Abstract

Governments and funding agencies increasingly expect researchers to demonstrate the impact of their work not only within the academy but also for a range of stakeholders beyond academia. Whilst arts researchers have tended to resist impact measurement, in this article, we will describe one form of demonstrating impact, namely through writing impact narratives in order to argue that such writing can be effective in promoting learning and reflection on the researcher’s work in the society. We provide collaborative autoethnographic narrative accounts of our experiences as arts education researchers, located in Australia and Finland, of developing research impact narratives and consider the ways in which the development of impact narratives can shape researcher identities, research processes and epistemic cultures of disciplines. We suggest that impact narratives are inevitably retrospective but may also be future-oriented in the ways in which they structure ongoing research processes and future projects and their activities providing a space for ‘narrative learning’ and professional transformation. We also suggest that arts educators experiment with and explore the potential for narrative impact statements to inform and engage society beyond academia with research findings and outcomes.

Introduction and policy focus

In an era of lost trust, assessment and performativity, governments and funding agencies in a range of nations expect that all researchers in all disciplines should demonstrate the impact of their work beyond the academic focus of the research (Esko & Miettinen, Citation2019; Hall et al., Citation2019; Hazelkorn, Citation2015; Reale et al., Citation2018). This movement commenced in the UK with the 2014 REF Impact Assessment exercise in higher education and aimed to “highlight(s) the relationship between science and society and its bearing on research conduct and evaluation” (Reale et al., Citation2018, p. 299). This development has been taken up in other jurisdictions and research agencies internationally as evidenced in Australia (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2015, Citation2017, Citation2018) and the European Commission (Citation2014). In order to track their performance and provide evidence of the benefits their work delivers, researchers increasingly use metrics such as google scholar citations and H-factors. University research funding systems, including recruitment and promotion processes increasingly require performance-based evidence which draws on publishers’ simple metrics. These metrics demonstrate impact and a research communities’ global reach through the system of ‘altmetrics’ that combines the number of actors who have mentioned the research with the media used to calculate an ‘attention’ score” (Thomas, Citation2018, p. 2). Moreover, at least in the UK, Australian and many European funding contexts the perceived merit of a research funding application is now linked to the capacity of the applicant to prescribe convincing pathways to research impacts. In the UK and Australian context the funders expect credible statements of how predicted impact will ensure economic and/or societal returns from their research. This requires “that academics demonstrate methodological competency in engaging with their research users, showing how research will be translated and appropriated in ways that most effectively service users’ needs” (Chubb & Watermeyer, Citation2017, p. 2362). Consequently, it is increasingly evident that all researchers must engage with the idea of impact and “learn new skills and behaviours and enter new networks” (Hall et al., Citation2019, p. 5). These new ways to measure and quantify research impact have created the hegemonic language of ‘impact’ (Katrakatzis et al., Citation2018, p. 451).

Whilst metrics and various indicators are useful in demonstrating how new knowledge is used by other scholars, there is a risk their pursuit may become an end in themselves (p. 451). It has also been argued that publicly funded research must now follow policies and articulate and generate an impact “which results in improved economic or social welfare if it is to be ‘worthwhile’” (Hall et al., Citation2019, p. 7). Some have considered the implications for scholarly moral conduct and unraveling of academic integrity to the extent of ‘corrosion of character’ in academic life when researchers are “selling their research ideas….[and]…the non-academic impact of these, to research funders” (Chubb & Watermeyer, Citation2017, p. 2360). The whole business of impact represents not only “the changing nature of competition but also the moral economy within higher education, where academics’ public citizenship is not an inherent, but rather an incentivized component of their professional lives” (p. 2362). These critical angles are worth considering, however, it also begs the question, if research is understood as communication that aims to achieve impact, albeit in various ways and time-frames, “why then is it that researchers often feel unprepared to pursue impact beyond the conventional reporting of their research findings?” (Katrakazis et al., Citation2018, p. 450).

Within the arts and arts education there has been a tendency to see the rise of impact indicators and measurements as a threat to autonomy, emphasizing quantity over quality, and failing to recognize the distinctive features of the arts. Resistance to the impact assessment agenda also references the neoliberal turn in higher education (Thomas, Citation2018) and a general fear of academic researchers becoming too embroiled in public relations strategies about their work at the expense of their independence and integrity (Chubb & Watermeyer, Citation2017). Katrakazis et al. (Citation2018) argue that “existing indicators primarily based on publication citations provide a rather incomplete picture of impact”, since for example, citation metrics may indicate awareness of new knowledge by other scholars but do not measure its uptake outside academic communities or indeed influence on practice” (p. 451).

It may be argued that the work of an arts’ researcher derives its motivation from the work of an artist, where the research intention is to interrogate questions of artistic innovation and quality rather than non-artistic questions, such as the impact of arts research on society. Belfiore (Citation2015) raises four (typical) objections to the impact agenda in arts and humanities research:

pragmatic: how to engineer and then measure convincingly the impact that is being claimed, promised or expected?

conceptual: what do we actually mean when we suggest that research might – or indeed even ought to – have an ‘impact’ beyond the academy?

political: who ought to have the right to decide what counts as desirable impact?

ethical: is the expectation of predictable impact, which is often meant to refer to impact on policy or the economy, a desirable or even legitimate expectation for academic research? Does this create tensions with the key academic principles of freedom and autonomy? (p. 99).

Katrakazis et al. (Citation2018) adds another dimension, namely that “researchers are trained in how to do research, but not in how to achieve impact” (p. 450). Despite the reservations concerning the impact agenda, Belfiore argues that attacks from within the academy on this policy development may indeed arise from self-interest. When the arts and humanities seek public funding, “it is simply no longer tenable to make intrinsic value or self-improvement arguments that can be rejected for their self-serving nature” (Benneworth, Citation2015, p. 6).

