Abstract

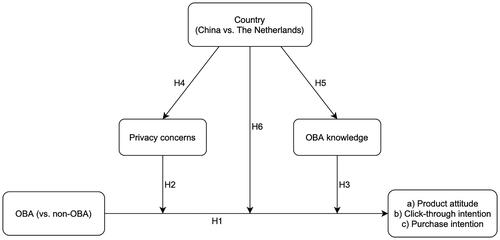

The present study aims to address (1) the extent to which privacy concerns and online behavioral advertising (OBA) knowledge as consumer characteristics create boundary conditions for the persuasiveness of OBA and (2) if their roles in OBA effects differ for Dutch and Chinese individuals. Results from an online experiment (N = 241) show that OBA is less effective for individuals with high privacy concerns than for individuals with low privacy concerns, while level of OBA knowledge does not influence the positive effects of OBA compared to non-OBA. OBA is also more effective for Dutch consumers than for Chinese consumers, which could be attributed to the finding that Chinese consumers have higher privacy concerns than Dutch consumers.

As of 2022, people on average spend almost seven hours per day online (We Are Social Citation2022). Meanwhile, their online activities are being tracked, and a large amount of personal information is being stored. Using these data, advertising networks can compose user profiles and create ads that are more likely to match the interests of individual users. This technique is called online behavioral advertising (OBA; Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017).

There has been a considerable amount of research on the persuasiveness of OBA. It has been reported to increase click-through intentions and rates, as well as purchase intentions and actual purchasing behaviors (Aguirre et al. Citation2015; Aiolfi, Bellini, and Pellegrini Citation2021; Lambrecht and Tucker Citation2013; Matz et al. Citation2017; van Doorn and Hoekstra Citation2013). Meanwhile, it is important to note that OBA outcomes are contingent upon several factors. A literature review by Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius (Citation2017) identified that OBA outcomes partly depend on consumer-controlled factors, which include knowledge and abilities, perceptions, and consumer characteristics. Furthermore, they pointed out that privacy concerns are one of the most important consumer characteristics that can influence the outcomes of OBA. Numerous studies have shown that privacy concerns negatively affect advertising effectiveness (e.g., Aiolfi, Bellini, and Pellegrini Citation2021; Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Ham Citation2017; Jung Citation2017; Ryu and Park Citation2020). Most of these studies theoretically positioned privacy concerns as a temporary state triggered by ad personalization practices. However, individuals may also differ in their general tendencies of being concerned over their privacy, which makes us wonder whether and to what extent privacy concerns as a trait create boundary conditions to OBA outcomes. Therefore, we are interested in examining whether the effects of OBA differ for individuals with high versus low privacy concerns. Another important consumer-controlled factor that might influence OBA effectiveness is consumers’ knowledge about OBA. Recent studies showed that people are familiar with this type of advertising (Kozyreva et al. Citation2021) and have a good understanding of it (Segijn and van Ooijen Citation2022), whereas more empirical evidence is needed on whether and how knowledge could affect OBA outcomes (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). Given the covert nature of OBA, it is plausible to suggest that those who possess more knowledge about the mechanism behind the scenes might evaluate the ad differently than those who lack such knowledge. Therefore, the first aim of the current study is to examine to what extent privacy concerns (as a trait) and OBA knowledge function as boundary conditions of OBA persuasiveness.

As privacy concerns and OBA knowledge are both consumer characteristics, they might differ among consumers from different parts of the world. Consequently, there might also be differences in OBA effectiveness across different countries. Most studies in this field were conducted in a Western context; other consumer markets—for example, Asian markets—have received relatively less attention. Moreover, few studies compared the effects of OBA across different countries. In fact, a recent review of the OBA literature pointed out that cross-cultural comparison of the OBA effect is scarce and much needed (Varnali Citation2021). To enrich the OBA literature in the global context and provide cross-country comparisons, this study selects China and the Netherlands as the two countries of interest, as the former is a typical collectivistic country and the latter is a highly individualistic country (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov Citation2010).

We argue that the effects of OBA might differ between Chinese and Dutch people for three reasons. First, people in individualistic cultures tend to be more concerned about their privacy than people in collectivistic cultures (Chen and Tsoi Citation2011; Milberg, Smith, and Burke Citation2000; Smith Citation2001). The high privacy concerns could consequently reduce the acceptance of OBA and lead to negative evaluations of the ad (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Kim and Huh Citation2017). Second, Dutch and Chinese Internet users may possess different levels of knowledge about OBA, due to different OBA regulations and practices in the two countries. Third, consumers with individualistic cultural orientation tend to respond more favorably toward personalized persuasion compared to the ones with collectivistic orientation (Kramer, Spolter-Weisfeld, and Thakkar Citation2007). Given these reasons, the second aim of this study is to address the gap in the literature by comparing the levels of privacy concerns and OBA knowledge, as well as the effects of OBA among Chinese and Dutch consumers.

This study makes three contributions to the literature. First, we examine privacy concerns as a stable trait rather than a temporary state to focus on who responds to OBA more positively or negatively, which differs from the theoretical propositions of most previous studies. By doing so, we can better understand whether and how individual differences in privacy concerns can influence the effectiveness of OBA across different contexts. This also allows us to explore to what extent privacy concerns reduce the effect of OBA. Second, we respond to the call for more research on the role of consumer knowledge in OBA perceptions and responses (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). Such insights can deepen our understanding of the importance of persuasion knowledge in an OBA context. Third, we bring the discussion of OBA effect as well as the roles of privacy concerns and OBA knowledge to a global context, offering insights and explanations into how and why consumers in different countries might respond to OBA differently.

The findings from our study could provide valuable information to marketers and advertisers who operate globally regarding the effectiveness of OBA across different markets, enabling them to make the best decisions on the implementation of OBA. It would also inform policymakers on which factor plays a more important role to help consumers make informed decisions.

Theoretical framework

Conceptualization of OBA

OBA is defined as “the practice of monitoring people’s online behavior and using the collected information to show people individually targeted advertisements” (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017, 364). It falls under the category of personalized advertising. While personalized advertising refers to the marketing practice that delivers tailored ads to individuals based on any type of personal information, the distinct attribute of OBA is that it uses people’s online behavior to tailor the ads (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). Therefore, OBA is also called “online profiling” and “behavioral (re)targeting” (Varnali Citation2021).

OBA varies in formats and contents depending on the advertisers’ needs and the type of data being used (Kim and Huh Citation2017). The online consumer data that can be used for OBA include Website browsing data, location data, app use data, search history, purchase history, media consumption data, and communication content (Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2015).

The effect of personalization in OBA

Previous research has shown that personalized advertising such as OBA can outperform nonpersonalized advertising and drive positive advertising outcomes (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). For example, prior research showed that OBA can boost click-through intentions and rates (Aguirre et al. Citation2015; Bleier and Eisenbeiss Citation2015), purchase intentions (Aiolfi, Bellini, and Pellegrini Citation2021), and consumers’ attitudes toward advertising (Gao and Zang Citation2016; Xu Citation2006).

The positive effects of personalization in OBA can be explained by the high ad relevance perceived by consumers (de Groot Citation2022; De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2022; Kim and Huh Citation2017). According to self-referencing theory, people engage in more cognitive processing when the information is self-relevant (Rogers, Kuiper, and Kirker Citation1977). Because OBA utilizes people’s online behavior and personal data, the content of the ad is likely to be perceived by consumers as more personally relevant, which consequently could lead to better persuasion (De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2022; Jung Citation2017).

