ABSTRACT

This article describes the Miniature Exhibition Project, a collaborative project involving two intimate, at-home, miniature exhibitions curated by the co-author, Beatriz Asfora Galuban, for the co-author Asami Robledo-Allen Yamamoto. These miniature exhibitions were made to study disability, empathy, and friendship and were intended to reclaim and make sense of the experience of illness. This article includes details and personal reflections from The Miniature Exhibition Project and describes how the project impacted the authors’ empathy, understanding of disability, and museum practices. The article will discuss how museums are continuing to uplift ableism through programming, representation, and policies and explore how museums can cause trauma for disabled and MAD people. Finally, the authors share recommendations for applying insights from this project to mitigate ableist practice.

“Excuse me … teacher?” a student asked in a shy whisper as they came out of the bathroom. “Can you come here?” Asami was puzzled, but she walked closer to the student who was partially hiding their face with their hands and avoiding eye contact. “My wheelchair did not fit in the handicap bathroom, so I peed myself. Can you tell?” Asami froze for a moment. She quickly glanced at the student and asked them for their sweater to place on their lap. The institution where Asami was working had just undergone major remodeling, but somehow, no one had ensured that the bathrooms had enough space for a powered wheelchair or that the chairlift on the second story was functional. Therefore, during one 90-minute tour, the museum had harmed this student twice: an inaccessible bathroom and an altered tour route around the broken chairlift. Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident, but instead an example of the ways accessibility is undervalued in museums. These incidents illuminate museum ableism and display underlying psychological biases against disabled and Mad people.Footnote1

As a disabled person, Asami found herself wondering: how was she supposed to comfort the student, when the situation was entirely the institution’s fault? Why was accessibility in her museum an afterthought when it should be a priority – especially when that museum offers “Access” programs? Chris Bell, a Black disabilities studies scholar, states, “Disability is, arguably, the only identity that one can acquire in the course of an instant.”Footnote2 Disabilities are not to be feared, nor do they mark the end of normality, so how can museums normalize inclusion of all bodies?

In the Spring of 2019, two friends, Asami Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, a disabled museum educator, and Beatriz Asfora Galuban, an art education doctorate student, collaborated on the Miniature Exhibition Project (MEP), which re-imagined the museum space and educational programming as something that could take place outside the museum. The MEP included two miniature exhibitions installed for four weeks each on Asami’s bedroom bookshelf, accompanied by journaling. Throughout the project, Asami and Beatriz discovered how the MEP deconstructed ableist boundaries in museum buildings and educational programming while using empathy and friendship as theoretical frameworks. In this paper, they use reflections from the experiment to critically analyze the limitations of museums, deconstruct traditional museum education practices, and challenge ableist roots and structures, while arguing that museums must center the voices of disabled people and anchor their practice in empathy.

The authors’ perspectives

The authors center their perspectives as chronically ill museum educators and a museum academic with anxiety. Both authors have been challenged and disappointed by the ableist pillars that uphold museums. Common failures, such as the lack of working chair lifts, mandatory walking during tours, the lack of accessibility resources and training for museum educators, and requirements that students should sit on the floor during tour stops, are acts of violence against the disabled and Mad visitors in museums. Those failures make visitors feel unwelcome, unseen, and unimportant. Coming to a museum should never be traumatic, yet it regularly is.Footnote3

During the timeframe of the MEP, Asami did not identify as disabled. It took years for Asami to identify as a disabled person. Eventually, her chronic illnesses started limiting her ability to eat, to keep plans, work, or function. She finally understood her body needed extra help to perform daily tasks. However, it was not until she saw her illnesses listed on a “Self-Identification of Disability” form for a job application that Asami finally started acknowledging her disabled body. Her previous definition of “disabled” had been constructed by popular culture portrayals of disabled people, limiting the term to refer only to people who use mobility assistance devices and/or people with visually apparent disabilities and/or illnesses. Seeing her illnesses listed and defined by a workplace application, months after the MEP project, changed her thinking and evolved her definition of disabled.

The word “disabled” has diverse legal and personal definitions. For this paper, “disabled” is defined as someone who experiences, or is perceived as experiencing, a physical, mental, psychological, or emotional condition that impacts their day-to-day experiences. The conditions may require therapeutic attention(s), accommodation(s), modification(s), or assistance(s); they may be apparent or non-apparent. “Disability” is a social construct built by the barriers experienced in one’s physical or conceptual environment. Human design decisions, such as accessible bathrooms, shortened meetings, availability of sick days, etc., determine the level of accessibility and can determine the intensity of one’s experience of disability.Footnote4 The authors acknowledge that the definition proposed does not encompass all experiences, and, in many cases, Mad people and/or people with a mental illness do not necessarily identify as disabled. However, we agree with art educator Dr. John Derby’s idea that the mind is not separate from the body, so we use “disabled” to include Mad people. Lastly, the authors note that our definition of disability is not meant to be written in stone – it is a living definition, ebbing and flowing along with one’s relationship with disability, evolving with our experiences.

