Abstract

This paper explores the interactions between theory and practice and between discipline and profession in the public administration and management community. It argues that it is unhelpful to seek hegemony for either concept or domain in these dyads. Rather it argues for a praxis ecosystem approach that explores the interactions between these elements. It argues that tension and conflict within the praxis ecosystem is natural and to be expected—and may well drive forward both theory and practice and the discipline and profession. The key task with the ecosystem is thus to govern these tensions rather than seek to eradicate them. It ends by exploring what this approach means in practice for praxis ecosystems.

Keywords:

Introduction

Public administration and management (PAM), like many academic fields of study, is preoccupied with two inter-locked sets of tensions: those between theory and practice and those between discipline and profession. These tensions are the subject of this paper. Other approaches, discussed below, have sought to resolve them, by seeking hegemony for one or other of them. Our argument is different. Rather we argue that these frictions are entirely natural and indeed are essential to the development of the PAM research and practice communities. Subsequently we offer the praxis ecosystem as a framework through which to understand and mediate them.

Our paper begins by exploring the tensions between discipline and profession and between theory and practice within PAM and by considering the outcomes of these tensions. It argues that the simple resolution of these tensions is neither possible nor desirable. As an alternative it evolves a model of the praxis ecosystem within which these tensions coexist. Such coexistence within the praxis ecosystem offers the potential for the creative evolution of PAM. However the possibility that this coexistence can also lead to deleterious outcomes is ever-present. Thus the key task within the praxis ecosystem is not to seek the hegemony, either of discipline or profession or of theory or practice. Rather it is the governance of these tensions to maximize their creative potential and minimize their destructive potential. In conclusion, our paper offers an example of this praxis ecosystem in practice and discusses its implications for theory and practice.

Current state of play

PAM as a discipline and profession

An academic discipline claims authority over a segment of knowledge and is committed to theory building (Van de Ven & Johnson, Citation2006), whilst a profession is “the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served.” (Epstein & Hundert, Citation2002). The tension between PAM as a discipline and a profession has long been at the heart of the evolution of PAM. This was crystallized in the 1952 “Simon—Waldo” debates (Harmon, Citation1989). Simon, in his treatise on administrative science (Simon, Citation1947), argued for the focus to be upon the evolution of discipline-based theory that is consensual and that contributes to the evolution of the social sciences (Raadschelders, Citation2019). Waldo, by contrast, argued for the evolution of PAM as a profession, with a focus upon the craft of application (Waldo, Citation1948; see also Marini, Citation1993).

Harmon (Citation1989) considered the debates between Simon and Waldo as “a draw,” with the disputation continuing into the twenty-first century—and showing no sign of abating (e.g., Chijioke, Ikechukwu, & Aloysius, Citation2021; Van der Waldt, Citation2016). In a key paper, Dubnick (Citation2018) has argued that the divide between “those that favor the practice [of PAM] and those who adhere to the discipline is growing with both sides entrenching into their own academic communities.” He subsequently argued for a resolution of this dyadic approach within PAM by its scholars engaging with “the formative discourses of the social sciences”—though it is not entirely clear how this resolution would emerge.

Theory and practice in PAM

Cross-cutting the above relationship between discipline and profession in PAM is that between theory and practice. In this context, theory is denoted as “a set of assumptions claiming to offer an interpretation of a phenomenon” (Starke Jr., Citation2018), whilst practice is the application of knowledge within a professional setting (Chaiklin & Lave, Citation1993). Here, there is an enduring consideration of the extent to which PAM theory can, or even should, underpin effective professional practice by public administrators and managers. The relationship between theory and practice is contested. Some critics have maintained that theory is essential to provide a framework for effective PAM practice, as a process of sense making through research, whilst others have argued that there continues to be a significant disconnect between PAM theory as an essential component of the academic discipline and PAM as a field of professional practice (Walker, Chandra, Zhang, & Witteloostuijn, Citation2019).

Theory, practice, discipline and profession in interaction

On the research and theory-oriented side of PAM, the debate concerns how to ensure its future as an academic discipline within the social sciences and on the basis of knowledge derived from research (e.g., Barzelay & Thompson, Citation2010; Wright, Citation2015). From this perspective the requirement of PAM to have direct relevance to practice is a brake on the evolution of research-based knowledge—and thence of the discipline. Meier (Citation2015), for example, has lamented that too much PAM scholarship is concerned with practical problems and too little with theory building, with the former constraining the development of the latter. He concluded that:

Much of the time of public administration scholars is devoted to training individuals for practice or contributing directly to government programs by offering advice or doing applied research rather than producing… scientific scholarship… Public administration faces its own version of bounded rationality constrained by limited resources and problems that are not amenable to quick and final solutions. (Meier, Citation2015, p. 21)

In contrast, O’Leary, Van Slyke, and Kim (Citation2011) opined that the key debate at the 2011 Minnowbrook Conference was whether public administration “had any relevance to life outside the ivory tower,” and how such relevance could be advanced.

Little consensus has emerged in this debate. Thus Van der Waldt (Citation2017) has argued that theory is an essential precursor for good practice and for the evolution of the PAM profession. In contrast, Mitchell (Citation2018) has argued that there is a “substantial disconnect” between theory and practice in PAM. Consequently, he argued for a reorientation of PAM away from a pre-occupation with theory and to become led by practice and by the profession.Footnote1

A linked but distinct argument emerged in the Minnowbrook at 50 Conference in the US in 2018. This is that PAM theory wants to be relevant to practice but currently fails in this attempt:

The study of public administration is increasingly characterized by compartmentalization, institutional incentives that do not reward practitioner relevance, rigid and narrow definitions of productivity, and methodological sophistication—all of which discourage scholarly risk taking, creativity, and innovation, and make research less interesting and informative to practitioners. Practitioners lack the resources, time, and motivation to access research trapped behind paywalls, and scholars who want to communicate their research more broadly are limited in their options. Finally, perhaps because of a desire to remain politically neutral, public administration professional associations are largely invisible in political debates, creating another barrier to reaching important audiences. (Nabatchi & Carboni, Citation2019, p. 23)

Pettigrew (Citation2005), Head (Citation2010) and Taylor, Torugsa, and Arundel (Citation2018) have all made similar arguments for a practice-centred perspective within the PAM community, with Head in particular calling for PAM research and theory to pay more attention to real-world challenges rather than to theory building. Drawing on Schon (Citation1983), Head argued that that improved engagement with practice “will enable researchers to navigate better the ‘swamp’ of complex and wicked problems, rather than be content with theory-building on the ‘high ground’.”

