ABSTRACT

Many assume that if citizens were more inclined to moralize the values of evidence-based and logical thinking, they would be less likely to share politically hostile, conspiratorial, and false claims on social media. In contrast, on the basis of theories of status seeking and persuasion, we argue that moralization of rationality may actually stimulate the spread of hostile partisan news online, including fabricated claims. Across three large surveys (N = 4800) run on U.S. respondents (one exploratory and two pre-registered), we provide empirical evidence for this prediction and demonstrate that the moralization of rationality can be a form of moral grandstanding by status seekers inclined to spread hostile (mis)information to reach partisan goals. In contrast to such grandstanding with respect to rationality, our studies find robust evidence that intellectual humility – that is, the awareness that intuitions are fallible and that trusting others is often desirable – may protect people from both sharing and believing hostile and false political news online.

In recent years, there have been growing concerns in the U.S. and other Western countries about the spread of news and posts that combine political denigration and low-quality evidence, such as ungrounded conspiracy theories or fabricated attacks on out-party leaders and voters (Petersen et al., Citation2023; Vosoughi et al., Citation2018). Even though several studies have found that few people knowingly share misinformation (Altay, Hacquin, et al., Citation2020; Grinberg et al., Citation2019; Littrell et al., Citation2023; Osmundsen et al., Citation2021) and that they are mainly circulated in ideologically homogenous networks on social media (Marie et al., Citation2023; Osmundsen et al., Citation2021), hostile and false claims can pose a threat to social trust and cohesion. By portraying out-party voters and elites as excessively stupid or evil, and by covering complex issues in simplistic ways, hostile (mis)information can exaggerate ideological and affective polarization between liberals and conservatives (Finkel et al., Citation2020), “anti-system” sentiments (Uscinski et al., Citation2021), and distrust toward journalists and beneficial technologies such as vaccines against COVID-19 (Jensen et al., Citation2021). Moreover, even when hostile and conspiratorial claims do not directly persuade individuals to change their behavior, they can still contribute to rationalize already existing distrust in the establishment and motivations to take part in political violence (Horowitz, Citation2020; Littrell et al., Citation2023; Marie & Petersen, Citation2022; Mercier, Citation2017; Mercier & Altay, Citation2022; Petersen, Citation2020a).

Political scientists and psychologists have pinned down numerous processes potentially facilitating adherence to and diffusion of hostile and false partisan claims online and in real life. Some reflect individual-level cognitive biases, such as negative intent ascriptions, hyper-sensitive threat detection, or simplistic storytelling (Gottschall, Citation2021; Lees & Cikara, Citation2020; Rozin & Royzman, Citation2001; van Prooijen & van Vugt, Citation2018). Other risk factors are social and institutional in nature. They include feelings of low or declining status among demographic groups (Obradović et al., Citation2020; Petersen et al., Citation2023), interference by rogue foreign powers (Simchon et al., Citation2020), lack of democratic accountability and politicians’ misconduct (Alper, Citation2021), and social media platforms not incentivizing people to think enough about content veracity (Pennycook et al., Citation2021).

In the academic literature, there is broad consensus that if citizens had stronger motivations to pursue the truth and take the facts into account, the quality of public opinion and political conversations would improve (Iyengar et al., Citation2019; Osmundsen et al., Citation2021; Pinker, Citation2018). For instance, this idea is a fundamental premise of the debate in political psychology about the extent to which politically motivated thinking can dominate accuracy motivations and lead to biased political beliefs (Kunda, Citation1990; Slothuus & de Vreese, Citation2010; Tappin et al., Citation2020). The notion that stronger accuracy motivations will make political communication and beliefs more accurate is also embedded in recent efforts to develop intervention messages aiming to prompt social media users to focus more on the accuracy of the news they share (e.g., Pennycook et al., Citation2021; Marie et al., Citation2023).

One interesting variant of this argument is that the diffusion of misleading and divisive information may be facilitated by citizens failing to regard reason, evidence, logic, and critical thinking as moral virtues. Rationalist philosophers and intellectuals since at least Socrates have argued that cultivating personal ethics of impartial search for truth and reliance on the best arguments and evidence could only help citizens make wiser decisions in political affairs (e.g., Cooper & Hutchinson, Citation1997; Habermas, Citation1984). In rationalist philosophical discourse, an unwillingness to base one’s beliefs on the evidence and yield to the best arguments are often portrayed as socially dangerous (e.g., susceptibility to demagogues, superstition), and thus as immoral, at least implicitly. By contrast, it is those individuals who do strive to embody the values of epistemic rationality (typically, the philosophers) who are conferred highest social status.Footnote1 Recently, inspired by this old idea, social psychologists Ståhl et al. (Citation2016) found that people who view the formation of one’s beliefs through logic and evidence as a moral virtue are more likely to donate money to fight against the spread of “pseudoscience, superstition, and other kinds of irrational beliefs” (their Study 8). Public intellectuals such as Sam Harris (e.g., Harris, Citation2013-present) or Steven Pinker (Pinker, Citation2018, Citation2019) often speak of statistical education and logical thinking as intellectual dispositions that citizens ought to cultivate to avoid social costs. Pinker puts it in this way in an interview in The Harvard Gazette: “We need to make ‘factfulness’ [i.e., a close reliance on the best available evidence] an inherent part of the culture of education, journalism, commentary, and politics. An awareness of the infirmity of unaided human intuition should be part of the conventional wisdom of every educated person. Guiding policy or activism by conspicuous events, without reference to data, should come to be seen as risible as guiding them by omens, dreams, or whether Jupiter is rising in Sagittarius” (Pinker, Citation2019).

With a populace educated to positively moralize forming beliefs through careful examination of the facts and methodic thinking – so this optimistic rationalist perspective goes – political opinion and conversations would become more fact-based, less biased, and less driven by emotion. As a result, conspiracy theories, fake news and pseudoscience would enjoy less cultural success, and our ability to tolerate different political viewpoints would increase.

In this manuscript, we challenge this optimistic rationalist hypothesis. Previous research has shown that individuals with strong status-seeking orientations are more likely to engage in political hostility, in particular, by sharing hostile and false partisan news attacking their opponents (Bor & Petersen, Citation2022; Osmundsen et al., Citation2021; Petersen et al., Citation2023). In this respect, theories of persuasion suggest that status-oriented individuals might be inclined to moralize epistemic rationality – that is, to see the grounding of one’s beliefs in evidence and logic as a moral virtue (Ståhl et al., Citation2016) – as a way of making their partisan opinions and debate tactics appear as more justified and laudable (Grubbs et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Nietzsche, Citation1998; Tosi & Warmke, Citation2016). In other words, we suspect that moralizing rationality may constitute a form of moral grandstanding in the sense that status-seeking partisans may try to persuade themselves and others that their political strategies – such as trying to discredit political opponents and rallying others to their political positions – are accomplished in the name of universal and unobjectionable epistemic values.

Prima facie evidence supporting this hypothesis is that many political activists who disseminate hostile and conspiratorial information claim to be motivated by reason, research, the truth, the facts, critical thinking, and so on. That is, they invoke precisely those epistemic virtues that should make them less likely to spread hostile and false political claims according to the optimistic rationalist narrative. As ethnographers recently observed, Dutch “conspiracy theorists appropriate the image of the radical freethinker to differentiate themselves from the ‘sheeple’ who simply follow the crowd. […] Our respondents collectively use the pejorative mainstream label of ‘conspiracy theorists’ to distance themselves from the ‘really’ irrational ones in the conspiracy milieu. ‘I am not a conspiracy theorist’ is the collectively shared adage to emphasize one’s own superiority/rationality” (Harambam & Aupers, Citation2017, p. 6). Other psychologists and philosophers similarly emphasize how conspiracy theorists, contrary to popular images, often strive to be evidence-oriented (Dentith, Citation2019) and rational (Coady, Citation2007).

Below, we unpack psychological arguments and evidence suggesting that status seekers might be drawn toward sharing hostile, including false, partisan claims in politically polarized contexts. We also explain why they might be motivated to cast themselves as being on the side of impartial virtues of truth and rationality. We then present three studies run in the U.S. corroborating those hypotheses.

Status Seeking in Politics and the Sharing of Claims Hostile to Political Opponents

Many people are incentivized to improve their place in the social hierarchy, defined as one’s influence on the allocation of resources and group decisions (Anderson et al., Citation2015; Brown, Citation1991; Cheng et al., Citation2013; Sapolsky, Citation2005; von Rueden et al., Citation2011). Politics is a key domain toward which individuals concerned with status acquisition should be expected to gravitate (Bor & Petersen, Citation2022). It is through the constitution of political groups that the rules of the social game – such as the laws and norms regulating the distribution of resources and power between social groups – can be changed.