The Miniature Exhibition Project

The earliest precursor to the modern museum, the fifteenth-century Wunderkammern, housed many collections of oddities and wonders displayed in the homes of wealthy nobles.Footnote5 This tradition continues in private collections of artworks exhibited in homes, offices, and hotels. Today, people can experience similar private displays by hanging photographs on their walls and displaying trophies on shelves, as if homes were personal museums. In the spirit of exploring personal museums, Beatriz created the idea of the Miniature Exhibition Project (MEP). The MEP included two miniature exhibitions that Beatriz installed on Asami’s bookshelf over the span of three months. The exhibitions were inspired by The Micro-Museum and Library,Footnote6 as well as Orhan Pamuk’s Modest Manifesto for Museums.Footnote7 Beatriz began the MEP with one question: what does it look like for exhibitions or museums to exist inside our homes? The intent to explore disability was not originally in the project’s plan, but became an important theme as Asami’s reflections and interactions were affected by her health and disabilities. During much of the project, Asami was physically limited by her disabilities and was unable to visit a museum or participate in traditional museum educational programming. Therefore, the MEP served as her own museum, one she could interact with from her bed, creating, for Asami, a perfectly accessible museum.

The MEP was an intimate experience for the two authors that led throughout to deeper understanding of one another’s experiences. Because of this, empathy and friendship became the theoretical frameworks of the project. Empathy is not new to museum education, but the authors argue that it belongs at the forefront of conversations about disability and access. Roman Krznaric, philosopher and founder of the world’s first Empathy Museum, defines empathy as “the art of stepping imaginatively into the shoes of another person, understanding their feelings and perspectives, and using that understanding to guide your actions.”Footnote8 This combines aspects of affective and cognitive empathy to illustrate that empathy encompasses a mirroring of another person’s emotions and a cognitive understanding of someone else’s experience. It acknowledges that one’s concerns and feelings are different from others. This acknowledgment was a guiding principle of the project, as Beatriz’s prompts and curation of the miniature at-home exhibitions considered Asami’s movement due to her illnesses. Friendship, although more commonly found in qualitative narrative research, served as another important framework in the project. According to narrative researcher Lisa Tillman-Healy, friendship involves being in the world with others. It includes an interpersonal bond characterized by ongoing communication.Footnote9 Friendship supports the empathetic and caring framework, as both educators highlighted the ableist structures in museums throughout the project. Elif Gokcigdem, founder of the initiative Empathy-Building Through Museums, asserts that much of the scholarship on museums and empathy shows that museums are also platforms where safe and informal learning can take place.Footnote10 This empathetic approach to education is vastly significant as both authors contemplate programming for all bodies inside museum spaces.