Interim conclusions

This brief review has shown PAM as existing at the cusp of two inter-twined tensions—between theory and practice and between discipline and profession. Despite iterative attempts during the second half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century, little progress has been made in resolving these dyadic counter-positions. Underpinning these tensions has been an epistemological one between the scientific positivist and social constructivist perspectives on PAM research and theory: the former being traditionally reliant on detached scientific evaluations and theory building (Whetsell & Shields, Citation2015), while the latter proposes to explore the PAM practice from insiders’ and practitioners’ perspectives (Hay, Citation2011). Finally, the evolution both of “practice-based studies” and “practice –based theorizing” in the broader organization studies literature has also challenged this dichotomy and has promoted the argument for practice as a key driver of theory rather than being in dyadic opposition to it (e.g., Gheradi, Citation2019).

These perspectives are brought together in . This explores the tensions between PAM as a discipline and a profession (domain) and between building theory and informing practice (mode). These tensions offer the potential for the generation of four different types of information (knowledge). First, as a discipline PAM can lead to knowledge as formal theory building, seen as an end in its own right. This might be through positivist research that is the basis of the “scientific method” (Van der Waldt, Citation2017) or through postmodern and social constructivist approaches to PAM (for example, Ospina & Dodge, Citation2005, Miller & Fox, Citation2007, Guy & Mastracci, Citation2018). It can also derive from attempts to understand positivism from a postmodern or social constructivist perspective (Ryan, Citation2015).

Table 1. The domains and modes of PAM and their knowledge outcomes.

Second, PAM can also build itself as an academic discipline but with greater emphasis on this discipline as generating knowledge and theory from empirical research—but with the explicit aim of informing and/or improving practice, through practice-based studies. These seek to unlock the “sticky knowledge” and expertise of practitioners (Gheradi, Citation2019). This is the territory of Head’s (Citation2010) call, above, for practice-based research and theory that will enhance the achievement of the aspirations of public policy. A good example of the former is Potter et al. (Citation2006) exploration of practice-based research and theory for public health.

Third, and moving to the domain of PAM as a profession, this may still lead to theory building, but on the basis of knowledge derived from practice-based research and through practice-based theorizing. Gherardi (Citation2000), along with other writers (for example, Raelin, Citation2007, Geiger, Citation2009), has distinguished between practice as a locus for empirical work that may ultimately lead to formal theoretical development (i.e., practice-based studies) and practice-based theorizing. This latter case is where “practice,” rather than “actors” or “institutions,” is the focus for research and theory. A good example of such practice-based theorizing is Fuglsang’s (Citation2021) work on the practices of innovation in public services.

Fourth, and finally, PAM as a profession may eschew theory-building in its entirety and instead focus upon using practice-based knowledge to improve professional practice. This can occur in two ways. On the one hand it can be through the development of professional standards and guidelines that are based upon professional experience (Sarker et al., Citation2018). This might cover, for example, such cross-cutting issues as ethical standards for public office holders (Svara, Citation2014, Committee on Standards in Public Life, Citation2021). On the other hand, it can be through the development of the reflective practitioner who evolves their practice by exposure to practice-based research and theory (Cook-Sather, Citation2015, Glennon, Hodgkinson, & Knowles, Citation2019).

thus brings together these domains and modes of PAM, and the forms of knowledge that they can generate. As is apparent from our prior discussion, there are weighty debates about the tensions between these domains, modes and forms of knowledge within PAM and how to resolve them. However, it is not our intention here to resolve them. Rather, our purpose is entirely the opposite. It is to argue that the tripartite tensions between theory and practice, between disciplinary and professional aspirations, and between the different forms of knowledge that they generate, are entirely normal and healthy for a vibrant discipline and profession such as PAM. They are found equally in similar academic and professional fields that lie at the cusp of theory and practice, such as medicine (e.g., Alderson, Citation1998, Rogers & Hutchison, Citation2017) or architecture (Hubbard, Citation1995, Suoranta, Aura, & Katainen, Citation2002). The core disciplinary/professional task is not to resolve these tensions away but rather is one of governance. It is to mediate these tensions and relationships and to develop both the discipline and the profession through such mediation.

This is not to say that such governance will always have positive results. It may also lead to destructive and damaging relationships where researchers/theorists and practitioners ‘retreat to their own corners,’ in despair at the other side. Consequently and subsequently, we offer a praxis ecosystem framework to understand the interaction and governance of these tensions. Such an approach, we argue, is most likely to optimize the creative capacity of these tensions and minimize, if not eliminate, their destructive potential.

Praxis

Praxis posits a dynamic relationship between theory and practice. In a seminal paper, Jun (Citation1994) argued that “practice” can take place without an individual employing any type of critical consciousness. “Praxis,” however, requires “a reflexive, critical consciousness to discover and create future possibilities.” Thus, praxis

…can be defined as human activity in which an individual uses a reflexive consciousness. In praxis, action requires critical consciousness. Only humans as conscious beings, are able to relate to themselves and the world reflexively, that is, to reflect, analyse, foresee, and decide their course of action. (Jun, Citation1994, p. 202)

Praxis thus requires both the development of a sound body of disciplinary theory that is relevant to practice and a commitment from the profession to engaging with such theory as a basis for professional practice.

