Abstract

Occupational research often emphasizes the importance of workplace characteristics for understanding job stress and employee well-being, but the role of personal characteristics and having a good match with the job is mostly neglected. We explored how job crafting and feelings of being authentic at work were related to work engagement, work engagement of performance, and procrastination. A structural equation model analyzed self-reports from 380 Dutch office employees. Job crafting and authenticity were positively related to work engagement, and high work engagement predicted? better in-role and extra-role performance and less work procrastination. Moreover, performance and procrastination were negatively related. Results emphasize the importance of having a “good fit” between the employment settings and employees to promote engagement. By improving employee’s work engagement, organizations might improve the likelihood that personnel respond favorably with organizational goals and reduce the chances of engaging in workplace procrastination.

The role of having “good fit”

Research on procrastination has become more popular during the last three decades (Ferrari, Citation2010). Steel (Citation2007, p. 66) and others (Ferrari, Johnson, & McCown, Citation1995) described procrastination as a “voluntarily delay [of] an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay”. Procrastination has been studied with respect to behaviors in various life domains, such as activities in the academic, every day routine, or health areas (Ferrari, Citation2010; Klingsieck, Citation2013). However, workplace procrastination has received considerably less attention (DeArmond, Matthews, & Bunk, 2013). Despite the scarce available research in work contexts, chronic procrastination is mainly associated with negative outcomes such as receiving a lower salary, experiencing shorter spells of employment, having a tendency to be underemployed (Nguyen, Steel, & Ferrari, Citation2013), having lower self-efficacy (Steel, Citation2007), and reporting higher levels of boredom (Wan, Downey, & Stough, Citation2014).

To date, little is known about the possible relationships between procrastination and positive aspects of employee functioning, such as motivation and performance. In the present study, we focus on examining the relationship between procrastination and positive aspects of employee functioning, namely work engagement and job performance. In addition, we explored the role of the level of fit between a worker, his/her work environment (cf. Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, Citation2005), and workplace procrastination. We consider job crafting and workplace authenticity as possible indicators of a good fit between the characteristics, preferences, goals, and expectations of employees and their organizations. Finally, we propose and test a heuristic mediation model for the links among these concepts. By doing so, this study contributes to the understanding of the correlates of procrastination in the workplace.

Procrastination, performance and work engagement

Work performance refers to employee behaviors consistent with the goals of the organization (Viswesvaran & Ones, Citation2000), and, in turn, is among the core work outcomes in occupational research. Risk exists that employees may sometimes engage in non-work related activities during work hours, such as procrastinating work tasks (e.g., excessive breaks, browsing on social media, or online shopping). We proposed that the extent to which employees engage in task-unrelated activities at work, is a function of their cognitive-motivational involvement with their jobs. In this section, we focused on the potential relationship between work engagement on the one hand and performance and procrastination on the other hand.

Work engagement and performance

Work engagement (i.e., a positive, energetic, and fulfilling state of mind at work) is one of the most-studied well-being conditions within the positive psychology approach of the last two decades (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, Citation2008). Work engagement may be characterized by vigor (the energy and the mental resilience at work), dedication (the strong involvement in one’s work and the experience of significance, enthusiasm, pride, and challenge at work), and absorption (being happily engrossed and fully concentrated in work). Work engagement is an important predictor of several positive individual (e.g., better health) and organizational (e.g., job satisfaction) outcomes. For example, engaged employees experience more flow, confidence, and optimism (Cropanzano & Wright, Citation2001) and report fewer health problems (Schaufeli, Taris, & van Rhenen, Citation2008) than others. Such positive, work-related emotions as well as physical conditions also appear to increase energy and affect employee functioning positively. Longitudinal studies show that work engagement is likely to improve both task performance (e.g., submitting finance reports timely to the finance department, Bakker & Bal, Citation2010; Bakker, Demerouti, & ten Brummelhuis, Citation2012) and contextual performance (such as helping new colleagues with job-related problems, Bakker, Demerouti, & Verbeke, Citation2004). In this paper, we examine the task as well as the contextual dimensions of performance. Hypothesis 1 is therefore that work engagement positively related to both indicators of job performance.