Prior research has well documented the positive effects of OBA on ad persuasiveness. Here, we hypothesize the main effect again to establish the foundation for testing potential moderators. We also believe it is useful to retest the effects that have been reported in the literature for replication purposes. In this study, ad persuasiveness is operationalized as product attitude, click-through intention, and purchase intentions. Product attitude represents the attitudinal response toward the product, while click-through intention and purchase intentions indicate the behavioral responses toward the ad and the product, respectively. The hypothesis is as follows:

H1: Compared to non-OBA, OBA leads to (a) more positive product attitude, (b) higher click-through intention, and (c) higher purchase intentions.

The role of privacy concerns

Because OBA involves the practices of collecting, using, and sharing personal data, it is generally associated with concerns about intruding on people’s privacy. Privacy concerns in our study are defined as “the degree to which a consumer is worried about the potential invasion of the right to prevent the disclosure of personal information to others” (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012, 63). They are the most mentioned concerns among consumers regarding personalized advertising as well as OBA specifically (Segijn and van Ooijen Citation2022; Strycharz et al. Citation2019).

Prior research has predominantly theorized privacy concerns as a state triggered by encountering OBA, subsequently leading to negative reactions toward the advertising, which implies that only when people see OBA do they start worrying about their privacy and dislike the ad (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Ham Citation2017; Kim and Huh Citation2017; Kim et al. Citation2022; Morimoto Citation2021). In the current study, we investigate privacy concerns as a relatively stable consumer characteristic. Kokolakis (Citation2017) differentiated between trait and state privacy concerns. State privacy concerns, which he refers to as privacy attitude, are one’s evaluation after assessing a specific privacy-related context, while trait privacy concerns are generic feelings that consumers have about their privacy and are not necessarily bound to specific contexts.

Either as a trait or as a state, research has shown that privacy concerns play a negative role in influencing advertising effectiveness. As a state, privacy concerns are negatively associated with ad attitude (Ryu and Park Citation2020) and ad acceptance (Limpf and Voorveld Citation2015). People who are concerned about their privacy are also more likely to show avoidance of OBA (Aiolfi, Bellini, and Pellegrini Citation2021; Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Ham Citation2017; Morimoto Citation2021). Similarly, the only two studies we found that incorporated privacy concerns as a trait in OBA effects found that for adolescents with high privacy concerns, OBA increases ad skepticism and decreases purchase intentions (Zarouali et al. Citation2017) and that consumers with higher privacy concerns spend less time on synced advertising compared to consumers with lower privacy concerns (Segijn, Voorveld, and Vakeel Citation2021).

This negative role of privacy concerns could be explained by psychological reactance theory, which postulates that when people feel their freedoms are restrained, they are motivated to resist such influence to regain their freedom and autonomy (Brehm Citation1966; Brehm and Brehm Citation1981). For individuals with high levels of privacy concerns, the personalized content in OBA can make them feel that they have little control over how much the advertiser knows about them and their freedom from being observed by companies is being threatened. Consequently, consumers would show reactance toward the ads, leading to lower ad persuasiveness (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Strycharz et al. Citation2019).

When an ad is not based on an individual’s online behavior, we do not expect privacy concerns to trigger any negative response in that individual, as the ad would not threaten that person’s control over personal privacy. However, in the case of OBA, the situation is rather complicated, because people might perceive OBA more positively due to high personal relevance, while privacy concerns may trigger negative responses. This phenomenon is referred to as the personalization paradox: Personalized ads can lead to both positive and negative marketing outcomes (Aguirre et al. Citation2015). Multiple theories, including privacy calculus (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977), information boundary theory (Stanton and Stam Citation2002), and acquisition-transaction theory (Thaler Citation1985), approached this question using the concept of cost-benefit evaluation. These theories all postulate that individuals will assess the potential benefits and costs of disclosing personal information and the result of the cost-benefit calculation is expected to predict their preferences and behaviors (Bol et al. Citation2018; Sutanto et al. Citation2013). For individuals with relatively low privacy concerns, when they are exposed to OBA the perceived benefit of personal relevance might outweigh the perceived cost of privacy invasion, leading to an overall positive preference toward the advertised product and potentially also positive behavioral tendencies (i.e., clicking on the ad and purchasing the product). On the contrary, for people who are highly concerned about their privacy, the perceived costs might outweigh the perceived benefits, leading to negative persuasive outcomes of OBA compared to non-OBA. Built upon these arguments, we hypothesize as follows:

H2: Privacy concerns moderate the relationship between OBA and (a) product attitude, (b) click-through intention, and (c) purchase intentions such that the effect of OBA (versus non-OBA) on ad persuasiveness is more positive for individuals with relatively low privacy concerns than for individuals with relatively high privacy concerns.

The role of OBA knowledge

As online behavioral ads are generated through a technically complex and rather covert process, consumers may vary in their level of knowledge about this practice (Ham and Nelson Citation2016). To understand how this knowledge might play a role in OBA effects, we situate it in the persuasion knowledge model (PKM) developed by Friestad and Wright (Citation1994). Previous studies distinguished between objective and subjective persuasion knowledge, where subjective persuasion knowledge is an individual’s self-assessment of how knowledgeable he or she is in identifying the persuasion attempt, and objective persuasion knowledge is the actual accurate knowledge about a persuasion tactic that an individual possesses (Carlson et al. Citation2009; Ham and Nelson Citation2016; Ryu and Park Citation2020). In this study, to form a meaningful comparison between consumers from two different countries, we focus on individuals’ objective persuasion knowledge about OBA practices, which includes knowing that the ad content is based on online personal data and how the data can or may be collected. In this article, we refer to this specific type of persuasion knowledge as OBA knowledge.

According to PKM, consumers’ knowledge about persuasion motives and tactics influences how they cope with the persuasive message (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). Previous studies have shown that consumers with high persuasion knowledge tend to process the persuasion message more critically and tend to be more skeptical toward the persuasion attempt (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Maslowska, Smit, and van den Putte Citation2013), have a more negative attitude toward the ad (Ryu and Park Citation2020), have lower purchase intentions (Hwang and Zhang Citation2018), and come up with more counterarguments (Amazeen and Wojdynski Citation2019). In the OBA context, research has found that persuasion knowledge is positively associated with the appraisal of the risks and benefits of OBA (Ham Citation2017). Consumers who lack OBA knowledge may not be fully aware that their online behavioral data are collected and used for ad personalization. Therefore, people with low levels of OBA knowledge might consider the costs lower than the benefits when seeing OBA, leading to a more positive response toward the ad. On the other hand, when an individual has adequate knowledge of OBA, this person is able to evaluate the persuasion attempt more thoroughly by assessing both the potential risks and benefits associated with the persuasion tactic of OBA (Ham Citation2017; Ham and Nelson Citation2016). We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

H3: OBA knowledge moderates the relationship between OBA and (a) product attitude, (b) click-through intention, and (c) purchase intentions such that the effect of OBA (versus non-OBA) is more positive on ad persuasiveness for individuals with relatively low OBA knowledge than for individuals with relatively high OBA knowledge.

Country differences in OBA practices and privacy

In this study, we compare the Netherlands and China in terms of people’s level of privacy concerns and OBA knowledge, as well as the persuasive effects of OBA. We suggest that there are important practical, legal, and cultural differences between these two countries that could influence these factors.

