In this autotheoretical editorial, we (the journal co-editors) operate in the Black radical tradition of disruption by employing kitchen-table dialogue as an improvisational exegetical method to introduce the contributors and articles featured in our inaugural special issue. We use our experiences with invisibility, erasure, misnaming, and miseducation in our schooling, primarily in the context of the United States, as the basis for naming and elucidating our editorial vision. We explain what we are calling for, who we are, and what we have learned at the feet of the contributors to this special issue in a conversation that reveals both diversity in our lived experience and connectivity in our diasporic Blackness. This connectivity underpins our desire for Equity & Excellence in Education to be a space “for the culture”—that is, a place where scholarship celebrates the intersectional, multidimensional knowledges of Black, Indigenous, People of Color and communities most often dehumanized and (mis)read under the white/Western gaze as the fetishized, the marginalized or the other than human.

Commanding the full use of the tongue

*Track playing in the background: Erykah Badu, “On and On”*

Welcome to the kitchen table, y’all!

Yasss, dearly beloved; we are gathered here today to get through this thing called life … nah, but for real for real … let’s go!

I got so much life out of reading all of the manuscripts for our inaugural issue. I feel like this is such a dope way to just unpack what we’ve been learning and visioning. Jamila, you wanna start off by saying a bit about why you brought us together and why at the kitchen table, in particular?

I’m lovin’ the energy! Well, I’ll say, first, that it is no accident that we’ve convened at the kitchen table. In the words of Dillard, “The kitchen table has been an enduring image in collective Black feminisms throughout the ages” (Dillard, this issue). At the feet of her wisdom, we’ve learned that “we exist because of the long past millions of Black women around our kitchen tables” (Dillard, this issue). So, as we work through our collective vision for our new editorship, I felt like this kitchen-table dialogue would just be a fire way to tap into that ethos. And we have with us the invited manuscripts of our elders and peers for our inaugural issue to learn from and with them about what the future of equity and excellence in education must be in our world.

That feels a little broad to me. What do you mean by “what the future of equity and excellence must be?”

Right, Esther. As I sit here with my newborn baby boy, Ellison Hope, it feels important to pause and name what we mean: how are we defining equity?; and what do we mean by excellence? … for him, for his sister, Lela Joy, and all of us and our futures. Our tongues have historically been slapped into silence (Tohe, Citation1999), and using this space to name what we mean feels so urgent to me right now.

I mean, these days, so many people are just throwing around the word “equity,” and we know the word “excellence” is racialized, classed, ableist, and gendered in so many ways. So from our previous conversations as co-editors, one of the core questions is, what must equity and excellence in education look like, what does it require, how is it felt, heard, and enacted when we break free from the logic of institutions that we still operate within, and while designing new futures that speak to, with, and for the culture towards transformative change? Where better to begin grappling with that question than right here at the kitchen table of the journal?

Hmmm. I feel that! Here at this kitchen table and in this inaugural issue and over the next three years with this journal, we (the collective we) can continue to answer such questions drawing inspiration and other possibilities from our Black radical traditions, Afrofuturistic and feminist imaginations, and our “Black pentecostal breath” (Crawley, Citation2016).

Yesss, sis! I’m even thinking about Jada Pinkett Smith’s now-famous “Red Table Talk,” which occurs at a single red table led by the intimacy of three generations of Black women (i.e., Jada, her mother, and her daughter). The knowing at the kitchen table is kindred. It is full of laughter and refuge. Healing and pain. Nourishment for the body and the mind. It is the place where Civil Rights activists gathered in homes to conjure up plans for resistance. Hair is braided at the kitchen table. Gossip spread. Memories and folktales and generations of wisdom in the oral traditions of the African Diaspora, all at the kitchen table. Justin, I know you asked why I brought this particular collection of people together for this journey. Now y’all know I’m a poet, so I gotta get all poetic sometimes, LOL. I want to begin answering that question with the poetry of Warsan Shire. Y’all know her work?

That’s the woman who wrote the poetry for Beyonce’s Lemonade album, right?

Yes! She wrote for Queen Bey! Listen to these words:

Give your daughters difficult names. Give your daughters names that command the full use of tongue. My name makes you want to tell me the truth. My name doesn’t allow me to trust anyone that cannot pronounce it right. (Shire, Citation2016)

Shire’s poem speaks back to a reality that has too long demanded our erasure. The erasure of the bodies, knowledges, and nuanced complexities of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) for systems that want our bodies’ labor, but not our spirits or our minds. It has been too difficult to pronounce our names. It has been too difficult to pronounce our value. It has been too difficult to pronounce our knowledges, histories, and ways-of-being accurately and emphatically. Hence, it has been too difficult for BIPOC to trust the institutions and structures that refuse to call us by our names. I brought us to this collective editorship because, as your peer, colleague, and friend, I admire the myriad ways that each of you “command the full use of the tongue” when it comes to the kinds of equity and justice you are fighting for in your scholarship. And when we think about the role of academic journals in gatekeeping along the contours of whose knowledges are valued in the academy, I am so moved by the possibilities we might actualize if we dedicate the tenure of our editorship to doin’ it for the culture!

Jamila, it’s both a heavy responsibility and an incredible honor to serve in the capacity of editor alongside Justin, Keisha, and you. I love that each of us enters this space deeply, boldly, and fearlessly attuned to Blacknesses because of our varied intersectional positionalities, histories, and geographies. I hope that throughout our editorship, we feel emboldened enough to remember the wisdom in these lessons that we’ve learned to forget (Dillard, Citation2012).

I totally agree, Esther. And I think Shire’s (Citation2016) poem invites that boldness and fearlessness. So, for the title of our inaugural editorial, I’m thinking, “Call us by our names!”

What about “Call us by our names: A kitchen-table dialogue on doin’ it for the culture”?

