?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Previous research has shown that mock and actual jurors give little weight to actuarial sexual offending recidivism risk estimates when making decisions regarding civil commitment for so-called sexually violent predators (SVPs). We hypothesized that non-risk related factors, such as irrelevant contextual information and jurors’ information-processing style, would influence mock jurors’ perceptions of sexual recidivism risk. This preregistered experimental study examined the effects of mock jurors’ (N = 427) need for cognition (NFC), irrelevant contextual information in the form of the offender’s social attractiveness, and an actuarial risk estimate on mock jurors’ estimates of sexual recidivism risk related to a simulated SVP case vignette. Mock jurors exposed to negative risk-irrelevant characteristics of the offender estimated sexual recidivism risk as higher than mock jurors exposed to positive information about the offender. However, this effect was no longer significant after mock jurors had reviewed Static-99R actuarial risk estimate information. We found no support for the hypothesis that the level of NFC moderates the relationship between risk-irrelevant contextual information and risk estimates. Future research could explore additional individual characteristics or attitudes among mock jurors that may influence perceptions of sexual recidivism risk and insensitivity to actuarial risk estimates.

An estimated 6,500 people in the United States are believed to present a risk of sexual reoffending that is sufficiently high to warrant indefinite confinement in a detention facility (Koeppel, Citation2019). These individuals are civilly committed pursuant to Sexually Violent Predator (SVP) or Sexually Dangerous Person (SDP) statutes, which have been enacted by the federal government and 20 states (Knighton et al., Citation2014). These laws permit confinement of an individual who has been charged with,Footnote1 or convicted of a sexual offense for which he or she has served their prison sentence (Knighton et al., Citation2014).

Most often, jurors decide whether the individual against whom an SVP petition is brought – also known as the respondent – meets the requisite legal criteria for SVP civil commitment (Krauss & Scurich, Citation2014; Lieberman et al., Citation2007; Zolfo, Citation2018). These legal criteria are: (a) the respondent has a history of sexual offending; (b) the respondent has a mental abnormality or personality disorder; (c) the respondent has some volitional impairment (i.e. difficulty controlling his or her sexual behavior); and (d) as a result of these factors, the respondent is likely to engage in future sexual offending (emphasis added; Kansas v. Hendricks, Citation1997). In most cases, at least one forensic mental health professional – called an SVP evaluator – offers expert testimony about whether the respondent meets each of the legal criteria (Jackson et al., Citation2004; Jackson & Hess, Citation2007). Ideally, jurors should make decisions based on the expert’s science-based estimate of the risk that the respondent will engage in future sexual offending (Boccaccini et al., Citation2014; Guy & Edens, Citation2003; Janus & Prentky, Citation2008; Krauss et al., Citation2012; Miller et al., Citation2005; Scurich & Krauss, Citation2013; Sreenivasan et al., Citation2003).

Actuarial risk estimates and juror decision making in SVP cases

SVP evaluators most often use actuarial risk assessment instruments (ARAIs; Janus & Prentky, Citation2003) for the purpose of estimating the likelihood of sexual reoffending (Barbaree et al., Citation2001; Janus & Prentky, Citation2003; Murrie et al., Citation2009). In fact, for several decades, researchers have consistently found that ARAIs provide more accurate estimates of violent or sexual recidivism than predictions based on unstructured clinical judgment alone (Ægisdóttir et al., Citation2006; Grove & Meehl, Citation1996; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2009). SVP evaluators commonly use the Static-99R (Helmus et al., Citation2012) or its predecessor, the Static-99 (Hanson & Thornton, Citation1999), to assess the likelihood of sexual reoffending (Krauss et al., Citation2018). The Static-99R differs from the original version only in different scores associated with the offender’s age at release (Boccaccini et al., Citation2017).

Accurate risk-relevant information derived from ARAIs is particularly important in SVP hearings because the general public tends to grossly overestimate the risk of sexual reoffending (Ellman & Ellman, Citation2015; Katz-Schiavone et al., Citation2008; Levenson et al., Citation2007). Levenson and colleagues (Citation2007) reported that among a sample of laypeople, the average estimate was that 74% of persons convicted of a sexual offense would reoffend. In contrast, observed recidivism rates among persons who have been convicted of a sexual offense range between 5-15% (Alper & Durose, Citation2019; Hanson et al., Citation2014; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2005, Citation2009; Harris & Hanson, Citation2004; Helmus et al., Citation2012; Phenix, Helmus, et al., Citation2016). Therefore, objective risk estimates derived from ARAIs can ostensibly correct jurors’ apparent overestimates of sexual recidivism risk.

SVP evaluators often discuss ARAI results in their testimony at SVP hearings. Despite the finding that jurors in real SVP cases appear to believe forensic evaluators who use actuarial instruments make more accurate estimates of reoffending risk than evaluators who use only unstructured clinical judgment (Boccaccini et al., Citation2014), both mock jurors and actual jurors in SVP civil commitment hearings tend to give little weight to expert testimony based on ARAIs (Boccaccini et al., Citation2013; Guy & Edens, Citation2003; Krauss & Sales, Citation2001). Some studies suggest jurors are influenced by factors unrelated to recidivism risk, including the likability or credibility of the expert (Batastini, Hoeffner, et al., Citation2019), and give more weight to these factors than to the expert testimony about actuarial risk estimates (Boccaccini et al., Citation2013; Krauss et al., Citation2012; Krivacska, Citation2011; Turner, Chamberlain et al., Citation2015).

In other words, most previous studies that examine the effects of ARAI risk information on jurors’ perceptions of sexual recidivism risk cannot differentiate between the effects of the ARAI risk information itself and juror perceptions of expert or attorney likability/credibility on perceptions of the SVP respondent’s risk of sexual recidivism, because the two information sources are confounded. For example, participants in Krauss et al. (Citation2012) watched a 1-hour video simulation of an SVP trial that included testimony from a psychological expert witness and opening statements from both the petitioner’s (the state) and the SVP respondent’s attorney. The expert in the Krauss et al. study testified that he had used two ARAIs, but the risk estimates derived therefrom were not mentioned by the expert – only that the ARAIs had been completed as part of the risk evaluation.

In fact, we are aware of only one previous experimental study that does not employ some form of expert testimony or attorneys’ arguments (either in video or written format) in SVP civil commitment studies. Varela et al. (Citation2014) examined how varying the communication format of Static-99R risk information affects jurors’ sexual recidivism risk estimates in an SVP civil commitment context. Specifically, they varied the format of a Static-99R risk estimate as a categorical estimate (i.e. low or high risk), a relative risk ratio (i.e. the offender would be expected to have a [three-fourths recidivism rate] or [2.91 times higher than the recidivism rate] of the ‘typical sexual offender’), or a recidivism rate (i.e. [9.4%] or [31.2%] were re-arrested for a sexual offense within five years). Varela and colleagues then measured how the communication format affected 211 prospective jurors’ ratings of an SVP respondent’s sexual recidivism risk. They found no significant main effect of communication format on jurors’ perceptions of recidivism risk based on Likert scale ratings of the likelihood of sexual reoffending within five years.

However, there was a significant interaction effect between the risk communication format and the risk level indicated by the Static-99R information. When participants read recidivism risk information derived from the Static-99R (score of 6) that was presented in a categorical format (i.e. ‘high risk’), they rated the risk of recidivism as significantly higher than those who read about a recidivism rate (i.e. of men who scored a 6 on the Static-99R, 31.2% were re-arrested for a sexual offense within five years; d = .68, medium to large effect). There was no significant interaction effect when the Static-99R indicated a score of 1 (i.e. ‘low risk’). In other words, when the Static-99R results indicated higher than average risk of sexual recidivism, participants in the Varela et al. study rated the risk as significantly lower when they were provided with a recidivism rate rather than a categorical risk estimate.