OBA practices differ between the Netherlands and China due to different laws and regulations. In the European Union (EU), which includes the Netherlands, the handling of online personal data is guided by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) issued in 2016 and the ePrivacy Directive in 2011. Under these regulations, Websites must receive consent from the user before collecting any personal information using cookies within the European Union. They are also required to provide information about data collection in plain language to users and make it easy for users to withdraw their consent.

In China, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which took effect in November 2021, mandates user consent and transparency in data collection. However, the law does not specify the exact practices companies need to comply with regarding the usage of cookies. Therefore, unlike Websites in the European Union, which are required by law to ask users for permission prior to the installation of unnecessary cookies (i.e., asking users to opt in), most Chinese Websites do not ask for permission to install cookies when users visit the Website (i.e., opt out). Usually, the privacy statement can be found only by clicking a link at the bottom of the Website, and the only way to stop sharing information with the Website is to deliberately delete cookies through the user’s own Web browser settings, instead of requesting the company to stop the collection directly.

Furthermore, the countries have different self-regulatory transparency measures. For example, many advertisers in the European Union participate in the self-regulatory program called “YourAdChoices” from the Digital Advertising Alliance (Citationn.d.). The program designed an icon to inform consumers when an ad uses online behavioral data to display targeted content. Moreover, when the user clicks on the icon, a page from the advertiser will pop up to explain how the ad was generated. On the contrary, online ads in China usually only display an icon that states “advertisement,” without specifying if consumers’ personal information is used. These different practices may influence both consumers’ privacy concerns and OBA knowledge.

Next to these practical and legal differences, there are relevant cultural differences between the Netherlands and China that could explain differences in privacy concerns between their citizens. The two countries are distinct in their cultural values, especially in the dimension of individualism-collectivism as proposed by Hofstede (Citation1980). People in individualistic societies are deemed autonomous and independent, while people in collectivistic societies are deemed members of a group (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov Citation2010; Triandis Citation2001). According to the Individualism Index (IDV; Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov Citation2010), the Netherlands is identified as a highly individualistic country (scoring 80 on the IDV, range of scores: 6–91) while China is a typical collectivistic country (scoring 20 on the IDV).

Scholars have argued that people in a highly individualistic culture might exhibit higher levels of privacy concerns than people in a collectivistic culture (Milberg et al. Citation1995, Milberg, Smith, and Burke Citation2000). As individualistic cultures value the personal space and privacy of individuals, people from such societies also tend to be more concerned about the potential invasion of their privacy. However, in countries with high collectivism, people’s privacy is of less importance, so privacy intrusion is more tolerated by people (Milberg, Smith, and Burke Citation2000). Empirical findings from multiple studies have confirmed that people in individualistic societies exhibit significantly higher privacy concerns than people in collectivistic countries (Chen and Tsoi Citation2011; Cho, Rivera-Sánchez, and Lim Citation2009; Li, Rho, and Kobsa Citation2022; Milberg, Smith, and Burke Citation2000; Wang, Xia, and Huang Citation2016; Yang and Kang Citation2015). Therefore, we offer a fourth hypothesis:

H4: Dutch people will show higher levels of privacy concerns than Chinese people.

Country difference in OBA knowledge

Furthermore, we expect that level of OBA knowledge also differs between the two countries. According to the European Commission (Citation2019), the majority of Dutch people are aware of the GDPR issued in 2016 and their rights protected by the regulation, making the Netherlands one of the countries with the highest level of knowledge regarding data protection in the European Union. Furthermore, a recent survey with a representative sample of the Netherlands revealed that more than 70 percent of Dutch adults are familiar with the collection, use, and sharing of information about their media behavior (Boerman and Segijn Citation2022). These statistics suggest that most Dutch people should be able to understand that advertising content can be based on online personal data and how OBA works in general. Meanwhile, the literature regarding Chinese consumers’ OBA knowledge is rather scarce. The only relevant study we found pointed out that Chinese respondents had little or insufficient knowledge about OBA (Wang, Xia, and Huang Citation2016). Thus, we hypothesize:

H5: Dutch people will show higher levels of OBA knowledge than Chinese people.

H6: The effects of OBA (versus non-OBA) on (a) product attitude, (b) click-through intention, and (c) purchase intentions are more positive for Chinese individuals than for Dutch individuals.

Methods

Design and sample

To test our hypotheses, we conducted an online scenario-based experiment with a single factor (OBA versus non-OBA) between-subject design. We recruited a convenience sample of participants from China and the Netherlands through the authors’ personal social media networks (n = 166) in the two countries. In addition, a recruitment ad was posted in the online laboratory of a university in the Netherlands (n = 75). The final sample consisted of 241 participants, of which 111 were Dutch and 130 were Chinese. The Chinese and Dutch participants did not differ in their gender distribution and online search frequency, but differed in age, education, and Internet usage; the Chinese sample was older, more highly educated, and had higher Internet usage. shows the exact statistics.

Table 1. Sample characteristics by country.

All research materials were first developed in English and then translated into Chinese and Dutch by native speakers. Both language versions were proofread by more than one native speaker.

Procedure

At the beginning of the study, participants were informed that the objective of the study was to gain insights into certain products and the effectiveness of advertisements. Upon agreeing to participate, participants were randomly assigned to one of the conditions. Then, they were instructed to read our cover story, view a fictitious shopping Web page, and browse a fictitious weather Web page. After being exposed to the stimuli, participants responded to the first part of the manipulation check (whether or not they noticed the ad) and questions measuring product attitude, click-through intention, and purchase intentions. Thereafter, participants finished the remaining questionnaire measuring privacy concerns, OBA knowledge, and the second part of the manipulation check. An attention check was included to ensure the quality of the responses. Control variables were measured at the end of the questionnaire. Finally, participants were debriefed.

Stimuli

We designed our stimuli based on the most common form of OBA, which is a personalized banner ad that displays a specific product that the consumer has recently viewed online (Kim and Huh Citation2017). We developed a cover story that was close to a real-life scenario where OBA is likely to occur, including browsing a product online and then being exposed to the OBA or non-OBA. Scenario-based experimental stimuli are commonly used for studying online personalized communication (Bol et al. Citation2018). In both conditions, participants read a short cover story, which asked participants to imagine that they were planning to buy a pair of sweatpants to wear at home. Participants were then asked to imagine that they searched for sweatpants online and visited an online shopping Website. Then, they were instructed to choose one pair of pants from six gender-neutral options to view more details, which led them to the fictitious product detail page. After viewing the product, participants were asked to imagine they needed to do grocery shopping and visited a weather Website to check the weather. Participants were then shown a fictitious weather Website that contained a banner ad. In the OBA condition, the ad displayed the same pair of pants that the participants just viewed. In the non-OBA condition, the ad showed a fanny pack that was irrelevant to the fictitious browsing history of the participants.

Measures

Privacy concerns

Privacy concerns were measured using a five-item scale from Baek and Morimoto (Citation2012). A sample item was “When I am online, I have the feeling that others keep track of what I click on and what Websites I visit.” The items were rated on 7-point scales and averaged to form a composite score (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree; α = .91; M = 5.57, SD = 1.19). Details of all measurement items and a correlation matrix of all continuous variables are listed in the Supplemental Material.