Yesssssss!!!

Fam, I gotta confess that that title got me thinkin’ about Erykah Badu’s track On and On … the versus keep runnin’ around in my head: “If we were made in His image then call us by our names. Most intellects do not believe in God, but they fear us just the same” (Badu & Jamal, Citation1996). I think about the storied legend of my great maternal grandmother, Alice Pringle, a teacher in the rural parts of Charleston, South Carolina. She taught Black folks how to read and write on the heels of anti-literacy laws that prohibited people like us from accessing “formal education.” I imagine the courage and danger present in this act. Passed down through generations, we say her name and tell the story of her doin’ it for the culture … putting her life on the line for the culture. And that is what we have always done, right?

I love me some Erykah, and that is absolutely what we have always done! Like so many, Alice’s life was only valued to the degree that it did not transgress. Evoking her name and her story makes visible what others have tried to circumscribe or erase: her rights and full humanity.

Yes! I see commanding the full use of the tongue as a rallying cry for the fullness of one’s humanity to be seen. Y’all, I have been musing on visibility a lot lately, in particular the politics of seeing. My reflections on seeing are much more than whether someone’s eyes can register my presence. As a Black man in this world, I know I am visible regardless of whether someone chooses to acknowledge me. Here, I am referring to seeing as a sort of intangible orientation to the ways we place value on the life/lives of individuals, communities, and cultures (Coles, Citation2021). To command the full use of the tongue, then, means to rupture gazes structured in and clouded by inequity that dismisses our humanity.

Yasss preach, J!

I am not waiting for your statistical analysis to value me or your ethnographic observations to see my humanity through thick description. I demand that you value me now. As I think about the future of equity, my existence, and the mattering of my existence—along with the existence of historically marginalized and vulnerablized populations throughout the world—I invite you to be transformed by my being, a being often falsely constructed as needing to be transformed by dominant power structures. Here, whiteness, for instance.

Whew! “I invite you to be transformed by my being.” Wow. That needs to be the title of an upcoming editorial. Justin, Imma let you finish, lol, but I want to chime in on this “future of equity” piece real quick. I love your assertion that we know that we are visible whether someone chooses to acknowledge it or not. These days, where Black Lives Matter is painted across streets in every city, and public statements about equity and justice are becoming more and more mainstream, too many seem to be conflating empathy with equity. Empathy is not equity. Others finally seeing, understanding, and rendering our pain and existence visible is not equity. The idea that a mere acknowledgment of BIPOC realities is some form of justice is just a reification of white privilege where only what is legitimated as real through the white gaze is valid. In the new aims and scopes for the journal, we clarified that we are not here for flat theorizations of equity and justice. White empathy is not equity. Equity is abolishing social stratification and systemic oppression. Equity is land repatriation and divestment from carcerality, whiteness, coloniality, ableism, and gender oppression. Equity is transforming the material conditions of marginalized groups. Equity is making real room for the fullness of who we are instead of erasure politics that marks what integration has been in America since the 1950s.

This politics of erasure is what I’m getting at. The catalyst responsible for my thinking on the politics of seeing and commanding the full use of the tongue has been the late Mamie Till-Mobley, the mother of Emmett Till. So, Emmet was murdered, and he never received justice (Coles, Citation2018). For justice, here, the criminal justice system (e.g., courts, police, and prisons) did not value Emmett’s Black life. Mamie called for Emmett’s funeral to be an open casket to fight such entrenched inequity rooted in invisibilizing and devaluing Black life.

Yes! So the world could see what they did to her child!

In the murderers’ commitment to not seeing Emmett’s humanity, they made his face unrecognizable. Emmett’s “body was swollen beyond recognition. His teeth were missing. His ear was severed. His eye was hanging out. The only thing that identified him was a ring” (Brown, Citation2018). The goal was not simply to kill Emmett, but to erase him.

Wow, Justin! Wow. I’m thinking about Breonna Taylor’s police report, which was basically four blank pages, and listed her injuries as “none” after the police murdered her. None. Erasure.

So, Mamie commanding the world to see her son’s mangled body was a rupturing to the ways society makes oppressed people feel as if oppressive conditions are just figments of their imagination. Mamie made the difficult decision to share her son’s body with the world so that it might make the world tell the truth. Learning from Emmett, Breonna, and countless (un)identifiable and (un)seen others, I urge everyone to understand that the future of equity must be that you see me before I am dead.

Ohhh my my my lawd! See me before I’m dead.

And in that seeing, you transform the conditions that make my life so disposable in the first place.

To go back to the question that the four of us are thinking through here, what does seeing me and others before they and I are dead look like and require? How is such equity, guided by the politics of seeing I carve out here, felt, heard, and enacted? Well, it looks like commanding that equity, right now (Dumas, Citation2013, Citation2016). There are no calls for permission or timid requests for access. Instead, to reach the equity that we imagine will ensure marginalized folks’ futurity, we must take a lesson from Mamie and so many other Black women and demand that our value be made visible. For me, equity in education must be about leaning into the lifeworlds and knowledges of marginalized populations in ways that allow us to truly see them/us in all their/our brilliance and dynamicity. In commanding a full use of the tongue, equity is about being fugitive to dominant and violent ways of knowing and being that are passed off as universal truths.

Whew chile! There is so much to unpack. I’m loving this! What does this kind of knowledge mean for the vision that we are forwarding in the future of this journal? But, before we get into that, are we gonna discuss our fear of coming across as “too Black” in our inaugural issue, or is the plan to keep that to ourselves? *sips tea*

Black, but not too Black

*Track change: Shaybo, “Daily Duppy”*

That really strikes me, Jamila—that question of if we gon’ discuss our fear of coming across as “too Black.” I want to spend some time mulling that over, feeling its heaviness on my tongue. What it means to step into this role afraid, and what happens if we allow that fear to tie our tongues, leaving us tongue-tied? I wonder, can we be courageous enough to name exactly who and what we fear? If we were to unstick from our fear and unfurl our tongues, then what would we feel free/d to say? What knowledge would roll off our uninhibited tongues? How might that knowledge propel those of us concerned with freedom from oppression into flight, destined for a future pluriverse expansive enough for myriads of humans to coexist in and cohabit peacefully?