Work engagement and procrastination

Procrastination at work is a type of self-regulatory failure to execute an intended work task (Nguyen et al., Citation2013). In the present study, we conceptualized procrastination at work as an adverse and non-productive type of work activity. Consistent with this notion, previous studies showed that procrastination at work was associated with fatigue, psychological detachment (DeArmond et al., Citation2014), job-related stress (Wan et al., Citation2014), and low income (Nguyen et al., Citation2013). However, a shortcoming of these earlier studies was that they used general and academic procrastination scales for measuring procrastination at work. Consequently, typical procrastination activities that can be applied in work settings, such as taking long pauses or playing computer games during work hours, cannot be measured with these instruments. Recently, Metin, Taris, and Peeters (Citation2016) addressed this gap and developed the Procrastination at Work Scale (PAWS) to measure and explore specific employee idle behaviors. In their conceptualization, procrastination at work refers to putting off work-related action by engaging (behaviorally or cognitively) in nonwork-related actions, with no intention of harming the employer, employee, workplace, or client. They distinguished between soldiering and cyberslacking. The former may be defined as avoiding work (such as taking longer coffee breaks or daydreaming) without aiming to harm others or shift work onto colleagues, whereas the latter can be defined as the utilization of mobile technology and internet for personal purposes during work hours (Garrett & Danziger, Citation2008). Metin et al. (Citation2016) deliberately excluded usage of internet and mobile technology from the manifestation of soldiering as it corresponds to the cyberslacking dimension of procrastination. Cyberslacking is a contemporary and a very prevalent type of workplace behavior; apparently, employees spend no less than 30% of their of day with non-work related online activity and almost 80% of the employees report that they use internet for their personal interest while at work, such as checking social network sites, reading blogs, doing online shopping (Eddy, D’Abate, & Thurston, Citation2010; Lavoie & Pychyl, Citation2001).

Scantiness of positive emotions at work could steer employees to seek for shorter or longer spells of non-work related but potentially pleasurable activities during work hours, and such employees might show lower levels of productivity than others. For instance, procrastination at work was found to be related to job boredom (Metin et al., Citation2016) which is a state of understimulation at work (Reijseger et al., Citation2013). Employees who do not experience high levels of cognitive-physical stimulation might experience less cognitive energy and feel less committed to their work; therefore, they might be open for or even be actively looking for pleasurable distractions from work, such as engaging in instant messaging or taking overly long breaks. In contrast, engaged workers are expected to have high resilience, to be active, and to experience pleasure while working, which could diminish their need to engage in off-task activities. This leads to the expectation that work engagement is negatively related to procrastination at work (Hypothesis 2).

Procrastination and performance

Although the workplace procrastination literature presents little evidence for a possible relationship between procrastination and work performance, research on academic procrastination revealed that procrastination is strongly and negatively related to conscientiousness. In turn, conscientiousness is positively linked to academic performance. Moreover, procrastination was mostly associated with lower academic performance (such as grade average) and higher stress (Steel, Citation2007; van Eerde, Citation2003). We expect a similar pattern within the work context. Employees displaying high levels of procrastination spend a significant amount of their work hours on non-work related activity. Therefore, in order to finish their daily tasks, they might work for longer hours (resulting in lower levels of concentration and more exhaustion) or might rush their tasks (possibly resulting in mistakes). As a result, by engaging in procrastination behaviors, employees could display poorer job performance. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is that procrastination at work and job performance are negatively related.

Authenticity and job crafting as indicators of fit

According to Person-Environment Fit theory, good fit is obtained if the characteristics of a work environment match well with employees’ needs and abilities (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005). In the literature, different types of person-environment fit at work are distinguished, including needs–supplies fit (the capability of environmental supplies to meet individual needs), demands–abilities fit (the degree to which individual knowledge, skills, and abilities meet the demands of the job), and value congruence (the similarity between individual values and the values of others in the organization or the social environment). Although conceptually different, all types of fit assume that high levels of fit are associated with positive work outcomes. Clearly, it is important for both the employee and the organization that the employee fits well in the organizational/job context, i.e., that good fit is achieved.