Subsequent writers have emphasized that the achievement of praxis is not easy. Zanetti (Citation1997), for example, has argued for praxis as a core element of PAM as a discipline and a profession. However she has also contended that the “scientific” theory-building fixations of PAM as a discipline have hindered the effective evolution of praxis across PAM as a discipline and profession—a position subsequently articulated and developed by other writers (e.g., Bushouse & Sowa, Citation2012).

Our position, as discussed above, is that there are indeed inevitable tensions both between theory and practice and between discipline and profession. However, it is both incorrect and unnecessary to reduce these tensions to simple linear dyadic oppositions. Instead, we argue for an ecosystem approach that understands how theory, practice and praxis co-exist, conflict and evolve. Theory and practice do indeed have their own spaces, where the other can be an unwelcome or reluctant guest. Equally both can interact, if with friction. Similarly the discipline and profession of PAM can have different trajectories—but arguably both require the other to enhance their legitimacy. Effective praxis evolves at the interface of this interaction where the necessity of, and tension between, theory and practice is recognized by both discipline and profession in the generation and use of knowledge. Echoing Giddens (Citation1984), we see this relationship as fluid and contestable, where multiple versions of theory and practice can coexist as praxis evolves. This occurs within the praxis ecosystem.

The praxis ecosystem

Ecosystem approaches

The metaphor of the “ecosystem” has become a prevalent one in contemporary management theory, for example in strategic management (Adner, Citation2017), innovation studies (Granstrand & Holgersson, Citation2020), and service marketing and management (Vargo, Akaka, & Vaughan, Citation2017). All draw upon the metaphor of dynamic, interactive and self-sustaining ecological ecosystems, first developed by Tansley (Citation1935), to understand complex ecological environments.

offers a stylized example of an ecological ecosystem where living and non-living elements co-exist and are dependent upon each other. The sun and the weather elements, for example, are necessary for plants to grow—which themselves are necessary for rabbits to eat and thrive. Elements of the ecosystem may prey on each other—but their continued existence as part of the ecosystem is essential to its sustainability. An ecosystem, if self-balancing, is hence not always harmonious. The hunting bird may hunt small rodents, for example. These rodents for their part are reliant upon the consumption of insects or vegetative matter in the ecosystem, in order to survive and thrive. In turn the carcasses of these small rodents are also necessary for the essential bacteriological growth and evolution that is essential to sustain plant life within the ecosystem. Providing that the ecosystem does not become unbalanced (such as by the hunting bird eradicating all rodents within it or through outside intervention), it is self-sustaining.

The public service ecosystem (PSE)

Within PAM theory, systemic approaches have a long history (Knapp, Citation1984), and context has also been an enduring pre-occupation (Pollitt, Citation2013). These are important elements of the ecosystem approach, but this approach goes further—both to explore the interplay of context and system and to examine this interplay across differing levels of the ecosystem. Strokosch and Osborne (Citation2020; see also Petrescu, Citation2019, Leite & Hodgkinson, Citation2021) offered an empirical exploration of PSEs and concluded that they

…move us beyond the transactional and linear approach associated with [the New Public Management], towards a relational model where value is shaped by the interplay between all of these dimensions and not least by the wider societal context and the values that underpin it. (p. 436)

Rossi and Tuurnas (Citation2021) have subsequently argued that PSEs reveal the complexity of value creation conflicts, whilst Kinder, Six, Stenvall, and Memon (Citation2022) and Kinder, Stenvall, Six, and Memon (Citation2021) have explored learning and leadership within them and argued that PSEs have now replaced networks as the most persuasive framework for understanding public service delivery. Finally Osborne, Nasi, and Powell (Citation2021) and Cui and Osborne (Citation2022) have explored respectively the elements of value and value creation and of value destruction within PSEs.

The most evolved model of the PSE is probably that of Osborne, Powell, Cui, and Strokosch (Citation2022), from a value creation perspective. They present a heuristic of the PSE over four interacting level: the macro-level of societal values, rules and norms, the meso-level of organizational actors, networks and norms/processes, the micro-level of the individual actors in public service delivery, and the sub-micro-level of individual/professional beliefs and values.

Our argument is that, just as the ecosystem is an effective heuristic for understanding and engaging with the complexities of public service delivery, it is also effective in promoting the understanding of the relationships and tensions both between discipline and profession and between theory and practice in PAM. At the heart of these tensions is the role of knowledge.

Exploring the praxis ecosystem

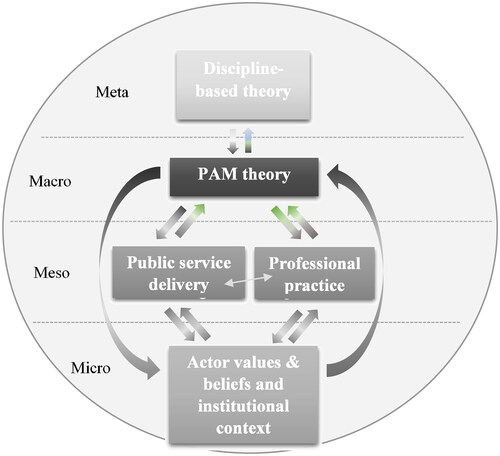

Our praxis ecosystem is presented in . Like the PSE, it comprises four levels, though we denote them slightly differently. The meta-level comprises the social science disciplines that PAM draws upon—they are essential for knowledge to exist within the praxis ecosystem but are often invisible to the naked eye. The New Public Management, for example, drew upon both political theory, in the form of Public Choice theory, and management theory, in the form of Principal—Agent theory (Ferlie, Citation2017), whilst behavioral public administration draws strongly on the discipline of social psychology (Grimmelikhuijsen, Asmus, Olsen, & Tummers, Citation2017). Nor is the relationship one-way. The theoretical elaboration of Public Service Logic has enriched the understanding of the conceptualization of “value” in one of its root disciplines—service management and marketing (Osborne, Citation2021).

