ABSTRACT

The number of people seeking asylum based on their sexual orientation is expected to continue increasing. Assessing the credibility of such claims to determine whether asylum-seekers meet the criteria for refugee status is a complex task for asylum officials. These assessments involve several psychological aspects, affecting applicants’ disclosure and asylum officials’ determinations. Here, we present a narrative literature review of 47 original manuscripts to analyze credibility assessments in asylum claims based on sexual orientation. We demonstrate that asylum officials often make assumptions regarding human sexuality, sexual identity formation and sexual behavior that are either partially or entirely unsupported by psychological research. These assumptions are problematic as they undermine the validity of the asylum process and put vulnerable individuals at risk of severe harm. The challenges are aggravated in the cross-cultural context of asylum determinations, where applicants from different countries may manifest their sexual orientation in ways that deviate from Western expectations. We discuss the implications of our review’s findings for psychological research and asylum practice.

Introduction

With over 70 countries worldwide retaining laws that criminalize same-sex relations (Human Dignity Trust, Citation2021), violence against sexual minorities is an enduring and unfortunate reality in many parts of the world. Even when these laws do not exist, sexual minorities in many countries face ostracism, discrimination and serious harm amounting to persecution. It is therefore unsurprising that asylum claims based on sexual orientation have increased in recent years and are expected to continue rising in the future (International Commission of Jurists, Citation2016).

To meet the legal criteria for asylum set out in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (United Nations, Citation1951), an applicant must establish that they have a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country for reasons of race, nationality, religion, political opinion, or membership of a particular social group. The authorities in the applicant’s origin country must either be responsible for that harm or unable to protect the applicant from it. Although the Convention does not explicitly refer to sexual orientation as a reason for persecution, it is now widely accepted that sexual minorities qualify for asylum based on several grounds. They may be regarded as constituting a particular social group, and in some cases their persecution is religiously or politically motivated (Dustin & Ferreira, Citation2021; UNHCR, Citation2012). Once granted protection, recognized refugees are entitled to a number of human rights in the host country, which may include access to gainful employment, social security, and public education. Most fundamentally, host governments are prohibited from returning refugees to a country where they would be at risk of harm (United Nations, Citation1951).

There are several reasons why an asylum application may be unsuccessful. The applicant can fail to establish that their risk of harm is serious enough, or that the persecution they fear is linked to one of the five Convention grounds (United Nations, Citation1951). Increasingly, however, asylum-seekers are rejected because a central aspect of their claim is disbelieved (e.g. Bohmer & Shuman, Citation2007). This is concerning, given that applicants are only required to show they have a reasonable likelihood of facing harm in their countries, and they should enjoy the benefit of the doubt regarding aspects that cannot be proven with certainty (UNHCR, Citation2019). In recent years, scholars have described a ‘culture of disbelief’ in asylum decision-making (e.g. Jubany, Citation2017), which they attribute to migration policies geared towards border control and securitization. Bohmer and Shuman (Citation2018) have further observed that the legal demands of the asylum system limit the range of asylum narratives that officials consider believable and warranting protection. This can, in some cases, compel applicants with legitimate claims to ‘bend the truth’ and embellish their stories for fear of being disbelieved. As the authors argue, such strategies to secure necessary protection that result from the growing doubt regarding asylum narratives should be distinguished from deliberate attempts to submit fraudulent claims.

Whereas applicants’ claims are heavily examined throughout the asylum process, officials’ interviewing and decision-making strategies are rarely submitted to similar scrutiny. Given the importance of preserving the integrity of the asylum process – to the benefit of both the applicant and the host society – it is crucial to ensure that officials use methods that are evidence-based to minimize subjectivity and arbitrariness in their credibility assessments (see Kagan, Citation2003), with the aim to avoid false negative and false positive asylum decisions.

Credibility assessment in asylum procedures

In asylum procedures, credibility assessment is the process of collecting evidence about an applicant’s claim (i.e. their oral testimony and any supporting evidence) and determining which material facts to accept as credible (UNHCR, Citation2013). These facts are generally related to the applicant’s identity, place of origin, and experiences. Credibility assessment is central to the asylum decision, because facts that are considered credible are the basis for determining whether someone is likely to face future persecution (Kagan, Citation2003; UNHCR, Citation2013). As asylum-seekers are rarely able to provide external evidence (e.g. documentation) to support their claims, evaluating the credibility of their statements is a necessary step of the asylum decision-making process.

For several reasons, credibility assessment is often described as one of the most complex and psychologically challenging aspects of asylum adjudication for decision-makers (e.g. Dowd et al., Citation2018; Gyulai, Citation2013; Kagan, Citation2003; UNHCR, Citation2013). First, existing guidelines do not provide exact instructions about how to evaluate the credibility of the evidence presented (Gyulai, Citation2013). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recommends using four indicators to evaluate applicants’ statements: detail and specificity, internal consistency (i.e. within the applicants’ statements), external consistency (i.e. with other people’s statements and country information), and plausibility (UNHCR, Citation2013). Research on how autobiographical memory is encoded, stored, and retrieved has, however, contested the validity and reliability of these indicators (e.g. Herlihy et al., Citation2002), especially when assessing testimonies from trauma survivors (Memon, Citation2012). Scholars have argued that vague testimonies do not diagnostically indicate deceit, because the limits of memory retention, cultural differences in communication, and the presence of an interpreter can all influence the amount of information applicants provide (e.g. van Veldhuizen, Citation2017). In the absence of empirical support for more accurate credibility indicators, however, officials continue to rely on these criteria in their assessments.

Recent studies analyzing written asylum decisions have shown that officials make assumptions about human psychology that lack evidential support (Dowd et al., Citation2018; Herlihy et al., Citation2010; Skrifvars et al., Citation2021). For example, officials assume that persecuted asylum-seekers will always leave their countries at the earliest possible time, that they will be knowledgeable about the host country’s asylum procedures, and that their accounts of persecution will be free from minor inconsistencies. These studies point to a need for officials conducting credibility assessments to engage with psychological research on trauma, memory and human displacement.

Finally, asylum officials often work within strict time constraints and are exposed to accounts of traumatic events that took place in distant countries. Over time, they may experience compassion fatigue, that is, a reduced capacity to empathize with asylum-seekers due to repeated exposure to traumatic narratives (see e.g. Guhan & Liebling-Kalifani, Citation2011; Posselt et al., Citation2020). This may harden them to asylum-seekers’ stories (Baillot et al., Citation2013; Bohmer & Shuman, Citation2007) and interfere with their ability to attend to each individual credibility assessment objectively and impartially. Further, an applicant may have embellished some part of their claim (e.g. their involvement in an organization supporting sexual minorities) but still be credible on other facts (e.g. a previous arrest due to same-sex relationships). Officials should ensure that a negative finding about one fact does not overly influence their assessment of another, independent part of the claim. To safeguard against subjective decisions based on intuition, UNHCR (Citation2013) has highlighted the importance of asylum officials clearly justifying the reasoning behind their credibility findings, especially when these are not in the applicant’s favor.

Assessing the credibility of asylum claims based on sexual orientation

The difficulties of assessing credibility may be especially pronounced when asylum-seekers’ claims are based on their sexual orientation (e.g. Berg & Millbank, Citation2009; Greatrick, Citation2019). First, applicants may be unaware that sexual orientation is a legitimate reason for seeking asylum (Andrade et al., Citation2020), which can delay or altogether prevent their disclosure of relevant facts, to the detriment of the outcome of their claim. Second, as sexual orientation is not an overt and directly observable trait (Hanna, Citation2005; Tskhay & Rule, Citation2013), applicants need to personally reveal their identity to establish the claim (Millbank, Citation2009a). Yet, like other categories of applicants, including survivors of sexual violence or human trafficking, they may feel guilt and shame in disclosing sensitive details in a stressful judicial setting to an official (e.g. Berg & Millbank, Citation2009; Choi, Citation2010) and an interpreter from their own community (e.g. O’Leary, Citation2008; Raj, Citation2013). This is particularly likely if applicants have had to conceal their sexual identity, experience internalized homophobia (Hersh, Citation2015; McDonald, Citation2014) or have doubts over interview confidentiality (Mulé, Citation2020). Finally, owing to the internal nature of their claims, sexual minorities are even less likely than those claiming persecution based on their political activities or ethnic belonging to support their claim of group membership through independent evidence (Berg & Millbank, Citation2009).