Belfiore suggests as an alternative to simple rejection that impact be re-defined and expanded beyond its current status as a single proxy by which the value of arts and humanities research is judged. Drawing on Michaels’ trope the master story is economic (Michaels, Citation2011, p. 9), she makes the case for an expanded view of ‘impact’ beyond economic measures. Indeed, researchers now increasingly agree that understanding research impact in economic terms is too narrow an approach (Belfiore, Citation2015; Esko & Miettinen, Citation2019; Muhonen et al., Citation2019) and that multiple approaches need to be developed, including social, cultural and environmental. This understanding of varying criteria for what is considered impact is stated also in European research policies (Science Europe, Citation2017, p. 7). Alternative readings of research impact emphasize that it is not only a contribution to the store of knowledge of a discipline, or economic, it may also “…embody broader public value in the form of social, cultural, environmental and economic benefits (Donovan, Citation2011, p. 178).

Arts education research policy has been active in making arguments for the value of the arts and reporting the impact of arts initiatives (see for example Hodges & Luehrsen, Citation2010), however, there has been less discussion concerning the ways in which impact and the public value of research in the field could be defined and evaluated. Despite the fact that most likely all arts and arts education researchers want their research to communicate and to be read, there has been little discussion of the ways in which the arts education research community might respond to the impact agenda and how it might change research practices and education in general and doctoral studies in arts education, in particular. In this article, we seek to redress the lack of debate outlined above. Specifically, whilst we pose reservations to the economic master story of research impact assessment, we consider the potential benefits of the impact agenda by providing an overview of narrative-based approaches that seek to encompass multiple indicators to presenting research impact.

Impact narratives are a relatively new form of analyzing and assessing the input-output relationships of research processes providing an alternative to existing and long-standing quantitative measures. Katrakazis et al. (Citation2018) draw on the OECD’s (Citation2002) distinctions between outputs, outcomes and impact in research evaluation as follows:

“outputs are products or services directly produced by an activity. An outcome is a short-to-medium term effect, generally finite and measurable, that can be attributable to outputs. By contrast, impact is a long-term effect that takes place on a broader scale, as a result of an outcome. Impact may be positive or negative, intended or unintended, direct or indirect” (Katrakatzis et al., Citation2018, p. 451).

In what follows, we draw on these distinctions and understand impact narratives to include (1) outputs and outcomes as identifiably related to researcher’s activities and (2) impact as the wider effects existing in the narrative writing which aims at orienting directions for particular activities and events. Through an analysis of our own experiences of writing narrative impact statements in Australia and Finland respectively, we suggest that engaging in impact assessment exercises may indeed push the researcher out of comfort-zones but in doing so can also provide a learning process that draws on professional reflexivity and may contribute to professional transformation. We will concentrate on the constructive potential of impact narratives, in particular, in framing arts education researchers’ work from a wider societal perspective. Specifically, we suggest that re-configuring the role of impact narratives for arts education researchers from a funding obligation that is imposed to an opportunity for ‘narrative learning’ (Goodson et al., Citation2010) may serve as an affordance for the re-professionalization of researchers in the field of arts education. Such an approach supports one of the tenets of professionalism, that is, developing a “proper understanding of the social responsibility of a profession” (Minnameier Citation2014, p. 58). In this way the article seeks to demystify impact assessment and encourages arts education researchers to consider the use of narrative tools when exploring new ways to articulate the impact of their research.

Narratives and narrative learning

Bruner’s distinction between two modes of thinking, the paradigmatic and the narrative underpins the growth of narrative as a form of inquiry, meaning-making, and learning (Bruner, Citation1986). For Bruner, narratives function in a range of ways including as a form of reporting, as a meaning-making tool, and as a self-making strategy (Bruner, Citation1990, Citation1991, Citation2003). Drawing on Bruner’s work, narratives have been described as storied accounts of human experience, shaped by place, relationships and temporality (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000), that seek to make meaning of social encounters and sequences of events (Goodson & Gill, Citation2011, p. 4). Narratives may be drawn on as a research ethos, a methodological choice, and/or a reporting strategy (Barrett & Stauffer, Citation2009, Citation2012). In our day-to-day communication we constantly draw on the storying qualities of narratives as they can convey meaning in more immediate and effective ways than can abstract principles (Schank & Berman, Citation2002). We suggest that “narrative rhetoric seeks to push forward a process of change in thinking, and hopefully in action” (Westerlund, Citation2020, p. 12; also Freeman, Citation2015). Writing about the characteristic features of research impact narratives, Penfield et al. (Citation2014) argue that

the use of narratives enables a story to be told and the impact to be placed in context and can make good use of qualitative information. They are often written with a reader from a particular stakeholder group in mind and will present a view of impact from a particular perspective. (p. 29).

Recent scholarship has emphasized the role that narratives play in learning (Clark & Rossiter, Citation2008; Goodson et al., Citation2010; Goodson & Gill, Citation2011), not only for the reader of the narrative but also for those developing the narrative. Describing narrative writing as ‘narrative learning’ Clark and Rossiter (Citation2008) describe a multi-faceted process where narratives or stories are used both as the “method” and the learning process itself. As individuals discover or create meaning through the process of narrating, they engage in identity work through the narration of an unfolding story shaped across a lifespan (Clark & Rossiter, Citation2008). Narrative construction can provide opportunities for looking backwards and forwards in the lifespan (see for example Freeman, Citation2010), re-shaping both past conceptions and future actions. Crucially, such narrative construction may provide an opportunity for ‘narrative learning’ in research environments and researcher education.

The arts and humanities constitute a set of disciplines that have separately and together told and critiqued the stories (Bate, Citation2011), large (Freeman, Citation2006) and small (Bamberg, Citation2004, Citation2010, Citation2011; Bamberg & Georgekopoulou, Citation2008) of human culture, environment, and society. We suggest that these skills have positioned arts and humanities researchers uniquely to engage with impact narratives. Whilst some are critical of a process that is seen to advantage those who can write effective narratives (Penfield et al., Citation2014, p. 30), we point to the work of Benneworth who argues that scholars in the arts and humanities in particular “…have much to be proud of and can be bold in seeking to demonstrate that – under the right conditions and with the right support – they can achieve just as much change in society as can their more technologically minded colleagues” (p. 6). We suggest that implicit in the use of narrative as a form for constructing and presenting research impact, arts education researchers have an opportunity to construct a broadened view of public value that is not limited to singular notions of what constitutes impact.