Political discussions, for instance, on social media, involve the public exchange of ideas about social issues to be solved and what the proper order of society should be. They are a privileged place to recruit for one’s side, discredit opponents, and display desirable values, such as how good at debating, informed, or devoted to moral causes one is. Accordingly, a wealth of empirical research confirms that status-oriented individuals are driven toward politics. For instance, status seeking is a key predictor of participation in online discussions and online hostility (Bail, Citation2022; Bor & Petersen, Citation2022; Buckels et al., Citation2014) and of participation in violent activism in Western and African countries (Bartusevičius et al., Citation2020), including jihadism (Kruglanski et al., Citation2014).

As part of this arsenal of political activism, the sharing of claims and posts that are hostile to one’s political rivals – including false claims – may be attractive to individuals seeking to acquire status and advance their interests in political conflict. Conspiracy theories and ethnic rumors demonizing enemy groups thrive in circumstances of ethnic tensions and warfare (Horowitz, Citation2020; Uscinski, Citation2020; Uscinski & Parent, Citation2014). Animosity toward out-partisans is also the primary driver of false news sharing on a U.S. Twitter rife with affective polarization between Democrats and Republicans (Osmundsen et al., Citation2021). Political cynicism and motivations to subvert the entire political order (not just out-party elites) predict the circulation of conspiracy theories hostile to both out-party and in-party leaders (Osmundsen et al., Citation2021; Petersen et al., Citation2023).

Those associations reflect that claims and content depicting outgroup members as malevolent or incompetent can be viewed as useful material for partisans’ goals on social media. For instance, sharing news derogating or bullying political opponents (e.g., anti-Biden fake news from Republicans’ perspective) may be believed to persuade audiences to mobilize against outgroup elites or the establishment in general (Marie & Petersen, Citation2022; Petersen et al., Citation2023; Pinsof et al., Citation2023). Rumors demonizing the outgroup can also help reputational enhancement: signaling to potential political allies who one sees as one’s rivals (Iyengar et al., Citation2012, Citation2018), a personal motivation to aggress against the outgroup (Laustsen & Petersen, Citation2017; Mercier & Altay, Citation2022; Petersen & Laustsen, Citation2020b) or a dominant personality (de Araujo et al., Citation2020), which followers look for in times of conflict. Propagating claims attacking political opponents online (in particular, among like-minded or neutral networks) may thus be seen by partisans as useful for facilitating mobilizations and status acquisition in conflict-ridden contexts (regardless of whether doing this effectively helps them reach those goals).

Incidentally, strategies aiming to undermine support for one’s opponents may sometimes be best served by claims that, within limits of plausibility, invent or exaggerate the misdemeanors they accuse opponents of having perpetrated, because fictitious actions can be made juicier than those occurring in reality (Horowitz, Citation2020; Marie & Petersen, Citation2022; Petersen, Citation2020; Petersen, Osmundsen, & Tooby, Citation2020). Note that this strategic advantage of information being factually false (or misleading) would be the same irrespective of whether social media users believe the claims to be true or diffuse them with the intention to disinform and deceive (Littrell et al., Citation2023).

Willingness to Attack Political Opponents May Be Facilitated by Convictions to Be on the Side of Truth

While partisans and status seekers may see hostile political posts as useful for their goals, those goals may be better reached if the hostility appears warranted by universal virtues rather than the pursuit of self-interest. Audiences are inclined to trust and side with individuals who appear motivated by prosocial and disinterested goals such as universal moral values (Everett et al., Citation2016; Petersen, Citation2013; Singh & Hoffman, Citation2021; Tooby & Cosmides, Citation2010). This is because universal principles propose to protect the interests of everyone impartially, regardless of one’s position in a situation, and are perceived as transcending individual self-interest (Skitka, Citation2010; Stanford, Citation2018). As a result, agents who sincerely profess to follow universal principles pass as being more trustworthy – even in cases where they are also motivated, perhaps unconsciously, by strategic social goals (Schwardmann & van der Weele, Citation2019; Singh & Hoffman, Citation2021, Citation2021; Sperber & Baumard, Citation2012; von Hippel & Trivers, Citation2011). In this respect, there is prior evidence that the vocal expression of moral and political claims in public discussions is often driven by (unconscious) attempts to dominate opponents, gain prestige, and mobilize followers – tactics that Grubbs et al. (Citation2019) have called moral grandstanding.

In this paper, we suggest that moralizing rationality may be a form of moral grandstanding. Namely, that status-seeking partisans motivated to spread rumors intended to hurt political opponents, mobilize followers against them, and signal allegiances may try to broadcast their hostility and partisan motives as warranted by universal virtues of truth-seeking and rationality (DeScioli et al., Citation2014; Grubbs et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Petersen, Citation2020; Singh & Hoffman, Citation2021; Tosi & Warmke, Citation2016; Weeden & Kurzban, Citation2014). In other words, we suspect that moralizing rationality may operate as a rationalization of strategic motives deployed in political conflict – shaming of opponents, recruitment of allies, signaling for status, etc. – intended to make the strategies appear motivated by impartial epistemic virtues of truth-seeking and rationality. Conversely, people who are not motivated to engage in rough discussions about politics and gain status may feel less of a need to present themselves as moral arbiters of the truth.

Contra the optimistic rationalistic narrative mentioned above that moralizing rationality should protect people against hostile (mis)information, we thus made two preregistered hypotheses. First, we predict that moralizing rationality would be associated with greater willingness to share true and false news hostile to one’s political outgroup (H1). We focus our predictions on news targeting the outgroup (rather than the ingroup) because status seekers who engage in political hostility generally identify with one group or party more than the other(s), as opposed to targeting every political group indiscriminately. Second, we predict the relationship H1 between moralizing rationality and sharing of news attacking the outgroup to be largely explained by status seeking (H2). (Note that we do not claim that all cases of moralization of rationality are grounded in status seeking. Some individuals low in self-assertion or partisan motivations but with strong willingness to pursue the truth might moralize rationality highly as well.)

Intellectual Humility As a Protection Against Hostile and False Claims

If moralizing rationality should typically not be expected to make people less susceptible to share politically hostile and false claims, then what might? Drawing on empirical findings on the illusion of expertise on politics (Fernbach et al., Citation2013, Citation2019; Rozenblit & Keil, Citation2002), status acquisition (Cheng et al., Citation2013), and philosophical theories of expertise (Popper, Citation2019; Tetlock & Gardner, Citation2016; Whitcomb et al., Citation2017), we contend that what may be key is intellectual humility (preregistered H3). That is, dispositions to reflectively acknowledge one’s ignorance and take others’ judgment into account (on complex political topics in particular) may reduce susceptibility to hostile political (mis)information (Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, Citation2016; Porter et al., Citation2022; Whitcomb et al., Citation2017). One possible mechanism is that intellectual humility may operate as a psychological counterweight to the assertiveness and need for recognition which are prominent among status seekers, making it a better antidote to aggressive inclinations than the moralization of rationality. Furthermore, intellectual humility, as a disposition to question one’s intuitions and to be open to others’ perspectives, may make it easier to inhibit cognitive biases (such as negative intent ascriptions, monocausal explanations, dualism or Manicheism, etc.), which are signature features of hostile and conspiratorial political discourses (e.g., Marchlewska et al., Citation2018). Hence, we made the preregistered prediction that more intellectually humble people would be less susceptible to share true and false news hostile to their political outgroup (H3).

Studies Overview

The three studies presented below primarily aimed to test preregistered hypotheses about sharing both true and false news hostile to respondents’ political outgroup (e.g., Democrats for Republicans and vice versa). Some of the hostile news presented completely fabricated claims (false news), while others reported events that actually took place (true news). We predicted a positive association between moralization of rationality and motivations to share news hostile to the outgroup (H1) and that this association would be largely explained by status-seeking variables, as operationalized by moral grandstanding and status-driven risk taking (H2). By contrast, we predicted intellectual humility (H3) to negatively predict sharing of news hostile to the outgroup.

