ABSTRACT

Research about the epistemic crisis has largely treated epistemic threats in isolation, overlooking what they collectively say about the health of news environments. This study integrates the literature on epistemic problems and proposes a broadly encompassing framework that departs from the traditional focus on falsehoods: epistemic vulnerability. This framework is an attempt to more fully capture the erosion of authority and value conferred to political information, which has put stress on the public spheres of many democracies. The study develops the EV index to quantify this phenomenon at the system level in a comparative manner. Using OLS regression, I test the relationships between the EV index and various structural characteristics of political and media systems. Findings are remarkably consistent with established typologies of media systems. Northern European countries exhibit greater epistemic resilience, while the US, Spain, and Eastern Europe are more vulnerable. The study also offers strong evidence that populism, ideological polarization, and political parallelism contribute to higher levels of epistemic vulnerability. Conversely, public media viewership and larger party systems are associated with more epistemically resilient societies.

Introduction

Problems with the state of democracy are multidimensional, reflecting intersections and interactions among several pathologies. Among these are the increasingly tumultuous relationship between citizens of many countries and their own democratic institutions, the resurgence of far right and populist voices, the various forms of partisan and societal polarization, and the ongoing erosion of democratic norms. Practices that erode broad public confidence in institutions and question the legitimacy of the electoral process have received much scholarly attention.

There is an important dimension that is frequently the subject of comment and study, but which is less thoroughly theorized than problems in norms, polarization, and institutional stress. This involves the epistemic challenges of our information-saturated world. These challenges include problems in news quality and journalistic norms, exposure to disinformation and conspiracy theories, distrust toward the news media, and individual feelings of disorientation or confusion regarding the nature of facts and falsehoods.

Scholarly understanding of this epistemic dimension appears to be incomplete and not fully integrated. The examination of isolated or, at best, adjacent epistemic threats, such as conspiracy ideation (Douglas et al., Citation2017), belief polarization (Benson, Citation2023; Rekker, Citation2021), the sharing of online disinformation (Humprecht et al., Citation2020), or how media systems may amplify or dampen the spread of falsehoods (Benkler et al., Citation2018; Humprecht et al., Citation2020), has been extremely valuable. However, I contend that approaching epistemic threats in isolation, even cross-nationally or longitudinally, does not fully capture the broader epistemic crisis.

While falsehoods are certainly part of the problem, epistemic problems arise even in the absence of falsehoods or conspiratorial instincts (Hameleers, Citation2023, Hoes et al. Citation2023; Van Doorn, Citation2023). Besides, the relationship between citizens and the professional news media is important in its own right and in conjunction with social media, as journalists can debunk falsehoods, promote them, or simply ignore them. Since professional news media generally enjoy a reputation of greater reliability than online media, their rejection may reflect an equally important epistemic problem. An important line of work in this area consists in identifying the predictors of distrust toward the news media, perceptions of exposure to disinformation, and perceptions of news quality. More concerning, the loss of authority and value of political information, and its primary vectors, has led large segments of the public to feel confused and ill-equipped to distinguish truths from falsehoods.

Research has tended to treat these problems as separate but related: as studies of news and social media, of disinformation, or of trust in information. What binds them is epistemic in nature. Perceived exposure to disinformation, distrust in the professional news media, and feelings of disorientation regarding which news messages are true or false all signal the erosion of the authority and value traditionally attributed to political information. In this paper, I take on the problem of developing a measurable concept that can capture this broader epistemic phenomenon: epistemic vulnerability.

Understanding these problems comparatively enables exploitation of what is only context in single-country studies: how the structure of a country’s media and political systems affects epistemic vulnerability across the whole polity. Fortunately, this study is facilitated by foundational contributions from researchers who have typologized media systems along structural lines, such as Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004), Brüggeman et al. (Citation2014), and Humprecht et al. (Citation2022). The main empirical challenge involves navigating the methodological hurdles of studying relationships between variables across levels of analysis and cross-nationally.

First, I introduce the construct of epistemic vulnerability and propose the Epistemic Vulnerability (EV) index to measure it comparatively at the system level. This additive index relies on three components derived from individual survey responses: average perceived exposure to disinformation, average level of distrust toward the professional news media, and average feelings of disorientation, i.e., individuals’ perceived inability to distinguish falsehoods from facts. The study seeks to answer the following questions. How do levels of epistemic vulnerability vary across Western democracies? What is the degree of correspondence between levels of epistemic vulnerability and previous classifications of media systems? What is the relationship between the structure of political and media systems and levels of epistemic vulnerability?

I apply the metric to 20 Western democracies and use Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression to test whether a country’s level of epistemic vulnerability is predicted by the size of its party system, levels of ideological and affective polarization, the electoral strength of populist parties, political parallelism, and public television viewership. The results show that Northern European countries are more epistemically resilient while the United States, Spain, and Eastern European countries are more epistemically vulnerable. These results are highly consistent with previous efforts to typologize media systems. The study finds that public television viewership and the size of party systems are strongly and inversely related to epistemic vulnerability. Additionally, empirical evidence suggests that political parallelism, ideological polarization, and populism are associated with higher levels of epistemic vulnerability.

Integrating the Literature on Epistemic Dimensions

Exposure to Disinformation & Its Limits

Disinformation, which is deliberately fabricated or manipulated information disseminated to achieve political, partisan, financial or other ends, needs to be distinguished from misinformation, which is the inadvertent sharing of false information without intent to mislead (Benkler et al., Citation2018). The spread of disinformation is the most obvious dimension of the epistemic challenge facing modern democratic societies. A recent study by Kapantai et al. (Citation2020) consolidated existing taxonomies of disinformation and identified at least 10 sub-types described in the literature: clickbait, conspiracy theories, fabrication, misleading connections, hoaxes, biased or one-sided reporting, imposter, pseudo-science, rumors, fake reviews and trolling. These are more or less applicable to public affairs, and may present varying degrees of facticity or danger.

In addition to directional motivations, acceptance of falsehoods and conspiracy theories is facilitated by motives that are epistemic, social, and existential in nature (see Douglas et al., Citation2017). In terms of consequences, disinformation is more easily recalled than truthful messages, has lingering effects that are resistant to correction, and impedes problem-solving (Ecker et al., Citation2022; Thorson, Citation2016). Frequent exposure can also lead to illusory truth effects (Pillai & Fazio, Citation2021) and is predictive of phenomena that are corrosive to democracy such as distrust in institutions and experts, political polarization, populism, and ideological extremism. From many perspectives, a healthy public sphere requires that citizens have access to a shared set of facts. In consequence, the level of exposure to falsehoods is an essential indicator of the health of news environments.

