ABSTRACT

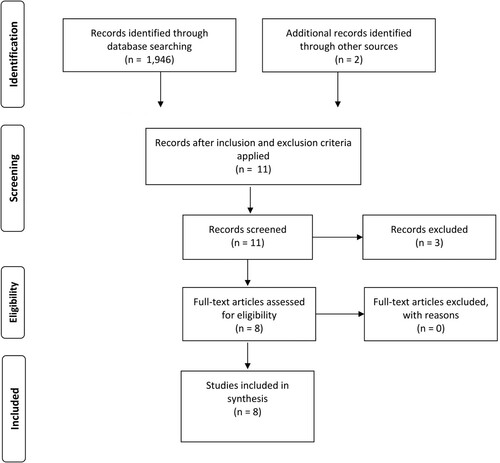

Adult female sexual assault victims who appear emotional are rated as more credible by jurors, which has been termed the emotional victim effect. Two explanations of this effect have been proposed: The expectancy violation theory and the compassionate-affective account. To date, the emotional victim effect in child victims, or the application of these theories to child victims, has not been reviewed. We conducted a systematic review to examine how child victims’ emotional presentation influences mock juror credibility judgements. We searched five databases acquiring 1,946 articles. A further two articles were included after initial screening. Following quality assessment, eight studies were identified as suitable for inclusion in the current review, with a total of 2,148 participants. These studies all showed that ‘sad’ emotional presentation of a child victim increased subsequent mock juror credibility ratings. Type of emotion, proportionality of the emotional response, level of empathy, gender of the participants, and age of the victims, also influenced credibility judgements made by jurors. The review illustrates evidence of the emotional victim effect within the child victim population, discusses possible explanations of the effect, moderating factors, and highlights the important implications of these findings at multiple stages of the Criminal Justice System.

Introduction

The admission of testimony from victims is routine in the commission of criminal trials. Prosecutors are reliant on credible victim testimony for successful prosecution and it is the contrary role of the defence to highlight any inconsistencies in the victim’s account. There is no clear shared definition for the concept of credibility because across literatures and disciplines, and even within legal guidance, the term is used interchangeably with other terms such as ‘reliability’, ‘trustworthiness’, and ‘believability’. During a criminal trial, jurors are tasked with determining whose story is more credible; the victim’s or the defendant’s (R v B, Citation2010). Jurors are members of the public chosen at random to administer judgement on guilt and possess no formal training to complete this task. Research shows that juror judgements about adult victim credibility are reliant on social norms, stereotypes, and beliefs concerning the victim’s demeanour, including the victim’s emotional presentation (e.g. sadness, anger, neutral; Lens et al., Citation2014). The picture, however, is less clear regarding juror judgements of child victim credibility. Children’s testimony is usually given following an experience of maltreatment or abuse. As a result, many children globally come into contact with legal systems every year (Malloy et al., Citation2011). It is imperative, for the balanced administration of justice, to understand juror decision-making in cases involving children. Here, we conducted a systematic literature review to examine how the emotional demeanour of child victims can influence juror decision-making and judgements about child victim credibility.

Adult victims

There is a wealth of empirical research regarding the impact of a victim’s demeanour on judgments of credibility in relation to adult victim’s testimony. Distressed adult victims are more likely to be judged as credible compared to those who appear neutral, a finding termed the emotional victim effect (Ask & Landstrom, Citation2010; Bollingmo et al., Citation2009; Dahl et al., Citation2007; Kaufmann et al., Citation2002; Klippenstine & Schuller, Citation2012; Lens et al., Citation2014; Mulder & Winiel, Citation1996; Winkel & Koppelaar, Citation1991). A meta-analysis examining the emotional victim effect in female adult victims of sexual assault concluded that a distressed compared to a neutral demeanour increases perceived credibility. The effect size was estimated to be small to moderate (Nitschke et al., Citation2019). As stated by Kaufmann et al. (Citation2002) ‘It is not what you say that determines credibility, but how you say it’ (p.30). Further research has examined the possible influencing factors of this effect. For example, the meta-analysis by Nitschke et al. (Citation2019) considered only adult female sexual assault complainants, but a small amount of other research has not always found the same result with male victims (e.g. Landstrom et al., Citation2015; Rose et al., Citation2006) or differing crime types (Bosma et al., Citation2018). Moreover, research shows that female observers (Lanström et al., Citation2015) and social workers (Mulder & Winiel, Citation1996) are more likely to rate victims as credible. Differing levels of victim distress (Kaufmann et al., Citation2002), consistency of emotional presentation (Klippenstine & Schuller, Citation2012), and the proportionality of emotional presentation (Rose et al., Citation2006) have also been shown to influence subsequent credibility ratings.

Two theories have been proposed to explain the emotional victim effect: one cognitive and one affective. First, expectancy violation theory posits that an observer’s credibility ratings about a victim are influenced by the non-verbal emotional presentation of the victim and bias is caused by the observer’s preconceived belief of how the victim should present. Behavioural cues which are congruent with the observer’s expectations are often attributed to the external event (e.g. the crime), whereas cues which are incongruent violate the expectations of the observer and therefore the cues are attributed to internal factors (e.g. dishonesty; Hackett et al., Citation2008). Therefore, if a victim’s emotional presentation is congruent with the observer’s beliefs regarding the impact of the crime, the victim is judged as more credible than a victim who presents in an incongruent manner (Klippenstine & Schuller, Citation2012). Given that often the pre-conceived belief is that victims should be sad or distressed, victims who present in a neutral or controlled manner are often considered to be lying and somehow responsible (Baldry et al., Citation1997; Winkel & Koppelaar, Citation1991). The process where an observer attributes a viewed behaviour to a stable internal process in the victim (dishonesty) rather than as a consequence of the circumstances the victim finds themselves in is a form of cognitive bias known as fundamental attribution error (Ross, Citation2018). The second account of the emotional victim effect suggests that a victim who presents emotionally is more likely to be believed than a victim who presents neutrally, because a stronger benevolent response is evoked in the observer by the emotional victim, called a compassionate affective response (Ask & Landstrom, Citation2010).

Why is it problematic that jurors’ assessments are influenced by victims’ emotion?

