Abstract

Dementia prevention is an area of health where public knowledge remains limited. A growing number of education initiatives are attempting to rectify this, but they tend to reach audiences of limited size and diversity, limiting intervention-associated health equity. However, initiative participants tend to discuss these initiatives and the information they contain with members of their social network, increasing the number and diversity of people receiving dementia risk reduction information. In this qualitative study, we sought to understand the drivers of this information sharing. We interviewed 39 people from Tasmania, Australia who completed the Preventing Dementia Massive Open Online Course in May 2020. We identified themes from responses to semi-structured interview questions using reflexive thematic analysis. We identified three key drivers of information sharing: participants’ personal course experiences; participants finding information sharing opportunities with people they expected to be receptive; and conversation partners’ responses to conversation topics. These drivers aligned with existing communication theories, with dementia-related stigma effecting both actual and perceived conversation partner receptivity. Understanding the drivers of information sharing may allow information about dementia risk reduction, and other preventative health behaviors, to be presented in ways that facilitate information diffusion, increasing equity in preventative health education.

Introduction

Theoretical frameworks of behavior change (Armitage & Conner, Citation2000; Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, Citation2002; Rogers, Citation2003), and empirical investigations into facilitators of health behaviors (Brunet, Abi-Nader, Barrett-Bernstein, & Karvinen, Citation2021; Claflin et al., Citation2021; Guan, Citation2021; Spronk, Kullen, Burdon, & O’connor, Citation2014) suggest that knowledge is an important driver of healthy behavior. However, not all aspects of health are adequately understood by the public, making behavior change challenging. Dementia prevention is one health domain where public understanding is limited (Horst et al., Citation2021; Van Asbroeck et al., Citation2021; Vrijsen, Matulessij, Joxhorst, De Rooij, & Smidt, Citation2021), despite evidence that risk-reducing behavior change could reduce dementia incidence worldwide (World Health Organization, Citation2021; World Health Organization, Citation2017). Wide-reaching education campaigns are therefore needed to increase dementia risk knowledge and promote risk-reducing behavior.

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) offer a method for providing large public audiences with detailed preventative health information, thereby widely promoting preventative health behavior (Claflin et al., Citation2021). The Preventing Dementia MOOC (PDMOOC) was therefore developed to provide information about dementia risk reduction (Farrow, Fair, Klekociuk, & Vickers, Citation2022). This MOOC, like many others, reaches a large global audience (over 100,000 enrollments across 5 years) with limited demographic diversity (Farrow, Fair, Klekociuk, & Vickers, Citation2022; Hansen & Reich, Citation2015; Reich & Ruipérez-Valiente, Citation2019). The PDMOOC’s participants share many characteristics with traditional information seekers, and this audience is similar to that reached by other dementia risk reduction initiatives: primarily highly educated women from high income countries (Fair, Klekociuk, Eccleston, Doherty, & Farrow, Citation2022; Farrow, Fair, Klekociuk, & Vickers, Citation2022; Zimmerman & Shaw, Citation2020).

Information sharing through interpersonal communication may broaden the reach of health initiatives and the information they contain (Fair, Doherty, Klekociuk, Eccleston, & Farrow, Citation2021; Nolan, Schall, Erb, & Nolan, Citation2005; Rogers, Citation2003). This concept has been utilized in public health campaigns through educating a subset of community members and promoting further dissemination (Amirkhanian et al., Citation2005; Starmann et al., Citation2018). Health information sharing is associated with health information seeking and scanning, indicating that people who seek health information may further disseminate information (Liu, Yang, & Sun, Citation2019). Accordingly, PDMOOC participants frequently reported discussing this initiative and its content in interpersonal conversations, transmitting information to a larger and more diverse audience than the audience reached directly (Fair, Klekociuk, Eccleston, Doherty, & Farrow, Citation2022). Strength-of-weak ties theory suggests that information will reach audiences of greatest diversity when it is shared with people who are less well-known to initiative participants (Granovetter, Citation1973).

Health information sharing often occurs within everyday social interactions (Huisman, Joye, & Biltereyst, Citation2020), and is influenced by the way information is presented (Mao et al., Citation2021). Social exchange and social capital theories suggest that information sharing is driven by a desire to obtain relational rewards, and is likely impacted by social norms around particular conversation topics (Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, Citation2002; Pilerot, Citation2012). Health information sharing may be most effective when the information sharer is viewed as a health “opinion leader” within their social network: a person perceived by others as having the knowledge and authority required to provide health advice (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation2017; Valente & Pumpuang, Citation2007). Understanding the facilitators and inhibitors of health information sharing may allow educational interventions to enhance sharing to realize benefits on information reach.