From the official’s perspective, claims based on sexual orientation require them to delve into matters that are often beyond their area of expertise. In the absence of adequate guidelines, training, and expertise, any unfounded assumptions officials hold about sexual minorities might undermine the accuracy of their decisions. They may, for example, rely on stereotypes about applicants’ demeanor (Millbank, Citation2009b) or pose questions about intrusive details (Topel, Citation2017) which not only violate applicants’ rights to privacy and dignity, but also have limited evidential value for decision-making. Troublingly, recent evidence indicates these problems are still prevalent worldwide (e.g. Jansen, Citation2019; Jansen & Spijkerboer, Citation2011; Topel, Citation2017), with some studies even suggesting that claims based on sexual orientation arouse more suspicion than applications based on other grounds (e.g. Bohmer & Shuman, Citation2018). Finally, although an applicant might still qualify for asylum if their account of persecution raises credibility concerns, Millbank (Citation2009b) has argued that, in contrast, disbelieving one’s self-identification within a group ‘will almost always doom the claim to failure’.

The need for more psychological research

The field of legal psychology has much to offer with respect to improving investigative interviewing and reducing the influence of cognitive bias in various fields of judicial decision-making. Despite this, only recently have legal psychologists begun paying attention to asylum procedures, focusing on two strands of research. The first strand has examined factors influencing how asylum-seekers present their claims – that is, ‘estimator variables’ over which the asylum authority has no control – such as post-traumatic stress disorder (Rogers et al., Citation2015), experiences of sexual violence (Bögner et al., Citation2007), and the limits and variation of human memory (e.g. Cohen, Citation2001). The second strand has focused on parameters within the control of the asylum authority, or ‘system variables’. These include the type and style of questions officials ask (e.g. Skrifvars et al., Citation2020), the accuracy of indicators to assess the credibility of a claim (e.g. Maegherman et al., Citation2018), and the validity in testing applicants’ knowledge of places to verify their provenance (van Veldhuizen et al., Citation2017).

To date, this growing body of research has investigated asylum determinations in general, while overlooking how officials evaluate claims related to applicants’ identities and group membership. Against this backdrop, little is known about the psychological issues underlying credibility assessment of asylum claims based on sexual orientation.

The current study

The purpose of this narrative review of the literature was to identify patterns in officials’ credibility assessments of asylum claims based on sexual orientation, and critically analyze these practices against established psychological knowledge. A second objective was to discuss the implications of our findings for psychological research and asylum practice.

Methods

Search strategy

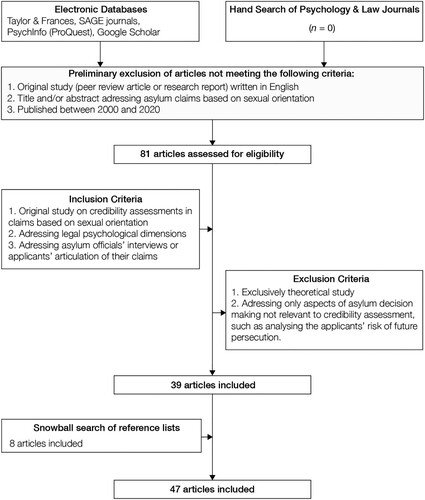

We searched for relevant publications in legal and social science databases, namely Taylor & Francis, SAGE Journals, PsycInfo (ProQuest), HeinOnline, and Google Scholar. To locate articles at the interface between psychology and law, we hand-searched several legal psychology journals from 2000 onwards: Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling; Legal and Criminological Psychology; Behavioral Sciences and the Law; Psychology, Crime and Law; Psychiatry, Psychology and Law; Psychology, Public Policy, and Law; Law and Human Behavior; and Applied Cognitive Psychology. We found 6 articles pertaining to asylum interviewing and decision-making. However, as none of these articles addressed claims based on sexual orientation, we excluded them from our analysis.

Through the database search, we identified 81 potentially relevant publications from the disciplines of law, sociology, geography, anthropology, among others. We assessed each article against a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible publications had to be peer-reviewed articles or research reports analyzing credibility assessment in asylum claims based on sexual orientation. We included articles based on several methodologies: analysis of interview transcripts and case decisions, surveys, as well as interviews with officials, lawyers, and asylum-seekers. Although the Refugee Convention came into force in 1951, the recognition of sexual minorities as refugees only dates to the mid-1990s (Millbank, Citation2009b). We therefore selected the period from 2000 to 2020 as our timeframe, with the aim to review sufficiently recent trends on credibility assessment in these cases. To obtain an overview of asylum practices worldwide, we did not impose restrictions on the papers’ geographical scope.

Because our aim was to analyze asylum practices, studies that focused only on theoretical debates related to this topic, especially in the fields of political science or anthropology, were eliminated from consideration. Moreover, as our thematic focus was on credibility assessment, we excluded articles that addressed other aspects of asylum decision-making, such as assessments of asylum-seekers’ risk of future persecution. below illustrates our search strategy.

Included studies

By applying these selection criteria and conducting a snowball search of reference lists, we obtained a final sample of 47 included manuscripts. Studies reporting about asylum decision-making in common law traditions (i.e. the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and the United States) were predominant in our sample. A smaller number of studies analyzed European asylum practices. The included articles varied greatly in terms of their disciplines, materials, research aims, and sample sizes, but all were based primarily on qualitative research methods. Only a handful of studies analyzed random samples of asylum casefiles obtained directly from asylum authorities. Other studies were based on legal analyses of publicly available case law, as well as surveys and interviews with asylum-seekers, officials, and lawyers.

Because the included manuscripts varied considerably with respect to methods, we reviewed them narratively rather than systematically. Our analysis consisted in identifying patterns in officials’ credibility assessments and critically assessing them against established knowledge in psychology.

Results

Here, we review and analyze four predominant themes present in the literature: (1) the prevalence of credibility issues raised concerning applicants’ sexual orientation; (2) officials’ assumptions about sexual minorities’ identity formation, behavior, and experiences; (3) officials’ criteria for evaluating applicants’ testimonies and supporting evidence; and (4) strategies asylum-seekers are compelled to adopt when presenting their claims.

Prevalence of credibility issues raised regarding applicants’ sexual orientation

Officials’ frequent mentions of credibility issues regarding applicants’ sexual orientation is an important theme in the recent literature. In earlier studies, it was reported that applicants were commonly denied asylum based on the reasoning that they could simply conceal their sexual orientation in their home countries to avoid harm. After high courts in various countries ruled that this ‘discretion requirement’ was at odds with the principles of asylum law (X, Y, and Z v. Minister voor Immigratie en Asiel, Citation2013), researchers expected an increase in sexual minorities’ positive asylum outcomes (Millbank, Citation2009a). This expectation did not materialize. Instead, officials in several countries began to refuse asylum based on the reasoning that applicants’ claims regarding their sexual orientation were not credible (see Gustafsson Grønningsaeter, Citation2017 on Norway; Jansen, Citation2019 on The Netherlands; Jansen & Spijkerboer, Citation2011 on Europe; Millbank, Citation2009a on the United Kingdom and Australia). highlights the growing prevalence of credibility issues raised concerning applicants’ sexual orientation, as reported in the literature.

Table 1. Reported percentages of cases where credibility issues are raised.