A victim’s emotional presentation is not a reliable indicator of their accuracy or truthfulness. When observers rely on the emotional presentation of the victim, they are using heuristic processing instead of systematic processing (Hackett et al., Citation2008). Heuristic processing occurs when individuals use behavioural cues to make judgements and decisions with minimal cognitive effort, instead of carefully considering the available evidence (e.g. the content of the testimony). Often heuristic judgements are made using stereotypes, assumptions, previous experiences, and inferences and these can be misleading. It is often assumed that a traumatised victim should present in a distressed manner (Wrede et al., Citation2015). However, traumatised victims of crime can react in varying, disparate ways. One prominent theory is that trauma can be manifested in various forms across four domains: emotional (shock, fear, irritability, loss of pleasure, depression), cognitive (difficulty concentrating, disrupted memory, intrusive thoughts, decreased self-esteem), physical (sleep disturbance, increased activity level, decreased appetite), and behavioural (social withdrawal, conflicts or aggression, avoidance, increased risk taking; Kanan & Plog, Citation2015). Moreover, there are many factors that can impact an individual’s response to trauma, such as availability of appropriate support systems and their personal resilience (e.g. Smith, Citation2013). Given that trauma literature indicates victims will present in unique ways, and not necessarily appear distressed (McAdams & Jones, Citation2017), determination of victim credibility based solely on the distressed emotional presentation of the victim, instead of on the victim’s testimony, may result in victims being deemed less credible than they ought to be. Additionally, adult victims who do not present in the expected distressed way can also be considered as being subjected to a form of secondary victimisation, where victims are ‘wounded again by the negative reactions of others’ (Baldry et al., Citation1997, p. 163). They are likely to be judged ‘with greater scepticism’ by lay persons (Klippenstine & Schuller, Citation2012, p. 79), and are therefore perceived as less believable or credible (Baldry & Winkel, Citation1998), which has negative psychological consequences for the victim. For example, victim blaming, where an individual is held partially responsible for their situation and ‘regarded with suspicion and mistrust’ (Winkel & Koppelaar, Citation1991, p. 29), is probably the most researched form of secondary victimisation.

Victim blaming often occurs when people accept myths about rape (e.g. the belief that perpetrators of rape are usually strangers, Dawtry et al., Citation2019), have a lack of understanding about consent (Hills et al., Citation2021) and being intoxicated at the time of the incident (Osman & Davis, Citation1999) leading to individuals being less likely to report (Fisher et al., Citation2003), experiencing feelings of shame (Schmitt et al., Citation2021) and PTSD symptoms (Ullman & Peter-Hagene, Citation2016).

Child victims

Child victims are often called to testify in court. However, ascertaining exact global figures is difficult, due to data not being widely available. Plotnikoff and Woolfson (Citation2011) state that in England and Wales, child testimony increased by 60% between 2006 and 2009. At least 21,575 children were subpoenaed between January 2017 and September 2019 to attend Crown or magistrate Court hearings as victims, according to the UK Crown Prosecution Service Victims Management Information System.Footnote1 The number of children appearing as witnesses in nine European states is estimated to be around 2.5 million annually (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Citation2017). Pantell (Citation2017) states that in the U.S.A., more than 100,000 children appear in court each year. It is clear that a significant number of young people are being called to give evidence in criminal trials globally.

The cultural context in which children give evidence varies around the world. In countries which have an adversarial system, such as England, Wales and the U.S.A., juries are composed of the lay public and children are expected to be cross examined during live proceedings either in situ or via video link. Courts in England and Wales are currently rolling out a new scheme whereby the child gives their evidence prior to the trial. This is recorded and subsequently played to the jury (pre-trial cross examination), however, the implementation of that scheme has been slow (Plotnikoff & Woolfson, Citation2011). Other countries, such as Sweden and Norway, employ a cooperation model with juries consisting of both professional and lay judges. The role of the professional judge is to advise on matters of law and to remain impartial as it is considered that lay jurors tend to be less informed about legal matters and are more likely to be emotionally influenced by the contents of criminal trials (Malsch, Citation2009).

Given their participation in many criminal trials, it is important to understand how jurors come to assess the credibility of testimony from children. Credibility research of child victims has tended to focus on the interplay between the child’s ability to be accurate in their recall of events versus the juror’s rating of the child’s individual abilities during testimony. For example, many studies have examined a child’s ability to differentiate between fact and fiction or to be deceptive (e.g. Antrobus et al., Citation2016; Block et al., Citation2012; Ross, Citation2018). Research has shown that children as young as 2 years old are able to be deceptive because motivators for lying, such as self-enhancement and self-protection, develop from a sense of self which emerges from this age (Evans & Kang, Citation2013; Talwar & Crossman, Citation2012). However, sophistication in lying develops as cognitive ability increases and therefore mastery of this skill increases with age, with children being able to produce purposeful lies from the age of 4 when they have acquired the cognitive skills of theory of mind and deontic reasoning (Talwar & Crossman, Citation2012). Some research has concluded that younger child victims, from 5 to 11 years old, are deemed to be less credible than adults and older children because their memory ability is not yet fully developed. Some researchers posit that this is because children are more susceptible to imagination, coaching from adults, and are more suggestible to misinformation (e.g. Antrobus et al., Citation2016; Brown & Lewis, Citation2013; Eaton et al., Citation2001). Other research, however, argues that younger children are rated as more credible than older children in sexual offence cases (Bottoms & Goodman, Citation1994; Nightingale, Citation1993; Ross et al., Citation2003), possibly because younger children typically lack the sexual knowledge and experience to be able to fabricate complex stories. Ross et al. (Citation2003), found that children aged under 12 were deemed to be more credible than children aged 12–18, although it should also be noted that children’s understanding of sexual acts and abuse vary across individuals (Bottoms et al., Citation2003).

Research also shows that extra-legal factors can influence adults’ assessments of children’s credibility. The demeanour of a child victim, under the age of 18, appears to influence observers’ decision-making processes and judgements of their credibility (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; Cooper et al., Citation2014). Several studies reported an emotional victim effect and used expectancy violation theory to explain observer’s ratings of the credibility of child victims (Cooper et al., Citation2014; McAuliff et al., Citation2015); arguing that if a child presents incongruently to observer expectations, it is likely the child will be rated as less credible. Factors such as juror age and gender also appear to be associated with variation in adults’ perception of child credibility. For example, some research has reported that female jurors give child victims higher credibility ratings than their male counterparts (Baldry et al., Citation1997; Bottoms et al., Citation2014).

To date, however, there has not been an attempt to consolidate the existing research to provide a robust overview and critical analysis of the literature examining how child victim demeanour influences credibility judgements, and exploring the possible moderating factors. It is important to review the literature on child victims because it is possible that the emotional victim effect is different for children than adults. For example, jurors may have different ideas about how child victims compared to adult victims should behave, or may be more likely to have a compassion-affective response towards a child than towards an adult due to the assumption that adults are responsible for safeguarding children (Ask & Landstrom, Citation2010). Here, we conduct a systematic literature review to determine how the emotional presentation of a child victim impacts on juror perception of credibility during testimony. We provide an overview of what is currently known, identify gaps in knowledge, and discuss methodological limitations to make suggestions for future research and practice.