Still, it remains unclear why jurors do not appear to make effective use of actuarial risk estimates, particularly as communicated by forensic evaluators in SVP civil commitment hearings (Miller & Brodsky, Citation2011; Pennycook et al., Citation2014; Turner, Boccaccini et al., Citation2015; Walters et al., Citation2014). Perhaps they are influenced by characteristics of the expert witness, or perhaps certain risk communication formats are more effective than others. At present, there is no experimental research that can help disentangle these various effects. Furthermore, we are unaware of any previous experimental study that directly examines whether risk-irrelevant factors have an independent effect on jurors’ perceptions of an SVP respondent’s sexual recidivism risk and whether that influences their apparent insensitivity to a risk estimate derived from an ARAI. Yet, the Varela et al. (Citation2014) findings suggest that, in some circumstances, providing jurors with a risk estimate – particularly a recidivism rate – that is independent of expert effects may be helpful in promoting jurors’ estimates of sexual recidivism risk that are more in line with the results of an ARAI.

Juror neglect of actuarial risk estimates

While some researchers have suggested that a lack of knowledge about science (Batastini, Hoeffner, et al., Citation2019) or a lack of numeracy (Krauss et al., Citation2004; Krauss & Lee, Citation2003; Krauss & Sales, Citation2001) may account for jurors’ tendency to discount expert testimony based on ARAI results, others have argued that individual differences may contribute to how information is perceived and integrated in the context of legal decision-making (Gunnell & Ceci, Citation2010; Krauss et al., Citation2004; Lieberman, Citation2002; Lieberman et al., Citation2007). Research examining how potentially biasing factors, such as risk-irrelevant information, affect jurors’ risk perceptions may help clarify jurors’ apparent insensitivity to actuarial risk estimates (Krauss & Sales, Citation2001; Lieberman et al., Citation2007).

Risk-irrelevant contextual information and juror decision making in SVP cases

We define risk-irrelevant contextual information as those factors that, on their own, have not been proven to be empirically associated with sexual recidivism. Examples are: type of employment, number of previous marriages, volunteerism, public outrage about the crime, and the victim’s opinion about the sufficiency of a criminal sentence. Yet, risk-irrelevant contextual information (such as emotionally-evocative victim statements) has been found to bias psychologists, thereby causing these experts to increase their estimate of an SVP respondent’s risk of future sexual offending (Jackson et al., Citation2004). Furthermore, risk-irrelevant contextual information, such as the respondent’s social attractiveness or likability (Alicke & Zell, Citation2009; Landy & Aronson, Citation1969; Michelini & Snodgrass, Citation1980; Richardson & Campbell, Citation1982), media stories and public reactions to an offense, as well as the victim’s view of the fairness of the punishment for the crime (Robinson et al., Citation2012), has been shown to affect attributions of guilt and sentencing decisions in criminal cases (Abel & Watters, Citation2005; Alicke & Zell, Citation2009; Michelini & Snodgrass, Citation1980).

The psychological phenomenon known as the halo effect could perhaps account for this biasing effect. The halo effect refers to the human tendency to make unconscious judgments about the specific attributes of an individual based on one’s global assessment of the individual (Nisbett & Wilson, Citation1977). For example, Nisbett and Wilson (Citation1977) found that whether a teacher was rated as ‘warm’ or ‘cold’ by students had a significant and pronounced effect on ratings of the teacher’s physical attractiveness, mannerisms and accent. When the teacher was perceived as warm, participants provided significantly higher ratings of the teacher’s physical attractiveness and rated his mannerisms and accent as significantly more appealing, whereas participants who perceived the teacher as cold rated him as less physically attractive and his mannerism and accent as more irritating. Therefore, we suspect bias created by risk-irrelevant contextual information may generate a global impression of a ‘good’ versus a ‘bad’ person, which then impacts the juror’s estimate of recidivism risk (Gunnell & Ceci, Citation2010; Hilton et al., Citation2005, Citation2015). Yet, there is limited research on whether and how risk-irrelevant contextual factors may influence jurors’ case-specific estimates of reoffending risk or SVP civil commitment decisions (Boccaccini et al., Citation2013).

Need for cognition and decision making

Individuals differ in the extent to which they enjoy expending cognitive effort to understand a situation, a characteristic known as need for cognition (NFC; Cacioppo & Petty, Citation1982). The Need for Cognition Scale (Cacioppo & Petty, Citation1982) is a measure of NFC (Cacioppo et al., Citation1984). People with low NFC scores tend to process information experientially, which means they engage in rapid decision-making that is largely unconscious, emotion-driven and leads to conclusions based on generalizations (Epstein, Citation1993). They also tend to focus on peripheral cues, such as the attractiveness or likability of the source of information (Cacioppo et al., Citation1996; Haugtvedt et al., Citation1992), and pay little attention to the quality of the information (Cacioppo et al., Citation1996; Shestowsky & Horowitz, Citation2004).

On the other hand, people with higher NFC scores appear more likely to use a rational approach by exerting conscious effort to seek evidence and apply logic in their thinking (Epstein, Citation1993). They are more likely to evaluate the quality of arguments contained in a message than those who are lower in NFC (Cacioppo et al., Citation1983, Citation1996). Based on cognitive-experiential self-theory (CEST), people use both rational and experiential modes of information processing, but individual differences and situation-specific factors determine which mode is predominant in guiding behavior (Denes-Raj & Epstein, Citation1994).

Previous research has revealed that when people are encouraged to think analytically, they tend to be more influenced by testimony based on actuarial risk estimates than testimony based on unstructured clinical judgments in SVP cases (cf., Krauss et al., Citation2012; Lieberman et al., Citation2007; Lieberman & Krauss, Citation2009). Therefore, we hypothesize that jurors who are higher in NFC are more likely to render an estimate of the likelihood of sexual reoffending by the SVP respondent that aligns with that indicated by an ARAI than jurors who are lower in NFC.

Although a number of studies about juror decision-making suggest that jurors who score lower on NFC may be more persuaded by clinical testimony about sexual recidivism risk than the same testimony based on an actuarial risk estimate (Gunnell & Ceci, Citation2010; Krauss et al., Citation2004; Lieberman et al., Citation2007), some studies indicate that mock jurors may be more influenced by testimony based on actuarial risk estimates when they are encouraged to think rationally and analytically (Lieberman et al., Citation2007; Lieberman & Krauss, Citation2009). Yet it is unclear whether individuals’ natural inclination to rationally and analytically weigh evidence predicts their ability to adequately utilize actuarial risk information when also confronted with potentially biasing risk-irrelevant information. Such research may provide insights into how individual differences among jurors affect how they integrate both types of information in their judgment of risk.

The current study

Given that most SVP cases are decided by jurors (Lieberman et al., Citation2007; Zolfo, Citation2018), the aim of this preregistered experiment is to gauge whether and how potentially biasing contextual information may affect jurors’ estimates of sexual reoffending risk in the context of an SVP case when they are provided with both risk-irrelevant and risk-relevant information about the respondent. Therefore, we examined whether bias affects mock jurors’ perceptions of sexual reoffending risk, whether more objective risk estimates derived from a risk assessment instrument can counteract such bias among mock jurors, and whether NFC as an individual trait variable moderates the amount of bias in mock jurors’ risk estimates.

First, we examined whether mock jurors’ perceptions of the likelihood of sexual reoffending are affected by either positive or negative irrelevant contextual factors in a simulated sexual offender civil commitment case. We selected factors that are not empirically associated with sexual offender recidivism, hence our use of the term risk-irrelevant. For example, in the positive contextual information condition, the respondent is portrayed as more ‘socially attractive’ in that he had a long record of employment as a bank manager, he volunteered at a homeless shelter, and played the organ at church. In contrast, in the negative information condition, the respondent is portrayed as less socially attractive because he had been employed for a brief time in his job as a janitor, a neighbor described him as ‘odd,’ and he played online games in his free time. We hypothesized that participants who receive negative contextual information would provide higher estimates of the likelihood of sexual reoffending before receiving any information on actuarial recidivism risk (Time 1; T1) than would participants who received positive contextual information (H1).