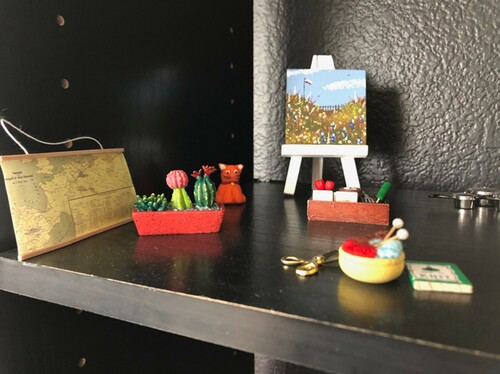

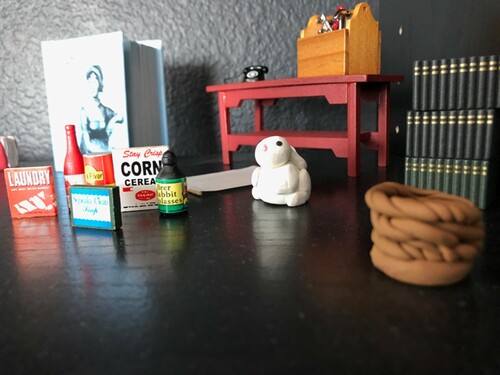

Creating the MEP exhibitions included three major phases: establishing the concept, preparing the installation, and, for Asami, living with the exhibition and reflecting on it. Beatriz’s concept for Exhibition One stemmed from a desire to share a part of her life with Asami. Exhibition One (shown in and ) was curated from Beatriz’s personal collection of toy miniatures, which told her personal story as a collector. The installation process took no more than an hour and included Asami and Beatriz having lunch together, helping their relationship grow. The installation was complemented by personal curatorial statements written in the form of letters to Asami, asking her to participate in the exhibition creatively by modeling some of her own objects out of clay. Asami’s participation was limited during the exhibition. Asami felt unable to create miniature objects throughout; therefore, Exhibition One did not yield creative results or written reflections. However, the exhibition created a mode of communication for both authors, as they re-scheduled multiple times to remove and install new exhibits on Asami’s bookcase. The scheduled installation and deinstallation dates were interrupted by changes in scheduling and trips to doctors. Therefore, the projects’ installations had to accommodate Asami’s illnesses. The deinstallation of Exhibition One was done by Beatriz after four different scheduling attempts. Exhibition Two was rapidly installed on the same day. Despite the rescheduling, both exhibits were able to run for their planned four weeks. The back-and-forth rescheduling enabled Beatriz to get to know Asami, her disabilities, and how she might want to interact with the next exhibition.

Figure 1. The left half of Exhibition One curated by Beatriz for Asami.

Figure 2. The right half of Exhibition One curated by Beatriz for Asami.

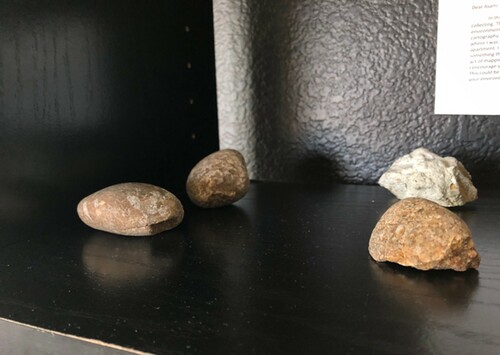

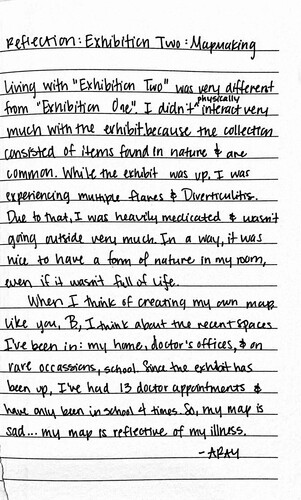

Beatriz’s reflections from the process of Exhibition One stemmed from a place of empathy, as she thoughtfully considered how else she might connect with Asami and invite her to participate.Footnote11 The concept for Exhibition Two was simple, and the objects themselves took secondary place to the reflections Beatriz invited Asami to partake in. Exhibition Two (shown in and ) included a collection of small rocks, leaves, pinecones, and twigs collected on Beatriz’s walk across campus of The University of North Texas. In this exhibit, Beatriz mapped her story through the curation of objects from her walk. Inside a miniature journal, originally part of the first exhibition, Beatriz invited Asami to interact with the objects by considering the places she had been and by creating her own map of objects. Asami’s reflection (shown in ) expresses the depth of emotions and connections she felt while interacting with the exhibition. Asami bonded with the collection of dead objects from nature because of how she felt spending most of her time in bed or doctor’s offices.Footnote12 Reading Asami’s reflections was eye-opening for Beatriz as a researcher, curator, and friend. The exhibition allowed both Asami and Beatriz to approach objects as vehicles for stories. This exhibition made the authors consider walking, time, and space, and their places in traditional museum education. Exhibition Two challenged Beatriz’s own preconceived notions of what it meant to curate and facilitate educational programs. The objects were not the focus but rather the authors’ experiences and what they learned. Using a constructivist approach, Asami related the items to her illnesses in a way that Beatriz did not expect. Additionally, Exhibition Two enabled both authors to reflect on the ableist structures inherent to museum programming that come from time, the physical limitations of the museum building, and the harmful barriers programming can pose to disabled bodies.

Figure 3. The left half of Exhibition Two curated by Beatriz for Asami.

Figure 4. The right half of Exhibition Two curated by Beatriz for Asami.

Figure 5. A scanned image of Asami’s reflection in response to the mapping prompt in Exhibition Two.