Method

Search terms

We developed a PICO framework (see ). The review examined research comparing different emotional presentations of young victims giving testimony to subsequent credibility judgements made by jurors. Although a recent meta-analysis of the adult literature by Nitschke et al. (Citation2019) considered only female sexual assault complainants, here we do not restrict our search to female children, nor specify the crime type, because we wanted to explore whether similar findings that have been observed in the adult literature also apply to children.

Table 1. PICO framework table and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Using the PICO framework, the following search terms and operators were used:

Child* OR adolesc* OR juvenile OR minor OR teen* OR you*

Victims OR bystander OR eyewitness* OR spectator

Credibility OR Integrity OR reliability OR trustworth* OR validity OR believability

Jury OR juror OR layperson

Perception OR attitude OR impression OR judgement OR opinion

Emoti* OR affect OR reaction OR empathy or respons*

Sources of literature

A systematic search was conducted using the search terms on the 3rd of August 2019, using five databases: OVID Psycinfo, Web of Science, Scopus, Social Services Abstracts, and Wiley Online Library. A total of 1,946 articles across the databases were identified. An initial scoping of these studies excluded 1,863 for not meeting the inclusion criteria. This resulted in a total of 83 articles put forward for a screening of the abstract for relevance. Once the 83 articles were screened using the inclusion/exclusion criteria, nine articles remained. A further two articles were identified through hand searches of the reference lists of the included papers, taking the total number of included papers to eleven. The first author contacted a leading researcher in the field who was able to provide some background reading, but no further research for inclusion in the review. Next, the full articles were screened, and three studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Therefore, eight studies remained to be included in the review (see ).

Quality assessment

The CASP quality assessment tool (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2019) applied to the eight studies had eleven questions (see ).

Table 2. Quality assessment questions on the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2019).

The first three questions were used to identify quickly if a paper should be excluded and the remaining eight questions to assess sampling, performance and measurement biases, size of outcome effects, and ethical issues. Each question was weighted equally with a Yes (9 points), No (0 points), or Partial (4.5 points) scoring system used to calculate a total quality percentage score out of 100 reflecting overall quality. The CASP (Citation2019) does not provide a cut off or scoring system, due to it being designed to be used as an educational pedagogic tool. The CASP method of quality assessment primarily provides a means of weighting the importance of each paper within the studies included in the review, so we set a liberal cut-off and decided that papers with a quality score over 50% would be deemed robust enough to be included. Quality scores ranged from 72% to 94.5% (see ), thus all eight studies were included.

Table 3. Extracted article information.

Data extraction

Data from the studies were extracted using a form adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration. The sub-sections included on the form were: general information, eligibility, methods, outcome measures, results, and key conclusions. summarises the salient data from each article as extracted during this process.

Results

The eight articles demonstrate that the presence of emotion in child victim testimony influences mock juror perceptions of credibility. In the sections that follow, we discuss how mock jurors’ credibility judgements may be influenced by the following factors: emotional (e.g. sad) versus neutral presentation, different types of emotional presentation (e.g. sad, happy, angry, and neutral), empathy, age of child victim, and gender of the participants. We first provide a brief overview of the included studies.

Overview of studies

The key experimental manipulation in all studies was the emotional presentation of the child, with varying presentations across the studies of sad, angry, happy, or neutral. In all of the studies, participants were randomly allocated into the emotional presentation conditions. Three of the studies compared sad versus neutral presentation (Cooper et al., Citation2014; Landström et al., Citation2015; Regan & Baker, Citation1998); two compared different amounts of sadness (low, medium, and high sadness, Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; calm, teary, or hysterical crying, Golding et al., Citation2003); and three compared sad, angry, happy, and neutral emotional presentations (Melinder et al., Citation2016; Wessel et al., Citation2013; Wessel et al., Citation2016). Across all studies, credibility was measured using rating scales which were individually designed and applied in each study. Five studies also asked participants to rate defendant guilt (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; Golding et al., Citation2003; Regan & Baker, Citation1998; Wessel et al., Citation2013; Wessel et al., Citation2016).

In total, the eight studies sampled 2,148 participants: 1,323 females and 825 males. All of the studies recruited participants from student populations and two of the studies also recruited non-student comparison groups (Cooper et al., Citation2014; Wessel et al., Citation2013). Unsurprisingly, the age range for the non-student comparison groups was slightly wider (18–80 years old) than the age range for the student groups (18–64 years old). Four studies were conducted in the United States of America (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; Cooper et al., Citation2014; Golding et al., Citation2003; Regan & Baker, Citation1998), three in Norway (Melinder et al., Citation2016; Wessel et al., Citation2013; Wessel et al., Citation2016), and one in Sweden (Landström et al., Citation2015). The main findings from each study are outlined in below.

Table 4. Main findings of studies.

Sad versus neutral presentation

Four of the papers in the review directly compared sad versus neutral presentation. All four of these studies found that the presence of emotion (e.g. sad) compared to a neutral or calm demeanour resulted in mock jurors rating the victim as more credible (Cooper et al., Citation2014; Golding et al., Citation2003; Landström et al., Citation2015; Regan & Baker, Citation1998). The above studies use different stimuli presentation modes (e.g. drawings, mock case study, scripts, and videos) but all demonstrated similar significant results; that an emotional child is more likely to be regarded as credible than a child who is presenting neutrally.

Emotion type

Further research has investigated how different types of emotion (such as angry or happy presentations) influence credibility judgements. Three studies extend the sad and neutral/calm conditions to include angry and positive emotional presentations. Wessel et al. (Citation2013) demonstrated across both students and CPS participants that the child victim was rated as most credible in the sad condition followed by the neutral condition, then the angry condition, and there was a significant drop in credibility rating for the positive condition. Melinder et al. (Citation2016) found that when the child victim displayed sad emotions they were deemed to be significantly more credible than if the child presented as angry or positive. But in contrast to Wessel et al. (Citation2013), Melinder et al. (Citation2016) found the neutrally presenting victims were rated almost as credible as sad presenting victims. Wessel et al. (Citation2016) did not find a difference in ratings of credibility between the sad and neutral presentation of emotion and they therefore combined these conditions to create an ‘emotional valence’ condition. The study concluded emotional valence (sad or neutral presentation) resulted in significantly higher ratings of credibility compared to angry and positive presentation.

Empathy

Only one study in the review (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017) explored if juror empathy influenced the appraisal of the child’s emotional feelings and therefore judgements of credibility. Their study enlisted undergraduate students who observed pictures of children displaying low, medium and high levels of sad/teary expressions and asked to rate the level of emotion displayed, ratings of credibility, and complete a child victim empathy questionnaire before and after participation in the experimental stage. The juror’s appraisal of the child’s emotional presentation and empathy scores both predicted credibility scores of the child victims.

