Abstract

The study of identities struggles to capture the moments and dynamics of identity change. A crisis moment provides a rare insight into such processes. This paper traces the political identities of the inhabitants of a region at war – the Donbas – on the basis of original survey data that cover the four parts of the population that once made up this region: the population of the Kyiv-controlled Donbas, the population of the self-declared “Donetsk People’s Republic” and “Luhansk People’s Republic,” the internally displaced, and those who fled to the Russian Federation. The survey data map the parallel processes of a self-reported polarization of identities and the preservation or strengthening of civic identities. Language categories matter for current self-identification, but they are not cast in narrow ethnolinguistic terms, and feeling “more Ukrainian” and Ukrainian citizenship include mono- and bilingual conceptions of native language (i.e. Ukrainian and Russian).

Introduction

The recent political developments in Ukraine – mass protests, regime change, and war – widen the relevance of this case for theorizing about change and continuity of identities and cleavages. Ukraine’s regional diversity is rooted in a mixture of ethnic, linguistic, socioeconomic, historical, and political factors that make the country a prime case for the study of identities and political cleavages. Scholars with an interest in Eastern Europe have long debated the relative importance of individual cleavages (e.g. Bremmer Citation1994; Arel Citation1995, 2002, 2014; Holdar Citation1995; O’Loughlin Citation2001; Barrington Citation2002; Hale Citation2004; Lushnycky and Riabchuk Citation2009; Sasse Citation2010; Frye Citation2015). War and displacement are synonymous with the disruption of the daily lives of individuals experiencing them. War puts the parameters, meaning, and salience of identities to an extreme test. Dynamics that otherwise may tend to evolve gradually, may suddenly intensify and accelerate.

Three years after the onset of the war in the Donbas, the number of the war dead in Ukraine lies above 10,000. The Minsk I and II agreements of 2014 and 2015, brokered by the Normandy Four (Germany, France, Ukraine, and Russia) have contained but not stopped the fighting. The frontline has cut the historical region of Donbas, used as a shorthand to describe Donetsk Oblast and Luhansk Oblast, into two parts. The self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (hereafter referred to in short as DNR/LNR), supported by Russia, include the regional capital cities Donetsk and Luhansk. The war now appears to be in an unstable stalemate that is pulling the two parts of the Donbas increasingly apart. On the one hand, the integration of the DNR/LNR into Russia’s political, economic, and security structures is progressing apace, for example, through the distribution of Russian passports, the introduction of the ruble as the local currency and renationalization of enterprises, and Russian coordination of security. On the other, the Ukraininan Government, through some measures, is actively excluding the territories from its sovereign space in a calculation to increase the costs of the war for Russia. Access to social security payments has been difficult for the population in the DNR/LNR, and representatives of Ukrainian political parties have enforced a blockade of coal shipments from the occupied territories, which Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko was forced to endorse as government policy.

The question this article asks is whether the increasing physical and political distance between the two parts of the Donbas – the part controlled by Kyiv and by the DNR/LNR – is reflected in the local population’s identities and attitudes. By covering the entire Donbas region rather than just the part controlled by Kyiv, the survey provides a rare glimpse of the perceptions of people in the occupied territory and thereby allows for a comparative examination of attitudes and identities across the frontier.

One group severely affected by the war remains hidden from view: the internally and externally displaced. By summer 2016, the Ukrainian Ministry for Social Policy had registered close to 1.8 million internally displaced people (IDPs) inside Ukraine (http://en.interfax.com.ua/news/economic/351907.html). Since 2015 Ukraine has been among the 10 countries with the largest IDP population worldwide (http://ec.europa.eu/echo/what-we-do/humanitarian-aid/refugees-and-internally-displaced-persons_en). Moreover, about another one million have fled from the conflict zone to the Russian Federation (http://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/UNHCR%20Ukraine%20Operational%20Update%20-%20December%202016.pdf).

Through their displacement, these individuals fall outside standard opinion polls, they do not figure in international media reports (and hardly figure in the Ukrainian and Russian media), and in policy circles they are primarily seen as a social policy or humanitarian aid issue. The overall number, territorial spread, and their extreme experiences make the displaced a constituency that the Ukrainian and Russian national and local governments – as well as the West more generally – need to take into account in efforts to resolve the conflict. The displaced are politicized, though not one cohesive political or social force. Many remain dependent on state or family support, while remaining in close contact with the areas and people they left behind. They are also an extreme case to test how the experience of war shapes attitudes and identities.

A four-part original survey conducted in late 2016 by the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) is at the heart of this article. The four surveys focused on the population of the Kyiv-controlled Donbas region (Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts), the population of the self-declared “People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk,” the internally displaced inside Ukraine, and those who fled from the war zone to Russia. The four surveys had aligned questions that treated the currently disjointed parts of this region as a single political space. The emphasis is on the population’s self-reported identities and the similarities and differences among the four constituencies.

Respondents were asked to evaluate their identity now compared to five years ago to allow a measure of temporal comparison. Moreover, the survey contributes to the more general discussion about the polarization of identities during conflict. If we find a more complex picture than overarching polarization at a moment of crisis – for which we cannot say with certainty if it was brought on by the war or was latent or active beforehand – we can caution against the predominant assumption of polarization of identities and radicalization during war.

The article has two main aims: first, it takes stock of the micro-foundations of self-reported identities of those most directly affected by war, and second, it engages with the as yet empirically underexplored hypothesis from the conflict literature on escalation and polarization of identities during war. The new data demonstrate a dual trend: while there is some polarization of self-reported identities, mixed or civic identities are also being preserved or even strengthened. Self-identification as a Ukrainian citizen, arguably the most civic political identity, is clearly associated with native language (and, to some extent, language use at home), but interestingly with both Ukrainian native language and mixed Ukrainian–Russian native language. The identity “Ukrainian citizen” is clearly not a linguistically exclusive category but explicitly imagined as one accommodating a mixed-language identity.

The article first provides a brief overview of the literature on conflict that informs the main hypothesis on the polarization of identities. It then briefly summarizes the literature on the complex cleavage structures in Ukraine that map the backdrop against which the analysis unfolds. It then discusses the data and methodology before presenting both the overarching descriptive trends and the detailed empirical findings from the four interconnected data-sets, starting with the more generic identity category capturing a potential identity shift (“more Ukrainian,” “more Russian,” “more both,” “no change”) and moving on to the factors underpinning the identity category “Ukrainian citizen.”

Identities in conflict settings and in Ukraine

Identities are, at least to a significant extent, socially constructed. This includes ethnic identities (e.g. Brubaker Citation1996, 2002, 2009; Fearon and Laitin Citation2000; Hale Citation2004). The component parts of identities and the process by which they are re-assembled in particular situational and relational fields is, however, difficult to unpack empirically. Identity shifts are particularly hard to capture empirically. Political and economic crises and wars are settings that disrupt the equilibria underpinning seemingly stable identities. The disruption of everyday life, structures, networks, and loyalties can facilitate identity shifts. Only longitudinal studies could, of course, capture whether the shifts are temporary or more permanent phenomena. Theory also suggests that political identities evolve in a two-way process, with the political context shaping identities and vice versa (Wimmer Citation2016). In this article, the emphasis is on the former.