Second, we measured the extent to which mock jurors adjusted their perceptions of the likelihood of sexual reoffending after reviewing the respondent’s Static-99R information indicating moderate risk (Time 2; T2). Based on previous research that suggests jurors give relatively little weight to actuarial risk estimates (Boccaccini et al., Citation2013; Krauss & Sales, Citation2001; Turner, Boccaccini et al., Citation2015), we expected that mock jurors who have previously received risk-irrelevant negative contextual information about the respondent would rate him as significantly more likely to reoffend at T2 than mock jurors who received risk-irrelevant positive information, despite the presentation of the same risk-relevant Static-99R information to both groups (H2).

Third, we evaluated the extent to which mock jurors’ level of NFC moderated the effect of Static-99R information on their T2 estimates of the likelihood of the respondent sexually reoffending. Accordingly, we expected that the effects of risk-irrelevant information on reoffending risk estimates at T2 would vary based on the mock jurors’ level of NFC, such that the effects would be larger among mock jurors with lower NFC scores (H3).

Most previous studies that have examined the effects of ARAI information on jurors’ estimates of the likelihood that an SVP respondent will reoffend are based on expert testimony about ARAI results (Boccaccini et al., Citation2013; Guy & Edens, Citation2003; Krauss et al., Citation2012; McCabe et al., Citation2010; Scurich & Krauss, Citation2014; Turner, Boccaccini et al., Citation2015). The findings from these studies suggest that jurors are not strongly influenced by such expert testimony (Boccaccini et al., Citation2013; Krauss et al., Citation2012; Turner, Boccaccini et al., Citation2015). Yet, it is difficult to separate the effects of expert testimony from the content of the testimony as the effect of the information itself may be obscured by factors such as the expert’s credibility (Edens et al., Citation2012) or likability (Batastini, Hoeffner, et al., Citation2019). Therefore, we presented the Static-99R results to jurors as they might be conveyed in an expert’s written report, rather than through the filter of an expert’s testimony.

The preregistration for this study can be found at https://osf.io/wr48v/?view_only=fdd52d991e0a491c8f2b3d3901b0a4b7.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) and required to be at least 18 years of age, proficient in English, and reside in the United States. We limited our sample to U.S. residents for two reasons. First, we expected that Americans may have different views regarding how people who have committed a sexual offense should be managed, compared to people in other countries. Second, the SVP civil commitment system in the U.S. is different than other countries, particularly with respect to the fact that jurors often decide whether a person convicted of a sexual offense should be civilly committed (Janus, Citation2013; Witt & DeMatteo, Citation2019). We also required that participants have at least a 99% approval rating on MTurk and must not have participated in the pretesting phase of the study in which we evaluated the strength of the manipulation.

We planned to exclude participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria, who did not complete the study, who failed one or more attention checks, or indicated that their data should not be used (Meade & Craig, Citation2012). We also planned to exclude participants whose total time spent on the study was more than three times the median absolute deviation below the sample median (Leys et al., Citation2013), but none met this criterion.

In addition, we set an exclusion criterion on a per-analysis basis such that we would exclude participant responses whose T1 or T2 reoffending risk estimates were more than three times the median absolute deviation above or below the corresponding sample median (Leys et al., Citation2013). No participants met this exclusion criterion based on their T1 risk estimates. However, we encountered 100 participants (23.4%) whose T2 risk estimates were more than three times the median absolute deviation above the sample median. This rate of exclusion is far above what would be considered as representative of true outliers. Therefore, this group of participants was not excluded from the main analyses. Instead, the T2 risk estimates were log-transformed to address the skewness in the data (see Results).

Of the 427 participants whose data were analyzed, 240 identified as male (56.2%), 181 identified as female (42.4%), two identified as transgender male (0.5%), one identified as gender variant/non-conforming (0.2%), one identified as an option not listed (0.2%), and two declined to provide gender identity information. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 75 years (M = 37.7, SD = 11.47). The highest education level varied from less than a high school diploma (n = 2; 0.5%) to participants who had a professional (n = 4; 0.9%) or doctoral (n = 4; 0.9%) degree. About 43.3% held a bachelor’s degree (n = 185), 11.5% had an associate’s degree (n = 49), and 21.1% had some college education (n = 90). Participants who had a high school diploma as their highest level of educational attainment comprise 10.3% of the sample (n = 44). Nearly every U.S. state (n = 46) was represented, of which the highest number of participants resided in California (n = 50; 11.7%). Three participants did not provide their state of residence. Seventy-two (16.9%) participants had previously served as a juror in a legal case.

Procedure and materials

Participants self-selected to participate in the study as advertised on MTurk. The study was conducted online via Qualtrics. Participants were paid $1 to participate and a bonus of $2 if they correctly answered both attention check questions. This study was approved by the ethical review committee of [XX University, reference number 207_13_04_2019].

Power analysis

An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., Citation2009) for a hierarchical multiple regression analysis to test for the increase in explained variance (ΔR2) associated with the interaction term (as predicted in H3). The parameters were set as R2 = .022 to detect a small effect, α = .05, power = .80, and total number of predictors = 4. The minimum number of participants required was 351. However, because we expected the need to exclude participants for various reasons (e.g. failed attention checks), we planned to collect data from at least 400 participants to achieve sufficient statistical power.

Data were collected from 690 participants. Fifty-eight people did not complete the study, and 171 failed at least one attention check. We also excluded data from an additional 34 participants based on geo-coordinates falling outside the range for the United States, geo-coordinates that did not match the state indicated in the demographic data response, or if the geo-coordinate metadata were absent. Our remaining sample size was 427.

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained from participants, and they were asked to confirm that they met the eligibility criteria of being at least 18 years of age, proficient in reading and understanding English, and reside in the United States. Participants read a brief introduction about the study and received contact information of the first author in the event of any issues with the study. We used several controls for quality assurance. First, participants were not allowed to go back to a previous page once they moved on to the next one. Second, a timer was used to track how much time they spent on each page (participants were not aware that they were being timed). Finally, the ‘next’ button to move forward was also delayed on most pages (participants were informed of this) in an effort to discourage inattentive or random responding.

Before participants read anything about the case, they provided an estimate of how likely they think it is that a person who has been convicted for a sexual offense will commit another sexual offense (hereafter, general risk estimate), using a graphic sliding scale ranging from 0–100% in 1% increments. We chose to have participants complete the Need for Cognition Scale (NFCS) immediately thereafter, as a ‘distractor task’, to reduce the likelihood that they would conflate their own beliefs about sexual offending recidivism risk and the information contained in the case vignette.

Need for cognition scale

We used a slightly modified version of the short form Need for Cognition Scale (NFCS), which contains 18 items and is intended to assess an ‘individual’s tendency to engage in and enjoy effortful cognitive endeavors’ (Cacioppo et al., Citation1984, p. 306). The NFCS produces a need for cognition (NFC) score based on the respondent’s agreement with statements such as ‘I would prefer complex to simple problems’ and ‘I like tasks that require little thought once I’ve learned them.’ In the original version of the scale, item ratings are based on an 8-point Likert scale (-4 to +4) and nine of the items are reverse-scored (Cacioppo et al., Citation1984). Higher NFC scores are associated with a higher level of NFC, lower scores with a lower level of NFC. The NFCS demonstrates strong internal consistency (α = .90; Cacioppo et al., Citation1984), good test-retest reliability (Bertrams & Dickhäuser, Citation2010; Sadowski & Gulgoz, Citation1992; Verplanken, Citation1991), and additional studies have found support for divergent, discriminant, and predictive validity (see Cacioppo et al., Citation1996 for a review; Osberg, Citation1987; Stark et al., Citation1991).