The macro-level of our praxis ecosystem comprise the complex and diverse world of PAM theory. This focal theory is at the nexus between the disciplinary theory and the world of public service delivery and professional practice. It can enrich, and be enriched, by both (Quadrants I and III in ). PAM theory can enhance practice through sense making, by offering reflective practitioners concepts and tools through which to understand and engage with their practice, whilst practice can offer a locus in which the empirical work that drives PAM theory development can take place (Quadrants II and IV in ). Theory and practice on performance management within public service organizations (PSOs), for example, has evolved through this creative tension (Van Dooren, Bouckaert, & Halligan, Citation2015). Equally though this tension can be destructive and lead to a breakdown between theory and practice, as Mitchell (Citation2018) has argued in the case of strategic management.

Our third level of our praxis ecosystem is the meso-level level of actually existing public services and PSOs, and where the professional practice/craft of PAM is enacted. As discussed above, it is also where empirical research is conducted. These elements often interact each other. As noted above, this level can provide the empirical context that can drive both formal theory making and practice-based theorizing. It can also be the environment where reflective practitioners take theory into practice to enhance this practice. It is important to note that this level comprises the loci both of public service delivery and of professional practice. This level is thus the nexus where discipline and profession and theory and practice interact and which interaction can evolve new forms and uses of knowledge.

Finally, the fourth level of our ecosystem is the micro-level. This comprises the beliefs and values of all within the ecosystem—researchers, theorists and practitioners. These personal and professional beliefs and values will enable and constrain not only their actions as researchers, theorists and/or practitioners, but also their interactions. If practitioners believe that PAM theory is a distant and unrelated activity to the practice of PAM this will alienate their relationships with both empirical research, and with extant PAM theory. Similarly, if researchers believe that their prime duty is to evolve a coherent body of disciplinary knowledge, irrespective of its utility for/relationship to practice, then this will condition how they engage with practice (or not!).

This level of the ecosystem will also include institutional and societal beliefs about the role and purpose of research and professional practice. These institutional level beliefs can structure and/or constrain the relationships between theory and practice. This might be by defining what are considered “appropriate” outlets for the disciplinary outcomes of research work and/or by structuring the processes through which practitioners can access this work. This point is explored further, below.

Discussion: advantages and challenges of the praxis ecosystem approach

Our approach to the praxis ecosystem in PAM, in wanting to explore the complexity and nuances of praxis rather than reducing it to dualities, is not a lone voice. McDonald III (Citation2018), for example, has argued for the necessity of embracing the inter-relationship of PAM theory and practice rather than reducing it to a duality, whilst Elias (Citation2020) has argued for phenomenology as an approach through which to bridge theory and practice. Both argue that this more nuanced approach will provide a bridge between the domains of the discipline and profession. The unique contribution of our approach is to provide a framework and heuristic through which to explore these myriad relationships/tensions, rather than presenting them as purely dyadic. It also situates the evolution of PAM knowledge within these tensions.

This approach has, we believe, significant advantages. We would highlight six in particular. First, to reiterate, it offers an integrated “praxis” framework, exploring not only the inter-reaction and inter-relationship between theory and practice, but also their relationships with other relevant concepts, such as discipline and profession, (empirical) research, knowledge creation, and beliefs/values. Upwardly, for example, it allows the exploration of the relationship of PAM theory to its disciplinary bases. Downwardly, it also allows the exploration of its relationship to the empirical research from which it has evolved, to professional practice and to the micro-beliefs/values of the key actors within the praxis ecosystem.

Second, and notwithstanding Head (Citation2010) and colleagues, this approach moves beyond the linear and uni-directional “practice-centred” perspective, and highlights rather the inter-action between theory and practice and between discipline and profession. Not only can theory respond to and be derived from practice (Huxham & Hibbert, Citation2011), but theory can also inform practice—such as through the development of reflective practitioners by their exposure to theory in education and training (Cook-Sather, Citation2015; Glennon et al., Citation2019). In this sense it can lead to range of the knowledge outcomes identified in . Similarly, this approach asks questions about the relationship between the discipline and the profession: is the PAM discipline solely concerned with theory building or should this theory be focused on enhancing professional practice? It does not provide an answer to these questions, but rather a framework within which to situate and explore them.

Third, it allows the exploration both of values and of the emotional dimension as core elements of theory and practice. This is through its acknowledgement of the role of values as the micro-level of PAM, and as a legitimate element of the discipline and profession. Thus, Mastracci, Newman, and Guy (Citation2010) and Guy and Mastracci (Citation2018) have argued, for example, that emotions and the affect are an essential though often ignored element of PAM theory. PAM theory cannot be fully developed, they argued, if it ignores “the emotive dimension to living, loving, working, engaging, experiencing, deciding, suffering, and enjoying” (Guy & Mastracci, Citation2018, p. 281). Spicer (Citation2005) has similarly argued for embracing the values of philosophy and history in order to appreciate and develop the PAM discipline. This is a values-based position that has a tension with Simon’s view of PAM theory as a science/social science discipline alone (Simon, Citation1947; see also Neumann Jr., Citation1996) but which also challenges Waldo’s (Citation1948) view on PAM as a practice-oriented profession. The ecosystem approach thence opens up a debate about the relationship between affect and cognition in PAM research and theory and in the creation of disciplinary and professional knowledge.

Fourth, none of this should be taken as suggesting a cosy consensus between theory and practice or between discipline and profession. Indeed tension and antagonism are an essential part of ecological ecosystems: small birds such as sparrows prey on worms and other insects—but are themselves the prey of larger hunting birds. An ecosystem approach to PAM hence recognizes and legitimizes this conflict and tension as an essential element of the evolution of theory and practice. The conflictual debates between Waldo and Simon arguably propelled forward debate about PAM research and theory in a way that consensus never could have. Such conflict is an essential part of any ecosystem. Rather than seeking to resolve this tension by priveleging theory or practice, or discipline or profession, as hegemonic, an ecosystem approach appreciates the “creative destruction,” to borrow a term from innovation studies (Schumpeter, Citation1942), of this tension.