Yet, exposure to disinformation is notoriously difficult to measure due to confounds and problems with self-reporting that are difficult to account for outside of strictly controlled experimental designs. Several measures relying on different forms of data are in use, e.g., frequency of exposure, perceived exposure, actual exposure, or ratio of false versus true content. Accurate recall poses enormous problems for many survey measures, and findings are often contingent on domestic and temporal contexts. These difficulties have impeded the comparative literature on disinformation. A few studies focus on system-level resilience to online disinformation (Humprecht et al., Citation2020) or its sharing (Humprecht et al., Citation2021). These comparative reports are highly valuable, and they suggest that the structure of media systems and the political environment play a significant role in facilitating or impeding the spread of disinformation.

The problem of disinformation represents only one dimension of the epistemic challenge facing democracies. Recent contributions show that the adverse effects of disinformation extend far beyond the harms of accepting or being exposed to falsehoods, leading to non-attitudes, skepticism and rejection of factual information, and general impediments to truth attainment (Hameleers, Citation2023, Hoes et al. Citation2023; Van Doorn, Citation2023). Additionally, citizens may or may not recognize false claims, and they may accept or reject messages in either case, compounded by reception gaps. Disinformation may also come from clearly identified sources, unidentified sources, or be more pervasive across sources and news brands. Source as well as content can elicit more or less motivated reasoning about messages. In that way, epistemic attitudes are shaped by more considerations than just perceptions of news quality or exposure to disinformation. A robust measure of epistemic vulnerability needs to consider the relationship the public has with the media system itself, and also their level of confidence in navigating the wealth of messages, both true and false, that circulate in the public sphere.

(Dis)Trust in the Media

Scholars of democracy generally agree that some degree of trust – in the political process, in institutions, and in one another – is a requirement for healthy democracy. Trust in the media is largely associated with trust in institutions (Ariely, Citation2015). It is therefore not surprising that studies about democracy regularly include trust in the media as an indicator of a broader trust concept. However, in comparison, most studies about the news media treat trust either as a predictor for some other behavior, as an outcome variable of its own, or seek to compare the evolution of trust across countries, thereby overlooking its inherent value as an indicator of the epistemic health of democracies (Hanitzsch et al., Citation2018).

Trust has been researched and debated extensively (for thorough reviews, see Engelke et al., Citation2019; Fawzi et al., Citation2021). Various questions subsist regarding both the conceptualization and measurement of trust and distrust, including toward the news media (Fisher, Citation2016). Notable critiques emphasize problems associated with conceiving trust and distrust as the ends of a single spectrum (Engelke et al., Citation2019; Van De Walle & Six, Citation2014). In addition, the two concepts have often been captured only partially, via their antecedents: media skepticism and hostile media perceptions for distrust, trustworthiness and credibility for trust (Engelke et al., Citation2019; Strömbäck et al., Citation2020). Despite recommendations to disentangle these nuances, scholarship has been limited by the absence of widely accepted survey instruments for distrust (Engelke et al., Citation2019). As a result, distrust is almost exclusively measured by reversing measures of trust.

Kohring and Matthes (Citation2007) reviews the multiple dimensions of the concept of media trust and further point out the methodological shortcomings of previous operationalizations. Their characterization of trust in the media as a second-order concept, reflective of the interaction of four individual-level phenomena, could suggest that single-item measures of trust might be less useful to assess individual attitudes than to understand perceptions of media systems as a whole at the macro level. That being said, more recent studies by Yale et al. (Citation2015) and Prochazka and Schweiger (Citation2018) report concerns of potentially insufficient discriminant validity. Moreover, Tsfati et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate that general and topical trust in the media must be differentiated and cannot be substituted, highlighting asymmetric patterns of trust depending on the topic covered. Their study emphasizes the usefulness of general trust in the media as a metric for comparative research.

The potential sources of distrust in the professional news media are numerous at the individual level, making inferences about the aggregate state of journalism or the health of a media system difficult. Trust is associated with many characteristics relating to audience attributes and perceived media performance (Livio & Cohen, Citation2018). Prominent among these are ideology (Gronke & Cook, Citation2007; Lee, Citation2010), political extremism (Stroud & Lee, Citation2013) and populist attitudes (Fawzi, Citation2019; Hanitzsch et al., Citation2018; Livio & Cohen, Citation2018). Trust may also be confounded by individual news diets and discrepancies in the evaluation of individual outlets as opposed to the media in general (Arceneaux et al., Citation2012; Daniller et al., Citation2017), ideological selectivity in news consumption (Arceneaux et al., Citation2012), the ever-growing partisan and propaganda outlets (Labarre, Citation2024), or trust in individual journalists versus media companies. Empirically, however, evidence suggests that news diet and ideology plays little role in evaluations of general trust in the media (Tsfati et al., Citation2023). There remains some uncertainty regarding what media respondents consider when assessing general trust in the media, and which cognitive strategy respondents use to come to an evaluation. However, a study by Tsfati et al. (Citation2023) suggests that respondent evaluations primarily proceed from a representativeness heuristic – mainly mainstream media – and are not skewed by negativity bias, irrespective of respondent ideology.

Another way in which an improved conceptualization of trust in media is possible concerns news quality. While studies have long treated perceptions of news quality and trust as interchangeable (Fawzi et al., Citation2021), credibility only partially captures the larger trust construct (Engelke et al., Citation2019). Interestingly, Tsfati et al. (Citation2023) report only minor differences between news credibility and their single-item measure of trust in the media. This begs the question of whether perception of news quality and trust in the media capture different dimensions of a single epistemic problem. In line with third-person perception, individuals who distrust the news media may actually feel adequately sheltered from disinformation in their own lives. The source of distrust may be perceived ideological slant and the hostile media perceptions – something a measure of exposure to disinformation would likely not capture. No matter the source, lack of trust in the news media is toxic to democracy. From a normative standpoint, the role of the news media is to inform the public and to sanction that the information provided was verified or obtained following widely accepted journalistic norms. In that way, distrust in the professional news media corrodes the epistemic foundation of democratic politics.

Going Beyond Disinformation and Distrust: Disorientation

Disinformation and distrust in the media are related but distinct components of epistemic health. A third component is also necessary for a robust way to understand epistemic vulnerability across countries. This component addresses the internal mental state of citizens that is associated with their perceptions of what is happening externally to them – the flows of disinformation and the trustworthiness of news businesses. As citizens perceive the existence of true and false claims in circulation, and as they attend more or less to news businesses about which they have varying degrees of trust, they may vary in the extent to which they feel confident or disoriented. Some people could report frequent exposure to disinformation and low trust in the professional news media, but feel relatively confident in their own epistemic state for any of a number of reasons: high political sophistication, third-person perception, ego-defense mechanisms, or over-confidence associated with low political sophistication, as in the Dunning-Kruger effect. Some may react to perceptions of ubiquitous falsehoods and untrustworthy media with disorientation, but others exposed to reliable information from trustworthy sources may doubt it and experience disorientation nonetheless.