We therefore sought to investigate the question: “What drives conversations relating to an online course about dementia risk reduction?.” We investigated this question among completers of the PDMOOC, as we have previously found that PDMOOC participants regularly share learnt information (Fair, Klekociuk, Eccleston, Doherty, & Farrow, Citation2022).

Methods

Participants

All Tasmanians who enrolled in the PDMOOC for the first time in May 2020 (n = 712) were invited to participate in this study, with 125 participants initially enrolling. All participants who completed the MOOC and pre- and post- MOOC surveys were invited to participate in an interview (n = 59) and all participants who accepted this invitation were interviewed, leading to a convenience sample of 39 participants. Participant demographics were collected and collated as previously described (Farrow, Fair, Klekociuk, & Vickers, Citation2022), and are detailed in . Research consent was provided through an online information sheet and consent form and confirmed verbally prior to interview recording. This study was approved by the University of Tasmania Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference number H0018544).

Table 1. Participant demographics (n = 39)

Context

Participants were interviewed between 22/06/2020 and 02/09/2020, a time when Tasmania was gradually easing restrictions implemented to limit the spread of COVID-19 (Bartlett et al., Citation2021). In-person gatherings were restricted in the time leading up to interviews, but gatherings of increasing size were permitted across the interview period itself. Interstate and international travel remained restricted throughout.

Theoretical Perspective

This research was undertaken from a social constructivism perspective; researchers sought to understand participants’ socially constructed knowledge of discussing dementia risk reduction, while acknowledging their own socially constructed, and continually evolving, perspective on discussing dementia risk reduction.

Procedure

One author (HF: female, Caucasian) interviewed all participants. At the time of this study, this author was a 26-year-old PhD candidate new to qualitative research, supervised by experienced qualitative researchers (KD, CE). Interviews were conducted online using Zoom (Archibald, Ambagtsheer, Casey, & Lawless, Citation2019) and lasted up to 1.5 hours, unless participants specifically requested an in-person interview (n = 1), a phone interview (n = 1), or a longer interview duration (n = 2). Field notes and reflexive journaling were used to reflect on the impact of researcher experiences and assumptions on participants’ responses.

During the interview, participants were assisted to produce a digital map of their social network, including everyone they felt “very close or somewhat close to,” and providing basic demographic information about each network member (Complex Data Collective, Citation2016; Froehlich & Brouwer, Citation2021; Perry, Pescosolido, & Borgatti, Citation2018). Participants were asked to identify network members with whom they regularly exchanged health advice, and network members with whom they had discussed dementia risk reduction and/or the PDMOOC. Semi-structured explanatory questions were asked throughout this network mapping (Froehlich & Brouwer, Citation2021) (supplementary Table 1). This interview process was informed by the literature (Perry, Pescosolido, & Borgatti, Citation2018) and expert advice, and was trialed and iteratively refined with three volunteers.

Interviews were audio and/or video recorded and transcribed verbatim by two authors (HF, ME). Transcript quality was verified by a second author for a random sample of at least 10% of each transcriber’s interviews. Field notes and reflexive journal entries were included with transcripts prior to analysis. Transcripts were not verified by participants, as participants’ understanding of the research topic were expected to evolve over time, and responses provided at interview were considered most pertinent.

Data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Braun, Clarke, Hayfield, & Terry, Citation2019). Interviewing, transcribing, data familiarization and debriefing with other authors (ME, KD, MF) indicated to HF that the data included rich, contextual, participant narratives. HF inductively coded all interviews with the assistance of NVivo software (release 1.2), mapping the key concepts iteratively from each interview into a cognitive map of drivers of information sharing. No new concepts were identified in the final interviews coded, indicating that concept saturation was reached. HF, in consultation with senior authors (KD, CE, SK, MF) then identified three overarching themes and several sub-themes.

Results

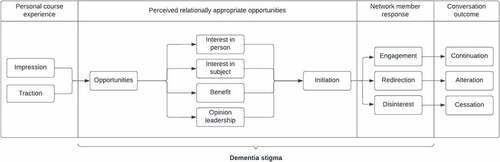

Information sharing about the PDMOOC and/or dementia risk reduction was driven by participants’ course experiences, opportunities to initiate discussions, perceptions of network member receptivity to information, and network members’ responses to information (). Perceptions of network member receptivity were informed by perceptions of network member interests, opinion leadership, and the potential for network members to benefit from shared information. Dementia stigma impacted conversation opportunities, perceptions of receptivity, and network member responses ().

Figure 1. The drivers of dementia risk information sharing were identified from participant interviews and used to produce a model of this information sharing process. This process first involved participants’ personal course experience (panel 1) which, if positive, was associated with a desire to share information. participants then initiated conversations when they identified an appropriate opportunity with network members they perceived as being receptive to this conversation topic (panel 2). network members’ responses to this conversation topic then determined the dementia risk-related conversation outcome (panels 3 and 4). Dementia stigma influenced participants’ perceptions of relationally appropriate opportunities (panel 2) and network members’ responses to dementia risk conversations (panel 3).