Age of child victims

The emotional victim effect has been found across studies using child victims of different ages (ages 5–15 in the studies reviewed here) suggesting that this phenomenon is observed across age groups. However, three studies have shown that child age may also influence credibility judgements. Cooper et al. (Citation2014) found that female lay jurors rated younger children (6 years old) as more credible than male lay jurors who rated younger and older (13 years old) children equally. Bederian-Gardner et al. (Citation2017) partly replicated this result, as their (male and female) participants rated younger children (5 years old) as more credible than older children (13 years old). Melinder et al. (Citation2016) however found that older victims (13 years old) were considered significantly more credible than younger victims (11 years old).

Gender of participants (Adult jurors)

Seven out of the eight studies examined whether the gender of the participants influenced credibility judgments; this review highlighted that the credibility judgements varied by gender across all seven studies. Golding et al. (Citation2003), Cooper et al. (Citation2014), and Wessel et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that women were more likely than men to pass guilty verdicts. Regan and Baker (Citation1998), Melinder et al. (Citation2016) and Wessel et al. (Citation2013) also found that female participants were significantly more likely to rate an emotionally presenting child victim as more credible than male participants. This finding was replicated by Bederian-Gardner et al. (Citation2017) who found that female participants rated an emotionally presenting child victim as more believable than male participants did.

Type of crime

The studies used different offence types, including familial sexual assault (Cooper et al., Citation2014; Regan & Baker, Citation1998; Wessel et al., Citation2016), interfamilial sexual assault (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; Golding et al., Citation2003), familial physical assault (Melinder et al., Citation2016; Wessel et al., Citation2013), and harassment from peers (Landström et al., Citation2015). As such, it seems the emotional victim effect is found across crime types for child victims.

Presentation mode

The studies used different combinations of stimuli including written transcripts (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; Cooper et al., Citation2014; Golding et al., Citation2003; Melinder et al., Citation2016; Regan & Baker, Citation1998), videotapes (Landström et al., Citation2015; Melinder et al., Citation2016; Wessel et al., Citation2013; Wessel et al., Citation2016), audio recordings (Melinder et al., Citation2016), photos (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017), and drawings (Cooper et al., Citation2014; Golding et al., Citation2003). Again, the emotional victim effect was found across the studies, suggesting that it occurs regardless of presentation mode. However, one study by Melinder et al. (Citation2016) directly compared presentation modalities in their study and demonstrated that when a child displayed as sad, transcripts elicited higher credibility ratings than video or audio recordings, suggesting that presentation mode might increase or decrease the size of the emotional victim effect.

Discussion

This review examined whether the emotional demeanour of child victims during testimony influences perceived credibility in mock jurors. This effect has been substantiated in adult female sexual assault complainants in a recent meta-analysis (Nitschke et al., Citation2019), but there has been no previous attempt to consolidate findings in the child victim literature. Despite considerable differences in samples and methodologies across studies included in the review, it was found that child victims who displayed a sad emotional demeanour were rated as more credible by adult mock jurors than other emotional presentations such as anger, happiness, or neutral expressions. The following discussion will draw conclusions from this review, discuss the methodological issues that could have influenced the results, consider the implications of this review for practice, and consider future research directions.

The review found an emotional victim effect; adult jurors were influenced by the emotional presentation of a child victim, and deemed children who present as sad as more credible than those who do not. Moreover, the proportionality of the emotion appears to impact on credibility judgements. In accordance with expectancy violation theory, the proportionality of the emotional response influenced subsequent ratings of credibility (see Rose et al., Citation2006). For example, Golding et al. (Citation2003) found that the hysterical child in their research was deemed less credible than a child presenting as teary. They concluded that it is not simply a case of the presence of sad behaviour (such as crying) leading to an increase in ratings of credibility; it appears that too much or too little emotion negatively impacted participants’ judgement of the child’s believability. These findings replicate and extend findings in the adult literature with female sexual assault complainants (Nitschke et al., Citation2019; Rose et al., Citation2006). This review found the presence of the emotional victim effect across a range of crime types (e.g. sexual assault, physical assault, harassment), whereas the adult literature has mainly investigated the emotional victim effect in female sexual assault victims. Some research on male victims (e.g. Landstrom et al., Citation2015; Rose et al., Citation2006) and victims of other types of crimes have failed to replicate the emotional victim effect in adult populations (Bosma et al., Citation2018). This review also extends understanding by considering the type of emotion displayed (anger, sadness, happy, and neutral) which has not been considered in previous adult research. This review found that angry, happy, and neutral presentations are often rated as less credible than sad presentations.

There are at least two mechanisms by which a victim’s emotional presentation influences juror credibility judgements. First, emotion violation theory predicts that jurors hold cognitive biases including preconceived notions, stereotypes and social expectations of how the child should present in court; the social norms governing expectations of how a victim should respond impacts on subsequent credibility ratings. If the child does not present in the expected congruent manner (e.g. sad), the adult is less likely to believe that the child is credible and attribute this to internal factors within the child, such as deception (Ross, Citation2018). Second, it may be that a sad demeanour in a child elicits an empathetic caregiving response in the adult, compared to angry, happy, and neutral presentations (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017). In contrast, a child presenting with an angry demeanour may produce different emotions in adults such as an angry or avoidant response. Therefore, the emotional victim effect may be also influenced by the compassion affective response. Indeed, Landström et al. (Citation2015) concluded that a sad child better matched the participants expectations of how the child should respond compared to a neutrally presenting child, but also showed that participants had an affective response to the sad child victims. Therefore, as posited by Ask and Landstrom (Citation2010), a combination of the cognitive and affective responses are likely to be responsible for the emotional victim effect. The two explanations (cognitive and affective) are not mutually exclusive, so future research is needed to isolate and understand the relative importance of each mechanism.

Regardless of the underlying mechanism, the fact that jurors are influenced by child victim presentation is concerning because emotional presentation does not accurately indicate that victims are honest and reliable, and crime victims’ emotional reactions differ dramatically. According to a trauma framework, a child will present in a unique manner dependent upon their coping mechanisms and recovery following trauma (Kanan & Plog, Citation2015). Some research is beginning to show that children display a variety of emotions during disclosure including happiness, anger, sadness, anxiety, shame, and guilt (Wood et al., Citation1996). Therefore, determining a child’s credibility based on emotional presentation alone, is unreliable and could lead to poor legal decision-making. Future work should aim to better understand the variety of responses demonstrated by child victims in the criminal justice system and practitioners (and possible lay jurors) should be informed about the different ways in which a traumatised child may present during a criminal investigation.