A robust measure of epistemic vulnerability should include people’s cognitive reactions to the state of news and disinformation. This idea is captured in “disorientation,” which refers to the condition in which citizens have lost the capacity to distinguish facts and falsehoods (Benkler et al., Citation2018; Humprecht et al., Citation2020; Nielsen & Graves, Citation2017). Sixty-four percent of US adults say that false news stories cause “a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current issues and events” (Barthel et al., Citation2016; Rainie et al., Citation2017, p. 2). Disorientation is not only measurable in surveys but also at the cognitive level. Reading false or inconsistent information has been shown to subsequently slow down cognitive processing of correct information (Jacovina et al., Citation2014; Rapp, Citation2008; Rapp & Salovich, Citation2018).

The inability to distinguish facts from falsehoods may lead to political apathy, similar to feelings of political inefficacy. Indeed, disorientation is akin to internal inefficacy, but it focuses on information and news rather than political institutions and processes. Past research on political efficacy has established positive associations with political participation (Vecchione et al., Citation2014). This line of work suggests that it is not actual political knowledge that initiates political participation, but rather perceptions of knowledge. From a normative standpoint, having basic knowledge about political institutions certainly helps engage in the public sphere. However, having what Lupia and McCubbins (Citation1998) call “trusted speakers” who citizens can take cue from to understand day-to-day public affairs is arguably more useful and may increase internal efficacy. In a democracy, this should be the role of the professional news media. The fact that a large proportion of the population reports being skeptical of their own capacity to determine whether a news story is true or false in spite of the abundance of channels available is alarming. This phenomenon highlights the importance of understanding not only the state of disinformation and the state of news, but the state of people’s minds about their ability to comprehend politics accurately.

Epistemic Vulnerability

Current scholarship widely acknowledges a dynamic process, marked by the proliferation of disinformation and shifts in epistemic attitudes, often encapsulated in the disinformation literature by the phrase “epistemic crisis.” But where does this crisis lead to? What is the scale of the epistemic problems that result from this crisis? Traditional responses have primarily focused on problems like disinformation and conspiracy belief; sometimes, epistemic tribalism. Recent research, however, suggests that epistemic problems may arise even in the absence of outright falsehoods (Hameleers, Citation2023, Hoes et al. Citation2023; Van Doorn, Citation2023), indicating the need for a more encompassing conceptual framework. I propose a framework that extends beyond this traditional focus, what I call “epistemic vulnerability.”

Epistemic vulnerability is a way to conceptualize the condition resulting from widespread epistemic disorder throughout public spheres. Work on disordered public spheres has identified various contributors to disorder, including the perceived decline in news quality, distrust toward bona fide epistemic authorities and other co-occuring epistemic problems. Though distinct, these challenges all relate to the overall epistemic health of democracies. In that way, epistemic vulnerability reflects a common, cross-cutting epistemic dimension that is corroded throughout public spheres and is both theoretically valuable and helpful to quantify.

Empirically, epistemic vulnerability should manifest as widespread distrust in professional news media, heightened perceptions of exposure to falsehoods, and widespread inability to discern factual accuracy in political information. This state emerges from a convergence of factors, which include the proliferation of disinformation and partisan propaganda, anti-establishment sentiment, the multiplication of alternative news sources, the diminishing effectiveness of gatekeeping, news fragmentation and perceived media bias, all variants of political polarization, and the erosion of democratic norms, among others. Epistemic vulnerability more broadly reflects a shift in the way authority is attributed to political information such that it harms the public’s ability to engage in public affairs and make informed political decisions. Epistemic vulnerability affects collective understanding, behavior, and decision-making processes, and it may lead to various negative outcomes at the individual and system level. These include but are not limited to decreased civic engagement and political apathy, cynicism, ideological extremism, conspiracy mindset, tribal epistemology, further polarization, populist sentiment, and other phenomena frequently described as pathologies of democracy in the literature. At its most serious stage, epistemic vulnerability might beget challenges to the legitimacy of democratic institutions and governance.

Theoretical Links with Epistemic Vulnerability

To my knowledge, no study has explored the relationship between a comprehensive epistemic concept like epistemic vulnerability and other variables common to the comparative study of media and democracy. Several theoretical relationships can be reasonably proposed, though it is essential to note that the type of data used in this study precludes drawing causal inferences.

The Political Environment

Polarization should be associated with epistemic vulnerability, as it is evidently predictive of the three dimensions the index is built from. The dominant framework for studying polarization consists of distinguishing between ideological and affective forms. It is reasonable to assume that the direction of association between ideological polarization and epistemic vulnerability flows from the former to the latter. For affective polarization, however, a stronger theoretical case exists for a mutually reinforcing relationship. Many scholars agree that high polarization of both kinds makes a society more prone to experiencing epistemic failures (Alcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Benkler et al., Citation2018; Benson, Citation2023; Humprecht et al., Citation2020). A polarized environment exacerbates the contamination of the news environment with partisan propaganda, whether its dissemination seeks to advance ideological goals or to score points against a demonized adversary (Benkler et al., Citation2018). This should increase perceived exposure to disinformation, a good proportion of which may be caused by the hostile media phenomenon. Polarization also reduces critical engagement with diverse viewpoints (Benson, Citation2023). Conversely, epistemic problems, such as manipulation or the loss of authoritative news source may lead to a deepening of partisan divides. Finally, citizens who find that the news they consume is polluted by slanted, polarized content may report feeling disoriented regarding the veracity of the news they receive and less trusting of the news media (Newman & Fletcher, Citation2017). This phenomenon may be especially true for those citizens most disengaged from partisan politics.

The second characteristic of political systems that should be associated with epistemic vulnerability is concomitant to the role of polarization: the size of party systems. On the one hand, more parties might reduce the probability that their supporters will find themselves in homogeneous informational and social environments. On the other hand, a small party system clarifies ideological divides and encourages citizens to process politics in terms of simple in-group and out-group perceptions. This may lead to belief polarization (Rekker, Citation2021) and create opportunities for epistemic problems to rise.

The third characteristic that should predict epistemic vulnerability is the strength of populist organizations. Populist rhetoric strips down political stories of their nuance, by conflating the factual and normative dimensions of political issues and boiling them down to a simple dichotomy between right and wrong (Rosenberg, Citation2020). Connections between populism and disinformation have been widely observed (Bennett & Livingston, Citation2018; Humprecht et al., Citation2020; Marwick & Lewis, Citation2017). In blurring the frontier between “claims of truth” and “claims of right,” populists redefine knowledge in terms of affective and normative evaluations. Their consistent denunciation of knowledge-producing bodies such as scientific institutions and the professional news media (Krange et al., Citation2021; Ross & Rivers, Citation2018; Schulz et al., Citation2018), and their paranoid worldview create fertile ground for conspiracy theories (Bergman, Citation2018; Christner, Citation2022; Imhoff et al., Citation2022). Populism therefore likely feeds off and contributes to the ambient distrust and disorientation felt by citizens, especially those most disengaged from politics.