The fact that even embers of this idea of being too Black could infiltrate our dialogue reminds me that the total sociopolitical climate is anti-Black (Sharpe, Citation2016). Can Black people not speak about equity in ways that have implications for ourselves and all people? The world imagines Blackness as a social positioning that cannot teach lessons on equity. It’s like, my dark Black skin, my natural-born and reared Black cultural self (as an embodiment of Blackness) cannot even be of value to itself, to me? Here, I reserve space to refuse that falsehood. Despite being educated early about the inequity that affects Black people and others, it took me a while to realize that the power that lay within me to counter inequity was that very essence that caused Black people to suffer –—(disdain of) my Blackness.

Justin, you’re making me pause for a moment and reflect on why and how Black critical education scholars tend to mute the vibrance of our colorful ways of being. I am thinking about the dialogues that remain among us, the knowledge that circulates only in the Black spaces in which we gather to seek refuge and respite from the violence of anti-Blackness we endure in Ivory Tower. I wonder, now, as publicly very Black scholars, what knowledge can we no longer afford to keep secret? What knowledge must we no longer keep quiet and hushed? In other words, given our racialized and otherwise marked positionalities—and concomitantly, our individual and collective histories—what knowledge do we have a responsibility to reveal in the name of furthering equity and excellence in education, particularly in this very moment? Relatedly, how much of this work is truly for and about us, individually and collectively? Where are we in the work?

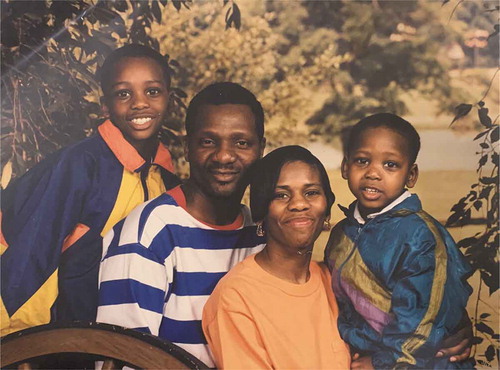

I have learned that Blackness is a compass, always pointing me home and keeping me sane in a world oriented toward (my) Black degradation. Here, home for me signals a Blackened consciousness (Biko, Citation1998), an awareness of the genius and beauty of my culture, that provides me the innate ability not to be swallowed whole by the inequities of the world that thrive off of my blood. Despite how the world seeks to position me/us, we cannot succumb to anti-Black logics. I grew up relishing in Blackness. I brought a pic of the fam’ to share (see ).

When I look at this picture, Justin, I remember what you shared earlier about equity as “leaning into the lifeworlds and knowledges of marginalized populations.” Lowkey, the fear of being too Black only lurks on the landscape of our minds if we get real about whom we imagine ourselves writing to and for. If we are producing scholarship in the traditions of the white colonial gaze of the academy (Lyiscott & The Fugitive Literacies Collective, Citation2020), then the Black radical tradition of disruption at this kitchen table is indeed too Black. However, if we are committed to writing for, to, and with the culture, then leaning into our lifeworlds is an unapologetic assertion on our part.

Contorting ourselves to behave and learn the right/white way, to not be too Black, will not save us (Love, Citation2019).

Right. As I think about this conversation, the truth is that “too Black” is very much a euphemism. Our fear of coming across as too Black is rooted in our ancestral instincts for survival. Too barbaric, too uncivilized, too ghetto, and too ratchet have been codified ways of policing Blackness for hundreds of years. Being too Black has cost our ancestors their lives. Rekia Boyd was too Black and too loud, and it cost her life. Ahmaud Arbery was too Black to go for a jog. Sandra Bland was too Black to walk away from her encounter with an officer alive. Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice were too Black. Breonna Taylor was too Black. Emmet Till was too Black. So I invite us to have some grace with each other as we grapple with our fear of being too Black in our new roles. Being too Black has material costs in our society. However, the truth is that I am Black, and I’m from the hood, and I am not willing to abandon that for this Ivory Tower.

That’s the thing, Jamila; Blackness becomes euphemistic for “the hood.” Around the world, “the hood” gestures towards “the ghetto” and “the gutter,” right? So the gutter is perceived as this dilapidated place brimming with derelicts who have been cast out of the hegemonic center of mainstream society and relegated to its margins. But here is what you and I both know from lived experience, Jamila: we know it to be true that alongside strife and struggle, the hood, ghetto, and/or gutter is ripe with knowledge regarding how those on society’s outermost margins resist and rewrite hegemonic rules about fighting for our beliefs as we heal, love, and do all else entailed in surviving and living in the fullness of our humanity while raced, gendered, classed, and otherwise marked as “other.”

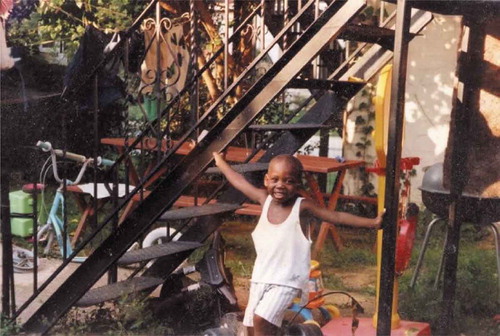

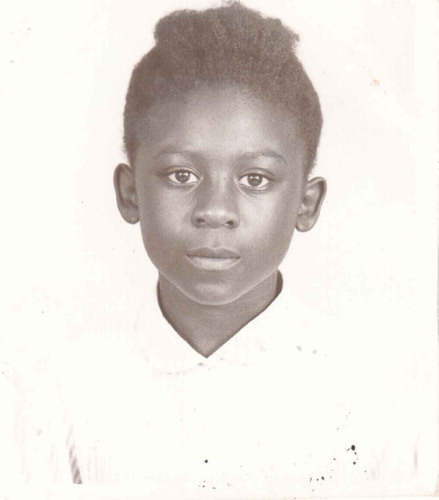

Exactly! Given the power of my upbringing, even if I wanted to believe in Blackness as all things bad, I could not. I look at my young Black boy self and refuse that (see ).