While Asami and Beatriz believe that museums are essential community spaces for learning, most structural museum buildings and limited accommodations can be damaging to disabled and Mad bodies. For these reasons, the authors hold a critical position on museums as places often governed by physical limitations and ableist privilege.Footnote13 The MEP exhibitions offered a reclaiming of what museums could be if they existed inside individual homes. The exhibits and the reflection processes enabled Asami to make meaning of her own story as a disabled person and museum program participant. As the MEP came to an end, both authors questioned whether traditional museum programming adequately allowed space for this kind of honest and vulnerable reflection and considered the harmful limitations caused by ableist museum buildings and programming structures. While, regrettably, museum educators cannot feasibly recreate the MEP for all museum visitors, there were many takeaways and lessons learned about ableism that may apply to traditional museum practices.

Traditional ableist museum structures and practices

The MEP revealed ableist structures inherent in museum buildings and programs and modeled what accessible programming could look like by tinkering with ableist constraints in museum programming: movement, pacing, artwork proximity, and threshold fear. How do museum educators combat these constraints? For Asami, physically moving from one location to another can be a daunting and impossible task on some days. During the MEP, her bed was right next to the bookshelf the exhibitions were on; the requirement of mobility was subtracted from the museum experience. During the MEP, Asami could interact with the exhibition as slowly as she wanted; pacing was subtracted from the museum experience. During the MEP, the entire exhibition was miniature and in one bookcase; artwork proximity was subtracted from the museum experience. Her interactions were based on her abilities of the day in her space; threshold fear was subtracted, and freedom was added to the museum experience. How can museum educators give this freedom to themselves and museum visitors on a tour? How can museum educators transform traditional ableist tour structures to be inclusive and accommodating? The authors have explored alternatives to the visual consumption of museum experience through these modalities, reformatting, slow looking, and reflection.

Until a few decades ago, museum architecture in major cities was often inspired by classical Ancient Greek and Roman temple architecture, with rows of columns on raised plinths and numerous cement steps leading up to grand, wide-open entryways, guarded by tall, heavy museum doors. Oftentimes, accessibility ramps are built to the side of these majestic entrances, as if they take second priority. Some museums even claim the protection of historical architecture preservation standards to avoid following ADA laws, making part or all of those buildings fully inaccessible. Once in the galleries, floor plans are often physically demanding, with spaces typically spanning numerous large rooms and hallways filled with artworks and an overflow of information. The design and architecture of museums create many limitations for disabled bodies entering the space.

Elaine Heumann Gurian, consultant, author, and museum advisor, describes the concept of “threshold fear,” meaning “the constraints people feel that prevent them from participating in activities meant for them.”Footnote14 An example of threshold fear in the museum occurs whenever disabled people do not want to participate in current museum access programs. Regardless of the programs being made for disabled people, participants may not want to participate in the programs for a plethora of reasons, including intimidation, othering, imposter syndrome, etc.Footnote15 Our attempt to combat threshold fear was to bring a museum program and an exhibition inside Asami’s home, allowing her to interact and engage with works of art without the physical limitations of the museum floor plan and structural design. By doing away with threshold fear, we were able to re-imagine museum programming as an intimate and individual experience that could happen outside the museum walls and inside our very own homes.

Museum educators have deconstructed movement, pacing, artwork proximity, and threshold fear through virtual programming. The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic forced many programs to be facilitated successfully outside of the museum’s walls and in the comfort of visitors’ safe spaces. Both the pandemic accommodations and the MEP revealed that museum education could be experienced from one’s own home, removing many ableist barriers present in traditional museum education programming. Beatriz and Asami have both participated in and facilitated virtual museum programs. As both virtual program participants or facilitators and during the MEP, the authors felt freer to engage with the exhibitions through their own stories and interpretations during virtual tours, 3D museum walkthroughs, and pre-recorded programs. The Canadian Clay and Glass Museum in Waterloo, Ontario, re-situated their well-known children’s program, “Play with Clay” to an at-home online platform titled “Play with Clay at Home.” In this program, participants have the option of ordering a special kit containing glaze colors, clay, and small plastic tools.Footnote16 The gallery also created instructional videos to follow along and create masterpieces from home. Also, they have the option to send clay projects back to the gallery for a final firing in the kiln. This program was implemented during the pandemic when social distancing guidelines limited the number of participants in the studio and gallery space. While this alternative format served the community during the pandemic, it is an example of how museum learning and creating works of art are possible in an intimate at-home setting. This change made the program more accessible. This illustrates what Orhan Pamuk says about museums: “The success of museums should not be measured by the number of tickets sold, but by their ability to reveal the humanity of individuals.”Footnote17 Pamuk argues that for this to occur, museums must become smaller, more individualistic, and cheaper, allowing them to tell stories on a human scale. He states, “the future of museums is inside our own home.”Footnote18 The authors discovered that museums do not need big temple-like buildings, nor do they need big flashy exhibitions that require quick walking and rushed reading of curatorial texts. Museums can be experienced on an intimate scale that is both meaningful and inclusive for all.