Comparative research on conflict has focused on the causes – among them divisive identities – rather than the effects of war on identities or the multidirectional identity transformations during and after war (Sambanis Citation2002; Esteban and Schneider Citation2008; Kalyvas Citation2008; Wood Citation2015). Those who have tackled the effects of war have primarily traced and highlighted the polarization of social and ethnic identities (Fearon and Laitin Citation2000; Gurr Citation2000; Esteban and Schneider Citation2008). By now, there is a large literature on radicalization, in particular Islamic radicalization, although few scholars have tried to systematically unpack the process and causal effects behind these developments (see, for example, Hughes (Citation2007) and Wilhelmsen (Citation2016) on the case of Chechnya). Former Yugoslavia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in particular have been prominent cases presented in terms of a fairly linear development from a more civic identity to polarized ethnopolitical identities. However, the visible fault lines during war cannot necessarily be equated with individual-level identities.

In fact, empirical research on the Balkan wars has called two hypotheses into question, namely the increase in ethnonationalism during or as a result of war, and the proposition that those directly involved in or affected by war become more ethnonationalist (see Dyrstad (Citation2012) on Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia and Massey, Hodson, and Sekulic (Citation2003) on Croatia). Similarly, Sekulic (Citation2004) found a stronger identification with Croatian citizenship rather than self-identification in ethnic terms. And Strabac and Ringdal (Citation2008) have demonstrated that the individual experience is less important than the local intensity of fighting for the increase in ethnic prejudice in Croatia.

Ukrainian state – and nation-building have been shaped critically by the country’s internal diversity (Szporluk Citation1997; Zimmerman Citation1998; Sasse Citation2001; Shevel Citation2002, 2009). The complex cleavage and identity structures in Ukraine have occupied area experts for a long time (e.g. Arel Citation1995, Citation2014; Holdar Citation1995; Pirie Citation1996; Birch Citation2000; Kubicek Citation2000; O’Loughlin Citation2001; Barrington Citation2002; Hale Citation2004, 2010; Shulman Citation2004; D'anieri Citation2007; Lushnycky and Riabchuk Citation2009; Sasse Citation2010; Kulyk Citation2011; Osipian and Osipian Citation2012; Frye Citation2015). There is widespread agreement on the political salience of regions in Ukrainian politics, from voting to foreign policy preferences, but the extent to which region equates with ethnicity and/or language and what exactly region captures beyond the two variables – socioeconomic differences, and variation in historical legacies and/or diffusion and linkage effects – remains disputed. Moreover, the conditions under which certain cleavages and identities become salient or change remain underexplored. For example, region of residence, language, and ethnicity have been highlighted as key factors individually or jointly explaining different political orientations (Smith and Wilson Citation1997; Ryabchouk Citation1999; Barrington and Faranda Citation2009; Arel Citation2014). Kulyk (Citation2011) has shown that native language can be a powerful predictor of people’s attitudes and institutional preferences, e.g. on language use but also on other socially divisive issues, such as foreign policy orientation or historical memory. However, he has also emphasized the discrepancy between language practice and language identity, distinguishing between the language that is routinely used and the language that is perceived to be the “native” language (Kulyk Citation2011, 628) and, more generally, the pitfalls of interpreting Ukrainian politics through a prism of ethnicity and language alone (Kulyk Citation2014; see also Sasse Citation2007, 2010).

More recently, Ivanov (Citation2015) found that the “language environment” within a region is more significant than ethnicity in explaining geopolitical orientations in Ukraine. However, at the height of the Euromaidan political crisis language or ethnicity was not a significant determinant of political attitudes and action (Onuch and Sasse Citation2016). Research on vote choice in Ukraine has found recently that it is related more to the candidates’ economic policy orientation toward the West rather than a candidate’s ethnic or language characteristics (Frye Citation2015). Thus, the actual significance of language and ethnicity in Ukrainian politics remains unclear. They may well vary in their importance depending on the political context at any given moment in time.

It has also been argued recently that the political crisis in Ukraine – from the Euromaidan to the experience of war – has strengthened the sense of political unity and state identity in Ukraine, including higher regard for the Ukrainian language as the symbolic marker of this state identity (Alexseev Citation2015; Kulyk Citation2016, 2018). Research on the war in Ukraine has also hypothesized or sought to validate the growing polarization of identities in the war zone, focusing on the “radicalization of Russians in Ukraine” as a result of political opportunities (Lozhkariov and Suzhentsov Citation2016), describing a new identity formed in light of history and politics in a “leaderless rebellion” in the non-government-controlled areas (Matveeva Citation2016), or tracing the historical precursors of an ideological patchwork described as a “resistance identity” (de Cordier Citation2017).

On the basis of recent survey data this article probes further how significant civic versus particularistic or polarized identities are among those most directly affected by the war in Ukraine – the local population and the displaced – and what factors underpin these identities. Two central questions emerge from the comparative literature on war and the determinants of Ukrainian politics: first, how polarized are the identities among those most affected by the war as the events are unfolding, and second, what factors underpin the prevalent polarized or civic identities?

Data and methodology

Opinion polls in Ukraine are currently not “nationally representative” in a strict sense, as they exclude the occupied territories. The four-part ZOiS suvey, implemented by R-Research from 1 to 15 December 2016, on which this article is based, aims to rectify this gap as credibly as is possible in a situation of war. In Kyiv-controlled Donbas, face-to-face interviews were conducted based on a multi-stage quota sample (n = 1200 split evently between Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts). The sample was aligned with the age and gender quotas of the urban and rural populations as recorded in official state statistics of 2016 and educational attainment by oblast as recorded by the 2001 census. In the absence of trustworthy official data on the occupied territories, the same quotas were applied to the DNR/LNR. There is no apparent a priori reason why the baseline criteria should be different in these two parts of the Donbas region.Footnote 1 Due to the difficulties of access and ethical considerations, a telephone survey rather than face-to-face interviews was implemented in the DNR/LNR (n = 1200). The questionnaire therefore had to be shortened and simplified (e.g. the detailed identity question does not exist in the DNR/LNR survey).Footnote 2

Additionally, internally displaced people (IDPs) in Ukraine (n = 999) and those who fled to Russia (n = 1007) were polled between 1 and 18 December 2016 among both registered displaced persons and persons who provide for themselves and their families independently without registering their status.Footnote 3 The survey of IDPs covered six oblasts in Ukraine (among them those with the highest concentration of registered IDPs, namely Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kharkiv oblasts – accounting for 60% of the sample; Dnipro Oblast as a further region bordering the conflict; Kyiv City and Kyiv Oblast; and a Western Oblast known to have attracted a significant number of refugees (Lviv Oblast). The quota sampling was based on official data on the profile of the IDPs (the majority is middle-aged, two-thirds are women).Footnote 4 The survey among the displaced in Russia covered Moscow City and 11 Western and central oblasts with known concentrations of the displaced.Footnote 5 In the absence of information on the displaced in Russia, the quotas were aligned with the IDP sample. A priori there is no reason to believe that the profile of the internally and externally displaced should vary significantly.Footnote 6

The four surveys sought to explore self-reported identities during war. As such, they present self-identification at a particular moment in time. The period during which the survey data were collected (the first half of December 2016) was not characterized by a major escalation in the fighting overall, but locally the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission reported ceasefire violations on both sides, casualties, and injured civilians. A high-level meeting in the Normandy format in October 2016 had restated the general commitment to Minsk and conflict-resolution without, however, achieving any breakthrough on the sticking points, in particular the implementation sequence of the security and political dimensions of the Minsk agreement.

