ABSTRACT

Prior models of well-being have focused on resolving issues at different levels within a single institution. Changes over time in medicine have resulted in massive turnover and reduced clinical hours that portray a deficit-oriented system. As developments to improve purpose and professional satisfaction emerge, the Texas Medical Association Committee on Physician Health and Wellness (PHW) is committed to providing the vehicle for a statewide collaboration and illuminating the path forward.

To describe the existing health and wellness resources in Texas academic medical centers and understand the gaps in resources and strategies for addressing the health and wellness needs in the medical workforce, and in student and trainee populations.

Various methods were utilized to gather information regarding health and wellness resources at Texas academic medical centers. A survey was administered to guide a Think Tank discussion during a PHW Exchange, and to assess resources at Texas academic medical centers. Institutional representatives from all Texas learning health systems were eligible to participate in a poster session to share promising practices regarding health and wellness resources, tools, and strategies.

Survey responses indicated a need for enhancing wellness program components such as scheduled activities promoting health and wellness, peer support networks, and health and wellness facilities in academic medical centers. Answers collected during the Think Tank discussion identified steps needed to cultivate a culture of wellness and strategies to improve and encourage wellness.

The Texas Medical Association Committee on Physician Health and Wellness and PHW Exchange provided a forum to share best practices and identify gaps therein, and has served as a nidus for the formation of a statewide collaboration for which institutional leaders of academic medical centers have affirmed the need to achieve the best result.

KEYWORDS:

- Texas

- emergence

- collaboration

- improve

- learning health systems

- academic

- health center

- medical center

- wellness

- well-being

- resilience

- health

- physicians

- students

- trainees

- residents

- work

- system

- factors

- professional

- workload

- culture

- relationships

- support

- work-life

- demands

- medicine

- medical

- coalition

- multi-dimensional

- domains

- social

- physical

- intellectual

- spiritual

- emotional

- mental

- financial

- environmental

- occupational

- share

- best-practices

- leaders

- providers

- time

- management

- funding

- participate

- workforce

- reward

- flexibility

- autonomy

- organizational

- institutional

Introduction

‘I will ATTEND to my own health, well-being, and abilities in order to provide care of the highest standard.’ – World Medical Association Declaration of Geneva

For centuries, the medical profession has been deemed a special calling anchored by an ethical foundation – one that upholds and practices altruism, compassion, love for humanity, intellectual challenge, and dedication. A set of ethical principles has guided the profession. Generations of healers and physicians have passed down the science and art of medicine, each subsequent generation mirroring the values and practices of its elders. In 2017, the World Medical Association (WMA) adopted a modified version of the Physician’s Pledge, expanding the scope of the oath that outlines the professional duties and ethical principles of the medical profession [Citation1]. The revised Geneva Declaration addresses ethical issues that include respect for teachers and colleagues, medical confidentiality, the patient-physician relationship, and an assessment of the impact of professional obligations [Citation1]. Preceding this modification was WMA’s Statement on Physician Well-Being [Citation2], which outlined increased occupational stress and workload with their potential negative impacts on physician health and capacity to ‘provide care at the highest standard.’

In 2019, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) released a consensus study report that revealed staggering statistics: ‘substantial symptoms of burnout’ in 35–54% of U.S. physicians and nurses and in 45–60% of residents and medical students. The authors of the 312-page report surmised the high rates of burnout ‘are a strong indication that the nation’s health care system is failing to achieve the aims for system-wide improvement.’ This study identified ‘numerous work system factors (i.e., job demands and job resources) that either contribute to the risk of burnout or have a positive effect on professional well-being,’ as follows [Citation3]:

Job demands:

Excessive workload, unmanageable work schedules, and inadequate staffing;

Administrative burden;

Workflow, interruptions, and distractions;

Inadequate technology usability;

Time pressure and encroachment on personal time;

Moral distress; and

Patient factors.

Job resources:

Meaning and purpose in work;

Organizational culture;

Alignment of values and expectations;

Job control, flexibility, and autonomy;

Rewards;

Professional relationships and social support; and

Work-life integration.