This is not to say that such conflict is always developmental or creative. If handled poorly it can lead to the breakdown of the relationships between theory and practice and between discipline and profession (Dubnick, Citation2018), presaging the collapse of the praxis ecosystem. No ecosystem is ensured of survival, as the experiences of the Amazonian rain-forests have demonstrated (Pereira & Viola, Citation2021). A key task for PAM researchers, theorists, and practitioners is hence to govern the tensions within the praxis ecosystem in order to drive forward the PAM discipline and profession whilst simultaneously ensuring that these tensions do not lead to the collapse of the embodied relationships within the ecosystem. This is a challenging, but not impossible, task—as work in the field of the creative arts has demonstrated (Smith & Dean, Citation2009).

Fifth, our approach allows an awareness of the diverse ways through which theory can develop (e.g., by the adaptation and use of concepts from its root meta-level disciplines, by using meso-level empirical research to test out and evolve theory, and/or by interacting directly with practitioners and the profession (meso-level). This approach makes irrelevant the argument that academic journals are not read by or are not relevant to practice (Wang, Bunch, & Stream, Citation2013). Existing at the boundary between PAM theory and disciplinary theory their function is to drive theoretical development. Other conduits exist for theory to influence practice and the profession—notably through training and education and through direct engagement (such as by consultancy, evidence-based practice, action research, student projects, and/or by researchers serving on the Boards of PSOs) (e.g., Elliot, Robson, & Dudau, Citation2021; Huxham & Hibbert, Citation2011; Lowe, French, Hawkins, Hesselgreaves, & Wilson, Citation2021; Nabatchi & Carboni, Citation2019; Nutley, Walter, & Davies, Citation2007).

This is not to say that such interaction is easy. As Meier (Citation2015) has noted, researchers are time-constrained and must balance the time commitments of contributing to both theory and practice. Similarly practitioners may work to different timescales, and with a commitment to professional standards. Further the languages of both researchers/theorists and practitioners/professionals are embedded in their own distinctive discourses that require translation, both between theory and practice and between discipline and profession (see Sanders & McPeck, Citation1976 for an example of this in the field of education). These trends are especially notable in the evolving post-Covid world (Ansell, Sorensen, & Torfing, Citation2021; O’Flynn, Citation2021; Shand et al., Citation2022).

Finally, an ecosystem approach moves away from an obsession with the dyadic relationships between theory and practice and discipline and profession that often absorbs the PAM community. Rather it explores the multiple interactions between the root disciplines of PAM, its focal theory, empirical research and knowledge, PAM as practice, and the disciplinary and professional values and beliefs that underpin all these elements. Such an approach might be criticized for maintaining that “everything effects everything else.” Our response would be that this is correct. The challenge for any framework or heuristic is to capture this complexity in a way that has utility but which avoids sophistry. To paraphrase Occam’s Razor (Gauch, Citation2003), an effective heuristic needs to be as complex as is required to capture reality and build theory, and as simple (not “simplistic”) as it can be to provide a guide to practice. The praxis ecosystem is precisely that. It structures a space for both discipline and profession to coexist and where their contribution to, and use of, knowledge can be understood.

Conclusion: The ecosystem in practice

To conclude, we offer an example of the praxis ecosystem in action. Papers to academic and research journals (at least, the best ones—papers and journals) will draw upon meta-level disciplines to evolve focal PAM theory. A paper on performance management for example, may draw upon organization theory in developing its argument (Tomazevic, Tekavcic, & Peljhan, Citation2017). It may also subsequently make a contribution to the disciplinary level by evolving this macro-level theory—for example in the work of George, Walker, and Monster (Citation2019) on strategic planning. Although this latter work is embedded with the PAM discipline, it has implications for organization and management studies more broadly. To stretch the ecological metaphor metaphor, just as plants and vegetation require an atmosphere to survive they can also contribute to this atmosphere (perhaps by synthesizing carbon dioxide into oxygen).

At the macro-level, theory-builders and researchers will develop their careers by evolving PAM theory (such as by offering a novel conceptualization or by testing theory through empirical research). A prime route for this will be by publishing in academic journals. Such journals are read primarily by other researchers who will contribute to the discourse by papers confirming or challenging research findings and theoretical development. Increasingly and globally, citation and research impact metrics are used to evaluate the contribution and careers of academics within the PAM discipline, and these metrics in their turn influence the journals that they choose to publish in (e.g., in the fields of healthcare research (Borkowski, Williams, O’Connor, & Qu, Citation2018) and public sector accounting (Guthrie, Parker, Dumay, & Milne, Citation2019)).

However, academics may also choose to publish in journals or social media conduits whose prime mission is to impact upon policy/practice and the PAM profession. Indeed, even core disciplinary journals (such as Public Administration Review) are increasingly requiring authors to specify the import of their work for the profession, as well as for the discipline. Finally, a praxis ecosystem approach also validates the role of practitioners as researchers and the potential for practice-led (as opposed to practice-based) research to contribute to theory, as well as to improved professional practice (see, for example, Kernaghan, Citation2009; and also Whittemore, Citation2015, for an example from the field of planning ).

The meso-level is where the PAM discipline and profession will most interact. “Inter alia,” this can be through a range of mechanisms:

Researchers conducting empirical research to lead to disciplinary development,

Practice–based research that engages with, or is co-produced, with practice, such as action research,

Practice-based research that is co-produced with citizens or public service users, with or without the mediating involvement of practitioners,

Research-based publications in practice and professional journals,

Practitioners who take an academic course at the university (e.g. a MSc in Public Service Management or a MPA) and engage with research material,

PSOs that commission research for their own objectives,

The evolution of professional guidance and standards on the basis of PAM research and theory, and

Practitioners who carry out their own practice-based research that leads to practice-based theorizing.

