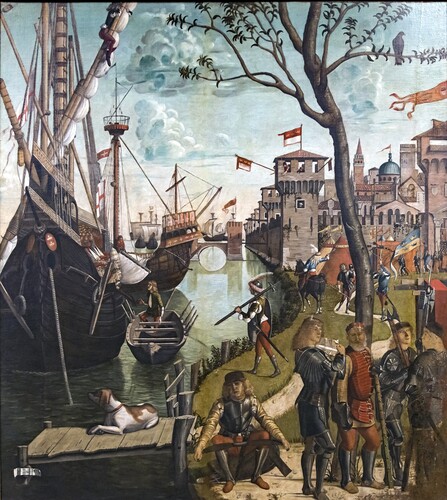

The anchor cables passed through hawse holes on each side of the bow. These had to bear considerable strain and were reinforced by large timbers that were originally placed against the inside of the outer hull planks and braced against adjacent frames. At this height in the hull the outer planking was lapped and so this hawse piece was joggled with diagonally oriented rebates to fit against the overlapping planks (see I & ). Forecastles on ships of this period are represented in many contemporary pictures (). The beam (B) bearing the figurehead (discussed below), together with the hawse timbers enable reconstruction of the triangular castle projecting forward of the stem, especially as the lower part of the underwater hull in this location appears to be preserved relatively intact below the seabed (see J).

Figure 10. A and B. A substantial hawse hole timber with rebates to accommodate the lapstrake planks in the forecastle typical for this period. (Picture from 3D photo plan by Paola Derudas and Brett Seymour and photo by Johan Rönnby).

Figure 11. A carvel-built ship with a triangular lap strake-built forecastle with hawse holes. The place is the inland port of Cologne. ‘Pilgrims arriving to Cologna’ from Legend of St Ursula by Vittore Carpaccio 1490 (part of). Original in Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice (public domain).

Figure 12. Main image: The ‘figurehead’ carving salvaged in 2015. Similar to other late medieval ‘monsters’ that are depicted devouring a human. Inset image: The monster is carved into the end of the strong central beam that supported the triangular forecastle. A) Attachments to crossbeams; B) probable attachment for a standing knight similar to the one in the bow of the Mataro model (after Eriksson, Citation2015). (Photos: Ingemar Lundgren).

Historical Context

The end of the Middle Ages is an exciting and turbulent period in Scandinavian history. The Kalmar Union, in which Denmark, Sweden (at that time including Finland), and Norway were united, remained a reality until 1523. However, the kings based in Denmark for some time had considerable trouble in controlling the eastern Swedish part of the region. Several attempts of breaking up or re-negotiating the terms of the union occurred in connection with the periodic change of thrones. This provided opportunities for strong regional leaders to gain as much power as possible. As a result, for periods during the 1400s, Sweden was ruled by powerful noblemen, called ‘Riksföreståndare’ (head of State) (Lindkvist & Sjöberg, Citation2013, pp. 178–195).

In addition to estates and property, military rearmament and its associated organization was also a central issue for noblemen and powerholders (Hallenberg & Holm, Citation2016; Neuding Skoog, Citation2018). This applied to land warfare but also on the sea. These northern, early modern, ‘princes’, to use the term in the Machiavellian sense (Machiavelli, Citation1513), often possessed several ships, some of them quite large. Investing in a private fleet was a way to maintain their position and enhance wealth and prestige. The powerful Karl Knutsson Bonde (1408–70) who was actually appointed Swedish king on three occasions, seems to have owned several large ships that he also sometimes used for trade with Western Europe. One of his ships was a very large holk, and this ship is known to have arrived in England in 1455 (Glete, Citation2010, p. 59). Sten Sture the Elder (1440–1503), who became the Riksföreståndare from 1470, also had his own fleet and later would indirectly play a part in connection to Grifun/Gribshund (see below). Another example is the powerful Danish nobleman Ivar Axelsson-Tott on Gotland who in 1485 was the owner of a large carvel-built vessel. Even a Swedish bishop like Hans Brask (1448–1536) had his own small fleet (Glete, Citation1976, p. 46, 1977, p. 33, Citation2010, p. 348). Perhaps one of the most renowned examples from this period was the fearless Danish Admiral Sören Norby. During the period 1524–26 his private fleet operated from Gotland, attacking Swedes, Danes, and Germans alike (Larsson, Citation1964, pp. 248–250; Larsson, Citation1986; Barfod, Citation1990, p. 167).

However, new warships and modern guns were very resource intensive. Over time therefore, the possession of larger, well-armed ships becomes something that is concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. During the fifteenth century and in the beginning of the sixteenth century cities such as Lubeck and Danzig linked by their membership of the Hanseatic League were still significant maritime powers in Northern Europe (see Mozejka, Citation2019). But their power declined as the new nation states became more and more dominant. In the case of Sweden, this happened rather later but when it did it was quick and decisive following the new king Gustav Vasa's investment, first in the purchase of ships in the 1520s, then in the building of a new fleet from the beginning of the 1530s (see Adams & Rönnby, Citation2019, pp. 174–178). In Denmark this process began earlier but occurred more gradually under the auspices of the new Oldenburg dynasty of Danish kings, Christian I (1426–81), John I (1455–1513) and Christian II (1481–1559).

In 1486 King John (Hans) signed a letter while aboard a ship that he calls ‘navi nostra Griffone’. The next year this ship is mentioned again as Griffen in a list of Danish ships which King John is going to use for a naval operation near the island of Gotland in the Baltic. Griffen is also mentioned in connection with a voyage to England in 1493 together with the ship Swan. The trip concerns the negotiation of fishing rights around Iceland (an activity ongoing in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries!). On this occasion, what is probably the ship's armament of 56 guns is mentioned. The Master on board at this time is Anders Bryggare (Sjöblom, Citation1997, Citation2015, pp. 33–49; Barfod, Citation1990).

Identification

A ship which is most likely the same one mentioned above as Griffone/Griffen figures in written sources concerning a wrecking 1495, now called Grifun in one contemporary source and the strange name Gribshund (‘Griffin Dog’) in another. It is unclear whether the ship had changed its name in some way. One possibility, impossible to prove, is that ‘-hund’ is a contemporary joke, a nickname for the ship because at a distance the figurehead has a rather dog-like appearance. More likely it was just a different spelling, and it has been suggested that the ‘-hund’ ending is simply a linguistic misunderstanding between Danish and German (Warming, Citation2020b). Calling a ship Griffin was not uncommon during this period and there are several other contemporary examples.

Two historical political events featured the loss of Grifun/Gripshund. Firstly, a civil war that started when the Swedish Riksföreståndare Sten Sture the Elder broke up the Kalmar Union in 1470. The Danish king Christian I (1426–81) tried, but failed, to reconquer Sweden and restore it. Instead, these actions resulted in a decisive Danish defeat at the Battle of Brunkeberg, Stockholm, in 1471. Secondly, Christian I died 1481 and his son John was elected to become the new Danish king. The event created opportunities to re-negotiate the terms of the Kalmar Union. This resulted in the ‘Kalmar recess’ of 1483, and John was then elected to be king also in Norway (Carlsson, Citation1955; Palme, Citation1950). Finally, it was in the beginning of the summer of 1495 that King John was on his way to negotiate with Sten Sture to try and restore the union throne in Sweden as well. The power-hungry Sten Sture had procrastinated for as long as possible, but at last it was agreed that a meeting would take place in the town of Kalmar. Sture was to have made his way to Kalmar with his fleet, said to have included three large, heavily armed carvels (Hedberg Citation1975, pp. 126–127). Meanwhile King John came north from Copenhagen with his fleet and half-way anchored at a sheltered place, probably to hold a pre-meeting on a nearby island. It was here that somehow fire broke out on board the flagship. The king was not on board during the accident, but the sources say that many noblemen, along with gold, silver, furniture, and the king’s ‘best fatabur’ (household) were lost when the great carvel went to the bottom (Warming, Citation2020b). An interesting detail concerns his personal astronomer and ‘mathematicus’ who in the contemporary description of Tyge Krabbe is said to have been killed in the accident (Sjöblom, Citation2015). King John never met Sten Sture that summer but two years later in 1497 he was finally crowned king over the Swedish half of the united Nordic kingdom (Lindkvist & Sjöberg, Citation2013, pp. 188–189).