To illustrate some of the affordances and constraints of engaging with changing research policy concerning the role of impact assessments, we will draw on our own experiences of writing impact narratives in Australia and Finland respectively. In what follows we will

set the cultural context of the discussion through a description of the changing research policies that shaped the impact assessment in each country;

highlight some distinctive features of these processes: the first, focusing on a formative assessment that drafts a plot for future impact, the second focusing on a summative assessment of the impact of completed research activities – creating a plot out of past work.

reflect on the ways in which the orientation of the evaluation exercise (summative or formative) and the development of impact narratives by researchers may provide resources to rethink research processes, researcher careers and the training of future researchers.

Finally, we will discuss the implications and recommendations for arts education research and research education.

Materials and methods

In order to investigate the affordances and constraints for researchers of preparing impact narratives we have engaged in a process of collaborative autoethnography. Denzin (Citation2013) describes collaborative autoethnography as “the co-production of an autoethnographic text by two or more writers, often separated by time and distance” (p. 125). It is a process that “need to consider one more layer of intersubjectivity, namely among researchers” (Chang, Citation2013, p. 111) and in which data might include “…recalling, collecting artifacts and documents, interviewing others, analyzing self, observing self, and reflecting on issues pertaining to the research topic” (p. 113). In collaborative autoethnography the researchers utilize their autobiographical data as “a window into the understanding of a social phenomenon” (Chang et al., Citation2012), in this case the changing research practice in which impact narratives are introduced to arts education researchers.

In our application of collaborative autoethnography we began the process of re-telling and re-performing this significant professional life experience (Denzin, Citation2013, p. 126) through shared reflections and recollections of our experiences and memories of completing impact narratives in our respective institutions and countries. The dialogue brought to surface our understanding that the writing of impact narratives had been a learning experience and at the same time a demanding jump into the unknown. We then contextualized these discussions through the collection of documents including the official guidelines for the completion of impact narratives in our respective countries. This was done to illustrate the cultural and contextual differences between the two countries' research policy to pay attention to how the phenomenon as such has ‘subcultures’ and how our individual narrations arise from the first-order experiences and interpretations of these subcultures (Geertz, Citation1973). We then proceeded to write our separate narrative accounts in which we sought to analyze and document our recollected experiences of working with impact narratives. We then shared these narratives with each other inviting critical commentary and comparative analysis that sought to explore the intersubjectivity of our experiences (Chang, Citation2013).

This dialogic approach allowed us to “listen to each other’s voices” (Chang, Citation2013, p. 112) to realize what was contextual in the phenomenon and functioned “as a means of exploring the dynamic learning possibilities to be gained from a focus on the grounded character of workplace cultures” (Bissett et al., Citation2018, p. 255). Collaborative autoethnographic dialogue thus allowed us to better understand both the phenomenon itself, the country-specific differences in the practice, and our respective struggles and positions in relation to the phenomenon. In this article we provide the final versions of our reflective narrative accounts of experience and our collaborative analysis of the affordances and constraints of the experiences of writing research impact narratives in two different contexts.

Setting the policy context for narrating research impact: Case 1

The Australian Government released the National innovation and science agenda in late 2015. The agenda aimed to introduce a range of measures and actions “…to assist in boosting the commercial returns of publicly-funded research” (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2015). One of these measures was the establishment of a Research Engagement and Impact Assessment Framework. A trial Engagement and Impact Assessment (EI Assessment) was undertaken in 2017 in order to test the methodology and measures, with full implementation of the process in 2018. The methodology for demonstrating Engagement and Impact in Australia, like that of many international comparators, is based on the development of “Narratives” that address specific criteria and which are subsequently assessed by a panel of experts. In Australia, the Arts and Humanities panel undertakes this task with a panel comprised of subject expert researchers across a diverse range of the Arts and Humanities disciplines, and end-users of research.

The submission guidelines for the 2018 EI assessment in Australia state the aims of the exercise as a means to assess research contributions to “…the economy, society, environment or culture (our emphasis), beyond the contribution to academic research, and the ways in which universities have facilitated the translation of research into impact” (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2018, p. 8). Key to an understanding of the EI assessment in Australia are the definitions provided of Engagement and Impact, specifically:

Research engagement is the interaction between researchers and research end-users outside of academia, for the mutually beneficial transfer of knowledge, technologies, methods or resources.

Research impact is the contribution that research makes to the economy, society, environment or culture, beyond the contribution to academic research. (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2017, p. 10).

The guidance for researchers in preparing their impact study states the need for “explicit evidence” of “cost-benefit analysis” or “adoption of public policy that leads to changes in behaviour” (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2017, p. 19). Significant to this discussion, the guidelines stress that the content must be retrospective. In detailing what is required of the narrative the guidelines provide the following advice:

Provide a narrative (6000 characters) that clearly outlines the research impact. The narrative should explain the relationship between the associated research and the impact. It should also identify the contribution the research has made beyond academia, including:

who or what has benefited from the results of the research (this should identify relevant research end-users, or beneficiaries from industry, the community, government, wider public etc.);

the nature or type of impact and how the research made a social, economic, cultural, and/or environmental impact;

the extent of the impact (with specific references to appropriate evidence, such as cost- benefit-analysis, quantity of those affected, reported benefits etc.);

the dates and time period in which the impact occurred. (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2017, p. 47.)

A key element in the Australian framework is the inclusion of a section outlining the institutional approach that has facilitated and supported the research including infrastructure that supported the conduct, monitoring, and dissemination of the research.

Setting the Finnish policy context for narrating research impact: Case 2

In Finland in 2015 a new research funding scheme was introduced through the Strategic Research Council that aims to provide funding “to find concrete solutions to grand challenges that require multidisciplinary approaches” and promote “active collaboration between those who produce new knowledge and those who use it” (https://www.aka.fi/en/strategic-research-funding/src-in-brief/). The funded projects consequently are selected not only through a review of their scientific quality but also of their high societal relevance.