In an analysis of 267 casefiles in The Netherlands, asylum-seekers’ claims regarding their sexual orientation were more commonly disbelieved when their home countries had laws criminalizing same-sex activity (Jansen, Citation2019). When no such laws existed, applicants’ claims regarding their sexual orientation were more commonly believed, but they were rejected because the harm they feared was not considered well founded. A tentative explanation is that the risks for sexual minorities in countries criminalizing them were considered so severe, that accepting their sexual orientation as credible would immediately lead to granting asylum. To avoid this, asylum officials might instead have chosen to strategically disbelieve their claims.

Collectively, the findings suggest that once other obstacles, such as discretion requirements, are eliminated, negative credibility findings are a very commonly cited reason to reject asylum-seekers’ claims based on sexual orientation. It is unclear, however, whether the increase in credibility issues stems from an explicit motivation (e.g. to limit the number of successful applications), implicit cognitive processes, or a combination of these factors.

Assumptions about sexual minorities

The prevalence of doubt or disbelief concerning applicants’ identities raises the question of what officials consider a credible claim. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that stereotypical assumptions about sexual minorities influence officials’ assessments (Bennett & Thomas, Citation2013; Choi, Citation2010; Cory, Citation2019; Hinger, Citation2010; McDonald, Citation2014; Topel, Citation2017). In an analysis of 117 cases, Vine (Citation2014) identified stereotypes surrounding sexual minorities’ behavior and lifestyle in one fifth of all transcripts. These findings have been echoed in other contexts, including countries with a positive reputation for the treatment of sexual minority asylum-seekers (e.g. Dhoest, Citation2019; Gustafsson Grønningsaeter, Citation2017). Recurring assumptions include expectations that applicants will show they are familiar with LGBTQ+ culture and have attended pride marches in the asylum country (Bennett & Thomas, Citation2013; Choi, Citation2010; Hersh, Citation2015; McDonald, Citation2014). Several authors have pointed out that these assumptions stem from officials’ expectations about the behavior of Western gay, male, white, and middle class individuals, and do not account for asylum-seekers’ experiences of racial prejudice, poverty, and social exclusion (e.g. Dhoest, Citation2019; Greatrick, Citation2019; Tschalaer, Citation2020).

Remarkably, officials also made assumptions about asylum-seekers’ societies of origin, which they regarded as entirely hostile towards sexual minorities (Dhoest, Citation2019; Hedlund & Wimark, Citation2019; Tschalaer, Citation2020). Hedlund and Wimark (Citation2019) reported that this led them to disbelieve applicants who claimed their male relatives had reacted positively when they disclosed their sexuality to them. There is evidence of a broad expectation among officials that applicants must be very critical of their origin societies and describe a sense of liberation in their new country. This expectation is said to reflect the belief that Western cultures are progressive in their treatment of sexual minorities while other nations are unanimously homophobic (e.g. Dhoest, Citation2019; Hedlund & Wimark, Citation2019; Koçak, Citation2020; Morgan, Citation2006; Tschalaer, Citation2020). Many authors were, in fact, critical of officials’ failure to acknowledge that queer persons in the West who also belong to other minority groups (e.g. based on their race or disability status) can face significant prejudice and not be afforded equal treatment (Cory, Citation2019; Hedlund & Wimark, Citation2019; Hertoghs & Schinkel, Citation2018; Morgan, Citation2006; Mulé, Citation2020; Murray, Citation2016; Tschalaer, Citation2020).

Shifting focus from sexual behavior to sexual identity

Questions about applicants’ sexual practices were reported as a common feature in earlier credibility assessments regarding sexual orientation (Dawson & Gerber, Citation2017; Gray, Citation2010; Jansen & Spijkerboer, Citation2011; Raj, Citation2013; Yoshida, Citation2013). Even after high courts in several countries banned questions that breach applicants’ rights to privacy and human dignity (A, B, C v Staatssecretaris van Veiligheid En Justitie, Citation2014), studies have highlighted the continued presence of interview questions that are either overtly explicit (Bennett & Thomas, Citation2013; Jansen, Citation2019) or invite a sexually explicit response (Vine, Citation2014). Worse still, asylum-seekers have been disbelieved because their responses to sexually intrusive questions were evasive (Jansen & Spijkerboer, Citation2011). Worth noting is that for investigative interviewing purposes, questions about sexual practices are likely to make many asylum-seekers uncomfortable, and risk leading even truthful applicants to give vague, unspecific, and avoidant statements (Jansen & Spijkerboer, Citation2011). For credibility judgments, the probative value of sexually explicit questions is thus highly questionable.

In later years, however, officials have recently begun moving away from asking about sexual acts, focusing their assessments on applicants’ thoughts and feelings instead (see Akin, Citation2015; Asanovic, Citation2018; Gustafsson Grønningsaeter, Citation2017; Jansen, Citation2014; Jansen, Citation2019). Recent studies have noted that officials expect asylum-seekers to describe a linear process of sexual identity development, beginning with shame and ending in self-acceptance (e.g. Asanovic, Citation2018; Berlit et al., Citation2015; Gustafsson Grønningsaeter, Citation2017; Hertoghs & Schinkel, Citation2018; Jansen, Citation2014). Moreover, it is rarely sufficient that applicants describe same-sex attractions to be found credible; they must establish that their sexuality is an important dimension of their self-concept (e.g. Gustafsson Grønningsaeter, Citation2017). According to some authors, officials’ assumptions demonstrate the influence of psychological stage models of identity formation (e.g. Berg & Millbank, Citation2009; Dawson & Gerber, Citation2017), the most prominent one being the Cass (Citation1979) model (for information on stage models, see Eliason & Schope, Citation2007). The Cass model suggests that sexual identity develops over six discrete stages: identity confusion, comparison, tolerance, acceptance, pride, and identity synthesis. Individuals move sequentially from one stage to the next, experiencing progressively higher levels of psychological wellbeing. In the final stage (identity synthesis), they settle on an identity label that remains stable over time. Ultimately, people’s sexual orientation becomes one of many facets of their identity, rather than being their main defining characteristic (Cass, Citation1979).

Despite the influence this stage model of sexual identity development might have on asylum officials’ assumptions, research in human sexuality has challenged the model’s validity across different populations and time frames (e.g. Horowitz & Newcomb, Citation2001; Savin-Williams, Citation2011). For example, in a 10-year longitudinal study, Diamond (Citation2000) found a high degree of sexual fluidity among women, with more than half of women reporting at least one change in their identification. Other studies have highlighted behavior/identity mismatches among sexual minorities (Malcolm, Citation2008; Schick et al., Citation2012), challenging the notion that people seek a label only to match their choice of partners (e.g. Cass, Citation1979).

For the asylum context, the most relevant criticism of stage models is that they fail to account for cross-cultural differences (for information on the model’s limited generalizability across cultures, see Eliason & Schope, Citation2007). Several studies have argued that applying stage models to assess the credibility of non-Western asylum-seekers’ testimonies could lead to inaccurate judgments (e.g. Akin, Citation2017; Berg & Millbank, Citation2009; Dawson & Gerber, Citation2017). Firstly, this is because they promote the stereotype that sexual minorities, regardless of their cultural background, will invariably feel ashamed about their sexuality. Consistent with this criticism, Jansen (Citation2019) found that asylum-seekers who did not report initially having had negative feelings about their sexuality were often disbelieved. Secondly, stage models have been criticized for emphasizing the ‘coming out’ process, while overlooking how culture, religion, and social norms may impact the decision to disclose (see Eliason & Schope, Citation2007).

Assumptions about asylum-seekers’ relationships

In line with the expectation put forward by stage models that sexual identity development ends in self-acceptance, studies have found that officials assume genuine asylum-seekers will openly manifest their sexual orientation in the asylum country, by engaging with LGBTQ+ culture and having same-sex relationships (e.g. Hersh, Citation2015; Millbank, Citation2009b; Morgan, Citation2006; Southam, Citation2011). Because same-sex relationships provide tangible evidence of applicants’ sexuality, at least three studies noted a positive association between accounts of such relationships and positive credibility findings (Connely, Citation2014; Hedlund & Wimark, Citation2019; Hersh, Citation2015). However, the authors reported that the credibility of these relationships was often judged based on their underlying motivation. Accordingly, one applicant’s sexual orientation was not considered genuine because he had a same-sex relationship primarily for material gain (Gustafsson Grønningsaeter, Citation2017). Officials have also discounted relationships that were only motivated by sexual attraction, rather than romantic feelings (e.g. Hersh, Citation2015). According to Hersh (Citation2015), these expectations reflect unsuitable comparisons to heterosexual relationships, as sexual minority asylum-seekers are often unable to validate their relationships using the same markers available to those in heterosexual relationships (e.g. public recognition, engagement, and marriage).