The only way in which a cross-sectional survey can speak cautiously to the question of personal identity change is to tap into self-reported changes. Due to the personal nature of identities, this is a meaningful extension that maps individual perceptions of continuity and change. These perceptions matter, but it is worth emphasizing that one does not measure something exact and easily verifiable. Biases resulting from the current political setting or the interview situation can affect the respondents’ answers. However, this dilemma is not unique as it can characterize even well-resourced research carried out in stable democracies.

Dependent variables

Our research operationalizes self-reported identity in two steps. Identity change was operationalized using a categorical variable derived from the following question about self-reported identity change: “As a result of the events 2013–16, do you feel…” – with the possible answer categories: “More (like a) Ukrainian than before”;Footnote 7 “More (like a) Russian than before”; “I feel more strongly than before that I am both”; and “There has been no change.”Footnote 8 All categories were recoded as dummy variables. For example, for the dummy variable More_Ukrainian, the first answer category of the original variable (“more Ukrainian than before”) was coded as 1, and all other categories were coded as 0. The same procedure was applied to the other identity categories as dependent variables, including No change.

While the first more general question avoided an early narrowing of the question to explicitly defined ethnic or civic identity categories, a further question asked for the most important self-identification based on a long list of options (“What identity is most important to you personally today – first choice?”Footnote 9 ). The response categories included 15 options such as “Ukrainian citizen,” “ethnic Ukrainian,”Footnote 10 “ethnic Russian,” “mixed-ethnic Ukrainian and Russian,” as well as language (e.g. Russian speaker, Ukrainian speaker, Russian and Ukrainian speaker) and regional categories (“person from Donbas,” further broken down into “person from Donetsk Oblast,” and “person from Luhansk Oblast”). For our analysis, the dependent variable Ukrainian_citizen was derived from this original variable, coding the answer category “Ukrainian citizen” as 1, and all other answer categories as 0.

Independent variables

Language was operationalized using two different measures: (1) self-identified native language; and (2) athome_language. For the two surveys focusing on the displaced, the latter was again split into former language use at home (Donbas), and current language use at home (new place of residence). The question about native language was: “What language do you consider to be your native language?,” with the answer categories “Russian,” “Ukrainian,” “Both Russian and Ukrainian,” and “Other.” This variable was recoded with the reference category being native language_ russian, thereby allowing us to interpret the regression results in relation to the reference category.

Language use was operationalized on the basis of the question “Which language do you typically speak at home?,” with the answer categories 1 = “Only Ukrainian,” 2 = “Mostly Ukrainian, Occasionally Russian,” 3 = “Equally, Ukrainian and Russian,” 4 = “Mainly Russian, Occasionally Ukrainian,” and 5 = “Only Russian.” Answers 2, 3, and 4 were collapsed into “both.” In the next step we recoded with the reference category being athome_Russian. For the displaced two separate dummy variables were generated: donbas_ukrainian and donbas_both (indicating language use at home in Donbas with the reference category being donbas_russian) as well as newplace_ukrainian and newplace_both, indicating language use in the new place of residence with the reference category being newplace_Russian.

Religion was operationalized recoding the most dominant categories from a 10-level categorical variable into dummies. Those categories are, for respondents in the Kyiv-controlled Donbas as well as for the displaced: “Orthodox – Kiev patriarchate,” “Orthodox - Moscow patriarchate,” “Orthodox – Ukrainian Autocephalous,” and “Atheist/no religion.” For respondents from DNR/LNR, the category “Christian” was much more dominant than “Ukrainian Autocephalous,” and was therefore replaced. For example, the dummy variable orthodox_kiev codes all respondents whose religion is “Orthodox – Kiev patriarchate,” as 1, and all other respondents as 0. In all regression models, standard demographic and socioeconomic control variables were included (gender, age, income, employment status, urban/rural, education).Footnote 11

For the displaced, the following variables were added in the regression models: from_donetsk_oblast, oblast_interview, and family_here. The variable from_donetsk_oblast indicates whether a respondent came from Donetsk Oblast (=1) or from Luhansk Oblast (=0), or from somewhere else (=0). The variable oblast_interview was included as a factor variable in the analysis and indicates the oblast where the respondent was interviewed. Base categories are Donetsk Oblast (for the displaced in Ukraine) and Moscow City (for the displaced in Russia). Finally, the variable family_here indicates whether the respondent had family at the place where he/she arrived (yes = 1, no = 0). For the respondents in the Donbas and in the DNR/LNR data-set, the dummy variable Donetsk oblast was included to indicate the location of the interview (1 = Donetsk Oblast, 0 = Luhansk Oblast).

Analysis

The analysis presented in this article proceeds in three steps: First, this article presents the descriptive insights of the four-part survey – both with regard to the question combining a more general wording of the identity categories and a self-reported change compared to the pre-war period and with regard to the self-reported changes in the identification as a “Ukrainian citizen.” Second, we unpack the factors associated with both types of identity categories “more Ukrainian,” “more mixed” etc. and “Ukrainian citizen,” respectively. Among the independent variables are native language and language use, religion, region of residence, and region of origin/destination in the case of the displaced, and a battery of socioeconomic control variables.

As all dependent variables are dummy-coded, logistic regression models were applied. Independent variables were introduced step by step in three models to investigate possible overlaying effects. Independent variables that were perfect predictors in some models were excluded from the regression analysis. Regression results are reported as odds ratios. The tables included here report the respective third models only, dropping variables that are not significant (the full models are included in the Electronic Appendices 1–7).

Self-reported identity change

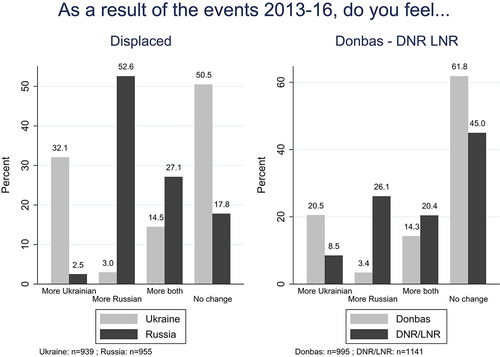

As for the first more general question about a change in personal identity as a result of the events of 2013–2016, a quarter of the respondents in the occupied territories said that they felt “more Russian” now – and a fifth of the respondents in the Kyiv-controlled Donbas reported that they felt “more Ukrainian” now (Figure ). Interestingly, however, 14 and 20% in the Kyiv-controlled and occupied Donbas, respectively, said that they felt more strongly now that they are “both Ukrainian and Russian.” The majority in both parts of the Donbas reported no change in identity: 62% in the government-controlled Donbas and 45% in the self-declared republics. Thus, while there has been a greater shift in identities in the occupied territories, a significant number of respondents reported not only a stable identity, but also an increase in a mixed identification.

