ABSTRACT

Background

People with communication differences are known to have poorer hospital outcomes than their peers. However, the combined impact of aphasia and cultural/linguistic differences on care and outcomes after stroke remains unknown.

Objectives

To investigate the association between cultural/linguistic differences, defined as those requiring an interpreter, and the provision of acute evidence-based stroke care and in-hospital outcomes for people with aphasia.

Methods

Cross-sectional, observational data collected in the Stroke Foundation National Audit of Acute Services (2017, 2019, 2021) were used. Multivariable regression models compared evidence-based care and in-hospital outcomes (e.g., length of stay) by interpreter status. Models were adjusted for sex, hospital location, stroke type and severity, with clustering by hospital.

Results

Among 3122 people with aphasia (median age 78, 49% female) from 126 hospitals, 193 (6%) required an interpreter (median age 78, 55% female). Compared to people with aphasia not requiring an interpreter, those requiring an interpreter had similar care access but less often had their mood assessed (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.32, 0.76), were more likely to have physiotherapy assessments (96% vs 90% p = 0.011) and carer training (OR 4.83, 95% CI 1.70, 13.70), had a 2 day longer median length of stay (8 days vs 6 days, p = 0.003), and were less likely to be independent on discharge (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.33, 0.89).

Conclusions

Some differences exist in the management and outcomes for people with post-stroke aphasia who require an interpreter. Further research to explore their needs and the practical issues underpinning their clinical care pathways is required.

Introduction

Aphasia is a language disorder that occurs after insult or injury to the brain. The most common aetiology of aphasia is stroke, with approximately 30% of stroke survivors experiencing this type of impairment.Citation1,Citation2 Aphasia can affect spoken and written expressive language, auditory comprehension, reading, symbol recognition, and use of numbers.Citation3 The negative impact of aphasia on quality of life and functional outcomes is well documented.Citation4–7 People with aphasia have worse outcomes specifically related to their hospital admissions – with a longer length of stay, increased risk of complications and poorer satisfaction with their care.Citation8–10

These disparities are sequalae of communication breakdown within a healthcare setting.Citation10,Citation11 High quality and safe health care is reliant on clear and effective communication.Citation11 Any difference in communication style or ability has the potential to derail these processes.Citation11 This is reflected within the healthcare experiences of people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds who do not have a communication disability, but may not share the language and/or culture of the systems they need to access. In general, people with limited English proficiency have longer lengths of stay, increased frequency and severity of adverse events, and increased readmission rates compared to their English-speaking peers accessing hospital care.Citation12–15 This situation could be compounded by also having aphasia.

Communication differences and disability are not mutually exclusive experiences, and many people with aphasia will also experience the additional difficulty of navigating a healthcare system not inherently designed for their language or culture. This is especially true in Australia where more than 20% of the population speak a language other than English at home.Citation16 Typically, CALD is a term defined not only by whether a person requires an interpreter but also by their country of birth, languages spoken at home, and proficiency in English amongst other characteristics.Citation17,Citation18

Ethnicity and language proficiency are also known to impact stroke care and outcomes, especially for time-critical processes of care, such as administration of thrombolysis.Citation19 Stroke studies in Australia and New Zealand have provided evidence of differences in stroke medical management and discharge outcomes for CALD patients.Citation19,Citation20 With respect to the co-occurrence of CALD status and the presence of aphasia in people with stroke, there is limited research investigating differences in evidence-based care access or outcomes. From the literature that does exist, it has been suggested that CALD people with aphasia may be less likely to receive comprehensive language assessment in all their languages or have access to therapy in these languages.Citation19 The lack of access to culturally and linguistically appropriate assessment and therapy may have implications for hospital outcomes and discharge planning from inpatient services.

The overall objective of this study was to compare the care and in-hospital outcomes for people with aphasia from CALD backgrounds who required an interpreter after an acute stroke compared to those able to communicate in English.