Personal course experience

Impression

Most participants found the course “very valuable” (P037) and looked for opportunities to discuss it with others.

“the MOOC courses have been coming up [in conversations] because I’ve been doing it [sic], and I’ve been quite excited about what I’ve been finding out”- P024

One participant responded “no” (P02) when asked if they’d shared information from or about the course, explaining:

“one I don’t think I’ve learnt very much, and two I don’t think they’d be interested … I was a bit disbelieving about some of it … It just made me a bit sceptical.” – P02

This suggests that finding personal value in the course was an important antecedent to information sharing.

Traction

Conversations about dementia risk were shaped by the course elements participants found most valuable. Participants either valued the course as an education opportunity: “it was a really good way for me to study” (P038) or as a source of dementia risk information: “It was very interesting. There were parts of it I knew and parts which were enlightening” (P010). Participants who viewed the course as an educational accomplishment tended to discuss it as something they were doing, that their network members could do too:

“[my Mum, my sister and I] all got our certificates on the same day and we were bragging about our certificates to my other two siblings, and then I got my husband into it” – P05

Specific information about dementia risk reduction was valued when it was understood, when it aligned with previous beliefs, invoked an emotional reaction, and/or when it lead to behavior change. One participant explained that information about cognitive activity had “rattled my cage a bit, in terms of doing a bit more” (P032). This emotional response – a “rattled cage” - sparked this participant’s interest in studying “psych … or something … or family history” at university. This participant then recalled discussing cognitive activity with their network members:

“I’d say “learn new things” … I’ve recommended [further study to] a couple of friends, and because they’re musicians - one enrolled in something at the Con [Conservatorium of Music] straight away” – P032

Alternatively, among participants who found the course broadly valuable, having beliefs challenged by specific course content drove discussions with network members. For example, multiple participants were skeptical that yoga is ineffective for risk-reduction as they practised yoga and believed it to be a broadly beneficial form of physical activity.

“the MOOC was fresh in my mind, and because I disagreed with some of the comments that were made around yoga, somehow it came up … that’s how that conversation started” – P031

Relationally appropriate opportunities

Opportunities

Opportunities to discuss the course and/or dementia risk reduction arose whenever participants were interacting with others.

“I told [name removed] when we were having a cup of tea, I told [name removed] when we were walking” – P03

“whenever I can, [I] make a comment about what I’ve learnt” – P08

For some participants, opportunities to share information also arose when interacting with service providers such as hairdressers and nail technicians.

“you just sit for an hour while they do your nails and you just talk about everything” – P09

COVID-19 containment measures provided more conversation opportunities in some relationships and less in others.

“[because of] COVID … I’ve re-kindled and strengthened friendships because we’re here [in Tasmania]” – P032, (who usually spends significant time interstate)

“when the lockdown happened … I made a list of lots of people [to call] … I contacted some people … that I hadn’t spoken to for so long” – P037

“we usually catch up for lunches but haven’t done that since the lockdown [ended] … so I haven’t actually been in touch with her” – P07

“when you’re face to face … it’s easier to converse about something like [dementia risk reduction]” – P08

“[in] our weekly zoom chat … I was telling them [my friends] lots of things [about dementia risk]” – P017

Perceived Receptivity

Participants initiated conversations about the MOOC and/or dementia risk reduction if they believed a conversation partner would be receptive to the information because of perceived interest in the participant or perceived interest in a dementia-risk related subject.

“Partly [these conversations] come up with the people I see more regularly, and partly it depends on the nature of the particular interactions” – P06

Perceived Interest in the Person

Many participants discussed the course and dementia risk reduction as part of regular interactions with friends and family. These conversation partners were perceived as receptive to this information because they were interested in the hearing about events in the participants’ life:

“[When people ask] “how are we spending our time” or “what are we doing,” I’ve just said [that the course is] something that I’m doing at the moment” – P037

“I’ve been seeing these people on a regular basis while I was doing the course, and I always used to go and say “Ahh guess what I learnt today”” – P024

Perceived Interest in the Subject

Network members were also perceived as receptive to hearing about dementia risk reduction if they were interested in a particular risk domain or engaged in a particular risk-reducing behavior:

“a friend of mine was doing a puzzle the other day … we talked about that and how it’s good for the brain and helps to [reduce dementia risk]” – P025

Similarly, information about the course as an educational opportunity was deemed to be interesting and relevant to people who worked in health care or who were involved with the university.

