ABSTRACT

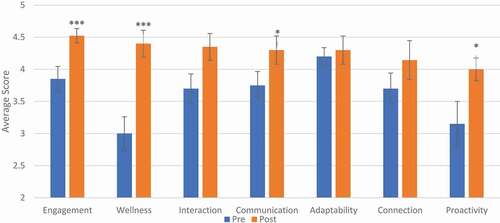

Medical students experience rising rates of burnout throughout their training. Efforts have been made to not only mitigate its negative effects, but also prevent its development. Medical improv takes the basic ideas of improvisational theatre and applies them to clinical situations. Given improv’s focus on self-awareness and reflection, in addition to its spontaneous nature, we hypothesized it had the potential to serve as a creative outlet, a way to prevent and/or mitigate the negative effects of stress, burnout, and fatigue, and provide a learning environment to develop skills necessary to succeed as a physician. University of California (UC) San Diego School of Medicine developed a medical improv elective for pre-clinical students and assessed its effects on student development and wellbeing. Students enrolled in the elective between Fall 2019 and Fall 2020 at UC San Diego School of Medicine were surveyed pre- and post- course completion using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Students noted significant improvement in domains related to proactivity in their professional career (3.15 to 4.00, p = 0.02), wellbeing (3.0 to 4.4, p < 0.001), engagement with their studies (3.85 to 4.52, p = 0.02), and communication (3.75 to 4.3, p = 0.04) after completion of the medical improv elective. We describe a pilot-study demonstrating the positive effects of improv on medical student wellbeing and professional development, laying the groundwork for both future study of improv on student wellness and its implementation in the pre-clinical curriculum.

Introduction

Medical students across the country are experiencing alarming rates of anxiety, depression, and burnout[Citation1]. Currently, it is estimated that 25–50% of medical students experience major depression and 10% experience suicidal ideation[Citation2]. This poses a major challenge for medical schools training the next generation of physicians. Diminished well-being not only inhibits a student’s performance, but also increases the likelihood of physician burnout and professional misconduct[Citation3]. It is therefore in the best interest of medical education programs to prioritize and bolster the well-being of its medical students.

Over the past decade, humanities courses have been introduced in medical curricula to provide balance and well-roundedness to students during their training [Citation4,Citation5]. These efforts have been shown to improve empathy and compassion in patient care settings, while also decreasing levels of burnout [Citation6,Citation7]. Traditionally, these courses have focused on literature to explore patient narratives and the ‘art’ of medicine. More recently, medical humanities have expanded to include the performing arts – of particular interest, medical improv [Citation8,Citation9].

The idea of ‘applied improv’ takes the principles of improv (deep listening, disciplined acceptance, self-awareness, spontaneity, and teamwork) and uses them in various contexts. Applied improv has been widely used in business and other fields over the past few decades with varying degrees of success [Citation10,Citation11]. In more recent years, applied improv has gained popularity in medical education. Participating medical educators have seen the value that improvisational theater training can provide in areas such as active listening, empathy, teamwork, adaptability, and resiliency. In medical improv, students participate in various exercises that directly apply the basic tenets of improv to clinical situations. Over the past decade, several medical schools have begun to incorporate medical improv training into their programs. Most institutions offer single seminars or limited exposure opportunities (<10 hours), rather than formal improv electives in their medical curricula [Citation5,Citation7,Citation9]. In addition, there has been minimal research examining the effect of medical improv on medical students’ well-being and development [Citation12–14]. Given the unpredictable nature of clinical medicine and the increasing stress and pressure that physicians experience, we hypothesized that the lessons learned in medical improv can benefit medical students not only in their professional training, but also with their personal well-being. In this paper we describe a pilot-study examining the effects of a medical improv elective on medical student wellbeing and professional development.

Methods

Medical improv elective overview

UC San Diego School of Medicine launched its inaugural medical improv elective for students in the pre-clinical curricula in Spring 2019. Inspired by Katie Watson’s Medical Improv Curriculum the course focused on experiential learning of improv [Citation15]. We modified the elective to fit the structure of other School of Medicine electives with 9 weekly, two-hour sessions led by two instructors trained in improv. The 3-credit course systematically introduced students to medical improv exercises focusing on different clinical topics each week. Topics included active listening, connecting with others, understanding emotions, dealing with ambiguity, juggling multiple goals, and recognizing bias and assumptions. Classes were structured around these topics with corresponding improv games that highlighted a specific idea. (e.g., a game highlighting nonverbal communication would be played, followed by a discussion of how these could be used in patient encounters to assess nonverbal patient cues). These were then followed by debriefing sessions where students would discuss what they learned from the exercise and how it could be applied to a clinical situation. In addition, students were given outside assignments (attending a live improv performance, course readings, etc.) to solidify the lessons learned. Each session built upon ideas from the previous week, challenging students to progressively step outside their comfort zone as they grew more familiar with improv. Exercises started with simple pattern games and then progressed to full scene work by the end of the course. By course completion, students learned the main tenets of medical improv, participated in dozens of exercises, and performed multiple times in front of their peers. The final assignment consisted of an ungraded written paper where students reflected upon a clinical encounter in which they experienced or observed the tenets of improv in action. This served as a way for students to reflect how improv can play a role in their lives as clinicians.