In 2006 the historian Ingvar Sjöblom concluded that the wreck found in the 1970s in the archipelago outside the town of Ronneby in today’s southern Sweden must be the remains of King Johńs big carvel (Einarsson, Citation2008b, pp. 10–11). The ship's construction and the finds on board make the identification of the wreck as the royal ship lost in 1495 fairly certain. Furthermore, the wreck is located inside an island called St Ekön (‘Oak Island’), and the site of loss recorded in several written sources is said to be ‘Egesund’ outside the town of ‘Rendebye’. The place names and the location further strengthen the case that it is the wreck of King John’s Griffin that lies here on the seabed.

However, there are in all six known, more or less contemporary, written accounts of the wrecking in 1495 and they do not all point to the island outside Ronneby. Also, in some of these accounts other ships are mentioned which apparently wrecked on this occasion. For discussion regarding the reason for this confusion, see Sjöblom, Citation2015 and Warming, Citation2020b.

The Danish Monster

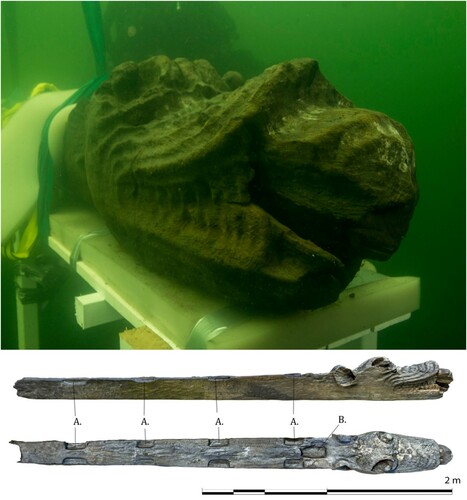

In 2015, perhaps the most spectacular find to date was salvaged from the wreck. A long beam that served as a central support for the triangular forecastle had at one end a large sculpture of a huge grinning monster devouring a screaming man. This symbolic head once projected from the bow of the ship in the manner of a figurehead ().

That it was common to have a figure in the bow of large ships similar to the one salvaged is evident not least from contemporary images and paintings from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It is easy to imagine how the horrifying image in the bow of the ship worked as a weapon of symbolic psychological warfare. In a combat situation, with the high forecastle looming over the waist of an opposing vessel, the enemy crew encountered not only gun shot, arrows and other projectiles but also a slavering monster in the action of swallowing a human being. The clear message was that they were next in line.

Iconographic parallels connect it to the monstrous images and sculptures that can be seen in late medieval churches, cathedrals, and books (cf. Mandeville, Citation1484; Svanberg & Qwarnström, Citation1998). Although late medieval griffins in books, paintings, and heraldry could be depicted quite freely, the design of the figure cannot be directly linked to the ship's name. Perhaps more generally one should see the wooden sculpture as an expression of a general human tendency to animate ships and partly as a long tradition in which monsters and dragons were used in the bow of ships to represent their offensive power as well as the power of the regime (for discussions regarding the figure see Lavér, Citation2017; Eriksson, Citation2019, Citation2020; Rönnby, Citation2020, Citation2021; Warming, Citation2017, Citation2019, p. 105).

An interesting possibility of a more or less direct model for the carved figure on the ship is the coat of arms of the northern Italian Renaissance family Sforza. Indicative of their social importance is that among others working for the powerful dukes in Milan was Leonardo da Vinci. The Sforzás coat of arms depicts a so-called ‘biscione’, a serpent-like heraldic monster devouring a human ().

Figure 13. The coat of arms of the powerful northern Italian Renaissance ducal family Sforza from the period 1475–1500. It shows among other things, a so-called ‘biscione’, a heraldic monstrous serpent devouring a human. The head of the beast is very reminiscent of the wooden figure from Griffin. Is the serpent perhaps a direct inspiration for the figure on the ship? In 1474, Christian I travelled to Italy and met the Pope but also passed Milan and the Sforza family's home region in Lombardy (see Ullidtz, Citation2016, pp. 516–538). ‘Wappen des Herzog von Mailand, Sforza 1475 –1500’. Original in Bavarian State Library, Munich (public domain).

In 1474, King Christian I and Queen Dorothea, parents of the future King John, travelled to Italy and met the Pope but also among other things visited Milan. They were considered highly important guests here and were treated accordingly by Duke Galeazzo Sforza. When they arrived in the city, they were greeted by four hundred flags that on one side had the coat of arms of the Danish king and on the other side the monster biscione of the Sforza family. One thing that was discussed between the various feasts were possible marriage arrangements for prince John. On this trip they also went to the nearby town of Mantua to visit relatives of the queen. In the ducal palace here, there is a fresco from 1474 depicting the Danish king (Ullidtz, Citation2016, pp. 516–538). The journey down to Mantua was probably made by boat along canals and on the river Po in an ornate, luxurious renaissance state barge, a so-called ‘bucintori’ (see Mezzogori, Citation2014).

Is the north Italian heraldic serpent an artistic inspiration for the carved wooden figure in the bow of Griffin, or are there also other personal or commercial explanations behind the reason it occurs on King John’s ship? Anyhow, the events in 1474 illustrates how the Danish king was part of a European network and how symbols were used to demonstrate power and wealth. Exchanging resources and supporting each other with prestige ships was also an important part of the contemporary power relations of the time (discussed further below).

Site Formation and Artefacts

In August 2019, new marine archaeological investigations were carried out on a place amidships the wreck (Rönnby, Citation2021) ( & ). During the excavation there was a clear difference between the areas on the inside of the hull and outside where very few finds were found. The excavation inside the hull was complicated because the thick cultural layer was dominated by more or less complete but partially disintegrated barrels interspersed with firewood logs and other objects, all lying immediately above the ballast (). This apparent chaos initially made object location and juxtaposition difficult to understand. However, beer barrels, fish, silver coins, clothes, fine tableware accessories, firewood, etc., were unlikely to have been stowed in the same space. So the observed distribution seems to indicate a relatively dramatic wrecking process where valuables and equipment from higher decks fell down between the barrels, firewood, and other materials stowed in the hold. A contributory factor may have been an explosion on board described in some of the written accounts. The question is however whether this explains the distribution pattern?

Figure 14. Excavation amidships in 2019 using a dredge. The exposed area is full of remains of barrels and other artifacts. The situation in the trench indicates that the area was disturbed by salvage activity directly after the wrecking in 1495. (Photo: Brett Seymour, The Gripshund Project).