In the present study, we focus on two concepts that can be considered as indicators of good fit, namely authenticity and job crafting. Authenticity at work refers to being able to experience one’s true self at work (Van den Bosch & Taris, Citation2014b). It is the degree to which a person is able to act in accordance to one’s true self (Harter, Citation2002). Although authenticity is both conceptually and empirically different from person-environment fit (Van den Bosch, Schaufeli, Taris, Peeters & Reijseger, Citation2016), both concepts also overlap to a substantial degree, since employees who experience good fit with their respective environments in terms of their values, needs and abilities are likely to indicate that they can act in accordance with their own values, needs and abilities – i.e., their true selves. In this sense, high levels of authenticity signify good fit of the individual worker in their work environment. Job crafting refers to “the physical and cognitive changes individuals make in the task or relational boundaries of their work” (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001, p. 179). Physical changes refer to changes regarding the form, scope, or the number of job tasks; whereas, cognitive changes refer to changes about how one experiences the job (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2014). Workers can craft their jobs for a multitude of reasons, and among these is the wish to achieve better fit between the requirements of their job and their values, needs and abilities. Thus, it can be assumed that high levels of job crafting are associated with good fit.

Authenticity

In their person-centered concept, Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis, and Joseph (Citation2008) defined authenticity as a three-dimensional concept. The first dimension is self-alienation, referring to the (mis)match between an individual’s actual physiological states and this individual’s conscious awareness of this state. A perfect match is almost never possible; hence, the discrepancy between these two domains might lead to a more inauthentic state, thus leading to misfit. The second dimension is authentic living, which stands for the expression of emotions in such a way that it is consistent with the conscious awareness of an individual’s physiological states, emotions, beliefs, and cognitions. It is the degree to which people are true to their own selves and live in accordance with their values and beliefs. The last dimension is external (or social) influence, referring to the acceptance of others’ expectations. External influence can affect both self-alienation and authentic living processes, thus completing the tripartite nature of authenticity (van den Bosch & Taris, Citation2014a).

Although authenticity has been studied in different domains, authenticity at work only gained interest very recently. Van den Bosch and Taris (Citation2014b) adapted the general authenticity scale of Wood et al. (Citation2008) to the workplace context, and reported positive relationships between workplace authenticity, job satisfaction, in-role performance, and work engagement. Similarly, Metin, Taris, Peeters, Van Beek, and Van den Bosch (Citation2016) found that authenticity at work mediated the association between job resources on the one hand and job satisfaction, work engagement and subjective job performance on the other. Ménard and Brunet (Citation2011) also found a positive association between managers’ cognitive and behavioral authenticity and their subjective well-being. In short, individuals who experience a good fit between their job/work environment and their true selves tend to be more engaged a work and perform better than others. Thus, Hypothesis 4a is that authenticity at work positively related to performance, but this relationship is (at least partly) mediated by work engagement. Further, Hypothesis 4b states that authenticity at work is negatively related to procrastination, but this relationship is (at least partly) mediated by work engagement.

Job crafting

If workers are indeed capable of making changes in their tasks or the social conditions under which they work (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001), it is plausible that active job crafters are more likely to achieve good fit with their job (and experience the positive outcomes thereof) than others. For example, Bakker (Citation2011) argued that employees may be able to improve their person-job fit as a consequence of job crafting.