Taken together, the literature indicates that credibility assessments are based on a restrictive view of how sexuality is expressed, by relying on narrow constructs that do not apply to all sexual minorities, let alone those with diverse cultural backgrounds and other dimensions of vulnerability linked to their nationality, race, religion, and/or socioeconomic status. This is particularly problematic in light of recent psychological evidence emphasizing the fluid, non-linear development of human sexuality.

Assumptions about bisexuality

The studies reviewed suggest that gay men submit the majority of asylum claims based on sexual orientation, whereas women are a largely invisible minority within the minority (Dawson & Gerber, Citation2017; Dustin, Citation2018; Jansen & Spijkerboer, Citation2011). Indeed, as we highlight in , asylum applications from both lesbian and bisexual applicants are comparatively rare, and these applicants are also less likely to be successful (Dustin, Citation2018; Millbank, Citation2009b; Rehaag, Citation2008). Notably, two authors attributed their less favorable asylum outcomes to there being fewer stereotypes of them, making it harder for asylum-seekers to match officials’ preconceptions (Dustin, Citation2018; Rehaag, Citation2008).

Table 2. Reported distributions of gender, sexual orientation and asylum decision outcomes.

Bisexual asylum-seekers’ challenges in claiming asylum were the focus of two studies (Rehaag, Citation2008, Citation2009). The author found that the applicants’ bisexuality was especially likely to raise doubts when they had a history of heterosexual relationships. Those who had same-sex relationships, on the other hand, were seen as more similar to gay applicants and had more positive outcomes (Rehaag, Citation2009). Strikingly, several asylum decisions referred to bisexual people as being ‘confused’ about their sexuality (Rehaag, Citation2008). This observation in the asylum context mirrors research in psychology, which has found that when bisexual informants disclose their sexuality to others, they report identity denial (i.e. having their group membership questioned or rejected) more often than lesbian and gay respondents (e.g. Garr-Schultz & Gardner, Citation2019). Garr-Schultz and Gardner (Citation2019) showed that bisexual participants experience identity denial from both straight and gay people. Moreover, they found that identity denial targeting bisexual people manifests in one of two ways: disbelief that the person actually belongs to the group (i.e. ‘the individual is not bisexual’) or disbelief that the group exists altogether (i.e. ‘bisexuality is not real’) (Garr-Schultz & Gardner, Citation2019). The second assumption, which was prevalently reported in the studies we reviewed, might be more difficult to challenge because it stems from lay conceptions of bisexuality being a myth or a phase that one outgrows. Overall, the present review shows that a tendency to deny bisexual identity, and more generally, to base asylum decisions on binary notions of human sexuality, may lead to less successful outcomes for bisexual asylum-seekers.

Assumptions about religious and sexual identity conflict

Sexual minority asylum-seekers face higher evidentiary burdens when they claim to be religious. According to several studies, officials found it implausible for them to maintain religious beliefs that considered their sexuality as sinful (Asanovic, Citation2018; Greatrick, Citation2019; Jansen, Citation2019; Millbank, Citation2009b; Yoshida, Citation2013). These beliefs are described as prejudicial, as they underlie a blanket assumption about how religious individuals, and in particular Muslims, treat individuals of diverse sexual orientations (Dhoest, Citation2019; Tschalaer, Citation2020). This was reflected, for example, in the following interview question posed in The Netherlands: ‘Homosexuality is at odds with your faith. What is the reason that you don’t turn away from your faith, but that you continue to pray and go to the mosque where you are among people who totally disapprove of homosexuality?’ (Jansen, Citation2019). Further, the present review revealed two recurring psychological assumptions about sexual minority asylum-seekers. Firstly, they are expected to describe an internal conflict between their religion and sexuality (e.g. Jansen, Citation2019; Yoshida, Citation2013); secondly, they need to show they have adopted strategies to reconcile this conflict (e.g. Asanovic, Citation2018).

Psychological research partially supports officials’ assumptions; in numerous survey-based studies, sexual minorities whose religious communities condemn same-sex activity have described a conflict between their religious and sexual identities (e.g. Pietkiewicz & Kołodziejczyk-Skrzypek, Citation2016; Schuck & Liddle, Citation2001). The body of literature on this topic is dominated by Festinger’s (Citation1957) cognitive dissonance theory, according to which people who hold conflicting beliefs or identities experience discomfort that leads them to change their behavior or cognitions. In a review of the psychological literature on sexual orientation/religious identity conflict, Anderton et al. (Citation2011) highlighted three main strategies that participants used to manage this conflict. Participants reported either changing their environment (e.g. by leaving their religious communities), modifying their behavior (e.g. by avoiding same-sex activity or increasing their religious practice), or adding new cognitive elements (e.g. by reinterpreting scripture, or focusing on positive religious verses). The strategy of adding new cognitive elements led some participants to engage in benevolent reappraisal, that is, the belief their creator was compassionate and would accept their sexuality. In the original studies reviewed here, however, when asylum-seekers justified their religious views by explaining that ‘God will forgive me’ or ‘God made me like this’, these were not seen as convincing resolution strategies and could lead officials to disbelieve their claimed sexuality (e.g. Asanovic, Citation2018). Instead, asylum officials were more inclined to believe applicants who had radically changed their environment or cognitions, for example, by leaving their religious community or rejecting previously held beliefs.

Importantly, in a study on sexual identity/religious identity conflict, Anderton and colleagues (Citation2011) found that some sexual minorities did not adopt any conflict resolution strategies at all and instead shifted between these two identity facets depending on the context, without trying to integrate them. Other participants denied experiencing any conflict between their religion and sexuality altogether. This concerned individuals who did not attach importance to their religion or belonged to religious groups that were tolerant of LGBTQ+ persons (Anderton et al., Citation2011). Another study has suggested that sexual minorities who prioritize their personal convictions rather than religious authorities’ teachings experience less internalized homophobia (Harris et al., Citation2008). Together, these empirical findings in psychology challenge the validity of evaluating asylum-seekers’ credibility by expecting them to always report a religious/sexual identity conflict and resolve it in specific ways (e.g. by either leaving their communities or rejecting earlier beliefs).

Criteria for evaluating applicants’ statements and supporting evidence

A third prominent theme in the literature concerns the criteria officials use to evaluate applicants’ oral testimonies and their supporting evidence.

Evaluation of applicants’ testimonies

An abundance of evidence suggests that asylum officials apply the UNHCR’s recommended credibility indicators overly rigidly, for example by expecting applicants to provide unreasonably detailed and internally consistent accounts of their sexual orientation (e.g. Choi, Citation2010; Connely, Citation2014; Hedlund & Wimark, Citation2019; Hersh, Citation2015; Millbank, Citation2009b; Scavone, Citation2013). According to some studies, minor discrepancies related to peripheral details, such as names of LGBT organizations, could be the sole basis to challenge the credibility of applicants’ claims (Scavone, Citation2013; Yoshida, Citation2013). As stated earlier, psychological research challenges the validity and reliability of these indicators. Several authors have noted that these indicators may be even less reliable when assessing claims based on sexual orientation (see for an outline of the main arguments challenging the reliability of each credibility indicator). For example, applicants who have been forced to conceal their sexuality for most of their lives may find it difficult to provide extensive details about it in the asylum interview (Berg & Millbank, Citation2009). Besides a rigid application of these indicators, evidence also suggests that they are used inconsistently: although accounts have been disbelieved because they are described as vague, giving too many details can equally lead to a finding that the claim is rehearsed (McDonald, Citation2014).