“And I’ve spoken to [name removed] [about the course], ‘cause she’s a doctor” – P010

“so [name removed] is the one who’s the scientist and whose partner works at [health research institute], so we’ve talked quite a lot about it [the course]” – P013

Participants also shared specific information about the course with people who were not part of their close contact network because they were perceived as being interested in hearing about the course.

“the young guy [laptop salesman] said “oh so what are you studying at University?” I said “oh, diploma of dementia care” and he said, “Oh my wife wanted to do that, but she thought it was gonna be too much, but she’s interested in that” and I said “oh!” … I actually gave him the details [of the PDMOOC]” – P011

Participants, irrespective of age, often felt that people their age or older would be interested in discussing dementia risk reduction.

“Because we’re all the same age … [health and dementia are] a topic that you can’t really avoid, because you’re all concerned about being old or getting old” – P01

“Look at my age - a lot of my friends [that I’ve talked to about dementia risk] are around the same age, and often they’ve also got ageing parents” – P013

Data from some participants challenged this perception by reporting positive experiences of sharing information with younger people:

“[I’ve told young adult daughters and] they tell all their friends … I reckon everybody in my daughter’s circle of friends in Sydney will know about the dementia course … all of them would certainly know the alcohol [risk factor]” – P014

Most female participants perceived women to be more interested in hearing about dementia risk reduction than men, leading them to initiate conversations primarily with female network members.

“trying to get men to talk about these things [health and dementia risk] is often a lot harder than getting women to talk about it” – P01

Male participants, however, reported sharing information both about dementia and health more generally with male peers.

“my work colleagues [predominantly men] and I, we’re quite open with what we discuss with our men’s health and things like that” – P019

Perceived benefit

The potential for dementia risk information to benefit network members was identified as another component of perceived receptivity. Network members were perceived as being receptive to information about dementia risk reduction if they were engaged in activities where they could utilize information to improve their risk related behaviors.

“if you’re having a drink of alcohol, you know, sometimes you will talk about “well, you know, we’re trying to decrease use because they don’t wanna have dementia”” – P05

“I said [to the dance class I teach] … “I know you people often say make it easy, but in fact we should be doing challenging dances, because we need to get our brains around it.” And I told them about the preventing dementia course” – P01

Alternatively, network members were considered less receptive if they were perceived as unlikely to benefit from that information, either because of preexisting risk-reducing behavior:

“The keeping socially active - I guess I haven’t mentioned that because they do [keep socially active]” – P032

or because they were perceived as being unlikely to change their behavior:

“she’s got all the risk factors practically. [Talking about dementia risk] is really not going to be much help to her at this stage, because there’s no way she is going to suddenly turn her world around” – P012

Perceived opinion leadership

Participants were also concerned about network members’ receptivity to hearing information specifically from them. Participants felt that their network members would be receptive to discussing dementia risk reduction with them if the participant already regularly provided health information to their network members. In these cases, participants perceived themselves to be health opinion leaders within their social network.

“I’ve got a reputation for being interested in medical stuff … whenever somebody’s talking about their medication or something like that, they say “oh talk to [Participant’s name] - she’s our medical person.” … [The MOOC is] the first thing I think of when I see them: what haven’t I told them from last week?” – P01

On the other hand, participants who did not have an established pattern of discussing health information were reluctant to provide dementia risk reduction advice because they felt this advice would be better received if it came from a medical professional.

“if [my friend] thinks “oh - I can’t think of this bloke’s name,” I’d probably say to him “oh look it’ll come to you, but if you’re having constant trouble like this, maybe you need to see your doctor” - that’s about as far as I’d go - I’m not the fount of all wisdom and I don’t want to appear arrogant to my friend” – P038

Perceived stigma

Some participants felt that negative perceptions of dementia in the community reduced people’s receptivity to information about the MOOC and/or dementia risk reduction.

“one thing that I found interesting was that dementia’s not a topic of conversation … dementia seems to be something people don’t like to talk about … it’s a big fear … It’s not really a discussed topic for anyone who doesn’t have dementia directly part of their lives already … ” – P023

For some participants the stigma surrounding dementia increased their motivation to talk about dementia and dementia risk reduction:

“I guess I believe [that] change only occurs if things are de-stigmatised, and people talk about them. … we need talk about it [dementia] otherwise it can’t be de-stigmatised and people won’t think about it and do something about it … I think many people think its something that’s inevitable, so I guess they need to be educated” – P021

Conversation Partner Responses

After participants initially introduced the course and/or dementia risk reduction as a topic of conversation, network members’ responses guided the next stages of information sharing.

“I don’t like preaching on a soap box … if they… come up with questions or if they’re interested then I’ll pursue it, but otherwise I won’t” – P022

Engagement

After first hearing about the course, some network members asked for additional information, or began regularly asking participants to update them with any new information they had learnt between conversations.