Figure 1. Reported change in personal identity as a result of the events of 2013–2016. Source: ZOiS survey 2016.

Bigger identity changes were recorded among those displaced to Russia (only about 18% of respondents reported “no change”). Asked generally, whether their identity has changed as a result of the events 2013–2016, just over 50% said they felt “more Russian” now but interestingly, close to 30% said they felt more strongly than before that they were “both Russian and Ukrainian.” Among the internally displaced, half the respondents reported an identity shift – and the other half did not. Just over 30% of the IDPs stated that they now felt “more Ukrainian,” and 15% felt more strongly that they were “both Ukrainian and Russian.” Thus, mixed identities remain – or have become even more – important among those who are most directly affected by the war. This salience of mixed identities stands in contrast to the polarization characterizing much of the analysis of Ukraine in peaceful times. If mixed identities are apparent during a war, they are even more likely to be present under normal conditions as well.

Regression analysis

Donbas

The likelihood of self-identifying as “more Ukrainian” increases across the three models when a respondent reports Ukrainian or both Ukrainian and Russian as his or her native language(s). A respondent who reports that Ukrainian is his or her native language is 4.5 times more likely (compared to all other respondents) to feel “more Ukrainian” than before (controlling for all other variables; see Table ). Similarly, Ukrainian as the language spoken at home increases the odds of feeling “more Ukrainian.” Respondents in Luhansk Oblast are twice as likely to feel “more mixed” (i.e. Ukrainian and Russian), with this sub-national distinction being the only statistically significant factor. None of the demographic and socioeconomic controls have a significant effect.Footnote 12

Table 1. Donbas: self-reported identity change.

DNR/LNR

The main trends indicated above are replicated in the case of the self-declared DNR/LNR (Table ). Being a native Ukrainian speaker and being a native speaker of both Ukrainian and Russian, compared to being a Russian native speaker, increases the odds of describing oneself as “more Ukrainian” as a result of the events since 2013. A person who thinks of Ukrainian as his or her native language is 14 times more likely, and a person who speaks both is still four times more likely to feel “more Ukrainian,” compared to all other respondents. Being a follower of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate reduces the likelihood of self-identifying as “more Ukrainian” today, or put differently, all other respondents are 2.5 times more likely to choose the identity category “more Ukrainian.”

Table 2. DNR/LNR: self-reported identity change.

Conversely, “more Russian” is the category that is over three times as likely to be chosen by those who self-report Russian as their native language (compared to Ukrainian or both Ukrainian and Russian) and describe themselves as followers of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. Individuals who are followers of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate are more than twice as likely, compared to all other religions, to feel “more Russian” than before.

Those identifying with the option “more mixed” are almost twice as likely to be native speakers of both Ukrainian and Russian, compared to Russian native speakers. Following the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate increases the likelihood of self-identifying as “more mixed,” but only before the socio-demographic variables are controlled for. Thus, the same religious affiliation is associated with “more Russian” and “more both” and thereby does not represent a clear-cut explanatory factor.

“No change” in self-identification is about half as likely among followers of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate than for individuals of all other denominations. Furthermore, people with higher education have about a 40% higher chance of feeling “no change” in their identity compared to 2013.Footnote 13

Displaced Ukraine

Being a native Russian language speaker significantly decreases the odds of reporting a shift toward feeling “more Ukrainian” as the result of the events over the last few years. Being a native Ukrainian speaker offers a strong statistically significant positive association across the three models, as does having two native languages (Ukrainian and Russian). Someone who considers Ukrainian to be his or her native language is more than four times as likely to feel “more Ukrainian” compared to all other groups (Table ). Similarly, those for whom both Ukrainian and Russian are their native languages – they are more than twice as likely to feel “more Ukrainian.” Following the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church raises the odds of feeling “more Ukrainian” by 6.6, and being an atheist raises the chances by 2.7. Furthermore, living in an urban environment significantly decreases the odds of self-identifying as “more Ukrainian.”Footnote 14

Table 3. Displaced in Ukraine: self-reported identity change.

The reverse logic also holds: having chosen Ukrainian or both Ukrainian and Russian as one’s native languages decreases the odds of feeling “more mixed.” Still, speaking both languages in the new places of residence increases the chances of feeling “more mixed” by around 2.4. Again, being a follower of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate means that the person is three times more likely to report a stronger mixed identity.

Those who report being followers of the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate are less likely than all other religious groups to report “no change” when asked about their identity since 2013. People living in an urban environment are 3.6 times more likely than people in rural areas to report “no change.” Moreover, residing in Lviv Oblast and Luhansk Oblast increases the odds of indicating no identity change significantly. Being displaced within one’s former region may disrupt a displaced person’s mental parameters less – finding the same with regard to displacement to a western region suggests a choice of destination to suit one’s identity.

Displaced Russia

Those who spoke Ukrainian in their previous Donbas location are significantly more likely to report an identity shift toward feeling “more Ukrainian” than those who spoke Russian or both languages in the Donbas (Table ). Furthermore, speaking both languages in their new environment in Russia increases the odds of feeling “more Ukrainian.” This suggests that for the former Donbas residents now living in Russia, the Ukrainian language, even if spoken in parallel to Russian, is a key identity marker.

Table 4. Displaced in Russia: self-reported identity change.

Table 5. Dependent variable: Ukrainian citizenship as primary identity.

Russian native speakers among the displaced in Russia are three times more likely to report an identity shift toward feeling “more Russian.” Speaking both languages in the new places of settlement significantly decreases the chances of feeling “more Russian” – again a sign that the Ukrainian language, even if spoken alongside Russian, is a key signifier. Followers of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate are three times more likely, compared to all others, to report feeling “more Russian.” Being a man increases the chances of feeling more Russian by 45%. The odds of reporting an identity shift toward “more Russian” are positively and significantly linked to being based in Krasnodarskii Krai and Ul’yanovskaya Oblast. Residing in Ul’yanovskaya Oblast is also a significant factor behind indicating “no change” in one’s identity.