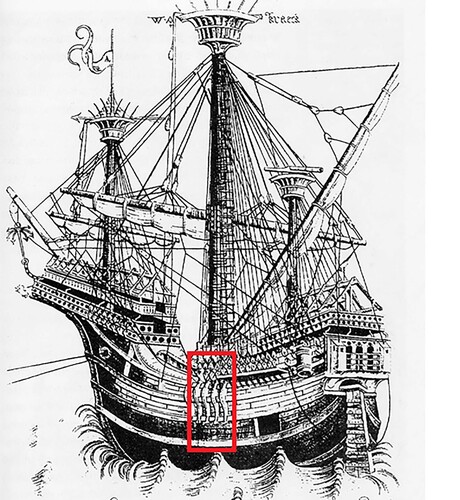

Figure 15. The frequently reproduced image of an early carrack (‘kraeck’) signed W. A. (first published by Max Lehr 1884 in Der Meister WA). The location of the 2019 excavation trench was over the equivalent part of the hull on the starboard side. W. A.s picture is very detailed and shows, among other things, standards on the outside of the hull, a decorated gallery in the stern with two ‘heads’, wooden scaffolding for anti-boarding netting, a small figure and a grapnel anchor in the bow and a swivel gun in the mizzen mast top. The aperture for the tiller (the ‘hennegatt’) is also very clear. It has been suggested that this picture was done in the process of making model ships in connection with the wedding between Charles the Bold of Burgundy and Margaret of York (sister of Edward IV) in 1468. At the feasts held in Bruges, the food was served on the first day in 30 gilded scale models of carracks. As the technique for attaching the shrouds during this period seems to undergo major changes it has been further suggested that this detail was added to the drawing later in the 1480s by W. A. (Sleeswijk, Citation1990). ‘WA Kraeck’. Original in Ashmolean Museum Oxford, inv. PA 1310. (Source: Rönnby & Adams, Citation1994, p. 40).

Figure 16. Ballast of flint shingle at the bottom of the ship. This material could have been obtained in various locations along the Atlantic or North Sea coasts. Above the ballast is firewood of freshly cut birch, 0.5–0.7 m long. These are slightly shorter than similar firewood (also birch) found on Mary Rose (1545) and indicate that the galley was proportionally smaller than on the English ship but was in a similar position in the hold (compare Dobbs Citation2009a, Citation2009b). (Photo: Johan Rönnby).

Another possibility is salvage which, with the ship lying in this depth of water, must have been carried out. None of the deck beams are in place in the area of the trench and moreover no deck planks or bulkheads were found. Salvage often entails breaking into the structure and if so, such violent activity could also explain the agitated situation in the excavated trench. The mixture of different find categories also seems to agree with the excavation results from 2006. This is also supported by a new find of a written source from the 1560s stating that salvage did indeed take place at ‘Griffshunt’ directly after the loss (Warming, Citation2020b).

However, despite salvage operations on the site, several spectacular objects were found during the excavations in 2019. As mentioned, according to written sources, King John lost his ‘best fatabur’ (his property and household) when the ship went to the bottom after the fire on board. This is strongly suggested by the finds of bones, clothing, barrels, kitchen equipment, and wooden barrels. One barrel contained a large number of bones from sturgeon (Macheridis et al., Citation2020). Other household finds are parts of a plate made of tin and a wooden tankard engraved with a royal crown (). Other finds include tools and weapons (see Sjöblom, Citation2021; Warming, Citation2020, Citation2021). A crossbow stock was found but also parts of a ‘hand cannon’ (). This kind of firearm was held under the arm when it was to be used. It appears to have had some form of firing mechanism and is a very early example of its kind. The presence of both crossbows and handguns side-by-side clearly shows the transition period between the Middle Ages and the Modern period. A possibility is that the arms might have belonged to group of German mercenaries that seems to have been onboard (Warming, Citation2020b).

Figure 17. A turned wood tankard with a lid, 220 mm high and with a base diameter of 120 mm. These drinking vessels are known as ‘red jugs’ (röda kannor, Kjellberg, Citation1964). In addition to turned decorative mouldings, the lower part of the body has a large, incised image of a crown which closely corresponds with the heraldic type used during the late fifteenth century in Denmark. For example, in design it is almost identical to the three crowns on the shield of King Hans’ Great Seal. The motif does not necessarily mean that the tankard was the king's personal drinking vessel, but it probably does label it as royal property (Rönnby, Citation2020, pp. 57–58). Indeed, the written sources tell us that the king lost his whole ‘fatabur’ (household) in the wrecking. (Photo: Brett Seymour, The Gripshund Project).

Figure 18. On Griffin, crossbows and crossbow bolts have been found, but also the stock of a small handgun. These began to become common during this time among soldiers and mercenaries and among other technologies are depicted by the contemporary Leonardo da Vinci (Alm, Citation1933, p. 38). The combination of different weapons on board shows that the time of the ship's sinking was a transitional period in several respects (see also Sjöblom, Citation2021; Warming, Citation2020). (Photo: Rolf Warming).

At the risk of gender stereotyping an object, the find of a spindle whorl (Rönnby, Citation2021, p. 115) might indicate that there were women on board the king's ship. The surprisingly small size of the remnants of mail armor (Warming, Citation2021, pp. 135–145) together with the earlier find of the small miniature of a gun carriage (Rönnby, Citation2021, p. 11) could indicate that there were also children present. Did the small bronze ‘hauberk’ and the toy cannon belong to any of King John’s three children? The elder Crown Prince Christian was 14 years old at the time of the sinking, the future South American adventurer and monk Jakob was 13 years old, and the youngest, Elisabeth, was 10 years old.

New Insight into the Construction

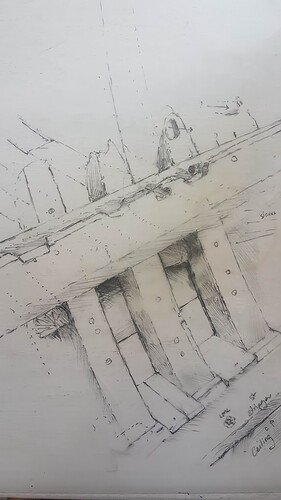

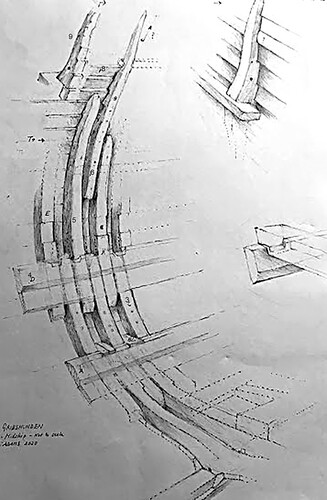

The location of the 2019 trench amidships was chosen specifically to allow examination of the hull's construction in this key diagnostic part of the hull, as well as incorporating parts of the fallen stern castle (). In the deepest, southeastern part of the excavated trench at the bottom, partially covered by ballast, a large stringer 320 mm x 150 mm was visible (see :1). This stringer is located at the turn of the bilge where the hull turns towards the flatter bottom of the ship. It is estimated that the distance from here to the ship's keel and keelson assembly is c.4 m.

Figure 19. 3D digital model of the 2019 trench showing the starboard side and the collapsed hull. Labels refer to the text. (Detail from 3D photo plan by Paola Derudas and Brett Seymour, The Gripshund Project).

Figure 20. Underwater sketch of the lower hull structure showing the relationship of principle timbers and associated fastenings – not to scale (J. Adams).

Figure 21. Reconstruction drawing showing the parts of the hull revealed by the 2019 excavation. Upper, outboard timbers only partially excavated so relationships are hypothetical. Not to scale. (Source: J. Adams).

Below the stringer there is a plank, not fully exposed but part of the inner planking or ceiling is, and this may well be continuous from here to the keelson, literally ‘sealing’ the lower hull. Above the level of the stringer there is no inner planking until the plank and beamshelf assembly that would have supported the first or orlop deck. This construction is consistent with a southern European origin where ventilation between the frames was important (Batchvarov, Citation2011). However, similar arrangements of alternate internal planks and stringers are also a common feature of northern European contemporary ships. Mary Rose (1510–45) has a similar transition from a continuous ceiling in the lower hull (in that case of alternating planks and stringers) to a discontinuous series of stringers leaving the frames exposed between them in the manner seen on Grifun/Gribshund (Adams, Citation2013, p. 77, fig. 4.11). Between the first futtocks (see : 3) there are small fillets of wood (see : 2), preventing the gravel flint ballast, objects, and other things from falling between the frames and accumulating in the bottom of the ship where they would remain inaccessible. These small pieces of wood are made with great accuracy and precision and are well known from other ships of this and subsequent periods ().