The review also discussed possible factors that influenced credibility judgements, such as the gender of participants, the age of the child victim, and the presentation mode. These factors were often not consistently considered throughout the methodology of the eight studies or directly compared in a single study, therefore it is only possible to speculate on their impact. Nevertheless, there were some consistent trends across studies. First, seven out of the eight studies compared male and female participants, and females were consistently more likely to consider the child as credible compared to males (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; Cooper et al., Citation2014; Golding et al., Citation2003; Regan & Baker, Citation1998; Wessel et al., Citation2013; Wessel et al., Citation2016). It is not clear why a gender difference is observed; however, Wessel et al. (Citation2013) theorise that women may be more empathically accurate than men (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017). Previous research indicates that females make significantly more pro-victim judgements, influenced by attitudes and empathy (e.g. Baldry et al., Citation1997; Bottoms et al., Citation2014). Overall, the studies included in this review provide evidence for female participants generally rating children as more credible when they emotionally present in a manner that is congruent with their expectations.

Second, the age of the child may influence credibility ratings. Four of the eight studies compared child age. In three of these studies the target offence was sexual abuse and these studies found that younger children (aged 5–6 years old) were deemed more credible than children aged 11–13 years. It is possible that younger children (5 or 6 years old), who are assumed to lack the sexual knowledge and experience to be able to fabricate stories (Antrobus et al., Citation2016; Brown & Lewis, Citation2013; Eaton et al., Citation2001; Ross et al., Citation2003), and to be more naïve about the harmful impacts of sexually abusive behaviour, would be considered to be more likely to be telling the truth, and therefore rated as more credible, than older children (11 or 13 years old) who are assumed to have more sexual knowledge and an understanding of the serious nature of the allegations. However, it should be noted that this conclusion is tentative, because children’s understanding of sexual crimes is highly individual (Bottoms et al., Citation2003). It is a limitation of the current literature base that studies tend to involve younger children (5–6 years old) or slightly older children (11 or 13 years old). Research has not yet examined children under 5 years, between 6 and 11 years and over 13 years; future research would benefit from considering these gaps because it is possible that the relationship between child age and credibility judgements is non-linear.

Third, the emotional victim effect was observed across the different presentation modes used in the eight studies. It is possible, however, that the size of the effect or the mechanism of the effect is different across presentation modes. Melinder et al. (Citation2016) was the only study that manipulated the presentation mode in a single experiment and found higher ratings of credibility for written presentations than audio or visual. This influence of presentation mode is inconsistent across the adult victims literature. For example, Nitschke et al. (Citation2019) concluded that distress in female sexual assault victims increases credibility judgements despite the presentation model. However, Landstrom et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that live accounts of female interpersonal violence victims were rated as more credible than video evidence. Further research investigating presentation mode for child victims, or directly comparing child and adult victim populations across presentation modes, is required to bolster the current conclusions.

Limitations of the current research

Although it is clear that results were replicated across the studies included in this review, it is important to note that the literature available lacks a shared definition of credibility. This has led to unstandardised methodologies and outcome measures in the empirical research; and it is therefore difficult to definitively conclude that authors are measuring the same concept across studies. Credibility is a multifaceted construct, measured on the basis of observation and subject to various interpretations. Voogt et al. (Citation2019), for example, argue that believability, honesty, truthfulness, suggestibility, accuracy, and reliability are constructs associated with credibility. The outcome measures throughout the eight studies appear to have been designed by the researchers without consideration of measures used in previous studies, which make it difficult to determine if measures have acceptable reliability, or content and construct validity. Therefore, future researchers may wish to consider standardising definitions across child victim research. A shared definition of credibility means that a collaborative outcome measure (that is shown to be valid and reliable) could be employed across studies (Voogt et al., Citation2019). A collective approach from researchers would arguably serve to strengthen the overall evidence base and provide a consistent and versatile measurement for the multifaceted concept of credibility.

The eight articles in this review have employed a mock juror design; a method which has been hotly debated and also criticised for failing to simulate a real-life situation (e.g. see Golding et al., Citation2003). We will not repeat that debate here, but instead focus on several potential limitations in the child literature specifically, including sampling issues, stimulus and outcome measure issues, test condition issues and ethical considerations. These are considered next.

Sampling issues

All eight of the studies reviewed recruited a student population sample, of which only three outlined the demographic nature of the sample beyond age and gender variation (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; Cooper et al., Citation2014; Regan & Baker, Citation1998). The mean age range of the student samples in the eight studies was 20.4 years (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017) to 28 years (Wessel et al., Citation2013) demonstrating a young mean age across the studies. Two studies (Cooper et al., Citation2014; Wessel et al., Citation2013) employed different samples in the form of jurors released from duty (mean age not given) and child protection service officers (mean age = 39 years).

Previously, research recruiting undergraduate students has been criticised for lacking generalisability. The student populations within the studies can be considered a homogenous group, meaning that it is easier to draw comparison across the studies, however lack of data from other societal groups with varying demographics means it may be difficult to apply the findings of the research to wider non-student populations. However, a meta-analysis of 53 mock juror studies conducted by Bornstein et al. (Citation2009) found that credibility and guilt ratings did not vary across samples and concluded that student mock juror studies can be a valid methodology. Juries are designed to consist of lay samples of the general public. Therefore, the current available literature may be a good first step towards understanding this phenomenon, but further research with other groups is needed.

Test conditions

Worthy of note are the test conditions used across the eight studies. All of the studies required the participants to work individually in quiet conditions to avoid distractions. The studies also did not present other possibly relevant information such as other victims’ statements, legal arguments, and other forms of evidence (such as physical forensic evidence), which may be available in a trial and which would inform the decision-making process (Melinder et al., Citation2016; Wessel et al., Citation2013; Wessel et al., Citation2016). The cognitive load experienced by jurors in real trials would not have been replicated in these studies which required a brief, intense focus of concentration on a small amount of information. On one hand, it is possible that participants were more influenced by the emotional presentation of the victim than they may have been in a real trial, because they had relatively sparse information to rely upon, and were therefore more likely to rely on their stereotypes to make credibility judgments. On the other hand, the heuristic-systematic model of information processing posits that heuristic processing occurs when information is more complex and requires more cognitive effort (Chaiken, Citation1980). Heuristic processing relies on previous knowledge stored in memory and tends to scrutinise information in less detailed ways than systematic processing, which is more analytic and likely to incorporate new information. Therefore, is it possible that jurors in real trials are more influenced by the emotional expression of the victim than participants were in the experiments, because they are more likely to utilise heuristic processing, due to the amount of novel information they experience (Honess & Charman, Citation2002). Research in the future would benefit from addressing some of these shortcomings through closer replication of the cognitive load experienced by jurors in real life, which would serve to increase the ecological validity of the literature base.

In a real-life trial situation, countries with adversarial systems such as the United Kingdom and the United States of America, the jurors would also deliberate before passing a verdict. Groupthink is considered a cognitive bias in group decision making processes, leading to an increase in ‘defective decision making’ (Neck & Moorhead, Citation1992, p. 1007), and may also occur in juror decision-making (Cooper et al., Citation2014). The presence of groupthink in jury deliberations may serve to moderate the size of the emotional victim effect on individual juror decisions, due to the social pressures of the group. Several of the studies included in this review did state this omission in design as a limitation of their research (Bederian-Gardner et al., Citation2017; Cooper et al., Citation2014; Golding et al., Citation2003). As such, the impact of groupthink on deliberations should be considered for any future studies in this area. Moreover, qualitative research with real jurors may enhance understanding of the rich, detailed experience of juror decision-making in complex trials.

