ABSTRACT

Online learning has become the new normal in many medical and health science schools worldwide, courtesy of COVID-19. Satisfaction with online learning is a significant aspect of promoting successful educational processes. This study aimed to identify factors affecting student and faculty satisfaction with online learning during the new normal. Online questionnaires were emailed to students (n = 370) and faculty (n = 81) involved in online learning during the pandemic. The questionnaires included closed- and open-ended questions and were organised into two parts: socio-demographic information and satisfaction with online learning. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the responses to the satisfaction scales. Students’ and faculty responses to the open-ended questions were analysed using the thematic analysis method. The response rate was 97.8% for students and 86.4% for faculty. Overall satisfaction among students was 41.3% compared to 74.3% for faculty. The highest areas of satisfaction for students were communication and flexibility, whereas 92.9% of faculty were satisfied with students’ enthusiasm for online learning. Technical problems led to reduced student satisfaction, while faculty were hampered by the higher workload and the required time to prepare the teaching and assessment materials. Study-load and workload, enhancing engagement, and technical issues (SWEET) were the themes that emerged from the thematic analysis as affecting student and faculty satisfaction. Adopting a combination synchronous and asynchronous approach, incorporating different applications to engage students, and timely feedback are imperative to increasing student satisfaction, while institutional support and organisational policy could enhance faculty satisfaction.

Background

Due to safety measures as a result of COVID-19, online learning has become a useful and practical tool for curriculum delivery worldwide [Citation1,Citation2]. Several advantages of online learning for learners have been reported in the literature, including easy accessibility to knowledge, proper content delivery, content standardisation, personalised instruction, self-pacing, interactivity and increased convenience [Citation3]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, online learning has helped universities keep their doors open for students during lockdown to decrease the spread of the disease [Citation1,Citation2].

Although online learning is the only available solution during the COVID-19 pandemic, student and faculty satisfaction is crucial for a successful and effective learning process. Student and faculty satisfaction can be define as attitude resulting from an evaluation of educational experience, facilities and services [Citation4]. Faculty satisfaction is defined as the perception of the online teaching process as efficient, effective and beneficial for both students and faculty [Citation5]. On the other hand, student satisfaction is related to the value of the learning experiences [Citation6].

The definition of satisfaction in online learning is complex and multidimensional and includes many factors, such as communication, student participation in online discussions, flexibility, workload, technology support, instructor pedagogical skills, and feedback [Citation7,Citation8]. Satisfaction with online learning is based on three learning theories: social cognitive theory, interaction equivalency theorem, and social integration theory [Citation9–11]. Students construct knowledge in a social context while interacting with others, engaging in activities, and receiving feedback [Citation9]. Students’ interactions with other students, instructors and content play a significant role in satisfaction. Therefore, satisfaction with the learning experience increases as multiple types of interactivity are used within the learning context [Citation10]. Engaging students in formal extracurricular activities in addition to their academic programme improves student satisfaction. Informal faculty–peer social interaction is also valued in the learning process [Citation11].

There is a growing body of literature showing that satisfaction has a positive relationship with student engagement and academic performance [Citation12,Citation13]. The quality of learning is based on faculty and student satisfaction along with learning effectiveness, access and institutional cost-effectiveness [Citation14,Citation15]. A previous study reported no significant differences between well-designed online and face-to-face learning [Citation16]; however, some studies have found that participants were more satisfied with face-to-face teaching [Citation17]. Other studies have reported that measuring student satisfaction in online learning is a significant aspect of successfully promoting educational processes for institutions, faculty and learners [Citation18,Citation19].

Factors affecting student and faculty satisfaction with online learning can be categorised into three main categories: faculty, interactivity, and technology [Citation15,Citation20] and students, instructor, and institution [Citation21], respectively. Student and faculty satisfaction are interrelated, as student satisfaction is affected by interaction and technology, which require more effort from faculty to engage the students online besides the necessity of adequate techno-pedagogical skills [Citation22]. Satisfaction across genders is a contradictory issue; while a study found that there are no differences between genders in online learning [Citation23], another study found that female students were more satisfied with online learning than male students [Citation24].