My Blackness is power, and I learned that through the oral stories of Blackness, the joys, and pains. I remember hearing stories of Black people’s mistreatment, whether against a family member or against an unrelated Black person whose name is now etched into the annals of history, and never quite feeling defeated. In fact, with each narrative, my consciousness grew, and I became more interested and adept at critiquing the ways Black suffering showed up in my personal life. I vividly remember my parents discussing the Philadelphia MOVE (The Movement) bombing with my brother and me, which took place ten minutes from our home and four years before my birth. Before the bombing, which killed five adults and six children (all Black), “police shot 10,000 rounds of ammunition in a 90-minute period from automatic weapons, machine guns, and antitank guns” (Assefa & Wahrhaftig, Citation1988, p. 3). How might the journal, under our tenure, serve as a fugitive space of refuge from the onslaughts of sufferings experienced by so many communities that are desperately in need of peace and love? I invite future authors to think about the embodied and emplaced curricula of their myriad identities and the identities of their research study participants and name them for all the world to see and digest. Bring us to your metaphorical kitchen table/s and command the use of our full tongues.

Leaning into our life worlds

*Track change: Nicki Minaj featuring Beyoncé, “Feeling Myself”*

Ok, so we’ve shared some of what we are calling for in this journal and worked through some of the questions, tensions, and joyous possibilities that come with our Blackness in this work. Can we transition into how the diversity and connectivity of our lived experiences in US schooling systems are shaping our vision for the inaugural issue and our tenure as editors of this journal? Moreover, as another layer, we gotta get into the tea of how these manuscripts, scattered across this kitchen table, breathe into the kind of vision elucidated in this conversation.

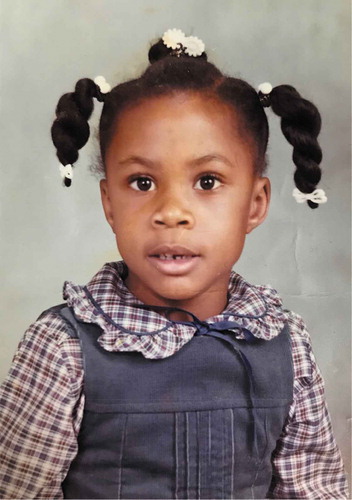

As for me, there is so much I want to say loudly and at a whisper to myself and to the other Black women and girls—the daughters of the dust—who have come before, alongside, after, through, and because of me. The invitation to peer into our own lifeworlds and be called by the fullness of our names, our difficult names, ushers me back to a time when I wanted my own name, Keisha, to be a different—more plain Jane—easier name or less Black-sounding name (see ). Now y’all know Keisha is an unmistakable Black girl name, especially those of us Black girls born in the mid to late 70s and early 80s, okay!

This is making me think of my grandmothers, aunts, cousins, play cousins, homegirls. The Black girls whose names always remind me of home.

I see you Makisha, LaKesha, Kersha, Keshia, Keeziah, Nakeysha. I see y’all; holla (and don’t get me started on the prominence of Keishas in hip hop lyrics/and movie Belly … ; we all up in the songs). Conversely—as an aside—I can recall my first encounter with a white girl named Keisha. Mind blown. I digress …

Yes! And I see you, Keisha!

My rejecting the name Keisha as a young child is an uncomfortable memory from my seven or eight-year-old self attending predominantly white private and public schools as either the only or one of few Black children in a class.

In fact, during preschool and early elementary school grades, my older brother and I attended a private academy where we were the only Black children in all of the elementary and secondary grades. For four of my formative years, I spent more than 180 days a year or approximately 720 days at 6 to 8 hours a day pervasively surrounded by, innocently enduring, instinctively navigating, and clumsily making sense of subtle and not so subtle ways that I should aspire to whiteness—a whiteness refracted by, in, and through nice, kind, polite, caring white adults and peers. Even after my brother and I bounced to attend public schools, ya girl was still occupying that “one of the only ones” status because of my tracked course enrollment in honors or Advanced Placement (AP) level courses.

Girl, those AP classes at my lily-white high school were only for those labeled as special or “gifted” by the institution. So—given my ordinariness and my Blackness—I did not, could not, belong there; and maybe being barred from those spaces was a blessing in disguise. I doubt that the whole of me would have survived there.

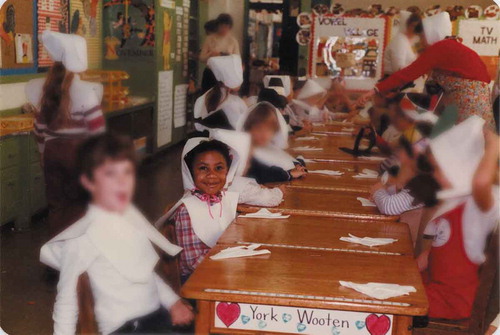

Now, to be clear, my late mother, with her fire-baptized Pentecostal holiness spirit, Gullah roots, and Geechy accent, was proudly from the low country banks and salty coast of Charleston, South Carolina. On the other hand, my father, with his occasional cotton-picking experiences, Black farmer roots turned preacher, teacher, and civil rights—lunch-counter-sittin’ and arrested to spend the night in jail at 16 years old—activist and Black firsts trailblazer is proudly from the Northern mountainous US Army Redstone Arsenal, NASA Space Center renowned Huntsville, Alabama. They worked themselves from working-class, children of manual laborers and domestics, first-generation college graduates to “we movin’ on up” and across the railroad tracks to the (white) middle class. But at what cost? What did we Black folk give up? (Purdy, Citation2018; Walker, Citation1996). This meant me, my Black girl self dressed up as a pilgrim, yo (and cheesin’)! The school and the teachers got me dressed up as a white settler enacting a colonizer’s holiday. Lookin’ back on this picture, I think, “at least y’all coulda had me dressed like my Indigenous homies, SMH!” Look at this (see )!