Strengths and weaknesses of this review

This literature review applied the robust methodology to its searches, quality assessment, and data extraction, and the articles included were all rated as good quality. Nevertheless, only eight studies were included in the review. The initial searches and scoping identified a limited number of articles. We were also only able to search for articles published in the English language; inclusion of other languages may have increased the number of articles included, and future researchers may wish to do so. Finally, publication bias occurs when articles are published on the basis of having significant findings which build on previously accepted hypotheses. All of the articles included in this review reported a significant emotional victim effect which built on previous research findings. It is possible that there is a publication bias in this field, with similar research that failed to find a significant result, or which challenges the previously accepted findings, not being chosen for publication. As others have noted (e.g. Cook & Therrien, Citation2017), it is important for scientific enquiry that null effects are also published and accessible to other researchers.

Practical applications

Although the studies in this review were concerned with lay juror decision-making, it is important to consider that child victims in the criminal justice process will have been subjected to several tests of credibility prior to reaching the point of testimony. Regardless of country, each child will experience a series of encounters with professionals prior to trial, such as interviews with Police, Social Care and other professionals where judgements of credibility will be made. Moreover, children in some countries will provide testimony to judges, not lay jurors. Our review highlights that people can rely on misleading information to form credibility judgments, and it is possible that professionals at other stages in the criminal justice process rely on potentially misleading heuristic processing. This has important implications, because professionals’ credibility judgments are likely to impact how the crime is subsequently investigated and decisions made regarding the child’s welfare (e.g. removal from the family home for child protection reasons). It would be appropriate for both practitioners and researchers to consider the emotional victim effect more broadly, not only at the point of trial, but also at other victim-observer interactions throughout the investigation process.

As a concrete example, for many children who have experienced sexual violence, judgements of credibility can begin at the forensic medical examination. The World Health Organisation (Citation2003), states: ‘as medical records can be used in Court as evidence, documenting the consequences of sexual violence may help the court with its decision-making as well as provide information about past and present sexual violence’ (p. 94). Further, they state that health professionals should ‘include observations of the interactions between, and the emotional states of, the child and his/her family’ (p. 84). In England and Wales, the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians has published the Paediatric Forensic Examination Pro Forma on their website (June 2020), which all forensic examiners are required to use in their practice. This form, which is admissible as evidence in any subsequent trial, compels the medical examiner to record the child’s demeanour/behaviour at the time of examination. The admission of this information in any subsequent trial is likely to be subject to the same heuristic processing outlined in this review and could potentially influence subsequent ratings of credibility. Given that a child’s emotional reaction is not a reliable indicator of accuracy or truthfulness, it seems reasonable to suggest that reference to the child’s demeanour or behaviour during forensic medical examination be removed from official forms and records, or be deemed inadmissible as evidence in any subsequent trial. Again, we urge other researchers to consider the broader implications of credibility judgements made by different professionals and at different stages of the criminal justice system.

Another important consideration for forensic practice is that, in real life, rehearsal effects could impact on the child’s presentation in court, possibly making them appear calmer than on first disclosure. Pre-court conversations by well-intentioned adults (Police, Social Services, Caregivers) with the child might give them ‘prompts’ regarding how to present themselves in court. Court practitioners should be conscious of these influences before the child gives testimony and the judiciary should consider any impacts on admissibility of evidence and in their instructions to the jury. Moreover, rehearsal and repeated interviews have been shown to encourage reminiscence, aid rapport with the child, aid disclosure, and also to help the child emotionally regulate during distressing conversations (Brubacher et al., Citation1912). As such, children giving evidence in court may be relatively calm, and deemed to be less credible than if the jurors had seen the child at first disclosure.

The findings of this review also highlight the need for consideration of support that can be offered to jurors during trials to better interpret the emotional expressions of child victims. It may be prudent to consider experts being employed as standard practice in all cases where a child is appearing as a victim, or extending the use of trained intermediaries or Child Independent Advisors to help the child communicate with the court. Both of these suggestions would come at a financial cost to the legal system, but would create a role for professionals to educate jurors on both emotional presentation and trauma responses. An alternative method to support jurors, would be to consider judicial instruction. Swedish courts, in 2010, started instructing juries to place less weight on non-verbal behaviours when making assessments of credibility (Landström et al., Citation2015). Additionally, Connolly et al. (Citation2008) demonstrated that the inclusion of a judicial declaration of child competence increased the credibility ratings of child victims compared to control groups who received no such declaration. Adoption of a similar method in other countries may help to mitigate the emotional victim effect, and help jurors to rely on more systematic processing of information.

A final point to consider that has not yet been considered by research, is that some young victims may present incongruently to jurors expectations due to additional needs such as learning difficulties or neurological issues (Autism Spectrum Disorder, for example). Mandell et al. (Citation2005) state that 18.5% of adult caregivers of children with autism report their child had experienced physical abuse and 16.6% reported experiences of sexual abuse. It has previously been recommended that a child’s needs should be identified early in the legal process and special measures put into place to help the child communicate (Bottoms et al., Citation2003), but it is also crucial to consider how these individual differences may impact on the child’s non-verbal emotional presentation at court. Children who have additional needs such as a neurodiverse presentation or learning difficulties are more likely to present in an incongruent way to juror expectation (Bottoms et al., Citation2003; Brown & Lewis, Citation2013; Crane et al., Citation2018). Therefore, these cases should arguably be prioritised in terms of jury education by experts and intermediaries to prevent legal-decision makers relying on misleading cues to determine victim credibility.

Conclusion

Perceptions held by jurors appear to have profound real-life consequences for the parties involved; such as the defendant being found guilty of an offence, or the victim not being believed. This review indicates that the emotional presentation of a child victim influences juror ratings of credibility, which is concerning, as it may result in misleading conclusions about the accuracy and truthfulness of a child’s account. Further research should attempt to explore how different factors influence the emotional victim effect, exploring the proportionality of emotion (Golding et al., Citation2003), and the role of groupthink in jury deliberations, when combined with emotionally presenting child victims. Researchers should contemplate the introduction of standardised definitions of credibility and design outcome measures that can be replicated throughout the research. In practice, court practitioners and policy makers should consider how reliance on a child’s emotional presentation can be mitigated in making credibility judgements; either by the employment of experts and professionals to guide jurors or judicial instruction. Finally, both researchers and practitioners should consider the influence of a child victim’s emotional presentation at other stages of the criminal justice process, such as disclosure and interview.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Materials. The materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/xabep/.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A Freedom of Information (FOI) was submitted in September 2019. These figures require several caveats to aid interpretation; first, not all jurisdictions use the Victims Management System and therefore the figures given may underestimate the number of children appearing as victims nationally. Second, the figures relate to the numbers of young victims subpoenaed to appear as victims; there may be several reasons the child does not eventually give testimony, including late guilty pleas by the defendant and adjournments of the Court.