ArtsEqual was amongst the first projects to be awarded funding of 6,5 million euros for a six-year research involving five universities and research centers. The specific goals of ArtsEqual were (1) to identify the mechanisms that reproduce inequality in arts and arts education public services in Finland and (2) facilitate research interventions that increase equality and participation within the system (for more details, https://www.artsequal.fi/). The research was organized through 6 research groups each having their own sub-objectives and the researchers worked in varying contexts and groups, including established institutional as well as non-established institutional contexts for the arts such as hospitals, prisons and elderly care. By design, the project was expected to expand, and as of 2019 it had engaged over 90 part-time, full-time, or affiliated researchers, doctoral students and arts and arts education practitioners. Aligning with the Strategic Research Council guidelines that research should be conducted in close collaboration with various stakeholders, ArtsEqual has an agreement with over 50 interaction partners varying from national NGOs and individual schools to ministries and cities.

As a whole, the call of the Strategic Research Council exemplifies the wider turn in research culture and policy in Finland toward the ‘regime of public engagement’. According to Saltmarsh (Citation2017), in the ‘regime of public good’ public problems are predominantly shaped by specialized expertise and ‘applied’ externally ‘to’ or ‘on’ the community rather than with the community, whereas “the ‘public engagement regime’ means a wider turn toward a more intense, responsible and respectful collaboration’ (p. 9). The ‘public engagement regime’ does not perpetuate the existing institutional structures and cultures, but rather refers to a knowledge or learning regime “that necessitates institutional change and transformation” (p. 10). This shift underlies contemporary Finnish research policy and researchers are increasingly expected to search for change together with various stakeholders and to reconsider their own institutional practices and understandings of how research is conducted. The Strategic Research Council expects impact even on politics and active “interventions” in political decision-making processes.

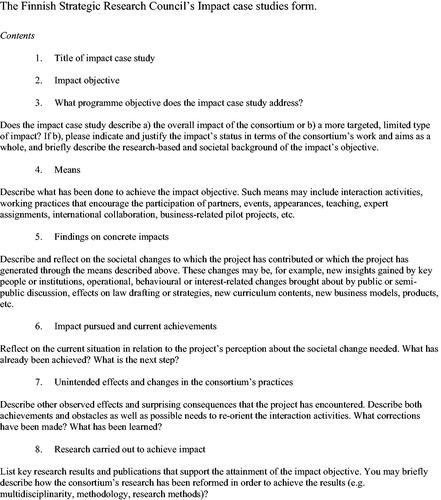

Consequently, the Strategic Research Council projects are monitored and evaluated over their lifespan in a different way than other projects. Continuing funding is conditional and subject to approval of the results of a mid-review. In this review, the commonly used quantitative indicators (e.g. number and ranking of publications, quantity of conference presentations, organized seminars and events including the number of participants etc.) are used, however, each consortium had to prepare 3-5 impact narratives (each max six pages) and update them twice a year during the entire period the consortium is active. If requested, the consortium had to provide evidence of actions and achievements presented in the narratives. This impact assessment follows the strategy of the national public funder of research that makes a distinction between research quality, the renewal of science and research and “the effects and impact in the scientific community and beyond academia” (https://www.aka.fi/en/research-and-science-policy/effects-and-impact-of-research/. Importantly however, the Academy of Finland’s definition for impact is open-ended and allows discipline-specific understanding of what impact might mean.

The impact narratives requested from the Academy’s Strategic Research Council projects have a general guided format and the funder encourages the consortia to publish their impact narratives on their home pages (see ). Importantly, the Academy of Finland general guidelines align with the recent European level (Science Europe, Citation2017) understanding where it is admitted that there is an urge for the right balance to let both the predefined objectives of research and its actual, often unintended, outcomes emerge and where effects can be seen as occurring only after a long time span. Moreover, the monitoring and review of research impact “must show the process instead of simply listing its results” (https://www.aka.fi/en/research-and-science-policy/effects-and-impact-of-research/).

Findings

Commonalities and differences in research impact assessment

Each approach to research evaluation is intent on understanding the impact of research on the broader society, but there are some notable differences between country-specific contexts. For example, the Australian approach emphasizes evidence of “cost-benefit analysis” or “adoption of public policy that leads to changes in behaviour” (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2017, p. 19), an approach that might be viewed as a “top-down” perspective on social change. By contrast, the Finnish approach seeks to understand how population behaviors are changed through public engagement in the research process, a “bottom-up” approach which might subsequently lead to changes in public policy.

In terms of process, one of the key differences we identify in the Finnish and Australian approaches to research impact evaluation is the temporal orientation of the narrative approach. In the Finnish experience, researchers are asked to look forward to considering the potential and desired impacts of their work. This requires more than a simple statement of the projected research outcomes and outputs of the project. Rather, such looking forward asks researchers to look outwards to the wider society in order to identify for whom, in what settings, and how the research and researchers’ activities will impact the lives of individuals, groups, communities, institutional structures as well as policy-making and political decision-making. Such an approach not only impacts the ways in which the research is taken up, it also shapes the design, the motivations, and the impetus of the research we suggest. It impacts the way researchers need to plan their own involvement with people, institutions and the society beyond actual research activities. By contrast, the backwards orientation of the Australian approach asks researchers to make meaning of the ways in which their research has been taken up by others, a process that draws on evidence (‘how the research made a social, economic, cultural, and/or environmental impact’) and in a process replete with ‘hindsight’ allows for a particular kind of meaning-making. We explore this issue in the two vignettes below.

Looking backwards: Meaning through impact narratives

Vignette 1.

Early in March 2017 I was appointed a discipline leader for the pilot Engagement and Impact Assessment exercise at my institution, focusing specifically on Impact. The task of the discipline leader was to write an Impact “story”, in my case focusing on the 19 code sub-strand of Studies in Creative Arts and Writing (1904), and to undertake the first draft of this within a week. Institutional advice recommended use of the templates provided by the ERA Guidelines, with equal attention paid to the impact and the institutional approach to impact, and consideration of the evidences that could be supplied to support the Impact story. The Institutional process outlined to discipline leaders included review of the initial stories submitted by an Institutional research committee, subsequent selection of those stories that were to be developed further, and continuing work with the writer of that story to refine prior to submission some 6 – 8 weeks later.

The institution provided access to data and reports that had been developed through iterations of the ERA exercises conducted in 2012 and 2015 respectively, and summaries of impact stories that had been developed for a range of institutional purposes. This information was useful in foregrounding what was viewed as newsworthy in the discipline in general and the researcher work specifically, and the ways in which institutions draw on these in public engagement and discourse.