OBA knowledge

We measured OBA knowledge with five items derived from Strycharz (Citation2018). Participants were instructed to review the statements and decide whether the each item was true, then choose from answer options True, False, or I don’t know. An example item was “When I visit a Website, I see the same ads as someone else visiting that Website” (False). The number of correct answers was summed to represent the respondent’s level of OBA knowledge (M = 3.64, SD = 1.23).

Product attitude

Participants were asked to evaluate the product they saw in the ad on three 7-point semantic differential items: Bad/Good, Unsatisfactory/Satisfactory, and Unfavorable/Favorable (Lee, Park, and Han Citation2008). The items were averaged to form a composite score for product attitude (α = .94, M = 3.91, SD = 1.30).

Click-through intention

A single item was used to assess click-through intentions (Aguirre et al. Citation2015). Participants provided responses using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree) regarding the statement “I would like to click on the advertisement to get further information” (M = 2.67, SD = 1.42).

Purchase intentions

Purchase intentions were measured using three semantic differential items derived from a five-item scale developed by Spears and Singh (Citation2004). The items were rated on 7-point bipolar scales anchored by I definitely do not intend to buy it/I definitely intend to buy it, I have very low purchase interest/I have very high purchase interest, and I will probably not buy it/I will probably buy it. The mean of the three items was used as the measure of purchase intentions (α = .92, M = 2.82, SD = 1.48).

Control variables

Age, gender, education, Internet usage, online search frequency, product familiarity, and product involvement were measured as potential control variables. Internet usage was measured by asking how many hours the participant spends using the Internet on a typical day (Kim and Huh Citation2017). Online product search frequency was measured by asking the participants how many times they search for products/services online in a typical week (Kim and Huh Citation2017). Product familiarity was measured with one item using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Very unfamiliar) to 7 (Very familiar) regarding the advertised product. Product involvement was measured using three semantic differential items derived from the Personal Involvement Inventory (Zaichkowsky Citation1994), which were averaged to form the measure (α = .94, M = 3.20, SD = 1.40). To improve the power of the study without inflating researcher degrees of freedom, we evaluated whether the potential control variables should be included as covariates in the analyses based on four criteria suggested by Meyvis and van Osselaer (Citation2018): the covariate should have a substantial linear correlation with the dependent variable (r > 0.2); the independent variable should not cause differences in the covariate; the measurement of the covariate should not influence participants’ response to the dependent measures; and the relationship between the covariate and the dependent measures should not differ among conditions. Based on these criteria, age was included as a covariate for the subsequent analyses.

Manipulation checks

To ensure the manipulation was successful, we asked participants if they had noticed the ad in the mockup Web page right after they were exposed to the stimuli as the first part of the manipulation check. In the second part, participants also evaluated the perceived personalization of the ad based on five 7-point Likert scale items (Ham Citation2017; α = .84, M = 3.45, SD = 1.27). In addition, we asked participants how similar they perceived the product they browsed in the shopping scenario and the product they saw in the ad on a 7-point binary scale anchored by Totally different and Totally identical (M = 4.68, SD = 2.14). They were also asked to what extent they thought the ad was based on their fictitious browsing history in the scenario on a 7-point scale anchored by Not at all and Very much (M = 5.34, SD = 1.87).

Results

Manipulation checks

Participants who were exposed to the OBA (n = 133; M = 3.97, SD = 1.11) perceived the ad as significantly more personalized than participants who were exposed to the non-OBA (n = 108; M = 2.80, SD = 1.15), t (239) = −8.01, p < .001. The product in the OBA condition (M = 6.03, SD = 1.40) was considered significantly more similar to the product the respondents picked in the online shopping scenario earlier than the product in the non-OBA (M = 3.03, SD = 1.67), t (209.02) = −14.89, p < .001. Moreover, participants in the OBA condition (M = 6.20, SD = 1.28) were significantly more likely to believe that the ad was created based on their browsing history compared to participants in the non-OBA condition (M = 4.27, SD = 1.94), t (177.71) = −8.91, p < .001. These results proved that the manipulation was successful.

Main effects of OBA

We performed a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to examine the main effect of OBA. The results showed that OBA had a significant effect on ad persuasiveness, F (3, 236) = 17.99, p < .001, Wilks’s lambda = 0.81, ηp2 = .19. Subsequent analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) tests showed that compared to non-OBA, OBA significantly increased product attitude, click-through intention, and purchase intentions, which supported hypothesis 1. shows the statistics for each dependent variable respectively.

Table 2. MANCOVA results of the effect of OBA on the dependent variables.

Moderating effects of privacy concerns and OBA knowledge

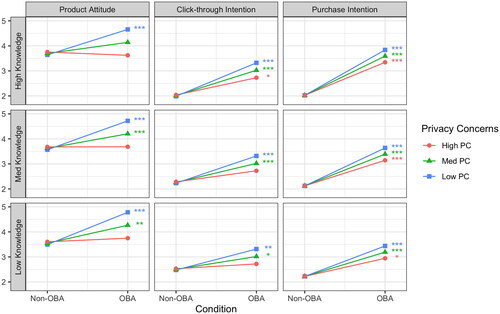

Hypotheses 2 and 3 concerned the moderating roles of privacy concerns and OBA knowledge in the effects of OBA on ad persuasiveness. A double moderation model (Model 2) from the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression-based path analysis tool PROCESS was used to test the hypotheses (Hayes Citation2017). We conducted three separate analyses with product attitude, click-through intention, and purchase intentions as the dependent variables, respectively. shows the detailed statistics of the models.

Table 3. Coefficients of the double moderation model on the dependent variables.

First, we found that OBA had a significant positive effect on product attitude (b = 0.58, p < .001). Privacy concerns negatively moderated the effect of OBA (b = −0.48, p < .001), such that the positive effect of OBA on product attitude is smaller when privacy concerns are higher. This indicated that privacy concerns reduced the positive effect of OBA on product attitude. Thus, hypothesis 2(a) was successfully supported. OBA knowledge did not have a moderating effect on the OBA effect (b = −0.11, p = .393), which did not support hypothesis 3(a). The subsequent conditional effects analysis (see ) revealed that when the individual had low or medium privacy concerns, OBA positively affected product attitude regardless of the individual’s level of OBA knowledge. depicts the conditional effects visually. When the individual had high levels of privacy concerns, there was no significant difference in product attitude between the OBA and non-OBA conditions.

Table 4. Conditional effects of OBA at different levels of the moderators.

As for click-through intention, OBA significantly increased click-through intention compared to non-OBA (b = 0.76, p < .001). However, the interaction effect between OBA and privacy concerns on click-through intention was insignificant (b = −0.27, p = .064), which shows that hypothesis 2(b) was not supported. Furthermore, we found no significant moderation of OBA knowledge (b = 0.20, p = .149), which failed to support hypothesis 3(b).

OBA had a positive main effect on purchase intentions (b = 1.27, p < .001). However, the analyses revealed no moderation effect of privacy concerns on the relationship between OBA and purchase intentions (b = −0.21, p = .153); hypothesis 2(c) was not supported. In addition, OBA knowledge did not moderate the relationship between OBA and purchase intentions (b = 0.24, p = .083), which also failed to support hypothesis 3(c).