At the point where the first futtocks run up past the lower stringer, they are sided between 200–250 mm wide and moulded the same thickness. Here too ‘room and space’ (the sided dimension of the timber and the space between them respectively) are equal. It is likely that the floors are heavier at the keel, perhaps 300 mm sided or more, so with concomitantly less space, c.200 mm. This is therefore a well-built ship of fairly heavy construction with its timbers well squared, i.e. largely free of sapwood. The outer hull planks are oak, and where they can be measured, are about 270 mm wide and about 60 mm thick. No caulking could be observed between the very tight seams but only a relatively small area was accessible.

Just over a metre above the lower stringer is a beam shelf that supported the beams of the orlop deck. The timber is about 300 mm wide and 150 mm thick. It overlies a ceiling plank, probably because it was pulled downwards by the weight of the deck as the hull opened up. Originally it would have been located immediately above the plank. The deck beams are no longer in place but on the upper face of the beam shelf there are dovetailed rebates for the ends of the beams. As the beam shelf rises slightly towards the stern gradually becoming more exposed, so the beam rebates become increasingly eroded making it difficult to discern any pattern. However, variation in size may reflect main beams and half-beams. What are presumably the dovetailed rebates for the main beams flare from c.120 mm out to 200 mm. The distance between the rebates also varies but in the visible section of the beam shelf they are between 300–500 mm indicating a deck capable of bearing considerable weight.

Above the Waterline

As the hull opened up the structure failed along the overlap between the first and second futtocks. The latter, together with their attached planking, hinged outwards and now lie almost horizontal. This is because although the foot of each second futtock fitted closely between the heads of the first futtocks there were no connecting fore and aft fastenings as there were in the framing systems of later periods. As stated, the room and space being the same at this height, the second futtocks (see : 5) are of a similar dimension to the first futtock but from this point, as would be expected, their moulded depth tapers upwards. On the outside of the second futtocks, several hull planks are still connected. Between the futtocks two pieces of wood were found. They may be remnants of the construction process, perhaps temporary support between the futtocks before the hull planks were put in place. A shallow rebate and fastenings on the inboard face of these upper futtocks indicate where there was once a stringer, possible the shelf for the next deck. The large knee located next to the trench may be associated.

A little less than half a metre from the upper end of the second futtocks, the hull planks transition from carvel to what appears to be clinker, at least in the sense they are overlapping (). Strictly speaking it is not clinker because they are not fastened with clenched fastenings through the overlap but were fastened with trenails to the frames. Lapped planking (lap-strake), fashioned from ‘cleft’ board (radially split oak) was used for the bow and stern castles that rose high above the ship's hull because it was light and yet far stronger than sawn board of the same dimensions. Hence these planks are only c.20 mm thick, i.e. much thinner than the carvel planks lower down, so restricting top weight (see : 8).

Figure 22. Diver excavating next to a top timber at the point of transition from the carvel lower hull to the lapstrake stern castle, shown by the ‘joggles’ cut to accommodate the overlapped planks. (Photo: Johan Rönnby).

There are three joggles (rebates) for the lapped planks on the upper end on the outside of the second futtocks. Here also a top timber remains in place (see : 6). As with the first and second futtock overlap, the second and third elements are not attached to each other, but simply overlap for about 1 m. This worked as an integrated structure because of the secure fastening with through-treenails and bolts to the planks (Adams, Citation2013, pp. 53–98, 111–152). Just as the second futtocks accommodate the transition to lapped planking, so do the top timbers. The top timbers are narrower: about 100 mm sided and 150 mm moulded, and taper in both dimensions. They are also less frequent being set at about 1.5 m intervals, in keeping with the need for a light castle structure.

On the outside of the hull another heavy timber was observed at the end of the survey (see : 9). Reached only at the very end of the season, detailed documentation of this construction was not possible. However, it is clear from pictures and paintings that similar forms of external structure were common on early carracks and on their northern European derivatives. Consisting of vertical braces or standards rebated to the wales, these timbers provided additional strengthening and protection. They were often also incorporated in the chain-wale assembly, i.e. the heavy longitudinal wale that acted as a spreader for the shrouds, so-called because at this period the lower ends of the shrouds were secured with two or three long links of chain anchored to bolts in the hull. This seems to be the case here for what is probably the forward end of the main mast chain wale is still in place. A rebated standard rises off the wale and there may be corresponding timbers below. A tentative reconstruction (not to scale) of the structure exposed during the 2019 excavation is shown in .

The development of how shrouds were attached along the sides of the ship seems to have undergone major changes during the period 1470–90 probably because the increasing size of ships necessitated far more robust anchoring of the standing rigging (Sleeswijk, Citation1990). This location on Grffin is probably just aft of where the mainmast should have stood and so is also where a chain-wale should have been located.

The Size?

It is not possible yet to measure the total length of the keel, but the distance from the sternpost to the where the stem assemblage is situated is c.30 m.

In the so-called Timbotta Manuscript from Venice dated 1445, a ship with a keel of 30 m is stated to be 11.8 m wide and 625 tonnes (Gardiner & Unger, Citation1994, p. 82). Lomellina's (1516) keel has been calculated to be 34 m and the breadth 12 m (Guérot & Rieth, Citation1998, Citation2002, Citation2020). Mary Rose (1509) (Marsden, Citation2009) had a keel of 32 m and a maximum width of 11.4 m. She was originally listed as 600 tonnes, later increased to 700, probably as a result of major rebuilding. The large new Danish ship Maria, which was built at the same time as Mary Rose, was larger with a keel recorded as 35.6 m and the beam 12.6 m. The total length for Maria has been estimated at almost 48 m and the ship was perhaps between 700–800 tonnes (Barfod, Citation1990, pp. 150, 170). The big new carvels could also be very high. Gustav Vasa’s Stora Kravel from 1532 was apparently 16 m high from the waterline to the upper part of the stern castle (Gardiner & Unger, Citation1994, p. 83).

However, these large ships can be compared with the archaeological data from the investigation of ‘Kraveln’ in the Stockholm archipelago. The keel of this German-built carvel ship from the beginning of the 1510s is c.18 m and the width of the beams 6.5 m. The size has been estimated to have been around 150–200 tonnes. Despite this relatively small size, being a well-armed carvel, the ship was nevertheless referred to as one of the new Swedish king's best ships (Adams & Rönnby, Citation2013).

There is still great uncertainty regarding the exact size of King Johńs Griffin in comparison with these other ships. But the greatest breadth probably did not exceed 9 m, which means that a keel length is significantly less than 30 m. However, the rake of the stern post and stern structure, as well as the relatively long curve of the stem and projecting bow castle, meant that the overall length may have been nearer 35 m. A ship with an approximate beam of 9.7 m and corresponding keel length in the Timbotta Manuscript had a depth in hold of 3.8 m and is said to have been just over 430 tonnes (Gardiner & Unger, Citation1994, p. 82). If one assumes that Grifun/Gribshund was probably a little narrower than the Venetian ships from 1445, then perhaps a reasonable estimate of King Johńs carvel is around 300–350 tonnes?

Origin

To date, even in the limited time available for investigation, what has been seen of the construction has provided a considerable amount of new information. The trench will need to be extended outboard and to the keel to be able to answer more comprehensively how King John’s Griffin was built. However, the investigations carried out clearly show that she was constructed in a building tradition with southern European roots, namely the carvel technology developed through a fusion of northern and southern European methods, a process that begun in the fourteenth century (Adams, Citation2013; Batchvarov, Citation2011; Friel, Citation1994, Citation1995). The regular, well-squared framing in which the majority of the constituent floors and futtocks were not fastened to each other but clamped between heavy internal and outer planking, was a successful system in a period when compass timber was readily available in long lengths and of appropriate curvature. What the wreck shows is the architectural sophistication that carvel shipbuilding had achieved barely 50 years after the earliest records of carvel ships being built in the North.