COVID-19 came abruptly with little or no preparation in place in many countries. The educational system during the COVID-19 era is characterised by a ‘new normal’. The term ‘new normal’ is described in the Urban Dictionary (2009) as a situation that occurs after an intense change. It was first used in the business field and other contexts to describe previously atypical life situations that have become typical [Citation25]. Online learning has been used as an adjunct method to augment the classical approach to teaching. The sudden transition from face-to-face teaching to 100% online learning is courtesy of COVID-19. Numerous studies have measured either student or faculty satisfaction with online learning before COVID-19 [Citation26–28]. To the best of our knowledge, no study has simultaneously measured both faculty and student satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study aimed to identify factors affecting student and faculty satisfaction with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at Medical and Health Sciences Colleges, University of Sharjah, between April and May 2020. The university had shifted suddenly during COVID-19 lockdown to deliver the curricula completely online using synchronous and asynchronous sessions utilising Blackboard and Microsoft Teams. Several training workshops and manuals were provided to both faculty and students. The university also established 24/7 technical support for both faculty and students.

An online questionnaire, along with the study information sheet and consent form, was sent to the expected participants in the Medical and Health Sciences Colleges. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

The sample size was 370 students and 81 faculty and was calculated using the formula of a finite population; the margin of error was set as 5%, and the confidence level was 95%. We used pre-validated questionnaires to measure student and faculty satisfaction with online learning [Citation20,Citation21].

The questionnaire was organised into two parts – socio-demographic information and satisfaction with online learning – using different satisfaction scales. The students’ satisfaction questionnaire was developed by Bolliger and Halupa in 2012 based on the Online Course Satisfaction Survey (OCSS) [Citation29]. It consisted of 24 items categorised into the following subscales: instructor, technology, course setup, interaction, outcomes and overall satisfaction. The questionnaire used a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The faculty satisfaction questionnaire, the Online Instructor Satisfaction Questionnaire (OISQ), was developed by Bolliger and Wasilik in 2009 [Citation5]. It consisted of 28 items, categorised into the following subscales: student, instructor and institution. The questionnaire used a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The two questionnaires showed evidence of validity, reliability and internal consistency of the instrument’s subscales in assessing satisfaction with online learning, using Cronbach’s alphas of 0.91 and 0.85 for students and faculty, respectively [Citation21,Citation30]. The questionnaires were piloted, and the Cronbach’s alphas were 0.89 and 0.84 for students and faculty, respectively. Some items were modified slightly based on the feedback from respondents to improve clarity.

Questionnaires were sent to expectant participants by email along with the study information sheet. Participants were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. Online consent was received from all participants, and they were provided with contact information if they wanted to clarify doubts or ask questions. All data were coded to ensure anonymity.

SPSS was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the responses to the satisfaction scales. In the students’ satisfaction questionnaire, six items were recoded, where 5 = strongly disagree and 1 = strongly agree. For the faculty questionnaire, eleven items were recoded, where 4 = strongly disagree and 1 = strongly agree.

An independent sample t-test was used to compare the mean scores of the satisfaction subscale with gender and previous experience among faculty and students. The significance level was set at a p-value of less than .05. Student and faculty responses to the open-ended questions were analysed using the thematic analysis method.

Responses to open-ended questions for both students and faculty were analysed thematically, with MHT and WE undertake qualitative data analysis. The authors took the following steps, which were originally developed by Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke [Citation31] for conducting thematic analysis [Citation32,Citation33]: they familiarised themselves with the data, created the codes, generated the themes, and then reviewed the themes. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the institution (REC-20-04-26-01).

Results

Three hundred and fifty-eight responses out of 370 were received from students, a response rate of 97.8%, comprised of 335 (93.6%) female and 23 (6.4%) male students. The majority of students (71.8%, n = 257) had no previous experience with online learning (). Students attended an average of four online courses during the pandemic, compared to one course before the pandemic.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

Of the students, 68.7% (n = 246) were less satisfied with online learning, and 41.6% (n = 149) would not recommend the online learning experience to others. Nevertheless, students were satisfied with the communication during online learning (60.9%, n = 218), and almost half the students (47.5%, n = 170) were satisfied with the flexibility afforded during online learning. Challenges faced by students were the time taken to download learning materials (35.2%, n = 126), and 34.4% (n = 123) were dissatisfied with collaborative activities during online learning ().

Table 2. Student satisfaction

The subscales of student satisfaction revealed a mean score of less than 3.4 out of 5 in all subscales. The instructor subscale yielded the highest mean score (M = 3.36 ± 0.82), followed by the technology subscale (M = 3.31 ± 0.88) (). The correlation between the overall satisfaction and subscales among students reveals a significant correlation between the overall satisfaction of students with technology (r = 0.615, p = .000) and interaction (r = .665, p = .000) ().