The odds of feeling “more mixed” (Ukrainian and Russian) compared to before 2013 are significantly higher for those who consider both Ukrainian and Russian their native languages. Furthermore, being an atheist reduces the chances of feeling more strongly that one has a mixed identity.Footnote 15

In sum, in the Donbas and in the DNR/LNR native language emerges as the key variable associated with self-reported identity change. In the Donbas and in the DNR/LNR, considering Ukrainian or both Ukrainian and Russian one’s native language significantly increases the likelihood of a self-reported identity change toward feeling “more Ukrainian” or “more mixed.” Similarly, the language spoken at home matters: speaking Ukrainian (in the case of the Donbas population) or both Ukrainian and Russian (in the case of the DNR/LNR population) at home is linked to feeling “more Ukrainian.” Conversely, reporting a change toward feeling “more Russian” as a result of the events since 2013 is associated with Russian native language. Religious affiliation and, in particular, being a follower of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate increases the odds of describing oneself as “more Russian” or indicating “no change” in one’s identity.

Among the displaced, language is also a strong predictor of identity change, though there are some differences between the displaced in Ukraine and the displaced in Russia. Native Ukrainian language and dual Ukrainian–Russian native language is closely linked to feeling “more Ukrainian” across both populations. In the case of the displaced in Ukraine, both Ukrainian native language and the dual native language variable decrease the odds of feeling “more mixed.” The language spoken before and after displacement matters for the displaced in Russia: having spoken Ukrainian before displacement is associated with feeling “more Ukrainian” now, as is speaking both Ukrainian and Russian at the new place of residence. Russian native language increases the odds of self-reporting a change toward feeling “more Russian.”

Ukrainian citizenship as primary identity

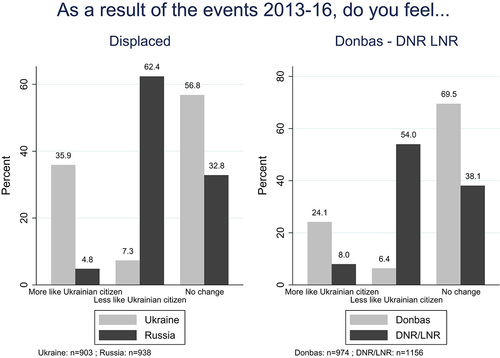

When asked whether their sense of being a Ukrainian citizen has been strengthened or weakened by the events in 2013–2016, 24.1% of the respondents in the Kyiv-controlled Donbas see their identification as Ukrainian citizens strengthened, with 6.4% describing it as having weakened and 69.5% as unchanged (see Figure ). Of the latter, 55.7% report Ukrainian citizen as their main identity now and 53.1% five years ago (see Figures 1 and 2 in the online appendix). The recorded patterns in the DNR/LNR diverge from those in the rest of the Donbas and mirror those of the displaced in Russia: only 8% of the respondents in the DNR/LNR feel more like Ukrainian citizens now, compared to 54% feeling less like Ukrainian citizens and 38% recording no change (see Figure ).Footnote 16

Figure 2. Reported change in the sense of being a Ukrainian citizen as a result of the events in 2013–2016. Source: ZOiS survey 2016.

There has been a clear increase in the importance of the notion of Ukrainian citizenship among the displaced in Ukraine: 35.9% say that they now feel more like Ukrainian citizens, compared to 7.3% reporting they now feel less like Ukrainian citizens. Approximately 56.8% say there has been no change to their identification as Ukrainian citizen. A closer look at the identity profile of these respondents (n = 500) shows that 54.4% listed Ukrainian citizenship as their most important identity today and 56.6% as their most important identity five years ago. This underlines the importance of Ukrainian citizenship as a category both in 2016 and five years earlier. Among the displaced in Russia, the trend is reversed: only 4.8% now feel more like Ukrainian citizens, while 62.4% feel less like Ukrainian citizens. Of the 32.8% of displaced in Russia who indicate that there has not been a change in their position on Ukrainian citizenship (n = 272), 10.7% chose Ukrainian citizenship as their main identity in 2016, down from 23.7% five years earlier (see Figures 3 and 4 in the online appendix).

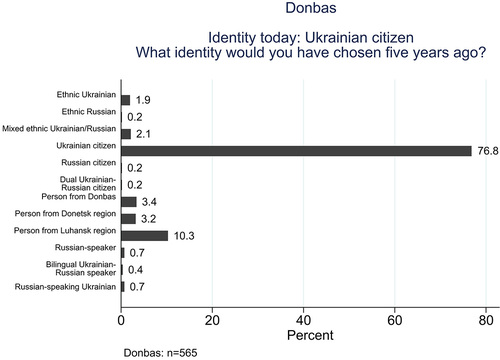

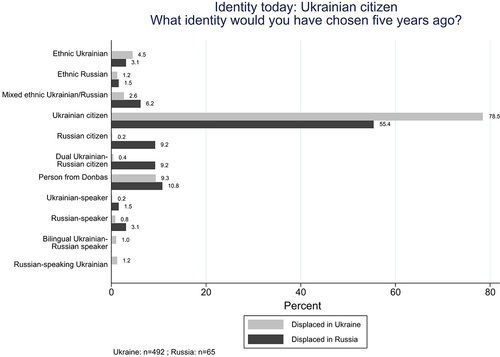

Among the respondents from the Kyiv-controlled Donbas whose primary identity in 2016 is “Ukrainian citizen,” 76.8% say they would have said the same five years earlier, while 16.9% would have chosen a regional identity (made up here of Donbas, Donetsk Oblast, and Luhansk Oblast) (see Figure ). Among the displaced in Ukraine identifying as Ukrainian citizens as their main identity today, 78.5% said they already did so five years ago, with the rest indicating primarily a shift from the regional identification as “a person from the Donbas” (9.3% five years ago) or “ethnic Ukrainian” (4.5% five years ago) to “Ukrainian citizen” today. The number of the displaced in Russia identifying as “Ukrainian citizens” today is low (n = 56) and therefore less robust, but the change has occurred from a range of different identity categories, with the regional one also marking the biggest shift (see Figure ).

Figure 3. Identity flows as percentage share of those in Ukrainian-held Donbas choosing “Ukrainian citizen” as their primary identity in 2016 and reporting the identity they would have chosen five years ago (2011). Source: ZOiS survey 2016.

Figure 4. Identity flows as percentage share of those displaced in Ukraine and in Russia choosing “Ukrainian citizen” as their primary identity in 2016 and reporting the identity they would have chosen five years ago (2011). Source: ZOiS survey 2016.

The statistical analysis helps us to identify some of the factors behind the self-identification as a Ukrainian citizen among current and former residents of the Donbas as a whole.

Regression analysis

Donbas

Across the three models, the respondents from the Kyiv-controlled Donbas are significantly more likely to self-identify as Ukrainian citizens today if Ukrainian is their native language or they speak both languages at home. Being a follower of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate or an atheist both somewhat decreases the odds of describing oneself as a Ukrainian citizen.Footnote 17

Displaced in Ukraine

The identity category “Ukrainian citizen” is not significantly shaped by language factors throughout the three models. Only in the first model based on a range of language criteria do native Russian language speakers and those for whom both Russian and Ukrainian are native languages come out as being significantly less likely to self-identify as Ukrainian citizens. This effect disappears when further variables related to regional destination and religious affiliation are added: residence in the Lviv region, for example, is strongly associated with self-identification as a Ukrainian citizen (while residence in Kyiv and Kyiv Oblast are negatively correlated, a finding the interpretation of which would require more detailed information about the actual experiences of the respondents), and there is a weak religious effect: followers of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church are almost 13 times more likely than all others to identify as Ukrainian citizens. These effects hold up when demographic and socioeconomic controls are added, none of which are significant by themselves.