The Structure of Media Systems

Recent studies converge on the key role of media systems in the dissemination of disinformation, trust, and perceptions of journalism quality. The first aspect of media systems is the relative weight of public broadcasting (PBS) in the news environment. Numerous studies demonstrate a strong positive correlation between a well-established PBS system and higher levels of political knowledge (Aalberg & Curran, Citation2012; Curran et al., Citation2009) as well as higher exposure to cross-cutting content (Aalberg et al., Citation2010; Castro-Herrero et al., Citation2018; Esser et al., Citation2012; Wessler & Rinke, Citation2014). PBS also exerts an “ecological” influence on private outlets that leads to an increase in news quality across the entire news environment, an influence that Humprecht et al. (Citation2020, p. 10) call “market conditioning.” This virtuous competition slows the dissemination of falsehoods, notably on television, and may contribute to improving trust in the news media. From a theoretical perspective, the direction of association between epistemic vulnerability and PBS is likely uni-directional, going from the latter to the former.

The second characteristic of media systems that should matter for epistemic vulnerability is political parallelism. The concept finds its roots in party-press parallelism, which referred to the formal affiliation or more informal commitment of certain news sources to political parties (Blumler & Gurevitch, Citation1995; Seymour-Ure, Citation1974). The concept was broadened in Hallin and Mancini’s (Citation2004) typology of media systems and operationalized in studies by Brüggeman et al. (Citation2014) and Humprecht et al. (Citation2022) to encompass the following dimensions: the lack of separation of news and commentary, partisan influence and policy advocacy, political orientation of journalists, media-party parallelism, political bias, and dependence of PBS. Faithful to the concept’s grounding in path dependence, recent scholarship has noted shifts in levels of parallelism in several countries, like the US (Nechushtai, Citation2018). These changes respond to the digitalization of media systems and, more contextually, political polarization (Humprecht et al., Citation2022; Nechushtai, Citation2018). Theoretically, the perception that certain outlets are engaging in partisan advocacy should generate more distrust toward the news media in general. Surprisingly, Ariely (Citation2015) finds a small positive correlation between media parallelism and media trust. However, Newman and Fletcher (Citation2017) find that perceived political bias in reporting is largely cited by respondents as a justification for not trusting the news media. Their respondents also attribute the blurring of facts and fiction to political advocacy in the media.

All of these considerations can be summarized in a set of five hypotheses.

H1:

Countries where ideological polarization is higher will exhibit higher levels of epistemic vulnerability.

H2:

Countries where affective polarization is higher will exhibit higher levels of epistemic vulnerability.

H3:

The effective number of parties in a given country is inversely correlated with levels of epistemic vulnerability.

H4:

Epistemic vulnerability will be higher in countries where populist organizations are stronger.

H5:

Countries with larger PBS viewership will have lower levels of epistemic vulnerability.

Methods

Testing these hypotheses required developing a custom multi-country dataset containing a range of country-level indicators. Country selection was motivated by comparability and availability of data. The sample consists of 20 European and North-Atlantic democracies described in existing typologies of Western media systems (see Brüggeman et al., Citation2014; Hallin & Mancini, Citation2004; Humprecht et al., Citation2020, Citation2022). Regarding predictors, a list of the data sources used to build the custom dataset is included in the online appendix (see Appendix 3). Following is an overview of how each measure is built.

The Epistemic Vulnerability Index

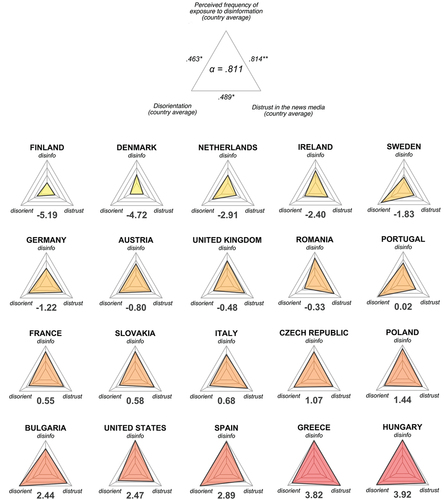

The proposed Epistemic Vulnerability (EV) index captures three important manifestations of the concept at the system level: widespread distrust in professional news media, heightened perceptions of exposure to falsehoods, and widespread inability to discern facts from falsehoods. While this metric may be a partial operationalization of the theoretical concept, the EV index captures a good deal of the literature, and the three dimensions that are included are arguably the three epistemic challenges that are most pervasive and corrosive to democracies. This metric could in principle be extended in future research to encompass additional dimensions, which are likely to be related to the three components of the present index. In terms of levels of analysis, the most intuitive way to understand the EV index is as hybrid. Using individual-level measures on the three dimensions, one can compute country-level averages on each, and then combine these additively into a single country-level metric. This allows theorizing and analyzing the relationship between country-level epistemic vulnerability and many important comparative measures, without being hindered by individual-level factors that may introduce heterogeneity. The EV index is calculated from questions about respondents’ perceived frequency of exposure to falsehoods, respondents trust in the news media (reversed), and respondents’ feelings of disorientation, drawing on three survey datasets: Flash Eurobarometer 464, and American Trends Panels (ATP) W45 and W91 (combined N = 36,775). The three dimensions of the EV index are well correlated at the aggregate level. Pearson’s correlation coefficients are displayed in . Cronbach’s alpha was .81, indicating good internal consistency and suggesting that the dimensions are tapping into the same construct.

Predictors

Affective Polarization

Affective polarization is measured as the average affective distance of out-parties from one’s in-party, using survey data from CSES modules III-V. For each respondent in each country, I sum up the distances between respondents’ in-party evaluation and evaluations for all the out-parties, and weight them by the share of the vote won by each party after discounting the vote share of the in-party. Country scores are in the online appendix (see Appendix 4).

Ideological Polarization

My measure of ideological polarization also relies on CSES modules III-V. For every country, I calculate the ideological center of gravity by taking the average position of all the parties on the left-right scale, weighted by the electoral size of each party. Then, for each party, I calculate its distance from the center of gravity by subtracting its left-right score from the latter. Squared distances are then summed up and weighted again by the electoral size of each party. I use parliamentary elections for most countries and presidential elections (first round when applicable) for presidential systems. Country scores and additional details regarding the measure are in the online appendix (see Appendix 5).

Effective Number of Parties

This measure was originally proposed by Laakso and Taagepera (Citation1979) and reflects the number of parties in a given election, weighted by their relative electoral size. Data for this variable come from the National Level Party Systems dataset for the US, and WhoGoverns.eu for EU countries.

Strength of Populism

The strength of left and right-wing populist organizations in a given country is estimated using the vote share won by all populist parties on the left and on the right in the election closest to 2018. The data come primarily from the Timbro Authoritarian Populism (TAP) index, which is unfortunately limited to legislative elections. Populist movements being often highly personalized, one can expect populist movements to perform better in more candidate-centric elections, e.g., presidential elections. For this reason, I calculate observations for presidential and semi-presidential systems (FR, PL, PT, RO) using presidential election results.