Study 1 was exploratory. The design, hypotheses, and analyses of Studies 2 and 3 were fully preregistered. All were run on US partisan participants (total N = 4800) in the fall of 2021 and January 2024. While the primary outcome we set out to explore in the preregistrations was intentions to share true and false news stories hostile to the outgroup, we also examined intentions to share news hostile to the ingroup and true neutral news for comparison. Importantly, our hypotheses H1-H3 are non-committal as to whether participants would share hostile false news because they believe them to be accurate, neglect gauging their plausibility (Pennycook et al., Citation2021), know them to be false but do not care, or share them because they know them to be falsehoods (Littrell et al., Citation2023). Finally, while our preregistered hypotheses were about intentions to share the news, examined in Studies 1–3, Study 2 also examined the associations between moralization of rationality, status seeking, and intellectual humility and belief in the news.

Why integrate moralized rationality, status seeking, and intellectual humility (on which more details are given below) into the battery of covariates already studied by political scientists, political psychologists, and communication scholars? Parsimony in the cognitive processes and traits that researchers postulate is desirable (Oeberst & Imhoff, Citation2023), but it is in tension with explanatory adequacy (Graham et al., Citation2012). Generally speaking, to the extent that the above personality dimensions are able to predict increased and decreased dissemination of divisive and false claims – and our results below show they all do – they matter for discussions about politically motivated thinking (Jerit & Kam, Citation2023; Kunda, Citation1990; Prior et al., Citation2015), the spread of polarizing talk and misinformation on social media (Altay, de Araujo, et al., Citation2020; de Araujo et al., Citation2020; Marie & Petersen, Citation2022; Marie et al., Citation2023; Osmundsen et al., Citation2021; Pennycook et al., Citation2021; Petersen, Citation2020), and citizens’ competence at understanding policy issues (Converse, Citation2006; Fernbach et al., Citation2013).

More specifically, moralized rationality (Ståhl et al., Citation2016) measures a moralistic motivation to think rationally and to morally condemn those who do not, and moral grandstanding (Grubbs et al., Citation2019) and status-driven risk taking (Ashton et al., Citation2010) capture inclinations to dominate others through moral talk and seek status in risky ways, respectively. Conceptually, both independent variables appear orthogonal to standard variables in political communication research such as the need to find simple, definitive answers or explanations to problems and phenomena, captured by the need for cognition and the need for closure. Our data confirm this, with weak correlations between moralized rationality and need for cognition (Study 1: r = 0.06, p = .057; Study 3: r = 0.07, p = .028) and need for closure (Study 3: r = 0.24, p < .001). See SM, F-H.

Finally, the self-report scale of intellectual humility (Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, Citation2016) shares some overlap with the frequently used cognitive reflection test: a measurement of abilities to override intuition. However, at least two key features differentiate intellectual humility: its tapping respect for others’ viewpoints and an ability to separate intellect from ego, which are crucial intellectual virtues for reasoning and talking with accuracy about political topics, absent from cognitive reflection (a problem-solving task). Accordingly, in our data, intellectual humility is only weakly correlated with cognitive reflection (Study 2: r = 0.1, p = .001; Study 3: r = 0.09, p = .002).

More information about the associations between the personality variables contained in Studies 1–3 can be found in SM, F-H, under headers “Relationships between personality covariates.”

Method

Preregistrations

Study 1 relied on data that was collected for another project to provide initial exploratory tests of our hypotheses H1-H3 regarding news sharing. As part of the other project, the design, materials, and sample size of Study 1 were pre-registered on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/haq72/?view_only=30193f0ecf854a6ab7d30b539dc9f8e7.

Studies 2 and 3 were enhanced replications of Study 1. Their design, materials, and sample sizes were pre-registered at https://osf.io/dfm6y/?view_only=2de940a2d16747f4b9541320d35e7e4d (Study 2) and https://osf.io/ywrsg/?view_only=b047c3e3ddb9463cb70ebe9aa964c8c1 (Study 3), together with our key hypotheses H1-H3 and the statistical analyses required to test them.

Participants

For Study 1, a pre-registered, a priori power analysis in GPower estimated that 1,000 participants were needed to detect a small effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.2 at 90% power (alpha level = 5%). We recruited N = 1,104 partisan participants (Mage = 45, SDage = 15.7, 49% women) in September 2021. In contrast to Study 1, Study 2 had two conditions: sharing vs. belief in the news stories. To maintain statistical power, we decided to more than double the sample size of Study 1 for Study 2. This led us to recruit N = 2,571 partisan participants (Mage = 40, SDage = 15, 55% women) in November 2021. Those two Prolific samples were representative of the U.S. national population on age, sex, and ethnicity in Study 1 and close to representativeness along those dimensions in Study 2. To preserve cognitive diversity of respondents, no attention filter was applied in Studies 1–2. Finally, Study 3 aimed to replicate our main pre-registered effects on news sharing on a nationally representative quota sample of the U.S. population provided by the firm YouGov. Study 3, as Study 1, only explored sharing intentions and consequently used a similar final sample size, N = 1125 (Mage = 52.4, SDage = 18, 46.4% women), collected in January 2024. Because of their more nationally representative nature, YouGov panels may be less attentive than Prolific respondents, so two preregistered attention filters were applied in Study 3 (excluding 160 inattentive respondents from the 1285 originally recruited; see SM, section D). Because our project is first and foremost an investigation of how partisans use news online, the three samples included only people identifying as either Democrat or Republican partisans (i.e., no Independents).

Designs

Participants had to give their informed consent to participate in all studies and were paid $2 for their time in Studies 1–2. The first part of the surveys requested them to fill in batches of political attitudes and personality questions, which constitute our key independent variables. The batches and the items they contain were presented in a random order. Afterward, the second part of the studies exposed participants to a range of news items in a random order. While Studies 1 and 3 only probed participants on their willingness to share the news, Study 2 randomly asked them to report either their willingness to share or how accurate they perceived each item to be (to capture belief). The surveys ended with demographic questions: sex, age, and level of education, used as control variables.

Measures

All our measures are detailed in SM, section D.

Outcomes

Studies 1,Footnote2 2 and 3 probed participants on their willingness to share each news item on social media on an [0] Extremely unlikely to [5] Extremely likely scale. To capture belief, Study 2 asked a random half of the participants to report how accurate, to the best of their knowledge, they perceived each item as being on an [0] Extremely inaccurate to [5] Extremely accurate scale.

Covariates

To test hypothesis H1, stipulating a positive association between moralized rationality and news sharing, we relied on the “moralized rationality” scale (9 items, Ståhl et al., Citation2016) (Studies 1–3). It contains items such as the following: “It is a moral imperative that people can justify their beliefs using rational arguments and evidence” and “Holding on to beliefs when there is substantial evidence against them is immoral.”

To test H2 about the role of status-seeking motivations in moralizing rationality, we relied in all three studies on two indexes. First, we used a scale of moral grandstanding (10 items, Grubbs et al., Citation2019), which captures the “use of public moral discourse for self-promotion and status attainment” (Grubbs et al., Citation2019), i.e., tendencies to elevate oneself above others through the heralding of moral beliefs (e.g., “I share my moral/political beliefs to make people who disagree with me feel bad”). Second, we used a scale of status-driven risk taking (14 items, Ashton et al., Citation2010), which taps inclinations “to seek and accept great risks … in pursuit of great rewards involving material wealth or social standing” (Ashton et al., Citation2010) (e.g., “I would enjoy being a famous and powerful person, even if it meant a high risk of assassination”). Status-driven risk taking also captures individual differences in risk taking, but both status-driven risk taking and moral grandstanding are established measures of status seeking (Ashton et al., Citation2010; Grubbs et al., Citation2020; Petersen et al., Citation2023).

To test hypothesis H3 of a negative association between intellectual humility and hostile news sharing, we employed a self-report scale of intellectual humility (22 items, Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, Citation2016) in Studies 2 and 3. This scale was designed to tap intellectual humility in the broad sense of being reflectively disposed to override intuition, to separate one’s beliefs from one’s self-worth, and to take others’ judgment into account – skills that are central to the pursuit of truth and to normative definitions of epistemic rationality (Fernbach et al., Citation2013; Popper, Citation2019; Porter et al., Citation2022; Tetlock & Gardner, Citation2016; Whitcomb et al., Citation2017). The scale contains items such as the following: “I am willing to change my position on an important issue in the face of good reasons” and “I am willing to hear others out, even if I disagree with them.”