Table 3. Challenges to the validity and reliability of indicators used to assess the credibility of asylum claims based on sexual orientation.

Officials also seem to give considerable weight to the degree to which they find an applicant’s past behavior as plausible or rational. A recurring example was that of judging someone’s same-sex relationships in a homophobic community as ‘too risky to be true’ (see e.g. Asanovic, Citation2018; Gray, Citation2010), although such relationships, of course, can occur. It was also considered implausible that an applicant would claim to belong to a sexual minority while having a spouse of the opposite sex (Dawson & Gerber, Citation2017; Yoshida, Citation2013). Asylum scholars heavily contest these ‘plausibility assessments’ (Choi, Citation2010; Hersh, Citation2015; LaViolette, Citation2015; Millbank, Citation2009b; Yoshida, Citation2013) because people may display a wide range of behaviors in response to various situations. Hence, judging whether someone’s behavior is rational depends heavily on the evaluator’s personal background, experiences and prior beliefs (LaViolette, Citation2015; Millbank, Citation2009b).

Late disclosures (i.e. not disclosing one’s sexual orientation in the original statement) are another commonly reported aspect of credibility assessments in claims based on sexual orientation (e.g. Berg & Millbank, Citation2009; Choi, Citation2010; Connely, Citation2014). There are many valid reasons why truthful asylum-seekers might delay disclosing their sexuality, including shame, fears of being outed, or not knowing that sexual orientation can be the basis of a claim for refugee protection (Morgan, Citation2006; Mulé, Citation2020). In the studies we reviewed, the effects of delayed disclosure on asylum outcomes were mixed. Although one large-scale, longitudinal study did not identify delayed disclosure as a major barrier to asylum (Millbank, Citation2009b), other studies found that late claims have been held against applicants who showed no other indications of lie-telling (Asanovic, Citation2018; Jansen & Spijkerboer, Citation2011).

We also analyzed officials’ own descriptors of their reasoning, reported in the literature (see ). Collectively, these descriptors reveal a high degree of arbitrariness in the decision-making. Asylum judges quoted in one study stated that, to be considered credible, a story must ‘ring true’; that is, they believe a credible account of one’s sexual orientation will be immediately apparent, and that officials do not need to conduct a thorough assessment to identify it (Millbank, Citation2009b). Others have stated that they rely on instinct and improvisation when conducting credibility assessments (Akin, Citation2015). Even more problematic, officials regularly cited applicants’ demeanor, mannerisms, appearance, and emotional displays as important factors in decision-making (Hanna, Citation2005; Hinger, Citation2010; Morgan, Citation2006; Scavone, Citation2013).

Table 4. Descriptors of asylum officials’ decision-making process.

Other studies document appearance-related stereotypes in officials’ credibility assessments. Hanna (Citation2005) found that gay applicants in the United States were routinely disbelieved because they were considered too masculine, while similar findings were made about lesbians in the United Kingdom who were rejected because their appearance was too feminine (Bennett & Thomas, Citation2013). These observations suggest that officials subscribe to an implicit gender inversion stereotype, which leads them to assume that gay men and lesbian women share physical and behavioral characteristics with straight people of the opposite sex (see e.g. Cox et al., Citation2016). Another explanation might be the common mistake of conflating sexual orientation and gender identity, which is well documented in psychological research (see Mohr et al., Citation2013). Finally, Morgan (Citation2006) has pointed out that stereotypes of effeminate gay men may overlap with stereotypes of hypermasculinity in men with immigrant backgrounds. The co-existence of these two identity categories in sexual minority asylum-seekers, and the conflict between the stereotypes attached to them, risk leaving such applicants with no room to have their claims validated by the asylum system (Morgan, Citation2006).

Evaluation of supporting evidence

Because asylum-seekers are rarely able to present external evidence to establish their sexual orientation, decisions regarding their claims are in most cases based entirely on their oral testimony. Despite the existence of guidelines stating that applicants’ self-identification as belonging to a sexual minority should be taken as an indication of truthfulness (UNHCR, Citation2012), our review illuminates a tendency to doubt asylum-seekers’ oral accounts when they present no other evidence to back up their claims (e.g. McGhee, Citation2000; Raj, Citation2013). This was reflected in a study quoting one judge’s description of sexual orientation narratives as ‘easy to make and impossible to disprove’ (Millbank, Citation2009b). Two studies further suggested that, in the decision-making, missing evidence is given more weight than available evidence (Raj, Citation2013; Scavone, Citation2013).

Faced with these expectations, applicants make efforts to present photographs, letters from organizations and witness statements as supporting evidence (Murray, Citation2016; Raj, Citation2013). Paradoxically, when asylum-seekers do provide evidence, these are often dismissed as fabricated to support a claim that is not credible (Asanovic, Citation2018; Berg & Millbank, Citation2009; Murray, Citation2016). Two studies noted a tendency for the same piece of evidence to be evaluated either favorably or unfavorably, at the individual official’s discretion (Jansen, Citation2019; Yoshida, Citation2013). As a result, applicants are unable to determine how supporting evidence will affect their asylum outcome; failing to present any supporting evidence can be detrimental to the outcome of their application, while submitting evidence might also create more possibilities to doubt the claim.

Over the years, a wide range of evidence has been presented by asylum-seekers and their lawyers or requested by officials in sexual orientation claims, some of which is highly controversial. In a large-scale report on European practices, Jansen and Spijkerboer (Citation2011) found evidence of phallometric testing, which invasively assesses physiological arousal to pornographic stimuli (for example, penile erection to images of men to assess homosexuality in men). In eight countries, the court or representing lawyers requested other types of medical and projective personality tests to establish applicants’ credibility. Aside from their obviously intrusive character, the probative value of these tests is undermined by the fact that no medical or psychological test can reliably ascertain someone’s sexual orientation (De Bruyckere, Citation2018; Ferri, Citation2018; Walker, Citation2000).

Asylum-seekers’ articulation of their claims

Applicants’ ways of articulating their claims, and in particular their choice of words and expressions, can subject them to negative evaluations based on officials’ impressions that their narratives are incompatible with Western norms and values. Particularly, when officials perceive applicants’ formulations as derogatory or disparaging of sexual minorities, this is often a reason for them to discount their claims (e.g. Berg & Millbank, Citation2009; Greatrick, Citation2019; Hedlund & Wimark, Citation2019; Jansen, Citation2019). This is, for example, a risk that Syrian asylum-seekers run when they refer to themselves as lutti, a term describing gay men in Arabic that arouses suspicion among officials (Greatrick, Citation2019). Scholars have been critical of officials’ perceived cultural superiority in their judgments of applicants’ statements, while arguing that they fail to account for linguistic differences, variations in cross-cultural understandings of sexuality, and experiences of internalized homophobia (e.g. Greatrick, Citation2019; Hersh, Citation2015).

Analyzing the asylum process from the applicants’ perspective, several manuscripts have documented how applicants actively participate in the construction of their claims as well as the strategic choices they must make to secure protection (e.g. Akin, Citation2017; Bennett & Thomas, Citation2013; Connely, Citation2014; Dhoest, Citation2019; Greatrick, Citation2019; Tschalaer, Citation2020). For example, applicants weigh the risks and benefits of disclosing their sexual orientation, taking into account the personality, gender, and culture of the official and interpreter, as well as the degree to which they expect them to be receptive to the claim (e.g. Berg & Millbank, Citation2009). Interviewers’ interpersonal skills have also been cited as a barrier to disclosure (e.g. Bennett & Thomas, Citation2013), with one informant highlighting that ‘talking to a wall does not give you the confidence to show your emotions and tell your story’ (Vine, Citation2014). Those who expect officials to disbelieve their sexual orientation altogether even opt to articulate alternative claims, such as ones based on their political opinions (Raj, Citation2013).