Study design

We developed a survey to assess the benefits of medical improv based on feedback from students taking the inaugural course. Questions included the following domains: engagement with studies, connection with other students, wellbeing, adaptability, communication, confidence, proactivity in their professional career, and development as future doctors (). Questions were tested for face validity with students and faculty familiar with improv. Responses were reported on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and converted into numerical values (1–5) for analysis. To protect student identity, all responses were anonymous. A paired one-tailed t-test was used to assess statistical significance between pre- and post- course survey responses. Following each question about a specific domain, students were given space to provide free response answers detailing how specifically improv affected that unique domain (e.g., “Please comment on communication). These were then analyzed and coded for different themes in various domains. Students were given the pre-course survey prior to start of the course. The post-course survey was distributed at the end of the course and students had two weeks to complete it. All study materials were approved by our institutional review board.

Results

A total of 39 students took the medical improv course from Fall 2019 through Fall 2020. Of these, 20 (50%) responded to the pre-course survey and 21 to post-course survey (54%). Students taking the elective expressed significant improvement in areas of wellness (3.0 to 4.4, p < 0.001), engagement with their studies (3.85 to 4.52, p = 0.02), communication (3.75 to 4.3, p = 0.04), and proactivity in their professional careers (3.15 to 4.00, p = 0.02). (). During the post-course survey, students were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement, ‘Participation in this elective helped me develop as a student doctor.’ All students agreed that the course helped them develop as a student doctor, with 55% responding with ‘Strongly Agree.’

When asked to reflect on what they gained from participation in the course, students commented on a wide range of topics (). Many discussed the direct correlation of improv to clinical encounters and the importance of active listening. Some detailed how the time spent in improv became a refuge from the constant ‘grind’ of school, while others described how they made new friendships from these interactions. All students noted a positive benefit from participation and an overwhelming majority recommended the curriculum be incorporated into training given its broad and far-reaching benefits.

Discussion

We describe a pilot-study evaluating the effects of medical improv on student development. While there have been few studies examining improv in medical education, none, to our knowledge, have addressed its association with professional development and wellness. We found medical improv was associated increased self-perceived improvements in multiple areas, including proactivity in one’s professional career, engagement with their studies, communication, and wellness.

Students showed a significant improvement in engagement with their studies after taking the improv elective, with free responses also noting that improv allowed them to ‘retreat from the demands of medical training and have a time to reset for the week’ and ‘helped them find more interest in school in general.’ These findings may reflect the potential for medical improv to bolster students’ engagement with their clinical training. Students can get worn down from the stressors inherent to medical school. Improv can provide a space to stop, think, and re-engage, which, in turn, can theoretically mitigate against disengagement, burnout and its sequelae. We hypothesize this may be due to medical improv’s emphasis on re-centering students in their training. In each session, students performed improv exercises followed by debriefing sessions to discuss how the exercises could be applied to their medical training. This reflection allowed students to re-center their focus on what is important and see the ‘bigger picture’ of their life and training, reconnecting students’ day-to-day activities with a personal goal-oriented mission.

Students also showed significant improvement in multiple domains including wellness, communication, and proactivity in their professional careers. We hypothesize that improv may provide a counterbalance to the stressors faced in medical school. Given its emphasis on teamwork and spontaneity, improv provides a space where students can freely stumble and ‘make mistakes.’ There are no right or wrong answers in improv, only opportunities for growth. This tenet of improv helps students reconceptualize '„failure' from being a shameful entity to being an opportunity for growth. Many students emphasized this as an important lesson they gleaned from the course. As seen by the large number of students indicating that improv played a role in improving their wellness, we believe that improv could provide a space for students to relax, learn, connect with classmates, and develop skills outside of a strictly clinical context.

This feeling of relaxation and freedom may also contribute to increased proactivity in their professional career. By giving students this space and freedom, medical improv sets the stage for openness in exploring their interests inside (and outside) of medicine. In turn, this may help students feel engaged in their development as physicians and proactively seek out new opportunities that may previously have felt uncomfortable. These positive factors may provide a protective effect against decreased wellbeing and further enhance students engagement with their study of medicine.