In the current study, we asked participants to indicate the extent to which each NFCS item is typical of their own behavior on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = does not describe me, 2 = describes me slightly well, 3 = describes me moderately well, 4 = describes me very well, 5 = describes me extremely well), rather than an 8-point scale. For our analyses, we calculated a total score by adding all ratings together and subtracting a constant of 18, yielding a lowest possible score of 0 and a highest possible score of 72. Cronbach’s α in our sample was .94.

Case vignette

In this study, we defined risk-irrelevant contextual information as information that has not been shown to be empirically related to sexual reoffending risk (e.g. type of job, length of employment, others’ perceptions about his sociability, preferred leisure activities, and marital history). Participants were randomly assigned to read a case vignette containing positive (n = 213) or negative (n = 214) risk-irrelevant contextual information about an SVP respondent named John Smith (see Appendix A). The two case vignettes varied with respect to the previously mentioned risk-irrelevant contextual information. The effectiveness of the manipulation had been confirmed through participant ratings of Mr. Smith’s likability in a prior pilot study.

We did not provide any offense-related information before participants in the current study rated the likability of Mr. Smith because we expected the manipulation would have been less effective if participants were informed of the nature of his crime (i.e. a sexual offense) and prior non-sexual assault conviction. Therefore, after reading only the initial risk-irrelevant background information, participants were asked to rate Mr. Smith’s likability using three items: (a) likability, (b) friendliness, and (c) warmth. These three items were reproduced from the Reysen Likability Scale (Reysen, Citation2005). The Reysen Likability Scale is comprised of 11 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree). Lower ratings indicate the target is less likable, and higher ratings indicate the target is more likable. For this study, we used a 6-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree, 2 = mostly disagree, 3 = somewhat disagree, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = mostly agree, and 6 = completely agree) and removed the neutral option. Cronbach’s α for the original scale was .91 (Reysen, Citation2005). Cronbach’s α in this sample for the three items measured was .98. We calculated the average rating of the three likability factors to create a composite variable for statistical analysis of the manipulation’s effectiveness.

Participants then read the remainder of the case vignette describing the offense for which Mr. Smith was currently incarcerated (i.e. rape of a female acquaintance), his criminal history (one previous conviction for assault related to a bar fight when he was 18 years old), public opinion about the length of his prison sentence (5 years) for the sexual assault, and the victim’s opinion about the fairness of Mr. Smith’s prison sentence. The two criminal convictions are relevant to sexual recidivism risk and are accounted for by the Static-99R. Furthermore, we did not vary criminal history or Static-99R information between the positive and negative case vignette. However, the additional risk-irrelevant factors of the public’s and victim’s opinion of the length of the prison sentence differed between the positive and negative vignette conditions.

Participants were then instructed to imagine that they had been selected to be a juror in a civil commitment hearing. We provided background information about sex offender civil commitment, including the nature and purpose of civil commitment and the process generally followed to determine whether an offender should be subjected to civil commitment. To ensure attention and comprehension of the explanation of civil commitment, we used a multiple-choice attention check question of: ‘Confinement in a secure facility under SVP laws most often occurs,’ with response options of (a) while a person is serving their prison sentence; (b) before a person is sentenced to prison; or (c) after a person has served their prison sentence. Participants were also provided with information about the legal criteria that must be met for SVP civil commitment (see Appendix B).

Subsequently, participants were asked to provide an initial risk estimate (T1; 0–100% using a graphic sliding scale) and an initial disposition recommendation for Mr. Smith (1 = released to the community with no conditions, 2 = released to the community under supervision only, 3 = release to the community under supervision and mandated sex offender treatment, 4 = civil commitment) based on all the information they considered relevant. They were also informed that they would later receive additional information, after which they would be asked to provide a risk estimate and disposition recommendation once again.

Static-99R information

We operationalized risk-relevant information as Mr. Smith’s Static-99R (Helmus et al., Citation2012) results. The Static-99R comprises 10 risk factors that are empirically related to the likelihood of sexual offense recidivism (Phenix, Fernandez, et al., Citation2016). An evaluator codes each of the 10 factors and the resulting total score is associated with an estimated likelihood of reoffending based on previous recidivism rates of people convicted of a sexual offense who were released into the community (Knighton et al., Citation2014).

Similar to the approach taken by Varela and colleagues (Citation2014) in their study about risk communication formats, we informed participants about risk assessment tools and their use in estimating recidivism risk, provided information about the development of the Static-99R and how a risk score is calculated using the Static-99R (see Appendix C). We also provided participants with a list of the items contained in the Static-99R (see ). In contrast to Varela et al., we provided all participants with identical Static-99R results for Mr. Smith including his absolute score (2), risk category (medium risk), and the 5-year reoffending rate ranges associated with that risk category based on a routine sample (between 7.0% and 8.8%; Phenix, Fernandez, et al., Citation2016; see Appendix C). The format of the risk score information was provided exactly as outlined in the template recommended in the Static-99R and Static-2002R Evaluator’s Workbook (Phenix, Helmus, et al., Citation2016, p. 30). An attention check question followed in which participants typed in Mr. Smith’s Static-99R score.

Table 1. Risk factors of the static-99R.

Participants’ T2 risk estimates (0-100% on graphic sliding scale) and disposition recommendations (same options as presented at T1) were obtained after they had reviewed the Static-99R information. In addition, participants rated the importance of several factors to their estimate of the likelihood of the respondent’s sexual reoffending, including his: (a) relationships with others, (b) employment history, (c) criminal history, (d) impact of the crime on the victim, (e) length of prison sentence, and (f) Static-99R score, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important). Using the same scale, participants rated the importance of each of the aforementioned factors to their disposition recommendation, as well as one additional factor: the participant’s own estimate of the likelihood of the respondent committing another sexual offense. Participants’ disposition recommendations and importance ratings of the factors were analyzed as exploratory analyses and are reported in Supplemental Materials.

Demographic information

Participants were then asked if they had ever served on a jury in a legal case and to provide their age, gender, level of education, and state of residence. Finally, we asked participants to indicate whether we should use their data in our analyses (yes/no) and we provided them with debriefing information about the nature and purpose of the study and the research questions we hoped to answer.

Data analysis

We conducted confirmatory analyses in accordance with our preregistration. Where data transformations were necessary, we have noted these in the respective sections. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26. We used an alpha level of .05 for all statistical tests. Assessments of effect sizes as small, medium, or large rest on the conventions proposed by Cohen (Citation1988).

Results

Manipulation check

We conducted an independent samples Welch’s t-test to compare the likability ratings between the positive and negative contextual information conditions. On average, participants in the positive condition rated the respondent as significantly more likable (M = 5.06, SD = 0.68) than did participants in the negative condition (M = 2.22, SD = 1.02), t(370.85) = −33.96, p < .001, Hedges’ g = 3.28, 95% CI [2.99, 3.57]. This finding confirms that before reading about the crime information, there was a significant difference between the groups in the perceived likability of the SVP respondent, suggesting that the contextual information manipulation was effective.

The effect of contextual information on T1 risk estimates

Overall, participants’ general risk estimates (M = 66.3%, SD = 20.0) were much higher than observed sexual recidivism rates of 5-15% (Alper & Durose, Citation2019; Hanson et al., Citation2014; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2005, Citation2009; Harris & Hanson, Citation2004; Helmus et al., Citation2012; Phenix, Helmus, et al., Citation2016). An independent samples t-test confirmed that there was no significant difference between conditions with respect to participants’ general sexual recidivism risk estimates, t(425) = −1.43, p = .154, Hedges’ g = 0.14, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.33]. Nevertheless, to isolate the effects of the contextual information, we controlled for participants’ general risk estimates in the analysis of T1 risk estimates.