Due to international and national concerns supported by a body of literature, the authors have summarized in this manuscript a strategy to improve the wellbeing of learners and employees within Texas biomedical institutions [Citation3–6]. The authors’ regional strategy included the establishment of an inter-institutional endeavor facilitated by the Texas Medical Association (TMA) Committee on Physician Health and Wellness (PHW) to improve the health and well-being of those who are employed and who train within Texas’ learning health care systems. Endeavors would be inclusive of everyone in the learning and work environment; the committee recognizes that physicians, students, and trainees (e.g., residents and fellows) work and train alongside biomedical and health professions colleagues within learning health care systems.

The state of well-being within the medical profession

The World Health Organization’s constitution in 1948 said, ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.’ Following that, Halbert L. Dunn, chief of the National Office of Vital Statistics, authored a series of manuscripts and lectured in the late 1950s on his concept of ‘high-level wellness,’ defining it as ‘an integrated method of functioning, which is oriented toward maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable.’ The term ‘wellness’ gained more attention in 1979 when Dan Rather remarked in an episode of 60 Minutes, ‘There’s a word you don’t hear every day.’

In contrast, the term ‘burnout’ has much more recent origins. It is thought to have been coined in the early 1970s by American psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, who himself suffered from its symptoms. Subsequently, Maslach and colleagues created the Maslach Burnout Inventory as a burnout assessment tool [Citation7], which has since been widely used and is considered the standard research tool in this field [Citation8]. Burnout is defined as 'a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who work with other people in some capacity' [Citation7].

National and international health care-related entities have given physician burnout increasing attention over the past few decades. The decline in physicians’ well-being has been attributed to a host of intrinsic and extrinsicfactors. Schrijver summarized the following occupational etiologies contributing to the decline of health care workers’ health: alignment of goals and values, physician factors, new technologies, inefficiencies, loss of autonomy, perceived threats, balancing needs, chronic fatigue, and chronic stress [Citation9]. Others have highlighted potential etiologies that include a growing and aging patient population combined with a reduction in workforce due to limited expansion of graduate medical education programs and funding [Citation10,Citation11]. Moreover, physicians, students, and trainees from underrepresented and marginalized groups may have encountered discrimination and harassment, as well as micro and macro aggressions, within their work and learning environments [Citation12–15]. As a result, reports of depression, anxiety, and lower engagement levels in these groups have increased [Citation16].

The past decade, in particular, has seen the health and well-being of health care workers become a priority. International, national, regional, and local entities have issued calls to action, adopted position statements, and revised accreditation guidelines in an attempt to improve the health and well-being of health care workers and trainees (see . Organizations and Their Response to Burnout). More recent efforts also have focused on the culture and climate of institutions [Citation17–24].

Table 1. Organizations and their response to burnout

A Resident Wellness Consensus Summit was held in 2017, where a workgroup of 27 residents and three attending physicians developed a wellness curriculum, scientifically derived with input from this event [Citation25]. This was brought about due to the rising concern and high risk of physician suicide, specifically in emergency medicine. Development participants included physicians from the following emergency medicine departments: Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, Fort Hood, Texas; Loma Linda University Medical Center, California; Sinai Grace Hospital, Detroit, Michigan; University of Missouri Hospital, Columbia; and the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Another conference, held in 2018 by the radiology Intersociety Committee in which themes and strategies to foster wellness were identified to implement at the individual, work unit, and organizational level [Citation22]. These efforts were identified by staff and faculty from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Massachusetts, Stanford; University’s Department of Medicine, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle; Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta; University of Alabama School of Medicine; and the Mayo Clinic’s Department of Radiology in Rochester, Minnesota. A cross-sectional national survey study concluded ‘burnout rates are substantial even among the most resilient physicians.’ [Citation6]

As a profession, we face a moral and ethical obligation to address burnout in physicians at all levels (medical students, trainees, and independent physicians), as well as in other healthcare professionals including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses, and in basic scientists who work within our learning health systems [Citation26–31].

State of well-being in texas

In 1976, the Texas Medical Association’s (TMA) House of Delegates established the Impaired Physicians Committee and charged it with studying the impairment problem in Texas. The committee’s duties since have expanded to include education and prevention of illness. The name of the committee has changed over time to reflect the current emphasis and priorities of the TMA. As a result of advanced understanding of physician health and wellness, the committee’s name was changed in 2013 to the Committee on Physician Health and Wellness (TMA Bylaws 10.621 Committee on Physician Health and Wellness).