Finally, to gain a better understanding of the relationship between moralized rationality and classic covariates in political psychology and communication research, our studies also included the following measures, presented before viewing the news: partisanship (Studies 1–3); outgroup animosity based on feelings thermometers (Studies 1–3; Osmundsen et al., Citation2021); need for cognition (Studies 1, 3; Lins de Holanda Coelho et al., Citation2020); need for closure (Study 3; Roets & Van Hiel, Citation2007); and the cognitive reflection test, captured with the non-mathematical CRT-2 (Studies 1–3; Thomson & M Oppenheimer, Citation2016). See SM, D for the items contained in those scales.

Stimuli

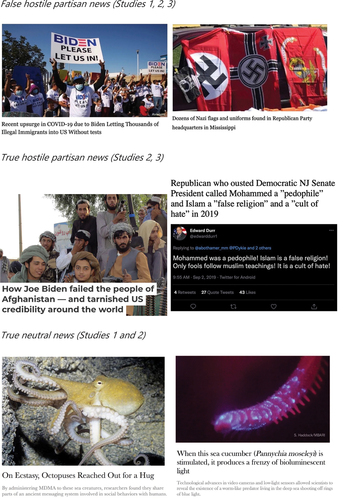

To obtain our key dependent measures of sharing of (Studies 1–3) and belief in (Study 2) the news stories, participants were randomly exposed to a number of news items after the attitude and personality questions. Each story was composed of a headline and a picture, and no source was displayed to focus attention on the headlines. Respondents saw 10 news stories in Study 1: four false stories hostile to Democrats, four false stories hostile to Republicans, and two true neutral stories. In Study 2, the set of news stories of Study 1 was supplemented with four true stories hostile to Democrats and four true stories hostile to Republicans, leading to 18 items in total. Study 3 comprised both true and false stories, but to compensate for a larger number of personality scales, we retained three true stories hostile to Democrats, three true stories hostile to Republicans, three false stories hostile to Democrats, three false stories hostile to Republicans, and no neutral stories, so 12 items in total. All participants saw all the items contained in a given study.

All news items were tested for perceived hostility in two pretest studies run on Prolific in August (false news) and November (true news) 2021. The study that pretested the false hostile news contained a total of 18 candidate items (12 hostile and 4 neutral), and the one that pretested the true hostile news contained 22 candidate items (all hostile; some were borrowed from Pennycook et al., Citation2021). To be selected for the pretesting study, the candidate hostile news had to meet the following requirements. First, they all had to express overt hostility to Democrats or Republicans in the sense of ascribing malevolence or incompetence to politicians or voters from one of the two groups. Second, the false hostile news had to report on events that did not take place (which we often invented, inspired from false news circulating online). By contrast, the true hostile news had to report on events that actually took place, in the sense of having been reported by reliable media sources such as the New York Times or The Guardian. As to the true neutral news, they accurately reported on animal biology and were retrieved from https://www.nature.com/. In order to focus attention on the claims, sources were never visible.

The pretest studies asked the raters two questions about each news story: “To what extent does this news headline reflect negatively on supporters of the Democratic party?” and “To what extent does this news headline reflect negatively on supporters of the Republican party?” (from [0] Not at all to [100] Extremely with [0] as default slider position). The hostility of a news item was determined as the average of three metrics of hostility: an absolute score (e.g., hostility of item X to Democrats), a difference (hostility of item X to Democrats – hostility of item X to Republicans), and a ratio (hostility of item X to Democrats/hostility of item X to Republicans). The items we retained for our studies were the four false and four true news stories that were perceived as being most hostile to Democrats, the four false and four true news items perceived as being most hostile to Republicans, and the two least hostile true neutral news items. See for examples of news stories. Refer to Supplementary Materials (SM: https://osf.io/u5bc3/?view_only=f35580570b82414ab4e9f77580325cf9), sections A-C, for the full set of items used in the studies.

Statistical Analyses

All data analyses in this paper were run in R using R Studio. Data and code are available on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/udj6t/?view_only=6c35259a0d0f4f3b95ee2d75fffd639c. The analyses we preregistered in Studies 1–2 were based on linear mixed-effects models. However, we encountered convergence issues related to our demographic control variables. All effects from all studies reported here are consequently based on the similar analysis strategy of regression models of intentions to share and belief with robust standard errors clustered around participant ID. This latter data fitting approach is also the one favored in leading work on misinformation consumption (e.g., Pennycook et al., Citation2021).

Models that explore relationships between personality covariates and sharing or belief in the news items include one covariate at a time (e.g., moralized rationality). Models that report relationships between two personality covariates are estimated based on the full dataset of each study. All models control for sex, age, and education. All coefficients are standardized (based on scaling of independent and dependent variables), and 95% confidence intervals are specified in square brackets.

Our primary pre-registered hypotheses H1-H3 and the corresponding analyses focus on the associations of moralized rationality, status seeking, and intellectual humility with intentions to share true and false news hostile to participants’ outgroup. However, a comprehensive account of the influences of our personality covariates on news sharing also required examining how they affect sharing of true and false news hostile to a participant’s ingroup, and true neutral news, for comparison. Doing this would allow us to disentangle a potential taste for hostile claims in general from partisan motivations specifically and news sharing in general. We thus systematically report the association of each personality covariate of interest (e.g., moralized rationality) with news sharing in the following order: associations of moralized rationality with sharing of false and then true news hostile to the outgroup, with false and then true news hostile to the ingroup, and with true neutral news, before reporting the personality covariate x hostility target interaction for false and then true news (with hostility to the outgroup defined as baseline of the hostility target factor). We then proceed in the same order when reporting the associations between our covariates and belief in the false and true news.

Results

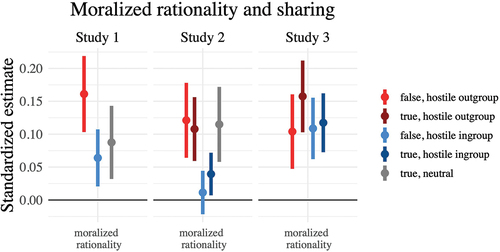

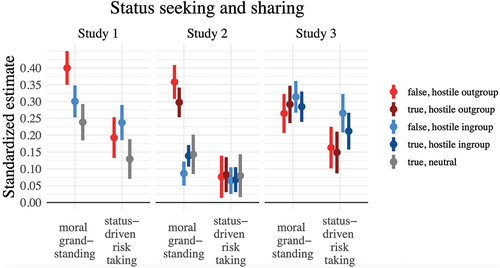

Main results are graphically displayed in . Regression tables for our pre-registered and exploratory analyses can be found in SM (https://osf.io/u5bc3/?view_only=f35580570b82414ab4e9f77580325cf9), sections F-H.

Figure 2. Associations between moralized rationality and willingness to share each news type in Studies 1, 2 and 3. Regression coefficients denote the standardized regression coefficient of each personality covariate on the dependent variable with robust SEs clustered around participant ID while controlling for age, sex, and education. Whiskers are 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3. Associations between status seeking (status-driven risk taking and the moral grandstanding scale) and willingness to share each news type in Studies 1, 2, 3. Regression coefficients denote the standardized regression coefficient of each personality covariate on the dependent variable with robust SEs clustered around participant ID while controlling for age, sex, and education. Whiskers are 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4. Associations between status seeking (the moral grandstanding index and status-driven risk taking) and moralized rationality in Studies 1, 2, 3. Regression coefficients denote the standardized regression coefficient of each personality covariate on the dependent variable with robust SEs clustered around participant ID while controlling for age, sex, and education. Whiskers are 95% confidence intervals.

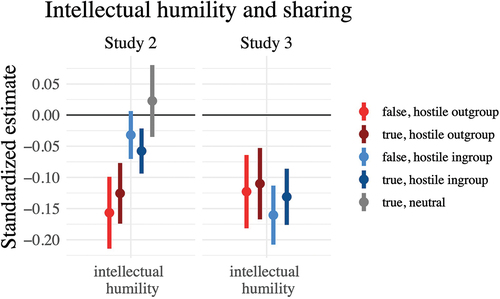

Figure 5. Associations between intellectual humility and willingness to share each news type in Study 2 and 3 (the scale was absent from Study 1). Regression coefficients denote the standardized regression coefficient of each personality covariate on the dependent variable with robust SEs clustered around participant ID while controlling for age, sex, and education. Whiskers are 95% confidence intervals.