Displaced in Russia

Among the displaced in Russia the factor increasing the odds of self-identifying as a Ukrainian citizen is being a native Ukrainian speaker. By comparison, having had family at the new place of settlement, being a follower of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, and being male reduces the odds somewhat.

Overall, the role of native language and language use is less clear than in the case of the self-reported identity change discussed above. Among the Donbas population, Ukrainian native language and dual language use at home are the most important factors associated with Ukrainian citizenship as the respondents’ primary identity category. Similarly, among the displaced in Russia considering Ukrainian one’s native language increases the odds of choosing Ukrainian citizenship as one’s main identity. In the case of the displaced in Ukraine, however, language is not a consistently significant factor – here the region of residence seems to play a bigger role. Being a follower of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate reduces the likelihood in the case of the Donbas population and the displaced in Russia, while following the Autocephalous Church increases the odds of identifying as a Ukrainian citizen in the case of the displaced in Ukraine.

Conclusion

The data from the four interrelated surveys suggest that there has not been a clear-cut effect of war on the identities of the current and former Donbas population. While there is evidence of a degree of polarization and ethnification, this is only one part of a more complex pattern. Mixed or civic identities have also been maintained across all four groups and, in some cases, strengthened. It is particularly striking that Ukrainian citizenship is (and was) by far the most prevalent self-reported identity in the Kyiv-controlled Donbas and among the IDPs. An already strong identity has been reinforced, in particular, by a self-reported shift from regional identities centered on the Donbas or, more specifically, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

Among the displaced in Russia, Ukrainian citizenship represented a more significant identity category before the crisis (for about a third of the respondents in this category it was the most important identity) than one might have expected in light of previous scholarship that has highlighted conflictual ethnic, linguistic, or regional identity categories in Ukraine. Among those displaced to Russia and the residents of the DNR/LNR, however, Ukrainian citizenship as an identity has been significantly weakened by the war. Among the displaced, the “bigger” move – displacement from the Donbas to Russia – is linked to a greater self-reported identity shift.

For identity change as expressed by the broad categories “more Ukrainian,” “more Russian,” and “more both,” native language (and to some extent language practice) matters. Interestingly, both mono- and bilingual notions of native language are significantly associated with self-identifying as “more Ukrainian.” A similar trend holds for the choice of “Ukrainian citizen” as the primary identity in the Kyiv-controlled Donbas (the survey in the DNR/LNR could not ask this detailed question) and among the displaced in Russia (for the latter only Ukrainian native language is significant). When probing the factors underpinning “Ukrainian citizenship,” demographic and socioeconomic factors are by and large irrelevant.

Religious affiliation is a further variable of significance: followers of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate are less likely to report feeling “more Ukrainian” and more likely to feel “more mixed” or “more Russian.” The association in the case of “Ukrainian citizenship” as the main identity is less clear, though belonging to the Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) mostly reduces the odds of choosing Ukrainian citizenship as one’s main identity.

Our analysis also suggests that the particular regional or local environments of the displaced in their new destinations can have an effect on their identities.Footnote 18 It calls for further qualitative work in the different locations of the displaced in order to better understand the link between a displaced person’s environment and his/her political identity. In some cases, a particular local or regional environment appears to foster polarization, in others it does not. Distance from the war zone may in fact be associated with more clear-cut or polarized identities, but our data do not allow for a detailed exploration of this hypothesis.

Overall, language (mainly native language, occasionally language use at home) carries weight in explaining the likelihood of mixed or civic Ukrainian identities during war and displacement. Our survey does not allow for a systematic comparison with the situation before the war. Interestingly, it is not only one native language – Ukrainian – that emerges as the key factor; a self-reported dual native language (Ukrainian and Russian) has a similar effect, in particular on the self-reported identity shifts toward feeling “more Ukrainian” and “more mixed.” It is possible that current and former residents of the Donbas generally feel more comfortable identifying with Ukrainian as a native language (or part of a dual identification with Ukrainian and Russian) now than compared to before the war. There may be additional factors beyond our list of variables explaining both native Ukrainian or Ukrainian–Russian language identification and a feeling of being a Ukrainian citizen. But our data establish that feeling “more Ukrainian” across all four populations and Ukrainian citizenship in the case of the current Donbas population can explicitly and simultaneously accommodate mono- and bilingual language identities. It therefore cautions against the polarization hypothesis emanating from the literature on conflict and supports recent research on the growing sense of political unity inside Ukraine.

Electronic_Appendix.zip

Download Zip (194.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the reviews and comments received on earlier versions of this paper, including those provided by the participants of the Workshop “After the Revolution: Reform and Identity in Ukraine,” Princeton University, 3 May 2017; the Roundtable “Identity in Times of Crisis and Conflict in Ukraine” at the ASN Convention, New York, 4 May 2017; and the Workshop “Ukraine: Identities in Flux” at ZOiS, Berlin, 22 September 2017.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The survey on which this paper is based was funded by the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS).

Supplemental data

The supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2018.1452209

Notes

1. Similarly, research on conflict has neglected the dynamics of conflict-prevention, including the effect of overlapping and civic identities (see, for example, Sasse (Citation2007) on Crimea in the 1990s).

2. The overall response rate in the Kyiv-controlled Donbas was 41% (36% in Donetsk Oblast and 46% in Luhansk Oblast). The discrepancy between the two oblasts is due to a significantly higher number of eligible households that could not be reached after three callbacks rather than the number of refusals to participate, which was equal across both oblasts. The response rate in the DNR was 17%, in the LNR 20%. The inability to establish contact was by far the most important reason for these rates (83% of eligible households in the DNR and 86% of eligible households in the LNR proved impossible to contact after three callbacks), with refusals of eligible households to take part accounting for only 10% of the contacts achieved in the DNR and 7% in the LNR.

3. The ratio of these two groups in the sample was the following: 90% of registered IDPs and 10% of non-registered IDPs. The survey was conducted in the following locations: organized IDP accommodation (halls of residence, camps, hostels, modular dwellings, etc.); settings where IDPs concentrate (e.g. NGOs, official agencies, banks); private homes of non-registered IDPs. All non-registered individuals were contacted using the referral method, with a registered IDP usually serving as the first contact person.

4. According to official published data 62% of the IDPs are women and 38% men. In terms of the age groups, the breakdown for the whole of Ukraine is reported as follows: 15–24 years of age: 7.8%; 25–29: 14.3%; 30–34: 18.8%; 35–44: 29.9%; 45–54: 23%; 55+: 6.2% (http://www.dcz.gov.ua/statdatacatalog/document?id=351058; http://voxukraine.org/2016/06/30/velyke-pereselennya-skilky-naspravdi-v-ukraini-vpo-ua/). The actual distribution by region is not known; therefore, the ZOiS survey applied the quota to the overall sample.