One of the most-used program formats, multiple-stop tours, upholds ableism due to the time restrictions and the nomadic structure. The format involves traversing across a museum to cover as much of the building and artwork as possible in a short amount of time. Relying on the museum building as the primary setting, moving at a specific pace, and staying within time constraints can be harmful and traumatizing to disabled and Mad people who participate and facilitate this style of programming. In this fast-paced process, facilitators are more focused on moving quickly through the tour rather than on the harm that space and time constraints may impose on the participants.Footnote19 Educators must also be mindful of their rhythm and speed in the galleries to avoid tour traffic jams with other educators or visitors. An educator’s goal should not be rushing to meet stops; it should be facilitating the relationship between the artwork and the students or tourgoers. Transitions between stops can be very intimidating and shameful to disabled bodies, especially when crip times vary.Footnote20 How do we take these common ableist practices and make them accessible for disabled and Mad visitors?

Authors’ final thoughts: Promoting anti-ableist practices in your museum

While accessibility is often mentioned in museum’s missions, in practice, it often falls short. Access programs are successful at creating a home in museums for certain disabled visitors, but typically only on scheduled occasions, as rarely as once a month. Disabled people are not accommodated outside of those specific programs. Sixty-one million adults in the United States have a disability.Footnote21 In addition, nearly fifty-three million adults have a mental illness.Footnote22 These numbers mean that one out of four visitors to walk into a museum may benefit from accommodations. How can museum educators truly accommodate disabled visitors during all museum visits? How can museum educators help and advocate for disabled visitors to feel as if the museum is prepared for them and welcomes them? The MEP deconstructed many of the ableist barriers present in on-site museum education. Recognizing that the MEP is not feasible to recreate for every museum visitor, the authors suggest the following adaptations: using a specific tour format, developing accessibility tool kits, practicing a specific teaching methodology, advocating for more museum seating, using anti-ableist language, and ensuring an accurate representation of disabled and Mad bodies.

To combat the ableist boundaries of multiple-stop tours, the MEP advocated for more stationary, open-ended, meditative drop-in experiences, prioritizing flexibility instead of prioritizing time. Drop-in experiences are free of time constraints and promote flexibility based on visitor interest and individual pacing. To be most accessible, museum educators should consider drop-in experiences written using seventh-grade level vocabulary and offering optional pre-recorded auditory artwork descriptions and activity instructions that can be paused or slowed down. In addition to the recordings, written visual descriptions, social narratives, and instructions written in dyslexia-friendly font (such as OpenDyslexic or Dyslexie) should be offered to participants.Footnote23

In traditional school settings, disabled students may have an Individualized Education Program (IEP), which specifies tools to help the student succeed.Footnote24 On museum field trips, oftentimes, museum educators are not privy to this helpful information, which sometimes leaves students feeling unprepared and frustrated. Educators Mari Beth Coleman and Elizabeth Stephanie Cramer explain that assistive technologies (ATs) used in the classroom setting range from four different levels (no, low, middle, and high technology) and can be anything that helps a student perform a task, such as increased time to complete an assignment, large-handle paint brushes, or specialized computer software.Footnote25 Other tools museum educators should have available include a printed alphabet with American Sign Language signs, large-diameter pencils, and quiet fidget tools. To increase vision access, museum educators should consider handheld magnifying glasses, large-print reproductions of wall labels, visual descriptions of artworks explored on tour, and LED book lights to illuminate paper handouts, labels, and materials. For artmaking activities, offer accessible supplies such as glue dots, grip-free paintbrushes, and/or Easy Action™ scissors. The more resources available, the more creativity and freedom participants can experience during a program.

Facilitation methods can influence how welcomed a visitor feels in the museum. Studies have shown that visitors spend, on average, 28.63 seconds per artwork.Footnote26 Slowing down allows the facilitator and visitors to create new relationships with the artwork and reduces time constraints. Lecturer and education researcher Shari Tishman states “Slow looking … means taking the time to carefully observe more than meets the eye at first glance.”Footnote27 Tishman explains that looking refers to sensory observation, extending beyond sight, and includes multi-sensory experiences, which enrich museum visits by evoking visitors’ memories and creating long-lasting impressions.Footnote28 Slow looking also allows educators time to provide an auditory-visual description, making the experience accessible to people who are blind or are partially blind.Footnote29