Willingness to Share the News Stories

Testing H1: Moralized rationality and sharing

Is there a positive relationship between moralizing rationality and sharing of news hostile to the outgroup (pre-registered H1)? Yes. As shown in , the more participants claimed to moralize rationality, the more likely they were to pass along news stories hostile to the political outgroup, both false (Study 1: ß = 0.16 [0.10, 0.22], p < .001; Study 2: ß = 0.12 [0.06, 0.18], p < .001; Study 3: ß = 0.10 [0.05,0.16], p < .001) and true (Study 2: ß = 0.11 [0.06, 0.16], p < .001; Study 3: ß = 0.16 [0.10,0.21], p < .001). This provides support for H1.

By contrast, the positive association between moralizing rationality and intentions to share false news hostile to one’s ingroup was weaker, yet significant in Study 1 (ß = 0.06 [0.02,0.11], p < 0.004) and Study 3 (ß = 0.11 [0.06,0.16], p < 0.001), but no effect emerged in Study 2 (ß = 0.01 [−0.02,0.04], p = .4). Moralizing rationality was also associated with slightly more sharing of true news hostile to one’s ingroup (Study 2: ß = 0.04 [0.01,0.07], p < 0.017; Study 3: ß = 0.12 [0.07,0.16], p < 0.001).

In summary, moralizing rationality tended to have a stronger association with sharing of false news hostile to the outgroup than hostile to the ingroup in Studies 1 and 2 (moralized rationality x hostility target: Study 1: ß = − 0.07 [−0.12, −0.02], p = .008; Study 2: ß = − 0.09 [−0.14, −0.04], p < .001), but no difference was found in Study 3 (ß = 0.05 [0.00,0.10], p = .054). As regards true hostile news, moralizing rationality tended to more strongly predict sharing of true news hostile to the outgroup than hostile to the ingroup in Study 2 (moralized rationality x hostility target: ß = −0.06 [−0.10, −0.02], p = .001), but no difference was found in Study 3 (ß = 0.02 [−0.03, 0.06], p = .518).

Finally, moralizing rationality also predicted more sharing of true neutral news (Study 1: ß = 0.09 [0.03,0.14], p < 0.002; Study 2: ß = 0.11 [0.06, 0.17], p < 0.001).

Testing H2: Relationships Between Moralized Rationality, Status Seeking, and sharing

Is the relationship between moralizing rationality and sharing of news hostile to participants’ outgroup underpinned by status-seeking tendencies (pre-registered H2)? Overall, H2 is widely supported. First, we examine the relationship between hostile news sharing and our indexes of status seeking. As shown in , status-seeking tendencies strongly predicted sharing of false news hostile to the outgroup in Study 1 (moral grandstanding: ß = 0.40 [0.35, 0.45], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.19 [0.13, 0.25], p < .001). In Study 2, status-seeking tendencies also positively predicted sharing of hostile news hostile to the outgroup, both false (moral grandstanding: ß = 0.36 [0.31, 0.41], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.08 [0.01, 0.14], p = .017) and true (moral grandstanding: ß = 0.30 [0.25, 0.34], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.08 [0.03, 0.13], p = .002).Footnote3 Similarly, in Study 3, status seeking was positively associated with sharing of news hostile to the outgroup, both false (moral grandstanding: ß = 0.26 [0.21,0.32], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.16 [0.10,0.22], p < .001) and true (moral grandstanding: ß = 0.29 [0.24,0.35], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.15 [0.09,0.21], p < .001).

Status seeking also clearly predicted sharing of news hostile to the ingroup. This was the case for false hostile news (Study 1: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.30 [0.25,0.35], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.24 [0.19,0.29], p < .001; Study 2: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.09 [0.05,0.12], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.07 [0.03,0.10], p < .001; Study 3: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.31 [0.27,0.36], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.27 [0.21,0.32], p < .001) and for true hostile news (Study 2: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.14 [0.11,0.17], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.07 [0.03,0.10], p < .001; Study 3: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.28 [0.24,0.33], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.21 [0.16,0.27], p < .001).

Overall, whether each status seeking construct mostly affected sharing of news targeting the political outgroup or the ingroup was unclear, as it varied across studies. In Studies 1 and 2, moral grandstanding tended to have a stronger positive association with sharing of news hostile to the outgroup than news hostile to the ingroup. This was the case in Studies 1 and 2 whether the news stories were false (moral grandstanding x hostility target: Study 1: ß = − 0.06 [−0.11, −0.01], p = .021; Study 2: ß = − 0.26 [−0.31, −0.22], p < .001) or whether the stories were true (Study 2: ß = − 0.15 [−0.18, −0.12], p < .001). In Study 3, by contrast, moral grandstanding more strongly predicted sharing of news hostile to the ingroup than to the outgroup, whether the news stories were false (moral grandstanding x hostility target: ß = 0.11 [0.07,0.16], p < .001) or true (ß = 0.08 [0.04,0.12], p < .001).

As regards status-driven risk taking, it tended to more strongly predict sharing of news hostile to the ingroup than to the outgroup. This was the case in Study 1 on false hostile news (status-driven risk taking x hostility target: ß = 0.06 [0.01,0.11], p = .014), and in Study 3, whether the news items were false (status-driven risk taking x hostility target: ß = 0.17 [0.12,0.22], p < .001) or true (ß = 0.15 [0.11,0.20], p < .001). In Study 2, however, status-driven risk taking was associated with an equal tendency to share news hostile to the outgroup and news hostile to the ingroup on both false and true news (status-driven risk taking x hostility target: false news: ß = 0.01; true news: ß = 0.00).

Finally, status seeking indexes were also associated with more sharing of true neutral news (Study 1: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.24 [0.18,0.29], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.13 [0.07,0.19], p < .001; Study 2: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.14 [0.08,0.20], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.08 [0.02,0.14], p = .014). That said, relationships between status seeking and hostile political news sharing tended to be greater overall than with neutral news sharing.

Then, as part of our test of H2, we examine the relationship between status seeking and moralized rationality. As shown in , the two status seeking constructs tended to positively predict moralizing rationality in all three studies (Study 1: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.29 [0.24,0.35], p < .001; Study 1: status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.13 [0.07,0.19], p < .001; Study 2: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.23 [0.19,0.27], p < .001; Study 3: moral grandstanding: ß = 0.36 [0.30,0.42], p < .001; Study 3: status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.16 [0.09,0.24], p < .001). The only exception to this trend was a null effect of status-driven risk taking on moralized rationality in Study 2 (ß = 0.02 [0.03,0.06], p = .49). Overall, moral grandstanding was a markedly stronger predictor of moralizing rationality than status-driven risk taking.

Status Seeking Largely Explains the Relationship Between moralized Rationality and News Sharing

In support of our preregistered hypothesis H2, we observe that the associations between moralized rationality and sharing of true and false news hostile to the outgroup are largely explained away by status seeking. We demonstrate it using seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) tests of differences between the moralized rationality coefficient before vs. after controlling for moral grandstanding and status-driven risk taking together.Footnote4 In Study 1, compared to when they are absent, including the status-seeking variables in the model causes the association between moralized rationality and sharing of false news hostile to the outgroup to drop from ß = 0.11, SE = 0.01, p < .001 to ß = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p = .001. This is a 54% decrease (X2 (1, N = 8778) = 24.66, p < 0.001). In Study 2, adding status-seeking variables in the model caused the coefficient of moralized rationality on sharing of false news hostile to the outgroup to drop from ß = 0.12, SE = 0.016, p < .001 to ß = 0.04, SE = 0.016, p = .005—a 66% fall (X2 (1, N = 9744) = 11.15, p < 0.001). Still in Study 2, adding status-seeking indexes caused the association between moralized rationality and sharing of true news hostile to participants’ outgroup to decrease from ß = 0.11, SE = 0.014, p < .001 to ß = 0.04, SE = 0.015, p = .004. This is a 64% reduction (X2 (1, N = 9752) = 10.41, p = .0012). As regards Study 3, controlling for status seeking variables caused the coefficient of moralized rationality on sharing of false news hostile to the outgroup to shrink from ß = 0.11, SE = 0.017, p < .001 to ß = 0.011, SE = 0.019, p = .55—a 90% plummet (X2 (1, N = 6744) = 16.57, p < .000047).Footnote5 On true news hostile to the outgroup in Study 3, controlling for status seeking variables lowered the coefficient of moralized rationality from ß = 0.15, SE = 0.017, p < .001 to ß = 0.059, SE = 0.018, p = .0014239—amounting to a 61% decrease (X2 (1, N = 6744) = 13.704, p = .0002139).