Importantly, applicants who do disclose their sexual orientation report the pressure to fit Western notions of sexuality, even when these do not reflect their personal experiences (e.g. Akin, Citation2017; Bennett & Thomas, Citation2013). This entails expressing their sexuality more outwardly, by modifying their appearance, entering relationships, and participating in LGBTQ+ organizations, despite the risks of exclusion and harm within their own communities (e.g. Dhoest, Citation2019). These findings suggest that stereotypes about sexual minorities have at least two levels of influence in the asylum process. The first is their influence on asylum officials’ credibility judgments, highlighted above. The second level is asylum-seekers’ activation of meta-stereotypes –that is, their own beliefs about how officials view them – in their asylum interviews (for more information on meta-stereotypes, see Gómez, Citation2002). In other words, asylum-seekers might adjust their behavior to match asylum officials’ expectations.

Faced with asylum systems’ failure to account for diverse expressions of sexual orientation, asylum activists and support workers also reported the need to ‘coach’ applicants to frame their narratives in ways that are believable from a Western perspective. For example, they might feel compelled to encourage applicants to explicitly identify using LGBTQ+ labels rather than simply describing their attractions (Greatrick, Citation2019) or even to provide evidence of same-sex relationships (Raj, Citation2013).

To conclude, the strategies asylum-seekers adopt when articulating their claims have at least two adverse consequences: Firstly, applicants may feel compelled to adopt certain behaviors, even those they are uncomfortable with, at the expense of truth telling. It has been argued that confirming officials’ expected narratives may be an option only for the priviledged, educated few, who benefit from legal support, and have access to financial resources (Akin, Citation2017; Hedlund & Wimark, Citation2019; Tschalaer, Citation2020). Secondly, these strategies risk reinforcing officials’ unfounded assumptions and, in turn, further excluding applicants who express their sexuality differently (Akin, Citation2017). Thus, asylum practices seem to favor applicants whose claims about sexual orientation confirm a meta-stereotype, rather than truthful applicants who deviate from a given stereotype.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to review and analyze relevant psycho-legal issues in credibility assessments of asylum claims based on sexual orientation. Asylum procedures are one of the rare legal settings in which an individual’s claim of holding a specific identity or belonging to a particular social group (e.g. a sexual minority) is seldom accepted at face value by decision-makers. To determine whether an applicant meets the criteria for refugee status, officials must first evaluate the credibility of asylum-seekers’ claims regarding their sexual orientation, by conducting an asylum interview and a thorough assessment.

The current study revealed several concerns regarding the way asylum officials assess the credibility of sexual orientation claims in several countries. Firstly, asylum officials’ decisions are often based on assumptions about human sexuality that do not reflect the trajectories of asylum-seekers’ personal lives. As an example, an official may start with the assumption that a truthful gay asylum-seeker can reasonably be expected to abandon a religion whose teachings denounce same-sex relations. In the assessment that follows, the official may judge an applicant’s claim of being gay and religious as being inconsistent. Such a decision overlooks empirical research regarding how people address a perceived dissonance between two conflicting beliefs or cognitions.

Like the above example, most of the assumptions identified in the original studies were partially or entirely unsupported by recent psychological research regarding sexual fluidity, identity formation and the lived experiences of sexual minorities. In general, the less knowledgeable officials are about an applicant’s profile – as in the case of bisexual asylum-seekers – the more likely they seem to doubt their sexual orientation. Asylum-seekers thus appear to have greater chances of being believed by conforming to a given stereotype than by telling their true story, if the latter deviates from the official’s expectations. This also creates possibilities for fraudulent applicants to take advantage of officials’ narrow constructs of sexuality, for example, by describing their journey from internalized homophobia to pride and acceptance. Although this narrative may accurately reflect the experience of many asylum-seekers, those who continue to question their sexuality or who identify as belonging to a sexual minority without having a history of same-sex relationships risk being wrongfully deemed not credible. Current asylum assessments are thus both over- and under-inclusive, creating a dual risk of false negative and false positive decisions.

Officials’ excessive reliance on arbitrary criteria in decision-making was a concerning finding. Gay asylum-seekers who were viewed as ‘too masculine’ were often disbelieved about their sexuality, indicating that demeanor and appearance continue to influence officials’ judgements. This is at odds with guidelines warning against using non-verbal behavior to reach conclusions regarding credibility (see UNHCR, Citation2013). Credibility assessments should only be based on objective criteria, that is, evaluations of the applicants’ oral statements and their supporting evidence. Moreover, although applicants have a duty to present all the evidence at their disposal to substantiate their asylum claim, the present study revealed that corroborating evidence (e.g. letters from NGOs supporting sexual minorities) was often disregarded as unreliable. Not knowing whether a certain document or witness statement will help or hinder their case may make it difficult for asylum-seekers to fulfill their duty to be forthcoming.

Overall, the findings of the present study support broader descriptions of these procedures as an ‘asylum lottery’ (e.g. Spirig, Citation2018), because the decision outcome will largely depend on the individual official conducting the assessment.

Limitations

The current study presents some limitations that should be considered. First, the original studies we reviewed were heterogeneous in their disciplines, methods, research aims, and sample sizes. These variations prevented us from quantifying the breadth and frequency of the decision-making patterns identified. Studies based on casefile analysis, for example, were not directly comparable to those based on surveys or interviews with asylum lawyers. Moreover, certain studies drawing on interviews with different participants (e.g. asylum-seekers, lawyers, and asylum officials) may have presented a distorted image of asylum practices. For instance, asylum officials may have been influenced by social desirability bias and embellished their descriptions of how they conduct their assessments. Rejected asylum-seekers, on the other hand, might have focused disproportionately on the problematic aspects of their asylum process, overlooking the more positive practices.

The second cluster of limitations concerns the geographical scope of the original studies. Firstly, we reviewed original studies reporting on credibility assessment in countries whose legal systems, asylum policies, and asylum practices differ widely. Although we identified several commonalities across national asylum systems, any evidence-based recommendations should be refined to consider the institutional structure of the country’s asylum authority, their migration policies, and the broader sociopolitical context. Secondly, nearly all the studies we included focused on Western countries’ asylum practices, even though most of the world’s displaced people are hosted in Asia, Africa, and South America (UNHCR, Citation2021). This may be because sexual minorities often continue to be at risk of harm in countries where they seek asylum in these regions, making it more challenging to collect data regarding their applications. Because some assumptions identified in the present study were partially related to cultural differences, our findings may not extend to regions where the cultural backgrounds of the asylum officials and asylum-seekers are more similar. Future research should expand the knowledge base outside of Europe, North America and Oceania.

Finally, because of the difficulty of obtaining confidential asylum data, only a handful of studies were based on random samples of unpublished asylum casefiles (i.e. interview transcripts and asylum decisions) obtained from the asylum authorities. Most studies analyzed published case decisions. Of note, asylum decisions in some countries are only made publicly available when they present an unusual situation or a new decision-making approach, and thus, they are not representative of overall asylum practices. It is therefore only possible to draw tentative conclusions from studies analyzing small, unrepresentative samples.

Despite the methodological shortcomings, our review of the literature gives important insight about the psycho-legal issues in credibility assessments of asylum claims based on sexual orientation, to the benefit of both practitioners and researchers. One advantage of including studies based on surveys and interviews with asylum officials is that they provide information about decision-making factors that are not explicitly stated in the written asylum decisions. For example, some interviewed officials explained that they make credibility judgments based on their ‘gut feeling’, which contradicts established asylum guidelines (UNHCR, Citation2013). Analyzing written decisions alone would have obscured officials’ reliance on intuitive reasoning in their credibility assessments. In conclusion, the present study contributes to a small but growing body of knowledge on asylum practices in the field of psychology and law, providing avenues for future research and recommendations for asylum practitioners.