Oh no, not a pilgrim! LOL. Those people at the school just had to know better, but clearly not.

In these spaces, excellence in/and education was and is always measured in proximity to whiteness and, at the time, in these particular white school spaces where mine was the only skin the color of caramel with hair that coiled around itself, I desired to be disconnected from my name—kind of like when Zora Neale Hurston (Citation1928, p. 215) wrote, in How it Feels to be Colored Me, “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” Truthfully, I’m not sure if that’s what I felt back then, but what I do know is that growing up, I struggled to reconcile an unapologetic sense of my ascendance from a legacy of Black power, excellence, and genius evident in and across my home, my church, and my community of Black families, organizations, and friends. The stories, histories, literature, art, and culture passed down and through my parents and ancestors confirmed my place on a continuum, part of a rich Black diasporic heritage.

My point here is that we need to reclaim our time; we are speaking. In asking what the “future of equity and excellence must look and feel like and require for the field of education when the goal is to break free and fly away from the betrayal of educational institutions,” we remember that equity and/or excellence in education looks like naming and being clear about the socioemotional, epistemic, and ontological damage done to Black children, families, and communities who do not have access to a Center of Racial Justice and Youth Engaged Research, an Abolitionist Teacher Network, or a Cultivating Genius curriculum. Equity looks like a reclamation, a return to their rightful place in our models and frameworks for Black excellence in education. Kind of like my Dad’s favorite teacher, an exemplar Black educator, Miss Ernestine Street, who taught English, Literature, Spanish, and typing—a warm demander with high expectations of her Black students. An often-repeated memory retold by Dad: “I tried to get exempted from typing, but she wouldn’t hear it. Today, I understand why. She was my homeroom teacher and counselor. I remember her as the kindest, most impactful teacher in my life. I chose engineering and Tuskegee after she invited a recruiter from Tuskegee to talk about a career in Engineering.” To me, equity and excellence in education feels like knowing all the Keishas eeeerrrrrrywhere—even those among the Sarahs, Amys, Beckys, and Julies—have access to “heritage knowledge” and whose identity is amplified in a refusal to go dim. We come from, and are, excellence personified, and we’ve certainly paid a high price for walkin’ in our light.

Yessssssssssss!!!!!!!!!

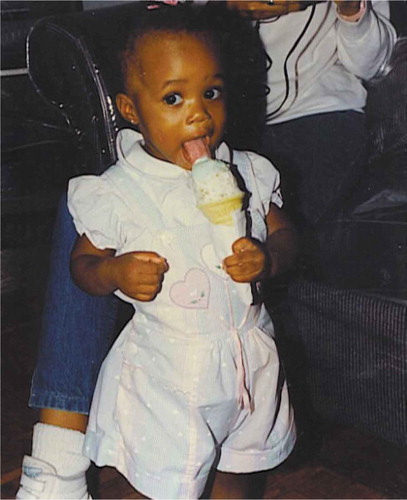

Well, in terms of my story, little Jamila was born into a colorful tapestry of culture in Brooklyn, NY, at the feet of my elders (see ). At the feet of the Black church. At the feet of hip-hop and spoken word and soca and dancehall. I am a Black Caribbean-American woman Christian poet scholar-activist. This is how I enter this work.

Yet my childhood was marked by an educational reality that honored little of this tapestry (Lyiscott, Citation2017). Black, working-class woman. These schools were certainly not built for me or with me in mind. The nuance of my Blackness growing up in a Caribbean-American community also grounded me in powerful ways. The history of my own Trinidadian culture was my first pedagogy of resistance. In Trinidad, Carnival is an annual cultural celebration that marks the assertion of Black humanity when my ancestors were not allowed to participate in the masquerade balls of their French oppressors. They created their own celebration. They affirmed their own humanity. Today in Trinidadian Carnival, you will find ornate costumes in celebration of this history. My grandfather, Valentine Ferdinand, used to build these costumes with his bare hands. He was known as “Mas man Valley” in his small town of Point Fortin, Trinidad. Here are some pictures of him and a few of the costumes he built in the 1970s and 1980s (see ). This is the rich culture of survival, joy, and resistance that has shaped me. And it is shaping how I show up to our collective vision for our editorship. As much as I am a Black scholar, please know that there is no neat binary that separates me from my hood—even in the face of “the hood” as code for what is societally disparaged and exploited, as you shared earlier, Esther. We often get caught up in language about doing research “on communities” as if our communities are distant objectifiable realities that we can translate into APA format. Nah. I am my community, and I am my hood. As we think about the future of equity and justice in education, I am reaching to my past self, who did not have access to the kind of inclusive worlds that we are dreaming of. I am reaching into my community’s collectivity that values what academia cannot value, especially because it cannot be measured—spirit, affect, and rhythm. A knowing and a being that exists powerfully across Black, Indigenous, and communities of color. That’s who I’m doin’ it for.