A one-way ANCOVA was conducted on participants’ ratings of the respondent’s recidivism risk at T1, with contextual information (positive vs. negative) as the independent variable and participants’ general estimates of sexual recidivism risk as covariate.Footnote2 There was a significant, medium-sized effect of contextual information, F(1, 424) = 39.42, p < .001, = .085, 90% CI [.047,.130]. In support of H1, participants in the positive contextual information condition rated the recidivism risk as significantly lower (M = 40.9, SD = 25.3) than did participants in the negative contextual information condition (M = 55.1, SD = 22.6). Moreover, the analysis indicated that participants’ general recidivism risk estimates accounted for a large and significant portion of the variance in T1 risk estimates, F(1, 424) = 161.1, p < .001,

= .275, 90% CI [.217,.330]. As expected, participants who reported higher general risk estimates reported higher case-specific risk estimates at T1, bivariate r = .52, p < .001.

The effects of contextual information and NFC on T2 risk estimates

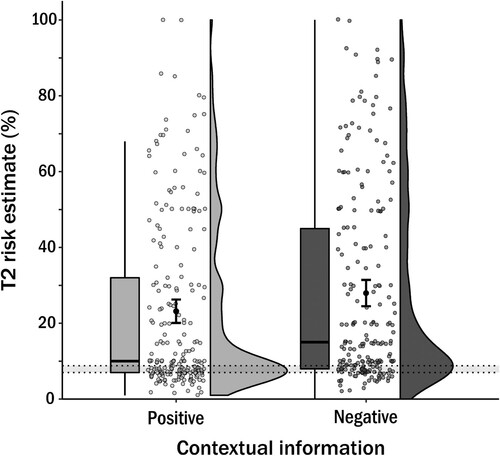

At T2, participants’ mean risk estimate (Mraw = 25.6%, SD = 24.4) was substantially decreased from T1, but nevertheless exceeded that indicated by the Static-99R (i.e. 7.0–8.8%). Additional exploratory analyses of the T2 ratings are presented in the Supplemental Materials. To test the effects of the positive and negative contextual information, and whether NFC moderates the relationship between the type of risk-irrelevant contextual information (positive or negative) and T2 risk estimates, we conducted a hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis with participants’ T2 risk estimates as the outcome variable. A visual inspection of the data revealed that participants’ risk estimates were severely positively skewed (see ). Moreover, a regression analysis using the raw values resulted in non-normally distributed residuals and considerable heteroscedasticity. Hence, we added a constant of one to participants’ T2 risk estimates (because one participant estimated T2 risk as 0%) and performed a log transformation before conducting the regression analysis.Footnote3

Figure 1. Raincloud Plot and Boxplot of T2 Risk Estimate Distribution. Note. N = 427. Raincloud plot and boxplot showing the positively skewed distribution of participants’ risk estimates at T2. The horizontal shaded band represents the 5-year sexual reoffending rate indicated by the Static-99R information (7.0%–8.8%). The black dots with error bars represent group means and 95% confidence intervals. The boxplot whiskers span 1.5 times the interquartile range (trimmed at 0% and 100%).

In Step 1, contextual information (0 = positive, 1 = negative), general risk estimates, and participants’ NFC total scores were entered as predictor variables.Footnote4 In Step 2, the interaction term between contextual information and NFC scores was entered. Participants’ NFC scores were mean-centered for the regression analysis to avoid multicollinearity and to ease the interpretation of the interaction regression coefficient (Jaccard & Turrisi, Citation2003). Regression statistics are reported in .

Table 2. Results of hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis predicting participants’ T2 risk estimates.

The predictors entered at Step 1 contributed significantly to the regression model, F(3, 422) = 18.75, p < .001, and explained 11.7% of the variation in T2 risk estimates. We did not find support for H2, as contextual information was not a significant predictor of T2 risk estimates, although participants in the negative contextual information condition (Mraw = 27.9, SD = 25.8) reported higher risk estimates than did participants in the positive contextual information condition (Mraw = 23.2, SD = 22.9). This result indicates that participants were not significantly influenced by the contextual information after reviewing the risk-relevant Static-99R information. Moreover, although participants’ general risk estimates were significantly associated with their T2 risk estimates, NFC scores were not. Adding the interaction term of contextual information and NFC at Step 2 did not significantly improve the model, F(4, 421) = 0.002, p = .969. Thus, the analysis failed to support H3.

Exploratory analysis

Our preregistered exclusion criterion, according to which we excluded participants who failed one or both attention checks, resulted in the exclusion of 171 participants (24.8% of the 690 participants who began the study). We suspected that this exclusion criterion may have inadvertently led to participants who were lower in NFC being excluded from analysis. This speculation was confirmed through a Welch’s t-test, which showed that excluded participants had a significantly lower NFC total score (M = 40.3, SD = 12.9) than non-excluded participants (M = 44.7, SD = 16.2), t(389.95) = 3.53, p < .001, Hedges’ g = 0.29, 95% CI [0.11, 0.47]. Therefore, we repeated the hypothesis testing for H2 and H3 to assess whether including participants with a failed attention check would affect the results.

H2 and H3 Analysis including participants who failed one or both attention checks

Similar to the main analysis, at T2, participants’ mean risk estimate (Mraw = 31.7%, SD = 28.0) was substantially decreased from T1, and exceeded that indicated by the Static-99R (i.e. 7.0–8.8%). To test the effects of the positive and negative contextual information, and whether NFC moderates the relationship between the type of risk-irrelevant contextual information (positive or negative) and T2 risk estimates, we conducted a hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis with all participants’ T2 risk estimates as the outcome variable (adding a constant of one and log-transforming the T2 risk estimates to correct for skewed data and non-normally distributed residuals and heteroscedasticity in the raw values before conducting the regression analysis).Footnote5

In Step 1, contextual information (0 = positive, 1 = negative), general risk estimates, and participants’ NFC total scores were entered as predictor variables. In Step 2, the interaction term between contextual information and NFC scores was entered. Participants’ NFC scores were mean-centered for Step 2 of the regression analysis to avoid multicollinearity and to ease the interpretation of the interaction regression coefficient (Jaccard & Turrisi, Citation2003). Regression statistics are reported in .

Table 3. Results of hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis predicting participants’ T2 RISK ESTIMAtes (no exclusions for failed attention checks).

The predictors entered at Step 1 contributed significantly to the regression model, F(3, 593) = 17.011, p < .001, and explained 10.3% of the variation in T2 risk estimates. Again, we did not find support for H2, as contextual information was not a significant predictor of T2 risk estimates, although participants in the negative contextual information condition (Mraw = 33.5, SD = 28.4) reported higher risk estimates than did participants in the positive contextual information condition (Mraw = 29.9, SD = 27.4). This result indicates that participants were not significantly influenced by the contextual information after reviewing the risk-relevant Static-99R information. Similar to the findings in the previous analysis, participants’ general risk estimates were significantly associated with their T2 risk estimates. However, in contrast to the prior analysis, participants’ NFC scores did have a significant main effect on their T2 risk estimates. The negative coefficient indicates NFC scores were negatively associated with T2 risk estimates, such that as NFC scores decreased, risk estimates increased. Nevertheless, similar to the previous analysis, adding the interaction term of contextual information and NFC at Step 2 did not significantly improve the model, F(4, 594) = 0.011, p = .916. Thus, reanalysis of the data including participants who failed one or more attention checks again failed to support H2 and H3.

Discussion

Our primary aims in this study were to examine whether there was a biasing effect of risk-irrelevant contextual information on jurors’ perceptions of SVP respondent sexual recidivism risk, and if so, whether presenting risk-relevant information (i.e. Static-99R actuarial risk estimate) could eliminate the bias, and whether mock jurors’ level of NFC moderated the effects of risk-relevant information on biasing risk-irrelevant contextual information.