The ship development and innovations at the end of the Middle Ages probably initially took place largely in connection with capital-rich Mediterranean cities with a long maritime tradition such as Genoa and Venice. They had both resources and the need to create safe and efficient ships for trade, passenger transport, and war. As important trade centres with long-distance contacts, there were also opportunities to combine different building traditions. In the Italian ports, northern European cogs (though one may have used this term for any single-masted, square-rigged northern ship bearing a stern or centreline rudder), round-bellied southern ships and lateen-rigged caravellas met (Ellmer, Citation1994; Friel, Citation1994, Citation1995). Mediterranean shipbuilders started to incorporate northern features but retaining their frame-led hull construction. It is believed that the vessels that resulted from this technological fusion were called ‘cocha’ for the name becomes prominent just at the time these developments occur. In their turn they voyaged north where they were called carvels (or linguistic variants) and ‘carakes’, possibly referring to the larger ones (Friel, Citation1994, p. 80; Adams, Citation2013, pp. 69–70). Through close economic contacts in the early fifteenth century, these technological innovations spread north to the Atlantic coast and the principal commercial metropolises. The Hanseatic League, while not implementing conscious policy, as an association of port towns would nevertheless have been a vector for the spread of that technology and associated knowledge into the Baltic Sea (see Mozejka, Citation2019). The early Mediterranean carracks can therefore be seen, in terms of construction, as the starting point for the new warships of the powerful and the continued development of European large ships that would soon take place at government shipyards at the beginning of the new era.

Kings and Queens with Connections

Although naval fleets of the medieval world were rather different in nature to the permanent, standing navies that emerged with nation states, there had nevertheless been a long record of large ships being built for and maintained by Danish and other Nordic rulers, as was the case across contemporary Europe. Royal Danish ships are known from the time of Valdemar IV Atterdag (1320–75) and in the early fifteenth century, those of Nordic rulers such as Queen Margaret, King Erik of Pomerania, and King Christopher of Bavaria. These included ships in the written sources called cogs but also holks and krejare, probably large variants of the wider northern European clinker tradition, the prominent shipbuilding traditions of that period. Christian I’s fleet, when he came to power in 1448, probably consisted of similar types but with the new Oldenburg dynasty kings, it becomes clear that Denmark’s maritime ambitions aimed at nothing less than control or at least dominance in the Baltic, but also in ocean-going trade, freebooting and fishing in the North Atlantic (see Barfod Citation1990).

Such aspirations were generated partly through dynastic alliance and the associated network of elite social relations. King John but also his parents, Christian I and Queen Dorothea () as already noted, had extensive European contacts (Ullidtz, Citation2016, Citation2017). Besides rulers in northern Italy and Burgundy, this network included Edward IV (1442–83) in England and Alfonso V (1432–81) in Portugal. In 1468 their daughter Margareta married the Scottish king, James III (1451/2–88) (Barfod, Citation1990, pp. 46–48). The other element of course was material – the new ship. The Danish rulers must have been well acquainted with the most modern ships of the time, where they were built and their capabilities. The first mention of carvel-built ships under the Danish flag is in the year 1474 when the privateer Hans Pothorst operated with two such ships off the west Frisian coast (Barfod, Citation1990, p. 50). Denmark's maritime ambitions become even clearer during king Johńs time. In the aforementioned ship list from the year 1487, two larger ships, David and Griffen, are mentioned, but four others, probably slightly smaller, are also referred to as ‘cravels’.

Figure 23. The parents of King Hans, Christian I, and Queen Dorothea with their coats of arms. Christian was a Nordic statesman and a European ruler who like many of his contemporaries realised the importance of possessing a powerful fleet of these new ships. The Nordic Union was still formally valid and the fields on his shield show the Danish ‘leopard lions’, the Norwegian lion with an axe, the Swedish three crowns and a Wendish linden snake. In the middle the yellow-red Oldenburg family coat of arms. Queen Dorothea was also very politically active. After her husband's death in 1481, she governed the country alongside her son John (Hans). She had meetings with the Pope and in 1486 had several new ships built for the navy. ‘King Christian and Queen Dorothea’ end of fifteenth century. Original in the Museum of National History, Hillerød, Denmark (public domain).

Shipbuilding was of course long established in Denmark and by the second half of the fifteenth century, in common with other maritime states, it had exhibited progressive changes in which both timber conversion and construction characteristics had been exchanged between the various traditions by which we define medieval and modern ship types. For example, late medieval clinker-built merchant vessels built to trade between England and the Continent were far more heavily constructed than their Scandinavian counterparts (Adams & Black, Citation2004; Adams, Citation2013, pp. 81–82). To a great extent their framing systems, associated deck clamp assemblies and knees anticipated what would be needed for carvel construction. Jan Bill, analysing the structural features of several hundred years of Danish ship finds, proposed a way of quantifying this bleed of features between what are otherwise regarded as distinct types (Bill, Citation2009). Of the abandoned ships found when the medieval harbour at Kalmar was drained, all the medieval examples were of the clinker-built ‘keel’ form, yet two showed a remarkable mixing of traits normally associated with what many regard as the cog tradition: Kalmar 2 is clinker-built, exhibiting that tradition’s usual features except for the fact that its hull form with straight stems is very ‘cog-like’. Kalmar 5 is a more typical hull form for Nordic clinker vessels of this size and period but is fastened with turned (twice-bent) nails as used in cogs (Åkerlund, Citation1951; Adams, Citation2013, p. 57).

A New Acquaintance

This general tendency may be reflected in the way that carvel-building was adopted in Denmark. As elsewhere the start must have been influenced by local circumstances and where warships were concerned may have involved partial adaptation to such things as the rig and the design of the castle structures. This was certainly the case in the England in the early 1400s where, spurred by the acquisition of captured Genoese carracks, several large, single-masted, clinker vessels were adapted to carry a multi-masted rig (Friel, Citation1994, p. 80). Subsequently the English Crown continued to have its ships clinker-built and did not commit to building in carvel until the 1480s (Adams, Citation2013, p. 71). Similarly, tentative steps seem to have occurred in Denmark. In the mid-1480s, Christian I's widow (mother of King John), the powerful and influential Queen Dorothea, had a number of new warships built. These were presumably clinker-built because they are referred to by the type names of ‘bardse’, ‘holk’ and ‘playte’ (Jahnke, Citation2006, pp. 85–95), all names which by this date are associated with clinker construction. Had they been carvel-built it is highly likely they would have been recorded as such. Not only are these names associated with clinker construction but in almost all other instances, a carvel-built ship is listed as such (Adams & Rönnby, Citation2013, p. 106; Adams, Citation2013, p. 86).

Soon after, however, in 1488, in the very same year as Henry VII of England was having two great carvels built, Regent (built 1486–87) and Sovereign (built 1487–88), King John commissioned a Dutch shipbuilder to build a new carvel ship on Holmen outside Copenhagen. Thereafter momentum increased, and through both acquisition and construction, carvel-built ships became the core of northern European battle fleets. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, King John started the construction of two new very large ships, Engelen and Maria, which were later passed to his son Christian II. A new state shipyard was located at Engelborg on Slotø, and although Barfod (Citation1990, p. 197, 122) considers it more likely that Engelen was built at Sønderborg and Maria in Copenhagen, the establishment of state facilities for the building and repair of the Crown’s ships and provision for the associate administration was consistent with developments in other northern European maritime states.