During the MEP, Asami had the option of sitting in her bed, on a nearby couch, or on the floor to enjoy the exhibitions, which made the time she spent with the exhibition nearly painless. However, when walking through museum spaces, the number of benches or seats can be scarce, which can cause pain, discomfort, feelings of inadequacy, and embarrassment. Limiting the number of benches available eliminates a very useful tool. There are many reasons why sitting is viewed as inappropriate in a museum setting, including following social distancing guidelines, valuing gallery aesthetics, or discouraging loitering and conversations. To not offer enough seating, though, is to assume that there is only one physical way to look at and engage with art: standing. Sitting does not mean weakness nor difference. Gallery benches not only encourage spending a longer time observing the art, but they also help visitors practice slow looking. Sitting can benefit all bodies, but especially disabled bodies, by providing a place of rest, peace, mediation, and comfort.Footnote30 An alternative to sitting is lying down. Disabled artist Raquel Meseguer explores coping with chronic pain through laying down in gallery spaces. She states that this

… re-imagine(s) how people use buildings and move through (your) exhibits and programs with places to rest along the way. I would argue that all art would benefit from the means to linger. I know I have a very different relationship to the pieces I have rested with, they are imprinted in me in a different way.Footnote31

Traditionally, stories of disabled and Mad bodies are omitted from museums, or they may even be romanticized, like that of Van Gogh.Footnote32 Narratives often do not highlight the disabilities of artists such as Michelangelo, who was rumored to have neuropathy, or Henri Matisse’s cancer diagnosis, nor do they mention Frida Kahlo’s polio or pelvic injuries, Monet’s depression, or Jackson Pollock’s alcohol addiction. This creates an inaccurate representation and false narrative of disabled or Mad people. Representation starts with identifying the artists as the people they really were/are, not with a romanticization of disability and/or of mental illness; there are no tortured artists, nor are all disabled/Mad people the subject of inspirational stories about overcoming adversity. The publication Rethinking Disability Representation in Museums and Galleries states, “the way disabled people have been portrayed is degrading and dehumanizing, which is a contributing factor to the disenfranchisement of disabled people.”Footnote33 Disability representation starts with dismantling those stereotypes and creating a counternarrative by normalizing disabilities in artists and our conversations around these artists that might take place in the gallery. While destigmatizing disabilities and mental illness, it is also critical to practice using anti-ableist language. This includes eliminating phrases such as: “that’s crazy;” “suffering from a disability;” or using “special” when referring to disabled people. This is the opportunity to empower disabled and Mad people through everyday language.

The Miniature Exhibition Project deconstructed museums and revealed multiple ways in which Beatriz and Asami could approach anti-ableist museum education through an inclusive and empathetic lens and re-imagined museums as spaces that existed inside of homes. The framework of empathy and friendship enabled both educators to approach museum education from a place of care when considering each other’s illnesses and limitations. Museum educators must be mindful of how current museum practices can be ableist and strive to challenge those pedagogies and acknowledge the harm they cause to disabled bodies. With an empathetic teaching philosophy, resources, slow looking, inclusive engagement, and representation of disabled and Mad bodies, museum educators can start deconstructing the ableist pillars upholding museum spaces and practices and, therefore, empower the voices of disabled visitors and educators. By doing so, visitors, like the student in the introduction and Asami, will begin to find a home in museums.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Asami Robledo-Allen Yamamoto

Asami Robledo-Allen Yamamoto is a physically disabled Latina who currently serves as the Bilingual and Community Program Coordinator for an art museum in Texas. She is responsible for bilingual programming for children five and under, translates education programs, and is the coordinator of all access programs and resources, such as programs for adults with cognitive disabilities such as Alzheimer’s and Dementia and constructing and facilitating tours for visitors who are blind or partially blind.

Beatriz Asfora Galuban

Beatriz Asfora Galuban is a university adjunct instructor for courses in art history and art education at the University of North Texas and Texas A&M University, Commerce. Her research focuses on narrative interpretation, personal experience, and museum programming for individuals with anxiety disorders as well as empathy programming for pre-med and nursing students. Beatriz has a Ph.D. from the University of North Texas with a certification in art museum education.

Notes

1 According to Critical Disability Studies, identifying as Mad can include people who have been labeled as having a mental illness and/or neurological deficit.

2 Bell, Blackness and Disability.

3 The examples of traumatic experiences listed include some but not all the ways in which museums reinforce ableism. Other examples include: limiting writing utensils in the galleries to golf pencils; forcing participation/interactions during tours from all visitors; othering visitors with mobility assistance devices (such as wheelchairs, walkers, etc.) by making them take alternative routes (limiting the art they can enjoy) due to lack of ADA compliance; and not providing subtitle options when releasing videos to the public. We acknowledge that this list still does not encompass all the ways in which museums have harmed Mad or disabled visitors. We hope that this article will allow museum workers to reflect and identify any harmful and ableist practices.