Table 3. Subscales of students’ and faculty satisfaction

Table 4. Correlation between the overall satisfaction and satisfaction subscales among students

An independent t-test was conducted to compare student satisfaction with previous experience in online learning. The results suggest that previous experience in online learning does not affect satisfaction, as there were no statistically significant differences between students who had previous experience (75.5 ± 17.17) compared to students with no experience (77.07 ± 13.48), t(150.88) = .86, p = .394. Similarly, the results suggest that gender does not affect student satisfaction, as there was no statistically significant difference between male (76.17 ± 18.94) and female students (76.64 ± 14.30), t(356) = .15, p = .88

Seventy faculty responses were received, giving a response rate of 86.4%; 52.9% (n = 37) were men, and 82.9% (n = 58) had no previous experience teaching exclusively online (). Of the faculty, 62.9% (n = 44) were more satisfied with online teaching than the face-to-face method, and 92.9% (n = 65) reported that students were more enthusiastic about online learning than traditional learning ().

Table 5. Satisfaction among faculty

The areas of most dissatisfaction reported by faculty were higher workload (97.1%, n = 68), longer preparation time (91.4%, n = 64), and technical problems (85.7%, n = 60) (). The main challenge reported by faculty was technical difficulties (85.8%, n = 60), and 65.7% (n = 46) thought that student participation in online discussions was lower than face-to-face. Moreover, 55.3% (n = 38) were not satisfied with their ability to provide feedback to students during online learning ().

Evaluating the overall faculty satisfaction with subscales revealed that all subscales had a mean score of less than 2.8 out of 4. The student subscale yielded the highest mean score (M = 2.66 ± 0.19) of all subscales (). Nevertheless, the correlation between the overall satisfaction score and satisfaction subscales among faculty did not show any significance.

An independent t-test was conducted to compare faculty satisfaction with previous experience with online learning. The results suggest that previous experience did not affect satisfaction, as there was no statistically significant difference between faculty with previous experience (83.5 ± 11.37) and faculty with no experience (82.09 ± 7.71), t(68) = .530, p = .073. Similarly, the results suggest that gender does not affect faculty satisfaction, as there was no statistically significant difference between males (82.00 ± 9.41) and females (82.70 ± 7.12), t(68) = .35, p = .25.

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare satisfaction scores between faculty and students. The results suggest statistically significant differences between students (76.61 ± 14.61) and faculty (82.33 ± 8.36), t(164) = 5.71, p = .000.

Thematic analysis of the open-ended questions

One hundred twenty-six students and fifteen faculty responded to the open-ended questions. Most of the students reported that the main challenges during online learning were technical difficulties and support. The second reported difficulty was staying on-screen for a long time. Time zone differences were also reported by students residing outside the country. Some students stated that online learning was stressful, as most students were studying in a completely different environment that was not prepared for education. To increase satisfaction and future improvement, students suggested a combination of synchronous and asynchronous interactions. Most students also suggested incorporating other applications to engage them in learning, such as polls and gaming. Fewer students stressed the importance of office hours and academic advising. Students also thought proper communication before sessions would make them well-prepared. Finally, they stated that more online discussion accompanied by timely feedback from instructors would enhance their learning.

The most significant challenge faced by faculty was the preparation for online teaching. Most of the faculty reported colossal effort and time devoted to online teaching compared to face-to-face instruction. The faculty were very creative in teaching laboratory sessions, which was time-consuming and mentally exhausting. Similarly, the second reported challenge was technical difficulties; the faculty agreed on the importance of training and IT support. One faculty member also suggested incentives and rewards.

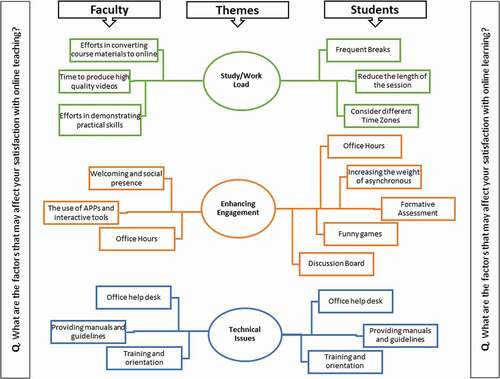

The thematic network illustrates the three key themes and demonstrates the subthemes for both students and faculty (). The network has three levels of themes: study-load and workload, enhancing engagement, and technical issues. Finally, the defined themes were named SWEET ().