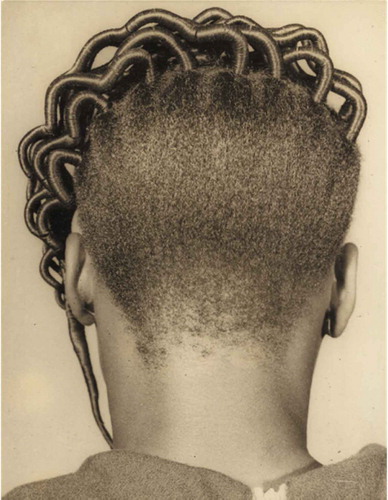

Yes, this is what I was getting at earlier. The curriculum of the hood, the gutter—like the curriculum of Blackness—travels across space and traverses place, linking the knowledge generation of Black kin/folk within and across generations and hemispheres, from Brooklyn to Nairobi to Lagos to Los Angeles to London to Raleigh and so on. The curriculum of the gutter, like the curriculum of Blackness, is inherently plural. In hoods and gutters across the African diaspora, beautifully (extra)ordinary Blacknesses are the texts from which Black kin/folk make meaning (of themselves). Here, (our) beauty is defined and documented for us, by us, as illustrated by visual artist “[J.D.] Okhai Ojeikere’s extensive oeuvre. The late Nigerian photographer produced thousands of images as part of his ‘Hairstyles’ project, visual anthropological and ethnographic cultural artifacts of Nigerian sisters’” hairstyles and headdresses; records of quotidian “moments of beauty, moments of knowledge” (Ojeikere, as cited in Ojeikere et al., Citation2000, no page); moments of Black life blooming in locales (mis)read, (mis)perceived, and (mis)named by the West as gutters. Take a look at one of his images (see )—this is one of my favorites.

This is beautiful, Esther! How have you began to make connections between your past self/selves and how we might vision forward?

I’ve been reflecting on the question of who I am and how I show up in this editorial vision. I am a transdisciplinary, transnational, multilingual/multi-tongued, ratched-ish, woman(ist) scholar. I was once a Black schoolgirl, and I was taught by far too many teachers on two continents to view the darkness of the gutter as wretched. I am also a first-generation Black African immigrant to the United States. I have a bloodline that stretches to Gor Mahia and Luanda Magere, fierce warriors among the proud culturally and ethno-linguistically linked Luo people of East and Central Africa (see ).

But I didn’t feel like I had much to be proud of as a youth growing up among the often invisibilized working-poor class in the United States. My parents—although both “highly educated”—spent most of their adulthood as US immigrants strangled by a confluence of structural oppressions that made it impossible for them to own a home outright and plant the seeds for the elusive “American dream” of intra- let alone inter-generational wealth. I know now that home is where my people are, so my people are my inheritance. I am most at home with my people in places around the African diaspora, such as Nairobi, Kisumu, London, and on and on. Jamila, I love that for you and me, the invocation of the hood or the gutter necessarily means different things because your childhood in a Brooklyn neighborhood was vastly different from mine in Nairobi’s Lang’ata Estate.

Yes, I love to see it! Any pics of little Esther Oganda/Essie/Nyaugenya for us to love on?

LOL. Of course, of course. Check this one out (see ).

Come through, Essie; serving face!

LOL! I try.

Alright, y’all; let’s turn to the manuscripts.

Figure 6 Jamila’s grandfather, Valentine Ferdinand, in Point Fortin, Trinidad, ca. 1980, standing beside his hand-made Carnival costumes

Figure 7 Doin’ it for the culture: Ojo Npeti/Kiko. (Ojeikere, Citation1968)

Figure 8 Luo warriors in South Nyanza, Kenya, ca. 1902, attired in warrior dress with spears, shields, and headdresses made of Colobus monkey tail hair and ostrich plumes. The style of adornment and shields are typical of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century period for the Luo. (Pitt Rivers Museum Luo Visual History, Citation2008)

At the feet of communal wisdom

*Track change: The Wiz Stars featuring Diana Ross & Michael Jackson, “A Brand New Day”*

Jamila: As I read across the gift of each of these manuscripts, I felt so connected to a sense of collective wisdom. The kind of collectivity that brought the four of us together for this editorship. It resonates deeply with the sense of community that shaped my upbringing. I’m reading through the new heat that these scholars offer as they lend wisdom to our collective vision for, to, and with the culture. Moreover, the fact that Dillard (this issue) made sure to center Queen Bey in this conversation is everything! Her piece, “When Black is [Queen]: Towards an Endarkened Equity and Excellence in Education,” begs questions about how elders in education might engage our generation of Black thinkers, movers, and shakers in the world. She centers Beyonce as a popular cultural Black feminist figure for us to learn from and leaves us with the question, “how might we invite a future of excellence and equity in Black education that more thoughtfully and carefully curate spaces where Black being is the table?” (Dillard, this issue). This piece was fire! Camangian’s piece hit home for me too, y’all! Under the title, “Let’s Break Free: Education in Our Own Image, Voice, and Interests,” Camangian explores “the aspirations of multiply marginalized and colonized people in the United States” to advocate for research that must value our full selves and work to dismantle interlocking systems of oppression. We’ve been thinking so much about how equity must be (re)visioned in the future of this journal, and he hits us with a hard truth:

European society is sitting on and alienating Third World people from resources that are inherently theirs, and assimilation frameworks of educational equity position oppressed people to work extremely hard to access very small pieces of what ought to be theirs in the first place. (Camangian, this issue).

Keisha, what resonated with you in the manuscripts around what it means to do it for the culture in the future of this journal and the work of equity and social justice, broadly?