4 Derby, “Disability Studies and Art Education.”

5 Rodini, “A Brief History of the Art Museum.”

6 “The Bookcase,” The Bookcase: Micro-Museum and Library; The Micro-Museum and Library was a miniature bookcase museum featuring rotating exhibitions and programming by different curators, faculty, and students from the University of Western Ontario’s visual arts department.

7 Pamuk, “A Modest Manifesto for Museums.” Orhan Pamuk, novelist and founder of the Museum of Innocence, outlines his hopes and arguments for the future of museums in the form of a manifesto containing 11 tenets that argue for the museum to become smaller and to tell stories of humanity. Some of these suggestions were applied to the MEP, such as the tenet 1, “The stories of individuals are better suited for displaying our humanity,” along with 6, “It is imperative that museums become smaller and more individualistic, and cheaper in order to tell stories on a human scale.” The MEP attempts to re-imagine the museum as miniature exhibitions that tell stories and invites reflection on a personal, human level.

8 Krznaric, Empathy: Why It Matters and How to Get It.

9 Tilliman-Healy, “Friendship as Method.”

10 Gokcigdem, Fostering Empathy Through Museums.

11 To imagine the experience of another person as different from one’s own requires a great deal of empathy, to consider not only care for the participant, but how they might feel whether in a museum program or a miniature exhibition project. Empathy was not only important for this project but for museum education as a whole. It enables educators to acknowledge and understand the limitations of the museum space, their programs, and themselves as they create programs for various audience members.

12 Constructivism allows visitors in a museum setting to build on their prior experiences to create new meanings through a questioning strategy that is open-ended and relatable for all visitors.

13 Duncan, Civilizing Rituals.

14 Rodini, “Looking at Art Museums.”

15 Access programming typically offered in museums includes programs for participants with dementia, Alzheimer's, and/or Autism. Such programs are often offered a small number of times in a calendar cycle. While specific programs for disabled participants are valuable and irreplaceable, the pedagogical tools and practices used in those access programs should be applied to all programs, including, and not limited to, docent-led tours, school programs, and any public programs.

16 “Play with Clay at Home,” Play with Clay at Home, Canadian Clay, and Glass Gallery.

17 Pamuk, The Innocence of Objects.

18 Ibid.

19 With this layout, museum educators are constrained by time to complete their designed lesson, which can be argued is not real art education but instead a regurgitation of tours previously conducted.

20 Ellen Samuel’s, a disability studies professor, essay Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time, explains that crip time means, “bending the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds rather than bending disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock.”

21 “Disability Impacts All of Us Infographic.”

22 “Mental Illness.”

23 Dyslexia-friendly font refers to a typeface that is designed to be more legible for dyslexic people.

24 The authors want to note that even if a student has an IEP to better support student learning, IEPs do not represent nor define who the student is or their abilities.

25 Coleman and Cramer, “Creating Meaningful Art Experiences.”

26 Smith, Smith, and Tinio, “Time Spent Viewing Art, and Reading Labels.”

27 Tishman, Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation.

28 Wang, “Museum as a Sensory Space.”

29 Visual descriptions are very detailed readings of a work of art for visitors who are blind or are partially blind. The descriptions are auditory maps of artworks. Descriptions may be accompanied with music, textiles, scents, three-dimensional printings of artwork, and other sensory resources to best support the accessibility of the artwork.

30 Whitemyer, “Where the Seats Have No Name.”

31 Wheatley, “Dreaming of Resting Spaces.”

32 Tate, “Van Gogh – Challenging the ‘Tortured Genius’ Myth.”

33 Dodd et al., Introduction: Rethinking Disability Representation.

Bibliography

- Bell, Christopher, ed. Blackness and Disability: Critical Examinations and Cultural Interventions. Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2010.

- Beresford, Peter. “‘Mad,’ Mad Studies and Advancing Inclusive Resistance.” Disability & Society 35, no. 8 (2020): 1337–1342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1692168.

- Berne, Patricia, Aurora Levins Morales, David Langstaff, and Sins Invalid. “Ten Principles of Disability Justice.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 46, no. 1 (2018): 227–230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2018.0003.

- British Dyslexia Association. “Dyslexia Style Guide 2018: Creating Dyslexia Friendly Content.” Last modified 2018. https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide.