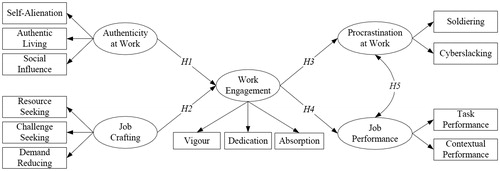

Job crafting can facilitate fit in three different ways. First, individuals aim to avoid uncertainty regarding their jobs by aiming to take more control over what they do. Second, job crafting motivates individuals to change certain aspects of the tasks in order to experience a more positive sense of self, which is expressed and confirmed by coworkers. Third, job crafting satisfies employees’ need for being affiliated with others (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001). Job crafting is found to contribute to the creation of more healthy and motivating work conditions that correspond with individual needs. Earlier longitudinal and diary research has largely confirmed these ideas. For example, a five-day diary survey showed that day-level challenge-seeking was positively and day-level demands-reduction was negatively related to day-level work engagement, illustrating the potential motivational role of job crafting (Tims, Bakker, & Derks, Citation2012). Similarly, Tims, Bakker, and Derks (Citation2015) found that job crafting intention was related to increasing job resources and challenges and eventually higher levels of work engagement in time. Moreover, Petrou, Demerouti, Peeters, Schaufeli, and Hetland (Citation2012) found that day-level fluctuations in job crafting corresponded with day-level fluctuations in work engagement. Last, in their longitudinal study, Lu et al. (Citation2014) found that work engagement was positively related to changes in person-job fit via changes in physical and relational job crafting. In short, job crafters seem to be aware of their personal needs and change their work conditions according to these needs, eventually leading to higher levels of work engagement and performance. Consequently, we expect a positive relationship between job crafting and work engagement. Hypothesis 5a is that job crafting positively related to performance, but this relationship is (at least partly) mediated by work engagement. Hypothesis 5b states that job crafting is negatively related to procrastination, but this relationship is (at least partly) mediated by work engagement. A summary of the relationships expected in this study as well as the heuristic model to be tested is illustrated in .

Method

Sample and procedure

Sample consisted of white-collar full-time employees who worked in the Netherlands in various (i.e., 20% government, 15% education, and 12.5% insurance). An online questionnaire was distributed using the authors’ personal networks and social network websites, such as LinkedIn. Individuals received a message that obtained a short description of the study and a link to the web-based survey. A total of 380 individuals completed the survey, yielding equal numbers of males and females (50.0% each) with an average age of 42.1 years (SD = 12.4) and 72% of the participants earned a college or university degree. On an average, respondents reported they worked 33.9 hours (SD = 7.1) per week, with an average of 4 hours of overwork per week. Respondents had a career length of 20.1 years (SD = 12.3), worked in their current organization for on average 11.6 (SD = 10.9) years.

Measures

Job crafting was assessed by the 13-item job crafting questionnaire of Petrou et al. (Citation2012). Responses ranged along a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = often). The dimension of seeking resources was measured by six items (e.g., ‘I ask my colleagues for advice’). The dimension of seeking challenges was measured by three items (e.g., ‘I ask for more challenging tasks’). Finally, the dimension of reducing demands was measured by four items (e.g., ‘I make sure I do less physical tasks’).

Work authenticity was assessed by the 12-item Individual Authenticity Measure at Work (IAM Work: Van den Bosch & Taris, Citation2014b), consisting of three dimensions: self-alienation (including “At work, I feel alienated from myself”), authentic living (e.g., “At work, I am true to myself”), and social influence (for example, “At work, I usually do what others tell me”). Each dimension was measured with 4 items (1= strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Work engagement was measured with the nine-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2003). Its three sub dimensions (vigour, e.g., ‘At my work, I feel bursting with energy’; dedication, e.g., ‘I am enthusiastic about my job’; and absorption, e.g., ‘I get carried away when I am working’) were measured by three items each that were answered on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = never, 6 = always).

Procrastination at work was measured by the Procrastination at Work Scale (PAWS; Metin, Taris, & Peeters, Citation2016). The PAWS is a 12-item two-dimensional scale that focuses on contemporary workplace procrastination behaviors. It is scored on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = never, 6 = always). Eight items measure soldiering (i.e., “When I have excessive amount of work to do, I avoid planning my tasks, and find myself doing something totally irrelevant”) and 4 items measure cyberslacking (such as “I do online shopping during working hours”).

Job performance was assessed with the Individual Work Performance Questionnaire (IWPQ; Koopmans et al., Citation2012). Only the positive dimensions of the IWPQ were used in this study, namely task performance and contextual performance. The items of the IWPQ refer to the 3 months before the questionnaire was completed. Items are rated on 5-point Likert scales (1 = seldom; 5 = always). Five items assess task performance (such as “I managed to plan my work so that it was done on time”) and 8 items assess contextual performance (i.e., “I took on extra responsibilities”).