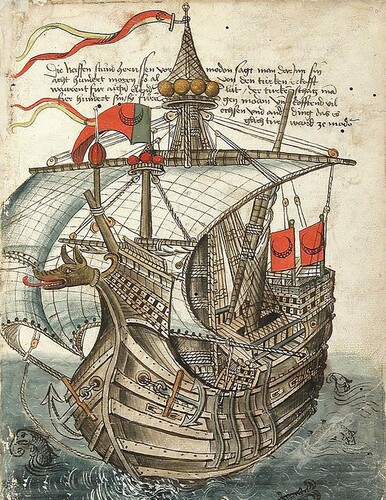

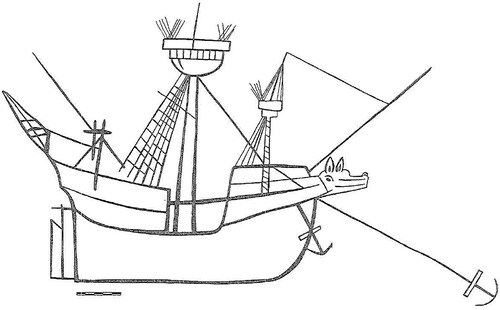

It is in this context the construction and acquisition of new ships likes Griffin is to be understood. The observations regarding the construction made on the wreck so far show that she is typical of the Atlantic and northern-built carvels that were changing the nature of maritime power. We might also call them ‘carrack derivatives’, in that they had their roots in the Mediterranean tradition which during the fifteenth century also spread along the Atlantic coast ( & ).

Figure 24. A new carvel-built ship with a dog-like monster in the bow, from a description of a pilgrimage from Venice to Jerusalem by Conrad Grünenberg in 1486. The ship sails under the Ottoman flag. ‘Beschreibung der Reise von Konstanz nach Jerusalem’ - Cod. St. Peter pap. 32 / Konrad Grünenberg. Original in Badische Landesbibliothek (public domain).

Figure 25. Detail of a painting by Vittore Carpaccio from 1497–98. Large sailing ships in the background are of the same type as the Griffin, one of which has been hauled down for careening. In this age of geographical discovery, conquest and long-distance seafaring, Italian artists also developed geometric perspective painting, enabling the depiction of spatial relationships in new ways. That this is happening at the same time is hardly a coincidence. ‘Meeting of the Betrothed Couple and the Departure of the Pilgrims’ from Legend of St Ursula by Vittore Carpaccio 1490. Original in Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice (Wikimedia Commons, under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license).

The provenance determined by the dendrochronological analysis shows that the timber for the ship comes from the upper part of the river Meuse (Maas) on the west side of the Ardennes (Linderson, Citation2012, Citation2019). Close to here in Flanders and Brabant, at the intersection of France, the Netherlands, and the Burgundian state, and near England across the water, were some of the most powerful and financially influential trading cities in the second half of the fifteenth century, places with strong historical and economic ties with Mediterranean. How closely integrated this area was with the Baltic region and the Mediterranean world during this period is very clear in Beata Mozejko’s studies of the historical records concerning the great carvel ship Peter von Danzig/Pierre de la Rochelle during the years 1462–75 (Mozejka, Citation2019). These close contacts across Europe concerned politics, economy, and personal relations ().

Figure 26. Ship carving from Sæby church, Denmark, depicting an early modern ship with a prominent carved bow figure. Could it possibly be Griffin that inspired the carving? (after Christensen, Citation1969).

Based on this, it is not surprising that we have the earliest records of carvel ships being built in northern Europe in this region. Between Rotterdam and Antwerp, near where the estuaries of the rivers Meuse and the Rhine merge and flow into the North Sea, on the island of Zierikezee, a sixteenth-century source claims that in 1459 the shipbuilder ‘Julien de Bretoen’ built the first carvel ship in the Netherlands (Sleeswijk, Citation1998, p. 223). The Danish Griffin could very well have been built in this yard, or a similar place nearby. Indeed, another source indicates that the new building method was already known in this area. In 1439, Philip of Burgundy, as Count of Flanders, gave an order to a Portuguese shipbuilder to build a nao and a carvel in Brussels. In connection with the wedding between his son, Charles the Bold of Burgundy and Margaret of York (sister of Edward IV) in 1468 in Bruges, the food was served on the first day of celebrations in 30 gilded scale models of carracks (Sleeswijk, Citation1990, p. 22, 26; cf. Mozejka, Citation2019, p. 15; see also ).

Large-scale Gifts

The fact that the middle of the fifteenth century seems to be a turning point for the construction of new carvels in northern Europe is also illustrated by the fact that England seemed unable to maintain or repair several Genoese carracks captured from the French in 1416–17. Carrack-shipwrights, -carpenters, and -caulkers were hired from as far afield as Venice, Portugal, and Catalonia to carry out the work (Friel, Citation1995, p. 174) and it was more than half a century before the English Crown committed to building in carvel (Adams, Citation2013, p. 70) and this was broadly contemporary with the building of Griffin.

Given its date of construction in the early 1480s, the wreck at St Ekön, like the slightly older Peter von Danzig (1462), is connected to this first generation of new Atlantic coast-built carracks/carvels that when they appeared in the North, inspired powerholders and shipbuilders on the Baltic Sea to start building similar ships themselves (on the spread of early carvels see Zwick, Citation2016).

We do not know how King Johńs ship came to Denmark. If Grifun/Gribshund is the same ship first mentioned as ‘navi nostra Griffone’ in 1486 when the king is in Norway, it must have been acquired relatively soon after it was completed on the Atlantic coast. Can it have simply been ordered here by John or his father? In 1476 Christian I visited Charles the Bold in Burgundy and stayed for several months, when he travelled home, he took the road passing through the Netherlands (Ullidtz, Citation2016, p. 535).

Large ships could also be given as gifts by the powerful to one another. As mentioned above, Christian I had good contacts with Edward IV and in 1468 he was given a ship by the English king. This is probably the same ship that is mentioned in 1471 as Christian's ship Valentin. In 1505, King John got the ship Snagelhavn from none other than his long-time opponent, the Swede Sten Sture. It certainly also would have been a substantial gift when in 1514 King John's son Christian II gave away his newly built great ship Engelen to his Queen Elisabeth's brother, the future Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V (Barfod, Citation1990, pp. 119, 131, 190).

The extent and interconnectedness of this early modern power network is also evident from the fact that this Danish queen was also the granddaughter of Ferdinand and Isabella in Spain who financed Christopher Columbus’ famous transatlantic voyage. Furthermore, Queen Elisabeth's sister was married to the French king, Frances I. From this brother-in-law, Christian II received six very precious bronze guns (at least one of which must have been captured by the Swedes as it was found on the wreck of Kraveln in the Stockholm archipelago, see Ankarberg, Citation2015).

Another way of acquiring ships was simply to take them by force, not only through interstate violence but piracy and privateering, something that seems to have been relatively common and which could lead to extensive negotiations as well as diplomatic and legal complications (Warming, in prep.). Typical of such incidents were the exploits of the two privateer captains Didrik Pining and Hans Pothors, sailing under Danish colours, who acted both on their own behalf as privateers and as agents of the Danish Crown under both Christian I and John I. Around 1484–85 they captured Portuguese ships and a Spanish ship that were taken to the towns of Stade and to Copenhagen. The Danish authorities could also sometimes just confiscate ships passing into the Baltic through the Sounds. The first recorded instance was in 1440 and it occurred on several subsequent occasions (Barfod, Citation1990, pp. 76–79, 197; Warming, in prep.).