References

- **Indicates that the study was included in the review.

- Crown Prosecution Service statistics (Witness Management System) released under a Freedom of Information request, September 2019.

- R v B [2010] EWCA Crim 4.

- Antrobus, E., McKimmie, B. M., & Newcombe, P. (2016). Mode of children's testimony and the effect of assumptions about credibility. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(6), 922–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2016.1152927

- Ask, K., & Landstrom, S. (2010). Why emotions matter: Expectancy violation and affective response mediate the emotional victim effect. Law and Human Behavior, 34(5), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-009-9208-6

- Baldry, A. C., & Winkel, F. W. (1998). Perceptions of the credibility and evidential value of victim and suspect statements in interviews. In J. Boros, I. Munnich, & M. Szegedi (Eds.), Psychology and criminal justice: International review of theory and practice (pp. 74–82). De Gruyter.

- Baldry, A. C., Winkel, F. W., & Enthoven, D. S. (1997). Paralinguistic and nonverbal triggers of biased credibility assessments of rape victims in Dutch police officers: An experimental study on ‘nonevidentiary bias’. In S. Redondo, V. Garrido, J. Perez, & R. Barabaret (Eds.), Advances in psychology and law: International contributions (pp. 163–174). De Gruyter.

- **Bederian-Gardner, D., Goldfarb, D., & Goodman, G. S. (2017). Empathy's relation to appraisal of the emotional child victims. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 31(5), 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3345

- Block, S. D., Shestowsky, D., Segovia, D. A., Goodman, G. S., Schaaf, J. M., & Alexander, K. W. (2012). That never happened": adults’ discernment of children's true and false memory reports. Law & Human Behavior, 36(5), 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093920

- Bollingmo, G., Wessel, E., Sandvold, Y., Eilertsen, D. E., & Magnussen, S. (2009). The effect of biased and non-biased information on judgments of victims credibility. Psychology, Crime & Law, 15(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160802131107

- Bornstein, B. H., Golding, J. M., Neuschatz, J., Kimbrough, C., Reed, K., Magyarics, C., & Luecht, K. (2009). Mock juror sampling issues in jury simulation research: A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior, 41(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000223

- Bosma, A. K., Mulder, E., Pemberton, A., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2018). Observer reactions to emotional victims of serious crimes: Stereotypes and expectancy violations. Psychology, Crime & Law, 24(9), 957–977. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2018.1467910

- Bottoms, B. L., & Goodman, G. S. (1994). Perceptions of children's credibility in sexual assault cases. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24(8), 702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00608.x

- Bottoms, B. L., NysseCarris, K. L., Harris, T., & Tyda, K. (2003). Jurors’ perceptions of adolescent sexual assault victims who have intellectual disabilities. Law & Human Behavior, 27(2), 205–227. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022551314668

- Bottoms, B. L., Peter-Hagene, L. C., Stevenson, M. C., Wiley, T. R. A., Mitchell, T. S., & Goodman, G. S. (2014). Explaining gender differences in jurors’ reactions to child sexual assault cases. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 32(6), 789–812. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2147

- Brown, D. A., & Lewis, C. N. (2013). Competence is in the eye of the beholder: Perceptions of intellectually disabled child witnesses. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 60(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2013.75713

- Brubacher, S. P., Poole, D. A., Dickinson, J. J., La Rooy, D., Szojka, Z. A., & Powell, M. B. (1912). Effects of interviewer familiarity and supportiveness on children’s recall across repeated interviews. Law and Human Behavior, 43(6), 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000346

- Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 752–766. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.752

- Connolly, D. A., Gagnon, N. C., & Lavoie, J. A. (2008). The effect of a judicial declaration of competence on the perceived credibility of children and defendants. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13(2), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532507X206867

- Cook, B. G., & Therrien, W. J. (2017). Null effects and publication bias in special education research. Behavioral Disorders, 42(4), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742917709473

- **Cooper, A., Quas, J. A., & Cleveland, K. C. (2014). The emotional child victims: Effects on juror decision-making. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 32(6), 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2153

- Crane, L., Wilcock, R., Maras, K. L., Chui, W., Marti-Sanchez, C., & Henry, L. A. (2018). Mock juror perceptions of child witnesses on the autism spectrum: The impact of providing diagnostic labels and information about autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(5), 1509–1519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3700-0

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2019). CASP checklist for randomised control trials. https://casp-uk.net

- Dahl, J., Enemo, I., Drevland, G. C. B., Wessel, E., Eilertsen, D. E., & Magnussen, S. (2007). Displayed emotions and victims credibility: A comparison of judgements by individuals and mock juries. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21(9), 1145–1155. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1320

- Dawtry, R. J., Cozzolino, P. J., & Callan, M. J. (2019). I blame therefore it was: Rape myth acceptance, victim blaming, and memory reconstruction. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(8), 1269–1282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218818475

- Eaton, T. E., Ball, P. J., & O'Callaghan, M. G. (2001). Child-victims and defendant credibility: Child evidence presentation mode and judicial instructions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(9), 1845–1858. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00207.x

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2017, February). Child-friendly Justice. https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2017/child-friendly-justice-childrens-view

- Evans, A. D., & Kang, L. E. (2013). Emergence of lying in very young children. Developmental Psychology, 49(10), 1958–1963. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031409

- Fisher, B. S., Daigle, L. E., Cullen, F. T., & Turner, M. G. (2003). Reporting sexual victimization to the police and others: Results from a national-level study of college women. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30(1), 6–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854802239161

- **Golding, J. M., Fryman, H. M., Marsil, D. F., & Yozwiak, J. A. (2003). Big girls don't cry: The effect of child victims demeanour on juror decisions in a child sexual abuse trial. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(11), 1311–1321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.03.001

- Hackett, L., Day, A., & Mohr, P. (2008). Expectancy violation and perceptions of rape victim credibility. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13(2), 323. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532507X228458

- Hills, P. J., Pleva, M., Seib, E., & Cole, T. (2021). Understanding how university students use perceptions of consent, wantedness, and pleasure in labeling rape. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(1), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01772-1

- Honess, T. M., & Charman, E. A. (2002). Members of the jury - guilty of incompetence? The Psychologist, 15(2), 72.

- Kanan, L., & Plog, A. (2015). Trauma reactions in children: Information for parents and caregivers. National Association of School Psychologists Communique, 44(2), 27–28.