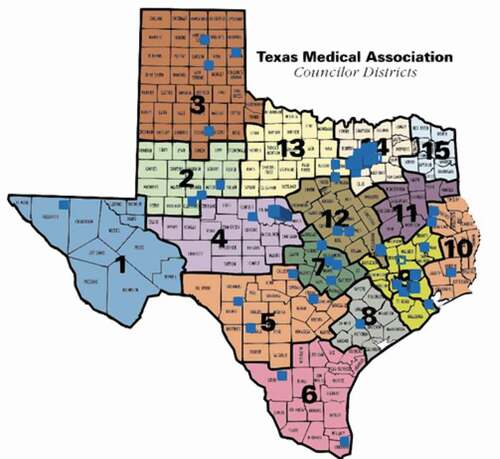

TMA is affiliated with 110 county medical societies. PHW educational activities are available to all county medical societies, medical schools, academic medical centers, hospitals, private practices, specialty medical associations, and similar organizations. Education team members have reached 41 counties (see TMA Councilor Districts map) since 2016. Since its inception, the PHW Committee has developed some 50 health and wellness continuing medical education (CME) courses. PHW Committee education team members presented more than 360 live CME sessions in 2014-18. A summary of all PHW course evaluations from the past five years shows 92% of physicians, residents, medical students, and nonphysicians strongly agree or agree that PHW course content and format met their expectations.

In addition to the 14 established medical schools in Texas, two having opened recently during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Citation32, AAMC Matriculating Student Questionnaire, the majority of medical students reported they would work in Texas after completing their medical training. The same report indicated that medical students ranked work-life balance as their highest priority and as ‘essential’ when considering their career path after medical school. Texas physicians are pushing state lawmakers to ensure Texas has enough residency positions to train doctors who study in Texas [Citation33]. With two new medical schools and potentially more residency programs, it is essential to establish a robust and evidence-based wellness program in every Texas academic medical center that also meets accreditation mandates [Citation10,Citation34].

Organizational well-being initiatives and opportunities

To better understand the availability of resources and programming designed to improve well-being in academic medical centers, the PHW Committee engaged Texas academic medical centers between September 2018 and May 2019. The committee collected data by telephone, through online surveys, and in person at the PHW Exchange: From Super Being to Human Being in March 2019. 13 Texas medical schools provided data:

Baylor College of Medicine,

TCU and UNTHSC School of Medicine,

Texas A&M University College of Medicine,

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine,

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Paul L. Foster School of Medicine,

University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine (UIWSOM),

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School,

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston McGovern Medical School,

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Long School of Medicine,

The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley School of Medicine,

The University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine (UTMB),

The University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, and

University of North Texas Health Science Center College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Texas academic medical centers currently address well-being through wellness assessment tools, retreats, student body organizations, wellness-related projects, and educational activities (see . Texas Academic Medical Centers’ Well-Being Initiatives). In addition, some state residency and fellowship programs, as well as programs on the national level, are actively establishing wellness committees and curricula [Citation25,Citation35].

Table 2. Texas academic medical centers’ well-being initiatives

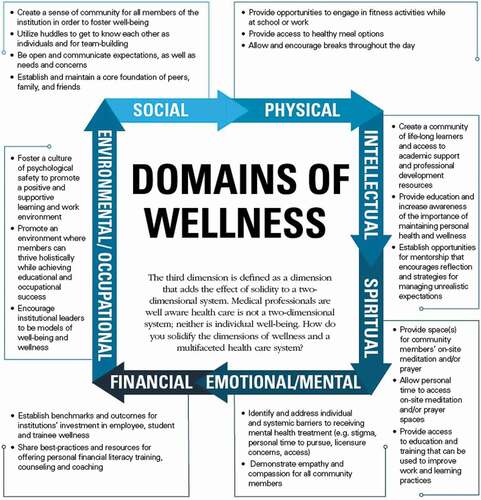

The PHW Committee found most institutions offered several programs to address the multiple dimensions of wellness that include occupational, environmental, intellectual, and physical activities. The majority offered online educational resources regarding well-being. Survey responses indicated a need for enhancing the following wellness program components:

Scheduled activities promoting health and wellness,

Peer support networks, and

Health and wellness facilities.