This is the petri-dish of the praxis ecosystem. It is here that the differing agendas and requirements, and language/discourses, of the discipline and the profession interact. Academics can challenge and change practice and practitioners can challenge and change theory. Both may challenge the legitimacy of the discipline and the profession and/or develop synthesized forms of knowledge and practice. Some will choose to ignore the other or to engage in debilitating/destructive disputes with the other perspective.

The core issue is that consensus and/or agreement should not be expected at this meso-level. For the praxis ecosystem to evolve, such conflict is necessary and inevitable. It should be, if not exactly welcomed, then at least appreciated for its dynamic contribution to theory, practice, discipline, and profession. Just as a sustainable ecological ecosystem requires conflict between elements (an ecosystem might become overrun by rodents and unbalanced, for example, if they are not culled by other animals in the ecosystem), so disagreement, challenge and plain disharmony are necessary for a sustainable praxis. Researchers and practitioners must challenge each other’s disciplinary and professional rules, beliefs and assumptions, if the ecosystem is not to fragment and disintegrate. This process will not necessarily always have positive outcomes. At its worst, it may lead to the destruction of knowledge and breakdown in relationships. It is however an essential component of the praxis ecosystem and should be embraced as such (see for example the work of Vasudeva, Leiponen, and Jones (Citation2020) on conflict in open innovation ecosystems).

Finally at the micro-level, there are the individual and disciplinary/professional beliefs and values of academics and practitioners. These will inform engagement at the meso-level, and may subsequently be themselves changed by this engagement. Whether researchers consider it important to engage with practice will, for example, be a product of their disciplinary training and will condition how they disseminate the knowledge derived from their research.

The institutional element of societal beliefs and values is also important at the micro-level. Significant bodies (governments, research councils, or professional bodies for example) can establish rules or norms that will directly impact research and practice. In Europe, for example, the European Union is evolving a range of rewards and sanctions to support the development of open access by all citizens (not only practitioners) to research findings, rather than having them “hidden” behind the expensive paywalls of publishers (European Commission, Citation2016). Similarly in the UK, the Research Councils, at the behest of the UK Government, are actively privileging impact upon practice as a key determinant of its funding of university-based research (Jones, Manville, & Chataway, Citation2017; Tilley et al., Citation2018). Such initiatives impact the behavior not only of academics, but also of journal editors and publishers.

To conclude, the praxis ecosystem is not a resolution of the tension between research and practice, and between discipline and profession. Rather it is a recognition of the reality of these tensions and their creative potential. This is not to say that the tension will always lead to positive evolution. That is not the real world. Oft-times it can lead to circular and sterile debates between the discipline and the profession, or angry dismissal of one by the other. However the praxis ecosystem does offer a framework within which to situate/govern these inevitable tensions and to appreciate and evaluate their often powerful and creative impact upon the PAM discipline and profession.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen P. Osborne

Stephen P Osborne, Chair in International Public Management and Director of the Centre for Service Excellence, University of Edinburgh Business School, Scotland.

Tie Cui

Tie Cui, Lecturer in Strategy and Digital Innovation, The Business School, Edinburgh Napier University, Scotland.

Katharine Aulton

Katharine Aulton, Teaching Fellow, Centre for Service Excellence, University of Edinburgh Business School, Scotland.

Joanne Macfarlane

Joanne Macfarlane, Research Fellow, Centre for Service Excellence, University of Edinburgh Business School, Scotland.

Notes

1 A more nuanced version of this debate is about whether PAM should be led by practitioners or by ‘the public’ (Azfar Nisar, Citation2020; Reed 98 2021).

References

- Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure. Journal of Management, 43(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316678451

- Alderson, P. (1998). The importance of theories in healthcare. BMJ, 317(7164), 1007–1010. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7164.1007

- Ansell, C., Sorensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic as a game changer for public administration and leadership? The need for robust governance responses to turbulent problems. Public Management Review, 23(7), 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272

- Barzelay, M., & Thompson, F. (2010). Back to the future: Making public administration a design science. Public Administration Review, 70, S295–S297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02290.x

- Borkowski, N., Williams, E., O’Connor, S., & Qu, H. (2018). Outlets for health care management research: An updated assessment of journal ratings. Journal of Health Administration Education, 35(1), 47–63.

- Bushouse, B., & Sowa, J. (2012). Producing knowledge for practice. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(3), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011422116

- Chaiklin, S., & Lave, J. (Eds.) (1993). Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chijioke, J., Ikechukwu, A., & Aloysius, A. (2021). Understanding theory in social science research: Public administration in perspective. Teaching Public Administration, 39(2), 156–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739420963153

- Committee on Standards in Public Life. (2021). Upholding standards in public life. London: CSPL.

- Cook-Sather, A. (2015). Dialogue across differences of position, perspective, and identity: Reflective practice in/on a student-faculty pedagogical partnership program. Teachers College Record, 117(2), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811511700204

- Cui, T., & Osborne, S. (2022). Unpacking value destruction in the intersection between public and private value. Public Administration, 2022, 12850. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12850

- Dubnick, M. (2018). Demons, spirits and elephants: Reflection on the failure of public administration theory. Journal of Public and Nonprofit Affairs, 4(1), 59–115. https://doi.org/10.20899/jpna.4.1.59-115

- Elias, M. (2020). Phenomenology in public administration: Bridging the theory–practice gap. Administration and Society, 52(10), 1516–1537.

- Elliot, I., Robson, I., & Dudau, A. (2021). Building student engagement through co-production and curriculum co-design in public administration programmes’. Teaching Public Administration, 39(3), 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739420968862

- Epstein, R., & Hundert, E. (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA, 287(2), 226. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.2.226

- European Commission. (2016). Background note on open access to scientific publications and open research data (Directorate-General for Research and Innovation of the European Commission, Brussels).