Privacy concerns and OBA knowledge by country

To test hypothesis 4 we ran an ANCOVA with country as the independent variable, age as the covariate, and privacy concerns as the dependent variable. The test revealed a significant difference in privacy concerns between Chinese and Dutch participants, F (1, 238) = 28.29, p < .001. Chinese respondents (M = 5.97, SE = 0.10, 95% CI [5.76, 6.17]) displayed significantly higher privacy concerns than Dutch participants (M = 5.11, SE = 0.11, 95% CI [4.89, 5.34]). However, this was the opposite of what we hypothesized in hypothesis 4.

Another one-way ANCOVA test with OBA knowledge as the dependent variable revealed a significant difference in OBA knowledge between Chinese and Dutch participants, F (1, 238) = 11.16, p < .001. Dutch people (M = 3.92, SE = 0.11, 95% CI [3.71, 4.13]) had significantly higher levels of OBA knowledge than Chinese people (M = 3.41, SE = 0.10, 95% CI [3.22, 3.60]), which supported hypothesis 5.

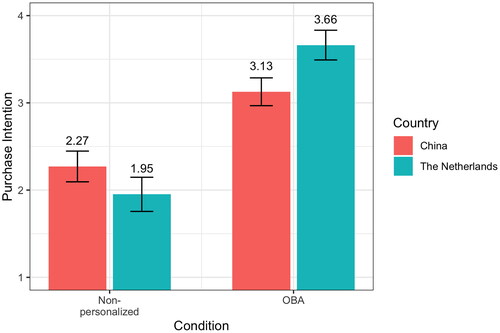

Country and OBA effects

To examine whether and how the effects of OBA on ad persuasiveness differed for Dutch and Chinese people (hypothesis 6), we conducted a two-way ANCOVA test for each dependent variable with ad type and country as independent variables and age as the covariate. There was no interaction effect between OBA and country on product attitude (hypothesis 6(a), F (1, 236) = 2.43, p = .120). Similarly, we did not observe a difference regarding the effect of OBA on click-through intention between Dutch and Chinese participants (hypothesis 6(b), F (1, 236) = 0.23, p = .632). Finally, Dutch and Chinese participants differed on the OBA effect on purchase intentions, F (1, 236) = 6.21, p = .013. As shown in , for Chinese participants, OBA (M = 3.13, SE = 0.16, 95% CI [2.81, 3.44]) led to slightly higher purchase intentions compared to non-OBA (M = 2.27, SE = 0.18, 95% CI [1.92, 2.62]). Whereas for Dutch participants, OBA (M = 3.66, SE = 0.17, 95% CI [3.33, 4.00]) resulted in much higher purchase intentions among Dutch participants in comparison with non-OBA (M = 1.95, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [1.57, 2.34]). Thus, hypothesis 6(c) was supported.

As we theoretically postulated that the OBA effect on ad persuasiveness differs between Dutch and Chinese people through their differences in privacy concerns and OBA knowledge, an indirect moderation model was used to investigate if country indirectly moderates the effect of OBA on ad persuasiveness through privacy concerns and/or OBA knowledge. We customized this model in PROCESS using 10,000 bootstrap samples. The results from the integrated models showed that country did not moderate the effect of OBA on ad persuasiveness directly (for product attitude: b = 0.36, p = .323; for click-through intention: b = −0.21, p = .595; for purchase intentions: b = 0.68, p = .087). Instead, the indirect moderation effect of country via privacy concerns on product attitude was statistically significant, as the bootstrap confidence intervals did not contain zero, indicating that country indirectly moderated the OBA effect on product attitude through privacy concerns (see ). On the other hand, the indirect moderation effects of country through OBA knowledge were not significant for any of the dependent variables.

Table 5. Indirect moderation effects.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was twofold: (1) to investigate the extent to which privacy concerns (as a trait) and OBA knowledge create boundary conditions for OBA persuasiveness and (2) to explore whether their roles in OBA effects differ for Dutch and Chinese people. In short, OBA is less persuasive for people with high privacy concerns but is more effective than non-OBA regardless of the individual’s level of OBA knowledge. It is also more effective for Dutch consumers than Chinese consumers, which could be due to the finding that Chinese consumers have higher privacy concerns than Dutch consumers.

First, we found that for consumers with low privacy concerns, OBA results in significantly more positive product attitude than non-OBA, while for consumers with high privacy concerns, there is no significant difference between the two conditions. This finding consolidates previous research that privacy concerns play a negative role in the context of OBA, while we furthermore showed that even the generic trait of being concerned about one’s privacy can influence the receptivity of OBA. In addition, our finding shows that privacy concerns weaken but do not reverse the positive effect of OBA. This suggests that the benefit of personal relevance could outweigh the cost of giving away privacy in the privacy calculus (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977), indicating the power of OBA.

Second, we found that OBA knowledge does not have an influence on the effectiveness of OBA. This suggests that more knowledge about OBA does not necessarily lead to more resistance toward OBA. This could be explained by the postulation of Friestad and Wright (Citation1994) that consumers’ own goals guide their responses toward persuasion attempts and it should not be assumed that people invariably resist persuasion even if they have sufficient knowledge of persuasion tactics. In the current study, consumers probably have established a goal of looking for an ideal pair of pants from the online shopping scenario, so that when they were exposed to the OBA they might perceive the ad aligning with their goals and respond to the ad accordingly, despite knowing the mechanisms of the ad. Another possible explanation for this finding is that the responses toward OBA are influenced more by affection than cognition. Strycharz (Citation2018) discovered that knowledge has only a small indirect relationship with attitude toward personalized marketing communication, while affective factors such as privacy concerns and the feeling of resignation play a more crucial role in influencing consumer responses. The current study confirms this by demonstrating that privacy concerns are a more influential factor in OBA effectiveness than people’s knowledge about OBA.

In terms of the country differences in the persuasiveness of OBA, we found that OBA (versus non-OBA) has a stronger positive effect on purchase intentions for Dutch people than for Chinese people. Further investigation revealed that country interacts only indirectly with OBA through privacy concerns but not OBA knowledge. From this result, we can infer that it is privacy concerns rather than country as a whole or OBA knowledge that drives the differences in OBA effects. This again illustrates the important role of privacy concerns in influencing OBA persuasiveness, even in a cross-country context. The reason that Dutch people respond to OBA more positively than Chinese people is thus due to the finding that Dutch participants depicted lower privacy concerns than Chinese participants.

Interestingly, the difference in privacy concerns between Chinese and Dutch people is contrary to what we expected. One potential explanation could be that the EU had stricter laws protecting online privacy at the time of our data collection, with the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive governing the collection and handling of online personal data (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. Citation2017). In China, the Cybersecurity Law took effect in 2017, which officially forbade the collection and sale of users’ online personal information without their consent. However, the law does not clearly specify the practices with which companies need to comply (Sheng Citation2019). The stricter laws in the European Union might offer Dutch people a sense of reassurance that their privacy is well protected. Research has found that the GDPR reduces the privacy concerns of Internet of Things users (Paul, Scheibe, and Nilakanta Citation2020). Moreover, the GDPR requires organizations to provide people with a privacy notice and has laid out detailed guidelines for that. Previous research showed that having privacy policies can increase trust and decrease privacy concerns (Wu et al. Citation2012), which could in turn reduce Dutch people’s privacy concerns. Another possible explanation is that Chinese citizens may have been more frequently exposed to cases of data misuse and data breach, resulting in higher privacy concerns. To name a few, in 2020, Weibo, one of the biggest social media platforms in China, was hacked, and the data of 538 million users were available for sale on the dark Web (Cimpanu Citation2020). A more recent large-scale data breach happened in 2022, which recorded data leakage of almost one billion Chinese citizens (Xiong, Ritchie, and Gan Citation2022). The same year, Didi—a large ride-hailing platform—was fined $1.2 billion for illegally collecting a massive amount of passenger data. The frequent occurrences of such cases could be a reason that Chinese consumers perceive higher risks of privacy being threatened, thus heightening their privacy concerns. Based on this finding, a suggestion for future research is to disentangle what makes people in different countries and societies differ in privacy concerns. Aside from culture, other issues such as privacy-related regulations, policies, and current practices might also influence privacy concerns on a societal level.