The reference period for the impacts was January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2016 with associated research dating back to January 1, 2002 allowed. Consequently, the 15-year period covered several major research projects in three key areas of research: children’s learning and engagement in music; the pedagogies of creativity and expertise; and narrative inquiry. These projects were supported by nationally competitive grants from the Australian Research Council through the ARC Discovery and Industry grants schemes, in excess of $1.2 million (AUD). The preparation of the impact narrative therefore prompted a retrospective analysis of a research career whilst also seeking to identify an overarching or unifying theme to that career. What might have been viewed at the time as a series of serendipitous episodes shifting between the research interests outlined above began to be shaped as a continuous, connected thread of research interests and activities. Accessing and analyzing examples of impact narratives written for previous iterations of the UK Research Excellence Framework, provided some models. Accessing a number of these was helpful in seeing how others were able to create a coherent narrative that drew together a series of seemingly independent studies to create a “life-story” of impact across a range of projects rather than a singular focus on one project.

In shaping an impact narrative looking beyond the academic discipline avenues for the dissemination of research (articles, book chapters, conference papers) also provided material and models that might be useful. For example, commissioned research projects from government, charitable and not-for-profit organizations present opportunities to provide reports to diverse audiences including government, boards, funding bodies, donors, and participant communities. The preparation of reports for these diverse audiences in a range of formats (for example, Board presentations, participant organization briefings, industry partner workshops, donor events, press releases, and media presentations) provide significant learning in how to craft and present the impact of research. Unintentionally such presentations had elicited feedback both formal and informal from research commissioners, funders, and end-users which, with their approval, could be drawn on as evidence of research impact “…to the economy, society, environment or culture, beyond the contribution to academic research”. (ERA, 2017a, p. 10). The final impact narrative accordingly drew on various sources including an academic research record, CV, media commentary, industry and partner accounts of the uses of the research findings, institutional media releases and reports.

Freeman asks how we might study the lives of others in ways that are responsible, valuable and legitimate. He identifies issues that need to be considered in such a venture including: “…the reliability of memory, the relationship between language and personal identity, the nature of life historical ‘facts’, the problem of interpretation…” (Citation2010, p. 25). These issues are no less important when reflecting on our own lives and work. Undertaking this life perspective began to reveal the ways in which separate projects and activities contributed to an emerging research impact narrative theme, improving learning and life outcomes for children and young people through music.

Working in the Australian research assessment environment writing an impact narrative prompts researchers to look ‘backwards’ over a 15-year period of research in order to identify the impact, meaning and purpose of their research for others. The retrospective focus provides one means of constructing a life in and through research. Importantly, looking backwards may provide a focus for looking forwards, a form of hindsight (Freeman, Citation2010) that might shape future research directions.

Looking forwards: Change through impact narratives

Vignette 2.

Reflecting on this in hindsight, I can see that the Strategic Research Council indeed did not predefine the paths of impact for us. Since we were amongst the first projects chosen to be funded under this new program, we had no models for impact narratives, only a few examples and a task to think for ourselves. Although impact narratives were officially for monitoring how the project managed its aim to have an impact beyond academia, they were informally introduced and practically functioning as tools for planning, since we had to start writing them parallelly with the planning of concrete research activities. The narratives were meant to be changing and evolving, and unexpected, even negative outcomes and failures were instructed to be reported as a sign of critical self-reflection and honesty.

Many questions arose right in the beginning of the work. One of the biggest questions seemed to be if we knew well enough the societal processes where our professional knowledge could be useful considering that we were also expected to influence political decision-making. This led us to reflecting the discourses used by researchers and to finding the language that works outside the academia. But we also soon had to ask how actively we should search for interaction with the wider public and politicians without this becoming obsessive and self-serving advocacy of the project? Balance had to be created with research and this new public work. Moreover, the impact narratives were meant to be collaboratively written, which meant that nearly 40 researchers during the first year, and 3 years later over 90 researchers, artists and arts educators, had to be involved in one way or another in shaping the impact narratives. For myself, an important question was, how are the included music education researchers and doctoral students educated to contribute designing for and documenting impact as the project’s research proposal and general interaction plan provided only starting points for their work? This led us to searching for existing tools and experimenting with new approaches in doctoral studies.

A central shift of perspective was that researchers were now expected to act as important societal agents towards institutional and societal change. The aims of ArtsEqual did not assume neutrality from researchers but rather making a transformational difference in a noticeable way as ‘public professionals’ (McCollough, Citation1991). The impact narratives were a way to demonstrate how this difference was thought to take place, what actions were taken, and what processes were initiated by researchers. However, as we soon noticed, the institutions do not necessarily want similar change as researchers and policy makers even when the change is about such a moral issue as equality. Secondly, the funder wanted the impact narratives to be published, however, not all interventions or consequences of research interaction can be public. For instance, research may involve interaction in which it is important that the stakeholder, whose identity is generally known, takes pride in effecting change instead of researchers, even when the researcher has clearly been the facilitator; or when the impact cannot be discussed publicly because the narrative exceeds the phenomenon (e.g. vulnerable groups or individual asylum seekers that have been involved with the research activities) that is covered by the ethical permissions for the research. Important evidence of impact could also be in a form of private emails that were not meant to be shared. Third, during the process it became also evident that since the project included more and more researchers it was difficult to gather all potential paths for impact and include all details in the limited space of the narratives. Fourth, the danger of forcing non-linear processes in the process of writing into simple linear success stories just to please the funder was identified as one of the biggest challenges. Another challenge was to keep the ongoing research in the story which aimed to cover the main activities towards an impact in society during the 6 years.