Conclusion: Ships and Modernity

King John's Grifun/Gribshund is a uniquely preserved representative of the new type of carvel-built ships that the rulers of Europe began to build in the late Middle Ages – ships of a type related to those that Columbus and his successors used on their voyages to America and Vasco de Gama on his voyages to the Indian Ocean. Ships of this construction provided capacity, accommodation, and armament that enabled a new globalisation through exploration, colonisation, and exploitation. The looting and transportation of gold, spices, textiles, sugar, and many other goods across the oceans changed the world forever (Anderson, Citation1974; Monié Nordin, Citation2020; Wallerstein, Citation2011, for the Baltic and ships see Adams, Citation2013; Adams & Rönnby, Citation1996, Citation2013, Citation2019; Eriksson & Rönnby, Citation2017; Glete, Citation1976, Citation1977, Citation2000, Citation2002, Citation2010; Rönnby & Sjöblom, Citation2015).

What is notable about this process is how deeply rooted it was in events predating the iconic ‘discovery’ of the New World in 1492. An interesting circumstance in this context is that we know that there were direct contacts between Denmark and shipbuilding powerholders in the Iberian Peninsula already during the first half of the fifteenth century. In 1429 the Danish king, Erik, had a meeting with Henry the Navigator’s brother, Prince Don Pedro, where they probably exchanged geographic maritime knowledge. One of Henry the Navigator's captains on an expedition along the African west coast in 1448 seems also to have been Danish (Barfod, Citation1990, pp. 47–48).

Both Christian I, Dorothea, and John would also have had certain knowledge about the North Atlantic waters through maritime contacts with the old Nordic settlements on Greenland earlier in the Middle Ages. During the fifteenth century, however, the Greenlandic Norse population led an increasingly precarious existence. Poignantly, they were about to be forgotten in the Nordic countries and indeed they eventually died out (Møller Jensen, Citation2007, pp. 159–203).

But in 1476 Christian sent his captains Pothorst and Pining together with the Portuguese João Vaz Corte Real to Greenland and, depending on how one interprets the sources, perhaps further west to the ‘cod country’. That the area west of Greenland had acquired this name seems to imply it was a known region (Landström, Citation1964, p. 205; Møller Jensen, Citation2007, p. 185; Ullidtz, Citation2017). The ship they used for this early western travel was most certainly a modern carvel like Griffin (cf. early Basque whaling ships, Grenier et al., Citation2007). It is also interesting that Danish seaborne activity sometimes was also ideologically presented as part of a Western crusader mentality, connected to Christian rhetoric typical for this period (Møller Jensen, Citation2007).

The great importance of ships, and carvel ships in particular, is obvious in the transformational processes that bridged the medieval and modern worlds. And yet we have so little material surviving from that time. Certainly, we have the spectacular finds of Mary Rose (1510–45), Elefanten (1564) and Mars (1564) but these are developed forms of those first carvels built in northern Europe from the 1430s onwards, in very small numbers initially but in increasing quantity and size as their utility and versatility became recognised. Until recently that first, more tentative phase of building has only been knowable through a few ship models and depictions in the form of paintings and drawings. The Nämdöfjärden kravel (1525) is perhaps transitional in this process (Adams & Rönnby, Citation2013) but it is Grifun/Gribshund that to date is the key discovery, embodying a Mediterranean approach applied in a northern European context.

The investigations of the wreck outside Ronneby in the southern Baltic therefore provide a new maritime archaeological insight into the understanding of how these ships were constructed and what kind of work, knowledge, and resources were required to build and handle them. The objects and equipment on board also provide an insight into the world of objects and equipment with which a typical late medieval prince surrounded himself.

The development of new warships at the end of the Middle Ages also generally concerns an interesting theoretical question about the role of material culture in the development of society and the dialectical interaction between us and our things. Ideas have sometimes been put forward that claim a ‘symmetrical’ relationship between material culture and us humans with an emphasis on the things as agents. Ships like the ‘Danish Griffin’ were undoubtedly an important part of the modernisation process and one of the factors that contributed to the change of the world at the beginning of the New Age. However, our opinion is also that the roles material things have regarding social transformation must be understood in relation to prevailing power relations and the specific historical situation (see Adams & Rönnby, Citation2019).

Kings and new states were driving the development of ever larger and more powerful ships in the late Middle Ages, a process that would become even more noticeable during the sixteenth century. The new ships enabled wars and conquests, global shipping and exploitation to also serve as symbols of the new monarchic ambitions. Shipbuilding and the need for larger ships, better guns and entire fleets, in turn, required more resources and a new organisation in a kind of material and arms race spiral. All this has far-reaching consequences for the whole of society and the path towards modernity.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on fieldwork and research done on the wreck since 2013 but also summarises earlier studies in connection to the site. We gratefully acknowledge everyone who has been involved in the research of the wreck and contributed with different skills, expertise, information, and resources. For discussions and comment on the text we especially thank Kroum Batchvarov, Rodrigo Pacheco-Ruiz, Felix Pedrotti, Ingvar Sjöblom, and Rolf Warming. Thanks also to Jakob Bjerggaard who pointed us in the direction of the Sforza coat of arms.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Since 2013 the investigation of Grifun/Gribshund has had practical and financial support from The Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies, The Crafoord Foundation, Blekinge länsmuseum, MMT AB, Deep Sea Productions, Lund University, Södertörn University, and University of Southampton.

References

- Adams, J. (2013). A maritime archaeology of ships. Innovation and social change in medieval and early Modern Europe. Oxbow Books.

- Adams, J., & Black, J. (2004). From rescue to research. Medieval wrecks in St Peter Port, Guernsey. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 35(2), 230–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-9270.2004.00021.x

- Adams, J., & Rönnby, J. (1996). Furstens fartyg – marinarkeologiska undersökningar av en renässanskravell. Sjöhistoriska Museet/Stockholms länsstyrelse.

- Adams, J., & Rönnby, J. (2013). One of His Majestýs ‘beste kraffwells’: The wreck of an early carvel-built ship at franska stenarna, Sweden. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 42(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-9270.2012.00355.x

- Adams, J., & Rönnby, J. (2019). The consequences of new warships. Medieval to modern and our dialectical relation with things. In J. Rönnby (Ed.), On war on board. Archaeological and historical perspectives on early modern maritime violence and warfare (pp. 163–199). Academic Studies.

- Alm, J. (1933). Eldhandvapen I. Från deras tidigaste tillkomst till slaglåsets allmänna införande. Militärlitteraturföreningens förlag.

- Anderson, P. (1974). Lineages of the absolutist state. New Left Books.

- Ankarberg, C.-H. (2015). Två svenska “nationalmonument” – dekorerade med danske kungens vapen. Tidskrift i Sjöväsendet nr, 3, 289–300. https://www.koms.se/tidskrift/arkiv/nr-3-2015/

- Åkerlund, H. (1951). Fartygsfynden i den Forna Hamnen i Kalmar. Sjöhistoriska Samfundet.

- Barfod, J. H. (1990). Flådens fødsel. Marine historisk Selskab.

- Batchvarov, K. (2011). The black sea shipwreck from kitten and Mediterranean whole-moulding. In A. Catsambis, B. Ford, & D. L. Hamilton (Eds.), Oxford handbook of nautical archaeology (pp. 250–260). Oxford University Press.

- Bill, J. (2009). From Nordic to north European – application of multiple correspondence analysis in the study of changes in Danish shipbuilding A.D. 900–1600. In R. Bockius (Ed.), Between the seas. transfer and exchange in nautical archaeology. Proceedings of the eleventh international symposium on boat and ship archaeology (pp. 429–438). Mainz.

- Björk, M. (2016). Gribshunden. En studie av site formation process. Uppsala universitet. VT 2016. Kandidatuppsats i Arkeologi, 15 hp. Arkeologi och antik historia. Uppsala.

- Boetius, A. (2011). Ekövraket – en osteologisk proviantstudie baserad på djurben i ett senmedeltida vrak påträffat i Ronneby skärgård. Reports in Osteology 2011:3. Lund: Lunds universitet.