- Ferlie, E. (2017). Exploring 30 years of UK public services management reform – The case of health care. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 30(6–7), 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-06-2017-0178

- Fuglsang, L. (2021). Towards a practice-based approach to public innovation – Apollonian and Dionysian practice-approaches. Nordic Journal of Social Research, 2021, njsr.3685. https://doi.org/10.7577/njsr.3685

- Gauch, H. (2003). Scientific method in practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Geiger, D. (2009). The practice-turn in organization studies: Some conceptual and methodological clarifications. In A. G. Scherer, I. M. Kaufmann, M. Patzer (Eds.), Methoden in der Betriebswirtschaftslehre. Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-9473-8_11

- George, B., Walker, R., & Monster, J. (2019). Does strategic planning improve organizational performance? A meta-analysis. Public Administration Review, 79(6), 810–819. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13104

- Gherardi, S. (2000). Practice-based theorizing on learning and knowing in organizations. Organization, 7(2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050840072001

- Gheradi, S. (2019). How to conduct a practice-based study. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Giddens, M. (1984). The constitution of society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Glennon, R., Hodgkinson, I., & Knowles, J. (2019). Learning to manage public service organisations better: A scenario for teaching public administration. Teaching Public Administration, 37(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739418798148

- Granstrand, O., & Holgersson, M. (2020). Innovation ecosystems. Technovation, 2020, 102098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102098)

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., Asmus, J., Olsen, L., & Tummers, L. (2017). Behavioural public administration. Public Administration Review, 2017, 12609. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12609

- Guthrie, J., Parker, L., Dumay, J., & Milne, M. (2019). What counts for quality in interdisciplinary accounting research in the next decade: A critical review and reflection. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(1), 2–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2019-036

- Guy, M., & Mastracci, S. (2018). Making the affective turn: The importance of feelings in theory, praxis, and citizenship. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 40(4), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2018.1485455

- Harmon, M. (1989). The Simon/Waldo debate. Public Administration Quarterly, 12, 4), 437–451.

- Hay, C. (2011). Interpreting interpretivism, interpreting interpretations: The new hermeneutics of public administration. Public Administration, 89(1), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01907.x

- Head, B. (2010). Public management research: Towards relevance. Public Management Review, 12(5), 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719031003633987

- Hubbard, B. (1995). A theory for practice: Architecture in three discourses. Cambridge, Mass.: NMIT Press.

- Huxham, C., & Hibbert, P. (2011). Use matters … and matters of use’. Building theory for reflective practice. Public Management Review, 13(2), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.532964

- Jones, M., Manville, C., & Chataway, J. (2017). Learning from the UK’s research impact exercise. Journal of Technology Transfer, 47, 722–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9608-6

- Jun, J. (1994). On administrative praxis. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 16(2), 201–207.

- Kernaghan, K. (2009). Speaking truth to academics: The wisdom of the practitioners. Canadian Public Administration, 52(4), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-7121.2009.00099.x

- Kinder, T., Six, F., Stenvall, J., & Memon, A. (2022). Governance-as-legitimacy: Are ecosystems replacing networks? Public Management Review, 24(1), 8–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1786149

- Kinder, T., Stenvall, J., Six, F., & Memon, A. (2021). Relational leadership in collaborative governance ecosystems. Public Management Review, 23(11), 1612–1639. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1879913

- Knapp, M. (1984). Economics of social care. London: Macmillan.

- Leite, H., & Hodgkinson, I. (2021). Examining resilience across a service ecosystem under crisis’ Public. Management Review, 2021, 2012375. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.2012375

- Lowe, T., French, M., Hawkins, M., Hesselgreaves, H., & Wilson, R. (2021). Responding to complexity in public services – The human learning systems approach. Public Money & Management, 41(7), 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1832738

- Marini, F. (1993). Leaders in the field: Dwight Waldo. Public Administration Review, 53(5), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.2307/976341

- McDonald, B. III (2018). Exorcising our demons. Journal of Public and Non-Profit Affairs, 4(1), 116–120.

- Mastracci, S., Newman, M., & Guy, M. (2010). Emotional labor: Why and how to teach it. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 16(2), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2010.12001590

- Meier, K. (2015). Proverbs and the evolution of public administration. Public Administration Review, 75(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12288

- Miller, H., & Fox, C. (2007). Postmodern public administration. New York: Routledge.

- Mitchell, D. (2018). Strategic implementation: An illustration of theory/practice disconnect in public administration. Public Administration Quarterly, 42(1), 59–89.

- Nabatchi, T., & Carboni, J. (2019). Assessing the past and future of public administration: Reflections from the Minnowbrook at 50 Conference. IBM Center for The Business of Government, Washington DC.

- Neumann, F. Jr. (1996). What makes public administration a science? Or, are its "big questions" really big? Public Administration Review, 56(5), 409–415. (https://doi.org/10.2307/977039

- Nisar, A. (2020). Practitioner as the imaginary father of public administration: A psychoanalytic critique. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 42(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1589230

- Nutley, S., Walter, I., & Davies, H. (2007). Using evidence: How research can inform public services. Bristol: Policy Press.

- O’Flynn, J. (2021). Confronting the big challenges of our time: Making a difference during and after COVID-19. Public Management Review, 23(7), 961–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1820273

- O’Leary, R., Van Slyke, D., & Kim, S. (2011). The future of public administration around the world. Washington DC: Georgetown UP.

- Osborne, S. (2021). Public service logic. London: Routledge.

- Osborne, S., Nasi, G., & Powell, M. (2021). Beyond co-production: Value creation and public services. Public Administration, 99(4), 641–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12718

- Osborne, S., Powell, M., Cui, T., & Strokosch, K. (2022). Value creation in the public service ecosystem: An integrative framework. Public Administration Review, 82(4), 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13474

- Ospina, S., & Dodge, J. (2005). Narrative inquiry and the search for connectedness: Practitioners and academics developing public administration scholarship. Public Administration Review, 65(4), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00468.x

- Pereira, J., & Viola, E. (2021). Climate change and biodiversity governance in the Amazon. New York: Routledge.