The US case required further consideration. US elections are inconsistent in their use of party primaries, and the participation of a populist candidate in one of the two parties’ primaries does not guarantee a place on the presidential ticket. I employ a hybrid, conservative approach that considers the share of the votes won by Bernie Sanders out of all the votes cast in the 2016 primaries of both parties combined with the share of the vote won by Donald Trump in the 2016 general election. The US data come from The Green Papers. A lengthier methodological discussion and country scores are included in the online appendix (see Appendices 6 and 7).

Daily PBS Viewership

Measures of daily viewership of PBS come from the European Audiovisual Observatory Yearbook 2019/20. For the US, the data come from a custom survey I conducted with collaborators from the ReCitCom project, in which respondents were asked to say how often they use each of a list of news sources. Daily viewership scores are included in the online appendix (see Appendix 8).

Political Parallelism

The data for this variable come from Humprecht et al. (Citation2022), who report values for their political parallelism index in their appendix. The index itself has a Cronbach’s alpha of .86. The index measures the role played by political advocacy in journalism across countries, and is built from 5 dimensions, originally described by Brüggeman et al. (Citation2014). The first is partisan influence on news businesses, and the extent to which the latter engage in policy advocacy. The second dimension captures the extent to which the political orientation of journalists is known to the public. The third, called media-party parallelism, reflects ideological news selection by the public, and the fourth, political bias, measures bias and lack of pluralism in the coverage of public affairs. Lastly, the fifth dimension captures PBS dependence on the state, which is reflected in the rate of CEO turnovers associated with changes in government, and the degree of politicization of public broadcasters (see Brüggeman et al., Citation2014; Humprecht et al., Citation2022 for further discussion on the measure).

Results

Starting with the first research question, the radar charts in show EV index country scores, ranked in ascending order, as well as the three constituent parts for each country. Northern European countries are generally more epistemically resilient, while the US, Spain, and Eastern European countries are more epistemically vulnerable.

How consistent are these results with previous media system taxonomies? I performed Kruskal-Wallis tests to compare the country rankings produced from the EV index with the classifications of Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004), Brüggeman et al. (Citation2014), and Humprecht et al. (Citation2022). An overview of these classifications is available in the online appendix (see Appendices 12 and 13). The test results showed a Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared statistic of 11.777 (p = .008) for Hallin and Mancini’s classification. For Brüggeman and colleagues, the statistic was 10.021 (p = .040). The taxonomy of Humprecht and colleagues resulted in a Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared value of 11.376 (p = .003). These tests suggest that the EV index is not only consistent with established classifications of media systems but also adds valuable new insights. Turning to the comparison with Humprecht et al.’s (Citation2020) study of resilience to online disinformation, I calculated Spearman’s correlation coefficient to determine the degree of association between the ordered rankings (r = .916, p = 2.2e-16). The two methodologies appear reliable and consistent, resulting in a similar relative evaluation of the countries considered.

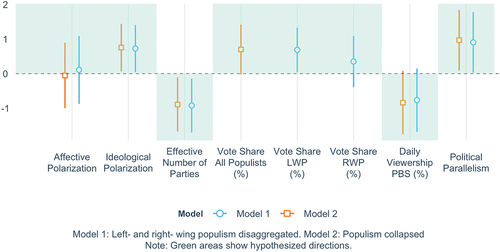

OLS was used to test the relationship between epistemic vulnerability and the structures of political and media systems at the country level. Because populism can reasonably be conceptualized as a single concept or as distinct right-wing and left-wing versions, two separate models using each approach were specified. Goodness-of-fit statistics indicate that the models explain a remarkable proportion of the variance, between 76% for Model 2 and 77% for Model 1. Because interpreting coefficients in a substantive manner can be difficult, each predictor is discussed in terms of its effect on the EV country rankings, under certain hypotheticals. Scaled estimates from the two models are displayed in . Regression tables are available in the online appendix, along with alternative models that use different measures as robustness checks (see Appendices 9.A. through 11.C.). Readers should note that alternative models including measures of cross-platform audience polarization and audience duplication were also specified. However, empirical evidence did not support the inclusion of these variables, and the findings of the more complex models were consistent with the simplified models. For transparency, these alternative models are also included in the online appendix (see Appendix 11.C.).

Hypothesis 1 postulated that countries with high ideological polarization would experience higher levels of epistemic vulnerability. Both models support the hypothesis, with equivalent positive coefficients (0.364 and 0.378) and p-values (.04 and .034). Consider the UK, which experiences very high levels of ideological polarization (ideopol = 8.09). Model 2 predicts that, everything else constant, the UK would drop to fourth least vulnerable country (predicted EV = −2.50) as opposed to its current eighth position (actual EV = −0.48) if it had the same level of ideological polarization as Ireland (ideopol = 2.76). If its level of ideological polarization dropped down to Poland’s very low levels (ideopol = 1.65), the UK would actually overtake the Netherlands as third least vulnerable country (predicted EV = −2.92). The finding holds irrespective of whether populism is collapsed or disaggregated.

Hypothesis 2 proposed that countries with higher levels of affective polarization would exhibit increased epistemic vulnerability. While the hypothesis receives tentative support from alternative models that rely on older data for political parallelism (see Appendix 10.C.), Model 1 and Model 2 find no evidence to support the hypothesis. I performed a robustness check on both models by substituting my measure of affective polarization with data from the V-DEM dataset (see Appendix 10.A.). The change in measure did not significantly affect the findings of either base models. Consequently, hypothesis 2 must be rejected.

Hypothesis 3 stated that levels of epistemic vulnerability would be inversely correlated with the effective number of parties in a given country. Both models support the hypothesis, with equivalent coefficients (−0.499 and −0.483) and p-values (.024 and .029). Large party systems are associated with lower EV scores, smaller party systems are associated with higher scores. Consider the US, which currently ranks as the fourth most epistemically vulnerable country (actual EV = 2.47). If the US had the same number of parties as the Netherlands (8.5) instead of its majoritarian two-party system, model 1 predicts that, ceteris paribus, the US would recede to a more enviable eleventh position (predicted EV = −0.32) in the country rankings, just between Romania (EV = −0.33) and Portugal (EV = 0.02).