Statistical analysis

The model proposed in was tested using structural equation modeling. The model fit was examined through the chi-square test, the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Normed Fit Index (NFI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). RMSEA values smaller than 0.08, as well as GFI, NFI, and CFI values higher than 0.90 indicate acceptable model fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). For the mediation analyses Shrout and Bolger’s (Citation2002) bootstrapping method was used. Bootstrap samples (2000 resamples) were generated from the original sample using random sampling with replacement and maximum likelihood method. Mediation takes place if the 95% CI for the estimates of the indirect effect excludes zero.

Results

Descriptive statistics reporting the means, standard deviations, bivariate correlations between the study variables, and internal consistencies of the scales are shown in . As this table shows, all dimensions of work engagement were related to soldiering (rs ranging from −.13 to −.27, p < .05) but only vigor was related to cyberslacking (r = −.14, p < .01). Likewise, all dimensions of authenticity were negatively related to soldiering (rs ranging from −.11 to −.27; p < .05). Both the authentic living and self-alienation dimensions of authenticity showed positive correlations with task (rs were .17 and .25, ps < .01) and contextual (rs were .25 and .23; ps < .01) performance, respectively.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations for the model variables (internal consistency scores of the related scales are reported on the diagonal).

Model Testing

The results revealed a poor fit for M1, χ2 (df = 60) = 589.06, GFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.83, CFI = 0.86, RMSEA = 0.09. The modification indices suggested the addition of direct paths from job crafting to job performance and procrastination, as well as a direct path from authenticity to procrastination at work. Moreover, the residuals of the two dimensions of job crafting, namely demand reducing and resource seeking, were correlated. The new model (M2) had a significantly better fit, χ2 (df = 56) = 166.52, GFI = 0.94, NFI = 0.89, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.07, Δχ2 M1−M2 (df = 6) = 92.54, p < .01. Hence, M2 was accepted as the final model.

Hypothesis Testing

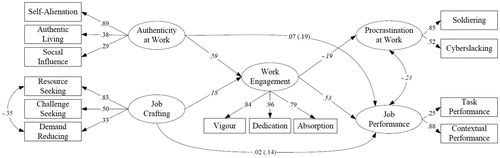

presents the final model (M2) and its standardized regression coefficients. Hypotheses 1 stated a positive relationship from work engagement to performance whereas Hypothesis 2 stated a negative relationship from work engagement to procrastination. Both Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported as work engagement was positively linked to performance (β = 0.53, p < .01) and negatively to procrastination (β = −0.19, p< .05). Moreover, performance and procrastination were negatively related (r = −.23, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 3. For Hypotheses 4a–b and 5a–b, a series of bootstrapping analysis was conducted. As can be seen in , work engagement mediated the indirect paths from authenticity to performance (β = 0.19, p < .01, 95% lower CI = 0.12, higher CI = 0.27, Hypothesis 4a confirmed) and from job crafting to performance (β = 0.14, p < .01, 95% [CI: 0.07, 0.22]), supporting Hypothesis 5a. No mediation was found for the indirect path from job crafting and authenticity to procrastination via work engagement (Hypotheses 4b and 5b rejected).

Figure 2. Final model M2 of the relationships between authenticity at work, job crafting, work engagement, job performance, and procrastination at work. Coefficients represent standardized estimates. Direct effects from authenticity and job crafting are presented within the parenthesis. Coefficients over 0.11 indicate significance at *p < .01 level.

Table 2. Indirect pathways after executing bootstrapping (N = 380).

Discussion

The present study had three main goals. Firstly, we aimed at improving the understanding of procrastination at work by focusing on its relationship with important positive occupational constructs, such as work engagement and performance. Secondly, we examined the role of having good person-job fit by focusing on two indicators of fit (job crafting and authenticity). Lastly, we explored whether work engagement mediates the link between having a good match with one’s work on the one hand and performance and procrastination on the other hand. By doing so, our purpose was to get a better understanding of the correlates of procrastination at work and the specific role of having a good fit in this respect.