After the first shock when the nature of this new research funding form started becoming clearer the levels of intended impact started emerging in numerous shared collegial discussions between the group leaders. We had to ask repeatedly, what it was that we really wanted to achieve beyond academic interests and publications. The narratives started functioning as shared reflexive platforms. Consequently, the project produced one metanarrative that deals with the impact and major activities of the whole consortium and three impact narratives that were more detailed and that clearly differ in their objectives, each ending up being 6 pages long. Compromises had to be made to balance between addressing the main foci of the consortium and the numerous individual projects that increased month after month as more researchers wanted to affiliate with the nationally significant project. The process of crafting the narratives forced us into a process of reflexive selection in which smaller incidents, such as a meeting with a minister, could appear as important in terms of dissemination, whereas for instance an organized seminar was of less importance in the narrative. With some stakeholders the work towards change was harder because of the expectation that research should only support the existing status quo. In these cases, the long timeline of the project gave a possibility to change strategies several times in order to move towards the impact goals. However, due to the above-mentioned ethical reasons, the narratives have not yet been published on the project homepage and a public version is still in progress.

As most of the music education doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers of the coordinating university became affiliated with this project, societal impact became a regular topic in educational events. The exercise of writing impact narratives widened the interest of doctoral studies in which the perspective of scholarly knowledge contribution in the international field of music education had been central. Identifying collaborative partners and the nature and frequency of interaction as well as improving communication skills in non-academic arenas were included as part of the doctoral studies that already had been developed over the years with the idea of critical research, collaborative practice and international impact (see, Westerlund, Citation2014, Citation2020; Westerlund & Karlsen, Citation2013). New tools were introduced to the doctoral studies of music education to help early career researchers in planning this aspect of their studies. It was also necessary to accept that all are not equally comfortable in moving towards the ‘regime of public engagement’ in which academic work is carried out along with the public, and that individual researchers need to have space to find their own way to think about and make an impact. However, the request to think about impact beyond publications clearly activated the doctoral students and younger generation researchers in particular whose visibility in public media has become regular.

In this article we suggest that the purposes of impact narratives are multiple including: a) working as tools in planning research activities against a widened understanding of “the social responsibility of a profession” (see, Minnameier, Citation2014); b) reflecting on one’s research work beyond academic publications and professional self-interest and in this way even redefining what is could mean to be a ‘system expert’ that builds cooperation with the local environment (Mieg & Evetts, Citation2018, p. 138); as well as c) using ‘moral imagination’ (McCollough, Citation1991) to find ways to make a difference and fulfilling a public service and ethical responsibility to ensure communication of the outcomes of research to the maximum number of prospective users. This last acknowledges the ethical responsibilities of researchers, particularly when undertaking research that has been funded by government and other public entities such as not-for-profit and charitable organizations.

Whilst the focus on narrative as the primary means of identifying, constructing, evidencing, and presenting impact as a shared understanding of the public value of the research work is a common factor, as we noted, contextual and national differences on how research impact narratives are constructed and the categories reported are evident. These differences contain their own affordances and constraints. For example, the Australian approach which looks back over a 15-year span in order to provide a summative assessment of research impact tends to focus the narrative on the research outputs and contributions of individual researchers and their teams, reflecting on a body of work. By contrast, the Finnish experience takes a formative approach to impact assessment, thereby shaping the design of the funded research project, and requiring researchers to actively plan for a range of activities toward a variety of impacts (e.g., academic, artistic, educational, cultural, economic, environmental, policy, political and social) in their work during the project. It forces the researcher to shape oneself as a societal actor as well as a producer of knowledge and traditional research outputs such as journal articles and book chapters. In other words, the approach requires the researcher to move beyond the university walls (the ivory tower) to engage in public institutional collaborations and seek to participate in debates and discussions in public spaces. This process may be viewed as a form of education into public service as researchers are challenged variously to position their work in relation to the society at large retrospectively and prospectively. Further, in the Finnish experience, the open nature of the process in which researchers were asked to define and describe research/researcher impact rather than responding to standardized definitions and templates acknowledges discipline-specific differences, and provides opportunity to consider the value of the arts and arts education as a shaping force in constructing the research impact criteria.

Criticisms of narrative approaches to research impact assessment point to the possibility of drafting a story that lacks any “evidence required to judge whether the research and impact are linked appropriately” (Penfield et al., Citation2014, p. 29). Counterarguments to this view recommend that when “used in conjunction with metrics, a complete picture of impact can be developed, again from a particular perspective but with the evidence available” (p. 29). The problem seems to be that the metrics typically measure the scientific impact (e.g. the number of citations and the impact measures through the publishing forums) and it is often hard if impossible to provide evidence on such matters as change in public attitude or even change in academic discourse. In Finland researchers have been challenged to connect the quantitative metrics and information about research publications to those other activities (see vignette above) that researchers have conducted in order to engage in societal and political decision-making processes. Hence, arts education researchers together with artists could in the future contribute to developing tools to “adequately capture interactions taking place between researchers, institutions, and stakeholders, the introduction of tools to enable this would be very valuable” (Penfield et al., Citation2014, p. 28).

In the collaborative autoethnographic accounts presented above we have sought to demonstrate that developing impact narratives about our research and research activities is neither simply the listing of facts about publications and research outcomes nor does it necessarily mean prioritizing quantity or forced economical perspective, or even simple linearity; rather, it can be a meta-reflexive process where the researcher or research group has to put the work and activities into a larger societal frame and look strategically and wisely at the work beyond publications. This meta-reflexive process that develops self-understanding of researchers as public professionals covers not simply past action, it also seeks acknowledgement of current engagement by various stakeholders with the research, and crucially, possible scenarios for future research. The process of writing an impact narrative required in our case looking backwards (Australia) and looking forwards as well as backwards (Finland), however, both of them were re-constitutive processes in that retrospective analysis of research impacts shaped a narrative that had meaning in the present and was forward looking, whilst forward-looking analysis drew on the past and present contexts in order to make meaning. In the latter case, imagination was involved, and the emerging narratives started to direct activities and individual researchers’ and doctoral students’ thinking of their responsibility in the society (Westerlund, Citation2020). For both of us, the process prompted us to reconsider our roles as researchers to encompass that of public pedagogue engaged with society, reflecting what the difference might be in doing research and acting as a public professional.