Hypothesis 4 proposed that epistemic vulnerability would be higher in countries where populists are electorally stronger. The hypothesis is generally supported by both models, though with nuances. Model 1 finds a substantial, positive effect of left-wing populism on epistemic vulnerability (0.055, p = .038), but no significant effect for right-wing populism. Model 2, which collapses left- and right-wing populism into one variable, shows that for every additional percentage point of the vote earned by populists in a given country, its EV score increases by 0.034 (p = .055). Consider the following illustrations. The EU average vote share for populists in individual countries stands at 27.98%. In terms of election results, Romania has the weakest populist organizations (0.36%) and currently is the twelfth most epistemically vulnerable country (actual EV = −0.33). Model 2 predicts that if Romania’s populist organizations had the average electoral strength of EU populists, Romania would move up to eighth most vulnerable country in the rankings (predicted EV = 0.6), ceteris paribus. Hungary is another pertinent case. In Hungary, populists won 68.9% of the vote in 2018. If the vote share of Hungarian populists fell to EU average levels, Hungary would go from most epistemically vulnerable country (actual EV = 3.92) to third place (predicted EV = 2.54). Consider this last example. In Greece, left-wing populists won 45.1% of the vote in 2015, making it a good case to interpret the effect of left-wing populism on the EV index. If instead they had only won 10% of the vote, Model 1 predicts that Greece would recede to fifth most vulnerable country (predicted EV = 1.90) instead of second (actual EV = 3.82). Maps comparing the geographical distribution of EV scores and populist strongholds are available in the online appendix (see Appendices 1 and 2). Overall, hypothesis 4 is supported by the models, though the findings are nuanced when left- and right-wing populism are distinguished.

Hypothesis 5 predicted that countries with larger PBS viewership would be less epistemically vulnerable. Both models find a large negative effect of PBS viewership on epistemic vulnerability approaching significance at the 0.1 level (p-values of .094 and .069). Note that the finding is even stronger and statistically significant at the 0.05 level in many of the alternative models reported in the online appendix (Appendices 11.A. through 11.C.). The finding is robust to the use of alternative measures for populism, media-party parallelism, and affective polarization (see Appendices 10.A. through 10.C.). With an N of only 20, I interpret this as strong evidence that daily viewership of PBS and epistemic vulnerability move together. Italy is currently the eighth most vulnerable country in the rankings (actual EV = 0.68). The daily audience of Italian PBS amounts to 36.2% of the population. Model 2 predicts that if the daily audience of Italian PBS dropped to US levels (9.6%), Italy would move up to sixth most epistemically vulnerable country (predicted EV = 1.96). The UK serves as an ideal case for examining the relationship between PBS viewership and the EV index. With a hypothetical reduction in PBS viewership from current levels (46.3%) to US levels, the UK would escalate from twelfth most vulnerable country (actual EV= −0.48) to sixth (predicted EV = 1.28).

While political parallelism was generally anticipated to affect EV scores, no formal hypothesis was proposed on the matter. Both Model 1 and Model 2 find a large effect for media-party parallelism (1.275 and 1.365), significant at the 0.05 level (p-values of .036 and .026). Denmark, currently the second least epistemically vulnerable country in the sample (actual EV = −4.72), has the lowest score on the political parallelism index (−1.27). According to Model 2, if its parallelism score was equivalent to that of Spain (0.97), Denmark would recede to being only the fifth least vulnerable country in the rankings (predicted EV = −1.68).

Comparing different measures of political parallelism adds fascinating nuance to the models’ findings. The European Media Systems Survey (EMSS) 2010 included independent measures for newspaper and television parallelism. The post-hoc analysis conducted using these two variables instead of Humprecht et al. (Citation2022) political parallelism index suggests that the observed effect may primarily be the result of newspaper parallelism, and not television parallelism. One of the alternative models predicts that if the UK – which exhibits the highest level of newspaper parallelism (15.20) in the EMSS data – had the same levels of newspaper parallelism as Slovakia (7.32), the UK would rank as the second least epistemically vulnerable country of all (predicted EV = −5.13), ceteris paribus. Granted that the measures are older, the finding calls for further inquiry into the impact that partisan newspapers and tabloids have on epistemic vulnerability.

Conclusion

While the political and institutional symptomatology of the decline of democracies is well documented, the literature on epistemic threats remains less integrated. Most research has examined epistemic problems in isolation, overlooking what they collectively say about the state of the public, the health of democracy, and the fragility of its epistemic foundations. Recent scholarship showing that epistemic problems may arise even in the absence of falsehoods has led to growing pains for our field, and called for a more expansive framework. In this study, I discussed how to integrate the literature on epistemic problems and proposed a broadly encompassing framework that goes beyond the traditional focus on falsehoods: epistemic vulnerability. This framework is an attempt to more fully capture the erosion of the authority and value of political information, which has exerted considerable strain on the public spheres of many Western democracies. The EV index proposed alongside the new construct is used to quantify epistemic vulnerability at the system level and in a comparative manner.

The study sought to answer the following questions. How do levels of epistemic vulnerability vary across Western democracies? What is the degree of correspondence between the EV index and previous classifications of media systems? What is the relationship between the structures of political and media systems and epistemic vulnerability? Results show a remarkable correspondence with previous typologies of media systems. Northern European countries are more epistemically resilient while the US, Spain, and Eastern European countries are more epistemically vulnerable. The study also finds that daily viewership of public television and the size of party systems are strongly and inversely related to epistemic vulnerability. On the other hand, political parallelism, ideological polarization, and populism are associated with higher levels of epistemic vulnerability.

Naturally, this study is not devoid of limitations. First, the cross-sectional data precludes definitive causal conclusions, despite reasonable theoretical expectations regarding the relationships between system-level predictors and the EV index. Relatedly, the data used in this study do not permit assessing the longitudinal stability of the index. Since the metric is built from country averages of public attitudes, the EV index is likely to respond to variations in factors that can be expected to have an effect on epistemic vulnerability. Future studies should address this limitation and assess the sensitivity of the EV index to events known to have an influence on its three constituent dimensions, such as elections, or changes in government.

Another limitation of the study concerns potential heterogeneity introduced at the individual level by traits and behaviors such as ideology, partisanship, personality, selective exposure, and cognitive biases like the Dunning-Kruger effect, among others. Future research, especially at the individual-level, should account for both systemic and individual factors and should explore different ways that the three dimensions captured by the index might move together.

The geographical scope of the study represents another limitation. Future efforts should try to expand beyond the Global North. However, the theoretical assumptions behind the inclusion of important predictors, like PBS and political parallelism, coupled with concerns about the cross-national validity of instruments used to build important measures, like the left-right scale for polarization, further complicate this endeavor.

More generally, the study raises important questions regarding the role of the press in maintaining epistemic resilience. Countries where more people report using public media every day are associated with lower EV index scores. This corroborates the notion of needing to treat information as a public service. It is still unclear whether the effect is a result of the decoupling of journalistic revenues from readership, the greater regulations imposed on PBS, or media ownership itself. Future studies should distinguish between the separate effects of license fees, journalistic norms, media regulations and full state ownership, partial ownership or private ownership. Without further evidence, the present study still suggests that decoupling revenues of journalism from readership, sound regulations, and making sure that the news media are in the hands of actors more concerned with providing information than entertainment are healthy democratic objectives.