As expected, there was a negative relationship between engagement and procrastination. Apparently, individuals who have high levels of energy, mental resilience, enthusiasm, inspiration, and concentration (i.e., engaged workers, Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2003), do not spend much time on non-work related activities during work hours. Also as expected, procrastination and performance were negatively related. Hence, it is plausible that spending excessive time on personal activities while actually at work (such as reading blogs, engaging in gossiping, and instant messaging, etc.) could affect performance negatively, either by decreasing the quality or the amount of the work done.

Our findings also provide insight in certain strategies that might increase productivity and worker functioning. Results demonstrated that both job crafting behavior and feeling authentic at work (as two possible indicators of having a good person-job fit) (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005) may have a positive effect on in-role and extra-role performance via the promotion of work engagement. Although no such effect of having good fit was found for procrastination, our results still provide empirically significant evidence for the negative relationship of idle behavior with work engagement and performance. These are notable findings for understanding the nature of this relatively novel concept and its relationship with some of the most profound positive workplace constructs.

Our results further demonstrate that employees report higher levels of work engagement when they are able to experience their authentic being at work and can redesign their tasks according to their preferences. Building on earlier studies (Metin et al., Citation2016; Petrou et al., Citation2012; Tims et al., Citation2015), these findings suggest that individuals who are seeking to control their environment and structure their work with the aim of achieving a better match with their jobs, are likely to experience improved well-being. Possibly, individuals who experience good fit also experience higher levels of energy at work because they find their jobs more meaningful, which eventually improves their engagement. Hence, an organization that values and promotes job crafting and authenticity at work is likely to be able to achieve higher levels of work engagement among its employees, in turn leading to the positive outcomes associated with engagement (Petrou, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, Citation2015).

Unexpectedly, we did not find indirect links between the two person-job fit indicators and procrastination. One explanation for the absence of these relationships could be that procrastination is perhaps better explained through personality factors such as discipline and carelessness (Schouwenburg & Lay, Citation1995) or self-handicapping processes (Jones & Berglas, Citation1978) than by the interaction between a person and his/her environment. In an earlier study, procrastination was found to be linked to boredom at work; however, procrastination was not directly related to workplace characteristics such as autonomy or mental demands (Metin et al., Citation2016). Moreover, in her meta-analytic study, van Eerde (Citation2003) found strong links between personality (especially conscientiousness), self-imaging (self-efficacy and self-esteem), self-handicapping and procrastination, which suggests that procrastination is a type of behavior that is not directly affected by the environment, but rather stems from either personality factors or from states that are evoked by the environment (such as work engagement or boredom). However, note that both job crafting and authenticity were indirectly related to performance via work engagement, and that both work engagement and performance were negatively related to procrastination. Hence, it can be argued that by achieving high levels of work engagement, it could be possible to limit procrastination behaviors.

In summary, the present study focused on the factors that can boost work engagement and employee functioning. Our findings highlight the importance of two relatively novel concepts, authenticity, and job crafting, as indicators of person-job fit and demonstrate their benefits for sustaining work engagement. A further added value of this study is that it provides evidence for the relationships between positive work constructs, such as work engagement and performance, and procrastination. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the positive workplace correlates of procrastination in a structural equation model. Hence, we hope that our findings are helpful for improving our understanding of this slippery concept.

Limitations and suggestions for future studies

There are three major limitations to this study. First, the cross-sectional design of this study prevents us from making causal interpretations. Therefore, longitudinal data are needed to further validate these findings (Taris & Kompier, Citation2006). Nevertheless, our results for the nomological network of our study variables mesh well with earlier research. Thus, we encourage researchers to test the proposed relationships in a longitudinal design for causal implications.

Second, participants filled in an online self-report questionnaire, which may have resulted in inflated correlations among the concepts due to common method variance (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003). However, Spector (Citation2006) argues that self-report scales do not necessarily and automatically inflate associations among variables. In our study, we found a varied pattern of correlations without unexpectedly high associations among the study variables (the highest r was .54; cf. ), which supports Spector’s view and goes contrary to the assumption that common-method bias affected all of these correlations uniformly.