In March 2019, the PHW Committee and Baylor College of Medicine arranged a poster session as part of the PHW Exchange (see . List of Submissions). The session provided an opportunity for all Texas academic medical center faculty and staff, and medical school students, residents, and physicians to showcase and exchange their wellness innovations and strategies. Visit www.texmed.org/PHWPosterSession to view all posters submitted.

Table 3. List of submissions

The building of a coalition

On 2 March 2019, as part of the PHW Exchange, the TMA PHW Committee organized a Think Tank discussion to address the health and wellness needs in our learning health systems of our medical workforce, scientists, student and trainee populations, and staff. In her opening remarks, Jennifer G. Christner, MD, Dean of Baylor College of Medicine’s School of Medicine, said of her institution, ‘With the endorsement of executive leadership, we embarked on a journey to incorporate wellness and resilience into our curricular pillars.’ She also said role-modeling wellness, as well as teaching about it, is important to achieving work-life integration.

Sixty individuals representing the following six Texas medical schools participated in the Think Tank discussion: Baylor, McGovern Medical School, Texas A&M, UTMB, UT Southwestern, and UIWSOM. To capture best practices and challenges among the learning health systems represented, the Think Tank discussion was divided into five sections, each led by a facilitator with expertise in wellness: leaders and staff in academic medical centers; learning systems’ health and wellness providers; Texas Medical Board staff members; students, residents, and fellows; and physicians and staff in private practice.

Guided by facilitators, each Think Tank group explored these questions to delineate opportunities to improve the well-being of individuals in academic medical centers, and barriers:

What steps can students and trainees take to change a culture that encourages ‘super-being’ thinking?

How can you contribute to a culture of wellness at your learning health system?

Identify potential strategies to improve the health and wellness of those who work and learn at your learning health system.

How can physician leaders in a variety of practice settings encourage wellness among other physicians and members of the health care team?

An overarching theme from the Think Tank discussion was a desire to create an infrastructure that can facilitate the sharing of best practices and resources for primary, secondary and tertiary prevention, as well as support and training for health and wellness providers, leaders, students, and trainees in Texas academic medical centers. Additional themes that emerged from the discussions are summarized utilizing Baylor College of Medicine's domains of wellness (see ).

Conclusion and future steps

Our nation’s learning health systems are facing a crisis. The health and well-being of those who are working and learning in our academic health centers warrants attention. A recent article from chief medical residents concludes that ‘fostering meaning … to help residents find purpose and professional satisfaction in their work’ would go a long way towards curbing resident burnout [Citation36]. Based upon ideas like this and best practices described in the literature, leaders have been challenged to design, implement, and monitor institutional strategies to create environments that promote the health and well-being of their community members.

Individual strategies in isolation are insufficient. In addition to policies and programming to address burnout in medical students, trainees, and physicians, attention to external forces, as well as the entire learning system and its members are key. After an initial needs assessment is conducted across institutions informed by thought leaders and institutions leading organizational change in learning and workplace wellness, effective leaders can form partnerships and leverage each other’s skills and institutions’ initiatives to improve their own insight and institution’s capacity to address this important issue [Citation11,Citation37,Citation38]. In many ways, our nation’s unrest due to racial injustice, inequities, and COVID 19 has magnified stressors that are experienced within our workplace and institutional environments. COVID-19 has greatly influenced the workplace wellness of millions across our nation and the world. Healthcare workers have been affected directly and significantly. Those directly caring for the sickest COVID-19 patients in the intensive care units especially have faced death in unprecedented numbers, and they have also faced many anxieties and frustrations, elegantly enumerated by Shanafelt and colleagues [Citation39,Citation40]. Strategies for coping with how the COVID-19 pandemic has and likely will continue to affect healthcare providers will also be discussed at the upcoming PHW Exchange.

To move forward and maintain the 2019 PHW Exchange’s momentum, the monitoring of individual and organizational well-being is critical to assess the participant responses. We are proceeding with the original goal of enhancing our institutions’ existing wellness program components across multiple domains and various levels: individual, interpersonal, organizational and environmental. [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015) The 2021 PHW Exchange will be held in the fall as a statewide hybrid event and will include a follow up survey to the first Think Tank discussion with questions to identify institutional strategies, as well as gaps during the pandemic such as:

How did your institution/organization address the health and wellness needs of diverse learners and employees?