5. Moscow City, Belgorodskaya Oblast, Vladimirskaya Oblast, Voronezhskaya Oblast, Kaluzhskaya Oblast, Krasnodarskii Krai, Nizhegorodskaya Oblast, Orlovskaya Oblast, Rostovskaya Oblast, Samarskaya Oblast, Tul’skaya Oblast, Ul’yanovskaya Oblast. The ratio between registered and unregistered refugees in the Russia sample is 56%:44%, reflecting the rate of camp closures and the more difficult access to the displaced in organized accommodation.

6. The widening of the regional catchment area and the necessary re-allocation of interviews across regions in response to access difficulties have resulted in a slight oversampling of the younger cohort of the displaced in Russia compared to the quotas based on Ukrainian IDP data.

7. In the Ukrainian and Russian languages, the generic use and interpretation of the adverb “Russian” or “Ukrainian” does not function as well as in English. Trying to avoid stretching the language use beyond the categories actually used in public discourse, the categories Russkii and Ukrainets chosen for the Ukrainian and Russian language versions of the questionnaire, between which the respondents could choose, avoid a clear-cut ethnic or citizenship connotation.

8. Each question allowed for the answers “Don’t know” (DK) and “No answer” (NA). These were collapsed into one variable: Don’t know–No answer (DK-NA).

9. This variable was not available in the DNR/LNR data-set.

10. The use of the term “ethnic” (etnichnyi/etnicheskii in Ukrainian/Russian) in the ZOiS survey is a deliberate choice that aims to avoid confusion with citizenship identities. The Soviet-era category natsional’nist’/natsional’nost’ approximated our understanding of ethnicity and is still widely used. Its translation into English is problematic, however, as “nationality” refers to citizenship. Moreover, while Ukrainian- or Russian-speaking respondents may still answer with the old ethnic distinctions in mind, interpretations of the survey results do not always uphold this distinction between ethnic and civic identities.

11. The variable income captures the respondents’ self-reported total net amount of money earned by all members of their household in the last month, including salaries, pensions, sales. The employment status was measured using a categorical variable with 11 categories, including full-time and part-time work, maternity leave, unpaid leave. The dummy variable employed was generated by coding all respondents who are either full-time or part-time employed as 1, and all others as 0. The dummy variable urban recoded three response categories as follows: “city/town” and “urban-type settlement” were recoded as 1, and “rural” as 0. Level of education was controlled for using a categorical variable ranging from 1 (primary education) to 9 (completed graduate degree). This variable was recoded as the dummy variable higher_education, with a value 1 for all respondents scoring a 6 or higher on the original variable and a 0 for all respondents with a value lower than 6.

12. The dependent variables “more Russian” and “no change” did not show significant results and are not reported here.

13. Considering both Ukrainian and Russian as one’s native languages, being a woman, and having an urban background increases the odds of having chosen the combined answer “Don’t Know–No Answer” (see Electronic Appendix 2).

14. The odds of describing oneself as “more Russian” are associated with having spoken Ukrainian at home in the Donbas before having been displaced, without there being an obvious explanation for this somewhat surprising result. Furthermore, having family in the new place of residence raises the chances of feeling “more Russian”.

15. See Electronic Appendix 4.

16. The telephone interviews in the DNR/LNR did not allow for the replication of the detailed question allowing for the comparison of those identifying as Ukrainian citizens as their primary identity now as compared to five years ago.

17. The equivalent question could not be replicated in the shorter format of the telephone interviews in the DNR/LNR.

18. This preliminary finding mirrors recent research on the significance of destination characteristics as determinants of migrant political behavior (e.g. Lafleur and Sánchez-Domínguez Citation2015; Ahmadov and Sasse Citation2016).

References

- Ahmadov, Anar K. , and Gwendolyn Sasse . 2016. “A Voice despite Exit: The Role of Assimilation, Emigrant Networks, and Destination in Emigrants’ Transnational Political Engagement.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (1): 78–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015600468.

- Alexseev, Mikhail . 2015. “War and Sociopolitical Identities in Ukraine.” Ponars Eurasia. Policy Memo 392. http://www.ponarseurasia.org/memo/war-and-sociopolitical-identities-ukraine

- Arel, Dominique . 1995. “Language Politics in Independent Ukraine: Towards One or Two State Languages?” Nationalities Papers 23 (3): 597–622. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00905999508408404.

- Arel, Dominique . 2002. “Interpreting ‘Nationality’ and ‘Language’ in the 2001 Ukrainian Census.” Post-Soviet Affairs 18 (3): 213–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.2747/1060-586X.18.3.213.

- Arel, Dominique . 2014. “Double-Talk: Why Ukrainians Fight over Language.” Foreign Affairs . Accessed March 18. http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/141042/dominique-arel/double-talk

- Barrington, Lowell W. 2002. “Examining Rival Theories of Demographic Influences on Political Support: The Power of Regional, Ethnic, and Linguistic Divisions in Ukraine.” European Journal of Political Research 41 (4): 455–491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00019.

- Barrington, Lowell , and Regina Feranda . 2009. “Re-Examining Region, Ethnicity, and Language in Ukraine.” Post-Soviet Affairs 25 (3): 232–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.2747/1060-586X.24.3.232

- Birch, Sarah . 2000. “Interpreting the Regional Effect in Ukrainian Politics.” Europe-Asia Studies 52 (6): 1017–1041. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130050143815.

- Bremmer, Ian . 1994. “The Politics of Ethnicity: Russians in the New Ukraine.” Europe-Asia Studies 46 (2): 261–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668139408412161.

- Brubaker, Rogers . 1996. Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511558764

- Brubaker, Rogers . 2002. “Ethnicity without Groups.” European Journal of Sociology 43 (2): 163–189. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975602001066.

- Brubaker, Rogers . 2009. “Ethnicity, Race, and Nationalism.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 21–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115916.

- de Cordier, Bruno . 2017. “Ukraine’s Vendée War? A Look at the ‘Resistance Identity’ of the Donbass Insurgency.” Russian Analytical Digest 198: 2–6. Accessed February 14. www.laender-analysen.de/russland/rad/pdf/Russian_Analytical_Digest_198.pdf

- D'anieri, Paul . 2007. “Ethnic Tensions and State Strategies: Understanding the Survival of the Ukrainian State.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 23 (1): 4–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523270701194896.

- Dyrstad, Karin . 2012. “After Ethnic Civil War: Ethno-Nationalism in the Western Balkans.” Journal of Peace Research 49 (6): 817–831. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343312439202.

- Esteban, Joan , and Gerald Schneider . 2008. “Polarization and Conflict: Theoretical and Empirical Issues.” Journal of Peace Research 45 (2): 131–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343307087168.

- Fearon, James D. , and David D. Laitin . 2000. “Violence and the Social Construction of Ethnic Identity.” International Organization 54 (4): 845–877. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/002081800551398.