Methods

Data collection

In this study, we used cross-sectional, observational data collected from Australian hospitals participating in the biennial Stroke Foundation National Stroke Audit of Acute Stroke Services in 2017, 2019 and 2021.Citation21–23 The audit has two components, an organisational survey and a clinical audit questionnaire.Citation24 The organisational survey is completed by a clinician with knowledge of stroke services at the participating hospital and includes questions about stroke service delivery (e.g. organisation of the workforce). The clinical audit involves the retrospective extraction of patient-level data from the medical records of at least 40 consecutive patients admitted with stroke by trained data abstractors who work in the stroke service of each hospital. Patient demographics, process of care variables reflective of nationally agreed clinical guideline recommendations, and in-hospital outcomes are collected.Citation25 The variables of interest for this study are provided in Supplemental Table S1.Citation26–28

Only data that pertained to patients who had aphasia were included in this study. Aphasia presence was indicated in the clinical audit by a “yes” response to the question “Did the patient have aphasia?”Citation26 The independent variable being investigated, CALD status, was identified solely by whether the patient required an interpreter, as country of birth and ethnicity were not collected. Aggregated data from all hospitals participating in any of the audit cycles were included.

Data analysis

Demographic and clinical information, process of care, and outcome indicators were compared for people with post-stroke aphasia who were reported to require an interpreter or not. Audit items related to demographic details or the presence of impairment (e.g. arm impairment), with “not documented” responses, were excluded from the analysis. Where questions related to processes of care such as allied health assessment, “not documented” or “unknown” responses were both assumed to be negative and included in the denominator for the analysis. This is consistent with previous audit studies.Citation29,Citation30 Records with missing responses were considered incomplete and excluded. For time-related processes with known dates but missing times, the time 23:59:59 was imputed.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise patient characteristics. Demographics, patient characteristics and care provided (evidenced by adherence to processes of care) were compared by interpreter status using relevant tests (chi square and Kruskal Wallis). Multivariable, multilevel logistic regression, with level defined as hospital, were undertaken to determine differences in adherence to processes of care by interpreter status. We considered that all eligible patients should receive each process of care, therefore no adjustment for confounding factors was undertaken in these multivariable analyses.

Outcomes included in-hospital complications, death, independence on discharge (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] 0–2,Citation31 discharge destination, and length of stay (LOS). Multivariable regression models were used to analyze the patient outcomes occurring as part of the acute hospital admission, including adjustment for clinical variables and known confounders such as age, sex, stroke type, hospital location, and stroke severity (arm impairment, incontinence, and mobility issues on admission).Citation32 Logistic regression was used for binary outcomes (e.g. presence of complications, independence on discharge), including the outcome as a dependent variable in separate models, with level being hospital. Median regression models were used for LOS, with clustering to account for hospital differences. Results of multivariable models were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) or coefficients, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical tests were two-sided, with level of significance at p < 0.05. Data were analyzed using Stata SE 17.0 (www.stata.com). This study and manuscript conforms to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Guidelines for cross-sectional studies.Citation33

Results

Demographic and stroke characteristics

Across the three audit cycles, there were 12,258 acute stroke admissions, 3122 (25%) of the patients audited were reported to have aphasia whereby 193 (6%) were recorded as having required an interpreter while in hospital for acute stroke. Almost all (91%) of the patients who required an interpreter were treated in a hospital in a major cityCitation25 with spread across hospitals of different sizes (20% <200 admissions, 44% 200–499 admissions, 36% 500+ admissions). There were no significant differences in age, pre-stroke history, sex, or stroke severity indicators evident in people with aphasia based on the need for an interpreter (). However, people with aphasia who required an interpreter were more likely to be living with others prior to stroke (78 vs 61%, p < 0.001) or to have had a hemorrhagic stroke (18% vs 13%, p = 0.04).

Table 1. Demographics and characteristics of patients with aphasia by interpreter status after acute stroke.