- Petrescu, M. (2019). From marketing to public value: Towards a theory of public service ecosystems. Public Management Review, 21(11), 1733–1752. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1619811

- Pettigrew, A. (2005). The character and significance of management research on the public services. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 973–977. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.19573101

- Pollitt, C. (2013). Context in public policy and management. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Potter, M., Quill, B., Aglipay, G., Anderson, E., Rowitz, L., Smith, L., … Whittake, C. (2006). Demonstrating excellence in practice-based research for public health. Public Health Reports, 121(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490612100102

- Raadschelders, J. (2019). The state of theory in the study of public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 41(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2018.1526517

- Raelin, J. (2007). Toward an epistemology of practice. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 6(4), 495–519. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2007.27694950

- Ryan, P. (2015). Positivism: Paradigm or culture? Policy Studies, 36(4), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2015.1073246

- Reed, D. (2021). ’Don’t exclude real practitioners with the imaginary ones: A comment on Azfar Nisar’s “Practitioner as the imaginary father of public administration. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 44(1), 84–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2021.1910412

- Rogers, W., & Hutchison, K. (2017). Evidence-based medicine in theory and practice: Epistemological and normative issues. In T. Schramme, & S. Edwards (Eds.), Handbook of the philosophy of medicine (pp. 851–872). Dordrecht: Springer Nature.

- Rossi, P., & Tuurnas, J. (2021). Conflicts fostering understanding of value co-creation and service systems transformation in complex public service systems. Public Management Review, 23(2), 254–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1679231

- Sanders, J., & McPeck, J. (1976). Theory into practice or vice versa? Comments on an educational antinomy’. Journal of Educational Thought, 10(3), 188–193.

- Sarker, N., Chanthamith, B., Anusara, J., Huda, N., Amin, A., Jischen, L., & Nasrin, M. (2018). Determination of interdisciplinary relationship among political science, social sciences and public administration: Perspective of theory and practice. Discovery, 54, 273.

- Schon, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books.

- Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. London: Routledge.

- Shand, R., Parker, S., Liddle, J., Spolander, G., Warwick, L., & Ainsworth, S. (2022). After the applause: Understanding public management and public service ethos in the fight against Covid. Public Management Review, 2022, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2026690

- Simon, H. (1947). Administrative behavior. New York: Macmillan.

- Smith, H. & Dean, R. (eds). (2009). Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Spicer, M. (2005). Public administration enquiry and social science in the postmodern condition: Some implications of value pluralism. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 27(4), 669–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2005.11029517

- Starke, A. Jr. (2018). Pariahs no more? On the status of theory and theorists in contemporary public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 40(2), 143–149. (https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2018.1458206

- Strokosch, K., & Osborne, S. (2020). Co-experience, co-production and co-governance: An ecosystem approach to the analysis of value creation. Policy & Politics, 48(3), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557320X15857337955214

- Suoranta, J., Aura, S., & Katainen, J. (2002). Theory, research and practice: Towards reflective relationship between theory and practice in architectural thinking. International Journal of Architectural Research, 15(1), 73–81.

- Svara, J. (2014). Who are the keepers of the code? Articulating and upholding ethical standards in the field of public administration. Public Administration Review, 74(5), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12230

- Tansley, A. (1935). The use and abuse of vegetational terms and concepts. Ecology, 16(3), 284–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/1930070

- Taylor, R., Torugsa, N., & Arundel, A. (2018). Leaping into real-world relevance: An ‘abduction’ process for non-profit research. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(1), 206–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764017718635

- Tilley, H., Ball, L., & Cassidy, C. (2018). Research Excellence Framework (REF) impact Toolkit. London: ODI.

- Tomazevic, N., Tekavcic, M., & Peljhan, D. (2017). Towards excellence in public administration: Organisation theory-based performance management model. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 28(5–6), 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1102048

- Van Dooren, W., Bouckaert, G., & Halligan, J. (2015). Performance management in the public sector. London: Routledge.

- Van de Ven, A., & Johnson, P. (2006). Knowledge for theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 802–821. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.22527385

- Van der Waldt, G. (2016). A unified public administration? Journal of Social Sciences, 48(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2016.11893584

- Van der Waldt, G. (2017). Theory for research in public administration. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(9), 183–202.

- Vargo, S., Akaka, M., & Vaughan, M. (2017). Conceptualizing value: A service-ecosystem view. Journal of Creating Value, 3(2), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/2394964317732861

- Vasudeva, G., Leiponen, A., & Jones, S. (2020). Dear enemy: The dynamics of conflict and cooperation in open innovation ecosystems. Strategic Management Review, 1(2), 355–379. https://doi.org/10.1561/111.00000008

- Waldo, D. (1948). The study of public administration. New York: Ronald Press.

- Walker, R. M., Chandra, Y., Zhang, J., & Witteloostuijn, A. (2019). Topic modelling the research-practice gap in public administration. Public Administration Review, 79(6), 931–937. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13095

- Wang, J., Bunch, B., & Stream, S. (2013). Increasing the usefulness of academic scholarship for local government practitioners. State and Local Government Review, 45(3), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X13500771

- Whetsell, T., & Shields, P. (2015). The dynamics of positivism in the study of public administration: A brief intellectual history and reappraisal. Administration & Society, 47(4), 416–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399713490157

- Whittemore, A. (2015). Practitioners theorize, too: Reaffirming planning theory in a survey of practitioners’ theories. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X14563144

- Wright, B. (2015). The science of public administration: Problems, presumptions, progress and possibilities. Public Administration Review, 75(6), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12468

- Zanetti, L. (1997). Advancing praxis: Connecting critical theory with practice in public administration. The American Review of Public Administration, 27(2), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/027507409702700203