Theoretical and practical implications

This study contributes to the body of OBA research in several aspects. First, it furthers our understanding of the boundary conditions of OBA outcomes. Previous studies have well demonstrated the negative impact of privacy concerns in personalized advertising (Aiolfi, Bellini, and Pellegrini Citation2021; Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Kim and Huh Citation2017; Morimoto Citation2021). However, few have discussed to what exact extent privacy concerns can damage ad effectiveness. Our finding reveals that people’s generic privacy concerns can diminish but not necessarily reverse the positive effects of OBA. Applying the privacy calculus, this indicates that even for individuals with high privacy concerns, the perceived cost does not outweigh the perceived benefit of OBA. Second, we investigated privacy concerns as a trait rather than a state to account for the influence of consumer characteristics on OBA effects. Previous studies showed that level of personalization (Kim et al. Citation2022) or ad relevance (Jung Citation2017) can influence privacy concerns temporarily, which is highly contingent on the execution of the advertisement. Our findings suggest that individuals who are dispositionally concerned about their privacy might be consistently more resistant to OBA across different contexts. Methodologically, state privacy concerns are commonly investigated as an independent variable (e.g., Aiolfi, Bellini, and Pellegrini Citation2021) or a mediator (e.g., Kim et al. Citation2022; Morimoto Citation2021; Ryu and Park Citation2020), while trait privacy concerns are investigated as a moderator. Therefore, this study adds to the limited research that tested the moderating role of privacy concerns as a trait. Third, the study responds to the call for research in OBA knowledge from Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius (Citation2017) by examining the role of OBA knowledge in OBA effects. Our finding that OBA knowledge does not harm the effectiveness of OBA highlights the proposition in PKM that if the goal of the consumer aligns with the persuasion attempt, knowledge about the persuasion does not necessarily lead to resistance. Furthermore, by comparing the effects of privacy concerns and OBA knowledge in the same study, our study underscores the more prominent role of privacy concerns compared to OBA knowledge in OBA research.

More importantly, the current study is one of the few comparative studies in the field of OBA research that examined country differences. It not only provides novel insights regarding country differences in privacy concerns and OBA knowledge but also explains country differences in OBA effects using these two factors. Contradictory to previous findings, which suggested that high collectivism is related to lower privacy concerns (Chen and Tsoi Citation2011; Milberg et al. Citation1995, Milberg, Smith, and Burke Citation2000; Wang, Xia, and Huang Citation2016), our findings showed that Chinese people, although highly collectivistic, have higher privacy concerns than Dutch people, who are highly individualistic. This finding suggests that privacy concerns are not solely determined by cultural differences, while other factors, such as regulations and current data practices, should be taken into consideration as well.

From a practical perspective, OBA remains an attractive marketing tool, as our research showed that it is still more powerful than non-OBA. On the other hand, privacy concerns do weaken the persuasiveness of OBA. Ad practitioners should be aware that OBA may not work equally well for everyone, as we found that it has almost no effect on consumers with high levels of privacy concerns. The study also reveals that Chinese consumers have higher privacy concerns than Dutch consumers, which implies that OBA might be more effective in the Netherlands than in China. This is especially insightful for multinational advertisers who plan to implement OBA in multiple countries or foreign advertisers who are entering the Dutch or Chinese markets. Overall, in markets where consumers tend to be more concerned about their privacy, OBA might not produce the same positive outcomes. Companies may also need to be more transparent about their data collection and use to build consumer trust. Moreover, our results showed that Chinese people still have relatively less knowledge about OBA; therefore, it is important to educate Chinese consumers about the regulations and persuasion tactics of OBA so that they can be aware of the use of personal data in OBA and evaluate the persuasion messages with discretion.

Limitations and future research

The current study compared only two countries for the OBA effects in different societies. Although China and the Netherlands are deemed typical collectivistic and individualistic countries with distinct cultures, future research could validate and extend the current research by comparing the OBA effects among more countries to gain more comprehensive insights. Another benefit of including more countries is that multilevel modeling can then be used, which is more suitable for exploring the nested structure of the data (Field, Miles, and Field Citation2012).

Furthermore, participant recruitment has always been a challenge for cross-culture studies (Clark Citation2012). The recruitment process in this study was different within and between the participants from the two countries, which caused sample differences between countries. Future research should try to standardize the recruitment procedure as much as possible. Larger-scale surveys with a representative sample in each country are needed to compare the levels of privacy concerns and OBA knowledge more reliably across people of different nationalities.

In addition, it is important to reiterate that this study focused on objective OBA knowledge. While the role of objective knowledge was found nonsignificant, subjective knowledge might still play an important role in explaining the effects. Previous research has found that although objective persuasion knowledge establishes the basis for subjective persuasion knowledge (Ryu and Park Citation2020), it is the latter that plays a more direct role in developing coping strategies and third-person perceptions (i.e., the perception that others are more susceptible to ad persuasion than self; Ham and Nelson Citation2016). Future research could include subjective persuasion knowledge in the model and examine its moderating role in cross-country comparisons of OBA effects.

Last but not least, the current study focused on exploring boundary conditions and cross-country comparisons of OBA effects (i.e., moderating effects). We did not attempt to examine the mediators that could explain the process. Future research could include mediators, such as perceived relevance, to further unravel the mechanisms of OBA effects.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.2 KB)References

- Aguirre, E., D. Mahr, D. Grewal, K. de Ruyter, and M. Wetzels. 2015. “Unraveling the Personalization Paradox: The Effect of Information Collection and Trust-Building Strategies on Online Advertisement Effectiveness.” Journal of Retailing 91 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2014.09.005.

- Aiolfi, S., S. Bellini, and D. Pellegrini. 2021. “Data-Driven Digital Advertising: Benefits and Risks of Online Behavioral Advertising.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 49 (7): 1089–1110. doi:10.1108/IJRDM-10-2020-0410.

- Amazeen, M. A., and B. W. Wojdynski. 2019. “Reducing Native Advertising Deception: Revisiting the Antecedents and Consequences of Persuasion Knowledge in Digital News Contexts.” Mass Communication and Society 22 (2): 222–247. doi:10.1080/15205436.2018.1530792.

- Baek, T. H., and M. Morimoto. 2012. “Stay Away from Me: Examining the Determinants of Consumer Avoidance of Personalized.” Journal of Advertising 41 (1): 59–76. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367410105.

- Bleier, A., and M. Eisenbeiss. 2015. “Personalized Online Advertising Effectiveness: The Interplay of What, When, and Where.” Marketing Science 34 (5): 669–688. doi:10.1287/mksc.2015.0930.