- Coleman, Mari Beth, and Elizabeth Stephanie Cramer. “Creating Meaningful Art Experiences with Assistive Technology for Students with Physical, Visual, Severe, and Multiple Disabilities.” Art Education 68, no. 2 (2015): 6–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2015.11519308.

- Derby, John. “Disability Studies and Art Education.” Studies in Art Education 52, no. 2 (2011): 94–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2011.11518827.

- “Disability Impacts All of Us Infographic.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html#:~:text=26%20percent%20(one%20in%204,Graphic%20of%20the%20United%20States.

- Dodd, Jocelyn, Richard Sandell, Debbie Jolly, and Ceri Jones, eds. Rethinking Disability Representation in Museums and Galleries. Leicester: Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, 2008.

- Duncan, Carol. Civilizing Rituals. London: Routledge, 1995.

- El-Amin, Aaliyah, and Cohen Correna. “Just Representations: Using Critical Pedagogy in Art Museums to Foster Student Belonging.” Art Education 71, no. 1 (2017): 8–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2018.1389579.

- Frank, Arthur W. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Gocigdem, Elif. Fostering Empathy Through Museums. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016.

- Gurian, Elaine, ed. Civilizing the Museum. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Keifer-Boyd, Karen, Flávia Bastos, Richardson Jennifer (Eisenhauer), and Wexler Alice. “Disability Justice: Rethinking ‘Inclusion’ in Arts Education Research.” Studies in Art Education 59, no. 3 (2018): 267–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2018.1476954.

- Krznaric, Roman. Empathy: Why It Matters and How to Get It. New York: Perigee Press, 2015.

- “Mental Illness.” National Institute of Mental Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed April 18, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness#:~:text=Mental%20illnesses%20are%20common%20in,(52.9%20million%20in%202020).

- Pamuk, Orhan. The Innocence of Objects. Translated by Ekin Oklap. New York: Abrams, 2012.

- Pamuk, Orhan. “A Modest Manifesto for Museums.” In The Keeper, edited by Massimiliano Gioni and Natalie Bell, 277–279. New York: New Museum, 2016.

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018.

- Play with Clay at Home, Canadian Clay, and Glass Gallery. “Play with Clay at Home.” Accessed January 9, 2022. https://www.theclayandglass.ca/programs-and-events/at-home-programs/play-with-clay-at-home/.

- Rodini, Elizabeth. “1. A Brief History of the Art Museum.” Last modified June 1, 2019. https://smarthistory.org/a-brief-history-of-the-art-museum/.

- Rodini, Elizabeth. “Looking at Art Museums.” Smarthistory. Last modified May 31, 2019. https://smarthistory.org/looking-art-museums/.

- Samuels, Ellen. “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time.” Disability Studies Quarterly 37, no. 3 (2017). doi:https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v37i3.5824.

- Smith, L. F., Jeffery K. Smith, and Pablo P. L. Tinio. “Time Spent Viewing Art and Reading Labels,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 11, no. 1 (2017): 77–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000049.

- Start Standing: Sitting Is the New Smoking. “Resources.” Last modified May 9, 2021. https://www.startstanding.org/sitting-new-smoking/#para1.

- Tate. “Van Gogh – Challenging the ‘Tortured Genius’ Myth.” Posted on May 10, 2019. YouTube video, 3:48. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFqAKp6xmLg.

- Tilliman-Healy, Linda. “Friendship as Method.” Qualitative Inquiry 9 (2003): 729–749.

- The Bookcase: Micro-Museum and Library. “The Bookcase.” Accessed January 2, 2022. https://bookcasemicmuseum.wordpress.com/.

- Van der, Kolk, and A. Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books, 2014.

- Wang, Siyi. “Museum as a Sensory Space: A Discussion of Communication Effect of Multi-Senses in Taizhou Museum.” Sustainability 12, no. 7 (April 2020): 3061. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su12073061.

- Wexler, A., and John Derby. “Art in Institutions: The Emergence of (Disabled) Outsiders.” Studies in Art Education 56, no. 2 (2015): 127–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2015.11518956.

- Wheatley, T. “Dreaming of Resting Spaces, and Making Them Happen.” Disability Arts International, October 17, 2019. https://www.disabilityartsinternational.org/resources/dreaming-of-resting-spaces-and-making-them-happen/.

- Whitemyer, David. “Where the Seats Have No Name: In Defense of Museum Benches.” Exhibitions (Blog), American Alliance of Museums, October 19, 2018. https://www.aam-us.org/2018/10/19/where-the-seats-have-no-name-in-defense-of-museum-benches/.

- Wong, Alice, ed. Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century. New York: Penguin Random, 2020.