“when I told her I’d just finished the preventing dementia one, she was like - it was almost like a secret - she said “are you allowed to tell me what I can do to prevent dementia?” So I just went through the list of “don’t do this, don’t do that” – P011

“[one friend] said “oh I don’t want to do it [the course] - but I want to hear about it - tell me what you’re learning each week” … on our walk I’d say “well, I learnt this, this and this, this week””- P039

Redirection

Some network members directed conversations to related topics that were more pertinent to them. For example, one participant recounted having a conversation re-directed toward strategies for living with dementia when talking to a network member whose mother was living with dementia.

“I told her about [the PDMOOC] and she said “if there’s anything that’ll be of benefit [to her mother who is living with dementia]” …But I couldn’t in a sense … [because] It’s too late to prevent it happening” – P08

Some network members asked questions about the process of completing the course but did not show an interest in hearing about dementia or dementia risk reduction. This directed conversations into a brief discussion of the course, but did not provide an opportunity to discuss dementia risk reduction:

“[I found that most people] don’t want to delve into any details on what causes it and what’s the result of it and how do you try and avoid it - nothing like that - just “Oh yeah you did that course - ok - how’d you do that” And I just explain [the course] to them, you know.” – P038

Disinterest

Some respondents recalled network members having no interest in hearing about the course, dementia risk reduction, or dementia more generally.

“I told them when I started the course, and when I’m on my first module but they don’t show any interest, so I never continued with [the conversation].” – P03

Sometimes participants’ attributed network members’ reluctance to discuss dementia risk reduction to their stigmatized view of dementia:

“[my family] are not very comfortable talking about it [dementia] - they feel the need to sort of joke about it and make light of it” – P028

Discussion

Information about dementia risk reduction was largely shared in everyday social interactions, in accordance with established communication theories. Aligning with social exchange and social capital theories (Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, Citation2002; Pilerot, Citation2012), anticipating and/or receiving positive feedback was important for information sharing. Participants preferred to share information with discussion partners perceived as receptive, and they pursued (or abandoned) conversation topics based on discussion partners’ responses. Dementia stigma produces social norms where dementia is viewed as an unacceptable conversation topic (Werner, Citation2014), limiting perceived and actual receptivity to dementia risk information. In line with the stereotypes identified in previous studies (Curran et al., Citation2021), participants generally considered women and older people as more receptive to information about dementia risk reduction.

Dementia risk information was considered relevant to some conversation partners because of perceived interest in participants’ lives. Participants frequently interacted with these conversation partners, and they were therefore likely to be participants’ closest network members (Perry, Pescosolido, & Borgatti, Citation2018). Relational rewards in very close relationships may be related more to the act of having a conversation than to the content of that conversation (Huisman, Joye, and Biltereyst Citation2020), or may be perceived as unimportant (Lewis, DeVellis, and Sleath Citation2002). These concepts may explain the sharing of dementia risk information with close network members who were not perceived to have a specific interest in this subject.

Opinion leadership (Valente & Pumpuang, Citation2007), an expression of power dynamics (Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, Citation2002), was identified among the drivers of dementia risk information sharing. Expert power (perceiving information providers as more knowledgeable than oneself) and referent power (perceiving information providers as similar to oneself) contribute to influential health communication (Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, Citation2002; van Ryn & Heaney, Citation1997). Both were important for dementia risk information sharing, with participants choosing to discuss dementia risk reduction in relationships where they perceived themselves as health opinion leaders (expert power), and in relationships where there were shared characteristics (referent power).

Strength-of-weak-ties theory suggests that a more diverse audience will be reached through weaker ties compared to stronger ties, as people’s closer contacts tend to be similar to themselves (Granovetter, Citation1973). Huisman, Joye, and Biltereyst (Citation2020) reported that health information tends to be shared almost entirely through strong ties. We found that dementia risk information is shared through both close and weak ties, and that the same drivers apply in both contexts. This is an important finding, as adapting dementia risk reduction initiatives to increase information sharing will likely impact sharing through both closer and weaker ties.

Understanding the drivers of information sharing may allow dementia risk reduction messaging to be adapted to increase sharing. Information in the PDMOOC is factual, academic, and delivered by highly educated international experts of a similar age to participants. Increasing diversity of information and presenters may help overcome the stereotypes that inform perceptions of information relevance (Finnegan, Oakhill, & Garnham, Citation2015). For example, risk reduction initiatives could include personal accounts of experiencing dementia and dementia risk reduction delivered by lay people of a variety of ages, which could both encourage emotional traction and broaden perceptions of information relevance (Prochaska et al., Citation2019). Dementia risk reduction initiatives may also benefit from operating alongside stigma reduction initiatives to create social climates where discussing dementia is more acceptable. For example, mass media campaigns could include both dementia risk reduction messaging (Talbot et al., Citation2021; Van Asbroeck et al., Citation2021) and destigmatising dementia narratives (Bacsu et al., Citation2021; Zheng, Chung, & Woo, Citation2016). As noted by some participants, conversations about dementia risk reduction may themselves assist with this process of de-stigmatization.