As a caution, self-narratives can both reveal and conceal. Narratives might be fashioned to emphasize “heroic” narratives of success rather than narratives that critique (Penfield et al., Citation2014, p. 29). And this is perhaps one danger of the Impact Narrative agenda – that the only story to be told is one of success. The Finnish format for impact narratives provides an example where researchers are expected to be able to identify failures and unintentional negative impacts as well as success stories. This suggests a move beyond the laudatory, even heroic narratives focused on success that are required by national exercises such as the Australian EI assessment and similar initiatives in other nations.

Thus, whilst such reflexive processes when imposed by funders can be experienced as a controlling mechanism, and whilst there are certainly variations in what kind of limits for researchers’ self-definition are given by the funder, reflexive processes when writing impact narratives can be consciously taken as a form of professional learning. Moreover, one should not make the mistake to conflate the value of arts education or arts education research to impact assessment, constructing impact narratives. As with any stories of ourselves, they can be seen as a way to find new systems level meanings and directions that help us in better identifying and articulating not just funders but ourselves who we want to be as researchers in our societies and why we do what we do. Indeed, exercises on how to plan impact can even support a more systematic development of an activist, community-oriented and forward-looking professional attitude (Westerlund, Citation2020).

Concluding remarks

This collaborative autoethnographic study shows that constructing impact narratives of and for one’s research work can be taken as effective in promoting learning and reflection on the researcher’s work in the society. Moreover, it has demonstrated that storying can point to the future equally as to the past activities, and drafting impact narratives can be seen as a way to learn in a situation where the changes in research policy demand greater commitment to a mindset of ongoing professional learning and professional transformation. Such learning and re-thinking of one’s profession might include developing new skills, searching for new relationships with various stakeholders, and using an extensive knowledge base beyond simple dissemination of research results. Indeed, it can pave way for a more activist professional stance as in the case of ArtsEqual (Westerlund, Citation2020).

Given the potential of impact narratives as a narrative learning tool for professional transformation in arts education research we identify three key recommendations for the higher arts education research education sector. First, we recommend that these present changes in knowledge regimes be introduced as an element of doctoral studies. Several guidelines for how to plan societal impact as an individual researcher exist online and can be further developed to suit arts education in particular. Thinking forwards in this respect gives tools to plan activities that look beyond the research process to its dissemination, thereby popularizing the results, building the researcher's emerging networks, and presenting public pedagogy.

Second, we recommend that narrative learning and narrative writing be introduced as a research training strategy for researcher identity construction and future public engagement. This is important not simply to develop skills for applying for grants, but also to assist future researchers to identify their position and responsibilities in the changing society and to find diverse, individually meaningful ways to make an impact. We may reconsider how doctoral students are led to “identify, communicate, and reward the impact produced by research, by taking into account the broader value that research activities bring to society” (Science Europe, Citation2017, p. 16). As Penfield et al. (Citation2014) suggest,

developing systems that focus on recording impact information alone will not provide all that is required to link research to ensuing events and impacts, systems require the capacity to capture any interactions between researchers, the institution, and external stakeholders and link these with research findings and outputs or interim impacts to provide a network of data. (p. 30)

The above highlights the collaborative possibilities and imperatives of research emphasizing that, “research is a collaborative system that generates a variety of effects” and “societal outcomes” (Science Europe, Citation2017, p. 16). This suggests that collaborative narration of impact when practiced over a longer period of time can enhance narrative learning for a whole institution and research field including the partners of collaboration.

Thirdly, we recommend that policy makers and funders recognize the multi-dimensional potential of narrative impact. “Impact assessment is about understanding those pathways and processes that bring about societal impact, rather than the monetary value of science, and it accordingly needs a non-linear approach” (Science Europe, Citation2017, p. 16). Brewer notes “…the suggestion that impact is a sheep in wolf’s clothing – that it looks more hazardous than it really is – is widely accepted within the policy evaluation tradition” (Citation2011, p. 255). As noted at the commencement of this article, the narrative structures that underpin much of the arts and humanities disciplines position researchers in these disciplines to engage with impact narratives. As the same skills developed in one’s research journey can be used to respond to the challenges of developing impact (Hall et al., Citation2019, p. 3), we suggest that arts education researchers draw on the resources of their disciplines as an affordance in developing and evaluating the impact of their work for society and take an active stance in contributing to the policy discussions on research impact.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bamberg, M. (2004). Talk, small stories, and adolescent identities. Human Development, 47(6), 331–355. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000081036

- Bamberg, M. (2010). Who am I? Narration and its contribution to self and identity. Theory and Psychology, 2(1), 1–22.

- Bamberg, M. (2011). Who am I? Big or small—shallow or deep? Theory and Psychology, 21(1), 1–8.

- Bamberg, M., & Georgakopoulou, A. (2008). Small stories as a new perspective in narrative and identity analysis. Text and Talk, 3, 377–396.

- Barrett, M. S., & Stauffer, S. (Eds.). (2009). Narrative inquiry in music education: Troubling certainty. Springer.

- Barrett, M. S., & Stauffer, S. L. (Eds.). (2012). Narrative soundings: An anthology of narrative inquiry in music education. Springer.

- Bate, J. (2011). Introduction. In J. Bate (Ed.), The public value of the humanities (pp. 1–14). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Belfiore, E. (2015). Impact’, ‘value’ and ‘bad economics’: Making sense of the problem of value in the arts and humanities. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 14(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022214531503

- Benneworth, P. (2015). Putting impact into context: The Janus face of the public value of arts and humanities research. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 14(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022214533893

- Bissett, N., Saunders, S., & Bouten Pinto, C. (2018). Collaborative autoethnography: Enhancing reflexive communication processes. In T. Vine, J. Clark, S. Richards, & D. Weir (Eds.) Ethnographic research and analysis: Anxiety, identity and self (pp. 253–272). Palmgrave MacMillan.

- Brewer, J. D. (2011). The impact of impact. Research Evaluation, 20(3), 255–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3152/095820211X12941371876869

- Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/448619

- Bruner, J. (2003). Making stories: Law, literature and life. Harvard University Press.

- Chang, H. (2013). Individual and collaborative autoethnography as method. In S. H. Jones, T. E. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of authoethnography (pp. 107–122). Routledge.

- Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F., & Hernandez, K. (2012). Collaborative autoethnography. Left Coast Press.