- Frye, Timothy . 2015. “What Do Voters in Ukraine Want? A Survey Experiment on Candidate Ethnicity, Language, and Policy Orientation.” Problems of Post-Communism 62 (5): 247–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2015.1026200.

- Gurr, Ted . 2000. Peoples versus States. Minorities at Risk in the New Century . Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

- Hale, Henry E. 2004. “Explaining Ethnicity.” Comparative Political Studies 37 (4): 458–485. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414003262906.

- Hale, Henry E. 2010. “Ukraine: The Uses of Divided Power.” Journal of Democracy 21 (3): 84–98.https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.0.0174

- Holdar, Sven . 1995. “Torn between East and West: The Regional Factor in Ukrainian Politics.” Post-Soviet Geography 36 (2): 112–132.

- Hughes, James . 2007. Chechnya. From Nationalism to Jihad . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812202311

- Ivanov, Oleh . 2015. “Social Background of the Military Conflict in Ukraine: Regional Cleavages and Geopolitical Orientations.” Social, Health, and Communication Studies Journal 2 (1): 52–73.

- Kalyvas, Stathis N. 2008. “Ethnic Defection in Civil War.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (8): 1043–1068. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414008317949.

- Kubicek, Paul . 2000. “Regional Polarisation in Ukraine: Public Opinion, Voting, and Legislative Behaviour.” Europe-Asia Studies 52 (2): 273–294.https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130050006790

- Kulyk, Volodymyr . 2011. “Language Identity, Linguistic Diversity and Political Cleavages: Evidence from Ukraine.” Nations and Nationalism 17 (3): 627–648. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2011.00493.x.

- Kulyk, Volodymyr . 2014. “Soviet Nationalities Policies and the Discrepancy between Ethnocultural Identification and Language Practice in Ukraine.” In The Historical Legacies of Communism in Russia and Eastern Europe , edited by Mark R. Beissinger and Stephen Kotkin , 202–221. New York : Cambridge University Press.https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107286191

- Kulyk, Volodymyr . 2016. “National Identity in Ukraine: Impact of Euromaidan and the War.” Europe-Asia Studies 68 (4): 588–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2016.1174980.

- Kulyk, Volodymyr . 2018. “Identity in Transformation: Russian-Speakers in Post-Soviet Ukraine.” Europe-Asia Studies 70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2017.1379054.

- Lafleur, J.-M. , and M. Sánchez-Domínguez . 2015. “The Political Choices of Emigrants Voting in Home Country Elections: A Socio-Political Analysis of the Electoral Behaviour of Bolivian External Voters.” Migration Studies 3 (2): 155–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnu030.

- Lozhkariov, Ivan D. , and Andrey A. Suzhentsov . 2016. “Radicalization of Russians in Ukraine: From ‘Accidental’ Diaspora to Rebel Movement.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 16 (1): 71–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2016.1149349.

- Lushnycky, Andrej N. , and Mykola Riabchuk , eds. 2009. Ukraine on Its Meandering Path between West and East . Bern: Peter Lang.

- Massey, Garth , Randy Hodson , and Duško Sekulic . 2003. “Nationalism, Liberalism, and Liberal Nationalism in Post-War Croatia.” Nations and Nationalism 9 (1): 55–82.https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.2003.9.issue-1

- Matveeva, Anna . 2016. “No Moscow Stooges: Identity Polarization and Guerrilla Movements in Donbass.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 16 (1): 25–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2016.1148415.

- O’Loughlin, J. 2001. “The Regional Factor in Contemporary Ukrainian Politics: Scale, Place, Space, or Bogus Effect?” Post-Soviet Geography and Economics 42 (1): 1–33.

- Onuch, Olga , and Gwendolyn Sasse . 2016. “The Maidan in Movement: Diversity and the Cycles of Protest.” Europe-Asia-Studies 68 (3): 556–587. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2016.1159665.

- Osipian, Ararat L. , and Aleksandr L. Osipian . 2012. “Regional Diversity and Divided Memories in Ukraine: Contested Past as Electoral Resource, 2004–2010.” East European Politics & Societies 26 (3): 616–642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325412447642.

- Pirie, Paul S. 1996. “National Identity and Politics in Southern and Eastern Ukraine.” Europe-Asia Studies 48 (7): 1079–1104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668139608412401.

- Ryabchouk, Mykola . 1999. “A Future Ukraine: One Nation, Two Languages, Three Cultures?” Ukrainian Weekly 67 (23): 8–9.

- Sambanis, Nicholas . 2002. “A Review of Recent Advances and Future Directions in the Quantitative Literature on Civil War.” Defence and Peace Economics 13 (3): 215–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690210976.

- Sasse, Gwendolyn . 2001. “The ‘New’ Ukraine: A State of Regions.” Regional and Federal Studies 11 (3): 69–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/714004704.

- Sasse, Gwendolyn . 2007. The Crimea Question. Identity, Transition, and Conflict . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sasse, Gwendolyn . 2010. “Ukraine: The Role of Regionalism.” Journal of Democracy 21 (3): 99–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.0.0177.

- Sekulic, Duško . 2004. “Civic and Ethnic Identity: The Case of Croatia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (3): 455–483. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01491987042000189240.

- Shevel, Oxana . 2002. “Nationality in Ukraine: Some Rules of Engagement.” East European Politics and Societies 16 (2): 386–413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/088832540201600203.

- Shevel, Oxana . 2009. “The Politics of Citizenship Policy in New States.” Comparative Politics 41 (3): 273–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.5129/001041509X12911362972197.

- Shulman, Stephen . 2004. “The Contours of Civic and Ethnic National Identification in Ukraine.” Europe-Asia Studies 56 (1): 35–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966813032000161437.

- Smith, Graham , and Andrew Wilson . 1997. “Rethinking Russia's Post‐Soviet Diaspora: The Potential for Political Mobilisation in Eastern Ukraine and North‐East Estonia.” Europe-Asia Studies 49 (5): 845–864. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668139708412476.

- Strabac, Zan , and Kristen Ringdal . 2008. “Individual and Contextual Influences of War on Ethnic Prejudice in Croatia.” The Sociological Quarterly 49 (4): 769–796. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.00135.x.

- Szporluk, Roman . 1997. “Ukraine: From an Imperial Periphery to a Sovereign State.” Daedalus 126 (3): 85–119.

- Wilhelmsen, Julie . 2016. Russia’s Securitization of Chechnya: How War Became Acceptable . London: Routledge.

- Wimmer, Andreas . 2016. “Is Diversity Detrimental? Ethnic Fractionalization, Public Goods Provision, and the Historical Legacies of Stateness.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (11): 1407–1445. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015592645.

- Wood, Elizabeth Jean . 2015. “Social Mobilization and Violence in Civil War and Their Social Legacies.” In The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements , edited by Donatella della Porta and Mario Diani , 452–466. Oxford: Oxford University Press.https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199678402.001.0001

- Zimmerman, William . 1998. “Is Ukraine a Political Community?” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 31 (1): 43–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(97)00022-6.