Effects of contextual information on T1 Risk estimates

We first hypothesized that positive or negative risk-irrelevant contextual information would have a significant effect on mock jurors’ estimates of the likelihood that the respondent would sexually reoffend. The results supported our hypothesis that participants who read negative risk-irrelevant contextual information about the respondent rated his likelihood of reoffending at T1 significantly higher than participants in the positive condition. This finding demonstrates that bias created by the perceived social (un)attractiveness of the respondent potentially affects jurors’ perceptions of reoffending risk in an SVP context. This finding lends support to a suspected halo effect in operation in jurors’ estimates of sexual recidivism risk.

However, we also note that participants’ general sexual recidivism risk estimates accounted for a significant portion of the T1 risk estimates, lending support to previous findings that indicate that public misconceptions about sexual recidivism rates among sex offenders contribute to SVP decision-making (Scurich & Krauss, Citation2014). In fact, the mean general sexual recidivism risk estimate among our participants far exceeded observed sexual recidivism rates (e.g. Alper & Durose, Citation2019; Hanson et al., Citation2014; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2005; Helmus et al., Citation2012; Langan et al., Citation2003). For example, Langan et al. (Citation2003) reported a sexual recidivism rate of 5.3% three years post-release based on arrest data for 9,691 male sex offenders released from 15 state prisons in 1994. In a retrospective study nine years post-release, Alper and Durose (Citation2019) reported an observed sexual recidivism rate of 8% among a sample of 20,195 subjects in 30 states who had been released after serving a prison sentence for rape/sexual assault. Previous meta-analyses reported observed sexual recidivism rates ranging from 7% to 15% with an average follow-up period of five to six years (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2005; Helmus et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, several studies indicate that longer periods of offense-free time in the community are associated with decreases in observed sexual recidivism rates (Harris et al., Citation2003), even among so-called high-risk sex offenders (Hanson et al., Citation2014).

The finding that general beliefs about the rate of sexual recidivism among people convicted of a sexual offense has a significant effect on perceptions of recidivism risk also extends to judges in both adversarial and inquisitorial settings. Judges appear to hold some of the same attitudes towards people convicted of a sexual offense as the general public (Nhan et al., Citation2012). In fact, in McKune v. Lile (Citation2002), Justice Kennedy asserted, with paltry and questionable evidence (Ellman & Ellman, Citation2015), that the risk of sexual recidivism is ‘frightening and high’ (p. 34), a phrase which has been cited in at least 100 subsequent lower court decisions (Liptak, Citation2017).

Mitigating effects of actuarial risk estimate on T2 risk estimates

We examined whether the biasing effect of risk-irrelevant contextual information predicted mock jurors’ estimates of reoffending risk after they reviewed the risk-relevant Static-99R information (T2). The majority (63%) of our sample provided a case-specific sexual recidivism risk estimate that exceeded the score-wise risk estimate indicated by the Static-99R. This finding is in line with previous research showing that people tend to overestimate recidivism risk, even when presented with a likelihood percentage (Batastini, Hoeffner, et al., Citation2019; Varela et al., Citation2014).

Contrary to our expectations, the risk-irrelevant contextual information did not significantly predict mock jurors’ estimates of sexual recidivism risk at T2. The hypothesis that the risk-irrelevant characteristics of the SVP respondent would influence mock jurors’ estimates of sexual recidivism risk had an intuitive appeal based on research indicating that certain characteristics such as physical (Abel & Watters, Citation2005) and social attractiveness (Alicke & Zell, Citation2009) affect attributions of guilt and punishment decisions in some criminal contexts. Moreover, previous research has suggested that jurors give relatively little weight to expert testimony based on structured risk assessment instruments (Boccaccini et al., Citation2013, Citation2014; Guy & Edens, Citation2003; Krauss & Sales, Citation2001). In other words, we did not expect that the Static-99R report would successfully mitigate the biasing effects of the risk-irrelevant information. However, we are unaware of any previous study that has isolated the effects of risk-irrelevant information and Static-99R results in the manner we did (i.e. presenting only the Static-99R report) on mock SVP jurors’ estimates of sexual recidivism risk or civil commitment decisions.

Not only did we eliminate potential effects of the likability or credibility of an expert, we also communicated the risk estimate to mock jurors in several formats. In particular, previous violence risk assessment research suggests that when jurors are presented with recidivism rates (as compared to categorical estimates), they tend to render significantly lower risk estimates (e.g. Batastini, Hoeffner, et al., Citation2019; Batastini, Vitacco, et al., Citation2019), which may account for the substantial shift in recidivism risk estimates toward that indicated by the Static-99R in our study. Hence, although the finding of the effectiveness of the Static-99R information on mitigating bias should be considered tentative, we believe that the null effect of the risk-irrelevant information at T2 on mock jurors’ estimates of sexual recidivism risk suggest a potential debiasing effect of the actuarial risk estimate. This is a remarkable finding, because it runs counter to previous studies that suggest oral or written expert testimony regarding recidivism risk may increases jurors’ perceptions of sexual recidivism risk (e.g. Krauss et al., Citation2012).

Also contrary to previous research, indicating that participants greatly overestimate sexual recidivism risk regardless of the communication format (Varela et al., Citation2014), our findings indicate a substantial reduction in overall recidivism risk estimates after reviewing the Static-99R information. However, despite the fact that there are some similarities between our study and that of Varela et al. (Citation2014), the current study is distinguishable for several reasons. First, our participants provided a numerical risk estimate, whereas in the Varela et al. study, the participants rated recidivism risk based on Likert scale ratings of (1) the likelihood of reoffense; (2) dangerousness to the community; and (3) support for strict supervision strategies. Based on a composite rating of the first two factors, Varela et al. reported that 95% of their participants indicated the offender was likely to commit a new sexual offense within the next five years. Second, the individual presented in the Varela et al. case vignette had been convicted of two previous rapes, whereas the individual portrayed in our study had been convicted for one previous sexual assault. Moreover, participants in the Varela et al. study were exposed to only one risk communication format, whereas our participants read a Static-99R report based on the template provided in the Static-99R Evaluator Workbook (Phenix, Helmus, et al., Citation2016). In fact, previous researchers have suggested that presenting risk estimates through combined methods (e.g. categorical and probabilistic) may improve decision-makers’ understanding of a risk estimate (e.g. Hilton et al., Citation2015).

Relatedly, Scurich and Krauss (Citation2014) conducted an experimental study in which their participants’ sexual recidivism risk estimates averaged nearly 74%, substantially higher than T2 risk estimates of 25.6% in the current study. Scurich and Krauss sought to determine whether participants would vote for civil commitment regardless of whether all four legal criteria were met. In their study, participants who received expert testimony in the form of a categorical risk estimate (indicating moderate risk) based on the Static-99R did not provide recidivism risk estimates that differed significantly from participants who received no expert testimony about sexual recidivism risk. However, the difference in the risk estimates in the Scurich and Krauss study and the current study may be explained by several factors. First, Scurich and Krauss presented only a categorical risk estimate communicated through expert testimony. In addition, participants read expert testimony about recidivism risk only after they were exposed to other risk-relevant information, such as the SVP respondent’s previous convictions and a clinical diagnosis of pedophilia. In combination, the presentation of a categorical risk estimate and other risk-relevant information in the Scurich and Krauss study may explain the large difference between the average risk estimate in their study and the average risk estimates at T2 in our study.