Recommendations for research and practice

The findings of this review have implications for empirical research in psychology and law as well as for asylum practice. Because the interview statements are evaluated as part of the credibility assessment, our recommendations concern both the asylum interviews and the subsequent assessments. In fact, in a study on Swedish asylum officials’ beliefs about deception, only 4 out of 10 surveyed officials reported that they wait until the end of the interview to judge the veracity of the asylum claim (Granhag et al., Citation2005). This means that more than half of the participants (60%) reported that they reach some conclusion about credibility before conducting a full and well-reasoned assessment. The aim of future research should be to aid asylum officials in eliciting accurate information from applicants with claims based on their sexual orientation, and reaching objective, reliable decisions about the credibility of their statements. This is especially important in claims lacking corroborative evidence regarding applicants’ sexual orientation. To avoid making judgments based on stereotypes about sexual minorities’ demeanor, asylum officials need to gain expertise in investigative interviewing and assessing credibility based on valid indicators.

Interviewing techniques

Guidelines on investigative interviewing in other legal contexts, such as interviews with witnesses and suspects of crimes, have repeatedly underlined the importance of asking open-ended questions (e.g. ‘You mentioned you were arrested. Please tell me more about that’.), which promote free recall and elicit more judicially relevant details than closed questions (e.g. ‘Were you arrested in 2018?’; Milne et al., Citation2008). These recommendations have also been adapted to the asylum context and reiterated in training manuals for asylum officials (e.g. European Asylum Support Office, Citation2014). From a deception detection perspective, open-ended questions are preferable because they elicit more details, and in turn more cues to assess the veracity of the account, than closed questions (Vrij et al., Citation2014). Finally, research has also shown that interviewers who are skilled at asking non-leading open questions show less evidence of confirmation bias in interviewing. This is because they ask fewer questions containing suggestive details the interviewee has not previously mentioned (Powell et al., Citation2012). For these reasons, asylum officials should strive to ask more open questions in their interviews with sexual minorities. Eliciting a free narrative through invitations (e.g. ‘Go on … ’) may give asylum-seekers the chance to talk while minimizing question content that reflects the officials’ preconceptions.

To our knowledge, only two studies have investigated whether the type of questions officials ask allow asylum-seekers to provide accurate and elaborate statements. Analyzing a Finnish and a Dutch sample of asylum interview transcripts, the studies found that asylum officials asked predominantly closed questions (Skrifvars et al., Citation2020; van Veldhuizen et al., Citation2018). Only one report reviewed in the present study investigated the frequency of question types in interviews with sexual minorities. Vine (Citation2014) found that 52% of the 112 transcripts contained only open questions, while the remaining transcripts were made up primarily or entirely of closed questions. These findings suggest an inconsistent application of the guidelines among interviewers. Future research could expand these findings by exploring whether asylum officials’ interviewing question style allows sexual minorities to provide elaborate and accurate statements. Moreover, since evidence of stereotypes regarding sexual minorities may already appear in the content of the questions, future studies could also investigate the most common themes asylum officials ask about in the interviews (e.g. development of sexual identity, reconciliation of sexual identity and religious beliefs).

Assumptions about sexual minorities

Further research is needed to corroborate the finding that asylum-seekers are more likely to be believed if they match Western stereotypes about sexual minorities. Previous studies on asylum decision-making have coded the assumptions officials make about asylum-seekers in their written decisions (Dowd et al., Citation2018; Herlihy et al., Citation2010; Skrifvars et al., Citation2021). These studies have identified several assumptions that were not in line with psychological science, including assumptions about the characteristics of a credible claim, the functioning of human memory, peoples’ behavior in the face of danger, and their expected knowledge about the asylum system. Future studies could replicate this methodology, focusing on assumptions regarding how people manifest their sexual orientation. This research could also investigate whether certain assumptions about sexual minorities correlate with positive and negative findings about asylum-seekers’ credibility.

Finally, the present study also has research implications beyond the field of psychology and law. Our study revealed a lack of empirical research regarding cross-cultural manifestations of sexuality. Existing theoretical models of sexual identity development are based almost exclusively on samples of Western gay men and therefore do not generalize across different populations (Berg & Millbank, Citation2009). Even within a uniform cultural group, these models are unlikely to capture the considerable individual variations in people’s formation of their sexual identity (Eliason & Schope, Citation2007). An ambitious research aim would thus be to expand the knowledge base on sexual minorities’ identity, behavior and experiences in diverse cultural contexts, and particularly in asylum-seekers’ countries of origin. This research could explore how religion, ethnicity, and prevailing social norms influence sexual behavior and identity formation. Bearing in mind the existing gaps in empirical research, asylum officials should be open to unfamiliar expressions of sexuality in asylum-seekers’ claims and refrain from immediately disbelieving applicants if their testimonies appear unusual from a Western perspective. To avoid applying blanket assumptions regarding sexual minorities, asylum officials are encouraged to critically consider how the multiple facets of an applicants’ identity (e.g. their racial and ethnic background, gender, nationality, and socioeconomic status) might shed light on their behavior and experiences. This practice would encourage more nuanced credibility assessments, which would avoid considering applicants’ sexual orientation in isolation and regarding all sexual minority asylum-seekers as a monolithic category.

Cognitive bias in decision-making

Some of our findings concerned how officials evaluate and integrate different pieces of evidence to reach a conclusion about the credibility of a claim. For instance, disregarding supporting evidence without justification or disbelieving applicants with delayed disclosure may be indicative of cognitive biases in decision-making. In these cases, a presumption of lie telling may have driven the decision-makers to seek out evidence confirming their initial hypothesis and disregard evidence that refutes it. These examples are consistent with confirmation bias, a decision-making heuristic leading people to interpret information in a way that supports their initial beliefs (Nickerson, Citation1998), found also in legal decision making (Lidén, Citation2018).

Although all humans are susceptible to errors when making complex decisions under uncertainty, research suggests that experts may be even more prone to cognitive biases than laypersons (Dror, Citation2020). This is because experts rely on heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to simplify complex information and make quick and efficient decisions. The same mental processes that lead to more efficient decisions are also responsible for errors in judgment. Simply being aware that one is biased is considered an ineffective strategy to minimize the influence of cognitive biases, as it creates an illusion of control (Dror, Citation2020). Instead, in the area of forensic decision-making, researchers recommend formulating and testing different hypotheses to identify the most plausible scenario (e.g. Zapf & Dror, Citation2017). For example, hypothesis testing is at the core of Finnish recommendations regarding how child abuse investigations should be carried out (Korkman et al., Citation2017). This approach is worth exploring also in the asylum context. In the above example, this means that officials should thoroughly evaluate all the possible reasons why an applicant would delay the disclosure of their sexual orientation (e.g. lack of knowledge about the requirements for refugee status, lack of awareness about interview confidentiality, internalized homophobia, fabrication of the claim, etc.). Moreover, rather than overlooking information that disconfirms their initial hypothesis, officials should actively seek out and consider the whole body of existing evidence when determining which scenario is the most plausible.

Empirical research regarding cognitive bias in asylum decision-making, including in cases based on sexual orientation, remains scarce. Future research in applied cognitive psychology is needed to investigate evidence of cognitive bias in this context and propose appropriate bias mitigation strategies. Future studies could examine how rigorously asylum officials write down the reasons behind their positive and negative credibility findings regarding an asylum-seeker’s sexual orientation. Failing to do so might indicate that they use mental shortcuts to assess the credibility of a claim. On the other hand, officials who document the different steps of their reasoning would be able to re-check the soundness of their initial decisions. This would also increase procedural fairness, because asylum-seekers and their lawyers would be in a better position to address specific arguments when challenging a negative decision.

Activation of meta-stereotypes

The findings on asylum-seekers’ activation of meta-stereotypes about sexual minorities –that is, their attempts at matching the stereotypes they think officials have of them – also warrant further investigation. Survey-based studies could examine the extent to which asylum-seekers perceive conforming to stereotypes as important for their asylum outcome, and how often they activate these meta-stereotypes when describing their claim. The preliminary findings of the current study suggest that any recommendations to minimize the influence of stereotypes on asylum decision-making should target both asylum officials and asylum-seekers. To preserve the integrity of the asylum system, it is as important to reduce asylum-seekers’ perceived need to resort to these strategies as it is to improve asylum officials’ interviewing and decision-making skills. Clearly outlining the duties and rights of each participant within the asylum process would promote transparency and mutual trust. It is vital that asylum-seekers are able to tell their true stories without concerns about being refused if these do not match an official’s stereotypes.