Limitations

We have produced a model of information sharing that we hope will be utilized to increase the sharing of preventative health information, based on participants’ rich accounts of their information sharing experience. However, limitations in the representativeness of the sample must be considered when applying insights from this study in other contexts. The self-selecting participants interviewed in this study, while similar to the participants in the PDMOOC and other dementia risk reduction and health promotion initiatives (Farrow, Fair, Klekociuk, & Vickers, Citation2022), were not fully representative of all PDMOOC participants, comprising more older people and less health workers (Farrow, Fair, Klekociuk, & Vickers, Citation2022). It is likely that participants who were enthusiastic about the MOOC, and therefore inclined to discuss the MOOC, were oversampled in this study. The interviewer (HF) identified reflexively that her membership of the course delivery institution may have promoted positive reports of the course and of information sharing behavior, especially among participants with whom the interviewer felt most affinity (social desirability bias) (Latkin, Edwards, Davey-Rothwell, & Tobin, Citation2017). However, one participant reported that they did not find the MOOC valuable, and a mix of men and women were interviewed, allowing exploration of a range of participant perspectives. Complementary analysis of feedback survey responses from a larger group of PDMOOC participants show that information sharing is common among PDMOOC participants (Fair, Klekociuk, Eccleston, Doherty, & Farrow, Citation2022), indicating that information sharing is widespread among larger groups of PDMOOC participants.

Health promotion campaigns, including dementia risk reduction campaigns, use a variety of methods to provide health information and promote healthy behavior. These include MOOCs, other online courses, mass media campaigns, and social media campaigns (Claflin et al., Citation2021; Talbot et al., Citation2021), all of which tend to reach a group with limited demographic diversity (Fair, Doherty, Klekociuk, Eccleston, & Farrow, Citation2021). Information sharing may therefore increase the impact and equity of a wide variety of health promotion initiatives (Fair, Doherty, Klekociuk, Eccleston, & Farrow, Citation2021). However, this study only investigated information sharing among one group of PDMOOC participants. While the identified drivers of sharing may apply to other participants and other dementia risk reduction initiatives, further investigations are necessary to confirm this, and to identify additional initiative-specific drivers of information sharing.

This study did not capture the fidelity of shared information or its efficacy in promoting behavior change. While discussion partners were regularly reported to respond positively to shared information, social desirability may have driven these responses (Kelman, Citation1974; Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, Citation2002). Being informed about health information is an antecedent to internalizing information and adopting behavior (Armitage & Conner, Citation2000; Brunet, Abi-Nader, Barrett-Bernstein, & Karvinen, Citation2021; Claflin et al., Citation2021; Guan, Citation2021; Rogers, Citation2003; Spronk, Kullen, Burdon, & O’connor, Citation2014), and complex health behavior change often requires multiple exposures to multiple messages from multiple sources (Finnegan & Viswanath, Citation2002). Conversations about dementia risk may therefore impact discussion partners, however the nature of this impact remains to be elucidated.

Finally, this study was conducted during a period of COVID-19 containment measures which limited physical gatherings of people, especially when network members lived outside of Tasmania. However, physical locations were not identified as a driver of dementia risk information sharing, and conversation opportunities overall were reportedly both positively and negatively impacted by COVID-19 containment measures, therefore the findings of this study may not have been heavily impacted by the COVID-19 containment context.

This was a study into the spontaneous undirected sharing of information after participation in a dementia risk reduction initiative. The drivers identified in this study would therefore be expected to be different and more complex (Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, Citation2002) if information sharing was prescribed or encouraged as part of initiative participation.

Conclusion

Among the group of PDMOOC participants interviewed, information sharing about dementia risk reduction and/or the MOOC was driven by both parties involved in the exchange: participants’ course experiences; the opportunities participants had to discuss topics that impacted them with network members who were perceived to be receptive, within the boundaries of power dynamics and perceived social norms; and network members’ responses to given conversation topics. Understanding these drivers may allow adaptation of dementia risk education campaigns to increase sharing, for example by altering participants’ perceptions of appropriate conversation partners, by increasing emotional engagement, or by addressing stigma. The drivers identified in this study align with communication theories and may therefore also apply in other preventative health settings, warranting further investigation in a range of contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants for their contributions to this study, and the team behind the development and delivery of the PDMOOC for their dedication to positive participant experiences.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2023.2179136