Finally, the data were collected from a convenience sample. Our sample consisted of highly educated white-collar employees, which are most likely not representative of the population, resulting in an underestimation of the true associations among the study concepts due to restriction-of-range effects. This implies that the estimates reported in the current study are conservative estimates of the population effects. Future studies among more representative samples may provide more insight in the true magnitude of the associations reported in this study.

Practical and scientific implications

Despite these limitations, this study has implications for both research and practice. From a scientific point of view, the present study adds to our insight in two concepts that have only recently been examined within the work context, namely authenticity and procrastination. The significant relationships of authenticity and workplace procrastination with some of the most widely studied concepts in occupational psychology underline the relevance of these concepts within the work context and this finding will hopefully encourage researchers to explore these constructs in more detail in the future.

From a practical point of view, our findings emphasize the positive outcomes of having a good match with one’s work. This confirms previous findings that showed that job crafting behaviors are beneficial for achieving organizational and personal goals (Tims et al., Citation2015); experiencing authenticity seems to have similar outcomes (Van den Bosch & Taris, Citation2014a, Citation2014b). Further, the strong positive link between engagement and performance (specifically to decrease procrastination behavior) speaks to the importance of promoting work engagement in organizations. Thus, organizations are encouraged to consider how they can maximize employees’ opportunities for job crafting and authenticity, as these facilitate employee fit and work engagement.

To this aim, supervisors may help individuals to experience their core selves and execute their tasks as they prefer in order to exhibit better functioning through work engagement. For example, managers can organize meetings to ask subordinates how satisfied they are with their task execution and if they would like to change certain characteristics according to their preferences. Receiving feedback from employees concerning their work environment and task execution can guide management towards ways to improve the positive aspects of work. By focusing on these antecedents, organizations are more likely to provide employees with the personal and job resources they need, which could result in higher levels of well-being (Petrou et al., Citation2012, Citation2015). Note that organizations are also likely to benefit from implementing such employee-centered interventions, like job crafting and authenticity, since this is expected to lead to higher task and contextual performance, as well as less non-work related activity during work hours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bakker, A. B. (2011). An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 265–269. doi:10.1177/0963721411414534

- Bakker, A. B., & Bal, M. P. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 189–206. doi:10.1348/096317909x402596

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & ten Brummelhuis, L. L. (2012). Work engagement, performance, and active learning: The role of conscientiousness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 555–564. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.08.008

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands − resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43, 83–104. doi:10.1002/hrm.20004

- Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work and Stress, 22, 187–200. doi:10.1080/02678370802393649

- Cropanzano, R., & Wright, T. A. (2001). When a “happy” worker is really a “productive” worker: A review and further refinement of the happy-productive worker thesis. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 53, 182. doi:10.1037//1061-4087.53.3.182-199

- DeArmond, S., Matthews, R. A., & Bunk, J. (2014). Workload and procrastination: The roles of psychological detachment and fatigue. International Journal of Stress Management, 21, 137–161. doi:10.1037/a0034893

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Job crafting. In M. C. W. Peeters, J. De Jonge, & T. W. Taris (Eds.), An introduction to contemporary work psychology (pp. 414–433). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Eddy, E. R., D'Abate, C. P., & Thurston, P. W. (2010). Explaining engagement in personal activities on company time. Personnel Review, 39, 639–654. doi:10.1108/00483481011064181

- Ferrari, J. R., (2010). Still procrastinating? The no regrets guide to getting it done. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ferrari, J. R., Johnson, J. L., & McCown, W. G. (1995). Procrastination and task avoidance: Theory, research, and treatment. New York: Springer Publications.