- Boerman, S. C., S. Kruikemeier, and F. J. Zuiderveen Borgesius. 2017. “Online Behavioral Advertising: A Literature Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Advertising 46 (3): 363–376. doi:10.1080/00913367.2017.1339368.

- Boerman, S. C., and C. M. Segijn. 2022. “Awareness and Perceived Appropriateness of Synced Advertising in Dutch Adults.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 22 (2): 187–194. doi:10.1080/15252019.2022.2046216.

- Bol, N., T. Dienlin, S. Kruikemeier, M. Sax, S. C. Boerman, J. Strycharz, N. Helberger, and C. H. de Vreese. 2018. “Understanding the Effects of Personalization as a Privacy Calculus: Analyzing Self-Disclosure across Health, News, and Commerce Contexts.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 23 (6): 370–388. doi:10.1093/jcmc/zmy020.

- Brehm, J. W. 1966. A Theory of Psychological Reactance. New York: Academic Press.

- Brehm, S. S., and J. W. Brehm. 1981. Psychological Reactance: A Theory of Freedom and Control. New York: Academic Press.

- Carlson, J. P., L. H. Vincent, D. M. Hardesty, and W. O. Bearden. 2009. “Objective and Subjective Knowledge Relationships: A Quantitative Analysis of Consumer Research Findings.” Journal of Consumer Research 35 (5): 864–876. doi:10.1086/593688.

- Chen, L., and H. K. Tsoi. 2011. “Privacy Concern and Trust in Using Social Network Sites: A Comparison between French and Chinese Users.” In Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2011. Vol. 6948, edited by P. Campos, N. Graham, J. Jorge, N. Nunes, P. Palanque, and M. Winckler, 234–241. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-23765-2_16.

- Cho, H., M. Rivera-Sánchez, and S. S. Lim. 2009. “A Multinational Study on Online Privacy: Global Concerns and Local Responses.” New Media & Society 11 (3): 395–416. doi:10.1177/1461444808101618.

- Cimpanu, C. 2020. “Hacker Selling Data of 538 Million Weibo Users.” ZDNET, March 22. https://www.zdnet.com/article/hacker-selling-data-of-538-million-weibo-users/

- Clark, M. J. 2012. “Cross-Cultural Research: Challenge and Competence.” International Journal of Nursing Practice 18 (s2): 28–37. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02026.x.

- de Groot, J. I. M. 2022. “The Personalization Paradox in Facebook Advertising: The Mediating Effect of Relevance on the Personalization–Brand Attitude Relationship and the Moderating Effect of Intrusiveness.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 22 (1): 57–74. doi:10.1080/15252019.2022.2032492.

- De Keyzer, F., N. Dens, and P. De Pelsmacker. 2022. “How and When Personalized Advertising Leads to Brand Attitude, Click, and WOM Intention.” Journal of Advertising 51 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1080/00913367.2021.1888339.

- Digital Advertising Alliance. n.d. YourAdChoices.com. https://youradchoices.com/

- European Commission. 2019. Special Eurobarometer 487a: The General Data Protection Regulation. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=69701

- Field, A., J. Miles, and Z. Field. 2012. Discovering Statistics Using R. London: SAGE.

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. “The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1086/209380.

- Gao, S., and Z. Zang. 2016. “An Empirical Examination of Users’ Adoption of Mobile Advertising in China.” Information Development 32 (2): 203–215. doi:10.1177/0266666914550113.

- Ham, C.-D. 2017. “Exploring How Consumers Cope with Online Behavioral Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 36 (4): 632–658. doi:10.1080/02650487.2016.1239878.

- Ham, C.-D., and M. R. Nelson. 2016. “The Role of Persuasion Knowledge, Assessment of Benefit and Harm, and Third-Person Perception in Coping with Online Behavioral Advertising.” Computers in Human Behavior 62: 689–702. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.076.

- Hayes, A. F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, Second Edition: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hofstede, G. 1980. “Culture and Organizations.” International Studies of Management & Organization 10 (4): 15–41. doi:10.1080/00208825.1980.11656300.

- Hofstede, G., G. J. Hofstede, and M. Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hwang, K., and Q. Zhang. 2018. “Influence of Parasocial Relationship between Digital Celebrities and Their Followers on Followers’ Purchase and Electronic Word-of-Mouth Intentions, and Persuasion Knowledge.” Computers in Human Behavior 87: 155–173. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.029.

- Jung, A.-R. 2017. “The Influence of Perceived Ad Relevance on Social Media Advertising: An Empirical Examination of a Mediating Role of Privacy Concern.” Computers in Human Behavior 70: 303–309. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.008.

- Kim, H., and J. Huh. 2017. “Perceived Relevance and Privacy Concern regarding Online Behavioral Advertising (OBA) and Their Role in Consumer Responses.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 38 (1): 92–105. doi:10.1080/10641734.2016.1233157.

- Kim, J. J., T. Kim, B. W. Wojdynski, and H. Jun. 2022. “Getting a Little Too Personal? Positive and Negative Effects of Personalized Advertising on Online Multitaskers.” Telematics and Informatics 71: 101831. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2022.101831.

- Kokolakis, S. 2017. “Privacy Attitudes and Privacy Behaviour: A Review of Current Research on the Privacy Paradox Phenomenon.” Computers & Security 64: 122–134. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2015.07.002.

- Kozyreva, A., P. Lorenz-Spreen, R. Hertwig, S. Lewandowsky, and S. M. Herzog. 2021. “Public Attitudes towards Algorithmic Personalization and Use of Personal Data Online: Evidence from Germany, Great Britain, and the United States.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8 (1): 1. doi:10.1057/s41599-021-00787-w.

- Kramer, T., S. Spolter-Weisfeld, and M. Thakkar. 2007. “The Effect of Cultural Orientation on Consumer Responses to Personalization.” Marketing Science 26 (2): 246–258. doi:10.1287/mksc.1060.0223.

- Lambrecht, A., and C. Tucker. 2013. “When Does Retargeting Work? Information Specificity in Online Advertising.” Journal of Marketing Research 50 (5): 561–576. doi:10.1509/jmr.11.0503.

- Laufer, R. S., and M. Wolfe. 1977. “Privacy as a Concept and a Social Issue: A Multidimensional Developmental Theory.” Journal of Social Issues 33 (3): 22–42. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1977.tb01880.x.

- Lee, J., D.-H. Park, and I. Han. 2008. “The Effect of Negative Online Consumer Reviews on Product Attitude: An Information Processing View.” Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 7 (3): 341–352. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2007.05.004.

- Li, Y., E. H. R. Rho, and A. Kobsa. 2022. “Cultural Differences in the Effects of Contextual Factors and Privacy Concerns on Users’ Privacy Decision on Social Networking Sites.” Behaviour & Information Technology 41 (3): 655–677. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2020.1831608.

- Limpf, N., and H. A. M. Voorveld. 2015. “Mobile Location-Based Advertising: How Information Privacy Concerns Influence Consumers’ Attitude and Acceptance.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 15 (2): 111–123. doi:10.1080/15252019.2015.1064795.

- Maslowska, E., E. G. Smit, and B. van den Putte. 2013. “Assessing the Cross-Cultural Applicability of Tailored Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 32 (4): 487–511. doi:10.2501/IJA-32-4-487-511.