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amirkhanian, Y. A., Kelly, J. A., Kabakchieva, E., Kirsanova, A. V., Vassileva, S., Takacs, J. … Mocsonaki, L. (2005). A randomized social network HIV prevention trial with young men who have sex with men in Russia and Bulgaria. AIDS, 19(16), 1897–1905. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000189867.74806.fb

- Archibald, M. M., Ambagtsheer, R. C., Casey, M. G., & Lawless, M. (2019). Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 160940691987459. doi:10.1177/1609406919874596

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2000). Social cognition models and health behaviour: A structured review. Psychology & Health, 15(2), 173–189. doi:10.1080/08870440008400299

- Bacsu, J. -D., Johnson, S., O’connell, M. E., Viger, M., Muhajarine, N., Hackett, P. … McIntosh, T. (2021). Stigma reduction interventions of dementia: A scoping review. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 41(2), 1–11. doi:10.1017/S0714980821000192

- Bartlett, L., Brady, J. J. R., Farrow, M., Kim, S., Bindoff, A., Fair, H. … Sinclair, D. (2021). Change in modifiable dementia risk factors during COVID‐19 lockdown: The experience of over 50s in Tasmania, Australia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 7(1). doi:10.1002/trc2.12169

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis (pp. 843–860). Springer Singapore.

- Brunet, J., Abi-Nader, P., Barrett-Bernstein, M., & Karvinen, K. (2021). Investigating physical activity knowledge and beliefs as correlates of behaviour in the general population: A cross-sectional study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 26(4), 433–443. doi:10.1080/13548506.2020.1745250

- Claflin, S. B., Klekociuk, S., Fair, H., Bostock, E., Farrow, M., Doherty, K., & Taylor, B. V. (2021). Assessing the impact of online health education interventions from 2010-2020: A systematic review of the evidence. American Journal of Health Promotion, 36(1), 089011712110393. doi:10.1177/08901171211039308

- Complex Data Collective. (2016). Network canvas interviewer (version beta trial) [Computer software].

- Curran, E., Chong, T. W. H., Godbee, K., Abraham, C., Lautenschlager, N. T., Palmer, V. J., & Jepson, R. (2021). General population perspectives of dementia risk reduction and the implications for intervention: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence. PLoS One, 16(9), e0257540. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257540

- Fair, H. L., Doherty, K. V., Klekociuk, S. Z., Eccleston, C. E., & Farrow, M. A. (2021). Broadening the reach of dementia risk reduction initiatives: Strategies from dissemination models. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 14034948211055602. doi:10.1177/14034948211055602

- Fair, H., Klekociuk, S., Eccleston, C., Doherty, K., & Farrow, M. (2022). Interpersonal communication may improve equity in dementia risk education. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. doi:10.1002/hpja.602

- Farrow, M., Fair, H., Klekociuk, S. Z., & Vickers, J. C. (2022). Educating the masses to address a global public health priority: The preventing dementia massive open online course (MOOC). PLoS One, 17(5), e0267205. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267205

- Finnegan, E., Oakhill, J., & Garnham, A. (2015). Counter-stereotypical pictures as a strategy for overcoming spontaneous gender stereotypes. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01291

- Finnegan, J. R., & Viswanath, K. (2002). Communication thoery and health behaviour change. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & F. M. Lewis (Eds.), Health behaviour and health education (3ed, pp. 240–264). New Jersey: Jossey-Bass.

- Froehlich, D. E., & Brouwer, J. (2021). Social network analysis as mixed analysis. In A. J. Onwuegbuzie & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Routledge Reviewer’s guide to mixed methods analysis (1ed, pp. 209–218). New York: Routledge.

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. The American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469

- Guan, M. (2021). Sexual and reproductive health knowledge, sexual attitudes, and sexual behaviour of university students: Findings of a Beijing-based survey in 2010-2011. Archives of Public Health, 79(1). doi:10.1186/s13690-021-00739-5

- Hansen, J. D., & Reich, J. (2015). Democratizing education? Examining access and usage patterns in massive open online courses. Science, 350(6265), 1245–1248. doi:10.1126/science.aab3782

- Horst, B. R., Furlano, J. A., Wong, M. Y. S., Ford, S. D., Han, B. B., & Nagamatsu, L. S. (2021). Identification of demographic variables influencing dementia literacy and risk perception through a global survey. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 660600–660600. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.660600

- Huisman, M., Joye, D., & Biltereyst, S. (2020). Sharing is caring: The everyday informal exchange of health information among adults aged fifty and over. Information Research, 25(3). doi:10.47989/irpaper870

- Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (2017). Personal Influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communications (1ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Kelman, H. C. (1974). Further thoughts on the processes of compliance, identification, and internalization. In H. C. Kelman (Ed.), Social power and political influence (1ed, p. 47). New York: Routledge.