Concluding remarks

The present literature review has highlighted the difficulty of evaluating asylum claims based on applicants’ sexual orientation. Across legal systems, asylum officials seem to face similar issues in determining how to evaluate the credibility of this construct. Psychological research, which has thus far investigated asylum procedures in general, should pay more attention to the specific challenges of investigating claims based on perceptually invisible identity markers, including peoples’ sexual orientation. This research could aid asylum policymakers to formulate more specific guidelines and develop training material on investigative interviewing, deception detection, and interpretation.

Overall, our findings suggest that when determining sexual minority applicants’ eligibility for refugee status, asylum officials often expect them to demonstrate a higher level of proof than the ‘reasonable degree of likelihood’ requirement set out in asylum law. Although asylum practices should be improved to avoid both false positive and false negative decisions, officials should not lose sight of the infinitely more detrimental consequences of refusing people who risk serious threats to their life, liberty or security based on their sexual orientation.

Data availability statement

The manuscripts that support the findings of this research are publicly available. Supplemental materials, which include an evidence table of all manuscripts and a table displaying the search strings used, are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- A, B, C v Staatssecretaris van Veiligheid En Justitie, C-148/13 to C-150/13 (Court of Justice of the European Union December 2, 2014).

- X, Y, and Z v. Minister voor Immigratie en Asiel, C-199/12 – C-201/12 (Court of Justice of the European Union November 7, 2013).

- Akin, D. (2015). Assessing sexual orientation-based persecution. Lambda Nordica, 20(1), 17–42. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2629963

- Akin, D. (2017). Queer asylum seekers: Translating sexuality in Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(3), 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1243050

- Anderton, C. L., Pender, D. A., & Asner-Self, K. K. (2011). A review of the religious identity/sexual orientation identity conflict literature: Revisiting festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 5(3–4), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2011.632745

- Andrade, V. L., Danisi, C., Dustin, M., Ferreira, N., & Held, N. (2020). Queering asylum in Europe: A survey report. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/kn6af.

- Asanovic, B. (2018). Still falling short: The standard of Home Office decision-making in asylum claims based on sexual orientation and gender identity. https://uklgig.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Still-Falling-Short.pdf.

- Baillot, H., Cowan, S., & Munro, V. E. (2013). Second-hand emotion? Exploring the contagion and impact of trauma and distress in the asylum Law context. Journal of Law and Society. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2013.00639.x

- Bennett, C., & Thomas, F. (2013). Seeking asylum in the UK: Lesbian perspectives. Forced Migration Review, 42, 25–28. https://ezp.sub.su.se/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=87468936&site=eds-live&scope=site

- Berg, L., & Millbank, J. (2009). Constructing the personal narratives of lesbian, gay and bisexual asylum claimants. Journal of Refugee Studies, 22(2), 195–223. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fep010

- Berlit, U., Doerig, H., & Storey, H. (2015). Credibility assessment in claims based on persecution for reasons of religious conversion and homosexuality: A practitioners approach. International Journal of Refugee Law, 27(4), 649–666. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eev053

- Bögner, D., Herlihy, J., & Brewin, C. R. (2007). Impact of sexual violence on disclosure during home office interviews. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(1), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030262

- Bohmer, C., & Shuman, A. (2007). Rejecting refugees: Political asylum in the 21st century (pp. 1–304). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203937228.

- Bohmer, C., & Shuman, A. (2018). Political asylum deceptions: The culture of suspicion (pp. 1–204). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67404-9

- Cass, V. C. (1979). Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4(3), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v04n03_01

- Choi, V. (2010). Living discreetly: A catch 22 in refugee status determinations on the basis of sexual orientation. Brooklyn Journal of International Law, 36(1), 5.

- Cohen, J. (2001). Questions of credibility: Omissions, discrepancies and errors of recall in the testimony of asylum seekers. International Journal of Refugee Law, 13(3), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/13.3.293

- Connely, E. (2014). Queer, beyond a reasonable doubt: Refugee experiences of ‘passing’ into ‘membership of a particular social group. UCL migration research unit working papers.

- Cory, C. (2019). The LGBTQ asylum seeker: Particular social groups and authentic queer identities. Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 20(3), 577. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/gender-journal/in-print/volume-20-issue-3-symposium-2019/the-lgbtq-asylum-seeker-particular-social-groups-and-authentic-queer-identities/

- Cox, W. T. L., Devine, P. G., Bischmann, A. A., & Hyde, J. S. (2016). Inferences about sexual orientation: The roles of stereotypes, faces, and the Gaydar myth. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1015714

- Dawson, J., & Gerber, P. (2017). Assessing the refugee claims of LGBTI people: Is the DSSH model useful for determining claims by women for asylum based on sexual orientation? International Journal of Refugee Law, 29(2), 292–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eex022

- De Bruyckere, V. (2018). Somewhere over the rainbow: On the use of psychological tests to determine asylum seekers’ sexual orientation and the impact on the right to private life (case C-473/16, 25 January 2018). Croatian Yearbook of European Law and Policy, 14(1), 256–272. https://doi.org/10.3935/cyelp.14.2018.311

- Dhoest, A. (2019). Learning to be gay: LGBTQ forced migrant identities and narratives in Belgium. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(7), 1075–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1420466

- Diamond, L. M. (2000). Sexual identity, attractions, and behavior among young sexual-minority women over a 2-year period. Developmental Psychology, 36(2), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.241

- Dowd, R., Hunter, J., Liddell, B., Mcadam, J., Nickerson, A., & Bryant, R. (2018). Filling gaps and verifying facts: Assumptions and credibility assessment in the Australian refugee review tribunal. International Journal of Refugee Law, 30(1), 71–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eey017

- Dror, I. E. (2020). Cognitive and human factors in expert decision making: Six fallacies and the eight sources of bias. Analytical Chemistry, 92(12), 7998–8004. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00704

- Dustin, M. (2018). Many rivers to cross: The recognition of LGBTQI asylum in the UK. International Journal of Refugee Law, 30(1), 104–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eey018

- Dustin, M., & Ferreira, N. (2021). Improving SOGI asylum adjudication: Putting persecution ahead of identity. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 40(3), 315–347. https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdab005

- Eliason, M. J., & Schope, R. (2007). Shifting sands or solid foundation? Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity formation. In I. H. Meyer, & M. E. Northridge (Eds.), The health of sexual minorities (pp. 3–26). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-31334-4_1

- European Asylum Support Office. (2014). EASO practical guide: Personal interview. https://easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/public/EASO-Practical-Guide-Personal-Interview-EN.pdf.

- Ferri, F. (2018). Assessing credibility of asylum seekers’ statements on sexual orientation: Lights and shadows of the F judgment. European Papers, 3(2), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.15166/2499-8249/232

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. https://books.google.fi/books?hl=sv&lr=&id=voeQ-8CASacC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=festinger+1957&ots=9z5bPvqbxv&sig=WwkTcki8lZxK6qi9p7ryMQMtp3Y&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=festinger1957&f=false.

- Garr-Schultz, A., & Gardner, W. (2019). “It’s just a phase”: Identity denial experiences, self-concept clarity, and emotional well-being in bisexual individuals. Self and Identity, 20(00), 528–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2019.1625435

- Gómez, Á. (2002). If my group stereotypes others, others stereotype my group … and we know. Concept, research lines and future perspectives of meta-stereotypes. Revista de Psicología Social, 17(3), 253–282. https://doi.org/10.1174/02134740260372982

- Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Hartwig, M. (2005). Granting asylum or not? Migration board personnel’s beliefs about deception. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183042000305672