- Kaufmann, G., Drevland, G. C. B., Wessel, E., Overskeid, G., & Magnussen, S. (2002). The importance of being earnest: Displayed emotions and victims credibility. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.842

- Klippenstine, M. A., & Schuller, R. (2012). Perceptions of sexual assault: Expectancies regarding the emotional response of a rape victim over time. Psychology, Crime & Law, 18(1), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2011.589389

- Landstrom, S., Ask, K., & Sommar, C. (2015). The emotional male victim: Effects of presentation mode on judged credibility. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12176

- Landström, S., Ask, K., & Sommar, C. (2019). Credibility judgments in context: Effects of emotional expression, presentation mode, and statement consistency. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2018.1519828

- Landström, S., Ask, K., Sommar, C., & Willén, R. (2015). Children's testimony and the emotional victim effect. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 20(2), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12036

- **Landstrom, S., Ask, K., & Sommar, C. (2015). The emotional male victim: Effects of presentation mode on judged credibility. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12176

- La Rooy, D., Heydon, G., Korkman, J., Myklebust, T. (2016). Interviewing child witnesses. In G. Oxburgh, T. Myklebust, T. Grant, & R. Milne (Eds.), Communication in investigative and legal contexts: Integrated approaches from forensic psychology, linguistics and law enforcement (1st ed., pp. 55–79). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118769133.ch4

- Lens, K. M. E., van Doorn, J., Pemberton, A., & Bogaerts, S. (2014). You shouldn't feel that way! extending the emotional victim effect through the mediating role of expectancy violation. Psychology, Crime & Law, 20(4), 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2013.77796

- Malloy, L. C., La Rooy, D. J., Lamb, M. E., & Katz, C. (2011). Developmentally sensitive interviewing for legal purposes. In M. Lamb E, D. La Rooy J, L. Malloy C, & C. Katz (Eds.), Children's testimony: A handbook of psychological research and forensic practice (2nd ed., pp. 1–15). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Malsch, M. (2009). Democracy in the courts: Lay participation in European criminal justice systems. Farnham.

- Mandell, D. S., Walrath, C. M., Manteuffel, B., Sgro, G., & Pinto-Martin, J. (2005). The prevalence and correlates of abuse among children with autism served in comprehensive community-based mental health settings. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(12), 1359–1372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.006

- McAdams, D. P., & Jones, B. K. (2017). In E. M. Altmaier (Ed.), Chapter 1 - making meaning in the wake of trauma: Resilience and redemption. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803015-8.00001-2

- McAuliff, B. D., Lapin, J., & Michel, S. (2015). Support person presence and child victim testimony: Believe it or not. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 33(4), 508–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2190

- **Melinder, A., Burrell, L., Eriksen, M. O., Magnussen, S., & Wessel, E. (2016). The emotional child victims effect survives presentation mode. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 34(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2232

- Mulder, M. R., & Winiel, F. W. (1996). Social workers’ and police officers’ perception of victim credibility: Perspective-taking and the impact of extra-evidential factors. Psychology, Crime & Law, 2(4), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683169608409786

- Neck, C. P., & Moorhead, G. (1992). Jury deliberations in the trial of U.S. v. John DeLorean: A case analysis of groupthink avoidance and an enhanced framework. Human Relations, 45(10), 1077–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679204501004

- Nightingale, N. N. (1993). Juror reactions to child victim witnesses: Factors affecting trial outcome. Law and Human Behavior, 17(6), 679–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01044689

- Nitschke, F. T., McKimmie, B. M., & Vanman, E. J. (2019). A meta-analysis of the emotional victim effect for female adult rape complainants: Does complainant distress influence credibility? Psychological Bulletin, 145(10), 953–979. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000206

- Osman, S. L., & Davis, C. M. (1999). Predicting perceptions of date rape based on individual beliefs and female alcohol consumption. Journal of College Student Development, 40(6), 701.

- Pantell, R. H. (2017). The child victims in the courtroom. Pediatrics (Evanston), 139(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-4008

- Plotnikoff, J., & Woolfson, R. (2011). Young witnesses in criminal proceedings. A progress report on ‘measuring Up?’ (2009). Nuffield Foundation.

- **Regan, P., & Baker, S. (1998). The impact of child victims demeanour on perceived credibility and trial outcome in sexual abuse cases. Journal of Family Violence, 13(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022845724226

- Rose, M. R., Nadler, J., & Clark, J. (2006). Appropriately upset? Emotion norms and perceptions of crime victims. Law and Human Behavior, 30(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9030-3

- Ross, D. F., Jurden, F. H., Lindsay, R. C. L., & Keeney, J. M. (2003). Replications and limitations of a two-factor model of child victims credibility. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(2), 418–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01903.x

- Ross, L. (2018). From the fundamental attribution error to the truly fundamental attribution error and beyond: My research journey. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(6), 750–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618769855

- Schmitt, S., Robjant, K., Elbert, T., & Koebach, A. (2021). To add insult to injury: Stigmatization reinforces the trauma of rape survivors – findings from the DR Congo. SSM - Population Health, 13, 100719–100719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100719

- Smith, G. (2013). In S. Frosh (Ed.), Working with trauma: Systematic approaches (1st ed.). England: Palgrave: Macmillan.

- Talwar, V., & Crossman, A. M. (2012). Children’s lies and their detection: Implications for child victims testimony. Developmental Review, 32(4), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2012.06.004

- Ullman, S. E., & Peter-Hagene, L. (2016). Longitudinal relationships of social reactions, PTSD, and revictimization in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(6), 1074–1094. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514564069

- Voogt, A., Klettke, B., & Crossman, A. (2019). Measurement of victim credibility in child sexual assault cases: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016683460

- **Wessel, E., Magnussen, S., & Melinder, A. M. D. (2013). Expressed emotions and perceived credibility of child mock victims disclosing physical abuse. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27(5), 611–616. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2935

- **Wessel, E. M., Eilertsen, D. E., Langnes, E., Magnussen, S., & Melinder, A. (2016). Disclosure of child sexual abuse: Expressed emotions and credibility judgments of a child mock victim. Psychology, Crime and Law, 22(4), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2015.1109087

- Winkel, F. W., & Koppelaar, L. (1991). Rape victims’ style of self-presentation and secondary victimization by the environment: An experiment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 6(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626091006001003

- Wood, B., Orsak, C., Murphy, M., & Cross, H. J. (1996). Semi-structured child sexual abuse interviews: Interview and child characteristics related to credibility of disclosure. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(95)00118-2

- World Health Organization. (2003). Guidelines for medico-legal care of victims of sexual violence. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42788

- Wrede, O., Ask, K., & Strömwall, L. (2015). Sad and exposed, angry and resilient?: Effects of crime victims’ emotional expressions on perceived need for support. Social Psychology, 46(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000221