- Latkin, C. A., Edwards, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., & Tobin, K. E. (2017). The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 133–136. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.005

- Lewis, M. A., DeVellis, B. M., & Sleath, B. (2002). Social influence and interpersonal communication in health behaviour. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & F. M. Lewis (Eds.), Health Behaviour and Health Education (3 ed, pp. 240–264). New Jersey: Jossey-Bass.

- Liu, M., Yang, Y., & Sun, Y. (2019). Exploring health information sharing behavior among Chinese older adults: A social support perspective. Health Communication, 34(14), 1824–1832. doi:10.1080/10410236.2018.1536950

- Mao, B., Morgan, S. E., Peng, W., McFarlane, S. J., Occa, A., Grinfeder, G., & Byrne, M. M. (2021). What motivates you to share? The effect of interactive tailored information aids on information sharing about clinical trials. Health Communication, 36(11), 1388–1396. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1754588

- Nolan, K., Schall, M. W., Erb, F., & Nolan, T. (2005). Using a framework for spread: The case of patient access in the veterans health administration. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 31(6), 339–347. doi:10.1016/S1553-7250(05)31045-2

- Perry, B. L., Pescosolido, B. A., & Borgatti, S. P. (2018). Egocentric network analysis: Foundations, methods, and models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pilerot, O. (2012). LIS research on information sharing activities – people, places, or information. Journal of Documentation, 68(4), 559–581. doi:10.1108/00220411211239110

- Prochaska, J. J., Gates, E. F., Davis, K. C., Gutierrez, K., Prutzman, Y., & Rodes, R. (2019). The 2016 tips from former smokers® campaign: Associations with quit intentions and quit attempts among smokers with and without mental health conditions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(5), 576–583. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty241

- Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C. A., & Evers, K. E. (2002). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & F. M. Lewis (Eds.), Health Behaviour and Health Education (3ed. pp. 240–264). New Jersey: Jossey-Bass.

- Reich, J, and Ruipérez-Valiente, J A. (2019). The MOOC pivot. Science, 363(6423), 130–131. doi:10.1126/science.aav7958

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5 ed). New York: Free Press.

- Spronk, I., Kullen, C., Burdon, C., & O’connor, H. (2014). Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. The British Journal of Nutrition, 111(10), 1713–1726. doi:10.1017/S0007114514000087

- Starmann, E., Heise, L., Kyegombe, N., Devries, K., Abramsky, T., Michau, L. … Collumbien, M. (2018). Examining diffusion to understand the how of SASA!, a violence against women and HIV prevention intervention in Uganda. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 616. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5508-4

- Talbot, L. A., Thomas, M., Bauman, A., Manera, K. E., & Smith, B. J. (2021). Impacts of the National Your Brain Matters Dementia Risk Reduction Campaign in Australia Over 2 Years. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 82(3), 1219–1228. doi:10.3233/JAD-210317

- Valente, T. W., & Pumpuang, P. (2007). Identifying opinion leaders to promote behavior change. Health Education & Behavior, 34(6), 881–896. doi:10.1177/1090198106297855

- Van Asbroeck, S., van Boxtel, M. P. J., Steyaert, J., Köhler, S., Heger, I., de Vugt, M. … Deckers, K. (2021). Increasing knowledge on dementia risk reduction in the general population: Results of a public awareness campaign. Preventative Medicine, 147, 106522. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106522

- van Ryn, M., & Heaney, C. A. (1997). Developing effective helping relationships in health education practice. Health Education & Behavior, 24(6), 683–702. doi:10.1177/109019819702400603

- Vrijsen, J., Matulessij, T. F., Joxhorst, T., De Rooij, S. E., & Smidt, N. (2021). Knowledge, health beliefs and attitudes towards dementia and dementia risk reduction among the Dutch general population: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10913-7

- Werner, P. (2014). Stigma and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of evidence, theory, and methods. In P. W. Corrigan (Ed.), The stigma of disease and disability: Understanding causes and overcoming injustices (pp. 223–244). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- World Health Organization. (2017). Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-action-plan-on-the-public-health-response-to-dementia-2017—2025

- World Health Organization. (2021). Global status report on the public health response to dementia. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033245

- Zheng, X., Chung, J. O., & Woo, B. K. (2016). Exploring the impact of a culturally tailored short film in modifying dementia stigma among Chinese Americans: A pilot study. Academic Psychiatry, 40(2), 372–374. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0397-7

- Zimmerman, M. S., & Shaw, G. (2020). Health information seeking behaviour: A concept analysis. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 37(3), 173–191. doi:10.1111/hir.12287