Testing H3: Intellectual humility and sharing

Finally, we ask whether intellectual humility reduces sharing of news hostile to respondents’ political outgroup (pre-registered H3). Associations are visualized in . As predicted, the intellectual humility scale, present in Studies 2 and 3, was negatively associated with sharing of false (Study 2: ß = − 0.16 [−0.21, −0.10], p < .001; Study 3: ß = − 0.12 [−0.18,-0.06], p < .001) and true (Study 2: ß = −0.13 [−0.17, −0.08], p < .001; Study 3: ß = − 0.11 [−0.17,-0.05], p < .001) news stories hostile to the outgroup.

In Study 2, the influence of intellectual humility on sharing of news hostile to the ingroup was smaller: it was null on false news (ß = −0.03 [−0.07,0.01], p = .1) but negative on true news (ß = − 0.06 [−0.09, −0.02], p = .002). As regards Study 3, intellectual humility was negatively associated with sharing of news hostile to the ingroup, whether the stories were false (ß = − 0.16 [−0.21,-0.11], p < .001) or true (ß = −0.13 [−0.18,-0.09], p < .001).

In Study 2, intellectual humility was thus more strongly negatively associated with sharing of news hostile to the outgroup than to the ingroup, whether false (intellectual humility x hostility target: Study 2: ß = 0.11 [0.06,0.16], p < .001) or true (Study 2: ß = 0.05 [0.02,0.09], p = .003). The pattern reversed in Study 3, however, with intellectual humility being slightly more strongly negatively associated with sharing of news hostile to the ingroup than to the outgroup, whether the news items were false (intellectual humility x hostility target: ß = −0.09 [−0.14,-0.04], p = .001) or true (ß = −0.08 [−0.13,-0.04], p < .001).

Finally, intellectual humility had no influence on sharing of true neutral news in Study 2 (ß = 0.02 [−0.03,0.08], p = .4).

As shown in SM, F-H, high performance in the cognitive reflection test was negatively correlated with willingness to share all news types: news hostile to the outgroup (both false and true), news hostile to the ingroup (both false and true), and true neutral news. However, the negative associations between sharing of news hostile to the outgroup and intellectual humility were greater than associations with cognitive reflection, even when both intellectual humility and cognitive reflection were included in the models. Moreover, intellectual humility and cognitive reflection were only weakly correlated with each other (Study 2: Pearson’s r = 0.10, p < .001; Study 3: Pearson’s r = 0.09, p = .002). All this suggests that intellectual humility and cognitive reflection tap distinct psychological processes and that intellectual humility is a stronger inhibitor of hostile (mis)information sharing than the more widely studied cognitive reflection construct.

Correlations Between Personality Covariates

Matrices of raw correlations between all the personality covariates contained in the studies can be found in SM, F-H (“Relationships between personality covariates”). We focus on some of the associations that are most informative to our theoretical framework here. Moralized rationality weakly negatively correlated with both intellectual humility (Study 2: r = − 0.1, p < .001; Study 3: r = − 0.23, p < .001) and cognitive reflection (Study 1: r = − 0.09, p = .003; Study 2: r = − 0.02, p = .274; Study 3: r = − 0.054, p = .071). This further confirms our suspicion that moralizing rationality is not, as such, associated with more epistemically desirable dispositions.

As regards intellectual humility, it was moderately negatively associated with status seeking variables, which suggests that intellectual humility may inhibit the assertiveness at the core of strategies of status acquisition (Study 2: moral grandstanding: r = − 0.35, p = .001; status-driven risk taking: r = − 0.18, p = .001; Study 3: moral grandstanding: r = − 0.43, p < .001; status-driven risk taking: r = − 0.43, p < .001).

Belief in the News

Analyses of accuracy judgments of the presented news items—run only for Study 2—were exploratory (not pre-registered) and followed the same analysis scheme as intentions to share. The relationships between our personality covariates and belief were overall markedly smaller than with sharing.

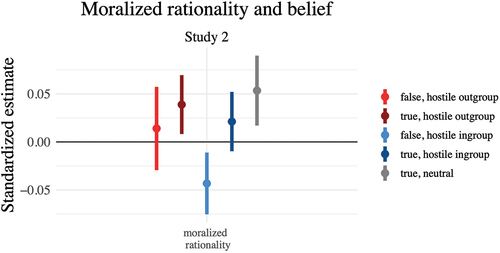

Figure 6. Associations between moralized rationality and willingness to believe each news type in Study 2. Regression coefficients denote the standardized regression coefficient of each personality covariate on the dependent variable with robust SEs clustered around participant ID while controlling for age, sex, and education. Whiskers are 95% confidence intervals.

Associations Between Moralized Rationality and Belief

As illustrated in , moralized rationality was not associated with belief in the false news hostile to the outgroup (ß = 0.01 [−0.03, 0.06], p = .50), but it was weakly positively associated with belief in the true news hostile to respondents’ outgroup (ß = 0.04 [0.01, 0.07], p = .013).

Moralized rationality had a small negative association with belief in the false news hostile to the ingroup (ß = −0.04 [−0.08, −0.01], p < .008) and no association with the true news hostile to the ingroup (ß = 0.02 [−0.01,0.05], p = .10). Thus, moralizing rationality was not associated with more belief in news hostile to the outgroup than hostile to the ingroup, neither false (moralized rationality x hostility target: ß = −0.04 [0.09,0.01], p = .10) nor true (ß = 0.00).

Finally, moralizing rationality was also associated with slightly more belief in the true neutral news (ß = 0.05 [0.02,0.09], p < .004).

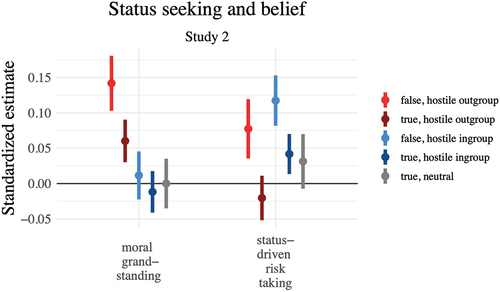

Figure 7. Associations between status seeking (status-driven risk taking and the moral grandstanding index) and belief in each news type in Study 2. Regression coefficients denote the standardized regression coefficient of each personality covariate on the dependent variable with robust SEs clustered around participant ID, while controlling for age, sex, and education. Whiskers are 95% confidence intervals.

Associations Between Status Seeking and Belief

See . Status-seeking inclinations positively predicted belief in false news hostile to the outgroup (moral grandstanding: ß = 0.14 [0.10, 0.18], p < .001; status-driven risk taking: ß = 0.08 [0.04,0.12], p < .001). However, moral grandstanding (ß = 0.06 [0.03, 0.09], p < .001) but not status-driven risk taking (ß = − 0.02 [−0.05, 0.01], p = .20) positively correlated with belief in true news hostile to the outgroup.

Status-driven risk taking was positively predictive of believing false news hostile to the ingroup (ß = 0.12 [0.08,0.15], p < .001) but not moral grandstanding (ß = 0.01 [−0.02,0.05], p = .5). Similarly, status-driven risk taking was positively associated with believing in the true news hostile to the ingroup (ß = 0.04 [0.01,0.07], p = .004) but not moral grandstanding (ß = −0.01 [−0.04,0.02], p = .4). In sum, the influence of moral grandstanding was markedly greater on news hostile to the outgroup than to the ingroup, whether false (ß = −0.11 [−0.16, −0.06], p < .001) or true (ß = −0.06 [−0.09,-0.02], p = .003). By contrast, however, status-driven risk taking was associated with slightly more belief in news hostile to the ingroup than the outgroup, both false (ß = 0.05 [0.01,0.10], p = .30) and true (ß = 0.07 [0.03,0.10], p < .001).

Neither moral grandstanding (ß = 0.00) nor status-driven risk taking (ß = 0.03 [−0.01,0.07], p = .1) had any significant association with belief in the true neutral news.

Relationship Between Moralized Rationality, Status Seeking, and Belief

By contrast with intentions to share, moralized rationality only had a very weak to null relationship with belief in the news hostile to the outgroup. Consequently, jointly controlling for moral grandstanding and status-driven risk taking in the relationship between moralized rationality and belief in news hostile to the outgroup almost did not reduce the coefficient of moralized rationality (the SUR method described above was consequently not applied). On belief in false news hostile to the outgroup, there was no relationship between moralized rationality and belief in the hostile news to begin with (ß = 0.01 [−0.03, 0.06], p = .5), so controlling for status-seeking dispositions made no difference (ß = −0.03 [−0.07, 0.02], p = .24). On belief in true news hostile to the outgroup, the control caused moralized rationality to drop marginally from ß = 0.04 [0.01, 0.07], p = .013 to ß = 0.03 [−0.01, 0.06], p = .12.