In part, we learn from one of our academic OGs, Ladson-Billings, that doing it for the culture requires a refusal to do business as usual. We not fallin’ for the okey doke here. In her piece “I’m Here for the Hard Re-Set: Post Pandemic Pedagogy to Preserve Our Culture,” Ladson-Billings positions the COVID-19 pandemic as generative chaos and an opportunity to shift oppressive, prevalent norms in curriculum and instruction. Returning back to “normal” is not an option, especially as public schools have overwhelmingly failed Black children. The pandemic creates an opportunity to rethink “business as usual” and reconsider rethinking education for Black children. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (CRP) is a site of possibility. Ladson-Billings reminds us about the components of an approach to teaching racially diverse learners that she introduced decades ago and suggests we use CRP to reboot education during and post-pandemic or, as she writes, “re-set around technology, curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, and parent/community engagement that will support and promote students’ culture.” Drawing on Arundhati Roy’s claims that the pandemic is a portal, Ladson-Billings asserts that by “re-deploying culturally relevant pedagogy,” we can override outdated notions of normalcy and, instead, go for the “hard re-set” in education for the culture. Our sister scholar, Susan Wilox, offers us a way to think about what the future of equity in education might mean for our young people. In her article, she asks, “What can we learn from ‘witnessing as pedagogy’ about nurturing the educational excellence of BIPOC and LGBTQ youth in an out-of-school space?” Wilcox theorizes two types of witnessing—as acts of bearing, a kind of holding space for others, and baring, a kind of revealing of oneself—reflecting on her experiences with Black and Latinx women facilitators and teachers who theorize pedagogies of witnessing as a method for affirming the inherent worthiness of Black and Brown youth. These youth are empowered by democratic spaces where pedagogies of witnessing are present. Notably, the space referenced in Wilcox’s piece is outside of school. So, what does educational success look like in a setting where grades do not define young people’s excellence?

In “A Pedagogy for Black People: Why Naming Race Matters,” David Kirkland details how in critical pedagogies that seek to culturally sustain and be responsive to communities, the absence of naming, or as he notes unaming, “obscures the reality that such pedagogical statements are also neither neutral nor politically innocent” (this issue). In our efforts to engage in research to unearth new possibilities that get us closer to equity, what might it mean to leverage racial and/or ethnic specificity? Moving through Kirkland’s article, one finds themselves witnessing an embodiment of what we have framed as doin’ it for the culture in educational research. Kirkland (Citation2013, Citation2017), who has written extensively about the rich literacy practices of Blackness and particularly Black boys, which in itself has served as a tapestry of pedagogy for Black people, invites readers to take seriously the power of naming race in research, particularly in work intended to be culturally relevant and sustaining.

In direct conversation with Kirkland, Keffrelyn Brown’s article, “What Do Black Students Need?: Exploring Perspectives of Black Writers Writing Outside of Educational Research,” explicitly focuses on racial specificity in working towards equity and justice. Doin’ it for the culture, Brown theorizes what Black students in schools need through the lens of Black non-education researchers (W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, and Melinda Anderson) gathered across from what she has noted as three critical time periods in Black history: “the Jim Crow era; the Civil Rights era; and the post-integration/contemporary era” (this issue). What might be made possible if educational researchers spent more time engaging with writing from non-education researchers or community scholars that write about the particularities of the populations we seek to research, untethered to the restrictions and structures of our disciplinary knowledge? Both Kirkland and Brown provide a call to action in their pieces, challenging researchers to explicitly name race, here blackness, to catalyze the future of equity educational research. It is my hope that everyone who reads these works deeply considers how they are explicitly naming and honoring the communities they are researching with and for. It is time to make the unseen and unnamed highly visible.

Justin, I am inspired by the truths the authors in this special issue are boldly naming. They remind us of what we been knew; that for BIPOC scholars and communities, the fight for equity and excellence in education is a fight for our healing, our survival, and our very lives. In “Dreams, Healing, and Listening to Learn: Educational Movements in the Everyday,” Alayna Eagle Shield, Michael Munson, and Timothy San Pedro (this issue) allow us to eavesdrop on their intimate dialogue. The trio instantiates the embodied, emplaced, and relational dimensions of education. Eagle Shield (Tip of the Horn Lakota, Lives on Knives and Dwellers of the Sacred Lake Dakota, and Sáhniš/Arikara), Munson (Selis, Ql̓ispe, and other ancestories), and San Pedro (Filipino-American raised on the Flathead Indian reservation in Western, Montana) share personal stories in a conversation that elucidates the particular ways that they have grappled with the tension between schooling and education in their BIPOC-centered, education and justice-driven lives. The authors ask us “to pause for a moment … and sit with the following question”:

When envisioning education beyond school walls,

When we practice our pedagogy in ways that remove

walls blockading and dividing school from community,

When we alter our perceptions that education

is central to nation-building—

What richness in languages,

in stories,

in history,

might breach that which separates us,

connecting us to a richer, fuller education

for our students? (this issue)

Their meditation is a poignant contribution that emphasizes what is at stake and what is possible when justice-oriented scholars turn our compass/es to issues of equity and excellence in education, not schooling. The rhythmic poetry of Black gospel music is audible in Chezare Warren’s “From Morning to Mourning: A Meditation on Possibility in Black Education.” The epigraph to this article invokes a tune by African-American music royalty, The Winans and Anita Baker (Winans, Citation1987); a europrically mournful reminder that

Ain’t no need in worrying, what the night is gonna bring, it’ll be all over in the morning … There’s a fear of nightfall. When darkness comes and covers all, always … Sometimes we feel pain. But there are things that we can change …

The nighttime—a term Warren explains as “perhaps code for shame, depression, isolation” (this issue) and other such feelings and states typically associated with dark gloom—is rarely discussed in education research, although for Black people, formal education has been one long, pitch-black night, both in the United States and arguably, around the world, given the viral spread of anti-Blackness globally. Warren situates these musings at the intersection of Black spirituality studies, Black cultural studies in education, and the critical study of Black education in the United States. The author’s linking of morning, mourning, Blackness, and education is refreshing, and their theorizing captivatingly weaves together critical insights that push us to (re)view issues of equity and excellence in Black education through mournful eyes.