Discussion

Student and faculty satisfaction with online learning is related to several factors, such as content, user interface, learning community, and learning performance [Citation34]. Faculty satisfaction also substantially impacts online course outcomes [Citation35]. To the best of our knowledge, no study has measured both faculty and student satisfaction simultaneously during the new normal; early studies measure either student or faculty satisfaction with online learning [Citation26–28]. Therefore, validated, pretested tools [Citation21,Citation30] adapted to the current context were employed to report both faculty and student satisfaction during the new normal.

In the current study, students were satisfied with the communication and flexibility afforded during online learning. Interaction and technology were the greatest challenges reported by students along with engagement in collaborative activities during online learning. Faculty were satisfied with the communication and communication tools used during online learning. The areas of most dissatisfaction reported by faculty were higher workload, longer preparation time, and technical problems. There were statistically significant differences between student and faculty satisfaction.

The current study revealed that more than two-thirds of the students were less satisfied with online learning. This finding supports previous studies conducted in the USA, which reported that students were dissatisfied with online learning compared to face-to-face instruction [Citation36,Citation37]. Our findings might be due to personality, self-efficacy, and expectations related to the design and delivery of online learning and teaching, as reported in a previous study [Citation38]. Another factor for decreased satisfaction could be attributed to the sudden shift to online delivery of the curriculum due to COVID-19, in which there was no adequate time for preparation, accompanied by the stressful working conditions of the pandemic itself [Citation39].

The current study shows that students’ overall satisfaction correlated with technology satisfaction, and the most reported area of dissatisfaction was related to accessibility and availability of the instructor. In the current study, one-third of students were also dissatisfied with the amount of time taken to download resources. Many authors have reported that technical difficulties could lead to an ineffective learning experience, even using the best-designed online course. The same authors also reported that technology-related factors might impact student and faculty satisfaction with online education, including the level of technical support they can rely on and the user-friendliness of the technological infrastructure of their courses [Citation40]. Recent studies have reported that the current generation of students has less tolerance for delays in the time taken to download resources. It has also been reported that they expect 24/7 availability of the faculty to respond to their late emails, calls and comments on online discussions [Citation41].

The convenience and flexibility of online classes were found to be linked with student and faculty satisfaction [Citation42,Citation43]. In the current study, students agreed they were satisfied with the flexibility offered during online learning, and more than three-quarters of faculty thought it was valuable for students to have access to online courses worldwide. Nevertheless, due to the difference in zone time, students residing outside the country were not satisfied with time. These findings could be attributed to students’ family support in pursuing their learning remotely. It has been reported that health concerns and family obligations are essential inspirations for pursuing further online courses [Citation44,Citation45].

Several researchers have reported that most areas of faculty dissatisfaction are linked to workload, student engagement issues, and time spent preparing teaching materials [Citation46,Citation47]. The present study supports these early studies, where faculty reported a higher workload, difficulty motivating students in an online environment, and taking longer to prepare for an online course. Institutional support is essential for overcoming the aforementioned problems and has been recommended by many authors [Citation46,Citation47]. This support could be in the form of allowing sufficient time and compensative incentives for faculty [Citation48]. Zheng et al. (2016) and Martin et al. (2018) explained that organisational policies regarding online learning could influence faculty satisfaction [Citation24,Citation49]. Some faculty members believe that online learning provides more flexibility, while others view online teaching as time-consuming and rigorous labour, which quickly leads to burnout [Citation50–52].

Engaging students in online learning was one of the difficulties faced by faculty members. Students suggested formative assessment and online polls after sessions to give feedback to increase satisfaction and engagement. Feedback during online learning is essential to enhancing the achievement of learning outcomes [Citation14], and effective feedback should be timely to enhance students’ learning and help them monitor their progress [Citation53].

In the current study, students and faculty reported they were satisfied with the communication and communication tools they used during online learning. Tennyson and Hsia (2010) found that student–faculty interaction sustains a supportive learning environment, improves students’ performance, and elevates student satisfaction [Citation54]. In contradiction, the lack of interaction with faculty, unclear learning expectations, and vague evaluation criteria lead to student dissatisfaction [Citation55,Citation56]. Moreover, Cidral et al. (2018) concluded that the instructor’s availability was crucial for the triumph of online learning [Citation57]. Therefore, students might have adequate experience and better satisfaction in online classes when institutions provide sufficient online resources and technical support to enhance student-instructor interaction.