- Matz, S. C., M. Kosinski, G. Nave, and D. J. Stillwell. 2017. “Psychological Targeting as an Effective Approach to Digital Mass Persuasion.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114 (48): 12714–12719. doi:10.1073/pnas.1710966114.

- Meyvis, T., and S. M. J. van Osselaer. 2018. “Increasing the Power of Your Study by Increasing the Effect Size.” Journal of Consumer Research 44 (5): 1157–1173. doi:10.1093/jcr/ucx110.

- Milberg, S. J., S. J. Burke, H. J. Smith, and E. A. Kallman. 1995. “Values, Personal Information Privacy, and Regulatory Approaches.” Communications of the ACM 38 (12): 65–74. doi:10.1145/219663.219683.

- Milberg, S. J., H. J. Smith, and S. J. Burke. 2000. “Information Privacy: Corporate Management and National Regulation.” Organization Science 11 (1): 35–57. doi:10.1287/orsc.11.1.35.12567.

- Morimoto, M. 2021. “Privacy Concerns about Personalized Advertising across Multiple Social Media Platforms in Japan: The Relationship with Information Control and Persuasion Knowledge.” International Journal of Advertising 40 (3): 431–451. doi:10.1080/02650487.2020.1796322.

- Paul, C., K. Scheibe, and S. Nilakanta. 2020. “Privacy Concerns regarding Wearable IoT Devices: How It is Influenced by GDPR?” In Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. doi:10.24251/HICSS.2020.536.

- Rogers, T. B., N. A. Kuiper, and W. S. Kirker. 1977. “Self-Reference and the Encoding of Personal Information.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 35 (9): 677–688. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.35.9.677.

- Ryu, S., and Y. Park. 2020. “How Consumers Cope with Location-Based Advertising (LBA) and Personal Information Disclosure: The Mediating Role of Persuasion Knowledge, Perceived Benefits and Harms, and Attitudes toward LBA.” Computers in Human Behavior 112: 106450. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106450.

- Segijn, C. M., and I. van Ooijen. 2022. “Differences in Consumer Knowledge and Perceptions of Personalized Advertising: Comparing Online Behavioural Advertising and Synced Advertising.” Journal of Marketing Communications 28 (2): 207–226. doi:10.1080/13527266.2020.1857297.

- Segijn, C. M., H. A. M. Voorveld, and K. A. Vakeel. 2021. “The Role of Ad Sequence and Privacy Concerns in Personalized Advertising: An Eye-Tracking Study into Synced Advertising Effects.” Journal of Advertising 50 (3): 320–329. doi:10.1080/00913367.2020.1870586.

- Sheng, W. 2019. “One Year after GDPR, China Strengthens Personal Data Regulations, Welcoming Dedicated Law.” TechNode, June 19. http://technode.com/2019/06/19/china-data-protections-law/

- Smith, H. J. 2001. “Information Privacy and Marketing: What the U.S. should (and Shouldn’t) Learn from Europe.” California Management Review 43 (2): 8–33. doi:10.2307/41166073.

- Spears, N., and S. N. Singh. 2004. “Measuring Attitude toward the Brand and Purchase Intentions.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 26 (2): 53–66. doi:10.1080/10641734.2004.10505164.

- Stanton, J. M., and K. R. Stam. 2002. “Information Technology, Privacy, and Power within Organizations: A View from Boundary Theory and Social Exchange Perspectives.” Surveillance & Society 1 (2): 152–190. doi:10.24908/ss.v1i2.3351.

- Strycharz, J., G. van Noort, E. Smit, and N. Helberger. 2019. “Consumer View on Personalized Advertising: Overview of Self-Reported Benefits and Concerns.” In Advances in Advertising Research X, edited by E. Bigne and S. Rosengre, 53–66. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-24878-9_5.

- Strycharz, J. 2018. “‘Do I Have a Reason to Worry?’: Knowledge-Based Affective Elements of Attitude towards Personalized Marketing Communication.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the American Academy of Advertising. Lubbock, TX: American Academy of Advertising. https://search.proquest.com/openview/c38058f822f32a9ca2322dfe2ff05733/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=40231.

- Sutanto, J., E. Palme, C.-H. Tan, and C. W. Phang. 2013. “Addressing the Personalization-Privacy Paradox: An Empirical Assessment from a Field Experiment on Smartphone Users.” MIS Quarterly 37 (4): 1141–1164. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.4.07.

- Thaler, R. 1985. “Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice.” Marketing Science 4 (3): 199–214. doi:10.1287/mksc.4.3.199.

- Triandis, H. C. 2001. “Individualism-Collectivism and Personality.” Journal of Personality 69 (6): 907–924. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.696169.

- van Doorn, J., and J. C. Hoekstra. 2013. “Customization of Online Advertising: The Role of Intrusiveness.” Marketing Letters 24 (4): 339–351. doi:10.1007/s11002-012-9222-1.

- Varnali, K. 2021. “Online Behavioral Advertising: An Integrative Review.” Journal of Marketing Communications 27 (1): 93–114. doi:10.1080/13527266.2019.1630664.

- Wang, Y., H. Xia, and Y. Huang. 2016. “Examining American and Chinese Internet Users’ Contextual Privacy Preferences of Behavioral Advertising.” In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 539–552. doi:10.1145/2818048.2819941.

- We Are Social. 2022. “Digital 2022: Another Year of Bumper Growth.” We Are Social, January 26. https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2022/01/digital-2022-another-year-of-bumper-growth-2/

- Wu, K.-W., S. Y. Huang, D. C. Yen, and I. Popova. 2012. “The Effect of Online Privacy Policy on Consumer Privacy Concern and Trust.” Computers in Human Behavior 28 (3): 889–897. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.008.

- Xiong, Y., H. Ritchie, and N. Gan. 2022. “Nearly One Billion People in China Had Their Personal Data Leaked, and It’s Been Online for More Than a Year.” CNN, July 5. https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/05/china/china-billion-people-data-leak-intl-hnk/index.html

- Xu, D. J. 2006. “The Influence of Personalization in Affecting Consumer Attitudes toward Mobile Advertising in China.” Journal of Computer Information Systems 47 (2): 9–19. doi:10.1080/08874417.2007.11645949.

- Yang, K. C. C., and Y. Kang. 2015. “Exploring Big Data and Privacy in Strategic Communication Campaigns: A Cross-Cultural Study of Mobile Social Media Users’ Daily Experiences.” International Journal of Strategic Communication 9 (2): 87–101. doi:10.1080/1553118X.2015.1008635.

- Zaichkowsky, J. L. 1994. “The Personal Involvement Inventory: Reduction, Revision, and Application to Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 23 (4): 59–70. doi:10.1080/00913367.1943.10673459.

- Zarouali, B., K. Ponnet, M. Walrave, and K. Poels. 2017. “Do You like Cookies?” Adolescents’ Skeptical Processing of Retargeted Facebook-Ads and the Moderating Role of Privacy Concern and a Textual Debriefing.” Computers in Human Behavior 69: 157–165. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.050.

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. 2015. Improving Privacy Protection in the Area of Behavioural Targeting. Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands: Kluwer Law International.

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J., S. Kruikemeier, S. C. Boerman, and N. Helberger. 2017. “Tracking Walls, Take-It-or-Leave-It Choices, the GDPR, and the ePrivacy Regulation.” European Data Protection Law Review 3 (3): 353–368. doi:10.21552/edpl/2017/3/9.