- Chubb, J., & Watermeyer, R. (2017). Artifice or integrity in the marketization of research impact? Investigating the moral economy of (pathways to) impact statements within research funding proposals in the UK and Australia. Studies in Higher Education, 42(12), 2360–2372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1144182

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass.

- Clark, M. C., & Rossiter, M. (2008). Narrative learning in adulthood. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2008(119), 61–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.306

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2015). National Science and innovation agenda. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/July%202018/document/pdf/national-innovation-and-science-agenda-report.pdf?acsf_files_redirect.

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2017). Australian Research Council - EI 2018 Framework.

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2018). Australian Research Council - EI 2018 Framework. https://www.arc.gov.au/engagement-and-impact-assessment/ei-key-documents

- Denzin, N. (2013). Interpretive autoethnography. In S. H. Jones, T. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 123–142). Left Coast Press.

- Donovan, C. (2011). State of the art in assessing research impact: Introduction to a special issue. Research Evaluation, 20(3), 175–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3152/095820211X13118583635918

- Esko, T., & Miettinen, R. (2019). Scholarly understanding, mediating artefacts and the social impact of research in the educational sciences. Research Evaluation, 28(4), 295–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz018

- European Commission. (2014). Guidance for evaluators of horizon 2020 proposals. http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/pse/h2020-evaluation-faq_en.pdf

- Freeman, M. (2006). Life “on holiday”? In defense of big stories. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 131–138.

- Freeman, M. (2010). Hindsight: The promise and peril of looking backwards. Oxford University Press.

- Freeman, M. (2015). Narrative as a mode of understanding: Method, theory, praxis. In A. De Fina & A. Georgakopoulou (Eds.), The handbook of narrative analysis (pp. 21–37). Wiley- Blackwell.

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. Basic Books.

- Goodson, I. F., & Gill, S. R. (2011). Narrative pedagogy. Life history and learning. Studies in Postmodern Theory of Education 386. Peter Lang.

- Goodson, I. F., Biesta, G. J. J., Tedder, M., & Adair, N. (2010). Introduction: Life, narrative and learning. In I. F. Goodson, G. J. J. Biesta, M. Tedder, & N. Adair (Eds.), Narrative learning (pp. 1–14). Routledge.

- Hall, G., Morley, H., & Bromley, T. (2019). Uncertainty and confusion. The starting point for all expertise. In K. Fenby-Hulse, E. Heywood, & K. Walker (Eds.), Research impact and the early career researcher. Lived experiences, new perspectives (pp. 3–18). Routledge.

- Hazelkorn, E. (2015). Making an impact. New directions for arts and humanities research. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 14(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022214533891

- Hodges, D. A., & Luehrsen, M. (2010). The impact of a funded research program on music education policy. Arts Education Policy Review, 111(2), 71–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10632910903458854

- Katrakazis, T., Heritage, A., Dillon, C., Juvan, P., & Golfomitsou, S. (2018). Enhancing research impact in heritage conservation. Studies in Conservation , 63(8), 450–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2018.1491719

- McCollough, T. E. (1991). The moral imagination and public life: Raising the ethical question. Chatham House.

- Michaels, F. S. (2011). Monoculture: How one story is changing everything. Kamloops, BC: Red Clover Press.

- Mieg, H. A., & Evetts, J. (2018). Professionalism, science, and expert roles: A social perspective. In K. A. Ericsson, R. R. Hoffman, A. Kozbelt, & A. M. Williams (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (pp. 127–148). Cambridge University Press.

- Minnameier, G. (2014). Moral aspects of professions and professional practice. In S. Billett, C. Harteis, & H. Gruber (Eds.), International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning (pp. 57–77). Springer.

- Muhonen, R., Benneworth, P., & Olmos-Peñuela, J. (2019). From productive interactions to impact pathways: Understanding the key dimensions in developing SSH research societal impact. Research Evaluation. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz003

- OECD. (2002). Glossary of key terms in evaluation and results based management. https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/dcdndep/39249691.pdf

- Penfield, T., Baker, M. J., Scoble, R., & Wykes, M. C. (2014). Assessment, evaluations, and definitions of research impact: A review. Research Evaluation, 23(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvt021

- Reale, E., Avramov, D., Canhial, K., Donovan, C., Flecha, R., Holm, P., Larkin, C., Lepori, B., Mosoni-Fried, J., Oliver, E., Primeri, E., Puigvert, L., Scharnhorst, A., Schubert, A., Soler, M., Soos, S., Sorde, T., Travis, C., & Van Horik, R. (2018). A review of literature on evaluating the scientific, social and political impact of social sciences and humanities research. Research Evaluation, 27(4), 298–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvx025

- Saltmarsh, J. (2017). A collaborative turn: Trends and directions in community engagement. In J. Sachs & L. Clark (Eds.), Learning through community engagement. Visions and practice in higher education (pp. 3–15). Springer.

- Schank, R. C., & Berman, T. R. (2002). The pervasive role of stories in knowledge and action. In M. C. Green, J. J. Strange, & T. C. Brock (Eds.), Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations (pp. 287–313). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Science Europe. (2017). Symposium report. Building a scientific narrative on impact and societal value of science. D/2017/13.324/6. https://www.scienceeurope.org/media/z5gmrp15/se_sac_symposium_report_2016_final.pdf

- Thomas, R. (2018). Questioning the assessment of research impact. Illusions, myths and marginal sectors. Palgrave Critical University Studies. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Westerlund, H. (2014). Learning on the job: Designing teaching-led research and research-led teaching in a music education doctoral program. In S. Scott Harrison (Ed.), Research and research education in music performance and pedagogy (pp. 91–103). Dordrecht: Springer (Landscapes: The Arts, Aesthetics, and Education).

- Westerlund, H. (2020). Stories and narratives as agencies of change in music education: Narrative mania or a resource for developing transformative music education professionalism? Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter, 223, 7–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5406/bulcouresmusedu.223.0007

- Westerlund, H. & Karlsen, S. (2013). Designing the rhythm for academic community life: Learning partnerships and collaboration in music education doctoral studies. In H. Gaunt & H. Westerlund (Eds.), Collaborative learning in higher music education (pp. 87–99). Farnham, UK: Ashgate.