The current study demonstrates that students and faculty considered feedback during online learning to be useful and timely. Nevertheless, students suggested that adding online office hours would be beneficial to communication with their teachers. Effective feedback and communication from faculty compensate for the lack of face-to-face interaction and engage students in online learning [Citation58]. Informal feedback has also been associated with enhancing communication among peers and faculty as they offer ways to maintain or improve performance [Citation59].

More than one-third of the students (41.6%) were satisfied with peer interaction and 45% of students were satisfied with online discussions, compared to 65.7% of faculty who thought that the participation of students in online discussions is lower than in face-to-face classes. Students also suggested that small group discussions and fun gaming activities increase student interaction and engagement. These findings agree with previous studies that peer and collaborative learning led to better achievement and student engagement in online learning [Citation24]. Peer interaction provides opportunities to improve learning and enhances student experiences [Citation60]. Online discussion also plays a significant role in online learning success [Citation61]. Discussion is an active learning process that replaces passive listening and encourages students to engage in content with conversation and reflections. Using interactive multimedia facilitates active learning [Citation62]. It also encourages authentic learning, problem-solving skills, and reflection to develop new knowledge [Citation63].

The findings of the current study could be beneficial for planning, designing and delivering online learning activities, and it could increase student and faculty satisfaction with online courses and, consequently, the quality of learning. Correspondingly, it would be advantageous in increasing student engagement. To increase satisfaction and future improvement, the study recommends a combination of synchronous and asynchronous online approaches, incorporating different applications with the learning management systems used to engage students in online learning. Constructive and timely feedback on student performance is essential to enhancing their satisfaction with online learning. Training of faculty and orientation of students in addition to IT support will improve the satisfaction of both students and faculty. Finally, institutional support, including organisational policy, incentives and faculty development, will enhance faculty satisfaction with online teaching. The findings of the study may be of interest to college leaders and educational development, as satisfaction is a key differentiator in a competitive marketplace and crucial for improvement.

One of the current study’s strengths is that it reports satisfaction with online learning from two perspectives: student and faculty. This study highlighted common factors affecting student and faculty satisfaction with online learning in the new normal. The study further compared the satisfaction of both students and faculty. The limitation of this study is the use of a self-assessment questionnaire. Further analysis is required to provide an in-depth exploration of factors affecting satisfaction. The use of a comprehensive qualitative approach, including a focus group discussion and interviews, might be of help.

Conclusion

Online learning has been a useful and practical tool for curriculum delivery during COVID-19. Effective communication and flexibility afforded during online learning have been linked with increasing student satisfaction. Challenges facing students were the long duration of learning sessions and technology. On the other hand, technical assistance and students’ enthusiasm enhanced faculty satisfaction with online teaching. Higher workload, longer preparation time, and technical problems were challenges reported by faculty.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Maab H. Elbashir for designing the thematic Network , their colleagues and students who participated in the study

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Ahmed H, Allaf M, Elghazaly H. COVID-19 and medical education. Vol. 20, The lancet infectious diseases. New York: Elsevier Ltd; 2020. p. 777–10.

- Taha MH, Abdalla ME, Wadi M, et al. Curriculum delivery in medical education during an emergency: a guide based on the responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. UK: MedEdPublish; 2020 Apr. Vol. 9. 1.

- Ellaway R, Masters K. AMEE Guide 32: e-Learning in medical education Part 1: learning, teaching and assessment. Med Teach. 2008;30(5):455–473.

- Weerasinghe IS, Fernando RL. Students' satisfaction in higher education. American Journal of Educational Research. 2017 May 28;5(5):533-9.

- Bolliger DU, Inan FA, Wasilik O. Development and validation of the online instructor satisfaction measure (OISM). J Educ Technol Soc. 2014;17(2):183–195.

- Thurmond VA, Wambach K, Connors HR, et al. Evaluation of student satisfaction: determining the impact of a web-based environment by controlling for student characteristics. Am J Distance Educ. 2002;16(3):169–190.

- Öztürk G, Karamete A, Çetin G. The relationship between pre-service teachers’ cognitive flexibility levels and techno-pedagogical education competencies. Int J Contemp Educ Res. 2020;7(1):40–53.

- Wei H-C, Chou C. Online learning performance and satisfaction: do perceptions and readiness matter? Distance Educ. 2020;41(1):48–69.