The potential role played by newspapers in epistemic vulnerability is another important finding of this study, though the evidence is not as strong. Alternative models included in this study pinpoint newspaper parallelism as a prominent predictor of the EV index. This insight contrasts with the dominant narrative that paints newspapers as bastions of higher-quality news compared to broadcast or digital media. This narrative is highly US-centric and reveals what one could call the “Pulitzer Prize Syndrome” of journalism research, i.e., focusing on investigative journalism, highest journalistic norms, and a history of unearthing important political scandals such as Watergate. The British newspaper industry is for instance much more partisan, more frequently engaged in policy advocacy, and is far less authoritative than print press is in the US context. These two archetypal cases sit at the ends of a wide spectrum regarding content quality in the newspaper industry. Other countries generally have elements of both. Granted that the data behind this finding are older and the empirical evidence thus weaker, future comparative research should follow efforts by Chadwick et al. (Citation2018) and consider the contribution of partisan newspapers and tabloids to epistemic problems, including in countries where the newspaper industry is characterized by more mixed content.

The theoretical framework and empirical findings of this study hold crucial implications for understanding democratic health. Epistemic vulnerability should be understood as a pathology of democracy in its own right, on the same level as institutional stress or the erosion of democratic norms. Theoretically, epistemic vulnerability may be a catalyst for various democratic dysfunctions and produce a plethora of negative outcomes, both at the individual and system level. In its most extreme form, epistemic vulnerability might possibly be an antecedent of challenges to the legitimacy of democratic institutions and governance. One avenue for future research is to look at the influence of epistemic vulnerability on behavior and non-behavior, possibly through a lack of internal self-efficacy. For whom is epistemic vulnerability an impediment to political participation, and for whom is it not? Another is to study the effect epistemic vulnerability may have on various forms of political polarization, and also attitudes that are corrosive to democracy.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://10.6084/m9.figshare.25843933.

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://10.6084/m9.figshare.25843933.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (2.5 MB)Acknowledgments

The author wants to express sincere gratitude to his advisor, Professor Bruce Bimber, and Professor Heather Stoll, for their support and invaluable mentorship.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials including data and RMarkdown scripts are available in the article’s online repository.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2024.2363545

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Julien Labarre

Julien Labarre is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the Administrator of the Center for Information Technology & Society. His work focuses on political communication, disinformation, media systems, pathologies of democracy, and democratically corrosive attitudes.

References

- Aalberg, T., & Curran, J. (2012). How media inform democracy: A comparative approach. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203803448

- Aalberg, T., van Aelst, P., & Curran, J. (2010). Media systems and the political information environment: A cross-national comparison. The International Journal of Press/politics, 15(3), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161210367422

- Alcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Arceneaux, K., Johnson, M., & Murphy, C. B. (2012). Polarized political communication, oppositional media hostility, and selective exposure. The Journal of Politics, 74(1), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/s002238161100123x

- Ariely, G. (2015). Does commercialized political coverage undermine political trust?: Evidence across European countries. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(3), 438–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1055000

- Barthel, M., Mitchell, A., & Holcomb, J. (2016). Many Americans believe fake news is sowing confusion. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. http://www.journalism.org/2016/12/15/many-americans-believe-fake-news-is-sowing-confusion/

- Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network Propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American Politics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190923624.001.0001

- Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

- Benson, J. (2023). Democracy and thE epistemic problems of political polarization. The American Political Science Review, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423001089

- Bergman, E. (2018). Conspiracy & populism: The politics of misinformation. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90359-0

- Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1995). Towards a comparative framework for political communication research. In J. Blumler & M. Gurevitch (Eds.), The crisis of public communication (pp. 237). Routledge. Original work published 1975.

- Brüggeman, M., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Humprecht, E., & Castro, L. (2014). Hallin and Mancini revisited: Four empirical types of western media systems. Journal of Communication, 64(6), 1037–1065. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12127

- Castro-Herrero, L., Nir, L., & Skovsgaard, M. (2018). Bridging gaps in cross-cutting media exposure: The role of public service broadcasting. Political Communication, 35(4), 542–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1476424

- Chadwick, A., Vaccari, C., & O’Loughlin, B. (2018). Do tabloids poison the well of social media? Explaining democratically dysfunctional news sharing. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4255–4274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769689

- Christner, C. (2022). Populist attitudes and conspiracy beliefs: Exploring the relation between the latent structures of populist attitudes and conspiracy beliefs. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 10(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.7969

- Curran, J., Iyengar, S., Lund, A. B., & Salovaara-Moring, I. (2009). Media system, public knowledge and democracy: A comparative study. European Journal of Communication, 24(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323108098943

- Daniller, A. M., Allen, D., Tallevi, A., & Mutz, D. C. (2017). Measuring trust in the press in a changing media environment. Communication Methods and Measures, 11(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1271113

- Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., & Cichocka, A. (2017). The psychology of conspiracy theories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 538–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261

- Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., Kendeou, P., Vraga, E. K., & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

- Engelke, K. M., Hase, V., & Wintterlin, F. (2019). On measuring trust and distrust in journalism: Reflection of the status quo and suggestion for the road ahead. Journal of Trust Research, 9(1), 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2019.1588741

- Esser, F., de Vreese, C. H., Strömbäck, J., van Aelst, P., Aalberg, T., Stanyer, J., Lengauer, G., Berganza, R., Legnante, G., Papathanassopoulos, S., Salgado, S., Sheafer, T., & Reinemann, C. (2012). Political information opportunities in Europe: A longitudinal and comparative study of thirteen television systems. The International Journal of Press/politics, 17(3), 247–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161212442956

- Fawzi, N. (2019). Untrustworthy news and the media as “enemy of the people?” How a populist worldview shapes recipients’ attitudes toward the Media. The International Journal of Press/politics, 24(2), 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218811981

- Fawzi, N., Steindl, N., Obermaier, M., Prochazka, F., Arlt, D., Blöbaum, B., Dohle, M., Engelke, K. M., Hanitzsch, T., Jackob, N., Jakobs, I., Klawier, T., Post, S., Reinemann, C., Schweiger, W., & Ziegele, M. (2021). Concepts, causes and consequences of trust in news media – a literature review and framework. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(2), 154–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2021.1960181

- Fisher, C. (2016). The trouble with ‘trust’ in news media. Communication Research & Practice, 2(4), 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2016.1261251

- Gronke, P., & Cook, T. E. (2007). Disdaining the media: The American public’s changing attitudes toward the news. Political Communication, 24, 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600701471591 3

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing Media Systems. Cambridge University Press.