In conclusion, although the significant effect of the Static-99R on sexual recidivism risk estimates and the relatively low risk estimates at T2 in the current study appear to contradict previous research, we have discussed several possible explanations for these differences. These differences include how risk was communicated in most previous studies (i.e. through expert testimony and/or by presenting the risk estimate in a single format) and the presence of other risk-relevant factors that make it difficult to discern what factors were influencing jurors’ perceptions of sexual recidivism risk. The current study design enabled us to directly examine (1) whether mock jurors’ estimates of sexual recidivism risk are affected by risk-irrelevant information and (2) whether providing mock jurors with an actuarial risk estimate in various formats (i.e. categorical, relative risk, and probabilistic risk), free of the influence of potential confounding factors related to expert testimony, was effective in mitigating the influence of bias created by risk-irrelevant characteristics of the SVP respondent.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to directly examine whether an actuarial risk estimate can mitigate the effects of contextual information bias among legal decision-makers. Overall, we believe that failing to find support for our hypothesis that a Static-99R risk estimate would be ineffective in mitigating the effects of contextual information bias (H2) is encouraging. Although future researchers should attempt to examine this question, we expect that these findings would also extend to judges. Previous research indicates that experts and judges are prone to the same cognitive biases as laypeople (e.g. Guthrie et al., Citation2001; Liu & Li, Citation2019; Rassin, Citation2020). Therefore, if an actuarial risk estimate is effective in mitigating the effects of bias among mock jurors, it is reasonable to expect the same would hold true for judges.

Mock Jurors’ Level of Need for Cognition and Decision-Making

We did not find support for the hypothesis that mock jurors’ NFC moderates the influence of risk-relevant and risk-irrelevant information on estimates of the SVP respondent’s recidivism risk. This null finding suggests that varying levels of NFC may not explain mock jurors’ ability or willingness to adjust their perceptions of the respondent’s recidivism risk in light of actuarial information. It should be noted, however, that NFC and education level appear to be strongly correlated (McCabe et al., Citation2010). Our sample was fairly well-educated, with over 50% possessing at least a bachelor’s degree. In line with this, the median NFC score among our sample was 47, where the midpoint of the scale was 36. Research suggests that people who have higher levels of NFC may be more inclined to adjust their initial judgments in light of new information (D’Agostino & Fincher-Kiefer, Citation1992; Gilbert et al., Citation1988; Martin et al., Citation1990). Therefore, we could not rule out the possibility that the Static-99R information had a substantial effect in our sample due to participants’ relatively high level of NFC.

Because of the significant difference in NFC scores between participants who were excluded for a failed attention check and those who were not, we conducted an exploratory analysis to examine the possibility of a moderating effect of NFC. Although we again found no support for a moderating effect (H3), we did find a significant main effect of level of NFC on mock jurors’ risk estimates at T2. While conclusions about this finding are tentative, we note that it is in line with previous research suggesting that those who are lower in NFC may be more prone to heuristic thinking (e.g. Lieberman, Citation2002; Lieberman et al., Citation2007) and less influenced by testimony based on ARAIs than on clinical judgment (Krauss et al., Citation2004). The significant main effect of NFC in the current study further suggests that individual information processing differences among jurors affect their motivation to effectively discriminate between information that is risk-irrelevant and that which is risk-relevant and thereby legally relevant. Additional research on the effect of juror levels of NFC on their capacity to render legally justifiable decisions could have significant implications for juror screening processes.

Limitations

We note a number of limitations to this study, specifically related to its experimental design and the realities in SVP hearings. First, we presented very limited background information about the SVP respondent. In actual cases, jurors are likely to learn much more about the respondent as they must consider not only the respondent’s risk of sexual recidivism. For example, jurors are likely to hear expert testimony about mental health diagnoses, because the presence of a mental abnormality is one of the legal criteria that must be met to justify civil commitment. We did not present any diagnosis to our participants.

Second, the SVP respondent in the case vignette had been convicted of one sexual offense and one previous non-sexual offense. This type of criminal history may not be typical of the offending history of actual SVP respondents, although analysis of actual SVP cases indicates prior criminal history can vary widely (e.g. Lu et al., Citation2015). Third, although not measured by the Static-99R, some of the characteristics we labelled as ‘risk-irrelevant’ in this study may be relevant in the context of a forensic sexual risk evaluation. For example, the type of employment a person has may be an indicator of their intelligence level and poor relationships with others may be indicative of psychopathy or a personality disorder, which are factors that may have clinical significance for sexual recidivism risk among certain types of offenders (see, for example, Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2005; Hawes et al., Citation2013; Hildebrand et al., Citation2004; Nijman et al., Citation2009; Porter et al., Citation2009) Yet, as presented in our case vignette and without additional context, concluding that there is evidence of low intelligence or a personality disorder would not be justified. In fact, in our study, we found that mock jurors’ evaluations of an SVP respondent’s sexual recidivism risk appear to be closely tied to their global evaluation of factors affecting the likability of the SVP respondent, such as would be expected by the operation of the halo effect (Nisbett & Wilson, Citation1977). Nevertheless, future research might employ a ‘purer’ test of factors that have no potential significance for jurors’ sexual recidivism risk estimates (for example, physical attractiveness of the SVP respondent).

We also note that there are a number of limitations inherent to the mock jury paradigm. For example, decisions are rendered without jury deliberation, and deliberation has been shown to influence jury decision-making (Lynch & Haney, Citation2009). Hence, jury dynamics and the relative influence of risk-irrelevant contextual information and actuarial risk estimates might be a fruitful area of further study. Finally, we utilized MTurk workers as mock jurors in this study. There may be some differences between MTurk workers and a typical SVP juror. For example, there are a number of criteria that may prevent someone from serving on a jury that are not relevant in the context of an online study (e.g. a criminal record). There may also be differences between MTurk workers and ‘typical’ jurors in SVP cases in terms of education level, political values, and age (Paolacci & Chandler, Citation2014). Yet, MTurk respondents tend to be diverse in terms of socioeconomic status and ethnicity (Casler et al., Citation2013), which is a benefit for studying psychological phenomena and individual differences. We also note that nearly 17% of our sample had previously served as a juror.

Conclusion

The current study has shown the potential for jurors to be biased by risk-irrelevant factors in their perceptions of an SVP respondent’s sexual recidivism risk. Misjudgments of sexual recidivism risk are likely to undermine the intent of the legal statute that civil commitment be imposed only on offenders at highest risk of sexual reoffending (Carlsmith et al., Citation2007; Knighton et al., Citation2014; Krauss & Scurich, Citation2014; Scurich & Krauss, Citation2014; Sreenivasan et al., Citation2003). The risk estimate derived from an ARAI appears to be the most accurate (Ægisdóttir et al., Citation2006; Grove & Meehl, Citation1996; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2009) and most relied upon factor among evaluators who render an expert opinion in SVP cases (Chevalier et al., Citation2015). We have provided preliminary evidence suggesting that permitting jurors to review the actuarial risk estimate information directly in writing, may encourage them to rely more on scientifically-based information in their judgment of the respondent’s sexual recidivism risk, thus limiting the influence of risk-irrelevant contextual information. Nevertheless, the finding from the reported exploratory analysis related to juror level of need for cognition also suggests that how jurors process information may have a significant effect on their capacity to integrate relevant information and render a legally justified verdict in an SVP civil commitment case.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (88.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Most SVP/SDP statutes also permit SVP commitment proceedings to be initiated based on a crime(s) for which the respondent was found not guilty by reason of insanity or incompetent to stand trial (Fanniff et al., Citation2010; Phenix & Jackson, Citation2015). In addition, most jurisdictions also permit the application of SVP statutes to crimes not statutorily defined as sexual offenses, but alleged to have been ‘sexually motivated’ (National District Attorneys Association, Citation2012).

2 To address concerns related to the exclusion of participants who failed one or both of the attention checks, we reran the analyses for H1 for the entire sample that completed the study and were not excluded for geocoordinate issues and we found no significant change. Results are reported in Supplemental Materials.