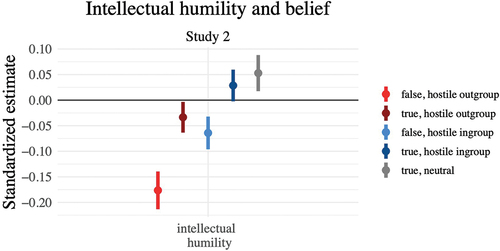

Figure 8. Associations between intellectual humility and belief in each news type in Study 2. Regression coefficients denote the standardized regression coefficient of each personality covariate on the dependent variable with robust SEs clustered around participant ID while controlling for age, sex, and education. Whiskers are 95% confidence intervals.

Associations Between Intellectual Humility and Belief

See . As regards intellectual humility, it had a negative relationship with belief in false news hostile to the outgroup (ß = − 0.18 [−0.21, −0.14], p < .001) and a very small negative association with belief in true news hostile to the outgroup (ß = − 0.03 [−0.06, −0.00], p = .029).

Intellectual humility was also negatively predictive of belief in false news hostile to the ingroup (ß = −0.06 [−0.10, −0.03], p < .001) but uncorrelated with belief in true news hostile to the ingroup (ß = 0.03 [−0.00,0.06], p = .07). In sum, the negative relationship between intellectual humility and belief in news hostile to the outgroup was markedly larger than on news hostile to the ingroup, whether false (intellectual humility x hostility target: ß = 0.11 [0.05,0.16], p < .001) or true (ß = 0.05 [0.01,0.09], p = .018). Finally, intellectual humility was weakly positively associated with belief in true neutral news (ß = 0.05 [0.02,0.09], p = .003). Associations between cognitive reflection and belief in the news can be found in SM, G.

General Discussion

Many rationalist theorists and scholars assume that citizens more morally sensitized to the values of evidence-based and methodic thinking would be better protected from the perils of conspiracy theories, false news, and affective polarization. Yet, attention to the discourse of individuals who pass along politically hostile and false conspiratorial claims suggests that they often sincerely believe to be free and independent “critical thinkers” and to care more about “facts” than the unthinking “sheep” to which they assimilate most of the population (Harambam & Aupers, Citation2017).

Across three large online surveys (N = 4800) conducted in the context of the highly polarized U.S. of 2021–24, we provide the first piece of evidence that moralizing epistemic rationality – a moral motivation to think in logical and evidence-based ways – may actually stimulate the dissemination of hostile claims, both true and false. Specifically, respondents who reported viewing rationality as a moral virtue (Ståhl et al., Citation2016) were more willing to share news on social media that are hostile to their political opponents than individuals low on this trait (Studies 1, 2, 3). Importantly, those effects generalized to two types of news stories: (true) news anchored in actual events and (false) news making entirely fabricated claims. Let us note that we cannot know how often partisans shared false hostile news despite deeming them false, or while judging them plausible. Moreover, moralizers of rationality were also occasionally more prone to share news hostile to their political ingroup (false news in Studies 1 and 3; true news in Studies 2 and 3) but those relationships tended to be smaller than with news targeting political opponents. Ståhl et al. (Citation2016) originally introduced their moralization of rationality scale as predicting motivations to fight against “irrational beliefs” (in the form of donating money to a rationality-oriented charity, cf. their Study 8). We here observe that this scale positively predicts the dissemination of news ascribing made-up plans and misdemeanors to Democrat and Republican leaders and supporters, which arguably could be labeled “irrational.”

To illuminate those counter-intuitive findings, we draw on theories of status seeking and persuasion and provide the first piece of evidence that moralizing rationality can be a form of moral grandstanding. First, we observe that inclinations to take risks in exchange for social status – status-driven risk taking – and a fortiori tendencies to belittle others through the heralding of moral beliefs in public discourse – the moral grandstanding scale – predict claims of moralizing rationality (Studies 1, 2, 3). Second, we find that those status-seeking metrics (especially the moral grandstanding scale) strongly predict motivations to share true and false news hostile to political opponents, and also news criticizing the ingroup, corroborating prior work (Petersen et al., Citation2023). Third, and most importantly, status-seeking dispositions jointly explain much of the positive relationship between moralized rationality and sharing of true and false news hostile to the outgroup in all studies. Taken together, these findings support the notion that individuals seeking to accrue status and reach partisan goals like derogating opponents, recruiting support against them, etc., may be intuitively drawn to claim to moralize rationality, because doing this allows them to frame their hostility as being warranted by superior virtues of truth-seeking and rationality (DeScioli et al., Citation2014; Kurzban, Citation2012; Petersen, Citation2013; Singh & Hoffman, Citation2021; Weeden & Kurzban, Citation2014).Footnote6

Admittedly, our studies have several limitations. First, they do not allow us to identify toward which exact partisan and status goals the stories were shared. Second, the fact that the associations with hostile news sharing were stronger for the moral grandstanding scale than for status-driven risk taking might be due to the latter construct capturing individual differences in risk taking, not just status seeking, which may reduce its explanatory power. Third, all the associations reported in this paper were observed in the context of high levels of mutual animus between U.S. Democrats and Republicans (Finkel et al., Citation2020). It is possible that smaller correlations might be found in less ideologically or affectively polarized environments.

Finally, another major discovery of Studies 2 and 3 is that what may reliably protect people from sharing and believing politically hostile and false news is the under-rated virtue of intellectual humility—that is, dispositions to reflectively acknowledge that one’s intuitions may be unreliable and that one must listen to others’ judgment, experts in particular. Intellectual humility had inhibiting effects on sharing news hostile to both political opponents and the ingroup, but it did not decrease true neutral news sharing, which is good news because such stories are normatively unproblematic. Interestingly, intellectual humility also had a stronger inhibiting effect on sharing of partisan (mis)information targeting the outgroup than the widely studied cognitive reflection test (Kahan, Citation2012; Thomson & M Oppenheimer, Citation2016). Moreover, intellectual humility was associated not just with less sharing of hostile news, but also with less belief in true and false news hostile to the outgroup, and less belief in false news hostile to the ingroup (Study 2). Taken together, those associations indicate a strong and promising link between intellectual humility, lowered political assertiveness and intolerance, and protection from misinformation at the two levels of communication and belief formation.

Now, our data do not reveal why exactly an intellectually modest attitude has those beneficial consequences. One possibility is that intellectual humility may counteract status-seeking and partisan motives, thus leaving more room for truth-seeking motives. This is corroborated by the negative associations we found between intellectual humility and status-seeking variables. Another possibility is that intellectual humility may make it easier to resist inferences of negative intent and simplistic explanations of political failures, and to favor explanations in terms of unanticipated side effects, incompetence, and chance – which better approximate sociological truth (Popper, Citation1945/2019).

Genuine epistemic rationality is a difficult target. Human thinking, if it is to maximize chances of forming and communicating true beliefs about politics under uncertainty, may require more than a staunch moral motivation to be rational. It also needs cultivating dispositions to restrain the pretentions of the ego: trusting one’s hunches less, trusting others more, and sometimes suspending critique.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/udj6t/?view_only=6c35259a0d0f4f3b95ee2d75fffd639c.

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/udj6t/?view_only=6c35259a0d0f4f3b95ee2d75fffd639c.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

All data and code are available at https://osf.io/udj6t/?view_only=6c35259a0d0f4f3b95ee2d75fffd639c.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antoine Marie

Antoine Marie is a postdoctoral researcher at Institut Jean Nicod, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, France. His research investigates the social functions of political (mis)information, how people reason about politics, the politicization of science, and speech repression.

Michael Bang Petersen

Michael Bang Petersen is Professor of political science at Aarhus University, Denmark. His research analyses the relationship between the dark side of human nature and politics, with a focus on misinformation, pandemic responses, and polarization.

Notes

1. We are not saying that rationalist theorists have typically called for the public shaming of people who failed to think and talk in epistemically rational ways. Given the reputational costs entailed, doing so would likely be counterproductive as it might trigger a reactance mechanism, lead the targets of shaming to “lose face,” and thus give them a reason to further oppose the rationalists, and potentially join fringe groups who disseminate dubious information. We are simply saying that various strands of rationalist discourse have tended to see the practice of epistemic rationality as something that should be expected to bring about positive social consequences and thus as morally good and conferring social status.