- Hameleers, M. (2023). The (Un)intended consequences of emphasizing the threats of mis- and disinformation. Media and Communication, 11(2), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6301

- Hanitzsch, T., Dalen, A., & Steindl, N. (2018). Caught in the nexus: A comparative and longitudinal analysis of public trust in the press. The International Journal of Press/politics, 23(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740695

- Hoes, E., Aitken, B., Zhang, J., Gackowski, T., & Wojcieszak, M. (2023). Prominent misinformation interventions reduce misperceptions but increase Skepticism. Nature Human Behavior, 1–116. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zmpdu

- Humprecht, E., Castro Herrero, L., Blassnig, S., Brüggeman, M., & Engesser, S. (2022). Media Systems in the Digital Age: An Empirical Comparison of 30 Countries. Journal of Communication, 00, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqab054

- Humprecht, E., Esser, F., & Van Aelst, P. (2020). Resilience to online disinformation: A framework for cross-national comparative research. The International Journal of Press/politics, 25(3), 493–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219900126

- Humprecht, E., Esser, F., Van Aelst, P., Staender, A., & Morosoli, S. (2021). The sharing of disinformation in cross-national comparison: Analyzing patterns of resilience. Information, Communication & Society, 26(7), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.2006744

- Imhoff, R., Zimmer, F., Klein, O., António, J. H. C., Babinska, M., Bangerter, A., Bilewicz, M., Blanuša, N., Bovan, K., Bužarovska, R., Cichocka, A., Delouvée, S., Douglas, K. M., Dyrendal, A., Etienne, T., Gjoneska, B., Graf, S., Gualda, E. … Žeželj, I. (2022). Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(3), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7

- Jacovina, M. E., Hinze, S. R., & Rapp, D. N. (2014). Fool me twice: The consequences of reading (and rereading) inaccurate information. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28(4), 558–568. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3035

- Kapantai, E., Christopoulou, A., Berberidis, C., & Peristeras, V. (2020). A systematic literature review on disinformation: Toward a unified taxonomy. New Media & Society, 23(5), 1301–1326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820959296

- Kohring, M., & Matthes, J. (2007). Trust in news media: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Communication Research, 34(2), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650206298071

- Krange, O., Kaltenbrorn, B., & Hultman, M. (2021). “Don’t confuse me with facts”—how right wing populism affects trust in agencies advocating anthropogenic climate change as a reality. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00930-7

- Laakso, M., & Taagepera, R. (1979). The ‘Effective’ number of parties: A measure with application to West Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 12(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041407901200101

- Labarre, J. (2024). French Fox News? Audience-level metrics for the comparative study of news audience hyperpartisanship. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2023.2300845

- Lee, T. T. (2010). Why they Don’t trust the media: An examination of factors predicting trust. American Behavioral Scientist, 54(1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764210376308

- Livio, O., & Cohen, J. (2018). ‘Fool me once, shame on you’: Direct personal experience and media trust. Journalism, 19(5), 684–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916671331

- Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. (1998). The Democratic Dilemma: Can Citizens Learn What They Need to Know? (pp. 300). Cambridge University Press.

- Marwick, A., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media manipulation and disinformation online. Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/output/media-manipulation-and-disinfo-online/

- Nechushtai, E. (2018). From liberal to polarized liberal? Contemporary U.S. News in Hallin and Mancini’s typology of news systems. The International Journal of Press/politics, 23(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218771902

- Newman, N., & Fletcher, R. (2017). Bias, bullshit and lies: audience perspectives on low trust in the media. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3173579

- Nielsen, R. K., & Graves, L. (2017). “News You Don’t Believe”: Audience perspectives on fake news. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Pillai, R. M., & Fazio, L. K. (2021). The effects of repeating false and misleading information on belief. WIREs Cognitive Science, 12(6), article e1573. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1573

- Prochazka, F., & Schweiger, W. (2018). How to measure generalized trust in news media? An adaptation and test of scales. Communication Methods and Measures, 13(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2018.1506021

- Rainie, L., Anderson, J., & Albright, J. (2017). The future of free speech, trolls, anonymity and fake news online. Internet, Science & Tech. http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/03/29/the-future-of-free-speech-trolls-anonymity-and-fake- news-online/

- Rapp, D. N. (2008). How do readers handle incorrect information during reading? Memory & Cognition, 36(3), 688–701. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.36.3.688

- Rapp, D. N., & Salovich, N. A. (2018). Can’t we just disregard fake news? The consequences of exposure to inaccurate information. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(2), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732218785193

- Rekker, R. (2021). The nature and origins of political polarization over science. Public Understanding of Science, 30(4), 352–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662521989193

- Rosenberg, S. W. (2020). Democracy devouring itself: The rise of the incompetent citizen and the appeal of right-wing populism. In D. U. Hur & J. M. Sabucedo (Eds.), Psychology of political and everyday extremisms.

- Ross, A. S., & Rivers, D. J. (2018). Discursive Deflection: Accusation of “Fake News” and the spread of mis- and disinformation in the tweets of president trump. Social Media + Society, 4(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118776010

- Schulz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D. S., Wettstein, M., & Wirth, W. (2018). Measuring populist attitudes on three dimensions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(2), 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw037

- Seymour-Ure, C. (1974). The political impact of mass media. Constable.

- Strömbäck, J., Tsfati, Y., Boomgaarden, H., Damstra, A., Lindgren, E., Vliegenthardt, R., & Lindholm, T. (2020). News media trust and its impact on media use: A framework for future research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 44(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2020.1755338

- Stroud, N. J., & Lee, J. K. (2013). Perceptions of cable news credibility. Mass Communication & Society, 16(1), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.646449

- Thorson, E. (2016). Belief echoes: The persistent effects of corrected misinformation. Political Communication, 33(3), 460–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1102187

- Tsfati, Y., Strömbäck, J., Lindgren, E., Boomgaarden, H. G., & Vliegenthart, R. (2023). What news outlets do people have in mind when they answer survey questions about trust in “media?”. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 35(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edad008

- Tsfati, Y., Strömbäck, J., Lindgren, E., Damstra, A., Boomgaarden, H. G., & Vliegenthart, R. (2022). Going beyond general media trust: An analysis of topical media trust, its antecedents and effects on issue (Mis)perceptions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 34(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edac010

- Van De Walle, S., & Six, F. (2014). Trust and distrust as distinct concepts: Why studying distrust in institutions is important. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 16(2), 158–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2013.785146

- Van Doorn, M. (2023). Advancing the debate on the consequences of misinformation: Clarifying why it’s not (just) about false beliefs. Inquiry: A Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2023.2289137

- Vecchione, M., Caprara, G. V., Caprara, M. G., Alessandri, G., Tabernero, C., & González-Castro, J. L. (2014). The Perceived Political Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (PPSE-S): A validation study in three Mediterranean countries. Cross-Cultural Research, 48(4), 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397114523924

- Wessler, H., & Rinke, E. M. (2014). Deliberative performance of television news in three types of democracy: Insights from the United States, Germany, and Russia. Journal of Communication, 64(5), 827–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12115

- Yale, R. N., Jensen, J. D., Carcioppolo, N., Sun, Y., & Liu, M. (2015). Examining first- and second-order factor structures for news credibility. Communication Methods and Measures, 9(3), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2015.1061652