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):1–26.

- Miyazoe T, Anderson T The interaction equivalency theorem. 2010;

- Tian SW, Yu AY, Vogel D, et al. The impact of online social networking on learning: a social integration perspective. Int J Netw Virtual Organ. 2011;8(3–4):264–280.

- Meyer KA. Student engagement in online learning: what works and why. ASHE High Educ Rep. 2014;40(6):1–114.

- Croxton RA. The role of interactivity in student satisfaction and persistence in online learning. J Online Learn Teach. 2014;10(2):314.

- Gómez-Rey P, Barbera E, Fernández-Navarro F. Measuring teachers and learners’ perceptions of the quality of their online learning experience. Distance Educ. 2016;37(2):146–163.

- Kurucay M, Inan FA. Examining the effects of learner-learner interactions on satisfaction and learning in an online undergraduate course. Comput Educ. 2017;115:20–37.

- Rienties B, Toetenel L. The impact of learning design on student behaviour, satisfaction and performance: a cross-institutional comparison across 151 modules. Comput Human Behav. 2016;60:333–341.

- Fishman B, Konstantopoulos S, Kubitskey BW, et al. Comparing the impact of online and face-to-face professional development in the context of curriculum implementation. Journal of Teacher Education. 2013;64(5):426–438. .

- Latip MSA, Newaz FT, Ramasamy R. Students’ perception of lecturers’ competency and the effect on institution loyalty: the mediating role of students’ satisfaction. Asian J Univ Educ. 2020;16(2):183–195.

- Cheon SH, Reeve J, Vansteenkiste M. When teachers learn how to provide classroom structure in an autonomy-supportive way: benefits to teachers and their students. Teach Teach Educ. 2020;90:103004.

- Bolliger DU. Key factors for determining student satisfaction in online courses. International Journal on E-learning. 2004;3(1):61-7.

- Bolliger DU, Wasilik O. Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with online teaching and learning in higher education. Distance Educ. 2009;30(1):103–116.

- Yildiz A. The factors affecting techno-pedagogical competencies and critical thinking skills of preservice mathematics teachers. MOJES Malaysian Online J Educ Sci. 2018;5(2):66–81.

- Harvey HL, Parahoo S, Santally M. Should gender differences be considered when assessing student satisfaction in the online learning environment for millennials? High Educ Q. 2017;71(2):141–158.

- Martin F, Bolliger DU. Engagement matters: student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learn J. 2018;22(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092

- Cahapay MB. Rethinking education in the new normal post-COVID-19 era: a curriculum studies perspective. Aquademia. 2020;4(2). ep20018.

- Al-Samarraie H, Teng BK, Alzahrani AI, et al. E-learning continuance satisfaction in higher education: a unified perspective from instructors and students. Stud High Educ. 2018;43(11):2003–2019.

- Tratnik A, Urh M, Jereb E. Student satisfaction with an online and a face-to-face business English course in a higher education context. Innov Educ Teach Int. 2019;56(1):36–45.

- Venkatesh S, Rao YK, Nagaraja H, Woolley T, Alele FO, Malau-Aduli BS. Factors influencing medical students’ experiences and satisfaction with blended integrated E-learning. Medical Principles and Practice. 2020;29(4):396-402.

- Bolliger DU, Halupa C. Student perceptions of satisfaction and anxiety in an online doctoral program. Distance Educ. 2012;33(1):81–98.

- Avgerinou M Teacher vs. student satisfaction with online learning experiences based on personality type. etpe.eu. 2010;

- Clarke V, Braun V Thematic analysis. In: Encyclopedia of critical psychology, Edited by editor is Lisa M. Given. New York: Springer; 2014. p. 1947–1952.

- Liamputtong P, editor. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Given LM. The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. New York: Sage publications; 2008.

- Wang YS. Assessment of learner satisfaction with asynchronous electronic learning systems. Inf Manag. 2003;41(1):75–86.

- Wingo NP, Peters GB, Ivankova NV, et al. Benefits and challenges of teaching nursing online: exploring perspectives of different stakeholders. J Nurs Educ. 2016;55(8):433–440.

- Driscoll A, Jicha K, Hunt AN, et al. Can online courses deliver in-class results?: a comparison of student performance and satisfaction in an online versus a face-to-face introductory sociology course. Teach Sociol. 2012;40(4):312–331.