Processes of Care

In univariable analysis, patients with post-stroke aphasia who required an interpreter were more likely to be directly admitted to a stroke unit or receive care in a stroke unit at any time during their admission than those who did not require an interpreter (). However, this was mitigated when individual hospital variation was adjusted for. Similar proportions of patients with post-stroke aphasia requiring an interpreter or not, had an assessment by a speech pathologist and occupational therapist (). Although people with aphasia requiring an interpreter were more likely to have a social work assessment (71% vs 63%), once adjusted for individual hospital variation, this was no longer a significant difference. A large proportion of patients with post-stroke aphasia received physiotherapy assessment and this was greater in the interpreter group (Interpreter 96% vs No Interpreter 90%). In relation to mood assessments, patients with aphasia who required an interpreter were 50% less likely to have their mood assessed (18% vs 23%,).

Table 2. Ward of admission and adherence to processes of care by interpreter status for people with aphasia after acute stroke.

Outcomes

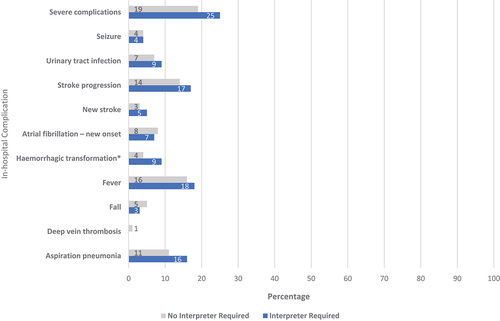

shows unadjusted percentages for in-hospital complications by interpreter status. People with aphasia who required an interpreter were more likely to suffer a hemorrhagic transformation (9.33% vs 4.4%, p = 0.002) than those who did not require an interpreter. However, care must be taken with the interpretation due to small numbers.

Figure 1. Hospital complications in people with aphasia by interpreter status.

depicts in-hospital outcomes. No differences were evident for death, discharge destination or presence of one or more in-hospital complications. However, patients with post-stroke aphasia who required an interpreter were 44% less likely to be independent on discharge (mRS 0–2) and had a median 2 day longer length of stay than those who did not require an interpreter (interpreter 8 days, no interpreter 6 days).

Table 3. Hospital outcomes by interpreter status.

Discussion

This is the first time that in-hospital stroke care and outcomes of people with aphasia requiring an interpreter have been quantitatively compared to people with aphasia who can communicate in English using nationally representative data. We found that the group who needed an interpreter received different care for some aspects: they were almost five times more likely to have carer training provided, over two times more likely to be assessed by a physiotherapist but half as likely to have their mood assessed. Our findings also demonstrate that people with aphasia who require an interpreter have significantly different hospital outcomes to their peers who do not require an interpreter: they stay in hospital 2 days longer, and they are almost half as likely to be physically independent of discharge.

Our results are consistent with previous broader stroke research that indicated CALD people with acute stroke experience differences in care and outcomes. Rezania and colleaguesCitation34 observed that patients from CALD backgrounds with acute stroke admitted to their local Australian service in 2014–2017 had an average 14-min delay in administration of thrombolysis from onset of stroke symptoms. In their study, the patients with a language barrier (n = 76) had longer lengths of stay (median 6 vs 4 days) and were more likely to be discharged to residential aged care facilities compared to those without a language barrier (n = 298).Citation34 Similarly, a New Zealand study found that patients from non-European backgrounds were less likely to have their swallow screened within 24 h of admission or have magnetic resonance imaging.Citation21 We observed reduced independence on discharge as measured on the mRS which aligns with that study’s findings that ethnicity does have a correlation to poorer mRS scores at 3, 6 and 12 months post stroke.Citation20 We acknowledge that in-hospital outcomes may conflict with outcomes at these later times post stroke. However, in data collected through the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry (AuSCR), stroke survivors who need an interpreter have been observed to report poorer quality of life 90–180 days post stroke when compared to peers who do not require an interpreter.Citation35,Citation36 We identified that people with aphasia who required an interpreter had a higher proportion of hemorrhagic strokes. However, after this covariate was adjusted for in multilevel regression analysis, the interpreter group continued to have significantly lower rates of physical independence on discharge. This confirms the influence of other factors beyond stroke type on outcomes. Our research supports the conclusions from previous review work that posited that CALD people with aphasia may have different outcomes and clinical pathways to their non-CALD peers.Citation19