- Garrett, K. R., & Danziger, J. N. (2008). Disaffection or expected outcomes: Understanding personal internet use during work. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 937–958. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00425.x

- Harter, S. (2002). Authenticity. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 382–394). Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling, 6 (1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jones, E. E., & Berglas, S. (1978). Control of attributions about the self through self-handicapping strategies: The appeal of alcohol and the role of underachievement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4, 200–206. doi:10.1177/014616727800400205

- Klingsieck, K. B. (2013). Procrastination in different life-domains: Is procrastination domain specific? Current Psychology, 32, 175–185. doi:10.1007/s12144-013-9171-8

- Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C., Hildebrandt, V., van Buuren, S., van der Beek, A. J., & de Vet, H. C. (2012). Development of an individual work performance questionnaire. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 62, 6–28. doi:10.1037/e577572014-108

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals' fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person– group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

- Lavoie, J. A. A., & Pychyl, T. A. (2001). Cyberslacking and the procrastination superhighway: A web-based survey of online procrastination, attitudes, and emotion. Social Science Computer Review, 19, 431–444. doi:10.1177/089443930101900403

- Lu, C., Wang, H., Lu, J., Du, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Does work engagement increase person–job fit? The role of job crafting and job insecurity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84, 142–152. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2013.12.004

- Ménard, J., & Brunet, L. (2011). Authenticity and well-being in the workplace: A mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26, 331–346. doi:10.1108/02683941111124854

- Metin, U. B., Taris, T. W., & Peeters, M. C. W. (2016). Measuring procrastination at work and its associated workplace aspects. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 254–263. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.006

- Metin, U. B., Taris, T. W., Peeters, M. C. W., van Beek, I., & Van den Bosch, R. (2016). Authenticity at work – A job-demands resources perspective. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31, 483–499. doi:10.1108/jmp-03-2014-0087

- Nguyen, B., Steel, P., & Ferrari, J. R. (2013). Procrastination’s impact in the workplace and the workplace’s impact on procrastination. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 21, 388–399. doi:10.1111/ijsa.12048

- Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 1120–1141. doi:10.1002/job.1783

- Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Job crafting in changing organizations: antecedents and implications for exhaustion and performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20, 470–480. doi:10.1037/ocp0000032

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Reijseger, G., Schaufeli, W. B., Peeters, M. C. W., Taris, T. W., van Beek, I., & Ouweneel, E. (2013). Watching the paint dry at work: psychometric examination of the Dutch Boredom Scale. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 26, 508–525. doi:10.1080/10615806.2012.720676

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). Test manual for the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale [unpublished manuscript]. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Utrecht University.

- Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well‐being? Applied Psychology, 57, 173–203. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00285.x

- Schouwenburg, H. C., & Lay, C. H. (1995). Trait procrastination and the big-five factors of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 18, 481–490. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)00176-s

- Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 65–94. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

- Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9, 221–232. doi:10.1177/1094428105284955

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi:10.1037//1082-989x.7.4.422

- Taris, T. W., & Kompier, M. A. J. (2006). Games researchers play: Extreme-groups analysis and mediation analysis in longitudinal, occupational, and health research. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 32, 463–472. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1051

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 173–186. doi:10.1037/e572992012-317

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2015). Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24, 914–928. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2014.969245

- Van den Bosch, R., & Taris, T. W. (2014a). The authentic worker’s well-being and performance: the relationship between authenticity at work, well-being, and work outcomes. The Journal of Psychology, 148, 659–681. doi:10.1080/00223980.2013.820684

- Van den Bosch, R., & Taris, T. W. (2014b). Authenticity at work: Development and validation of an individual authenticity measure at work. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9413-3

- Van den Bosch, R. Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., Peeters, M. C. W., & Reijseger, G. (2016). Authenticity at work: A matter of fit? (Doctoral dissertation). Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands.

- van Eerde, W. (2003). A meta-analytically derived nomological network of procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 1401–1418. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00358-6

- Viswesvaran, C., & Ones, D. S. (2000). Perspectives on models of job performance. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 8, 216–226. doi:10.4135/9781412952651.n154

- Wan, H. C., Downey, L. A., & Stough, C. (2014). Understanding non-work presenteeism: Relationships between emotional intelligence, boredom, procrastination and job stress. Personality and Individual Differences, 65, 86–90. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.018

- Wood, A. M., Linley, A. P., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authenticity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 385–399. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.385

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26, 179–201. doi:10.2307/259118