- Garratt-Reed D, Roberts LD, Heritage B. Grades, student satisfaction and retention in online and face-to-face introductory psychology units: a test of equivalency theory. Front Psychol. 2016;7. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00673

- Bates R, Khasawneh S. Self-efficacy and college students’ perceptions and use of online learning systems. Comput Human Behav. 2007;23(1):175–191.

- Saravanan C, Mahmoud I, Elshami W, et al. Knowledge, anxiety, fear, and psychological distress about COVID-19 among university students in the United Arab Emirates. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Oct;11:582189.

- Wingo NP, Ivankova NV, Moss JA. Faculty perceptions about teaching online: exploring the literature using the technology acceptance model as an organizing framework. Online Learning J. 2017;21(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i1.761

- Roberts DH, Newman LR, Schwartzstein RM. Twelve tips for facilitating Millennials’ learning. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):274–278.

- Cole AW, Lennon L, Weber NL. Student perceptions of online active learning practices and online learning climate predict online course engagement. Interact Learn Environ. 2019;1–15. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1619593

- Landrum B, Bannister J, Garza G, et al. A class of one: students’ satisfaction with online learning. J Educ Bus. 2020:1–7.

- Mccutcheon K, Lohan M, Traynor M, et al. A systematic review evaluating the impact of online or blended learning vs. face-to-face learning of clinical skills in undergraduate nurse education. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(2):255–270.

- Fish LA, Snodgrass CR. Business student perceptions of online versus face-to-face education: Student characteristics. Business Education Innovation Journal. 2015;7(2):83-96.

- Al-Zahrani AM. Faculty satisfaction with online teaching in Saudi Arabia’s higher education institutions. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning. 2015 Apr;12(4):17-28.

- Al-Fraihat D, Joy M, Masa’deh R, et al. Evaluating E-learning systems success: an empirical study. Comput Human Behav. 2020;102:67–86.

- VanDerLinden K. Blended Learning as Transformational Institutional Learning. New Dir High Educ. 2014;2014(165):75–85.

- Zheng S, Wisniewski P, Rosson MB, et al. Ask the instructors: motivations and challenges of teaching massive open online courses. In: Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW. 2016. San Francisco, USA.

- Badia, A., Garcia, C., & Meneses, J. (2019). Emotions in response to teaching online: Exploring the factors influencing teachers in a fully online university. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 56(4), 446-457.

- Shah DT, Williams VN, Thorndyke LE, et al. Restoring faculty vitality in academic medicine when burnout threatens. Acad Med. 2018;93(7):979–984. .

- Duke NN, Gross A, Moran A, et al. Institutional factors associated with burnout among assistant professors. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(1):61–70. .

- Van Popta E, Kral M, Camp G, et al. Exploring the value of peer feedback in online learning for the provider. Educational Research Review. 2017;20:24–34.

- Wu JH, Tennyson RD, Hsia TL. A study of student satisfaction in a blended e-learning system environment. Comput Educ. 2010;55(1):155–164.

- Martin F, Wang C, Sadaf A. Student perception of helpfulness of facilitation strategies that enhance instructor presence, connectedness, engagement and learning in online courses. Internet High Educ. 2018;37:52–65.

- Pham L, Limbu YB, Bui TK, et al. Does e-learning service quality influence e-learning student satisfaction and loyalty? Evidence from Vietnam. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2019;16(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0136-3

- Cidral WA, Oliveira T, Di Felice M, et al. E-learning success determinants: brazilian empirical study. Comput Educ. 2018;122:273–290.

- Tanis CJ. The seven principles of online learning: feedback from faculty and alumni on its importance for teaching and learning. Res Learn Technol. 2020;28. DOI:https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v28.2319

- Elshami W, Abdalla ME. Diagnostic radiography students’ perceptions of formative peer assessment within a radiographic technique module. Radiography. 2017;23:1.

- Elshami W, Abuzaid M, Abdalla ME. Radiography students’ perceptions of Peer assisted learning. Radiography. 2020 May;26(2):e109–13.

- Kwon K, Park SJ, Shin S, et al. Effects of different types of instructor comments in online discussions. Distance Educ. 2019;40(2):226–242.

- Lewis CC, Abdul-Hamid H. Implementing effective online teaching practices: voices of exemplary faculty. Innov High Educ. 2006;31(2):83–98.

- Gedik N, Kiraz E, Ozden MY. Design of a blended learning environment: considerations and implementation issues. Australas J Educ Technol. 2013;29(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6