2. For a purpose unrelated to the present project, the questionnaire of Study 1 also contained a manipulation of the audience respondents were invited to imagine sharing the news to before seeing the items. The vignettes employed varied whether the imagined audience was the political ingroup or the outgroup, and whether participants had to imagine sharing the news from their personal or an anonymous social media account (2 × 2 design, between-subjects). See SM, section F, for vignettes. Crucially, the vignettes had almost no influence on intentions to share the news, and in particular, no statistically significant moderation effect on the relationships between our key covariates and intentions to share the news. This is shown in SM, section F, under the subheader “Demonstration that vignettes manipulating the sharing context had little influence on sharing.” Accordingly, we analyzed the associations between our main covariates of interest and intentions to share the news by pooling the data in Study 1, and are able to compare the results of Study 1 and Study 2.

3. Effects of the moral grandstanding index reported in the manuscript average both prestige strivings and dominance strivings items (Grubbs et al., Citation2019; see also SM, section D). Associations between the moral grandstanding scale and sharing of news hostile to the outgroup in both studies, and with moralized rationality (cf. below), were qualitatively similar whether the index of moral grandstanding contained all items, only the prestige strivings items, or only the dominance strivings items.

4. Note that in R, this procedure uses the “systemfit” function from the eponymous package (https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/r/faq/how-can-i-perform-seemingly-unrelated-regression-in-r/) and yields slightly different estimates for the associations between moralized rationality and sharing than the regression with robust standard errors clustered around participant ID otherwise reported in our analyses based on the “feols” function.

5. On false hostile news in Study 3, we encountered a problem of collinearity in our system of equations when using the “systemfit” R function, which was solved by removing the demographic control variables age, education and gender from the two models the procedure was meant to compare. The drop in size of the coefficient of moralized rationality on sharing of false news hostile to the outgroup in Study 3 when adding moral grandstanding and status-driven risk taking is thus estimated here from models that do not include the demographic controls. The demographic controls are included in all the other regression analyses reported in the paper.

6. Of course, neither our empirical results nor our theoretical approach entail that one should stop valuing principles of epistemic rationality, i.e., stop trying to be more evidence based and logically rigorous when thinking and talking about political issues and public affairs. If anything, we think that more observance of the principles of epistemic rationality can be beneficial in the struggle against ideological and affective polarization, the circulation of falsehoods, and unpragmatic policy making. We simply argue that claiming to moralize rationality can be a form of moral grandstanding in some individuals, i.e., that it may serve to rationalize and cloak particular status seeking and partisan motives (Grubbs et al., Citation2019). However, as specified in the introduction, we do not claim that all cases of moralization of rationality are grounded in status seeking. Some individuals low in self-assertion, dominance, and partisan bias but with strong motivations to base their beliefs on the facts and to reason logically might moralize rationality highly as well.

References

- Alper, S. (2021). When conspiracy theories make sense: The role of social inclusiveness. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/2umfe

- Altay, S., de Araujo, E., & Mercier, H. (2020). “If this account is true, it is most enormously wonderful”: Interestingness-if-true and the sharing of true and false news [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/tdfh5

- Altay, S., Hacquin, A.-S., & Mercier, H. (2020). Why do so few people share fake news? It hurts their reputation. New Media & Society, 1461444820969893. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820969893

- Anderson, C., Hildreth, J. A. D., & Howland, L. (2015). Is the desire for status a fundamental human motive? A review of the empirical literature. Psychological Bulletin, 141(3), 574. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038781

- Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., Pozzebon, J. A., Visser, B. A., & Worth, N. C. (2010). Status-driven risk taking and the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(6), 734–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.09.003

- Bail, C. (2022). Breaking the social media prism: How to make our platforms less polarizing. Princeton University Press.

- Bartusevičius, H., van Leeuwen, F., & Petersen, M. B. (2020). Dominance-driven autocratic political orientations predict political violence in Western, educated, Industrialized, Rich, and democratic (WEIRD) and non-WEIRD samples. Psychological Science, 31(12), 1511–1530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620922476

- Bor, A., & Petersen, M. B. (2022). The psychology of online political hostility: A comprehensive, cross-national test of the mismatch hypothesis. American Political Science Review, 116(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000885

- Brown, D. E. (1991). Human universals. Temple University Press.

- Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Trolls just want to have fun. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016

- Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030398

- Coady, D. (2007). Are conspiracy theorists irrational? Episteme, 4(2), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.3366/epi.2007.4.2.193

- Converse, P. E. (2006). The nature of belief systems in mass publics (1964). Critical Review, 18(1–3), 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913810608443650

- Cooper, J. M., & Hutchinson, D. S. (1997). Plato: Complete works. Hackett Publishing.

- de Araujo, E., Altay, S., Bor, A., & Mercier, H. (2020). Dominant Jerks: Sharing Offensive Statements can be Used to Demonstrate Dominance. 10.

- Dentith, M. R. X. (2019). Conspiracy theories on the basis of the evidence. Synthese, 196(6), 2243–2261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1532-7

- DeScioli, P., Massenkoff, M., Shaw, A., Petersen, M. B., & Kurzban, R. (2014). Equity or equality? Moral judgments follow the money. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1797), 20142112. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2112

- Everett, J. A. C., Pizarro, D. A., & Crockett, M. J. (2016). Inference of Trustworthiness from Intuitive Moral Judgments. 16.

- Fernbach, P. M., Light, N., Scott, S. E., Inbar, Y., & Rozin, P. (2019). Extreme opponents of genetically modified foods know the least but think they know the most. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(3), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0520-3

- Fernbach, P. M., Rogers, T., Fox, C. R., & Sloman, S. A. (2013). Political Extremism Is Supported by an illusion of understanding. Psychological Science, 24(6), 939–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612464058

- Finkel, E. J., Bail, C. A., Cikara, M., Ditto, P. H., Iyengar, S., Klar, S., Mason, L., McGrath, M. C., Nyhan, B., Rand, D. G., Skitka, L. J., Tucker, J. A., Bavel, J. J. V., Wang, C. S., & Druckman, J. N. (2020). Political sectarianism in America. Science, 370(6516), 533–536. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe1715

- Gottschall, J. (2021). The Story Paradox. Basic Books. https://www.basicbooks.com/titles/jonathan-gottschall/the-story-paradox/9781541645974/

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S. P., & Ditto, P. H. (2012). Moral Foundations Theory: The Pragmatic Validity of Moral Pluralism. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2184440. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2184440

- Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science, 363(6425), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706

- Grubbs, J. B., Warmke, B., Tosi, J., & James, A. S. (2020). Moral grandstanding and political polarization: A multi-study consideration. Journal of Research in Personality, 88, 104009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104009

- Grubbs, J. B., Warmke, B., Tosi, J., James, A. S., Campbell, W. K., & Wetherell, G. (2019). Moral grandstanding in public discourse: Status-seeking motives as a potential explanatory mechanism in predicting conflict. PLOS ONE, 14(10), e0223749. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223749

- Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action: Volume 1: Reason and the rationalization of society (Vol. 1). Boston: Beacon Press.

- Harambam, J., & Aupers, S. (2017). ‘I Am not a conspiracy theorist’: Relational identifications in the Dutch conspiracy milieu. Cultural Sociology, 11(1), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975516661959

- Harris, S. (2013). The Making Sense Podcast. https://www.samharris.org/podcasts

- Horowitz, D. L. (2020). The deadly ethnic riot. In The Deadly Ethnic Riot. University of California Press. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1525/9780520342057/html

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2018). The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. 18.

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038

- Jensen, E. A., Pfleger, A., Herbig, L., Wagoner, B., Lorenz, L., & Watzlawik, M. (2021). What drives belief in vaccination conspiracy theories in Germany? Frontiers in Communication, 6, 105. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.678335

- Jerit, J., & Kam, C. D. (2023). Information Processing. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, J. S. Levy, & J. Jerit (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197541302.013.14

- Kahan, D. M. (2012). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection: An experimental study. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500005271

- Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M. J., Bélanger, J. J., Sheveland, A., Hetiarachchi, M., & Gunaratna, R. (2014). The psychology of radicalization and deradicalization: How significance quest impacts violent extremism. Political Psychology, 35(S1), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12163

- Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Rouse, S. V. (2016). The development and validation of the comprehensive intellectual humility scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1068174

- Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

- Kurzban, R. (2012). Why Everyone (Else) Is a Hypocrite: Evolution and the Modular Mind.