At the end of this conversation and after reading across all of the manuscripts, I am left full of questions that I hope we can answer together in our collective editorship: What does it mean to both preserve and imagine? To embody and bear witness? To name and transcend the circumscription of race? To write within and beyond the boundaries of traditional educational research? To forge pathways toward possibility against a backdrop of mourning? To dream, heal, listen, and learn from the everydayness of educational movements that exist beyond the scope of the white colonial gaze? To devise an education in our own image, interests, and voices? To endarken our perspectives of equity in the field of education? What does it mean to do it for the culture? What does it mean to dream into a radical imagination centered on joy and futurity?

Yes, Jamila. Ultimately, this special issue insists that even as we long for an equitable world, we who are warriors for equity and justice in education must remain steadfast in our belief that, sure as day, the morning will come. Yet, still, there are lessons we can learn in this prolonged moment of mourning for knowledge that has been taken from us, invisibilized and erased; knowledge we must (re)claim, day by day, night by night. “There is joy at night” (Warren, this issue); for it is in the wee hours of the night that we remember to stretch out our arms; for it is in the darkness that we desire each other; that we reach for the other. And here, in each others’ arms, is where we learn beyond doubt that “Dua kur gye enum a obu.”Footnote1 This lesson comes to light only if and when we are brave enough to be still, be bold, and beholden to each other in the starry, hope-full, pitch Black night—we others, we humans, just like you.

Kitchen-table playlist

Track 1: Erykah Badu, “On and On”

Track 2: Shaybo, “Daily Duppy”

Track 3: Nicki Minaj featuring Beyoncé, “Feeling Myself”

Track 4: Diana Ross, Michael Jackson & The Wiz Stars, “A Brand New Day”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Rooted in the cultural knowledge of the Akan people of southern and central Ghana, this Twi proverb translates to “One tree alone cannot stand the wind,” meaning, there is unity in strength.

References

- Assefa, H., & Wahrhaftig, P. (1988). The MOVE crisis in Philadelphia: Extremist groups and conflict resolution. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Badu, E., & Jamal, J. (1996). On & on. [Recorded by E. Badu]. On Baduizm [CD]. Santa Monica, CA: Universal Records.

- Biko, S. (1998). The definition of Black consciousness. In P. H. Coetzee & A. P. J. Roux (Eds.), Philosophy from Africa: A text with readings (pp. 360–363). International Thomson Publishing.

- Brown, D. L. (2018, July 12). Emmett Till’s mother opened his casket and sparked the civil rights movement. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/07/12/emmett-tills-mother-opened-his-casket-and-sparked-the-civil-rights-movement/

- Coles, J. A. (2018). The costs of whistling, orange juice, and skittles: An anti-Black examination of the extrajudicial killings of Black youth. In K. J. Fasching-Varner, K. Tobin, & S. M. Lentz (Eds.), #BrokenPromises, Black deaths, & Blue Ribbons: Understanding, complicating, and transcending police-community violence (pp. 5–8). Brill.

- Coles, J. A. (2021). It’s really geniuses that live in the hood”: Black urban youth curricular un/makings and centering Blackness in slavery’s afterlife. Curriculum Inquiry, 1–22. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2020.1856622

- Crawley, A. T. (2016). Blackpentecostal breath: The aesthetics of possibility. Duke University Press.

- Dillard, C. B. (2012). Learning to (re)member the things we’ve learned to forget: Endarkened feminisms, spirituality, and the sacred nature of research and teaching. Peter Lang.

- Dumas, M. J. (2013). ‘Losing an arm’: Schooling as a aite of Black suffering. Race Ethnicity and Education, 17(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2013.850412

- Dumas, M. J. (2016, February 11). Things are gonna get easier: Refusing schooling as a site of Black suffering. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/schooling-a-site-black-suffering_b_9205914

- Hurston, Z. N. (1928). How it feels to be colored me. World Tomorrow, 11, 215–216.

- Kirkland, D. E. (2013). A search past silence: The literacy of young Black men. Teachers College Press.

- Kirkland, D. E. (2017). Beyond the dream: Critical perspectives on Black textual expressivities between the world and me. English Journal, 106(4), 14–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26359456

- Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than just survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

- Lyiscott, J. (2017). Racial identity and liberation literacies in the classroom. The English Journal, 106(4), 47–53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26359462

- Lyiscott, J., & The Fugitive Literacies Collective. (2020). Fugitive literacies as inscriptions of freedom. English Education, 52(3), 256–263.

- Ojeikere, J. D. O. (1968). Ojo Npeti/Kiko HD24/68. The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles. https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/255253/jd-’okhai-ojeikere-ojo-npetikiko-hd2468-nigerian-1968/

- Ojeikere, J. D. O., Magnin, A., & Oyairo, E. A. (2000). J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere: Photographs. Scalo Verlag Ac.

- Pitt Rivers Museum Luo Visual History. (2008, June 6). 1998.209.43.8. Pitt Rivers Museum. http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/Luo/luo/photo/1998.209.43.8/index.html

- Purdy, M. A. (2018). Transforming the elite: Black students and the desegregation of private schools. University of North Carolina Press.

- Sharpe, C. (2016). In the wake: On Blackness and being. Duke University Press.

- Shire, W. (2016). Warsan Shire poetry [Tumbrl]. https://warsanshirepoetryreblogs.tumblr.com/?og=1

- Tohe, L. (1999). No parole today. Albuquerque, NM: West End Press.

- Walker, V. S. (1996). Their highest potential: An African American school community in the segregated south. University of North Carolina Press.

- Winans, M. L. (1987). Ain't no need to worry. [Recorded by The Winans & A. Baker]. On Decisions [CD]. Burbank, CA: Word Entertainment/Qwest Records.