3 The heavy skew in the data was unanticipated and the log-transformation was not part of the preregistered analysis plan. Moreover, we are aware of the problems that can be introduced into hypothesis testing when adding a constant to the original values and/or using a log-transformation of the data (Feng et al., Citation2014). Therefore, to exclude the possibility that adding a constant of one and log-transforming the T2 risk estimates substantially altered our conclusions based on the regression analysis, we ran a moderation analysis on the raw data to compute bootstrapped confidence intervals using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Hayes, Citation2018). This analysis did not change the nature of the results. Full details of the analysis can be found in the Supplemental Materials in Table S1.

4 In our preregistered analysis plan, we erroneously stated that the T1 risk estimates would be controlled for in the analysis. However, because the T1 estimates were measured after (and were influenced by) the experimental manipulation, it is not appropriate as a covariate. Instead, to control for preexisting differences in risk perception, we entered the general risk estimate as covariate.

5 Related to the concerns about log-transforming the data expressed in Footnote 3, we again used the PROCESS v. 3.5 macro (Hayes, Citation2018) to obtain the bootstrapped confidence intervals for the exploratory analysis for H2 and H3 that we conducted on the entire sample that completed the study and were not excluded due to geocoordinate issues. Results are reported in Table S2 of the Supplemental Materials.

References

- Abel, M. H., & Watters, H. (2005). Attributions of guilt and punishment as functions of physical attractiveness and smiling. The Journal of Social Psychology, 145(6), 687–702. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.145.6.687-703

- Ægisdóttir, S., White, M. J., Spengler, P. M., Maugherman, A. S., Anderson, L. A., Cook, R. S., Nichols, C. N., Lampropoulos, G. K., Walker, B. S., Cohen, G., & Rush, J. D. (2006). The meta-analysis of clinical judgment project: Fifty-six years of accumulated research on clinical versus statistical prediction. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(3), 341–382. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000005285875

- Alicke, M. D., & Zell, E. (2009). Social attractiveness and blame. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(9), 2089–2105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00517.x

- Alper, M., & Durose, M. R. (2019). Recidivism of sex offenders released from state prison: A 9-year follow-up (2005-14) (NCJ 251773). Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rsorsp9yfu0514.pdf

- Barbaree, H. E., Seto, M. C., Langton, C. M., & Peacock, E. J. (2001). Evaluating the predictive accuracy of six risk assessment instruments for adult sex offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 28(4), 490–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/009385480102800406

- Batastini, A. B., Hoeffner, C. E., Vitacco, M. J., Morgan, R. D., Coaker, L. C., & Lester, M. E. (2019a). Does the format of the message affect what is heard? A two-part study on the communication of violence risk assessment data. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 19(1), 44–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2018.1538474

- Batastini, A. B., Vitacco, M. J., Coaker, L. C., & Lester, M. E. (2019b). Communicating violence risk during testimony: Do different formats lead to different perceptions among jurors? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 25(2), 92–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000196

- Bertrams, A., & Dickhäuser, O. (2010). University and school students’ motivation for effortful thinking: Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the German Need for Cognition scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(4), 263–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000035

- Boccaccini, M. T., Murrie, D. C., & Turner, D. B. (2014). Jurors’ views on the value and objectivity of mental health experts testifying in sexually violent predator trials. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 32(4), 483–495. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2129

- Boccaccini, M. T., Rice, A. K., Helmus, L. M., Murrie, D. C., & Harris, P. B. (2017). Field validity of Static-99/R scores in a statewide sample of 34,687 convicted sexual offenders. Psychological Assessment, 29(6), 611–623. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000377

- Boccaccini, M. T., Turner, D. B., Murrie, D. C., Henderson, C. E., & Chevalier, C. (2013). Do scores from risk measures matter to jurors? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19(2), 259–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031354

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.116

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., Feinstein, J. A., & Jarvis, W. B. G. (1996). Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in need for cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 197–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.197

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Kao, C. F. (1984). The efficient assessment of need for cognition. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(3), 306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_13

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Morris, K. J. (1983). Effects of need for cognition on message evaluation, recall, and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 805–818. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.805

- Carlsmith, K. M., Monahan, J., & Evans, A. (2007). The function of punishment in the “civil” commitment of sexually violent predators. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 25(4), 437–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.761

- Casler, K., Bickel, L., & Hackett, E. (2013). Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, social media, and face-to-face behavioral testing. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2156–2160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.009

- Chevalier, C. S., Boccaccini, M. T., Murrie, D. C., & Varela, J. G. (2015). Static-99R reporting practices in sexually violent predator cases: Does norm selection reflect adversarial allegiance? Law and Human Behavior, 39(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000114

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates.

- D’Agostino, P. R., & Fincher-Kiefer, R. (1992). Need for cognition and the correspondence bias. Social Cognition, 10(2), 151–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1992.10.2.151

- Denes-Raj, V., & Epstein, S. (1994). Conflict between intuitive and rational processing: When people behave against their better judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(5), 819–829. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.819

- Edens, J. F., Smith, S. T., Magyar, M. S., Mullen, K., Pitta, A., & Petrila, J. (2012). “Hired guns,” “charlatans,” and their “voodoo psychobabble”: Case law references to various forms of perceived bias among mental health expert witnesses. Psychological Services, 9(3), 259–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028264

- Ellman, I. M., & Ellman, T. (2015). “Frightening and high”: The supreme court’s crucial mistake about sex crime statistics. Constitutional Commentary, 30(3), 495–508. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2616429

- Epstein, S. (1993). Implications of cognitive-experiential self-theory for personality and developmental psychology. In D. C. Funder, R. D. Parke, C. Tomlinson-Keasey, & K. Widaman (Eds.), Studying lives through time: Personality and development (pp. 399–438). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/10127-033

- Fanniff, A. M., Otto, R. K., & Petrila, J. (2010). Competence to proceed in SVP commitment hearings: Irrelevant or fundamental due process right? Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 28(5), 647–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.957

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Feng, C., Wang, H., Lu, N., Chen, T., He, H., Lu, Y., & Tu, X. M. (2014). Log-transformation and its implications for data analysis. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 26(2), 105–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2014.02.009

- Gilbert, D. T., Pelham, B. W., & Krull, D. S. (1988). On cognitive busyness: When person perceivers meet persons perceived. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 733–740. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.733

- Grove, W. M., & Meehl, P. E. (1996). Comparative efficiency of informal (subjective, impressionistic) and formal (mechanical, algorithmic) prediction procedures: The clinical–statistical controversy. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 2(2), 293–323. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8971.2.2.293

- Gunnell, J. J., & Ceci, S. J. (2010). When emotionality trumps reason: A study of individual processing style and juror bias. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 28(6), 850–877. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.939

- Guthrie, C., Rachlinski, J. J., & Wistrich, A. J. (2001). Inside the judicial mind. Cornell Law Review, 86(4), 777–830. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.257634

- Guy, L. S., & Edens, J. F. (2003). Juror decision-making in a mock sexually violent predator trial: Gender differences in the impact of divergent types of expert testimony. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 21(2), 215–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.529

- Hanson, R. K., Harris, A. J. R., Helmus, L., & Thornton, D. (2014). High-risk sex offenders may not be high risk forever. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(15), 2792–2813. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514526062

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2005). The characteristics of persistent sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of recidivism studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1154–1163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1154

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2009). The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of 118 prediction studies. Psychological Assessment, 21(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014421

- Hanson, R. K., & Thornton, D. (1999). Static 99: Improving actuarial risk assessments for sex offenders (No. 1999–02). Solicitor General Canada.

- Harris, A. J., & Hanson, R. K. (2004). Sex offender recidivism: A simple question (No. 2004–03; p. 29). Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada.

- Harris, A. J., Phenix, A., Hanson, R. K., & Thornton, D. (2003). STATIC-99 Coding Rules Revised—2003. http://www.static99.org/pdfdocs/static-99-coding-rules_e.pdf

- Haugtvedt, C. P., Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1992). Need for cognition and advertising: Understanding the role of personality variables in consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 1(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(08)80038-1