What kind of job and/or learning demands did you experience?

Were you given more job flexibility?

What kind of informational technology changes were made to support the wellbeing of learners and employees?

The Think Tank/Exchange provided a forum to share best practices and identify gaps, and has served as a nidus for the formation of a statewide collaboration. Proposed actionable steps for institutions were as follows and align with the most recent report from the Citation3, which called for institutions to:

Create positive work environments,

Create positive learning environments,

Reduce administrative burdens,

Enable technology solutions,

Provide support to clinicians and learners, and

Invest in research.

Administrators and wellness providers in learning health systems face unique challenges while addressing these issues that include variances in institutional capacity and demands. The benefits of establishing a Texas Medical Association statewide coalition include the opportunity to:

Share best practices (education, training],

Provide support for leaders and health and wellness providers and practitioners,

Create a statewide community that fosters well-being across institutions, and

Establish a forum for collaborations and partnerships to advance scholarly work.

Limitations to participating in the coalition include:

Time,

Funding (to travel and participate; membership in TMA), and

Institutional planning and priorities that might not be aligned.

In conclusion, institutional leaders of academic medical centers across the state affirmed the need to form a coalition to address the well-being needs of our biomedical workforce that include individual, interpersonal, organizational and environmental factors. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Since the launch of the PHW Exchange, our nation and the world have encountered increasing stressors related to COVID-19 and racism pandemics. To meet these increasing needs, TMA’s leadership has prioritized wellness and is moving forward with the development of the 2021 Wellness Project, a comprehensive approach to identify and support physicians and trainees struggling with the stress of the pandemic by providing advocacy to address workplace wellness factors, access to counseling, peer to peer support programs, family counseling, wellness education, yoga and mindfulness programming. This systemic approach will advance this statewide initiative by broadening the scope and support.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the TMA staff, Annette Bonner, Wendy Humphries, Shreika Madison, Ellen Terry, and the TMA’s PHW Committee members, the authors would like to thank the leadership at Baylor College of Medicine for hosting the inagural event including Alicia D. H. Monroe, MD and the speakers and small group facilitators from across the state who assisted with this endeavor: Alisha Adebayo, LMSW, Alan Swann, MD, Karen Lawson, PhD, MPH, Robin Dickey, S. Brint Carlton, JD, Amy Swanholm, JD, Stacey R. Rose, MD, Nana E. Coleman, MD, EdM, Jesse Gavin, Eric A. Storch, PhD, Nidal Moukaddam, MD, Joseph S. Kass, MD, JD, Bethany E. Powell, MD, Sheila LoboPrabhu, MD, and Kiran Shah, MD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Parsa-Parsi RW. The revised declaration of Geneva. A modern-day physician’s pledge. JAMA. 2017;318(20):1971–9.

- World Medical Association. 2015. WMA statement on physicians well-being. World Medical Association. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-statement-on-physicians-well-being/ (cited 2019 Dec 01

- National Academy of Medicine. (2019) Taking action against clinician burnout: a systems approach to professional well-being. Consensus study report highlights. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. Available from: https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/CR-report-key-messages-final.pdf (accessed 2019 Dec 01

- Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132–149.

- Nagy GA, Fang CM, Hish AJ, et al. Burnout and mental health problems in biomedical doctoral students. CBE life Sci Edu. 2019;18(2): ar27.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Resilience and burnout among physicians and the general US working population. JAMA Netw Open. 2020. 2020;3(7):e209385.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):103-–111.

- Schrijver I. Pathology in the medical profession. Taking the pulse of physician wellness and burnout. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(9):976–982.

- Butkus R, Lane S, Steinmann AF, et al. Financing U.S. graduate medical education: a policy position paper of the alliance for academic internal medicine and the American college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):134–137. Available from: https://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/2520466/financing-u-s-graduate-medical-education-policy-position-paper-alliance (accessed 2018 Jul 10).

- Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin. 2017;92(1):129–146.

- Aysola J, Barg FK, Martinez AB, et al. Perceptions of factors associated with inclusive work and learning environments in health care organizations: a qualitative narrative analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(4):4.

- Blewett LA, Hardeman RR, Hest R, et al. Patient perspectives on the cultural competence of US health care professionals. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(11):11.