Our findings suggest that, although this group of CALD people with aphasia have high rates of acute allied health assessment, especially for physiotherapy, this does not translate to reduced length of stay or increased physical independence on discharge. In addition, there were no differences in access to speech pathology or stroke unit care, which is associated with improved care delivery and outcomes.Citation37 This may be because our data only reflects whether an assessment was completed by a clinician, not the frequency, intensity, or quality of the assessment and/or therapy provided. It may be that initial assessments or screens were completed by an allied health discipline without an interpreter present, but more comprehensive assessment and effective intervention was delayed whilst the team coordinated interpreting services or family to support the patient’s participation. Despite less independence, longer length of stay and higher rates of carer training, there were no differences in discharge destinations, perhaps attributable to the small cohort of people who required an interpreter in this data set.

The higher rates of carer training in the interpreter group may be explained by several factors that are not able to be directly explored in this data set. Firstly, the longer admission may provide the additional time required to engage families in carer training. The interpreter group were more likely to live with others prior to their stroke which could correlate to increased availability of potential carers, especially if a carer is attending to help with informal interpreting and therefore speaks English. Similarly, certain cultural groups may be more likely to have large families visiting their loved ones whilst in hospital; as such, more potential carers could physically be present to engage in ad hoc carer training.Citation38,Citation39

It is concerning that there were reduced rates of mood assessment for those patients who required an interpreter. People with aphasia post-stroke are already known to be at higher risk of depression and mood disorders than their non-aphasic stroke peers.Citation40 Consequently, there may be broader implications for the mental health of CALD people with aphasia post stroke beyond the acute setting where there is evidence of higher rates of anxiety and depression.Citation36 Cultural attitudes to mental health may also be a factor in engaging in mood assessment.Citation41

Strengths and limitations

The strengths and limitations of the Audit data have been described in previous publications.Citation24,Citation29,Citation30 We can be confident in the quality and the representative nature of our data for several reasons. It is a large and comprehensive national dataset, the reliability of which is further enhanced by: the use of a data dictionary; the training of data abstractors; a web-tool with in-built logic checks to minimise erroneous data entry, and inter-reliability monitoring.Citation24,Citation25 There was 100% completeness of the data variable “requires an interpreter” and near perfect interrater-reliability for the cycles we analyzed.Citation42 Despite these strengths, the differences in the size of each of our participant groups may limit the power of our findings.

A key limitation to these data is the use of “requires an interpreter” as the sole CALD identifier. CALD is a broad and contentious umbrella termCitation43,Citation44 used to refer to a heterogenous group of people ranging from first generation immigrants (which may include refugees and asylum seekers) who do not speak English at all to third generation citizens who speak languages other than English sparingly. In other international contexts, cultural, ethnic, and language differences may be described and classified in alternative ways to the Australian designation of “CALD.”Citation45 As this study used retrospective data collected within the Stroke Foundation Audit Program, use of an interpreter was the only available variable through which to explore possible influences of culture and language on the care pathways of people with aphasia. It was not possible to collect any further variables that may have been relevant to exploring the influence of CALD status.