- Carlsson, G. (1955). Kalmar recess 1483. Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Christensen, A. E. (1969). Skibsristninger i Sæby kirke, Handels- og sjofartmuseet på Kronborg Årbog 1969: 82-100.

- De Meer, S. (2020). The nao of Mataró: A medieval ship model. Retrieved September 22, 2020, from https://www.iemed.org/dossiers-en/dossiers-iemed/accio-cultural/mediterraneum-1/documentacio/anau.pdf

- Dobbs, C. (2009a). The ballast. In P. Marsden (Ed.), Mary Rose your noblest ship. Anatomy of a Tudor warship. Archaeology of the Mary Rose II (pp. 119–123). Oxbow books/Mary Rose Trust.

- Dobbs, C. (2009b). The galley. In P. Marsden (Ed.), Mary Rose your noblest ship. Anatomy of a Tudor warship. Archaeology of the Mary Rose II (pp. 124–135). Oxbow books/Mary Rose Trust.

- Einarsson, L. (2008a). Ett skeppsvrak i Ronneby skärgård. In G. Jeppsson (Ed.), Ale, historisk tidskrift fr skåne, halland och Blekinge 2008. 2 (pp. 1–15). Historiska museet vid Lunds universitet.

- Einarsson, L. (2008b). “In navi nosta GRIFFONE”. Griffen i djupet. In Brunnsberg, K. (Ed.), Blekingeboken Årg 86 (pp. 22–49). Blekinge hembyggdförbund förlag.

- Einarsson, L. (2012). Rapport om hydroakustisk kartering och kompletterande dendrokronologisk provtagning och analys av vraket vid St. Ekö, Ronneby kommun, Blekinge län. Kalmar läns museum.

- Einarsson, L., & Gainsford, M. (2007). Rapport om 2006 års marinarkeologiska undersökningar av skeppsvraket vid St. Ekö. Saxemara, Ronneby kommun, Blekinge län. Kalmar läns museum.

- Einarsson, L., & Wallbom, B. (2001). Marinarkeologisk besiktning och provtagning för datering av ett fartygsvrak beläget i farvattnen syd saxemara, Ronneby kommun, Blekinge län. Rapport. UV/marinarkeologi 2001. Kalmar läns museum.

- Einarsson, L., & Wallbom, B. (2002). Fortsatta marinarkeologiska undersökningar av ett fartygsvrak beläget vid St. Ekö, Ronneby kommun, Blekinge län. Rapport Kalmar Läns Museum.

- Ellmer, D. (1994). The Cog as a cargo carrier. In R. J. Gardiner (Ed.), Cogs, Caravels and Galleons: The sailing ship 1000– (pp. 29–46). Conway Maritime Press.

- Eriksson, N. (2015). Skeppsarkeologisk analys. In J. Rönnby (Ed.), Gribshunden (1495): Skeppsvrak vid Stora Ekön, ronneby, Blekinge. Marinarkologiska undersökningar 2013–2015. Blekinge museum rapport 21 (pp. 13–32). Blekinge museum/Södertörns högskola.

- Eriksson, N. (2019). Gribshunden – det sista drakskeppet? Gränsløs, 10, 11–27. https://journals.lub.lu.se/grl/article/view/20334/18296

- Eriksson, N. (2020). Figureheads and symbolism between the medieval and the modern: The ship Griffin or gribshunden, one of the last sea serpents? The Mariner's Mirror, 106(3), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/00253359.2020.1778300

- Eriksson, N., Persson, T., Irskog, S., Rönnby, J., Sandekjear, M., & Sjöblom, I. (2019). Gribshunden 1495: Medeltidens modernaste skepp. Blekinge museum.

- Eriksson, N., & Rönnby, J. (2017). Mars (1564). The initial archaeological investigations of a great 16th century warship. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 46(1), 92–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/1095-9270.12210

- Friel, I. (1994). The carrack: The advent of the full rigged ship. In R. Gardiner, & R. Unger (Eds.), Cogs, Caravels and Galleons: The sailing ship 1000–1650, 77–90. Conway Maritime Press.

- Friel, I. (1995). The good ship: Ships, shipbuilding and technology in England 1200–1520. British Museum Press.

- Gardiner, R., & Unger, R. (1994). Cogs, caravels and galleons: The sailing ship 1000–1650. Conway Maritime Press.

- Glete, J. (1976). Svenska örlogsfartyg 1521–1560: Flottans uppbyggnad under ett tekniskt brytningsskede. [1]. Forum Navale, 30, 7–74.

- Glete, J. (1977). Svenska örlogsfartyg 1521–1560: Flottans uppbyggnad under ett tekniskt brytningsskede. [2]. Forum Navale, 31, 23–119.

- Glete, J. (2000). Warfare at sea. Maritime conflicts and the transformation of Europe. Routledge.

- Glete, J. (2002). War and the state in early modern Europe. Spain, the Dutch republic and Sweden as fiscal-miltary states, 1500–1660. Routledge.

- Glete, J. (2010). Swedish naval administration, 1521–1721: Resource flows and organisational capabilities. Brill.

- Grenier, R., Loewen, B., & Prouix, J.-P. (1994). Basque shipbuilding technology c. 1560–1580: The Red Bay project. In C. Westerdahl (Ed.), Crossroads in ancient shipbuilding (pp. 137–141). IBSA 6.

- Grenier, R., Stevens, W., & Bernier, M.-A. (2007). The underwater archaeology of Red Bay: Basque shipbuilding and whaling in the 16th century, Vol. III. Parks Canada.

- Guérot, M., & Rieth, E. (1998). The wreck of the Lomellina at villefranche sur Mer. In M. Bound (Ed.), Excavating ships of war, International Maritime Archaeology series 2 (pp. 38–50). University of Oxford.

- Guérout, M. (2002). Lomellina. In C. Ruppe, & J. Barstad (Eds.), International handbook of underwater archaeology (pp. 441–442). Springer.

- Guérout, M. (2020). Lomellina (1516). Retrieved September 26, 2020, from https://nadl.tamu.edu/index.php/shipwrecks/mediterranean-shipwrecks-2/western-mediterranean/lomelina-1615/ (The Nautical Archaeology Digital Library).

- Hallenberg, M., & Holm, J. (2016). Man ur huse. Hur krig, upplopp och förhandlingar påverkade svensk statsbildning i tidigmodern tid. Nordic Academic Press.

- Hedberg, J. (1975). Kungl. Artilleriet medeltid och äldre vasatid. Militärhistoriska.

- Jahnke, C. (2006). Dronningens skibe for kongens flåde. Dronning dorotheas af brandeburgs skibsbyggning omkring 1486. E. Göbel, & C. Lemée, (eds) Skibsbygge og Sofart i Renaessance. Maritim kontakt 28: 85–94.

- Jahrehorn, M. (2009). Föremål från ett medeltida skeppsvrak St. Ekö, Ronneby kommun. Konserveringsrapport. Kalmar läns museum.

- Kjellberg, S. T. (1964). Ölets käril. Kulturen. Årsbok 1964. Lund.

- Landström, B. (1964). Vägen till Indien. Upptäcksresor till lands och sjöss från expeditionen till Punt 1493 f- Kr till upptäckten av Godahoppsudden 1488 e. Kr. Forum.

- Larsson, L. J. (1964). Sören norbys skånska uppror. Scandia, Bind, 30(nr 2), s. 217–s. 271.

- Larsson, L. J. (1986). Sören Norby och Östersjöpolitiken 1523-1525. Lund. Univ.

- Lavér, R. (2017). I gapet på Gribshunden (1495). Skulpturer och deras bildspråk under medeltiden. Kandidatuppsats i arkeologi. Stockholms universitet.