- Osseo-Asare A, Balasuriya L, Huot SJ, et al. Minority resident physicians views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(5):e182723.

- Torres MB, Salles A, Cochran A. Recognizing and reacting to microaggressions in medicine and surgery. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(9):868–872.

- Dyrbye LN, Herrin J, West CP, et al. Association of racial bias with burnout among resident physicians. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(7):e197457.

- Burns CA, Lambros MA, Atkinson HH, et al. Preclinical medical student observations associated with later professionalism concerns. Med Teach. 2017;39(1):38–43.

- Coffey DS, Eliot K, Goldblatt E, et al. (2017) A multifaceted systems approach to addressing stress within health professions education and beyond. NAM Perspectives Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC.

- Drummond D. Prevent physician burnout: 8 ways to lower practice stress and get home sooner. Mo Med. 2016;113(5):332–334. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6139826/ (accessed 2018 Jul 10).

- Edmondson EK, et al. Creating a culture of wellness in residency. Acad Med. 2018;93,7(7):966–968.

- Hopkins J, Fassiotto M, Ku MC, et al. Designing a physician leadership development program based on effective models of physician education. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43(4):293–302.

- Kruskal JB, Shanafelt T, Eby P, et al. A road map to foster wellness and engagement in our workplace -- A report of the 2018 summer intersociety meeting. J Am College Radiol. 2019;16(6):869–877.

- Lases LSS, Arah OA, Busch ORC, et al. Learning climate positively influences residents’ work-related well-being. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2018;24(2):317–330.

- Shunk R, Dulay M, Chou CL. Huddle-coaching: a dynamic intervention for trainees and staff to support team-based care. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):244–250. Available from: https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=24362383 (accessed 2019 Jun 20).

- Arnold J, Tango J, Walker I, et al. An evidence-based, longitudinal curriculum for resident physician wellness: the 2017 resident wellness consensus summit. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(2):337–341.

- Baker K, Sen S. Healing medicine’s future: prioritizing physician trainee mental health. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(6):604–613. Available from: https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/sites/journalofethics.ama-assn.org/files/2018-05/medu1-1606.pdf (accessed 2018 Jun 15).

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1114–1130.

- Gardiner M, Sexton R, Durbridge M, et al. The role of psychological well-being in retaining rural general practitioners. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13(3):149–155.

- Lehmann LS, Sulmasy LS, Desai S, et al. Hidden curricula, ethics, and professionalism: optimizing clinical learning environments in becoming and being a physician: a position paper of the American college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(7):506–508.

- Murthy V (2019) “The heart of what we do” – Dr. Vivek Murthy on rediscovering meaning in medicine. ACGME Blog. Available from: https://acgme.org/Newsroom/Blog/Details/ArticleID/8071/The-Heart-of-What-We-Do-Dr-Vivek-Murthy-on-Rediscovering-Meaning-in-Medicine (cited 2019 Jun 10

- O’Connor AB, Halvorsen MS, Cmar JM, et al. Internal medicine residency program director burnout and program director turnover: results of a national survey. AAIM perspectives. Alliance Acad Internal Med. 132(2): 252–261. Available from: https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(18)31038-6/pdf (accessed 2019 Jul 20).

- Association of American Medical Colleges (2018) Matriculating student questionnaire. 2018 All Schools Summary Report. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/msq2018report.pdf (accessed 2019 Jan 01

- Perkins J (2019) Legislative hotline: GME must keep up with medical school growth. Texas Medicine Today. Available from: www.texmed.org/TexasMedicineDetail.aspx?id=50210&utm_source=Informz&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=TMT (cited 2019 Mar 27

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (2017). Common program requirements. Available from: www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. 2017. (cited 2019 Jun 01

- Cain L, Kramer G, Ferguson M. The medical student summer research program at the university of texas medical branch at galveston: building research foundations. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1.

- Berg DD, Divakaran S, Stern RM, et al. Fostering meaning in residency to curb the epidemic of resident burnout: recommendations from four chief medical residents. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1675–1678.

- Shanafelt, T.D., Noseworthy, J.H., Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clinic. 2017; 92(1):129-146.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Workplace health promotion. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/model/assessment/index.html (accessed 2021 Jul 07)

- Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. (2017) Burnout among health care professionals. A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC.

- Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133–2134.