This limited identification of CALD status may explain the small number of participants, with only 6.18% of the cohort identified as requiring an interpreter. This limits the generalisability of our findings. With broader options for identifying CALD status, such as country of birth or ancestry, the groups may be distributed differently with closer to 20% fitting a CALD description which would reflect the latest census data where one in five Australians reported speaking a language other than English at home.Citation16 For example, studies using data from the AuSCR, that collects country of birth, had 27% of participants born overseas (although this would also include people from English speaking countries).Citation46 The group of CALD people we have investigated potentially represents the most marginalised of the broader CALD group given their baseline communication differences. It is likely that bilingual or multilingual people with aphasia may have been included in the “do not need an interpreter” group, when they would typically be considered CALD. As ethnicity is not collected in the audit, we were unable to determine the proportion of patients who could not speak English by ethnic status which may be a better determinant of language barriers than use of interpreter. Regardless, as no current studies exist that investigate differences in acute care and outcomes for CALD people with aphasia, this work remains valuable.

A second limitation of this work is collecting retrospective, cross-sectional data across a number of years in discrete auditing programs. This data only reflects snapshots in time of the care provided. The characteristics of the participating hospital and the audited patients may differ between years, especially for the 2021 audit which was conducted on stroke admissions that took place amidst then evolving systems dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic which may have impacted care and access to interpreters. However, given the small numbers in the interpreter group, analysis of differences between years was not anticipated to be useful. There may be other comorbidities or covariables that were not collected that could have affected the outcomes we studied. These data only reflect whether a patient required an interpreter, not whether they received any interpreter services. Therefore, analysis on the impact of accessing an interpreter could not be conducted.

We also identified differences in several processes of care and outcomes that were trending toward significance (i.e. p value between 0.05 and 0.1) that would benefit further targeted investigation with larger sample sizes. These included aspiration pneumonia, severe complications, swallow screening on admission, dietitian and psychologist assessment, and discharge to residential care.

Finally, the accuracy of the information gathered from patient files is dependent on the accuracy and quality of medico-legal documentation. We acknowledge the variability of this which may have resulted in under-documentation of certain audit items. As we only analyzed data for patients who had been reported as having aphasia, we cannot account for patients who may have had aphasia but were not diagnosed with the impairment during this admission. For example, people with mild aphasia may be less likely to be identified in the acute setting, especially if there is limited access to speech pathology. Another group that may be vulnerable to under-identification of aphasia is bilingual people with mild aphasia. For example, if their impairments in English are very mild, allowing them to easily participate in care without an interpreter, aphasia in their other language/s may not be detected.

Future research directions

In future research, ethnic status and primary language spoken at home should be collected as well as confirmation that interpreter services were used. These items align with the call for more robust health data collection for people from CALD backgrounds.Citation47 Next steps for exploring in-hospital evidence-based care and outcomes for CALD people with aphasia should include studies that focus on the inpatient rehabilitation phase of care. Work is currently underway by this team of authors to make these rehabilitation comparisons for people with aphasia who do and do not require an interpreter using data from the Stroke Foundation National Stroke Audit of Rehabilitation Services.

The results of this work suggest there are likely complex interactions between the practice of stroke clinicians and the systems and service models they work in which impact clinical pathways for CALD people with aphasia. These interactions would benefit from investigation that considers perspectives of all those involved in stroke care: medical, nursing, allied health, interpreter services and the patients and their families.

Conclusions

Differences exist in acute stroke management and outcomes for people with aphasia who require an interpreter compared to those who do not. Further research is required to explore the needs of people with aphasia from CALD backgrounds, the practice needs of their clinicians, and the systems underpinning their clinical pathways.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for data used in this project was granted through the Human Research Ethics Committee from Monash University (Project ID 35,037).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the hospitals and clinicians participating in the National Stroke Audit Program.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2023.2295128

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pedersen PM, Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Aphasia in acute stroke: incidence, determinants, and recovery. Ann Neurol. 1995;38(4):659–666. doi:10.1002/ana.410380416.

- Lalor E, Cranfield E. Aphasia: a description of the incidence and management in the acute hospital setting. Asia Pac J Speech Lang Hear. 2004;9(2):129–136. doi:10.1179/136132804805575949.

- Papathanasiou I, Coppens P. Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Second edition ed: Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2016.