The seen benefits of medical improv on communication is more self-evident. Improv exercises constantly remind students of the importance of both verbal and non-verbal communication. All exercises reinforced the immense importance of listening to other participants, and then responding authentically. This interplay reinforces the key aspect of listening. As students develop their improvisational skills, they also develop as communicators. Communication skills are foundational to clinical competence and expertise. Patients desire a physician who will not only provide great care, but will listen to their needs and respond appropriately [Citation16]. Lastly, all students expressed that participation in the elective helped them develop as student-doctors. These findings provide evidence for the benefit of improv in medical education and support further study into the myriad ways medical improv may contribute to student development and wellbeing.

This study had several limitations. First, this course was an elective and our sample may not be reflective of the entire medical student population. Second, our sample size may be too small to show the full effect of improv on medical students. Third, our post- course assessment was obtained immediately after the end of the course and it is unclear whether the benefits gained will remain long-term.

Our data both mirror findings from the extant literature examining the role of medical improv on training and add to the literature by also examining medical improv’s effect on student wellbeing [Citation17–19]. Studies on medical improv are minimal with a 2018 scoping review finding just 7 studies to include in the analysis[Citation20]. Previous work suggests that resilience is an important aspect of medical improv, and some studies have assessed improv’s effects on skills directly related to clinical development, but no studies have examined its role on student wellbeing and personal development [Citation17–19].

While we found a self-reported benefit immediately after completion of the course, there is a need to see how long these benefits last and if there is an ideal length of improv training for medical students. In addition, objective assessment scales should be established for improv. One study developed a new scoring system to specifically detect the impact of improv in observed standardized clinical encounters (OSCEs) for first-year students [Citation21]. The impact of medical improv in the clinical setting should also be assessed. Additional studies are needed to comprehensively evaluate the benefits of improv training and its fit into an already full curriculum.

Overall, we describe the development of a medical improv elective and a pilot study for evaluating its effects in medical students' wellbeing. Our study results suggest direct benefits to student wellness from a medical improv curriculum and support the further investigation of it use in medical education. A comprehensive evaluation of the benefits of improv electives could solidify its place in both pre-clinical and clinical curricula.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (11.7 KB)Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–5.

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214–2236.

- Dyrbye LN, Massie FS Jr., Eacker A, et al. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1173–1180.

- Eisenberg A, Rosenthal S, Schlussel YR. Medicine as a performing art: what we can learn about empathic communication from theater arts. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):272–276.

- Blease C. In defence of utility: the medical humanities and medical education. Med Humanit. 2016;42(2):103–108.

- Graham J, Benson LM, Swanson J, et al. Medical humanities coursework is associated with greater measured empathy in medical students. Am J Med. 2016;129(12):1334–1337.

- Mangione S, Chakraborti C, Staltari G, et al. Medical students’ exposure to the humanities correlates with positive personal qualities and reduced burnout: a multi-institutional U.S. survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):628–634.

- Watson K. Perspective: serious play: teaching medical skills with improvisational theater techniques. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1260–1265.

- Watson K, Medical Improv: FB, Novel A. Approach to teaching communication and professionalism skills. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(8):591–592.

- Huffaker JS, West E. Enhancing learning in the business classroom: an adventure with improv theater techniques. J Manage Educ. 2005;29(6):852–869.

- Krusen NE. Improvisation as an adaptive strategy for occupational therapy practice. Occup Therapy In Health Care. 2012;26(1):64–73.

- Hanley MA, Fenton MV. Exploring improvisation in nursing. J Holist Nurs. 2007;25(2):126–133.

- Boesen KP, Herrier RN, Apgar DA, et al. Improvisational exercises to improve pharmacy students’ professional communication skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(2):35.

- Hoffmann-Longtin K, Rossing JP, Weinstein E. Twelve tips for using applied improvisation in medical education. Med Teach. 2018;40(4):351–356.

- Watson K. Northwestern medical improv curriculum plus teacher’s guide. 2018.

- Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, et al. Physician empathy and listening: associations with patient satisfaction and autonomy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):665–672.

- Hoffman A, Utley B, Ciccarone D. Improving medical student communication skills through improvisational theatre. Med Educ. 2008;42(5):537–538.

- Shochet R, King J, Levine R, et al. ‘Thinking on my feet’: an improvisation course to enhance students’ confidence and responsiveness in the medical interview. Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(2):119–124.

- Sawyer T, Fu B, Gray M, et al. Medical improvisation training to enhance the antenatal counseling skills of neonatologists and neonatal fellows: a pilot study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(15):1865–1869.

- Gao L, Peranson J, Nyhof-Young J, et al. The role of “improv” in health professional learning: a scoping review. Med Teach. 2019;41(5):561–568.

- Terregino CA, Copeland HL, Sarfaty SC, et al. Development of an empathy and clarity rating scale to measure the effect of medical improv on end-of-first-year OCSE performance: a pilot study. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1666537.