- Manders E, Dammekens E, Leemans I, Michiels K. Evaluation of quality of life in people with aphasia using a Dutch version of the SAQOL-39. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(3):173–182. doi:10.3109/09638280903071867.

- Hilari K, Byng S. Health-related quality of life in people with severe aphasia. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2009;44(2):193–205. doi:10.1080/13682820802008820.

- Hartman-Maeir A, Soroker N, Ring H, Avni N, Katz N. Activities, participation and satisfaction one-year post stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(7):559–566. doi:10.1080/09638280600924996.

- Worrall L, Holland A. Editorial: quality of life in aphasia. Aphasiology. 2003;17(4):329–332. doi:10.1080/02687030244000699.

- Sullivan R, Harding K. Do patients with severe poststroke communication difficulties have a higher incidence of falls during inpatient rehabilitation? A retrospective cohort study. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2019;26(4):288–293. doi:10.1080/10749357.2019.1591689.

- Stransky ML, Jensen KM, Morris MA. Adults with communication disabilities experience poorer health and healthcare outcomes compared to persons without communication disabilities. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(12):2147–2155. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4625-1.

- Bartlett G, Blais R, Tamblyn R, Clermont RJ, MacGibbon B. Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. CMAJ. 2008;178(12):1555–1562. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070690.

- O’Daniel M, Rosenstein AH. Chapter 33 professional communication and team collaboration. In: RG H, ed. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2637/

- Seman M, Karanatsios B, Simons K, et al. The impact of cultural and linguistic diversity on hospital readmission in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2019;6(2):121–129. doi:10.1093/ehjqcco/qcz034.

- John-Baptiste A, Naglie G, Tomlinson G, et al. The effect of English language proficiency on length of stay and in-hospital mortality. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):221–228. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21205.x.

- Divi C, Koss RG, Schmaltz SP, Loeb JM. Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(2):60–67. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzl069.

- Basic D, Shanley C, Gonzales R. The impact of being a migrant from a non-English-speaking country on healthcare outcomes in frail older inpatients: an Australian study. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2017;32(4):447–460. doi:10.1007/s10823-017-9333-5.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Cultural Diversity of Australia. Canberra; 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/cultural-diversity-australia

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Standards for Statistics on Cultural and Language Diversity. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2022.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2018. In: Vol Australia’s Health Series No. 16. AUS 221. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/f3ba8e92-afb3-46d6-b64c-ebfc9c1f945d/aihw-aus-221-chapter-5-3.pdf.aspx

- Mellahn K, Larkman C, Lakhani A, Siyambalapitiya S, Rose ML. The nature of inpatient rehabilitation for people with aphasia from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: a scoping review. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2021;30(2):1–11. doi:10.1080/10749357.2021.2008599.

- Thompson SG, Barber PA, Gommans JH, et al. The impact of ethnicity on stroke care access and patient outcomes: a New Zealand nationwide observational study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;20:100358–100358. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100358.

- Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit Acute Services Report 2017. Melbourne Australia. https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-health-professionals/audits/. Accessed November 2021

- Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit Acute Services Report 2019. Melbourne Australia https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-health-professionals/audits_. Accessed November 2021.

- Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit Acute Services Report 2021. Melbourne Australia. https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-health-professionals/audits//. Accessed November 2021

- Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit Program Methodology. Melbourne Australia. https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-health-professionals/audits/_. Accessed November 2021

- Ryan O, Ghuliani J, Grabsch B, et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of the Australian stroke data tool (AuSdat): comprehensive data capturing for multiple uses. Health Inform Manag. 2022;183335832211171–18333583221117184. doi:10.1177/18333583221117184.

- Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit Acute Services Report 2021 Supplimentary Report. Melbourne Australia https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-health-professionals/audits_/. Accessed November 2021

- Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit Acute Services Report 2019 Supplimentary Report. Melbourne Australia https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-health-professionals/audits///. Accessed November 2021

- Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit Acute Services Report 2017 Supplimentary Report. Melbourne Australia https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-health-professionals/audits. Accessed November 2021

- Purvis T, Hill K, Kilkenny M, Andrew N, Cadilhac D. Improved in-hospital outcomes and care for patients in stroke research: an observational study. Neurology. 2016;87(2):206–213. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002834.

- Cahill LS, Lannin NA, Purvis T, et al. What is “usual care” in the rehabilitation of upper limb sensory loss after stroke? Results from a national audit and knowledge translation study. Disabil Rehabilitat. 2021;0(0):1-96462–6470. doi:10.1080/09638288.2021.1964620.

- Banks JL, Marotta CA. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials a literature review and synthesis. Stroke. 2007;38(3):1091–1096. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000258355.23810.c6.

- Counsell C, Dennis M, McDowall M, Warlow C. Predicting outcome after acute and subacute stroke: development and validation of new prognostic models. Stroke. 2002;33(4):1041–1047. doi:10.1161/hs0402.105909.

- Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S31–s34. doi:10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18.

- Rezania F, Neil CJA, Wijeratne T. Disparities in care and outcome of stroke patients from culturally and linguistically diverse communities in metropolitan Australia. J Clin Med. 2021;10(24):5870. doi:10.3390/jcm10245870.

- Cadilhac DA, Andrew NE, Lannin NA, et al. Quality of acute care and long-term quality of life and survival: the Australian stroke clinical registry. Stroke. 2017;48(4):1026–1032. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015714.

- Kilkenny MF, Lannin NA, Anderson CS, et al. Quality of life is poorer for patients with stroke who require an interpreter: an observational Australian registry study. Stroke. 2018;49(3):761–764. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019771.

- Cadilhac DA, Kilkenny MF, Andrew NE, Ritchie E, Hill K, Lalor E. Hospitals admitting at least 100 patients with stroke a year should have a stroke unit: a case study from Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):212. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2150-2.

- Nash D, O’Rourke T, Memmott P, Haynes M. Indigenous preferences for inpatient rooms in Australian hospitals: a mixed-methods study in cross-cultural design. HERD: Health Environ Res Design J. 2020;14(1):174–189. doi:10.1177/1937586720925552.

- Andruske CL, O’Connor D. Family care across diverse cultures: re-envisioning using a transnational lens. J Aging Stud. 2020;55:100892. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100892.

- Lincoln NB, Kneebone II, Macniven JAB, Morris RC. Psychological Management of Stroke. 2nd ed Hoboken: Hoboken : John Wiley & Sons;. 2011;281–298.

- Papadopoulos C, Leavey G, Vincent C. Factors influencing stigma: a comparison of Greek-Cypriot and English attitudes towards mental illness in north London. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. 2002;37(9):430–434. doi:10.1007/s00127-002-0560-9.

- Kilkenny M. 2023.

- Mousaferiadis P Why ‘culturally and linguistically diverse’ has had its day. https://www.diversityatlas.com.au/heres-why-cald-has-had-its-day/. Published 2020. Accessed April 17 2021.

- Marcus K, Balasubramanian M, Short S, Sohn W. Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD): terminology and standards in reducing healthcare inequalities. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2022;46(1):7–9. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.13190.

- Pham TTL, Berecki-Gisolf J, Clapperton A, O’Brien KS, Liu S, Gibson K. Definitions of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD): a literature review of epidemiological research in Australia. Int J Environ Health Res. 2021;18(2):737. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020737.

- Andrew NE, Kilkenny MF, Lannin NA, Cadilhac DA. Is health-related quality of life between 90 and 180 days following stroke associated with long-term unmet needs? Qual Life Res. 2016;25(8):2053–2062. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1234-5.

- FECCA. Towards consistent National data collection and reporting on cultural, ethnic and linguistic diversity. Deakin Australian capital territory: federation of ethnic communities. Councils of Australia. 2020;5–21.